Abstract

Children born very low birth weight (<1500 grams, VLBW) are at increased risk for developmental delays. Play is an important developmental outcome to the extent that child’s play and social communication are related to later development of self-regulation and effective functional skills, and play serves as an important avenue of early intervention. The current study investigated associations between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication in Caucasian, Spanish speaking Hispanic, English speaking Hispanic, and Native American toddlers (18-22 months adjusted age) in a cross-sectional cohort of 73 toddlers born VLBW and their mothers. We found that the association between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication differed by ethnicity (F(3,65) = 3.34, p = .02). In particular, Spanish speaking Hispanic dyads evidenced a significant positive association between maternal flexibility and play sophistication of medium effect size. Results for Native Americans were parallel to those of Spanish speaking Hispanic dyads: the relationship between flexibility and play sophistication was positive and of small-medium effect size. Findings indicate that for Caucasians and English speaking Hispanics, flexibility evidenced a non-significant (negative and small effect size) association with toddler play sophistication. Significant follow-up contrasts revealed that the associations for Caucasian and English speaking Hispanic dyads were significantly different from those of the other two ethnic groups. Results remained unchanged after adjusting for the amount of maternal language, an index of maternal engagement and stimulation; and after adjusting for birth weight, gestational age, gender, test age, cognitive ability, as well maternal age, education, and income. Our results provide preliminary evidence that ethnicity and acculturation may mediate the association between maternal interactive behavior such as flexibility and toddler developmental outcomes, as indexed by play sophistication. Addressing these association differences is particularly important in children born VLBW because interventions targeting parent interaction strategies such as maternal flexibility must account for ethnic-cultural differences in order to promote toddler developmental outcomes through play paradigms.

Keywords: Very Low Birth Weight, Toddlers, Maternal Intrusiveness, Developmental Outcome, Ethnicity

1. Introduction

Although survival rates of children born weighing less than 1500 grams (Very Low Birth weight; VLBW) have increased substantially since the 1980s, the risk of developmental disability within this population remains a serious concern (Vohr, Wright, Poole, & McDonald, 2005). The adverse consequences of <1500g birth weight include neurosensory and cognitive deficits, as well as language, attentional, behavioral and learning difficulties (Hille, den Ouden, & Bauer, 1994; Marlow, Roberts, & Cooke, 1993; Pleacher, Vohr, Katz, Ment, & Allan, 2004; Vohr et al., 2003).

1.1 Play sophistication as an important developmental outcome in children born VLBW

Play is often considered an integral process of child development (Roskos & Christie, 2007). It is estimated that between three to twenty percent of young children’s time and energy is spent in play (Pellegrini & Smith, 1998). It is through play that young children fully explore their world, and the benefits of play on early cognitive, social, and motor development have been well documented (i.e., Roskos & Christie, 2007). Play has also been shown to contribute to language development (Bodrova & Leong, 2005) and the development of social competence skills in early childhood (Bodrova & Leong, 2005; Howes & Matheson, 1992).

Research examining play has shown that young children’s play develops in sophistication across early childhood (Bornstein, Haynes, O’Reilly, & Painter, 1996; Tamis-LeMonda & Bornstein, 1991). Play sophistication in early childhood appears to move from sensorimotor exploration to nonsymbolic activities, and eventually to symbolic and pretend play (Bornstein et al., 1996; Tamis-LeMonda & Bornstein, 1991). In addition, the sophistication of children’s play appears to predict later cognitive and academic outcomes (Landry, Smith, & Swank, 2000). Several studies have highlighted the role of parental characteristics, such as parent-child interaction factors, in predicting play outcomes in children, with parenting practices characterized as more responsive and engaged being associated with more sophisticated play (Bornstein et al., 1996; Tamis-LeMonda & Bornstein, 1991; Tamis-LeMonda, Bornstein, Baumwell, & Damast, 1996).

Although previous studies have indicated that children born VLBW, compared to full-term infants, show delays in play skills and that parent-child interactional patterns influence such outcomes (Hebert, Swank, Smith & Landry, 2004), literature examining the association between parental behavior and child play sophistication is relatively limited, especially among different ethnic groups. The current study investigated ethnic group differences among Caucasian, Spanish speaking Hispanic, English speaking Hispanic, and Native American mother-toddler dyads in the associations between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication in toddlers born VLBW.

1.2 Maternal Flexibility and Child Play Sophistication among Children Born VLBW

Few studies examining the effect of parental behavior on child outcomes have focused on the importance of maternal flexibility, defined as responsiveness to their child’s interest and willingness to let their child direct an activity. High levels of maternal flexibility or responsiveness have been associated with better cognitive outcomes in toddlers born preterm or low birth weight (<2500 g) (i.e., Dilworth-Bart, Poehlmann, Miller, & Hilgendorf, 2010; Landry, Smith, Swank, Assel, & Wells 2001; Moore, Saylor, & Boyce, 1998).

Although few studies to date have directly examined the relationship between maternal flexibility and play sophistication in children born VLBW, age has been found to moderate the relationship between maternal directiveness, the conceptual contrast to flexibility or responsiveness (Moore et al., 1998), and play sophistication among children born very low birth weight. Herbert and associates (2004) found that during infancy, high directiveness was related to slight increases in play skill, but at 24 months it was unrelated, and by early preschool, it was negatively related with play skills. Similarly, maternal directiveness has been positively associated with children’s cognitive and responsiveness skills at 2 years of age among both full-term and preterm (< 1600 g) toddlers. The negative influence of directiveness was found later, at age 3.5, suggesting that maternal directiveness needs to decrease as children’s competencies increase (Landry et al., 2000). For our sample of toddlers born VLBW, maternal directiveness may be particularly important at this age (18-22 months), with the corollary that maternal flexibility has a less positive influence.

