Abstract

Background

Clinicians use several measures to estimate adiposity. Body mass index (BMI), although not a measure of adiposity, is commonly used to define weight status. Percent body fat (%BF) measures total body fatness, which is composed of central and peripheral fat, estimated by waist circumference (WC) and skinfold thickness, respectively. Abnormal increases in fat during puberty may reflect an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Therefore, it is important to establish the normal patterns of change in clinically relevant measures of adiposity.

Purpose

To describe the normal patterns of change in clinical measures of adiposity during puberty.

Design/Methods

Multilevel modeling and linear regression analyses of 642 children in Project HeartBeat!, aged 8–18 years (non-black and black), who had assessments of BMI, %BF, WC, sums of 2- and 6-skinfolds, and pubertal stage (PS) triennially between 1991 and 1995.

Results

In males, the normal pattern from PS1 to PS5 is for %BF to decrease, skinfold thickness to remain stable, and WC to increase. However, after adjusting for height, WC does not change. In females, %BFremains stable from PS1 to PS5, whereas skin fold thickness increases. As in males waist-height ratio does not change, indicating that central adiposity does not normally increase during puberty. Although BMI increases in both genders and races from PS1 to PS5, mean values at PS5 were well below 25 kg/m2.

Conclusions

During puberty, increase in %BF is abnormal in females and even more so in males. Likewise, increase in waist-height ratio is also abnormal and may suggest an increased risk for adiposity-associated morbidity.

Keywords: Adiposity, Adolescent, Body composition, Children, Puberty

An appropriate amount of adipose tissue is necessary for good health, but excessive amounts, as in obese individuals, represent a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease [1]. Significant changes in the amount and distribution of adipose tissue occur during puberty, a time of rapid growth. Understanding the timing and variations in these changes might provide insight into why some individuals enter adulthood at greater risk for cardiovascular disease than others.

Clinical and epidemiologic definitions of obesity in children are based primarily on body mass index (BMI) (weight [kg]/height [m]2) percentiles for age and gender [2]. However, these definitions of obesity do not take into consideration pubertal status. Because direct measures (computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and dual X-ray absorptiometry) of the volume and distribution of adipose tissue are not easily accessible in the clinical setting, estimating the amount of adipose tissue without imaging requires the use of several different measures, each reflecting a different aspect of adiposity. These include BMI which reflects the relationship between weight and height to indicate weight status; percent body fat (%BF), which measures total body fatness; skinfold sums which represent peripheral adiposity; and waist circumference (WC) which is indicative of central adiposity [3–6]. Because each of the measures reflects a different aspect of the amount and distribution of adipose tissue, it is likely that the changes in adiposity and growth that occur during puberty will be reflected differently in these measures. Previous studies have described weight, height, and skinfold measures on cross-sectional and longitudinal cohorts of children and adolescents, but do not describe the changes in various measures of adiposity relative to pubertal stage (PS) [7–9]. One cross-sectional study used dual X-ray absorptiometry to describe body fat distribution during puberty among girls and young women [10]. In this article, we report the results of a longitudinal study to define the changes that occur in BMI, %BF, the sums of 2- (triceps + sub-scapular) and 6-(triceps + subscapular + midaxillary + abdominal + distal thigh + lateral calf) skinfolds, WC, and waist-height ratio (WC/Ht) during puberty among non-black and black youth.

Methods

Study design and participants

The design and methods of Project HeartBeat! (PHB) have been described previously [11,12]. Participants were recruited from The Woodlands, Texas (94% non-black), a middle-upper socioeconomic status community, and Conroe, Texas (12% black), a lower socioeconomic status rural community, both near the metropolitan Houston area. Subjects from three age group (8, 11, and 14 years) cohorts were enrolled and followed every 4 months for as long as 4 years (1991–1995). By recruiting subjects in these three age groups, there is overlap in ages at examination. For example, the participants in cohort 1 were 8 years of age at entry and were 11 or 12 years of age at their last scheduled appointments. Participants in cohort 2 were 11 years of age at entry and 14 or 15 at their last scheduled examinations to overlap with cohort 3, in which the participants were 14 years of age at entry. This design allows for evaluation of cohort effects at the overlapping ages and observation of the synthetic cohort from ages 8 through 18 years [13]. Anthropometry and PS were assessed at each 4-month visit. The total study population of PHB comprises 678 participants, of whom 49.1% were female, 74.6% white, 20.1% black, and 5.3% other (Hispanic, Asian, American Indian). To be consistent with previous reports of PHB, we describe our findings by “black” and “non-black” (white, Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian). Data for 633 participants who had pubertal staging for at least one encounter were analyzed.

