Abstract

Background:

Physical activity may decrease renal cancer risk by reducing obesity, blood pressure, insulin resistance, and lipid peroxidation. Despite plausible biologic mechanisms linking increased physical activity to decreased risk for renal cancer, few epidemiologic studies have been able to report a clear inverse association between physical activity and renal cancer, and no meta-analysis is available on the topic.

Methods:

We searched the literature using PubMed and Web of Knowledge to identify published non-ecologic epidemiologic studies quantifying the relationship between physical activity and renal cancer risk in individuals without a cancer history. Following the PRISMA guidelines, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, including information from 19 studies based on a total of 2 327 322 subjects and 10 756 cases. The methodologic quality of the studies was examined using a comprehensive scoring system.

Results:

Comparing high vs low levels of physical activity, we observed an inverse association between physical activity and renal cancer risk (summary relative risk (RR) from random-effects meta-analysis=0.88; 95% confidence interval (CI)=0.79–0.97). Summarising risk estimates from high-quality studies strengthened the inverse association between physical activity and renal cancer risk (RR=0.78; 95% CI=0.66–0.92). Effect modification by adiposity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, smoking, gender, or geographic region was not observed.

Conclusion:

Our comprehensive meta-analysis provides strong support for an inverse relation of physical activity to renal cancer risk. Future high-quality studies are required to discern which specific types, intensities, frequencies, and durations of physical activity are needed for renal cancer risk reduction.

Keywords: physical activity, renal cancer, meta-analysis

Renal cancer is one of the top 10 cancer sites in the United States and Europe. Each year, about 65 000 new cases are diagnosed in the United States (Howlader et al, 2012) and about 60 000 new cases are diagnosed in the European Union (Boyle and Ferlay, 2005). Well-established unfavourable risk factors for renal cancer include smoking, obesity, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Scelo and Brennan, 2007). In contrast, physical activity may prevent the development of renal cancer, partly because it helps reduce obesity (Wing, 1999), blood pressure (Blair et al, 1984), and insulin resistance (Rosenthal et al, 1983). Physical activity may also independently decrease renal cancer risk by lowering lipid peroxidation levels (Vincent et al, 2002). However, few available epidemiologic studies have been able to report a clear inverse association between physical activity and renal cancer (Leitzmann, 2011). Moreover, no meta-analysis is available on the relation between physical activity and renal cancer. To address this research gap, we conducted a systematic literature search and meta-analysis to quantify the association between physical activity and renal cancer, taking into account the methodologic quality of the studies.

Materials and methods

Literature search

Our systematic review and meta-analysis adhered to the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al, 2009). Both authors searched the literature using PubMed (see Appendix B for PubMed search options) and Web of Knowledge (see Appendix C for Web of Knowledge search options) to identify published non-ecologic epidemiologic studies quantifying the relationship between physical activity and renal cancer risk in individuals without a cancer history. That search was complemented by a scan of the reference lists of the identified studies and a scan of the reference list of a previous systematic review (Leitzmann, 2011). We considered all human research articles published in English through the end of September 2012 not classified as review, meta-analysis, editorial, comment, letter, practice guideline, or news. Our search strategy included the terms physical activity, exercise, cardiorespiratory fitness, cardiovascular fitness, resistance training, endurance training, aerobic, sport, athletes, players, lifestyle, kidney cancer, renal cancer, renal cell cancer, renal carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, cancer, risk, incidence, and mortality. The search strategy excluded research on cancer survivors and research on specific types of cancer other than renal cancer. That search yielded 586 potential articles. Irrelevant articles were eliminated after screening titles and abstracts (n=477) or manuscripts (n=82). The 27 remaining studies (Goodman et al, 1986; Paffenbarger et al, 1987; Brownson et al, 1991; Lindblad et al, 1994; Mellemgaard et al, 1994, 1995; Bergstrom et al, 1999, 2001; Parker et al, 2002; Menezes et al, 2003; Mahabir et al, 2004; Nicodemus et al, 2004; van Dijk et al, 2004; Washio et al, 2005; Chiu et al, 2006; Pan et al, 2006; Setiawan et al, 2007; Tavani et al, 2007; Hu et al, 2008, 2009; Moore et al, 2008; Thompson et al, 2008; Yun et al, 2008; Spyridopoulos et al, 2009; Wilson et al, 2009; George et al, 2011; Parent et al, 2011) proved to be relevant.

To avoid duplicate information from overlapping studies, we removed eight of the 27 identified studies because their results were pooled (Lindblad et al, 1994; Mellemgaard et al, 1994) or updated (Parker et al, 2002; Menezes et al, 2003; Pan et al, 2006) in studies (Mellemgaard et al, 1995; Chiu et al, 2006; Hu et al, 2008) using the same database, because they reported results (Hu et al, 2009; Wilson et al, 2009) presented earlier (Mahabir et al, 2004; Hu et al, 2008), or because their investigations of total sitting time (George et al, 2011) were closely related to a previous study (Moore et al, 2008) on physical activity from the same cohort. The remaining 19 studies (Goodman et al, 1986; Paffenbarger et al, 1987; Brownson et al, 1991; Mellemgaard et al, 1995; Bergstrom et al, 1999, 2001; Mahabir et al, 2004; Nicodemus et al, 2004; van Dijk et al, 2004; Washio et al, 2005; Chiu et al, 2006; Setiawan et al, 2007; Tavani et al, 2007; Hu et al, 2008; Moore et al, 2008; Thompson et al, 2008; Yun et al, 2008; Spyridopoulos et al, 2009; Parent et al, 2011) were included in the meta-analysis.

Quality score

The magnitude and heterogeneity of risk estimates may depend on the methodologic quality associated with the underlying study and with the risk estimate derivation. Similar to three previous systematic reviews (Monninkhof et al, 2007; Voskuil et al, 2007; Liu et al, 2011) on the association between physical activity and specific types of cancer, both authors employed a quality score proposed by Voskuil et al (2007) to assess the methodologic quality of the studies and the consistency of the available evidence. Please refer to Appendix A for a description of the items covered by the quality score.

Main statistical analysis

Because some studies presented risk estimates for men and women and some studies investigated more than one physical activity domain, the 19 identified studies reported a total of 37 risk estimates. If separate risk estimates were available for men and women, both risk estimates were included in the meta-analysis because they were based on independent samples. To prevent potential bias arising from the fact that the risk estimates for the various physical activity domains were based on the same study population, both authors allowed only one estimate per study and gender in the main analysis. Specifically, if more than one physical activity domain was studied, we selected the risk estimate with the highest quality score in the main analysis. Of the 37 risk estimates, 25 were included in the main analysis.

In the meta-analysis, we interpreted odds ratios and hazard ratios as relative risk estimates (RRi), computed the natural logarithms of those risk estimates log(RRi) with corresponding standard errors si=(log(upper 95% confidence interval (CI) bound of RR)−log(RR))/1.96, and employed a random-effects model to determine the weighted average of those log(RRi)s while allowing for heterogeneity of effects. In the random-effects model, the log(RRi)s were weighted by wi=1/(si2+t2) where si represented the standard error of log(RRi) and t2 represented the restricted maximum-likelihood estimate of the overall variance (Higgins and Thompson, 2002). In one case (Paffenbarger et al, 1987), we derived the standard error of the log(RRi) using the P-value accompanying the RR estimate. In five additional cases (Brownson et al, 1991; Mellemgaard et al, 1995; Bergstrom et al, 1999, 2001; Chiu et al, 2006), the reported RRs used the highest rather than the lowest activity level as the reference category, so we reversed those RRs for comparability. Heterogeneity of the risk estimates was assessed using the Q- and I2-statistics (Higgins and Thompson, 2002). Publication bias was tested using funnel plots (Egger et al, 1997), Egger's regression test (Egger et al, 1997), and Begg's rank correlation test (Begg and Mazumdar, 1994).

