Abstract

Dental implants have evolved dramatically over the last decade, and so have our expectations from them in terms of functional and esthetic criteria. The maintenance and augmentation of the soft tissue has emerged as an area of concern and focus. The triad of anatomical peri-implant characteristics, soft tissue response to the implant material, and clinical skill form the fundamental principles in augmenting soft tissue. However, as clinicians, where are we with regards to the ability to augment and maintain soft tissue around dental implants, about 40 years after the first implants were placed? We now understand that peri-implant soft tissue management begins with extraction management. Our treatment modalities have evolved from socket compression post-extraction, to socket preservation with an aim to enhance the eventual peri-implant soft tissue. This short communication will assess the evolution of our thought regarding peri-implant soft tissue management, augmentation of keratinized mucosa around implants, and also look at some recent techniques including the rotated pedicle connective tissue graft for enhancing inter-implant papilla architecture. With newer research modalities, such as cyto-detachment technology, and cutting-edge bioengineering solutions (possibly a soft-tissue-implant construct) which might be available in the near future for enhancing soft tissue, we are certainly in an exciting era in dentistry.

Keywords: Dental implant, dental implantology, graft, grafting, tissue

INTRODUCTION

Dental implants have evolved dramatically over the last decade, and so have our expectations from them in terms of functional and esthetic criteria. At first dental implants were thought of as mere ‘anchors’ to enable a fixed prosthesis. But as dental implants evolved from the earlier blade types to the current root form types, the esthetic possibilities and demands from both clinicians and patients has changed. Thus, the maintenance and augmentation of the soft tissue around dental implants has emerged as an area of much concern and focus.

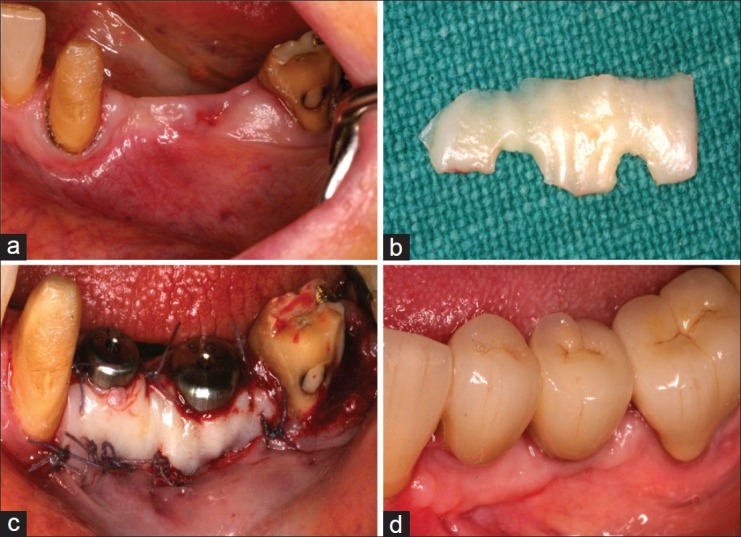

As more implants have been placed, clinicians have discovered the optimum treatments to get optimum esthetic results. Since this has been through trial and error process, we have unfortunately also been witness to instances where the overall cosmetic appearance has been greatly disturbed [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Improper implant placement and undeveloped soft tissue profile leads extremely unaesthetic results

And so the question for all of us as Periodontists is, “where are we with regards to our ability to augment and maintain soft tissues around dental implants?” given that we have had about 40 years of implant dentistry to solve this problem? This editorial examines the evolution of our thought regarding peri-implant soft tissue management and also looks at some new and emerging techniques available for augmenting peri-implant soft tissue.

The anatomic difference between peri-implant soft tissue and tooth soft tissue

Over the years, research has led us to a better understanding of the anatomical differences between the tooth-soft tissue and implant-soft tissue interface. The soft tissue profile and maintenance around implants is inherently more difficult than around teeth for a simple reason- the difference in vascular supply to support the soft tissues and the arrangement of fibers and fiber types around the implant. In the case of a natural tooth, the three main sources of blood supply are a) the supraperiosteal vessels which supply the free and attached gingiva b) blood vessels from the periodontal ligament and c) blood vessels from alveolar bone. In the case of implants, the important blood vessels from the periodontal ligament are missing. Also, there is a hypovascular- hypocellular connective tissue zone around the implant which is not seen around a natural tooth. The implanto-gingival junction of unloaded and loaded non-submerged titanium implants has been analyzed histometrically in the canine mandible.[1] The biologic width around implants has been found to be quite similar to that around teeth. This is an important factor that we have come to understand and incorporate in our treatment plan.

