Abstract

Objectives

To compare the effects of maintenance treatment with aripiprazole or placebo on the incidence of metabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder.

Methods

Patients with bipolar I disorder were stabilized on aripiprazole for 6–18 weeks prior to double-blind randomization to aripiprazole or placebo for 26 weeks. The rate of metabolic syndrome in each group was calculated at maintenance phase baseline (randomization) and endpoint for evaluable patients using an LOCF approach. Metabolic syndrome was defined using the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria.

Results

At entry into the maintenance phase, overall 45/125 patients (36.0%) met criteria for metabolic syndrome. Mean changes in the five components of metabolic syndrome (waist circumference, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, blood pressure and glucose) from baseline to Week 26 were small except for a meaningful reduction in triglycerides (placebo −18.9 mg/dL; aripiprazole −11.5 mg/dL). By the end of the maintenance phase (endpoint, LOCF), 5/18 placebo-treated patients (27.8%) and 4/14 aripiprazole-treated patients (28.6%) no longer met metabolic syndrome criteria. The proportion of patients with metabolic syndrome was similar in the placebo and aripiprazole groups both at baseline and Week 26. There were no significant changes in any of the individual components of metabolic syndrome between aripiprazole- and placebo-treated patients during maintenance phase treatment.

Conclusions

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder is higher than commonly reported in the general population. The effect of 26 weeks of treatment with aripiprazole on the incidence of metabolic syndrome and its components was similar to placebo.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, metabolic syndrome, cholesterol, obesity, triglycerides, blood pressure, maintenance trial

INTRODUCTION

Individuals with major mental disorders are at high risk of morbidity and mortality, with cardiovascular (CV) disease as a primary contributor 1. In fact, psychiatric inpatients and outpatients treated within the public sector die 25–30 years earlier than the general population 2. Clustering of CV risk factors such as abdominal obesity, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia and hypertension, is described as ‘metabolic syndrome’ (NCEP expert panel 3) and confers substantial CV risk above that of the simple arithmetic sum of the individual risk factors 4.

Recent literature shows a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder than expected for age- and gender-matched controls in the general population 5, 6. For example, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in 194 Spanish patients was 60% higher than controls, while a report from the Veterans’ Affairs System showed that 49% of patients met the criteria for metabolic syndrome 7. In both studies, low HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C), abdominal obesity and hypertriglyceridemia were particularly common. Indeed, obesity is more prevalent in bipolar disorder than the general population 6, 8, and is associated with a worse prognosis 9 and a history of attempted suicide 6. Patients with bipolar disorder frequently present with considerable additional medical burden (9), yet are less likely to receive adequate care for CV-related conditions 10, 11 and face substantial difficulties when accessing medical care 12. As a result, implementation of programs to reduce the incidence of metabolic syndrome is likely to be more difficult in patients with bipolar disorder than in the general population 6. Minimizing metabolic risks associated with psychotropic treatment in patients with bipolar disorder is, therefore, an important clinical priority.

Recently, there has been increasing interest in the use of atypical antipsychotics for bipolar disorder, but some atypicals increase CV risk factors while others may not 13, 14. In a recent study evaluating the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in 125 patients with bipolar disorder who had received at least 3 months’ treatment with atypical antipsychotics (quetiapine, risperidone or olanzapine), mood stabilizers or a combination of atypical antipsychotics and mood stabilizers, 32% of patients met NCEP ATP III criteria for metabolic syndrome 15. The rate of metabolic syndrome was significantly higher in patients receiving atypical antipsychotics alone, or in combination with mood stabilizers, compared with patients receiving mood stabilizers alone.

Furthermore, atypical antipsychotic use contributes to the increased prevalence of obesity among patients with bipolar disorder 6. Aripiprazole is pharmacologically distinct from other atypical antipsychotics 16, 17 and, thus, represents an agent with a low potential for weight gain, diabetes risk or a worsening lipid profile 18. Moreover, aripiprazole is not associated with significant changes in body weight or other metabolic parameters compared with placebo in patients with bipolar disorder 19–21. The safety and efficacy of aripiprazole for the treatment of bipolar disorder have been demonstrated in short- and longer-term studies 19, 21, 22. Recently, a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 26-week study showed that aripiprazole was superior to placebo in delaying the time to relapse of a mood episode and reducing the number of relapses in patients with bipolar I disorder with a recent manic or mixed episode 20.

