Abstract

The extensive methylation of green tea polyphenols (GTPs) in vivo may limit their chemopreventive potential. We investigated whether quercetin, a natural inhibitor of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) and multidrug resistance proteins (MRPs), will differentially increase the intracellular concentration and decrease the methylation of GTPs in different cancer cell lines. Intrinsic COMT activity was lowest in lung cancer A549 cells, intermediate in kidney 786-O cells and highest in liver HepG2 cells. Quercetin increased the cellular absorption of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) four-fold in A549 cells with a decreased methylation rate from 63% to 19%, 2-fold in 786-O cells with a decreased methylation from 97% to 56%, while no significant effect was observed in HepG2 cells. The combination significantly decreased the activity and protein expression of COMT and decreased the protein expression of MRP1 compared to individual treatments. The combination exhibited the strongest increase in antiproliferation in A549 cells, an intermediate effect in 786-O cells and lowest effect in HepG2 cells. The effect of quercetin on bioavailability and metabolism of GTPs was confirmed in vivo. SCID mice were administered brewed green tea (GT) and a diet supplemented with 0.4% quercetin alone or in combination for 2 weeks. We observed a 2 to 3-fold increase of total and non-methylated EGCG in lung and kidney and a trend to increase in liver. In summary, combining quercetin with GT provides a promising approach to enhance the chemoprevention of GT. Responses of different cancers to the combination may vary by tissue depending on the intrinsic COMT and MRP activity.

Keywords: Green tea polyphenols, quercetin, methylation, catechol-O-methyltransferase

1. Introduction

The chemopreventive activities of green tea (GT) and green tea polyphenols (GTPs) have been well documented in in vitro cell culture and in animal models against a variety of cancers including lung, liver, prostate, colon, pancreatic, breast, and kidney cancers 1-3. However, the translation of these anti-carcinogenic effects to humans is difficult due to the relatively low concentrations of GTPs achievable in human plasma 4. In addition to their low bioavailability, GTPs are extensively transformed in vivo leading to enhanced excretion and reduced chemopreventive activity 3, 5.

The main active components of GT are (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC), (−)-epicatechin (EC), and (−)-epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG), with EGCG being the most abundant and most biologically active component 5. Upon uptake, the non-gallated GTPs such as EGC and EC undergo extensive glucuronidation and sulfation while the gallated GTPs EGCG and ECG are mainly present in the free form 6. All GTPs are readily methylated by catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) leading to a decrease in urine excretion 7. Previously we found that approximately 50 percent of EGCG was present in methylated form (4″-O-methyl EGCG, 4″-MeEGCG) in human prostate tissue obtained at prostatectomy after consumption of 6 cups of GT daily for 3-5 weeks 8. Methylation significantly decreased the cancer-preventive activity of EGCG in cultured LNCaP prostate cancer cells and Jurkat cells 8, 9.

The bioavailability, cellular uptake and excretion of GTPs are regulated by the activity of the multidrug resistance proteins (MRPs) MRP1 and MRP2 4. MRP1 is located at the basolateral membrane and assists the transport of compounds from the interior of the cells into the interstitial space 10, 11. MRP1 is distributed ubiquitously in the body but occurs in low concentration in the liver 10. MRP2 is located at the apical surface of the liver, kidney and intestine where it transports compounds from bloodstream into the lumen, bile and urine 10.

Quercetin is a flavonoid found in most edible vegetables and fruits particularly in onions, apples, and red wine, and its inhibitory effects on MRPs and COMT activity have been well documented 12-15. Quercetin itself has been shown to exhibit chemopreventive activities in several cancers including liver, lung, and prostate cancers 16-18. The objective of the present study was to determine whether the combined use of quercetin with GTPs will increase cellular uptake of EGCG and inhibit its methylation through the inhibition of MRPs and COMT, thereby enhancing the antiproliferative effect of GTPs. Three cancer cell lines representing the predominant form of their specific cancers were investigated in vitro, including human non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma A549, human renal cell adenocarcinoma 786-O and human liver hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. In addition, the effect of quercetin on the bioavailability and methylation of GTPs was confirmed in vivo in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell line and cell culture

A549, 786-O, and HepG2 cell lines were from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Chicago, IL). A549 and 786-O cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium, and HepG2 cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% (v:v) of fetal bovine serum (FBS) (USA Scientific, Ocala, FL), 100 IU/ml of penicillin and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (Invitrogen Inc, Carlsbad, CA) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

