Abstract

The investigation of disease-related oxidant-antioxidant imbalance is difficult due to the limited availability of specific biomarkers of oxidative stress, and the fact that measurement of individual antioxidant may give misleading picture because antioxidants work in concert through chain breaking reactions. Therefore, analysis of total antioxidant capacity may be the most relevant investigation. As the total blood is continuously exposed to oxidative stress, the aim of the current study was to investigate total blood antioxidant capacity in healthy and periodontitis patients by using novel Nitroblue Tetrazolium reduction test. The study was conducted on 30 non-smoking volunteers with age ranging between 18-40 years. They were categorized into two groups; chronic periodontitis group and healthy group, respectively. Total antioxidant capacity in whole blood was assessed using Nitroblue Tetrazolium reduction test. Results of the present study has shown that the total antioxidant capacity in whole blood in patients with periodontitis was significantly (P<0.005) lower than in control subjects. The reduced total blood antioxidant status in periodontitis subjects warrants further investigation as it may provide a mechanistic link between periodontal disease and several other free radical-associated chronic inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Nitroblue tetrazolium reduction test, oxidative stress, total antioxidant capacity

INTRODUCTION

Oxidative stress is a state of altered physiological equilibrium within a cell or tissue/organ, defined as “A condition arising when there is a serious imbalance between the levels of free radicals in a cell and its antioxidant defenses in favor of the former”.[1] It is estimated that 1–3 billion reactive species are generated/cell/day, and given this, the importance of the body's antioxidant defense systems to the maintenance of health becomes clear.[2]

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) not only play an important role in cell signaling and metabolic processes, but are also thought to be implicated in the pathogenesis of a variety of inflammatory disorders.[3] Chronic periodontitis (CP) is initiated by the sub-gingival biofilm, but the progression of destructive disease appears to be dependent upon an abnormal host response to those organisms. It also characterized by hyperinflammatory response involving excess oxygen radical release by neutrophilic polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Excess release of proteolytic enzymes such as neutrophil elastase.[4]

Oxidative stress is implicated in the pathogenesis of several chronic inflammatory diseases associated with periodontitis, such as type-2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, vascular disease, including stroke and chronic inflammatory lung disease.[3]

The investigation of disease-related oxidant–antioxidant imbalance is problematic due to the limited availability of specific biomarkers of oxidative stress and the fact that measurement of individual antioxidants may give a misleading picture because antioxidants work in concert through chain-breaking reactions. Therefore, analysis of total antioxidant capacity (TAOC) may be the most relevant initial investigation.[5]

It is a well established fact that whole blood is continuously exposed to oxidative stress reduced oxygen species generated by the oxidation-reduction of drugs or xenobiotics transported by blood and metabolism in various tissues and organs, which release ROS into blood.[6] So the aim of the study was to compare and evaluate the whole blood TAOC in periodontitis patients and in healthy subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study included 30 patients (16 male and 14 female) reported to Department of Periodontics, M.S. Ramaiah Dental College Bangalore, with age ranging between 18-40 years. They were divided into two groups with 15 patients in each healthy (control) and periodontitis (experimental) groups, respectively. Healthy group: 15 subjects with healthy periodontal conditions. Periodontitis group: 15 subjects with clinically diagnosed periodontitis having presence of at least 2 non-adjacent sites per quadrant with probing pocket depths ≥5 mm which bled upon gentle probing and patients who had not undergone any periodontal treatment for at least 6 months prior to sampling were included in the study. While subjects with history of antibiotic or anti inflammatory drug therapy in last 3 months, history of any systemic disease, subjects who are pregnant and pre eclamptic, smoker and tobacco chewer, subjects with vitamin supplements, subjects who regularly use mouth washes were excluded.

Blood samples were obtained in morning following an overnight fast. Two ml of venous blood was collected in heparinized test tube (lithium heparin, 15 units/ml). In this study, we have used the Novel method – where Reduction of Nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) was measured in the whole blood of patients with periodontitis, and persons with healthy periodontal tissues without systemic disorders.

