Abstract

We examined the emission spectra and steady-state anisotropy of tyrosinate anion fluorescence with one-photon (250–310 nm), two-photon (570–620 nm) and three-photon (750–930 nm) excitation. Similar emission spectra of the neutral (pH 7.2) and anionic (pH 13) forms of N-acetyl-L-tyrosinamide (NATyrA) (pKa 10.6) were observed for all modes of excitation, with the maxima at 302 and 352 nm, respectively. Two-photon excitation (2PE) and three-photon excitation (3PE) spectra of the anionic form were the same as that for one-photon excitation (1PE). In contrast, 2PE spectrum from the neutral form showed ~30-nm shift to shorter wavelengths relative to 1PE spectrum (λmax 275 nm) at two-photon energy (550 nm), the latter being overlapped with 3PE spectrum, both at two-photon energy (550 nm). Two-photon cross-sections for NATyrA anion at 565–580 nm were 10 % of that for N-acetyl-L-tryptophanamide (NATrpA), and increased to 90 % at 610 nm, while for the neutral form of NATyrA decreased from 2 % of that for NATrpA at 570 nm to near zero at 585 nm. Surprisingly, the fundamental anisotropy of NATyrA anion in vitrified solution at −60 °C was ~0.05 for 2PE at 610 nm as compared to near 0.3 for 1PE at 305 nm, and wavelength-dependence appears to be a basic feature of its anisotropy. In contrast, the 3PE anisotropy at 900 nm was about 0.5, and 3PE and 1PE anisotropy values appear to be related by the cos6 θ to cos2 θ photoselection factor (approx. 10/6) independently of excitation wavelength. Attention is drawn to the possible effect of tyrosinate anions in proteins on their multi-photon induced fluorescence emission and excitation spectra as well as excitation anisotropy spectra.

Keywords: Tyrosine fluorescence, Anisotropy spectra, Tryptophan, Protein

Introduction

Multi-photon absorption was first proposed as theoretical prediction of two-photon absorption by Maria Göppert-Mayer (Nobel laureate) in her doctoral dissertation in 1931 [1], and verified experimentally shortly after the invention of the laser [2]. Although quantum-mechanical theory of two-photon absorption is rather complex [1, 3, 4], it is understandable phenomenologically taking into account a virtual state produced by interaction of one photon with a ground state, which is the energetically perturbed nonstationary state of the molecule. Consequently, incoming low-energy second photon will have a small but finite probability of being absorbed to the virtual state. Both photons are absorbed simultaneously, and they are not necessarily of the same energy (colour), but sum of their energy values should be equal to the energy of photon required for one-photon excitation (1PE). In this case “simultaneous” means within about 10−18 s. The selection rules for multi-photon excitation (MPE) differ from that for 1PE [5].

Quantum-mechanical considerations showed that probability of such a process is very low, and consequently experimentally-determined absorption cross sections are extremely low as well, e.g. ~10−50 cm4s and ~10−82 cm6s2 for two- and three-photon absorption, respectively. To achieve this one should use photons highly spatially and temporarily overlapped. Resulted fluorescence intensity depends on the squared laser power for two-photon excitation (2PE), cubed (third) power for three-photon excitation (3PE), and the fourth power for four-photon excitation (4PE), and so on, frequently used to control the mode of excitation (e.g. Fig. 1, inset). Due to low cross section values for multiphoton absorptions, the photon density must be at least 106 times higher than that required to generate the same number of one-photon absorptions. Such high density of photons are easily achieved using mode-locked lasers (“Fluorescence spectroscopic methods”), where power of each peak (typically from ~100 fs to ~5 ps fwhm) is high enough (~TW/cm2) to generate 2PE or 3PE, while average power (~10 mW/cm2) is in the same range as for 1PE. This gives rise to significant advantages associated with MPE leading to broad applications of modern fluorescence spectroscopy in biology, biochemistry and biomedical sciences, including analytical assays.

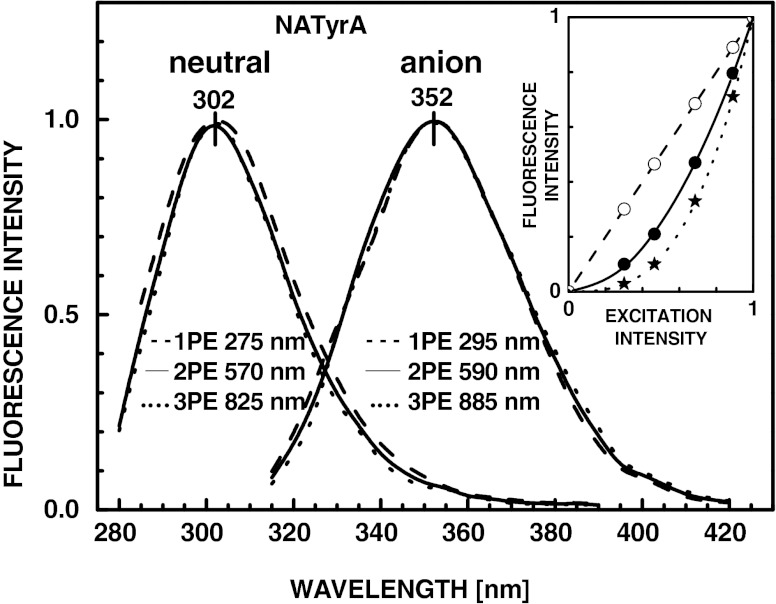

Fig. 1.