2.2 Cellular absorption of EGCG and quercetin

A549 cells, 786-O cells and HepG2 cells were allowed to grow to 50-60 percent confluency in 100 mm Petri dishes. Cells were incubated with fresh serum-complete medium containing 80μM EGCG (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), 10μM quercetin (Sigma-Aldrich), 20μM quercetin, 80μM EGCG + 10μM quercetin, or 80μM EGCG + 20μM quercetin for 2h. To minimize the effect of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) that may be formed by autoxidation and/or dimerization of EGCG and quercetin in medium 19, 50 U/ml of catalase was added to the medium prior to EGCG and quercetin in all the experiments. The procedures for cell harvest was described previously 8. Briefly, the medium was removed and the dishes were washed with 10 ml of PBS for 3 times. The dishes were placed on ice and cells were collected and homogenized in 100μl of 2% ascorbic acid in water. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15min and the supernatant was transferred and protein precipitated for detection by HPLC-CoulArray electrochemical detection system (ESA, Chelmsford, MA). Cytosolic EGCG and quercetin concentrations were normalized by cytosolic protein determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). All the experiments were repeated three times. In order to confirm the role of COMT in the absorption and metabolism of EGCG under the combination treatment, COMT gene expression was inhibited by treatment with human COMT siRNA (SASI_Hs01_00088008, Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, HepG2 cells were seeded in a density of 2.5×104 cells/cm2 20h before the siRNA transfection. 10nM or 20nM of COMT siRNA was mixed with N-TER nanoparticles (Sigma-Aldrich), diluted in serum-free medium and added to the cell dishes. After 3h incubation, another half volume of 2× serum medium was added and the dishes were incubated for 24h before the replacement of the medium with fresh complete medium. After 48h, cells were harvested and total protein was extracted for the determination of COMT protein expression by Western blot. In a second experiment HepG2 cells were transfected the same way with 10nM siRNA. The cells were treated with EGCG, quercetin or their combination as described above and cellular concentrations of EGCG, quercetin and their methylated metabolites were measured.

2.3 Cell proliferation assay

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5×103 per well and treated with the following: vehicle control (DMSO), 40μM EGCG, 10μM quercetin, 20μM quercetin, 40μM EGCG + 10μM quercetin, or 40μM EGCG + 20μM quercetin for 24 and 48h. Cell proliferation was determined with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) assay using the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). Each concentration had five repeats of wells at each time point. The experiment was repeated three times.

2.4 Determination of COMT activity

Cells were cultured in 60 mm Petri dishes and treated with EGCG and quercetin at the same concentrations as used for cell proliferation assay. After 2h, the cells were harvested and COMT activity were measured followed the procedures described by Reenilä et al 20 with some modifications. Briefly, medium was removed and the dishes were washed with 5 ml of cold PBS for 3 times. The cells were collected and homogenized in 10mM Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.5mM dithiothreitol. The homogenates were centrifuged at 900g for 10min at 4°C and protein concentrations in the supernatant were measured by the Bio-Rad protein assay following the manufacturer’s protocol (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The supernatants were stored at −70°C until use. The COMT activity was evaluated based on the formation of the methyl metabolite vanillic acid (3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzoic acid) of dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBAc) catalyzed by COMT. Briefly, the cell preparation containing 100μg protein was incubated at 37°C with 0.2mM S-adenosyl-L-methionine iodide (AdoMet) (Sigma-Aldrich), 5mM MgCl2, and 200μM DHBAc, buffered with 100mM Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 7.4) in a total volume of 125μl. After 30min, the reaction was terminated by adding 25μl of 4M perchloric acid. Protein was removed by centrifuge at 14,000rpm for 15min, and the supernatant was detected by HPLC-CoulArray detection system for vanillic acid which had a main peak at 500mV. The COMT enzyme activity was expressed as nmol vanillic acid formed/h/mg protein. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

2.5 Western blot analysis of COMT and MRP1 protein expression

The effect of EGCG and quercetin on protein expression of COMT and MRP1 was analyzed in A549 cells who showed the highest sensitivity to the combination treatment. A549 cells were allowed to grow to 50-60% confluency in 60 mm Petri dishes then were treated with vehicle control, 40μM EGCG, 20μM quercetin, or 40μM EGCG + 20μM quercetin for 24h or 48h. The procedure for cell harvest and protein extraction was described before 8. Briefly, the medium was removed and cells were washed three times with cold PBS. The cells were lysed in cold lysis buffer for 5 min on ice and the crude lysate was passed through 26 ½ G needle and cleared by centrifugation. The protein concentration was measured by the Bio-Rad protein assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Bio-Rad Laboratories). For the Western blot analysis, 50 μg of protein was loaded and separated on a 4-12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Proteins were electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blocked in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with rabbit anti-human COMT antibody (sc-25844) at a dilution of 1:1000 and MRP1 antibody (sc-7773-R, Santa Cruz, CA) at a dilution of 1:200 overnight at 4°C. β-actin protein was used as loading control. Goat anti-rabbit IgG-Horseradish Peroxidase was used as the second antibody. Protein was visualized and analyzed using a ChemiDoc XRS (Bio-Rad Laboratories) chemiluminescence detection and imaging system.

