Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) is currently the standard of care for most patients with high-risk acute leukemias and some other hematologic malignancies. Although HCT can be curative, many patients who undergo allogeneic HCT will later relapse. There is, therefore, a critical need for the development of novel post-HCT therapies for patients who are at high risk for disease recurrence following HCT. One potentially efficacious approach is adoptive T-cell immunotherapy, which is currently undergoing a renaissance that has been inspired by scientific insight into the key issues that impeded its previous clinical application. Translation of the next generation of adoptive T-cell therapies to the allogeneic HCT setting, using donor T cells of defined specificity and function, presents a unique set of challenges and opportunities. The challenges, progress and future of adoptive T-cell therapy following allogeneic HCT are discussed in this review.

Keywords: allogeneic transplantation, central memory, graft versus leukemia, immunotherapy, T cells

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) can be curative and is the standard of care for many chemotherapy-refractory and high-risk hematologic malignancies including acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoid leukemia, chronic lymphoid leukemia (CLL), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Unfortunately, a significant fraction of patients who undergo allogeneic HCT will later relapse, and the development of novel post-HCT therapies for patients who are at high risk for disease recurrence following HCT is an important objective of current research [1]. The pre-HCT radiation and/or chemotherapy that are administered to the recipient to enable donor hematopoietic stem cell engraftment also provide potent anti-tumor activity, particularly when delivered at myeloablative intensity. However, seminal studies have shown that patients who received allogeneic HCT with T-cell-replete grafts from HLA-matched sibling donors had a lower incidence of relapse compared with those who received T-cell-depleted grafts [2,3]. This result confirmed predictions from murine models that illustrated the importance of donor T cells for a curative graft-versus-leukemia/tumor (GVL/T) effect and led to the logical assumption that T-cell immunotherapy may be a powerful tool to prevent and treat disease relapse after HCT. Although donor T cells are critical to the GVL/T effect, their presence is also associated with a significantly increased risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) [2]. Thus, a major challenge is how to implement T-cell therapy to prevent or treat relapse after allogeneic HCT in such a way as to avoid GVHD.

Several advances in distinct areas of research have culminated in the development of strategies for utilizing the adoptive transfer of T cells to selectively target malignant cells. These advances include the identification of target antigens on cancer cells, the development of tools for introducing genes that encode tumor-targeting receptors into T cells and insights into T-cell biology that may provide for more reproducible engraftment and function after adoptive T-cell transfer. Thus, adoptive T-cell immunotherapy can, in principle, provide precise control of the targeted antigen and rapidly increase the number and avidity of T cells in the patient that can recognize the tumor. The application of adoptive T-cell therapy after allogeneic HCT, particularly with genetically modified donor T cells, presents unique challenges because the patients are typically receiving immunosuppressive drugs, and the infusion of donor T cells has the potential to cause GVHD. Here, the authors review current efforts to define appropriate targets for adoptive T-cell therapy to treat hematologic malignancies and establish platforms for graft engineering and gene transfer to facilitate safe and effective T-cell therapy in allogeneic HCT recipients.

Candidate tumor antigens for T-cell therapy after allogeneic HCT

Theoretically, T-cell immunotherapy can be designed to target molecules that are expressed on chemotherapy and radiotherapy-resistant cancer cells, including cancer stem cells, thus eliminating the subset of tumor cells that is most likely to survive the intense conditioning given to allogeneic HCT recipients and result in relapse [4–6]. Ideally, tumor antigens targeted by T cells should be expressed only by the tumor to avoid on-target toxicity to healthy tissues; however, in practice, many candidate tumor antigens are overexpressed self antigens that are also present in normal tissues. Two broad classes of molecules are now being intensively investigated as targets for T-cell therapy. The first consists of peptide antigens that are processed from intracellular proteins expressed in the tumor, presented in association with MHC molecules and recognized by the αβ T-cell receptor. The second class of molecules are cell surface molecules that can be targeted by synthetically designed receptors, which typically consist of a single-chain variable fragment from a monoclonal antibody linked to T-cell signaling moieties and are introduced into T cells as a transgene. Such chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) confer MHC-independent recognition of tumor cells and thus avoid the problem of MHC loss that has been shown to be a mechanism for tumor escape from T cells after allogeneic HCT and in other settings [7].

MHC-dependent tumor-associated antigens

MHC-dependent antigens are peptides anchored to the cleft between the α-1 and α-2 domains of MHC class I molecules or the α-1 an β-1 domains of MHC class II molecules. MHC molecules are polymorphic; therefore, a given MHC-dependent antigen can only be presented by the subpopulation of allogeneic HCT recipients who express the corresponding MHC allele.

Self-antigens overexpressed in hematologic malignancies

Several nonpolymorphic self-proteins that are expressed at high levels in hematologic malignancies and relatively low levels in normal cells can be targets for T-cell immunotherapy in both the allogeneic HCT and non-HCT settings (Table 1) [8–25]. An important advantage of overexpressed self antigens for T-cell immunotherapy is that they may be expressed in a wide range of hematopoietic malignancies and solid tumors and therefore have broad applicability. However, the presentation of self antigens on normal tissues poses a risk of toxicity, and self-tolerance mechanisms restrict the repertoire of reactive T cells present in vivo to those with low-affinity T-cell receptors (TCRs). The isolation of high-avidity T cells for tumor-associated self antigens can be even more challenging in patients with malignancy because the tumor may further promote their deletion or result in functional impairment [26]. As discussed later in this review, the problem of low affinity can be overcome by transferring genes into T cells that encode TCRs selected or modified to have higher affinity for the antigen. This approach can reveal unanticipated problems. Survivin is highly expressed in many malignancies and was once viewed as an attractive candidate antigen; however, this protein is expressed in activated T cells, and T cells endowed with a high-affinity survivin-specific TCR commit fratricide and cannot be propagated in vitro [27].

Table 1.

Antigen targets for immunotherapy of hematological malignancies after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

| Antigen class | Example | Tumor expression | Ref. |

|

| |||

| MHC-dependent | |||

|

| |||

| Overexpressed self antigens | WT1 | AML, ALL, NHL | [6,11,29,30,131–137] |

| Proteinase 3 | AML, CML | [8–10] | |

| Survivin | AML, ALL, CML, CLL, NHL, MM | [12,13] | |

| hTERT | AML, ALL, CML, CLL, NHL, MM | [14,15] | |

| RHAMM | AML, CML | [16–18] | |

| PRAME | ALL, AML, CML | [19–21] | |

| CYPB1 | AML, ALL, NHL, MM | [22] | |

| Immature laminin receptor protein | AML, ALL, CLL, NHL | [23] | |

| Neutrophil elastase | AML, CML | [24] | |

| CCNA1 | AML | [138] | |

|

| |||

| Tumor specific | BCR–ABL | CML and Ph+ ALL | [33,34] |

| PML/RARα | APL | [35] | |

| ETV6–AML | B-ALL | [36] | |

| FLT3 mutations | AML | [37,38] | |

| Immunoglobulin (idiotype or shared framework regions) | NHL, MM | [41,43] | |

|

| |||

| Viral antigens | EBNA3A, 3B, 3C | PTLD | [53,54] |

| LMP-2 | Hodgkin’s lymphoma | [56,57] | |

|

| |||

| Minor histocompatibility antigens – hematopoietic | HA-1 (HMHA1) | Hematopoietic malignancies | [139,140] |

| HA-2 (MYO1G) | Hematopoietic malignancies | [141,142] | |

| LRH-1 (P2X5) | Hematopoietic malignancies | [143] | |

| ACC1 and ACC2 (BCL2A1) | Hematopoietic malignancies | [144,145] | |

| ACC6 (HMSD) | Hematopoietic malignancies | [146] | |

| SP110 | Hematopoietic malignancies | [147] | |

| LB-LY75-IK | Hematopoietic malignancies | [148] | |

| HEATR1 | Hematopoietic malignancies | [86] | |

| T4A (TRIM42) | Hematopoietic malignancies | [149] | |

| CD19 | ALL, CLL, B-cell NHL | [150] | |

| HB-1H and HB-1Y | ALL, CLL, B-cell NHL | [151,152] | |

|

| |||

| MHC-independent | |||

|

| |||

| Antigens targeted by chimeric antigen receptors | CD19 | ALL, CLL, B-cell NHL | [78–80,89] |

| CD20 | CLL, B-cell NHL | [153,154] | |

| CD22 | CLL, B-cell NHL | [155] | |

| CD23 | CLL, B-cell NHL | [156] | |

| CD30 | Hodgkin’s lymphoma, T-cell lymphoma | [157] | |

| CD70 | Subtypes of B-cell NHL, T-ALL, Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, MM, Hodgkin’s lymphoma | [158] | |

| κ-light chain | MM, B-cell NHL, CLL | [159] | |

| ROR-1 | CLL, mantle cell lymphoma, subset of ALL | [160] | |

| CD33 | AML | [161] | |

ALL: Acute lymphoid leukemia; AML: Acute myeloid leukemia; APL: Acute promyelocytic leukemia; B-ALL: B-cell ALL; CLL: Chronic lymphoid leukemia; CML: Chronic myeloid leukemia; MM: Multiple myeloma; NHL: Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; Ph+: Ph-positive; PTLD: Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder; T-ALL: T-cell ALL.

