Abstract

Lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)) is an LDL-like molecule consisting of an apolipoprotein B-100 (apo(B-100)) particle attached by a disulphide bridge to apo(a). Many observations have pointed out that Lp(a) levels may be a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. Lp(a) inhibits the activation of transforming growth factor (TGF) and contributes to the growth of arterial atherosclerotic lesions by promoting the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells and the migration of smooth muscle cells to endothelial cells. Moreover Lp(a) inhibits plasminogen binding to the surfaces of endothelial cells and decreases the activity of fibrin-dependent tissue-type plasminogen activator. Lp(a) may act as a proinflammatory mediator that augments the lesion formation in atherosclerotic plaques. Elevated serum Lp(a) is an independent predictor of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. Furthermore, Lp(a) levels should be a marker of restenosis after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, saphenous vein bypass graft atherosclerosis, and accelerated coronary atherosclerosis of cardiac transplantation. Finally, the possibility that Lp(a) may be a risk factor for ischemic stroke has been assessed in several studies. Recent findings suggest that Lp(a)-lowering therapy might be beneficial in patients with high Lp(a) levels. A future therapeutic approach could include apheresis in high-risk patients in order to reduce major coronary events.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases cause 3% of all deaths in North America being the most common cause of death in European men under 65 years of age and the second most common cause in women. These facts suggested us to consider new strategies for prediction, prevention, and treatment of cardiovascular disease [1]. Inflammatory mechanisms play a central role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and its complications [2]. It has been demonstrated that atherogenic lipoproteins such as apo(B-100), oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL), remnant lipoprotein (beta-VLDL), and lipoprotein(a) play a critical role in the proinflammatory reaction. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) is antiatherogenic lipoproteins that exert anti-inflammatory functions [3–5]. Plasma LDL cholesterol is a well-established predictor of coronary artery disease (CAD), and many observations have pointed out that Lp(a) and apolipoprotein(a) (apo(a)) levels may be risk factors for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [6–8].

2. Native Lp(a)

Lp(a) is an LDL-like molecule consisting of an apolipoprotein B-100 (apo(B-100)) particle attached by a disulphide bridge to apo(a). Lp(a) plasma concentrations are controlled by the apo(a) gene located on chromosome 6q26-27 [9]. The unique character of Lp(a) is based on the apo(a) highly glycosylated protein structurally homologous to plasminogen [10]. Several published data indicated the existence of unbound forms of apo(a) in blood and urinary excretion of apo(a) fragments [11, 12]. Animal experiments showed that apo(a) serves as a distinctive marker of Lp(a) and represents an atherogenic component of Lp(a) [13]. Furthermore, apo(a) has also been reported to be correlated to coronary artery disease as well as renal disease [14–16]. Dissociation of apo(a) may lead to the exposure of an additional lysine-binding site, increasing the affinity of free apo(a) for plasmin modified fibrin, thus impeding fibrinolysis [17]. Apo(a) is a member of a family of “kringle" containing proteins, such as plasminogen, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), prothrombin, factor XII, and macrophage stimulating factor (MSF). Lp(a) shares a high degree of sequence identity with plasminogen. These similarities could explain the role of Lp(a) in thrombogenesis and as a proinflammatory factor [18]. Native Lp(a) has been shown to enhance the expression of adhesion molecules [13, 19–23]. Because of the structural homology with plasminogen, Lp(a) might have important antithrombolytic properties, which could contribute to the pathogenesis of atherothrombotic disease. For example, Lp(a) binding to immobilised fibrinogen and fibrin results in the inhibition of plasminogen binding to these substrates [24, 25]. In addition, Lp(a) competes with plasminogen for its receptors on endothelial cells, leading to diminished plasmin formation, thereby delaying clot lysis and favouring thrombosis. The high affinity of Lp(a) for fibrin provides a mechanistic basis for their frequent colocalization in atherosclerotic plaques [26, 27]. Moreover Lp(a) induces the monocyte chemoattractant (CC chemokine I-309), which leads to the recruitment of mononuclear phagocytes to the vascular wall [28, 29].

3. Oxidized Lp(a)

Lp(a) particles can suffer oxidative modification and scavenger receptor uptake, with cholesterol accumulation and foam cell formation [30], leading to atherogenesis. Oxidation of LDL and Lp(a) affects the catabolism of the lipoproteins, including changes in receptor recognition, catabolic rate, retention in the vessel wall, and propensity to accelerate atherosclerosis. Oxidative modification of apo(a) may have an influence on Lp(a) recognition by scavenger receptors of macrophages. Some studies showed that Lp(a) particles are prone to oxidation and that the increased risk of coronary artery disease associated with elevated Lp(a) levels may be related in part to their oxidative modification and uptake by macrophages, resulting in the formation of macrophage-derived foam cells [31]. The oxidative form of Lp(a) (ox-Lp(a)) might attenuate fibrinolytic activity through the reduction of plasminogen activation, might enhance PAI-1 production in vascular endothelial cells, and might impair endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Particularly, the role of ox-Lp(a) is linked to macrophages that take up ox-Lp(a) via scavenger receptor as well as oxidized LDL. Lp(a) particles are susceptible to oxidative modification and scavenger receptor uptake, leading to intracellular cholesterol accumulation and foam cell formation, which contributes further to atherogenesis [25, 32]. Morishita et al. demonstrated increased values of ox-Lp(a) in patients with coronary artery disease [33]. A study of autopsy findings demonstrated a deposition of ox-Lp(a) in the vessel margin inside the calcified areas [34]. Probably it was related to the promotion of an antifibrinolytic environment, foam cell formation, generation of a fatty streak, and an increase in smooth muscle cells. Moreover ox-Lp(a) is a potent stimulus of monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells, thus contributing to atherogenic changes in human blood vessels. Komai et al. compared the effects of oxidized lipoproteins and no oxidized lipoprotein on the progression of atherosclerosis. It was investigated the mitogenic actions of Lp(a) and ox-Lp(a) on human vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC). The results were that Lp(a) significantly stimulated the growth of human VSMC in a dose-dependent manner, whereas ox-Lp(a) showed a stronger stimulatory action on VSMC growth than native Lp(a). This study demonstrated that ox-Lp(a) has a more potent effect than native Lp(a) in developing atherosclerosis diseases [35].

