Abstract

Objective

Previous studies reported gender differences for facial emotion recognition in healthy people, with women performing better than men. Few studies that examined gender differences for facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia brought out inconsistent findings. The aim of this study is to investigate gender differences for facial emotion identification and discrimination abilities in patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

35 female and 35 male patients with schizophrenia, along with 35 female and 35 male healthy controls were included in the study. All the subjects were evaluated with Facial Emotion Identification Test (FEIT), Facial Emotion Discrimination Test (FEDT), and Benton Facial Recognition Test (BFRT). Patients' psychopathological symptoms were rated by means of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

Results

Male patients performed significantly worse than female patients on FEIT total, and negative scores. Male controls performed significantly worse than female controls on FEIT total and negative scores. On all tasks, female patients performed comparable with controls. Male patients performed significantly worse than controls on FEIT, and FEDT.

Conclusion

Women with schizophrenia outperformed men for facial emotion recognition ability in a pattern that is similar with the healthy controls. It could be claimed that male patients with schizophrenia need special consideration for emotion perception deficits.

Keywords: Facial emotion, Recognition, Schizophrenia, Gender, Sex

INTRODUCTION

Studies in schizophrenia have uncovered various sex differences in clinical characteristics of the disease. Later onset, less severe negative symptoms, better treatment response and better outcome were reported in female schizophrenia patients compared with male patients.1 Moreover, female patients with schizophrenia were reported to exhibit higher levels of social functioning than male patients.2,3

Facial emotions play a crucial role in social communication and interaction by providing information on individuals' mental state and inclinations. Deficits in the recognition of emotional facial expressions have been widely reported in patients with schizophrenia,4-8 and these deficits have been associated with poor functional outcomes and impaired social functioning.9-13

Previous studies reported sex differences for facial emotion recognition in healthy people, with women performing better than men.14-17 A female advantage at accurately identifying facial expressions which is more prominent for negative emotions than for positive emotions was also indicated.18 In addition, Vassallo et al. reported that females were faster than males in correctly identifying emotional facial expressions.19

Only few studies examined sex differences for facial emotion recognition in patients with schizophrenia and they brought out mixed findings. Scholten et al. reported that emotion perception was disproportionally affected in men with schizophrenia relative to women with schizophrenia,20 and van't Wout et al.21 reported that male sex was associated with worse recognition of fearful faces in schizophrenia. Quite the contrary, Vaskinn et al.22 failed to find any gender difference on facial emotion perception tests, but they pointed out that male patients performed significantly worse than their female counterparts on the auditory emotion perception test. In their meta-analytic review on facial emotion perception in schizophrenia, Kohler et al.23 stated that gender-related finding was isolated to controls, and the effect of illness in patients superseded any gender related differences for facial emotion perception.

The aim of this study is to investigate gender differences for facial emotion identification and discrimination abilities in patients with schizophrenia. We hypothesized that female patients would have superiority over male patients for both facial emotion identification and discrimination abilities. As the recognition of negative emotions is known to be impaired in schizophrenia,12,24 and as a female advantage in identifying negative facial emotions have been reported in healthy people;18 we also hypothesized that the female advantage for identifying negative facial emotions would be preserved in schizophrenia.

METHODS

Subjects

35 female schizophrenia outpatients, 35 male schizophrenia outpatients, 35 healthy female controls, and 35 healthy male controls were included in the study. Patients were recruited from the outpatient clinic of psychosis, Izmir Ataturk Education and Research Hospital, Department of Psychiatry. Controls were recruited from the hospital cleaning staff.

Patients were diagnosed using Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I).25,26 Patients who had current co-morbid psychiatric diagnosis were not included in the study. All patients were stable and on atypical antipsychotic medications. Patients' psychopathological symptoms were rated by means of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).27,28 Healthy controls were screened with SCID-I and those who met criteria for any psychiatric disorder were excluded. Furthermore, controls were excluded if they had positive family history for psychosis.

Exclusion criteria for all subjects included mental retardation, identifiable neurological disorder or significant medical illness, substance use in the past six months, visual impairment, age less than 18 years and more than 65 years. All subjects were required to be literate. Information about these criteria was derived from direct interviews with subjects. After description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects.

