Abstract

We recently reported that the latency to begin drinking water during slow, intravenous infusion of a concentrated NaCl solution was shorter in estradiol-treated ovariectomized rats compared to oil vehicle-treated rats, despite comparably elevated plasma osmolality. To test the hypothesis that the decreased latency to begin drinking is attributable to enhanced detection of increased plasma osmolality by osmoreceptors located in the CNS, the present study used immunocytochemical methods to label fos, a marker of neural activation. Increased plasma osmolality did not activate the subfornical organ (SFO), organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (OVLT), or the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) in either oil vehicle-treated ratsor estradiol-treated rats. In contrast, hyperosmolality increased fos labeling in the area postrema (AP), the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) and the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) in both groups; however, the increase was blunted in estradiol-treated rats. These results suggest that estradiol has selective effects on the sensitivity of a population of osmo-/Na+-receptors located in the AP, which, in turn, alters activity in other central areas associated with responses to increased osmolality. In conjunction with previous reports that hyperosmolality increases blood pressure and that elevated blood pressure inhibits drinking, the current findings of reduced activation in AP, PVN, and RVLM–areas involved in sympathetic nerve activity–raise the possibility that estradiol blunts HS-induced blood pressure changes. Thus, estradiol may eliminate or reduce the initial inhibition of water intake that occurs during increased osmolality, and facilitate a more rapid behavioral response, as we observed in our recent study.

Keywords: Circumventricular organs, Area postrema, Paraventricular nucleus, Rostral ventrolateral medulla, Nucleus of the solitary tract, Osmolality

1. Introduction

Estrogen is a steroid hormone that is critical for reproductive behavior in females; however, effects of steroid hormones beyond those related to reproduction are increasingly being investigated. Reproductive hormones have been implicated in the control of body fluid balance in females of numerous species including humans and rodents [2,50,51]. More specifically, estrogens influence physiological processes related to body fluid balance, such as the regulation of blood pressure [27,28,37,57] and basal levels of the antidiuretic hormone, vasopressin (VP), as well as the release of VP stimulated by increased plasma osmolality (pOsm) [2,5,15,16,21]. Although behavioral responses to volume stimuli also are affected by estradiol [33–35], water intake stimulated by hyperosmolality was initially thought not to be influenced by estradiol, as ip or sc injection of hypertonic saline elicited drinking that appeared to be unaffected by estradiol ([33,34]; but see [58]). However, a recent study from our laboratory [30] showed that estradiol treatment of ovariectomized rats reduces the latency to begin drinking water during slow, intravenous (iv) infusion of a concentrated NaCl solution. The difference in the latency to begin drinking during hypertonic saline (HS) infusion is not secondary to a greater degree of hyperosmolality in estradiol-treated rats but, instead, appears to be due to enhanced sensitivity to more modest increases in pOsm. Thus, for water intake, as well as for VP release, estrogens may restore the sensitivity to hyperosmolality that was blunted by ovariectomy. Interestingly, estradiol effects on stimulated water intake are specific to increased pOsm, as prevention of osmotic dilution produced by water intake does not alter drinking [30].

Estradiol-mediated changes in behavior suggest changes in CNS activity. The idea that estrogens have central actions which influence compensatory responses to body fluid challenges also is supported by previous findings that estrogens alter hyperosmolality-induced increases in VP and oxytocin (OT) release from neuroendocrine neurons in the supraoptic nucleus (SON) and paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus. Clearly, to achieve the altered CNS output that underlies behavioral and physiological responses, perturbations of body fluid balance first must be detected by the CNS. This function is executed, in part, by circumventricular organs (CVOs), specialized central structures with an incomplete blood–brain-barrier that facilitates monitoring of peripheral osmolality. In fact, highly sensitive osmoreceptors have been localized to CVOs in the forebrain (sub-fornical organ, SFO; organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis, OVLT) and hindbrain (area postrema, AP) [4,8,38,59]. In addition, neural afferents from visceral osmoreceptors terminate in the hind-brain nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) [1,31,43]. Thus, hyperosmolality may be detected by any of these central nuclei, all of which are rich in estrogen receptors (ERs) [39,47,49] and project to CNS areas implicated in body fluid balance [9,11,45,46,55,56]. We, therefore, hypothesized that the decreased latency to begin drinking in response to iv HS observed in our previous study was attributable to estradiol-mediated alterations in CNS sensitivity to increased pOsm. Specifically, we hypothesized that estrogens enhance detection of increased pOsm by the CNS.

Accordingly, we assessed the effect of estradiol on neural activation in central areas that are associated with the detection of hyperosmolality. We used immunocytochemical methods to label for fos, the protein product of the immediate early gene c-fos, as a marker of neural activation in the SFO, OVLT, and AP, and in the NTS. Importantly, ERs are located in virtually all CNS areas implicated in body fluid balance [25,39,47–49,52]. Thus, the central effects of estradiol to alter physiological or behavioral responses to hyperosmolality may also—or instead—include actions at ERs on neurons in central areas ‘downstream’ from those associated with detecting changes in peripheral osmolality. Therefore, we also examined neural activation in central areas that receive input from the SFO, OVLT, AP, and NTS [9,11,45,46,55,56]. Given the elevated blood pressure and increased sympathetic nerve activity in response to hyperosmolality [3,22,53], along with the stimulation of VP and oxytocin release, this study focused on the PVN, the site of ‘preautonomic neurons’, the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), the hindbrain sympathoexcitatory area, the caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM), the hindbrain sympathoinhibitory area, and the SON, the site of neurosecretory VP and oxytocin neurons.

2. General methods

2.1. Animals

Adult female Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 225–325 g were used in these experiments. Animals were individually housed in plastic cages and given ad libitum access to Harlan rodent diet (no. 2018) and deionized water except as noted. Rats were maintained in a temperature-controlled room (21–25 °C) on a 12:12 light/dark cycle with lights on at 7:00 AM. All procedures were approved by the Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Ovariectomy and femoral catheters

Under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia (50 mg/kg body weight IP; Sigma-Aldrich), rats were bilaterally ovariectomized (OVX) using a ventral approach. Seven to ten days later, OVX rats again were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and chronic, indwelling catheters consisting of PE-50 tubing fused to PE-10 tubing were inserted into the femoral vein. Tubing was filled with 0.15 mL of heparinized 0.15 M NaCl (1000 U/mL) and plugged. The end of the catheter was tunneled subcutaneously to exit at the back of the neck.

2.3. Estrogen replacement

Twenty four hours after implantation of femoral venous catheters, OVX rats were given subcutaneous injections of 17-B-estradiol-3-benzoate (EB, Fisher Scientific; 10 μg/0.1 mL sesame oil) or the vehicle (OIL; 0.1 mL sesame oil) on a schedule that mimics patterns of estrogen fluctuations during the estrous cycle. Specifically, rats were given EB or OIL daily for two consecutive days and were tested two days after the second injection (i.e. on day 4). Previous work [62] showed that this estradiol replacement protocol produces circulating plasma levels of estradiol at the time of testing that are comparable to those at estrus; moreover, we and others have used this approach with reliable and replicable results [13,18,20,34,35] including in our study of EB effects on water intake stimulated by iv HS infusion [30]. Rats were weighed on both days of EB/OIL treatment and on the day of the test.

