Abstract

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a severe psychiatric disorder associated with many different risk factors, both genetic and environmental. A recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) of Han Chinese identified three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs rs11038167, rs11038172, and rs835784) in the tetraspanins gene TSPAN18 as possible susceptibility loci for schizophrenia. Hoping to validate these findings, we conducted a case-control study of Han Chinese with 1093 schizophrenia cases and 1022 healthy controls. Using the LDR-PCR method to genotype polymorphisms in TSPAN18, we found no significant differences (P>0.05) between patients and controls in either the allele or genotype frequency of the SNPs rs11038167 and rs11038172. We did find, however, that the frequency of the ‘A’ allele of SNP rs835784 is significantly higher in patients than in controls. We further observed a significant association (OR = 1.197, 95%CI = 1.047–1.369) between risk for SCZ and this ‘A’ allele. These results confirm the significant association, in Han Chinese populations, of increased SCZ risk and the variant of the TSPAN18 gene containing the ‘A’ allele of SNP rs835784.

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SCZ) – a severe and heritable psychiatric disorder characterized by positive and negative symptoms, some of which are cognitive – affects ∼1% of the general population worldwide. While the heritability of schizophrenia has been estimated to be ∼64–80% [1], [2], its precise etiology and genetic mechanisms remain unclear. One genome-wide association study (GWAS) associates susceptibility for SCZ with several common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and rare copy-number variants (CNVs). To date, however, these suspected susceptibility loci have been studied primarily in populations of European and American descent [3], [4], [5], [6], [7].

Interestingly, a recent GWAS study of Han Chinese associated increased susceptibility for SCZ with three SNPs (rs11038167, rs11038172 and rs835784) within the tetraspanins gene TSPAN18 [8]. TSPAN18 at 11p11.2 encodes one member of a large family of membrane proteins found in all multicellular eukaryotes with four transmembrane (tetraspanin) domains. Expressed widely and in diverse cell types, the tetraspanins appear to affect cellular penetration, adhesion, motility, and signal conduction [9], [10], [11]. Although TSPAN18′s role in the pathogenesis of SCZ remains unclear, the tetraspanin family's association with both bipolar disorder and SCZ [8], [12] suggests it may well be involved in increasing susceptibility for SCZ. In an attempt to confirm such a role, this study aims to investigate the association of SCZ with three SNPs in the TSPAN18 gene in an independent population of Han Chinese descent.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Our study sample, which includes subjects of Han descent, includes 1093 patients (396 women and 697 men aged 47.9±10.9 years at recruitment) and 1022 unrelated healthy controls (450 women and 572 men aged 44.8±10.2 years at recruitment) (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of study subjects.

| Group | Case n (%) | Control n (%) |

| Sex | ||

| Total | 1093 | 1022 |

| Female | 396 (0.36) | 450 (0.41) |

| Male | 697 (0.64) | 572 (0.52) |

| Age | ||

| Range | 16–75 | 18–77 |

| Mean | 47.9±10.9 | 44.8±10.2 |

| 10–19 | 5 (0.00) | 2 (0.00) |

| 20–29 | 71 (0.06) | 93 (0.09) |

| 30–39 | 139 (0.13) | 175 (0.16) |

| 40–49 | 371 (0.34) | 420 (0.38) |

| 50–59 | 352 (0.32) | 256 (0.23) |

| 60–69 | 145 (0.13) | 70 (0.06) |

| 70–79 | 10 (0.01) | 6 (0.01) |

In the patient sample, the diagnosis of schizophrenia was confirmed by two or more experienced psychiatrists using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I) and criteria set forth in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition (DSM-IV). Exclusion criteria included the presence of other mood or neurodevelopmental disorders, epilepsy, or mental retardation. For the selection of controls, professional psychiatrists, using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Non-patients edition (SCID-NP), interviewed members of an unrelated general population. Subjects with mental illness within the SCID-I Axis I were excluded.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Wuxi Health Mental Center. Either patients or their guardians signed informed consents. Where ability to consent appeared compromised, we used the following criteria to evaluate whether the participants had the capacity to consent: 1) patient's ability to understand; 2) patient's ability to reason; and 3) patient's ability to make rational decisions. If participants failed to fill out the consent form more than twice, their guardians were asked to fill out the consent form on the patients' behalf.