1.3 Maternal Flexibility and Associated Child Developmental Outcomes in Ethnically Diverse Children

While studies of children born preterm emphasize the need to identify and intervene on parenting practices that will optimize the child’s development (Landry, Smith, Miller-Loncar, & Swank, 1997; Moore et al., 1998; Hebert et al., 2004; Magill-Evans & Harrison, 1999), findings regarding child development correlates of maternal interactive behavior for both full-term and preterm samples have been based on studies with predominantly Caucasian children (e.g., Fiese, 1990; Marfo, 1992; Moore et al., 1998). Hispanic as well as Native American families have been largely unrepresented in the literature on maternal flexibility, especially with samples of children born preterm. The few parenting studies that have included ethnically diverse samples (e.g. Hebert et al., 2004; Hubbs-Tait, Culp, Culp, & Miller, 2002; Landry et al., 1997; Landry et al., 2001) have not included significant proportions of Hispanic or Native American samples (less than 16%), and did not examine potential ethnic differences in parenting behaviors’ on children’s developmental outcomes.

Specifically within Hispanic families, acculturation may be an important factor impacting parenting practices and child outcomes in preterm children. Acculturation is a process through which an individual from a minority culture adopts the attitudes, values, and beliefs of the dominant culture (Abraido-Lanza, Armbrister, Florez, & Aguirre, 2006). Given the important relationship between communication and cultural identity, language is often used as a proxy measure of acculturation (Padilla, 1980), indicating that individuals from the same ethnic group who use a different primary language may represent two distinct samples (i.e., Cardona, Nicholson, & Fox, 2000; Whiteside-Mansell, Bradley, & McKelvey, 2009). Although there is limited research on the role of ethnicity and language use, and acculturation among children born preterm, literature on full-term children suggests that acculturation and ethnicity significantly impact parenting practices (i.e., Cardona et al., 2000, Iruka, 2009; Whiteside-Mansell et al., 2009). The impact of these parenting behaviors on child outcome is less well documented. Some studies suggest that the influence of ethnicity and acculturation fails to moderate the relationship between parenting practices and child outcome (Iruka, 2009), while other studies suggest that ethnicity may play a key role in how much parenting practices influence a child’s cognitive and social-emotional development (Whiteside-Mansell et al., 2009). Unfortunately, although several studies have incorporated less assimilated, Spanish speaking Hispanic mothers in their sample (i.e., Cardona et al., 2000; Whiteside-Mansell et al., 2009), few studies have compared Spanish speaking and English speaking Hispanic mothers to determine more specifically how language use, as an indicator of acculturation, influences ethnic differences in parenting styles.

The present study extends research on the association between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication in three key ways: (1) the impact of ethnicity was directly examined; (2) the role of ethnicity on this association was assessed in relation to toddler perinatal characteristics and maternal demographics: toddlers’ illness severity (approximated by days on ventilation), birth weight, gestational age, developmental status, maternal age, maternal education, and income; (3) these relationships were examined in a sample of ethnically diverse toddlers born VLBW and their mothers. We hypothesized that Caucasian and English speaking Hispanic dyads would demonstrate results similar to those reported in the literature (maternal flexibility and toy play would be negatively associated with toddler play sophistication). Our predictions regarding the associations for Spanish speaking Hispanic and Native American dyads, given the limited empirical literature, were more exploratory in nature.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

This study consisted of 73 children born preterm between the ages of 17 and 22 months, age adjusted for prematurity and their mothers. In order to be considered pre-term, infants weighed below 1500 grams at birth and were born less than 32 weeks gestation (see Table 1 for gestational age by ethnic group). All participants were recruited from the University of New Mexico’s Children’s Hospital Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Follow-up Clinic. Toddlers were excluded from the study if they had been prenatally exposed to drugs, were visually/hearing impaired, had a known genetic abnormality, were considered small for gestational age, constituted a multiple birth, and/or did not reside with their biological families. These criteria are used within national multi-center studies (Vohr et al., 2005), as they represent additional risk factors (i.e., greater risk for more severe developmental delays and associated poor outcomes) that cannot be controlled. Child ethnicity was determined by maternal report and included 21 (29%) Caucasian, 18 (24%) Spanish speaking Hispanic, 13 (18%) English speaking Hispanic, and 21 (29%) Native American mother-child dyads. Of the Spanish speaking Hispanic mothers, all were monolingual or bilingual Spanish speakers of Mexican heritage. English speaking Hispanics comprised mothers who identified as primarily English speaking. This division of Hispanic families based on primary language was an effort to minimize the heterogeneity of acculturation within our Hispanic subsample (i.e., Badr, 2001; Gorman, Madlensky, Jackson, Ganiats & Boies, 2007). See Table 1 for demographics for the total sample and by ethnic group.

Table 1.

