Abstract

Primary meningeal melanomatosis is a rare, aggressive variant of primary malignant melanoma of the central nervous system, which arises from melanocytes within the leptomeninges and carries a poor prognosis. We report a case of primary meningeal melanomatosis in a 17-year-old man, which was diagnosed with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (F-18 FDG) PET/CT, and post hoc F-18 FDG PET/MRI fusion images. Whole-body F-18 FDG PET/CT was helpful in ruling out the extracranial origin of melanoma lesions, and in assessing the therapeutic response. Post hoc PET/MRI fusion images facilitated the correlation between PET and MRI images and demonstrated the hypermetabolic lesions more accurately than the unenhanced PET/CT images. Whole body F-18 FDG PET/CT and post hoc PET/MRI images might help clinicians determine the best therapeutic strategy for patients with primary meningeal melanomatosis.

Keywords: Meningeal melanomatosis, F-18 FDG, PET/CT, post hoc PET/MRI

INTRODUCTION

Primary meningeal melanomatosis is a rare, aggressive variant of the primary malignant melanoma of the central nervous system (CNS) that arises from melanocytes within the leptomeninges and carries a poor prognosis (1, 2). Primary meningeal melanomatosis is more common in adults than in children, and has various manifestations, including seizures, symptoms and signs of increased intracranial pressure, psychiatric disturbances, cranial nerve palsies, and spinal cord compression (3, 4). Despite the use of computed tomography (CT), contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology, diagnosis of meningeal melanomatosis is challenging because clinical manifestations, radiologic features, and pathologic findings overlap with a wide variety of other conditions (5-9).

Positron emission tomography (PET), using the radiolabeled glucose analogue, 2-[F-18]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (F-18 FDG), is a diagnostic functional imaging modality based on the detection of increased glucose metabolism of malignant tumors. Integrated PET and CT (PET/CT), a hybrid imaging modality, allows for simultaneous acquisition of metabolic and anatomic imaging data using a single device in a single diagnostic session, and therefore, provides a glucose metabolic rate with morphologic characteristics of lesions at a precise anatomic localization (10, 11). There are no previous reports of F-18 FDG PET/CT in patients with primary meningeal melanomatosis. We report a 17-year-old male diagnosed as primary meningeal melanomatosis, based on histologic evaluation and F-18 FDG PET/CT images, demonstrating leptomeningeal F-18 FDG uptake in the right frontal and temporal lobes.