PHB was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Texas-Houston and Baylor University. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants at the time of enrollment in PHB. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Utah exempted the current secondary data analysis study.

Anthropometric data

At each 4-month visit, body measurements were taken by trained and certified staff according to the methods described by Lohman et al [14]. Height (in) and weight (lb) were measured three times and then averaged. Height was measured without shoes, using a wall-mounted stadiometer. Weight was measured in light clothing using a beam balance scale. Height and weight data were converted to metric equivalents and BMI was calculated. The %BF was determined using tetrapolar bioelectrical impedance analysis with 50 Khz resistance and reactance (Model BIA-101, RJL Systems, DT) and body measurements in the sex-specific formulae of Guo et al [15,16].

Sums of 2-and 6-skinfolds (SF-2, SF-6, respectively) were obtained with a Holtain caliper (Wales, UK) with each site measured in triplicate to the nearest 0.1 mm. The three measurements were averaged before the sum of skinfolds was calculated. Triceps and sub-scapular locations were measured for sum of SF-2. Sum of SF-6 included measurements at triceps, mid-axillary, sub-scapular, abdominal, distal thigh, and lateral calf sites.

WC (cm) was measured at the level of the umbilicus with a steel tape measure one time at each occasion.

Pubertal staging

PS was categorized according to the method pioneered by Reynolds and Wines, then later described by Marshall and Tanner [17–21]. Trained observers recorded pubic hair stage (1–5) and breast (females) or genital (males) stage (1–5) at each 4-month visit. Previous analyses of PHB data used pubic hair staging. For this article we used breast/genital staging to reflect gonadal influence on pubertal development.

Analysis

We fit linear mixed models using SAS PROC MIXED [22] to account for repeated measurements across visits for the same subject. We reported least squares means and standard errors instead of means and standard deviations to account for effects of PS, gender, and race in the model. A heterogeneous variance autoregressive covariance structure was found to be appropriate for all measurements considered in this report. For each measurement, we considered main effects and two-way interactions for gender, race (black vs. non-black), and PS treated as a 5-level categorical variable. We retained interactions statistically significant at the α = .05 level in final models along with the corresponding main effects. The interaction race-PS was not significant for any model.

Concordance between breast/genital and pubic hair staging was 81.2%, with the highest concordance at PS1 and PS5 (95.3% and 92.4%, respectively). For models that used pubic hair for PS, each measure of adiposity had significant interaction between race-gender and gender-PS, except BMI, whereas those that used breast/genital lost the interaction between gender and PS for WC.

We adjusted the Type 1 error using Bonferroni’s correction, where α = .05 was divided by the number of tests (.05/300 = .00017) and the level of significance was conservatively set to .0001. We arrived at 300 tests by conducting six pair wise comparisons between race-gender categories at each of the five time points (PSs) for each of the six outcomes (measures of adiposity). For each race-gender category, we compared means at adjacent PSs and between PS1 and PS5. Thus, the total number of comparisons is 6× [(6 × 5) + (4 × 5)] = 300.