2.4. Intravenous (iv) infusions

During both of the two days of EB/OIL injections, OVX rats were adapted to testing procedures (approximately 60 min/day) by connecting the catheters to tubing attached to an infusion pump. On day 4, catheters were connected to the infusion pump and rats were infused intravenously with 2.0 M NaCl (HS) or 0.15 M NaCl (ISO). Based on the results of our previous study in which EB-treated OVX rats began to drink water after 15 min [30], rats were infused with HS or ISO at 35 μL/min for 15 min. Neither food nor water was available during the infusion.

2.5. Perfusion, blood and brain collection

Seventy-five minutes after the 15 min infusion, rats were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (0.2 mL) through the femoral venous catheter. Blood was collected from the heart and retained on ice until centrifugation for plasma protein concentration (using a refractometer; Reichert) and plasma sodium concentration (using ISE; Easylyte). Separate aliquots were drawn into microcapillary tubes and centrifuged for determination of hematocrit. Animals then were perfused through the heart with 0.15 M NaCl followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and then placed in a 30% sucrose solution for cryoprotection. Brains were sectioned coronally on a cryostat (Leica) at 40 μm in a 1:3 series and stored in cryoprotectant [61] at −20 °C until processed.

2.6. Immunolabeling

2.6.1. fos

fos immunoreactivity was demonstrated using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase technique. Briefly, one series of free-floating sections from each rat was rinsed in 0.05 M Tris–NaCl, soaked in 0.5% H2O2 for 30 min, rinsed again, and then soaked in 10% normal goat serum (NGS) for 60 min before being incubated in the fos primary antibody (Santa Cruz SC-52, rabbit anti c-fos, diluted 1:30,000 in 2% NGS) at 4 °C overnight. Sections then were rinsed and incubated in a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Vector Laboratories BA 1000, diluted 1:300 in 2% NGS) for 2 h at room temperature. Sections were rinsed again with 2% NGS and Tris–NaCl, and then soaked in an avidin–biotin solution (Vectastain Elite ABC kit) for 90 min. They were rinsed again with Tris–NaCl and then treated with H2O2 with nickel-intensified diaminobenzidine (Peroxidase substrate kit, SK-4100; Vector Laboratories) as the chromogen for 10–15 min. This reaction was terminated with multiple rinses in 0.05 M Tris– NaCl.

2.6.2. fos +DBH

As an initial effort to identify the phenotype of activated neurons in the RVLM, we focused on norepinephrine (NE). A subset of hind-brain sections was double immunolabeled for fos and dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH), an enzyme involved in NE biosynthesis, as a marker for NE-containing neurons, as described [10,13]. Briefly, after processing for fos immunolabeling, sections were incubated in the DBH primary antibody (mouse anti-DBH; Chemicon; diluted 1:1000 in 2% NGS) for 48 h at 4 °C. DBH immunolabeling was visualized by incubating in a Cy2-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch; diluted 1:300 in 2% NGS) for 6 h at room temperature. Sections were rinsed in 2% NGS, and in 0.05 M Tris– NaCl, then mounted on microscope slides and coverslipped using Cytoseal 60 (Fisher Scientific).

2.7.Quantification of immunoreactivity

For each brain, sections were ordered, mounted on gelatinized slides, and allowed to dry overnight. Sections then were dehydrated in an ascending series of alcohols (70%, 95%, and 100% EtOH) and xylenes before coverslipping. Sections were examined using a Nikon microscope equipped with a camera and NIS-Elements AR 2.30 software.

2.7.1. fos

For each rat, the number of fos-immunoreactive (fos-IR) neurons was counted in 2–3 matched, representative sections from the SFO, OVLT, AP, NTS, SON, PVN, CVLM, and RVLM, determined based on neuroanatomical landmarks (see [35] for details) and coordinates as described by Paxinos and Watson [40]. Specifically, AP sections were examined at caudal, middle, and rostral levels (− 14.08 to − 13.68 mm from Bregma). In the NTS, two representative sections were examined from the portion caudal to the AP (cNTS; − 14.50 to − 14.10 mm from Bregma) and three representative sections were examined from the middle portion (mNTS; − 14.08 to − 13.68 mm from Bregma) corresponding to caudal, middle, and rostral AP. The number of fos-IR neurons was evaluated in the OVLT (3 sections, 0.00 to 0.48 mm from Bregma), SFO (3 sections, − 1.60 to − 0.80 mm from Bregma), SON (3 sections, −2.12 to −0.80 mm from Bregma), PVN (3 sections, −2.12 to −0.92 mm from Bregma), CVLM (3 sections, − 14.60 to − 14.08 mm from Bregma), and RVLM (3 sections, − 12.80 to − 11.80 mm from Bregma). Counts from SFO, OVLT, AP, and NTS were taken bilaterally; counts from SON, PVN, CVLM, and RVLM were taken from one side. Counts from each area were averaged for each rat, and group means for each area (OIL-ISO: n=5; EB-ISO: n=5; OIL-HS: n=7; EB-HS: n=6–7) were calculated from the averaged counts.

2.7.2. fos+DBH

The RVLM was identified as described above and NIS Elements software was used to overlay brightfield (fos-IR neurons) and fluorescent (DBH-IR neurons) images. Double-labeled neurons thus appeared as cells with bright green cytoplasmic labeling with dark brown/black nuclear staining (Fig. 8). For each rat, the number of fos-IR neurons and the number of double-labeled neurons (fos-IR+DBH-IR) were quantified in 2–3 sections, and the percentage of fos-IR neurons that was double labeled in each section was calculated. Counts and percentages were averaged for each rat; group means (OIL-ISO: n=4; EB-ISO: n=5; OIL-HS: n=5; EB-HS: n=6) were calculated from the averages.

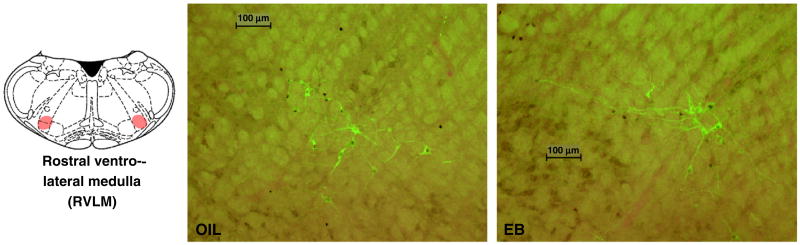

Fig. 8.

Line drawing (right; adapted from [40]) illustrating the location of the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM; red highlighting). Digital photomicrographs of the RVLM from OIL- (middle) and EB- (right) treated rats after HS infusion showing neurons labeled for fos (dark brown-black nuclear accumulation) and dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH; bright green cytoplasmic accumulation), and neurons double-labeled for fos and DBH. These images were obtained by overlaying brightfield and darkfield images. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. Photomicrographs were adjusted for brightness and contrast.

2.8. Statistics

All data are shown as group means±SEs. Statistica software (StatSoft) was used for statistical analyses. Body weight was analyzed using a 2-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with hormone (EB or OIL) and time as factors, repeated for time. Hematocrit, plasma protein concentration, plasma sodium concentration, and numbers of fos-IR neurons and of double-labeled neurons were analyzed using a 2-way ANOVA with hormone (EB or OIL) and infusion (HS or ISO) as factors. Significant main effects or interactions were examined using LSD tests; specific planned comparisons were made using Bonferroni corrections.