To our knowledge, previous registration trials of atypical antipsychotics have not evaluated the incidence of metabolic syndrome during maintenance phase treatment of bipolar disorder. The present analysis is believed to be the first to estimate the rate of metabolic syndrome as well as its individual components over long-term use with any atypical antipsychotic monotherapy versus placebo. The objectives of the current analyses were to investigate further the prevalence (i.e. the number of cases in a population at a given time) and incidence (the number of new cases over time) of metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar I disorder and to test whether aripiprazole differentially affects the risk for developing metabolic syndrome and its individual component items over 26 weeks of maintenance treatment.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design

The current analysis to assess the prevalence and incidence of metabolic syndrome and its components uses data collected during a previously reported 26-week, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled aripiprazole study in patients with bipolar I disorder (Study CN138-010) 20.

After stabilization (Young Mania Rating Scale [YMRS] total score 10 and a Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total score ≤ 13 during four consecutive visits over a minimum of 6 weeks) with open-label aripiprazole (15 or 30 mg/day), patients were eligible for entry to the double-blind phase of the study. Patients were randomized (1:1) to receive either the aripiprazole dose they were taking at the end of stabilization or placebo for an initial 26-week treatment period, the results of which have been reported elsewhere 20.

All study sites received prior institutional review board/institutional ethics committee approval before study initiation and all patients provided written informed consent.

Patients

Participants met the criteria for bipolar I disorder according to the DSM-IV, with diagnoses performed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID) or the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). Details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria are available in the publication of the first 26-week double-blind phase 20. Briefly, patients were eligible for entry into the stabilization phase of the study if they had either recently completed a 3-week, placebo-controlled acute mania study of aripiprazole, if they met eligibility criteria for an acute mania study but had declined participation, or if they had experienced a manic or mixed episode requiring hospitalization and treatment within the previous 3 months. All psychotropic medications, except lorazepam and anticholinergic agents, were discontinued prior to enrolment.

Efficacy measures and analyses

The primary efficacy endpoint of the original study was the time to relapse for a mood episode (manic, depressive or mixed) during the initial 26-week double-blind treatment period 20 and the 74-week double-blind extension phase 23. Time to relapse was defined as discontinuation due to lack of efficacy.

The current analysis assessed the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and each of its components at maintenance phase baseline (randomization) and at Week 26 in evaluable patients who had metabolic measures for all five criteria for metabolic syndrome (last observation carried forward [LOCF] analysis). Patients who were rolled-over from a previous aripiprazole study did not have full results recorded across all metabolic syndrome criteria. Metabolic syndrome was defined according to the NCEP ATP III definition 24 as meeting at least three of the following five criteria: waist circumference >102 cm (men) or >88 cm (women); triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL; HDL-C <40 mg/dL (men) or <50 mg/dL (women); systolic blood pressure (BP) ≥130 mm Hg and diastolic BP ≥85 mm Hg; blood glucose ≥100 mg/dL. Blood samples for determination of serum triglycerides, HDL-C and blood glucose were collected from combined fasting and non-fasting patients. Supine systolic and diastolic measurements were used for the analysis. Waist circumference was measured at minimal respiration at the smallest circumference of the waist (the ‘natural’ waistline); data on waist circumference was not systematically collected after Week 26. Mean change in weight and body mass index (BMI) were also measured.

Dosing schedule

Study medication was administered orally, once daily, at approximately the same time each day. During the stabilization phase, patients received open-label treatment with aripiprazole at a starting dose of 30 mg/day. The dose could be decreased to 15 mg/day at any time, depending on tolerability. After entry to the double-blind phase of the study, patients were assigned, in a double-blind manner, to continue the dose of aripiprazole that they were taking at the end of the stabilization phase or to receive placebo. Based on the investigator’s assessment of therapeutic effect and tolerability, the dose of aripiprazole could be increased or decreased to either 30 mg/day or 15 mg/day at any time during the study

Statistical analysis

The effects of aripiprazole and placebo on the incidence of metabolic syndrome and its components were compared using Fisher’s Exact test on 2×2 frequency tables of metabolic syndrome absent/present, or component value normal/abnormal, as applicable. Mean change from baseline in the components of metabolic syndrome were evaluated using analysis of covariance with treatment as main effect and baseline component value as covariate. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Analyses were performed on LOCF data. For the determination of metabolic syndrome status, the last available observation for each of the five components was selected. Therefore, the five components used for evaluation may not necessarily have been measured at the same timepoint.