Demographics and Primary Study Variables

| Total Sample | Caucasian |

Spanish

Speaking Hispanic |

English

Speaking Hispanic |

Native

American |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n(%) | n (%) | |

| Total | 73 | 21 (%) | 21 (%) | 13 (%) | 18 (%) |

| Male | 38 (52%) | 10 (%) | 10 (%) | 7 (%) | 11 (%) |

| Female | 35 (48%) | 11 (%) | 11 (%) | 6 (%) | 7 (%) |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

|

| |||||

| Age (months) | 20.17 (1.22) | 20.10 (1.25) | 19.98 (1.35) | 20.39 (1.14) | 20.30 (1.36) |

| Birthweight | 947.96 (234.62) | 989.90 (234.30) | 989.29 (265.21) | 880.23 (195.20) | 899.72 (220.38) |

| Gestational Age** | 27.32 (1.99) | 28.20 (1.67) A | 27.15 (1.77) AB | 25.91 (1.66) B | 27.51 (2.29) A |

| Days on ventilation | 24.53 (26.55) | 24.80 (33.19) | 28.48 (24.48) | 27.20 (19.74) | 24.61 (31.40) |

| Maternal Age** | 29.54 (6.99) | 32.90 (8.68) | 28.70 (5.20) | 24.85 (5.89) | 29.94 (5.25) |

| Education*** | 2.29 (1.68) | 3.14 (1.93) A | 1.14 (1.20) C | 2.00 (1.47) BC | 2.83 (1.20) AB |

| Income*** | 2.41 (1.89) | 3.90 (1.97) A | 1.05 (0.92) C | 2.46 (1.90) B | 2.22 (1.40) B |

| MDI* | 82.90 (11.36) | 88.71 (11.94) A | 80.73 (8.0) B | 78.52 (6.74) B | 81.71 (14.30) AB |

| Primary Study Variables | |||||

|

| |||||

| Maternal Flexibility* | 3.76 (1.12) | 4.31 (0.83) A | 3.29 (1.16) B | 3.88 (1.14) A | 3.58 (1.23) B |

| Toddler Play | |||||

| Sophistication | 1.82 (0.68) | 1.64 (0.65) | 1.88 (0.71) | 2.04 (0.75) | 1.81 (0.64) |

p < .05

p < .01

p< .001

Maternal Education was coded 0 (less than high school), 1 (completed high school), 2 (at least one year of college), 3 (Associate’s degree), 4 (Bachelor’s degree), 5 (some graduate school), 6 (Master’s degree or higher)

Of 115 families we attempted to recruit for the study, 78 agreed to participate (68%), 32 (28%) could not be reached to schedule an appointment, and 5 (4%) refused to participate. Based on those recruited (N = 83), our participation rate (N = 78) was over 93%. Of the families who could not be contacted, there were 12 (38%) Caucasian, 4(13%) Native American, and 16 (50%) Hispanic families (both Spanish speaking and English speaking). The 5 families that refused represented all 3 ethnic groups. Thus, the ethnic distribution of the 78 mothers who agreed to participate included relatively fewer Caucasian and Hispanic mothers, and relatively more Native American mothers compared to the eligible mothers who could not be contacted or declined. On other sociodemographic indices, however, our sample was comparable to the larger sample of families with a child born VLBW receiving services through the University of New Mexico’s Children’s Hospital Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Follow-up Clinic. Of the 78 participants, five videotapes were corrupted and therefore five dyads were excluded from our analyses. The demographics of the total sample, and by ethnicity, are in Table 1.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 The Caregiver-Child Affect, Responsiveness, and Engagement Scale (C-CARES)

The C-CARES scoring system (Tamis-LeMonda, Ahuja, Hannibal, Shannon, & Spellmann, 2001) is based on caregiver-child engagement during 10 minutes of videotaped free play. The C-CARES assesses the quality of caregiver-child interactions, assessing the quantity and quality of caregiver behaviors, infant/child behaviors, and dyadic behaviors. For this study, a version designed for 18 month old infants was used, taking into account developmental level across all categories. This coding system was selected because it represents one of the few measures of dyadic interactions, includes global factors anchored in behavioral instances, and has been used with ethnically diverse populations (e.g., Lowe, Erickson, MacLean, & Duvall, 2009; Shannon, Tamis-Lemonda, London, & Cabrera, 2002; Tamis-Lemonda, Briggs, McClowry & Snow, 2009). In particular, the C-CARES system has been used to code parent-child interactions with Hispanic parents (Gamble, Ramakumar, & Diaz, 2007; Lowe et al., 2009) and Native American parents (Lowe et al., 2009). Factor and cluster analyses reveal consistent factors across age categories (Tamis-Lemonda et al., 2001). Behaviors are rated on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating “largely not observed” and 5 indicating “constantly observed.” For both flexibility and play sophistication behaviors, the coder is provided with examples and how the item should be scored based on percentage of time observed (e.g. a toddler who engages in symbolic or creative play for 31-60% of the interaction would receive a code of 3 for the play sophistication variable).

A five minute segment of the videotaped play interaction was coded by a team of coders consisting of Caucasian and bi-lingual Hispanic advanced undergraduate and graduate students. This five minute segment represents the timeframe immediately following the Research assistant leaving the room and the dyad beginning to play. Each tape was scored independently by two trained coders using the Caregiver-Child Affect, Responsiveness, and Engagement Scale (C-CARES; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2001) coding system and discrepancies (i.e., anything more than a one point difference on any single item, all based on a 1-5 scale) were settled by a master coder. Procedures for English and Spanish coding were the same, although bilingual Spanish speaking graduate students and faculty members coded all Spanish tapes, and discrepancies were settled by a bilingual senior faculty member and author (J. Lowe). For purposes of inter-rater reliability, 20% of tapes were randomly selected and coded by a master coder. Intraclass correlations across mother, child and dyad scales were .8 or better with a master coder.

For this study, we were specifically interested in maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication. In the C-CARES system, maternal flexibility is a measure of the degree to which the caregiver is willing to let the child direct an activity, supporting the child’s independent exploration of toys and his/her environment throughout the interaction. A low score on this index indicates that the caregiver corrected or forcibly redirected play or activities initiated by the child, or did not allow the child to explore independently. A caregiver who receives a higher score may accept a child’s disinterest in a caregiver initiated activity, comment on the child’s choice of activity, or allow the child the freedom to explore toys in a developmentally appropriate way (i.e., banging). Note that these flexibility criteria, and in particular flexibility’s conceptual contrast to directiveness, are not always the criteria used in other research.