51 female patients were evaluated for the study, and 16 patients who did not meet inclusion criteria were excluded. 8 had depressive disorder, 3 had obsessive compulsive disorder, 2 had neurological disorder, 1 had substance abuse, 1 had visual impairment, 1 was not literate and they were excluded from the study. 52 male patients were evaluated for the study, and 17 of them were excluded. 8 had substance abuse, 6 had depressive disorder, 1 had hepatic failure, 1 had obsessive compulsive disorder, 1 refused to give informed consent and they were excluded from the study. 42 female controls were evaluated for the study, and 7 who did not meet inclusion criteria were excluded. 3 had depressive disorder, 2 had panic disorder, 2 had positive family history for psychosis. 40 male controls were evaluated. 2 had neurological disorder, 2 had alcohol dependency, 1 had positive family history for psychosis and they were excluded from the study.

All the subjects were tested with Facial Emotion Identification and Facial Emotion Discrimination Tests developed by Kerr and Neale,29 and validated for Turkish culture.30 The Benton Facial Recognition Test was administered to assess general face processing as a control task.31,32

Study instruments

Facial Emotion Identification Test (FEIT) involves black-and-white photographs of 19 different individuals' faces each depicting one of six different emotions (happiness, sadness, anger, surprise, fear, shame), shown one at a time for 15 seconds, with 10 seconds of blank screen between each stimulus presentation. 15 photographs depict negative emotions (sadness, anger, fear, and shame), while 4 photographs depict positive emotions (happiness, and surprise). In the administration of FEIT for this study, each participant was presented with these photographs of facial emotions on a laptop computer screen. The participant was provided with an answer form with 19 items, each with six choices of emotions. After each stimulus, the participant was required to select which of the six emotions was depicted on the picture and to mark it on the form. The total test score was computed as the number of correct answers (0-19). The test score for positive emotions was computed as the number of correct answers for positive emotions (0-4), and the test score for negative emotions was computed as the number of correct answers for negative emotions (0-15).

Facial Emotion Discrimination Test (FEDT) consists of 30 pairs of black-and-white photographs, each pair showing two different people displaying one or two of the six emotions depicted in the FEIT. The pairs are presented simultaneously for 15 seconds, with 10 seconds of blank screen between each presentation. The task is to judge whether the two people in each pair have the same or different emotions. In the administration of FEDT for this study, each participant was presented with these photographs in the same set up as the FEIT. The participant was provided with an answer form with 30 items, each with two choices: "same", "different". After each stimulus, the participant was required to mark his/her response on the answer form. The score was computed as the number of correct answers (0-30).

The Benton Facial Recognition Test (BFRT) is a commonly used test to assess face identity recognition. Participants were presented with a target face situated above six test faces, and were asked to indicate which of the test faces matches the target face. Changes in head orientation and lighting occur between the target and the display of six faces across the test. The score was the number of correct answers out of 54 items.

Statistical analysis

Independent samples t test was used to compare male and female patients for the PANSS scores, along with age, education level, duration of illness, number of hospitalizations, age at the onset of illness, and age at the onset of treatment. Age, education level, BFRT, FEIT, and FEDT scores of male patients, female patients, male controls, and female controls were compared via one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey HSD was applied in the post-hoc analysis for the multiple comparisons of the four groups. Pearson's correlation analysis was used to determine the correlations between FEIT and FEDT scores and duration of illness, number of hospitalizations, age at the onset of illness, age at the onset of treatment, BFRT and PANSS scores.

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of Izmir Ataturk Education and Research Hospital.

RESULTS

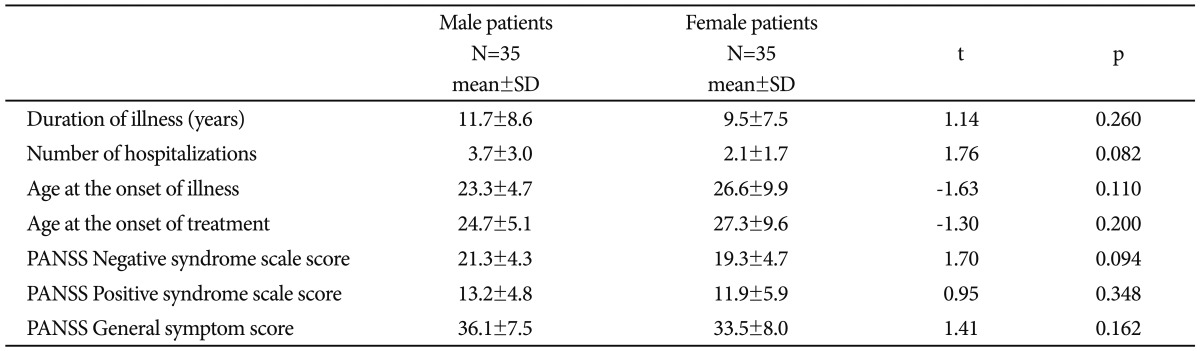

Male and female patients were comparable for duration of illness, number of hospitalizations, age at the onset of illness, age at the onset of treatment, and for PANSS scores (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical characteristics of male and female patients

PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

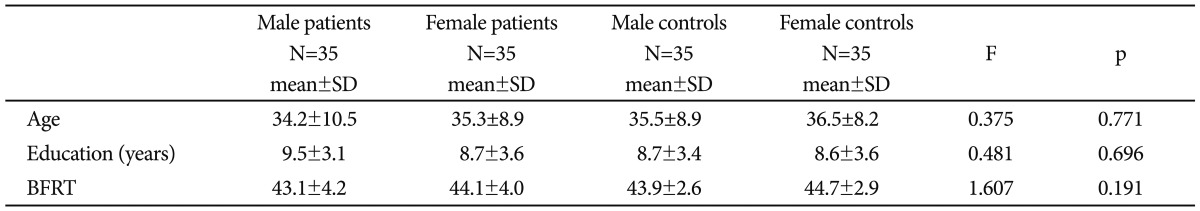

Male patients, female patients, male controls, and female controls were compared for age, education level, and BFRT scores by one way ANOVA. The four groups did not differ significantly for age, education level, and BFRT scores (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of age, education level and BFRT scores of male and female patients, and male and female controls

BFRT: Benton Facial Recognition Test

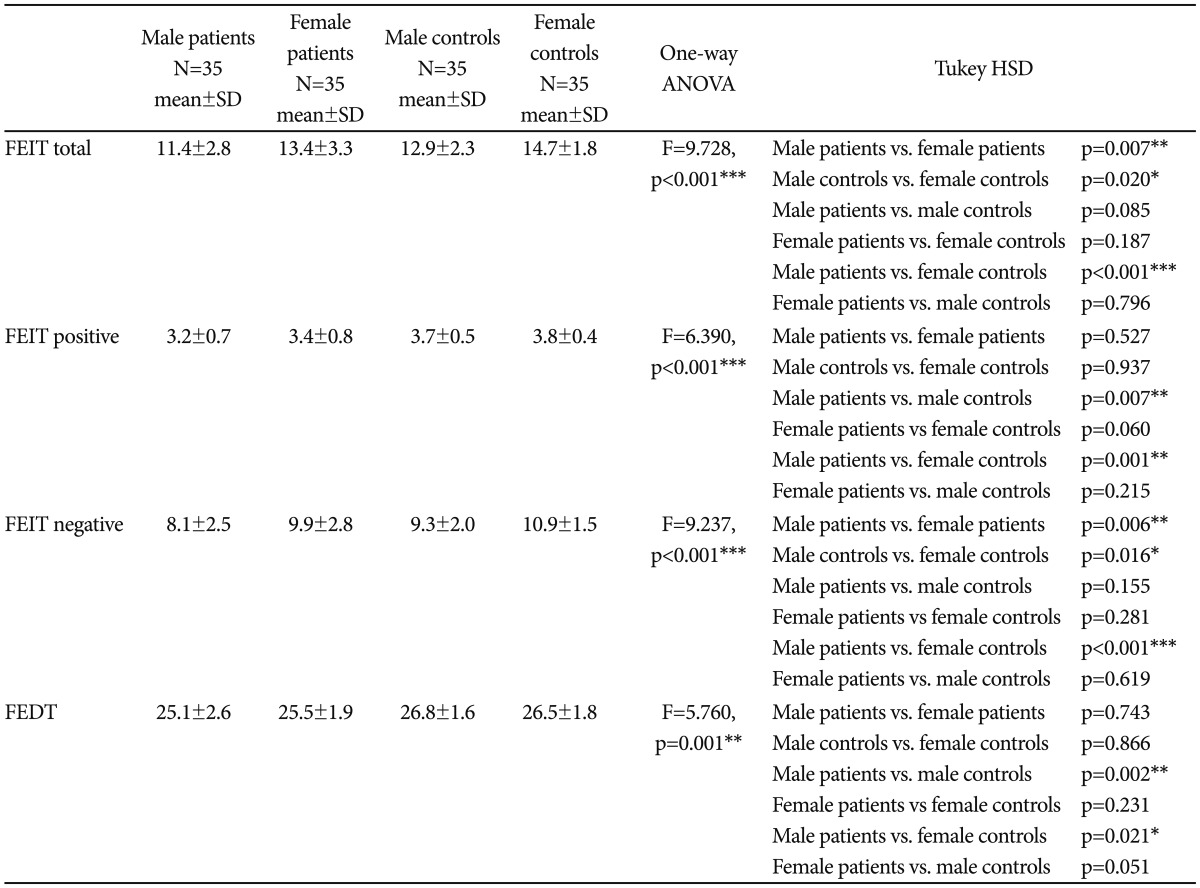

One way ANOVA was used to compare the four groups for FEIT and FEDT scores. There were statistically significant differences between groups on FEIT total score, positive score, negative score, and on FEDT score (F=9.728, df=3, 136, p<0.001; F=6.390, df=3, 136, p<0.001; F=9.237, df=3, 136, p<0.001; F=5.760, df=3, 136, p=0.001 respectively).

Tukey HSD was applied in the post-hoc analysis. Male patients performed significantly worse than male controls on FEIT positive score, and FEDT score, whereas they performed significantly worse than female controls on FEIT total, positive, and negative scores, and on FEDT score. Male patients performed worse than female patients on FEIT total, and negative scores. On all tasks, female patients performed comparable with both female and male controls. Male controls performed significantly worse than female controls on FEIT total and negative scores. Table 3 depicts comparison of the FEIT and FEDT scores of male and female patients, along with male and female controls.

Table 3.

Comparison of FEIT and FEDT scores of male and female patients, and male and female controls

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. FEIT: Facial Emotion Identification Test, FEDT: Facial Emotion Discrimination Test, ANOVA: analysis of variance, HSD: Honestly Significant Difference

Correlation coefficients were calculated for each participant group separately. There were no significant correlations between BFRT scores and FEIT or FEDT scores for any of the groups. There were no significant correlations between duration of illness, number of hospitalizations, age at the onset of illness, age at the onset of treatment, PANSS scores and FEIT or FEDT scores for neither male nor female patient groups. When male and female patient groups were pooled together; PANSS negative syndrome scale score had significant but weak inverse correlations with FEIT total score, positive score, negative score, and FEDT score (r=-0.34, p=0.004; r=-0.33, p=0.006; r=-0.29, p=0.014; r=-0.30, p=0.012 respectively).