RESULTS

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

A total of 567 patients entered the stabilization phase of this study of whom 206 patients completed the stabilization phase and 161 entered the double-blind phase and were randomly assigned to placebo (n=83) or aripiprazole (either 15 or 30 mg) (n=78). In total, 67 patients completed the initial 26-week double-blind period. Details of patient disposition during stabilization and the initial 26-week double-blind phase of the study 20 have been described previously, as have the baseline characteristics of patients randomized to double-blind treatment 20. Demographic characteristics among the 125 patients who had metabolic syndrome criteria evaluable at maintenance phase baseline were similar between those patients in the placebo and aripiprazole groups: mean ± standard deviation (SD) age: 40.8 ± 10.7 vs. 38.2 ± 12.8 years; female: (73% vs. 66%). In the placebo group, 21% were experiencing a mixed state as the index episode and 79% were experiencing an index episode of mania, while in the aripiprazole group these values were 40% and 60%, respectively. The proportion of patients with rapid-cycling in the placebo group was 13% and in the aripiprazole group was 21%. The majority of patients in either group were white (placebo 63%; aripiprazole 64%). This analysis presents, for the first time, the baseline rates of metabolic syndrome and the five individual components of the metabolic syndrome among patients stabilized on aripiprazole monotherapy for 6–18 weeks. At maintenance phase baseline (randomization), metabolic syndrome was present in 38.8% of patients randomized to placebo and 32.8% of patients assigned to aripiprazole, giving an overall prevalence of 36.0%. Examination of the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among the sub-group of patients who did not have prior aripiprazole exposure, i.e. de novo patients (n=59), showed no difference to the population of ‘rollover’ patients with prior aripiprazole use (n=51) (MS rate: de novo [n=22/59] 37.3%; ‘rollover’ from prior aripiprazole use [n=19/51] 37.3%). Also, at maintenance phase baseline, the mean (SD) levels of glucose, triglycerides, HDL-C, blood pressure and waist circumference were similar in the patients randomized to placebo and those assigned to the aripiprazole group. The average values were generally at or above the threshold for abnormal values. Patients in both groups had a mean duration of prior aripiprazole exposure of approximately 14 weeks (Table 1).

Table 1.

Metabolic parameters at maintenance phase baseline

| Parameter | Placebo (n=67) | Aripiprazole (n=58) |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic syndrome present, n (%) | 26 (38.8%) | 19 (32.8%) |

| Metabolic syndrome absent, n (%) | 41 (61.2%) | 39 (67.2%) |

| Duration of prior aripiprazole, days mean (SD) | 96.3 (31.3) | 101.0 (43.4) |

| Combined fasting and non-fasting glucose, mg/dL mean (SD) | 95.2 (29.6) | 91.1 (18.6) |

| Combined fasting and non-fasting triglycerides, mg/dL mean (SD) | 158.5 (133.4) | 152.1 (98.8) |

| Combined fasting and non-fasting HDL-C mg/dL mean (SD) | 52.9 (20.4) | 47.0 (14.0) |

| Supine systolic BP, mmHg mean (SD) | 117.3 (13.0) | 118.6 (12.4) |

| Supine diastolic BP, mmHg mean (SD) | 74.3 (9.3) | 73.4 (9.3) |

| Waist circumference, cm mean (SD) | 98.2 (20.0) | 101.4 (17.0) |

SD = standard deviation; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; BP = blood pressure

Mean change from baseline in components of metabolic syndrome

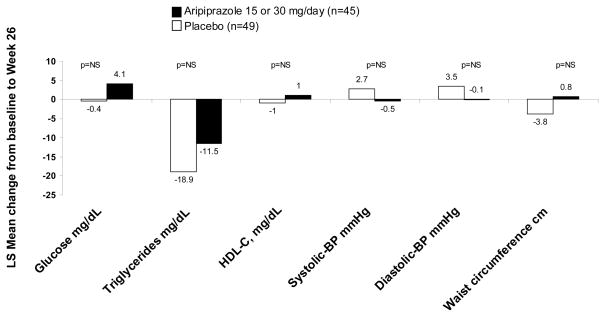

At baseline (entry into 26-week double-blind treatment), 125 had data available for all five metabolic syndrome criteria, and 94 patients also had evaluable data on the five components of MetSyn at endpoint (placebo n=49; aripiprazole n=45). The least squares mean change from baseline to Week 26 in each of the five components of metabolic syndrome are shown in Figure 1. Most of the changes that occurred over this time period were minimal. The largest change was seen in triglyceride levels, with a decrease of −18.9 mg/dL in the placebo group and −11.5 mg/dL in the aripiprazole group. Glucose levels showed the second largest change, with a decrease of −0.4 mg/dL in the placebo group and an increase of 4.1 mg/dL in the aripiprazole group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean change from maintenance phase baseline to Week 26 in the components of the metabolic syndrome (last observation carried forward data set)

