Abstract

Pannexin1 (Panx1) originally was discovered as a gap junction related protein. However, rather than forming the cell-to-cell channels of gap junctions, Panx1 forms a mechanosensitive and highly ATP permeable channel in the cell membrane allowing the exchange of molecules between the cytoplasm and the extracellular space. The list of arguments for Panx1 representing the major ATP release channel includes: (1) Panx1 is expressed in (all?) cells releasing ATP in a non-vesicular fashion, such as erythrocytes; (2) in cells with polar release of ATP, Panx1 is expressed at the ATP release site, such as the apical membrane in airway epithelial cells; (3) the pharmacology of Panx1 channels matches that of ATP release; (4) mutation of Panx1 in strategic positions in the protein modifies ATP release; and (5) knockdown or knockout of Panx1 attenuates or abolishes ATP release. Panx1, in association with the purinergic receptor P2X7, is involved in the innate immune response and in apoptotic/pyroptotic cell death. Inflammatory processes are responsible for amplification of the primary lesion in CNS trauma and stroke. Panx1, as an early signal event and as a signal amplifier in these processes, is an obvious target for the prevention of secondary cell death due to inflammasome activity. Since Panx1 inhibitors such as probenecid are already clinically tested in different settings they should be considered for therapy in stroke and CNS trauma.

Keywords: Pannexin, Probenecid, Glibenclamide, Inflammasome, Apoptosis, Gap junction

1. Introduction

In the last few years researchers have experienced a strong push towards translational medicine. That push comes from university administrators who salivate for the dollars to be recouped from their hard earned overhead on research grants as well as from funding agencies that often are pressured to fund more on an opportunistic than a rational basis. While it is the very mission of medical research to eventually provide cures for diseases, it is often overlooked that in order to “translate” one first needs a “text”. In other words, often the basic knowledge is not there to design a logical approach for disease management. The story of the Pannexin proteins exemplifies that the transition period from discovery to the bedside can be a short one, when diligence, serendipity, persistence, fortuity, kismet and a tad of intuition in different laboratories come together.

Pannexins were discovered in 2000, when Panchin et al. (2000) described a second family of gap junction proteins in the human genome, in addition to the well-characterized connexins. However, as the title of this review indicates, there is some uncertainty about the exact date. Preceding Panchin’s discovery by 4 years, the sequence of the Pannexin1 protein was cloned and deposited to GenBank by Graeme Bolger under the name MRS1. The first recognition of the functional role of Pannexin1 as an ATP release channel came 4 years later (Bao et al., 2004), thus the 11±4 years. Panchin’s discovery was independent of the MRS1 sequence and it was the trigger for the Bao et al. (2004) study. The latter, however, was performed with the MRS1 clone obtained from Graeme Bolger.

Until 11 years ago, there were only two families of gap junction proteins known to form cell-to-cell channels that provide a direct hydrophilic path from cell to cell. In vertebrates connexins were known to form gap junctions and the same structure was known to be formed by innexins in invertebrates. (A third family found in viruses, the vinnexins (Webb et al., 2006), will not be further discussed.) Although these proteins form similar channels, there is no sequence homology between them. Panchin searched in the human genome for sequences homologous to innexins and found what he then called the pannexins.

2. Pannexins, their role in health and disease

2.1. The non-gap junction function of pannexins

Of the 20,000–30,000 genes in the human genome, 3 encode pannexins: Panx1, Panx2 and Panx3. At present about 20% of all genes are annotated but it is any one’s guess how many of these annotations are correct. It is probably an optimistic view that 1–5% of the annotations are accurate. As of this writing, the annotation of Pannexin in GenBank is: “Pathways for the PANX1 gene: Electrical transmission across gap junctions”.

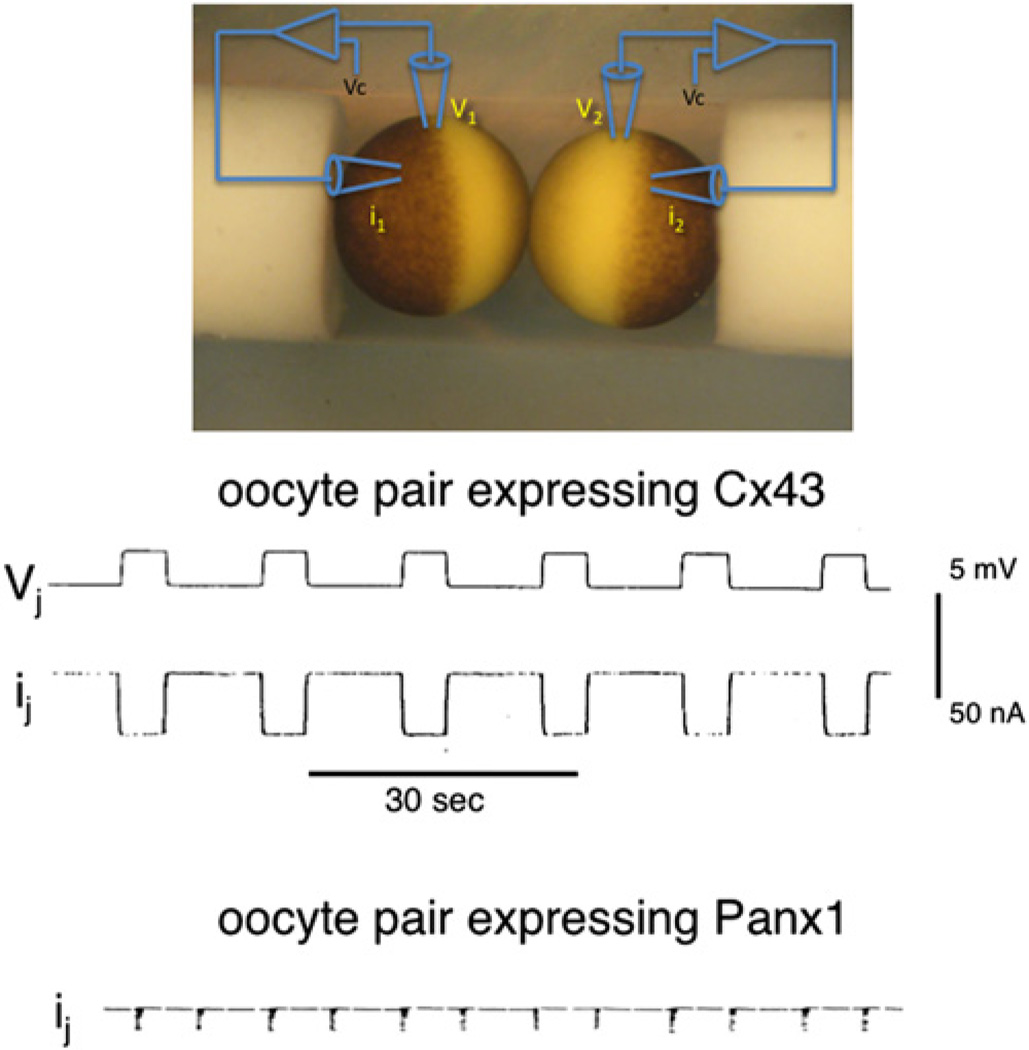

A convenient way to test for gap junction function of proteins is the paired oocyte assay (Dahl et al., 1987; Dahl, 1992; Werner et al., 1985). When oocytes are injected with mRNA encoding connexins and allowed to build a pool of precursors, junctional conductance becomes detectable within minutes after establishing an oocyte pair. Fig. 1 shows a record of robust transjunctional currents in oocytes 30 min after pairing and 48 h after injection of Cx43 mRNA into the cells. The currents indicate the presence of ~200,000 open channels. Channel formation rates for various connexins under these experimental conditions average to 40–50 per second (Dahl et al., 1992). Fig. 1 also shows current records from oocyte pairs expressing Panx1 subjected to the exact same experimental paradigm as applied to connexin expressing oocytes. No junctional currents were observed, although, as to be shown later, the membranes contained large amounts of Panx1 protein. Bruzzone et al. (2003) had reported that oocyte pairs expressing Panx1 exhibited transjunctional currents. However, these observations were made with excessively long pairing times of 24–48 h, indicating an inefficient gap junction channel formation rate. As pointed out by Boassa et al. (2008) the oocytes’ tendency for faulty glycosylation likely is the cause of artifactual gap junction formation by Panx1 in this expression system.