Statistical subanalyses

If a study presented separate risk estimates for recreational, occupational, and total physical activity, in a subanalysis all those risk estimates were included in the meta-analysis. Also, in a subanalysis we used all 37 risk estimates to investigate the impact of prespecified potentially influential methodologic factors on the summary risk estimate.

On the basis of pre-existing evidence, we hypothesised that the relations of physical activity to renal cell cancer would differ according to study design (cohort or case–control), physical activity domain (recreational, occupational, or total physical activity), and gender (men, women, or men and women combined). Thus, we conducted subanalyses within categories of those variables. We also performed exploratory analyses that were stratified by geographic region (North America, Europe, Asia), type of physical activity assessment (energy expenditure, physical fitness, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity duration, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity frequency, and qualitative assessments using categories, such as ‘sedentary', ‘light', ‘moderate', or ‘high' physical activity), timing in life of physical activity (recent physical activity, past physical activity, or consistent physical activity over time), number of adjustment factors (in quartiles), adjustments for smoking and obesity (adjusted for smoking and obesity, adjusted for smoking but not obesity, adjusted neither for smoking nor obesity; the option of adjusting for obesity but not smoking was not included because it did not occur), adjustment for hypertension (yes, no), adjustment for type 2 diabetes mellitus (yes, no), or methodologic quality score (in tertiles). To assess the influence of those factors, we applied random-effects meta-analysis regression comparing the model including the current factor of interest as a single explanatory variable with the null model not including any explanatory variables.

All statistical analyses were performed in R (R Development Core Team, 2011) using the R-package ‘metafor' (Viechtbauer, 2010). Risk estimates are reported with 95% CIs. Statistical significance is based on the 5% significance level.

Results

Description of underlying study characteristics

Table 1 presents the 19 studies on physical activity and renal cancer risk included in the meta-analysis. Because six studies stratified results by gender and nine studies investigated more than one physical activity domain, the 19 studies reported a total of 37 risk estimates.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 19 studies on physical activity and renal cancer risk included in the meta-analysis.

| Authors, year, gender | Subjects | Cases | Region | Adjustment factors (excluding age, sex) | PA domain | Timing in life of PA | Relative risk (95% CI), high vs low PA | Low PA defined by | High PA defined by | Quality score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Case–control studies | ||||||||||

| Brownson et al (1991) | ||||||||||

| Men |

17 147 |

449 |

North America |

Smoking |

Occupational |

Recent PA |

0.77 (0.50, 1.11) |

Low PA |

High PA |

45 |

| Chiu et al (2006) | ||||||||||

| Men | 1660 | 225 | North America | History of hypertension (yes/no), family history of renal cancer, marital status, red meat intake, proxy, SES (education), smoking, total energy intake, vegetable intake | Recreational | Consistent PA over time | 0.83 (0.48, 1.43) | MVPA (10 min) less than once per month | MVPA (10 min) every day | 76 |

| Women |

829 |

123 |

|

|

Recreational |

Consistent PA over time |

0.40 (0.19, 0.83) |

MVPA (10 min) less than once per month |

MVPA (10 min) every day |

76 |

| Goodman et al (1986) | ||||||||||

| Men | 378 | 189 | North America | — | Recreational | Consistent PA over time | 1.14 (0.65, 2.05) | None/occasional PA | Strenuous PA | 66 |

| Occupational | Consistent PA over time | 0.88 (0.48, 1.55) | None/occasional PA | Strenuous PA | 62 | |||||

| Women | 156 | 78 | Recreational | Consistent PA over time | 1.11 (0.44, 2.97) | None/occasional PA | Strenuous PA | 66 | ||

| |

|

|

|

|

Occupational |

Consistent PA over time |

1.20 (0.41, 4.06) |

None/occasional PA |

Strenuous PA |

62 |

| Hu et al (2008) | ||||||||||

| Men and women |

6177 |

1138 |

North America |

Residential area |

Recreational |

Recent PA |

0.90 (0.71, 1.14) |

No PA |

55 min or more of MVPA per week |

60 |

| Mellemgaard et al (1995) | ||||||||||

| Men | 1994 | 864 | Europe | Obesity (BMI), smoking, study centre | Recreational | Past PA | 1.11 (0.56, 2.50) | Not physically active | Very active | 62 |

| Occupational | Past PA | 1.11 (0.71, 1.67) | Not physically active | Very active | 58 | |||||

| Women | 1308 | 572 | Recreational | Past PA | 1.67 (0.71, 3.33) | Not physically active | Very active | 62 | ||

| |

|

|

|

|

Occupational |

Past PA |

1.67 (0.91, 3.33) |

Not physically active |

Very active |

58 |

| Parent et al (2011) | ||||||||||

| Men | 533 | 177 | North America | Alcohol intake, coffee intake, obesity (BMI), proxy, race/ethnicity, recreational/occupational activity (mutual adjustment), SES (socio-economic status, education), smoking | Total | Consistent PA over time | 1.02 (0.70, 1.49) | Less than 1.5 MET at work independent of leisure time PA or 1.5–3.9 MET at work and less than once per week engaged in leisure time MVPA | Energy expenditure of 4 MET per day or more at work independent of leisure time PA or 1.6–3.9 MET per day at work and at least once per week engaged in leisure time MVPA | 68 |

| Recreational | Past PA | 1.11 (0.76, 1.64) | MVPA less than once per week | MVPA at least once per week | 69 | |||||

| |

|

|

|

|

Occupational |

Consistent PA over time |

0.84 (0.38, 1.89) |

1.5 MET or less of energy expenditure |

Energy expenditure of 4 MET or more per day |

64 |

| Spyridopoulos et al (2009) | ||||||||||

| Men and women |

350 |

70 |

Europe |

Alcohol intake, coffee intake, history of diabetes (yes/no), obesity (serum adiponectin, serum leptin, waist–hip ratio), protein intake, SES (education), smoking, vegetarian diet |

Recreational |

Recent PA |

0.62 (0.48, 0.82) |

— |

Increment of 3.5 h of MVPA per week |

78 |

| Tavani et al, 2007 | ||||||||||

| Men and women | 2301 | 767 | Europe | Calendar year of interview, history of hypertension (yes/no), obesity (BMI), smoking, study centre | Recreational | Past PA | 1.03 (0.78, 1.36) | Less than 2 h of MVPA per week | More than 7 h of MVPA per week | 66 |

| |

|

|

|

|

Occupational |

Past PA |

0.71 (0.55, 0.92) |

Low PA |

High PA |

55 |

|

Cohort studies | ||||||||||

| Bergstrom et al, 1999 | ||||||||||

| Men | 674 025 | 2704 | Europe | Calendar year of follow-up, residential area, SES (job title) | Occupational | Past PA | 0.80 (0.65, 0.98) | Sedentary activities | High PA | 58 |

| Women |

253 336 |

587 |

|

|

Occupational |

Past PA |

1.25 (0.79, 1.96) |

Sedentary activities |

High PA |

58 |

| Bergstrom et al, 2001 | ||||||||||

| Men and women | 17 241 | 102 | Europe | History of hypertension (yes/no), obesity (BMI), smoking | Recreational | Consistent PA over time | 1.67 (0.83, 3.33) | Sedentary activities | Strenuous PA | 83 |