Also, we have come to understand that the existing periodontal tissue biotype plays an equally important role when Planning soft tissue augmentation. Olsson and Lindhe (1991)[2] subdivide periodontal tissue into

-

a)

Thin, scalloped

-

b)

Thick, flat periodontium.

Each periodontal biotype renders its own characteristic to the final surgical outcome. The astute clinician takes the periodontal biotype into consideration when choosing a certain treatment modality, since the thick periodontal biotype is typically more ‘forgiving’ of any surgical procedure compared to the thin biotype.

Soft tissue response to implants and abutments

The implant abutment-soft tissue interface has been the subject of research regarding its influence on the stability of the peri-implant tissues. More specifically, in the past 5 years, abutment materials such as zirconia have been postulated to function better than titanium abutments for helping to maintain the soft tissue profile. A recent systematic review[3] attempted to evaluate the available evidence for a difference in the stability of peri-implant tissues between titanium abutments versus gold alloy, zirconium oxide, or aluminum oxide abutments. These studies revealed that titanium abutments did not maintain a higher bone level in comparison to gold alloy, aluminum oxide, or zirconium oxide abutments. The authors of the study also concluded that there was a lack of information about the clinical performance of zirconium oxide and gold alloy abutments as compared to titanium abutments.

Our collaborative group comprising the University of California at Davis and the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston is currently looking at single cell cyto-detachment techniques in an attempt to quantify the adhesion characteristics of osteoblasts and fibroblasts to the implant surface. This might add value to the existing efforts with other research groups which are looking at ways to enhance the soft tissue attachment to the implant platform, paving the way for newer integrated implant-soft tissue constructs in the future.

Attached soft tissue around implant

There has been a lot of debate over the past decade whether there is a need for attached soft tissues around implants. Some researchers have demonstrated that attached soft tissues provide no statistical long term advantage over alveolar mucosa.[4,5] Others have correlated the presence of attached tissues with improved soft tissue health, prognosis and patient satisfaction.[6]

It is believed that the attached soft tissue resists disruption of the junctional epithelial seal, and thus adds to the long term prognosis. It has been postulated[7] that the progression of plaque-induced alveolar bone loss of osseointegrated implants may be different from that of teeth. This authors opinion is that the presence of attached tissue is better than not having any, and since extremely few patients can maintain a zero plaque level, the presence of the attached tissue adds a ‘layer of protection’ to resist the deteriorating effects of plaque accumulation, and to withstand the mechanical insult that the peri-implant soft tissue undergo each day [Figure 2a–d]. A recent study[7] which assessed the association between keratinized mucosa width and mucosal thickness with clinical and immunological parameters around dental implants seems to corroborate this view. In that study, a thick mucosa (≥1 mm) was seen to be associated with lesser recession around the implant.

Figure 2.

(a) Mandibular site demonstrating inadequate keratinized mucosa, planned for implant restoration; (b) Implant placement followed by free gingival graft harvest from palate. FGG contoured to fit around implants and sutured in place using 5/0 vicryl sutures; (c) Post-op healing at 2 months, demonstrating good band of keratinized tissue around both implants; (d) Also note about 20% graft shrinkage at the distal implant, highlighting the need to over-augment

Augmenting keratinized mucosa around an implant, in my clinical experience, has been a fairly predictable procedure; with good long term results (from a follow-up of my patients over 3 years). The patients who had this procedure done were noted to have low plaque levels around the implants, and excellent tissue health after augmentation, in contrast to the baseline presentation.

Surgical techniques

Our thought process has evolved from simply augmenting tissue to a concept where preservation of tissue is given equal importance. We now understand that peri-implant soft tissue management starts at the time of tooth extraction, not following implant placement. We have thus moved away from the earlier concepts of socket compression following extraction. This fundamental change in our philosophy has been fueled by the appreciation of the fact that socket preservation (with an appropriate grafting material when indicated) and subsequent temporization (with an ovate pontic) done after tooth extraction plays an important role in preserving the existing soft tissue. Use of incision designs such as the papilla preservation flap further helps to preserve any existing tissue.

Choice of suture materials

Another advance in recent times has been the better understanding and use of suturing materials. It goes without saying that any suture which will be submerged beneath the flap needs to be resorbable, but this author's personal preference is for resorbable sutures even for the flap closure. Use of silk sutures is usually not recommended for soft tissue graft procedures, since silk sutures tend to have a ‘plaque wicking effect’, and often seem to show a mild inflammatory response during the initial healing process. The preferred suture type for soft tissue augmentation is a suture such as a 6/0 or a 5/0 Vicryl™ (Ethicon Inc.), although some clinicians prefer using 5/0 Chromic gut suture or polypropylene sutures as well. Similarly, the choice of the suture needle is as important.