In addition, play sophistication measures the amount of symbolic play that the child exhibits throughout the interaction. Symbolic play (ex. pretending to drink from a cup or feeding a doll) and creative play (using toys in a unique manner) are both included in this measure. Variety of play is also considered in this score; the child must demonstrate multiple instances of play sophistication across a variety of scenarios in order to receive the highest score. The three individual scores from the C-CARES system used in the following analyses have been found to have sufficient variability and inter-rater reliability (Shannon et al., 2002). We also investigated maternal communication (amount of language) as a possible confound to maternal flexibility (e.g., a mother may receive a high flexibility score in part as a function of the amount of her verbal output). Maternal communication is a measure of the amount of verbal stimulation provided by the caregiver, irrespective of the quality of language used. A high score on this scale indicates a mother who is very verbally engaged during the play scenario. Finally, play

2.2.2 Bayley Scales of Infant Development II (BSID-II)

The BSID-II (Bayley, 1993) was used a measure of infant cognitive development. It has been used extensively with pediatric populations, including those at risk for developmental delays. The scales involve the child playing with a variety of toys, looking at pictures, and performing fine and gross motor tasks. The Mental Developmental Index (MDI) measures cognitive ability by assessing memory, problem solving, early number concepts, vocalizations, language, and social skills (Bayley, 1993).

2.2.3 Perinatal variables

Birth weight and gestational age were included as indices of prematurity (Vohr et al., 2005).

2.2.4. Maternal Demographic variables

Maternal age, education, and income were obtained. Maternal education was coded according to the following categories: 1 (less than high school), 2 (completed high school), 3 (at least one year of college), 4 (Associate’s degree), 5 (Bachelor’s degree), 6 (some graduate school), 7 (Master’s degree or higher). Income was coded in intervals of $10,000 ranging from 1 (less than 10,000), 2 (10,001 to 20,000), ... to 6 (50,001 and above).

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1 Study Procedures

Participants were initially recruited by research nurses at the University of New Mexico Hospital’s Special Baby Clinic. All mothers were informed that participating in the study was voluntary and that declining to participate would not affect access to health care services. Once informed consent was obtained, a developmental evaluation of the child was conducted (Bayley-II). This evaluation was conducted by either a senior developmental psychologist or an advanced graduate student. The mother remained in the room during the evaluation. Next, the mother and infant were left in the room alone and allowed to play for 10 minutes, using a uniform set of toys as outlined in the C-CARES manual (Tamis-Lemonda et al., 2001) and provided by the examiner. The play occurred either at home (N = 20) or in a family room in the Pediatric clinic (N = 40).

2.3.2 Data Analysis

This study included a cross sectional single cohort of toddlers (18-22 months) born VLBW and their mothers. To address our primary question regarding the role of ethnicity in the association between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication, we conducted an ANCOVA. Specifically, we investigated this relationship with ethnicity as the grouping variable (i.e., covariate), maternal flexibility as the independent variables, and toddler play sophistication as the dependent variable.

Next, to assess the magnitude of bivariate associations by ethnicity, we conducted Pearson correlations between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication by ethnic group. To determine whether mothers’ level of engagement and verbal stimulation explained the differential ethnic relationship between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication, maternal communication was added as a covariate to our ANCOVA model. Finally, to determine if the influence of perinatal medical variables or other demographic characteristics beyond ethnicity would explain the ethnic group interaction, we added eight additional independent variables included birth weight, gestational age, gender, test age, MDI scaled scores, maternal age, maternal education, and income) to our ANCOVA model.

3. Results

3.1 Demographic Findings

Descriptive statistics for the total group and by ethnicity are found in Table 1. Ethnic group differences were found on gestational age, MDI (measure of cognitive ability), and maternal age, education and income. There were no significant ethnic group differences on toddler age, birth weight, or gender. Regarding our two C-CARES variables of interest, there was an ethnic main effect on maternal flexibility but not on toddler play sophistication. There were no differences between the home and clinic assessment groups on demographic variables or C-CARES variables of interest (maternal flexibility and child play sophistication).

3.2 Ethnic group association differences between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication

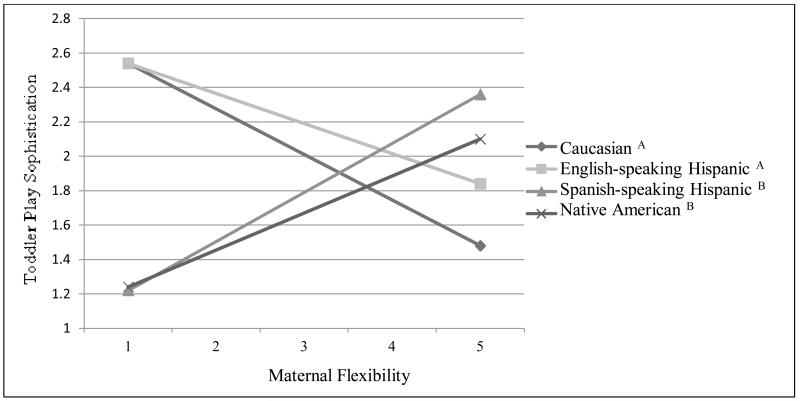

The relationship between maternal flexibility and the dependent variable (toddler play sophistication) by ethnicity were investigated with an ANCOVA using ethnicity as the grouping variable (i.e., covariate) and the maternal variable as the predictor variable. The ethnic interaction was significant (F(3,65) = 3.34, p = .02). Post-hoc Fisher’s exact test comparisons revealed that the Caucasian and English speaking Hispanics evidence similar associations; the Spanish speaking Hispanics and Native Americans showed similar associations; and the two sets of associations (Caucasian/English speaking Hispanics versus Spanish speaking Hispanics/Native Americans) were significantly different (all ps < .05). (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Maternal flexibility plotted in relation to toddler play sophistication by ethnicity.