| |

|

|

|

|

Occupational |

Consistent PA over time |

1.25 (0.63, 2.50) |

Sedentary activities |

Strenuous PA |

71 |

| Mahabir et al (2004) | ||||||||||

| Men | 29 133 | 210 | Europe | Alcohol intake, dietary fat intake, fruit and vegetable intake, history of hypertension (blood pressure), intervention group, recreational/occupational activity (mutual adjustment), obesity (BMI), residential area, serum cholesterol, SES (education), smoking, total energy intake | Recreational | Recent PA | 0.46 (0.18, 1.13) | Light PA | Heavy PA | 75 |

| |

|

|

|

|

Occupational |

Recent PA |

1.08 (0.54, 2.15) |

Sedentary activities |

Heavy PA |

63 |

| Moore et al (2008) | ||||||||||

| Men and women | 482 386 | 1238 | North America | Body height, history of diabetes (yes/no), history of hypertension (yes/no), obesity (BMI), protein intake, race/ethnicity, smoking. | Recreational | Recent PA | 0.77 (0.64, 0.92) | Never/rarely engaging in VPA | Five times per week or more engaged in VPA (more than 20 min) | 76 |

| |

|

|

|

|

Occupational |

Recent PA |

0.84 (0.57, 1.22) |

Mostly sitting |

Heavy PA |

65 |

| Nicodemus et al (2004) | ||||||||||

| Women |

34 637 |

124 |

North America |

— |

Recreational |

Recent PA |

0.37 (0.14, 0.99) |

Low VPA frequency |

High VPA frequency |

71 |

| Paffenbarger et al (1987) | ||||||||||

| Men and women |

56 683 |

53 |

North America |

Birth year |

Recreational |

Past PA |

0.95 (0.47, 1.94) |

Less than 5 h of VPA per week |

5 h of VPA per week or more |

61 |

| Setiawan et al (2007) | ||||||||||

| Men | 75 162 | 220 | North America | Alcohol intake, history of hypertension (yes/no), obesity (BMI), smoking | Total | Recent PA | 1.09 (0.75, 1.58) | 1.4 MET per day or less | Energy expenditure of 1.8 MET per day or more | 77 |

| Women |

85 964 |

127 |

|

|

Total |

Recent PA |

0.66 (0.40, 1.10) |

1.4 MET per day or less |

Energy expenditure of 1.8 MET per day or more |

77 |

| Thompson et al (2008) | ||||||||||

| Men |

21 663 |

31 |

North America |

Alcohol intake, examination year, history of cancer, history of diabetes (fasting glucose level), obesity (BMI), smoking |

Total |

Recent PA |

0.91 (0.45, 2.68) |

Lowest physical fitness quintile |

Upper two physical fitness quintiles |

69 |

| van Dijk et al (2004) | ||||||||||

| Men | 2335 | 179 | Europe | Obesity (BMI), smoking, total energy intake | Recreational | Recent PA | 0.74 (0.44, 1.23) | Less than 30 min of MVPA per day | More than 10.5 h of MVPA per week | 77 |

| Occupational | Consistent PA over time | 0.82 (0.46, 1.47) | Energy expenditure of <8 kJ min−1 | Energy expenditure of >12 kJ min−1 | 76 | |||||

| Women |

2444 |

96 |

|

|

Recreational |

Recent PA |

1.13 (0.56, 2.29) |

Less than 30 min of MVPA per day |

More than 10.5 h of MVPA per week |

77 |

| Washio et al (2005) | ||||||||||

| Men and women | 114 517 | 38 | Asia | — | Recreational | Recent PA | 0.54 (0.25, 1.18) | MVPA less than once per week | MVPA once per week or more | 58 |

| |

|

|

|

|

Occupational |

Recent PA |

1.44 (0.72, 2.88) |

Sedentary activities |

Physically active |

51 |

| Yun et al (2008) | ||||||||||

| Men | 444 963 | 395 | Asia | Alcohol intake, dietary pattern, history of diabetes (fasting glucose level), obesity (BMI), SES (employment), smoking | Recreational | Recent PA | 1.01 (0.83, 1.23) | Combination of MVPA frequency and duration: MVPA less than 4 times per week and less than 30 min per session | Combination of MVPA frequency and duration: MVPA at least five times per week and at least 30 min per session | 71 |

Abbreviations: BMI=body mass index; MET=metabolic equivalent of task; MVPA=moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA=physical activity; RR=relative risk; SES=socioeconomic status; VPA=vigorous physical activity.

The 19 studies are grouped by study design. The main meta-analysis considered just one risk estimate (in bold) per study and gender.

When grouping studies by potentially effect modifying factors (Table 2), we noted that there was an equal number of risk estimates from case–control and prospective cohort studies, with the vast majority of studies originating in the United States or Europe. Half of the risk estimates were based on recreational physical activity, one-third of the risk estimates were based on occupational activity, and four risk estimates were based on total physical activity. Half of the physical activity assessments were of a qualitative type and the remaining half were of a quantitative type. Nearly two-thirds of the risk estimates were adjusted for smoking and obesity, one-third of the risk estimates were adjusted for hypertension, and one-sixth of the risk estimates were adjusted for history of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Table 2. Summary risk estimates and I2 measures of heterogeneity from random-effects models stratified by selected study characteristics.

| Stratification criterion | Number of included RRs | RR (95% CI) (high vs low PA) from random-effects model | I2 (%) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Methodologic qualityb | ||||

| RRs within upper tertile of quality score | 11 | 0.78 (0.66, 0.92) | 33 | |

| RRs within intermediate tertile of quality score | 12 | 1.00 (0.89, 1.13) | 0 | |

| RRs within lower tertile of quality score |

14 |

0.93 (0.80, 1.07) |

30 |

0.02 |

|

PA assessment | ||||

| RRs based on qualitative PA assessments | 18 | 0.98 (0.85, 1.14) | 35 | |

| RRs based on energy expenditure | 6 | 0.97 (0.84, 1.12) | 0 | |

| RRs based on MVPA duration | 6 | 0.85 (0.69, 1.04) | 43 | |

| RRs based on MVPA frequency |

6 |

0.72 (0.53, 0.97) |

53 |

0.24 |

|

PA domain | ||||

| RRs based on total activity | 4 | 0.95 (0.76, 1.20) | 0 | |

| RRs based on occupational activity | 14 | 0.91 (0.79, 1.04) | 21 | |

| RRs based on recreational activity |

19 |

0.88 (0.77, 1.00) |

40 |

0.84 |

|

Timing in life of PA | ||||

| RRs based on recent PA | 16 | 0.83 (0.74, 0.93) | 28 | |

| RRs based on consistent PA over time | 11 | 0.96 (0.79, 1.15) | 0 | |

| RRs based on past PA |

10 |

1.01 (0.84, 1.20) |

46 |

0.18 |

|

Gender | ||||

| RRs among men | 17 | 0.93 (0.84, 1.02) | 2 | |

| RRs among women | 9 | 0.95 (0.66, 1.36) | 57 | |

| RRs among men and women |

11 |

0.85 (0.73, 0.98) |

42 |

0.41 |

|

Study design | ||||

| RRs from case–control studies | 18 | 0.91 (0.79, 1.04) | 36 | |

| RRs from cohort studies |

19 |

0.89 (0.80, 0.99) |

19 |

0.93 |

|

Study region | ||||

| RRs from studies in North America | 18 | 0.85 (0.77, 0.94) | 0 | |

| RRs from studies in Europe | 16 | 0.95 (0.80, 1.12) | 51 | |

| RRs from studies in Asia |

3 |

1.00 (0.83, 1.20) |

0 |

0.63 |

|

Number of adjustment factorsc | ||||

| RRs within upper tertile of number of adjustment factors | 12 | 0.83 (0.71, 0.97) | 40 | |