A round body needle is often the preference for suturing the connective tissue graft, versus a reverse cutting needle, since the round body needle tends to maintain the soft tissue integrity better. In a surgery as technique-sensitive as peri-implant soft tissue grafting, the choice of suture materials, appropriate suturing techniques (such as vertical mattress for maintaining coronal papilla level) and the appropriate instruments adds the final but important component to a successful outcome.

Since vascularity and structural support is a limiting factor in cases of two adjacent implants, as explained in the earlier part of this article, there are two fundamental considerations to preserving and augmenting soft tissue in between two implants:

-

a)

Position of two implants: As far as possible, it is advisable to not place two implants next to each other. We have learnt that the placement of the implants with a minimum distance of 3 mm between the platforms[8,9] leads to a better chance of maintaining papilla between them. For instance, in the case of missing four maxillary incisors, some clinicians promote the placement of implants in the lateral incisor sites, and cantilevering the central incisors, or joining them as a four unit bridge, versus placement of implants in the central incisor regions. The rationale for this approach is that the existing PDL and bone support on the mesial aspects of the adjacent teeth will help support the papilla in between the implant and tooth, while it would be easier to build soft tissue support beneath the pontic with no interference from any implants

-

b)

Augmenting soft tissue between two implants: Building the inter-implant papilla has proven to be a challenge, and various techniques such as insertion of a titanium papilla insert[10] have also been proposed and attempted with some success. Placement of a connective tissue graft is probably the most popular technique, however, the factors influencing the success of connective tissue augmentation are the distance between the two implants, distance from alveolar crest to contact point, periodontal tissue biotype, flap passivity prior to closure, suturing technique and post-operative maintenance.

To study the effect of soft tissue augmentation around implants,[11] 10 partially edentulous patients requiring at least one single implant in the premolar or molar areas of both sides of the mandible were randomized to have one side augmented at implant placement with a connective soft tissue graft harvested from the palate or no augmentation. After 3 months of submerged healing, abutments were placed and within 1 month definitive crowns were permanently cemented. Outcome measures evaluated by the authors were implant success, any complications, peri-implant marginal bone level changes, patient satisfaction and preference, thickness of the soft tissues and aesthetics. Soft tissues at augmented sites were 1.3 mm thicker (P < 0.001) and had a significantly better pink aesthetic score (P < 0.001). Patients were highly satisfied with both treatments, although they preferred the aesthetics of the augmented sites.

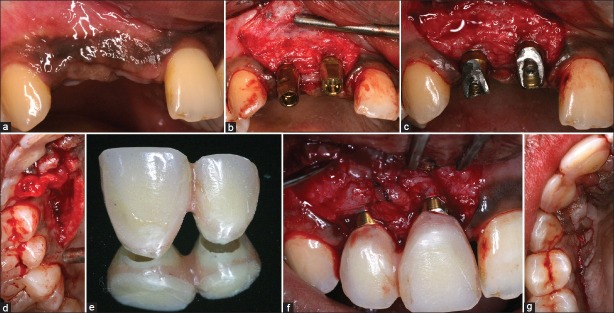

The two clear choices that exist when placing a connective tissue graft are either a ‘free’ connective tissue graft (unpedicled) or a pedicled connective tissue graft. The Vascularized Interpositional Connective tissue graft (VIP-CT) graft[6] has been used successfully for augmenting buccal or vertical soft tissue deficiency. This is primarily a rotated pedicle connective tissue graft which adds soft tissue volume and minimizes graft shrinkage, since it has a patent vascular supply [Figure 3a–g]. Over the past two years, I have used the VIP-CT graft with increased success; however, case selection remains a crucial factor. It is quite important to ensure that there is adequate thickness of palatal tissue with bone sounding, since a thin pedicle graft can often necrose and lead to compromised results.

Figure 3.

Soft tissue augmentation using vascularized interpositional connective tissue graft (VIP-CT) (a) Baseline presentation with submerged implants (b) Implant exposure with abutment placement (c) Initial rotation of connective tissue graft pedicle from palatal site as shown in (d), (e) temporary crown prior to placement (f) Seated temporary crowns with connective tissue pedicle interposed in between the two to create papilla (g) Palatal harvest site sutured. The connective tissue pedicle is tunneled below the sutured site to the buccal recipient site. Compare augmented site (f) with baseline (c) (Soft tissue surgery: Dr. Neel Bhatavadekar)

It is important to remember that since there is no augmentation in vertical interproximal bone height, the VIP-CT graft leads to mere augmentation of soft tissue volume, and the anticipation of possible tissue shrinkage implies that the patient needs to be informed about the risk of an uncertain result long term.

