Abstract

Bbil-TX, a PLA2, was purified from Bothriopsis bilineata snake venom after only one chromatographic step using RP-HPLC on μ-Bondapak C-18 column. A molecular mass of 14243.8 Da was confirmed by Q-Tof Ultima API ESI/MS (TOF MS mode) mass spectrometry. The partial protein sequence obtained was then submitted to BLASTp, with the search restricted to PLA2 from snakes and shows high identity values when compared to other PLA2s. PLA2 activity was presented in the presence of a synthetic substrate and showed a minimum sigmoidal behavior, reaching its maximal activity at pH 8.0 and 25–37°C. Maximum PLA2 activity required Ca2+ and in the presence of Cd2+, Zn2+, Mn2+, and Mg2+ it was reduced in the presence or absence of Ca2+. Crotapotin from Crotalus durissus cascavella rattlesnake venom and antihemorrhagic factor DA2-II from Didelphis albiventris opossum sera under optimal conditions significantly inhibit the enzymatic activity. Bbil-TX induces myonecrosis in mice. The fraction does not show a significant cytotoxic activity in myotubes and myoblasts (C2C12). The inflammatory events induced in the serum of mice by Bbil-TX isolated from Bothriopsis bilineata snake venom were investigated. An increase in vascular permeability and in the levels of TNF-a, IL-6, and IL-1 was was induced. Since Bbil-TX exerts a stronger proinflammatory effect, the phospholipid hydrolysis may be relevant for these phenomena.

1. Introduction

Viperidae snakes are represented in South America by Crotalus, Bothrops, Bothriopsis and Lachesis. Bothriopsis bilineata is the endemic and rare bothropic snake species [1].

The envenomation is characterized by a generalized inflammatory state. The normal reaction to envenomation involves a series of complex immunologic cascades that ensures a prompt protective response to venom in humans [2]. Although activation of the immune system during envenomation is generally protective, septic shock develops in a number of patients as a consequence of excessive or poorly regulated immune response to the injured organism [3]. This imbalanced reaction may harm the host through a maladaptitive release of endogenous mediators that include cytokines and nitric oxide.

PLA2s are abundant in snake venoms and have been widely employed as pharmacological tools to investigate their role in diverse pathophysiological processes. Viperid and crotalid venoms contain PLA2s with the ability to cause rapid necrosis of skeletal muscle fibers, thus being referred to as myotoxic PLA2s [4]. Local inflammation is a prominent characteristic of snakebite envenomations by viperid and crotalid species [5].

Furthermore, PLA2 myotoxins are relevant tools for the study of key general inflammatory mechanisms. High levels of secretory PLA2 (sPLA2) are detected in a number of inflammatory disorders in humans, such as bronchial asthma [6], allergic rhinitis [7], septic shock [8], acute pancreatitis [9], extensive burning [10], and autoimmune diseases [11]. In addition, increased expression and release of sPLA2 have been found in rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, and atherosclerosis [12, 13]. Mechanisms involved in the proinflammatory action of sPLA2 are being actively investigated, and most of this knowledge is based on studies using purified venom PLA2s.

This paper describes the isolation and biochemical and pharmacological characterization of new PLA2s from Bothriopsis bilineata venom, Bbil-TX, and also the study of its various toxic activities, including myotoxicity, cytotoxicity, and inflammation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Venom and Reagents

Bothriopsis bilineata venom was donated by Dr. Corina Vera Gonzáles. All chemicals and reagents used in this work were of analytical or sequencing grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Reversed-Phase HPLC (RP-HPLC)

Five milligrams of the whole venom from Bothriopsis bilineata was dissolved in 200 μL ammonium bicarbonate 0.2 M pH 8.0. The resulting solution was clarified by centrifugation and the supernatant was applied to a μ-Bondapak C18 column (0.78 × 30 cm; Waters 991—PDA system). Fractions were eluted using a linear gradient (0–100%, v/v) of acetonitrile (solvent B) at a constant flow rate of 1.0 mL/min over 40 min. The elution profile was monitored at 280 nm, and the collected fractions were lyophilized and conserved at −20°C.

2.3. PLA2 Activity

PLA2 activity was measured using the assay described by Holzer and Mackessy, [14] modified for 96-well plates. The standard assay mixture contained 200 μL of buffer (10 mM tris-HCl, 10 mM CaCl2 and 100 mM NaCl, pH 8.0), 20 μL of substrate (4-nitro-3-octanoyloxy-benzoic acid), 20 μL of water, and 20 μL of Bbil-TX in a final volume of 260 μL. After adding Bbil-TX (20 μg), the mixture was incubated for up to 40 min at 37°C, with the reading of absorbance at intervals of 10 min. The enzyme activity, expressed as the initial velocity of the reaction (V o), was calculated based on the increase of absorbance after 20 min. The optimum pH and temperature of the PLA2 were determined by incubating the enzyme in four buffers of different pH values (4–10) and at different temperatures, respectively. The effect of substrate concentration (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, and 30 mM) on enzyme activity was determined by measuring the increase of absorbance after 20 min. The inhibition of PLA2 activity by crotapotins from Crotalus durissus cascavella and DAII-2 from Didephis albiventris serum was determined by preincubating the protein (Bbil-TX) and each inhibitor for 30 min at 37°C prior to assaying the residual enzyme activity under optimal conditions. All assays were done in triplicate and the absorbances at 425 nm were measured with a VersaMax 190 multiwell plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

2.4. Electrophoresis

Tricine SDS-PAGE in a discontinuous gel and buffer system was used to estimate the molecular mass of the proteins, under reducing and nonreducing conditions [15].

2.5. Amino Acid Analysis

Amino acid analysis was performed on a Pico-Tag Analyzer (Waters Systems) as described by [16]. The purified Bbil-TX sample (30 μg) was hydrolyzed at 105°C for 24 h in 6 M HCl (Pierce sequencing grade) containing 1% phenol (w/v). The hydrolyzates were reacted with 20 μL of derivatization solution (ethanol : triethylamine : water : phenylisothiocyanate, 7 : 1 : 1 : 1, v/v) for 1 h at room temperature, after which the PTC-amino acids were identified and quantified by HPLC, by comparing their retention times and peak areas with those from a standard amino acid mixture.

