Abstract

Purpose

Health systems around the world are struggling to meet the needs of aging populations and increasing numbers of clients with complex health conditions. Faced with multiple health system challenges, governments are advocating for team-based approaches to health care. Key descriptors used to describe health care teams include “interprofessional,” “multiprofessional,” “interdisciplinary,” and “multidisciplinary.” Until now there has been no review of the use of terminology relating to health care teams. The purpose of this integrative review is to provide a descriptive analysis of terminology used to describe health care teams.

Methods

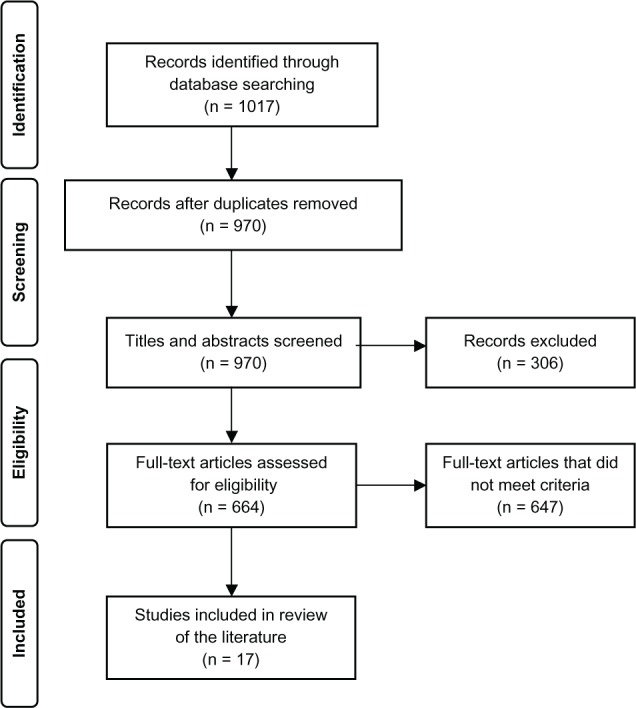

An integrative review of the literature was conducted because it allows for the inclusion of literature related to studies using diverse methodologies. The authors searched the literature using the terms interprofessional, multiprofessional, interdisciplinary, and multidisciplinary combined with “health teams” and “health care teams.” Refining strategies included a requirement that journal articles define the term used to describe health care teams and include a list of health care team members. The literature selection process resulted in the inclusion of 17 journal articles in this review.

Results:

Multidisciplinary is more frequently used than other terminology to describe health care teams. The findings in this review relate to frequency of terminology usage, justifications for use of specific terminology, commonalities and patterns related to country of origin of research studies and health care areas, ways in which terminology is used, structure of team membership, and perspectives of definitions used.

Conclusion:

Stakeholders across the health care continuum share responsibility for developing and consistently using terminology that is both common and meaningful. Notwithstanding some congruence in terminology usage, this review highlights inconsistencies in the literature and suggests that broad debate among policy makers, clinicians, educators, researchers, and consumers is still required to reach useful consensus.

Keywords: descriptors, interprofessional, multiprofessional, interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary

Introduction

Health systems, particularly those in industrialized countries, are struggling to meet both the needs of aging populations and growing numbers of clients with multiple and complex health issues.1 Additionally, health systems face cost constraints, workforce shortage pressures, and increasing complexity of required health care knowledge.2–4 Historically, interactions between health professionals have been authoritarian and dominated by doctors.5 Faced with multiple health system challenges, governments are advocating for more team-based approaches to health care,3,6,7 to increase the number and balance of complementary contributions to client-focused care.8

A recent report on team-based health care emphasizes the potential of teams to improve the value of health care.9 Health professionals working in teams to deliver health care is neither a new concept nor a new practice. The concept of team care was mooted and documented as early as 1920, in a report to the UK Minister of Health10 recommending that “General Practitioners; Visiting Consultants and Specialists; Officers engaged in Communal Services; Visiting Dental Surgeons; [and] Workers in ancillary services” work together in primary health centers. The practical implementation of health care teams can be traced to the development of Engel’s 1977 biopsychosocial model of health.11–13 The model incorporates social, psychological, and behavioral dimensions of illness13 and seeks to address inadequacies in the traditional biomedical model of care in which disease, and not the client, predominates.14 Engel13 asserted that a more holistic model of care could be achieved with a shift in focus from doctor-centric service delivery to health care services delivered by teams of professionals.