Note: Notation of A and B indicate post hoc differences. Ethnic groups with the same letter do not differ significantly (p < .05).

3.3 Magnitude of associations between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication by ethnic group

In order to investigate the magnitude of associations between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication by ethnic group, Pearson correlations were conducted. The correlations for the four ethnic groups were: r = −.34 (ns) for Caucasian dyads; r = .39 (ns) for Native American dyads; r = .47 (p<.05) for Spanish speaking Hispanic dyads; and −.26 (ns) for English speaking Hispanics. Effect size estimates revealed that the association between maternal flexibility and play sophistication evidenced a small effect size in the negative direction for Caucasians and English speaking Hispanics, a small-moderate effect size in the positive direction for Native American dyads, and a moderate effect size in the positive direction for Spanish speaking Hispanic dyads.

3.4 Post-hoc tests to determine whether ethnic group association differences are explained by other variables

To determine whether mothers’ level of engagement and verbal stimulation explains this differential ethnic relationship between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication, maternal communication from the C-CARES was added as a covariate to our ANCOVA model. The interaction between maternal flexibility and ethnicity remained significant (F(3,64) = 3.37, p = .04), indicating that accounting for maternal communication did not explain the differential ethnic association.

To determine whether perinatal and demographic characteristics beyond ethnicity explain the three differential associations between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication, eight covariates were added to our ANCOVA model (illness severity (measured by days on ventilation), birth weight, gestational age, gender, test age, MDI scaled scores, maternal age, maternal education, and income). This statistical strategy represents a relatively conservative effort to determine the validity of the two association differences we found. In the model for maternal intrusiveness, the interaction between maternal flexibility and ethnicity on play sophistication remained significant (F(3,54) = 3.28, p = .03).

4. Discussion

An understanding of the developmental outcomes for children born VLBW includes identifying key correlates of development, such as parenting practices, which can serve as intervention strategies. Understanding how associations between parenting practices and developmental outcomes, such as play sophistication, differ by ethnicity is an important aspect of tailoring early intervention, a priority given health disparities (Green et al., 2005; Hanson & Lynch, 2004). Most studies to date have investigated developmental sequelae without examining whether such outcomes and their associations with parenting behaviors differ by ethnicity. Our study examined whether the relationship between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication differed by ethnicity.

We investigated these associations within a high risk group of toddlers born VLBW because play delays may persist among children born preterm through school age (Hebert et al., 2004). Although our results are tempered by our small sample size, we found that the associations between maternal flexibility and play sophistication differed by ethnicity in our group of toddlers born VLBW. In particular, findings indicate that Spanish speaking Hispanic dyads had a significant positive association between maternal flexibility and play sophistication of medium effect size. Results for Native Americans were parallel to those of Spanish speaking Hispanic dyads: the relationship between flexibility and play sophistication was positive and of small-medium effect size. Findings indicate that for Caucasians and English speaking Hispanics, flexibility evidenced a non-significant (negative and small effect size) association with toddler play sophistication.

4.1 Associations within the Ethnic Subsamples

Our finding regarding a small and negative association between maternal flexibility and play sophistication within Caucasian and English speaking Hispanic dyads was expected, given prior studies where maternal directiveness, the conceptual contrast to flexibility in our study, was positively associated with child outcomes at 2 years of age in a cohort of children born premature and preterm (< 1600 g; Hebert et al., 2004; Landry et al., 2000).

However, our findings are in contrast to some prior studies which found a positive relationship between maternal responsiveness and cognitive outcomes (i.e., Dilworth-Bart et al., 2010; Moore et al., 1998). In comparing our sample to the Dilworth et al. (2010) sample, not only was our sample considerably smaller in terms of birth weight, but also our sample reported considerably lower income and maternal education SES indices, making the Dilworth et al. (2010) study less comparable in terms of sample characteristics (mean income in the Dilworth sample was $60,939.24 (range = 0-200,000), with maternal mean education being 14.55 (range = 8-21)). Although the Moore et al. (1998) sample is comparable to our sample with regard to birth weight and SES indices, their overall study design is considerably different, given that they compared maternal responsiveness at 24 months to cognitive outcome at 5 years. One important distinction when interpreting the current results is that many studies define responsiveness and flexibility quite differently by including an affective component, “warm responsiveness (Landry, 2001)” with the maternal responsive behavior. Additionally, some researchers include positive aspects of maternal attentiveness or directiveness as a component of responsiveness, while our system specifically eliminates these behaviors from high flexibility scores.

Within the Spanish speaking Hispanic and Native American subgroups, the finding of a positive and moderate effect size association between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication cannot be placed in relevant literature, as there is no empirical literature with these samples in which to place it. However, this association would not be expected from the larger, primarily Caucasian- and African American-based literature regarding the positive effect of maternal directiveness on child outcomes at this age with lower-risk, LBW samples (e.g., Hebert et al., 2004; Landry et al., 2000).

