Abstract

Amyloid accumulation in the brain of Alzheimer’s patients results from altered processing of the 39- to 43-amino acid amyloid β protein (Aβ). The mechanisms for the elevated amyloid (Aβ1–42) are considered to be over-expression of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), enhanced cleavage of APP to Aβ, and decreased clearance of Aβ from the central nervous system (CNS). We report herein studies of Aβ stimulated effects on endothelial cells. We observe an interesting and as yet unprecedented feedback effect involving Aβ1–42 fibril-induced synthesis of APP by Western blot analysis in the endothelial cell line Hep-1. We further observe an increase in the expression of Aβ1–40 by flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy. This phenomenon is reproducible for cultures grown both in the presence and absence of serum. In the former case, flow cytometry reveals that Aβ1–40 accumulation is less pronounced than under serum-free conditions. Immunofluorescence staining further corroborates these observations. Cellular responses to fibrillar Aβ1–42 treatment involving eNOS upregulation and increased autophagy are also reported.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by neuronal degeneration and accumulation of senile plaques, which are composed of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides predominantly consisting of 40 and 42 amino acids [1], [2]. The excessive accumulation of Aβ peptides in AD may be due to enhanced endoproteolytic cleavage of membrane bound amyloid precursor protein (APP), over-expression of APP and/or decreased clearance of Aβ from the central nervous system (CNS) [3]–[5].

Postmortem analyses of AD subjects reveal that amyloid plaques in the brain suffuse vascular cells in addition to the parenchymal. The implications of this vascular infiltration for AD has been less well studied than the parenchymal Aβ, but has generated considerable interest with studies that β-amyloid fibrils accumulate in small arteries, arterioles and capillaries of the brain [6]–[8]. Cerebrovascular amyloid toxicity generally manifests itself in the breach of the blood-brain-barrier and enhanced inflammation in the cerebrovasculature [9], [10].

The mechanism for the onset of pathological vascular changes has yet to be elucidated [11]. Two mechanisms that have been proposed involve: (1) The production of excess superoxide by amyloid-β induced oxidative stress [12], [13] and (2) the formation of amyloid aggregates whose resistance to protease degradation turns them into cellular “tombstones” that impair blood flow and cellular function [14], [15].

The oxidative stress mechanism was used to explain an in vitro investigation where the interaction with Aβ fibrils resulted in the endothelial lining of the rat aorta undergoing rapid damage leading to exposure of smooth muscle cells and connective tissue [16]. In agreement with these observations, it has been shown that antioxidant treatment and superoxide dismutase (SOD) treatment can reduce damage of endothelial cells caused by amyloid-β [17], [18].

The “tombstone” mechanism is consistent with biochemical and biophysical studies of synthetic Aβ peptides indicating that the more toxic Aβ peptides ending at residue 42 aggregate more rapidly than peptides of 39 or 40 amino acids [19]–[22]. This feature of Aβ1–42 makes it less susceptible to proteolytic degradation [23]–[25]. Further support for this mechanism comes from studies on the APP mutation found in HCHWA-Dutch type, which results in the production of Aβ with enhanced tendency to aggregate relative to that of wild type Aβ. Fibril formation in this mutation is limited to the cerebrovasculature and amyloidosis leads to cerebral hemorrhage [26], [27].

APP synthesis and processing to Aβ normally takes place only to a limited extent in endothelial cells [28]. It has, however been shown that amyloids can alter the expression pattern of specific proteins. Thus, the accumulation of Aβ1–42 in lysosomes down regulates the catabolism of APP resulting in enhanced production of amyloidogenic fragments [29]. Production of individual isoforms of Aβ induced by the same isoform has been shown in smooth muscle cells [30]. On the basis of these studies we investigated the possibility that amyloid fibrils can induce synthesis of more APP and amyloid of its other isoforms. Such a process would provide a synergistic mechanism whereby amyloid fibrils in circulation potentiate damage to the blood brain barrier endothelium. For this purpose we used synthetic, preformed Aβ1–42 fibrils and established the resultant accumulation of APP and Aβ1–40.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Media for cell culture was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Synthetic Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42 and monoclonal antibody against Aβ1–40 were purchased from Biosource International (Camarillo, CA). Fluorescein and phycoerythrin labeled streptavidin were purchased from PharMingen (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA.).

Preparation of Amyloid Fibrils

Synthetic Aβ1–42 was disaggregated by pretreatment with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) followed by treatment with trifluoroethanol (TFE) three times to remove traces of TFA. After each step, solvents were evaporated to form a film. Aβ1–42 fibrils were formed from disaggregated Aβ1–42 by following a known procedure [31]. Briefly, Aβ1–42 (250 µM) was dissolved in phosphate buffered saline, (PBS), pH 7.5, and polymerized in Eppendorf tubes (1.5 ml), at 37°C for 2 days. Newly formed fibrils were then separated from monomeric peptides by centrifugation at 4°C for 90 min at 15,000 rpm, using a Sorvall RC-5B centrifuge. The fibril pellet was re-suspended in PBS and used for in vitro studies [31], [32].