Fig. 1.

Junctional currents in Xenopus oocyte pairs. The membrane potential of both oocytes of the pair are voltage clamped to the same voltage and by stepping the potential of one cell repetitively, transient transjunctional voltages are established (Vj trace). Transjunctional currents (ij) are prominent in the Cx43 expressing pair but are absent in the Panx1 expressing pair (the excursions in this trace are stimulus artifacts).

There is a long list of additional arguments against a gap junction function of pannexins: (1) Immunohistological staining of pannexins does not yield the typical punctate staining for gap junctions (Dahl and Locovei, 2006; Huang et al., 2007; Locovei et al., 2006a). (2) Panx1 is expressed in single cells, such as erythrocytes, which do not form gap junctions (Locovei et al., 2006a). (3) In polarized cells, i.e. cells lacking symmetry such as airway epithelial cells, Panx1 is exclusively localized to the apical membrane, which does not participate in cell to cell contact (Ransford et al., 2009). (4) In neurons, Panx1 is found asymmetrically distributed at synapses with exclusive localization at the postsynaptic membrane, excluding a function as an electrical synapse (Zoidl et al., 2007a). (5) Pannexins, including Panx1, are glycoproteins (Boassa et al., 2007; Penuela et al., 2007) and the sugar tree can be expected to sterically hinder the docking of pannexin channels to each other (Boassa et al., 2008). Additional arguments against a gap junction function can be found in Dahl and Locovei (2006).

In other expression systems Panx1 typically fails to form gap junction channels (Boassa et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2007; Penuela et al., 2007). Nevertheless, two reports claim otherwise (Lai et al., 2007; Vanden Abeele et al., 2006) without presentation of proof that the junctional communication is indeed mediated by Panx1. With the gap junction role of connexins well established, the stakes for claims of gap junction function by other proteins, including pannexins, are necessarily higher. Before accepting a gap junction function of alternate proteins, it has to be verified that the function is not due to connexins, which may be upregulated as a consequence of the experimental interventions. No effort has been made in this regard in the studies concluding a gap junction function of Panx1.

2.2. Panx1 is the elusive ATP release channel

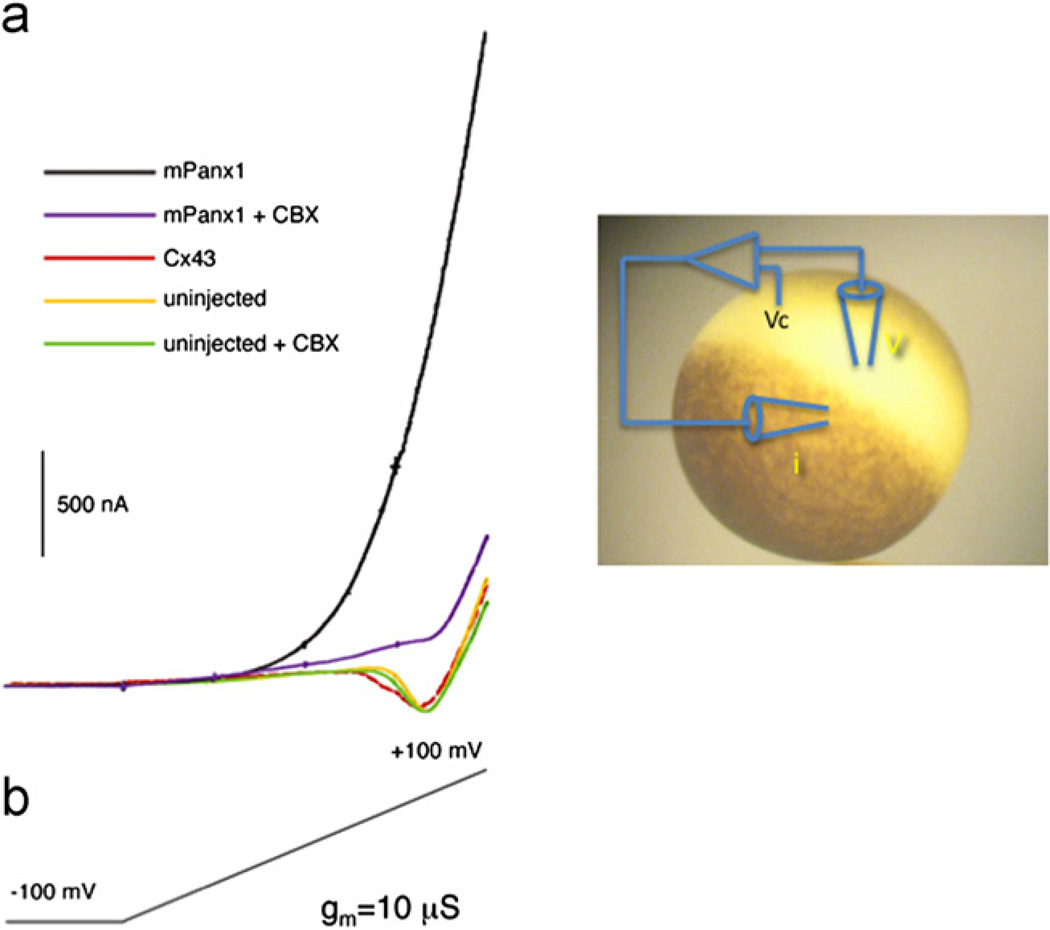

The first intimation what functional role Panx1 may play came from recordings from single cells (Bao et al., 2004; Bruzzone et al., 2003). When, as shown in Fig. 2, the membrane potential of oocytes is ramped from −100 to +100 mV, a robust outward current is present in Panx1 expressing cells but not in uninjected oocytes or in oocytes expressing connexin 43. The pannexin1 mediated current is suppressed by the channel blocker carbenoxolone (Bruzzone et al., 2005).

Fig. 2.

Membrane currents in single Xenopus oocytes. Single oocytes are voltage clamped and the membrane potential is ramped over a period of 70 s from −100 mV to +100 mV. Only Panx1 expressing oocytes exhibit robust outward currents that are sensitive to carbenoxolone (CBX). The inward current observed in uninjected oocytes is due to slowly activating sodium channels endogenous to oocytes (Baud et al., 1982).

Thus connexins, such as Cx43, form exclusively gap junctions and pannexins form exclusively channels on the free membrane surface of vertebrate cells. For reasons outlined previously (Dahl and Locovei, 2006) Panx1 channels should not be termed “hemichannel” and there is now general consensus that such a potentially confusing nomenclature should be avoided (Sosinsky et al., 2011).

In invertebrates gap junctions are formed by innexins, which have some sequence homology to the pannexins. It is now clear that innexins (or at least some of them) actually are bifunctional. In addition to gap junction channels, they also form non-junctional channels that are similar to pannexin channels (Bao et al., 2007; Luo and Turnbull, 2011; Samuels et al., 2010). These channels may be traced back to an ‘urchannel’ in single cell organisms, a protein that still needs to be identified.