| RRs within intermediate tertile of number of adjustment factors | 4 | 0.87 (0.68, 1.10) | 52 | |

| RRs within lower tertile of number of adjustment factors |

21 |

0.96 (0.85, 1.08) |

14 |

0.28 |

|

Adjustment for smoking and obesity | ||||

| RRs adjusted for smoking and obesity | 23 | 0.92 (0.82, 1.03) | 37 | |

| RRs adjusted for smoking but not obesity | 3 | 0.71 (0.54, 0.94) | 0 | |

| RRs adjusted neither for smoking nor obesity |

11 |

0.89 (0.78, 1.01) |

2 |

0.31 |

|

Adjustment for hypertension | ||||

| RRs adjusted for hypertension | 12 | 0.85 (0.73, 0.97) | 30 | |

| RRs not adjusted for hypertension |

25 |

0.93 (0.83, 1.03) |

24 |

0.30 |

|

Adjustment for diabetes | ||||

| RRs adjusted for diabetes | 5 | 0.81 (0.66, 0.99) | 57 | |

| RRs not adjusted for diabetes | 32 | 0.92 (0.84, 1.01) | 14 | 0.18 |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; MVPA=moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA=physical activity; RR=relative risk.

P-values for effect heterogeneity across strata were obtained from random-effects meta-regression comparing the model including the stratification variable as a single explanatory variable with the null model not including any explanatory variables.

The quality scores ranged from 45 to 83 percentage points (out of 100 percentage points), with lower and upper tertile cutoffs of 62 percentage points and 71 percentage points, respectively.

The number of adjustment factors (not counting adjustments for age and sex) ranged between 0 and 12, with lower and upper tertile cutoffs of 3 and 5, respectively.

