Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a clonal B-cell malignancy characterized by the proliferation of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Despite recent therapeutic advances, MM remains an incurable disease. Therefore, research has focused on defining new aspects in MM biology that can be therapeutically targeted. Compelling evidence suggests that malignant cells have a higher nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) turnover rate than normal cells, suggesting that this biosynthetic pathway represents an attractive target for cancer treatment. We recently reported that an intracellular NAD+-depleting agent, FK866, exerts its anti-MM effect by triggering autophagic cell death via transcriptional-dependent (transcription factor EB, TFEB) and -independent (PI3K-MTORC1) mechanisms. Our findings link intracellular NAD+ levels to autophagy in MM cells, providing the rationale for novel targeted therapies in MM.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, PI3K/MTORC1, TFEB, cancer treatment

Intracellular NAD+ is required in numerous cellular processes as either a coenzyme or a substrate in energy-consuming cellular reactions. In mammals, NAD+ is replenished from nicotinamide (Nam), tryptophan or nicotinic acid (NA), with Nam as the most important and widely available precursor. Indeed nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), the rate-limiting enzyme in the NAD+ synthesis pathway from nicotinamide, regulates cell survival versus death. Tumor cells maintain growth, proliferation and survival due to high levels of aerobic glycolysis and increased turnover of NAD+ (fueled by upregulation of NAMPT), thereby compensating for activation of enzymes that would otherwise consume intracellular NAD+ stores. Thus the NAD+ biosynthesis pathway has emerged as an innovative therapeutic target, since cancer cells appear more susceptible to NAD+-lowering drugs than normal cells. Although reasons for this selectivity are not fully understood, they include aberrant metabolic requirements and increased reliance on NAD+-dependent enzymes in cancer.

Using genetic (lentivirus-mediated gene transfer) and chemical (FK866) approaches, we recently demonstrated that MM cells are dependent on NAMPT activity for their survival. Indeed, we provided experimental evidence that NAMPT inhibition/depletion potently kills MM cell lines and patients cells in vitro, as well as overcomes the protection conferred by the bone marrow microenvironment (IL6, IGF1 or bone marrow stromal cells). Importantly, the chemical specific inhibitor of NAMPT, FK866, reduces MM xenograft tumor growth in vivo. The observations that MM cells are remarkably dependent on NAMPT activity for their survival led us to further characterize the downstream effects of therapeutically targeting NAMPT. Treatment with FK866 does not induce apoptotic death, but rather induces an increased autophagy. Our data confirm the crucial role of autophagy as a survival mechanism in MM cells. Prior studies in MM suggest that moderate autophagy is a prosurvival mechanism, whereas its excess can promote cell death, and autophagy is required for chemotherapy-induced cell death of MM. Accordingly, we reported that FK866 treatment triggers intracellular NAD+ depletion, thereby decreasing survival signals and increasing autophagic MM cell death. Moreover MM cells stably expressing GFP-LC3 show an increased punctate pattern localization of GFP-LC3 after FK866 treatment, further confirming autophagy. Finally NAMPT inhibition also induces cytoplasmic vacuolization and lipidation of endogenous LC3-I to LC3-II, as well as transcription of several autophagy-related genes.

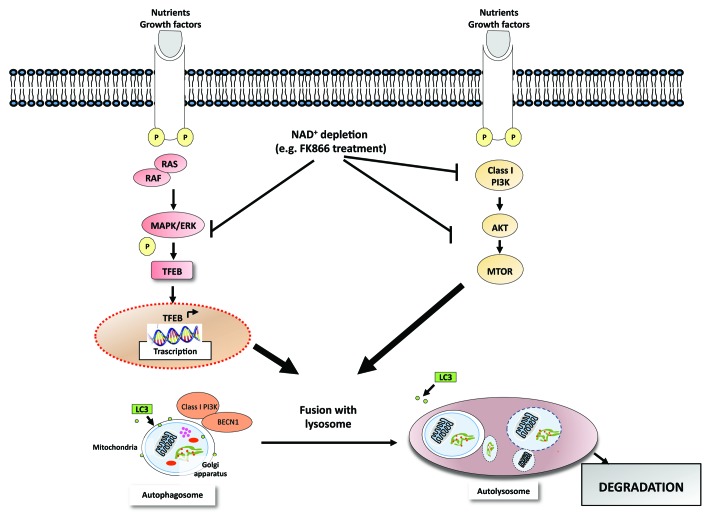

To gain further insight into the molecular mechanisms of FK866-induced MM cell autophagy, we characterized transcriptional-dependent and -independent mechanisms activating autophagy. First, we observed that NAD+ intracellular shortage triggered by FK866 treatment inhibits MTOR signaling, the master negative-regulator of autophagy, along with decreased PI3K and AKT. Thus, dual inhibition of PI3K-MTOR (MTORC1/2) contributes to FK866-induced autophagy in MM cells. However, the observation that FK866 treatment induces transcription of several autophagy genes not related to MTORC1 (including those encoding ATG9B, ATG4A, ATG4B, ATG16L2, MAPLC3, SQSTM1, UVRAG and WIPI) raises the possibility that additional molecular events that are MTORC1-independent may also trigger autophagic MM cell death. Indeed, we found that the inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling (MAPKs) by FK866 treatment stimulates nuclear translocation of TFEB, which coordinates lysosome formation and acts as an inducer of autophagy by upregulating several autophagy-related (Atg) genes. Specifically, MM cells ectopically expressing TFEB (DKK-TFEB) show potent inhibition of MAPK signaling after FK866 treatment, along with TFEB nuclear translocation and Atg activation (Fig. 1). Finally, the contribution of a transcription-dependent mechanism in FK866-induced autophagy in MM cells was further evidenced by a decrease in expression of genes encoding the forkhead box class `O` (FOXO) 3A proteins.

Figure 1. Intracellular NAD+ depletion promotes autophagic cell death of MM cells. The NAMPT inhibitor FK866 depletes NAD+ intracellular stores in MM cells, thereby both blocking MAPKs and inducing translocation of TFEB from the cytoplasm to the nucleus as well as upregulating autophagy-related genes (transcriptional-dependent mechanism). In parallel, intracellular NAD+ depletion also directly inhibits PI3K-MTOR activity (nontranscriptional-dependent mechanism), further inducing autophagy in MM cells.

Our data are consistent with other published studies that reveal a role of NAMPT in the regulation of autophagy in MM cells. Unlike the well-known autophagy-inducers, which inhibit MTORC1, the metabolic cell stress triggered by intracellular NAD+ shortage results in MM autophagic-cell death by a dual mechanism: MAPKs inhibition followed by nuclear localization of TFEB; as well as direct inhibition of the PI3K-MTORC1 pathway. Although we did not observe apoptotic cell death triggered by FK866, it is possible that the pharmacological restriction of NAD+ in MM cells triggers apoptotic signaling, which is limited by concomitant onset of autophagy. Such aborted apoptosis could then switch autophagy into a MM cell death program. In this context, we hypothesize that the metabolic stress resulting from intracellular nutrient starvation (NAD+ shortage) represents the key mechanism for activating cellular energy-sensing pathways implicated in triggering MM autophagic cell death. We also showed that NAMPT inhibition significantly reduces tumor growth in vivo in a murine xenograft model of human MM, with tumors harvested from treated animals exhibiting autophagic-features including proteolytic cleavage of LC3 and MAPK1/3 (ERK2/1) inhibition.

In summary, autophagy-dependent death triggered by reduction of intracellular NAD+ pools represents a novel therapeutic strategy in MM.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (grants RO-1 50947, RO-1 73878), DF/HCC SPORE in Multiple Myeloma (P-50100707); American Italian Cancer Foundation (M.C.); International Multiple Myeloma Foundation and Associazione Cristina Bassi (A.C.). K.C.A. is an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/autophagy/article/22866