4.2 Explaining Ethnic Group Differences in Associations

One explanation for why the relationship between maternal flexibility and child play sophistication varies across ethnic groups is that maternal interactive behaviors may carry a different meaning and be interpreted differently by the parent and child across cultural groups (Hanson & Lynch, 2004; Ispa et al., 2004). Ethnic and cultural background may be particularly salient in their shaping of family socialization processes (Bornstein, 1994; Garcia Coll, 1990; Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Hanson & Lynch, 2004) including parenting strategies, as well as the relationships between parenting style and a host of child outcomes (Carlson & Harwood, 2003; Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Harwood, Schoelmerich, Schulze, & Gonzalez, 1999; Ispa et al., 2004).

More generally, the disparate ethnic results regarding the influence of flexibility on children’s play sophistication may be best interpreted within the frame of differing socialization goals and parenting practices, particularly in regards to autonomy (Carlson & Harwood, 2003; Garcia Coll, 1990; Harwood et al., 1999). Historically, assumptions regarding normative parenting behaviors have been developed within a Euro-American set of goals and values (Zayas & Solari, 1994). In an early comprehensive review of parenting socialization practices, Hispanic mothers (including Mexican-Amercian) were found to use more modeling, visual cues, and directives than other teaching behaviors, while Anglo mothers used more verbal inquiry and praise (Zayas & Solari, 1994). These teaching behaviors may be indicative of larger socialization goals in which Hispanic mothers focus less on the development of self-reliance or independence, and place greater emphasis on a supportive, inter-dependent family structure (Zayas & Solari, 1994).

Although the construct of flexible parenting has not been investigated in relation to culturally-based socialization goals, and certainly not with toddlers born VLBW, other maternal behaviors have been identified as having different cultural salience in socialization processes and different clustering with other maternal behaviors. For example, maternal intrusiveness appears to oppose Euro-American cultural parenting goals (Harwood et al., 1999) and is negatively associated with maternal sensitivity and responsiveness in mothers of full-term Caucasian children (Hobson, Crandell, Patrick, Perez, & Lee, 2004; Marfo, 1992; Moore, Saylor, & Boyce, 1998; Wijnrocks, 1999). However, this clustering of parenting behaviors among Caucasian mothers does not hold for Hispanic mothers (Harwood et al., 1999). In more traditional (i.e., Spanish speaking) Hispanic cultures where autonomy is not as highly valued, maternal intrusiveness may serve to meet socialization goals (Carlson & Harwood, 2003) such as fostering connectedness with and respect for others (Hanson & Lynch, 2004; Harwood et al., 1999).

Within Native-American mother-child dyads there is a paucity of research examining specific parenting behaviors, much less their relationship to child behavior or cognitive development (Bernstein et al., 2005), and no study addressing maternal flexibility with toddlers born VLBW. However, some studies have provided descriptive data regarding more general child-rearing practices. For example, ethnographic studies of Southwestern Native American families characterized child-rearing practices as child-centered and communal, with a focus on children learning by listening, observing, and imitating their elders (MacPhee, Fritz, & Miller-Heyl, 1996). While cooperation is emphasized over individual achievement (Bernstein et al., 2005; MacPhee, Fritz, & Miller-Heyl, 1996), Native American culture also values self-determinacy and autonomy (MacPhee, Fritz, & Miller-Heyl, 1996; Field, 2001).

Hispanic as well as Native American families have been largely unrepresented in the literature on maternal interactive behavior, especially with samples of children born preterm. The few studies that have included ethnically diverse samples (e.g. Hebert et al., 2004; Hubbs-Tait et al., 2002; Landry et al., 1997; 2001) did not examine potential ethnic differences in parenting behaviors’ on children’s developmental outcomes.

4.3 Strength of Ethnic Association Differences

Our finding that the ethnic interactions maintained significance when maternal communication and other more distal variables, including infant developmental status (MDI), socioeconomic indices, and gender were included in the models, suggests the strength of these interactions. In fact, adding additional covariates provided a relatively conservative test of the validity of findings regarding different ethnic group associations.

4.4. Intervention Implications

As a result of the high risk of disability, the need for early intervention within this population has been well documented (Roberts, Howard, Spittle, Brown, Anderson, & Doyle, 2008). Studies indicate that early intervention with this vulnerable population is essential for reducing the high risk of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes associated with preterm birth (Robert et al., 2008).

The need for culturally sensitive early intervention strategies (Green et al., 2005; Hanson & Lynch, 2004) is particularly important given that the risk of being born VLBW (Reagan & Salsberry, 2005), as well as evidencing poorer developmental outcomes, is higher among ethnic minority children (Schmidt, Asztalos, Roberts, Roberston, Sauve, & Whitfield, 2002; Vohr et al., 2005). An important aspect of creating culturally sensitive interventions involves acquiring a better understanding of ethnic differences associated with developmental outcomes among children born VLBW. Few studies, however, have focused attention on ethnic differences in developmental outcomes or their correlates among children born VLBW. Although our study is not an intervention study and its findings are limited to children born VLBW, our results suggest that interventions targeting maternal interactive behavior in order to promote toddler developmental outcomes within this population (e.g., Hubbs-Tait et al., 2002) would benefit from accounting for ethnic-cultural differences in the child correlates of parenting strategies. Further, to test the effects of maternal interactive behavior interventions on child behavior outcomes, random assignment studies are necessary.