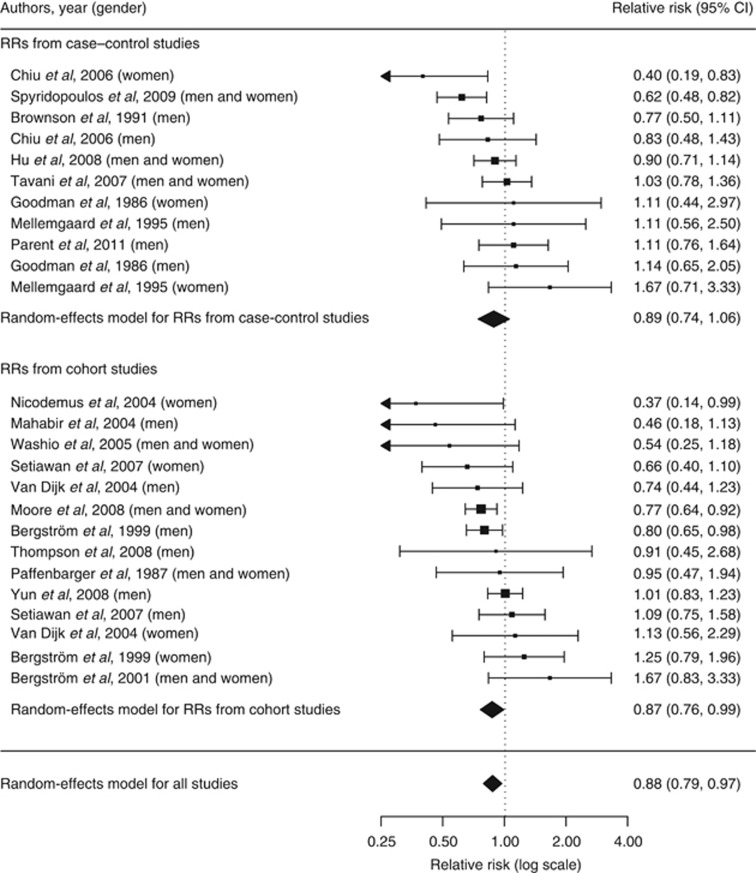

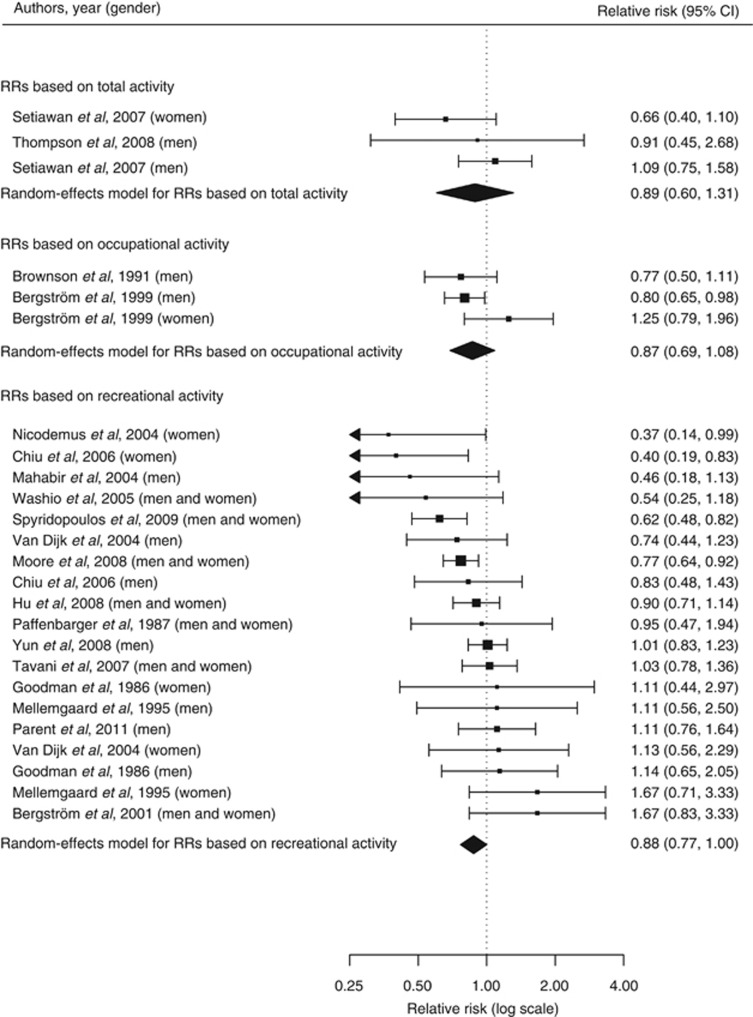

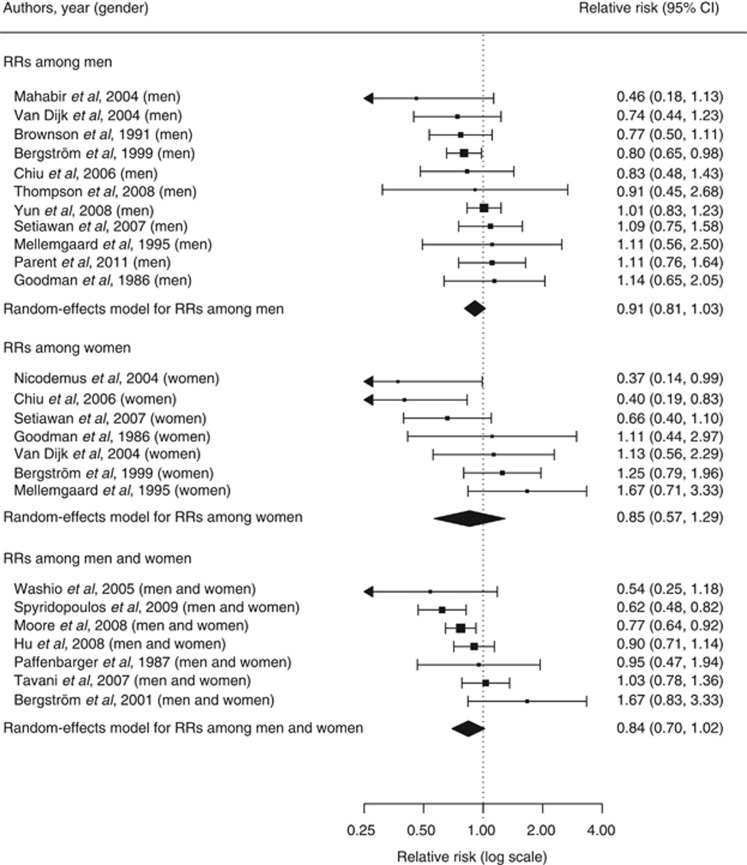

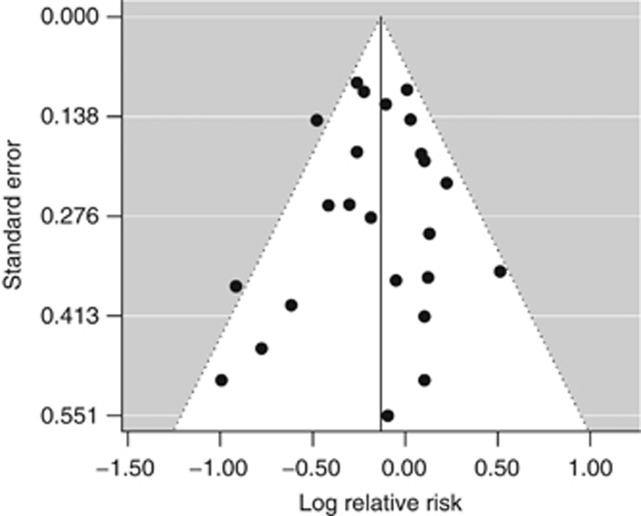

Meta-analysis

The random-effects model summarising the 25 risk estimates with the highest quality scores from each of the 19 studies (Figure 1) revealed a statistically significant 12% reduction in renal cancer risk when comparing a high with a low level of physical activity (RR=0.88; 95% CI=0.79–0.97; I2=33%). The magnitude of that summary risk estimate did not materially change when grouping those 25 risk estimates by study design (Figure 1), physical activity domain (Figure 2), or gender (Figure 3). That meta-analysis combined a total of 2 327 322 subjects and 10 756 cases. No publication bias was indicated by the funnel plot (Figure 4), Egger's regression test (P=0.89), or Begg's rank correlation test (P=0.53).

Figure 1.

Forest plot corresponding to the main random-effects meta-analysis including 25 risk estimates quantifying the relationship between high physical activity and renal cancer risk. Relative risks (RRs) compare high vs low levels of physical activity and are grouped by study design. The size of the box representing each risk estimate is proportional to the weight that the risk estimate contributed to the summary risk estimate.

Figure 2.

Forest plot corresponding to the main random-effects meta-analysis including 25 risk estimates quantifying the relationship between high physical activity and renal cancer risk. Relative risks (RRs) compare high vs low levels of physical activity and are grouped by physical activity domain. The size of the box representing each risk estimate is proportional to the weight that the risk estimate contributed to the summary risk estimate.

Figure 3.

Forest plot corresponding to the main random-effects meta-analysis including 25 risk estimates quantifying the relationship between high physical activity and renal cancer risk. Relative risks (RRs) compare high vs low levels of physical activity and are grouped by gender. The size of the box representing each risk estimate is proportional to the weight that the risk estimate contributed to the summary risk estimate.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot corresponding to the main random-effects meta-analysis including 25 risk estimates quantifying the relationship between high physical activity and renal cancer risk.

Renal cancer end point

Because physical activity may differentially impact the incidence vs mortality of kidney cancer, we repeated the main analysis after excluding the two risk estimates from the papers on kidney cancer mortality (Washio et al, 2005; Thompson et al, 2008). The summary risk estimate remained unchanged (RR=0.88; 95% CI=0.80–0.98).

Potentially influential methodologic factors

In subanalyses investigating potentially influential methodologic factors, all 37 risk estimates were used. The random-effects summary risk estimate (RR=0.90; 95% CI=0.82–0.98; I2=26%) of those 37 risk estimates did not substantially differ from that of the main analysis. We found that the methodologic quality score significantly influenced the magnitude of the summary risk estimate (P=0.02; Table 2) but not the underlying overall variation t2. The best evidence synthesis of studies that fell into the high tertile of the quality score yielded a meta-analysis estimate for the relation of physical activity to renal cancer of 0.78 (95% CI=0.66–0.92; t2=0.02). In contrast, the meta-analysis RRs for studies falling into the intermediate (RR=1.00; 95% CI=0.89–1.13; t2=0) and lower (RR=0.93; 95% CI=0.80–1.07; t2=0.02) tertiles of the quality score were statistically nonsignificant.

When stratifying by the type of physical activity assessment, the summary risk estimates based on frequency of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (RR=0.72; 95% CI=0.53–0.97) or duration of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (RR=0.85; 95% CI=0.69–1.04) appeared to be stronger than those based on energy expenditure (RR=0.97; 95% CI=0.84–1.12) or qualitative physical activity assessments (RR=0.98; 95% CI=0.85–1.14). However, that variation was not statistically significant (P=0.24). Similarly, the magnitude of the inverse association between physical activity and renal cancer appeared to be stronger with a larger number of adjustment factors, although that difference was not statistically significant (P=0.28). The meta-analysis RR for studies in the top tertile of the number of adjustment factors was 0.83 (95% CI=0.71–0.97), whereas the RR for studies in the bottom tertile of the number of adjustment factors was 0.96 (95% CI=0.85–1.08). There was no difference in risk estimates between study designs (RR for case–control studies=0.91; 95% CI=0.79–1.04; RR for cohort studies=0.89; 95% CI=0.80–0.99; P-value for interaction=0.93). Similarly, none of the following remaining study characteristics affected the summary risk estimates: physical activity domain (P=0.84), timing in life of physical activity (P=0.18), gender (P=0.41), geographic region (P=0.63), joint adjustment for smoking and obesity (P=0.31), hypertension adjustment (P=0.30), and diabetes adjustment (P=0.18).

We further examined study characteristics according to the quality score (Table 3). Studies that fell into the top tertile of the quality score tended to employ quantitative physical activity assessments, to investigate recreational activity, to examine recent physical activity, to use a cohort design, and to adjust for smoking, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes. In contrast, studies in the bottom tertile of the quality score tended to employ qualitative physical activity assessments, to investigate occupational activity, to examine past physical activity, to use a case–control design, and to not adjust for smoking, obesity, hypertension, or diabetes.

