Abstract

Background:

The molecular basis for the development of appendiceal mucinous tumours, which can be a cause of pseudomyxoma peritonei, remains largely unknown.

Methods:

Thirty-five appendiceal mucinous neoplasms were analysed for GNAS and KRAS mutations. A functional analysis of mutant GNAS was performed using a colorectal cancer cell line.

Results:

A mutational analysis identified activating GNAS mutations in 16 of 32 low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (LAMNs) but in none of three mucinous adenocarcinomas (MACs). KRAS mutations were found in 30 LAMNs and in all MACs. We additionally analysed a total of 186 extra-appendiceal mucinous tumours and found that GNAS mutations were highly prevalent in intraductal papillary mucinous tumours of the pancreas (88%) but were rare or absent in mucinous tumours of the colorectum, ovary, lung and breast (0–9%). The prevalence of KRAS mutations was quite variable among the tumours. The introduction of the mutant GNAS into a colorectal cancer cell line markedly induced MUC2 and MUC5AC expression, but did not promote cell growth either in vitro or in vivo.

Conclusion:

Activating GNAS mutations are a frequent and characteristic genetic abnormality of LAMN. Mutant GNAS might play a direct role in the prominent mucin production that is a hallmark of LAMN.

Keywords: low-grade mucinous appendiceal neoplasm, GNAS, KRAS

Primary appendiceal adenocarcinomas are estimated to occur in 1 to 2 per 1 000 000 persons per year (Nielsen et al, 1991; Thomas and Sobin, 1995; Smeenk et al, 2008); among them, mucinous tumours constitute the most common histological type (Carr et al, 1995). The histological classification of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms is controversial because of the frequent discrepancies between the histological findings and clinical behaviour. Previously, appendiceal mucinous neoplasms were classified as either an adenoma or an adenocarcinoma based on histological evidence of invasive growth (Carr et al, 2000). However, unlike ordinary-type adenocarcinomas, appendiceal mucinous tumours may show intraperitoneal spreading even in the absence of high-grade cytological atypia or apparent invasive features (Panarelli and Yantiss, 2011).

Misdraji et al (2003) reviewed 107 cases of appendiceal mucinous neoplasms, and classified them into low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms (LAMNs) and mucinous adenocarcinoma (MAC) based on their architectural complexity and degree of cytological atypia. Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasms lack histological evidence of invasion and exhibit a villous or flat proliferation of mucinous epithelium with low-grade atypia. Meanwhile, MAC is characterised by high-grade cytological atypia and complex epithelial proliferation and often exhibits lymphatic and hematogenous invasion (Misdraji et al, 2003; Carr and Sobin, 2010). Their study showed that while LAMNs may spread outside the appendix, LAMNs were associated with a better prognosis than MACs, indicating the prognostic relevance of this classification (Misdraji et al, 2003). Currently, this classification has been adopted by the World Health Organization classification (Carr and Sobin, 2010).

Appendiceal mucinous tumours may spread throughout the peritoneal cavity, causing the slow but relentless accumulation of mucin, a condition known as pseudomyxoma peritonei (Carr et al, 2012). Over time, mucin accumulation in the peritoneal cavity gradually causes massive symptomatic distension and functional gastrointestinal obstruction. The overall 10-year survival rates of pseudomyxoma peritonei were reported to be 21–45% (Misdraji et al, 2003; Miner et al, 2005), but a recent study reported a rate of 63% for patients treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (Chua et al, 2012).

The molecular basis for the development of appendiceal mucinous tumours remains largely unknown. KRAS mutation is present in the majority of LAMNs and MACs (Szych et al, 1999; Kabbani et al, 2002; Zauber et al, 2011) and is virtually the only recurrent genetic abnormality identified so far. Microsatellite instability and p53 overexpression are reported to be infrequent (Carr et al, 2002; Kabbani et al, 2002; Zauber et al, 2011). Recently, other groups and we have reported the frequent presence of GNAS mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMT) of the pancreas and villous adenoma of the colorectum (Furukawa et al, 2011; Wu et al, 2011; Yamada et al, 2012). Since these two neoplasms share some histopathological features with LAMN, including prominent mucin production and a villous architecture, we suspected the presence of a common genetic abnormality among these tumours. In the present study, we examined the presence of GNAS mutation and its functional significance in LAMNs.

Materials and methods

Study group

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Cancer Center, Tokyo, Japan. A total of 35 appendiceal mucinous tumours were identified in our case files between 1974 and 2012. We also retrieved a total of 186 mucinous tumours of extra-appendiceal origin, including those from the colorectum, ovary, pancreas, lung and breast. Tissue samples were provided by the National Cancer Center Biobank, Japan.

Histological analysis

All the tissue samples were obtained by surgical resection and were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms were histologically re-evaluated and classified into LAMN and MAC based on the definitions proposed by Misdraji et al, 2003. Tumour samples of the primary site were not available for four LAMNs, and specimens obtained from peritoneal or omental deposits were analysed in these cases.