3. Results

3.1. Body weight and blood measures

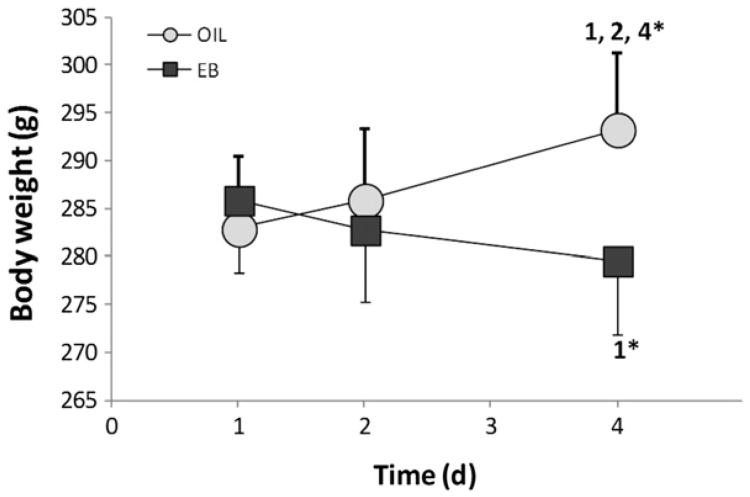

Body weight of OVX rats (Fig. 1) changed during the 4-day hormone treatment protocol and the direction of the change depended on hormone treatment [F(2,44)=18.64, p<0.001]. Pairwise comparisons of the interaction revealed that OIL-treated rats gained weight from day 1 to day 4 (p<0.001), whereas EB-treated rats lost weight (p<0.01). As a result, OIL-treated rats weighed significantly more than did EB-treated rats on day 4 (p<0.001).

Fig. 1.

Body weight (g) of OIL- (gray circles) and EB- (black circles) treated rats during the 4-day protocol. Weight depended upon the interaction between hormone and time (F(2,44)=18.63, p<0.001), with weight of OIL-treated rats increasing during the protocol, while weight of EB-treated rats decreased. 1=significantly greater than OIL day 1 (p<0.001); 2=significantly greater than OIL day 2 (p<0.001); 4*=significantly greater than EB day 4 (p<0.001); 1*=significantly less than EB day 1 (p<0.01).

Plasma Na+ concentration (Table 1) was increased after iv HS infusion [F(1,18)=16.77, p<0.001], but there was no difference between hormone treatments, and no interaction between hormone and infusion. Neither plasma protein nor hematocrit (Table 1) was altered by hormone treatment or by infusion.

Table 1.

Hematocrit, plasma protein concentration, and plasma Na+ concentration in OIL- and EB-treated rats after iv infusion of 0.15 M NaCl (ISO) or 2 M NaCl (HS). There was no effect of hormone treatment for any measure; however, plasma Na+ concentration increased after iv HS.

| Hematocrit (%) | Plasma protein (g/dL) | Plasma Na+* (mOsm/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OIL-ISO | 32.8 ±0.7 | 5.6 ±0.1 | 149.7 ±0.9 |

| OIL-HS | 34.7 ±1.8 | 5.5 ±0.1 | 152.5 ±0.6 |

| EB-ISO | 33.7 ±1.5 | 5.7 ±0.1 | 150.7 ±0.3 |

| EB-HS | 35.4 ±1.2 | 6.0 ±0.2 | 152.0 ±0.4 |

Significant effect of infusion F(1,18)=16.77, p<0.001.

3.2. Immunolabeling

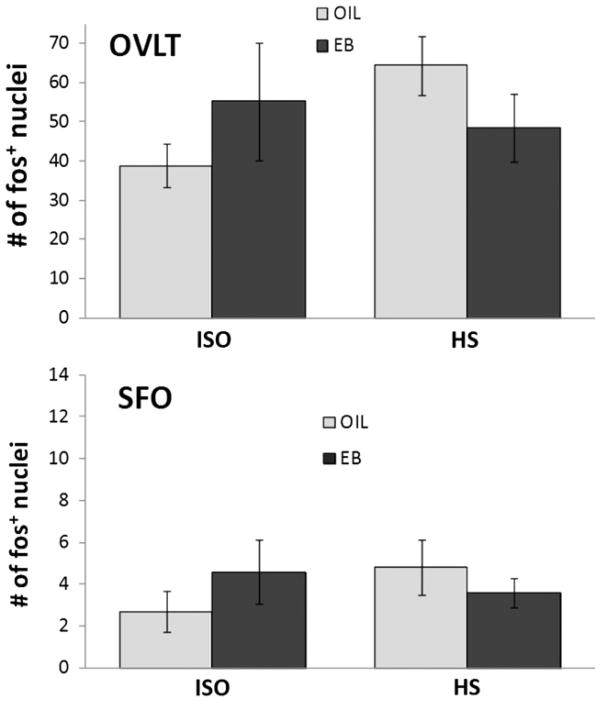

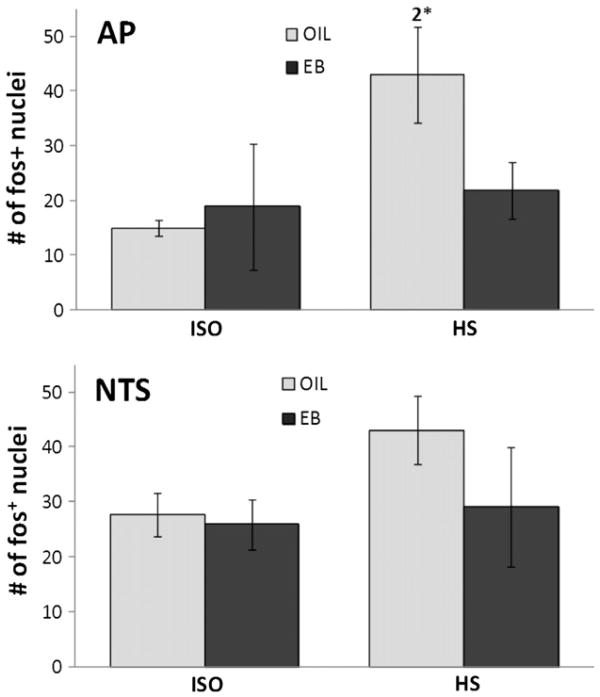

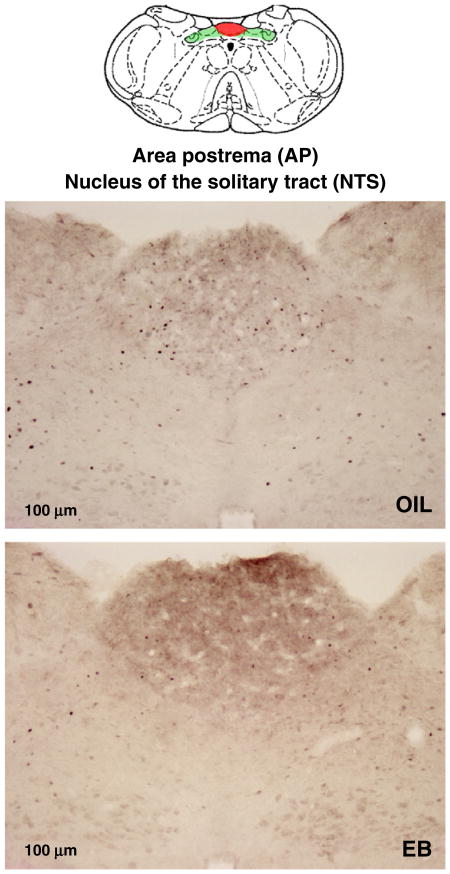

There was no effect of HS infusion on the number of fos-IR neurons in forebrain CVOs (OVLT or SFO; Fig. 2), nor was the number of fos-IR neurons in the NTS affected by HS infusion (Figs. 3, 4). Relatively high variability may have precluded detecting effects of HS infusion on the number of fos-IR neurons in the hindbrain CVO (AP). Accordingly, planned comparisons of the AP after HS infusion were conducted and revealed significantly greater number of fos-IR neurons in OIL-treated rats compared to that in EB-treated rats (Figs. 3, 4; p<0.05).

