Abstract

Gold nanoparticles (GNPs) conjugates of water soluble ionic photosensitizer (PS), purpurin-18-N-methyl-D-glucamine (Pu-18-NMGA), were synthesized using various molar ratios between HAuCl4 and Pu-18-NMGA without adding any particular reducing agents and surfactants. The PS-GNPs conjugates showed long wavelength absorption of range 702–762 nm, and their different shapes and diameters depend on the molar ratios used in the synthesis. In vitro anticancer efficacy of the PS-GNPs conjugates was investigated by MTT assay against A549 cells, resulting in higher photodynamic activity than that of the free Pu-18-NMGA. Among the PS-GNPs conjugates, the GNPs conjugate from the molar ratio of 1 : 2 (Au(III): Pu-18-NMGA) exhibits the highest photodynamic activity corresponding to bigger size (~60 nm) of the GNPs conjugate which could efficiently transport the PS into the cells than that of smaller size of the GNPs conjugate.

1. Introduction

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a promising noninvasive cancer treatment by using a combination of photosensitizer (PS), light, and oxygen [1–3]. For excellent photodynamic activity, PS should be penetrated into the tumor cells sufficiently [4]. Most of PSs are hydrophobic and thus locate preferentially in the lipid bilayers of organelle membranes in cancer cells. However, the hydrophobic nature of PSs makes them insoluble under physiological conditions and hinders to reach the accumulation in the tumor sites [5]. Therefore, for both hydrophobic and hydrophilic (amphiphilic) environments of PSs, introduction of water soluble PS with suitable carrier is a one potential method [6–8]. On the other hand, highly water soluble (hydrophilic) PSs allow poor cellular uptake based on a short pharmacological half-life which may have limit to penetrate through the tissue and cell membranes [9–11].

Nanoparticles (NPs) [12–14] are promising carrier system of PSs that could be protected from being uptaken by the reticuloendothelial system and extended the circulation time of NPs in the blood, and, finally, preferentially accumulated in tumor sites through the so-called “enhanced permeability and retention (EPR)” effect [15–17]. Among the NPs, gold nanoparticles (GNPs) are highly efficient PDT drug delivery platform with good advantages based on their chemical inertness and minimum toxicity that has potential applications in biomedicine such as photothermal therapy (PTT) [18–21] of cancer, gene and drug delivery, biological imaging, and biosensing [22–26]. In addition, GNPs have large surface-to-volume ratios and easy tuning of the NPs size, resulting in penetration into tumor cells and intracellular localization at endosomes/lysosomes of the cells, and finally targeting at mitochondrial of cancer cells induces apoptosis to destroy the cancer cells [27–31]. It is noted that the size of the GNPs plays a big role in their uptake at the cellular level leading to different PDT activity. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are few reports for relationship between GNPs and its size effect on photodynamic activity [28].

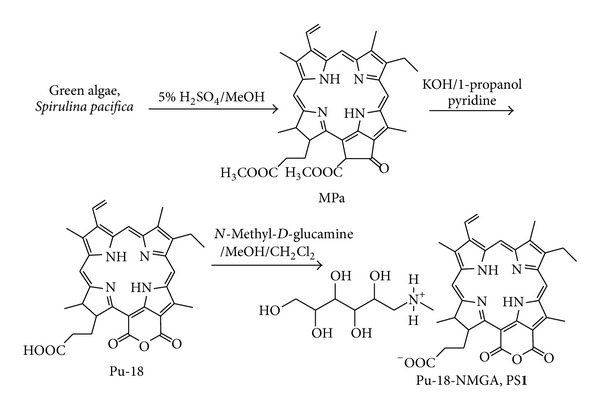

Previously, we developed new synthesis of PS-GNPs conjugate using water soluble ionic purpurin-18-N-methyl-D-glucamine (Pu-18-NMGA, PS1, Figure 1) and this conjugate showed better in vitro anticancer efficacy than that of free PS1 against A549 lung cancer cells [32].

Figure 1.

Synthetic method of N-methyl-D-glucamine salt of purpurin-18 (Pu-18-NMGA, PS1).

In this paper, we have synthesized various sizes of PS-GNPs conjugates using a simple single-step synthesis from different molar ratios of HAuCl4/PS1 without adding any particular reducing agents and surfactants, and showed size effect allowed different photodynamic activity results of the conjugates as an important factor for PDT. We evaluated in vitro anticancer efficacy of the PS-GNPs conjugates against A549 cells using MTT assay.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

All reagents were purchased from Aldrich and used without further purification. All aqueous solutions were made using triply distilled water. All reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using Merck 60 silica gel F254 precoated (0.2 mm thickness) glass-backed sheets. Silica gel 60A (230–400 mesh, Merck) was used for column chromatography. The 1H NMR spectra were obtained using a Varian spectrometer (500 MHz) at Biohealth Products Research Center (BPRC) at Inje University. The chemical shifts (δ) are given in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS, 0 ppm). High-resolution fast atom bombardment mass (HRFABMS) spectra were obtained with a Jeol JMS700 high-resolution mass spectrometer at the Daegu center of KBSI, Kyungpook National University, Korea.

The PS1 and PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e were characterized by a combination analysis of 1H-NMR and UV-vis spectroscopies, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and infrared (IR) spectroscopy. UV-vis absorption spectra were recorded using a SCINCO S-3100 UV-vis spectrophotometer using 1 cm quartz cuvette. TEM images were performed on a JEOL, JEM 2011. A typical sample for TEM was prepared by drying of a drop of the solution at room temperature on a carbon-coated copper grid. IR spectra were measured on a Varian-640 FT-IR spectrometer.