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies that investigated emotion recognition in schizophrenia reported impairments on both facial emotion identification,5,7,8 and discrimination6,8 abilities. In addition, they frequently mentioned negative emotion processing deficits.5,7,12,24 Quite differently, our study found out facial emotion identification and discrimination deficits in male -but not in female- patients with schizophrenia. When we examined negative and positive emotions separately, we realized that male patients were significantly worse than male controls in the identification of positive emotions and they were significantly worse than female controls in the identification of both positive and negative emotions. Strikingly, we failed to find any difference between female patients and male or female controls on facial emotion identification and discrimination tasks, and on the identification of positive and negative emotions.

Previous studies on facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia have usually compared mixed groups containing both male and female participants. In contrast, our study investigated different gender groups separately. In the light of our findings, it could be assumed that, male patients themselves could be responsible for the difference between schizophrenia patients and healthy controls reported by previous studies. In our sample female patients did not have any impairment on any of the tasks and this is in line with Scholten et al.'s findings20 who also reported that female patients with schizophrenia performed as well as female and male controls on a facial affect processing task.

Consistent with previous research,14-18 findings indicating a female advantage in the recognition of facial emotions in healthy people have been replicated in our sample. Male controls performed significantly worse than female controls on facial emotion identification test, and their performance was particularly worse in the identification of negative emotions.

Our primary purpose was to examine gender differences in facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia. As we have hypothesized, in our study, schizophrenic women outperformed schizophrenic men in the ability to identify facial emotions. Moreover, just like the healthy controls, women with schizophrenia outperformed men especially in the identification of negative emotions. The female advantage in identifying negative facial emotions has been mentioned before both for healthy people,18 and for patients with schizophrenia.20,21 Our findings bring more evidence for the hypothesis that the female advantage in identifying negative facial emotions has been preserved in schizophrenia.