Characterization of the pannexin1 channel showed that it is one of the largest channels in our body. Panx1 forms a channel with an unusual high number of conductance states and has a maximal conductance of 500 pS. The Panx1 channel is poorly selective and allows the transit of both negatively and positively charged molecules, including ATP and dyes such as YoPro and carboxyfluorescein (Bao et al., 2004; Locovei et al., 2006a; Pelegrin and Surprenant, 2006). The Panx1 channel can be activated by mechanical stress and by an increase in cytoplasmic calcium ion concentration (Bao et al., 2004; Locovei et al., 2006b). Furthermore, Panx1 channels can be activated by ATP via purinergic receptors (Locovei et al., 2006b, 2007). All these Panx1 channel activators are operative at the membrane resting potential in a regular ion environment and thus occur under physiological conditions. These Panx1 channel properties are characteristic for an ATP release channel that is involved in propagation of intercellular calcium waves. In tissues exhibiting intercellular calcium wave propagation such waves can be elicited by mechanical stimulation of individual cells, which then serve as wave origin (Charles et al., 1992; Demer et al., 1993; Sanderson et al., 1990). Thus, the ATP release mechanism has an inherent mechanosensitivity, whether or not this property is involved in the physiological wave activation mechanism. For example, to activate intercellular calcium waves among astrocytes in vivo, there is no need for mechanical strain to the head. The Panx1 channel fulfills this requirement of mechanosensitivity. Furthermore, its activation through purinergic receptors by ATP is consistent with an involvement as ATP release channel in wave propagation, allowing for a regenerative process of the wave.

It appears that Panx1 is expressed in all cells that release ATP through channels. A notable example is the peripheral vascular system, in which ATP release from erythrocytes is triggered by low oxygen or by shear stress (Bergfeld and Forrester, 1992). The released ATP binds to purinergic receptors on endothelial cells initiating a propagated calcium wave and ultimately leading to NO release from endothelial cells. The NO relaxes vascular smooth muscle thereby increasing blood flow and consequently oxygen supply. In this way, a peripheral control loop involving ATP regulates oxygen content of tissues. Panx1 is expressed at high levels in both erythrocytes and endothelial cells, which is consistent with an ATP release function of this protein (Locovei et al., 2006a). On the other hand, Panx1 has not been observed in the presynaptic membrane of neurons (Zoidl et al., 2007a), although this is a site of ATP release. However, ATP release from presynaptic membranes typically is by a vesicular mechanism, where ATP is released as a co-transmitter via an exocytotic mechanism (MacKenzie et al., 1982; Silinsky, 1975; Unsworth and Johnson, 1990; Wagner et al., 1978).

In some cell types ATP release is polar, i.e. it is limited to a fraction of the cell surface. For example in airway epithelial cells ATP release occurs exclusively at the apical membrane (Button et al., 2007; Okada et al., 2006). The released ATP controls the ciliary beating, which in turn mediates mucociliary clearance including the expulsion of inhaled dust particles. In airway epithelial cells Panx1 expression is exclusively found on the apical surface and thus its expression matches that of ATP release (Ransford et al., 2009).

Channel mediated ATP release is correlated with an uptake of extracellularly applied dye molecules that are small enough to pass through the channel (Hamann and Attwell, 1996; Leybaert et al., 2003). This correlation is so good, that dye uptake is an accepted surrogate measure for ATP release. Both positive and negative charged dyes have been used for this purpose. Panx1 channels are permeable to both cationic and anionic dyes in addition to their ATP permeability (Bao et al., 2004; Locovei et al., 2006a; Pelegrin and Surprenant, 2006). Thus the Panx1 channel has the proper characteristics for mediating ATP and correlated non-selective dye flux.

Further support for an ATP release function of Panx1 channels comes from studies in which Panx1 expression was knocked down or knocked-out. Reduction of Panx1 expression by RNA interference in astrocytes, and in airway epithelial cells attenuated ATP release from these cells and dye uptake by macrophages (Pelegrin and Surprenant, 2006; Ransford et al., 2009; Scemes et al., 2008). Elimination of Panx1 expression by gene knockout completely purged ATP release by macrophages (Qu et al., 2011) and attenuated ATP release from erythrocytes (Qiu et al., 2011). In erythrocytes of Panx1−/− mice a residual ATP release remains, which is not associated with dye uptake. Thus, it appears that erythrocytes have an alternate release pathway to Panx1. This alternate release mechanism has a different pharmacology than Panx1 in that it is inhibited by dipyridamole, a drug that does not affect Panx1 currents (Qiu et al., 2011).

The pharmacology of channel-mediated ATP release matches that of Panx1 channels. That includes not only known Panx1 inhibitors, but also compounds such as connexin mimetic peptides that were considered to be highly selective for other channels (Dahl, 2007; Wang et al., 2007). The list of drugs affecting both ATP release and Panx1 channels also includes probenecid and glibenclamide (Qiu et al., 2011; Silverman et al., 2008). Probenecid previously was exclusively known as a transport inhibitor and consequently its effect on ATP release was interpreted as evidence for a membrane transport mechanism. Glibenclamide aka glyburide is an antidiabetic drug that acts on ATP regulated potassium channels in the nanomolar range (Mikhailov et al., 2001; Sturgess et al., 1985). At orders of magnitude higher concentrations this drug also inhibits ATP release and the chloride channel CFTR, which led to the suggestion that CFTR is an ATP release channel (Schwiebert et al., 1995; Sheppard and Welsh, 1993). However, CFTR is not permeable to ATP, excluding such a function (Grygorczyk et al., 1996). Since probenecid and glibenclamide attenuate Panx1 channel currents, Panx1-mediated ATP release and dye uptake in the same concentration ranges (Qiu et al., 2011; Silverman et al., 2008) the drug effect on ATP release in various cell types is likely to be attributable to Panx1 as well.

Another argument for the ATP release function of Panx1 is the inhibition of its channel function by ATP (Qiu and Dahl, 2009). Counterintuitive as this may be, the channel inhibition by ATP represents a negative feedback control of a potentially deadly channel. Considering that the Panx1 channel is large and poorly selective, it is not surprising that persistent opening of the channel results in cell death (Bunse et al., 2011; Chekeni et al., 2010; Wang and Dahl, 2010). Furthermore, by its association with purinergic receptors (Locovei et al., 2006b, 2007; Pelegrin and Surprenant, 2006), Panx1 is part of a positive feedback loop allowing for ATP-induced ATP release. A suitable way to interrupt this perpetual circuit is a built in negative control of the ATP release channel. Indeed, amino acids within the extracellular vestibulum of the Panx1 channel mediate the effect of ATP and its analog BzATP on Panx1 channel currents and control of ATP release (Qiu et al., 2011). Intriguingly, P2X7R ligands, regardless of whether they act as agonists or antagonists at the receptor, inhibit Panx1 activity (Qiu and Dahl, 2009), confounding the interpretation of the effects of these compounds on ATP release (Suadicani et al., 2006).

If Panx1 is the ATP release channel, then mutations of Panx1 in strategic positions should alter ATP release. Indeed, removal of the negative feedback control of Panx1 by mutation of amino acids making up the putative ATP binding site in the Panx1 protein results in significantly increased ATP release (Qiu et al., 2011).