4. Glycated Lp(a)

Nonenzymatic glycation of lipoprotein may contribute to the premature atherogenesis in patients with diabetes mellitus by diverting lipoprotein catabolism from nonatherogenic to atherogenic pathways. It has been observed that the proportion of apo (B-100) in glycated form was significantly higher in diabetic patients than in nondiabetic controls, and equally that plasma Lp(a) levels might be increased in diabetic patients [36]. Anyway, glycation does not appear to significantly enhance the atherogenic potential of unmodified Lp(a) [37]. The kringle of apo(a) is homologous to the kringle IV of plasminogen, and each of these kringles contains a potential site of N-linked glycosylation. The carbohydrate content of apo(a) has been determined and represents approximately 28% by weight of the protein. Peripheral levels of Lp(a) have been examined in a number of studies involving diabetic patients because Lp(a) concentration is associated with a high-risk of coronary heart disease, and diabetic patients are prone to develop coronary heart disease. It has been demonstrated that glycation enhances the production of PAI-1 and attenuates the synthesis of t-PA induced by Lp(a) in arterial and venous endothelial cells (EC). The formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and EC-mediated oxidative modification may contribute to the alterations of the generation of PAI-1 and t-PA induced by glycated Lp(a) [13]. The combination of hyperglyaemia and hyperlipoprotein(a) may reduce EC-derived fibrinolytic activity, which may promote the development of thrombosis and atherosclerosis in subjects with diabetes [36].

5. Atherogenic and Proinflammatory Mechanisms of Lp(a)

5.1. Lp(a) and Endothelial Dysfunction

As the atherosclerotic plaque progresses, growth factors and cytokines secreted by macrophages and foam cells in the plaque stimulate vascular smooth muscle cell growth and interstitial collagen synthesis [37]. Moreover, the apo(a) component of Lp(a) has been shown to enhance the expression of ICAM-1 [13]. Thus, these effects on endothelial cell function may provide mechanisms by which Lp(a) contributes to the development of atherosclerotic lesions. Reduction in nitric oxide (NO) availability also initiates the activation of matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9 [38, 39], and further it reduces inhibition of platelet aggregation [40]. Thus, endothelial dysfunction with reduced NO bioavailability, increased oxidant excess, and expression of adhesion molecules contributes not only to initiation but also to progression of atherosclerotic plaque formation and triggering of cardiovascular events. In vitro studies indicated that Lp(a) enhances the synthesis of PAI-1 by endothelial cells. PAI-1 is the main inhibitor of the fibrinolytic system [41]. Another potentially important action of Lp(a) is the reduction of activation of latent transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) by displacing plasminogen from the surfaces of macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques. In the absence of activated TGF-β, cytokines might induce smooth muscle cell proliferation and the transformation of these cells to a more atherogenic cellular phenotype [42, 43]. Furthermore, studies on cultured human umbilical vein or coronary artery endothelial cells revealed a novel effect of Lp(a) that was mediated by its apo(a) component: impairment of the barrier function of endothelial cells through cell contraction occurring as a consequence of a rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton [44]. In 1992, Cohn et al. studied the abnormalities of vascular compliance in hypertension and demonstrated that vasodilation is inhibited by ox-Lp(a). Also, they showed that elevation of ox-Lp(a) may explain the endothelial dysfunction observed in hypertensive patients because ox-Lp(a) enhanced Lp(a)-induced PAI-1 production in vascular endothelial cells [45]. However, the exact role of ox-Lp(a) is still largely unknown, and at the moment a stronger involvement of the ox-Lp(a) in atherosclerotic development and worse evolution in stroke and heart failure are just supposed. The matter of fact is that ox-Lp(a) might cause more pronounced stimulation of superoxide production, whereas native Lp(a) itself caused a moderate, dose-dependent stimulation of superoxide production. Accumulation of native Lp(a) may enhance the stimulation of ox-Lp(a), a more potent atherogenic lipoprotein, in the vessel wall [46].