Fluorescence emission spectra of the neutral (pH 7.2) and anionic (pH 13) forms of 5 mM NATyrA resulted from one-photon (1PE), two-photon (2PE) and three-photon excitation (3PE), all determined at maxima of the excitation spectra except that for 2PE of the natural form of NATyrA (λexc 570 nm instead of λmax 520 nm), which was limited by the fundamental output (570–620 nm) of rhodamine-6 G dye laser. The inset shows the dependence of the one-photon (- - -), two-photon (____) and three-photon (• • •) induced fluorescence intensity of the anionic form of NATyrA on the intensity of the 295 (white circle), 590 nm (black circle) and 885 nm (black star) incident light. The maximum intensities for 1PE, 2PE and 3PE are all normalized to unity

Since MPE of biomolecules is performed by long-wavelength photons, it offers the potential advantages of decreased photochemical damage and decreased auto-fluorescence. Another powerful advantages of using MPE arise from the physical principle that the multiphoton absorption depends on the i-th power of the excitation intensity, where i is the number of absorbed photons. Consequently, the absorption as well as resulted fluorescence emission are limited to the focal point, and very good three-dimensional resolution is attained without pinholes. Intrinsic confocal MPE in microscopy [6–8] leads to a much higher spatial resolution and lower fluorescence background, and is widely applied in the cell studies [9, 10]. And, most important, MPE offers excitations of different excited states and the possibility of new information content in the steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence spectra ([11], and references cited herein).

Similar 1PE and 2PE emission spectra of the reduced forms of β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and β-nicotinamide mononucleotide (NAMH), and similar fluorescence intensity decay, irrespective of the mode of excitation [12], were observed. The limiting anisotropy values of NADH and NAMH are both larger with 2PE than 1PE and appear to be related by the cos2 θ to cos4 θ photoselection factor of 10/7 independently of excitation wavelength. Depolarization of the NADH fluorescence observed for excitation wavelength below 300 nm for OPE and 600 nm for 2PE is due to an intramolecular interaction with the adenine moiety of NADH. Such depolarization is higher in the tertiary complex of NADH, horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase (LADH) and LADH inhibitor, isobutyramidate, which can be explained by interaction with the protein, including LADH-NADH energy transfer and/or conformational changes in the cofactor molecule. Two-photon cross-sections for NADH [12] in aqueous solution are one to two orders of values lower than for tryptophan (Trp), which suggests that fluorescence from NADH will be moderately difficult to observe with two-photon fluorescence microscopy, and may not interfere with observations of 2PIF of other extrinsic probes used to label cells.

Anisotropy of all fluorophores used so far for protein study is known to depend on the protein environment and to be sensitive to resonance energy transfer and changes in protein conformation. In the case of LADH [13], both nonidentical Trp residues exhibited similar fluorescence spectra for both modes of excitation, but their limiting anisotropy values measured with 2PE from 585 to 610 nm appeared distinct from that obtained with 1PE. These observations strongly suggest that the relative one- and two-photon absorbances of the 1 L a and 1 L b transitions are different for Trp residue(s) in proteins or additional states are probed by 2PE, which may be affected by protein environment [14].

Different transitions are observed for one- and two-photon excitation of the neutral forms of tyrosine (Tyr) and Trp, and higher selectivity for 2PE is obtained, because the two-photon absorption spectrum of Tyr is shifted to shorter wavelength relative to the one-photon absorption spectrum [15, 16]. Such selective excitation was unequivocally confirmed from studies of Tyr-Trp mixtures and proteins containing Trp and Tyr residues [16], where 1PE resulted in dominant tyrosine emission. In the case of 2PE, emission from the same mixture is dominantly from Trp [16].

An important opportunity provided by 2PE is the possibility of obtaining new information about the electronic spectra of fluorophores based on the limiting-anisotropy spectra and potential advantage of higher limiting anisotropy (or initial anisotropy) values, which in principle should be obtained with 2PE. For some probes like 2,5-diphenyloxazole [17] and diphenylhexatriene [18, 19] as well as for NADH and NAMH [12], increased values of 2PE limiting anisotropy (r o), can be explained by a cos4 θ photoselection factor. However, such an increase in r o did not occur for indole or Trp, due to different cross-sections of the 1 L a and 1 L b states for one- and two-photon absorption [20]. This could be interpreted by a red-shift of the 1 L b absorption spectrum for TPE, which results in initial absorption of two photons by the 1 L b state, followed by emission from 1 L a state, for which the transition moment is rotated by 90o [21]. A rather surprising result was observed for the anisotropy spectrum of Tyr [22], where the 2PE anisotropy was slightly negative as compared to near 0.3 for 1PE. Low anisotropy values were also observed for phenol and Tyr-containing peptide (Leu5-enkephaline) [22], and they are not negated by theoretical considerations [22].

The fluorescence emission spectra of proteins which contain Trp, Tyr and Phe residues resembles that of Trp with only minor contribution from tyrosyl residues, and negligible small from phenylalanyl residues [23]. This is based on the relation between their extinction coefficients (ε) and fluorescence quantum yield (Φ) at pH 7: for Trp, at λ max 287 nm ε = 5.6 × 103 M−1 cm−1 and Φ = 0.14; for Tyr, at λ max 278 nm ε = 1.35 × 103 M−1 cm−1 and Φ = 0.2; for phenylalanine, at λ max 257 nm ε = 0.2 × 103 M−1 cm−1 and Φ = 0.025. Proportion between emission from Trp end Tyr residues in proteins show large variations, which are determined by both local and long-range interactions. The latter arise from radiationless energy transfer processes, and the former from the environmental effect on the Trp emission as well as from the ionisation state of the OH group of the phenol moiety in Tyr (Scheme 1). The condition for energy transfer, as shown by Förster [24], are satisfied only for transfer from Tyr to Trp and from Trp to ionised Tyr. Therefore one-photon and multi-photon induced fluorescence of tyrosinate anion turn out to be important for protein fluorescence resulted from both modes of excitation.

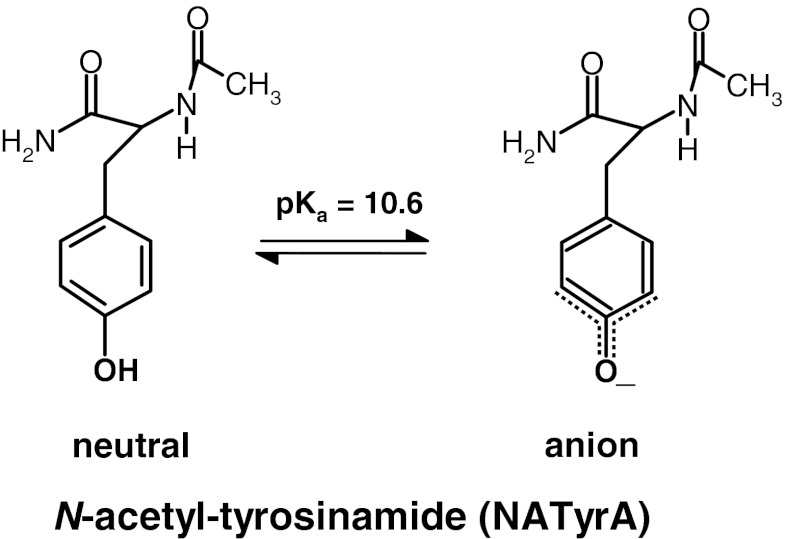

Scheme 1.