2.6. Determination of the Molecular Mass of the Purified Protein by Mass Spectrometry

An aliquot (4.5 μL) of the protein was inject by C18 (100 μm × 100 mm) RP-UPLC (nanoAcquity UPLC, Waters) coupled with nanoelectrospray tandem mass spectrometry on a Q-T of Ultima API mass spectrometer (MicroMass/Waters) at a flow rate of 600 nl/min. The gradient was 0–50% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid over 45 min. The instrument was operated in MS continuum mode and the data acquisition was from m/z 100–3,000 at a scan rate of 1 s and an interscan delay of 0.1 s. The spectra were accumulated over about 300 scans and the multiple charged data produced by the mass spectrometer on the m/z scale were converted to the mass (molecular weight) scale using maximum-entropy-based software (1) supplied with Masslynx 4.1 software package. The processing parameters were: output mass range 6,000–20,000 Da at a “resolution” of 0.1 Da/channel; the simulated isotope pattern model was used with the spectrum blur width parameter set to 0.2 Da and the minimum intensity ratios between successive peaks were 20% (left and right). The deconvoluted spectrum was then smoothed (2 × 3 channels, Savitzky Golay smooth) and the mass centroid values obtained using 80% of the peak top and a minimum peak width at half height of 4 channels.

2.7. Analysis of Tryptic Digests

The protein was reduced (DTT 5 mM for 25 min to 56°C) and alkylated (Iodoacetamide 14 mM for 30 min) prior to the addition of trypsin (Promega's sequencing grade modified). After trypsin addition (20 ng/μL in ambic 0.05 M), the sample was incubated for 16 hr at 37°C. To stop the reaction, formic acid 0.4% was added and the sample centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 10 min. The pellet was discarded and the supernatant dried in a speed vac. The resulting peptides were separated by C18 (100 μm × 100 mm) RP-UPLC (nanoAcquity UPLC, Waters) coupled with nanoelectrospray tandem mass spectrometry on a Q-Tof Ultima API mass spectrometer (MicroMass/Waters) at a flow rate of 600 nl/min. Before performing a tandem mass spectrum, an ESI/MS mass spectrum (TOF MS mode) was acquired for each HPLC fraction over the mass range of 100–2000 m/z, in order to select the ion of interest; subsequently, these ions were fragmented in the collision cell (TOF MS/MS mode).

Raw data files from LC-MS/MS runs were processed using Masslynx 4.1 software package (Waters) and analyzed using the MASCOT search engine version 2.3 (Matrix Science Ltd.) against the snakes database, using the following parameters: peptide mass tolerance of ±0.1 Da, fragment mass tolerance of ±0.1 Da, and oxidation as variable modifications in methionine and trypsin as enzyme.

2.8. Myotoxic Activity

Groups of four Swiss mice (18–20 g) received an intramuscular (i.m.) or an intravenous (i.v.) injection of variable amounts of the Bbil-TX. Samples (50 μL) containing 0.1, 1, and 5 μg of the PLA2 Bbil-TX were injected in the right gastrocnemius. A control group received 50 μL of PBS. At different intervals, blood was collected from the tail into heparinized capillary tubes after 2, 4, 6, 9, 12 and 24 hours, and the plasma creatine kinase (CK; EC 2.7.3.2) activity was determined by a kinetic assay Ck-Nac, (creatine kinase, Beacon, Diagnostics, Germany). To the reaction mixture 10 μL of the plasma obtained by centrifugation from mice blood was added. The solution is incubated for 2 minutes and reads at 430 nm. The results were expressed as U/L according to the manufacturer.

2.9. Cytotoxicity Assays

Cytotoxic activity was assayed on murine skeletal muscle C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes (ATCC CRL-1772). Variable amounts of Bbil-TX were diluted in assay medium (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium supplemented with 1% fetal-calf serum) and added to cells in 96-well plates, in 150 μL. Controls for 0 and 100% toxicity consisted of assay medium, and 0.1% Triton X-100, respectively. After 3 h at 37°C, a supernatant aliquot was collected for determination of lactic dehydrogenase (LDH; EC 1.1.1.27) activity released from damaged cells, using a kinetic assay (Wiener LDH-P UV). Experiments were carried out in triplicate.

2.10. Edema-Forming Activity

The ability of Bbil-TX to induce edema was studied in groups of five Swiss mice (18–20 g). Fifty microliters of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.12 M NaCl, 0.04 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.2) with Bbil-TX (0.1; 1 and 5 μg/paw) were injected in the subplantar region of the right footpad. The control group received an equal volume of PBS alone. The paw swelling was measured with an Electronic Caliper Series 1101 (INSIZE LTDA, SP, Brazil) at 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 9, and 24 h after administration. Edema was expressed as the percentage increase in the size of the treated group to that of the control group at each time equal to 24 hrs.

2.11. Cytokines

The levels of cytokines IL-6 and IL-1 in the serum from BALB/c mice were assayed by a two-site sandwich enzyme-like immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described by [17]. In brief, ELISA plates were coated with 100 μL (1 μg/mL) of the monoclonal antibodies anti-IL-6 and anti-IL-1 placed in 0.1 M sodium carbonate buffer (pH 8.2), and incubated for 6 hours at room temperature. The wells were then washed with 0.1% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS/Tween 20) and blocked with 100 μL of 10% fetal-calf serum (FCS) in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature. After washing, duplicate sera samples of 50 μL were added to each well. After 18 hours of incubation at 4°C, the wells were washed and incubated with 100 μL (2 μg/mL) of the biotinylated monoclonal antibody anti-IL-6 and anti-IL-1 as a second antibody for 45 minutes at room temperature. After a final wash, the reaction was developed by the addition of orthophenyldiamine (OPD) to each well. Optical densities were measured at 405 nm in a microplate reader. The cytokine content of each sample was read from a standard curve established with the appropriate recombinant cytokines (expressed in picograms per millilitre). The minimum levels of each cytokine detectable in the conditions of the assays were 10 pg/mL for IL-6 and IL-1.

To measure the cytotoxicity of TNF-α present in the serum from BALB/c mice, a standard assay with L-929 cells, a fibroblast continuous cell line, was used as described previously by [18]. The percentage cytotoxicity was calculated as follows: (Acontrol − Asample/Acontrol) × 100. Titres were calculated as the reciprocal of the dilution of the sample in which 50% of the cells in the monolayer were lysed. TNF-α activity is expressed as units/mL, estimated from the ratio of a 50% cytotoxic dose of the test to that of the standard mouse recombinant TNF-α.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Results are reported as means ± SEM. The significance of differences between the means was assessed by ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test when various experimental groups were compared with the control group. A value of P < 0.05 indicated significance.