5.2. Inflammation, Atherosclerosis, and Lp(a)

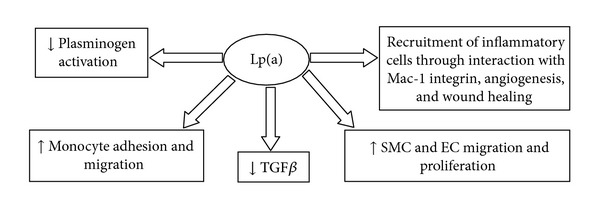

Lp(a) may act as a proinflammatory mediator that augments the lesion formation in atherosclerotic plaques [47]. Lp(a) may lead to an inflammatory process by inducing the expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells, the chemotaxis of monocytes, and the proliferation of smooth muscle cells [48]. Moreover Lp(a) can augment the production of cytokines by vascular cells, and through the autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, the inflammatory reaction may lead to a vicious cycle resulting in lesion progression [49]. Lp(a) acts on the fibrinolytic system in several ways which include the inhibition of plasminogen binding and activation, thereby impairing fibrinolytic activity and the dissolution of thrombi. High concentrations of Lp(a) might increase the risk of thrombus formation by impeding fibrinolytic mechanisms in the region of the plaque. Some mechanisms are involved into the development of atherosclerosis: Lp(a) inhibits the activation of transforming growth factor (TGF) and contributes to the growth of arterial atherosclerotic lesions by promoting the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells and the migration of smooth muscle cells to endothelial cells [50, 51]. Moreover Lp(a) inhibits plasminogen binding to the surfaces of endothelial cells and decreases the activity of fibrin-dependent tissue-type plasminogen activator. Furthermore Lp(a) increases plasminogen activator inhibitor activity in endothelial cells and promotes atherothrombosis [52]. Other functions have been related to recruitment of inflammatory cells through interaction with Mac-1 integrin, angiogenesis, and wound healing (Figure 1). However, individuals without Lp(a) or with very low Lp(a) levels seem to be healthy. Thus plasma Lp(a) is certainly not vital, at least under normal environmental conditions [53–55].

Figure 1.

Mechanisms underlying the Lp(a)-induced cardiovascular disease. Lp(a) inhibits the activation of TGF and promotes the proliferation and migration of smooth muscle cells to endothelial cells. Moreover Lp(a) inhibits plasminogen activation and decreases the activity of fibrin-dependent tissue-type plasminogen activator.

6. Lp(a) and Cardiovascular Diseases

The relationship between Lp(a) levels and the severity of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with unstable angina or acute myocardial infarction (MI) has been analyzed in several studies with controversial results [77–79]. The potential value of small apo(a) isoforms in predicting severe angiographically demonstrable atherosclerosis remains unclear. Elevated serum Lp(a) is an independent predictor of coronary artery disease (CAD) and myocardial infarction [64, 68, 80]. Motta et al. studied the transient increased serum levels of this lipoprotein during acute myocardial infarction (AMI). The positive correlation between mean Lp(a) values on day 1 and 7 and the size of the necrotic area suggested an atherogenic and prothrombotic role of Lp(a). Moreover, elevated Lp(a) values were related to greater tissue damage. This study suggested that periodical determination of Lp(a) values in subjects with coronary disease may be useful in order to predict further acute vascular events [81]. Lp(a) levels should be a marker of restenosis after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [82], saphenous vein bypass graft atherosclerosis [83], and accelerated coronary atherosclerosis of cardiac transplantation [84]. Some studies have shown that Lp(a) is not associated with atherosclerosis, and others have demonstrated that a high serum Lp(a) level is a major risk factor for atherosclerosis and progression of coronary artery disease [85–87]. A high serum Lp(a) level may be a high-risk factor for CCSP (clinical coronary stenosis progression) and restenosis after PCI (percutaneous coronary intervention). An elevated Lp(a) concentration is a significant predictor of long-term adverse outcome in AMI patients treated by primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [88]. Serum Lp(a) levels ≥ 25 mg/dL are noted in 67% of patients with rapid progression of coronary artery disease but in only 33% of patients without progression of coronary artery disease [89]. Tamura et al. studied the association between serum Lp(a) level and angiographically assessed coronary artery disease progression without new myocardial infarction, reporting a significant association [90]. In patients with serum Lp(a) levels ≥ 30 mg/dL, coronary stenosis progression occurred, and revascularizations for target restenotic lesions or new lesions were performed approximately 7 months after the first myocardial infarction; CCSP occurred in a relatively short period after the first AMI in the high-Lp(a) patients [91]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that Lp(a) levels can be considered as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease [92, 93]. The first study of the association between Lp(a) and a range of cardiovascular endpoints including cognitive and disability indices in the elderly was conducted by Gaw et al. The main finding was that Lp(a) level, although influenced by a number of baseline characteristics, is not a significant predictor of cognitive function or levels of disability but is a predictor of combined cardiovascular events over an average 3.2-year followup [94]. Sandholzer et al. reported that in patients with premature coronary heart disease (CHD), alleles at the apo(a) locus determine risk for CHD through their effect on plasma Lp(a) level. This study suggested that Lp(a) can be considered a primary genetic risk factor for CHD [95]. Several epidemiologic studies have assessed the association between Lp(a) and atherosclerotic disease (Table 1). Many population-based prospective studies had reported a controversial association between Lp(a) levels and CHD risk. Few studies, however, have adequately examined important aspects of the association, such as the size of relative risks in clinically relevant subgroups (such as in men and women or at different levels of established risk factors) [56–63, 65–67, 69, 70, 73, 74, 96–98]. A task force for emerging risk factor assessed the relationship between Lp(a) concentration and risk of major vascular and nonvascular outcomes. In this long-term prospective study, Lp(a) plasma levels and subsequent major vascular morbidity and/or cause-specific mortality were recorded. Lp(a) was weakly correlated with several conventional vascular risk factors, and it was highly consistent within individuals over several years. The risk ratio for CHD, adjusted for age and sex only, was 1.16 per 3.5-fold higher usual Lp(a) concentration (i.e., per 1 SD), and it was 1.13 following further adjustment for lipids and other conventional risk factors. The corresponding adjusted risk ratios were 1.10 for ischemic stroke, 1.01 for the aggregate of nonvascular mortality, 1.00 for cancer deaths, and 1.00 for nonvascular deaths other than cancer. The results showed that there are continuous, independent, and modest associations of Lp(a) concentration with risk of CHD and stroke that appear exclusive to vascular outcomes [99]. The Copenhagen City Heart Study (CCHS) found that extreme Lp(a) levels > 95th percentile predict a 3- to 4-fold increase in risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and absolute 10-year risks of 20% and 35% in high-risk women and men [100]. In this study it was observed larger risk estimate for Lp(a) than most previous studies, most likely because the authors focused on extreme levels, measured levels shortly after sampling, corrected for regression dilution bias, and considered MI rather than ischemic heart disease (IHD). For the first time CCHS provided absolute 10-year risk estimates in the general population for MI and IHD as a function of Lp(a) levels stratified for other risk factors, allowing clinicians to use extreme Lp(a) levels in risk assessment of individual patients [101]. In conclusion, most but not all prospective studies on Lp(a) and risk of CHD have found positive associations, and levels of Lp(a) have also been related to severity of disease. Lp(a) levels differ between ethnic groups, and thus results from one study may not be applicable to other ethnic groups. Recent recommendations stated that Lp(a) screening is not warranted for primary prevention and assessment of cardiovascular risk at present, but that Lp(a) measurements can be useful in patients with a strong family history of cardiovascular disease or if risk of cardiovascular disease is considered intermediate on the basis of conventional risk factors [102]. The European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel [103] have suggested screening for elevated Lp(a) in those at intermediate or high CVD/CHD risk, a desirable level < 50 mg/dL as a function of global cardiovascular risk, and use of niacin for Lp(a) and CVD risk reduction.