LS = Least squares. NS = Not significant. Mean ± SD baseline values for aripiprazole vs. placebo were as follows: glucose 90.4 ± 19.7 vs. 95.4 ± 32.4 mg/dL; triglycerides 139.3 ± 74.2 vs. 164.1 ± 148.3 mg/dL; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) 49.7 ± 14.4 vs. 52.7 ± 21.7 mg/dL; systolic blood pressure 118.5 ± 13.1 vs. 117.6 ± 13.4 mmHg; diastolic blood pressure 72.6 ± 9.8 vs. 73.6 ± 9.9 mmHg; waist circumference 99.3 ± 14.8 vs. 100.4 ± 22.0 cm

In addition to the mean change in components of metabolic syndrome, the mean change in weight and BMI were also calculated. Small changes in weight from baseline to endpoint were seen in both the placebo (mean [SD] baseline 88.1 [25.3] kg; least squares mean change ± SE at endpoint −1.9 ± 1.1 kg) and aripiprazole groups (baseline 84.1 [20.4] kg; endpoint +0.3 ± 1.1 kg, p=0.147). Similarly, minimal changes in BMI from baseline to endpoint were seen with placebo (baseline 30.8 [8.3] kg/m2; endpoint −0.9 ± 0.4 kg/m2) or aripiprazole (baseline 30.9 [7.4] kg/m2; endpoint +0.1 ± 0.4 kg/m2, p=0.110).

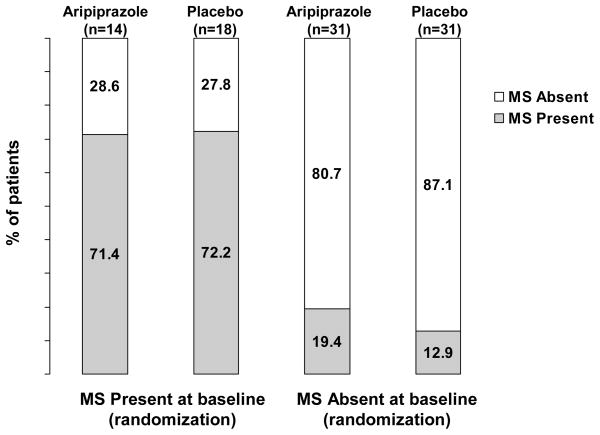

Metabolic syndrome status during double-blind treatment

The percentages of patients who met the criteria for metabolic syndrome at Week 26 stratified by the presence/absence of metabolic syndrome at maintenance phase baseline are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Incidence of metabolic syndrome status at maintenance phase endpoint (Week 26), stratified by the presence/absence of metabolic syndrome at maintenance phase baseline (randomization) (last observation carried forward)

Of the patients who had metabolic syndrome at baseline (aripiprazole, 14/45; placebo, 18/49), the majority still met criteria for the syndrome at Week 26 (aripiprazole, 10/14; 71.4%; placebo, 13/18, 72.2%, p>0.99). Metabolic syndrome had resolved in 5/18 patients (27.8%) in the placebo group and 4/14 patients (28.6%) in the aripiprazole group (Figure 2). Among the patients who did not have metabolic syndrome at baseline (aripiprazole, 31/45; placebo, 31/49), the majority still did not have metabolic syndrome at Week 26. A small proportion of patients had developed metabolic syndrome (aripiprazole, 6/31, 19.4%; placebo, 4/31, 12.9%, p=0.73) (Figure 2).

