Abstract

Impairment of the circadian clock has been associated with numerous disorders, including metabolic disease. Although small molecules that modulate clock function might offer therapeutic approaches to such diseases, only a few compound have been identified that selectively target core clock proteins. From an unbiased cell-based circadian screen, we identified KL001, a small molecule that specifically interacts with cryptochrome (CRY). KL001 prevented ubiquitin-dependent degradation of CRY, resulting in lengthening of the circadian period. In combination with mathematical modeling, KL001 revealed that CRY1 and CRY2 share a similar functional role in the period regulation. Furthermore, KL001- mediated CRY stabilization inhibited glucagon-induced gluconeogenesis in primary hepatocytes. KL001 thus provides a tool to study the regulation of CRY-dependent physiology and aid development of clock-based therapeutics of diabetes.

The circadian clock is an intrinsic time-keeping mechanism that controls the daily rhythms of numerous physiological processes, such as sleep/wake behavior, body temperature, hormone secretion, and metabolism (1-3). Circadian rhythms are generated in a cellautonomous manner through transcriptional regulatory networks of clock genes. In the core feedback loop, the transcription factors CLOCK and BMAL1 activate expression of Period (Per1 and Per2) and Cryptochrome (Cry1 and Cry2) genes. After translation and nuclear localization, PER and CRY proteins inhibit CLOCK-BMAL1 function, resulting in rhythmic gene expression (1-3). Rate-limiting steps in many physiological pathways, including hepatic processes, are under the control of the circadian clock (1-3). The gluconeogenic genes phosphoenol pyruvate carboxykinase (Pck1) and glucose 6- phosphatase (G6pc) are controlled by CRY and the nuclear receptor REV-ERB (4-6).

Perturbations to clock function by genetic mutations or environmental factors (for example, shift work and jet lag) have been implicated in sleep disorders, cancer, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases (1-3). Thus, identification of clock-modulating small molecules may prove useful for the treatment of circadian-related disorders. Through cellbased high-throughput chemical screening approaches, a number of compounds that affect circadian rhythms have been discovered, including casein kinase I (CKI) inhibitors such as longdaysin (7-11). Synthetic ligands for the nuclear receptors REV-ERB and ROR have also been used to regulate the clock and metabolism (12, 13). Here we report the identification and characterization of a small molecule that specifically acts on CRY proteins and, as a result, regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis.