2.2. Synthesis

Methyl pheophorbide-a (MPa) [33], purpurin-18 (Pu-18) [34], and N-methyl-D-glucamine salt of purpurin-18 (Pu-18-NMGA, PS1) [32] were prepared according to the procedures in literature, and all analytical data are identical with those in the literatures.

N-Methyl-D-Glucamine Salt of Purpurin-18 (Pu-18-NMGA, PS1) [32] —

To a solution of Pu-18 (56.4 mg, 0.1 mmol) in MeOH/CH2Cl2 (3 : 1, 10 mL), a solution of NMGA (39.0 mg, 0.2 mmol) in MeOH/water (1 : 2, 20 mL) was added and the mixture was stirred for 4 h. The organic solvents were evaporated under vacuum and the resulting aqueous solution was filtered through a membrane (20 μm) and freeze-dried to give PS1. Yield: 68.0 mg (87%). UV-vis (water): λ, nm (log ε) 282 (0.34), 379 (0.55), 388 (0.58), 405 (0.61), 501 (0.13), 561 (0.11), 652 (0.28), 702 (0.21). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD, 25°C, TMS) δ, ppm 9.68 (1H, s, H-5), 9.39 (1H, s, H-10), 8.95 (1H, s, H-20), 8.69 (2H, s, H-NH gluc), 7.80 (1H, m, H-31), 6.24 and 6.12 (2H, dd, H-32), 5.07 (1H, m, H-18), 4.49 (1H, m, H-17), 4.05 (2H, m, H-1 gluc), 3.83 (4H, m, OH-2,3,4,5 gluc), 3.69 (4H, m, H-2,3,4,5 gluc), 3.63 (3H, s, H-12), 3.48 (2H, m, H-81), 3.21 (3H, s, H-21), 3.18 (1H, m, OH-1 gluc), 3.07 (2H, dd, H-6 gluc), 3.03 (3H, s, H-71), 2.74 (3H, s, H-7 gluc), 2.46 (2H, m, H-171), 2.26 (3H, m, H-172), 1.95 (3H, m, H-181), 1.83 (3H, d, H-82), 1.69 (1H, br s, NH), 1.32 (1H, br s, NH). HRFABMS: calcd for C40H50N5O10 ([M + H]+) 760.3558, found 760.3554.

Synthesis of PS-GNPs Conjugates 2a–2e —

The GNPs were synthesized according to the seed growth method [25] with some modifications. PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e were synthesized from different molar ratios between Au(III) and PS1 through reduction of chloroauric acid (HAuCl4) with no use of reducing agent or surfactant.

Preparation of Seed Solution of PS-GNPs Conjugate —

0.002 M solution of PS1 (5 mL) was mixed with 0.001 M HAuCl4 (2.5 mL) in a 50 mL flat bottom flask and was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The solution color was changed from yellow to greenish black, and then the solution was stored at room temperature.

Growth of PS-GNPs Conjugate —

0.001 M solution of HAuCl4 (25 mL) is added to suitable concentration (for various molar ratios between Au(III) and PS1) of PS1 solution (25 mL) in a 250 mL flat bottom flask (the color of solution was changed from yellow to green). Then 0.005 M AgNO3 solution (1 mL) was added to the mixture. To this mixture, the seed solution (100 μL) was added to the center of the solution. Then the flask was never moved, so that the seed started to grow in the growth solution. After few minutes, the each PS-GNPs conjugate was obtained and washed with water for several times and was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min and resuspended in water. Selected data for 2a: UV-vis (water): λ, nm (logε) 275 (0.36), 373 (0.43), 388 (0.46), 393 (0.48), 524 (0.21), 560 (0.25), 672 (0.23), 714 (0.35). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD, 25°C, TMS) δ, ppm 8.91 (2H, s, H-5 and H-1 gluca), 8.74 (1H, s, H-10), 8.64 (3H, s, H-20 and H-NH gluc), 7.82 (1H, m, H-31), 6.21and 6.12 (2H, dd, H-32), 4.95 (1H, m, H-18), 4.41 (1H, m, H-17), 3.62 (3H, s, H-121), 3.41 (2H, d, H-81), 3.21 (3H, s, H-21), 3.16 (2H, d, H-6 gluc), 2.82 (6H, s, H-7 gluc and 71), 2.63 (2H, m, H-171), 2.30 (2H, m, H-172), 1.75 (3H, d, H-181), 1.33 (3H, m, H-81), 0.88 (1H, br s, NH), 0.08 (1H, br s, NH). ATR IR (cm−1): 3400 (w, stretching –NH2 +–), 1760 (s, stretching C=O), 1525 (s), 1300–1100 (stretching, bending C=O).

2.3. Cell Culture and Photo Irradiation

A549 human lung carcinoma cell lines were obtained from the cell line bank at Seoul National University's cancer research center and were grown in medium RPMI-1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) with 10% fetal bovine serum, glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin at 37°C in humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma-Aldrich), microscope (Olympus, CK40-32 PH), ELISA-reader (BioTek, SynergyHT), trypsin-EDTA, solution and incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) were used. The PDT was carried out using a diode laser generator apparatus (BioSpec LED, Russia) equipped with a halogen lamp, a bandpass filter (640–710 nm), and a fiber optics bundle. The duration of light irradiation, under PDT treatment, is calculated taking into account the empirically found effective dose of light energy in J·cm2.

2.4. MTT Assay and Cell Viability

A549 Cells (1 × 105 cells/well) in 100 μL of the mixed medium were placed in a 96-well plate and incubated for 48 h (37°C, 5% CO2). The medium was removed and the cultures were washed 3 times with physiologic saline. And the Pu-18-NMGA PS1 (0.8–25 μg/mL) or corresponding amount of the PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e (constant amount of the PS1) in 100 μL of the mixed medium was added in each well. 24 h later, the Pu-18-NMGA PS1 or each PS-GNPs conjugate solution was discarded, and the cultures were washed 3 times with physiological saline and then medium (100 μL/well) was added. The cultures were then subjected to the irradiation (2 J·cm−2) at the distance of 20 cm for 15 min, followed by an 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl)-2,5-biphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay to evaluate their sensitivity to PDT. For the MTT assay, MTT solution (10 μL) was added to each cell-culture well and cultured in the incubator for 3 h. Detergent solution (TACS, Trevigen, 200 μL) was added to the culture, shaken for 10 min, and the absorbance was measured with an ELISA reader at 570 nm. Measurements were performed 3 h, 24 h, and 48 h incubation time after the irradiation, respectively. Each group consisted of 3 wells.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preparation of Gold Nanoparticles Conjugates

The commonly used synthetic way of GNPs is a reduction method of Au(III) salt (usually from HAuCl4) using sodium citrate in water [35]. In this method, sodium citrate has a double role as a weak reducing agent as well as a capping agent that stabilizes the NPs. The particle size is controlled by a ratio between citrate and AuCl4 − ions. Higher concentration of citrate afforded smaller particle size [35].

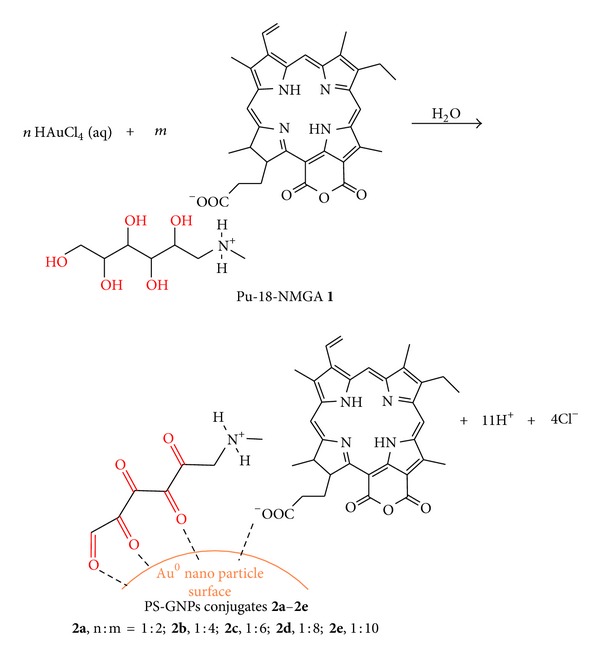

However, in this work, we used hydrophilic PS1 and Au(III) without any additional reducing agents and surfactants [32]. The hydroxyl groups of NMGA in PS1 have important roles as a reducing agent as well as a stabilizer through the electrically charged functional groups (i.e., carboxylate and amine groups) in forming the PS-GNPs conjugates [9]. PS1 was obtained from the carboxyl group of purpurin-18 (Pu-18) and the amine group of NMGA by simple and effective method (Figure 1). Pu-18 was synthesized from a conversion of methyl pheophorbide a (MPa) by air oxidation in n-propanol with KOH [34]. MPa was obtained from Spirulina pacifica algae by the procedure reported by Smith et al. [33]. PS-GNPs conjugates were prepared from the reaction of different molar ratios between Au(III) and PS1 (2a, 1 : 2; 2b, 1 : 4; 2c, 1 : 6; 2d, 1 : 8; 2e, 1 : 10) in water to afford different particle sizes (Figure 2). The structures of the water soluble PS1 and the PS-GNPs conjugates were confirmed by 1H-NMR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and UV-vis spectroscopy (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Synthetic method of PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e with various molar ratios between gold and Pu-18-NMGA (n and m are molar ratios).

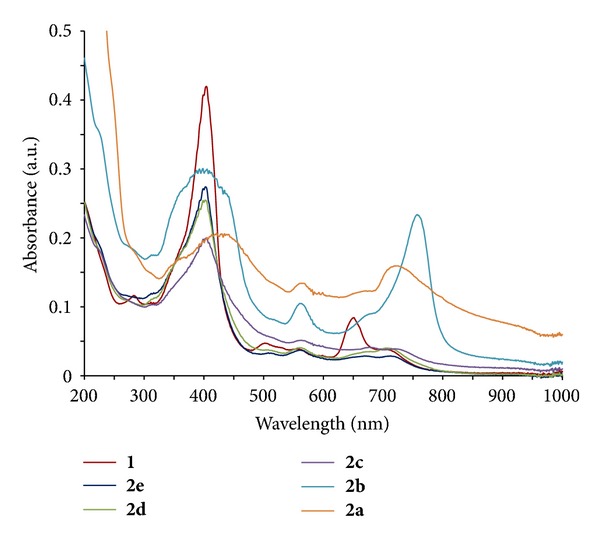

Figure 3.

UV-vis spectra of (a) PS1 and PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e with various molar ratios between gold and Pu-18-NMGA in water (2a, Au:Pu-18-NMGA = 1 : 2; 2b, 1 : 4; 2c, 1 : 6; 2d, 1 : 8; 2e, 1 : 10).