Fig. 2.

Number of neurons labeled for fos (fos+ neurons) in the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (OVLT; top) and the subfornical organ (SFO; bottom) of OIL-(gray bars) and EB- (black bars) treated rats after iv infusion of 0.15 M NaCl (ISO; left bars) or 2 M NaCl (HS; right bars). The number of fos+ neurons was not affected by hormone condition or infusion in either area.

Fig. 3.

Number of fos+ neurons in the area postrema (AP; top) and the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS; bottom) of OIL- (gray bars) and EB- (black bars) treated rats after iv infusion of ISO (left bars) or HS (right bars). The number of fos+ neurons in the NTS was not affected by hormone condition or infusion. In contrast, the number of fos+ neurons in the AP of OIL-treated rats after HS infusion was significantly greater than that in the AP of EB-treated rats (2*=significantly greater than EB-HS; p<0.05; planned comparison with Bonferroni correction).

Fig. 4.

Line drawing (top; adapted from [40]) illustrating the location of the area postrema (AP; red highlighting) and the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS; green highlighting). Digital photomicrographs from OIL- (middle) and EB- (bottom) treated rats after iv HS infusion showing fos+ neurons in the AP and NTS. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. Photomicrographs were adjusted for brightness and contrast.

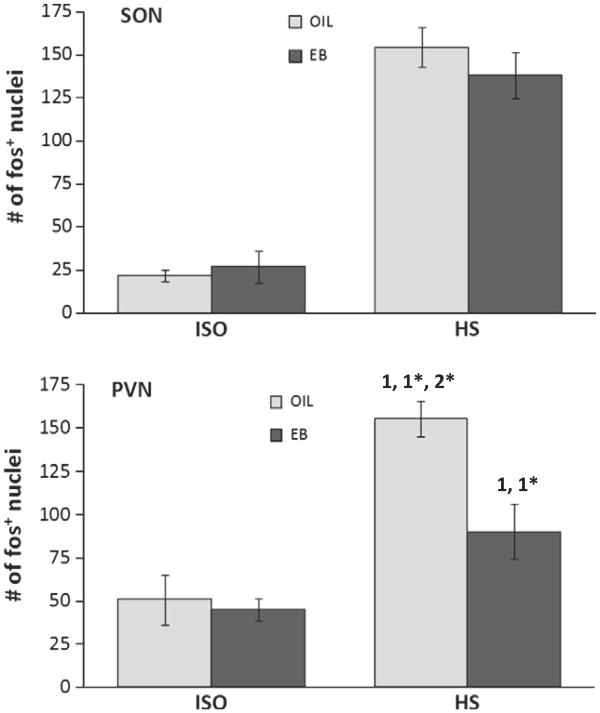

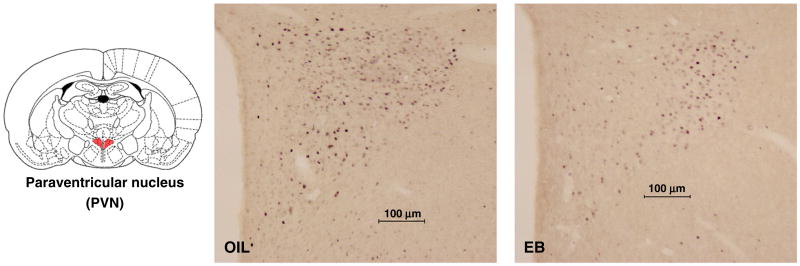

The number of fos-IR neurons in the PVN depended on hormone treatment [F(1,19)=7.80, p<0.05], infusion [F(1,19)=37.79, p<0.001], and the interaction between hormone and infusion [F(1,19)=5.41, p<0.05]. Pairwise comparisons of the interaction revealed that, compared to ISO infusion, the number of fos-IR neurons was significantly greater after HS infusion in both OIL- and EB-treated rats (p<0.001, p<0.05, respectively; Figs. 5, 6) However, after HS infusion, the number of fos-IR neurons in OIL-treated rats was significantly greater than that in EB-treated rats (p<0.01).

Fig. 5.

Number of fos+ neurons in the hypothalamic supraoptic nucleus (SON; top) and paraventricular nucleus (PVN; bottom) of OIL- (gray bars) and EB- (black bars) treated rats after iv infusion of ISO (left bars) or HS (right bars). The number of fos+ neurons in the SON depended upon infusion (F(1,19)=114.15, p<0.001), but was not affected by hormone condition. In contrast, the number of fos+ neurons in the PVN depended upon the interaction between hormone condition and infusion (F(1,19)=5.41, p<0.05), with the HS-induced increase blunted in EB-treated rats. 1=significantly greater than OIL-ISO (OIL-HS p<0.001; EB-HS p<0.05); 1*=significantly greater than EB-ISO (OIL-HS p<0.001; EB-HS p<0.05); 2*=significantly greater than EB-HS (p<0.01).

Fig. 6.

Line drawing (right; adapted from [40]) illustrating the location of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN; red highlighting). Digital photomicrographs from OIL- (middle) and EB-(right) treated rats after iv HS infusion showing fos+ neurons in the PVN. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. Photomicrographs were adjusted for brightness and contrast.

In the SON, the number of fos-IR neurons was significantly greater after HS infusion [F(1,19)=114.15, p<0.001], but there was no difference between hormone treatments, and no interaction between hormone and infusion (Fig. 5).

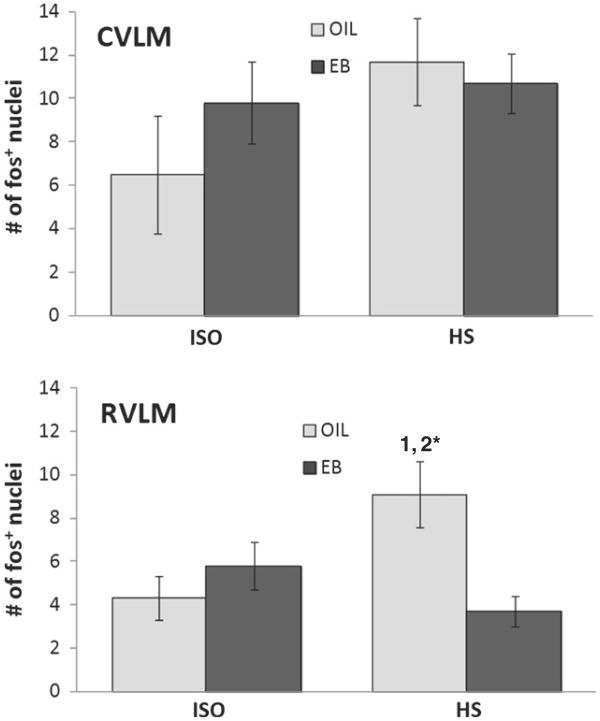

In the CVLM, the number of fos-IR neurons was not affected by hormone treatment or infusion, or by the interaction between hormone and infusion (Fig. 7). In contrast, the number of fos-IR neurons in the RVLM (Fig. 7) depended on the interaction between hormone treatment and infusion [F(1,20)=8.94, p<0.05]. Pairwise comparisons of the interaction revealed that, compared to ISO infusion, the number of fos-IR neurons was significantly greater after HS infusion in OIL-treated rats (p<0.01), but not in EB-treated rats. Moreover, after HS infusion, the number of fos-IR neurons in the RVLM of OIL-treated rats was significantly greater than that of EB-treated rats (p<0.01).