4.5 Limitations

The current study was limited by its relatively small sample size. The association differences we found may be due to cultural differences between groups (e.g., traditions, religious affiliation, cultural identification, family values, etc.), although this study was not designed to directly test this possibility. We did not administer a measure of acculturation to mothers beyond asking about language use. Furthermore, the associations we investigated are likely bidirectional, particularly over time, and infant temperament would be an important variable to include in future research. In addition, without a normative (healthy) comparison group, it is unclear whether our findings are specific to children born VLBW or are more generally applicable. Future investigation is also warranted to duplicate our findings, given our small sample size, and to examine directly how parenting behaviors cluster together as a function of ethnicity and acculturation.

A methodological limitation with the coding system employed in this study is that flexibility was coded based on specific behavioral markers. Affective tone and the delivery method were not included in the coding of flexibility, and could be salient elements that may even differ by ethnicity in their importance (Ispa et al., 2004). Furthermore, although narrowly defined by gestational age and birth weight, there is always potential variability in medical histories among children born VLBW that could account for some of the variability in play sophistication, along with their associations with maternal flexibility, beyond what was captured in our perinatal demographics (gestational age, birth weight). Also, it is unknown whether these results replicate to other ethnic groups, fathers, and populations that are not at risk for developmental delays. Although the division of Hispanic families based on primary language minimized the heterogeneity of acculturation within our subsamples (i.e., Badr, 2000; Gorman et al., 2007), future research with larger, more heterogeneous Hispanic samples addressing more nuanced elements of acculturation is necessary to understand the role of acculturation on parenting style and child development in VLBW toddlers. From a broader perspective, whether prematurity and the larger experience of having a child born VLBW impacts families of varying ethnicities differentially, thereby influencing maternal behavior and toddler outcomes indirectly and differentially, is an empirical question worthy of future exploration.

In spite of these limitations, the current study provides preliminary evidence that ethnicity may play an important role in determining the association of maternal flexibility with toddler play sophistication. Not only did we find ethnic interactions in this association, but the strength of this ethnic interaction was maintained when other competing (maternal communication) and more distal variables were included in our models. Additional research is warranted to investigate the longitudinal nature of these dyadic interaction associations, particularly within ethnic-cultural groups, and to investigate the likely bidirectional nature of these associations.

4.6 Conclusion

Overall, we found that the association between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication differed by ethnicity with Caucasian and English speaking Hispanic dyads showing a limited and negative association between maternal flexibility and toddler play sophistication and Native American and Spanish speaking Hispanic dyads showing a direct positive relationship. These findings address the importance of considering ethnicity, as well as toddler age and birth weight status as an index of perinatal health, when interpreting the meaning and child correlates of maternal behaviors. Many early intervention programs focus on reducing “maladaptive” maternal behaviors in order to improve child outcomes (e.g., Benoit, Madigan, Leece, Shea, & Goldberg, 2001; Cohen et al., 1999; Madigan, Hawkins, Goldberg, & Benoit, 2006). The findings related to the child correlates of maternal flexibility exemplify how maternal behaviors can differentially relate to child outcomes depending on the ethnic background of the mother-child dyad. As these findings suggest, early intervention providers must be family-centered (Hanson & Lynch, 2004), including incorporating ethnic influences when interpreting the meaning and appropriateness of maternal behaviors, especially with at-risk populations such as children born VLBW.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by DHHS/NIH/NCRR/GCRC Grant #5M01 RR00997.

References

- Abraido-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Florez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr LK. Quantitative and qualitative predictors of development for low-birth weight infants of Latino Background. Applied Nursing Research. 2000;14:125–135. doi: 10.1053/apnr.2001.24411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Manual for Bayley Scales of Infant Development. 2nd ed. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit D, Madigam S, Leece S, Shea B, Goldberg S. Atypical maternal behavior before and after intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2001;22:611–626. [Google Scholar]