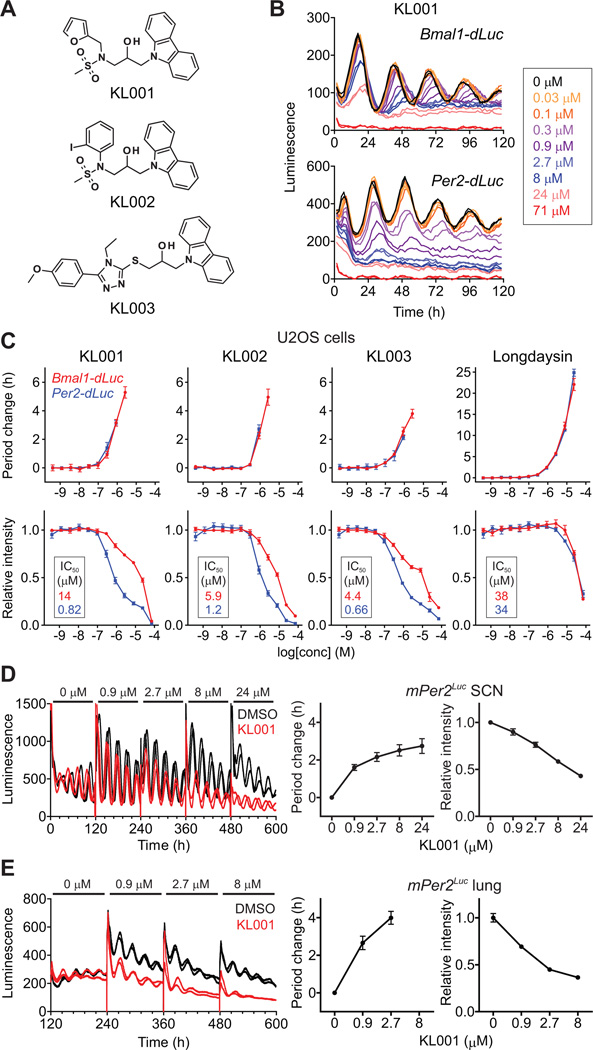

To identify small molecule modulators of the circadian clock, we analyzed the effect of a library of ~60,000 compounds on circadian rhythms of human osteosarcoma U2OS cell lines harboring a Bmal1-dLuc luciferase reporter (14). Among molecules that lengthened the period of luminescence rhythms, three carbazole derivatives (KL001-003, Fig. 1A) had pronounced effects. Continuous treatment with these compounds caused period lengthening and amplitude reduction in a dose-dependent manner in stable U2OS reporter cell lines harboring Bmal1-dLuc or Per2-dLuc (Figs. 1B, 1C, and S1). Additionally, treatment of cells with these compounds lowered basal reporter activity in Per2-dLuc cells compared with that of Bmal1-dLuc cells, whereas longdaysin had equivalent effects on both reporter cells (Figs. 1B, 1C, and S1). High concentrations of KL001 (>50 µM) exhibited cytotoxicity against U2OS cells (Fig. S2). We further tested the effect of KL001 on transiently transfected Bmal1-dLuc and Per2-dLuc reporters in mouse NIH-3T3 fibroblasts (Fig. S3) and on a mPer2Luc knock-in reporter (15) in mouse SCN and lung explants (Figs. 1D and 1E). KL001 caused dose-dependent lengthening of the period as well as signal reduction of Per2 reporters at the transcription (Per2-dLuc) and protein (mPer2Luc) levels in all assays. The compound had reduced potency in the SCN explant (Fig. 1D), suggesting a difference between SCN and peripheral clocks. Although period lengthening has been linked to the inhibition of casein kinase (CK) Iδ, CKIα or CK2 (9, 16), the carbazole derivatives did not affect their activities in vitro (Fig. S4), suggesting an alternative mechanism of action.

Fig. 1.

Carbazole derivatives lengthen the circadian period. (A) The chemical structure of carbazole derivatives. (B and C) Luminescence rhythms of Bmal1-dLuc and Per2-dLuc reporter U2OS cells were monitored in the presence of various concentrations of compound. Representative traces (n = 2) are shown in (B). The changes of period and luminescence intensity (an average of 24–120 h; IC50 values are indicated in insets of bottom panels) relative to DMSO control are shown in (C) as mean ± SEM (n = 4). When arrhythmic, the period was not plotted. (D and E) Luminescence rhythms of mPer2Luc knock-in reporter in mouse SCN (D) and lung (E) explants were monitored in the presence of increasing concentration of KL001 (each for 120 h). Data are mean ± SEM (n = 6 for SCN and 5 for lung).