2.6 Animal study

All procedures carried out in mice were approved by the UCLA Animal Research Committee in compliance with the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Care (AAA-LAC) International. Male SCID mice (Charles River Laboratories) were bred in a pathogen-free colony and fed a sterilized AIN-93G diet (DYETS Inc., Bethlehem, PA) and water for acclimation. The mice were assigned to one of four groups with 5 mice in each group: 1) control, receiving AIN-93G diet + water; 2) GT, receiving AIN-93G diet + brewed GT as drinking water; 3) quercetin, receiving 0.4% quercetin supplemented AIN-93G diet (customized by DYETS inc.) + water; and 4) GT + quercetin, receiving 0.4% quercetin supplemented AIN-93G diet + brewed GT water. GT was brewed three times a week on Monday, Wednesday and Friday by steeping 1 tea bag in 240 mL of boiling water (pH 3) for 5 minutes. Tea bags (Authentic GT) were generously provided by Celestial Seasonings (Boulder, CO). The GTP composition of the brewed GT in mg/L was as follows: EGC 204 ± 4, EGCG 388 ± 12, EC 44 ± 2, ECG 64 ± 7 and catechin 7 ± 1. After 2 weeks of the intervention, the mice were sacrificed and lung, kidney and liver tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in −70 °C for the analysis of GTP contents.

2.7 Analysis of tissue GTPs

150 mg of lung, kidney and liver tissues was homogenized and incubated with 1,000 units of β-glucuronidase (G7896, Sigma-Aldrich) and 40 units of sulfatase (S-9754, Sigma-Aldrich) buffered in 300 μL of 0.5 M phosphate buffer (pH 5.0) at 37°C for 45min to digest the conjugated forms into free forms. After incubation, 4× extracts with 1ml of ethyl acetate were combined with 20 μL of 2% ascorbic acid in methanol and dried in vacuum and reconstituted for HPLC-CoulArray detection (ESA, Chelmsford, MA). The potentials of the 8 channels of the CoulArray detector were sequentially set at −60 mV, 20 mV, 100 mV, and 180 mV, 260 mV, 340 mV, 420 mV, and 500 mV.

2.8 Statistical analysis

SPSS (Version 18.0, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analyses. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparison of means was performed by two independent samples t-test, or one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s posttest. Differences were considered significant if P<0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Quercetin increased the cellular uptake and decreased methylation of EGCG in vitro

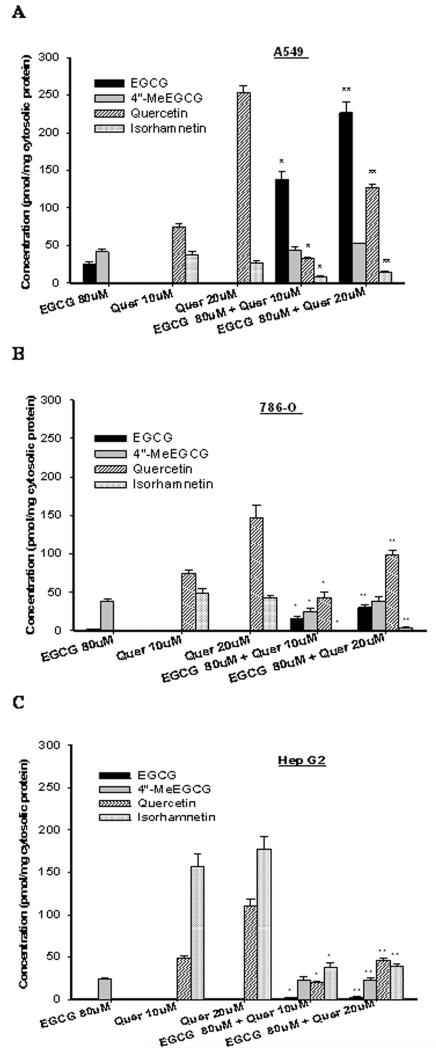

The cellular uptake and methylation of EGCG varied significantly in the three cell lines. After incubation with EGCG alone for 2h, total EGCG concentration was 2 to 3-fold higher in A549 cells compared to 786-O cells and HepG2 cells (Figure 1). Co-treatment with 10 μmol/L of quercetin increased the cellular concentration of total EGCG by 3 to 4-fold in A549 cells in a dose-dependent manner and 2-fold in 786-O cells. No significant change in cellular uptake of EGCG was observed in HepG2 cells by the combination treatment with quercetin. Intracellular EGCG was extensively methylated to 4″-MeEGCG in all three cell lines when treated with EGCG alone (Figure 1). Co-treatment with quercetin substantially decreased 4″-MeEGCG concentration compared to total EGCG from 63% to 19% in A549 cells and from 97% to 56% in 786-O cells. A small but statistically significant decrease of the methylated portion of total EGCG from 98% to 90% was observed in HepG2 cells. Quercetin exhibited a much higher cellular bioavailability than EGCG. When treated with 20μM of quercetin the intracellular concentration of total quercetin was 5 to 11-fold higher compared to total EGCG when exposed to 80μM of EGCG in the three cell lines. However, co-treatment with EGCG decreased the total intracellular concentration of quercetin by 2 to 3-fold concurrent with a 10-30% decrease in isorhamnetin (3′-O-methyl quercetin) in all three cell lines (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cellular uptake and metabolism of EGCG and quercetin under different treatments. A549 (A), 786-O (B) and HepG2 (C) cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of EGCG and quercetin (Quer) alone or in combination. Cellular contents were detected 2h after treatment. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. * or ** represents significant difference compared to respective individual treatments (P<0.05).