Table 3. Distribution of methodologic characteristics (absolute frequencies) of all 37 risk estimates by tertile of quality scorea.

| Methodologic characteristics | RRs within upper tertile of quality score | RRs within intermediate tertile of quality score | RRs within lower tertile of quality score |

|---|---|---|---|

|

PA assessment | |||

| RRs based on qualitative PA assessments | 2 | 5 | 11 |

| RRs based on energy expenditure | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| RR based on physical fitness | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| RRs based on MVPA duration | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| RRs based on MVPA frequency |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

PA domain | |||

| RRs based on total activity | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| RRs based on occupational activity | 1 | 4 | 9 |

| RRs based on recreational activity |

8 |

6 |

5 |

|

Timing in life of PA | |||

| RRs based on recent PA | 7 | 5 | 4 |

| RRs based on consistent PA over time | 4 | 5 | 2 |

| RRs based on past PA |

0 |

2 |

8 |

|

Gender | |||

| RRs among men | 5 | 7 | 5 |

| RRs among women | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| RRs among men and women |

3 |

3 |

5 |

|

Study design | |||

| RRs from case-control studies | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| RRs from cohort studies |

8 |

6 |

5 |

|

Study region | |||

| RRs from studies in North America | 5 | 8 | 5 |

| RRs from studies in Europe | 6 | 3 | 7 |

| RRs from studies in Asia |

0 |

1 |

2 |

|

Number of adjustment factorsb | |||

| RRs within upper tertile of number of adjustment factors | 5 | 7 | 0 |

| RRs within intermediate tertile of number of adjustment factors | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| RRs within lower tertile of number of adjustment factors |

4 |

4 |

13 |

|

Adjustment for smoking and obesity | |||

| RRs adjusted for smoking and obesity | 9 | 9 | 5 |

| RRs adjusted for smoking but not obesity | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| RRs adjusted neither for smoking nor obesity |

0 |

3 |

8 |

|

Adjustment for hypertension | |||

| RRs adjusted for hypertension | 7 | 4 | 1 |

| RRs not adjusted for hypertension |

4 |

8 |

13 |

|

Adjustment for diabetes | |||

| RRs adjusted for diabetes | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| RRs not adjusted for diabetes | 9 | 9 | 14 |

Abbreviations: MVPA=moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA=physical activity; RR=relative risk.

The quality scores ranged from 45 to 83 percentage points (out of 100 percentage points), with lower and upper tertile cutoffs of 62 percentage points and 71 percentage points, respectively.

The number of adjustment factors (not counting adjustments for age and sex) ranged between 0 and 12, with lower and upper tertile cutoffs of 3 and 5, respectively.

After adjusting the main random-effects model for study quality (in tertiles), the previously observed heterogeneity (P-heterogeneity=0.03) of risk estimates was no longer evident (P-heterogeneity=0.12).

Discussion

Main results

This comprehensive meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant 12% reduction in renal cancer risk associated with a high vs low level of physical activity.

Potentially influential factors

The summary RR estimate was not affected by individual potentially influential factors, such as type of physical activity assessment, physical activity domain, timing in life of physical activity, gender, study design, study region, number of adjustment factors, and adjustments for smoking, obesity, hypertension, or diabetes. However, the quality score representing a combination of specific factors affected the summary risk estimate. Summary risk estimates based on studies that fell into the top quality score tertile were statistically significantly inverse, whereas summary risk estimates based on studies that fell into the intermediate or bottom quality score tertiles were not. After adjusting for study quality, the previously observed heterogeneity in the random-effects model was no longer statistically significant.

The influence of individual factors was examined in previous meta-analyses of physical activity and cancers of the colorectum (Harriss et al, 2009; Boyle et al, 2012), pancreas (Bao and Michaud, 2008), and prostate (Liu et al, 2011). In agreement with our observations, no statistically significant heterogeneity across gender (Bao and Michaud, 2008; Boyle et al, 2012), study design (Liu et al, 2011), geographic region (Bao and Michaud, 2008; Harriss et al, 2009), physical activity domain (Boyle et al, 2012), or obesity adjustment (Bao and Michaud, 2008; Harriss et al, 2009) was reported.

The influence of a quality score combining several factors was previously studied with respect to the associations between physical activity and cancers of the breast (Monninkhof et al, 2007), endometrium (Voskuil et al, 2007), prostate (Liu et al, 2011), colon (Boyle et al, 2012), and pancreas (O'Rorke et al, 2010). In agreement with our findings, the meta-analysis on physical activity and breast cancer (Monninkhof et al, 2007) detected a more pronounced risk reduction with increased quality score, while the remaining analyses (Voskuil et al, 2007; O'Rorke et al, 2010; Liu et al, 2011; Boyle et al, 2012) did not detect any statistically significant association between quality score and summary risk estimates. Two reviews (O'Rorke et al, 2010; Boyle et al, 2012), however, described decreased variation in risk estimates with increasing quality score. No such observation was made in this study.

Potential biological mechanisms

A high level of physical activity has been shown to reduce adiposity (Wing, 1999), hypertension (Blair et al, 1984), insulin resistance (Rosenthal et al, 1983), circulating levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 (Eliakim et al, 1996, 1998), and lipid peroxidation (Vincent et al, 2002) – factors positively associated with the development of renal carcinoma (Kellerer et al, 1995; Chow et al, 2000; Gago-Dominguez et al, 2002; van Dijk et al, 2004; Vatten et al, 2007; Yuen et al, 2009). Further potential cancer preventing mechanisms include the beneficial effects of physical activity on chronic inflammation and immune function (McTiernan, 2008). It is hypothesised, however, that the effects of physical activity on chronic inflammation are mediated, in part, through avoidance of adiposity. The exact mechanisms linking physical activity to immune function related to tumour suppression have not yet been established, but it is thought that physical activity improves the number or the function of natural killer cells.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first meta-analysis of physical activity and renal cancer. It bears the strengths and limitations inherent in any meta-analysis combining results from studies with heterogeneous study designs (Greenland and O'Rourke, 2008). Particular strengths of the current meta-analysis are that it is based on an extensive systematic literature review, that it rigorously excluded duplicate information induced by overlapping studies, and that it combined information from 19 studies, including a total of 2 327 322 subjects and 10 756 cases. A further strength is that it is among the few meta-analyses of physical activity and a specific type of cancer to assess the heterogeneity of summary estimates by potentially influential factors underlying the RR estimates. The employed quality score addressed potential selection, misclassification, and confounding biases, and accounted for heterogeneity of the results. An inverse association between physical activity and renal cancer risk was observed in analyses including all risk estimates and in analyses including only risk estimates from high-quality studies. In addition, no publication bias was detected.

One limitation of this meta-analysis is the large variation in the underlying studies regarding their definitions of exposure to physical activity – ranging from ‘physically very active' to ‘5 h of vigorous physical activity per week or more'. Similarly, the definitions of physical activity referent groups ranged from ‘not physically active' to ‘<5 h of vigorous physical activity per week'. Such variation did not allow us to conduct stratified analyses according to comparable groups of exposed and non-exposed individuals. Thus, we were not able to identify the specific type, intensity, frequency, and duration of physical activity required to lower renal cancer risk.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our comprehensive meta-analysis provides strong support for an inverse relation of physical activity to the risk of renal cancer. On the basis of high-quality studies, physical activity may decrease the risk of renal cancer by 22%. Future research is required to discern which specific types, intensities, frequencies, and durations of physical activity are needed for renal cancer risk reduction. High-quality studies that employ standardised physical activity assessments and uniform definitions of physical activity are warranted.