The Panx1 protein contains a carboxyterminal cysteine that is susceptible to thiol reaction (Wang and Dahl, 2010). Application of thiol reagents small enough to enter the channel, but also large enough to partially block the permeation pathway, not only attenuate Panx1 currents, but also inhibit Panx1-mediated ATP release. The same effect can be observed with a Panx1 mutant (Panx1 I60C, C426S) in which the terminal cysteine has been replaced by serine and with a cysteine replacing isoleucine in another position of the permeation pathway (Wang and Dahl, 2010). To be effective, the thiol reagents need to be applied to the open Panx1 channel. The inhibition of ATP release is significantly more pronounced than the effect on Panx1 currents, consistent with a partial block of the permeation pathway by the thiol reagent.

Taken together, the findings on Panx1 channels sum up to a dozen reasons why the Panx1 channel should be considered the prime candidate to represent the elusive ATP release channel. It is the convergence of independent lines of evidence that make the argument strong. In interpreting ATP release data in connection with Panx1 one has to consider that the Panx1 channel can change its properties by association with other proteins. For example, its pharmacology is altered by its co-expression with the potassium channel subunit Kvbeta3 (Bunse et al., 2009) so that the Panx1 channel inhibitors carbenoxolone and probenecid are essentially ineffective. Thus, if in a certain cell type probenecid or carbenoxolone do not affect ATP release, this does not by itself exclude a Panx1 involvement.

In addition to the “faux” gap junction proteins, pannexins, vertebrates also express connexins, which unequivocally serve a gap junction function. There is an abundance of literature that infers that connexins also function as undocked connexons (aka “hemichannels”). While “hemichannel “activity has been observed in expression systems for a small set of connexins such as Cx46, such activity is essentially undocumented under physiological conditions for Cx43 and Cx32, which are the subject of the over 200 publications speculating on physiological functions of connexin “hemichannels”. Moreover, connexins are not expressed in cells that do not form gap junctions, but exhibit channel mediated ATP release, such as erythrocytes. Furthermore, in cells with polar ATP release, such as airway epithelial cells, connexins are expressed where the gap junctions are located, i.e. the basolateral membrane, but not in the apical membrane, where ATP release takes place. Thus, connexin channels, in contrast to Panx1 channels, just do not measure up to fulfill rigorous requirements for a major ATP release channel. For additional arguments see Iglesias et al. (2009) and Scemes (2011).

2.3. Activation of Panx1 channels by ATP through purinergic receptors

Intercellular calcium wave propagation is mediated by two distinct mechanisms. Gap junctions formed by connexins allow the flux of second messengers including IP3 and thereby facilitate the spread of a calcium waves among contiguous cells (Sanderson et al., 1990). In a parallel pathway, the waves expand through release of ATP, which then activates purinergic receptors on neighboring, but not necessarily contiguous, cells (Guthrie et al., 1999; Osipchuk and Cahalan, 1992; Suadicani et al., 2003). For active wave propagation, the ATP release mechanism should be activated by ATP binding to the purinergic receptor. The Panx1 channel fulfills this criterion, because it is activated by extracellular ATP through purinergic receptors. Both the metabotropic P2Y receptors (Locovei et al., 2006b) and the ionotropic P2X7 receptor (Locovei et al., 2007) are capable of activating Panx1 channels. The P2Y receptors activate Panx1 probably by a receptor initiated rise in cytoplasmic calcium ions. Activation of Panx1 channels by ATP through P2X7 receptors does not require extracellular calcium and consequently influx of calcium. The P2X7 receptor co-immunoprecipitates with Panx1 and the activation mechanism thus may be by protein–protein interaction.

The P2X7R mediated activation of Panx1 leads to the uptake of extracellular dyes (Locovei et al., 2007; Pelegrin and Surprenant, 2006) and the appearance of a current that (in contrast to the P2X7R currents) is sensitive to Panx1 inhibitors (Iglesias et al., 2008; Locovei et al., 2007). Inexplicably, this current was not observed in the Pelegrin and Surprenant (2006) study. This led to the misguided notion that Panx1 is not a channel but a transporter even though a voltage activated Panx1 current was documented by these authors.

2.4. Panx1 and ATP-induced cell death

In macrophages, the application of extracellular ATP leads to different outcomes depending on the application modus of the P2X7R ligand. Brief application of ATP stimulates nonselective cation currents. The unitary conductance of the underlying channel is 10–30 pS (Ding and Sachs, 1999; Riedel et al., 2007). In contrast, repetitive or long lasting applications of ATP leads to the appearance of a large (440 pS) channel, the uptake of extracellular dyes and eventually to cell death (Schachter et al., 2008; Surprenant et al., 1996). Co-expression of P2X7R with Panx1 in Xenopus oocytes mimics these events (Locovei et al., 2007), including cell death. Although the large, unselective Panx1 channel is required, cell death by ATP apparently is not due to the run-down of gradients but occurs when the Panx1 channels are closing or even are closed, indicating that death is a result of signaling events downstream of Panx1.

Cell death in macrophages is an apoptotic/pyroptotic event. Why would oocytes undergo an apoptotic event by expression of just 2 surface proteins? The simple answer is that oocytes have the machinery. As a matter of quality control, most (up to 99%) of all oocytes never reach ovulation but instead die by apoptosis. As pointed out by Wessel (2010), it is therefore not surprising that the very first description of apoptosis was in oocyte maturation and reported as early as 1895 by Flemming. Apparently, this machinery can be hijacked by exogenous expression of Panx1 and P2X7R, that allow an alternate activation of the endogenous apoptotic mechanism to the physiological signal.

ATP-induced cell death is well documented, yet remains poorly understood. It is initiated by ATP binding to the P2X7 receptor and involves a set of proteins collectively called the inflammasome. The inflammasome mediates the innate immune response and includes proteins such as NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing proteins (NLRPs), apoptosis- associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) and caspase 1. The ultimate trigger for cell death is thought to be the cleavage of caspase 1 from a pro-form to the proteolytic cleavage products. In macrophages, ATP-induced cell death is thought to represent a last resort defense mechanism against bacteria such as mycobacteria tuberculosis, where the cell is sacrificed for proteolytic attack of the pathogen. However, inflammasome-mediated cell death has also been observed in astrocytes and neurons (de Rivero Vaccari et al., 2008).

In neurons and astrocytes the innate immune response is attenuated by an ASC neutralizing antibody (de Rivero Vaccari et al., 2009). This antibody also suppressed ATP-induced cell death in oocytes co-expressing P2X7R together with Panx1 (Silverman et al., 2009). Thus it is likely that these co-expressing oocytes undergo apoptosis/pyroptosis after prolonged exposure to ATP in a similar way as macrophages, neurons and astrocytes.

A link of Panx1 with the inflammasome is also indicated pharmacologically. Several drugs known to interfere with inflammasome activity also are inhibitors of Panx1 channels. Among them is Glyburide, also known as glibenclamide, which inhibits the inflammasome activation in the 10–100 µM range (Lamkanfi et al., 2009). Interestingly, Lamkanfi et al. (2009) tested the involvement of Panx1 in this process by assessing the effect of glyburide on the uptake of extracellularly applied dyes. Because no effect on this parameter was noticed it was concluded that glyburide did not affect Panx1. Direct measurement of Panx1 currents and of Panx1 mediated ATP release; however, have shown that Panx1 is a direct target for glyburide (Qiu et al., 2011). Panx1 currents are inhibited by glyburide with an IC50 of 45 µM, which is the same range in which the drug inhibits the inflammasome. For example Lamkanfi et al. (2009) used 200 µM glyburide for inhibition of the release of the cytokine IL-1β from macrophages. Thus dye uptake alone is not a sufficient measure of Panx1 activity. It is not a selective meter as dyes can enter cells through more than one pathway.