Cell Culture and Flow Cytometry

Human endothelial (Hep-1) cell line is a kind gift from Dr. John Kusiak at the National Institute on Aging. This is an immortal human endothelial cell line derived from an adenocarcinoma of the liver [33]. Cells were grown in DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS Prime, Biofluids), 1×MEM non-essential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. 1×106 cells were incubated with varying concentrations of Aβ1–42 fibrils in the presence or absence of FBS for 12 hrs. Cells were then harvested, washed with PBS, fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde, and probed with biotinylated monoclonal antibodies against Aβ1–40. This antibody detects low molecular weight Aβ1–40, but not fibrils. Cells were counter-labeled with 20 µg/ml phycoerythrin-streptavidin for 15 to 30 min. Labeled cells were analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose CA) equipped with a 15 mW argon laser. Phycoerythrin labeled cells were excited with 488 nm light from the argon laser and emitted fluorescence was collected using the FL-2 (585/42) bands pass filter. A total of 20,000 events were analyzed for each sample. The amount of Aβ1–40 present in the endothelial cells was determined by mean fluorescence values. Light scatter signals were also collected in the forward and side scatter detectors. Experiments were repeated three times. The mean and standard error of the mean values were calculated.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Cells grown on glass cover slips were incubated at 37°C for 12 hrs, and then washed with PBS. Cells with and without Aβ treatment were subsequently fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde for 10 min and washed with 100 mM glycine in PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin. After washing, samples were incubated for 1 hr with a biotin-conjugated anti-Aβ1–40 antibody (1∶500 dilution) at room temperature, washed with PBS and stained with FITC-streptavidin conjugate. Immunofluorescence images were captured with an Axiovert S100 microscope (Zeiss, Munich, Germany). Images were recorded at the same exposure time using a digital SPOT camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI).

Western Blotting

Cells were lysed in 300 µl of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, supplemented with 2 mM EGTA, 50 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 10 µg/ml aprotinin, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 5 mM NaF. The resulting lysates were resolved on 4–15% SDS Tris-glycine gels (30 µg/lane) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membranes were blocked in TBST (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) containing 5% non-fat milk and then probed with the following primary antibodies: monoclonal mouse anti-human APP (8E5 Elan Pharmaceuticals; 1∶500 dilution), monoclonal mouse anti-human endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (BD Biosciences; 1∶2500 dilution), monoclonal mouse anti-human nNOS (BD Biosciences; 1∶2500 dilution), rabbit polyclonal anti-caveolin 1 antibody (ab2910 abcam; 1∶2000 dilution) and rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3B antibody (ab48394 abcam; 1∶1000 dilution). Proteins were detected with HRP conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (NEN Life Science, Boston, MA). The blot was quantitated by densitometric analysis and the difference between treated and control groups were analyzed by unpaired t test (tails = 2) using Excel software.

Results

APP Upregulation by Fibrillar Aβ1–42

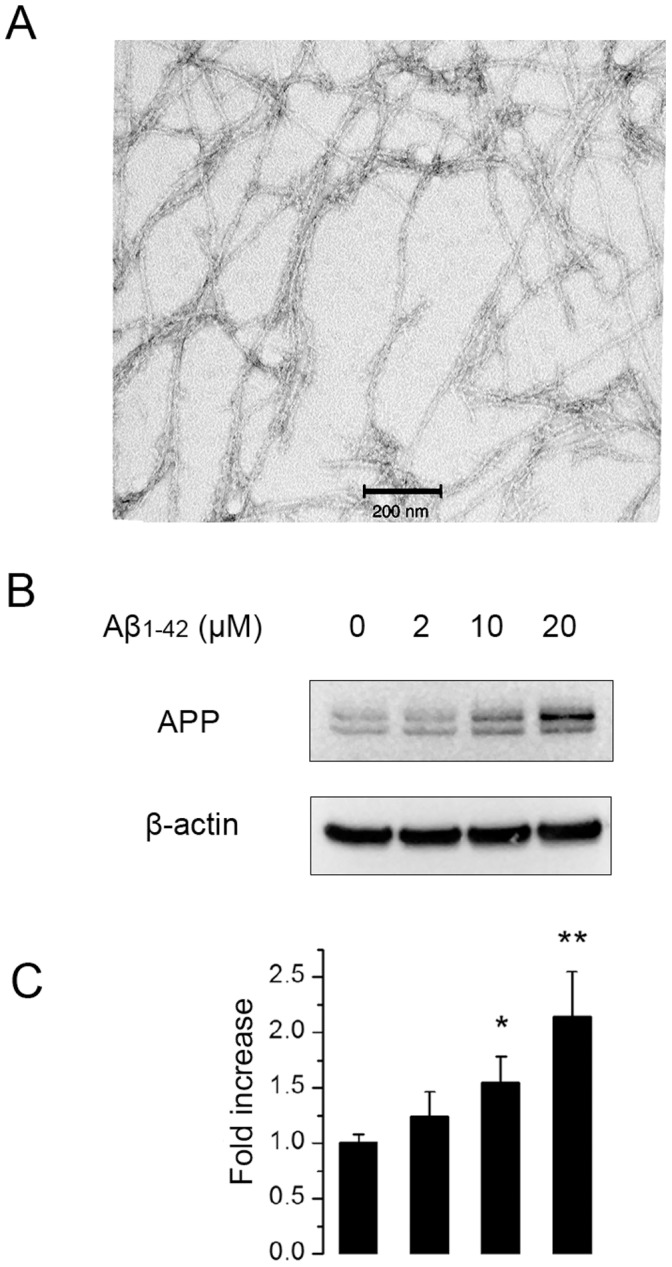

Aβ1–42 fibrils were prepared from synthetic Aβ1–42 peptides and morphologically characterized by TEM (Fig. 1A). Western blotting was used to determine whether Aβ1–42 fibrils can increase synthesis of APP. For this purpose human endothelial cells (Hep-1) were incubated with Aβ1–42 fibrils for 12 hrs and then harvested in a lysis buffer for Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 1B and C, the amount of APP was increased in cells incubated with Aβ1–42 in a dose dependent manner.