Thus, building the inter-implant papilla continues to be a challenge, with the VIP-CT graft being one of the possible treatment options.

Bioengineering

Lastly, and most recently, the ability to tissue engineer soft tissue where needed has led dentistry into a new research direction which is exciting and promising. Before long, we might be able to send a patient's gingival cells to a lab, and get in return a petri-dish of tissue engineered soft tissue for surgical transplantation. At the Academy of Osseointegration (AO) Summit meeting[12] in Chicago (August 2010), which I was invited to participate in, 75 clinicians and bioengineering experts discussed the translational applications of biological technologies such as micro-vibration, bone growth factors, and sustained release mechanisms to the enhancement of the implant-bone, and implant-soft tissue interface. The addition of bone growth factors to the implant surface is not a new concept, but the logistic and production challenges it poses, and the inability to maintain the growth factor on the surface after implantation, has been the main reason for the absence of such a product from the current implant market. Newer implant testing protocols such as cyto-detachment[13] have provided an option to test the individual cell attachments to implant surfaces, which has not been possible earlier. This, in turn, could lead to better ways to bioengineer dental implant surfaces.

The possibility of bioengineering an integrated implant-soft tissue construct was also discussed, which, in turn could be directly implanted into the recipient site which was devoid of the necessary soft tissue. Such an implant would theoretically have soft tissue bioengineered from the patient's own tissue attached to the coronal platform, and a conventional root form implant which would osseointegrate. The ability to sustain the vascularity for this soft tissue does remain an area of active research interest, and we will probably see a lot of new clinically applicable ideas emerging from this concept in the near future.

CONCLUSION

Our concepts about soft tissue management around implants have greatly evolved over the past two decades. We are in an exciting era where we have a better understanding of the conventional surgical techniques, and we also look to promising bioengineering approaches for the benefit of our patients. For instance, some procedures such as socket compression following extraction have become outdated, and newer concepts in socket preservation have emerged. The triad of anatomical peri-implant characteristics, soft tissue responses to the implant material, and clinical skill form the fundamental principles in augmenting soft tissue. Although long term follow-up and more randomized controlled trials are necessary to demonstrate long term prognosis of some of the recent techniques, researchers have provided us sound data to enable an evidence-based approach to treatment decisions as regards peri-implant soft tissue enhancement. These are exciting times!

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hermann JS, Buser D, Schenk RK, Higginbottom FL, Cochran DL. Biologic width around titanium implants. A physiologically formed and stable dimension over time. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2000;11:1–11. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2000.011001001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsson M, Lindhe J. Periodontal characteristics in individuals with varying form of the upper central incisors. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:78–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linkevicius T, Apse P. Influence of abutment material on stability of peri-implant tissues: A systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2008;23:449–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wennstrom G, Bengazi F, Lekholm U. The influence of the masticatory mucosa on peri-implant soft tissue conditions. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1994;5:1–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1994.050101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zarb G, Schmill A. The longitudinal clinical effectiveness of osseointegrated dental implants: The Toronto study. Part 3: Problems and complications encountered. J Prosthet Dent. 1990;64:185–94. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(90)90177-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sclar A. Soft tissue and esthetic considerations in implant therapy. Chicago: Quintessence Publishing Co; 2003. pp. 13–188. Ch. 2, 3, 6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zigdon H, Machtei EE. The dimensions of keratinized mucosa around implants affect clinical and immunological parameters. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008;19:387–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schou S, Holmstrup P, Hjørting-Hansen E, Lang NP. Plaque-induced marginal tissue reactions of osseointegrated oral implants: A review of the literature. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1992;3:149–61. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1992.030401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarnow DP, Cho SC, Wallace SS. The effect of inter-implant distance on the height of inter-implant bone crest. J Periodontol. 2000;71:546–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Salam el-Askary A. Use of a titanium papillary insert for the construction of interimplant papillae. Implant Dent. 2000;9:358–62. doi: 10.1097/00008505-200009040-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiesner G, Esposito M, Worthington H, Schlee M. Connective tissue grafts for thickening peri-implant tissues at implant placement. One-year results from an explanatory split-mouth randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2010;3:27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.AO Summit conference meeting 2010. Chicago, US: 2010. Impact of Biological and Technological Advances on Implant dentistry. [Last accessed on 2010 Oct 7]. Available from: http://www.osseo.org/events/summit.htm .

- 13.Bhatavadekar NB, Hu J, Keys K, Ofek G, Athanasiou KA. Novel application of Cytodetachment technology to implant surface analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2011;26:985–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]