Equilibrium between the neutral and anionic forms (pKa 10.6) of N-acetyl-tyrosinamide (NATyrA) in aqueous medium

Remarkably, the tyrosine emission from ribonuclease A (RNase A) containing six Tyr residues, but no Trp, exhibited 10-nm shift to longer wavelengths with 2PE relative to that with 1PE, and exhibited slightly positive limiting anisotropy values [22]. In order to explain these, we have studied here 2PIF emission spectra, and excitation anisotropy spectra of tyrosinate anion, and showed that they may help to interpret both fluorescence emission spectra and excitation anisotropy spectra resulted from 2PE of RNAase, and perhaps another tyrosine proteins.

Experimental

Materials

N-acetyl-L-tyrosinamide (NATyrA, Scheme 1), N-acetyl-L-tryptophanamide (NATrpA), p-bis(o-methylstyryl)benzene and cyclohexane (HPLC grade) were purchased from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI, USA), and used without further purification. Lyophilized ribonuclease (RNase A) from Bovine Pancreas, type II-A (Sigma) was further purified using repeatedly Centriprep-10 Concentrators (Amicon) to exchange buffer and to remove small molecular contaminants (mol. weight <10 kD), which showed absorption and emission in the range 250–290 and 300–380 nm, respectively. Propylene glycol (P.G.) was from (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.2) was made using tris-(hydroxymethyl)-aminomethane hydrochloride (Merck), HCl (Aldrich) and spectral grade water purified using MilliQ plus Ultrapure Water System (Millipore, Austria). All other chemicals were of the highest, spectral-grade quality commercially available. They were checked by UV absorption and/or fluorescence measurements.

Steady-State Absorption and Fluorescence Measurements

Ultraviolet absorption was monitored with a Varian (Australia) Cary 50 recording instrument, fitted with a thermostatically-controlled cell compartment, using 2-, 5- or 10-mm pathlength cuvettes. Steady-state fluorescence emission and excitation spectra were measured with a Spex (USA) FluoroMax spectrofluorimeter, with 2-nm spectral resolution for excitation and emission. NATrpA (20 μM), NATyrA samples (100 μM) or RNase A (50 μM) were prepared in 370–380 μl of 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.2) or 0.1 M sodium hydroxide (pH 13) in 5 × 5-mm Suprasil cuvettes. Fluorescence emission spectra of NATrpA at pH 7.2 and 13 (λ exc 270–320 nm) were recorded in the range 310–450 nm, and that of NATyrA or RNase A at pH 7.2 (λ exc 260–290 nm) and pH 13 (λ exc 280–320 nm) was recorded in the range 290–400 nm and 310–450 nm, respectively. Background emission (~0.5 %) was eliminated by subtracting the signal for buffer.

Concentrations of NATrpA, NATyrA and RNase A were determined spectrophotometrically from their molar extinction coefficients at pH 7.0 for: NATrpA, λ max 287 nm (ε 5.6 × 103 M−1 cm−1), RNase A, λ max 278 nm (ε 9.8 × 103 M−1 cm−1), and NATyrA, λ max 225 nm (ε 8.2 × 103 M−1 cm−1) and λ max 278 nm (ε 1.35 × 103 M−1 cm−1); and at pH 13 for tyrosinate anion: λ max 245 nm (ε 11.0 × 103 M−1 cm−1) and λ max 295 nm (ε 2.35 × 103 M−1 cm−1). Measurements of pH (±0.05) were with an Elmetron (Poland) CP315m pH-meter equipped with a combination semi-micro electrode (Orion, UK) and temperature sensor. The pH values were adjusted for each temperature taking into account that for Tris buffers pH decreases 0.03 unit per °C increase in temperature. On the other hand the pH value in vitrified (−60 °C) glassy solution containing 90 % propylene glycol and 0.1 M sodium hydroxide was much higher than the pKa value of the hydroxyl group of tyrosine residues in this specific environment, because they were almost exclusively ionized. The latter was unequivocally shown by the presence of absorption and fluorescence emission bands typical for the anionic form, and the absence of that for the neutral form of NATyrA (“One-, two- and three-photon induced fluorescence emission spectra” and “One-, two- and three photon fluorescence excitation spectra”). They were similar to the absorption and fluorescence emission spectra of NATyrA in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide at 25 °C.

Fluorescence Spectroscopic Methods

Two-photon excitation was accomplished using the fundamental output (570–620 nm at a 3.795 MHz repetition rate) of a cavity-dumped rhodamine-6 G (R6G) dye laser synchronously pumped by mode-locked Nd:YAG laser (both from Coherent, Santa Clara, USA). For 3PE we used the fundamental output (750–930 nm at a 4.75-MHz repetition rate) of a cavity-dumped Mira 900 Ti:Sapphire laser pumped with Innova 310 argon ion laser, 8 W at 530 nm, CW (both from Coherent, USA).

In order to improve polarization of the excitation beam, it was passed through a Glan-Thompson vertical polarizer, and focused in a sample using a 5-cm focal length lens. For dye laser system, the pulse full width at half-maximum (FWHM) was about 5 ps, and about 2 ps for Ti:Sapphire laser. 1PIF and excitation anisotropy spectra were measured using the same laser systems as for 2PIF or 3PIF equipped additionally with polarization rotator, and frequency doubler or tripler (Inrad, NJ, USA), respectively. The overall system response time was 60 ps FWHM of the impulse response function (IRF). For reliable comparison of the fluorescence emission and excitation anisotropy spectra resulting from these three types of excitation we used an instrument for time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) [25, 26]. The time between exciting pulses was at least 10-fold longer then the measured lifetime, ensuring excitation of a fully equilibrated sample with each laser pulse. Fluorescence detection was based on microchannel-plate photo-multiplier tube (Hamamatsu) detector, thermoelectrically cooled, and set up in the TCSPC mode. The steady-state intensity at each wavelength was obtained by integrating the time-resolved intensity measurements. In addition to increased sensitivity, the use of TCSPC allowed us to demonstrate the absence of components with the same time profile as the excitation pulse.

We used 10 × 5 mm cuvettes placed in the thermostated cell holder, with long axis aligned along the incident light path and a focal point positioned about 5 mm from the surface facing incident light. The position of the cuvette and the lens were adjusted so that the focal point of the laser excitation was located near the observation window. For one-photon experiments we used 5 × 5 mm cuvettes in a 10 × 10 mm cuvette holder and with an excitation and emission positioned near a cuvette corner, which practically eliminated trivial reabsorption occurring for a longer path length. Fluorescence was collected by suprasil lens, filtered from the contaminating excitation using two 7–54 filters and a Corning 300 or 320-nm long-wavelength-pass filter, and passed through an IBH (Edinburgh, Scotland) grating monochromator (4-nm slit bandwidth) and Glan-Thompson polarizer set at the magic angle (54.7°) relative to excitation polarization. Fluorescence spectra were corrected for transmittance of the filters used to isolate the emission. The effect of the intensity of incident light on the one-photon, two-photon and three-photon induced fluorescence intensity (Fig. 1, inset) was measured using neutral density filters to decrease the peak excitation intensity.

For anisotropy determinations, the polarized emission was observed through an interference filter centered at 313 and 340 nm (10-nm band-pass), a Glan-Thompson polarizer and two 7–54 filters. The anisotropy, r, values were determined from the polarized fluorescence intensities as

|

1 |

where F vv is vertically polarized emission intensity with vertically polarized excitation, and F vh is horizontally polarized emission intensity with vertically polarized excitation. The instrument correction factor, g, is equal to g = F hh/F hv, where F hh is horizontally polarized emission intensity with horizontally polarized excitation, and F hv is vertically polarized emission intensity with horizontally polarized excitation. This g factor corrects for a small polarization bias of the optical system and PMT. The g factor was usually within a few percent of 1.0. Anisotropy values presented here are independent of fluorescence emission wavelength.

All measurements were performed at a concentration of 0.1 mM of NATrpA, 5 mM NATyrA and 0.1 mM RNase A at 20 or −60 °C. Signal from the solvent alone, i.e. 20 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.2) or 0.1 M NaOH in the absence or in the presence of 90 % propylene glycol (P.G.) was less then 0.5 % and was subtracted from sample fluorescence. Measurements were not affected by reabsorption, because results remained unchanged when concentration of samples were varied.

Results and Discussion

One-, Two- and Three-Photon Induced Fluorescence Emission Spectra

It is known from long ago [27] that tyrosine residue free in solution (pKa 10.6) or in peptides and proteins (pKa 9.6–10.4) [28] exhibits pKa due to ionization of the tyrosine phenolic hydroxyl. The latter was shown to depend on protein environment [23], and may vary from 9.6 to 10.4 due to interaction with protein interior. In the case of one-photon absorption this ionization shifts the maxima of the absorption and emission spectra from 275 to 302 nm of the neutral form to 295 and 352 nm of the anionic form, and is crucial for interpretation of protein fluorescence.

The intensity of 3PIF of the neutral (pH 7.2) and anionic forms (pH 13) of NATyrA (Scheme 1) is much lower than that of 2PIF and 1PIF. Therefore, for comparison all fluorescence emission spectra were normalized to unity, and they are shown in Fig. 1 for 1PE (275 and 295 nm), 2PE (570 and 590 nm) and 3PE (825 and 885 nm), respectively. The emission spectra are essentially identical for all modes of excitation of the neutral (λ max 302 nm) and anionic forms (λ max 352 nm), indicating that the emission of each form arises from the same lowest excited states with all modes of excitation. The small differences seen in Fig. 1 is within experimental error, which is relatively high due to the weak 2PIF and 3PIF.

Since one-photon absorption of the neutral and anionic forms of NATyrA does not occur above 300 and 320 nm, respectively, it seemed unlikely that 2PE could occur above 600 and 640 nm, i.e. with wavelength used for 3PE. In order to be sure about mode of excitation, we have examined the dependence of the emission intensity on the laser power (Fig. 1, inset). For 1PE the emission intensity is linearly proportional to the intensity of the incident light. In the case of 2PE and 3PE the intensity depends quadratically and cubically on the intensity of the incident light, which show that the observed emission spectra are indeed resulted from a bi- and tri-photonic processes characteristic for 2PE and 3PE, respectively.

It is also worth noticing that in the presence of 0.1 M sodium hydroxide phenolic residue of NATyrA exists almost exclusively in the anionic form in aqueous medium at 25 °C as well as in vitrified (−60 °C) glassy solution containing 90 % propylene glycol. This was unequivocally conformed by the presence of absorption and fluorescence emission bands typical for the anionic form and the absence of that from the neutral form. The ionization of phenolic hydroxyl of NATyrA shifts the maxima of the fluorescence excitation spectrum (Fig. 4) from 275 nm (1PE) to 825 nm (3PE) of the neutral form to 295 nm (1PE) and 885 nm (3PE) of the anionic form. Concomitantly the maximum of the fluorescence emission spectrum is shifted from 302 nm to 352 nm, independently of the mode of excitation (Fig. 1).

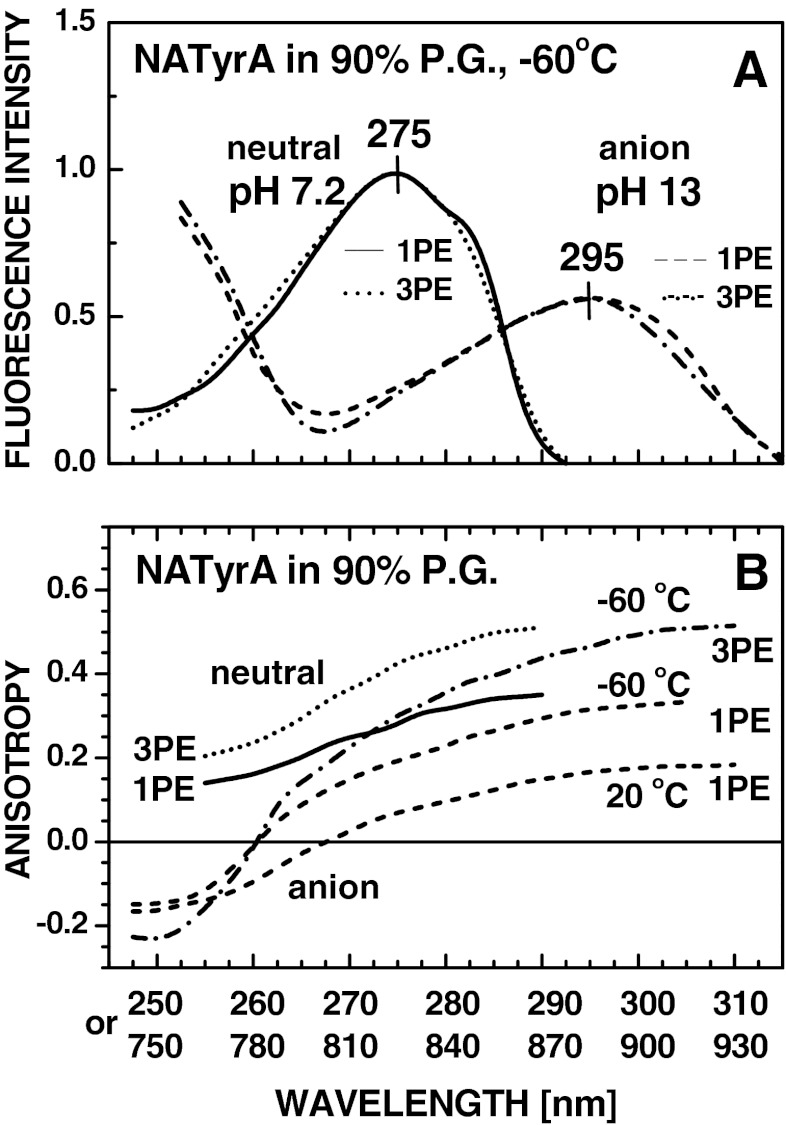

Fig. 4.

Excitation spectra (A) and excitation anisotropy spectra (B) for 1PIF and 3PIF of the neutral (λem 304 nm; 1PE, ___; 3PE, •••) and anionic (λem 350 nm; 1PE, - - -; 3PE, _•_•_) forms of NATyrA in 90 % propylene glycol (P.G.) containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH ~7) or 0.1 M NaOH (see “Steady-state absorption and fluorescence measurements”) at temperatures as indicated

One-, Two- and Three Photon Fluorescence Excitation Spectra

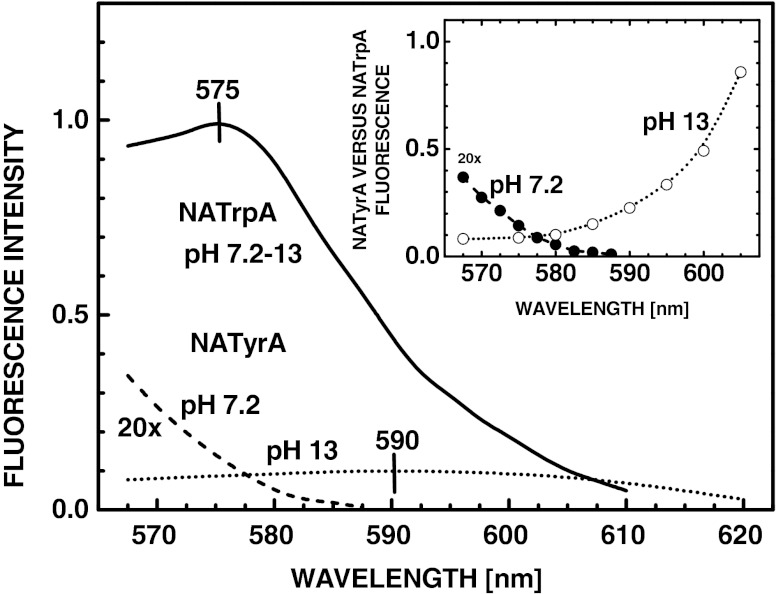

We examined the 2PE spectra of the neutral and anionic forms of NATyrA, and compared them with 2PE spectrum for NATrpA (Fig. 2) determined in the same experiment. Increase of excitation wavelength from 570 to 590 nm diminished 2PE of the neutral form of NATyrA relative to that of NATrpA (Fig. 2, inset). In contrast, 2PE of the NATyrA anion increased from ~10 % of that for NATrpA at 570 nm to ~25 % at 590 nm, and further to ~90 %, at ~610 nm. These data for 2PE could only be examined for a limited range of wavelengths, where there was an adequate intensity from rhodamine-6 G dye laser. In spite of this, these results confirmed the short-wavelength shift (30 ± 3 nm) of the 2PE spectrum of the neutral form of NATyrA relative to that of NATrpA (Fig. 2), as previously reported [15, 16]. Similar excitation spectra were observed for both 1PE and 2PE of NATrpA (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Two-photon excitation spectra of the neutral (pH 7.2, λem 313 nm) (- - -) and anionic (pH 13, λem 350 nm) (• • •) forms of NATyrA relative to that for NATrpA (λem 350 nm) (____). Intensity of NATrpA fluorescence for 2PE at 575 nm is normalized to unity. The inset shows relative two-photon cross sections calculated as relation between the fluorescence intensities of the neutral (__•__) and anionic (. . . ○ . . .) forms of NATyrA, and that for NATrpA measured in the same experimental arrangement

The maximum of excitation spectrum for 2PE of the anionic form of NATyrA is located at 590 nm, similarly to that for 1PE (λmax 295 nm) and 3PE (λmax 885 nm), as soon as appropriate spectra for 2PE (Fig. 2) and 3PE (Fig. 4) are drown in the scale of one-photon energy. In contrast to the blue-shift of the fluorescence excitation spectra for 2PE of the neutral form of NATyrA relative to that for 1PE, essentially identical excitation spectra are obtained for 1PE and 3PE of this form (Fig. 4), which shows that the same electronic state is reached by these modes of excitation.

Two-Photon Cross-Sections

Two-photon cross-sections were determined for 5 mM NATyrA and 0.1 mM NATrpA relative to the two-photon cross-section for the 0.16 mM p-bis(O-methylstyryl)benzene standard in cyclohexane [29], measured in the same experiment. Two-photon cross section for the neutral forms of NATrpA is very low (0.7 %), and for NATyrA (0.014 %) is lower. As expected by Gryczynski at al. [30, 31], three-photon excitations of NATA (0.08 %) and NATyrA (0.006) exhibited even lower cross section values.

Two-photon cross-sections for NATyrA anion at 570–580 nm were 10 % of that for NATrpA and increased to 50 % at ~600 nm, and further to ~90 % at 610 nm (Fig. 2, inset). Concomitantly, two-photon cross-sections of the neutral form of NATyrA decreased from 2 % of that for NATA at ~570 nm to near zero at 585 nm.

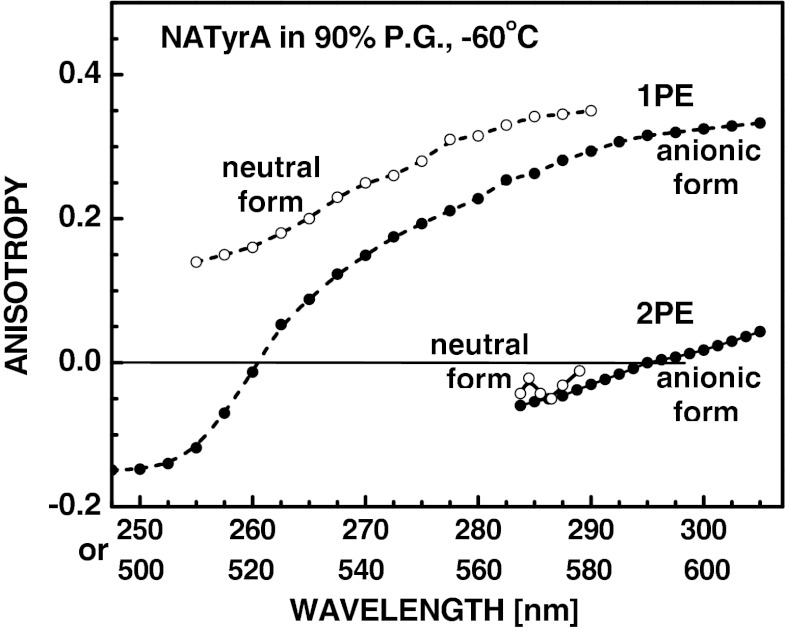

Excitation Anisotropy Spectra of NATyrA Anion

The fundamental anisotropy [Eq. (1)] of the NATyrA anion in vitrified solution (Fig. 3) was ~0.05 for 2PE at 610 nm as compared to ~0.3 for 1PE at 305 nm. The 2PE anisotropy decreased to −0.06 when the wavelength for 2PE was changed to 570 nm, as compared to ~0.25 for 1PE at 285 nm (Fig. 3), while 3PE anisotropy decreased from approx. 0.5 to −0.22, when the wavelength for 3PE was changed from 915 nm to 750 nm (Fig. 4b). Since 2PE with rhodamine-6 G dye laser system is limited to the wavelengths above 565 nm, observation of anisotropy spectra at broader range were performed for 1PE and 3PE (Fig. 4b). Comparison of anisotropy spectra (Fig. 4b) and excitation spectra (Fig. 4a) for 1PIF and 3PIF of the neutral and anionic forms of NATyrA showed that decrease of anisotropy values at shorter wavelengths is independent of temperature, and is caused by overlap with the short-wavelength transition. In contrast to low ( −0.06–0.05) 2PE fundamental anisotropy of the NATyrA anion (Fig. 3), its 3PE anisotropy is higher than 1PE anisotropy (Fig. 4b), and appears to be related by the cos6 θ to cos2 θ photoselection factor (approx. 10/6) independently of excitation wavelength.

Fig. 3.

Excitation anisotropy spectra for 1PIF (- - -) and 2PIF (___) of the neutral (λem 313) (white circle) and anionic (λem 340) (black circle) forms of 5 mM NATyrA in 90 % propylene glycol (P.G.) at –60 °C containing 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH ~7) or 0.1 M NaOH (see “Steady-state absorption and fluorescence measurements”), respectively.

In line with the foregoing, the fundamental anisotropy values of the neutral form of NATyrA are also higher with 3PE than 1PE (Fig. 4b), as previously reported for limiting anisotropy values in viscous aqueous solution [31]. They are related by approx. 1.4 factor, which is lower than the cos6 θ to cos2 θ photoselection factor (approx. 1.67). In contrast, two-photon anisotropy values of the neutral form of NATyrA are near zero (Fig. 3) as compared to near 0.3 for 1PE [22]. Our data for the neutral form of NATyrA displayed the expected low anisotropies for 2PE and the usual high anisotropy for 1PE and 3PE, and added confidence to the anisotropy values observed for the NATyrA anion (Figs. 3 and 4b).

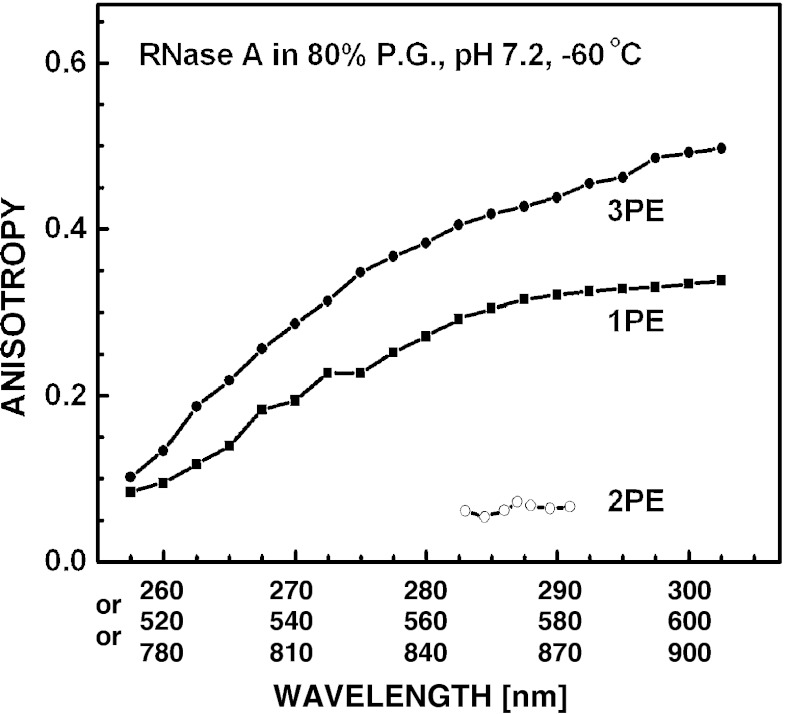

Fluorescence Anisotropy of Tyrosine in RNase A

It was shown previously that tyrosine protein, RNase A, exhibited low (near 0.06) anisotropy values of tyrosyl fluorescence resulted from 2PE, while the anisotropy for 1PE was near the expected values [22]. We next examined the excitation anisotropy spectra of RNase fluorescence for 3PE at neutral pH (Fig. 5), and found that it might be estimated by a weighted (approx. 2:1) arithmetic sum of the 3PE anisotropy spectra of the neutral and anionic forms of tyrosine, respectively. When 3PE wavelength is shifted to the blue (~260 nm) resulted anisotropy values are near 0.1, and similar to that for 1PE. When excitation wavelength increased, difference between anisotropy values was more distinct, and displayed the expected larger anisotropies for 3PE (Fig. 5), related to that for 1PE by the cos6 θ to cos2 θ photoselection factor (approx. 1.67). A possible reason for that could be the presence of several tyrosinate forms in the native protein including tyrosinate anion. The latter may result from an interaction of the OH group of Tyr residues with carboxylate environment leading to tyrosinates with an abnormally low pKa values, as shown for histones H1 [32] and glutathione S-transferases [33, 34]. In line with this, RNase A exhibited the red-shifted tyrosyl fluorescence emission for 2PE, characterized by a maximum at 315 nm and a shoulder at 340 nm, relative to that for 1PE (λ max ~305 nm) [22]. An INDO/S computation predicted the anionic form of tyrosine has about 100-fold stronger two-photon absorptivity than its neutral form. In addition, the absorption (λ max ~295 nm, see also Fig. 4) and emission (λ max ~350 nm, see also Fig. 1) bands are shifted to longer wavelengths, so that even one tyrosinate moiety with an abnormal pKa could dominate two- or three-photon induced fluorescence.

Fig. 5.

Excitation anisotropy spectra (λem 300–340 nm) of 2 mM RNase A in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.2) containing 80 % propylene glycol (P.G.) obtained for 1PE (black square), 2PE (white circle) and 3PE (black circle) at −60 °C

Data presented here suggest that the slightly higher (0.06) anisotropy values observed for RNase A than for free Tyr (near zero) [22] may also result from formation of tyrosinate anions in the native protein. These have red-shifted two-photon absorption and 2PIF similarly to its one-photon absorption and 1PIF (Fig. 1). Additionally, the anion from of NATyrA showed higher cross-section and anisotropy values than its neutral form, further substantiated by theoretical data for phenol [11, 22].

Concluding Remarks

Tyrosine absorbs ultraviolet radiation and contributes to the absorbance spectra of proteins. The extinction of the neutral form of Tyr is only about 1/5 that of Trp at 280 nm, which is the primary contributor to the UV absorbance of proteins depending upon the number of residues of each in the protein [23].

We have shown here that both multi-photon absorption and resulted fluorescence emission of tyrosine residues depend on the pH value. The phenolic hydroxyl of Tyr is significantly more acidic than are the aliphatic hydroxyls of either serine or threonine, having a pKa of about 9.8 in polypeptides. As with all ionizable groups, the precise pKa will depend to a major degree upon the environment within the protein. Tyrosines that are on the surface of a protein will generally have a lower pKa than those that are buried within a protein; ionization yielding the phenolate anion would be exceedingly unstable in the hydrophobic interior of a protein. The acidity of the tyrosine might be of primary importance for catalysis, e.g. Tyr-9 (pKa ~ 8.2) in the case of human and rat glutathione S-transferases [33–35], compared to a pKa of 10.3 for Tyr in aqueous medium. These can be accomplished by the protein environment, including basic and acidic amino acid residues [36] as well as ligands (cofactors) [37].

In light of the foregoing, fluorescence properties of the neutral and anionic forms of tyrosine resulted from both 1PE and MPE appear significant for application of fluorescence methodology in protein studies. They provide reliable method of distinguishing both forms of tyrosine residues as well as quantitative studies of transition between them. Results presented here indicate an important role of the two- and three-photon excitation in fluorescence properties of the neutral and anionic forms of tyrosine free in solution and in protein environments, in the absence and presence of tryptophan residues.

Results of this studies can be utilized towards the effect of tyrosinate anions in proteins on their multi-photon induced fluorescence emission and excitation spectra. Tyrosinate anions may be treated as intrinsic (natural) fluorophore of proteins. They become very important for microscopic studies of cellular and tissue imaging. In fluorescence microcopy 2PE and 3PE provided conditions equivalent to confocal systems by significantly better resolution of excitation. Two and three times higher excitation wavelength in 2PE and 3PE effectively prevents samples against photochemical degradation, which are often observed with high energy 1PE. Unfortunately after very important work of Gryczynski et al. [31] all these were omitted notwithstanding the tremendously high progress observed in MPE methodologies.