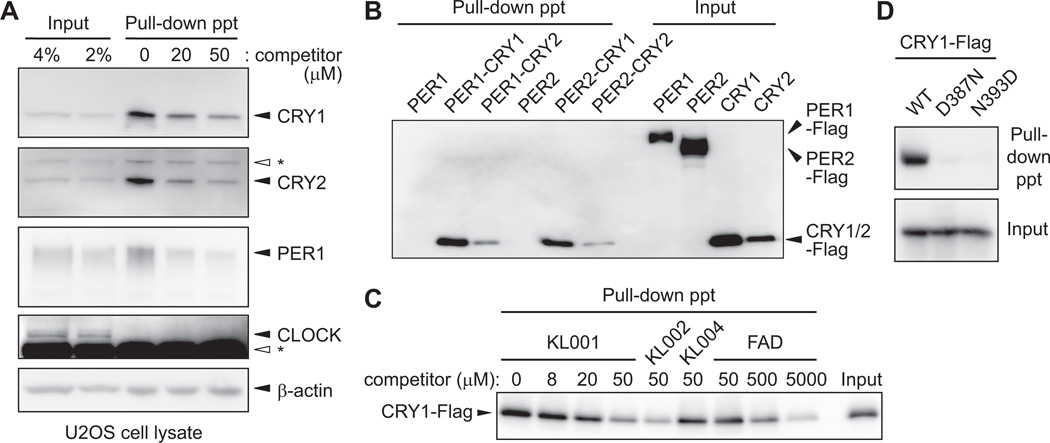

To identify the molecular target(s) of KL001, we used an affinity-based proteomic approach. A limited structure-activity relationship study identified a derivative of KL001 with an ethylene glycol substituent at the methanesulfonyl position that maintained period lengthening activity (KL001-linker, Fig. S5A). We therefore prepared an agarose-conjugate of KL001-linker and incubated it with U2OS cell lysate in the presence of 0, 20 or 50 µM KL001. Proteins that bound to the affinity resin and were released in the presence of free KL001 were analyzed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. In two independent experiments, only CRY1 was identified as a candidate of KL001-binding protein (Table S1). Protein immunoblotting with CRY1 specific antibody (5) (Fig. S6) confirmed both the binding of CRY1 to the affinity resin and decreased binding in the presence of 20 and 50 µM free KL001 (Fig. 2A). We further used antibodies against other core clock proteins and detected interaction of the affinity resin with CRY2, and to a much lower extent PER1, but not CLOCK. β-actin showed nonspecific binding that was not displaced by free KL001 (Fig. 2A). In extracts of human embryonic kidney HEK293T cells transiently overexpressing Flag-tagged core clock proteins, the KL001-agarose conjugate interacted with CRY1 and CRY2, but not PER1, PER2, CLOCK or BMAL1 (Figs. 2B and S7). Purified CRY1 proteins also directly bound to the affinity resin (Fig. S8). KL001 and KL002 similarly displaced CRY1 from the affinity resin (Fig. 2C), and KL004, an analog with a weak period effect (Fig. S5B), blocked CRY1 binding less effectively (Fig. 2C). Flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), a cofactor of CRY, inhibited CRY1 interaction with the affinity resin when added in excess (500–5000 µM, Figs. 2C and S9). Moreover, CRY1 proteins with mutations in the FAD binding sites (CRY1D387N and CRY1N393D) (17) interacted very weakly with the affinity resin (Fig. 2D). Thus, KL001 selectively interacts with CRY.

Fig. 2.

KL001 interacts with CRY1 and CRY2. (A) Agarose-conjugated KL001-linker compound was incubated with lysate of unsynchronized U2OS cells in the presence of various concentrations of free KL001 as a competitor. Bound proteins were identified by protein immunoblotting. Asterisk indicates nonspecific band. ppt, pellet. (B) Flag-tagged PER or CRY was transiently overexpressed in HEK293T cells, and lysates containing PER (PER) or a mixture of lysates containing PER and CRY (PER-CRY) were subjected to the pull-down assay. Bound proteins were detected with anti-Flag antibody. (C) Effects of KL001, KL002, KL004 and FAD on interaction of CRY1-Flag with KL001-agarose conjugate. (D) Wild type (WT) or FAD binding site mutant (D387N or N393D) of CRY1- Flag was subjected to the pull-down assay.

We analyzed the effect of KL001 on the mPer2Luc knock-in reporter in Cry deficient mouse fibroblasts. KL001-mediated reduction of the mPer2Luc intensity in wild type cells was abolished in the Cry1/2 double knockout cells (Fig. 3A). Similarly, siRNA-mediated depletion of CRY1 and CRY2 diminished the KL001-dependent reduction of Per2-dLuc intensity in U2OS cells (Fig. S10). Furthermore, a mutation of the CLOCK-BMAL1- binding site, the E2 enhancer element (18), abrogated the Per2 reporter response to KL001 in an NIH-3T3 transient transfection assay (Fig. S11). Thus, the compound likely enhances the repressive activity of CRY on the Per2 reporter in a CRY and E2 enhancer-dependent manner.

Fig. 3.