Appendix A

Description of quality score

To assess the methodologic quality of studies, we employed a quality score proposed by Voskuil et al (2007). The maximum score was 105. The score addressed selection bias (up to 42 points), misclassification bias (up to 42 points), and confounding bias (up to 21 points). Specifically, the score covered the following 19 items: (1) percentage lost to follow-up (cohort studies, up to 8 points)/percentage response (case–control studies, up to 8 points); (2) difference between percentage response among cases and controls (case–control studies: up to 6 points; cohort studies: 10 points by default); (3) percentage incident cases with known incidence date (vs inclusion of prevalent/fatal cases with unknown incidence date: up to 7 points, independent of study design); (4) cases and controls from the same population (case–control studies: up to 10 points; cohort studies: 10 points by default); (5) same exclusion criteria for cases and controls (case–control studies: up to 7 points; cohort studies: 7 points by default); (6) complete list of recreational physical activities (up to 4 points independent of study design); (7) assessment of total physical activity (up to 4 points); (8) assessment of physical activity intensity and frequency or assessment of physical activity intensity and duration (up to 5 points); (9) source of physical activity information (proxy/self-administered questionnaire/interview) (up to 4 points); (10) definition of physical activity score provided (up to 2 points); (11) examination of past physical activity (up to 4 points); (12) examination of change in physical activity (up to 4 points); (13) use of a valid or reliable physical activity assessment (up to 2 points); (14) minimisation of recall bias (up to 7 points); (15) valid cancer diagnosis (up to 4 points); (16) exclusion of benign cases (up to 2 points); (17) statistical adjustment for potential confounding variables (up to 4 points); (18) comprehensive adjustment for potential confounding variables (up to 9 points); (19) mutual adjustment for recreational and occupational physical activity (up to 8 points). With respect to item 18, we considered the well-established (Scelo and Brennan, 2007) renal cancer risk factors, such as smoking, obesity, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, and awarded points based on how many of those factors had been included in the model (0 points for 0 factors, 4 points for 1 or 2 factors, and 9 points for 3 or 4 factors).

Appendix B

PubMed search strategy

For the PubMed search, last performed on 30 September 2012, we pasted the following search terms all at once into the PubMed search command line:

(physical activity[title/abstract] OR exercise[title/abstract] OR cardiorespiratory fitness[title/abstract] OR cardiovascular fitness[title/abstract] OR resistance training[title/abstract] OR endurance training[title/abstract] OR aerobic[title/abstract] OR sport[title/abstract] OR athletes[title/abstract] OR players[title/abstract] OR lifestyle[title/abstract]) AND (kidney cancer[title] OR renal cancer[title] OR renal cell cancer[title] OR renal carcinoma[title] OR renal cell carcinoma[title] OR cancer[title])

NOT (lung*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (bronchial[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (breast*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (mamma*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (ovar*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (endometr*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (uter*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (cervi*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (gynecolog*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (prostat*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (testic*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (urinary*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (bladder*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (urothelial*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (colon*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (rectal*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (colorectal*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (bowel*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (*digestive*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (gastric*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (stomach*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (oesophag*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (esophag*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (pancrea*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (tract*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (duct*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (tube*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (liver*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (hepato*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (gallbladder*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (oral*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (pharyn*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (nasopharyn*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (laryn*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (lymphoid*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (bone*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (head and neck*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (skin*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (melanoma*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (brain*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (thora*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (thyroid*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (squamous cell*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (basal cell*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (adenoma*[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (multiple[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title]) NOT (mouth[title] NOT renal cancer[title] NOT renal cell cancer[title] NOT kidney cancer[title])

AND (risk[title/abstract] OR incidence[title/abstract] OR mortality[title/abstract])

NOT (surviv*[title] OR prognosis*[title] OR quality of life*[title] OR fatigue*[title] OR pallia*[title] OR cancer patient*[title] OR cancer care*[title] OR recurrence*[title] OR progression*[title] OR clinical outcome*[title] OR chemotherapy*[title] OR radiation*[title] OR radiotherapy*[title] OR rehabilitation*[title] OR recovery*[title] OR cancer diagnosis[title] OR cancer treatment[title] OR cancer surgery[title] OR with cancer[title])

AND English[lang]

NOT (review[ptyp] OR meta-analysis[ptyp] OR editorial[ptyp] OR comment[ptyp] OR letter[ptyp] OR guideline[ptyp] OR news[ptyp]) AND humans[MeSH Terms]

Appendix C

Web of Knowledge search strategy

For the Web of Knowledge search, last performed on 30 September 2012, we specified the following search steps:

#STEP 1 SET LEMMATIZATION=OFF (ADJUST YOUR SEARCH SETTINGS)

#STEP 2 PUT THE FOLLOWING TERMS INTO TOPIC SEARCH

(physical activity OR exercise OR cardiorespiratory fitness OR cardiovascular fitness OR resistance training OR endurance training OR aerobic OR sport OR athletes OR players OR lifestyle) AND (kidney cancer OR renal cancer OR renal cell cancer OR renal carcinoma OR renal cell carcinoma OR cancer)

AND (risk OR incidence OR mortality)

#STEP 3 PUT THE FOLLOWING TERMS INTO TITLE SEARCH

(kidney cancer OR renal cancer OR renal cell cancer OR renal carcinoma OR renal cell carcinoma OR cancer) NOT (lung* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (bronchial NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (breast* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (mamma* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (ovar* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (endometr* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (uter* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (cervi* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (gynecolog* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (prostat* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (testic* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (urinary* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (bladder* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (urothelial* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (colon* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (rectal* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (colorectal* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (bowel* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (*digestive* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (gastric* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (stomach* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (oesophag* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (esophag* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (pancrea* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (tract* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (duct* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (tube* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (liver* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (hepato* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (gallbladder* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (oral* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (pharyn* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (nasopharyn* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (laryn* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (lymphoid* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (bone* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (head and neck* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (skin* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (melanoma* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (brain* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (thora* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (thyroid* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (squamous cell* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (basal cell* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (adenoma* NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (multiple NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer) NOT (mouth NOT renal cancer NOT renal cell cancer NOT kidney cancer)

NOT (surviv* OR prognosis* OR quality of life* OR fatigue* OR pallia* OR cancer patient* OR cancer care* OR recurrence* OR progression* OR clinical outcome* OR chemotherapy* OR radiation* OR radiotherapy* OR rehabilitation* OR recovery* OR cancer diagnosis OR cancer treatment OR cancer surgery OR with cancer)