Figure 1. Fibrillar Aβ1–42 induced APP upregulation in Hep-1 cells.

Morphology of fibrillar Aβ1–42 was confirmed by TEM (A).Cells were untreated or treated with 2 µM, 10 µM, 20 µM Aβ1–42 for 24 hrs. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using 8E5 antibody (B). The blot was quantitated by densitometric analysis (C). The fold increase of APP production compared to untreated control cells were shown as mean ± SD (n = 4). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01 compared to control.

Aβ1–40 Production in Amyloidic Condition

The association of the increased APP synthesis with an increase in Aβ was investigated in the same cell model. It was possible to discriminate between newly synthesized amyloids and the Aβ1–42 used to treat Hep-1 cells by using antibodies that are specific for Aβ1–40, which only detects low molecular weight Aβ1–40, but not fibrils. The latter sequence accounts for about 90% of newly processed amyloid but no cross reactivity between Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 was observed, in agreement with previous reports [34].

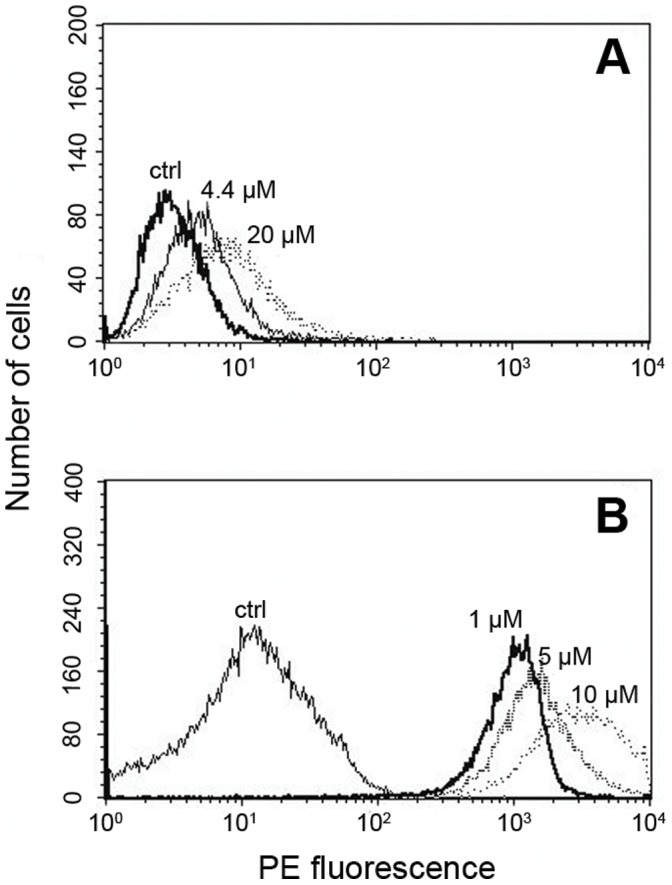

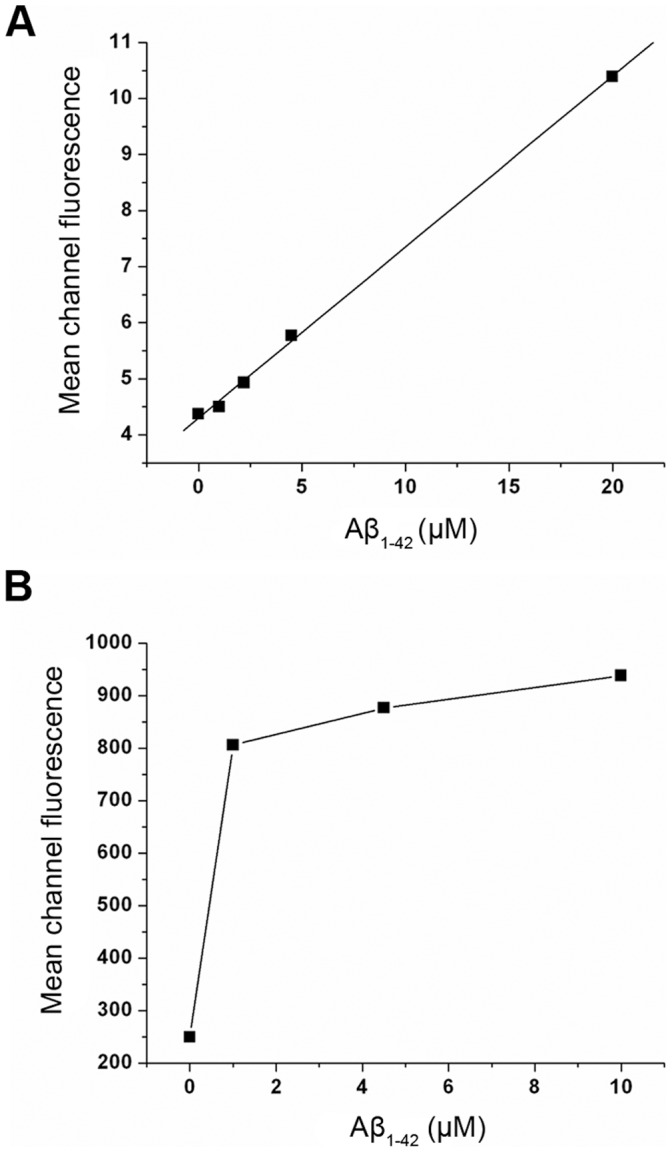

The flow cytometry histograms, of cultures grown with and without FBS (Fig. 2A and B, respectively), show the amyloid-induced accumulation of Aβ1–40, which is further accentuated by the stress associated with the absence of serum. In both cases, it is clear that Aβ1–42 fibrils increase Aβ1–40 synthesis in a concentration dependent manner as shown by the plots of the mean fluorescence in Fig. 3. The concentration dependence further highlights the effect of stress associated with the absence of serum. Thus, in the presence of serum a gradual raise in fluorescence takes place over the range of amyloid concentrations tested (Fig. 3A), while more dramatic changes occur in the absence of serum (Fig. 3B) with the relative fluorescence increasing from 250 to 800 at the lowest concentration tested (1 µM). At higher concentrations only minor additional increases in fluorescence are detected.

Figure 2. Detection of fibrillar Aβ1–42 induced Aβ1–40 production by flow cytometry.