3. Results

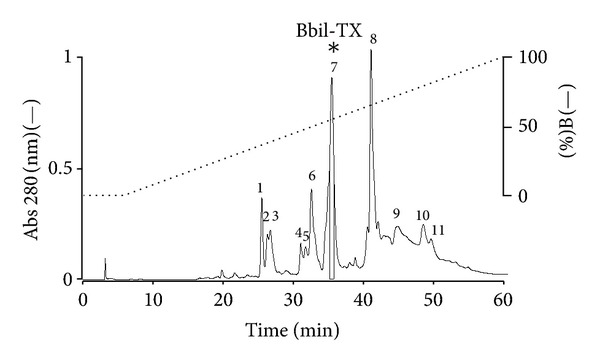

Fractionation of Bothriopsis bilineata venom by RP-HPLC on a μ-Bondapak C18 column resulted in eleven peaks (1–11) (Figure 1). The 11 peaks were screened for myotoxic and PLA2 activities. Peak 7 caused local myotoxicity at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 5 μg/mL in mouse gastrocnemius muscle. In addition, peak 7, named Bbil-TX-I (Bothriopsis bilineata toxin) showed high PLA2 activity and was selected for biochemical and pharmacological characterization. The purity of this peak was confirmed by rechromatography on an analytical RP-HPLC μ-Bondapack C18 column, showing the presence of only one peak and by Tricine SDS-PAGE, which revealed the presence of one electrophoretic band with Mr around 15 kDa, in the absence and presence of DTT (1 M) (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Elution profile of Bothriopsis bilineata venom by RP-HPLC on a μ-Bondapack C18 column. Fraction 7 (Bbil-TX) contained PLA2 activity.

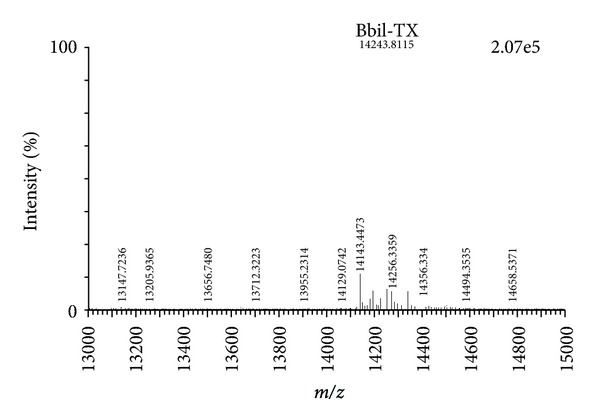

Q-Tof Ultima API ESI/MS (TOF MS mode) mass spectrometry analysis confirmed the homogeneity of the peak Bbil-TX and determined the exact molecular mass of 14243.8 Da (Figure 2). This value of molecular mass was used in calculating the molar concentrations of toxin used in the experiments described below.

Figure 2.

Mass determinations of Bbil-TX by mass spectrometry, using a Q-Tof Ultima API ESI/MS (TOF MS mode).

The alkylated and reduced protein was digested with trypsin and the resulting tryptic peptides (10) were fractionated by RP-UPLC (nanoAcquity UPLC, Waters) (data not shown). Before performing a tandem mass spectrum, an ESI/MS mass spectrum (TOF MS mode) was acquired for each HPLC fraction over the mass range of 100–2000 m/z, in order to select the ion of interest; subsequently, these ions were fragmented in the collision cell (TOF MS/MS mode). The data files obtained from LC-MS/MS runs were processed using the Masslynx 4.1 software package (Waters) and analyzed using the MASCOT search engine version 2.3 (http://www.matrixscience.com/). Table 1 shows the deduced sequence and measured masses of alkylated peptides obtained for Bbil-TX PLA2. Isoleucine and leucine residues were not discriminated in any of the sequences reported since they were indistinguishable in low energy CID spectra. Because of the external calibration applied to all spectra, it was also not possible to resolve the 0.041 Da difference between glutamine and lysine residues, except for the lysine that was deduced based on the cleavage and missed cleavage of the enzyme.

Table 1.

Sequence obtained by MS/MS based on the alkylated tryptic peptides derived. The peptides were separated and sequenced by mass spectrometry.

| Residue number | Mass (Da) expected | Amino acid sequence | Mass (Da) calculated |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–7 | 898.5293 | HLLQFNK | 898.5025 |

| 16–33 | 2157.9352 | NAIPFYAFYGCYCGWGGR | 2157.9189 |

| 43–53 | 1504.5356 | CCFVHDCCYGK | 1504.5356 |

| 61–69 | 1183.6216 | WDIYPYSLK | 1183.5913 |

| 70–77 | 884.4277 | SGYITCGK | 884.4062 |

| 78–90 | 871.8404 | GTWCEEQICECDR | 1741.6494 |

| 91–98 | 973.5307 | VAAECLRR | 973.5127 |

| 98–104 | 853.4780 | RSLSTYK | 853.4657 |

| 105–114 | 1297.5059 | YGYMFYPDSR | 1297.5437 |

| 115–122 | 965.3514 | CRGPSETC | 965.3695 |

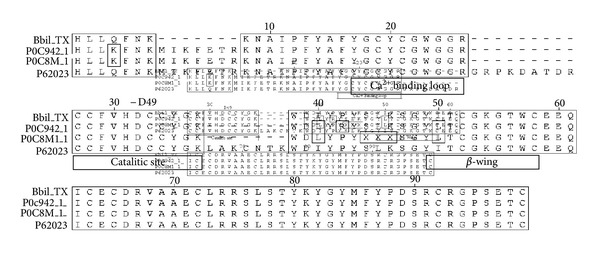

The ten peptides obtained in Q-Tof Ultima API ESI/MS (TOF MS mode) mass spectrometry of the Bbil-TX PLA2 were submitted to the NCBI database, using the protein search program BLASTp with the search being restricted to the sequenced proteins from the basic protein with phospholipase A2 activity family. Based on the positional matches of the de novo sequenced peptides with other homologous proteins, it was possible to deduce the original positions of these peptides in the native protein (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of the new PLA2 Bbil-TX with PLA2 presents in venom of Lachesis muta muta (accession number P0C8 M_1 and P0C942_1) [19] and Crotalus scutulatus scutulatus (Mojave rattlesnake) (accession number P62023). Nondetermined amino acid residues are indicated by (X); boxed amino acid residues are identical. The highlighted amino acid residues belong to PLA2 conserved domain Ca2+-binding loop, the catalytic site, and the region β-wing.

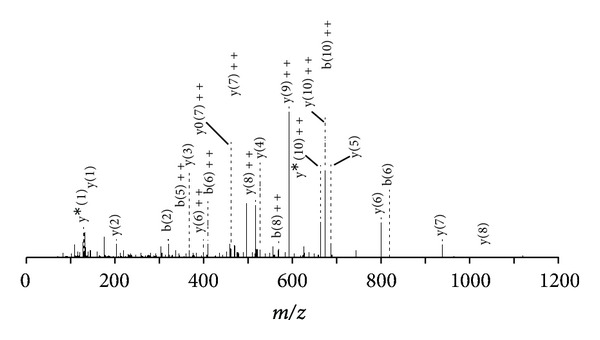

The results of the primary structures show that Bbil-TX PLA2 is composed of 122 amino acid residues and shares the conserved sequence domains common to PLA2 group, including the 14 cysteines, the calcium-binding site located on (Y)27, (G)28, (C)31, and (G)32, and the catalytic network commonly formed by (H)48, (D)49, (Y)52, and (D)90. A comparative analysis of the sequence of Bbil-TX PLA2 with other neurotoxins “ex vivo” and myotoxic PLA2s belonging to Viperidae family, LmTX-I and LmTX-II (Lachesis muta muta) [19] and Crotalus scutulatus scutulatus (Mojave rattlesnake) (accession number P62023), showed similarity of 81.1–91.0%. (SwissProt database http://br.expasy.org/). The tandem mass spectra shown in Figure 3, relative to the peptide eluted in fraction 3 having the sequence C C F V H D C C Y G K, allows to classify both enzymes as PLA2.