Table 1.

Lp(a) values in patients that developed atherosclerotic disease.

| Cases | Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Lp(a) (mg/dL) |

n | Lp(a) (mg/dL) |

Years of follow up | Year of the study | |

| Alfthan et al. [56] | ||||||

| Males | 97 | 73 | 148 | 108 | ||

| Females | 97 | 113 | 121 | 91 | 8 | 1994 |

| Assmann et al. [57] | 33 | 90 | 828 | 50 | 8 | 1996 |

| Coleman et al. [58] | 49 | 402 | 192 | 288 | 1–9 | 1992 |

| Cremer et al. [59] | 107 | 180 | 5124 | 90 | 5 | 1994 |

| Jauhiainen et al. [60] | 138 | 131 | 130 | 111 | 6-7 | 1991 |

| Klausen et al. [61] | 74 | 124 | 190 | 94 | 8 or 15 | 1997 |

| Ridker et al. [62] | 296 | 103 | 296 | 102.5 | 5.02 | 1995 |

| Rosengren et al. [63] | 26 | 277.7 | 109 | 172.7 | 6 | 1990 |

| Schaefer et al. [64] | 233 | 237 | 390 | 195 | 7–10 | 1994 |

| Sigurdsson et al. [65] | 104 | 230 | 1228 | 170 | 8.6 | 1992 |

| Wald et al. [66] | 229 | 85.8 | 1145 | 55.6 | 5–12 | 1994 |

| Wild et al. [67] | ||||||

| Males | 90 | 125.1 | 90 | 63.5 | ||

| Females | 44 | 97.3 | 44 | 72.7 | 13 | 1997 |

| Bostom et al. [68] | 305 | >30 | 3103 | 12 | 1994 | |

| Bostom et al. [69] | 129 | 2191 | 15.4 | 1996 | ||

| Cantin et al. [70] | 116 | >30 | 2156 | 5 | 1998 | |

| Cressman et al. [71] | 38.4 | 129 | 16.9 | 4 | 1992 | |

| Stubbs et al. [71] | >30 | 266 197 |

3 | 1998 | ||

| Kronenberg and Utermann [72] | 32.8 | 826 | 8.8 | 5 | 1999 | |

| Bennet et al. [72] | 2047 | 43.8 | 3921 | 40.4 | 12 | 2008 |

| Dahlén et al. [73] | 62 | 250.2 | 124 | 134.7 | 11 | 1998 |

| Cantin et al. [70] | 116 with IHD |

41 | 2040 | 32.7 | 5 | 1998 |

| Nguyen et al [74] | 9936 | 32.8 | 826 | 8.8 | 14 | 1997 |

| Ariyo et al. [72] | 3972 | 4.2 | 7.4 | 2003 | ||

| Hoogeveen et al. [75] | 57 | 12.65 | 46 | 9.15 | 2001 | |

| Dirisamer et al. [76] | 103 | 20 | 103 | 15 | 2002 | |

7. Conclusions

The clinical interest in Lp(a) is largely derived from its role as a cardiovascular risk factor. Although not considered an established risk factor, Lp(a) levels have been associated with cardiovascular disease in numerous studies [72, 104, 105]. Recently Lp(a) serum levels were found to be associated with the severity of aortic atherosclerosis, especially in abdominal aorta, as well as coronary atherosclerosis [106]. Moreover a study by Momiyama et al. [107] demonstrated that elevated Lp(a) has incremental prognostic value in symptomatic patients with coronary artery revascularization [108]. Lp(a) is involved in the development of atherothrombosis and activation of acute inflammation exerting a proatherogenic and hypofibrinolytic effect. Lp(a) plays a critical role in the proinflammatory reaction and can be considered as a common joint among different metabolic systems. Other actions of Lp(a) can be resumed as follows: inhibition of the activation of plasminogen; inhibition of the activation of TGF-β; activation of acute inflammation; induction of the expression of adhesion molecules; elevation of the production of cytokines. Moreover Lp(a) is implicated in the activation of endothelial uptake, oxidative modification, and foam cell formation, suggesting that these processes could play an important role in atherosclerosis. Recent findings suggest that Lp(a)-lowering therapy might be beneficial, at least in some subgroups of patients with high Lp(a) levels. A possible future therapeutic approach could include apheresis in high-risk patients with already maximally reduced LDL cholesterol levels in order to reduce major coronary events [72]. However, further studies are needed to define such subgroups with regard to Lp(a) levels, apo(a) size, and the presence of other risk factors.