For the analysis of Aβ1–40 synthesis in amyloidic condition, Hep-1 cells were treated with fibrillar Aβ1–42 in the presence (A) or absence (B) of serum, stained with anti Aβ1–40 antibodies (biotinylated) and streptavidin conjugated phycoerythrin. Histograms are shown for the control with no added amyloid (ctrl) and for cells incubated with various concentrations of Aβ1–42.as indicated in the figure.

Figure 3. The mean fluorescence values obtained from the flow cytometry histogram were plotted against incubated Aβ1–42 concentration in the presence of serum (A) and under serum deprived condition (B).

Because the antibody used only detects low molecular weight amyloid, the observed Aβ1–40 cannot be derived from cleavage of added Aβ1–42 fibrils. To confirm that a cleaved fibril cannot be detected, Hep-1 endothelial cells were treated with 20 µM protofibrillar Aβ1–40 (10 hrs aged peptide) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Only a negligible increase in Aβ1–40 was observed and the fluorescence histogram was similar to that of control (data not shown).

Cellular Morphology

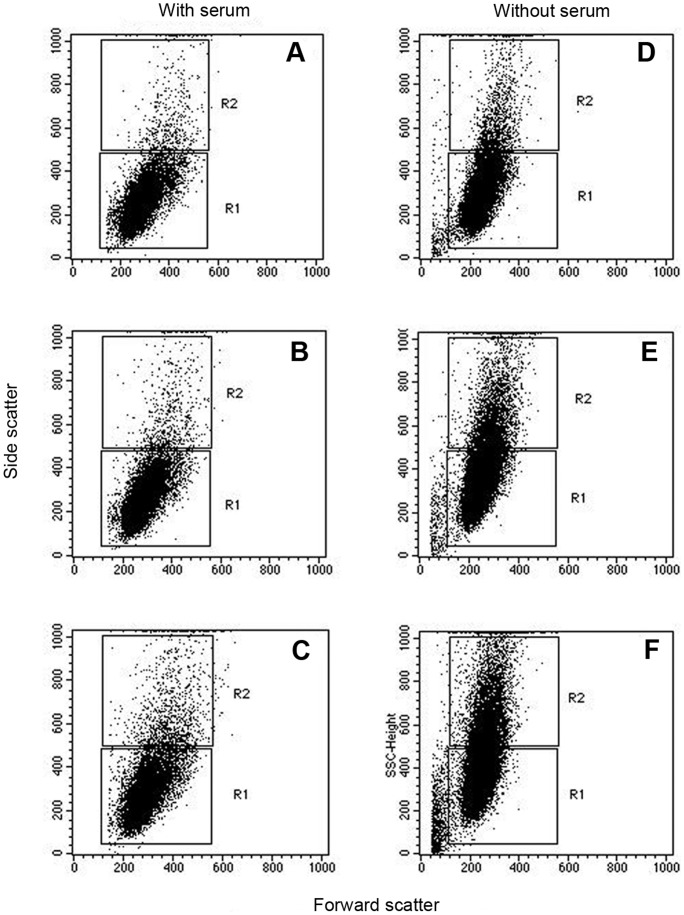

Flow cytometry provides scattering data in addition to the fluorescence. The intensity light scattered at small angles (0.5–2.0°) from the incident laser beam (referred to as forward scattering) is proportional to the cell size. The side scattering at larger angles is a measure of structural changes such as granulated structure on the membrane or cytoplasm that increase the scattering. Examination of changes in scattering properties of Aβ1–42 treated cells revealed no difference in the forward scattering consistent indicating no change in cell size. On the other hand, changes in the granulated structure were apparent as evidenced by an increase in the intensity of side scattering (Fig. 4), which was even more pronounced in the absence of serum.

Figure 4. The morphological changes of Hep-1 cells incubated with Aβ1–42 in the presence and absence of serum analyzed by scattering data.

The effect of Aβ1–42 concentration (A, D: 0 µM; B, E: 5 µM; C, F: 10 µM) in both forward and side scatter values is given in the dot plot.