Figure 3.

MS/MS spectrum of the doubly charged tryptic ion of m/z 1504.5356. Ion of the major sequence-specific y-ion series and of a minor series of the complementing b-ions CCFVHDCCYGK, from which the sequence of Bbil-TX tag was deduced.

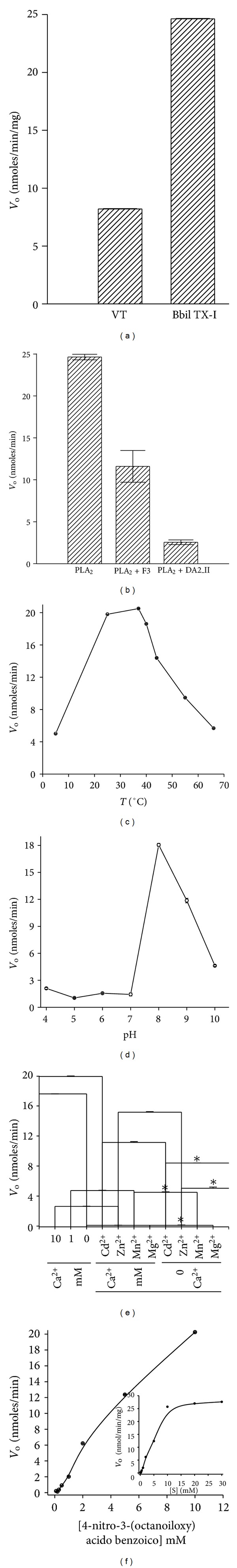

Amino acid analysis revealed the following composition of Bbil-TX PLA2: D/11, T/7, S/2, E/12, P/9, G/10, A/7, C/14, V/4, M/2, I/3, L/7, Y/9, F/4, K/12, H/1, and R/6. The PLA2 activity was examined in the Bothopsis bilineata venom and in BbilTX-I using the synthetic substrate 4-nitro-3(octanoyloxy) benzoic acid [14, 19]. The PLA2 activity was higher in Bbil-TX (24.75 ± 2.68 nmols/min/mg) when compared with the whole venom (8.15 ± 1.24 nmols/min/mg) (Figure 5(a)). Under the conditions used, Bbil-TX showed a discrete sigmoidal behavior (Figure 5(f)), mainly at low substrate concentrations. Maximum enzyme activity occurred at 35–40°C (Figure 5(c)) and the pH optimum was 8.0 (Figure 5(d)). PLA2s require Ca+2 for full activity, with only 1 mM of Ca+2 needed for Bbil-TX to present phospholipase activity. The addition of Mg2+, Cd2+, and Mn2+ (10 mM) in the presence of low Ca2+ concentration (1 mM) decreases the enzyme activity. The substitution of Ca2+ by Mg2+, Cd2+, and Mn2+ also reduced the activity to levels similar to those in the absence of Ca2+ (Figure 5(e)).

Figure 5.

(a) PLA2 activity of Bothriopsis bilineata venom and peak 7 (Bbil-TX); (b) the inhibitory effect of the antihemorrhagic factor DAII-2 and the crotapotin F3 on PLA2 activity Bbil-TX; (c) effect of temperature on the PLA2 activity of Bbil-TX; (d) effect of pH on Bbil-TX activity; (e) influence of ions (10 mM each) on PLA2 activity in the absence or presence of 1 mM Ca2+; (f) effect of substrate concentration on the kinetics of BbilTX (PLA2) activity. The inset shows the curve shape at low substrate concentrations. The results of all experiments are the mean ± SE, of three determinations (P < 0.05).

The crotapotins are pharmacologically inactive and nonenzymatic acid protein, binds specifically of the PLA2 inhibited the activity. An isoform of Crotalus durissus cascavella F3 and antihaemorragic factor DA2-II from Didelphis albiventris, significantly inhibit the Bbil-TX PLA2 activity (Figure 5(b)).

The local myotoxic effect (i.m.) in vivo was observed with PLA2 Bbil-TX studied. It was observed that the PLA2 induced a conspicuous effect evidenced by the rapid elevation of plasma CK activity through a time course, reaching its maximum effect 2 h after injection and returning to normal levels after 24 h (Figure 6(a)). Our results showed that the PLA2 Bbil-TX did not show systemic myotoxic effect (i.v.) (Figure 6(b)).

Figure 6.

(a, b) Time course of the increments in plasma CK activity after intramuscular (i.m.) or intravenous (i.v.) injection of 0.1, 1, and 5 μg Bothriopsis bilineata Bbil-TX; (c) in vitro cytotoxic activity of Bbil-TX on murine C2C12 skeletal-muscle myoblasts and myotubes. Cell lysis was estimated by the release of lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) to supernatants, after 3 h of exposure to the toxins. Each point represents mean ± SD of triplicate cell cultures.

In a concentration of 5, 10, 20, and 40 μg/well (150 μL), the PLA2 Bbil-TX showed low cytotoxicity in skeletal muscle myoblasts and myotubes (25.49 ± 2.3% and 29.05 ± 3.45%, resp.) in a concentration of 40 mg/well (150 μL) (Figure 6(c)).