The water soluble PS1 acts not only as a reducing agent, but also as a capping agent in the reduction of HAuCl4 for synthesis of PS-GNPs conjugates. The formation of PS-GNPs conjugates is stable in the aqueous solution due to the adsorption of oxidized PS1 on the surface of the GNPs through a strong coordinate-covalent bond between carboxylate on PS1 and gold metal. So the binding strength of PS1 on the GNPs surface is enough to allow accumulation of PS1 in culture medium or in vivo [8, 24, 36, 37]. Therefore, a large amount of water soluble PS was generally used in order to get stable GNPs. Hence, we have used five different concentration ratios between Au(III) and PS1 in order to find suitable concentration ratio that gives optimal size of the PS-GNPs conjugates for best photodynamic activity result.

3.2. UV-Vis Spectroscopic Investigation and Size Analysis by TEM Images

Figure 3 shows the UV-vis absorption spectra of the PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e in water. In each conjugate, typical plasmon resonance band of the GNPs was appeared at 506–525 nm, respectively [24]. In 2a–2c, the longest wavelength absorption (λ max) is longer (719–762 nm) than that of PS1 (702 nm), while λ max of 2d–2e is the same with that of PS1 (Table 1). Among the conjugates, 2b showed the longest wavelength absorption at 762 nm. In 2a–2b, the Soret band at about 330–450 nm was broadened, indicating the formation of stacking structure of the chlorin ring on the gold surfaces [25].

Table 1.

Absorption properties of PS1 and the PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e.

| Compound | Absorption λ max (nm) (log ε) | |

|---|---|---|

| Soret | Qy | |

| 1 | 435 (0.64) | 702 (0.67) |

| 2a | 440 (0.34) | 724 (0.28) |

| 2b | 434 (0.69) | 762 (0.77) |

| 2c | 435 (0.62) | 719 (0.34) |

| 2d | 434 (0.69) | 702 (0.50) |

| 2e | 434 (0.69) | 702 (0.44) |

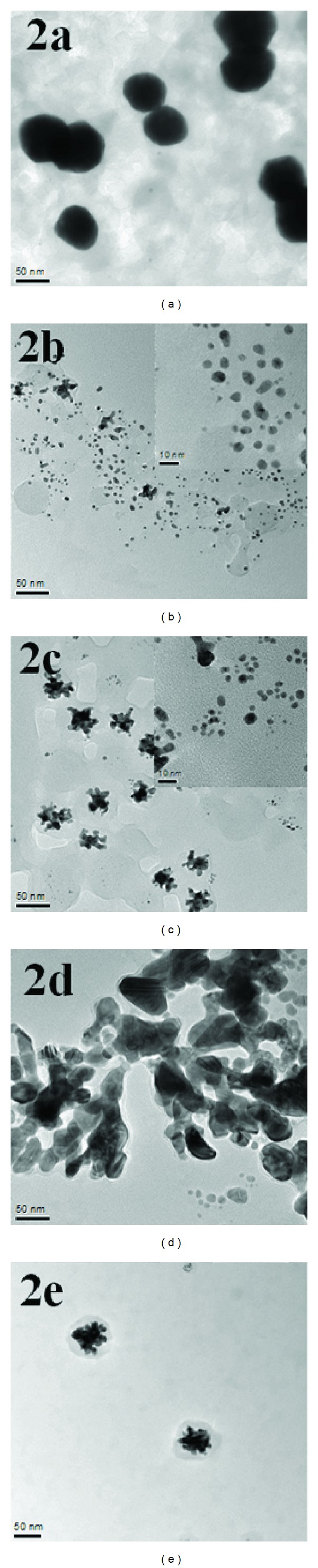

Figure 4 shows the typical TEM images of the PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e prepared by using different concentration ratios between Au(III) and PS1. The images of the conjugates are different from each other in size and shape corresponding to the different molar ratios used in the preparation of the conjugates (Table 2). In 2a, when molar ratio was 1 : 2 for Au(III) : PS1, the GNPs are mainly peanut-shaped nanocrystals in water. And some spheres have diameters around 60 nm and are well dispersed with no aggregation between the GNPs in water. In 2b, when molar ratio was 1 : 4, the GNPs are nanospheres have diameters around 5–11 nm. And some GNPs are closely placed each other and have a chain-like appearance with branching. In 2c, when molar ratio was 1 : 6, the GNPs are nanospheres have diameters around 5–10 nm. However, some GNPs are aggregated together to form many bundles of GNPs, resulting in bigger diameters around 27–44 nm. In 2d, when molar ratio was 1 : 8, the GNPs are mainly aggregated bundles and shape was not spheres with length around 50–90 nm and width around 25–50 nm. And yield of the GNPs was low and some aggregated GNPs have size around 200 nm. In 2e, when molar ratio was 1 : 10, the GNPs are mainly aggregated and yield of the GNPs was very low, and some aggregated bundles of GNPs were around 50–70 nm size. When relatively lower molar ratio of PS1 (2 or 4) made stable GNPs conjugate, however, higher molar ratio allowed unstable GNPs conjugate and remains continuous aggregation [35]. Consequently, the molar ratio between Au(III) and PS1 is an important driving force to control GNPs size, shape, and aggregation degree of the GNPs in aqueous media.

Figure 4.

TEM images of the PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e. The scale bars are 50 nm and the inset scale bars are 10 nm.

Table 2.

Summary of TEM images of the PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e.

| Compound | Shape | Diameter (nm) | Dispersion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | Sphere, peanut | ∼60 | GNPs are well dispersed and showed no aggregation. |

| 2b | Sphere, chain-like appearance with branching | 5–11 | GNPs are well dispersed and showed no aggregation. |

| 2c | Sphere | 5–11 | Some aggregated GNPs have diameter sizes of 27–44 nm. |

| 2d | Not sphere | — | GNPs have a lot of aggregation. |

| 2e | Not sphere | — | Very few aggregated GNPs have sizes of 50–70 nm. |

Based on the UV-vis spectra and TEM images, there is a good relationship between absorption intensity and particle size. Higher absorption intensity of the conjugate corresponds to bigger particle size. In 2a, absorption intensity at over than 450 nm ranges is the highest among all the conjugates, which corresponds to the biggest size (about 60 nm) in the conjugates.