KL001 stabilizes CRY proteins. (A) Effect of KL001 on mPer2Luc knock-in reporter in Cry1/2 double knockout mouse fibroblasts. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 4). (B and C) Confluent unsynchronized U2OS cells were treated with KL001 for 48 h, and then subjected to RT-qPCR (B; mean ± SEM, n = 3) or protein immunoblot (C) analysis. (D) Luciferase-fused CRY1 (CRY1-LUC), its D387N mutant (CRY1D387N-LUC) or luciferase (LUC) was transiently overexpressed in HEK293T cells. The cells were treated with KL001 for 24 h, and then cycloheximide was added for luminescence recording. Profiles are shown by setting peak luminescence as 1 (left panels). Half-life of CRY1-LUC or CRY1D387N-LUC relative to LUC is shown by setting CRY1-LUC 0 µM condition as 1 (right panel). Data are mean ± SEM (n = 8). (E) Effects of KL001, KL002 and KL004 on CRY1 and CRY2 stability in HEK293 stable cell lines expressing CRY1-LUC, CRY2- LUC or LUC. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 4). (F) Effect of FBXL3 knockdown on the action of KL001 in Bmal1-dLuc or Per2-dLuc reporter U2OS cells. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 4).

Treatment of unsynchronized U2OS cells with KL001 reduced amounts of endogenous Per2 mRNA in a dose-dependent manner and had almost no effect on Bmal1 (Fig. 3B). Other CLOCK-BMAL1 target genes Per1, Cry1, Cry2 and Dbp exhibited a pattern of suppression similar to Per2 (Fig. 3B), consistent with KL001 enhancing CRY. Although amounts of PER1 protein decreased in parallel with Per1 mRNA expression after KL001 treatment, amounts of CRY1 and CRY2 did not correlate with their mRNA expression and were increased and sustained, respectively (Fig. 3C). Thus KL001 may stabilize CRY proteins. We therefore analyzed the effect of KL001 on the half-life of CRY1 by transiently expressing a CRY1-luciferase fusion protein (CRY1-LUC) in HEK293T cells. Treatment of cells with KL001 led to a dose-dependent increase in the half-life of CRY1-LUC, but did not affect the stability of the FAD binding site mutant CRY1D387N (Fig. 3D). In HEK293 stable cell lines expressing CRY1-LUC, CRY2-LUC or LUC, treatment with KL001 and KL002 increased the half-life of CRY1 and CRY2, whereas the same concentrations of KL004 showed almost no effect (Figs. 3E and S12). The effect of each compound on CRY stability is consistent with their effects on the circadian period (Figs. 1C and S5B) and CRY1 interaction (Fig. 2C), connecting the CRY stabilization with period lengthening. Because CRY proteins are targets of an E3 ubiquitin ligase FBXL3 and degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (19-21), we tested the effect of KL001 on CRY1 ubiquitination in vitro in a lysate of HEK293T cells transiently overexpressing CRY1-Flag. The compound (50 µM) inhibited ubiquitination of CRY1 and showed only a little effect on the CRY1D387N mutant (Fig. S13). Moreover, siRNA-mediated depletion of FBXL3 in U2OS reporter cells diminished the effects of KL001 on the period and Per2 reporter intensity without affecting longdaysin effects (Figs. 3F and S14). These results indicate that KL001 inhibits FBXL3 and ubiquitin-dependent degradation of CRY proteins and further support the selectivity of the compound.

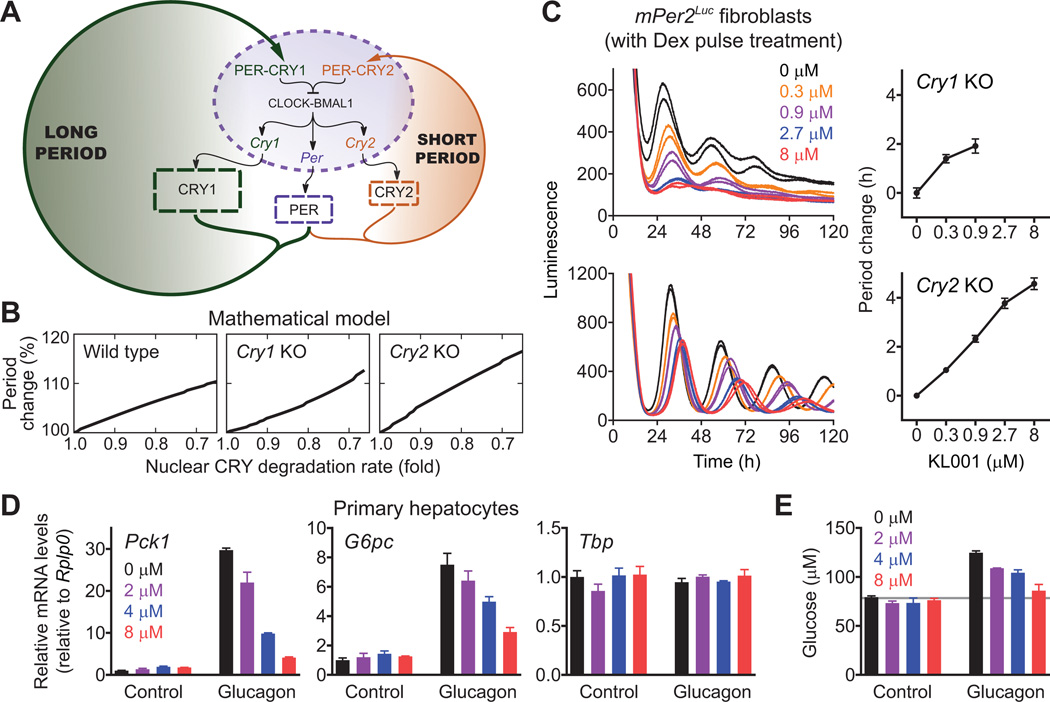

We then utilized KL001 in combination with mathematical modeling to explore how KL001-mediated CRY stabilization results in period lengthening and to define the roles of the seemingly redundant CRY isoforms in the clock mechanism. We constructed a simple mathematical model of the PER-CRY negative feedback loop (Figs. 4A and S15A) (14). The model successfully reproduced period shortening and lengthening by dose-dependent knockdown of Cry1 and Cry2, respectively (22) (Fig. S15B), and also period shortening by stabilization of cytosolic CRY2 (23) (Fig. S15C). For period lengthening by KL001- dependent CRY stabilization, the model predicted that the stabilization occurs in the nucleus (Figs. 4B left panel and S15D). Indeed, amounts of CRY1 and CRY2 proteins were increased and sustained, respectively, in a nuclear fraction of unsynchronized U2OS cells after KL001 treatment, although amounts of PER1 were reduced (Fig. S16). Furthermore, in silico stabilization of nuclear CRY2 in a Cry1 knockout background and nuclear CRY1 in a Cry2 knockout background both caused period lengthening (Fig. 4B, middle and right panels). Consistent with this prediction, continuous treatment with KL001 lengthened the period in both Cry1 knockout and Cry2 knockout fibroblasts in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 4C, S17A, and S17B). Similarly, the compound caused period lengthening in CRY1 knockdown and CRY2 knockdown U2OS cells (Fig. S17C) and in SCN explants from Cry1 knockout and Cry2 knockout mice (Fig. S17D). Thus, both CRY isoforms share a similar functional role in the period regulation, despite different free-running periods in their knockouts (Fig. 4A). With both CRY1 and CRY2 feedback loops intact, the nuclear CRY1/CRY2 ratio controls the period in a bidirectional manner, i.e., more CRY1 causes longer periods, and more CRY2 causes shorter periods (Figs. S15B and S15C).

Fig. 4.

Application of KL001 to define roles of CRY isoforms (A to C) and to control hepatic gluconeogenesis (D and E). (A) Scheme of the mathematical model consisting of the two parallel CRY feedback loops. (B) Effect of nuclear CRY stabilization on the period in wild type, Cry1 knockout and Cry2 knockout cells in silico. (C) Cry1 or Cry2 knockout mPer2Luc knock-in mouse fibroblasts were stimulated with dexamethasone (Dex) for 2 h, and luminescence rhythms were monitored in the presence of KL001. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 4). (D and E) Mouse primary hepatocytes were treated with KL001 for 18 h and then stimulated with 10 nM glucagon for 2 h (D, for RT-qPCR analysis) or 3 h (E, for glucose assay). To measure glucose production, the cells were further incubated with glucose-free buffer containing 20 mM sodium lactate and 2 mM sodium pyruvate for 4 h (E). Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3).

In the liver, CRY proteins negatively regulate fasting hormone-induced transcription of the Pck1 and G6pc genes, which encode rate-limiting enzymes of gluconeogenesis (4, 5). We therefore tested the effect of KL001 on expression of these genes in mouse primary hepatocytes. KL001 repressed glucagon-dependent induction of Pck1 and G6pc genes in a dose-dependent manner without affecting their basal expression (Fig. 4D). Consistent with this result, KL001 treatment repressed glucagon-mediated activation of glucose production (Fig. 4E). This repression was specific, because basal glucose production (Fig. 4E) and cellular lactate dehydrogenase activity (Fig. S18) were unaffected. Altogether our results demonstrate the potential of KL001 to control fasting hormone-induced gluconeogenesis. Given that human genome-wide association studies identified an association of the CRY2 gene locus with fasting blood glucose concentrations and presentation of type 2 diabetes (24, 25), KL001 may provide the basis for a therapeutic approach for diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Peters, X. Liu, M. Garcia, C. Cho and R. Glynne for assistance, C. Doherty for critical reading and K. Lamia and J. Takahashi for reagents. Supported in part by grants from the NIH (GM074868, MH051573 and GM085764 to S.A.K., GM096873 to F.J.D. and MH082945 to D.K.W.), Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology (to P.G.S), the U.S. Army Research Office (W911NF-09-0001 to F.J.D.) and VA Career Development Award (to D.K.W.). S.A.K. and P.G.S. serve on the Board of Reset Therapeutics and are paid consultants.

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S18

Tables S1 to S4

References (26-43)

References and Notes

- 1.Green CB, Takahashi JS, Bass J. Cell. 2008;134:728. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bass J, Takahashi JS. Science. 2010;330:1349. doi: 10.1126/science.1195027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asher G, Schibler U. Cell Metab. 2011;13:125. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang EE, et al. Nat Med. 2010;16:1152. doi: 10.1038/nm.2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamia KA, et al. Nature. 2011;480:552. doi: 10.1038/nature10700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin L, et al. Science. 2007;318:1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1150179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirota T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811410106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isojima Y, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908733106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirota T, et al. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JW, et al. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2011;50:10608. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Z, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:101. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solt LA, Kojetin DJ, Burris TP. Future Med Chem. 2011;3:623. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solt LA, et al. Nature. 2012;485:62. doi: 10.1038/nature11030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14., Materials and methods are available as supplementary material on Science Online.

- 15.Yoo SH, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308709101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirota T, Kay SA. Chem Biol. 2009;16:921. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hitomi K, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809180106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoo SH, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409763102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siepka SM, et al. Cell. 2007;129:1011. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godinho SI, et al. Science. 2007;316:897. doi: 10.1126/science.1141138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busino L, et al. Science. 2007;316:900. doi: 10.1126/science.1141194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang EE, et al. Cell. 2009;139:199. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurabayashi N, Hirota T, Sakai M, Sanada K, Fukada Y. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1757. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01047-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dupuis J, et al. Nat Genet. 2010;42:105. doi: 10.1038/ng.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelly MA, et al. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding S, Gray NS, Wu X, Ding Q, Schultz PG. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1594. doi: 10.1021/ja0170302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plouffe D, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802982105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu AC, et al. Cell. 2007;129:605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ukai-Tadenuma M, et al. Cell. 2011;144:268. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshitane H, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3675. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01864-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sonntag T, Mootz HD. Mol Biosyst. 2011;7:2031. doi: 10.1039/c1mb05025g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamitani T, Kito K, Nguyen HP, Yeh ET. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osawa Y, et al. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leloup JC, Goldbeter A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1132112100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee C, Etchegaray JP, Cagampang FR, Loudon AS, Reppert SM. Cell. 2001;107:855. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00610-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen R, et al. Mol Cell. 2009;36:417. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffin EA, Jr, Staknis D, Weitz CJ. Science. 1999;286:768. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Horst GT, et al. Nature. 1999;398:627. doi: 10.1038/19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vitaterna MH, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andersson J, Houska B, Diehl M. 3rd International Workshop on Equation- Based Object-Oriented Modeling Languages and Tools.; 2010. pp. 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hindmarsh AC, et al. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software. 2005;31:363. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilkins AK, Tidor B, White J, Barton PI. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2009;31:2706. doi: 10.1137/070707129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mirsky HP, Liu AC, Welsh DK, Kay SA, Doyle FJ., 3rd Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904837106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.