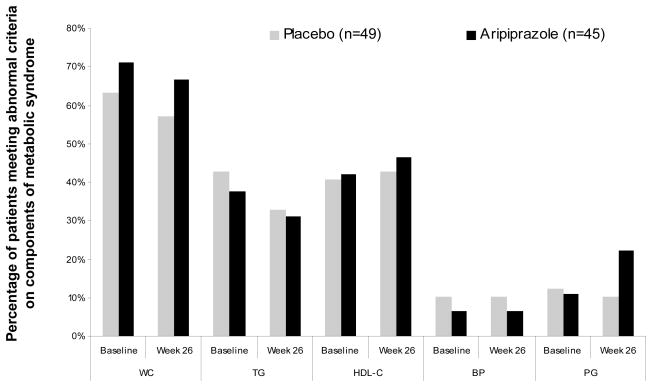

Proportion of patients who met abnormal criteria on each of the five components

The proportion of patients meeting criteria for each of the different components of metabolic syndrome (waist circumference >102 cm (men) or >88 cm (women); triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL; HDL-C <40 mg/dL (men) or <50 mg/dL (women); systolic BP ≥130 mmHg and diastolic BP ≥85 mm Hg; blood glucose ≥100 mg/dL) was similar for both aripiprazole and placebo at randomization and at Week 26 (Figure 3). At all time points and regardless of treatment assignment, a greater proportion of patients met the criteria for high waist circumference, high triglyceride levels or low HDL-C levels than for high glucose levels or high BP (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The prevalence of each of the five components of metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar I disorder at randomization and Week 26 (last observation carried forward data set)

WC = waist circumference; TG = triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; BP, blood pressure; PG= plasma glucose.

DISCUSSION

Analysis of data from this long-term, multicenter, randomized study investigating the safety and efficacy of aripiprazole as monotherapy in patients with bipolar disorder suggests that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder is higher than observed in the general population; 36% of patients with bipolar disorder entered the maintenance phase of this study with metabolic syndrome compared to 20% of adults in a similar age group in the US population 25. The rate of metabolic syndrome at baseline did not differ for patients without prior aripiprazole exposure enrolled ‘de novo’ (37.2%) or those patients who were ‘rolled-over’ from a previous aripiprazole study (37.3%). Thus prior involvement in a clinical trial and potential treatment with aripiprazole was not expected to affect the outcomes of the analyses presented herein. Given that metabolic syndrome is associated with a two- to three-fold increased risk of mortality due to coronary heart disease 4, 26 and a seven-fold risk of developing type 2 diabetes 27, the increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome is a particular cause for concern in those with bipolar disorder who are already at increased risk of medical morbidity and mortality than the general population 28. Furthermore, in addition to significantly increasing the risk for CV disease, metabolic syndrome (or at least some of its components) has been associated with worsened psychiatric outcomes, including a greater likelihood of attempted suicide9.

Results from this analysis also showed that treatment with aripiprazole can be used both short- and longer-term without compromising the metabolic status of patients with bipolar disorder. After 26 weeks of treatment with aripiprazole, resolution of the metabolic syndrome occurred in almost 30% of patients who initially met criteria for this disorder at baseline. Furthermore, the likelihood of developing new onset metabolic syndrome during maintenance phase treatment was low and not significantly different from placebo. If any signal for improvement or worsening of metabolic syndrome is to be identified, it will likely come from a population that is sufficiently enriched for the risk factors under study, where in this trial 36% of patients met criteria for metabolic syndrome upon entry into the maintenance phase. Reversal of metabolic syndrome has previously been observed in a small case series evaluation of patients with schizophrenia following 3 months of treatment with aripiprazole 29. A larger, randomized trial of 173 overweight subjects with schizophrenia treated with olanzapine found that switching to treatment with aripiprazole for 16 weeks resulted in significant reductions in body weight, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol 30. Taken together these observations suggest that there is a low risk of metabolic compromise associated with aripiprazole treatment in patients with bipolar disorder, consistent with long-term studies of aripiprazole in patients with schizophrenia 31, 32.

Of the five components of metabolic syndrome, waist circumference, HDL-C levels, and triglyceride levels had the highest proportion of abnormalities in both the aripiprazole and placebo groups at randomization as well as at Week 26. The effect of 26 weeks of treatment with aripiprazole on the components of metabolic syndrome was also similar to placebo. Criteria for abdominal obesity, as measured by waist circumference, was met by over 60% of patients and consistently demonstrated the highest prevalence of the five components of metabolic syndrome, suggesting that measurement of waist circumference is a practical means for assessing metabolic risk in patients with bipolar disorder. This is in agreement with a study investigating the most clinically useful and cost-effective screening methods for metabolic syndrome, which showed that the presence of abdominal obesity was the most sensitive measure for detecting metabolic syndrome 33. Thus, measuring body weight and/or waist circumference may provide the best and easiest method for evaluating metabolic health. The incidence of clinically significant weight gain in the population studied herein has previously been reported; seven out of 56 patients in the aripiprazole group and no patients in the placebo groups showed ≥7% weight gain 34. The seven patients showing clinically significant weight gain were distributed across BMI categories. The pragmatic utility of screening for abdominal obesity is underscored by recent evidence suggesting that even among normal-weight individuals, an enlarged waist circumference indicates a worrisome level of underlying cardiometabolic abnormalities 35.

Given the high prevalence of metabolic syndrome and the high levels of each of the individual component items at baseline, the findings of the present study suggest an urgent need for appropriate monitoring of metabolic health in patients with bipolar disorder to enable early intervention and, expectantly, a reduction in medical morbidity. Ideally, intervention should involve the provision of diet and exercise counseling to all patients with bipolar disorder, before the components of metabolic syndrome become evident, and certainly once they are evident 6. Despite uniform agreement that monitoring for metabolic syndrome is a necessary facet of clinical care, less than 20% of public mental health patients receive baseline glucose testing when atypical antipsychotics are initiated and less than 10% receive baseline lipid testing 36. Even after the publication of highly cited guidelines for improving the standard of care for managing metabolic risk, routine cardiometabolic monitoring has only marginally improved 37.

Until recently there has been a paucity of data on the effects of atypical antipsychotics on metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder. In 2004 when guidelines for metabolic risk monitoring were jointly published by the American Psychiatric Association and American Diabetes Association, relatively limited epidemiological data were available on aripiprazole and ziprasidone, the two atypical antipsychotics regarded as having the least risk for weight gain or other metabolic problems 18. Nearly five years later there remains no long-term clinical trial data available on metabolic syndrome with ziprasidone in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

The long-term metabolic effects of antipsychotic use among patients with bipolar disorder has not been well documented, thus the present data provide a valuable evidence base to help guide clinical decision-making. However, the findings of this analysis should be considered in light of several limitations. Firstly, while this study enrolled a significant number of patients into the stabilization phase of this study (n=567), data on metabolic status was missing for some of the patients who were rolled over from previous aripiprazole studies. Thus, while the mean exposure to aripiprazole (14 weeks) was similar for both the placebo and aripiprazole groups, we cannot with certainty account for any potential effect of being ‘rolled over’ into this study from another aripiprazole clinical trial. Nevertheless, the rate of metabolic syndrome upon entry into the maintenance phase was similar for both patients who had previously received aripiprazole in another study, and for patients entering ‘de novo’. The metabolic effects of aripiprazole in patients with bipolar II disorder cannot be assessed, as these patients were excluded from participation. Likewise, we cannot determine whether index episode influences the incidence of metabolic syndrome, as all patients were required to have experienced a recent manic or mixed episode. As this is not a true epidemiological study, the rates of metabolic syndrome may be over or underestimated. Overestimation of metabolic syndrome in both treatment arms may also have occurred from the inclusion of select samples of triglyceride and glucose that were non-fasting. Such laboratory values still remain clinically informative, as non-fasting triglyceride levels highly correlate with cardiovascular risk. In fact, triglyceride levels measured 2–4 hours postprandially show a strong association with incident cardiovascular events 38, 39. It should be understood that this study was originally designed as a maintenance trial with time to relapse into a mood episode as the primary outcome measure. Rates of metabolic syndrome and the individual component items of metabolic syndrome were assessed as post-hoc analyses. Thus, the study was not designed nor powered to detect differences in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome between treatments. An additional limitation includes the potential for variation in the manner by which waist circumference was measured by study personnel. Thus, these analyses should still be considered exploratory. Additional data characterizing metabolic health outcomes beyond 26 weeks of observation would be useful. It should also be considered that the study population reported here for the 26-week double-blind phase of the study represents an enriched population of patients who responded to and were stabilized on aripiprazole treatment following a manic or mixed episode. Additional data in patients following a depressive episode may be of interest.

CONCLUSIONS

This study indicates that treatment of bipolar disorder with aripiprazole over 26 weeks does not compromise the metabolic status of this already at-risk patient group. The high prevalence of metabolic syndrome in this study population at baseline further underscores the need for appropriate monitoring of metabolic health in patients with bipolar disorder.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb (Princeton, NJ, USA) and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Editorial support for the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Ogilvy Healthworld; funding was provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Footnotes

Previous presentation:

Data from this manuscript were previously presented as an abstract and poster at the American Psychiatric Association 160th Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, May 19–24, 2007 and the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology 46th Annual Meeting, Boca Raton, Florida, December 9–13, 2007

Suggested reviewers:

Sue McElroy; Trisha Suppes; Roger McIntyre; John Newcomer; David Muzina; Andrea Fagiolini

Clinical trial registration: NCT00036348 registered on www.clinicaltrials.gov

Author disclosures:

David Kemp: Consultant to Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Wyeth; has received honorarium from Servier; participated in CME activities with Organon, a part of Schering-Plough; has received research support from NARSAD and the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Research Fellowship Award. This work is supported in part by a K-award (1KL2RR024990) to Dr. Kemp.

Joseph Calabrese: Receives federal funding from the Department of Defense, Health Resources Services Administration and the National Institutes of Mental Health. Dr Calabrese receives research or grants from the following private industries or non-profit funds: Cleveland Foundation, NARSAD, Repligen and the Stanley Medical Research Institute. Dr Calabrese participates on advisory boards for Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Forest Labs, France Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Organon a part of Schering-Plough, OrthoMcNeil, Repligen, Servier, Solvay/Wyeth and Supernus Pharmaceuticals. He has been involved in CME Activities for: Astra Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, France Foundation, Glaxo Smith Kline, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Organon a part of Schering-Plough, Solvay/Wyeth. He receives research grants from: Abbott, Astra Zeneca, Cephalon, GSK, Janssen, Lilly. He has no equity ownerships or does not participate on any Speakers Bureau.

Quynh-Van Tran: Employee of Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc

Andrei Pikalov: Employee of Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc

James M Eudicone: Employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb

Ross A Baker: Employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb

References

- 1.Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2007;298:1794–1796. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NCEP. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, Niskanen LK, Kumpusalo E, Tuomilehto J, Salonen JT. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA. 2002;288:2709–2716. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.21.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Jama. 2002;287:356–359. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagiolini A, Frank E, Scott JA, Turkin S, Kupfer DJ. Metabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder: findings from the Bipolar Disorder Center for Pennsylvanians. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:424–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardenas J, Saiz PA, Benabarre A, Sierra P, Perez J, Lewis S, Livianos L, Hwang S, Bobes J. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fagiolini A, Frank E, Houck PR, Mallinger AG, Swartz HA, Buysse DJ, Ombao H, Kupfer DJ. Prevalence of obesity and weight change during treatment in patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:528–533. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fagiolini A, Kupfer DJ, Houck PR, Novick DM, Frank E. Obesity as a correlate of outcome in patients with bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:112–117. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Bauer MS, Zeber JE, Copeland LA, Good CB, Pincus HA. Therapeutic drug and cardiovascular disease risk monitoring in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;102:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:565–572. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradford DW, Kim MM, Braxton LE, Marx CE, Butterfield M, Elbogen EB. Access to medical care among persons with psychotic and major affective disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:847–852. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.8.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newcomer JW. Metabolic risk during antipsychotic treatment. Clin Ther. 2004;26:1936–1946. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer JM, Koro CE. The effects of antipsychotic therapy on serum lipids: a comprehensive review. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yumru M, Savas HA, Kurt E, Kaya MC, Selek S, Savas E, Oral ET, Atagun I. Atypical antipsychotics related metabolic syndrome in bipolar patients. J Affect Disord. 2007;98:247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burris KD, Molski TF, Xu C, Ryan E, Tottori K, Kikuchi T, Yocca FD, Molinoff PB. Aripiprazole, a novel antipsychotic, is a high-affinity partial agonist at human dopamine D2 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:381–389. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.033175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jordan S, Koprivica V, Chen R, Tottori K, Kikuchi T, Altar CA. The antipsychotic aripiprazole is a potent, partial agonist at the human 5-HT(1A) receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;441:137–140. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01532-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ADA/APA/AACE/NAASO. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:596–601. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keck PE, Marcus R, Tourkodimitris S, Ali M, Liebeskind A, Saha A, Ingenito G. A placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in patients with acute bipolar mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1651–1658. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keck PE, Calabrese JR, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Carlson BX, Rollin LM, Marcus RN, Sanchez R. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 26-Week trial of aripiprazole in recently manic patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:626–637. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sachs G, Sanchez R, Marcus R, Stock E, McQuade R, Carson W, Abou-Gharbia N, Impellizzeri C, Kaplita S, Rollin L, Iwamoto T. Aripiprazole in the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes in patients with bipolar I disorder: a 3-week placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20:536–546. doi: 10.1177/0269881106059693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vieta E, Bourin M, Sanchez R, Marcus R, Stock E, McQuade RD, Carson W, Abou-Gharbia N, Swanink R, Iwamoto T on behalf of the Aripiprazole Study Group. Effectiveness of aripiprazole v haloperidol in acute bipolar mania: Double-blind, randomised, comparative 12-week trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:235–242. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keck PE, Jr, Calabrese JR, McIntyre RS, McQuade RD, Carson WH, Eudicone JM, Carlson BX, Marcus RN, Sanchez R. Aripiprazole monotherapy for maintenance therapy in bipolar I disorder: a 100-week, double-blind study versus placebo. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1480–1491. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, Jr, Spertus JA, Costa F. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park YW, Zhu S, Palaniappan L, Heshka S, Carnethon MR, Heymsfield SB. The metabolic syndrome: prevalence and associated risk factor findings in the US population from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:427–436. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexander CM, Landsman PB, Teutsch SM, Haffner SM. NCEP-defined metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and prevalence of coronary heart disease among NHANES III participants age 50 years and older. Diabetes. 2003;52:1210–1214. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.5.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laaksonen DE, Lakka HM, Niskanen LK, Kaplan GA, Salonen JT, Lakka TA. Metabolic syndrome and development of diabetes mellitus: application and validation of recently suggested definitions of the metabolic syndrome in a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:1070–1077. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newcomer JW. Medical risk in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Hert M, Hanssens L, van Winkel R, Wampers M, Van Eyck D, Scheen A, Peuskens J. A Case Series: Evaluation of the Metabolic Safety of Aripiprazole. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:823–830. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newcomer JW, Campos JA, Marcus RN, Breder C, Berman RM, Kerselaers W, L’Italien GJ, Nys M, Carson WH, McQuade RD. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind study of the effects of aripiprazole in overweight subjects with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder switched from olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1046–1056. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kasper S, Lerman MN, McQuade RD, Saha A, Carson WH, Ali M, Archibald D, Ingenito G, Marcus R, Pigott T. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole vs. haloperidol for long-term maintenance treatment following acute relapse of schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;6:325–337. doi: 10.1017/S1461145703003651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pigott TA, Carson WH, Saha AR, Torbeyns AF, Stock EG, Ingenito GG. Aripiprazole for the prevention of relapse in stabilized patients with chronic schizophrenia: a placebo-controlled 26-week study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1048–1056. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Straker D, Correll CU, Kramer-Ginsberg E, Abdulhamid N, Koshy F, Rubens E, Saint-Vil R, Kane JM, Manu P. Cost-effective screening for the metabolic syndrome in patients treated with second-generation antipsychotic medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1217–1221. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keck PE, Calabrese J, McQuade RD, Carson W, Carlson BX, Rollin LM, Marcus RN, Sanchez R Group atAS. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 26-week trial of aripiprazole in recently manic patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:626–637. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stefan N, Kantartzis K, Machann J, Schick F, Thamer C, Rittig K, Balletshofer B, Machicao F, Fritsche A, Haring HU. Identification and characterization of metabolically benign obesity in humans. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1609–1616. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morrato EH, Newcomer JW, Allen RR, Valuck RJ. Prevalence of baseline serum glucose and lipid testing in users of second-generation antipsychotic drugs: a retrospective, population-based study of Medicaid claims data. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:316–322. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haupt D, Rosenblatt L, Kim E, Baker R, Whitehead R, Newcomer J. Prevalence and Predictors of Lipid and Glucose Monitoring among Commercially Insured Patients Treated with Second-Generation Antipsychotic Agents. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030383. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, Schnohr P, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. Jama. 2007;298:299–308. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bansal S, Buring JE, Rifai N, Mora S, Sacks FM, Ridker PM. Fasting compared with nonfasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular events in women. Jama. 2007;298:309–316. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]