- Bodrova E, Leong DJ. High quality preschool programs: What would Vygotsky say? Early Education and Development. 2005;16:435–444. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Cross-cultural perspectives on parenting. In: d’Ydewalle G, Eelen P, Bertleson P, editors. International perspectives on psychological science. II. Erlbaum; Hove, UK: 1994. pp. 359–369. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Haynes OM, O’Reilly AW, Painter KM. Solitary and collaborative pretense play in early childhood: Sources of individual variation in the development of representational competence. Child Development. 1996;67:2910–2929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona PG, Nicholson BC, Fox RA. Parenting among Hispanic and Anglo- American Mothers with young children. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2000;140:357–365. doi: 10.1080/00224540009600476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson VJ, Harwood RL. Attachment, culture and the caregiving system: the cultural patterning of everyday experiences among Anglo and Puerto Rican mother-infant pairs. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24:53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ, Muir E, Parker CJ, Brown M, Lojkasek M, Muir R, Barwick M. Watch, wait, and wonder: Testing the effectiveness of a new approach to mother-infant psychotherapy. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1999;20:429–451. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, & gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Bart J, Poehlmann J, Hilgendorf AE, Miller K, Lambert H. Maternal scaffolding and preterm toddlers’ visual-spatial processing and emerging working memory. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35:209–220. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiese BH. Playful relationships: A contextual analysis of mother-toddler interaction and symbolic play. Child Development. 1990;61:1648–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble WC, Ramakumar S, Diaz A. Maternal and paternal similarities and differences in parenting: An examination of Mexican-American parents of young children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2007;22:72–88. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McDoo HP, Crnie K, Wasik B, et al. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll C. Development outcome in minority infants: A process-oriented look into our beginnings. Child Development. 1990;61:270–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman JR, Madlensky L, Jackson DJ, Ganiats TG, Boies E. Early postpartum breastfeeding and acculturation among Hispanic women. Birth. 2007;34:308–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green N, Damus K, Simpson J, Iams J, Reece E, Hobel C, Merkatz I, Greene M, Schwartz R. Research agenda for preterm birth: Recommendations from the March of Dimes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;193:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MJ, Lynch EW. Diversity in Contemporary Families. In: Hanson MJ, Lynch EW, editors. Understanding Families: Approaches to Diversity, Disability, and Risk. Paul. H. Brooks Publishing Co; Baltimore, MD: 2004. pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood RL, Schoelmerich A, Schulze PA, Gonzalez Z. Cultural differences in maternal beliefs and behaviors: A study of middle-class Anglo and Puerto Rican mother- infant pairs in four everyday situations. Child Development. 1999;70:1005–1016. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert H, Swank P, Smith K, Landry S. Maternal support for play and language across early childhood. Early Education & Development. 2004;15:93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Matheson CC. Contextual constraints on the concordance of mother- child and teacher-child relationships. In: Pianta RC, editor. Beyond the Parent: The Role of Other Adults in Children’s Lives. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 1992. pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbs-Tait L, Culp AM, Culp RE, Miller CE. Relation of maternal cognitive stimulation, emotional support, and intrusive behavior during Head Start to children’s kindergarten cognitive abilities. Child Development. 2002;73:110–131. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iruka IU. Ethnic variation in the association between family structures and practices on child outcomes at 36 months: Results from Early Head Start. Early Education and Development. 2009;20:148–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ispa JM, Fine MA, Halgunseth LC, Harper S, Robinson J, Boyce L, et al. Maternal intrusiveness, maternal warmth, and mother-toddler relationship outcomes: Variations across low-income ethnic and acculturation groups. Child Development. 2004;75:1613–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry S, Smith K, Miller-Loncar C, Swank P. Predicting cognitive-language and social growth curves from early maternal behaviors in children at varying degrees of biological risk. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:1040–1053. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR. Early maternal and child influences on children’s later independent cognitive and social functioning. Child Development. 2000;71:358–375. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR, Assel MA, Vellet S. Does early responsive parenting have a special importance for children’s development or is consistency across early childhood necessary? Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:387–403. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J, Erickson SJ, MacLean P, Duvall SW. Early working memory and maternal communication in toddlers born very low birth weight. Acta Paediatrica. 2009;98:660–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.01211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan S, Hawkins E, Goldberg S, Benoit D. Reduction of disrupted caregiver behavior using modified interaction guidance. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2006;27:509–527. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill-Evans J, Harrison MJ. Parent-child interactions and development of toddlers born preterm. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1999;21:292–312. doi: 10.1177/01939459922043893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marfo K. Correlates of maternal directiveness with children who are developmentally delayed. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1992;62:219–233. doi: 10.1037/h0079334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JB, Saylor CF, Boyce GC. Parent-child interaction and developmental outcomes in medically fragile, high-risk children. Children’s Health Care. 1998;27:97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla A. The role of cultural awareness and ethnic loyalty in acculturation. In: Padilla A, editor. Acculturation, Theory, Models, and Some New Findings. Westview Press; CO: 1980. pp. 47–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini AD, Smith PK. The development of play during childhood: Forms and possible functions. Child Psychology and Psychiatry Review. 1998;3:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pleacher MD, Vohr BR, Katz KH, Ment LR, Allan WC. An evidence- based approach to predicting low IQ in very preterm infants from the neurological examination: Outcome data from the indomethacin intraventricular hemorrhage prevention trial. Pediatrics. 2004;113:416–419. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagan PB, Salsberry PJ. Race and ethnic differences in determinants of preterm birth in the USA: Broadening the social context. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:2217–2228. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts G, Howard K, Spittle AJ, Brown NC, Anderson PJ, Doyle LW. Rates of early intervention services in very preterm children with developmental disabilities at age 2 years. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2008;44:276–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskos KA, Christie JF, editors. Play and literacy in early childhood: Research from multiple perspectives. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt B, Asztalos EV,, Roberts RS, Robertson CMT, Sauve RS, Whitfield MF. Impact of bronchopulmonart dysplasia, brain injury, and severe retinopathy on the outcome of extremely low birth weught infants at 18 months. JAMA. 2002;289:1124–1130. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon JD, Tamis-LeMonda CS, London K, Cabrera N. Beyond rough and tumble: Low-income fathers’ interactions and children’s cognitive development at 24 months. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2002;2:77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Ahuja P, Hannibal B, Shannon J, Spellmann M. Unpublished manuscript. 2001. Caregiver-child affect, responsiveness and engagement scales (C-CARES) [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bornstein MH. Individual variation, correspondence, stability, and change in mother and toddler play. Infant Behavior and Development. 1991;14:143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bornstein MH, Baumwell L, Damast AM. Responsive parenting in the second year: Specific influences on children’s language and play. Early Development and Parenting. 1996;5:173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Briggs RD, McClowry SG, Snow DL. Maternal control and sensitivity, child gender, and maternal education in children’s behavioral outcomes in African American families. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2009;30:321–333. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohr BR, Allan WC, Westerveld M, Schneider KC, Katz KH, Makuch RW, Ment LR. School-age outcomes of very low birth weight infants in the indomethacin intraventricular hemorrhage prevention trial. Pediatrics. 2003;111:340–346. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.e340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohr BR, Wright LL, Poole WK, McDonald SA. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants <32 weeks’ gestation between 1993 and 1998. Pediatrics. 2005;116:635–643. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside-Mansell L, Bradley RH, McKelvey L. Parenting and preschool child development: Examination of three low-income U.S. cultural groups. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2009;18:48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Solari F. Early childhood socialization in Hispanic families: Context, culture and practice implications. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1994;25:200–206. [Google Scholar]