Total antioxidant capacity assay: NBT reduction test

The reduction of NBT was measured in the whole blood according to a previously described procedure with modifications.[7] Two ml of peripheral venous blood were taken in the morning before meals. Blood clotting was controlled with heparin (15 units/ml). Then the test tubes with blood were placed in a thermostat at the temperature of 37°C and kept for 5 min. Next, NBT, the final concentration of which ranged to 1×10-4, was added to the blood in the test tubes, which were kept for 20 min at the temperature of 37°C. On completion of incubation, the tubes were centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 rpm to sediment any cells. The supernatant was decanted into fresh test tubes and the absorbance of NBT was measured in the samples using a spectrophotometer at wave length of 580 nm at 37°C against a blank.[5]

All the experiments were repeated three or more times. The data were expressed as the mean±SE if normally distributed and statistical significance of the differences was determined using Student's t test.

RESULTS

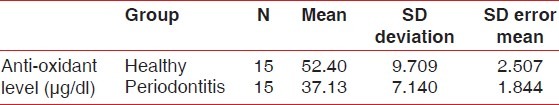

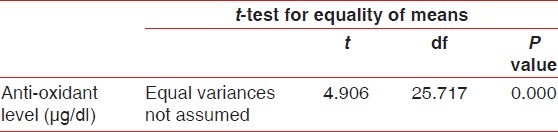

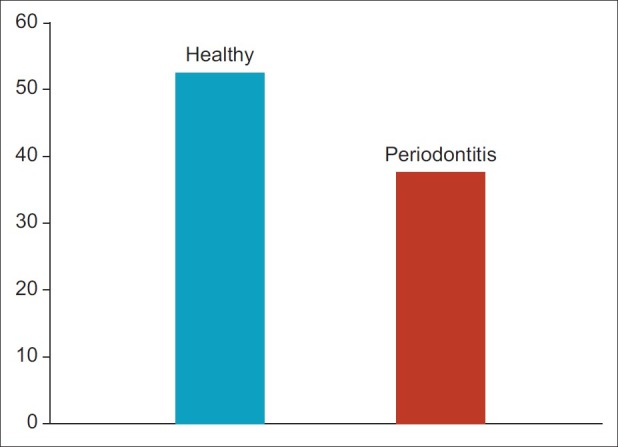

The group statistics [Table 1] showed a mean of antioxidant level 52.40 μg/ml for healthy group and 37.13 in μg/ml for experimental group in whole blood. The student ‘t’ test [Table 2 and Figure 1] was used for statistical analysis with 95% of confidence interval which showed that total antioxidant capacity (TAOC) was significantly decreased in blood of periodontitis group patients when compared with healthy group (P<0.001).

Table 1.

Group statistics

Table 2.

Independent samples test

Figure 1.

Anti-oxidant level between healthy and periodontitis group

DISCUSSION

Periodontal disease occurs in predisposed individuals with an aberrant inflammatory and immune response to microbial plaque. Neutrophils are the predominant inflammatory cells in gingival tissues. Sites with periodontitis are associated with increased levels of a variety of cytokines and chemokines produced by inflammatory cells and normal resident cell population with in periodontal tissues. A variety of pro inflammatory cytokines [TNF ALPLA, IL-8, IL-1, IL- 6], growth factors, and lipopolysaccharides have a priming effect on human neutrophil oxidative burst. ROS generation in periodontal disease causes bone resorption, degrade connective tissue, increases matrix metalloproteinases activity causing an imbalance.[8] Traditionally, ROS production by phagocytes has been associated with the defense of body to infection as they are essential for efficient killing of microbes. By contrast, ROS generation at high levels can cause oxidative stress within tissues and result in direct damage to cells and extracellular matrix. Products of this oxidative damage such as advanced glycation end products and lipid peroxide proteins can lead to further ROS induced damage by their priming and chemotactic effect on neutrophils.[3]

Currently, there are no gold standard methods for measuring antioxidant capacity or ROS-mediated tissue damage in humans. All the systems utilize different measurement indices and the specificity of the biomarkers employed dictate the measurement obtained, which differs between assays and between different biological samples and their components.[3] Free radicals and other reactive species have extremely short half-lives in vivo (10-6-10-9s) and simply cannot be measured directly. The majorities of clinical studies employ biomarkers of oxidative stress or tissue damage to vital macromolecules, rather than spin traps.[9]

The main sources of biomarkers of ROS activity are lipid peroxidation, protein/amino acid oxidation, carbohydrate damage, and DNA damage. All the assays for these biomarkers are intricate[7] suggesting a rather simple method for assessment of whole blood TAOC – the reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium test. Our study using this test has shown that whole blood TAOC in patients with periodontitis was significantly lower (P<0.005) than in the healthy controls.