#STEP 4 SET RESEARCH AREA TO PUBLIC ENVIRONMENTAL OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH

#STEP 5 EXCLUDE ALL DOCUMENT TYPES APART FROM ARTICLE

#STEP 6 SET LANGUAGE TO ENGLISH

Footnotes

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

References

- Bao Y, Michaud DS. Physical activity and pancreatic cancer risk: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2671–2682. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom A, Moradi T, Lindblad P, Nyren O, Adami HO, Wolk A. Occupational physical activity and renal cell cancer: a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:186–191. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991008)83:2<186::aid-ijc7>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom A, Terry P, Lindblad P, Lichtenstein P, Ahlbom A, Feychting M, Wolk A. Physical activity and risk of renal cell cancer. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:155–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair SN, Goodyear NN, Gibbons LW, Cooper KH. Physical fitness and incidence of hypertension in healthy normotensive men and women. JAMA. 1984;252:487–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle P, Ferlay J. Cancer incidence and mortality in Europe, 2004. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:481–488. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle T, Keegel T, Bull F, Heyworth J, Fritschi L. Physical activity and risks of proximal and distal colon cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104 (20:1548–1561. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson RC, Chang JC, Davis JR, Smith CA. Physical activity on the job and cancer in Missouri. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:639–642. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.5.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu BC, Gapstur SM, Chow WH, Kirby KA, Lynch CF, Cantor KP. Body mass index, physical activity, and risk of renal cell carcinoma. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006;30:940–947. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow WH, Gridley G, Fraumeni JF, Jarvholm B. Obesity, hypertension, and the risk of kidney cancer in men. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1305–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011023431804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliakim A, Brasel JA, Mohan S, Barstow TJ, Berman N, Cooper DM. Physical fitness, endurance training, and the growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor I system in adolescent females. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3986–3992. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.11.8923848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliakim A, Brasel JA, Mohan S, Wong WL, Cooper DM. Increased physical activity and the growth hormone-IGF-I axis in adolescent males. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R308–R314. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.1.R308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gago-Dominguez M, Castelao JE, Yuan JM, Ross RK, Yu MC. Lipid peroxidation: a novel and unifying concept of the etiology of renal cell carcinoma (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13:287–293. doi: 10.1023/a:1015044518505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SM, Moore SC, Chow WH, Schatzkin A, Hollenbeck AR, Matthews CE. A prospective analysis of prolonged sitting time and risk of renal cell carcinoma among 300,000 older adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21:787–790. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MT, Morgenstern H, Wynder EL. A case–control study of factors affecting the development of renal cell cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:926–941. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S, O'Rourke K.2008Meta-analysis Modern Epidemiology Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, (eds)3rd edn652–682.Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- Harriss DJ, Atkinson G, Batterham A, George K, Cable NT, Reilly T, Haboubi N, Renehan AG. Lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer risk (2): a systematic review and meta-analysis of associations with leisure-time physical activity. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:689–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Altekruse S, Kosary C, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner M, Lewis D, Chen H, Feuer E, Cronin K.(eds) (2012SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD; availabel at http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/ based on November 2011 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, La Vecchia C, DesMeules M, Negri E, Mery L, Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research G Nutrient and fiber intake and risk of renal cell carcinoma. Nutr Cancer. 2008;60:720–728. doi: 10.1080/01635580802283335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Mao Y, DesMeules M, Csizmadi I, Friedenreich C, Mery L, Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research G Total fluid and specific beverage intake and risk of renal cell carcinoma in Canada. Cancer Epidemiol. 2009;33:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerer M, von Eye Corleta H, Muhlhofer A, Capp E, Mosthaf L, Bock S, Petrides PE, Haring HU. Insulin- and insulin-like growth-factor-I receptor tyrosine-kinase activities in human renal carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1995;62:501–507. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitzmann MF. Physical activity and genitourinary cancer prevention. Recent Results Canc Res. 2011;186:43–71. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-04231-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblad P, Wolk A, Bergstrom R, Persson I, Adami HO. The role of obesity and weight fluctuations in the etiology of renal cell cancer: a population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:631–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Hu F, Li D, Wang F, Zhu L, Chen W, Ge J, An R, Zhao Y. Does physical activity reduce the risk of prostate cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2011;60:1029–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahabir S, Leitzmann MF, Pietinen P, Albanes D, Virtamo J, Taylor PR. Physical activity and renal cell cancer risk in a cohort of male smokers. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:600–605. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTiernan A. Mechanisms linking physical activity with cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:205–211. doi: 10.1038/nrc2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellemgaard A, Engholm G, McLaughlin JK, Olsen JH. Risk factors for renal-cell carcinoma in Denmark. III. Role of weight, physical activity and reproductive factors. Int J Cancer. 1994;56:66–71. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910560113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellemgaard A, Lindblad P, Schlehofer B, Bergstrom R, Mandel JS, McCredie M, McLaughlin JK, Niwa S, Odaka N, Pommer W, Olsen JH. International renal-cell cancer study. III. Role of weight, height, physical activity, and use of amphetamines. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:350–354. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes RJ, Tomlinson G, Kreiger N. Physical activity and risk of renal cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2003;107:642–646. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monninkhof EM, Elias SG, Vlems FA, van der Tweel I, Schuit AJ, Voskuil DW, van Leeuwen FE. Physical activity and breast cancer: a systematic review. Epidemiology. 2007;18:137–157. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000251167.75581.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SC, Chow WH, Schatzkin A, Adams KF, Park Y, Ballard-Barbash R, Hollenbeck A, Leitzmann MF. Physical activity during adulthood and adolescence in relation to renal cell cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:149–157. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicodemus KK, Sweeney C, Folsom AR. Evaluation of dietary, medical and lifestyle risk factors for incident kidney cancer in postmenopausal women. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:115–121. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rorke MA, Cantwell MM, Cardwell CR, Mulholland HG, Murray LJ. Can physical activity modulate pancreatic cancer risk? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:2957–2968. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paffenbarger RS, Hyde RT, Wing AL. Physical activity and incidence of cancer in diverse populations: a preliminary report. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;45:312–317. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.1.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan SY, DesMeules M, Morrison H, Wen SW. Obesity, high energy intake, lack of physical activity, and the risk of kidney cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2453–2460. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent ME, Rousseau MC, El-Zein M, Latreille B, Desy M, Siemiatycki J. Occupational and recreational physical activity during adult life and the risk of cancer among men. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AS, Cerhan JR, Lynch CF, Ershow AG, Cantor KP. Gender, alcohol consumption, and renal cell carcinoma. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:455–462. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.5.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Development Core Team: Vienna, Austria; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M, Haskell WL, Solomon R, Widstrom A, Reaven GM. Demonstration of a relationship between level of physical training and insulin-stimulated glucose utilization in normal humans. Diabetes. 1983;32:408–411. doi: 10.2337/diab.32.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scelo G, Brennan P. The epidemiology of bladder and kidney cancer. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2007;4:205–217. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan VW, Stram DO, Nomura AM, Kolonel LN, Henderson BE. Risk factors for renal cell cancer: the multiethnic cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:932–940. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyridopoulos TN, Petridou ET, Dessypris N, Terzidis A, Skalkidou A, Deliveliotis C, Chrousos GP, Obesity, Cancer Oncology G Inverse association of leptin levels with renal cell carcinoma: results from a case-control study. Hormones (Athens) 2009;8:39–46. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavani A, Zucchetto A, Dal Maso L, Montella M, Ramazzotti V, Talamini R, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Lifetime physical activity and the risk of renal cell cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1977–1980. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AM, Church TS, Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Earnest CP, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a predictor of cancer mortality among men with pre-diabetes and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:764–769. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk BA, Schouten LJ, Kiemeney LA, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Relation of height, body mass, energy intake, and physical activity to risk of renal cell carcinoma: results from the Netherlands Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:1159–1167. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatten LJ, Trichopoulos D, Holmen J, Nilsen TI. Blood pressure and renal cancer risk: the HUNT Study in Norway. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:112–114. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent KR, Vincent HK, Braith RW, Lennon SL, Lowenthal DT. Resistance exercise training attenuates exercise-induced lipid peroxidation in the elderly. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2002;87:416–423. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0640-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voskuil DW, Monninkhof EM, Elias SG, Vlems FA, van Leeuwen FE. Physical activity and endometrial cancer risk, a systematic review of current evidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:639–648. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washio M, Mori M, Sakauchi F, Watanabe Y, Ozasa K, Hayashi K, Miki T, Nakao M, Mikami K, Ito Y, Wakai K, Tamakoshi A, Group JS. Risk factors for kidney cancer in a Japanese population: findings from the JACC Study. J Epidemiol. 2005;15 (Suppl 2:S203–S211. doi: 10.2188/jea.15.S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RT, Wang J, Chinchilli V, Richie JP, Virtamo J, Moore LE, Albanes D. Fish, vitamin D, and flavonoids in relation to renal cell cancer among smokers. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:717–729. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR. Physical activity in the treatment of the adulthood overweight and obesity: current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:S547–S552. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199911001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuen JS, Akkaya E, Wang Y, Takiguchi M, Peak S, Sullivan M, Protheroe AS, Macaulay VM. Validation of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor as a therapeutic target in renal cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1448–1459. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun YH, Lim MK, Won YJ, Park SM, Chang YJ, Oh SW, Shin SA. Dietary preference, physical activity, and cancer risk in men: national health insurance corporation study. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:366. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]