Immunohistochemistry was performed for all the appendiceal mucinous tumours. Deparaffinised 4-μm-thick sections from each paraffin block were exposed to 0.3% hydrogen peroxide for 15 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Antigen retrieval was performed by autoclaving in a 10-mℳ citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 10 min. Anti-MUC2 (Ccp58; 1 : 200 dilution; Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, England) and anti-MUC5AC (CLH2; 1 : 200 dilution; Novocastra) were used as the primary antibodies. For staining, we used an automated stainer (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) according to the vendor's protocol. ChemMate EnVision (Dako) methods were used for detection. The immunohistochemistry for MUC2 and MUC5AC were scored as: 0, <10% positive cells; +1, 11–50% positive cells; +2, >50% positive cells.

Mutation analysis

In all, 10-μm sections of the tumour specimens were stained briefly with haematoxylin and used for DNA extraction. The tumour epithelium was dissected using sterilised toothpicks under a microscope. The dissected samples were incubated in 50 μl of DNA extraction buffer (50 mℳ Tris–HCL, pH 8.0, 1 mℳ ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.5% (v/v) Tween 20, 200 μg ml−1 proteinase K) at 50 °C overnight. Proteinase K was inactivated by heating at 100 °C for 10 min. The samples were subjected to a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using pairs of primers encompassing exons 8 and 9 of GNAS and exon 2 of KRAS, which contain frequently mutated regions (Table 1). The PCR products were electrophoresed in a 2% (w/v) agarose gel and were recovered using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Isolated PCR products were sequenced using an Applied Biosystems 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster, CA, USA). When GNAS mutations were detected, the corresponding non-neoplastic tissues were additionally analysed to confirm their somatic nature.

Table 1. Primer sequences.

| Application | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Probe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

GNAS exon 8 |

Mutation analysis |

ACTGTTTCGGTTGGCTTTGGTGA |

AGGGACTGGGGTGAATGTCAAGA |

|

|

GNAS exon 9 |

Mutation analysis |

GACATTCACCCCAGTCCCTCTGG |

GAACAGCCAAGCCCACAGCA |

|

|

KRAS exon 2 |

Mutation analysis |

AGGCCTGCTGAAAATGACTG |

GGTCCTGCACCAGTAATATGCA |

|

|

GNAS transgene |

RT–PCR |

GACTGCCATCATCTTCGTGGTG |

GAGTGGTGTAGCGAGCGAACT |

|

|

Zeor |

RT–PCR |

CAAGTTGACCAGTGCCGTTC |

GACACGACCTCCGACCAC |

|

|

ACTB |

RT–PCR |

AGACCTGTACGCCAACACAG |

CGGACTCGTCATACTCCTGC |

|

|

MUC2 |

qRT–PCR |

GACCTCCAGCACAGTTTTATCA |

GGTGGTCCTCATTGATCCAG |

#34 |

|

MUC5AC |

qRT–PCR |

AGCACCAGTGCCCAAGTCT |

ACTCCTGGCAGTCCATGC |

#43 |

| GUSB | qRT–PCR | CGCCCTGCCTATCTGTATTC | TCCCCACAGGGAGTGTGTAG | #57 |

Abbreviation: RT–PCR=reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction.

In tumours concurrently harbouring two nucleotide substitutions in GNAS, the PCR products were subcloned using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA) and each clone was sequenced as described above.

Cell culture

The colorectal cancer cell line HT29, which has wild-type GNAS and KRAS and mutant BRAF alleles (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/CellLines/), was obtained from the National Cancer Institute tumour repository (Frederick, MD, USA) and was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. HA-tagged rat GNASR201H cDNA (Bastepe et al, 2004) was subcloned into the EF1a-IRES-Zeo plasmid to generate an EF1a-GNASR201H-IRES-Zeo plasmid that expresses GNASR201H and the Zeocin-resistant gene as a single transcript under the control of the EF1a promoter. The HT29 cells were transfected with an EF1a-GNASR201H-IRES-Zeo or control EF1a-IRES-Zeo plasmid and cultured in the presence of 20 μg ml−1 of Zeocin for 3 weeks to obtain stable transfectants. The Zeocin-resistant cells were expanded in bulk culture, to avoid any biases resulting from cloning and were then subjected to further analysis.

For the cell proliferation assay, 1 × 105 cells were seeded into 12-cell culture plates in triplicate and counted after 1–3 days. To inhibit PKA activity, 20 nℳ of H-89 (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was added to the culture medium.

Reverse transcription–PCR

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and conventional PCR were performed using standard protocols. For conventional reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR), the PCR products were electrophoresed in an agarose gel and visualised under UV light with ethidium bromide staining. Quantitative RT–PCR (qRT–PCR) reactions were performed in triplicate using FastStart Universal Probe Master (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany). The expression level of each gene was determined using GUSB as a standard, as previously described (Sekine et al, 2011). The primer sequences and probes used are listed in Table 1.

cAMP assay

Two thousand cells were seeded into 96-well cell culture plates and cultured overnight. After incubation in serum-free media containing 500 μℳ IBMX and 100 μℳ Ro20-1724 for 15 min, cAMP levels were measured using the cAMP-Glo Max Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The assays were done in triplicate.

Animal experiments

The mice used in the present study were maintained in barrier facilities according to the protocols approved by the Committee for Ethics in Animal Experimentation at the National Cancer Center, Japan. Five-week-old nu/nu athymic BALB/c mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 3 × 106 tumour cells. Three weeks later, the mice were sacrificed and the tumours were weighed and analysed histologically. Ten xenografts were analysed for each group.

Statistical analysis

The Fisher exact test was used to analyse each two-by-two table. Comparisons of continuous variables were using the Welch t-test. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

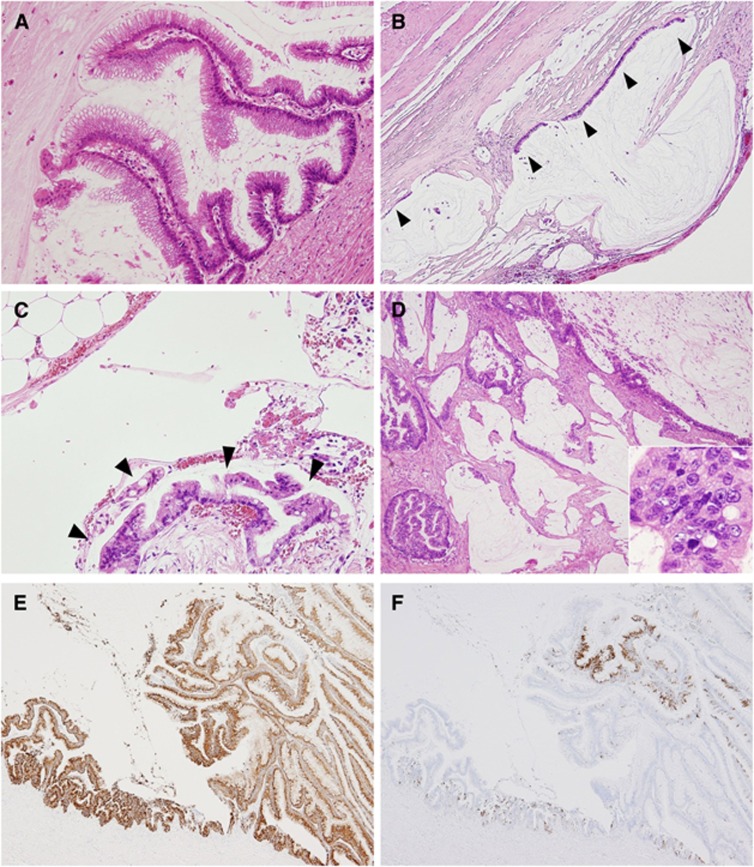

Histological re-evaluation showed that the 35 mucinous appendiceal tumours consisted of 32 LAMNs and 3 MACs (Figure 1A–D; Table 2). Sixteen LAMNs had serosal exposure as determined by histology, and 15 of them had peritoneal deposits. All the MACs had serosal exposure and two cases had peritoneal deposits. Lymph node metastasis was observed in two MACs but in none of the LAMNs. Immunohistochemically, all the LAMNs and two of the three MACs diffusely expressed MUC2 (Figure 1E). The focal or diffuse expression of MUC5AC was observed in 24 LAMNs and in all the MACs (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Histology of appendiceal mucinous tumours. (A–E) Histological and immunohistochemical findings of LAMN (A–C, E, F) and MAC (D). LAMN exhibiting a villous growth pattern (A). The tumour cells had low-grade cytological atypia. Mucin pools were present in the subserosal layer and were partly lined by mucinous epithelium (arrowheads). The stroma showed hyalinizing fibrosis (B). Peritoneal deposits of LAMN (C). Low-grade tumour cells grew on the surface of the omentum without evidence of stromal invasion (arrowheads) (C). MAC. Abundant mucin production and a frankly invasive growth pattern were evident. The tumour cells showed cytologically high-grade atypia, with a high nuclear–cytoplasmic ratio and prominent nucleoli (inset) (D). LAMN exhibiting diffuse MUC2 expression (E) and focal MUC5AC expression (F).

Table 2. Clinicopathological features and mutation statuses of appendiceal mucinous tumours.

| Age/sex | Histology | Serosal exposure | Peritoneal implant | LN | MUC2a | MUC5ACa | GNAS | KRAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

30/M |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

− |

— |

c.35G>A |

| 2 |

59/F |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.602G>A |

c.35G>A |

| 3 |

72/M |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

− |

— |

c.34G>T |

| 4 |

63/F |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.601C>T |

c.35G>T |

| 5 |

62/F |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

− |

— |

— |

| 6 |

53/M |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

1+ |

c.602G>A |

c.38G>A |

| 7 |

71/F |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

1+ |

— |

c.35G>T |

| 8 |

77/F |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.602G>A |

— |

| 9 |

82/M |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.602G>A |

c.35G>A |

| 10 |

72/M |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

1+ |

c.602G>A |

c.35G>T |

| 11 |

55/F |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

1+ |

— |

c.38G>A |

| 12 |

55/M |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

− |

— |

c.35G>A |

| 13 |

72/M |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

− |

— |

c.35G>A |

| 14 |

40/M |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

− |

— |

c.35G>A |

| 15 |

84/F |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.602G>A |

c.35G>T |

| 16 |

70/M |

LAMN |

− |

− |

− |

2+ |

1+ |

— |

c.35G>A |

| 17 |

66/F |

LAMN |

+ |

− |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

— |

c.35G>C |

| 18 |

56/F |

LAMN |

+ |

+ |

− |

2+ |

− |

— |

c.35G>A |

| 19 |

52/F |

LAMN |

+ |

+ |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.601C>T |

c.35G>T |

| 20 |

82/F |

LAMN |

+ |

+ |

− |

2+ |

1+ |

— |

c.38G>A |

| 21 |

47/M |

LAMN |

+ |

+ |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

— |

c.35G>A |

| 22 |

52/F |

LAMN |

+ |

+ |

− |

2+ |

− |

c.601C>T, c.602G>A |

c.35G>A |

| 23 |

59/M |

LAMN |

+ |

+ |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.601C>T |

c.35G>T |

| 24 |

69/F |

LAMN |

+ |

+ |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

— |

c.35G>T |

| 25 |

51/F |

LAMN |

+ |

+ |

− |

2+ |

1+ |

— |

c.35G>T |

| 26 |

49/F |

LAMN |

+ |

+ |

− |

2+ |

1+ |

— |

c.35G>T |

| 27 |

69/F |

LAMN |

+ |

+ |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.602G>A |

c.35G>T |

| 28 |

64/F |

LAMN |

+ |

+ |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.601C>T, c.602G>A |

c.38G>A |

| 29 |

56/M |

LAMNb |

N/A |

+ |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.601C>T |

c.35G>A |

| 30 |

57/F |

LAMNb |

N/A |

+ |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.601C>T |

c.35G>A |

| 31 |

67/F |

LAMNb |

N/A |

+ |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.601C>A |

c.35G>A |

| 32 |

68/M |

LAMNb |

N/A |

+ |

− |

2+ |

2+ |

c.601C>T |

c.35G>T |

| 33 |

58/F |

MAC |

+ |

− |

− |

2+ |

1+ |

— |

c.34G>A |

| 34 |

57/M |

MAC |

+ |

− |

+ |

2+ |

1+ |

— |

c.35G>A |

| 35 | 51/M | MAC | + | + | + | − | 1+ | — | c.35G>A |

Abbreviations: LN=lymph node metastasis; M=male; F=female; LAMN=low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm; MAC=mucinous adenocarcinoma; N/A=not assessed.

The immunohistochemistry for MUC2 and MUC5AC were scored as: 0, <10% positive cells; +1, 11–50% positive cells; +2, >50% positive cells.

Tumour specimens of primary appendiceal tumours were unavailable and thus peritoneal (cases 29–31) or omental (case 32) deposits were analysed.

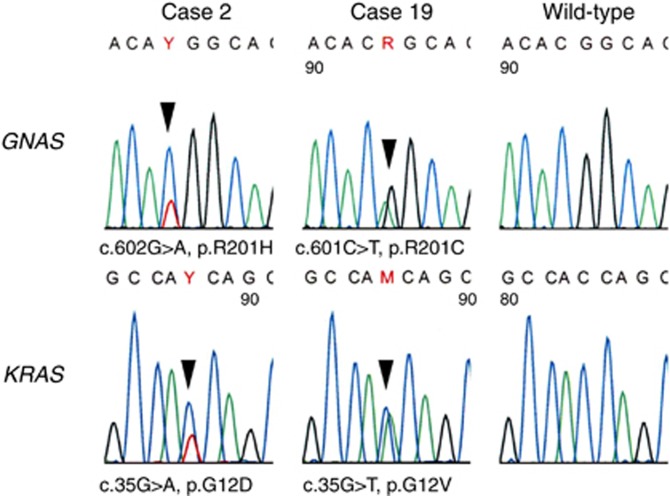

Mutational analyses identified activating GNAS mutations in 16 LAMNs (50%) but in none of the MACs (Figure 2; Table 2). Two LAMNs had two GNAS mutations concurrently, and subcloning analyses showed that these mutations were on different alleles in both cases. No GNAS mutations were identified in the non-neoplastic tissues, indicating the somatic nature of these mutations. KRAS mutations were observed in 30 LAMNs (94%) and in all the MACs that were examined.

Figure 2.

GNAS and KRAS mutations in LAMNs. Representative GNAS and KRAS mutations identified in LAMNs. Missense mutations are indicated by the arrowheads. All the samples were sequenced using reverse primers.

Statistical analyses showed that the presence of GNAS mutations was correlated with the expression of MUC5AC (+ or 2+ vs −, P=0.037), but not with age (⩽60 year-old vs >60 year-old, P=1.0), sex (male vs female, P=1.0), or the presence of peritoneal deposits (present vs absent, P=0.47) among LAMNs. Because of the highly prevalent KRAS mutations and consistent MUC2 expression, these two factors were excluded from the analysis.

Based on the frequent presence of GNAS and KRAS mutations in LAMN, we further analysed mucinous tumours of other organs to clarify whether they shared a common set of genetic alterations. The analysis showed that GNAS mutations were highly common in IPMT of the pancreas but were rare or absent in mucinous tumours of other organs (Table 3). Thus, the presence of activating GNAS mutations is relatively organ-specific. The prevalence of KRAS mutations, on the other hand, was highly variable: these mutations frequently occurred in mucinous borderline tumours of the ovary, followed by MAC of the lung and IPMT of the pancreas. On the other hand, none of the MACs of the breast had KRAS mutations.

Table 3. GNAS and KRAS mutations in mucinous tumours of diverse organs.

| |

|

GNAS | KRAS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Histology | N | Total mutated | n | Nucleotide | Amino acid | Total mutated | n | Nucleotide | Amino acid |

| Appendix |

Low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm |

32 |

16 (50%) |

1 |

c.601C>A |

p.R201S |

30 (94%) |

1 |

c.34G>T |

p.G12C |

| |

|

|

|

6 |

c.601C>T |

p.R201C |

|

13 |

c.35G>A |

p.G12D |

| |

|

|

|

7 |

c.602G>A |

p.R201H |

|

1 |

c.35G>C |

p.G12A |

| |

|

|

|

2 |

c.601C>T, c.602G>A |

p.R201C, p.R201H |

|

11 |

c.35G>T |

p.G12V |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

c.38G>A |

p.G13D |

| |

Mucinous adenocarcinoma |

3 |

0 |

|

|

|

3 (100%) |

1 |

c.34G>A |

p.G12S |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

c.35G>A |

p.G12D |

| Colorectum |

Mucinous adenocarcinoma |

33 |

3 (9%) |

1 |

c.601C>T |

p.R201C |

9 (27%) |

4 |

c.35G>A |

p.G12D |

| |

|

|

|

2 |

c.602G>A |

p.R201H |

|

4 |

c.35G>T |

p.G12V |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

c.38G>A |

p.G13D |

| Ovary |

Mucinous cystadenoma |

23 |

2 (9%) |

1 |

c.602G>A |

p.R201H |

7 (30%) |

2 |

c.35G>A |

p.G12D |

| |

|

|

|

1 |

c.601C>T, c.602G>A |

p.R201C, p.R201H |

|

5 |

c.35G>T |

p.G12V |

| |

Mucinous borderline tumour |

24 |

0 |

|

|

|

21 (88%) |

1 |

c.34G>C |

p.G12R |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11 |

c.35G>A |

p.G12D |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

c.35G>T |

p.G12V |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

c.37G>T |

p.G13C |

| |

Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma |

15 |

0 |

|

|

|

8 (53%) |

1 |

c.34G>C |

p.G12R |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

c.35G>A |

p.G12D |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

c.35G>T |

p.G12V |

| Pancreas |

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm |

37 |

30 (81%) |

1 |

c.601C>A |

p.R201S |

25 (68%) |

1 |

c.34G>A |

p.G12S |

| |

|

|

|

15 |

c.601C>T |

p.R201C |

|

3 |

c.34G>C |

p.G12R |

| |

|

|

|

12 |

c.602G>A |

p.R201H |

|

7 |

c.35G>A |

p.G12D |

| |

|

|

|

2 |

c.601C>T, c.602G>A |

p.R201C, p.R201H |

|

13 |

c.35G>T |

p.G12V |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

c.38G>A |

p.G13D |

| Lung |

Mucinous adenocarcinomaa |

18 |

0 |

|

|

|

14 (78%) |

2 |

c.34G>T |

p.G12C |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

c.35G>A |

p.G12D |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

c.35G>T |

p.G12V |

| Breast | Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 36 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

N, total number of examined lesions; n, lesions with each mutation.

Formerly mucinous-bronchioloalveolar carcinoma.

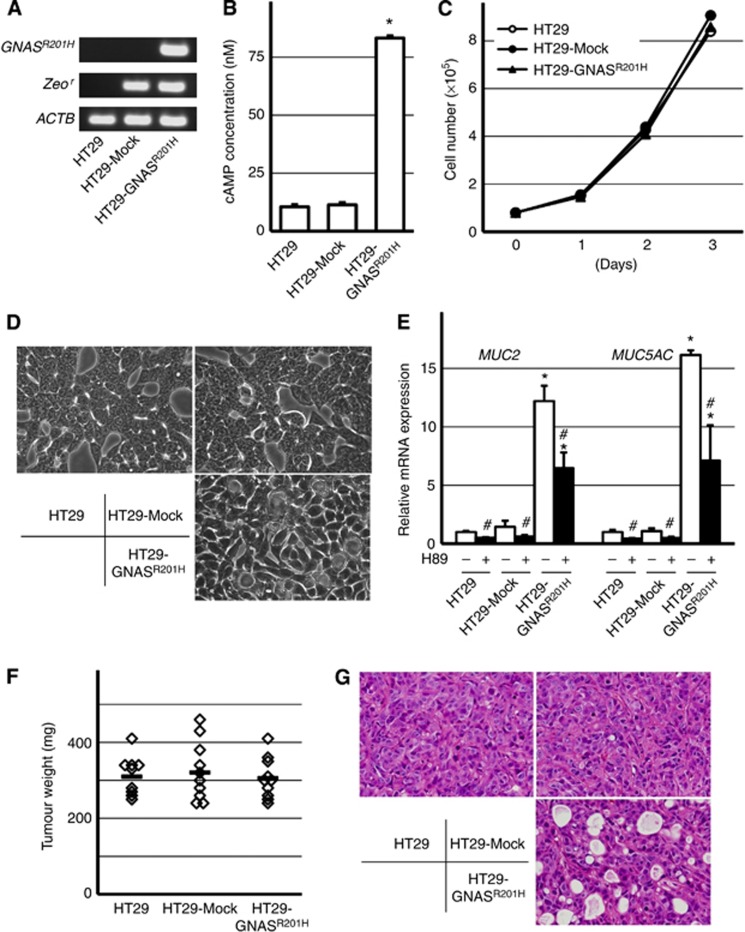

To probe the functional significance of the GNAS mutation, we established a colorectal cancer cell line stably expressing GNASR201H (Figure 3A, hereafter referred to as HT29-GNASR201H cells). The expression of GNASR201H protein was confirmed using western blotting (data not shown). As expected, the introduction of GNASR201H led to an elevated level of cAMP but did not alter cell proliferation in vitro (Figure 3B and C). However, morphologically, the HT29-GNASR201H cells showed the prominent formation of cytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 3D). Furthermore, a quantitative RT–PCR analysis showed remarkable increases in MUC2 and MUC5AC expression (Figure 3E). The expressions of MUC2 and MUC5AC were partly downregulated by the addition of the PKA inhibitor H89, supporting the role of the cAMP-PKA pathway in the regulation of mucin production.

Figure 3.

Introduction of GNASR201H into the colorectal cancer cell line HT29 promotes mucin expression and luminal formation. (A) Establishment of HT29 cells stably expressing a mutant GNAS. RT–PCR analysis showed the expression of the GNASR201H transgene in HT29-GNASR201H cells. The Zeocin-resistant gene (Zeor) was expressed in HT29-GNASR201H cells and the mock transfectant. ACTB served as a positive control. (B) Elevated cAMP level in HT29-GNASR201H cells. The bars indicate averages+s.d. *P<0.05. (C) Cell proliferation assay in vitro. The graphs indicate the average cell numbers of triplicate experiments. HT29-GNASR201H cells did not show altered cell proliferation. (D) Cell morphology in vitro. HT29-GNASR201H cells showed prominent intracytoplasmic vacuoles compared with parental HT29 and the mock transfectant. (E) Increased mucin expression in HT29-GNASR201H cells. Cells were cultured in the presence or absence of a PKA inhibitor, H89, and the MUC2 and MUC5AC expression levels were determined using qRT–PCR. Bars indicate averages+s.d. *P<0.05 (compared with parental HT29); #P<0.05 (compared with H89–). (F) Tumourigenicity in vivo. A total of 3 × 106 cells were implanted into nude mice subcutaneously, and the tumours were weighed 3 weeks later. No significant difference in tumour weight was observed between the groups. The horizontal bars indicate the averages. (G) Histology of tumour xenografts. Parental HT29 and mock-transfected cells mainly showed a solid growth pattern with a few small intracytoplasmic lumina, whereas HT29-GNASR201H cells exhibited prominent luminal formation.

Next, we transplanted the HT29-GNASR201H cells and the controls subcutaneously into nu/nu athymic BALB/c mice. No significant difference in tumour growth was seen as determined by the tumour weight at 3 weeks after implantation (Figure 3F). A histological analysis showed that the transplanted HT29-GNASR201H cells exhibited more pronounced luminal formation compared with the controls (Figure 3G). Overall, the introduction of GNASR201H did not alter cell growth but significantly promoted mucin production in HT29 cells.

Discussion

The present study identified GNAS mutations in half of the LAMNs that were examined. All the mutations that were identified have been previously reported in other tumours and have been shown to be activating mutations (Landis et al, 1989; Lyons et al, 1990; Furukawa et al, 2011; Wu et al, 2011; Yamada et al, 2012). Additionally, in agreement with previous studies, a large majority of LAMNs and MACs harboured activating KRAS mutations (Szych et al, 1999; Kabbani et al, 2002; Zauber et al, 2011). Remarkably, GNAS mutations often co-existed with KRAS mutations also in various gastrointestinal tumours (Furukawa et al, 2011; Wu et al, 2011; Matsubara et al, 2012; Yamada et al, 2012). The concurrent occurrence of GNAS and KRAS mutations in LAMNs is an additional example of the co-existence of these two genetic alterations and implies a functional interaction of these two oncogenes during tumourigenesis.

Among the tumours of digestive organs, GNAS mutations frequently occur in IPMT of the pancreas, villous adenomas of the colorectum, and pyloric gland adenomas of the stomach and duodenum (Furukawa et al, 2011; Wu et al, 2011; Matsubara et al, 2012; Yamada et al, 2012). On the other hand, GNAS mutations are rare or absent in ordinary-type adenocarcinomas of these organs (Lee et al, 2008; Matsubara et al, 2012; Yamada et al, 2012). These observations imply that GNAS mutations might be preferentially associated with tumours with a benign or indolent biological behaviour. In this context, it is intriguing that MACs, which represent high-grade appendiceal mucinous tumours, lacked GNAS mutations; however, since only three MACs were included in our case series, further analyses are needed to confirm whether GNAS mutations are exclusively present in LAMNs among mucinous appendiceal tumours.