Glyburide is an antidiabetic drug acting on the SUR subunit of ATP-regulated potassium channels. The effect on potassium channels is exerted by nanomolar concentrations of the drug (Mikhailov et al., 2001; Sturgess et al., 1985). Nevertheless, in several publications the effect of micromolar glyburide on the innate immune response has been interpreted as evidence for K+ efflux triggering inflammasome activation (Gross et al., 2009; Muruve et al., 2008; Schroder et al., 2010). Since the effect on Panx1 channels occurs in the same high concentration range, the inhibition of the innate immune response thus may result from inhibition of Panx1 rather than an effect on potassium channels.

2.5. Panx1 is part of the inflammasome complex

It is evident that Panx1 is functionally linked to the P2X7 receptor. In addition, these proteins may also physically interact. Using over-expression of a myc-tagged Panx1 and a myc antibody for immunoprecipitation, the P2X7 receptor co-precipitates with Panx1 (Pelegrin and Surprenant, 2006). While it is possible that this interaction is an artifact of the expression system, it seems more likely that the interaction between the proteins is authentic. The P2X7 receptor also immunoprecipitates with the native Panx1 protein, using an anti-Panx1 antibody (Silverman et al., 2009). Immunoprecipitation of neuronal lysates with the Panx1 antibody in addition co-precipitates the inflammasome components NLRP1, ASC, caspase 1, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) and caspase 11. Thus there appears to be a direct protein association between the Panx1 and P2X7R proteins and a direct linkage between one or both of these proteins with the inflammasome complex.

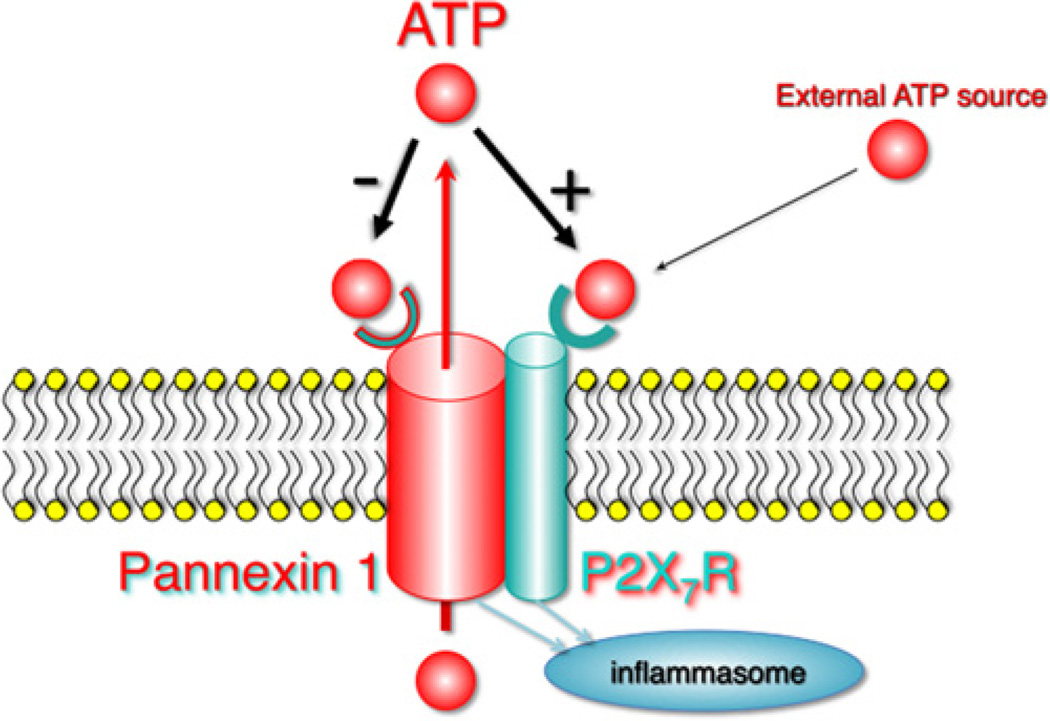

These observations suggest an activation scheme as shown in Fig. 3. ATP from an external source binds to and activates the P2X7R, which in turn activates Panx1. Panx1 channel activity results in the release of ATP thus triggering a positive feedback loop. As the concentration of ATP increases in the vicinity of the Panx1 pore, the low affinity binding site in Panx1 for ATP mediates channel closure. This mechanism prevents the activation mechanism going overboard with even the slightest increase in extracellular ATP. Activation of P2X7R and/or Panx1 launches inflammasome activity and cleavage of caspase 1 to the proteolytic form. The minimal involvement of Panx1 in this scheme is that of an amplification mechanism for the ATP signal. Therefore, it is not surprising that Panx1 is not required in experiments using 5mM extracellular ATP to activate the inflammasome. This concentration represents the highest ATP concentration that could be achieved if, by flux through Panx1 channels, the cytoplasmic ATP concentration could equilibrate with that in a small extracellular compartment. Thus the statement by Qu et al. (2011), that Panx1 is not required for inflammasome activation is misleading.

Fig. 3.

Activation of inflammasome and ATP feedback loops. Extracellular ATP binding to the P2X7 receptor activates Panx1 and ATP release. This ATP-induced ATP release is counteracted by inhibition of Panx1 channel activity by extracellular ATP. Activity of P2X7 and/or Panx1 leads to activation of caspase 1 through the inflammasome.

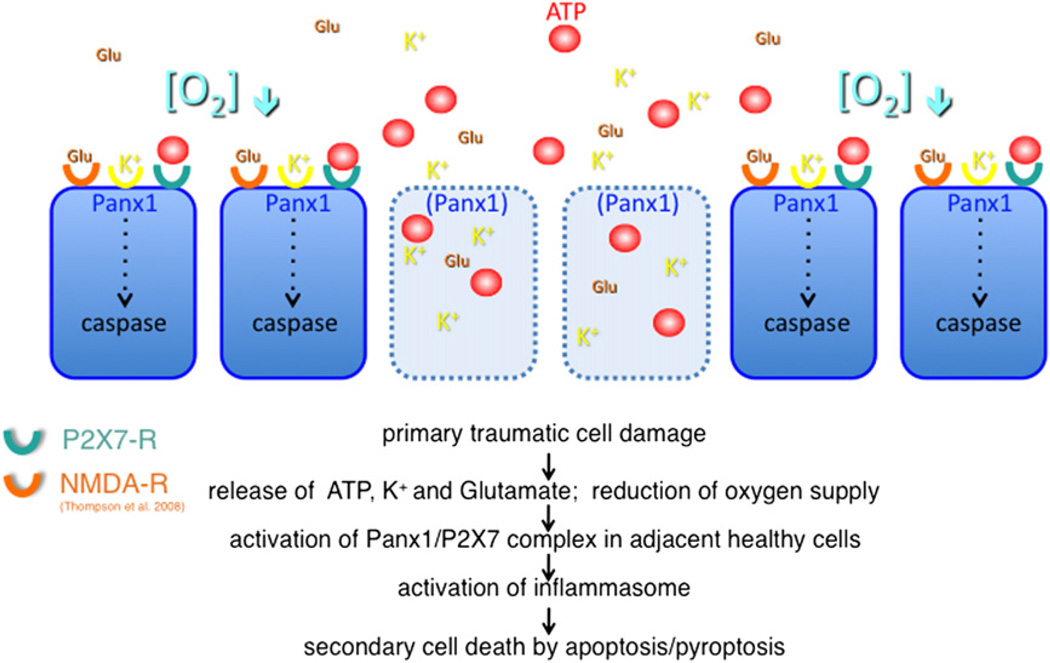

The negative feedback loop for ATP release through Panx1 channels prevents that weak ATP stimuli lead to excessive inflammasome activation and cell death. However, there are conditions in which this control mechanism may fail. When cells die due to trauma or stroke they release several compounds that all are stimuli of Panx1 channels. The compounds include ATP, potassium ions (Silverman et al., 2009) and glutamate (Thompson et al., 2008). In addition, low oxygen, as shown for erythrocytes (Locovei et al., 2006a; Sridharan et al., 2010) and neurons (Thompson et al., 2006), is a strong activator of Panx1. Thus, multiple stimuli converge to overstimulate this system and thus may not be suppressed by the negative feedback loop (Fig. 4). As a consequence, originally healthy cells in the vicinity of the primary lesion will die. This type of cell death is well known and is commonly referred to as ‘secondary cell death’. The lesion volume due to secondary cell death typically exceeds the original lesion several-fold. While the cells lost due to the primary lesion cannot be resurrected, secondary cell death is thus a therapeutic target. It can be expected that maximal benefits from this type of intervention will be gained if intervention can be supplied soon after the insult. Since secondary cell death extends over a period of several hours, there appears to be a therapeutic window of sufficient duration to limit the secondary lesion volume.

