Abstract

Macrophages themselves are a heterogeneous mixture of cells which mediate their effects not only through phagocytosis but also through the production of various soluble factors such as cytokines and chemokines. The most important function of macrophages is the defense of the body against pathogen aggressions. However, when recruited within neoplastic tissues, tumor-associated macrophages polarize differently and do not predominantly exert their immune function but rather favor tumor growth and angiogenesis.

Keywords: Macrophages, cancer, tumor associated marcophages

INTRODUCTION

Elie Metchnikoff in 1892 proposed his “cellular (phagocytic) theory of immunity” which stated that white blood cells were critical elements of the immune system which protected individuals from invading pathogenic organisms.

Human macrophages function in both nonspecific defense (innate immunity) as well as help initiate specific defense mechanisms (adaptive immunity) of vertebrate animals. They stimulate lymphocytes and other immune cells to respond to pathogens. Macrophages can be identified by specific expression of a number of proteins including CD14, CD11b, F4/80 (mice)/EMR1 (human), Lysozyme M, MAC-1/MAC-3, and CD68 by flow cytometry or immunohistochemical staining. Macrophages are believed to help cancer cells proliferate as well. They are attracted to oxygen-starved (hypoxic) tumor cells and promote chronic inflammation. Inflammatory compounds such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) released by the macrophage activate the gene switch nuclear factor-kappa B. NF-kB then enters the nucleus of a tumor cell and turns on production of proteins that stop apoptosis and promote cell proliferation and inflammation

TAMS RECRUITED TO TUMOR

Macrophages—TAMs [tumor-associated macrophages]—are recruited to tumors by growth factors and chemokines, which are often produced by the cancer cells and stroma cells in the tumor. Macrophages are an important component of the innate immune system and are derived from myeloid progenitor cells called the colony-forming unit granulocyte-macrophage in the bone marrow.[1]

These progenitor cells develop into promonocytes and then differentiate into monocytes. Monocytes then migrate through the circulatory system into almost all tissues of the body, where they differentiate into tissue macrophages.[2] Examples of tissue macrophages include Kupffer cells in the liver and alveolar macrophages in the lung. It is thought that TAMs are mostly derived from peripheral blood monocytes recruited directly to the tumor, rather than derived from local tissue macrophages.[3] A number of monocyte chemoattractants derived from tumors have been shown to correlate with increased TAMs numbers in many human tumors.[4] Such monocyte chemoattractants include CSF-1, the CC chemokines, CCL2 (formally monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), CCL3, CCL4, CCL5 and CCL8, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha (MIP-1α), and macrophage migration inhibition factor (MIF).

TAM: ITS ROLE IN CANCER INVASION AND METASTASIS

Clinical studies have shown a correlation between the number of TAMs and poor prognosis for breast, prostate, ovarian, cervical, endometrial, esophageal, and bladder cancers.[3] TAMs are also associated with increased angiogenesis or lymph node metastasis in cancer tissues. These observations accord with the results of animal studies using macrophage-depleted mice to investigate the role of macrophages in tumor progression.[1] The data for lung cancer, gastric cancer, and glioma are controversial.[3] TAMs density correlated positively with tumor IL-8 expression and intratumoral microvessel density in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and TAMs level was also associated with short relapse-free patient survival.[4]

The cytokine profiles of microenvironment and localization of TAMs reside may influence the function of TAMs and thereafter the prognostic value of TAMs.[5] Shih et al. particularly paid attention to counting macrophages within gastric carcinoma stroma and islets and found that tumor islet-infiltrating macrophages (indicated TAMs which invaded into tumor nest) were associated with better survival.[3] Voronov et al, Schioppa et al. recently evaluated the relationship of tumor islet macrophage and patients’ survival in NSCLC and showed that tumor islet macrophage density and tumor islet/stromal macrophage ratio emerged as favorable independent prognostic indicators in patients with NSCLC. In contrast, increasing stromal macrophage density was an independent predictor for reduced survival.[5,6]