Results

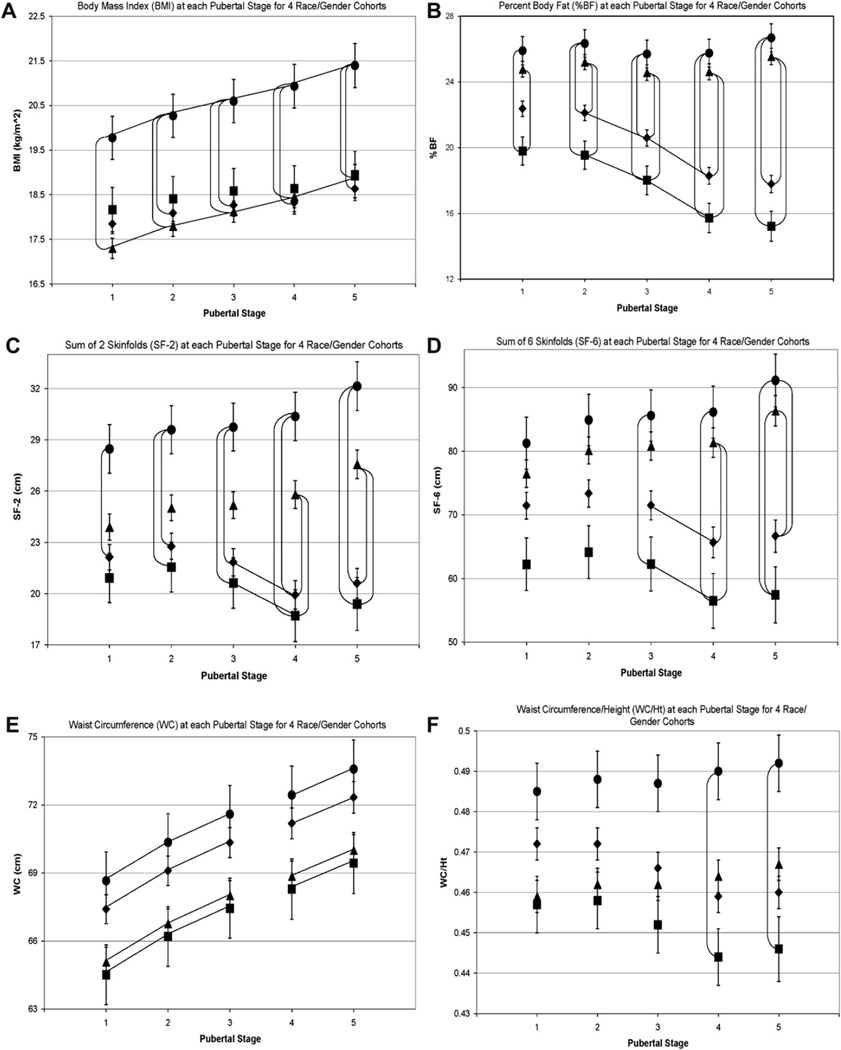

During the 4 years of PHB, the 633 participants were observed 1–12 times resulting in 5,077 observations of PS and anthropometric measurements. The numbers of observations at each PS for each race and gender cohort are shown in Table 1, and the means and standard errors for the six measures of adiposity at each PS for each race-gender cohort are shown in Figure 1, reflecting velocity of change for each measure.

Table 1.

Number of observations at each pubertal stage by race-gender pair

| Pubertal stage 1 | Pubertal stage 2 | Pubertal stage 3 | Pubertal stage 4 | Pubertal stage 5 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black males | 192 | 106 | 40 | 28 | 53 | 419 |

| Non-black males | 884 | 362 | 168 | 153 | 490 | 2,057 |

| Black females | 100 | 120 | 77 | 44 | 158 | 499 |

| Non-black females | 672 | 423 | 225 | 213 | 569 | 2,102 |

| Total | 1,848 | 1,011 | 510 | 438 | 1,270 | 5,077 |

Figure 1.

◆, Non-black males; ■, black males; ▲, non-black females; ●, black females. All datapoints in Figures 1A–F are least squares means ± standard error at each pubertal stage (PS; based on breast/genital development) for 4 race-gender cohorts. Lines connecting datapoints (vertical or horizontal) indicate significant differences between datapoints, p < .0001. Significant differences (p < .0001) between PS1 and PS5 for a race-gender cohort for each measure of adiposity are as follows: (A) Body mass index (BMI): changes between PS1 and PS5 are significant for 4 race-gender cohorts. (B) Percent body fat (%BF): changes between PS1 and PS5 are significant for males. (C) Sum of 2 skinfolds (SF-2): changes between PS1 and PS5 are significant for females. (D) Sum of 6 skinfolds (SF-6): changes between PS1 and PS5 are significant for females. (E) Waist circumference (WC): changes between PS1 and PS5 are significant for 4 race-gender cohorts. (F) Waist circumference/height (WC/Ht): There was no significant change from PS1 to PS5 for any race/gender cohort.

Males

From PS1 to PS5, non-black and black males experienced significant increases in BMI and WC and significant decreases in %BF. There were no significant changes in SF-2, SF-6, and WC/Ht. A total of 12.5% had BMI 85th–95th percentile (“overweight”) and 13.5% had BMI >95th percentile (“obese”) [23].

Females

BMI, SF-2, SF-6, and WC increased significantly from PS1 to PS5. There were no significant changes in %BF or WC/Ht. A total of 15.5% had BMI 85th–95th percentile (“overweight”) and 8.5% had BMI >95th percentile (“obese”) [23].

Comparison of measures of adiposity between race-gender cohorts

Body mass index

Non-black males did not differ from black males. Non-black females had significantly lower BMI than black females at every PS, whereas non-black males had significantly lower BMI than black females at PS2 to PS5. Non-black males did not differ from non-black females and black males did not differ from black females. Non-black males and black males experienced 4% increase in BMI from PS1to PS5. Non-black and black females experienced 9% and 8% increase in BMI, respectively, from PS1 to PS5.

Percent body fat

Among males, median %BF was 18.8, with 85th percentile >29% BF and 15th percentile <13% BF. Non-black males had higher %BF than black males, although the difference was not significant. Among females, median %BF was 24.3, with 85th percentile >33% BF and 15th percentile <18% BF. Non-black females had lower %BF than black females, but the difference was not significant. Non-black males had significantly lower %BF than non-black and black females at PS2 to PS5. Black males had significantly lower %BF than black and non-black females at each PS. The %BF decreased about 20% for non-black males and 23% for black males, and increased 3% for non-black and black females.

Skinfolds 2

Non-black males had greater SF-2 than black males, but the difference was not significant. Non-black females had smaller SF-2 than black females, but the difference was not significant. Non-black males had significantly smaller SF-2 than non-black females at PS4 and PS5. Black males had significantly lower SF-2 than black females at PS2 to PS5. Non-black males had significantly lower SF-2 than black females at all PS. The SF-2 did not change for non-black and black males, and increased 15% and 13% for non-black and black females, respectively.

Skinfolds 6

Non-black males did not differ from black males, nor was there a difference between non-black and black females. Non-black males had significantly lower SF-6 at PS4 than non-black females, and lower at PS5 than both non-black and black females. Black males had significantly lower SF-6 than black females at PS3 to PS5. Non-black males had significantly smaller SF-6 than black females at PS5. Black females had significantly smaller SF-6 than non-black females at PS4 and PS5. SF-6 did not change for non-black and black males, and increased 13% and 12%, respectively, for non-black and black females.

Waist circumference

As puberty progressed, waist circumference increased significantly by about 7% for each race-gender cohort from PS1 to PS5, and between each PS except between PS3 and PS4. There were no significant differences between any race-gender cohorts. For girls, 90th percentile >84 cm and 75th percentile >75 cm, while for boys 90th percentile >87 cm and 75th percentile >77 cm.

Waist-height ratio

Non-black and black males had a small decrease (about 2.5%) and non-black and black females had a small increase (about 1.5%) from PS1 to PS5, although none of these changes were significant. Black females had significantly greater WC/Ht than black males at PS4 and PS5.

Comparison of measures of adiposity with %BF

Using ≥85th percentile for %BF (>29 for males, >33 for females) as the cut-off for excess adiposity, we determined sensitivity and specificity of BMI ≥85th percentile and WC/Ht >0.5 for males and females. We found that, for males, BMI had sensitivity and specificity of 86% and 86%, respectively; and WC/Ht had sensitivity and specificity of 83% and 92%, respectively. For females, BMI had sensitivity and specificity of 84% and 89%, respectively; and WC/Ht had sensitivity and specificity of 77% and 92%, respectively. In other words, among 100 females with greater than 33% body fat, using BMI ≥85th percentile will identify 84 as having excess adiposity and will incorrectly identify 11 as having excess adiposity. If we now use WC/Ht >0.5, we will correctly identify 77 females with excess adiposity and fail to recognize eight who have excess adiposity.

We also compared WC with %BF, using WC >90th percentile [24] and WC >75th percentile [25]. We found that for both males and females sensitivity and specificity are less than 40% for WC >90th percentile and sensitivity remains less than 50%, whereas specificity is about 70% for WC >75th percentile.

Missing data

Anthropometric data for 45 participants, accounting for 732 observations, were not included because PS was not recorded. Non-black compared with black participants had 7.8% and 2.2% missing data, respectively (p = .02); whereas males compared with females had 8.1% and 5.1% missing data, respectively (p = .12). There was no difference in BMI z-score for those with missing pubertal data versus those with some or all pubertal data.

Discussion

This study provides extensive information regarding the expected changes in clinical measures of adiposity during puberty among normal weight boys and girls. Gender, but not race, consistently affects the measures that reflect total body fat (BMI, %BF), peripheral fat (SF-2, SF-6), and central fat (WC, WC/Ht) as puberty progresses. For BMI, there is a race effect among girls, but not boys. In boys and girls, BMI and WC increase significantly, which is consistent with the findings of Goulding et al [10]. When WC was adjusted for height (WC/Ht), this change was no longer significant, suggesting that the observed increase in WC may reflect normal growth. These findings are consistent with previous cross-sectional studies [26,27].