When HepG2 cells were treated with COMT siRNA at 10nM and 20nM, the COMT protein expression was inhibited by 30% and 40%, respectively (Supplement, Figure 1). After pre-treatment with 10nM of COMT siRNA, the co-treatment of quercetin with EGCG significantly increased the intracellular concentrations of total EGCG by 17 times compared to individual EGCG treatment, and decreased the methylation rate of EGCG from 32% to 22%.

3.2 Quercetin increased the anti-proliferative effect of EGCG

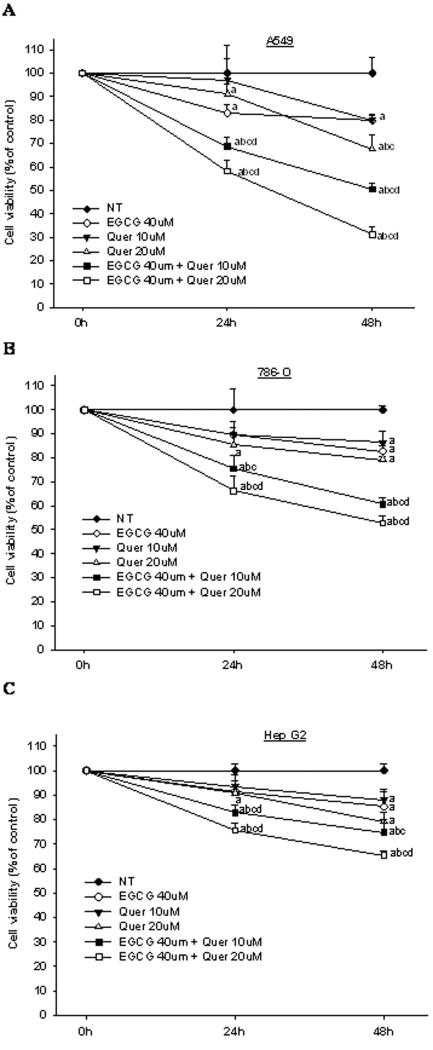

Quercetin dose-dependently increased the anti-proliferative effect of EGCG in all three cell lines at 24h and 48h (Figure 2). The combination of quercetin with EGCG demonstrated the strongest increase in antiproliferation in A549 cells. Cell proliferation was inhibited by 17%, 9% and 42% with the treatment of 40μM of EGCG, 20μM of quercetin and their combination, respectively, at 24h, while by 20%, 32% and 69% at 48h. In 786-O cells and HepG2 cells the combination of quercetin and EGCG demonstrated an intermediate and lowest stimulatory effect, respectively. The proliferation of 786-O cells was inhibited by 11%, 15% and 34% by 40μM of EGCG, 20μM of quercetin and their combination treatments, respectively, at 24h, and by 17%, 21% and 47% at 48h; while HepG2 cell proliferation was inhibited by 9%, 9% and 24% at 24h, and 15%, 21% and 35% at 48h.

Figure 2.

Cell proliferation under different treatments during 48 hr. A549 (A), 786-O (B) and HepG2 (C) cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of EGCG and quercetin alone or in combination for 24h and 48h. Cell proliferation was measured by ATP assay. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. The superscript letters represent significant difference between groups (P<0.05): a compared to vehicle control (NT); b compared to 40μM of EGCG treatment; c compared to 10μM of quercetin treatment; d compared to 20μM of quercetin treatment.