Fig. 4.

Secondary cell death. Injured cells release the Panx1 activators K+, ATP and glutamate. In addition, hypoxia resulting from ruptured or occluded blood vessels activates Panx1 channels in intact cells in the vicinity of the primary insult. The convergence of Panx1 stimuli may result in caspase 1 activation and eventually cell death secondary to the initial insult.

2.6. Panx1 inhibition by probenecid as a potential therapeutic approach to limit secondary cell death

For suppression of inflammation and associated secondary cell death, Panx1 should be the prime target for intervention for the following reasons: (1) Panx1 is involved in early events in inflammasome signaling, (2) Panx1 serves as an amplifier, (3) it is susceptible to stimulation by other stimuli not affecting the P2X7 receptor, such as K+, low oxygen and glutamate, (4) Panx1 is easily accessible to drugs, (5) The Panx1 inhibitor probenecid is available and has been used for decades to treat gouty arthritis with few side effects.

In cultured neurons or astrocytes inflammasome activation, as assayed by caspase 1 cleavage, is induced by treatment with high concentrations of extracellular potassium ions. This activation probably occurs by direct action of the potassium ions on the Panx1 protein because Panx1 channel activity is induced by extracellular potassium in the absence of voltage changes, i.e. under voltage clamp conditions and in the absence of transmembrane ion fluxes (Silverman et al., 2009). Caspase 1 activation is not observed in cells in which Panx1 expression is knocked down by RNA interference. Furthermore, the Panx1 channel inhibitor probenecid attenuates the caspase 1 cleavage in cultured neurons induced by extracellular potassium ions, further corroborating the involvement of Panx1 in inflammasome activation. The caspase 1 activation can also be attenuated by the P2X7R inhibitor brilliant blue G (BBG). Because BBG also inhibits Panx1 currents, it is not clear whether the effect on caspase 1 activation is attributable to blocking P2X7R, Panx1 or both. In a recent publication Nedergaard and coworkers (Peng et al., 2009) demonstrated that in a rat model of spinal cord injury the outcome was greatly improved when the rats received BBG soon after the injury. The BBG concentrations used in that study was high so it cannot be inferred whether the effect is attributable to inhibition of P2X7R, Panx1 or both.

Blocking Panx1 exclusively, however, may leave the P2X7R activation of the inflammasome untouched, when large amounts of ATP from external sources are available for receptor activation. Thus, a combination therapy, in which both Panx1 and P2X7 receptors are blocked, may be the best method of treatment.

Further support for a key role of Panx1 in neuronal cell death comes from a recent study on an animal model of Crohn’s disease (Gulbransen et al., 2012). The loss of enteric neurons in inflammatory bowel disease was found to be dependent of P2X7R, Panx1, ASC and caspase 1 in a similar way as shown in Fig. 3 and described previously for CNS neurons (Silverman et al., 2009). Inhibition of any of these proteins resulted in preservation of enteric neurons. Consistent with its effect on Panx1 channels, probenecid was one of the drugs to preserve neuronal integrity and sustaining gut motility in the in vivo study of enteric motor dysfunction (Gulbransen et al., 2012).

2.7. Panx1 and HIV infection

A surprising new development indicates that Panx1 channel activity may be involved in yet another clinical setting. Recently it has been discovered that a signaling cascade is required to render the T cell membrane fusogenic with the human immunodeficiency virus (Seror et al., 2011). It appears that the signaling is initiated by binding of the virus to its T cell receptor, leading to ATP release from the T cell. Extracellular ATP acting on purinergic receptors in the T cell membrane then leads to activation of a kinase, which in turn facilitates infection. Knockdown of candidate proteins and pharmacological data indicate that ATP release is mediated by Panx1, that the purinergic receptor is P2Y2 and that the kinase activity is exerted by Pyk2. Thus, Panx1 should be a preferred target for pharmacologically preventing HIV infection since it acts early in the signaling cascade as an amplification mechanism. Indeed, Seror et al. (2011) were successful in preventing HIV infection with the Panx1 inhibitors DIDS and SITS. Because of the poor selectivity of these drugs it can be expected that more specific inhibitors of the Panx1 channel will work even better.

3. Conclusion

Within the short time span since its discovery, the Panx1 protein has undergone a fast progression from a mis-annotated gene freak to a promising therapeutic target for such diverse diseases as stroke and AIDS. Although still annotated in gene databases as a gap junction forming protein, no evidence for such a function presently exists. On the contrary, strong evidence in several cell types excludes a gap junction function of Panx1. Instead it is now well established that Panx1 acts as an unpaired membrane channel allowing the flux of small ions and molecules across the plasma membrane. As such, Panx1 is the major ATP release channel providing an alternate mode of intercellular communication to gap junctions. As an ATP release channel, Panx1 is involved in diverse physiological functions, including peripheral regulation of oxygen supply and the innate immune response. By its interaction with other proteins, such as the P2X7 receptor and the inflammasome proteins, Panx1 may also signal beyond its channel function by protein–protein interaction. The latter function at present is speculative and requires experimental testing. Last but not least, it remains to be seen, whether the functional repertoire of Panx1 is limited to the presently known duties or whether it plays additional roles in physiological or pathological processes.