“Health care teams” as an area of research is well documented. A search of the CINAHL® database for English-language text using the terms health care team “OR” health team in the “TX All Text” field returned 2917 articles published since 2000. Descriptors such as “interprofessional,” “multiprofessional,” “interdisciplinary,” and “multidisciplinary” are terms used to describe both members of different professions working together as health care teams and ways in which health care teams collaborate. Inconsistencies in terms used to describe health care teams in either context, including the interchangeable use of terms, are apparent in the literature and are highlighted by numerous researchers.8,15–19 A search of the literature did not find any reviews that have specifically considered patterns of terminology usage.

While standardized definitions of terms used to describe different health care teams may not be feasible, given the complexity of health care contexts, gaining an understanding of current patterns of usage will contribute to greater consistency in the use of terminology. Gaining an understanding of how and in which context health care team descriptors are being used provides a departure point from which stakeholders can reflect on terminology usage prior to developing interprofessional education programs, conducting research, writing policy, or developing teams. Consistency in the use of terms to describe different health care teams in policy, education, training, clinical practice, and research could improve communication between sectors, enable individual groups to focus on improving the contribution that each make to the client health care journey, and provide greater clarity for consumers.

Until now there has been no review of the use of terminology relating to health care teams. A clearly identified gap in the literature makes the findings of this integrative review significant in developing this substantive area of inquiry. The purpose of this integrative review is to provide a descriptive analysis of terminology used to describe health care teams.

Methods

A search of the CINAHL and Web of Science® (Thomson Reuters Web of Knowledge) databases was conducted using the following criteria: English-language text published between 2000 and 2011. The search terms in the “TX All Text” field in CINAHL and in the “TS (topic)” field in Web of Science were interprofessional “OR” multiprofessional “OR” interdisciplinary “OR” multidisciplinary combined with “AND” health team “OR” health care team. Dissertations and theses were excluded from the search strategy.

Abstracts of all journal articles returned in the search were screened and the articles were retained if the abstract included one or more of the terms interprofessional, multiprofessional, interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary and the term “health team” or “health care team.” The full text of retained articles was then screened and the articles were retained if they included a definition of interprofessional, multiprofessional, interdisciplinary, or multidisciplinary; if they identified health care team members; and if they related to health care teams in health practice settings. This resulted in 17 journal articles being included in this integrative review (Table 1).

Table 1.

Articles meeting selection criteria for inclusion

| Reference | Terminology used | Definition | Country | Setting | Health area | Team members |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atwal and Caldwell24 | Multidisciplinary | Team members “having different professional backgrounds but who make complementary contributions to patient care” | UK | Acute care – hospital wards | Elder care Orthopedics Acute medicine | Doctor, nurse, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, and social worker |

| Black11 | Interdisciplinary | Team members “[interact] to produce a final outcome on behalf of patients” | USA | Hospital – private, not-for-profit | Elder care | Medicine, nursing, and social work |

| Chan et al27 | Multidisciplinary | “Team care coordinated by a leader who takes responsibility for overall patient care. Members contribute views and recommendations according to their particular expertise, which may be integrated by the leader” | Australia | General practice and community health care | Chronic disease | General practitioners and allied health providers including podiatrists, optometrists, diabetes educators, dietitians, cardiac rehabilitation workers, exercise physiologists, and psychologists |

| Cioffi et al28 | Multidisciplinary | Use the definition provided by Schofield and Amodeo19: “a number of individuals from various disciplines [who] are involved in a project but work independently” | Australia | Community health care | Chronic disease | Community nurses, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, and social workers |

| Delva et al31 | Interdisciplinary | “Groups of professionals who work collaboratively to develop processes and plans for patients” | Canada | University primary care teaching practice | Primary care | Teaching teams consisting of physicians, nurses, resident physicians, receptionist, secretaries, nutritionists, social workers, and administrative staff |

| Gibbon et al25 | Interprofessional | “‘Processes’ of intervention” | UK | Hospital – stroke rehabilitation units | Stroke patients | Nurses, doctors, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, social workers, and clinical psychologist |