Fig. 7.

Number of fos+ neurons in the caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM; top) and rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM; bottom) of OIL- (gray bars) and EB- (black bars) treated rats after iv infusion of ISO (left bars) or HS (right bars). The number of fos+ neurons in the CVLM was not affected by hormone condition or infusion. In contrast, the number of fos+ neuronsin the RVLM depended upon the interaction between hormone condition and infusion (F(1,19)=8.94, p<0.01), with an HS-induced increase in OIL-treated rats, but not in EB-treated rats. 1=significantly greater than OIL-ISO (p<0.01); 2*=significantly greater than EB-HS (p<0.01).

In the subset of tissue processed for fos and DBH, the absolute numbers of fos-IR neurons in the RVLM (Table 2, Fig. 8) tended to be greater. Nonetheless, similar to tissue labeled only for fos, the number of fos-IR neurons in this subset depended on the interaction between hormone treatment and infusion [F(1,16)=7.94, p<0.05]. Pairwise comparisons of the interaction also revealed that, compared to ISO infusion, the number of fos-IR neurons was significantly greater after HS infusion in OIL-treated (p<0.01), but not in EB-treated rats. Moreover, the number of fos-IR neurons in the RVLM of OIL-treated rats after HS infusion was significantly greater than that of EB-treated rats (p<0.01).

Table 2.

Number of neurons in the RVLM labeled for fos and double-labeled for fos and dopamine-β-hydroxylase (DBH) after iv infusion of 0.15 M NaCl (ISO) or 2 M NaCl (HS) in a subset of OIL- and EB-treated rats. Percentages of fos+ neurons that were double-labeled (% double-labeled) for each condition were calculated as (number of fos+DBH labeled neurons)/(number of fos labeled neurons). The interaction between hormone condition and infusion affected both the number of fos+ neurons (F(1,16)= 7.94, p<0.05) and the number of double-labeled neurons (F(1,16)=5.06, p<0.05).

| fos | fos+DBH | % double-labeled | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OIL-ISO | 7.3 ± 2.2 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 40.8 ± 8.6 |

| OIL-HS | 14.9 ± 1.8*,*** | 7 7± 1 3*,**,*** | 51.8 ± 5.8 |

| EB-ISO | 10.1 ± 1.7 | 4.2 ± 1.0 | 40.1 ± 7.3 |

| EB-HS | 8.1 ± 1.3 | 3.6 ± 1.1 | 42.2 ± 7.3 |

Significantly greater than OIL-ISO (fos p<0.01; fos+DBH p<0.05).

Significantly greater than EB-ISO (p<0.05).

Significantly greater than EB-HS (fos p<0.01; fos+DBH p<0.05).

Double-immunolabeling for fos and DBH (Table 2, Fig. 8) followed the same pattern, with the number of double-labeled neurons depending on the interaction between hormone treatment and infusion [F(1,16) =5.06, p<0.05]. Pairwise comparisons of the interaction revealed that, similar to the pattern for fos labeling alone, double-labeling after HS infusion was significantly greater than that after ISO infusion in OIL-treated rats (p<0.01) but not in EB-treated rats. In addition, double-labeling in the RVLM of OIL-treated rats after HS infusion was significantly greater than that of EB-treated rats (p<0.01). The effect of HS infusion to increase the number of fos-IR neurons in the RVLM—and therefore, the effect of EB treatment to reduce the number of fos-IR neurons in that nucleus— appeared to involve both DBH-positive neurons and neurons that were not labeled for DBH; thus, the percentage of activated (i.e., fos-IR) neurons that also contained DBH was comparable in OIL-and EB-treated rats, regardless of infusion (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Accumulating evidence suggests that estrogens influence hormonal and behavioral responses to hyperosmolality via actions within the CNS [25,39,47–49,52]. In this study, we sought to determine whether estradiol alters neural activation in CNS areas involved in detecting increased pOsm. We also examined other CNS areas involved in body fluid balance to determine whether additional—or alternative—effects of estradiol on neural activation in downstream parts of these CNS pathways could underlie the observed behavioral responses to increased pOsm [30]. This study was guided by our recent findings that estradiol treatment decreased the latency to begin drinking in response to iv HS infusion [30]. We, therefore, used the same protocols as in that study (NaCl concentration, route of administration, rate and duration of infusion) in this initial attempt to determine whether alterations in the detection of increased pOsm by the CNS could underlie the observed differences in the latency to begin drinking.

4.1. Body weight and blood measures

As expected, OIL-treated rats gained weight whereas EB-treated rats lost weight during the 4-day hormone treatment protocol. These observations agree with numerous reports [13,18,20,34,35] and suggest that EB treatment was effective. Plasma Na+ concentrations in blood samples taken from OIL- and EB-treated rats immediately prior to perfusion were comparably increased after iv HS infusion (Table 1). In contrast, neither plasma protein concentration nor hematocrit was affected by the infusion or by hormone treatment (Table 1). Note that pentobarbital was administered through the venous catheters to rapidly anesthetize rats for perfusion. Since all rats were given the same volume of anesthetic (0.2 mL), we did not correct for the additional volume or for the NaCl that otherwise would have remained in the catheter. Consequently, hematocrits and plasma protein concentrations likely were somewhat underestimated in all rats, whereas plasma Na+ concentrations likely were somewhat overestimated in rats that received HS infusion (by ∼0.2 mMol). These caveats notwithstanding, plasma volume (as evidenced by hematocrit and plasma protein concentration) was not affected by iv infusion or by hormone treatment. Thus, increased fos immunolabeling after HS infusion was attributable to hyperosmolality and not to changes in plasma volume. More importantly, hormone treatment did not alter the induced hyperosmolality, as evidenced by plasma Na+ concentration. Thus, any differences in fos immunolabeling between OIL- and EB-treated rats after HS infusion were not attributable to differential hyperosmolality/hypernatremia, but to estradiol-mediated differences in CNS responses to hyperosmolality. These results mirror those in our previous study [30] which showed that differences in the latency to begin drinking in response to HS infusion were not attributable to differences in induced hyperosmolality, and support the idea that estradiol alters the detection of increased pOsm by the CNS.

4.2. Immunolabeling

Hyperosmolality is an effective stimulus for neuronal activation in CVOs including SFO, OVLT, and AP, and in the NTS [4,7,17,29,42]. Surprisingly, then, we did not see increased fos-IR neurons in SFO or OVLT in response to HS infusion in either OIL- or EB-treated rats, nor was there an increase in fos-IR neurons in the NTS. The discrepancy between the current results and previous reports may be attributable to differences in the magnitude of the induced hyperosmolality and/or the rate at which osmolality increases, or to the fact that our small iv infusion largely ‘bypassed’ gut osmoreceptors that signal the NTS. In other words, slow iv administration of a comparatively small volume of concentrated saline may be insufficient to produce neural activation in SFO, OVLT, or NTS, whereas rapid iv, subcutaneous or intragastric administration of a larger volume of a concentrated saline solution is sufficient. Alternatively, since many of the previous studies examined fos immunolabeling in male rats, the possibility of sex differences in central responses to increased osmolality must be considered. Nonetheless, estradiol did not alter the responsiveness of the SFO, OVLT, or NTS to iv infusion of HS.

In contrast, estradiol did alter neural activation in response to iv HS in the AP, the hindbrain CVO. The more rapid onset of HS-stimulated drinking by EB-treated rats [30] led us to hypothesize that estradiol enhances detection of increased pOsm by specific CNS area(s), which we expected would be indicated by greater activation in those areas. This expectation was not met. Rather, estradiol reduced HS-induced activation in the AP. Although this finding could indicate that a lesser degree of activation in AP is necessary for HS-induced water intake by EB-treated rats, it also is possible that activation in the AP stimulated by increased pOsm includes neurons downstream from osmo-/Na+-receptors which exert an inhibitory influence on HS-induced water intake. Therefore, the shorter latency to begin drinking after HS infusion seen in EB-treated rats [30] may be attributable to the activation of fewer inhibitory neurons in the AP. This explanation suggests that, in response to HS infusion, different populations of neurons in the AP with differential sensitivity to estradiol are activated at different times or in response to different degrees of hyperosmolality. Additional studies will be necessary to discriminate among these possibilities but, in any case, the present results show that the presence of estradiol influences the responsiveness of osmosensitive neurons in the AP.

AP is important in detecting changes in pOsm [38] and sends neural projections to numerous CNS areas that are involved in body fluid regulation [9,11,46]. Therefore, given the attenuation of neural activation in the AP of EB-treated rats, it seems reasonable to assume that activation in areas that are innervated by AP also would be affected. Consistent with this idea, although neural activation in the PVN, which receives direct and indirect projections from AP [9,45,46,55,56], was increased after HS infusion in both OIL- and EB-treated rats, the increase was blunted in EB-treated rats (Figs.5, 6; see also [63]). Similarly, neural activation in the RVLM, which also receives projections from AP [9], was increased in response to HS infusion in OIL-treated rats, but not in EB-treated rats (Figs. 7, 8, Table 2). These results support the idea that projections from AP are important in central activation produced by HS infusion, which may have functional significance for compensatory responses to hyperosmolality. More specifically, estradiol reduced HS-induced neuronal activation in the hypothalamic PVN, which is involved in body fluid homeostasis via VP and OT secretion and projections to autonomic areas in the hindbrain [64]. At the same time, estradiol reduced HS-induced activation of the sympathoexcitatory area in the RVLM (see also [60]). The reduction in the RVLM involved both DBH-positive neurons and non-DBH positive neurons, suggesting that estradiol had a general effect to reduce HS-induced neural activation in the RVLM, rather than a selective effect on a specific phenotype of neurons therein.

The preceding discussion of the current findings assumes that two separate and parallel pathways originate from AP—one to the PVN, one to the RVLM—an assumption that is supported by numerous anatomical studies [6,9,11,46]. Further support for this idea is found in reports that AP stimulation alters sympathetic nerve activity [23,26], and that lesions of the AP alter activation in the PVN stimulated by hypernatremia [7,32]. However, the idea of parallel pathways does not take into account that CNS areas involved in body fluid balance are interconnected. For example, ‘preautonomic’ neurons in the parvocellular portion of the PVN influence autonomic function via projections to the hindbrain/RVLM [64]. Thus, the present findings may instead be explained by a neural circuit in which input from the AP contributes to activation of the PVN which, in turn, influences activity in the RVLM. Our initial examination of PVN labeling indicates that the reduction of fos-IR neurons in EB-treated rats occurred most prominently in the pre-autonomic portion, an observation that is consistent with the possibility that attenuated neural activation in the AP underlies the reduced activation in the PVN and, thereby, the reduced activity in the sympathoexcitatory RVLM. However, reciprocal connections between AP and PVN, between PVN and RVLM, and between AP and RVLM also exist [6,9,11,45,46,55,56,64], suggesting that a simple circuit is unlikely. Rather, there may be multiple points of modulation within reciprocally connected CNS areas responsible for centrally-mediated responses to hyperosmolality. Clearly, additional studies of functional activation (e.g., tract-tracing studies, electrophysiological recording) will be necessary to tease apart the role of estradiol in modifying hyperosmolality-induced activity within these areas.

Regardless of the specifics of the relationships within these central areas, the present findings converge upon interconnected CNS areas associated with blood pressure control. With our goal of understanding how estradiol reduces the latency to start drinking in response to HS infusion, this convergence raises an interesting possibility related to reports that hyperosmolality elevates blood pressure [3,22,53], and that elevated blood pressure inhibits water intake stimulated by hyperosmolality and delays the onset of drinking [54]. Increased neural activation in the preautonomic PVN and in the sympathoexcitatory RVLM in response to HS infusion as we observed are consistent with elevations in blood pressure ([59]; see also [36]). By extension, then, attenuation of neural activation in these areas by estradiol suggests that the elevated blood pressure in response to HS may be blunted or absent in EB-treated rats (see also [24,44,63]). Thus, we propose that the blunting/absence of the initial blood pressure elevation allows EB-treated rats to drink in response to a smaller degree of hyperosmolality. In contrast, OIL-treated rats (with the elevated blood pressure suggested by increased neural activation in PVN and RVLM), delay drinking in response to HS infusion until pOsm increases to levels that overwhelm the inhibition associated with elevated blood pressure. This is a readily testable hypothesis, which we have begun to assess.

In the face of attenuated neural activation in the AP, it would be easy to presume that activity would be affected in all downstream central areas. However, the current results suggest some specificity to the estradiol effects on CNS responses to HS infusion. Perhaps not surprisingly, given that elevated blood pressure accompanies hyperosmolality [3,22,53], there was no neural activation in the sympathoinhibitory CVLM of either OIL- or EB-treated rats in response to HS infusion. Thus, the shorter latency to begin drinking in EB-treated rats does not appear to involve sympathoinhibition.

In contrast, HS infusion produced comparable neural activation in the SON of both groups. This observation was somewhat surprising, as Hartley and colleagues [21] showed greater HS-induced fos immunolabeling in the SON of EB-treated rats, along with enhanced VP release in response to hyperosmolality ([21]; see also [2,15]). However, the infusion protocol used by Hartley delivered more than twice the amount of NaCl (∼2.5 vs. ∼1.0 mMol) in less than half the time (∼7 vs. 15 min) in order to produce substantial and long-lasting hyperosmolality. Our goal was to produce a milder hyperosmolality and our focus was on estradiol effects in the initial 15 min after HS infusion. Thus, differences in the magnitude of the hyperosmolality and/or in the rate at which pOsm increases may be important in determining the outcome, as also seems to be the case for behavioral responses to hyperosmolality ([14]; also [30,58] vs. [33,34]). Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that the more modest increase in pOsm elicited robust activation in the SON, despite reduced neural activation in the AP. These observations suggest the possibility that VP neurons in the SON of EB-treated rats may be more responsive to a lesser degree of input related to increased pOsm. Alternatively, the neurons themselves may be intrinisically osmosensitive [41]. Additional studies and measurements of circulating VP will be necessary to assess these ideas. At present, however, it appears that estradiol effects on HS-induced CNS activation are site specific and preferentially involve areas associated with the sympathoexcitatory responses to hyperosmolality.

4.3. Summary and conclusions

These experiments were based on our previous study showing that estradiol facilitates behavioral responsiveness to increased osmolality [30], and were designed to test the hypothesis that estradiol enhances detection of hyperosmolality by the CNS using immunocytochemistry to examine neural activation in multiple CNS areas in the same animals. Previous reports of osmotically-stimulated neural activation [4,7,17,29,42] provide a solid foundation upon which to base the present results; however, the results of studies using fos immunolabeling must be interpreted cautiously due to the limitations of the technique (see [11] for discussion): 1–2 h typically is necessary to attain protein levels that are detectable using standard immunocytochemical methods; not all neurons express fos upon activation; and increased fos labeling is indicative of activation, but inhibition cannot be inferred from low levels of labeling. In addition, the central areas that typically are the focus of investigations of neural activation stimulated by hyperosmolality also are activated by alterations in blood pressure, as well as by challenges to body fluid volume (e.g., [10,11,33,34]). The pattern of fos immunolabeling we observed is generally consistent with other studies of osmotically-stimulated activation [4,7,17,29,42] and differs from that reported in studies of activation stimulated by hypertension, particularly in regard to neural activation in the RVLM (e.g., [12,19]). Nonetheless, additional studies will be necessary to conclusively determine whether blood pressure effects related to hyperosmolality contribute to the present findings. Those provisos notwithstanding, the present study yielded several surprising findings.

First, a modest increase in pOsm did not activate osmo- or Na+-receptors in forebrain CVOs (SFO, OVLT) or in afferent terminal sites related to visceral osmoreceptor input (NTS). Rather, slow infusion of HS appeared to be detected primarily by the hindbrain CVO, the AP. These results suggest that the sensitivity of different populations of osmo-/Na+-receptor differs depending on the degree of hyperosmolality, the rate of change, or the route of administration. Despite the lack of effect in the SFO, OVLT, and NTS, however, the magnitude of the induced hyperosmolality was sufficient to activate other CNS areas, including the SON, PVN, and RVLM. Thus, it seems that slow, iv HS infusion selectively excited the AP which, in turn, activated other CNS areas associated with body fluid balance.

Second, estradiol did not enhance the responsiveness of osmoreceptors in SFO, OVLT, or NTS. Rather, estradiol effects were selective to three interconnected areas—the AP, PVN, and RVLM—and served to decrease neural activation induced by iv HS in those areas. Taken together, these differences may be instructive in terms of the sensitivity of different osmoreceptor populations, and in terms of estradiol effects on the sensitivity of osmoreceptors. That is, estradiol may differentially affect responses in specific populations of osmoreceptors and, thereby, have selective effects on other central areas associated with responses to increased osmolality. Given the involvement of the RVLM and the PVN in sympathetic nerve activity [60,64], a possible scenario linking the behavioral and central responses to hyperosmolality is that estradiol blunts the HS-induced blood pressure changes [3,22,53] which provide an initial inhibitory influence on water intake [54]. Absent that initial inhibition, therefore, EB-treated rats begin to drink more rapidly in response to increased osmolality.

Acknowledgments

Grants from the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders DC-06360 (KSC) and the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology Health Research Program HR 09-123 (KSC) supported this research.

Portions of these data were presented in preliminary form at the annual meetings of the Society for the Study of Ingestive Behaviors (Portland, OR; July, 2009) and the Society for Neuroscience (Chicago, IL; October, 2009).