Because prominent mucin production is a common feature of LAMN and IPMN, both of which have frequent GNAS and KRAS mutations (Furukawa et al, 2011; Wu et al, 2011), we additionally analysed mucinous tumours of diverse organs for these mutations. The results showed that GNAS mutations were present in a rather organ-specific manner, whereas the prevalence of KRAS mutations was highly variable among each type of tumours. The distinct mutational profiles of GNAS and KRAS mutations might be potentially helpful in determining the origins of metastatic mucinous tumours in clinical situations.

GNAS encodes the α-subunit of a stimulatory G-protein (Gαs), which transduces signals from seven-transmembrane receptors to the cAMP-generating enzyme adenylyl cyclase. GNAS mutations cause the constitutive activation of adenylyl cyclase and an elevated cAMP level, regardless of the presence or absence of receptor agonists (Landis et al, 1989; Lyons et al, 1990). We used a colorectal cancer cell line HT29 for a functional analysis of mutant GNAS because this cell line is reportedly capable of differentiating into mucin-secreting cells upon appropriate stimuli (Velcich and Augenlicht, 1993). As expected, the introduction of mutant GNAS resulted in an elevated level of cAMP, but did not promote cell growth either in vitro or in vivo. While mutant GNAS likely promotes tumourigenesis, our observation might be consistent with the indolent biological behaviour of LAMN.

On the other hand, the expressions of MUC2 and MUC5AC were markedly induced by mutant GNAS and were partly inhibited by the PKA inhibitor, H89, implying a regulatory role of the Gαs-cAMP-PKA pathway in mucin gene expression. Indeed, previous studies have reported that cAMP-dependent signalling induces mucin production in various cell types, including colorectal cancers (Laburthe et al, 1989; Hokari et al, 2005; Song et al, 2009). These findings suggest that mutant GNAS might play a direct role in prominent mucin production, which is a hallmark of LAMN. On the other hand, considering the fact that LAMNs consistently express mucins (particularly MUC2) regardless of the presence or absence of GNAS mutations, additional mechanisms might be responsible for the mucin production in LAMN.

Even though mutant GNAS upregulated mucin production in HT29 cells, the mouse xenografts did not form mucin pools, a histological determinant of mucinous tumours. We also performed intraperitoneal injections of HT29-GNASR201H cells, but this procedure did not reproduce the phenotypes of pseudomyxoma peritonei and instead resulted in the formation of solid tumours (data not shown). This outcome is probably a limitation related to the use of established cancer cell lines, which have a higher proliferative activity than LAMN. While challenging, the modulation of non-transformed appendiceal or colon epithelium might be required to establish a model of pseudomyxoma peritonei.

The present study revealed the frequent presence of activating GNAS mutations in LAMN. GNAS mutations are also common in IPMT of the pancreas, but are rare or absent among mucinous tumours of other organs. Our analysis also suggested a direct role of mutant GNAS in mucin production in LAMN. Since exaggerated mucin production is responsible for the major complications in pseudomyxoma peritonei, the cAMP pathway might be a potential therapeutic target for this disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Murat Bastepe (Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School) for the generous gift of GNASR201H cDNA and Ms Sachiko Miura and Ms Chizu Kina for skillful technical assistance. This study was supported by Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Research Grant from the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD); the grand for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan; and the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (23-A-11).

Footnotes

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

References

- Bastepe M, Weinstein LS, Ogata N, Kawaguchi H, Juppner H, Kronenberg HM, Chung UI. Stimulatory G protein directly regulates hypertrophic differentiation of growth plate cartilage in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101 (41:14794–14799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405091101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr NJ, Arends MJ, Deans GT, Sobin LH. WHO Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. IRAC Press: Lyon; 2000. Adenocarcinoma of the appendix; pp. 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Carr NJ, Emory TS, Sobin LH. Epithelial neoplasms of the appendix and colorectum: an analysis of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and expression of p53, CD44, bcl-2. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126 (7:837–841. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-0837-ENOTAA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr NJ, Finch J, Ilesley IC, Chandrakumaran K, Mohamed F, Mirnezami A, Cecil T, Moran B. Pathology and prognosis in pseudomyxoma peritonei: a review of 274 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65 (10:919–923. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-200843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr NJ, McCarthy WF, Sobin LH. Epithelial noncarcinoid tumors and tumor-like lesions of the appendix. A clinicopathologic study of 184 patients with a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer. 1995;75 (3:757–768. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950201)75:3<757::aid-cncr2820750303>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr NJ, Sobin LH. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System, 4th Edition. IRAC Press: Lyon; 2010. Adenocarcinoma of the appendix; pp. 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chua TC, Moran BJ, Sugarbaker PH, Levine EA, Glehen O, Gilly FN, Baratti D, Deraco M, Elias D, Sardi A, Liauw W, Yan TD, Barrios P, Gomez Portilla A, de Hingh IH, Ceelen WP, Pelz JO, Piso P, Gonzalez-Moreno S, Van Der Speeten K, Morris DL. Early- and long-term outcome data of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal origin treated by a strategy of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30 (20:2449–2456. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Kuboki Y, Tanji E, Yoshida S, Hatori T, Yamamoto M, Shibata N, Shimizu K, Kamatani N, Shiratori K. Whole-exome sequencing uncovers frequent GNAS mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Sci Rep. 2011;1:161. doi: 10.1038/srep00161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokari R, Lee H, Crawley SC, Yang SC, Gum JR, Miura S, Kim YS. Vasoactive intestinal peptide upregulates MUC2 intestinal mucin via CREB/ATF1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289 (5:G949–G959. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00142.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabbani W, Houlihan PS, Luthra R, Hamilton SR, Rashid A. Mucinous and nonmucinous appendiceal adenocarcinomas: different clinicopathological features but similar genetic alterations. Mod Pathol. 2002;15 (6:599–605. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laburthe M, Augeron C, Rouyer-Fessard C, Roumagnac I, Maoret JJ, Grasset E, Laboisse C. Functional VIP receptors in the human mucus-secreting colonic epithelial cell line CL.16E. Am J Physiol. 1989;256 (3 Pt 1:G443–G450. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1989.256.3.G443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis CA, Masters SB, Spada A, Pace AM, Bourne HR, Vallar L. GTPase inhibiting mutations activate the alpha chain of Gs and stimulate adenylyl cyclase in human pituitary tumours. Nature. 1989;340 (6236:692–696. doi: 10.1038/340692a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Jeong EG, Soung YH, Lee JW, Yoo NJ. Absence of GNAS and EGFL6 mutations in common human cancers. Pathology. 2008;40 (1:95–97. doi: 10.1080/00313020701716375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons J, Landis CA, Harsh G, Vallar L, Grunewald K, Feichtinger H, Duh QY, Clark OH, Kawasaki E, Bourne HR, et al. Two G protein oncogenes in human endocrine tumors. Science. 1990;249 (4969:655–659. doi: 10.1126/science.2116665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara A, Sekine S, Kushima R, Ogawa R, Taniguchi H, Tsuda H, Kanai Y.2012Frequent GNAS and KRAS mutations in pyloric gland adenoma of the stomach and duodenum J Pathole-pub ahead of prime 3 December 2012doi: 10.1002/path.4153 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Miner TJ, Shia J, Jaques DP, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF, Coit DG. Long-term survival following treatment of pseudomyxoma peritonei: an analysis of surgical therapy. Ann Surg. 2005;241 (2:300–308. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000152015.76731.1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misdraji J, Yantiss RK, Graeme-Cook FM, Balis UJ, Young RH. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a clinicopathologic analysis of 107 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27 (8:1089–1103. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen GP, Isaksson HJ, Finnbogason H, Gunnlaugsson GH. Adenocarcinoma of the vermiform appendix. APMIS; A population study. 1991;99 (7:653–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1991.tb01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panarelli NC, Yantiss RK. Mucinous neoplasms of the appendix and peritoneum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135 (10:1261–1268. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2011-0034-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine S, Ogawa R, Kanai Y. Hepatomas with activating Ctnnb1 mutations in ‘Ctnnb1-deficient' livers: a tricky aspect of a conditional knockout mouse model. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32 (4:622–628. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeenk RM, van Velthuysen ML, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FA. Appendiceal neoplasms and pseudomyxoma peritonei: a population based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34 (2:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song KS, Choi YH, Kim JM, Lee H, Lee TJ, Yoon JH. Suppression of prostaglandin E2-induced MUC5AC overproduction by RGS4 in the airway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296 (4:L684–L692. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90396.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szych C, Staebler A, Connolly DC, Wu R, Cho KR, Ronnett BM. Molecular genetic evidence supporting the clonality and appendiceal origin of Pseudomyxoma peritonei in women. Am J Pathol. 1999;154 (6:1849–1855. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65442-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas RM, Sobin LH. Gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer. 1995;75 (1 Suppl:154–170. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950101)75:1+<154::aid-cncr2820751305>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velcich A, Augenlicht LH. Regulated expression of an intestinal mucin gene in HT29 colonic carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268 (19:13956–13961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Matthaei H, Maitra A, Dal Molin M, Wood LD, Eshleman JR, Goggins M, Canto MI, Schulick RD, Edil BH, Wolfgang CL, Klein AP, Diaz LA, Allen PJ, Schmidt CM, Kinzler KW, Papadopoulos N, Hruban RH, Vogelstein B. Recurrent GNAS mutations define an unexpected pathway for pancreatic cyst development. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3 (92:92ra66. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Sekine S, Ogawa R, Taniguchi H, Kushima R, Tsuda H, Kanai Y. Frequent activating GNAS mutations in villous adenoma of the colorectum. J Pathol. 2012;228 (1:113–118. doi: 10.1002/path.4012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zauber P, Berman E, Marotta S, Sabbath-Solitare M, Bishop T. Ki-ras gene mutations are invariably present in low-grade mucinous tumours of the vermiform appendix. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46 (7-8:869–874. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.565070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]