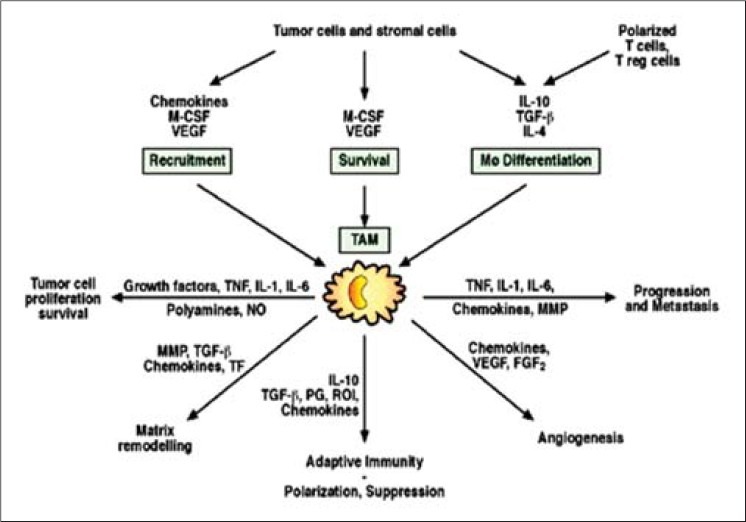

The findings indicate that the exact microanatomic localization of these inflammatory cells is critical in determining the relationship to prognosis. There was some experimental evidence to support this point. Macrophages were attractive by colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) expressed by cancer cells. Shih et al. reported that most of the mice implanted with glioma cells expressing cell surface-bound CSF-1 survived; in contrast, all mice that were implanted with glioma cells expressing soluble form of CSF1 died [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Illustrating functions, role, and products of macrophages

INTERACTION OF TAMs AND CANCER CELLS ENHANCES INVASIVENESS OF CANCER

TAMs promote cancer metastasis through several mechanisms, including:

Promotion of angiogenesis,

Induction of tumor growth, and

Enhancement of tumor cell migration and invasion.

The mechanisms of TAMs-promoting angiogenesis and tumor growth have been well reviewed by several articles.[1,2,7] Several studies have demonstrated the association between increased tumor vascularity and macrophage infiltration in several human cancers,[8–10] suggesting that TAMs enhance the angiogenic potential of tumors. Macrophage infiltration has been shown to correlate with vessel density in endometrial, ovarian, breast, and central nervous system malignancies. The potential angiogenesis factors secreted by TAMs have been shown to include chemokines (IL-8, MIF, etc.), VEGF, TNF-α, and thymidine phosphorylase. TAMs also produce a wide variety of growth factors that can stimulate cancer growth.[10]

TAMS-DERIVED PROTEASES

In mammary tumors, macrophages are present in areas of invasion and basement membrane breakdown during the development of early-stage cancer regulation of proteolytic enzymes in macrophages present in these locations indicates that TAMs could be involved in the invasion of tumor cells into surrounding normal tissue.[11]

It has been generally assumed that tumor cell-derived matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are important to allow cancer cells to penetrate the basement membrane and invade the ECM and metastasize. MMPs are a family of matrix degrading enzymes including collagenase (MMP-1), gelatinase A (MMP-2), stromelysin (MMP-3), matrilysin (MMP-7), gelatinase B (MMP-9), and other MMPs.[12] The MMP expression has been implicated in tumor progression through enhancing angiogenesis, tumor invasion, and metastasis.

TAMs have been reported to correlate with the metastatic potential of a variety of human cancers, and they have also been shown to be a major source of MMP-9.[12] In addition, urokinase-type plasminogen activator is a serine protease synthesized by TAMs in various human tumor types. The levels of urokinase-type plasminogen activator have been shown to correlate with reduced relapse-free and overall survival in cancer. TAMs can also secrete cysteine-type lysosomal proteases. Traditionally, lysosomal cysteine proteases are considered to execute nonspecific bulk proteolysis within the lysosomes. However, there is growing evidence that lysosomal proteases are secreted extracellularly in cancer. Vasiljeva et al. demonstrated that macrophages increased cathepsin B (one of cysteine-type lysosomal protease) expression on being recruited to the tumor and thus promoted tumor growth and lung metastasis of polyoma virus middle T oncoprotein (PyMT)-induced breast cancer.

Lin et al. used transgenic mouse model to study the effect of depleting macrophage in a breast cancer. In this model, mammary tumors are initiated by the mammary epithelial restricted expression of the PyMT and the mice are homozygous for a null mutation in the CSF-1. Depletion of CSF-1 markedly decreased the infiltration of macrophages at the tumor site and macrophage depletion resulted in slower progression of preinvasive lesions to malignant lesions and reduced formation of lung metastases.[13] Similarly, using small interfering RNA to inhibit CSF-1 expression in MCF-7 xenografts showed that lower numbers of TAMs were accompanied by a marked reduction in tumor growth and increase of mice survival. Monocytes were recruited into tumor, differentiated into TAMs, and accumulated in hypoxic area of tumor. TAMs respond to hypoxia through upregulation of transcriptional factors such as hypoxia-inducing factors 1 and 2 which activate many mitogenic, angiogenic, and proinvasive genes.[3]

PARACRINE SIGNALING NETWORKS BETWEEN TAMS AND CANCER CELLS

Ostrand-Rosenberg et al. have reported that coculture of macrophage with breast cancer cells lead to upregulated production of TNF-α and MMP-2, -3, -7, and -9 in the macrophages subsequently enhanced cancer cells invasion. It was shown that coculture of stimulated macrophages with breast cancer cells led to TNF-dependent activation of c-Jun-NH2-kinase and nuclear factor-B signaling pathways in cancer cells. Downstream targets in tumor cells included MIF and extracellular MMP inducer (EMMPRIN). These proteins then act in turn to enhance the local release of MMPs by macrophages.[1,2]

It is notable that TAMs promote the proliferation of tumor cells directly by secreting growth factors. They also participate in tumor progression by acting on endothelial cells and thus promoting the neovascularization of the tumor. Tumor-associated macrophages are indeed key protagonists during angiogenesis and promote each step of the angiogenesis cascade.[14] It may be observed that NK cells and dendritic cells are also activated along with macrophages. But due to immune escape, these cells are incapable of killing tumor cells.

PHENOTYPES OF MACROPHAGES

The role of macrophages has been debated, as some studies were not consistent with the prevailing opinion. It was reported that no association between macrophage count and outcome in NSCLC.[15]

Furthermore, Ostrand-Rosenberg et al. reported that peritumoral infiltration of macrophages in colorectal cancer was associated with less lymph node metastasis and good prognosis.[1] These conflicting results may reflect the different methods of assessment used, and in some cases differences in the number, grade, and stage of tumors and the small sample size included in some studies. However, there is a fundamental question about these conflicting clinical observations, i.e., are all TAMs the same?

Macrophages are released from the bone marrow as immature monocytes. After circulating in the blood, they are recruited by chemokines into the tissue and undergo differentiation into macrophages[7] and they can exhibit a variety of phenotypes and functions, depending on the physiologic or pathologic situation to which they are recruited. These various functions, essential for tissue remodeling, inflammation, and immunity, include endocytosis of foreign and necrotic debris, cytotoxicity, and secretion of more than 100 different substances.[1] Indeed, depending on their activation, macrophages are able to secrete growth factors, cytokines, proteases, or complement components. Moreover, specialization and activation of these cells are largely influenced by local stimuli. These can be delivered by cytokines, by the engagement of adhesion molecules, or by macrophage interaction with pathogens.[3]