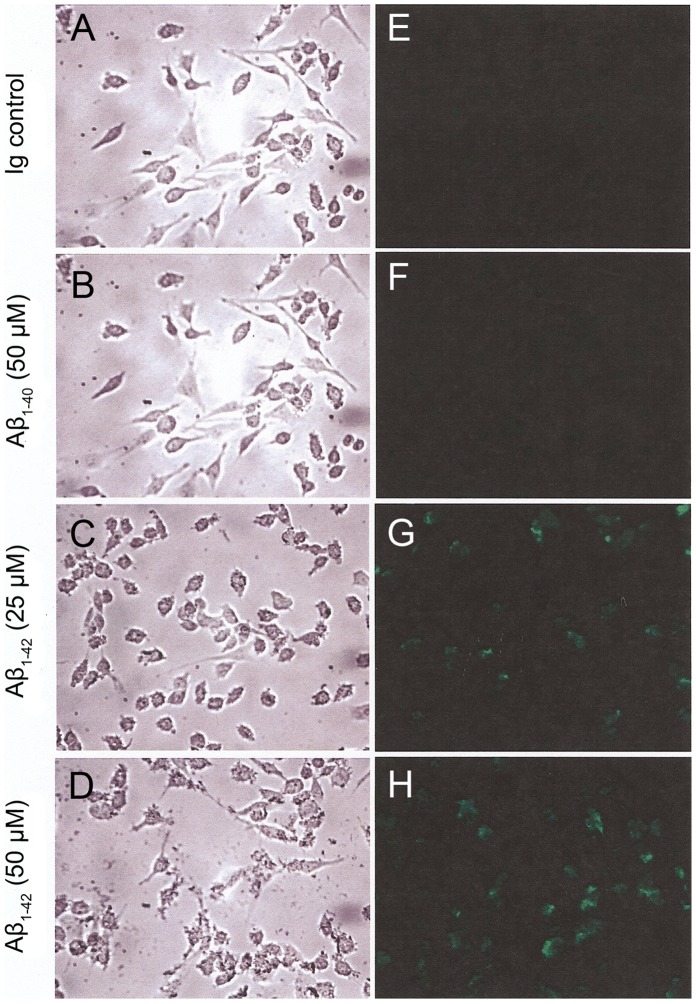

Morphological changes as well as increased production of Aβ1–40 in Aβ1–42 treated cells were further corroborated by light and confocal microscopy (Fig. 5). As found by flow cytometry, no effect was observed by microscopy when the endothelial cells were treated with Aβ1–40 instead of Aβ1–42 (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast, shape changes in some of the cells as well as numerous intracellular and superficial granular patches (tentatively attributed to big amyloid aggregates) were clearly visible by light microscopy when cells were treated with Aβ1–42 fibrils (Fig. 5C and D).

Figure 5. Aβ1–40 expression monitored by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Endothelial cells were incubated with different concentrations of fibrils for 12 hrs and processed as described in the materials and method. Phase contrast (left panels) and fluorescence images (right panel) were taken showing the same field.

Treated and non-treated endothelial cells were stained with antibodies against Aβ1–40 and observed under confocal microscopy (Fig. 5E, F, G, H). A fluorescence signal was only detected in those cells that were exposed to Aβ1–42 (Fig. 5G and H).

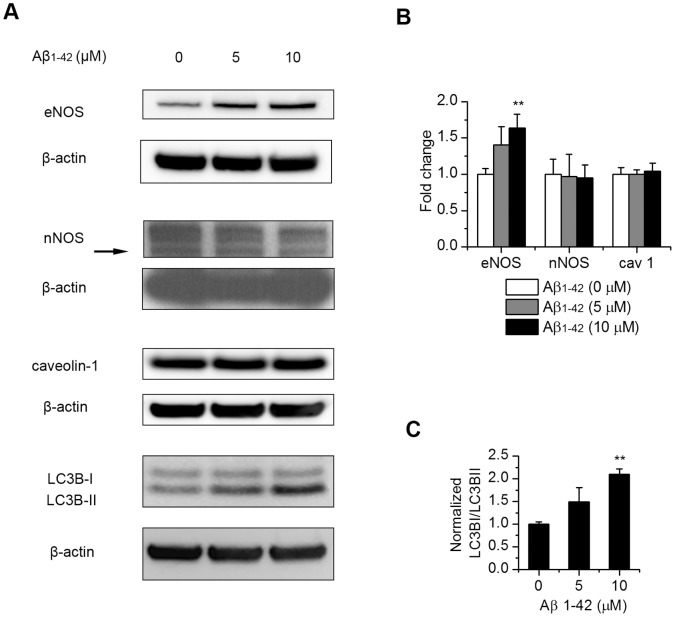

Aβ1–42 Treatment Affects eNOS Expression and Autophagy

To further study the cellular response to Aβ1–42 treatment, we examined the protein levels of the nitric oxide synthases (NOS) which catalyze the production of NO, a known modulator of CNS vascular and neuronal function. After the cells were treated with 5 and 10 µM fibrillar Aβ1–42, Western blot of different NOS isoforms showed a mild but statistically significant increase of endothelial NOS (eNOS) and no change in neuronal NOS (nNOS) level (Fig. 6A and B). Inducible NOS (iNOS) was not detected with or without treatment (data not shown). Since caveolin-1 is shown to interact with eNOS within endothelial plasmalemmal caveolae and affect eNOS function [35], we also examined caveolin-1 protein level but found no change (Fig. 6A and B). Since autophagy is induced under conditions of cell stress and shown to be involved in APP processing [36], we studied the state of autophagy after Aβ1–42 treatment. Increased ratio of LC3B-II/I (Fig. 6A and C), a reliable marker of autophagosomes, indicated activation of autophagy.