Healthy subjects were recruited through advertisement. We recruited controls from the cities of WuXi and NanJing in Jiangsu Province. Based on self-report regarding their own and their paternal grandparents' place of birth, we excluded anyone not born in Jiangsu or whose family was not born in Jiangsu. Before being enrolled in the study, each healthy subject was required to sign a consent form.

DNA extraction

Blood samples were collected from all participants using K2EDTA tubes. A Blood Genotyping DNA Extraction Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) was used to extract genomic DNA from 150 μl of peripheral blood. DNA samples were then stored at −80°C for genotype analysis.

SNP genotyping

The genotype of each SNP was analyzed by the Shanghai Biowing Applied Biotechnology Co., Ltd (www.biowing.com.cn) using the Ligase Detection Reaction-Polymerase Chain Reaction (LDR-PCR) method [13], [14]. Genomic DNA extracted from clinical samples was first subjected to multiplex RCR to obtain a PCR product, including SNPs. This PCR product and LDR probes were then subjected to multiplex LDR reaction with a DNA sequencer to detect the products. To test the validity of this procedure, approximately 10% of the samples was randomly selected and retested using the same process. Results from the retested 10% were consistent with those obtained from the larger sample.

Statistical analysis

Our statistical analyses, performed using PLINK software (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink), included association studies, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) tests, and the calculation of genotype and allele frequencies in schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. We also used a logistic regression model adjusted for age and sex to evaluate how these factors influence the distribution of TSPAN18 polymorphisms. Frequency comparisons among different ethnic groups were conducted based on variation data from dbSNP build 135, which includes data from the HapMap and 1000-Genome projects.

Results

This study analyzes data from 1093 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and 1022 unrelated healthy controls. Our HWE tests indicate that the allelic frequency distribution of TSPAN18 polymorphisms does not deviate significantly from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P = 0.1688 for rs11038167, 0.3681 for rs11038172, and 0.2972 for rs835784). The total genotyping rate in all individuals was 99.57%.

Results from our association study indicate a significant association (trend test: P = 0.004967; χ2 test under dominant model: P = 0.008812) between SCZ and the minor allele (‘A’) of the TSPAN18 gene SNP rs835784. Stratified analysis by sex and age supports this association, with the χ2 test showing P = 0.01374 in males and P = 0.00339 in subjects of middle age (30–59 years). In this Chinese Han population, therefore, the minor allele ‘A’ of rs835784 appears to be a risk factor for SCZ (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2. Association study of three SNPs in TSPAN18 under different models.

| Case | Control | ||||

| Test Model: SNP(A1/A2)† | n | Freq.§ | n | Freq.§ | P * |

| rs11038167 (A; C) | |||||

| Trend: A/C | 877/1307 | 0.40 | 806/1234 | 0.40 | 0.6774 |

| Allelic: A/C | 877/1307 | 0.40 | 806/1234 | 0.40 | 0.6683 |

| Dominant: (AA+AC)/CC | 681/411 | 0.62 | 636/384 | 0.62 | 0.9963 |

| Recessive: AA/(AC+CC) | 196/896 | 0.18 | 170/850 | 0.17 | 0.4367 |

| rs11038172 (A; G) | |||||

| Trend: A/G | 965/1207 | 0.44 | 862/1158 | 0.43 | 0.2587 |

| Allelic: A/G | 965/1207 | 0.44 | 862/1158 | 0.43 | 0.252 |

| Dominant: (AA+AG)/GG | 743/343 | 0.68 | 671/339 | 0.66 | 0.3335 |

| Recessive: AA/(AG+GG) | 222/864 | 0.20 | 191/819 | 0.19 | 0.3786 |

| rs835784 (A;G) | |||||

| Trend: A/G | 667/1513 | 0.31 | 543/1497 | 0.27 | 0.004967 |

| Allelic: A/G | 667/1513 | 0.31 | 543/1497 | 0.27 | 0.00429 |

| Dominant: (AA+AG)/GG | 558/532 | 0.51 | 464/556 | 0.45 | 0.008812 |

| Recessive: AA/(AG+GG) | 109/981 | 0.10 | 79/941 | 0.08 | 0.06924 |

A1/A2, indicates minor allele/major allele.

