Abstract

Aims:

To evaluate the efficacy of Aloe Vera mouth rinse on experimental plaque accumulation and gingivitis.

Materials and Methods:

In this randomized, controlled, and double-blind study, a total of 148 systemically healthy subjects were screened in the age group of 18-25 years. Finally, 120 subjects were requested to abstain from oral hygiene (tooth brushing) for 14 days and used a specially fabricated plaque guard. Following cessation of tooth brushing in the specified area, the subjects were randomly divided into Group A (test group) who received 100% Aloe vera, Group B (negative control group) who received placebo (distilled water), and Group C (positive control group) who received 0.2% chlorhexidine. The rinse regimen began on the 15th day and continued for 7 days. Plaque accumulation was assessed by Plaque Index (PI) and gingivitis was assessed by Modified Gingival Index (MGI) and Bleeding Index (BI) at baseline (0), 7th, 14th, and 22nd days.

Results:

There was statistically significant decrease in PI, MGI, and BI scores after the rinse regimen began in both Group A (test group) and Group C (chlorhexidine) compared with Group B. Mouth wash containing Aloe vera showed significant reduction of plaque and gingivitis but when compared with chlorhexidine the effect was less significant.

Conclusion:

Aloe vera mouthwash can be an effective antiplaque agent and with appropriate refinements in taste and shelf life can be an affordable herbal substitute for chlorhexidine.

Keywords: Aloe vera, chlorhexidine, gingivitis, plaque, plaque guard

INTRODUCTION

Plaque control and prevention of gingivitis is the main goal of prevention of periodontal diseases.[1] Complete plaque removal is difficult to achieve, and prevention of periodontal disease can be enhanced either by reducing the quantity of plaque below the individual's threshold for disease or changing the quality of plaque to a more tissue-friendly composition.

For effective plaque control, several mechanical oral hygiene aids as well as a number of antiplaque agents such as chlorhexidine, essential oil containing mouthrinses, and triclosan are available. Chlorhexidine has shown distinct advantage and efficacy, but side effects such as staining of the teeth and the tongue, altered taste sensation, and increased calculus formation often deters its use for long periods.

Hence, there is a need to develop a naturally occurring, indigenous and cost-effective oral hygiene aid. One such aid could be in the form of Aloe vera extract. Aloe vera is a cactus-like plant, which is a member of the Lilaceae family. Aloe vera has anti-inflammatory properties,[2–4] antiulcer activity,[5,6] astringent effect, and possibility of reducing scars and enhancing wound healing.[7–10] The above properties along with the ease of availability, with no known adverse effects and cost-effectiveness, make Aloe vera an ideal candidate for plaque control and thereby reduce gingivitis and probably later periodontitis.

Studies evaluating the effectiveness of Aloe vera incorporated in a dentifrice or as a locally applied gel showed a significant reduction of gingivitis and plaque accumulation after the use of this natural product.[11–13]

The purpose of this study was to assess the antiplaque and antigingivitis effect of Aloe vera in an “experimental gingivitis” model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

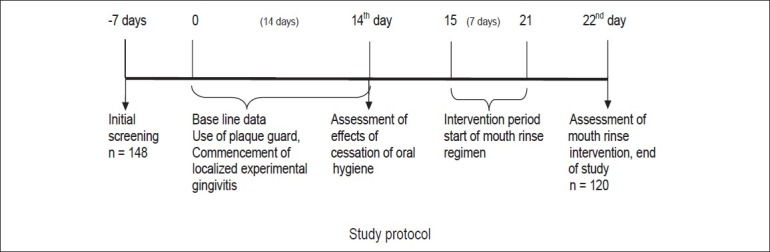

A total of 148 healthy subjects (68 males and 80 females), aged 18-25 years, were selected from the student volunteers of Sri Sai College of Dental Surgery, Vikarabad, Andhra Pradesh, India [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Experimental design

Permission was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the college, and informed written consent was obtained from the volunteers after explaining the methodology of the clinical trial.

Inclusion criteria involved at least one maxillary quadrant having both premolars and molars, free from restorations on palatal, buccal, and proximal surfaces and subjects with good oral hygiene.

Exclusion criteria involved probing depths greater than 3 mm, teeth with gross carious lesions, subjects undergoing orthodontic treatment, those with removable and fixed prosthesis, teeth involved by severe fluorosis, and those who received any topical or systemic antibiotic treatment during the past 3 months prior to the study. Subjects with a history of systemic diseases and smokers were also excluded from the study.

The experimental area selected for the study comprised the first and second premolars and molar teeth in one quadrant of the maxilla. To maintain the uniformity, maxillary right area was selected, unless contraindicated. The third molars were excluded from the study.

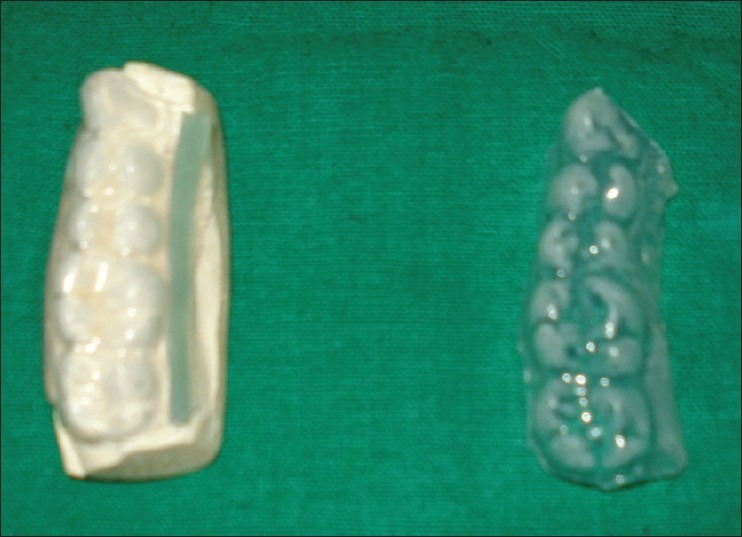

A special plaque guard was fabricated to include the experimental teeth and their gingival margin, as described by Rosen.[14] The plaque guard prevented plaque removal from the experimental teeth and facilitated localized plaque accumulation and the resultant gingivitis if any [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Plaque guard

The antimicrobial efficacy of Aloe vera was evaluated in a preliminary in vitro study exposing supragingival plaque samples to different concentrations of Aloe vera. The zone of bacterial inhibition around a bored well containing test (Aloe vera), placebo (distilled water), and positive control (chlorhexidine) was the main criteria to indicate antibacterial properties. Aloe vera at 100% concentration was found to have maximum effect in vitro.

One week prior to the start of the study, all participants were subjected to professional cleaning and instructed to continue their regular oral hygiene. At the end of 7 days out of the total 148 volunteers, 28 volunteers dropped out from the study for various reasons. The remaining 120 student volunteers (58 males and 62 females) were randomly assigned to three groups on day 0, that is, baseline. Each group consisted of 40 subjects and were divided as follows:

Group A: Test group who received 100% Aloe vera

Group B: Negative control group who received placebo (distilled water)

Group C: Positive control group who received 0.2% chlorhexidine.

Induction phase

All subjects were instructed to wear the plaque guards every time they cleaned their teeth, so that brushing was not performed on the premolars and molars of the test quadrant. This phase, called the induction phase, lasted for 14 days.

The subjects belonging to all the three groups (A, B, and C) were recalled to assess the difference of plaque accumulation between the experimental and non experimental areas on 14th day [Figures 3 and 4].

Figure 3.

Group A: Experimental area on 14th day

Figure 4.

Group C: Experimental area on 14th day

Plaque index (PI) (Quigley and Hein modified by Turesky)[15] to assess the plaque accumulation, modified gingival index (MGI) (Lobene),[16] and bleeding index (BI) (Saxton)[17] to assess gingivitis were used at the 7th and the 14th day.

Intervention phase

The rinse regimen began from the morning of day 15 and lasted for 7 days. The subjects were allocated to use either the Aloe vera mouthrinse or the positive control or the negative control placebo according to a randomization list. The three mouthrinses were dispensed in identical bottles.

150 ml of rinse solution was given to each subject who was not aware of what type of rinse he/she was receiving. Along with each bottle of rinse, a 10 ml measure was given to facilitate correct dosage. The subjects were asked to rinse with 10 ml of the solution for 1 min, twice daily, once in the morning, and once before going to bed. Intake of food and/or drinks was not allowed for 2 h after rinsing.

The subjects belonging to all the three groups (A, B, and C) were recalled for evaluation of plaque reduction once the rinse regimen was completed on 22nd day [Figures 5 and 6]. PI, MGI, and BI were assessed on 22nd day. To ensure total compliance with rinsing protocol, the subjects were advised to bring back their bottles to record the remaining rinse solution. All the subjects complied with the rinsing instructions and there were no departures from either the frequency of rinsing or the volume used for rinsing.

Figure 5.

Group A: Experimental area on 22nd day

Figure 6.

Group C: Experimental area on 22nd day

Signs or symptoms of adverse reactions on the oral mucosa and any deterioration in the health status of the study subjects were documented and analyzed. At the end of the trial period, subjects received thorough professional tooth cleaning before finally being taken off from the study.

Statistical analysis

Student's paired t-test was used for the intragroup analysis of Groups A, B, and C for PI, MGI, and BI, and a one-way ANOVA test was used for the intergroup analysis between Groups A-B, A-C, and B-C for PI, MGI, and BI. The results are presented as mean and standard deviation. The level of statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

RESULTS

This study was carried out to find the antiplaque and antigingivitis effect of Aloe vera and compare it with that of chlorhexidine mouth wash. While chlorhexidine served as a positive control, a placebo without any known antiplaque properties served as a negative control. A total of 148 student volunteers were recruited, out of which 120 volunteers participated in the study at baseline (0 day).

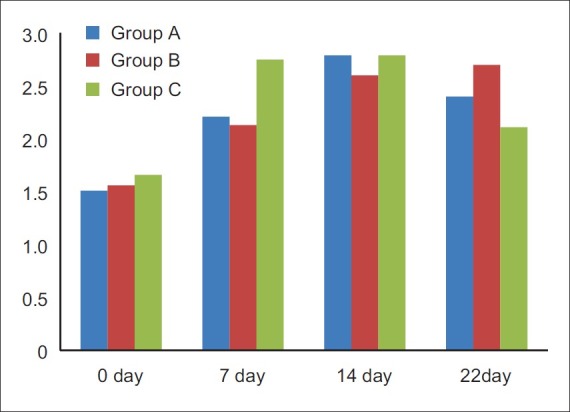

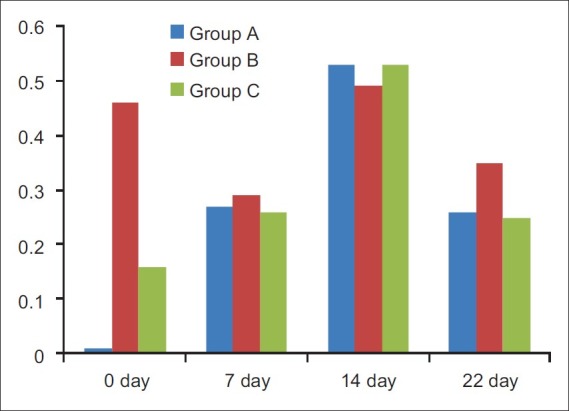

Plaque index

There was a significant increase in plaque accumulation in all the three groups from day 0 to day 14. Subsequent to introduction of mouthrinse program for 1 week, there was a significant plaque reduction on 22nd day, in both Group A (Aloe vera) and Group C (chlorhexidine) when compared with Group B and the plaque reduction in Group C was more significant compared with that of Group A [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Comparison of mean Plaque index scores mean Plaque index

The mean difference was statistically significant when Group A and C were compared with Group B and the mean difference was also statistically significant between Group C and A [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of intergroup mean difference related to Plaque Index scores

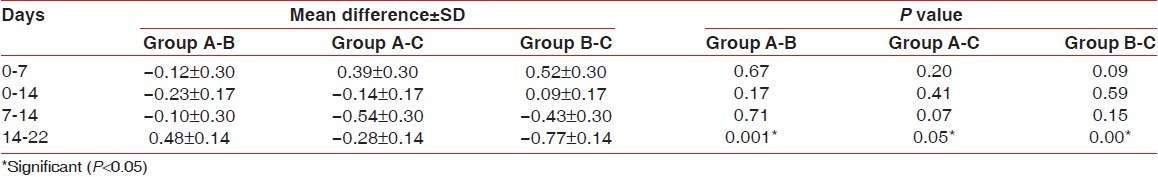

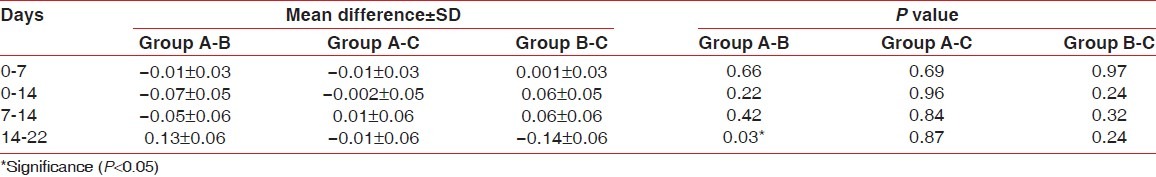

Modified gingival index

MGI scores of all the three groups from day 0 to day 14 have increased gradually. With introduction of respective mouthrinses, the gingival index came down after 7 days which is statistically significant in all the three groups [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Comparison of mean modified gingival index scores

Comparing the three groups, Group C has shown more significant reduction in the gingival index scores than Group A and Group B. Similarly, Group A score had significant difference over Group B [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of intergroup mean difference related to modified Gingival Index scores

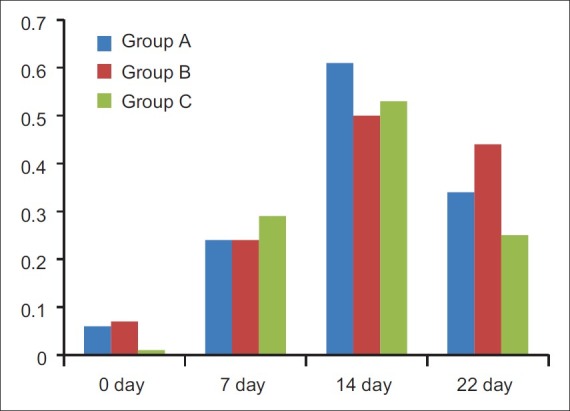

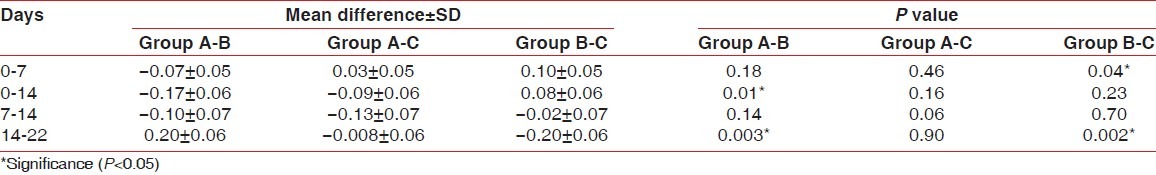

Bleeding index

BI scores of all the three groups from day 0 to day 14 have increased gradually. With introduction of respective mouthrinses, the BI scores have shown reduction after 7 days in Group A and Group C and this difference was statistically significant. Distilled water treated (placebo group) did not show any effect on bleeding scores [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

Comparison of mean BI scores

Comparing the three groups, Group C has shown more significant reduction in the mean BI score than Group A and Group B. Similarly, Group A score had significant difference over Group B [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of intergroup mean difference related to Bleeding Index scores

DISCUSSION

This study can be considered really complying with all the requirements of an ideal mouthrinse protocol as specified by Barnett.[18] Additional inclusion of a positive control enhances the quality of the study protocol. All the three groups when using a plaque guard and at the end of its use continued to accumulate plaque and this was statistically significant. Plaque accumulation in experimental subjects with cessation of oral hygiene (tooth brushing) is an established method in gingivitis and oral hygiene product evaluation.

This study was intended not only to study plaque accumulation but also its effect in eliciting gingival tissue response. Hence, a total period of 14 days of oral hygiene cessation was permitted before the soft tissue status could be recorded. This was in accordance with the studies by Lorenz et al.[19] on chlorhexidine and Ramberg et al.[20] on triclosan. All these studies emulate the classic and pioneering work of Loe and Schiot.[21]

This study, however, differed from the above studies in that the subjects instead of total abstinence from oral hygiene only abstained from brushing in few selected teeth area. To abstain from total oral hygiene from 14 days is inconvenient. To overcome such limitations, Rosen et al.[14] introduced an ingenious method in the form of a plaque guard. This study has drawn inspiration from Rosen's study and most of the subjects did not complain either about abstinence from oral hygiene or any discomfort from wearing the appliance.

Aloe vera possesses various beneficial properties such as anti-inflammatory[2–4] (due to the presence of sterols and anthraquinones), antiseptic activity[5,6] (due to the presence of lupeol, salicylic acid, phenols, sulphur), and also has the capability to enhance wound healing.[7–10] Aloe vera inhibits the cyclooxygenase pathway and reduces prostaglandin synthesis form arachidonic acid, thus reducing inflammation. Hence, the reduction in gingival index scores can be attributed to components of Aloe vera which have anti-inflammatory properties.

The antimicrobial effect of Aloe vera has been demonstrated in an in vitro study by Lee et al.,[22] wherein it was reported to inhibit the growth of diverse oral microorganisms such as Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sanguis, Actinomyces viscosus, and Candida albicans. The low plaque scores at the conclusion of the study could be attributed to the antibacterial properties of Aloe vera.

Both test and positive control groups showed reduction in plaque scores significantly, whereas placebo did not show any reduction; in fact plaque scores were increased. It indicates the ability of Aloe vera and chlorhexidine in plaque reduction as significant, but the level of significance is more with chlorhexidine usage. It nonetheless indicates that Aloe vera can also effectively reduce experimentally induced plaque accumulation.

Comparing the three groups in their ability to reduce gingival scores, it is observed that Aloe vera reduced gingival score, placebo also reduced gingival score, but the difference in mean reduction was more with the use of Aloe vera than placebo. The reduction of gingival score by Aloe vera and chlorhexidine is comparable and not significant. The use of chlorhexidine and placebo did reduce gingival scores and this reduction was not appreciable or significant in favor of chlorhexidine.

All the three groups showed reduced gingival scores irrespective of whether they are on Aloe vera, chlorhexidine, or placebo, but there are levels of difference which are difficult to interpret and probably needs a finer calibration. Aloe vera group showed statistically significant difference in gingival bleeding scores compared with placebo groups. Chlorhexidine use reduced gingival bleeding scores but such reductions in bleeding scores when compared with Aloe vera are not significant.

A recapitulation of the effect of three interventions indicates that Aloe vera and chlorhexidine had a definitive impact on plaque reduction but showed unpredictable and variable effect on gingivitis and gingival bleeding, with even patients on placebo showing marginal improvement instead of deterioration. This once again stresses the view point that plaque control is essentially a mechanical oriented (tooth brushing) method and use of mouth wash, however, effective, is only an adjunct in oral hygiene regimen.

Highlights and limitations of the study

The cessation from regular oral hygiene is an inconvenient and embarrassing prerequisite in any mouthrinse study. This has been offset by the use of a plaque guard. The idea of using a plaque guard as introduced by Rosen et al. and implemented in this study could be a useful tool in future mouthrinse trials.

This study was conducted on student volunteers who are cohesive, well educated, and sensitized subjects to oral hygiene. The compliance and adherence to treatment protocols are thoroughly understood by them and such follow-up cannot be translated to patients belonging to common strata of society.

The substantivity of Aloe vera mouthrinse is to be established by in vitro microbiological tests before it's frequency of use can be established.

CONCLUSION

Aloe vera when used at full strength reduced accumulated plaque significantly. Within the limits of the clinical study, it may be concluded that the mouth wash containing Aloe vera showed significant reduction of plaque and gingivitis, but when compared with chlorhexidine, this was less significant.

Researchers are becoming interested in alternative therapies of plaque control using natural products as opposed to synthetic agents. Within the limitations of this study, Aloe vera did have an antiplaque and antigingivitis effect. If the potential benefit is confirmed through long-term studies, Aloe vera could be an alternative to chlorhexidine from its numero Uno position and could be valuable in patients who are seeking a chemical-free, indigenous, and patient-friendly oral hygiene aid.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Christine DW, Eugene DS. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of over the counter oral hygiene products for the reduction and control of plaque and gingivitis. Periodontol 2000. 2002;28:91–105. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.280105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis RH, Rosenthal KY, Cesario LR, Rouw GA. Processed Aloe vera administered topically inhibits inflammation. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1989;79:395–7. doi: 10.7547/87507315-79-8-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis RH, Leitner MG, Russo JM, Byrne ME. Anti-inflammatory activity of Aloe vera against a spectrum of irritants. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1989;79:263–76. doi: 10.7547/87507315-79-6-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vázquez B, Avila G, Segura D, Escalante B. Anti-inflammatory activity of extracts from Aloe vera gel. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;55:69–75. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(96)01476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imanishi K, Aloctin A. Active substance of Aloe arborescens Miller as an immunomodulator. Phytother Res. 1993;7:20–2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saito K, Hiroko A. Purification of active substances of Aloe Arborescens Miller and their biological and pharmacological activity. Phytother Res. 1993;7:14–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis RH, Leitner MG, Russo JM, Byrne ME. Wound healing: Oral and topical activity of Aloe vera. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1989;79:559–62. doi: 10.7547/87507315-79-11-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis RH, Donato JJ, Hartman GM, Haas RC. Anti-Inflammatory and wound healing activity of a growth substance in Aloe vera. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 1994;84:77–81. doi: 10.7547/87507315-84-2-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maenthaisong R, Chaiyakunapruk N, Niruntraporn S, Kongkaew C. The efficacy of Aloe vera used for burn wound healing: A systematic review. Burns. 2007;33:713–8. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.10.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chithra P, Sajithlal GB, Chandrakasan G. Influence of Aloe vera on the healing of dermal wounds in diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 1998;59:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(97)00124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pradeep AR, Agarwal E, Naik SB. Clinical and Microbiological Effects of Commercially Available Dentrifice Containing Aloe vera: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J Periodontol. 2011 doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110371. (Ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhat G, Kudva P, Dodwad V. Aloe vera: Nature's soothing healer to periodontal disease. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:205–9. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.85661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Oliveira SM, Torres TC, Pereira SL, Mota OM, Carlos MX. Effect of a dentifrice containing Aloe vera on plaque and gingivitis control. A double-blind clinical study in humans. J Appl Oral Sci. 2008;16:293–6. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572008000400012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen M, Kahler ST, Hessler M, Kuhr A, Kocher T. The effect of a dexibuprofen mouth rinse on experimental gingivitis in humans. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:617–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turesky S, Gilmore ND, Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of victamine C. J Periodontol. 1970;41:41–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.41.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lobene RR, Weatherford T, Ross NM, Lamm RA, Menaker L. A modified gingival index for use in clinical trials. Clin Prev Dent. 1986;8:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saxton CA, Vander Ouderaa FJ. The effect of a dentifrice containing zinc citrate and triclosan on developing gingivitis. J Periodontal Res. 1989;24:75–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1989.tb00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnett ML. The role of therapeutic antimicrobial mouth rinses in clinical practice: Control of supra gingival plaque and gingivitis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:699–704. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorenz K, Bruhn G, Heumann C, Netuschil L, Brecx M, Hoffmann T. Effect of two new chlorhexidine mouth rinses on the development of dental plaque, gingivitis, and discoloration. A randomized, investigator-blind, placebo-controlled, 3 week experimental gingivitis study. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:561–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramberg P, Furuichi Y, Sherl D, Volpe AR, Nabi N, Gaffar A, et al. The effect of triclosan on developing gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:442–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loe H, Schiott CR. The effect of mouthrinses and topical application of chlorhexidine on the development of dental plaque and gingivitis in man. J Periodontal Res. 1970;5:79–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1970.tb00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SS, Zhang W, Li Y. The antimicrobial potential of 14 natural herbal dentifrices: Results of an in vitro diffusion method study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:1133–41. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]