The 2PE spectrum of the neutral form of Tyr was ~30-nm blue-shifted relative to 1PE spectrum (275 nm) at two-photon energy (550 nm). This may be caused by effect of the spin-orbit coupling on the forbidden S0-S1 transition in the neutral form of Tyr and concomitant change in orientation of the emission transition moments to approximately perpendicular position versus that of absorption. The latter is also reflected in decrease of the fundamental anisotropy value to near zero [22].

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by the Polish Ministry of Scientific Research and Higher Education (grant No. NN202105536), and in part by the Foundation for Polish Science (grant FASTKIN-97).

Abbreviations

- 1PE

One-photon excitation

- 1PIF

One-photon induced fluorescence

- 2PE

Two-photon excitation

- 2PIF

Two-photon induced fluorescence

- 3PE

Three-photon excitation

- 3PIF

Three-photon induced fluorescence

- FWHM

Full width at half-maximum

- IRF

Impulse response function

- LADH

Liver alcohol dehydrogenase

- MPE

Multi-photon excitation

- NADH

β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced form)

- NAMH

β-nicotinamide mononucleotide (reduced form)

- NATrpA

N-acetyl-L-tryptophanamide

- NATyrA

N-acetyl-L-tyrosinamide

- RNase A

Ribonuclease A

- TCSPC

Time-correlated single photon counting

- Tris–HCl

Tris-(hydroxymethyl)-aminomethane hydrochloride

- Trp

Tryptophan

- Tyr

Tyrosine

References

- 1.Göppert-Mayer M. Ann Phys. 1931;9:273–295. doi: 10.1002/andp.19314010303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser W, Garrett CG. Phys Rev Lett. 1961;7:229–231. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.7.229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazurenko YT. Opt Spectroscopy (USSR) 1971;31:413–414. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClain WM, Harris RA. Excited Sates 3. In: Lim RC, editor. Two-photon spectroscopy in liquid and gases. New York: Academic; 1977. pp. 2–77. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodman L, Rava RP. Acc Chem Res. 1984;17:250–257. doi: 10.1021/ar00103a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denk W, Piston DW, Webb WW. The handbook of biological confocal microscopy. In: Pawley JB, editor. Two-photon molecular excitation in laser-scanning microscopy. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 445–458. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denk W, Strickler JH, Webb WW. Science. 1990;248:73–76. doi: 10.1126/science.2321027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feijó JA, Moreno N. Protoplasma. 2004;223:1–23. doi: 10.1007/s00709-003-0026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.König K. J Microsc. 2000;200:83–104. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2000.00738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piston DW. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:66–69. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(98)01432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kierdaszuk B, Gryczynski I, Lakowicz JR. Topics in fluorescence spectroscopy. In: Lakowicz JR, editor. Nonlinear and two-photon-induced fluorescence. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kierdaszuk B, Malak H, Gryczynski I, Calis P, Lakowicz JR. Biophys Chem. 1996;62:1–13. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4622(96)02182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakowicz JR, Kierdaszuk B, Gryczynski I, Malak H. J Fluoresc. 1996;6:51–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00726726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callis PR. Methods Enzymol. 1997;278:113–150. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)78009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehms AR, Callis PR. Chem Phys Lett. 1993;208:276–282. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(93)89075-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kierdaszuk B, Gryczynski I, Modrak-Wojcik A, Bzowska A, Shugar D, Lakowicz JR. Photochem Photobiol. 1995;61:319–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1995.tb08615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lakowicz JR, Gryczynski I, Gryczynski Z, Danielsen E, Wirth MJ. J Phys Chem. 1992;96:2096–3000. doi: 10.1021/j100186a042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lakowicz JR, Gryczynski I, Kusba J, Danielsen E. J Fluoresc. 1992;2:247–257. doi: 10.1007/BF00865283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakowicz JR, Gryczynski I, Danielsen E. Chem Phys Lett. 1992;191:47–53. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(92)85366-I. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lakowicz JR, Gryczynski I, Danielsen E, Frisoli J. Chem Phys Lett. 1992;194:282–287. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(92)86052-J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eftink MR, Selvidge LA, Callis PR, Rehms AA. J Phys Chem. 1990;94:3469–3479. doi: 10.1021/j100372a022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakowicz JR, Kierdaszuk B, Callis P, Malak H, Gryczynski I. Biophys Chem. 1995;56:263–271. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(95)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lakowicz JR. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. 3. New York: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Förster T. Radiation Res Suppl. 1960;2:326–336. doi: 10.2307/3583604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Connor DV, Philips D. Time-correlated single photon counting. London: Academic; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birch DJS, Imhof RE. Topics in fluorescence spectroscopy. In: Lakowicz JR, editor. Techniques, time-domain fluorescence spectroscopy using time-correlated single photon counting. New York: Plenum Press; 1991. pp. 1–95. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shugar D. Biochem. 1952;52:142–149. doi: 10.1042/bj0520142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X, Cottrell KO, Nordlund TM. Photochem Photobiol. 1989;50:721–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1989.tb02902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy SM, Lytle FE. Anal Chem. 1986;58:2643–2647. doi: 10.1021/ac00126a014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gryczynski I, Malak H, Lakowicz JR. Biospectroscopy. 1996;2:9–15. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6343(1996)2:1<9::AID-BSPY2>3.3.CO;2-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gryczynski I, Malak H, Lakowicz JR. Biophys Chem. 1999;79:25–32. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4622(99)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordano J, Barbero JL, Montero F, Franco L. J Biol Chem. 1993;258:315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibarra CA, Chowdhurry P, Petrich JW, Atkins WM. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19257–19265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301566200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibarra CA, Nieslanik BS, Atkins WM. Biochemistry. 2001;40:10614–10624. doi: 10.1021/bi010672h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atkins WM, Wang RW, Bird AW, Newton DJ, Lu AYH. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19188–19191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bjornestedt A, Sterberg G, Wilderstain M, Board PG, Sinning I, Jones TA, Mannerwik B. J Mol Biol. 1995;247:765–773. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kong KH, Takasu K, Inoue H, Takahashi K. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;184:194–199. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(92)91177-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]