Interestingly, we failed to find any gender differences for facial emotion discrimination ability in neither patients nor controls. Discrimination and identification of facial emotions may be different abilities. While discrimination of emotions (matching) requires automatic and intuitive processing, identification of emotions (labeling) engages cognitive processes such as judgment and interpretation.33,34 Whereas automatic intuitive processing of facial emotions has been shown to depend primarily on right hemispheric resources,35 the labeling of facial emotions has been shown to depend on the left hemisphere.36 In addition, some studies suggest that men rely more on right hemisphere than women do during emotion processing.37,38 Perhaps this may explain in part why men were more successful in the facial emotion discrimination task which requires more right hemispheric resources that they rely more on.

In this study, male and female patients with schizophrenia were not only comparable for age and education, but they were also comparable for duration of illness, number of hospitalizations, age at the onset of illness, age at the onset of treatment, and PANSS scores. This is an advantage of our study, as patient characteristics and symptomatology are well known factors that influence facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia.7,39,40 These factors may have accounted for the diversity of the findings of previous studies that examined the impact of gender on facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia. We used BFRT as a control task to differentiate facial emotion processing deficits from general face processing deficits, and this is another advantage. Another advantage is that our study evaluated both facial emotion identification and discrimination abilities. On the other hand, the limitation of our study is that the facial emotion recognition tasks we used consisted of posed facial expressions instead of genuine ones, unlike real life situations.

In conclusion, women with schizophrenia outperformed men for facial emotion recognition abilities in a pattern that is just similar with the healthy controls. Findings of neuroimaging studies point out differences between healthy males and females in brain activity during facial affect processing.37 It can be hypothesized that male and female patients with schizophrenia have different neural dynamics during facial emotion processing and this is probably in a pattern that mimic healthy controls. However, new research is required to test this hypothesis. By the way, it could be claimed that male patients with schizophrenia need special consideration and special treatment techniques for emotion perception deficits. As emotion perception deficits are well known risk factors that influence social functioning,9-13 this may also improve poor social functioning that male patients are more likely to suffer from.