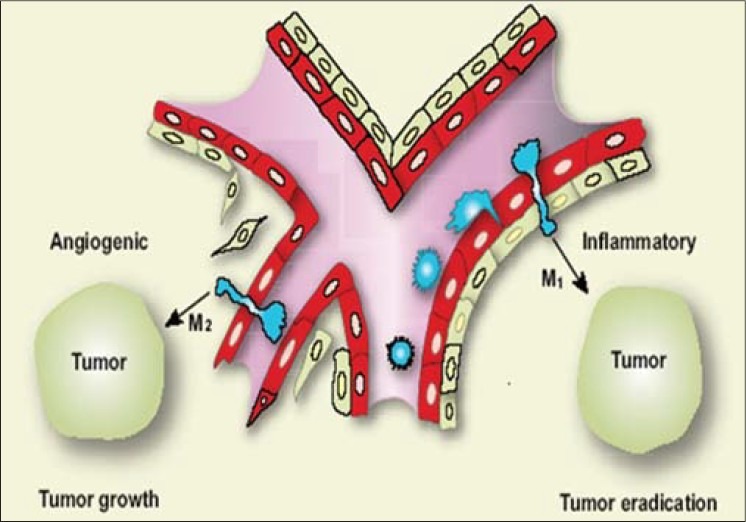

On the basis of their activation state, macrophages can be referred to as Type I or Type II cells. The differences displayed by macrophages in term of receptor expression, cytokine production, and functions define these two populations. Numerous studies have permitted classifying Type I macrophages (M1) as cells capable of producing large amounts of proinflammatory cytokines, expressing high levels of MHC molecules, and implicated in the killing of pathogens and tumor cells. The M1 macrophages induce antitumor responses as a result of secretion of IFN-γ, IL-12, or TNF-α. They are identified by using the IHC marker MIC-1.

In contrast, Type II macrophages (M2) moderate the inflammatory response, eliminate cell wastes, and promote angiogenesis and tissue remodeling. M2 macrophages suppress immune response as a result of secretion of TGF-β or IL-10 and stimulate angiogenesis and tumor growth as a result of secretion of IL-17, IL-23, vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs), fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), or endothelium. They are identifies using IHC marker MIC-2 [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Macrophages can further differentiate into angiogenic (M2) or inflammatory (M1) phenotypes, depending on the environment of the tumor

The macrophages present in neoplastic tissues which are referred to as TAMs mainly belong to the M2 population.[16] Either macrophage types or their monocyte progenitors are recruited to the tumor mostly from the blood circulation, although macrophages may also migrate to tumors from the surrounding tissue.[17]

CHEMOKINES IMPLICATED IN THE RECRUITMENT OF MACROPHAGES INTO THE TUMOR

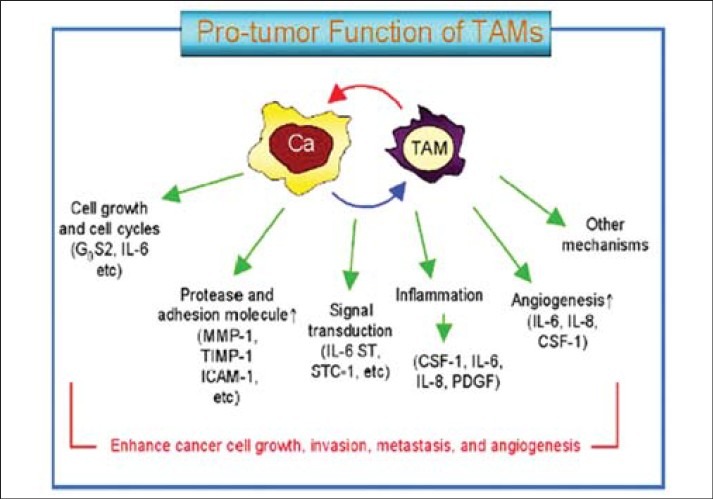

Most of monocytes, which become TAMs in the tumor, are attracted from the circulation into the tumor mass by the chemokines CCL2 (MCP-1) and CCL5 (RANTES).[2,18–20] CCL2 has been described first as a tumor-derived chemotactic factor for monocytes and isolated from culture supernatants of human and murine tumor cell lines. It can be detected in several tumors, such as sarcomas, gliomas, breast, and ovary carcinomas and melanomas. CCL2-deficient mice display abnormalities in monocyte recruitment in an inflammatory model, as well as delayed wound angiogenesis.[21] However, the number of macrophages within the wounded site is not affected by the absence of CCL2, suggesting that the monocyte recruitment into wounds is independent of the chemokine CCL2. Nevertheless, one could not exclude that CCL2 plays a critical role in healing wounds by activating macrophages or by acting on distinct cell types other than macrophages[22,23] [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Illustrating factors for invasion metastasis an angiogenesis