Compound 2b shows the longest wavelength absorption at 762 nm which is included in NIR wavelength region (PTT therapeutic window, 750–1100 nm), so there is a potential for using PTT. We are considering that the GNPs conjugate for a combination (synergy effect) therapy of PDT and PTT [38, 39].

3.3. Photodynamic Activity and Size Effect by In Vitro

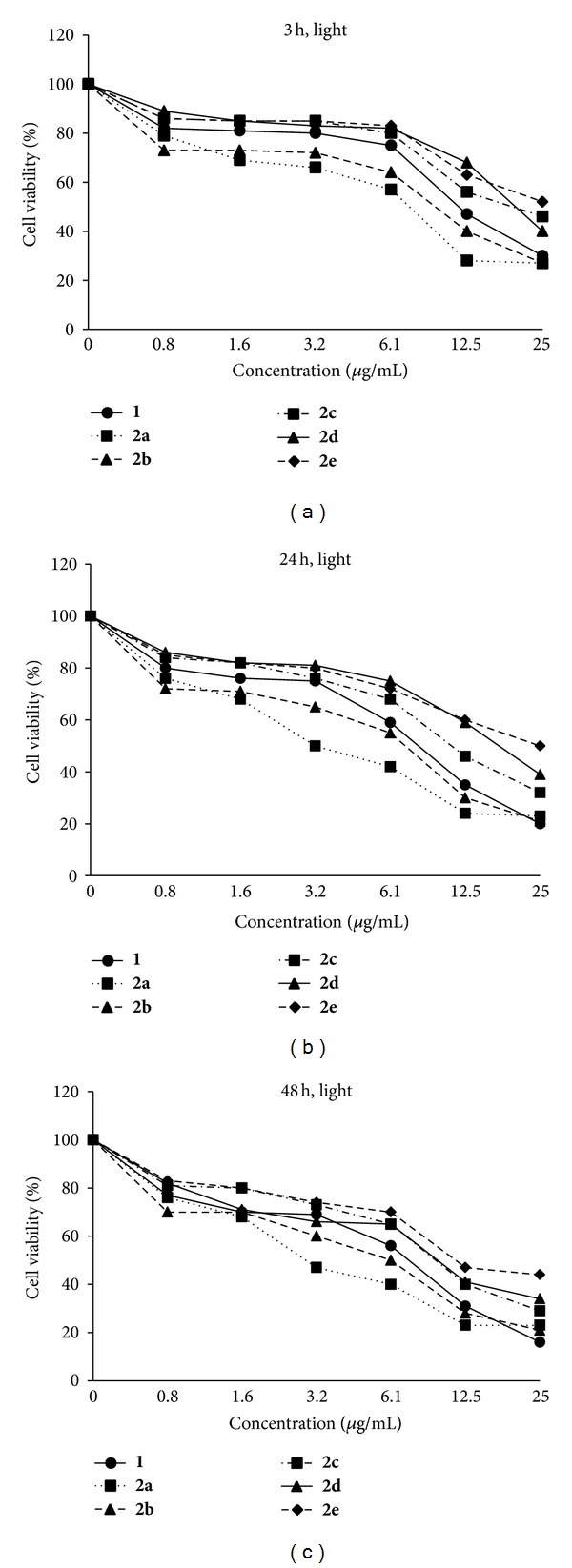

In vitro activity of the GNPs conjugates was evaluated by comparison with PS1 against A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells at 0.8, 1.6, 3.2, 6.1, 12.5, and 25 μg/mL. In this case, PS1 was dissolved in a mixed solvent of ethanol and water (1 : 1 volume ratio) and conjugates 2a–2e were resuspended in water. The dark cytotoxicity and phototoxicity of 2a–2e and PS1 were measured by MTT assay at 3 h, 24 h, and 48 h incubation times, respectively.

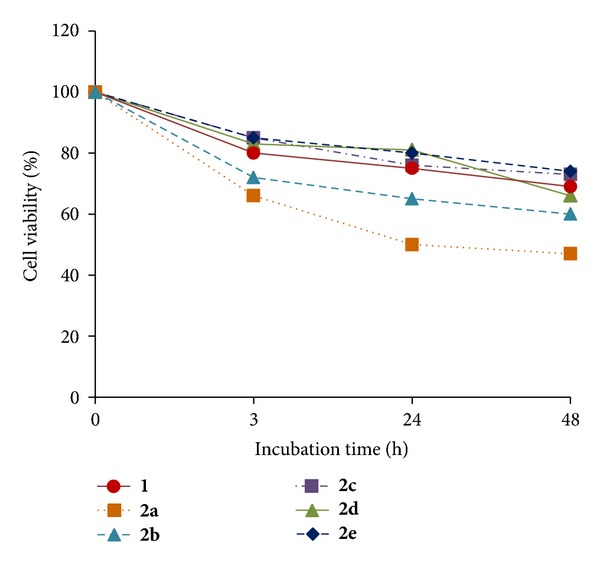

In all the compounds, upon photo irradiation, the cell viability was decreased corresponding to the increased incubation time after PDT as well as increased concentration (Figure 5), for example, at 48 h incubation and 3.2 μg/mL, 80% at 3 h, 75% at 24 h, and 69% for PS1, and 66% at 3 h, 50% at 24 h, and 47% for 2a (Figure 6), respectively.

Figure 5.

Cell viability (%) of PS1 (0–25 μg/mL) and the PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e against A549 cells by exposure to an irradiation after 3 h, 24 h, and 48 h incubation times at 670–710 nm (2 J·cm−2) for 15 min.

Figure 6.

Comparative cell viability (%) of PS1 (3.2 μg/mL) and the PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e against A549 cells by photo irradiation after 3 h, 24 h, and 48 h incubation times.

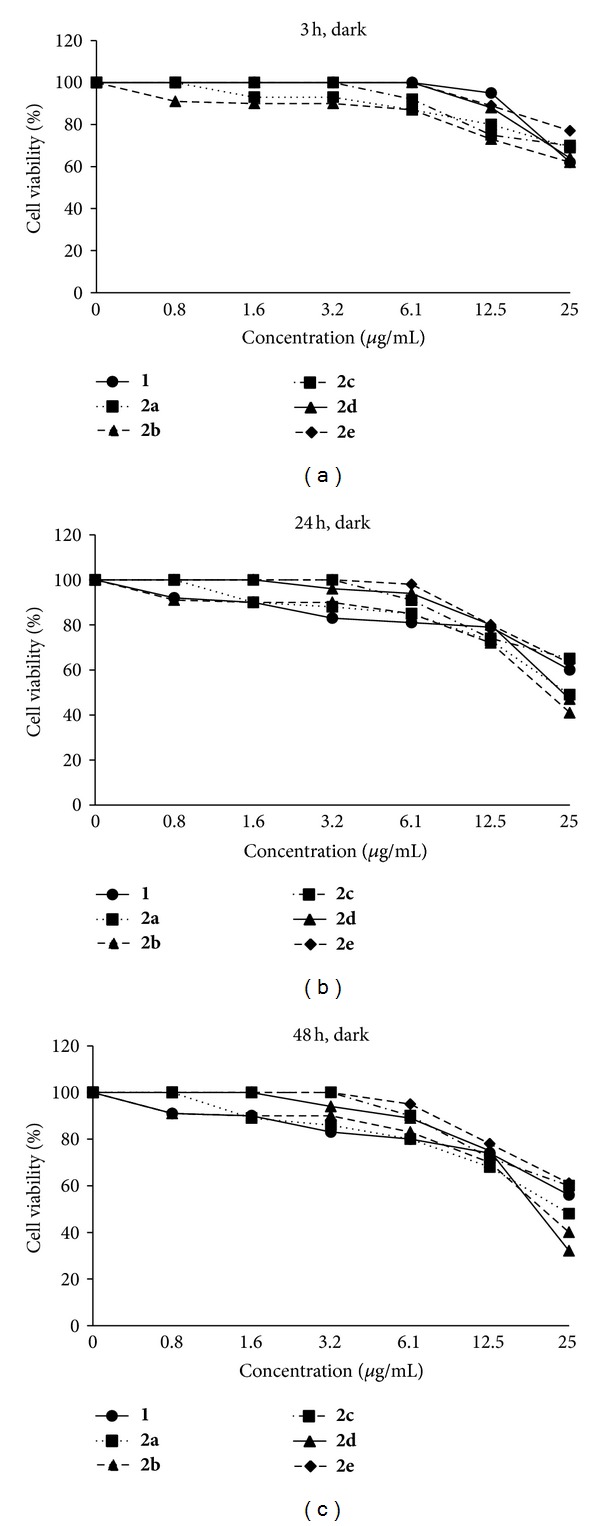

Dark cytotoxicity of PS1 and conjugates 2a–2e is shown in Figure 7. At highest concentration (25 μg/mL) with 48 h incubation time, all compounds showed high dark cytotoxicity (cell viability 32–61%).

Figure 7.

Cell viability (%) of PS1 (0–25 μg/mL) and the PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e against A549 cells without photo irradiation (dark cytotoxicity) after 3 h, 24 h, and 48 h incubation times.

PS1 showed slightly higher photocytotoxicity (IC50, 10.5 μg/mL = 14 μM at 24 h incubation time) than that of the purpurin-18-choline derivative (IC50, 15 μM at 24 h incubation time) that has been previously reported by us [25]. Conjugates 2a and 2b showed higher photocytotoxicity than that of PS1. At high concentration (e.g., at 25 μg/mL), 2a showed higher dark cytotoxicity (69% at 3 h, 49% at 24 h, and 48% at 48 h incubation time, Figure 7) as compared to PS1 (62% at 3 h, 60% at 24 h, and 56% at 48 h incubation time), which might be attributed to large amount of PS1 molecules on the GNPs surface in 2a. However, conjugates 2c–2e showed lower photocytotoxicity than that of PS1. This result demonstrates that photodynamic activity significantly depends on size and aggregation degree of the GNPs. For example, in 2a and 2b there is no aggregation between each other and 2a has about 60 nm size, while in 2c–2e there are some aggregated bundles of the GNPs with small size. Chithrani et al. [29] studied a relationship between particles size (14–100 nm) and cellular uptake of the GNPs in HeLa cells, in which the maximum uptake was occurred at a size of 50 nm. Jiang et al. [28] have reported that cellular uptake strongly depends on the size of the GNPs, in which the GNPs having 2–100 nm size range were coated with Herceptin and were evaluated for cell internalization against breast cancer cell lines by the ErbB2 receptor. The most efficient cellular uptake was observed with particles range of 20–50 nm. Apoptosis was also enhanced by the GNPs having 40–50 nm size [28]. From the high dark cytotoxicity at high concentration, we confirmed that the PS-GNPs conjugate 2a and 2b showed better photodynamic activity at low concentration (3.2 μg/mL) having low dark cytotoxicity (Figure 7).

In addition, 2a and 2b have higher absorbance at irradiated wavelength range, which allowed good photodynamic activity results. In 2c–2e, absorption intensity was lower than that of PS1, resulting in lower photocytotoxicity as compared to PS1. Table 3 shows the IC50 values for PS1 and its PS-GNPs conjugates 2a–2e. At 48 h incubation time, 2a and 2b showed better IC50 value, 4.32 and 6.38 μg/mL, respectively, as compared to PS1 (8.72 μg/mL). Therefore, as we pointed out above, photodynamic in vitro activity of synthesized PS-GNPs conjugates (2a and 2b) is much higher than that of the free PS1. This result indicates that optimal size and well-dispersed nanoparticles are important for photodynamic effect in aqueous media. Especially, bigger size (~60 nm) of nanoparticles 2a could be useful to transport more chlorine molecules into the cancer cells by endocytosis [28, 29, 40].

Table 3.

IC50 (μg/mL) values of PS1 and 2a–2e against A549 cells at various incubation times. IC50 values were determined by MTT assay at 3 h, 24 h and 48 h incubation after photo irradiation.

| Compound | 3 h | 24 h | 48 h |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14.8 | 10.5 | 8.72 |

| 2a | 7.14 | 5.32 | 4.32 |

| 2b | 12.06 | 7.24 | 6.38 |

| 2c | 20.53 | 14.43 | 13.05 |

| 2d | 20.52 | 18.51 | 12.95 |

| 2e | 24.23 | 22.12 | 11.82 |

4. Conclusions

In summary, a simple single-step synthesis of PS-GNPs conjugates from different molar ratios of Au(III)/water soluble ionic PS1 (purpurin-18-N-methyl-D-glucamine) has been studied without adding any particular reducing agents and surfactants. In vitro anticancer efficacy of the PS-GNPs conjugates against A549 lung cancer cell lines was evaluated. We revealed that PDT in vitro activity of synthesized PS-GNPs conjugates was higher as compared to free PS1 because of good transport of the PS into the cells by using size effect. Conjugate 2a based on molar ratio between HAuCl4 and PS was 1 : 2 that exhibits best PDT efficiency than other conjugates having different molar ratios. This result could be useful for synthesis of new PS and PS-GNPs conjugates having different size as well as for developing good relationship between PDT activity and size effect of GNPs in aqueous media.

Conflict of Interests

We do not have any conflict of interests to Sigma-Aldrich and BioSpec LED.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the BK21 Project and the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea. The grant funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2011-0007082 and NRF-2009-353-C00055).

References

- 1.Pandey RK, Goswami LN, Chen Y, et al. Nature: a rich source for developing multifunctional agents. Tumor-imaging and photodynamic therapy. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2006;38(5):445–467. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnet R. Chemical Aspects of Photodynamic Therapy. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandey RK, Zheng G Kadish. The Porphyrin Handbook. Vol. 6. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 2000. In porphyrins as photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy; pp. 157–230. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang S, Gao R, Zhou F, Selke M. Nanomaterials and singlet oxygen photosensitizers: potential applications in photodynamic therapy. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2004;14(4):487–493. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paciotti GF, Kingston DGI, Tamarkin L. Colloidal gold nanoparticles: a novel nanoparticle platform for developing multifunctional tumor-targeted drug delivery vectors. Drug Development Research. 2006;67(1):47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khaing Oo MK, Yang X, Du H, Wang H. 5-aminolevulinic acid-conjugated gold nanoparticles for photodynamic therapy of cancer. Nanomedicine. 2008;3(6):777–786. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.6.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olivo M, Bhuvaneswari R, Lucky SS, Dendukuri N, Thong PS-P. Targeted therapy of cancer using photodynamic therapy in combination with multi-faceted anti-tumor modalities. Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3(5):1507–1529. doi: 10.3390/ph3051507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pissuwan D, Niidome T, Cortie MB. The forthcoming applications of gold nanoparticles in drug and gene delivery systems. Journal of Controlled Release. 2011;149(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pegaz B, Debefve E, Borle F, et al. Preclinical evaluation of a novel water-soluble Chlorin e6 derivative (BLC 1010) as photosensitizer for the closure of the neovessels. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2005;81(6):1505–1510. doi: 10.1562/2005-02-23-RA-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sengee G-I, Badraa N, Shim YK. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new imidazolium and piperazinium salts of pyropheophorbide-a for photodynamic cancer therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2008;9(8):1407–1415. doi: 10.3390/ijms9081407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss WSL, Sailer R, Schneckenburger H, et al. Photodynamic efficacy of naturally occurring porphyrins in endothelial cells in vitro and microvasculature in vivo. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B. 1997;39(2):176–184. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(97)00002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang S, Gao R, Zhou F, Selke M. Nanomaterials and singlet oxygen photosensitizers: potential applications in photodynamic therapy. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2004;14(4):487–493. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Bai J, Li Y, Huang Y. Multifunctional nanoparticles displaying magnetization and near-IR absorption. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2008;47(13):2439–2442. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jelveh S, Chithrani DB. Gold nanostructures as a platform for combinational therapy in future cancer therapeutics. Cancers. 2011;3(1):1081–1110. doi: 10.3390/cancers3011081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Research. 1986;46(12, part 1):6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torchilin VP. Multifunctional nanocarriers. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2006;58(14):1532–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasey PA, Kaye SB, Morrison R, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of PK1 [N-(2- hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymer doxorubicin]: first member of a new class of chemotherapeutic agents—drug-polymer conjugates. Clinical Cancer Research. 1999;5(1):83–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain PK, Huang X, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. Noble metals on the nanoscale: optical and photothermal properties and some applications in imaging, sensing, biology, and medicine. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2008;41(12):1578–1586. doi: 10.1021/ar7002804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang X, El-Sayed IH, Qian W, El-Sayed MA. Cancer cell imaging and photothermal therapy in the near-infrared region by using gold nanorods. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128(6):2115–2120. doi: 10.1021/ja057254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J, Park S, Lee JE, et al. Designed fabrication of multifunctional magnetic gold nanoshells and their application to magnetic resonance imaging and photothermal therapy. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2006;45(46):7754–7758. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nam J, Won N, Jin H, Chung H, Kim S. pH-induced aggregation of gold nanoparticles for photothermal cancer therapy. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131(38):13639–13645. doi: 10.1021/ja902062j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wieder ME, Hone DC, Cook MJ, Handsley MM, Gavrilovic J, Russell DA. Intracellular photodynamic therapy with photosensitizer-nanoparticle conjugates: cancer therapy using a ’Trojan horse’. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. 2006;5(8):727–734. doi: 10.1039/b602830f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narband N, Tubby S, Parkin IP, et al. Gold nanoparticles enhance the toluidine blue-induced lethal photosensitisation of Staphylococcus aureus. Current Nanoscience. 2008;4(4):409–414. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng Y, Samia AC, Meyers JD, Panagopoulos I, Fei B, Burda C. Highly efficient drug delivery with gold nanoparticle vectors for in vivo photodynamic therapy of cancer. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130(32):10643–10647. doi: 10.1021/ja801631c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demberelnyamba D, Ariunaa M, Shim YK. Newly synthesized water soluble Cholinium-Purpurin photosensitizers and their stabilized gold nanoparticles as promising anticancer agents. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2008;9(5):864–871. doi: 10.3390/ijms9050864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gamaleia NF, Shishko ED, Dolinsky GA, Shcherbakov AB, Usatenko AV, Kholin VV. Photodynamic activity of hematoporphyrin conjugates with gold nanoparticles: experiments in vitro. Experimental Oncology. 2010;32(1):44–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, Atwater M, Wang J, Huo Q. Extinction coefficient of gold nanoparticles with different sizes and different capping ligands. Colloids and Surfaces B. 2007;58(1):3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang W, Kim BYS, Rutka JT, Chan WCW. Nanoparticle-mediated cellular response is size-dependent. Nature Nanotechnology. 2008;3(3):145–150. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chithrani BD, Ghazani AA, Chan WCW. Determining the size and shape dependence of gold nanoparticle uptake into mammalian cells. Nano Letters. 2006;6(4):662–668. doi: 10.1021/nl052396o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma X, Wu Y, Jin S, et al. Gold nanoparticles induce autophagosome accumulation through size-dependent nanoparticle uptake and lysosome impairment. ACS Nano. 2011;5(11):8629–8639. doi: 10.1021/nn202155y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shan Y, Ma S, Nie L, et al. Size-dependent endocytosis of single gold nanoparticles. Chemical Communications. 2011;47(28):8091–8093. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11453k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lkhagvadulam B, Kim JH, Yoon I, Shim YK. Synthesis and photodynamic activities of novel water soluble purpurin-18-N-methyl-D-glucamine photosensitizer and its gold nanoparticles conjugate. Journal of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines. 2012;16(4):331–340. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith KM, Goff DA, Simpson DJ. The meso substitution of chlorophyll derivatives: direct route for transformation of bacteriopheophorbides d into bacteriopheophorbides c. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1985;107(17):4946–4954. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng G, Potter WR, Camacho SH, et al. Synthesis, photophysical properties, tumor uptake, and preliminary in vivo photosensitizing efficacy of a homologous series of 3-(1′-alkyloxy)-ethyl-3-devinylpurpurin-18-N-alkylimides with variable lipophilicity. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2001;44(10):1540–1559. doi: 10.1021/jm0005510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim T, Lee K, Gong M-S, Joo S-W. Control of gold nanoparticle aggregates by manipulation of interparticle interaction. Langmuir. 2005;21(21):9524–9528. doi: 10.1021/la0504560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Y-H, Tsai C-Y, Huang P-Y, et al. Methotrexate conjugated to gold nanoparticles inhibits tumor growth in a syngeneic lung tumor model. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2007;4(5):713–722. doi: 10.1021/mp060132k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng Y, Meyers JD, Broome A-M, Kenney ME, Basilion JP, Burda C. Deep penetration of a PDT drug into tumors by noncovalent drug-gold nanoparticle conjugates. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133(8):2583–2591. doi: 10.1021/ja108846h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kah JCY, Wan RCY, Wong KY, Mhaisalkar S, Sheppard CJR, Olivo M. Combinatorial treatment of photothermal therapy using gold nanoshells with conventional photodynamic therapy to improve treatment efficacy: an in vitro study. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2008;40(8):584–589. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuo W-S, Chang C-N, Chang Y-T, et al. Gold nanorods in photodynamic therapy, as hyperthermia agents, and in near-infrared optical imaging. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2010;49(15):2711–2715. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang X-M, Wang L-M, Chen C-Y. Cellular uptake, intracellular trafficking and biological responses of gold nanoparticles. Journal of the Chinese Chemical Society. 2011;58(3):273–281. [Google Scholar]