Central adiposity is a well-recognized risk factor for heart disease and its co-morbidities (diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension). Our findings provide evidence that central fat does not normally increase during puberty; therefore, an adolescent whose WC/Ht is increasing during puberty may be at higher risk than normal [28–33]. Studies of children suggest that abnormal amounts of central adiposity are present when WC/Ht is greater than .50 [26,27]. Our findings support the importance of interpreting WC in the context of height in children and adolescents.

Increases in BMI with concomitant decreases in %BF with no significant changes in measures of peripheral or central fat among the males suggest that the observed increases in BMI are due to greater increases in the amount of fat-free mass compared with that of total adipose tissue. The relationship between BMI, %BF, and sums of SF is different in girls. There are significant increases in BMI, WC, and the sums of the skinfolds, but %BF and WC/Ht remain constant, indicating that peripheral fat and fat-free mass increase during puberty. A cross-sectional study that used DXA, a precise measure of regional fat distribution but not clinically facile, identified an increase in %BF and lean body mass when comparing girls at PS1 with girls at PS5 [10]. Our results may differ because we have described longitudinal changes in %BF using less precise although clinically easier to assess measures of %BF. As in males, there were no changes in WC when adjusted for height (WC/Ht), implying that the increases in WC were due to normal growth.

Our results indicate that BMI >95th percentile and WC/Ht >0.5 are associated with excess adiposity. However, the use of WC alone does not accurately assess excess adiposity because it does not account for normal growth.

This study has several important strengths. Multiple clinical measures of adiposity were obtained from a large sample of normal weight of black and non-black youth at each PS. The overlapping sampling time frame permitted the construction of a synthetic longitudinal cohort providing the ability to assess changes over advancing puberty. Frequent follow-up enabled more accurate determination of the progression of puberty in this cohort. The different measures used reflect different components of adipose tissue, enabling examination of the changes in total, subcutaneous, and visceral fat during puberty in primarily normal weight boys and girls. By performing these analyses on a primarily normal weight cohort, we were able to better examine the so-called normal changes in adiposity during puberty. Our findings may be used to identify early deviations from normal growth among peri-pubertal boys and girls.

A limitation of the study is that the findings only present changes in the measures of adiposity in normal weight of black and non-black youth, and may not be generalizable to more racially and ethnically diverse populations. The use of a synthetic cohort is not as definitive as the use of a longitudinal cohort of 642 children followed up individually from 8 to 18 years of age, although this is an acceptable and novel method for measuring changes over time [13]. Although the sample size in this study was moderately large, the numerous comparisons that were performed required substantial adjustment of the statistical significance level. This adjustment limited the power to detect additional significant trends between Tanner stages or between subgroups. Finally, the findings reflect changes in clinical measures of adiposity during puberty. These clinical measures do not distinguish between visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue, which may bias the relationship between visceral adiposity and CVD risk factors. It is possible that image-based measures of adiposity at each PS would demonstrate different results, as evidenced by the difference in %BF detected by Goulding et al who used DXA [10]. However, imaging methods to assess the quantity and distribution of adipose tissue are still limited to use in a research setting and are not widely used clinically.

Analyses of adiposity measures during puberty in a predominantly normal weight population provide insight into race and gender differences. Each measure of adiposity changed significantly with puberty for at least two race-gender cohorts except WC/Ht, which did not change significantly for any of the race-gender cohorts during puberty. This may indicate that WC/Ht is a valid measure to determine excess visceral adiposity in children and adolescents. Early identification of excess visceral adiposity will enable earlier intervention and possibly reduce the risk of CVD. Increased abdominal circumference is highly correlated with CVD risk in adults; thus, the factors that influence its changes deserve further study [28].

Acknowledgments

Financial support was from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute through Cooperative Agreement U01-HL- 41166 and by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Southwest Center for Prevention Research (U48/CCU609653). Dr. Mihalopoulos was supported by the Primary Care Research Center, the Children’s Health Research Center, the Pediatric Clinical and Translational Research Center, and the Primary Children’s Medical Center Foundation at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of each Project HeartBeat! participant and family. The researchers recognize the support of the Conroe Independent School District and the generous support of The Woodlands Corporation. All people who contributed significantly to the work have been listed as authors or in the Acknowledgements.