The minor allele frequency for allelic and trend model, “DD + Dd” frequency for dominant model, and “DD” for recessive model, where “D” indicates minor allele, “d” indicates the major allele.

Cochran-Armitage trend test p-value; for Allelic/Dominant/Recessive models, asymptotic p-values were calculated by Chi-Squared test.

Table 3. llele frequency distribution by sex and age group for three SNPs in TSPAN18.

| Case | Control | ||||||

| Group | SNP | A1/A2† | n | Freq. § | n | Freq. § | P* |

| Male | |||||||

| rs11038167 | A/C | 554/838 | 0.40 | 429/713 | 0.38 | 0.2725 | |

| rs11038172 | A/G | 613/769 | 0.44 | 467/673 | 0.41 | 0.09324 | |

| rs835784 | A/G | 420/968 | 0.30 | 293/849 | 0.26 | 0.01374 | |

| Female | |||||||

| rs11038167 | A/C | 323/469 | 0.41 | 377/521 | 0.42 | 0.6192 | |

| rs11038172 | A/G | 352/438 | 0.45 | 395/485 | 0.45 | 0.893 | |

| rs835784 | A/G | 247/545 | 0.31 | 250/648 | 0.28 | 0.1251 | |

| Younger (−29) | |||||||

| rs11038167 | A/C | 53/99 | 0.35 | 91/99 | 0.48 | 0.02013 | |

| rs11038172 | A/G | 58/94 | 0.38 | 97/93 | 0.51 | 0.02125 | |

| rs835784 | A/G | 39/113 | 0.26 | 61/129 | 0.32 | 0.2074 | |

| Middle-aged (30–59) | |||||||

| rs11038167 | A/C | 678/1044 | 0.39 | 657/1041 | 0.39 | 0.6924 | |

| rs11038172 | A/G | 756/960 | 0.44 | 703/977 | 0.42 | 0.1983 | |

| rs835784 | A/G | 523/1201 | 0.30 | 438/1262 | 0.26 | 0.00339 | |

| Elderly (60-) | |||||||

| rs11038167 | A/C | 146/164 | 0.47 | 58/94 | 0.38 | 0.07142 | |

| rs11038172 | A/G | 151/153 | 0.50 | 62/88 | 0.41 | 0.09996 | |

| rs835784 | A/G | 105/199 | 0.35 | 44/106 | 0.29 | 0.2691 | |

A1/A2, indicates minor allele/major allele.

The minor allele frequency.

Cochran-Armitage trend test p-values for minor allele.

Using logistic regression models to estimate the effect size of the risk allele, we calculated that, before adjustment for age and sex, the OR for increased risk for SCZ with the rs835784 ‘A’ allele is 1.197 (95%CI = 1.047–1.369), P = 0.008426. Once adjusted for age and sex, the risk is nearly the same, OR = 1.194 (95%CI = 1.033–1.381, P = 0.0165), confirming that the ‘A’ allele of rs835784 is consistently associated with an increase in risk for SCZ (Table 4).

Table 4. Risk estimates using logistic regression model for three SNPs in TSPAN18.

| All (n = 2,115) | All (n = 2,115) | Matched† (n = 1,804) | |||||

| SNP | Risk Allele | OR (95%CI) | Punadj ζ | OR (95%CI) | P adj * | OR (95%CI) | P adj * |

| rs11038167 | A | 1.026 (0.91–1.156) | 0.6774 | 1.032 (0.9137–1.165) | 0.6147 | 1.04 (0.9118–1.186) | 0.5595 |

| rs11038172 | A | 1.072 (0.9502–1.209) | 0.2588 | 1.071 (0.948–1.21) | 0.2696 | 1.083 (0.9487–1.236) | 0.2384 |

| rs835784 | A | 1.208 (1.059–1.379) | 0.005034 | 1.197 (1.047–1.369) | 0.008426 | 1.194 (1.033–1.381) | 0.0165 |

Sex- and age- (±2 year-old) matched dataset.