Despite the disadvantages of many self antigens as targets for T-cell therapy, a few have emerged as promising targets for differential recognition of normal and malignant cells and are advancing to clinical trials. Recent studies in a HLA-transgenic murine model demonstrate that high-avidity T-cells specific for Wilm’s tumor 1 (WT1) can be generated in the thymus and acquire a memory phenotype and persist in the periphery without inducing autoimmunity [28]. Moreover, by optimizing in vitro culture conditions for human T cells, it has been possible to isolate T cells from normal human donors with sufficient avidity for self antigens such as WT1 and proteinase 3 in order to recognize leukemia [8,29–31]. WT1 has been ranked as the top priority cancer antigen for translational immunotherapy research and is currently being investigated in clinical trials of T-cell immunotherapy following allogeneic HCT, either using T cells derived directly from the donor or engineered by gene transfer to express a WT1-specific TCR (Box 1) [25,32].

Box 1. Wilm’s tumor 1.

The nonpolymorphic self antigen WT1 is of major interest for the development of adoptive T-cell immunotherapy. WT1 is a zinc-finger transcription factor required for urogenital development and expressed in most acute myeloid leukemias and some acute lymphoid leukemias and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas [132]. WT1 is also expressed at low levels in some normal tissues including CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors and renal podocytes [132]. T cells capable of recognizing an HLA-A*0201-restricted peptide (WT1126–134, sequence RMFNAPYL) are present at higher frequencies in patients after HCT than in normal donors, suggesting that WT1-specific T cells expand after HCT and may contribute to a GVL/T effect [29,133,134]. WT1-specific T cells can lyse human leukemic cells in vitro, inhibit leukemia colony formation and impair leukemia engraftment in immunodeficient mice [6,11,30]. The levels of WT1 expression may enable WT1-specific T cells to distinguish malignant from normal cells. Vaccine trials targeting WT1 in patients with hematological malignancies and solid tumors demonstrate some immunological and clinical responses with tolerable toxicity [135–137]. Adoptive immunotherapy targeting self antigens such as WT1 may be effective alone or combined with vaccination to augment a GVL/T effect. Adoptive immunotherapy trials in HCT recipients with WT1-specific T cells generated by in vitro stimulation of donor T cells with WT1 peptide are currently being performed at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and other centers with encouraging early results [32]. Next-generation adoptive immunotherapy trials employing T cells transduced with viral vectors encoding high-affinity WT1 TCR have also been developed to improve the efficacy and feasibility [59,68].

GVL/T: Graft-versus-leukemia/tumor; HCT: Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; TCR: T-cell receptor; WT1: Wilm’s tumor 1.

Tumor-specific antigens

Novel proteins that arise as a consequence of chromosome translocations and other mutations can provide unique peptide sequences that can be presented by MHC molecules and are potential targets for T-cell immunotherapy (Table 1) [33–38]. Mutated proteins may also contribute to the malignant phenotype, making them particularly attractive targets for immunotherapy, since antigen loss would be expected to decrease. Whole exome sequencing of primary tumor samples is providing new information on the mutational landscape in leukemias and lymphomas and will likely identify novel targets for both pharmaceutical and immunologic approaches to therapy. Because mutant proteins are truly tumor-specific, high-avidity T cells specific for novel peptides derived from these proteins should not have been deleted in normal HCT donors, and T-cell immunotherapy targeting these antigens should have little risk of on-target toxicity to normal cells in the recipient. However, many mutations are unique to the tumors in individual patients or shared by only a subset of patients, which, combined with the necessity that the mutated epitope be appropriately processed and conform to the peptide-binding requirements for the MHC molecules expressed by that patient, will limit the broad applicability of T-cell therapy for many mutation-associated antigens.

B-cell malignancies can express immunogenic determinants derived from the variable regions of the heavy and light chains of the immunoglobulin idiotype (Id) that is uniquely expressed by tumor cells. Id has been validated as a tumor-specific target by vaccination studies in patients with indolent lymphoma that elicited Id-specific T cells, and in some studies improved survival [39,40]. In principle, an Id vaccine could also be used to immunize HCT donors before stem cell collection to elicit tumor-specific T cells that would be transferred with the graft or that could be isolated and expanded for adoptive T-cell transfer [41]. However, exome sequencing has shown that many diffuse large cell lymphomas have mutations in β-2 microglobulin and are class I MHC negative, suggesting that efforts to target this particular tumor with MHC-restricted T cells may be difficult [42]. Moreover, Id is patient specific, thus its applicability as a target for adoptive T-cell therapy is in the realm of personalized medicine [41]. T-cell responses to peptides derived from framework regions within the variable regions of the immunoglobulin that are shared among patients have also been observed, but T-cell immunotherapy trials targeting the immunoglobulin framework peptides have not been reported and could potentially be complicated by toxicity against normal B cells [43].

Minor histocompatibility antigens

Minor histocompatibility (H) antigens, which are HLA-binding peptides derived from endogenous proteins in cells of the HCT recipient that differ from those of the donor due to genetic polymorphisms, represent a unique class of antigens that can only be targeted after allogeneic HCT to promote a GVL/T effect. Recipient cells that are homozygous or heterozygous for a polymorphic minor H antigen allele may be recognized by T cells from an HLA-matched individual who is homozygous for the alternative ‘negative’ allele. Because minor H antigens are not ‘self ’ to the donor immune system, they can elicit high-avidity CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses. Thus, minor H antigens that are expressed on hematopoietic cells including leukemic stem cells represent an important class of tumor-associated antigens for GVL/T responses after allogeneic HCT [44–46]. Unfortunately, many minor H antigens are not rigorously restricted in their expression to hematopoietic cells and specific T cells may recognize nonhematopoietic cells that express the antigen and contribute to GVHD [47–50].

The challenge of separating the GVL/T effect from GVHD after allogeneic HCT may be addressed by only transferring donor T cells that specifically target minor H antigens expressed predominantly or exclusively on hematopoietic cells, preferably following a HCT that is designed to minimize broad alloreactivity such as by complete or selective T-cell depletion of the graft. A Phase I clinical trial of adoptive immunotherapy was performed by our group in which T-cell clones that were specific for minor H antigens that exhibited preferential expression on hematopoietic cells by in vitro cytotoxicity assays against representative target cells were adoptively transferred to patients with leukemia relapse after allogeneic HCT [51]. This study demonstrated that generating minor H antigen-specific T cells in sufficient quantities for therapy was feasible in most patients, and that the transferred T cells infiltrated the bone marrow and mediated antileukemic activity in vivo. However, some patients experienced reversible pulmonary toxicity following the infusion of high doses of T cells that was subsequently shown in one patient to reflect the unexpected expression of the targeted minor H antigen in pulmonary epithelial cells. This on-target toxicity emphasized the need in future trials to focus on only targeting molecularly characterized minor H antigens that can be assayed for transcript expression exclusive to hematopoietic cells [51]. The amino acid sequence, HLA-restriction, gene and chromosomal location of more than 40 human minor H antigens have been determined by the authors and others, and this list is now expanding rapidly as the methodology for gene identification improves [46,52]. Examples of hematopoietic-restricted minor H antigens are provided in Table 1 & Box 2. It is anticipated that a sufficient number of hematopoietic-restricted minor H antigens presented by common HLA alleles will soon be identified and make it feasible to begin T-cell immunotherapy trials targeting antigens with a defined and desirable tissue distribution. Clinical trials of post-HCT vaccination to elicit T cells against hematopoietic-restricted minor H antigens have also been initiated but are not yet reported.

Box 2. HA-1.

HA-1 is a nonamer peptide (VLHDDLLEA, called HA-1H) that arises as a consequence of a single nucleotide polymorphism in the HMHA1 gene and is currently the most attractive minor histocompatibility antigen to target in clinical trials of T-cell immunotherapy after allogeneic HCT. HA-1 is restricted in expression to hematopoietic cells, presented by a common HLA allele (HLA-A*0201) and has a balanced phenotypic distribution [140]. The immunogenicity of HA-1H relates to the relatively lower affinity and less stable binding of the corresponding nonimmunogenic sequence, or ‘null allele’ (VLRDDLLEA, called HA-1R) to HLA-A*0201 due to the relatively large size of the R compared with the H amino acids, and to steric and electrostatic clashes of R with the D pocket residues of the HLA molecule [162,163]. Binding of TCRs to HA-1R is also minimal or nonexistent [162]. HA-1-specific T cells lyse leukemic blasts and prevent the growth of leukemic progenitors in vitro [164–166]. Several studies show a temporal correlation between clinical response of leukemia and the presence of HA-1 specific T cells in donor blood (detected by MHC/peptide tetramer analysis and other techniques) following allogeneic HCT with or without donor lymphocyte infusion [166–168]. There is low-to-absent gene expression of HA-1 in nonhematopoietic cells [169–171], HA-1H-positive non-hematopoietic cells are not recognized by HA-1H-specific T cells in cellular assays [48], and HA-1H-specific T cells do not induce tissue damage when cocultured with HA-1H positive skin in an explant model [172]. It should be noted that hematopoietic cells of recipient origin may remain in the patient’s tissues for 2–3 months after HCT, and one study observed a temporal relationship between the presence of HA-1-specific T cells and acute GVHD [173]. The safest time for the delivery of adoptive T-cell therapy targeting HA-1 may be beyond the first 3 months after HCT.

GVHD: Graft-versus-host disease; HCT: Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; TCR: T-cell receptor.

Viral antigens expressed by hematopoietic tumors

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated post-HCT B-cell lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) can develop after allogeneic HCT, nearly exclusively in patients who receive a T-cell-depleted HCT or T-cell-depleting monoclonal antibodies. PTLD tumors express the EBV antigens, EBNA3A, 3B and 3C which, unlike the EBV antigens expressed by EBV-associated malignancies that develop in immunocompetent hosts, are highly immunogenic and can be effectively targeted by EBV-specific T cells. Polyclonal EBV-specific T cells derived from HCT donors were effective in both preventing and treating established EBV-associated PTLD after allogeneic HCT [53,54]. The potential to rapidly treat PTLD with stored, partially HLA-matched, ‘third-party’, EBV-specific T cells may increase feasibility and broaden the applicability of this approach; however, additional studies are needed to determine if these cells will persist sufficiently long enough to provide durable tumor regression [55]. Other EBV-associated tumors such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma have been treated with EBV-specific T cells [56,57]; however, these tumors are less responsive than PTLD, in part due to the lower immunogenicity of the expressed EBV antigens, and incorporation of T-cell therapy after allogeneic HCT for these diseases has not been reported.

Targeting MHC-restricted antigens by TCR α & β gene transfer

One of the major limitations of targeting MHC-dependent tumor antigens after allogeneic HCT is that tumor-reactive T cells are present at an extraordinarily low frequency in normal HCT donors, and their isolation often requires repetitive antigen stimulation and a long duration of culture to generate sufficient numbers of T cells for therapy. The long culture process may drive T cells toward an exhausted effector phenotype and compromise therapeutic efficacy. One promising approach to rapidly derive tumor-reactive T cells is to use gene transfer technology to introduce genes that encode the TCR α- and β-chains from previously isolated tumor-specific T-cell clones. There are several potential advantages of TCR gene transfer for immunotherapy following allogeneic HCT, including improved feasibility and short culture duration due to the availability of TCRs as ‘off the shelf ’ reagents; the potential to select TCRs with sufficiently high avidity to confer lysis of malignant hematopoietic cells; and the ability to direct the transfer of the TCR into T cells selected for particular functional characteristics to improve T-cell persistence in vivo and for defined antigen specificity of the endogenous TCR to minimize the risk of GVHD.

TCR gene transfer has been successful for generating T cells that are effective in murine models of adoptive immunotherapy [58,59], and the first human trials of TCR gene-modified T cells to treat metastatic melanoma have been performed with some success [60,61]. The most attractive antigens to target with TCR gene transfer for initial translation in the allogeneic HCT setting are WT1 and the hematopoietic-restricted HA-1 minor H antigen [62–68]. Clinical trials of adoptive immunotherapy using allogeneic HCT donor T cells engineered to express WT1-specific TCRs have been developed by our group and others and will open in the near future [67,68]. Similarly, progress has been made in efforts to transduce allogeneic donor T cells with TCRs specific for HA-1 and clinical trials are expected to open shortly [66].

There are limitations of TCR gene transfer including mis-pairing of the introduced and native TCR chains leading to low expression of the desired complex, or mispaired complexes that are potentially autoreactive; competition for the CD3 coreceptor between the gene-transferred TCR with the native TCR or mixed TCR dimers leading to reduced function of the introduced antigen-specific TCR; and inefficient gene transfer and unstable transgene expression. Potentially harmful neo-reactivity, including HLA class I and II alloreactivity and auto-reactivity, has been observed in human T cells in vitro as a consequence of mispairing of the gene-transferred minor H antigen or tumor-specific TCR α- or β-chains with native TCR chains [69]. Of greater concern was the observation in murine models that a lethal GVHD-like syndrome developed as a result of TCR mispairing [70]. TCR mispairing can be reduced by modifying the introduced α and β chains to increase their pairing with each other [69,71–74], or by knockdown of the endogenous TCR β-chain through the introduction of a TCR β-chain-specific zinc-finger nuclease or siRNA [59,75,76]. Alternatively, TCR α- and β-genes can be introduced into γ/δ T cells that lack endogenous αβ chains [64,77].

MHC-independent surface antigens

Many tumors have downregulated presentation of MHC molecules and/or MHC-dependent antigens to escape immune recognition, and this will confer resistance to immunotherapy with MHC-restricted T cells. Indeed, loss of tumor expression of the entire mismatched MHC haplotype has been demonstrated to be a common mechanism responsible for immune escape and relapse after haploidentical HCT [7]. These data suggest that novel approaches that do not rely solely on MHC-restricted T cells may be needed to prevent post-HCT relapse. CARs, whose specificity is governed by a single-chain-variable fragment comprising the heavy and light chains of a tumor-reactive antibody linked to an intracellular T-cell signaling moiety, were developed to overcome downregulation of MHC expression on tumors and to allow targeting of antigens regardless of the HLA type of the T-cell donor or recipient. Introduction of a transgene encoding a CAR into T cells can redirect their specificity to protein, glycolipid, carbohydrate and other cell surface antigens, and the inclusion of an ‘in-line’ activation domain from one or more costimulatory molecules in the CAR allows T cells to respond in the absence of costimulatory ligands on the tumor.

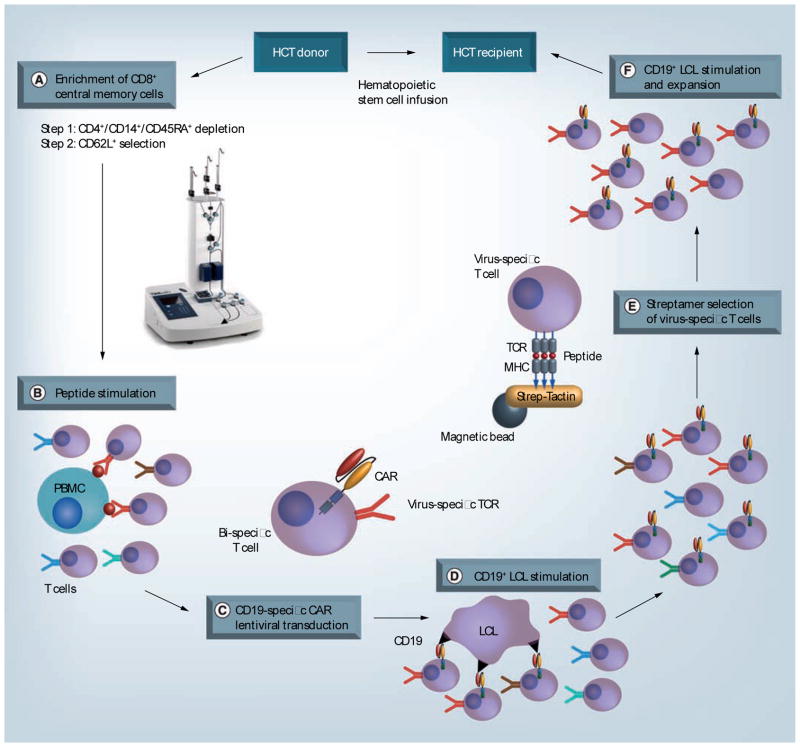

CARs have been constructed to target several distinct surface molecules expressed on hematopoietic malignancies (Table 1). CAR-modified T cells have not yet been used in the allogeneic HCT setting, but impressive results in a small number of patients with refractory CLL treated with autologous T cells modified with a CD19-specific CAR incorporating a 4-1BB costimulatory domain illustrates the potential to incorporate CAR-modified T cells as an effective post-HCT therapy to prevent or treat relapse [78,79]. Just as with the introduction of TCR genes into allogeneic donor T cells, it will be essential with CAR gene transfer to know the specificity of the endogenous TCR in modified cells to avoid infusing potentially alloreactive T cells and causing GVHD. The strategy that the authors’ laboratory has pursued involves selectively transducing donor cytomegalovirus (CMV) or EBV-specific T cells to express the tumor-reactive CAR, since virus-specific donor T cells have been adoptively transferred without causing GVHD (Figure 1) [80]. Clinical trials of CAR-modified T cells following allogeneic HCT are expected to begin accruing in the near future and should assist in defining both the potential for efficacy and limitations of this approach.

Figure 1. Strategy for genetically retargeting donor virus-specific central memory T cells for treatment of CD19+ malignancies after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. (A).

CD8+ TCM cells were selected from donor PBMC using a two-step immunomagnetic selection on the CliniMACS device (picture used with permission from Miltenyi Biotec). Clinical grade monoclonal antibody bead conjugates that are specific for CD45RA, CD4 and CD14 were used first for depleting cells bearing these markers, followed by positive selection of CD62L+ cells. (B & C) TCM-enriched cells are stimulated with immunogenic Epstein–Barr virus or cytomegalovirus peptides and exposed to the CD19 CAR lentivirus to induce selective proliferation and transduction of virus-specific T cells. (D) CAR-specific T cells are expanded by stimulation with irradiated CD19+ antigen-presenting cells. (E) Virus-specific T cells are then purified by selection with MHC class I streptamers to minimize potential contamination with alloreactive T cells in the T-cell product. (F) Final expansion of the T-cell product for infusion. Total time for cell manufacturing is approximately 30 days.

CAR: Chimeric antigen receptor; HCT: Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; LCL: Lymphoblastoid cell line; PBMC: Peripheral blood mononuclear cell; TCM: Central memory T cell; TCR: T-cell receptor.

Strategies to improve the persistence of donor T cells transferred after allogeneic HCT

One of the challenges in autologous adoptive T-cell immuno-therapy is elucidating the factors that govern the persistence of transferred T cells. Although formidable in the autologous setting, the challenges to achieving durable engraftment may be even greater when in vitro expanded allogeneic T cells are transferred after HCT to patients who may be receiving immunosuppressive drugs to prevent or treat GVHD. Strategies to generate and support T cells that are not exhausted from prolonged in vitro culture and restimulation are being developed; however, the allogeneic setting provides many pitfalls that hinder the implementation of the same approaches used in autologous T-cell transfer. Here, the authors will review some of the current approaches to improve in vivo survival of adoptively transferred T cells and discuss their applicability after allogeneic HCT.

Selection of T-cell subsets for therapy

Heritable cell-intrinsic qualities are increasingly being recognized for their importance in determining the capacity of effector T cells to persist in vivo after in vitro stimulation, culture and adoptive transfer. In conjunction with gene transfer techniques to redirect T-cell specificity to tumor antigens, this now makes tumor immunotherapy using distinct subsets of engineered T cells both desirable and feasible. Conventional TCR αβ+ T cells for adoptive transfer can be isolated from the naive T-cell subset (TN; CD45RA+ CD45RO− CD62L+) or from the antigen-experienced memory T cell (TM) subset, which, in turn, can be broadly partitioned into central memory (TCM; CD45RO+ CD62L+) or effector memory (CD45RO+, CD62L-) subsets [81]. Studies in the laboratory in nonhuman primates and in mouse models have demonstrated that CMV-specific CD8+ effector T cells (TE) derived from TCM cells have a superior capacity to persist in vivo after adoptive transfer compared with those derived from T effector memory cells [82,83]. CD8+ TN cells have also been proposed as an effective precursor population from which to derive TE cells for adoptive transfer [84]. However, TN cells may be more prone to induce GVHD after allogeneic HCT than their TM counterparts, suggesting this subset is best avoided in the allogeneic setting in the absence of a proven suicide mechanism [85,86]. Recent studies have also identified a distinct subset of CD8+ memory T cells, termed memory stem cells that like TCM, express CD62L and CD95, but have retained expression of CD45RA, and demonstrated that TE cells derived from this subset may be superior to TCM [87]. This subset clearly has promise for use in gene transfer and adoptive therapy but clinical applications in allogeneic HCT will require improved methods for rapidly isolating these rare T cells, as well as careful analysis of the potential for alloreactivity. Taken together, these data suggested that CD8+ TCM-derived TE cells selected for a defined endogenous TCR specificity to avoid alloreactivity may be optimal for initial studies in the allogeneic HCT setting.

Much of the focus in cancer immunotherapy has been on CD8+ T cells; however, animal models show that CD4+ T cells facilitate the persistence and function of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells in part through production of IL-2 [88]. Encouraging clinical responses to coinfusion of CAR-modified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have been observed in human trials, although the role of individual CD4+ subsets in anti-tumor activity has not been dissected [78,79,89]. We have evaluated the coinfusion of distinct subsets of CD4+ T cells with CD8+ CAR-modified T cells in vitro and in animal models and demonstrated differences in their capacity to promote proliferation of tumor-specific CD8+ cells [Hudecek M, Pers.Comm.]. The capacity to genetically retarget T cells with either a CAR or TCR provides the opportunity to selectively endow defined subsets of T cells with the ability to recognize a common cognate tumor antigen [90], facilitating the analysis of cell products that contain both CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell subsets in future immunotherapy protocols.

Bispecific T cells

Adoptive transfer of allogeneic donor T cells with specificity for viral antigens can reconstitute persistent immunity to pathogens after allogeneic HCT and does not increase the incidence of GVHD [91,92]. This suggests that virus-specific T cells that are isolated from the donor and genetically retargeted to a tumor antigen may provide durable tumor immunity with minimal risk of GVHD compared with infusion of unselected TN or TM sub-sets. An additional advantage is that such T cells could receive proliferative and survival signals due to in vivo viral reactivation that are independent of tumor-derived antigen and the tumor microenvironment. Methods for rapidly selecting and transducing virus-specific T cells have been developed by our group, and this approach will soon be tested after allogeneic HCT using donor EBV- and CMV-specific TCM-derived TE cells that are engineered to express a CD19-specific CAR (Figure 1). This approach could also be used in conjunction with TCR gene transfer to confer MHC-dependent tumor recognition [80].

Optimizing HCT platforms to reduce post-HCT immunosuppression

An obstacle that could impede the persistence, function and efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-reactive T cells after allogeneic HCT with T-cell replete bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) grafts is the pharmacological immuno-suppression that is required to prevent and treat GVHD. This limitation could be overcome by utilizing stem cell grafts that are depleted of alloreactive T cells, thus eliminating the risk of GVHD and the need for immunosuppressive drugs. One approach is to employ adoptive transfer of tumor-reactive T cells in settings where complete T-cell depletion of the stem cell graft is used to prevent GVHD. However, complete T-cell depletion results in delayed immune reconstitution and a high risk of opportunistic infection. The authors are conducting a clinical trial to evaluate the selective depletion of CD45RA+ TN cells from PBSC grafts for the prevention of GVHD. This trial was prompted by results in several different murine HCT models that showed that the allogeneic stem cell grafts that contained TN cells caused severe GVHD compared to those that contained only TM cells [85,93–97]. Limiting dilution analysis of human T-cell subsets showed that the frequency of minor H antigen-specific T cells was significantly higher in the TN compared with the TM subset, suggesting that selective TN-depletion may similarly reduce GVHD in humans while preserving the transfer of pathogen-specific immunity contained in the TM pool [86]. The authors have developed a clinical scale procedure for rigorously depleting PBSC of TN and demonstrated that CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses to a range of pathogens are retained in the TN depleted PBSC. The strategy of CD45RA+ T-cell depletion for reducing GVHD in humans is now being tested in a clinical trial, and if successful, will provide an improved platform for adoptive immunotherapy with tumor-specific T cells.

Several other approaches to selective depletion of alloreactive T cells from stem cell grafts have been evaluated in clinical trials [98–106]. In vitro allodepletion strategies typically involve allostimulation of the T-cell component of the HCT graft in vitro followed by the depletion of cells expressing activation markers using immunomagnetic beads, immunotoxins or florescent-activated cell sorting or by photodynamic purging [107]. In two clinical trials, donor lymphocyte infusions were allodepleted using an anti-CD25 immunotoxin and administered following a T-cell-depleted haploidentical HCT. The incidence of significant acute and chronic GVHD was low and functional T-cell responses were observed in patients receiving ≥105 allodepleted T cells/kg [98,101]. In HLA-identical donor HCT, the administration of approximately 108 anti-CD25 allodepleted T cells/kg with CD34+ stem cells resulted in acute GVHD in 46% of patients suggesting that more efficient allodepletion strategies may be required in this setting [100]. Photodynamic purging of alloactivated T cells was also found to be inefficient and incompletely effective in preventing GVHD following HLA-identical HCT [103–105]. Further improvement in the efficacy of selective in vitro allodepletion strategies may be achieved by using immunomagnetic beads or immunotoxins conjugated to multiple activation markers [108], or by combining in vitro allodepletion with a second safety mechanism such as transfection of the T cells in the PBSC product with a suicide gene (see the section ‘Strategies to eliminate transferred T cells’) [106].

Transplant strategies for the depletion of alloreactive T cells in vivo are also being investigated. One such approach is the administration of cyclophosphamide early after allogeneic HCT to promote tolerance in alloreactive host and donor T cells leading to suppression of both graft rejection and GVHD after allogeneic HCT. High-dose cyclophosphamide on days 3 and 4 after infusion of unmanipulated bone marrow results in low rates of severe acute and chronic GVHD both in nonmyeloablative haploidentical HCT, in which case additional pharmacological immunosuppression is required following cyclophosphamide, and in myeloablative HLA-matched related or unrelated donor bone marrow transplant, in which case additional anti-GVHD pharmacotherapy is not essential [109–111]. Building on the post-transplant cyclophosphamide backbone, additional novel methods of inducing immunological tolerance in the allogeneic HCT setting are under investigation. A recent publication reported minimal GVHD and concurrent acceptance of renal allografts, among five patients who received haploidentical hematopoietic stem cells and ‘facilitating cells’ with a single dose of post-HCT cyclophosphamide and additional short-term pharmacological immunosuppression, although unfortunately the derivation or composition of the stem cell or facilitating cell products were not described in detail [112].

Generation of T cells that are resistant to post-HCT immune suppression

Several groups, including the authors’, are developing strategies to endow T cells with resistance to immune-suppressive drugs including calcineurin inhibitors, mycophenolate mofetil and corticosteroids to enable their use in post-HCT settings where immunosuppression is necessary. T cells have been rendered resistant to calcineurin inhibitors using siRNA to knock down the 12 kDa FKBP12 or by engineering T cells to express calcineurin mutants [113,114]. Similarly, introduction of a variant inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH2) gene has been used to render T cells resistant to mycophenolate mofetil [115]. The authors’ research group has employed zinc-finger nuclease technology to knock out the glucocorticoid receptor in T cells to render them resistant to corticosteroids used in the treatment of GVHD [Gardner R, Pers. Comm.]. These approaches, which entail some risk, continue to be evaluated in animal models and have not yet been subjected to clinical evaluation.

Improving persistence through cytokine support & lymphodepletion

Once activated and expanded ex vivo, T cells are susceptible to apoptosis, and many clinical trials have administered IL-2 in vivo after cell transfer to promote T-cell survival and persistence. However, IL-2 administration is nonselective and promotes expansion of regulatory T cells that could interfere with anti-tumor activity of transferred T cells. Strategies to increase autocrine cytokine production, such as inclusion of ‘in-line’ costimulatory domains in CAR-modified T cells may be preferable to exogenous cytokine support [116]. Alternative approaches for preferential signaling in transferred T cells include transduction of T cells with cytokine encoding genes [117], chimeric cytokine receptors designed to amplify cytokine signaling and provision of cytokines in cell-bound nanoparticles [118].

The γ-chain cytokines other than IL-2 may also have a role, as suggested by the improvement in T-cell persistence observed after the deliberate induction of lymphopenia to augment endogenous levels of IL-7 and IL-15 prior to autologous T-cell therapy [119,120]. In the HCT setting, conditioning therapy and infusion of allogeneic grafts should increase the availability of cytokines; however, in contrast to the autologous setting, additional exogenous systemic cytokine support after allogeneic HCT has greater potential to be detrimental due to the risk of cytokine-induced proliferation of donor alloreactive T cells and induction of GVHD.

Costimulation

The capacity of T cells to proliferate and persist in response to antigen in vivo is in part dependent upon their expression of costimulatory molecules, such as CD28, 4-1BB or OX40. To optimize the persistence of adoptively transferred T cells, one can select T-cell subsets that constitutively express costimulatory molecules or alternatively, costimulatory molecules alone or with their corresponding ligands can be introduced by genetic modification. Human CAR-modified T cells that incorporate a CD28 costimulatory domain exhibit better persistence after autologous T-cell transfer than CAR-modified T cells expressing only a CD3ζ endodomain [121]. The incorporation of a 4-1BB costimulatory domain in a CD19-specific CAR may be one of the factors responsible for the impressive expansion of transferred T cells and clinical efficacy in advanced CLL [78,79]. Much remains to be done to define the optimal design of CARs to increase survival, proliferation and effector function, but the ability to evaluate signals from molecules such as CD28, 4-1BB, OX40 and NKG2D to overcome the absence of costimulatory molecule expression on tumor cells may be a key advantage for CAR-modified T cells.

Minimizing toxicity of T-cell transfer after allogeneic HCT

The incorporation of strategies that employ gene transfer to derive more potent T cells in order to enhance anti-tumor activity suggests that toxicity may emerge as a significant problem both with autologous and allogeneic T-cell products.

On-target toxicity

Serious adverse events have been observed after autologous T-cell therapy, primarily as a consequence of ‘on-target’ recognition of the tumor antigen by transferred T cells. Destruction of large tumor masses by autologous CD19-specific CAR-modified T cells has resulted in tumor lysis syndrome in patients with advanced CLL [78,79]. These patients also have prolonged and perhaps permanent depletion of normal B cells, the long-term consequences of which remain to be determined. Three patients developed severe colitis due to cognate interaction between transferred carcinoembryonic antigen TCR-modified autologous T cells and carcinoembryonic antigen expressed on colonic tissue [122], and fatal pulmonary toxicity was reported in a patient in whom autologous ERBB2-specific CAR-modified T cells reacted with ERBB2 expressed on pulmonary epithelium [123].

There is less experience transferring donor T cells after allogeneic HCT, however pulmonary toxicity was observed in three allogeneic HCT recipients after the infusion of minor H antigen-specific T cells. In one of these patients, the toxicity correlated with expression of the cognate antigen in lung epithelium [51].

Off-target toxicity

Transient, infusion-related toxicity that is independent of target antigen recognition is frequently reported after adoptive T-cell transfer, and typically consists of chills, fever and occasionally myalgias and transient hypoxia shortly after infusion. Infrequently, serious toxicities have been reported, including one death that was attributed to a culture-negative sepsis-like syndrome [89,124]. Transfer of T cells into allogeneic HCT recipients carries additional risks to those imposed by autologous T-cell transfer. Transfer of unselected polyclonal allogeneic T cells that express a diverse TCR repertoire carries the potentially serious risk of induction of severe GVHD. While GVHD is a possibility after any allogeneic T-cell infusion, the risk appears to be low when polyclonal T cells specific for viruses, such as EBV and CMV, are administered, in part due to their relatively restricted TCR repertoire compared with unselected TN or TM cells [91,92]. The strategy of selecting virus-specific T cells for transduction of a tumor-reactive CAR or TCR is feasible and should minimize the risk of GVHD due to allogeneic T-cell transfer when bone marrow or PBSC are the graft sources. Generation of gene-modified highly enriched virus-specific T-cell fractions from cord blood units, where the repertoire has not been primed to viral antigens, is likely to be more problematic.

Strategies to eliminate transferred T cells

Toxicity after T-cell infusions and the potential risk of GVHD when T cells are used after allogeneic HCT suggest that strategies to eliminate the transferred T cells in the event of toxicity would be desirable. Conditional suicide genes that induce T-cell death in response to an appropriate trigger can be introduced into transferred T cells. A promising strategy involves modification of T cells to express human caspase-9 fused to a modified FK506-binding protein (FKBP). In vivo administration of a small molecule, AP1903, induces dimerization of the introduced caspase-9 (iCasp9), leading to activation of caspases-3, -6 and -7 and induction of apoptosis [125]. Proof of principle for this strategy was recently demonstrated in four patients who had undergone haplo-identical HCT and received allodepleted donor T cells modified to express the iCasp9. AP1903 administration rapidly reversed grade I cutaneous GVHD that developed after HCT and normalized hyperbilirubinemia due to presumed hepatic GVHD within 24 h [106]. While these results are promising, it remains to be seen if more severe grade II–IV GVHD that develops after infusion of iCasp9-modified T cells can be efficiently abrogated by AP1903.

Herpes simplex type I viral thymidine kinase has also been used as a suicide gene; however, its use in allogeneic HCT recipients was problematic as depletion of T cells causing GVHD was incomplete [126–128]. This approach also precludes the administration of ganciclovir to treat or prevent CMV infection, and the transgene can be immunogenic [129]. A recently reported strategy for regulating T-cell survival after adoptive transfer involves incorporating in the transgene a truncated human EGF receptor (EGFRt), that lacks the intracellular signaling domain, and the portions of the extracellular domain for binding EGFRt ligands, but retains in the extracellular domain the epitope recognized by the pharmaceutical monoclonal antibody, Erbitux® that mediates both antibody-dependent cytotoxicity and complement-dependent cytotoxicity [130]. Thus, EGFRt enables antibody-mediated selection of transduced T cells in vitro and may be used for in vivo depletion of transduced T cells by administration of Erbitux. This strategy has not yet been subjected to testing in humans. The elimination of transferred T cells could be effective in treating toxicities such as GVHD that develop relatively slowly and may improve the safety profile of allogeneic T-cell infusions. However, some serious adverse events after adoptive T-cell therapy have occurred remarkably quickly, raising the concern that current suicide or antibody mediated depletion strategies may not act with sufficient rapidity to reverse toxicity.

Expert commentary

Adoptive immunotherapy is entering a new era where the results of preclinical studies are now being rapidly translated to the clinic. Scientific advances have provided insights into many of the key issues that previously impeded clinical applications and technical developments are improving the feasibility and pace of clinical trials. Key advances in the last few years include the identification of T-cell subsets with the potential for prolonged persistence following adoptive transfer and the technical ability to genetically modify T cells with tumor-targeting TCRs or CARs to confer anti-tumor specificity.

Translation of the next generation of adoptive T-cell therapies to the allogeneic HCT setting using donor T cells of defined specificity and function presents a unique set of challenges and opportunities. In particular, it will be critical to establish platforms for allogeneic HCT that do not require intense immunosuppression to prevent or treat GVHD to provide a hospitable post-HCT environment for immunotherapy, or to endow transferred T cells with resistance to immunosuppressive drugs. The identification of novel minor H antigens that are expressed selectively on hematopoietic cells, including malignant cells, provides a unique opportunity for specific adoptive T-cell therapy that can only be applied after allogeneic HCT. If gene transfer is used to introduce tumor-targeting receptors into donor T cells, it is imperative to know both that the tumor-targeting receptor will not cause on-target toxicity to normal cells and that the endogenous TCR specificities of the engineered cells are not alloreactive to avoid GVHD. These challenges reinforce the need to develop technology that either ensures the elimination of transferred T cells in the case of excessive toxicity or that allows control of the expression of the introduced receptors. These advances will broaden the applicability, efficacy and safety of adoptive immunotherapy in the context of allogeneic HCT, ensuring that the exciting potential of this approach can be realized.

Five-year view

The recent achievement of durable engraftment of adoptively transferred T cells endowed with a CAR and costimulatory molecule provides an extraordinary opportunity to implement novel immunotherapies for cancer and to define the principles required for eradicating both hematopoietic malignancies and solid tumors. Advances in methods for selection of T cells with defined characteristics, T-cell stimulation and culture, genetic engineering and nanotechnology are likely to further improve the potency of T-cell therapy and allow investigators to dissect at high resolution the in vivo interactions between engineered tumor-reactive T cells and tumor cells in the tumor microenvironment. The development of more favorable allogeneic HCT platforms for transferring donor tumor-reactive T cells remains an unmet challenge that must be overcome to improve the use of adoptive therapy in this setting.

As the efficacy of T-cell therapy improves, so too will the risk of on-target toxicity, mandating the discovery of novel tumor-specific antigens and development of rapidly effective strategies for regulating tumor cell recognition by transferred T cells either by elimination of infused cells or controlling expression of tumor targeting receptors. Finally, collaboration should be a focus of future investigation so that formal evaluation of new therapies can be accomplished rapidly and in appropriately designed clinical trials.

Key issues.

Adoptive T-cell therapy after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) holds promise for amplifying the graft-versus-leukemia/tumor effect without graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

The post-HCT environment provides a hostile milieu for adoptively transferred T cells. Development of novel HCT platforms that minimize the need for post-HCT immunosuppression to prevent GVHD and/or strategies to endow transferred T cells with resistance to immunosuppressive drugs may be necessary to enhance the efficacy of T-cell therapy after allogeneic HCT.

Separation of graft-versus-leukemia/tumor from GVHD may be accomplished by defining additional hematopoietic-restricted minor histocompatibility (H) antigens to allow targeting of recipient hematopoietic tissue while sparing nonhematopoietic tissue. The applicability of this approach is presently limited because targeting any given minor H antigen requires both a suitable HLA type and genotype in the donor and recipient.

Overexpressed self antigens and tumor-specific antigens represent additional classes of MHC-dependent antigens applicable to T-cell therapy after allogeneic HCT and are suitable for T-cell receptor gene transfer approaches. Several promising antigens are in clinical trials and discovery of additional antigens is a focus of current research.

Genetic modification of T cells to express chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) enables T-cell reactivity to MHC-independent antigens. Utilization of CARs to target MHC-independent antigens avoids tumor immune escape due to down-regulation of MHC-dependent antigen processing and presentation, and incorporation of costimulation in the CAR construct allows efficient T-cell activation in the absence of tumor costimulation.

The capacity of T cells to persist in vivo after in vitro expansion and adoptive transfer appears to be a pre-requisite for effective T-cell therapy. Subsets of T cells that retain heritable intrinsic characteristics that enable their progeny to persist after in vitro expansion and adoptive transfer may be preferred for use in adoptive transfer.

Advances in the development of T-cell therapy have generated some impressive results in pilot clinical trials, but the increased potency of T-cell preparations highlights the potential for on-target toxicity. Systems to eliminate transferred T cells in the event of toxicity are under development.

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact reprints@expert-reviews.com

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the NIH.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

M Bleakley is the Damon Runyon-Richard Lumsden Foundation Clinical Investigator supported in part by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (CI-57-11), and in part by K23CA154532-01 from the National Cancer Institute. CJ Turtle is supported by a K99/R00 NIH Pathway to Independence Award (1K99CA154608-01A1). SR Riddell is supported by NIH grants CA18029, CA114536 and CA136551. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, et al. Reduced mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2091–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horowitz MM, Gale RP, Sondel PM, et al. Graft-versus-leukemia reactions after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1990;75(3):555–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmont AM, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, et al. T-cell depletion of HLA-identical transplants in leukemia. Blood. 1991;78(8):2120–2130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3(7):730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonnet D, Warren EH, Greenberg PD, Dick JE, Riddell SR. CD8+ minor histocompatibility antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte clones eliminate human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(15):8639–8644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao L, Xue SA, Hasserjian R, et al. Human cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for Wilms’ tumor antigen-1 inhibit engraftment of leukemia-initiating stem cells in non-obese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficient recipients. Transplantation. 2003;75(9):1429–1436. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000061516.57346.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vago L, Perna SK, Zanussi M, et al. Loss of mismatched HLA in leukemia after stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):478–488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0811036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molldrem J, Dermime S, Parker K, et al. Targeted T-cell therapy for human leukemia: cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for a peptide derived from proteinase 3 preferentially lyse human myeloid leukemia cells. Blood. 1996;88(7):2450–2457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molldrem JJ, Clave E, Jiang YZ, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for a nonpolymorphic proteinase 3 peptide preferentially inhibit chronic myeloid leukemia colony-forming units. Blood. 1997;90(7):2529–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molldrem JJ, Lee PP, Wang C, et al. Evidence that specific T lymphocytes may participate in the elimination of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Nat Med. 2000;6(9):1018–1023. doi: 10.1038/79526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao L, Bellantuono I, Elsässer A, et al. Selective elimination of leukemic CD34+ progenitor cells by cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for WT1. Blood. 2000;95(7):2198–2203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen MH, Pedersen LO, Capeller B, Bröcker EB, Becker JC, thor Straten P. Spontaneous cytotoxic T-cell responses against survivin-derived MHC class I-restricted T-cell epitopes in situ as well as ex vivo in cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001;61(16):5964–5968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grube M, Moritz S, Obermann EC, et al. CD8+ T cells reactive to survivin antigen in patients with multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(3):1053–1060. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arai J, Yasukawa M, Ohminami H, Kakimoto M, Hasegawa A, Fujita S. Identification of human telomerase reverse transcriptase-derived peptides that induce HLA-A24-restricted antileukemia cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Blood. 2001;97(9):2903–2907. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.9.2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minev B, Hipp J, Firat H, Schmidt JD, Langlade-Demoyen P, Zanetti M. Cytotoxic T cell immunity against telomerase reverse transcriptase in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(9):4796–4801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070560797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greiner J, Ringhoffer M, Taniguchi M, et al. Receptor for hyaluronan acid-mediated motility (RHAMM) is a new immunogenic leukemia-associated antigen in acute and chronic myeloid leukemia. Exp Hematol. 2002;30(9):1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00874-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greiner J, Li L, Ringhoffer M, et al. Identification and characterization of epitopes of the receptor for hyaluronic acid-mediated motility (RHAMM/ CD168) recognized by CD8+ T cells of HLA-A2-positive patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;106(3):938–945. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giannopoulos K, Li L, Bojarska-Junak A, et al. Expression of RHAMM/CD168 and other tumor-associated antigens in patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Int J Oncol. 2006;29(1):95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffioen M, Kessler JH, Borghi M, et al. Detection and functional analysis of CD8+ T cells specific for PRAME: a target for T-cell therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(10):3130–3136. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quintarelli C, Dotti G, De Angelis B, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes directed to the preferentially expressed antigen of melanoma (PRAME) target chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;112(5):1876–1885. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-150045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rezvani K, Yong AS, Tawab A, et al. Ex vivo characterization of polyclonal memory CD8+ T-cell responses to PRAME-specific peptides in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute and chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;113(10):2245–2255. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maecker B, Sherr DH, Vonderheide RH, et al. The shared tumor-associated antigen cytochrome P450 1B1 is recognized by specific cytotoxic T cells. Blood. 2003;102(9):3287–3294. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegel S, Wagner A, Kabelitz D, et al. Induction of cytotoxic T-cell responses against the oncofetal antigen-immature laminin receptor for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2003;102(13):4416–4423. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujiwara H, El Ouriaghli F, Grube M, et al. Identification and in vitro expansion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells specific for human neutrophil elastase. Blood. 2004;103(8):3076–3083. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheever MA, Allison JP, Ferris AS, et al. The prioritization of cancer antigens: a national cancer institute pilot project for the acceleration of translational research. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(17):5323–5337. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molldrem JJ, Lee PP, Kant S, et al. Chronic myelogenous leukemia shapes host immunity by selective deletion of high-avidity leukemia-specific T cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(5):639–647. doi: 10.1172/JCI16398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leisegang M, Wilde S, Spranger S, et al. MHC-restricted fratricide of human lymphocytes expressing survivin-specific transgenic T cell receptors. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(11):3869–3877. doi: 10.1172/JCI43437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pospori C, Xue SA, Holler A, et al. Specificity for the tumor-associated self antigen WT1 drives the development of fully functional memory T cells in the absence of vaccination. Blood. 2011;117(25):6813–6824. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-304568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rezvani K, Grube M, Brenchley JM, et al. Functional leukemia-associated antigen-specific memory CD8+ T cells exist in healthy individuals and in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia before and after stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2003;102(8):2892–2900. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohminami H, Yasukawa M, Fujita S. HLA class I-restricted lysis of leukemia cells by a CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte clone specific for WT1 peptide. Blood. 2000;95(1):286–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molldrem JJ, Lee PP, Wang C, Champlin RE, Davis MM. A PR1-human leukocyte antigen-A2 tetramer can be used to isolate low-frequency cytotoxic T lymphocytes from healthy donors that selectively lyse chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Res. 1999;59(11):2675–2681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bornhäuser M, Thiede C, Platzbecker U, et al. Prophylactic transfer of BCR-ABL-, PR1-, and WT1-reactive donor T cells after T cell-depleted allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;117(26):7174–7184. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-308569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ten Bosch GJ, Toornvliet AC, Friede T, Melief CJ, Leeksma OC. Recognition of peptides corresponding to the joining region of p210BCR-ABL protein by human T cells. Leukemia. 1995;9(8):1344–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clark RE, Dodi IA, Hill SC, et al. Direct evidence that leukemic cells present HLA-associated immunogenic peptides derived from the BCR-ABL b3a2 fusion protein. Blood. 2001;98(10):2887–2893. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Padua RA, Larghero J, Robin M, et al. PML-RARA-targeted DNA vaccine induces protective immunity in a mouse model of leukemia. Nat Med. 2003;9(11):1413–1417. doi: 10.1038/nm949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yotnda P, Garcia F, Peuchmaur M, et al. Cytotoxic T cell response against the chimeric ETV6-AML1 protein in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(2):455–462. doi: 10.1172/JCI3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scholl S, Salzmann S, Kaufmann AM, Höffken K. Flt3-ITD mutations can generate leukaemia specific neoepitopes: potential role for immunotherapeutic approaches. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47(2):307–312. doi: 10.1080/10428190500301306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graf C, Heidel F, Tenzer S, et al. A neoepitope generated by an FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3-ITD) is recognized by leukemia-reactive autologous CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2007;109(7):2985–2988. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-032839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwak LW, Campbell MJ, Czerwinski DK, Hart S, Miller RA, Levy R. Induction of immune responses in patients with B-cell lymphoma against the surface-immunoglobulin idiotype expressed by their tumors. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(17):1209–1215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210223271705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schuster SJ, Neelapu SS, Gause BL, et al. Vaccination with patient-specific tumor-derived antigen in first remission improves disease-free survival in follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(20):2787–2794. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osterroth F, Garbe A, Fisch P, Veelken H. Stimulation of cytotoxic T cells against idiotype immunoglobulin of malignant lymphoma with protein-pulsed or idiotype-transduced dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;95(4):1342–1349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pasqualucci L, Trifonov V, Fabbri G, et al. Analysis of the coding genome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2011;43(9):830–837. doi: 10.1038/ng.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trojan A, Schultze JL, Witzens M, et al. Immunoglobulin framework-derived peptides function as cytotoxic T-cell epitopes commonly expressed in B-cell malignancies. Nat Med. 2000;6(6):667–672. doi: 10.1038/76243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fontaine P, Roy-Proulx G, Knafo L, Baron C, Roy DC, Perreault C. Adoptive transfer of minor histocompatibility antigen-specific T lymphocytes eradicates leukemia cells without causing graft-versus-host disease. Nat Med. 2001;7(7):789–794. doi: 10.1038/89907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bleakley M, Riddell SR. Molecules and mechanisms of the graft-versus-leukaemia effect. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(5):371–380. doi: 10.1038/nrc1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bleakley M, Riddell SR. Exploiting T cells specific for human minor histocompatibility antigens for therapy of leukemia. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011;89(3):396–407. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reinsmoen NL, Kersey JH, Bach FH. Detection of HLA restricted anti-minor histocompatibility antigen(s) reactive cells from skin GVHD lesions. Hum Immunol. 1984;11(4):249–257. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(84)90064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Bueger M, Bakker A, Van Rood JJ, Van der Woude F, Goulmy E. Tissue distribution of human minor histocompatibility antigens. Ubiquitous versus restricted tissue distribution indicates heterogeneity among human cytotoxic T lymphocyte-defined non-MHC antigens. J Immunol. 1992;149(5):1788–1794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niederwieser D, Grassegger A, Auböck J, et al. Correlation of minor histocompatibility antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes with graft-versus-host disease status and analyses of tissue distribution of their target antigens. Blood. 1993;81(8):2200–2208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goulmy E, Gratama JW, Blokland E, Zwaan FE, van Rood JJ. A minor transplantation antigen detected by MHC-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes during graft-versus-host disease. Nature. 1983;302(5904):159–161. doi: 10.1038/302159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warren EH, Fujii N, Akatsuka Y, et al. Therapy of relapsed leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with T cells specific for minor histocompatibility antigens. Blood. 2010;115(19):3869–3878. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spierings E, Hendriks M, Absi L, et al. Phenotype frequencies of autosomal minor histocompatibility antigens display significant differences among populations. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(6):e103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rooney CM, Smith CA, Ng CY, et al. Infusion of cytotoxic T cells for the prevention and treatment of Epstein–Barr virus-induced lymphoma in allogeneic transplant recipients. Blood. 1998;92(5):1549–1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54•.Heslop HE, Slobod KS, Pule MA, et al. Long-term outcome of EBV-specific T-cell infusions to prevent or treat EBV-related lymphoproliferative disease in transplant recipients. Blood. 2010;115(5):925–935. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239186. Describes their long-term experience with infusion of Epstein-Barr virus-specific T cells to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients and demonstrate the feasibility of this approach. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haque T, Wilkie GM, Jones MM, et al. Allogeneic cytotoxic T-cell therapy for EBV-positive posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disease: results of a Phase 2 multicenter clinical trial. Blood. 2007;110(4):1123–1131. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-063008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bollard CM, Gottschalk S, Leen AM, et al. Complete responses of relapsed lymphoma following genetic modification of tumor-antigen presenting cells and T-lymphocyte transfer. Blood. 2007;110(8):2838–2845. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bollard CM, Aguilar L, Straathof KC, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte therapy for Epstein–Barr virus+ Hodgkin’s disease. J Exp Med. 2004;200(12):1623–1633. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stanislawski T, Voss RH, Lotz C, et al. Circumventing tolerance to a human MDM2-derived tumor antigen by TCR gene transfer. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(10):962–970. doi: 10.1038/ni1001-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ochi T, Fujiwara H, Okamoto S, et al. Novel adoptive T-cell immunotherapy using a WT1-specific TCR vector encoding silencers for endogenous TCRs shows marked antileukemia reactivity and safety. Blood. 2011;118(6):1495–1503. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-337089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnson LA, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, et al. Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood. 2009;114(3):535–546. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, et al. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science. 2006;314(5796):126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1129003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heemskerk MH, Hoogeboom M, de Paus RA, et al. Redirection of antileukemic reactivity of peripheral T lymphocytes using gene transfer of minor histocompatibility antigen HA-2-specific T-cell receptor complexes expressing a conserved alpha joining region. Blood. 2003;102(10):3530–3540. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heemskerk MH, Hoogeboom M, Hagedoorn R, Kester MG, Willemze R, Falkenburg JH. Reprogramming of virus-specific T cells into leukemia-reactive T cells using T cell receptor gene transfer. J Exp Med. 2004;199(7):885–894. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van der Veken LT, Hagedoorn RS, van Loenen MM, Willemze R, Falkenburg JH, Heemskerk MH. Alpha beta T-cell receptor engineered gamma delta T cells mediate effective antileukemic reactivity. Cancer Res. 2006;66(6):3331–3337. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heemskerk MH, Hagedoorn RS, van der Hoorn MA, et al. Efficiency of T-cell receptor expression in dual-specific T cells is controlled by the intrinsic qualities of the TCR chains within the TCR-CD3 complex. Blood. 2007;109(1):235–243. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Loenen MM, de Boer R, Hagedoorn RS, van Egmond EH, Falkenburg JH, Heemskerk MH. Optimization of the HA-1-specific T-cell receptor for gene therapy of hematologic malignancies. Haematologica. 2011;96(3):477–481. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.025916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ochi T, Fujiwara H, Yasukawa M. Application of adoptive T-cell therapy using tumor antigen-specific T-cell receptor gene transfer for the treatment of human leukemia. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:521248. doi: 10.1155/2010/521248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xue SA, Gao L, Thomas S, et al. Development of a Wilms’ tumor antigen-specific T-cell receptor for clinical trials: engineered patient’s T cells can eliminate autologous leukemia blasts in NOD/SCID mice. Haematologica. 2010;95(1):126–134. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.006486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Loenen MM, de Boer R, Amir AL, et al. Mixed T cell receptor dimers harbor potentially harmful neoreactivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(24):10972–10977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005802107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bendle GM, Linnemann C, Hooijkaas AI, et al. Lethal graft-versus-host disease in mouse models of T cell receptor gene therapy. Nat Med. 2010;16(5):565–70. doi: 10.1038/nm.2128. 1p following 570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kuball J, Dossett ML, Wolfl M, et al. Facilitating matched pairing and expression of TCR chains introduced into human T cells. Blood. 2007;109(6):2331–2338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-023069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bialer G, Horovitz-Fried M, Ya’acobi S, Morgan RA, Cohen CJ. Selected murine residues endow human TCR with enhanced tumor recognition. J Immunol. 2010;184(11):6232–6241. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sommermeyer D, Uckert W. Minimal amino acid exchange in human TCR constant regions fosters improved function of TCR gene-modified T cells. J Immunol. 2010;184(11):6223–6231. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scholten KB, Kramer D, Kueter EW, et al. Codon modification of T cell receptors allows enhanced functional expression in transgenic human T cells. Clin Immunol. 2006;119(2):135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Okamoto S, Mineno J, Ikeda H, et al. Improved expression and reactivity of transduced tumor-specific TCRs in human lymphocytes by specific silencing of endogenous TCR. Cancer Res. 2009;69(23):9003–9011. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Provasi E, Genovese P, Lombardo A, et al. Editing T cell specificity towards leukemia by zinc finger nucleases and lentiviral gene transfer. Nat Med. 2012;18(5):807–815. doi: 10.1038/nm.2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.van der Veken LT, Coccoris M, Swart E, Falkenburg JH, Schumacher TN, Heemskerk MH. Alpha beta T cell receptor transfer to gamma delta T cells generates functional effector cells without mixed TCR dimers in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;182(1):164–170. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78••.Kalos M, Levine BL, Porter DL, et al. T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(95):95ra73. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002842. Demonstrates the potential for chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell infusions to induce remissions in chronic lymphoid leukemia patients and illustrate the kinetics associated with these responses. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79••.Porter DL, Levine BL, Kalos M, Bagg A, June CH. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103849. Demonstrates the potential for chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell infusions to induce remissions in chronic lymphoid leukemia patients and illustrate the kinetics associated with these responses. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Terakura S, Yamamoto TN, Gardner RA, Turtle CJ, Jensen MC, Riddell SR. Generation of CD19-chimeric antigen receptor modified CD8+ T cells derived from virus-specific central memory T cells. Blood. 2012;119(1):72–82. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-366419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:745–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]