CASE REPORT

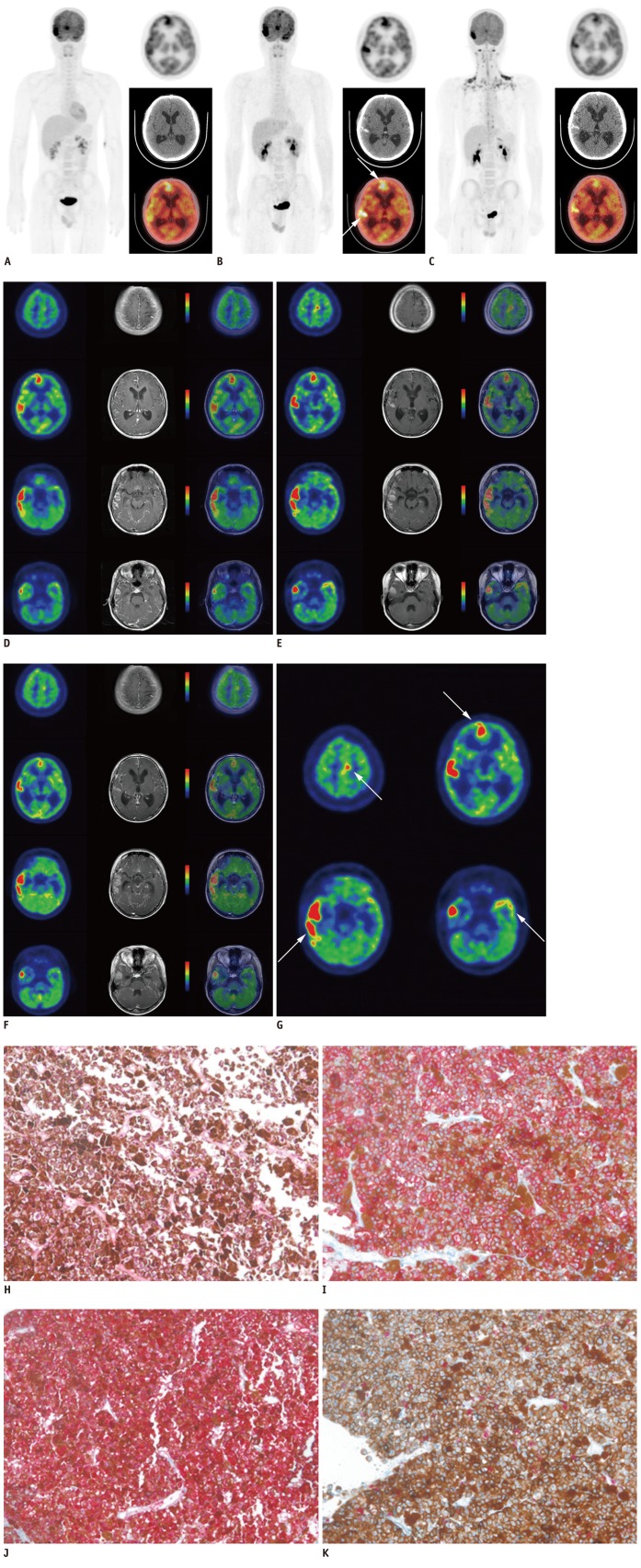

A 17-year-old male, without any relevant medical history, was admitted to our hospital with an acute headache, nausea, and vomiting. The neurologic examination showed mental alertness without any significant focal neurologic signs. The brain CT revealed hyperdense lesions in the right temporal lobe suggesting subarachnoid hemorrhage or non-infectious meningitis. He received non-surgical conservative treatment because CT angiography did not demonstrate any vascular abnormalities. With progressive worsening of the symptoms, brain MRI was performed 3 months later. We used 3.0T MRI system (Signa Excite, General Electric Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) to obtain T1-wighted contrast-enhanced MR images (TR/TE = 550/12) after administration of gadolinium chelates. The imaging showed diffuse thickening of the leptomeninges on the right temporal and frontal lobes, which were hyperintense on T1-weighted MR images and hypointense on T2-weighted MR images, with contrast-enhancement. F-18 FDG PET/CT was also obtained with integrated PET/CT scanners (Discovery STE, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA). CT and PET scans were obtained with the patient in supine position with quiet respiration. CT scan was performed without contrast enhancement in order to generate an attenuation correction map for the PET scan. PET scan was performed with a 3 minutes emission acquisition per bed position. PET images were reconstructed with a 128 × 128 matrix, an ordered subset expectation maximum iterative reconstruction algorithm (4 iterations, 8 subsets), a Gaussian filter of 5.0 mm, and a slice thickness of 3.27 mm. All images were transferred to a dedicated workstation for analysis (Advantage Workstation 4.5, General Electric Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA). The initial whole body F-18 FDG PET/CT scan revealed hypermetabolic lesions, along the leptomeninges on the frontal and temporal lobes bilaterally, but no other hypermetabolic lesions were detected throughout the body (Fig. 1A). Maximum standardized uptake values (SUVmax) were measured in several foci of hypermetabolic leptomeningeal lesions. SUVmax measured in the right temporal, right frontal, left temporal and left frontal lobes was 25.3, 14.7, 7.8 and 6.8, respectively. The PET images were co-registered with contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI images using an Integrated Registration application of GE Advantage Workstation 4.5. The post hoc PET/MRI fusion images revealed a perfect co-localization of the hyperintense lesions on T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI images and hypermetabolic lesions on the F-18 FDG PET/CT images. The post hoc PET/MRI images showed F-18 FDG uptake on PET images corresponding to enhancing lesions on T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI images (Fig. 1D). In addition, we found more lesions in the left frontal and temporal lobes in the post hoc PET/MRI images than the unenhanced F-18 FDG PET/CT images.

Fig. 1.

F-18 FDG PET/CT and post hoc PET/MR images, and microscopic findings of primary meningeal melanomatosis.

A. Initial F-18 FDG PET/CT scan revealed hypermetabolic lesions along leptomeninges on frontal and temporal lobes bilaterally, and no other hypermetabolic lesion in whole body. B. Second pre-treatment F-18 FDG PET/CT scan revealed aggravation of hypermetabolic leptomeningeal lesions (arrows), compared with lesions on initial F-18 FDG PET/CT scan. C. Third post-treatment F-18 FDG PET/CT scan showed decreased F-18 FDG uptake and extent of hypermetabolic leptomeningeal lesions compared with lesions on pre-treatment F-18 FDG PET/CT. F-18 FDG PET/CT = F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography. D. Initial post hoc PET/MR images showed more hypermetabolic leptomeningeal lesions, corresponding to enhancing lesions on T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MR images than unenhanced F-18 FDG PET/CT images. E, G. Pre-treatment post hoc PET/MR images revealed aggravation of hypermetabolic lesions (arrows) corresponded to enhancing lesions on T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MR images, compared with lesions on initial post hoc PET/MRI images. F. Post-treatment post hoc PET/MR images showed decreased F-18 FDG uptake and extent of hypermetabolic leptomeningeal lesions on PET images. Post-treatment contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI also showed slight decrease in size of enhancing leptomeningeal lesions, suggesting partial therapeutic response. F-18 FDG PET/CT = F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography. H. Tumor cells showed eosinophilic cytoplasm with pleomorphic vesicular nuclei and prominent eosinophilic nucleoli. Prominent melanin pigments are also observed (HE, × 200). I. Tumor cells were immunohistochemically strongly positive for HMB-45 (× 200). J. Tumor cells were immunohistochemically strongly positive for S-100 (× 200). K. Ki-67 labeling index of tumor was approximately 10% (× 200). F-18 FDG PET/CT = F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography.

Analysis of the CSF showed the following: 2 white blood cells/µL, with a lymphocyte predominance; a low glucose level, 27 mg/dL; protein, 23 mg/dL; lactate dehydrogenase, 249.2 U/L; and absence of atypical or abnormal cells. CSF analysis was repeated 5 days later, and the results were as follows: 1 white blood cell/µL, with a lymphocyte predominance; low glucose level, 25 mg/dL; protein, 35 mg/dL; and lactate dehydrogenase, 354 U/L. The serum tumor markers, which were measured, including alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, prostate specific antigen, cancer antigen (CA) 125, CA 19-9, and CA 15-3, were all negative. Because the presumptive clinical diagnosis was tuberculosis meningitis, the patient was treated with an anti-tuberculosis regimen and steroids; however, his neurologic symptoms were not relieved.

Because of the diagnostic uncertainty, the patient eventually underwent an open biopsy. Under general endotracheal anesthesia, a small temporal craniotomy was performed on the right side. The exposed dura mater revealed no abnormalities. After incising the dura, however, a dark black solid mass was noted through the translucent arachnoid membrane. The exposed subarachonoid space was completely filled with the dark tumor mass; the flow of CSF was not identified. A small tumor specimen was obtained for tissue diagnosis.

Microscopic examination of the meningeal biopsy stained with hematoxylin and eosin revealed proliferation of polygonal epithelioid tumor cells (Fig. 1H-K). The tumor cells had large pleomorphic vesicular nuclei with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli and dusty intracytoplasmic melanin pigment. Nuclear pleomorphism and mitoses were also noted. The tumor cells were immunohistochemically positive for human melanoma black-45 (HMB-45) and S-100, and the Ki-67 labeling index was approximately 10%. The histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings were consistent with malignant melanoma.

A thorough physical examination, by a dermatologist, did not show abnormal pigmented lesions in the skin and mucous membranes, except for the presence of a small dermal nevus on the chest wall, which was biopsied and confirmed to be a benign nevus. An ocular examination, by an ophthalmologist, excluded any intraocular tumors.

Prior to radio- and chemotherapy, a second pre-treatment F-18 FDG PET/CT performed, at one week after the initial diagnosis, revealed aggravation of the hypermetabolic leptomeningeal lesions, compared with that of the initial F-18 FDG PET/CT images (Fig. 1B). SUVmax of the hypermetabolic leptomeningeal lesions in the right temporal, right frontal, left temporal and left frontal lobes was changed from 25.3, 14.7, 7.8 and 6.8 to 36.5 (+44.3%), 19.4 (+32.0%), 15.0 (+92.3%) and 12.8 (+88.2%), respectively, and the extent of the each lesion was increased. However, no extracranial abnormal hypermetabolic lesions were found on the whole body scan. Brain MRI also demonstrated a progression of the disease. The patient was treated with whole brain radiotherapy and a chemotherapeutic regimen with dacarbazine, carmustine, cisplatin, and tamoxifen. Pre-treatment post hoc PET/MR fusion images also demonstrated that F-18 FDG uptake on PET images was positionally-matched with enhancing lesions on T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI images (Fig. 1E, G). After 8 cycles of chemotherapy, a third F-18 FDG PET/CT scan showed a considerable decrease in F-18 FDG uptake, and the extent of the hypermetabolic leptomeningeal lesions compared with those on pre-treatment F-18 FDG PET/CT (Fig. 1C). SUVmax of the hypermetabolic leptomeningeal lesions in the right temporal, right frontal, left temporal and left frontal lobes was changed from 36.5, 19.4, 15.0 and 12.8 to 18.3 (-49.9%), 10.5 (-45.9%), 7.8 (-48.0%) and 8.1 (-36.7%), respectively. Post-treatment MRI showed a slight decrease in the size of the enhancing leptomeningeal lesions on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR images, which suggested partial therapeutic response like PET. Post-treatment post hoc PET/MR images also showed a considerable decrease in the F-18 FDG uptake and the extent of hypermetabolic leptomeningeal lesions on PET images, positionally-matched with enhancing lesions on T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MR images (Fig. 1F).

DISCUSSION

Melanoma is a malignant neoplasm of melanocytes, which are melanin-producing cells originating from the neural crest and develop predominantly in the skin, but occasionally in the eye, mucous membranes, or the CNS (8). Primary melanocytic tumors of the CNS form a rare disease entity, which can be diffuse or circumscribed, and can be benign or malignant. Primary melanocytic tumors of the CNS are classified into diffuse melanocytosis, melanocytoma, malignant melanoma, and meningeal melanomatosis (12). Diffuse melanocytosis is a diffuse infiltration of the subarachnoid space of the brain and spinal cord by melanocytes (7). Meningeal melanomatosis is the malignant form of the diffuse involvement, and it results from the spread of malignant melanocytes into the leptomeninges and Virchow-Robin spaces with superficial invasion of the brain (7, 9).

Diagnosis of meningeal melanomatosis is a challenging task because signs and symptoms of the disease are variable and overlaps with other CNS diseases, such as lymphoma, leukemia, acute neurosarcoidosis, metastatic carcinoma, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, subacute meningitis, viral encephalitis, and idiopathic hypertrophic cranial pachymeningitis (2). In addition, the pathologic appearance of the disease is similar with that of the primary melanocytic tumors (5, 6). The primary issue in the diagnosis of CNS melanoma is the differential diagnosis between the primary and metastatic melanoma. Hayward proposed the following factors for establishing the diagnosis of a primary CNS melanoma: 1) no malignant melanoma outside the CNS; 2) involvement of the leptomeninges; 3) intramedullary spinal lesions; 4) hydrocephalus; 5) tumor in the pituitary or pineal gland; and 6) a single intracerebral lesion (13). The diagnosis of primary meningeal melanomatosis depends on the diffuse growth pattern and absence of other malignant melanomas, elsewhere (9).

A meningeal biopsy is often the only definitive diagnostic procedure in cases of suspected primary meningeal melanomatosis (9). The gross specimen shows diffuse darkening and thickening of the leptomeninges (2). On microscopic examination, melanomas contain polygonal tumor cells with bizarre nuclei and enlarged eosinophilic nucleoli. Prominent cytoplasmic melanin pigments and numerous mitotic figures are often observed. Though primary meningeal melanomatosis histologically mimics a wide variety of other lesions, including brain metastasis from a malignant melanoma elsewhere in the body, the diffuse growth pattern, found in meningeal melanomatosis, is opposed to metastatic melanoma, which almost always involves localized lesions (9, 14).

Human melanoma black-45 is one of the specific markers for melanoma. It has been reported that the sensitivity of HMB-45 for melanoma ranges from 69-93%, and the expression of HMB-45 is maximal in primary melanoma (77-100%), and less in metastatic melanoma (58-83%) (15). Although HMB-45 is specific for melanoma, HMB-45 is expressed in perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (i.e., angiomyolipomas, lymphangiomyomatosis, and pulmonary sugar tumors), sweat gland tumors, meningeal melanocytomas, clear cell sarcomas of the tendons and aponeuroses, some ovarian steroid cell tumors, some breast cancers, and renal cell carcinomas with a t (6, 11) (p21; q12) translocation (15). However, most of these tumors are usually distinct from melanomas on microscopic examination. S-100 has a high sensitivity for melanoma (97-100%). However, the specificity of S-100 for melanoma cells is limited; S-100 is also expressed in nerve sheath cells, myoepithelial cells, adipocytes, chondrocytes and Langerhans cells, and the tumors derived from these cells (15). The Ki-67 labeling index is typically < 1-2% in melanocytomas and approximately 8% in the primary melanomas (16). In our case, the morphologic features and the results of immunohistochemical studies, such as HMB-45, S-100, and Ki-67, were consistent with malignant melanoma.

The usual brain CT appearance of melanocytic tumors is iso- to hyperdense lesions with homogenous contrast enhancement, with or without abnormal calcifications (17). In general, brain MRI of the tumors demonstrates diffuse thickening of the leptomeninges, which is iso- or hyperintense on T1-weighted images, hypointense on T2-weighted images, and abnormally enhancing on T1-weighted contrast-enhanced images (2, 17, 18). The paramagnetic effect of melanin pigment causes shortening of T1 and T2 relaxation times (7). The radiologic differential diagnosis of leptomeningeal pigmented lesions include pigmented meningioma, melanotic schwannoma, meningeal melanocytoma, primary CNS melanoma, and metastatic melanoma (8).

There is only one previous report involving F-18 PET/CT and primary malignant melanoma in a spinal cord root (18). Furthermore, there have been no reports involving F-18 FDG PET/CT and primary meningeal melanomatosis. Herein, we present a very rare primary meningeal melanomatosis case. Whole body F-18 FDG PET/CT revealed primary hypermetabolic lesions, along the leptomeninges on the frontal and temporal lobes bilaterally; however, no hypermetabolic lesions elsewhere. After radio- and chemo-therapy, post-treatment F-18 FDG PET/CT images revealed a therapeutic response more clearly than the concomitant MRI images. Although solitary MRI is adequate to diagnose and to evaluate the therapeutic response in primary meningeal melanomatosis, F-18 FDG PET/CT can provide quantitative therapeutic response by the change of SUV, as an advantage over MRI. In addition, the post hoc PET/MR images made it easier to correlate between PET and MR images and revealed more lesions than the unenhanced PET/CT images. This is because the sequence MR images, such as T1-weighted images, T2-weighted images, and T1-weighted contrast-enhanced images provided a more accurate anatomic localization of the lesions than unenhanced CT. However, confirmation of diagnosis cannot be made through imaging modalities, such as F-18 FDG PET/CT and MRI, because meningeal melanomatosis mimics a variety of other meningeal lesions in F-18 FDG PET/CT and MR images.

In a study of 257 cutaneous malignant melanoma patients, it was found that F-18 FDG PET was the most accurate staging modality in patients with locoregional metastases, and that F-18 FDG PET findings resulted in a change of surgical plan in 37% of the patients due to the detection or exclusion of distant metastases (19). In this case, whole body F-18 FDG PET/CT could demonstrate that there was no extracranial abnormal hypermetabolic lesion, suggesting distant metastasis because the primary meningeal melanomatosis also showed very high F-18 FDG uptake like other types of malignant melanoma, such as most common cutaneous malignant melanoma. Post hoc PET/MRI made it easier to correctly localize the leptomeningeal lesions, and evaluate the therapeutic response because hypermetabolic leptomeningeal lesions on PET images were positionally-matched with enhancing lesions on T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MR images. Whole body F-18 FDG PET/CT and post hoc PET/MRI images provide a great means by which to plan an appropriate therapeutic strategy and monitoring the therapeutic response, in this case. In the future, the virtue of the fully integrated PET/MRI system will lie in simultaneous acquisition of the metabolic PET information and the broad MR characteristics.

Conclusion

Primary meningeal melanomatosis is a very rare, aggressive variant of the primary malignant melanoma of the CNS, which presents a diagnostic challenge. In this report we have presented a case of primary meningeal melanomatosis with F-18 FDG PET/CT and post hoc F-18 FDG PET/MR fusion images. Wholebody F-18 FDG PET/CT was helpful in ruling out the extracranial origin of melanoma lesions and in assessing the therapeutic response in the early phase. Post hoc PET/MR fusion images facilitated the correlation between PET and MR images, and demonstrated the hypermetabolic lesions more accurately than that of the unenhanced PET/CT images. Whole body F-18 FDG PET/CT and post hoc PET/MR images might help clinicians determine the best therapeutic strategy for patients with primary meningeal melanomatosis.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Grants of the Korean Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (The Regional Core Research Program/Anti-aging and Well-being Research Center) and Nuclear Research & Development Program of National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by Ministry of Education, Science & Technology (MEST; grant code: 2010-0017515) and the grant (A102132) of the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Savitz MH, Anderson PJ. Primary melanoma of the leptomeninges: a review. Mt Sinai J Med. 1974;41:774–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith AB, Rushing EJ, Smirniotopoulos JG. Pigmented lesions of the central nervous system: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29:1503–1524. doi: 10.1148/rg.295095109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaetani P, Martelli A, Sessa F, Zappoli F, Rodriguez R, Baena Diffuse leptomeningeal melanomatosis of the spinal cord: a case report. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1993;121:206–211. doi: 10.1007/BF01809277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sagiuchi T, Ishii K, Utsuki S, Asano Y, Tsukahara S, Kan S, et al. Increased uptake of technetium-99m-hexamethylpropyleneamine oxime related to primary leptomeningeal melanoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:1404–1406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolaides P, Newton RW, Kelsey A. Primary malignant melanoma of meninges: atypical presentation of subacute meningitis. Pediatr Neurol. 1995;12:172–174. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(94)00155-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bang OY, Kim DI, Yoon SR, Choi IS. Idiopathic hypertrophic pachymeningeal lesions: correlation between clinical patterns and neuroimaging characteristics. Eur Neurol. 1998;39:49–56. doi: 10.1159/000007897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zadro I, Brinar VV, Barun B, Ozretić D, Pazanin L, Grahovac G, et al. Primary diffuse meningeal melanomatosis. Neurologist. 2010;16:117–119. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181c29ef8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wadasadawala T, Trivedi S, Gupta T, Epari S, Jalali R. The diagnostic dilemma of primary central nervous system melanoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:1014–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pirini MG, Mascalchi M, Salvi F, Tassinari CA, Zanella L, Bacchini P, et al. Primary diffuse meningeal melanomatosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:115–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bar-Shalom R, Yefremov N, Guralnik L, Gaitini D, Frenkel A, Kuten A, et al. Clinical performance of PET/CT in evaluation of cancer: additional value for diagnostic imaging and patient management. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1200–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czernin J, Allen-Auerbach M, Schelbert HR. Improvements in cancer staging with PET/CT: literature-based evidence as of September 2006. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(Suppl 1):78S–88S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayward RD. Malignant melanoma and the central nervous system. A guide for classification based on the clinical findings. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976;39:526–530. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.39.6.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakhleh RE, Wick MR, Rocamora A, Swanson PE, Dehner LP. Morphologic diversity in malignant melanomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;93:731–740. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/93.6.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, Binder SW. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brat DJ, Giannini C, Scheithauer BW, Burger PC. Primary melanocytic neoplasms of the central nervous systems. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:745–754. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199907000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liubinas SV, Maartens N, Drummond KJ. Primary melanocytic neoplasms of the central nervous system. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:1227–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee NK, Lee BH, Hwang YJ, Sohn MJ, Chang S, Kim YH, et al. Findings from CT, MRI, and PET/CT of a primary malignant melanoma arising in a spinal nerve root. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(Suppl 2):S174–S178. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1285-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bastiaannet E, Oyen WJ, Meijer S, Hoekstra OS, Wobbes T, Jager PL, et al. Impact of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography on surgical management of melanoma patients. Br J Surg. 2006;93:243–249. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]