REFERENCES

- Bao L, Locovei S, Dahl G. Pannexin membrane channels are mechanosensitive conduits for ATP. FEBS Lett. 2004;572:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L, Samuels S, Locovei S, Macagno ER, Muller KJ, Dahl G. Innexins form two types of channels. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:5703–5708. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baud C, Kado RT, Marcher K. Sodium channels induced by depolarization of the Xenopus laevis oocyte. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1982;79:3188–3192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergfeld GR, Forrester T. Release of ATP from human erythrocytes in response to a brief period of hypoxia and hypercapnia. Cardiovasc. Res. 1992;26:40–47. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boassa D, Ambrosi C, Qiu F, Dahl G, Gaietta G, Sosinsky G. Pannexin1 channels contain a glycosylation site that targets the hexamer to the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:31733–31743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702422200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boassa D, Qiu F, Dahl G, Sosinsky G. Trafficking dynamics of glycosylated pannexin 1 proteins. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2008;15:119–132. doi: 10.1080/15419060802013885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R, Hormuzdi SG, Barbe MT, Herb A, Monyer H. Pannexins, a family of gap junction proteins expressed in brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:13644–13649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2233464100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzone R, Barbe MT, Jakob NJ, Monyer H. Pharmacological properties of homomeric and heteromeric pannexin hemichannels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J. Neurochem. 2005;92:1033–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunse S, Locovei S, Schmidt M, Qiu F, Zoidl G, Dahl G, Dermietzel R. The potassium channel subunit Kvbeta3 interacts with pannexin 1 and attenuates its sensitivity to changes in redox potentials. FEBS J. 2009;276:6258–6270. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunse S, Schmidt M, Hoffmann S, Engelhardt K, Zoidl G, Dermietzel R. Single cysteines in the extracellular and transmembrane regions modulate pannexin 1 channel function. J. Membr. Biol. 2011;244:21–33. doi: 10.1007/s00232-011-9393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button B, Picher M, Boucher RC. Differential effects of cyclic and constant stress on ATP release and mucociliary transport by human airway epithelia. J. Physiol. 2007;580:577–592. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles AC, Naus CC, Zhu D, Kidder GM, Dirksen ER, Sanderson MJ. Intercellular calcium signaling via gap junctions in glioma cells. J. Cell Biol. 1992;118:195–201. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chekeni FB, Elliott MR, Sandilos JK, Walk SF, Kinchen JM, Lazarowski ER, Armstrong AJ, Penuela S, Laird DW, Salvesen GS, Isakson BE, Bayliss DA, Ravichandran KS. Pannexin 1 channels mediate ‘find-me’ signal release and membrane permeability during apoptosis. Nature. 2010;467:863–867. doi: 10.1038/nature09413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl G, Miller T, Paul D, Voellmy R, Werner R. Expression of functional cell–cell channels from cloned rat liver gap junction complementary DNA. Science. 1987;236:1290–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.3035715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl G. The Xenopus oocyte cell–cell channel assay for functional analysis of gap junction proteins. In: Stevenson B, Gallin W, Paul D, editors. Cell–Cell Interactions. A Practical Approach. IRL, Oxford: 1992. pp. 143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl G, Werner R, Levine E, Rabadan-Diehl C. Mutational analysis of gap junction formation. Biophys. J. 1992;62:172–180. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81803-9. discussion 180-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl G, Locovei S. Pannexin: to gap or not to gap, is that a question? IUBMB Life. 2006;58:409–419. doi: 10.1080/15216540600794526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl G. Gap junction-mimetic peptides do work, but in unexpected ways. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2007;14:259–264. doi: 10.1080/15419060801891018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rivero Vaccari JP, Lotocki G, Marcillo AE, Dietrich WD, Keane RW. A molecular platform in neurons regulates inflammation after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:3404–3414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0157-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rivero Vaccari JP, Lotocki G, Alonso OF, Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD, Keane RW. Therapeutic neutralization of the NLRP1 inflammasome reduces the innate immune response and improves histopathology after traumatic brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1251–1261. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demer LL, Wortham CM, Dirksen ER, Sanderson MJ. Mechanical stimulation induces intercellular calcium signaling in bovine aortic endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:H2094–H2102. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.6.H2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding S, Sachs F. Single channel properties of P2X2 purinoceptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 1999;113:695–720. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.5.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross O, Poeck H, Bscheider M, Dostert C, Hannesschlager N, Endres S, Hartmann G, Tardivel A, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz V, Mocsai A, Tschopp J, Ruland J. Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature. 2009;459:433–436. doi: 10.1038/nature07965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grygorczyk R, Tabcharani JA, Hanrahan JW. CFTR channels expressed in CHO cells do not have detectable ATP conductance. J. Membr. Biol. 1996;151:139–148. doi: 10.1007/s002329900065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbransen BD, Bashashati M, Hirota SA, Gui X, Roberts JA, Macdonald JA, Muruve DA, McKay DM, Beck PL, Mawe GM, Thompson RJ, Sharkey KA. Activation of neuronal P2X7 receptor–pannexin-1 mediates death of enteric neurons during colitis. Nat. Med. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nm.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie PB, Knappenberger J, Segal M, Bennett MV, Charles AC, Kater SB. ATP released from astrocytes mediates glial calcium waves. J Neurosci. 1999;19:520–528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00520.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann M, Attwell D. Non-synaptic release of ATP by electrical stimulation in slices of rat hippocampus, cerebellum and habenula. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1996;8:1510–1515. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Grinspan JB, Abrams CK, Scherer SS. Pannexin1 is expressed by neurons and glia but does not form functional gap junctions. Glia. 2007;55:46–56. doi: 10.1002/glia.20435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias R, Locovei S, Roque A, Alberto AP, Dahl G, Spray DC, Scemes E. P2X7 receptor–Pannexin1 complex: pharmacology and signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C752–C760. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00228.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias R, Dahl G, Qiu F, Spray DC, Scemes E. Pannexin 1: the molecular substrate of astrocyte “hemichannels”. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:7092–7097. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6062-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CP, Bechberger JF, Thompson RJ, MacVicar BA, Bruzzone R, Naus CC. Tumor-suppressive effects of pannexin 1 in C6 glioma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1545–1554. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M, Mueller JL, Vitari AC, Misaghi S, Fedorova A, Deshayes K, Lee WP, Hoffman HM, Dixit VM. Glyburide inhibits the Cryopyrin/Nalp3 inflammasome. J. Cell Biol. 2009;187:61–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leybaert L, Braet K, Vandamme W, Cabooter L, Martin PE, Evans WH. Connexin channels, connexin mimetic peptides and ATP release. Cell Commun. Adhes. 2003;10:251–257. doi: 10.1080/cac.10.4-6.251.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locovei S, Bao L, Dahl G. Pannexin 1 in erythrocytes: function without a gap. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006a;103:7655–7659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601037103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locovei S, Wang J, Dahl G. Activation of pannexin 1 channels by ATP through P2Y receptors and by cytoplasmic calcium. FEBS Lett. 2006b;580:239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locovei S, Scemes E, Qiu F, Spray DC, Dahl G. Pannexin1 is part of the pore forming unit of the P2X7 receptor death complex. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo K, Turnbull MW. Characterization of nonjunctional hemichannels in caterpillar cells. J. Insect. Sci. 2011;11:6. doi: 10.1673/031.011.0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie I, Burnstock G, Dolly JO. The effects of purified botulinum neurotoxin type A on cholinergic, adrenergic and non-adrenergic, atropine-resistant autonomic neuromuscular transmission. Neuroscience. 1982;7:997–1006. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhailov MV, Mikhailova EA, Ashcroft SJ. Molecular structure of the glibenclamide binding site of the beta-cell K(ATP) channel. FEBS Lett. 2001;499:154–160. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02538-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muruve DA, Petrilli V, Zaiss AK, White LR, Clark SA, Ross PJ, Parks RJ, Tschopp J. The inflammasome recognizes cytosolic microbial and host DNA and triggers an innate immune response. Nature. 2008;452:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature06664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada SF, Nicholas RA, Kreda SM, Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC. Physiological regulation of ATP release at the apical surface of human airway epithelia. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:22992–23002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603019200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osipchuk Y, Cahalan M. Cell-to-cell spread of calcium signals mediated by ATP receptors in mast cells. Nature. 1992;359:241–244. doi: 10.1038/359241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchin Y, Kelmanson I, Matz M, Lukyanov K, Usman N, Lukyanov S. A ubiquitous family of putative gap junction molecules. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:R473–R474. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00576-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegrin P, Surprenant A. Pannexin-1 mediates large pore formation and interleukin-1 beta release by the ATP-gated P2X7 receptor. EMBO J. 2006;25:5071–5082. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W, Cotrina ML, Han X, Yu H, Bekar L, Blum L, Takano T, Tian GF, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Systemic administration of an antagonist of the ATP-sensitive receptor P2X7 improves recovery after spinal cord injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12489–12493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902531106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penuela S, Bhalla R, Gong XQ, Cowan KN, Celetti SJ, Cowan BJ, Bai D, Shao Q, Laird DW. Pannexin 1 and pannexin 3 are glycoproteins that exhibit many distinct characteristics from the connexin family of gap junction proteins. J. Cell. Sci. 2007;120:3772–3783. doi: 10.1242/jcs.009514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu F, Dahl G. A permeant regulating its permeation pore: inhibition of pannexin 1 channels by ATP. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C250–C255. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00433.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu F, Wang J, Spray DC, Scemes E, Dahl G. Two non-vesicular ATP release pathways in the mouse erythrocyte membrane. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:3430–3435. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, Misaghi S, Newton K, Gilmour LL, Louie S, Cupp JE, Dubyak GR, Hackos D, Dixit VM. Pannexin-1 is required for ATP release during apoptosis but not for inflammasome activation. J. Immunol. 2011;186:6553–6561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransford GA, Fregien N, Qiu F, Dahl G, Conner GE, Salathe M. Pannexin 1 contributes to ATP release in airway epithelia. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2009;41:525–534. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0367OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedel T, Lozinsky I, Schmalzing G, Markwardt F. Kinetics of P2X7 receptor-operated single channels currents. Biophys J. 2007;92:2377–2391. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.091413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels SE, Lipitz JB, Dahl G, Muller KJ. Neuroglial ATP release through innexin channels controls microglial cell movement to a nerve injury. J. Gen. Physiol. 2010;136:425–442. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson MJ, Charles AC, Dirksen ER. Mechanical stimulation and intercellular communication increases intracellular Ca2+ in epithelial cells. Cell Regul. 1990;1:585–596. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.8.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E, Suadicani SO, Dahl G, Spray DC. Connexin and pannexin mediated cell–cell communication. Neuron Glia Biol. 2008;3:199–208. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X08000069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scemes E. Nature of plasmalemmal functional “hemichannels”. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter J, Motta AP, de Souza Zamorano A, da Silva-Souza HA, Guimaraes MZ, Persechini PM. ATP-induced P2X7-associated uptake of large molecules involves distinct mechanisms for cations and anions in macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:3261–3270. doi: 10.1242/jcs.029991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K, Zhou R, Tschopp J. The NLRP3 inflammasome: a sensor for metabolic danger? Science. 2010;327:296–300. doi: 10.1126/science.1184003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwiebert EM, Egan ME, Hwang TH, Fulmer SB, Allen SS, Cutting GR, Guggino WB. CFTR regulates outwardly rectifying chloride channels through an autocrine mechanism involving ATP. Cell. 1995;81:1063–1073. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seror C, Melki MT, Subra F, Raza SQ, Bras M, Saidi H, Nardacci R, Voisin L, Paoletti A, Law F, Martins I, Amendola A, Abdul-Sater AA, Ciccosanti F, Delelis O, Niedergang F, Thierry S, Said-Sadier N, Lamaze C, Metivier D, Estaquier J, Fimia GM, Falasca L, Casetti R, Modjtahedi N, Kanellopoulos J, Mouscadet JF, Ojcius DM, Piacentini M, Gougeon ML, Kroemer G, Perfettini JL. Extracellular ATP acts on P2Y2 purinergic receptors to facilitate HIV-1 infection. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1823–1834. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard DN, Welsh MJ. Inhibition of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator by ATP-sensitive K+ channel regulators. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993;707:275–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb38058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silinsky EM. On the association between transmitter secretion and the release of adenine nucleotides from mammalian motor nerve terminals. J. Physiol. 1975;247:145–162. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp010925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Locovei S, Dahl G. Probenecid, a gout remedy, inhibits pannexin 1 channels. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C761–C767. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00227.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WR, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Locovei S, Qiu F, Carlsson SK, Scemes E, Keane RW, Dahl G. The pannexin 1 channel activates the inflammasome in neurons and astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:18143–18151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.004804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosinsky GE, Boassa D, Dermietzel R, Duffy HS, Laird DW, Macvicar B, Naus CC, Penuela S, Scemes E, Spray DC, Thompson RJ, Zhao HB, Dahl G. Pannexin channels are not gap junction hemichannels. Channels (Austin) 2011;5:193–197. doi: 10.4161/chan.5.3.15765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan M, Adderley SP, Bowles EA, Egan TM, Stephenson AH, Ellsworth ML, Sprague RS. Pannexin 1 is the conduit for low oxygen tension-induced ATP release from human erythrocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010;299:H1146–H1152. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00301.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgess NC, Ashford ML, Cook DL, Hales CN. The sulphonylurea receptor may be an ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Lancet. 1985;2:474–475. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suadicani SO, De Pina-Benabou MH, Urban-Maldonado M, Spray DC, Scemes E. Acute downregulation of Cx43 alters P2Y receptor expression levels in mouse spinal cord astrocytes. Glia. 2003;42:160–171. doi: 10.1002/glia.10197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suadicani SO, Brosnan CF, Scemes E. P2X7 receptors mediate ATP release and amplification of astrocytic intercellular Ca2+ signaling. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:1378–1385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3902-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surprenant A, Rassendren F, Kawashima E, North RA, Buell G. The cytolytic P2Z receptor for extracellular ATP identified as a P2X receptor (P2X7) Science. 1996;272:735–738. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RJ, Zhou N, MacVicar BA. Ischemia opens neuronal gap junction hemichannels. Science. 2006;312:924–927. doi: 10.1126/science.1126241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RJ, Jackson MF, Olah ME, Rungta RL, Hines DJ, Beazely MA, MacDonald JF, MacVicar BA. Activation of pannexin-1 hemichannels augments aberrant bursting in the hippocampus. Science. 2008;322:1555–1559. doi: 10.1126/science.1165209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth CD, Johnson RG. Acetylcholine and ATP are coreleased from the electromotor nerve terminals of Narcine brasiliensis by an exocytotic mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:553–557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Abeele F, Bidaux G, Gordienko D, Beck B, Panchin YV, Baranova AV, Ivanov DV, Skryma R, Prevarskaya N. Functional implications of calcium permeability of the channel formed by pannexin 1. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:535–546. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200601115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JA, Carlson SS, Kelly RB. Chemical and physical characterization of cholinergic synaptic vesicles. Biochemistry. 1978;17:1199–1206. doi: 10.1021/bi00600a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ma M, Locovei S, Keane RW, Dahl G. Modulation of membrane channel currents by gap junction protein mimetic peptides: size matters. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1112–C1119. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00097.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Dahl G. SCAM analysis of Panx1 suggests a peculiar pore structure. J. Gen. Physiol. 2010;136:515–527. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb BA, Strand MR, Dickey SE, Beck MH, Hilgarth RS, Barney WE, Kadash K, Kroemer JA, Lindstrom KG, Rattanadechakul W, Shelby KS, Thoetkiattikul H, Turnbull MW, Witherell RA. Polydnavirus genomes reflect their dual roles as mutualists and pathogens. Virology. 2006;347:160–174. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner R, Miller T, Azarnia R, Dahl G. Translation and functional expression of cell–cell channel mRNA in Xenopus oocytes. J. Membr. Biol. 1985;87:253–268. doi: 10.1007/BF01871226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel GM. The apoptotic oocyte. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2010;77 doi: 10.1002/mrd.21172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoidl G, Petrasch-Parwez E, Ray A, Meier C, Bunse S, Habbes H-W, Dahl G, Dermietzel R. Localization of the Pannexin1 protein at postsynaptic sites in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2007a;146:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]