References

- 1.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (The INTERHEART Study): Case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. About BMI for Children and Teens. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemieux S, Prud’homme D, Bouchard C, et al. A single threshold value of waist girth identifies normal-weight and overweight subjects with excess visceral adipose tissue. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64:685–693. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.5.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Onat A, Avci GS, Barlan MM, et al. Measures of abdominal obesity assessed for visceral adiposity and relation to coronary risk. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1018–1025. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen W, Punyanitya M, Chen J, et al. Waist circumference correlates with metabolic syndrome indicators better than percentage fat. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:727–736. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S, Kuk JL, Hannon TS, Arslanian SA. Race and gender differences in the relationships between anthropometrics and abdominal fat in youth. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1066–1071. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biro FM, Lucky AW, Simbartl LA, et al. Pubertal maturation in girls and the relationship to anthropometric changes: Pathways through puberty. J Pediatr. 2003;142:643–646. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spyckerelle Y, Gueguen R, Guillemot M, et al. Adiposity indices and clinical opinion. Ann Hum Biol. 1988;15:45–54. doi: 10.1080/03014468800009451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor RW, Grant AM, Williams SM, Goulding A. Sex differences in regional body fat distribution from pre- to postpuberty. Obesity (Silver Spring) doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.399. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goulding A, Taylor RW, Gold E, Lewis-Barned NJ. Regional body fat distribution in relation to pubertal stage: A dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry study of New Zealand girls and young women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64:546–551. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Labarthe DR, Nichaman MZ, Harrist RB, et al. Development of cardiovascular risk factors from ages 8 to 18 in Project Heart Beat! Study design and patterns of change in plasma total cholesterol concentration. Circulation. 1997;95:2636–2642. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.12.2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller WH, Harrist RB, Doyle SR, et al. Body measurement variability, fatness, and fat-free mass in children 8, 11, and 14 years of age: Project Heart Beat! Am J Hum Biol. 1999;11:69–78. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6300(1999)11:1<69::AID-AJHB7>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breslow NE, Lubin JH, Marek P, et al. Multiplicative models and cohort analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 1983;78:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lohman TG, Martorell R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo SM, Roche AF, Houtkooper L. Fat-free mass in children and young adults predicted from bioelectric impedance and anthropometric variables. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:435–443. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/50.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lukaski HC, Bolonchuk WW, Hall CB, Siders WA. Validation of tetrapolar bioelectrical impedance method to assess human body composition. J Appl Physiol. 1986;60:1327–1332. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.4.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Growth and physiological development during adolescence. Annu Rev Med. 1968;19:283–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.19.020168.001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:13–23. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.239.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds EL, Wines JV. Individual differences in physical changes associated with adolescence in girls. Am J Dis Child. 1948;75:329–350. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1948.02030020341006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynolds EL, Wines JV. Physical changes associated with adolescence in boys. Am J Dis Child. 1951;82:529–547. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1951.02040040549002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Base SAS. Procedures Guide program. Version 9.1.3. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krebs NF, Himes JH, Jacobson D, et al. Assessment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S193–S228. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook S, Weitzman M, Auinger P, et al. Prevalence of a metabolic syndrome phenotype in adolescents: Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:821–827. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Ferranti SD, Gauvreau K, Ludwig DS. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in American adolescents: Findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Circulation. 2004;110:2494–2497. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145117.40114.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahn HS, Imperatore G, Cheng YJ. A population-based comparison of BMI percentiles and waist-to-height ratio for identifying cardiovascular risk in youth. J Pediatr. 2005;146:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maffeis C, Banzato C, Talamini G. Waist-to-height ratio, a useful index to identify high metabolic risk in overweight children. J Pediatr. 2008;152:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fox CS, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, et al. Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: Association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2007;116:39–48. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosito GA, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, et al. Pericardial fat, visceral abdominal fat, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and vascular calcification in a community-based sample: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:605–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Eyben FE, Mouritsen E, Holm J, et al. Intra-abdominal obesity and metabolic risk factors: A study of young adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:941–949. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Relationship of body size and shape to the development of diabetes in the diabetes prevention program. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:2107–2117. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mooradian AD, Haas MJ, Wehmeier KR, Wong NC. Obesity-related changes in high-density lipoprotein metabolism. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1152–1160. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sironi AM, Pingitore A, Ghione S, et al. Early hypertension is associated with reduced regional cardiac function, insulin resistance, epicardial, and visceral fat. Hypertension. 2008;51:282–288. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.098640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]