Acknowledgments

M. Malaguarnera has been supported by the International Ph. D. program in Neuropharmacology, University of Catania. None of the authors had any relevant personal or financial conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Klingenberg R, Hansson GK. Treating inflammation in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: emerging therapies. European Heart Journal. 2009;30(23):2838–2844. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross R. Atherosclerosis is—an inflammatory disease. American Heart Journal. 1999;138(5):S419–S420. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malaguarnera M, Vacante M, Motta M, Malaguarnera M, Li Volti G, Galvano F. Effect of l-carnitine on the size of low-density lipoprotein particles in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients treated with simvastatin. Metabolism. 2009;58(11):1618–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malaguarnera M, Vacante M, Avitabile T, Malaguarnera M, Cammalleri L, Motta M. L-Carnitine supplementation reduces oxidized LDL cholesterol in patients with diabetes. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89(1):71–76. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motta M, Bennati E, Cardillo E, Ferlito L, Passamonte M, Malaguarnera M. The significance of apolipoprotein-B (Apo-B) in the elderly as a predictive factor of cardio-cerebrovascular complications. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2009;49(1):162–164. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Packard CJ. Apolipoproteins: the new prognostic indicator? European Heart Journal, Supplement. 2003;5:D9–D16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sniderman AD, Furberg CD, Keech A, et al. Apolipoproteins versus lipids as indices of coronary risk and as targets for statin treatment. The Lancet. 2003;361(9359):777–780. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walldius G, Jungner I. Apolipoprotein B and apolipoprotein A-I: risk indicators of coronary heart disease and targets for lipid-modifying therapy. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2004;255(2):188–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Utermann G, Menzel HJ, Kraft HG, Duba HC, Kemmler HG, Seitz C. Lp(a) glycoprotein phenotypes. Inheritance and relation to Lp(a)-lipoprotein concentrations in plasma. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1987;80(2):458–465. doi: 10.1172/JCI113093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fless GM, Rolih CA, Scanu AM. Heterogeneity of human plasma lipoprotein (a). Isolation and characterization of the lipoprotein subspecies and their apoproteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1984;259(18):11470–11478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kostner KM, Maurer G, Huber K, et al. Urinary excretion of apo(a) fragments: role in apo(a) catabolism. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 1996;16(8):905–911. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.8.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mooser V, Marcovina SM, White AL, Hobbs HH. Kringle-containing fragments of apolipoprotein(a) circulate in human plasma and are excreted into the urine. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;98(10):2414–2424. doi: 10.1172/JCI119055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawn RM, Wade DP, Hammer RE, Chiesa G, Verstuyft JG, Rubin EM. Atherogenesis in transgenic mice expressing human apolipoprotein(a) Nature. 1992;360(6405):670–672. doi: 10.1038/360670a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kostner KM, Oberbauer R, Hoffmann U, Stefenelli T, Maurer G, Watschinger B. Urinary excretion of apo(a) in patients after kidney transplantation. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 1997;12(12):2673–2678. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.12.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mooser V, Marcovina SM, Wang J, Hobbs HH. High plasma levels of apo(a) fragments in Caucasians and African-Americans with end-stage renal disease: implications for plasma Lp(a) assay. Clinical Genetics. 1997;52(5):387–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1997.tb04358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oida K, Takai H, Maeda H, et al. Apolipoprotein(a) is present in urine and its excretion is decreased in patients with renal failure. Clinical Chemistry. 1992;38(11):2244–2248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scanu AM. Structural basis for the presumptive atherothrombogenic action of lipoprotein(a). Facts and speculations. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1993;46(10):1675–1680. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90570-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motta M, Giugno I, Ruello P, Pistone G, Di Fazio I, Malaguarnera M. Lipoprotein (a) behaviour in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Minerva Medica. 2001;92(5):301–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galvano F, Malaguarnera M, Vacante M, et al. The physiopathology of lipoprotein (a) Frontiers in Bioscience. 2010;2:866–875. doi: 10.2741/s107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galvano F, Li Volti G, Malaguarnera M, et al. Effects of simvastatin and carnitine versus simvastatin on lipoprotein(a) and apoprotein(a) in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2009;10(12):1875–1882. doi: 10.1517/14656560903081745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen S, Khan S, Tam SP, Koschinsky M, Taylor P, Yacoub M. Expression of adhesion molecules by Lp(a): a potential novel mechanism for its atherogenicity. FASEB Journal. 1998;12(15):1765–1776. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.15.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takami S, Yamashita S, Kihara S, et al. Lipoprotein(a) enhances the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Circulation. 1998;97(8):721–728. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao SP, Xu DY. Oxidized lipoprotein(a) enhanced the expression of P-selectin in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Thrombosis Research. 2000;100(6):501–510. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(00)00363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabas I, Li Y, Brocia RW, Shu Wen Xu, Swenson TL, Williams KJ. Lipoprotein lipase and sphingomyelinase synergistically enhance the association of atherogenic lipoproteins with smooth muscle cells and extracellular matrix. A possible mechanism for low density lipoprotein and lipoprotein(a) retention and macrophage foam cell formation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268(27):20419–20432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loscalzo J. Lipoprotein(a). A unique risk factor for atherothrombotic disease. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10(5):672–679. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.10.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Rijke YB, Jurgens G, Hessels EMAJ, Hermann A, van Berkel TJC. In vivo fate and scavenger receptor recognition of oxidized lipoprotein[a] isoforms in rats. Journal of Lipid Research. 1992;33(9):1315–1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapman MJ, Huby T, Nigon F, Thillet J. Lipoprotein (a): implication in atherothrombosis. Atherosclerosis. 1994;110:S69–S75. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)05385-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haque NS, Zhang X, French DL, et al. CC chemokine I-309 is the principal monocyte chemoattractant induced by apolipoprotein(a) in human vascular endothelial cells. Circulation. 2000;102(7):786–792. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.7.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poon M, Zhang X, Dunsky K, Taubman MB, Harpel PC. Apolipoprotein(a) is a human vascular endothelial cell agonist: studies on the induction in endothelial cells of monocyte chemotactic factor activity. Clinical Genetics. 1997;52(5):308–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1997.tb04348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Rijke YB, Vogelezang CJM, Van Berkel TJC, et al. Susceptibility of low-density lipoproteins to oxidation in coronary bypass patients. The Lancet. 1992;340(8823):858–859. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92742-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naruszewicz M, Selinger E, Dufour R, Davignon J. Probucol protects lipoprotein(a) against oxidative modification. Metabolism. 1992;41(11):1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(92)90013-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huby T, Chapman J, Thillet J. Pathophysiological implication of the structural domains of lipoprotein(a) Atherosclerosis. 1997;133(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morishita R, Ishii J, Kusumi Y, et al. Association of serum oxidized lipoprotein(a) concentration with coronary artery disease: potential role of oxidized lipoprotein(a) in the vasucular wall. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis. 2009;16(4):410–418. doi: 10.5551/jat.no224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun H, Unoki H, Wang X, et al. Lipoprotein(a) enhances advanced atherosclerosis and vascular calcification in WHHL transgenic rabbits expressing human apolipoprotein(a) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(49):47486–47492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Komai N, Morishita R, Yamada S, et al. Mitogenic activity of oxidized lipoprotein (a) on human vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 2002;40(3):310–314. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000029974.50905.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doucet C, Huby T, Ruiz J, Chapman MJ, Thillet J. Non-enzymatic glycation of lipoprotein(a) in vitro and in vivo. Atherosclerosis. 1995;118(1):135–143. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(95)05600-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420(6917):868–874. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uemura S, Matsushita H, Li W, et al. Diabetes mellitus enhances vascular matrix metalloproteinase activity role of oxidative stress. Circulation Research. 2001;88(12):1291–1298. doi: 10.1161/hh1201.092042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eberhardt W, Beeg T, Beck KF, et al. Nitric oxide modulates expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in rat mesangial cells. Kidney International. 2000;57(1):59–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radomski MW, Palmer RMJ, Moncada S. Endogenous nitric oxide inhibits human platelet adhesion to vascular endothelium. The Lancet. 1987;2(8567):1057–1058. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aznar J, Estelles A, Breto M, Espana F. Euglobulin clot lysis induced by tissue type plasminogen activator in subjects with increased levels and different isoforms of lipoprotein (a) Thrombosis Research. 1993;72(5):459–465. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90247-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith EB, Cochran S. Factors influencing the accumulation in fibrous plaques of lipid derived from low density lipoprotein. II. Preferential immobilization of lipoprotein (a) (Lp(a)) Atherosclerosis. 1990;84(2-3):173–181. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(90)90088-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beisiegel U, Niendorf A, Wolf K, Reblin T, Rath M. Lipoprotein(a) in the arterial wall. European Heart Journal. 1990;11:174–183. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/11.suppl_e.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pellegrino M, Furmaniak-Kazmierczak E, LeBlanc JC, et al. The apolipoprotein(a) component of lipoprotein(a) stimulates actin stress fiber formation and loss of cell-cell contact in cultured endothelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(8):6526–6533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohn JN, Finkelstein SM. Abnormalities of vascular compliance in hypertension, aging and heart failure. Journal of Hypertension. 1992;10(6):S61–S64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Riis Hansen P, Kharazmi A, Jauhiainen M, Ehnholm C. Induction of oxygen free radical generation in human monocytes by lipoprotein(a) European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1994;24(7):497–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1994.tb02381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fan J, Sun H, Unoki H, Shiomi M, Watanabe T. Enhanced atherosclerosis in Lp(a) WHHL transgenic rabbits. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001;947:362–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ichikawa T, Unoki H, Sun H, et al. Lipoprotein(a) promotes smooth muscle cell proliferation and dedifferentiation in atherosclerotic lesions of human apo(a) transgenic rabbits. American Journal of Pathology. 2002;160(1):227–236. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64366-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fan J, Watanabe T. Inflammatory reactions in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis. 2003;10(2):63–71. doi: 10.5551/jat.10.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kojima S, Harpel PC, Rifkin DB. Lipoprotein (a) inhibits the generation of transforming growth factor β: an endogenous inhibitor of smooth muscle cell migration. Journal of Cell Biology. 1991;113(6):1439–1445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.6.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lawn RM, Pearle AD, Kunz LL, et al. Feedback mechanism of focal vascular lesion formation in transgenic apolipoprotein(a) mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(49):31367–31371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Etingin OR, Hajjar DP, Hajjar KA, Harpel PC, Nachman RL. Lipoprotein (a) regulates plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in endothelial cells: a potential mechanism in thrombogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266(4):2459–2465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thillet J, Doucet C, Chapman J, Herbeth B, Cohen D, Faure-Delanef L. Elevated lipoprotein(a) levels and small apo(a) isoforms are compatible with longevity evidence from a large population of French centenarians. Atherosclerosis. 1998;136(2):389–394. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00217-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Malaguarnera M, Giugno I, Ruello P, et al. Lipid profile variations in a group of healthy elderly and centenarians. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 1998;2(2):75–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malaguarnera M, Ruello P, Rizzo M, et al. Lipoprotein (a) levels in centenarians. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 1996;22(1):385–388. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(96)86967-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alfthan G, Pekkanen J, Jauhiainen M, et al. Relation of serum homocysteine and lipoprotein(a) concentrations to atherosclerotic disease in a prospective Finnish population based study. Atherosclerosis. 1994;106(1):9–19. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Assmann G, Schulte H, Von Eckardstein A. Hypertriglyceridemia and elevated lipoprotein(a) are risk factors for major coronary events in middle-aged men. American Journal of Cardiology. 1996;77(14):1179–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coleman MP, Key TJA, Wang DY, et al. A prospective study of obesity, lipids, apolipoproteins and ischaemic heart disease in women. Atherosclerosis. 1992;92(2-3):177–185. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(92)90276-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cremer P, Nagel D, Mann H, et al. Ten-year follow-up results from the Goettingen Risk, Incidence and Prevalence Study (GRIPS). I. Risk factors for myocardial infarction in a cohort of 5790 men. Atherosclerosis. 1997;129(2):221–230. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(96)06030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jauhiainen M, Koskinen P, Ehnholm C, et al. Lipoprotein (a) and coronary heart disease risk: a nested case-control study of the Helsinki Heart Study participants. Atherosclerosis. 1991;89(1):59–67. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(91)90007-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klausen IC, Sjøl A, Hansen PS, et al. Apolipoprotein(a) isoforms and coronary heart disease in men A nested case-control study. Atherosclerosis. 1997;132(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Stampfer MJ. A prospective study of lipoprotein(a) and the risk of myocardial infarction. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;270(18):2195–2199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L, Eriksson E, Risberg B, Wedel H. Lipoprotein (a) and coronary heart disease: a prospective case-control study in a general population sample of middle aged men. British Medical Journal. 1990;301(6763):1248–1251. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6763.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schaefer EJ, Lamon-Fava S, Jenner JL, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of coronary heart disease in men: the lipid research clinics coronary primary prevention trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271(13):999–1003. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510370051031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sigurdsson G, Baldursdottir A, Sigvaldason H, Agnarsson U, Thorgeirsson G, Sigfusson N. Predictive value of apolipoproteins in a prospective survey of coronary artery disease in men. American Journal of Cardiology. 1992;69(16):1251–1254. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)91215-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wald NJ, Law M, Watt HC, et al. Apolipoproteins and ischaemic heart disease: implications for screening. The Lancet. 1994;343(8889):75–79. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90814-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wild SH, Fortmann SP, Marcovina SM. A prospective case-control study of lipoprotein(a) levels and apo(a) size and risk of coronary heart disease in Stanford Five-City project participants. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 1997;17(5):239–245. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bostom AG, Gagnon DR, Cupples LA, et al. A prospective investigation of elevated lipoprotein (a) detected by electrophoresis and cardiovascular disease in women: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1994;90(4):1688–1695. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.4.1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bostom AG, Cupples LA, Jenner JL, et al. Elevated plasma lipoprotein(a) and coronary heart disease in men aged 55 years and younger: a prospective study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276(7):544–548. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03540070040028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cantin B, Gagnon F, Moorjani S, et al. Is lipoprotein(a) an independent risk factor for ischemic heart disease in men? The Quebec cardiovascular study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1998;31(3):519–525. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00528-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cressman MD, Heyka RJ, Paganini EP, O'Neil J, Skibinski CI, Hoff HF. Lipoprotein(a) is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease in hemodialysis patients. Circulation. 1992;86(2):475–482. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kronenberg F, Kronenberg MF, Kiechl S, et al. Role of lipoprotein(a) and apolipoprotein(a) phenotype in atherogenesis: prospective results from the Bruneck study. Circulation. 1999;100(11):1154–1160. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.11.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dahlén GH, Weinehall L, Stenlund H, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and cholesterol levels act synergistically and apolipoprotein A-I is protective for the incidence of primary acute myocardial infarction in middle-aged males. An incident case-control study from Sweden. Journal of Internal Medicine. 1998;244(5):425–430. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nguyen TT, Ellefson RD, Hodge DO, Bailey KR, Kottke TE, Abu-Lebdeh HS. Predictive value of electrophoretically detected lipoprotein(a) for coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular disease in a community-based cohort of 9936 men and women. Circulation. 1997;96(5):1390–1397. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hoogeveen RC, Gambhir JK, Gambhir DS, et al. Evaluation of Lp[a] and other independent risk factors for CHD in Asian Indians and their USA counterparts. Journal of Lipid Research. 2001;42(4):631–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dirisamer A, Widhalm K. Lipoprotein(a) as a potent risk indicator for early cardiovascular disease. Acta Paediatrica. 2002;91(12):1313–1317. doi: 10.1080/08035250216114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wilson SH, Celermajer DS, Nakagomi A, Wyndham RN, Janu MR, Freedman SB. Vascular risk factors correlate to the extent as well as the severity of coronary atherosclerosis. Coronary Artery Disease. 1999;10(7):449–453. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199910000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schwartzman RA, Cox ID, Poloniecki J, Crook R, Seymour CA, Kaski JC. Elevated plasma lipoprotein(a) is associated with coronary artery disease in patients with chronic stable angina pectoris. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1998;31(6):1260–1266. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Imhof A, Rothenbacher D, Khuseyinova N, et al. Plasma lipoprotein Lp(a), markers of haemostasis and inflammation, and risk and severity of coronary heart disease. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. 2003;10(5):362–370. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000087080.83314.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rader DJ, Hoeg JM, Brewer HB. Quantitation of plasma apolipoproteins in the primary and secondary prevention of coronary artery disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1994;120(12):1012–1025. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-12-199406150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Motta M, Giugno I, Bosco S, et al. Serum lipoprotein(a) changes in acute myocardial infarction. Panminerva Medica. 2001;43(2):77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Desmarais RL, Sarembock IJ, Ayers CR, Vernon SM, Powers ER, Gimple LW. Elevated serum lipoprotein(a) is a risk factor for clinical recurrence after coronary balloon angioplasty. Circulation. 1995;91(5):1403–1409. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.5.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hoff HF, Beck GJ, Skibinski CI, et al. Serum Lp(a) level as a predictor of vein graft stenosis after coronary artery bypass surgery in patients. Circulation. 1988;77(6):1238–1244. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.6.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barbir M, Kushwaha S, Hunt B, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and accelerated coronary artery disease in cardiac transplant recipients. The Lancet. 1992;340(8834-8835):1500–1502. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92756-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maher VMG, Brown BG, Marcovina SM, Hillger LA, Zhao XQ, Albers JJ. Effects of lowering elevated LDL cholesterol on the cardiovascular risk of lipoprotein(a) Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274(22):1771–1774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Patsch W, Gotto AM. Apolipoproteins: pathophysiology and clinical implications. Methods in Enzymology. 1996;263:3–32. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)63003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stein JH, Rosenson RS. Lipoprotein Lp(a) excess and coronary heart disease. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157(11):1170–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Igarashi Y, Aizawa Y, Satoh T, Konno T, Ojima K, Aizawa Y. Predictors of adverse long-term outcome in acute myocardial infarction patients undergoing primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty—with special reference to the admission concentration of lipoprotein (a) Circulation Journal. 2003;67(7):605–611. doi: 10.1253/circj.67.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Terres W, Tatsis E, Pfalzer B, Beil FU, Beisiegel U, Hamm CW. Rapid angiographic progression of coronary artery disease in patients with elevated lipoprotein(a) Circulation. 1995;91(4):948–950. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tamura A, Watanabe T, Mikuriya Y, Nasu M. Serum lipoprotein(a) concentrations are related to coronary disease progression without new myocardial infarction. British Heart Journal. 1995;74(4):365–369. doi: 10.1136/hrt.74.4.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Morita Y, Himeno H, Yakuwa H, Usui T. Serum lipoprotein(a) level and clinical coronary stenosis progression in patients with myocardial infarction: re-revascularization rate is high in patients with high-Lp(a) Circulation Journal. 2006;70(2):156–162. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Craig WY, Neveux LM, Palomaki GE, Cleveland MM, Haddow JE. Lipoprotein(a) as a risk factor for ischemic heart disease: metaanalysis of prospective studies. Clinical Chemistry. 1998;44(11):2301–2306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Danesh J, Collins R, Peto R. Lipoprotein(a) and coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. Circulation. 2000;102(10):1082–1085. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.10.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gaw A, Murray HM, Brown EA. Plasma lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] concentrations and cardiovascular events in the elderly: evidence from the Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER) Atherosclerosis. 2005;180(2):381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sandholzer C, Saha N, Kark JD, et al. Apo(a) isoforms predict risk for coronary heart disease: a study in six populations. Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis. 1992;12(10):1214–1226. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.10.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Edelberg JM, Reilly CF, Pizzo SV. The inhibition of tissue type plasminogen activator by plasminogen activator inhibitor-1: the effects of fibrinogen, heparin, vitronectin, and lipoprotein(a) Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266(12):7488–7493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Grainger DJ, Kirschenlohr HL, Metcalfe JC, Weissberg PL, Wade DP, Lawn RM. Proliferation of human smooth muscle cells promoted by lipoprotein(a) Science. 1993;260(5114):1655–1658. doi: 10.1126/science.8503012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dahlén G. Lipoprotein (a) as a risk factor for atherosclerotic diseases. Arctic Medical Research. 1998;47:458–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Erqou S, Kaptoge S, et al. Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302(4):412–423. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kamstrup PR, Benn M, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Extreme lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of myocardial infarction in the general population: the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(2):176–184. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.715698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.American Association for Clinical Chemistry. Emerging Biomarkers for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke. 2009, http://www.aacc.org/members/nacb/LMPG/OnlineGuide/PublishedGuidelines/risk/Documents/EmergingCV_RiskFactors09.pdf.

- 102.Milionis HJ, Winder AF, Mikhailidis DP. Lipoprotein (a) and stroke. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2000;53(7):487–496. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.7.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Ray K, et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: current status. European Heart Journal. 2010;31(23):2844–2853. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Riches K, Porter KE. Lipoprotein(a): cellular effects and molecular mechanisms. Cholesterol. 2012;2012:10 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/923289.923289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dubé, B J, Boffa MB, Hegele RA, Koschinsky ML. Lipoprotein(a): more interesting than ever after 50 years. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2012;23:133–140. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32835111d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tsimikas S, Hall JL. Lipoprotein(a) as a potential causal genetic risk factor of cardiovascular disease: a rationale for increased efforts to understand its pathophysiology and develop targeted therapies. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;60:716–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Momiyama Y, Ohmori R, Fayad ZA, et al. Associations between serum lipoprotein(a) levels and the severity of coronary and aortic atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2012;222(1):241–244. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Momiyama Y, Ohmori R, Fayad ZA, et al. Associations between serum lipoprotein(a) levels and the severity of coronary and aortic atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2012;222(1):241–244. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]