References

- 1.Andersen LJ, Jensen TU, Bestle MH, Bie P. Gastrointestinal osmoreceptors and renal sodium excretion in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R287–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.2.R287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barron WM, Schreiber J, Lindheimer MD. Effect of ovarian sex steroids on osmoregulation and vasopressin secretion in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:E352–61. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1986.250.4.E352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bealer SL. Central control of cardiac baroreflex responses during peripheral hyperosmolality. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R1157–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.5.R1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisley JW, Rees SM, McKinley MJ, Hards DK, Oldfield BJ. Identification of osmoresponsive neurons in the forebrain of the rat: a Fos study at the ultrastructural level. Brain Res. 1996;720:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bossmar T, Forsling M, Akerlund M. Circulating oxytocin and vasopressin is influenced by ovarian steroid replacement in women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1995;74:544–8. doi: 10.3109/00016349509024387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Card JP, Sved JC, Craig B, Raizada M, Vazquez J, Sved AF. Efferent projections of rat rostroventrolateral medulla C1 catecholamine neurons: implications for the central control of cardiovascular regulation. J Comp Neurol. 2006;499:840–59. doi: 10.1002/cne.21140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson SH, Collister JP, Osborn JW. The area postrema modulates hypothalamic fos responses to intragastric hypertonic saline in conscious rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R1921–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.6.R1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciura S, Liedtke W, Bourque CW. Hypertonicity sensing in organum vasculosum lamina terminalis neurons: a mechanical process involving TRPV1 but not TRPV4. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14, 669–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1420-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham ET, Jr, Miselis RR, Sawchenko PE. The relationship of efferent projections from the area postrema to vagal motor and brain stem catecholamine-containing cell groups: an axonal transport and immunohistochemical study in the rat. Neuroscience. 1994;58:635–48. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis KS, Krause EG, Contreras RJ. Fos expression in non-catecholaminergic neurons in medullary and pontine nuclei after volume depletion induced by polyethylene glycol. Brain Res. 2002;948:149–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dampney RA, Horiuchi J. Functional organisation of central cardiovascular pathways: studies using c-fos gene expression. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;71:359–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dampney RA, Polson JW, Potts PD, Hirooka Y, Horiuchi J. Functional organization of brain pathways subserving the baroreceptor reflex: studies in conscious animals using immediate early gene expression. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003;23:597–616. doi: 10.1023/A:1025080314925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan L, Smith CE, Curtis KS. Regional differences in estradiol effects on numbers of HSD2-containing neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract of rats. Brain Res. 2010;1358:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzsimons JT. The effects of slow infusions of hypertonic solutions on drinking and drinking thresholds in rats. J Physiol. 1963;167:344–54. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1963.sp007154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsling ML, Peysner K. Pituitary and plasma vasopressin concentrations and fluid balance throughout the oestrous cycle of the rat. J Endocrinol. 1988;117:397–402. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1170397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forsling ML, Stromberg P, Akerlund M. Effect of ovarian steroids on vasopressin secretion. J Endocrinol. 1982;95:147–51. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0950147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freece JA, Van Bebber JE, Zierath DK, Fitts DA. Subfornical organ disconnection alters Fos expression in the lamina terminalis, supraoptic nucleus, and area postrema after intragastric hypertonic NaCl. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R947–55. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00570.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geary N, Asarian L. Cyclic estradiol treatment normalizes body weight and test meal size in ovariectomized rats. Physiol Behav. 1999;67:141–7. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham JC, Hoffman GE, Sved AF. c-Fos expression in brain in response to hypotension and hypertension in conscious rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;55:92–104. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00032-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graves NS, Hayes H, Fan L, Curtis KS. Time course of behavioral, physiological, and morphological changes after estradiol treatment of ovariectomized rats. Physiol Behav. 2011;103:261–7. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartley DE, Dickson SL, Forsling ML. Plasma vasopressin concentrations and Fos protein expression in the supraoptic nucleus following osmotic stimulation or hypovolaemia in the ovariectomized rat: effect of oestradiol replacement. J Neuroendocrinol. 2004;16:191–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-8194.2004.01150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasser EM, Haywood JR, Bishop VS. Role of vasopressin and sympathetic nervous system during hypertonic NaCl infusion in conscious dog. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:H652–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.248.5.H652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasser EM, Nelson DO, Haywood JR, Bishop VS. Inhibition of renal sympathetic nervous activity by area postrema stimulation in rabbits. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:H91–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.1.H91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haywood JR, Hinojosa-Laborde C. Sexual dimorphism of sodium-sensitive renal-wrap hypertension. Hypertension. 1997;30:667–71. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.3.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haywood SA, Simonian SX, van der Beek EM, Bicknell RJ, Herbison AE. Fluctuating estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in brainstem norepinephrine neurons through the rat estrous cycle. Endocrinology. 1999;140:3255–63. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.7.6869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hegarty AA, Hayward LF, Felder RB. Sympathetic responses to stimulation of area postrema in decerebrate and anesthetized rats. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H1086–95. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.3.H1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernandez I, Delgado JL, Diaz J, Quesada T, Teruel MJ, Llanos MC, et al. 17beta-estradiol prevents oxidative stress and decreases blood pressure in ovariectomized rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R1599–605. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.5.R1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirshoren N, Tzoran I, Makrienko I, Edoute Y, Plawner MM, Itskovitz-Eldor J, et al. Menstrual cycle effects on the neurohumoral and autonomic nervous systems regulating the cardiovascular system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1569–75. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hochstenbach SL, Ciriello J. Plasma hypernatremia induces c-fos activity in medullary catecholaminergic neurons. Brain Res. 1995;674:46–54. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01434-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones AB, Curtis KS. Differential effects of estradiol on drinking by ovariectomized rats in response to hypertonic NaCl or isoproterenol: implications for hyper- vs. hypo-osmotic stimuli for water intake. Physiol Behav. 2009;98:421–6. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kahrilas PJ, Rogers RC. Rat brainstem neurons responsive to changes in portal blood sodium concentration. Am J Physiol. 1984;247:R792–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.247.5.R792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato K, Chu CP, Kannan H, Ishida Y, Nishimori T, Nose H. Regional differences in the expression of Fos-like immunoreactivity after central salt loading in conscious rats: modulation by endogenous vasopressin and role of the area postrema. Brain Res. 2004;1022:182–94. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.02.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kisley LR, Sakai RR, Ma LY, Fluharty SJ. Ovarian steroid regulation of angiotensin II-induced water intake in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R90–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.1.R90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krause EG, Curtis KS, Davis LM, Stowe JR, Contreras RJ. Estrogen influences stimulated water intake by ovariectomized female rats. Physiol Behav. 2003;79:267–74. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krause EG, Curtis KS, Stincic TL, Markle JP, Contreras RJ. Oestrogen and weight loss decrease isoproterenol-induced Fos immunoreactivity and angiotensin type 1 mRNA in the subfornical organ of female rats. J Physiol. 2006;573:251–62. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Q, Sullivan MJ, Dale WE, Hasser EM, Blaine EH, Cunningham JT. Fos-like immunoreactivity in the medulla after acute and chronic angiotensin II infusion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:1165–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohamed MK, El-Mas MM, Abdel-Rahman AA. Estrogen enhancement of baroreflex sensitivity is centrally mediated. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R1030–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.4.R1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osborn JW, Collister JP, Carlson SH. Angiotensin and osmoreceptor inputs to the area postrema: role in long-term control of fluid homeostasis and arterial pressure. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2000;27:443–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pamidimukkala J, Hay M. 17beta-estradiol inhibits angiotensin II activation of area postrema neurons. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1515–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00174.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prager-Khoutorsky M, Bourque CW. Osmosensation in vasopressin neurons: changing actin density to optimize function. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rinaman L, Stricker EM, Hoffman GE, Verbalis JG. Central c-Fos expression in neonatal and adult rats after subcutaneous injection of hypertonic saline. Neuroscience. 1997;79:1165–75. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers RC, Novin D, Butcher LL. Electrophysiological and neuroanatomical studies of hepatic portal osmo- and sodium-receptive afferent projections within the brain. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1979;1:183–202. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(79)90016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rowland NE, Fregly MJ. Role of gonadal hormones in hypertension in the Dahl salt-sensitive rat. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1992;14:367–75. doi: 10.3109/10641969209036195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. Immunohistochemical identification of neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus that project to the medulla or to the spinal cord in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1982;205:260–72. doi: 10.1002/cne.902050306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. The organization of noradrenergic pathways from the brainstem to the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei in the rat. Brain Res. 1982;257:275–325. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(82)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simerly RE, Chang C, Muramatsu M, Swanson LW. Distribution of androgen and estrogen receptor mRNA-containing cells in the rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol. 1990;294:76–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.902940107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simonian SX, Herbison AE. Differential expression of estrogen receptor and neuropeptide Y by brainstem A1 and A2 noradrenaline neurons. Neuroscience. 1997;76:517–29. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00406-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Somponpun SJ, Johnson AK, Beltz T, Sladek CD. Estrogen receptor-alpha expression in osmosensitive elements of the lamina terminalis: regulation by hypertonicity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R661–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00136.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stachenfeld NS. Sex hormone effects on body fluid regulation. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2008;36:152–9. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e31817be928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stachenfeld NS, Taylor HS. Effects of estrogen and progesterone administration on extracellular fluid. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1011–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01032.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stern JE, Zhang W. Preautonomic neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus contain estrogen receptor beta. Brain Res. 2003;975:99–109. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stocker SD, Madden CJ, Sved AF. Excess dietary salt intake alters the excitability of central sympathetic networks. Physiol Behav. 2010;100:519–24. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stocker SD, Stricker EM, Sved AF. Acute hypertension inhibits thirst stimulated by ANG II, hyperosmolality, or hypovolemia in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;280:R214–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.1.R214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swanson LW, Kuypers HG. The paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus: cytoarchitectonic subdivisions and organization of projections to the pituitary, dorsal vagal complex, and spinal cord as demonstrated by retrograde fluorescence double-labeling methods. J Comp Neurol. 1980;194:555–70. doi: 10.1002/cne.901940306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Swanson LW, Sawchenko PE, Berod A, Hartman BK, Helle KB, Vanorden DE. An immunohistochemical study of the organization of catecholaminergic cells and terminal fields in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus. J Comp Neurol. 1981;196:271–85. doi: 10.1002/cne.901960207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takezawa H, Hayashi H, Sano H, Saito H, Ebihara S. Circadian and estrous cycle-dependent variations in blood pressure and heart rate in female rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:R1250–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.5.R1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thrasher TN, Fregly MJ. Responsiveness to various dipsogenic stimuli in rats treated chronically with norethynodrel, ethinyl estradiol and both combined. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977;201:84–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toney GM, Stocker SD. Hyperosmotic activation of CNS sympathetic drive: implications for cardiovascular disease. J Physiol. 2010;588:3375–84. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang G, Drake CT, Rozenblit M, Zhou P, Alves SE, Herrick SP, et al. Evidence that estrogen directly and indirectly modulates C1 adrenergic bulbospinal neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Brain Res. 2006;1094:163–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watson RE, Jr, Wiegand SJ, Clough RW, Hoffman GE. Use of cryoprotectant to maintain long-term peptide immunoreactivity and tissue morphology. Peptides. 1986;7:155–9. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(86)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woolley CS, McEwen BS. Roles of estradiol and progesterone in regulation of hippocampal dendritic spine density during the estrous cycle in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336:293–306. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xue B, Badaue-Passos D, Jr, Guo F, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Hay M, Johnson AK. Sex differences and central protective effect of 17beta-estradiol in the development of aldosterone/NaCl-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1577–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01255.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang Z, Han D, Coote JH. Cardiac sympatho-excitatory action of PVN-spinal oxytocin neurones. Auton Neurosci. 2009;147:80–5. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]