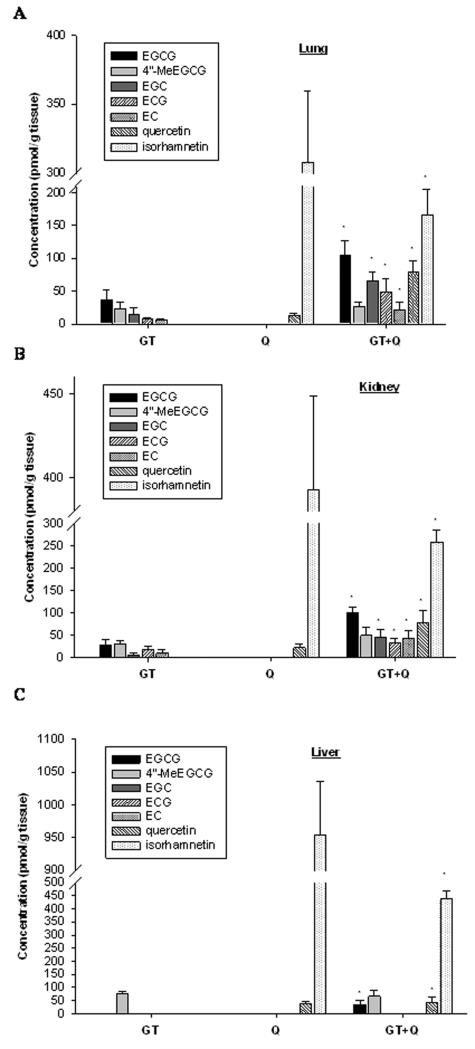

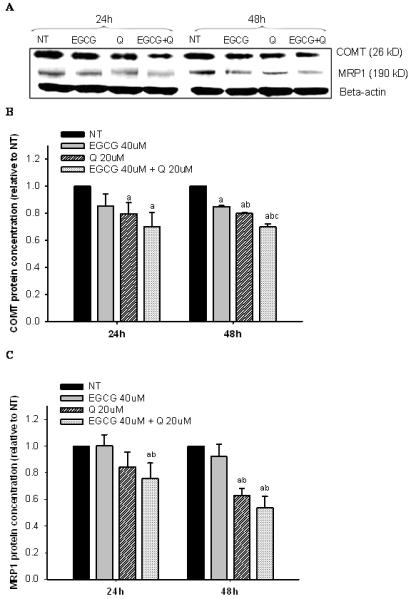

3.3 Quercetin increased the inhibition of COMT activity and protein expression

The baseline COMT activity in HepG2 cells was 4 and 24 times higher compared to 786-O cells and A540 cells, respectively (Figure 3). Both EGCG and quercetin were able to inhibit the activity of COMT in all three cell lines. Quercetin in combination with EGCG significantly enhanced the inhibitory effect in a dose-dependent manner. Western blot analysis in A549 cells showed a small but significant inhibition of COMT protein expression by both EGCG and quercetin alone after treatment for 48h, but quercetin was stronger than EGCG (Figure 4 A and B).When cells were treated with EGCG and quercetin the COMT protein concentration was decreased by 30% compared to control.

Figure 3.

Impact on COMT activity by different treatments. A549 (A), 786-O (B) and HepG2 (C) cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of EGCG and quercetin alone or in combination for 2h. COMT activity was evaluated based on the formation of the methyl metabolite vanillic acid (3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzoic acid) from dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBAc) catalyzed by COMT. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. The superscript letters represent significant difference between groups (P<0.05): a compared to NT; b compared to 40μM of EGCG treatment; c compared to 10μM of quercetin treatment; d compared to 20μM of quercetin treatment.

Figure 4.

Modulation of protein expression of COMT and MRP1 by different treatments. A549 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of EGCG and quercetin alone or in combination for 24h and 48h. COMT (A, B) and MRP1 (A, C) protein expression was evaluated by Western blot. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. The superscript letters represent significant difference between groups (P<0.05): a compared to vehicle control (NT); b compared to 40 μM of EGCG treatment; c compared to 20 μM of quercetin treatment.

3.4 Quercetin inhibited MRP1 protein expression

EGCG treatment at 40 μM did not affect the protein level of MRP1 in A549 cells. Quercetin treatment of 20 μM inhibited MRP1 protein expression significantly over time by 16% and 37% at 24h and 48h, respectively (Figure 4 A and C). The co-treatment with EGCG and quercetin further decreased the MRP1 protein expression compared to quercetin alone (Figure 4 A and C).

3.5 Quercetin increased the bioavailability and decreased methylation of GTPs in vivo

No difference in food and water consumption and body weight was observed in SCID mice in the four intervention groups. The average daily consumption of diet was 2.8 ± 0.6 g per mouse, and 3.8 ± 0.2 mL of water. The tissue concentrations of GTPs, quercetin and their metabolites were below the detection limit in tissues from the control group. After 2-weeks of GT intervention, the major GTPs including EGCG, EGC, ECG, and EC were found in mouse lung and kidney (Figure 5A and B). In lung tissue 39 percent of total EGCG was found in methylated form (4″-MeEGCG) while 53 percent of EGCG was methylated in the mouse kidney. However, in liver tissue EGCG was only present in methylated form (Figure 5C). Co-treatment of quercetin with GT significantly increased the tissue concentrations of total EGCG, EGC, ECG, and EC by 2 to 3-fold in lung and kidney, while only a small increase (1.3 fold) of total EGCG was observed in mouse liver (Figure 5). Concurrently, the percentage of 4″-MeEGCG of total EGCG was decreased from 40% to 20% in lung, from 53% to 33% in kidney, and from 100% to 66% in liver. When mice were treated with quercetin alone, about 95 percent of quercetin was found in methylated form (isorhamnetin) in lung, kidney and liver tissues (Figure 5B). The combination of quercetin with GT decreased the tissue concentrations of total quercetin by 20-50% along with a decrease in isorhamnetin ratio to quercetin by 90%, 81% and 61% in lung, kidney and liver, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Tissue concentrations of GTPs, quercetin and their metabolites in SCID mice. SCID mice (n=5) were randomly assigned to GT (A), quercetin (B), GT + quercetin (C) groups receiving AIN-93G + brewed tea, AIN-93G supplemented with 0.4% quercetin + blank water, or AIN-93G supplemented with 0.4% quercetin + brewed tea, respectively, for 2 weeks. A group of mice (n=5) fed AIN-93G diet + blank water served as control. Tissue contents of GTPs, quercetin and their metabolites were detected by HPLC-electrochemical detection. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. * compared to GT alone or Q alone group, P<0.05.