| Multiprofessional | “The ‘structural’ components of a team” | UK | Hospital – stroke rehabilitation units | Stroke patients | Nurses, doctors, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, social workers, and clinical psychologist | |

| Goldsmith et al29 | Interdisciplinary | “Collaboration among health care providers with specialized knowledge from multiple disciplines” | USA | Veterans Affairs hospital | Geriatric and palliative care | Social worker, chaplain, psychologist, nurse, and doctors |

| Haggerty et al33 | Multidisciplinary | “Practitioners from various health disciplines collaborate in providing ongoing health care” | Canada | Community | Primary health care | Study based on Canadian primary health care experts: family physicians, nurses, academics, and decision makers |

| Kim et al60 | Multidisciplinary | Specific to primary health care the authors define multidisciplinary as “PHC [primary health care] delivered by health professionals from multiple disciplines, including nurses, physicians, dentists, and public health doctors” | Korea | Nursing faculty and primary health care | Primary health care | Nurse, physician, social workers, and dentists |

| Kuder et al30 | Interdisciplinary | “A team integrates its various disciplinary perspectives and maintains a network of cooperation and communication” | USA | Rural geriatric health care | Gerontology | Physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant, pharmacist, and social worker |

| Kvarnström26 | Interprofessional | “‘Inter’ relates to the dimension of collaboration […] ‘profession’ […] differentiates from the term ‘discipline’ in the sense that disciplines may be regarded as academic disciplines as well as sub-specialities within professions” | Sweden | Swedish local health care settings | Primary care, psychiatric care, geriatric care, rehabilitation | Occupational therapist, registered nurse, physiotherapist, medical social worker, administrative assistant, physician, practical nurse, psychologist, and speech therapist |

| Mills et al35 | Interprofessional | “Teams work jointly to provide health care, where each member of the team contributes within the context of his or her profession” | Australia | Remote or isolated | Primary health care | Medical officers, specialist nurses, indigenous health workers, local indigenous health service managers, distant health service managers, and allied health professionals |

| Molleman et al36 | Multidisciplinary | “Care providers with a range of occupational backgrounds collectively discussing a patient leading to collective decision-making and action” | Holland | N/A – survey distributed to medical specialists (nonspecific to setting) | Oncology and geriatrics | Geriatric team: head of geriatric department, clinical geriatrician, geriatrician internist, resident internal medicine specialist, psychiatrist, neurologist, social worker, specialized nurses, and psychologist Oncology team: intern oncologist, hematologist, specialized nurse, internal medicine resident, radiotherapist, social worker, dietitian, physiotherapist, mental care assistant, clinical chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist |

| Molleman et al44 | Multidisciplinary | Use the terminology in the context of medical teamwork: “work arrangement in which physicians from different medical specialities regularly meet to share, weigh and synthesize information concerning individual patients from a specific patient group, and where they, at least to some extent, collectively make decisions about diagnoses and treatment” | Holland | Hospital | Medical specialties | Physicians from different medical specialties |

| Shaw32 | Interprofessional | Use the definition provided by D’Amour and Oandasan33: “The development of cohesive practice between professionals from different disciplines […] it involves continuous interaction and knowledge sharing between professionals […] all while seeking to optimize the patient’s participation” | Canada | Family health center in an urban teaching hospital | Primary care | Nurse, family physician, family medicine residents, dietitian, and pharmacist |

| Solheim et al23 | Multidisciplinary | “Members maintain discipline-specific roles” | USA | Community | Primary health care | Nurse (nurse participants identified physicians and social workers as collaborators in team-based primary health care) |

| Spencer and Cooper45 | Multidisciplinary | “Interdependency with other professionals and being able to combine perceptions and skills to synthesise a more complex and comprehensive plan of care” | UK | Hospital | Type 1 diabetes | General pediatric consultant, specialist nurse, specialist dietitian, and general psychologist |

Notes: Primary care draws from the biomedical model. It is a person’s first point of entry into the health system. Primary health care draws from the social model of health. It considers that people’s basic needs must first be met in order for health gain to occur.59

Abbreviation: N/A, not applicable.

An integrative literature review is the broadest type of research review method. It enables a fuller understanding of phenomena, as it allows for the inclusion of literature related to studies using diverse methodologies.20,21 As the phenomenon of this review is the use of terminology to describe health care teams, included journal articles were not methodologically critiqued or assessed using a hierarchy of evidence-for-practice, although assessment is often performed in literature reviews.