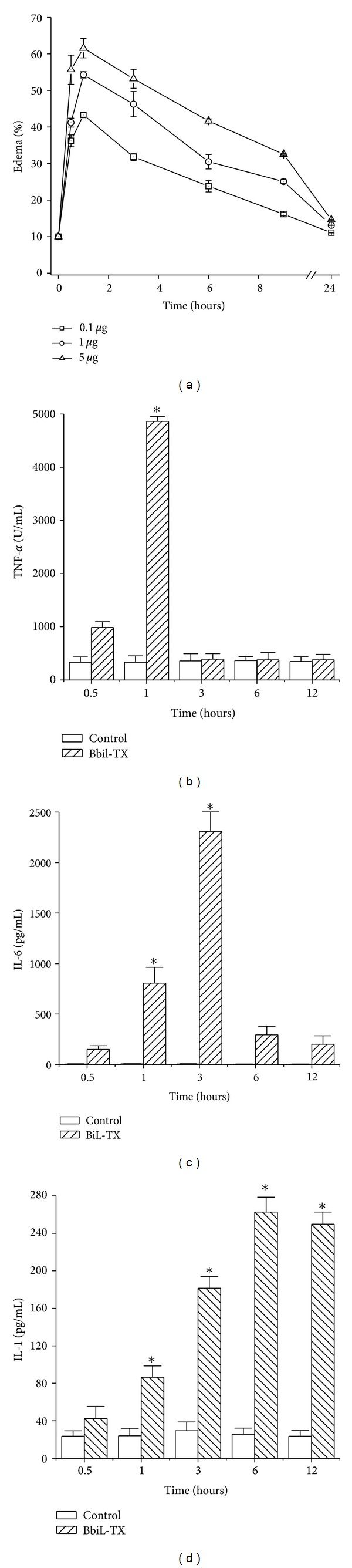

Compared to PBS-injected animals, those which received subplantar injections of the Bbil-TX (0.1, 1, and 5 μg/paw) presented marked paw edema (Figure 7(a)). Maximal activity was attained 1 h to the Bbil-TX after injection and receded to normal levels after 24 h. The level of edema induction by 5 μg of PLA2 1 hour after administration was 61.57%, showing a dose-dependent activity. To further analyze the mechanisms of the inflammatory events induced by Bbil-TX (0.1 μg), TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1 concentrations were measured in the serum. TNF-α levels were increased 1 h after injection of Bil-TX and no detectable production was observed at the later time intervals studied (Figures 7(b), 7(c), and 7(d)). Bbil-TX caused a significant increase in IL-6 release between 1 and 3 h, respectively, in serum collected after injection of venom compared with the control (Figure 7(c)). However, increased levels of IL-1 were detected between 1, 3, 6, and 12 h, respectively (Figure 7(d)).

Figure 7.

(a) Edema-forming activity of Bbil-TX in mice. Induction of edema by toxins (0.1, 1, and 5 μg/mL), injected s.c. in the footpad of mice. At various time intervals the increase in footpad volume, as compared to controls, was expressed as percent edema. Each point represents the mean ± SD of four animals. Levels of TNF-α (b), IL-6 (c), and IL-1 (d), in the serum after injection of Bbil-TX. Animals were injected i.m. with Bbil-TX (1.0 mg/kg) or sterile saline alone (control) in a final volume of 100 μL. IL-1 and IL-6 were quantified by specific ELISA, and TNF-α was quantified by cytotoxic activity on L929 cells in serum collected at the indicated time intervals after Bbil-TX or saline injection as described in Materials and Methods. Each bar represents mean ± SEM of 7 animals. *P < 0.05 when compared with the corresponding control groups.

4. Discussion

The purification procedure for basic PLA2s developed by [20–22] showed to be also efficient for the obtainment of neurtoxin “ex vivo” and myotoxin from Bothriopsis bilineata snake venom. Fractionation of this crude venom by single-step chromatography in a column μ-Bondapack C-18 coupled to a system of reversed-phase HPLC was carried out and as a result of the proposed method, several toxins have been efficiently purified. Fraction 7 was named Bbil-TX (PLA2). SDS-PAGE showed evidence that Bbil-TX isolated PLA2s have an Mr of ~14 kDa for the monomers, similar to basic PLA2s isolated from other venoms (data not shown) [23]. The conserved residues Y28, G30, G32, D49, H48, and Y52 are directly or indirectly linked in the catalyses of the Bbil-TX.

The molecular masses obtained by mass spectrometry showed to be similar to that of other snake venom PLA2s [22, 24, 25]. The amino acid composition of the Bbil-TX PLA2 toxin suggests the presence of 14 half-Cys residues, providing the basis for a common structural feature of PLA2 in the formation of its seven disulfide bridges [20, 21, 26] and a high content of basic and hydrophobic residues, that provides a explication important in the interaction of the PLA2 with negatively charged phospholipids of cells membranes [27]. Such an interaction is important to explain the effect of these enzymes on different cells types, both prokariotes and eukariotes [28, 29].

Comparison of the amino acid sequence of Bbil-TX PLA2 showed high homology with other neurotoxic and myotoxic PLA2s from Lachesis and Crotalus genera (Figure 4). Sequence homology studies had shown that there are extremely conserved positions in the PLA2s. In positions 1 and 2, there is a predominance of the amino acid sequence (HL), in position 4 (Q), and in positions 5 to 7 (FNK). One of the highly conserved regions in the amino acid sequences of PLA2 is the Ca2+-binding loop, segment from …YGCYCGXGG… and HD(49)CC. The calcium ion is coordinated by three main chain oxygen atoms from residues (Y)28, (G)30, (G)32, and two carboxylate oxygen atoms of (D)49. Two generally conserved solvent water molecules complete the coordination sphere of the calcium ion forming a pentagonal bipyramidal geometry. It is believed that two disulfide bridges (C)27–(C)119 and (C)29–(C)45 ensure the correct relative orientation of the calcium-binding loop in relation to the amino acids of the catalytic network [30]. The residues (H)48, (Y)52, and (D)99 which are responsible for catalytic activity have an ideal stereochemistry with the presence of the so-called “catalytic network”, a system of hydrogen bonds which involves the catalytic triad [30, 31]. Residues forming the Ca2+-binding loop and the catalytic network of Bbil-TX PLA2 show a high conservation grade, reflecting the nondecreased catalytic activity.

The PLA2 activity was shown to be higher in Bbil-TX PLA2 (24.75 ± 2.28 nmoles/min/mg) when compared with the whole venom (8.15 ± 1.24 nmoles/min/mg). PLA2 enzyme from snake venom shows classic Michaelis–Menten behavior against micellar substrates [32]. With a synthetic substrate, Bbil-TX PLA2 behaved allosterically, especially at low concentrations, which is in agreement with the results obtained by [23] for the PLA2 of Bothrops jararacussu venom and Damico et al. [19] for the PLA2 isoform purified from Lachesis muta muta venom. Using the same synthetic nonmicellar substrate, it was also possible to observe that the dependence of activity on substrate concentration was markedly sigmoidal for the PrTX-III from Bothrops pirajai [33].

PLA2s from crotalic venoms have showed a similar behavior to the one presented by bothropic PLA2s with the same substrate used in the kinetic studies to Bbil-TX PLA2 [14, 34]. Despite the structural and functional differences among bothropic and crotalic PLA2s, both show allosteric behavior in the presence of the same substrate.