4. Discussion

Our results demonstrated that combined treatment with EGCG and quercetin enhanced the chemopreventive activity of EGCG in different cancer cell lines by increasing the bioavailability and decreasing the methylation of GTPs. The extent of the quercetin effect varied by tissue type depending on the baseline activity and protein concentration of COMT. The important role of catechol O-methylation of GTPs in cancer prevention has been supported by evidence from an epidemiological study in breast cancer 21. Due to a common polymorphism of COMT its activity can vary by 3 to 4-fold 22. A case control study in Asian-American women provided evidence that the risk of breast cancer was significantly reduced only among tea drinkers possessing at least one low-activity COMT allele 21. The importance of COMT activity to chemoprevention by GT is further supported by our previous findings that EGCG was extensively methylated in human prostate tissues obtained from prostatectomy and in mouse tissues after GT consumption, and that methylation significantly decreased the anticancer activitities of EGCG as shown by our laboratory and by other investigators 8, 9. Results from the present study demonstrated an inverse relationship of increase in EGCG bioavailability in cells treated with quercetin and EGCG to COMT activity. A549 cells had the lowest COMT activity among the three cell lines correlating to the strongest inhibition in cell proliferation by the combination treatment. However, HepG2 cells demonstrated the least sensitivity to the combination probably in part due to their high intrinsic COMT activity. After the inhibition of COMT gene expression by COMT siRNA, the cellular uptake of EGCG in HepG2 cells was significantly increased concurrent with decreased methylation of EGCG in response to the co-treatment with quercetin, which confirms the effect of COMT. Quercetin has been reported to inhibit COMT activity through a combination of two mechanisms: one through the formation of S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine as a result of its own rapid O-methylation catalyzed by COMT, and the other as its direct competitive inhibition of the enzyme by serving as a substrate 23. In addition to the ability to inhibit COMT activity, quercetin demonstrated a stronger inhibitory effect on COMT protein expression than EGCG, leading to decreased methylation of GTPs both in vitro and in vivo. Recently, Landis-Piwowar et al. reported that a decrease in COMT activity in breast cancer cells led to an increase in proteasome inhibition and apoptosis induction by EGCG treatment 24, supporting the important role of COMT in GT chemoprevention.

The cellular uptake and excretion of GTPs are mainly regulated by MRP1 and MRP2 as well as by the organic anion-transporting polypeptides (OATPs) 4, 26. The MRPs are members of the ATP binding cassette superfamily of transport proteins 4. MRP1 is present widely throughout the body with relatively high levels in lung and kidney but lower levels in liver 10. MRP2 is mainly found in liver, kidney and intestine 10. GTPs are substrates for both MRP1 and MRP2 4. Quercetin has been demonstrated to inhibit the MRP activity with a 12-fold stronger effect on MRP1 than on MRP2 12. It is the main function of MRP1 to transport substrates out of the cell. Therefore with quercetin mostly inhibiting MRP1 it exhibited the strongest increase in cellular concentration of EGCG in lung cancer A549 cells where MRP1 is mainly located, a moderate increase in kidney cancer 786-O cells with both MRP1 and MRP2, while we observed the weakest effect in liver cancer HepG2 cells with mainly MRP2 present. Quercetin is extensively methylated, sulfated, or glucuronidated upon uptake 25. It has been demonstrated that these quercetin metabolites, such as isorhamnetin and 7-O-glucuronosyl quercetin exhibited equal or stronger inhibition on MRPs compared to quercetin 26. Therefore we are confident that quercetin will also inhibit MRPs in vivo. Both EGCG and quercetin may also use the OATPs for transport into the cells 27, 28. It has been demonstrated that EGCG inhibited OATP1A2, OATP1B1, and OATP2B1 in a dose-dependent manner, which may further inhibit the uptake of quercetin by the cells 27, 28.

The cellular concentrations of total quercetin was decreased when administered in combination with EGCG, which was also observed in our in vivo mouse studies. This may be due to a competition of transport in and out of the tissue cells as well as during the intestinal absorption process 27,28. Possibly the increase in intracellular EGCG concentration compensated for the loss of cellular quercetin contents, leading to a synergistic/additive effect in anti-proliferation by the combination. On the other hand, the decreased absorption of quercetin may decrease the risk of any potential side effects considering its relatively high bioavailability as demonstrated in our in vitro studies. The percentage of isorhamnetin in total quercetin was much higher in mouse tissues compared to the ratio observed in cell culture, probably due to the entensive methylation of quercetin upon uptake in the small intestine and in liver resulting in high concentrations of isorhamnetin in bloodstream and subsequent absorption by tissues29.