Figure 6. Affects of exogenous Aβ1–42 on the level of eNOS and autophagy in endothelial cells.

Endothelial cells were treated with 5 µM and 10 µM Aβ1–42 and incubated for 12 hrs. Protein levels of eNOS, nNOS, caveolin-1 and the autophagy marker LC3B were analyzed by Western blotting (A). (B), quantitation of protein levels of eNOS, nNOS and caveolin-1 normalized to β-actin control. Results are mean ± SD (n = 3–5). (C), quantitation of LC3B II/I ratio normalized to β-actin control. Results are mean ± SD (n = 3). **, P<0.01 compared to control.

Discussion

Major attention has been devoted to the role played by neuronal cells in AD development. Most of the amyloid found in AD subjects is produced in the brain and contained in plaques with a high content of highly aggregated amyloids. However, cognitive function does not generally correlate with the level of cerebral plaques. It was only in recent years that the contribution of the cerebrovascular system has been appreciated [37]–[39]. In this respect, it should be noted that a large proportion of AD patients have cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) involving vascular amyloidosis within the cerebral circulation. It has in fact been proposed that vascular pathology and the resultant impairment of oxygen delivery to the brain may play a primary role in the development of AD [40]. In this study, we have delineated a new role for the cerebrovascular system involving Aβ1–42 fibril induced APP synthesis in the human endothelial cell line Hep-1.

We first demonstrate that incubation of endothelial cells with fibrillar Aβ1–42 results in elevated levels of the APP (Fig. 1). Using an antibody specific for Aβ1–40, we also report an increase in the concentration of Aβ1–40 peptides. This finding is indicated both by flow cytometry (Fig. 2 and 3) and confocal microscopy (Fig. 5E, F, G, H). The increased levels of APP together with increased Aβ1–40 cannot be explained just by altered processing of APP and requires increased synthesis of APP by the endothelial cells.

Such an effect would seem to require that the Aβ1–42 fibrils are endocytosed by cells. Evidence for amyloid uptake and transcytosis in endothelial cells was provided more than a decade ago [41]. Among the potentially physiologically relevant amyloid receptors that can be involved in amyloid uptake, the RAGE (receptor for advanced glycation end products) [42]–[44] was shown to bind Aβ1–40 even in the fibrillar form with a high affinity [45], [46].

Support, from our data, for a contribution of stress to the observed increase in APP and Aβ comes from the augmentation of the effects under serum-deprived conditions [47]. An analogous stimulation of amyloid production has been reported [48] in serum-deprived human primary neuron cultures.

Altered cellular function can be triggered by the aggregation state of the amyloids in addition to stress. Our observation that only Aβ1–42 fibrils but not Aβ1–40 fibrils induce cellular changes implies that this phenomenon is triggered by the highly aggregated fibrillar form that is favored by the Aβ peptide ending at residue 42 [49]. Additional studies will be required to explain how the cellular changes produced by stress and/or amyloid aggregation induce APP synthesis and its processing. Two processes induced by exogenous Aβ fibrils are likely to be involved: inflammatory response and oxidative stress. As for increased APP synthesis, we have previously shown that cellular uptake of fibrillar Aβ induces interleukin-1α (IL-1α) expression [50]. The link between IL-1α and APP can be found in an earlier study which showed an IL-1α mediated upregulation of APP at the translational level [51]. Interestingly, the APP mRNA level was also unchanged after the Hep-1 cells were treated with Aβ1–42 (Rajadas unpublished data) indicating the increase of APP could also be translational in our study. As for increased Aβ production, there is ample evidence that in neuronal cells, Aβ accumulation and oxidative stress, each accelerating the other, generate a vicious circle of more Aβ production and oxidation [52]. Based on our observation, it is possible that the similar process is also taking place in endothelial cells. This notion is supported by an Aβ immunotherapy study which indicated that Aβ depositions in the brain parenchyma and blood vessels occur independently [53].

Once inside the cell, the amyloid can affect many other cellular responses. One of the cellular responses we observed is the upregulation of eNOS (Fig. 6) which is consistent with a previous study showing a Ca2+ dependent induction of eNOS by hydrogen peroxide in endothelial cells. This upregulation has been attributed to a compensatory mechanism for increased superoxide formation [54], [55]. Elevated eNOS expression has been observed in cardiovascular and other vascular pathologies, wherein increased levels of ROS have been detected [56]. Another cellular response we observed is increased autophagy (Fig. 6). Since autophagy is involved in APP processing as a protective mechanism [36], this response is expected and also explains the increased Aβ1–40 production. The intricate relations between oxidative stress and autophagy and its implication in AD vascular pathogenesis awaits further elucidation.

The increased cellular granulation indicated both by changes in side-scattering in the flow cytometry experiment (Fig. 4) as well as by microscopy (Fig. 5) seem to indicate damage to the cells. Thus, coupled with the altered cellular function, and the new synthesis of APP and its metabolism, amyloid toxicity results in damage to the endothelial cells.