During the literature search for this integrative review, the authors found a substantial number of journal articles relating to health care teams in the context of education. The authors observed that the term interprofessional is consistently used in relation to the joint education of health professionals from various health professions and disciplines. A separate review of the literature would need to be conducted to provide evidence for this observation. The authors acknowledge that the terminology used in health care education may affect the terminology used in practice. However, given the extent of literature relating to health care teams in educational contexts, journal articles relating to health care teams in the context of education were excluded from this literature review.

Included articles were reviewed to ascertain how terminology used to describe health care teams is defined in the literature. Comparative analysis of journal articles resulted in findings that relate to frequency of terminology usage, justifications for use of specific terminology, commonalities and patterns related to country of origin of research studies and health care areas, ways in which terminology is used structure of team membership, and perspectives of definitions used. Table 1 presents data extracted from the included articles. The Discussion section of this article contextualizes findings in this review within the broader literature.

Figure 1 demonstrates the literature selection process. The flowchart is adapted from an original flowchart developed for systematic reviews.22

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature selection process.

Note: Adapted with permission from Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e 1000097.22

Findings

This integrative review of the literature found that the term multidisciplinary is used more frequently than other terms to describe health care teams. Of the 17 journal articles included in this review, nine use multidisciplinary, four use interdisciplinary, and three use interprofessional; the remaining article uses both multiprofessional and interprofessional (Table 1).

While all studies define the term used, only four studies justify their choice of terminology. Solheim et al23 acknowledge distinctions between the terms multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary and base their use of multidisciplinary “on the value of having more than one discipline on a team.” Atwal and Caldwell’s24 use of the term multidisciplinary in their study is justified as follows: “the experience of working together in a multidisciplinary team was one that was common to all nurses within the study area, whereas working interprofessionally was less well understood.”

Gibbon et al25 chose to use the term multiprofessional in reference to the structural components of a team and the term interprofessional in reference to processes of intervention. Kvarnström’s26 study into health professionals’ perceived difficulties in teamwork uses the term interprofessional, stating: “the prefix ‘inter’ relates to the dimension of ‘collaboration’ [… and] the term ‘profession’ thus different[iates] from the term ‘discipline’ in the sense that disciplines may be regarded as academic disciplines or sub-specialties within professions.”

The term multidisciplinary is used in the two Australian studies relating to chronic disease.27,28 Of the four studies conducted in the United States, three relate to geriatric care and all three use the term interdisciplinary.11,29,30 There is no consistency of terminology usage in the three Canadian studies included in this review: Delva et al31 use the term interdisciplinary, Shaw32 uses interprofessional, and Haggerty et al33 use multidisciplinary. Although, the article by Haggerty et al33 does not define the members of a multidisciplinary team per se, the study includes family physicians, nurses, academics, and decision makers, and it asks participants to define an operational definition for “multidisciplinary team.” This question resulted in more than 80% of Haggerty et al’s33 study participants agreeing to the following definition for multidisciplinary teams: “practitioners from various health disciplines [who] collaborate in providing ongoing health care.”33

Findings indicate that terminology used to describe health care teams refers in some instances to the structural component of a team; for example, Gibbon et al25 use the term multiprofessional to describe teams in their study. Other findings indicate that terminology reflects the way in which teams collaborate. Delva et al31 use the term interdisciplinary to define the collaborative ways in which groups of professionals work together to develop processes and plans for patients. Shaw’s32 use of the term interprofessional, as defined by D’Amour and Oandasan,34 encompasses both dimensions of collaboration and professions working together (refer Table 1). These examples highlight inconsistencies relating to how terminology is used in the literature.

Regardless of the terms used and regardless of whether the terminology describes members of different professions working together in a team or the way in which team members collaborate, all included journal articles refer to the structural composition of health care teams. Teams are composed of members from a range of professional backgrounds and disciplines (Table 1). Doctors and nurses are members of all health care teams featured in the included literature. Generally, teams also include a range of allied health professionals and other specialist health professionals, depending on the health area and setting in which the teams operate.

A number of studies also include laypeople as members of health care teams. Delva et al31 include receptionists, secretaries, and administrative staff as members of interdisciplinary teams in primary care teaching practices. A study by Mills et al35 includes indigenous health service managers and district health service managers as members of interprofessional health care teams in remote areas of Queensland, Australia. These positions are held by both health and non-health professionals. Chaplains are included as members of interdisciplinary geriatric and palliative care teams in the study by Goldsmith et al.29 Medication and medication management are key elements in the treatment of most health conditions; pharmacists, however, are included as health care team members in only three30,32,36 of the 17 articles included in this review.

Almost all of the journal articles include definitions of health care teams that reflect a provider-centric perspective. Of the 17 articles, only one32 includes a definition that refers to the participation of patients. Other definitions that refer to patients tend to reflect a traditional model of care in which health professionals are active participants and patients are passive recipients of care. For example, in the article by Atwal and Caldwell,24 “team members […] make contributions to patient care”; in the article by Chan et al,27 “a leader […] takes responsibility for overall patient care”; and in the article by Molleman et al,36 “care providers collectively [discuss] a patient leading to […] decision-making and action.” Conversely, D’Amour and Oandasan’s34 definition of interprofessional, as adopted by Shaw,32 suggests that patients are encouraged to play an active role in teams, as teams “[seek] to optimize the patient’s participation.”

Discussion

Thylefors et al37 assert that, in the broader literature, interprofessional, multiprofessional, interdisciplinary, and multidisciplinary appear to be the terms most frequently used to describe health care teams. Although standardized definitions for each term have not been broadly adopted, the Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel,38 in a 2011 report on collaborative practice, recommends terminology and operational definitions around interprofessional team work. Additionally, conceptual frameworks that situate teams on a collaborative continuum also provide guidance around terminology usage.39,40 Nonetheless, the broader literature shows some generally accepted features of commonly used terminology. The prefix “multi” means “more than one; many.”41 Terminology prefixed by “multi” generally refers to team members from different disciplines working parallel to one another to treat clients. Members share information but do not necessarily share common understandings, and the group does not generally follow formal processes.17,26,42,43

The prefix “inter” means “between; among […] mutually; reciprocally.”41 The literature suggests that interprofessional and interdisciplinary health care teams tend to have more formal structures, such as shared decision-making and conflict resolution processes. Members work interdependently to pool their knowledge in order to achieve a common goal that results in more than the sum of its parts.12,15,17,42,43 The notions of interdependence and shared decision making feature in numerous definitions; however, in each instance the authors use the term multidisciplinary (refer Table 1 36,44,45). These discrepancies support extant literature that highlights inconsistencies in terminology usage and interpretations.8,15–19,46,47

The terms interprofessional, multiprofessional, interdisciplinary, and multidisciplinary are terms frequently used to describe health care teams. However, these terms are not always defined. A particular case in point is an article by Maslin-Prothero.48 Multidisciplinary teams are referred to 31 times in the article without the author once defining what is meant by the term “multidisciplinary team” or identifying team members. The reader does not know who the members of the team are or how the author defines the term multidisciplinary. Well-read scholars may quickly assume a definition based on prior knowledge, regardless of its fit with the type of team referred to in the text. By authors and editors making an assumption that the reader will know what the term used means, they are neglecting the fact that a broad audience, including students, clinicians, policy makers, and academics, access published research. Providing definitions to key terminology used in both published and gray literature enriches the reader’s experience.

Analysis of literature included in this review within a broader literature context highlights factors that may influence terminology usage. Of the three Australian studies included in this review, two relate to chronic disease, and in both instances the articles use the term multidisciplinary.27,28 In contrast, US studies in the areas of geriatric, palliative, and elder care feature the term interdisciplinary.11,29,30

Use of the term multidisciplinary in the context of the Australian studies included in this review27,28 reflects Australian policy decisions. For example, multidisciplinary care and multidisciplinary teams are features of most chronic disease strategies in Australia.49–53 However, in these strategies reference to multidisciplinary care and multidisciplinary teams is generally only in relation to the structural dimension of professional representation and, in the case of the strategy in New South Wales,51 to the setting in which teams work. The strategy in Queensland52 is the only Australian chronic disease strategy to provide a specific definition of multidisciplinary teams.

The Australian Capital Territory chronic disease strategy54 refers to interprofessional teams. The key feature that differentiates the interprofessional teams referred to in this particular strategy from the multidisciplinary teams referred to in the other State strategies and in the Australian national strategy is the inclusion of the consumer “as a key member of the care team.”

The use of the term interdisciplinary in US studies relating to geriatric, palliative, and elder care reflects training and care models used in these specialty health areas and highlights linkages between training and practice.11,29,30 The importance of providing an interdisciplinary training environment to promote interdisciplinary care models is best evidenced in the area of geriatrics. In 1997 the John A Hartford Foundation funded the development of eight national Geriatric Interdisciplinary Team Training programs in the United States, and this led to approximately 1800 students and 150 practicing health professionals being trained in this area.16,55

Approaches to both geriatric and palliative care are grounded in an interdisciplinary/biopsychosocial care model.29,56 This model promotes holistic, client-focused care delivered by interdisciplinary teams, and it is an integral component of the philosophy of care used in these specialty areas.56,57

So just how important is the labeling of health care teams? McCallin8 contends, “it is possible that the labels assigned to people working together […] are relatively unimportant,” particularly when terminology does not reflect the way in which team members interact and deliver care.

However, as Ovretveit58 cautions, current issues relating to terminology usage arise when designing and improving teams, as “people use the same word to mean something different.” Holmes et al16 consider that “efforts to understand teams fully are hampered due to the diversity of terms in which they are described and conceptualized […] definitional clarity […] [is therefore a] perquisite [sic] to further research on teams.” Adopting an overarching term such as “team-based care,” as defined by Mitchell et al,9 is also worth serious consideration. An over arching term that encompasses the principles of team care may well alleviate the need to label specific teams, thereby avoiding inconsistencies in terminological usage.

Consideration of these comments and the findings of this literature review suggest that either the development of a common understanding of current terminology or the adoption of an overarching term to describe health teams would be valuable and would support consistency in the use of terminology in policy, education, training, clinical practice, and research.

Limitations of the review

The articles included in this review were published between 2000 and 2011. A search strategy using a broader time frame may provide evidence of the influence of historical socialization patterns in terminology usage, as McCallin8 suggests. Because of the large number of articles sourced and the pace of health care changes, the authors elected to limit the literature search to this time frame. This review also included Refining search strategies, which required journal articles to include a definition of terminology used and a list of health care team members. A quantitative study of terminology usage that excludes Refining search strategies may provide a broader picture of terminology usage and significant evidence of inconsistencies in terminology usage referred to in the broader literature. Additionally, the use and definition of specific terms may differ more extensively between countries and health systems than those referred to in this review.

Conclusion

As population health care needs change, the trend towards teams of health professionals from various disciplines working together to deliver coordinated client care is undeniable. This review demonstrates that a range of terms – interprofessional, multiprofessional, interdisciplinary, and multidisciplinary – are used to describe health care teams. Multidisciplinary is most frequently used to describe health care teams. Patterns of use of the term interdisciplinary are clearly identified in the US geriatric care literature, while the use of multidisciplinary in the two Australian chronic disease studies is reflective of Australian state and national strategies.

It is now more than a decade since Ovretveit58 concluded that research, discussion, and decision making around “which type of team is best for a particular purpose and setting” requires stakeholders to be able to describe a team. The growing emphasis on interprofessional education and learning within health care and the development of recommended operational definitions and conceptual collaborative frameworks to guide terminology usage, may result in shared definitions that are used in both education and practice. However, the terminology used in national policies and strategies influences the terminology used in funding applications, and the researchers who submit these applications are employed in the tertiary institutions educating the future health workforce.

Stakeholders across the entire health care continuum share responsibility for developing and consistently using terminology that is both common and meaningful. Notwithstanding some congruence in terminology usage, this review highlights inconsistencies in the literature and suggests that broad debate among policy makers, clinicians, educators, researchers, and consumers is still required to reach useful consensus.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Australia’s Health 2008. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lemieux-Charles L, McGuire W. What do we know about health care team effectiveness? A review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(3):263–300. doi: 10.1177/1077558706287003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission . A Healthier Future for All Australians: Final Report June 2009. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sierchio GP. A multidisciplinary approach for improving outcomes. J Infus Nurs. 2003;26(1):34–43. doi: 10.1097/00129804-200301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagin CM. Collaboration between nurses and physicians: no longer a choice. Acad Med. 1992;67(5):295–303. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Detsky AS, Naylor CD. Canada’s health care system: reform delayed. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(8):804–810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr035304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xyrichis A, Lowton K. What fosters or prevents interprofessional team-working in primary and community care? A literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(1):140–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCallin A. Interdisciplinary practice – a matter of teamwork: an integrated literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10(4):419–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2001.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell P, Wynia M, Golden R, et al. Core Principles and Values of Effective Team-Based Health Care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Addison C. Future provision of medical services: report of the Medical Consultative Council for England. Br Med J. 1920;1(3100):739–743. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.3100.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black K. Advance directive communications practices: social worker’s contributions to the interdisciplinary health care team. Soc Work Health Care. 2005;40(3):39–55. doi: 10.1300/J010v40n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connor SR, Egan KA, Kwilosz DM, Larson DG, Reese DJ. Interdisciplinary approaches to assisting with end-of-life care and decision making. Am Behav Sci. 2002;46(3):340–356. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. J Interprof Care. 1989;4(1):37–53. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamberlain-Salaun J, Mills J, Davis N.The general practice team and allied health professionals Caltabiano ML, Ricciardelli L.Applied Topics in Health Psychology Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012505–516. [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Amour D, Ferrada-Videla M, San Martin Rodriguez L, Beaulieu MD. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: core concepts and theoretical frameworks. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):116–131. doi: 10.1080/13561820500082529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes D, Fairchild S, Hyer K, Fulmer T. A definition of geriatric interdisciplinary teams through the application of concept mapping. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2003;23(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCallin A. Interprofessional practice: learning how to collaborate. Contemp Nurse. 2005;20(1):28–37. doi: 10.5172/conu.20.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell PH. What’s in a name? Multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary. J Prof Nurs. 2005;21(6):332–334. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schofield RF, Amodeo M. Interdisciplinary teams in health care and human services settings: are they effective? Health Soc Work. 1999;24(3):210–219. doi: 10.1093/hsw/24.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider Z, Whitehead D, Elliott D.Nursing and Midwifery Research: Methods and Appraisal for Evidence-Based Practice 3rd edSydney, Australia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whittemore R, Knaf K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solheim K, McElmurry BJ, Kim MJ. Multidisciplinary teamwork in US primary health care. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(3):622–634. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atwal A, Caldwell K. Nurses’ perceptions of multidisciplinary team work in acute health-care. Int J Nurs Pract. 2006;12(6):359–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2006.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibbon B, Watkins C, Barer D, et al. Can staff attitudes to team working in stroke care be improved? J Adv Nurs. 2002;40(1):105–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kvarnström S. Difficulties in collaboration: a critical incident study of interprofessional healthcare teamwork. J Interprof Care. 2008;22(2):191–203. doi: 10.1080/13561820701760600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan BC, Perkins D, Wan Q, et al. Team-link project team Finding common ground? Evaluating an intervention to improve teamwork among primary health-care professionals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22(6):519–524. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzq057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cioff J, Wilkes L, Cummings J, Warne B, Harrison K. Multidisciplinary teams caring for clients with chronic conditions: experiences of community nurses and allied health professionals. Contemp Nurse. 2010;36(1–2):61–70. doi: 10.5172/conu.2010.36.1-2.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldsmith J, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Rodriguez D, Sanchez-Reilly S. Interdisciplinary geriatric and palliative care team narratives: collaboration practices and barriers. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(1):93–104. doi: 10.1177/1049732309355287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuder LC, Gairola GA, Hamilton CC. Development of rural interdisciplinary geriatrics teams. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2001;21(4):65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delva D, Jamieson M, Lemieux M. Team effectiveness in academic primary health care teams. J Interprof Care. 2008;22(6):598–611. doi: 10.1080/13561820802201819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw SN. More than one dollop of cortex: patients’ experiences of interprofessional care at an urban family health centre. J Interprof Care. 2008;22(3):229–237. doi: 10.1080/13561820802054721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haggerty J, Burge F, Lévesque J, et al. Operational definitions of attributes of primary health care: consensus among Canadian experts. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(4):336–344. doi: 10.1370/afm.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Amour D, Oandasan I. Interprofessionality as the field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: an emerging concept. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):8–20. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mills JE, Francis K, Birks M, Coyle M, Henderson S, Jones J. Registered nurses as members of interprofessional primary health care teams in remote or isolated areas of Queensland: collaboration, communication and partnerships in practice. J Interprof Care. 2010;24(5):587–596. doi: 10.3109/13561821003624630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molleman E, Broekhuis M, Stoffels R, Jaspers F. How health care complexity leads to cooperation and affects the autonomy of health care professionals. Health Care Anal. 2008;16(4):329–341. doi: 10.1007/s10728-007-0080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thylefors I, Persson O, Hellström D. Team types, perceived efficiency and team climate in Swedish cross-professional teamwork. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(2):102–114. doi: 10.1080/13561820400024159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel Washington DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boon H, Verhoef M, O’Hara D, Findlay B. From parallel practice to integrative health care: a conceptual framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuehn AF. The kaleidoscope of collaborative practice. In: Joel LA, editor. Advanced Practice Nursing: Essentials for Role Development. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Company; 2004. pp. 301–335. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oxford Dictionaries [homepage on the Internet] Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012Available from: http://oxforddictionaries.comAccessed November 8, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheehan D, Robertson L, Ormond T. Comparison of language used and patterns of communication in interprofessional and multidisciplinary teams. J Interprof Care. 2007;21(1):17–30. doi: 10.1080/13561820601025336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sorrells-Jones J. The challenge of making it real: interdisciplinary practice in a “seamless” organization. Nurs Adm Q. 1997;21(2):20–30. doi: 10.1097/00006216-199702120-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Molleman E, Broekhuis M, Stoffels R, Jaspers F. Consequences of participating in multidisciplinary medical team meetings for surgical, nonsurgical, and supporting specialties. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(2):173–193. doi: 10.1177/1077558709347379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spencer J, Cooper H. A multidisciplinary paediatric diabetes health care team: perspectives on adolescent care. Pract Diab Int. 2011;28(5):212–215. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark PG. A typology of interdisciplinary education in gerontology and geriatrics: are we really doing what we say we are? J Interprof Care. 1993;7(3):217–228. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mariano C. The case for interdisciplinary collaboration. Nurs Outlook. 1989;37(6):285–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maslin-Prothero S. The role of the multidisciplinary team in recruiting to cancer clinical trials. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2006;15(2):146–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Health Priority Action Council . National Chronic Disease Strategy. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Northern Territory Government . Northern Territory Chronic Conditions Prevention and Management Strategy 2010–2020. Darwin, Australia: Department of Health and Families; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 51.New South Wales Department of Health . NSW Chronic Care Program: Rehabilitation for Chronic Disease – Volume 1. Sydney, Australia: Department of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Queensland Health . Queensland Strategy for Chronic Disease 2005–2015 Framework for Self-Management 2008–2015. Brisbane, Australia: Queensland Government; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 53.South Australia, Department of Health, Statewide Service Strategy Division Chronic Disease Action Plan for South Australia 2009–2018 Adelaide: South Australia, Department of Health; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Australian Capital Territory Department of Health (ACT Health) ACT Chronic Disease Strategy 2008–2011. Canberra: ACT Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fulmer T, Hyer K, Flaherty E, et al. Geriatric interdisciplinary team training program: evaluation results. J Aging Health. 2005;17(4):443–470. doi: 10.1177/0898264305277962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muir JC, Wheeler MS, Carlson J, Littlefield NW. Multidimensional patient assessment. In: Berger AM, Shuster JL, Von Roenn JH, editors. Principles and Practice of Palliative Care and Supportive Oncology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 507–516. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crawford GB, Price SD. Team working: palliative care as a model of interdisciplinary practice. Med J Aust. 2003;179(Suppl 6):S32–S34. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ovretveit J. Five ways to describe a multidisciplinary team. J Interprof Care. 1996;10(2):163–171. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keleher H. Why primary health care offers a more comprehensive approach to tackling health inequalities than primary care. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2001;7(2):57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim MJ, Cho Chung HI, Ahn YH. Multidisciplinary practice experience of nursing faculty and their collaborators for primary health care in Korea. Asian Nurs Res. 2008;2(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1976-1317(08)60026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]