References

- 1.Erol A. Female reproductive life and schizophrenia. J Psychiatry Psychol Psychopharmacol. 2005;13(Suppl 1):41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorup A, Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Ohlenschlaeger J, Christensen T, Krarup G, et al. Gender differences in young adults with first-episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders at baseline in the Danish OPUS study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:396–405. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253784.59708.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Usall J, Haro JM, Ochoa S, Marquez M, Araya S Needs of Patients with Schizophrenia group. Influence of gender on social outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:337–342. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heimberg C, Gur RE, Erwin RJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RC. Facial emotion discrimination: III. Behavioral findings in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1992;42:253–265. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90117-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohler CG, Turner TH, Bilker WB, Brensinger CM, Siegel SJ, Kanes SJ, et al. Facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: intensity effects and error pattern. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1768–1774. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider F, Gur RC, Koch K, Backes V, Amunts K, Shah NJ, et al. Impairment in the specificity of emotion processing in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:442–447. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van 't Wout M, Aleman A, Kessels RP, Cahn W, de Haan EH, Kahn RS. Exploring the nature of facial affect processing deficits in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;150:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erol A, Mete L, Sonmez I, Unal EK. Facial emotion recognition in patients with schizophrenia and their siblings. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64:63–67. doi: 10.3109/08039480903511399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poole JH, Tobias FC, Vinogradov S. The functional relevance of affect recognition errors in schizophrenia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2000;6:649–658. doi: 10.1017/s135561770066602x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooker C, Park S. Emotion processing and its relationship to social functioning in schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Res. 2002;112:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kee KS, Green MF, Mintz J, Brekke JS. Is emotion processing a predictor of functional outcome in schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:487–497. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hofer A, Benecke C, Edlinger M, Huber R, Kemmler G, Rettenbacher MA, et al. Facial emotion recognition and its relationship to symptomatic, subjective, and functional outcomes in outpatients with chronic schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erol A, Keleş Unal E, Tunç Aydin E, Mete L. Predictors of social functioning in schizophrenia. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2009;20:313–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alaerts K, Nackaerts E, Meyns P, Swinnen SP, Wenderoth N. Action and emotion recognition from point light displays: an investigation of gender differences. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann H, Kessler H, Eppel T, Rukavina S, Traue HC. Expression intensity, gender and facial emotion recognition: Women recognize only subtle facial emotions better than men. Acta Psychol (Amst) 2010;135:278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams LM, Mathersul D, Palmer DM, Gur RC, Gur RE, Gordon E. Explicit identification and implicit recognition of facial emotions: I. Age effects in males and females across 10 decades. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2009;31:257–277. doi: 10.1080/13803390802255635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall JA, Matsumoto D. Gender differences in judgments of multiple emotions from facial expressions. Emotion. 2004;4:201–206. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.4.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClure EB. A meta-analytic review of sex differences in facial expression processing and their development in infants, children, and adolescents. Psychol Bull. 2000;126:424–453. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vassallo S, Cooper SL, Douglas JM. Visual scanning in the recognition of facial affect: Is there an observer sex difference? J Vis. 2009;9:11. doi: 10.1167/9.3.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scholten MR, Aleman A, Montagne B, Kahn RS. Schizophrenia and processing of facial emoions: sex matters. Schizophr Res. 2005;78:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van't Wout M, van Dijke A, Aleman A, Kessels RP, Pijpers W, Kahn RS. Fearful faces in schizophrenia: the relationship between patient characteristics and facial affect recognition. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:758–764. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318142cc31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaskinn A, Sundet K, Friis S, Simonsen C, Birkenaes AB, Engh JA, et al. The effect of gender on emotion perception in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohler CG, Walker JB, Martin EA, Healey KM, Moberg PJ. Facial emotion perception in schizoprenia: A meta-analytic review. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:1009–1019. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandal MK, Pandey R, Prasad AB. Facial expressions of emotions and schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:399–412. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Clinical Version (SCID-I/CV) Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozkurkcugil A, Aydemir O, Yıldız M, Esen A, Koroglu E. The adaptation and reliability study of Turkish version of Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Clinical Version. Turk J Drugs ther. 1999;12:233–236. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kostakoglu E, Batur S, Tiryaki A, Göğüş A. Pozitif ve Negatif Sendrom Ölçeğinin Türkçe uyarlamasının geçerlilik ve güvenilirliği. Türk Psikoloji Dergisi. 1999;14:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerr SL, Neale JM. Emotion perception in schizophrenia: specific deficit or further evidence of generalized poor performance? J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102:312–318. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erol A, Unal Keleş E, Gulpek D, Mete L. The reliability and validity of facial emotion identification and facial emotion discrimination tests in Turkish culture. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg. 2009;10:116–123. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benton AL, Sivan AB, Hamsher KS, Varney NR, Spreen O. Benton's Test of Facial Recognition. New York: Oxford University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keskinkılıç C. Benton Yüz Tanıma Testi'nin Türkiye toplumu normal yetişkin denekler üzerindeki standardizasyonu. Turk Noroloji Dergisi. 2008;14:179–191. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tessitore A, Hariri AR, Fera F, Smith WG, Das S, Weinberger DR, et al. Functional changes in the activity of brain regions underlying emotion processing in the elderly. Psychiatry Res. 2005;139:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang AT, Dapretto M, Hariri AR, Sigman M, Bookheimer SY. Neural correlates of facial affect processing in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:481–490. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hartikainen KM, Ogawa KH, Knight RT. Transient interference of right hemispheric function due to automatic emotional processing. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38:1576–1580. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stone VE, Nisenson L, Eliassen JC, Gazzaniga MS. Left hemisphere representations of emotional facial expressions. Neuropsychologia. 1996;34:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(95)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee TM, Liu H, Hoosain R, Liao WT, Wu CT, Yuen KS, et al. Gender differences in neural correlates of recognition of happy and sad faces in humans assessed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosci Lett. 2002;333:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00965-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Everhart DE, Shucard JL, Quatrin T, Shucard DW. Sex-related differences in event-related potentials, face recognition, and facial affect processing in prepubertal children. Neuropsychology. 2001;15:329–341. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.15.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kohler CG, Bilker W, Hagendoorn M, Gur RE, Gur RC. Emotion recognition deficit in schizophrenia: association with symptomatology and cognition. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:127–136. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00847-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Penn DL, Combs DR, Ritchie M, Francis J, Cassisi J, Morris S, et al. Emotion recognition in schizophrenia: further investigation of generalized versus specific deficit models. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:512–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]