The PLA2 activity could be verified with different pH levels; the optimum pH of basic PLA2s is around 7.0 and 8.5 [32, 35]. Bbil-TX PLA2 can be considered basic since its highest activity is evidenced at pH 8.0. Temperature is another kinetic parameter utilized to characterize the PLA2 (Asp49). It has been shown that PLA2 from Naja naja naja is very stable in extreme temperatures such as 100°C [35]. The optimum temperature of Bbil-TX PLA2 was around 37°C, but at 40–45°C, the Bbil-TX PLA2 activity did not present a huge decrease.

A strict requirement for Ca2+ is characteristic of some PLA2 [5]. Bbil-TX PLA2 showed typical Ca2+-dependent PLA2 activity similar to other PLA2s, and this activity was lower in the presence of other cations. [14, 35–38] observed the same for other PLA2 from snake venom.

The crotapotin isoform from Crotalus durrissus cascavella (F3) venom inhibit significantly the PLA2 activity of Bbil-TX by approximately 50%. Our results are in agreement with the finding by [14, 21, 39] who reported that highly purified crotapotin can inhibit pancreatic, bee, and other snake venom PLA2s, and Bonfim et al. [23], who reported that crotapotins from Crotalus durissus terrificus (F7), Crotalus durissus collilineatus (F3 and F4), and Crotalus durissus cascavella (F3 and F4) decreased the catalytic activity of BJ IV (PLA2 from Bothrops jararacussu) by 50%. Together, these results suggest that crotapotin may bind to bothropic PLA2 in a manner similar to that from crotalic PLA2.

Bbil-TX PLA2 increases the plasmatic CK levels after i.m. injection (Figure 6(a)), revealing drastic local myotoxicity. This myotoxicity induced by snake venoms, including Botrhiopsis bilineata, may result from the direct action of myotoxins on the plasma membranes of muscle cells, or indirectly, as a consequence of vessel degenerations and ischemia caused by hemorrhagins or metaloproteases. Bbil-X PLA2 contributes significantly to local myotoxic action in vivo. It was already demonstrated that the snake venom PLA2s are the principal cause of local damage [40]. Myotoxic PLA2s affect directly the plasma membrane integrity of muscle cells, originating an influx of Ca2+ ions to the citosol that starts several degenerative events with irreversible cell injures [41]. The binding sites of myotoxins on the plasma membranes are not clearly established, although two types have been proposed: (a) negatively charged phospholipids [42], present on membranes of several cell types, explaining the high in vitro cytotoxic action of these enzymes [28, 43, 44], and (b) protein receptors, which make muscle cells more susceptible to myotoxin action [28].

All these biological effects induced by the toxin occur in the presence of a measurable PLA2 activity. Although the catalytic activity of PLA2s contributes to pharmacological effects, it is not a prerequisite [21, 26, 29]. However, further studies are necessary to identify the structural determinants involved in these pharmacological activities.

Some authors, [21, 41, 45, 46], have proposed several models to explain PLA2 catalytic and pharmacological activities. In these models PLA2 has two separated places; one is responsible for catalytic activity and the other for biological activity expression. According to them, the pharmacological place would be located on the surface of PLA2 molecules. According to the model proposed by [47], the anti-coagulant place would be located in a region between the 53 and 76 residues, considering this region charged positively in the PLA2 with high anticoagulant activity. In PLA2 with moderate or low anticoagulant activity, there is a predominancy of negative charges.

Further research in identifying target proteins will help determine details of the mechanisms of the pharmacological effects at the cellular and molecular levels [48]. Studies in these areas will result in new, exciting, and innovative opportunities and avenues in the future, both in finding answers to the toxicity of PLA2 enzymes and in developing proteins with novel functions.

PLA2s from snake venoms exert a large number of pharmacological activities due to a process of accelerated evolution through which a high mutational rate in the coding regions of their genes has allowed the development of new functions, mainly associated with the exposed regions of the molecules [29]. The integral analysis of the inflammation elicited by Bbil-TX in the mouse serum performed in the present study allowed a parallel evaluation of the increase in microvascular permeability and the production of various inflammatory mediators. Bbil-TX induced an increase in vascular permeability in the paw of mice. This is in agreement with previous observations on the edema-forming activity of similar molecules in the rodent footpad model [49, 50].

The increase of vascular permeability was detected early after Bbil-TX injection and developed rapidly, indicating that the observed plasma extravasation is primarily due to formation of endothelial gaps in vessels of microcirculation. The main edema formation occurred 1 h after the injection of Bbil-TX with constant decrease. Bbil-TX caused paw edema in mice with a time course similar to that reported for other PLA2s from Bothrops venoms in mice and rats, that is, a fairly rapid onset (generally ≤ 3 h to peak) followed by a gradual decline over the following 24 h [51–54].

The mediators involved in this effect of Bbil-TX myotoxin were not addressed in this study. However, the immediate plasma extravasation in response to Bbil-TX strongly suggests the involvement of vasoactive mediators derived from mast-cell granules. This strongly suggests that enzymatic phospholipid hydrolysis plays a significant role in this event.

Cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, are also relevant mediators for leukocyte migration and participate in several inflammatory conditions. Our results showed that Bbil-TX induced an increase in TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1 in the serum [55]. Thus, our results suggest that IL-1 may contribute to the leukocyte influx induced by Bbil-TX. In addition, the similarity observed in the time course of IL-6 and IL-1 increase in the serum may indicate a positive regulatory role for IL-1 on the release of IL-6 induced by Bbil-TX. IL-6, an important mediator of inflammation, causes leukocytosis characterized by a rapid neutrophilia by releasing of PMN leukocytes from the bone marrow [56, 57]. In addition, IL-6 upregulates intercellular-adhesion-molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression by endothelial cells but decreases the levels of L-selectin on circulating PMN leukocytes contributing to firm adhesion, the next step of cell migration [58].

TNF-α is also likely to be involved in leukocyte infiltration induced by Bbil-TX, since the PLA2 caused a significant increase of TNF-α levels in the serum. TNF-α is likely to induce the expression of E-selectin, CD11b/CD18, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and triggers the release of several cytokines such as IL-1 and IL-6 and eicosanoids. Thus, our results suggest that TNF-α may have a role in the expression of CD18 and the release of other cytokines following Bbil-TX injection, thereby being relevant for neutrophil influx and for increase of vascular permeability. It is interesting that TNF-α and IL-6, as well as IL-1, may induce or potentiate the expression and release of group IIA PLA2s [59, 60].

In conclusion, Bbil-TX induces a marked inflammatory reaction in the mouse serum. Since basic myotoxic PLA2s are abundant in snake venoms, these toxins must play a relevant role in the proinflammatory activity that characterizes this venom. The fact that Bbil-TX elicited a stronger inflammatory reaction argues in favor of a role of enzymatic phospholipid hydrolysis in this phenomenon, either through the direct release of arachidonic acid from plasma membranes or through activation of intracellular processes in target cells.