In conclusion, our observation of increased APP and amyloid in ECs incubated with Aβ1–42 fibrils establishes, for the first time, that the exposure of endothelial cells to Aβ1–42 fibrils results in an elevated amyloid load in endothelial cells. This process provides a new potential pathway for amyloidosis with these newly formed amyloids in the endothelial cells able to contribute to both vascular amyloidosis and/or parenchyma amyloidosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eliza Anna Ruben and Zhen Cheng for help in editing the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This research was in part supported by the Intramural Research Program the National Institute of Health, National Institute on Aging and National Institute of Health HL095571. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Goedert M, Spillantini MG (2006) A century of Alzheimer’s disease. Science 314: 777–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zlokovic BV (2011) Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 12: 723–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dewachter I, Van Dorpe J, Smeijers L, Gilis M, Kuiperi C, et al. (2000) Aging increased amyloid peptide and caused amyloid plaques in brain of old APP/V717I transgenic mice by a different mechanism than mutant presenilin1. J Neurosci 20: 6452–6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guo Q, Wang Z, Li H, Wiese M, Zheng H (2012) APP physiological and pathophysiological functions: insights from animal models. Cell Res 22: 78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mawuenyega KG, Sigurdson W, Ovod V, Munsell L, Kasten T, et al. (2010) Decreased clearance of CNS beta-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Science 330: 1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Armstrong RA (2006) Classic beta-amyloid deposits cluster around large diameter blood vessels rather than capillaries in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Neurovasc Res 3: 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cullen KM, Kocsi Z, Stone J (2006) Microvascular pathology in the aging human brain: evidence that senile plaques are sites of microhaemorrhages. Neurobiol Aging 27: 1786–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Biffi A, Greenberg SM (2011) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a systematic review. J Clin Neurol 7: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thomas T, Thomas G, McLendon C, Sutton T, Mullan M (1996) beta-Amyloid-mediated vasoactivity and vascular endothelial damage. Nature 380: 168–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu D, Corbett B, Yan Y, Zhang GX, Reinhart P, et al. (2012) Early cerebrovascular inflammation in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11. Vinters HV, Farag ES (2003) Amyloidosis of cerebral arteries. Adv Neurol 92: 105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mattson MP (2002) Involvement of superoxide in pathogenic action of mutations that cause Alzheimer’s disease. Methods Enzymol 352: 455–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ansari MA, Scheff SW (2011) NADPH-oxidase activation and cognition in Alzheimer disease progression. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 171–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kisilevsky R (2000) Amyloids: tombstones or triggers? Nat Med 6: 633–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saido T, Leissring MA (2012) Proteolytic Degradation of Amyloid beta-Protein. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2: a006379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Husemann J, Silverstein SC (2001) Expression of scavenger receptor class B, type I, by astrocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells in normal adult mouse and human brain and in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Am J Pathol 158: 825–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thomas T, McLendon C, Sutton ET, Thomas G (1997) Cerebrovascular endothelial dysfunction mediated by beta-amyloid. Neuroreport 8: 1387–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Iadecola C, Zhang F, Niwa K, Eckman C, Turner SK, et al. (1999) SOD1 rescues cerebral endothelial dysfunction in mice overexpressing amyloid precursor protein. Nat Neurosci 2: 157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yan Y, Wang C (2006) Abeta42 is more rigid than Abeta40 at the C terminus: implications for Abeta aggregation and toxicity. J Mol Biol 364: 853–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eisenhauer PB, Johnson RJ, Wells JM, Davies TA, Fine RE (2000) Toxicity of various amyloid beta peptide species in cultured human blood-brain barrier endothelial cells: increased toxicity of dutch-type mutant. J Neurosci Res 60: 804–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cecchi C, Fiorillo C, Baglioni S, Pensalfini A, Bagnoli S, et al. (2007) Increased susceptibility to amyloid toxicity in familial Alzheimer’s fibroblasts. Neurobiol Aging 28: 863–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beeg M, Stravalaci M, Bastone A, Salmona M, Gobbi M (2011) A modified protocol to prepare seed-free starting solutions of amyloid-beta (Abeta)(1)(-)(4)(0) and Abeta(1)(-)(4)(2) from the corresponding depsipeptides. Anal Biochem 411: 297–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Evin G, Cappai R, Li QX, Culvenor JG, Small DH, et al. (1995) Candidate gamma-secretases in the generation of the carboxyl terminus of the Alzheimer’s disease beta A4 amyloid: possible involvement of cathepsin D. Biochemistry (Mosc). 34: 14185–14192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kuo YM, Webster S, Emmerling MR, De Lima N, Roher AE (1998) Irreversible dimerization/tetramerization and post-translational modifications inhibit proteolytic degradation of A beta peptides of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1406: 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majumdar A, Chung H, Dolios G, Wang R, Asamoah N, et al. (2007) Degradation of fibrillar forms of Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide by macrophages. Neurobiol Aging. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26. Vinters HV, Natte R, Maat-Schieman ML, van Duinen SG, Hegeman-Kleinn I, et al. (1998) Secondary microvascular degeneration in amyloid angiopathy of patients with hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis, Dutch type (HCHWA-D). Acta Neuropathol 95: 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rockenstein E, Adame A, Mante M, Larrea G, Crews L, et al. (2005) Amelioration of the cerebrovascular amyloidosis in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with the neurotrophic compound cerebrolysin. J Neural Transm 112: 269–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Austin SA, Santhanam AV, Katusic ZS (2010) Endothelial nitric oxide modulates expression and processing of amyloid precursor protein. Circ Res 107: 1498–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang H, Ma Q, Zhang YW, Xu H (2012) Proteolytic processing of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid precursor protein. J Neurochem 120 Suppl 1: 9–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Davis-Salinas J, Saporito-Irwin SM, Cotman CW, Van Nostrand WE (1995) Amyloid beta-protein induces its own production in cultured degenerating cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells. J Neurochem 65: 931–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Naiki H, Nakakuki K (1996) First-order kinetic model of Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibril extension in vitro. Lab Invest 74: 374–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hasegawa K, Yamaguchi I, Omata S, Gejyo F, Naiki H (1999) Interaction between A beta(1–42) and A beta(1–40) in Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid fibril formation in vitro. Biochemistry (Mosc) 38: 15514–15521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heffelfinger SC, Hawkins HH, Barrish J, Taylor L, Darlington GJ (1992) SK HEP-1: a human cell line of endothelial origin. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol 28A: 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Olivieri G, Brack C, Muller-Spahn F, Stahelin HB, Herrmann M, et al. (2000) Mercury induces cell cytotoxicity and oxidative stress and increases beta-amyloid secretion and tau phosphorylation in SHSY5Y neuroblastoma cells. J Neurochem 74: 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ju H, Zou R, Venema VJ, Venema RC (1997) Direct interaction of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase and caveolin-1 inhibits synthase activity. J Biol Chem 272: 18522–18525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jaeger PA, Pickford F, Sun CH, Lucin KM, Masliah E, et al. (2010) Regulation of amyloid precursor protein processing by the Beclin 1 complex. PLoS One 5: e11102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Altman R, Rutledge JC (2010) The vascular contribution to Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 119: 407–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bell RD, Zlokovic BV (2009) Neurovascular mechanisms and blood-brain barrier disorder in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 118: 103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reed-Cossairt A, Zhu X, Lee HG, Reed C, Perry G, et al. (2012) Alzheimer’s disease and vascular deficiency: lessons from imaging studies and down syndrome. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res 2012: 929734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Francis P (2006) Targeting cell death in dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 20: S3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zlokovic BV, Ghiso J, Mackic JB, McComb JG, Weiss MH, et al. (1993) Blood-brain barrier transport of circulating Alzheimer’s amyloid beta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 197: 1034–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ueno M, Nakagawa T, Wu B, Onodera M, Huang CL, et al. (2010) Transporters in the brain endothelial barrier. Curr Med Chem 17: 1125–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Deane R, Du Yan S, Submamaryan RK, LaRue B, Jovanovic S, et al. (2003) RAGE mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood-brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med 9: 907–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yan SD, Chen X, Fu J, Chen M, Zhu H, et al. (1996) RAGE and amyloid-beta peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 382: 685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yan SD, Zhu H, Zhu A, Golabek A, Du H, et al. (2000) Receptor-dependent cell stress and amyloid accumulation in systemic amyloidosis. Nat Med 6: 643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Origlia N, Arancio O, Domenici L, Yan SS (2009) MAPK, beta-amyloid and synaptic dysfunction: the role of RAGE. Expert Rev Neurother 9: 1635–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bar-Am O, Weinreb O, Amit T, Youdim MB (2005) Regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins, neurotrophic factors, and APP processing in the neurorescue activity of propargylamine. Faseb J 19: 1899–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. LeBlanc A (1995) Increased production of 4 kDa amyloid beta peptide in serum deprived human primary neuron cultures: possible involvement of apoptosis. J Neurosci 15: 7837–7846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cook DG, Forman MS, Sung JC, Leight S, Kolson DL, et al. (1997) Alzheimer’s A beta(1–42) is generated in the endoplasmic reticulum/intermediate compartment of NT2N cells. Nat Med 3: 1021–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Parvathy S, Rajadas J, Ryan H, Vaziri S, Anderson L, et al. (2009) Abeta peptide conformation determines uptake and interleukin-1alpha expression by primary microglial cells. Neurobiol Aging 30: 1792–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rogers JT, Leiter LM, McPhee J, Cahill CM, Zhan SS, et al. (1999) Translation of the alzheimer amyloid precursor protein mRNA is up-regulated by interleukin-1 through 5′-untranslated region sequences. J Biol Chem 274: 6421–6431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cai Z, Zhao B, Ratka A (2011) Oxidative stress and beta-amyloid protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuromolecular Medicine 13: 223–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nicoll JA, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Steart P, Markham H, et al. (2003) Neuropathology of human Alzheimer disease after immunization with amyloid-beta peptide: a case report. Nat Med 9: 448–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Drummond GR, Cai H, Davis ME, Ramasamy S, Harrison DG (2000) Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression by hydrogen peroxide. Circ Res 86: 347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Breton-Romero R, Gonzalez de Orduna C, Romero N, Sanchez-Gomez FJ, de Alvaro C, et al. (2012) Critical role of hydrogen peroxide signaling in the sequential activation of p38 MAPK and eNOS in laminar shear stress. Free Radic Biol Med 52: 1093–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cai H, Harrison DG (2000) Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ Res 87: 840–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]