In medicobiological literature, only one study was assigned for whole blood TAOC in periodontitis patients which showed total antioxidant capacity significantly lower in periodontitis patients.[5] In the current study, we have also found significantly lowered whole blood TAOC in periodontitis patients when compared with periodontally healthy subjects, which is in accordance with the previous study.

All the published studies have suggested that patients with chronic periodontitis have higher levels of lipid peroxidation than periodontally healthy control.[10]

Only three studies were assigned for total antioxidant capacity of serum/plasma taken from periodontitis patients showed a significantly lower total antioxidant capacity of the serum and plasma samples taken from the periodontitis subjects found that the reduced serum total antioxidant capacity in periodontitis did not completely reach significance.[11]

Guarnieri et al. demonstrated spontaneous generation of superoxide in the gingival crevicular fluid of periodontitis subjects, but found no differences in antioxidant scavenging capacity between cases and controls.[12]

Brock et al. demonstrated a significantly lower total antioxidant capacity in periodontitis subjects relative to age- and sex-matched controls. Gingival crevicular fluid total antioxidant capacity was significantly greater than in paired serum and plasma samples in healthy subjects, but this difference was not seen in periodontitis subjects.[11]

Data on salivary total antioxidant capacity are conflicting. Moore et al. were the first to explore salivary total capacity and concentration and found no differences between cases and controls.[13]

CONCLUSION

This study concluded that whole blood total antioxidant capacity in patients with periodontitis was significantly lower (P<0.05) than in healthy controls.

Whether this reduced antioxidant defense reflects inherent deficiencies predisposing to periodontitis or a result from the inflammatory lesion remains unclear. Finally, the reduced total blood antioxidant status in periodontitis subjects warrants further investigation as it may provide a mechanistic link between periodontal disease and several other free radical-associated chronic inflammatory diseases.

Clinical implications

This possible mechanisms leading to periodontal destruction provides opportunities to develop novel antioxidant therapies that target the free radicals and which function not only as antioxidants in the traditional sense but also as powerful anti-inflammatory agents.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM. Role of free radicals and catalytic metal ions in human disease: An overview. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:1–85. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86093-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagan TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7915–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapple IL, Matthews JB. The role of reactive oxygen and antioxidant species in periodontal tissue destruction. Periodontol 2000. 2007;43:160–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2006.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asman B, Gustafsson A, Bergstrom K. Gingival crevicular neutrophils: membrane molecules do not distinguish between periodontitis and gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;27:185–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zilinskas J, Zekonis J, Zekonis G, Valantiejiene A, Periokaite R. The reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium by total blood in periodontitis patients and the aged. Stomatologija. 2007;9:105–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gutteridge JM, Halliwell B. Free radicals and antioxidants in the year 2000.A historical look to the future. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;899:136–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demehin AA, Abugo OO, Rifkind JM. The reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium by red blood cells: a measure of Red Cell membrane antioxidant capacity and hemoglobin-membrane binding sites. Free Radic Res. 2001;34:605–20. doi: 10.1080/10715760100300501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyasaki KT. The Neutrophil: Mechanism of controlling periodontal bacteria. J Periodontal. 1991;62:761–74. doi: 10.1902/jop.1991.62.12.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halliwell B, Whiteman M. Measuring reactive species and oxidative damage in vivo and in cell culture: how should you do it and what do the results mean? Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:231–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panjamurthy K, Manoharan S, Ramachandran CR. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in patients with periodontitis. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2005;10:255–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brock GR, Matthews JB, Butterworth CJ, Chapple IL. Local and systemic antioxidant capacity in periodontitis health. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:515–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guarnieri C, Zucchelli G, Bernardi F, Csheda M, Valentini AF, Calandriello M. Enhanced superoxide production with no change of the antioxidant activity in gingival fluid of patients with chronic adult periodontitis. Free Radic Res Commun. 1991;15:11–6. doi: 10.3109/10715769109049120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore S, Calder KA, Miller NJ, Rice-Evans A. Antioxidant activity of saliva and periodontal disease. Free Radic Res. 1994;21:417–25. doi: 10.3109/10715769409056594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]