Accumulating evidences have strongly shown that venom PLA2s are among the major mediators of myonecrosis [40], hemolysis, mast cell degranulation, and edema formation [3].

PLA2s isolated from Bothrops venoms are frequently myotoxic [26] and can cause edema in rats and mice [39, 45, 49, 54]. These results suggest that, for some PLA2s, catalytic activity plays a role in the edematogenic effect.

Ethical Approval

The animals and research protocols used in this study followed the guidelines of the Ethical Committee for use of animals of ECAE-IB-UNICAMP SP, Brazil (protocol number 1931-1) and international laws and policies. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

References

- 1.McDiarmid RW, Campbell JA, Touré T. Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. 1999;1 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barros SF, Friedlanskaia I, Petricevich VL, Kipnis TL. Local inflammation, lethality and cytokine release in mice injected with Bothrops atrox venom. Mediators of Inflammation. 1998;7(5):339–346. doi: 10.1080/09629359890866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petricevich VL. Cytokine and nitric oxide production following severe envenomation. Current Drug Targets. 2004;3(3):325–332. doi: 10.2174/1568010043343642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris JB, Cullen MJ. Muscle necrosis caused by snake venoms and toxins. Electron Microscopy Reviews. 1990;3(2):183–211. doi: 10.1016/0892-0354(90)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennis EA. Divesity of group tupes, regulation, and function oh phopholipase A2 . The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269:13057–11306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowton DL, Seeds MC, Fasano MB, Goldsmith B, Bass DA. Phospholipase A2 and arachidonate increase in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after inhaled antigen challenge in asthmatics. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1997;155(2):421–425. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stadel JM, Hoyle K, Naclerio RM, Roshak A, Chilton FH. Characterization of phospholipase A2 from human nasal lavage. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 1994;11(1):108–113. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.11.1.8018333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vadas P. Elevated plasma phospholipase A2 levels: correlation with the hemodynamic and pulmonary changes in gram-negative septic shock. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 1984;104(6):873–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroder T, Kivilaakso E, Kinnunen PKJ, Lempinen M. Serum phospholipase A2 in human acute pancreatitis. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 1980;15(5):633–636. doi: 10.3109/00365528009182227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakae H, Endo S, Inada K, et al. Plasma concentrations of type II phospholipase A2, cytokines and eicosanoids in patients with burns. Burns. 1995;21(6):422–426. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(95)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vadas P, Pruzanski W. Role of secretory phospholipases A2 in the pathobiology of disease. Laboratory Investigation. 1986;55(4):391–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stefanski E, Pruzanski W, Sternby B, Vadas P. Purification of a soluble phospholipase A2 from synovial fluid in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Biochemistry. 1986;100(5):1297–1303. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a121836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seilhamer JJ, Pruzanski W, Vadas P, et al. Cloning and recombinant expression of phospholipase A2 present in rheumatoid arthritic synovial fluid. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264(10):5335–5338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holzer M, Mackessy SP. An aqueous endpoint assay of snake venom phospholipase A2 . Toxicon. 1996;34(10):1149–1155. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(96)00057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schagger HA, Von Jagow G. Comassie blue-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for direct visualization of polypeptides during electrophoresis. Analytical Biochemistry. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90179-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinrikson RL, Meredith SC. Amino acid analysis by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography: precolumn derivatization with phenylisothiocyanate. Analytical Biochemistry. 1984;136(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schumacher JH, O’Garra A, Shrader B, et al. The characterization of four monoclonal antibodies specific for mouse IL-5 and development of mouse and human IL-5 enzyme-linked immunosorbent. Journal of Immunology. 1988;141(5):1576–1581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruff MR, Gifford GE. Purification and physico-chemical characterization of rabbit tumor necrosis factor. Journal of Immunology. 1980;125(4):1671–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damico DCS, Lilla S, De Nucci G, et al. Biochemical and enzymatic characterization of two basic Asp49 phospholipase A2 isoforms from Lachesis muta muta (Surucucu) venom. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2005;1726(1):75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ponce-Soto LA, Barros JC, Marangoni S, et al. Neuromuscular activity of BaTX, a presynaptic basic PLA2 isolated from Bothrops alternatus snake venom. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C. 2009;150(2):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ponce-Soto LA, Bonfim VL, Rodrigues-Simioni L, Novello JC, Marangoni S. Determination of primary structure of two isoforms 6-1 and 6-2 PLA 2 D49 from Bothrops jararacussu snake venom and neurotoxic characterization using in vitro neuromuscular preparation. Protein Journal. 2006;25(2):147–155. doi: 10.1007/s10930-006-0006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ponce-Soto LA, Lomonte B, Gutiérrez JM, Rodrigues-Simioni L, Novello JC, Marangoni S. Structural and functional properties of BaTX, a new Lys49 phospholipase A2 homologue isolated from the venom of the snake Bothrops alternatus . Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1770(4):585–593. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonfim VL, Toyama MH, Novello JC, et al. Isolation and enzymatic characterization of a basic phospholipase A 2 from Bothrops jararacussu snake venom. Protein Journal. 2001;20(3):239–245. doi: 10.1023/a:1010956126585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponce-Soto LA, Martins-De-souza D, Marangoni S. Neurotoxic, myotoxic and cytolytic activities of the new basic PLA2 isoforms BmjeTX-I and BmjeTX-II isolated from the Bothrops marajoensis (marajó lancehead) snake venom. Protein Journal. 2010;29(2):103–113. doi: 10.1007/s10930-010-9229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Denegri ME, Acosta OC, Huancahuire-Vega S, et al. Isolation and functional characterization of a new acidic PLA2 Ba SpII RP4 of the Bothrops alternatus snake venom from Argentina. Toxicon. 2010;56(1):64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutierrez JM, Lomonte B. Efectos Locales en El Envenenamiento Ofídico en America Latina Cap. 32 Efectos Locales en El Envenenamiento Ofídico en America Latina—Animais pessonhentos No Brasil: Biologia. São Paulo, Brazil: Sarvier; 2003. (Clínica e Terapêutica dos Acidentes). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke JE, Dennis EA. Phospholipase A2 biochemistry. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy. 2009;23(1):49–59. doi: 10.1007/s10557-008-6132-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lomonte B, Angulo Y, Sasa M, Gutiérrez JM. The phospholipase A2 homologues of snake venoms: biological activities and their possible adaptive roles. Protein and Peptide Letters. 2009;16(8):860–876. doi: 10.2174/092986609788923356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kini RM. Excitement ahead: structure, function and mechanism of snake venom phospholipase A2 enzymes. Toxicon. 2003;42(8):827–840. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott DL, Otwinowski Z, Gelb MH, Sigler PB. Crystal structure of bee-venom phospholipase A2 in a complex with a transition-state analogue. Science. 