ROLE OF TAMS IN TUMOR GROWTH

The functions of TAMs within the tumor site are various and sometimes paradoxal. Initially, it was considered that the main function of TAMs was to exert direct, cytotoxic effects on tumor cells, and to phagocyte apoptotic cells and waste products. Now it became clear that monocytes can differentiate into “friendly” M1 macrophages, which initiate tumor rejection or “foe” M2 TAMs, which stimulate tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis.[24]

STIMULATION OF TUMOR GROWTH BY M2 TAMS

By the means of their secretory products, M2 TAMs stimulate tumor growth. This can be done directly by producing cytokines able to stimulate the proliferation of tumor cells or indirectly, by stimulating endothelial cell proliferation and angiogenesis. As an example, the growth of subcutaneous Lewis lung tumors is impaired in the CSF-1-deficient, macrophage-deficient mice, indicating a role for macrophages in tumor growth.[25,26]

Moreover, treatment of tumor-bearing mice with human recombinant CSF-1 corrects this impairment. M2-TAMs and tumor cells also produce immunosuppressive cytokine TGF-α which effectively blunts the antitumor response by cytotoxic T cells. Finally, TAMs have also been implicated in the proteolytic remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM), which is important at several points during multistage progression of tumors.[1,27,28]

TUMOR-ASSOCIATED M2 MACROPHAGES AND METASTASIS

The percentage of TAMs within a tumor has been positively correlated with the metastatic potential of the tumor, suggesting a role for TAMs in the distant dispersion of tumor cells. Indeed, monocytes secrete enzymes capable of degrading the ECM, such as the MMP-19 and the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR). By relaxing the connective tissue surrounding the tumor, these molecules allow tumor cells to detach from the tumor mass and to disseminate, leading to the formation of distant metastases. Moreover, by favoring angiogenesis and lymph angiogenesis, increase the availability for tumor cells to enter blood or lymphatic vessels and invade distant tissues. This is supported by the fact that tumor vessels exhibit an anarchic organization compared with normal blood vessels with immature, interendothelial junctions, and fenestrations, thus exposing tumor cells to the blood circulation.[1–3]

TAMS: TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT FOR ANGIOGENESIS

By secreting a wide range of chemokines, enzymes, and growth factors, M2 macrophages are able to promote each step of the angiogenesis cascade, leading to the formation of new, mature blood vessels It is important to state that the events leading to newly formed vessels are intricate, and macrophage secretory molecules can be implicated in different steps.

Three steps in angiogenic blood vessel formation. TAMs of the angiogenic type [M-2] produce a series of factors such as the VEGF, FGF chemokines endothelia IL-17, IL-23, or TGF-β which contribute to angiogenesis in following steps:

Induction of endothelial cell proliferation.

Production of metalloproteases, which degrade the vascular basement membrane, allowing sprouting and migration of endothelial cells into the tumor.

Tube formation and maturation of new vessel, followed by its stabilization by attaching mural cells.[9]

CONCLUSION

Macrophages are key cells in chronic inflammation. They respond to microenvironmental signals with polarized genetic and functional programs. Macrophages tune inflammation and adaptive immunity, promote cell proliferation by producing growth factors and products of the arginase pathway (ornithine and polyamines), scavenge debris by expressing scavenger receptors, and promote angiogenesis, tissue remodeling, and repair. Other than these functions, it has been confirmed in a number of studies that M2 macrophages, apart from being mediators of chronic inflammation, act as tumor promoters at distinct phases of malignant progression of gastric, mammary, lung, and liver carcinomas. Ongoing research is in process with special emphasis on involvement of macrophages in oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Macrophages and tumor development. Cancer Immunol. 2008:131–55. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piconese S, Colombo MP. Regulatory T Cells in Cancer /Tumor-Induced Immune Suppression. Springer. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shih JY, Yuan A. Tumor-associated macrophage: Its role in cancer invasion and metastasis. J Cancer Mol. 2006;2:101–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul AG. Eukaryon. Vol. 1. Lake Forest College; 2005. Jan 4-5, NF-kB: A novel therapeutic target for cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voronov E, Shouval DS, Krelin Y, Cagnano E, Benharroch D, Iwakura Y, et al. IL-1 is required for tumor invasiveness and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2645–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437939100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schioppa T, Uranchimeg B, Saccani A, Biswas SK, Doni A, Rapisarda A, et al. Regulation of the Chemokine Receptor CXCR4 by Hypoxia. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1391–402. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apte RN, Dotan S, Elkabets M, White MR, Reich E, Carmi Y, et al. The involvement of IL-1 in tumorigenesis, tumor invasiveness, metastasis and tumor-host interactions. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:387–408. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin EY, Pollard JW. Role of infiltrated leucocytes in tumor growth and spread. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2053–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamb GW, McMillan DC, Ramsey S, Aitchison M. The relationship between the preoperative systemic inflammatory response and cancer-specific survival in patients undergoing potentially curative resection for renal clear cell cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:781–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshioka T, Miyamoto M, Cho Y, Ishikawa K, Tsuchikawa T, Kadoya M, et al. Infiltrating regulatory T cell numbers is not a factor to predict patient's survival in esophageous squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1258–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fedele S. Diagnostic aids in the screening of oral cancer. Head Neck Oncol. 2009;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 2004;21:137–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bock F, Onderka J, Dietrich T, Bachmann B, Pytowski B, Cursiefen C. Blockade of VEGFR3-signalling specifically inhibits lymphangiogenesis in inflammatory corneal neovascularization. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:115–9. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0683-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mueller MM. Inflammation and angiogenesis: Innate immune cells as modulators of tumor vascularization. [cited in 2011]. Available from: Springer%20Verlag%20E-Books/Pruefung/978-3-540-33177-3_Chapter_20.pdf .

- 15.Wald O, Izhar U, Amir G, Avniel S, Bar-Shavit Y, Wald H, et al. CD4_CXCR4highCD69+ T cells accumulate in lung adenocarcinoma. J Immunol. 2006;177:6983–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergman MP, Engering A, Smits HH, van Vliet SJ, van Bodegraven AA, Wirth HP, et al. Helicobacter pylori modulates the T helper cell 1/T helper cell 2 balance through phase-variable interaction between lipopolysaccharide and DC-SIGN. J Exp Med. 2004;200:979–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott KA, Arnott CH, Robinson SC, Moore RJ, Thompson RG, Marshall JF, et al. TNF-α regulates epithelial expression of MMP-9 and integrin α-β6 during tumour promotion. A role for TNF-α in keratinocyte migration? Oncogene. 2004;23:6954–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Theoharides TC, Conti P. Mast cells: The Jekyll and Hyde of tumor growth. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alkhabuli JO. Significance of neo-angiogenesis and immuno-surveillance cells in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Libyan J Med. 2007;2:30–9. doi: 10.4176/070110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin EY, Pollard JW. Role of infiltrated leucocytes in tumour growth and spread. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2053–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, Garlanda C, Mantovani A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: Links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1073–81. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Portal C, Allavena P, Sica A. Linking inflammation reactions to cancer: Novel targets for therapeutic strategies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;610:112–27. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-73898-7_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halin C, Detmar M. An unexpected connection: Lymph node lymphangiogenesis and dendritic cell migration. Immunity. 2006;24:129–31. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamagna C, Aurrand-Lions M, Imhof BA. Dual role of macrophages in tumor growth and angiogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:705–13. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Voronov E, Shouval DS, Krelin Y, Cagnano E, Benharroch D, Iwakura Y, et al. IL-1 is required for tumor invasiveness and angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2645–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437939100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jamieson NB, Glen P, McMillan DC, McKay CJ, Foulis AK, Carter R, et al. Systemic inflammatory response predicts outcome in patients undergoing resection for ductal adenocarcinoma head of pancreas. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:21–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sminia P, Stoter TR, van der Valk P, Elkhuizen PH, Tadema TM, Kuipers GK, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and epidermal growth factor receptor in primary and recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:653–61. doi: 10.1007/s00432-005-0020-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balkwill F, Charles KA, Mantovani A. Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]