P unadj, un-adjusted p-values in the logistic regression model.

P adj, p-values of the risk allele in the logistic regression model, adjusted by sex and age.

By contrast, neither genotypic nor allelic modeling revealed significant association between increased schizophrenia risk and the other two TSPAN18 SNPs, rs11038167 or rs11038172 (Table 2). Although stratified analysis does suggest that the ‘A’ alleles of both rs11038167 (P = 0.02013 in the χ2 test) and rs11038172 (P = 0.02125) may be associated with increased SCZ risk in youth (≤29-year-old) (Table 3), our sample (N = 190) was too small for these results to be reliable, and results adjusted for age and sex fail to support them (Table 4). In addition, we found an inter-marker LD relationship between these two SNPs and rs835784, whose A-allele appears to be associated with SCZ, with r-square = 0.45 for rs835784′s relationship with rs11038167 and r-square = 0.38 for its relationship with rs11038172.

Discussion and Conclusions

The tetraspanins are a highly conserved superfamily of cell-surface membrane proteins known to be influential in diverse diseases and physiologic processes. High expression of TSPAN1, TSPAN8, or TSPAN2, for example, which are all in the same protein family as TSPAN18, correlates positively with tumor progression [15], [16], [17], while mutation in TSPAN7 is associated with X-linked mental retardation [18], [19].

Although earlier reports implicate TSPAN18 in susceptibility for SCZ [8], Ma et al. [20] failed to confirm that association. In this case-control study of Han Chinese, we, too, find no statistically significant association between SCZ and the two TSPAN18 SNPs rs11038167 and rs11038172. Our analyses do reveal a statistically significant difference between patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls: the frequency of the “A” allele of rs835784 occurs at 31% in our SCZ samples and at 27% in controls. This finding confirms Yue et al.'s [8] report that carriers of the A-allele of rs835784 are at 1.197-fold greater risk for SCZ than non-carriers.

It should be noted that this study's subjects were all recruited from Jiangsu province, while Yue et al.'s study sample was drawn from northern China (an area that includes Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei and Shandong), and Ma et al.'s from Hunan province. It is therefore possible that differences in their TSPAN18 polymorphism profiles could reflect regional differences not generalizable to all people of Han descent.

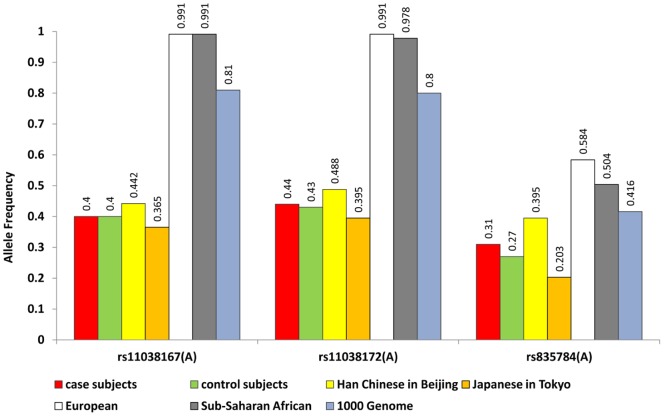

While a more definitive assessment of potential population stratification among Han Chinese subpopulations is not feasible in this study, we were able to compare SNP frequency distribution in different ethnic groups using dbSNP data from HapMap and the 1000-genomes studies. Our allele frequency analysis of these data for the three TSPAN18 SNPs revealed substantial differences among Asian, European, and African populations (Figure 1). To identify precisely how ethnicity and geographic origin affect the distribution of genetic factors associated with schizophrenia, larger replication studies are needed.

Figure 1. Allele frequency distribution among different ethnic groups for the three SNPs in TSPAN18.