Results from our mouse study confirmed the effect of quercetin in vivo to increase the bioavailability of GTPs and decrease their methylation. Consistant with our in vitro findings, a 2 to 3-fold increase in tissues concentration of both total and non-methylated EGCG and other GTPs in lung and kidney was observed in the combination group. However, only a small increase (1.3 fold) of total EGCG was observed in the liver with a small amount in non-methylated form. The different tissue biovailability of GTPs may be associated with the efficacy of GT in chemoprevention of different cancers. Lung cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer as well as the leading cause of cancer death worldwide 30,31. Kidney cancer is the tenth leading cause of cancer death in men in developed countries and liver cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide 31. Tobacco smoking is the most important risk factor for lung cancer 32. The comsumption of GT reduced the oxidative DNA damage (8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine) in smokers 33, 34. In additon, the inhibitory effect of GT on lung tumorigenesis has been well demonstrated in animal models at different stages of carcinogenesis including initiation, promotion and metastasis 35. GT has been protective against kidney and liver carcinogenesis in laboratory studies 1, 3. However, there is limited evidence from human studies that GT could reduce the incidence of kidney or liver cancer 36, 37. The presented results demonstrated that quercetin significantly increased the anti-prolierative effect of EGCG in A549 cells, 786-O and HepG2 cells, suggesting a promising approach to enhance the chemoprevention of GT in these cancers through the combination of quercetin with GT. On the other hand, quercetin did not cause a significant increase of GTP concentrations in mouse liver tissues, which minimizes the posibility of liver toxicity due to the combination.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated in vitro and in vivo that quercetin increased the bioavailability of GTPs and decreased their methylation leading to an enhanced anti-proliferative effect in different cancer cells. However, the combined effect may vary based on the activity and protein expression of COMT and MRPs in different tissues. Future studies are needed to investigate the tumor inhibitory effect of the combination in animal models and in humans.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: NIH grant RO3 CA150047-01 (S.M. Henning), DOD grant W81XWH-10-1-0298 (P. Wang)

References

- 1.Yang CS, Maliakal P, Meng X. Inhibition of carcinogenesis by tea. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:25–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.082101.154309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crespy V, Williamson G. A review of the health effects of green tea catechins in in vivo animal models. J Nutr. 2004;134:3431S–3440S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.12.3431S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carvalho M, Jerónimo C, Valentão P, Andrade PB, Silva BM. Green tea: A promising anticancer agent for renal cell carcinoma. Food Chemistry. 2010;122:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang CS, Sang S, Lambert JD, Lee MJ. Bioavailability issues in studying the health effects of plant polyphenolic compounds. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52(Suppl 1):S139–151. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang CS, Wang X, Lu G, Picinich SC. Cancer prevention by tea: animal studies, molecular mechanisms and human relevance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:429–439. doi: 10.1038/nrc2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henning SM, Choo JJ, Heber D. Nongallated compared with gallated flavan-3-ols in green and black tea are more bioavailable. J Nutr. 2008;138:1529S–1534S. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.8.1529S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inoue-Choi M, Yuan JM, Yang CS, Van Den Berg DJ, Lee MJ, Gao YT, Yu MC. Genetic Association Between the COMT Genotype and Urinary Levels of Tea Polyphenols and Their Metabolites among Daily Green Tea Drinkers. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2010;1:114–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang P, Aronson WJ, Huang M, Zhang Y, Lee RP, Heber D, Henning SM. Green tea polyphenols and metabolites in prostatectomy tissue: implications for cancer prevention. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2010;3:985–993. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landis-Piwowar KR, Wan SB, Wiegand RA, Kuhn DJ, Chan TH, Dou QP. Methylation suppresses the proteasome-inhibitory function of green tea polyphenols. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:252–260. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borst P, Evers R, Kool M, Wijnholds J. The multidrug resistance protein family. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1461:347–357. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hong J, Lambert JD, Lee SH, Sinko PJ, Yang CS. Involvement of multidrug resistance-associated proteins in regulating cellular levels of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate and its methyl metabolites. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;310:222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Zanden JJ, Wortelboer HM, Bijlsma S, Punt A, Usta M, Bladeren PJ, Rietjens IM, Cnubben NH. Quantitative structure activity relationship studies on the flavonoid mediated inhibition of multidrug resistance proteins 1 and 2. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:699–708. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagai M, Conney AH, Zhu BT. Strong inhibitory effects of common tea catechins and bioflavonoids on the O-methylation of catechol estrogens catalyzed by human liver cytosolic catechol-O-methyltransferase. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:497–504. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.5.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh A, Naidu PS, Kulkarni SK. Quercetin potentiates L-Dopa reversal of drug-induced catalepsy in rats: possible COMT/MAO inhibition. Pharmacology. 2003;68:81–88. doi: 10.1159/000069533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim KA, Park PW, Park JY. Short-term effect of quercetin on the pharmacokinetics of fexofenadine, a substrate of P-glycoprotein, in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:609–614. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma ZS, Huynh TH, Ng CP, Do PT, Nguyen TH, Huynh H. Reduction of CWR22 prostate tumor xenograft growth by combined tamoxifen-quercetin treatment is associated with inhibition of angiogenesis and cellular proliferation. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:1297–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang JH, Hsia TC, Kuo HM, Chao PD, Chou CC, Wei YH, Chung JG. Inhibition of lung cancer cell growth by quercetin glucuronides via G2/M arrest and induction of apoptosis. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:296–304. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.005280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granado-Serrano AB, Martin MA, Bravo L, Goya L, Ramos S. Quercetin modulates NF-kappa B and AP-1/JNK pathways to induce cell death in human hepatoma cells. Nutr Cancer. 2010;62:390–401. doi: 10.1080/01635580903441196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang GY, Liao J, Li C, Chung J, Yurkow EJ, Ho CT, Yang CS. Effect of black and green tea polyphenols on c-jun phosphorylation and H(2)O(2) production in transformed and non-transformed human bronchial cell lines: possible mechanisms of cell growth inhibition and apoptosis induction. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:2035–2039. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.11.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reenila I, Tuomainen P, Mannisto PT. Improved assay of reaction products to quantitate catechol-O-methyltransferase activity by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1995;663:137–142. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(94)00433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu AH, Tseng CC, Van Den Berg D, Yu MC. Tea intake, COMT genotype, and breast cancer in Asian-American women. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7526–7529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawling S, Roodi N, Mernaugh RL, Wang X, Parl FF. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)-mediated metabolism of catechol estrogens: comparison of wild-type and variant COMT isoforms. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6716–6722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu BT, Liehr JG. Inhibition of catechol O-methyltransferase-catalyzed O-methylation of 2- and 4-hydroxyestradiol by quercetin. Possible role in estradiol-induced tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1357–1363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landis-Piwowar K, Chen D, Chan TH, Dou QP. Inhibition of catechol-Omicron-methyltransferase activity in human breast cancer cells enhances the biological effect of the green tea polyphenol (−)-EGCG. Oncol Rep. 2010;24:563–569. doi: 10.3892/or_00000893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Day AJ, Mellon F, Barron D, Sarrazin G, Morgan MR, Williamson G. Human metabolism of dietary flavonoids: identification of plasma metabolites of quercetin. Free Radic Res. 2001;35:941–952. doi: 10.1080/10715760100301441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Zanden JJ, van der Woude H, Vaessen J, Usta M, Wortelboer HM, Cnubben NH, Rietjens IM. The effect of quercetin phase II metabolism on its MRP1 and MRP2 inhibiting potential. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roth M, Timmermann BN, Hagenbuch B. Interactions of green tea catechins with organic anion-transporting polypeptides. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39:920–926. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.036640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nait Chabane M, Al Ahmad A, Peluso J, Muller CD, Ubeaud G. Quercetin and naringenin transport across human intestinal Caco-2 cells. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009;61:1473–1483. doi: 10.1211/jpp/61.11.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morand C, Manach C, Crespy V, Remesy C. Respective bioavailability of quercetin aglycone and its glycosides in a rat model. Biofactors. 2000;12:169–174. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520120127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Cancer Society . Cancer facts & figures 2011. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2011. p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Cancer Society . Global Cancer Facts & Figures 2nd Edition. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2011. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mackay J, Jemal A, Lee N, Parkin D. The Cancer Atlas. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2006. Chapter 13: Lung Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hakim IA, Chow HH, Harris RB. Green tea consumption is associated with decreased DNA damage among GSTM1-positive smokers regardless of their hOGG1 genotype. J Nutr. 2008;138:1567S–1571S. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.8.1567S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klaunig JE, Xu Y, Han C, Kamendulis LM, Chen J, Heiser C, Gordon MS, Mohler ER., 3rd The effect of tea consumption on oxidative stress in smokers and nonsmokers. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1999;220:249–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.1999.d01-43.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang CS, Wang H, Li GX, Yang Z, Guan F, Jin H. Cancer prevention by tea: Evidence from laboratory studies. Pharmacol Res. 2011;64:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boehm K, Borrelli F, Ernst E, Habacher G, Hung SK, Milazzo S, Horneber M. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) for the prevention of cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD005004. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005004.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JE, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, Adami HO, Bernstein L, van den Brandt PA, Buring JE, Cho E, English D, Folsom AR, Freudenheim JL, Gile GG, Giovannucci E, Horn-Ross PL, Leitzmann M, Marshall JR, Mannisto S, McCullough ML, Miller AB, Parker AS, Pietinen P, Rodriguez C, Rohan TE, Schatzkin A, Schouten LJ, Willett WC, Wolk A, Zhang SM, Smith-Warner SA. Intakes of coffee, tea, milk, soda and juice and renal cell cancer in a pooled analysis of 13 prospective studies. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2246–2253. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]