1990;250(4987):1563–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.2274788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doley R, Kini RM. Protein complexes in snake venom. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2009;66(17):2851–2871. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0050-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breithaupt H. Enzymatic characteristics of crotalus phospholipase A2 and the crotoxin complex. Toxicon. 1976;14:221–233. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(76)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rigden DJ, Hwa LW, Marangoni S, Toyama MH, Polikarpov I. The structure of the D49 phospholipase A2 piratoxin III from Bothrops pirajai reveals unprecedented structural displacement of the calcium-binding loop: possible relationship to cooperative substrate binding. Acta Crystallographica D. 2003;59(2):255–262. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902021467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beghini DG, Toyama MH, Hyslop S, Sodek LC, Novello, Marangoni S. Enzymatic characterization of a novel phospholipase A2 from Crotalus durissus cascavella rattlesnake (maracambóia) venom. Journal of Protein Chemistry. 2000;19(8):679–684. doi: 10.1023/a:1007152303179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kini RM. Phospholipase A2 a complex multifunctional protein puzzle. In: Kini RM, editor. Enzymes: Structure, Function and Mechanism. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romero-Vargas FF, Ponce-Soto LA, Martins-de-Souza D, Marangoni S. Biological and biochemical characterization of two new PLA2 isoforms Cdc-9 and Cdc-10 from Crotalus durissus cumanensis snake venom. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C. 2010;151(1):66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calgarotto AK, Damico DCS, Ponce-Soto LA, et al. Biological and biochemical characterization of new basic phospholipase A2 BmTX-I isolated from Bothrops moojeni snake venom. Toxicon. 2008;51(8):1509–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Damico DCS, Bueno LGF, Rodrigues-Simioni L, Marangoni S, da Cruz-Höfling MA, Novello JC. Functional characterization of a basic D49 phospholipase A2 (LmTX-I) from the venom of the snake Lachesis muta muta (bushmaster) Toxicon. 2006;47(7):759–765. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Landucci ECT, Toyama M, Marangoni S, et al. Effect of crotapotin and heparin on the rat paw oedema induced by different secretory phospholipases A2 . Toxicon. 2000;38(2):199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(99)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutiérrez JM, Ownby CL. Skeletal muscle degeneration induced by venom phospholipases A 2: insights into the mechanisms of local and systemic myotoxicity. Toxicon. 2003;42(8):915–931. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montecucco C, Gutiérrez JM, Lomonte B. Cellular pathology induced by snake venom phospholipase A2 myotoxins and neurotoxins: common aspects of their mechanisms of action. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2008;65(18):2897–2912. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8113-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Díaz C, León G, Rucavado A, Rojas N, Schroit AJ, Gutiérrez JM. Modulation of the susceptibility of human erythrocytes to snake venom myotoxic phospholipases A2: role of negatively charged phospholipids as potential membrane binding sites. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2001;391(1):56–64. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Angulo Y, Lomonte B. Differential susceptibility of C2C12 myoblasts and myotubes to group II phospholipase A2 myotoxins from crotalid snake venoms. Cell Biochemistry and Function. 2005;23(5):307–313. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gutierrez JM, Lomonte B, Chaves F. Pharmacological activities of a toxic phospholipase A isolated from the venom of the snake Bothrops asper . Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C. 1986;84(1):159–164. doi: 10.1016/0742-8413(86)90183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutiérrez JM, Ponce-Soto LA, Marangoni S, Lomonte B. Systemic and local myotoxicity induced by snake venom group II phospholipases A2: comparison between crotoxin, crotoxin B and a Lys49 PLA2 homologue. Toxicon. 2008;51(1):80–92. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ponce-Soto LA, Martins-De-souza D, Marangoni S. Neurotoxic, myotoxic and cytolytic activities of the new basic PLA2 isoforms BmjeTX-I and BmjeTX-II isolated from the Bothrops marajoensis (marajó lancehead) snake venom. Protein Journal. 2010;29(2):103–113. doi: 10.1007/s10930-010-9229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kini RM, Evans HJ. A model to explain the pharmacological effects of snake venom phospholipases A2 . Toxicon. 1989;27(6):613–635. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(89)90013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Križaj I. Ammodytoxin: a window into understanding presynaptic toxicity of secreted phospholipases A2 and more. Toxicon. 2011;58(3):219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Landucci ECT, Castro RC, Pereira MF, et al. Mast cell degranulation induced by two phospholipase A2 homologues: dissociation between enzymatic and biological activities. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;343(2-3):257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01546-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chaves F, León G, Alvarado VH, Gutiérrez JM. Pharmacological modulation of edema induced by Lys-49 and Asp-49 myotoxic phospholipases A2 isolated from the venom of the snake Bothrops asper (terciopelo) Toxicon. 1998;36(12):1861–1869. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chacur M, Picolo G, Gutiérrez JM, Teixeira CFP, Cury Y. Pharmacological modulation of hyperalgesia induced by Bothrops asper (terciopelo) snake venom. Toxicon. 2001;39(8):1173–1181. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Faria L, Antunes E, Bon C, de Araújo AL. Pharmacological characterization of the rat paw edema induced by Bothrops lanceolatus (Fer de lance) venom. Toxicon. 2001;39(6):825–830. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carneiro AS, Ribeiro OG, De Franco M, et al. Local inflammatory reaction induced by Bothrops jararaca venom differs in mice selected for acute inflammatory response. Toxicon. 2002;40(11):1571–1579. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(02)00174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanashiro MM, De Escocard RCM, Petretski JH, et al. Biochemical and biological properties of phospholipases A2 from Bothrops atrox snake venom. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2002;64(7):1179–1186. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Teixeira CFP, Landucci ECT, Antunes E, Chacur M, Cury Y. Inflammatory effects of snake venom myotoxic phospholipases A2 . Toxicon. 2003;42(8):947–962. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suwa T, Hogg JC, English D, Van Eeden SF. Interleukin-6 induces demargination of intravascular neutrophils and shortens their transit in marrow. American Journal of Physiology. 2000;279(6):H2954–H2960. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Van Snick J. Interleukin-6: an overview. Annual Review of Immunology. 1990;8:253–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crowl RM, Stoller TJ, Conroy RR, Stoner CR. Induction of phospholipase A2 gene expression in human hepatoma cells by mediators of the acute phase response. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266(4):2647–2651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suwa T, Hogg JC, Quinlan KB, Van Eeden SF. The effect of interleukin-6 on L-selectin levels on polymorphonuclear leukocytes. American Journal of Physiology. 2002;283(3):H879–H884. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00185.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schalkwijk C, Pfeilschifter J, Marki F, Van den Bosch H. Interleukin-1β, tumor necrosis factor and forskolin stimulate the synthesis and secretion of group II phospholipase A2 in rat mesangial cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1991;174(1):268–275. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)90515-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]