To summarize, this case-control study of a Han Chinese population validated a SNP locus in TSPAN18 reported by an earlier GWAS study and provided important evidence for the association of a particular variant of the TSPAN18 gene with increased SCZ susceptibility. Further studies to validate these findings on the molecular level are clearly warranted. Data from this study are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers and the PLOS ONE editor for their insightful and constructive comments. We thanks all study participants. The views expressed in this presentation do not necessarily represent the views of the NIMH, NIH, HHS, or the United States Government.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by a grant from the Key Characteristic Specialty/Discipline of Wuxi Hospital Management Center, from the Research Project of the Wuxi Municipal Health Bureau (Q201208). HDQ and YYS are supported by supported by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed in this presentation do not necessarily represent the views of the NIMH, National Institutes of Health, Health and Human Services, or the United States Government.

References

- 1. Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Bjork C, Pawitan Y, Cannon TD, et al. (2009) Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet 373: 234–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thaker GK, Carpenter WT (2001) Advances in schizophrenia. Nat Med 7: 667–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Donovan MC, Craddock N, Norton N, Williams H, Peirce T, et al. (2008) Identification of loci associated with schizophrenia by genome-wide association and follow-up. Nat Genet 40: 1053–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stefansson H, Ophoff RA, Steinberg S, Andreassen OA, Cichon S, et al. (2009) Common variants conferring risk of schizophrenia. Nature 460: 744–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shi J, Levinson DF, Duan J, Sanders AR, Zheng Y, et al. (2009) Common variants on chromosome 6p22.1 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature 460: 753–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O'Donovan MC, et al. (2009) Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature 460: 748–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vacic V, McCarthy S, Malhotra D, Murray F, Chou HH, et al. (2011) Duplications of the neuropeptide receptor gene VIPR2 confer significant risk for schizophrenia. Nature 471: 499–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yue WH, Wang HF, Sun LD, Tang FL, Liu ZH, et al. (2011) Genome-wide association study identifies a susceptibility locus for schizophrenia in Han Chinese at 11p11.2. Nat Genet 43: 1228–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hemler ME (2003) Tetraspanin proteins mediate cellular penetration, invasion, and fusion events and define a novel type of membrane microdomain. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 19: 397–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tarrant JM, Robb L, van Spriel AB, Wright MD (2003) Tetraspanins: molecular organisers of the leukocyte surface. Trends Immunol 24: 610–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Levy S, Shoham T (2005) The tetraspanin web modulates immune-signalling complexes. Nat Rev Immunol 5: 136–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scholz CJ, Jacob CP, Buttenschon HN, Kittel-Schneider S, Boreatti-Hummer A, et al. (2010) Functional variants of TSPAN8 are associated with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 153B: 967–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O’Donovan MC, Craddock N, Norton N, Williams H, Peirce T, et al. (2008) Identification of loci associated with schizophrenia by genome-wide association and follow up. Nat Genet 40: 1053–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shi Y, Li Z, Xu Q, Wang T, Li T, et al. (2011) Common variants on 8p12 and 1q24.2 confer risk of schizophrenia. Nat Genet 43: 1224–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhou Z, Ran YL, Hu H, Pan J, Li ZF, et al. (2008) TM4SF3 promotes esophageal carcinoma metastasis via upregulating ADAM12m expression. Clin Exp Metastasis 25: 537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang XH, Richardson AL, Torres-Arzayus MI, Zhou P, Sharma C, et al. (2008) CD151 accelerates breast cancer by regulating alpha 6 integrin function, signaling, and molecular organization. Cancer Res 68: 3204–3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scholz CJ, Kurzeder C, Koretz K, Windisch J, Kreienberg R, et al. (2009) Tspan-1 is a tetraspanin preferentially expressed by mucinous and endometrioid subtypes of human ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Lett 275: 198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zemni R, Bienvenu T, Vinet MC, Sefiani A, Carrie A, et al. (2000) A new gene involved in X-linked mental retardation identified by analysis of an X;2 balanced translocation. Nat Genet 24: 167–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maranduba CM, Sa Moreira E, Muller Orabona G, Pavanello RC, Vianna-Morgante AM, et al. (2004) Does the P172H mutation at the TM4SF2 gene cause X-linked mental retardation? Am J Med Genet A 124A: 413–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma L, Tang J, Wang D, Zhang W, Liu W, et al. (2012) Evaluating risk loci for schizophrenia distilled from genome-wide association studies in Han Chinese from central China. Mol Psychiatry 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed]