Abstract

Opinion statement

In recent years, great success has been achieved on many fronts in the treatment of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), including novel chemotherapeutics, immunotherapies, bone microenvironment-targeted agents, and hormonal therapies. Numerous agents are currently in early-phase clinical trial development for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. These novel therapies target several areas of prostate tumor biology, including the upregulation of androgen signaling and biosynthesis, critical oncogenic intracellular pathways, epigenetic alterations, and cancer immunology. Importantly, the characterization of the prostate cancer genome offers the potential to exploit conserved genetic alterations, which may increase the efficacy of these targeted therapies. Predictive and prognostic biomarkers are urgently needed to maximize therapeutic efficacy and safety of these promising new treatments options in prostate cancer.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Novel, Treatments, Castration-resistant, Androgen receptor, Metastatic, PI3 kinase inhibitors, Androgen synthesis inhibitors, Immunotherapies, Epigenetic, Epithelial mesenchymal transition

Introduction

The characterization of the prostate cancer genome and the identification of conserved genetic alterations have created a new paradigm in the development of novel therapeutics for men with prostate cancer [1••, 2••, 3••]. Within the past 3 years, five additional agents have been FDA-approved for CRPC, including sipuleucel-T, cabazitaxel, abiraterone, denosumab, and most recently enzalutamide [4–8]. Numerous other promising agents are currently under development for advanced disease with well-described lines of evidence supporting their mechanisms of action. Advancements in high-through genomic technologies in the past decade have allowed for the potential pairing of these targeted agents to individual patients who harbor genetic alterations that may optimize their therapeutic potential. The focus of this review is to survey the lines of evidence supporting the development of novel treatments in prostate cancer, as well as highlight the potential exploitation of the genetic landscape toward biomarker development to improve efficacy and ultimately individualize treatment strategies.

Despite standard treatments for localized disease (radiotherapy, prostatectomy, and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT)), a significant number of men will eventually develop disease recurrence and ultimately metastatic cancer, and more than 75 men develop lethal prostate cancer on a daily basis in the United States [9, 10]. Although ADT is highly effective at inducing apoptosis in prostate cancer cells and delays disease progression, patients will inevitably over time develop lethal, castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer (CRPC) [11]. Accordingly, novel approaches outside of standard androgen-deprivation are needed in early-stage disease. The majority of the agents described in this article are being tested in the metastatic setting; however, the eventual application of these agents in the nonmetastatic, neoadjuvant, or adjuvant settings has clear clinical implications in attempting to improve cure rates for advanced localized disease.

Genetic Alterations and Novel Agents

Substantial progress has been made in the past decade to understand the genetic landscape of prostate cancer. Specifically, utilizing integrative genomic techniques, including exome sequencing, array comparative genomic hybridization, and methylation profiling has yielded a wealth of data regarding gene mutations and copy number alterations in prostate cancer [1••, 2••, 3••, 12]. One of the most common genetic alterations discovered is the fusion of TMPRSS2 with the ETS gene family of transcriptions factors (including ERG, ETV1, ETV4) [12, 13]. In preclinical models, upregulation of ERG promotes cell invasion and can induce prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia [14], whereas TMPRSS2 acts as androgen driven promoter and is upregulated in CRPC [12, 15]. The TMPRSS2:ERG fusion occurs in approximately 50 % of prostate cancer patients [16], and the gene product is known to physically interact with the androgen receptor (AR) [1••]. Given the association of androgen signaling and TMPRSS2 in addition to the interaction of ERG with AR, there is interest that the novel agents targeting the androgen axis in CRPC (i.e., abiraterone, enzalutamide) may have increased efficacy in the patients with TMPRSS2:ERG translocations [12]. These hypotheses remain to be validated, as the application of these novel agents in the specific biomarker-driven subgroups has not been tested. Patient selection enriching for this genetic marker may lead to improved outcomes with androgen-directed therapy in the future.

Similarly, increased AR activity through amplication, mutation, splice variants, or overexpression is now considered a hallmark mechanism of resistance in CRPC and is likely a key driver for the castration-resistant phenotype [17, 18]. Integrative genomic approaches have recently provided additional insight into mechanisms governing AR regulation and potential therapeutic targets. Copy number gain involving the AR gene is the single most prevalent alteration seen in metastatic prostate cancer tissue samples, ranging from approximately 50–73 %, and is uncommon in localized disease [1••, 2••, 3••]. Additionally, multiple coactivators and corepressors (including NCOR1/2, RAN, NCOA2) of AR signaling also are altered in a high frequency of prostate cancer specimens, as well as the presence of coamplifications involving areas on chromosomes 7, 8, and X [2••, 3••]. Collectively, these alterations potentially offer additional pathways for androgen signaling in AR-nonamplified tumors as well as potentially early genetic biomarkers of hormone resistance and potential therapeutic intervention. Hypermethylation is generally present in CRPC and may influence expression of multiple androgenic axis genes involved in androgen signaling, including CYP17A1 and HSD17B3, for example [2••]. Interestingly, genetic alterations of several chromatin/histone modification genes have been described in CPRC and these gene products shown to directly interact with AR [1••]. Epigenetic changes in prostate cancer provide rationale for the potential efficacy of hypomethylating and other epigenetic agents in combination with androgen directed therapies.

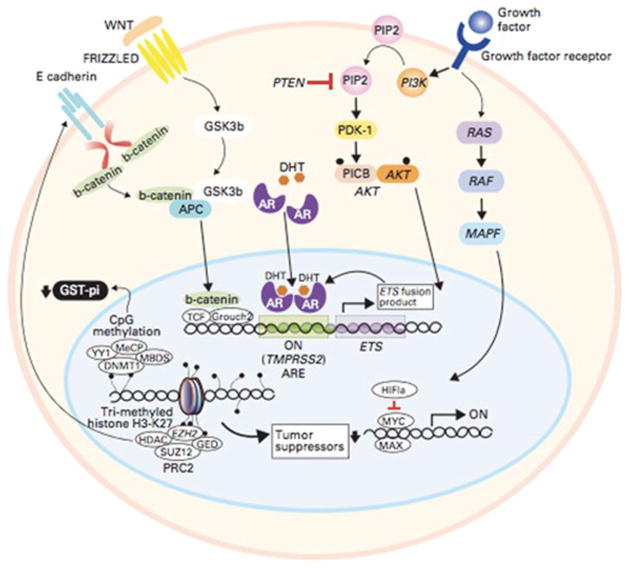

Multiple AR-independent intracellular pathways including PI3K, RB1, and RAS family-MAPK are consistently dysregulated through a variety of mechanisms in advanced prostate cancer (Figs. 1 and 2) [1••, 2••, 3••, 12, 19]. Downstream effects of genetic alterations in these pathways promote survival, proliferation, cell-cycle progression, and conversely regulate AR signaling through feedback mechanisms. Specifically, alterations in the PI3K pathway occur in upwards of 40 % of primary prostate cancers and 100 % of meta-static cases [3••]. Common aberrations described include deletion, point mutations, and methylation of tumor-suppressor gene PTEN, as well as PIK3CA. Furthermore, the TMPRSS2:ERG fusion is associated with both PTEN and TP53 copy-number loss [3••]. Novel combinatorial treatment strategies involving either “horizontal” or “vertical” inhibition of one or multiple signaling pathways have been proposed for instance with combinations of Rb, MEK/RAF, and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors in advanced prostate cancer [19]. Additionally, incorporating validated biomarkers from these pathways should ensure enrichment of benefit for these targeted approaches.

Fig. 1.

Intracellular signaling pathways involved in prostate cancer and opportunities for targeted therapies [12]. AR signaling is modulated by the MAPK, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and b-catenin signaling pathways. Androgen directed agents: enzalutamide, Orteronel, ARN509, EPI509, Galeterone. Signal transduction inhibitors: cabozantinib, GDC-0068, MK2206, XL-147, BKM-120, dasatinib. The TMPRSS2:ETS fusion results in over expression of the ETS gene product which binds to the AR. Tumor suppressor gene transcription is regulated by epigenetic alterations including histone modification and CpG methylation. Epigenetic Alterations: Vorinostat, Pano-binostat, Azacitidine. EMT inhibition: Vismodegib (GDC-0449). Immune check point blockade: Ipilimumab, CT-011. Reprinted with permission. © 2011 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved.

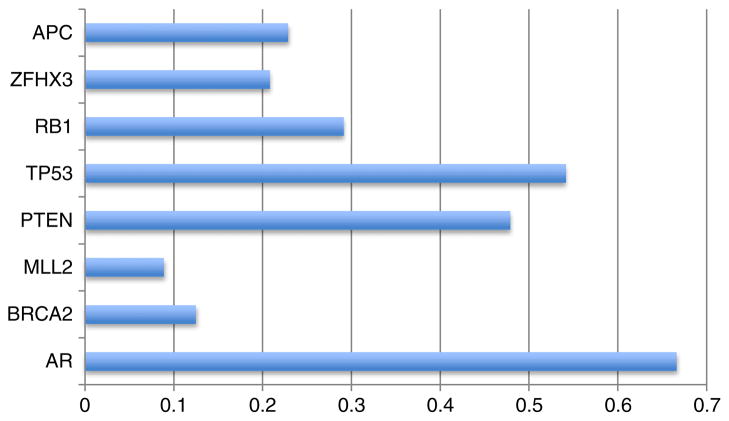

Fig. 2.

Frequency of select genetic alterations in CRPC exomes. AR Androgen receptor, APC adenomatous poliposis coli, ZFHX3 zinc finger homeobox 3, RB1 retinoblastoma 1, TP53 tumor protein 53, PTEN phosphatase and tensin homolog, BRCA2 breast cancer type 2 susceptibility. Data modified from Grasso et al. 2012 [1••].

In the next sections, we will provide a focused discussion of some of these key novel therapies in development, based on the above-emerging biology of CRPC. Recent clinical trial results and specific discussion regarding bone-targeted agents, including alpharadin and denosumab, are beyond the scope of this article and are reviewed elsewhere [20].

Androgen-Directed Agents

Given the established role of androgen signaling in advanced prostate cancer and the success of abiraterone in the pre- and post-docetaxel setting [6, 21], a number of second-generation CYP17 inhibitors and AR antagonists are currently in clinical trial development. Most recently, enzalutamide (formerly MDV3100) was FDA approved for the use in metastatic CRPC following docetaxel treatment based on results from the Phase III AFFIRM trial [8]. Enzalutamide is a small molecule, pure AR antagonist with a binding affinity of approximately fivefold compared with bicalutamide, which interferes with AR nuclear translocation, coactivator recruitment, and DNA binding [22]. The AFFIRM trial randomized men with CPRCP postchemotherapy to either enzalutamide or placebo and was terminated early after demonstrating a 4.8-month survival benefit (hazard ratio (HR) 0.63; P<0.001). Given the substantial response in this setting, multiple studies are evaluating the efficacy of enzalutamide in earlier-stage disease. The PREVAIL phase III randomized trial is comparing enzalutamide with placebo in more than 1,600 chemotherapy-naïve patients with progressive metastatic CRPC. Similarly, STRIVE and TERRAIN are randomized phase II studies that evaluate progression-free survival (PFS) with enzulatamide compared with bicalutamide for recurrent M0/M1 prostate cancer despite ADT. Additionally, two trials determine the benefit of enzalutamide in the neoadjuvant setting prior prostatectomy and in combination with abiraterone for CRPC (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected clinical trials in phase I-III development in prostate cancer. ClinicalTrial.gov. Accessed November 2012

| Class/agent | Description | Clinical trial |

|---|---|---|

| Androgen-directed therapy | ||

| Enzalutamide | Phase II, neoadjuvant before prostatectomy | NCT01547299 |

| Phase II, combination with abiraterone in CRPC | NCT01650194 | |

| Phase II, randomized vs. bicalutamide in CRPC prechemotherapy | NCT01288911 | |

| Phase II, randomized vs. bicalutamide in recurrent prostate cancer following primary ADT (STRIVE) | NCT01664923 | |

| Phase III, randomized vs. placebo for CRPC prechemotherapy (PREVAIL) | NCT01212991 | |

| Orteronel (Tak 700) | Phase I/II, combination with docetaxel and prednisone in CRPC | NCT01034655 |

| Phase II nonmetastatic CRPC and rising PSA | NCT01046916 | |

| Phase III, Randomized vs. placebo plus prednisone in CRPC postchemotherapy | NCT01193257 | |

| Phase III, randomized vs. placebo plus prednisone in prechemotherapy CRPC | NCT01193244 | |

| ARN-509 | Phase I/II, post-Abiraterone, prechemotherapy CRPC | NCT01171898 |

| HSP | ||

| AT13387 | Phase I/II, alone or in combination with Abiraterone in CRPC no longer responding to Abiraterone | NCT01685268 |

| OGX-427 | Phase II, Abiraterone with or without OGX-427 in metastatic CRPC | NCT01681433 |

| Signal transduction agents | ||

| Cabozantinib (XL184) | Phase I, combination with Abiraterone in CRPC | NCT01574937 |

| Phase I, combination with docetaxel and prednisone in CRPC | NCT01683994 | |

| Phase II CRPC and bone metastases | NCT01428219 | |

| Phase III, randomized vs. prednisone in CRPC previosly treated with docetaxel/abiraterone/enzalutamide (COMET-1) | NCT01605227 | |

| Phase III, randomized vs. mitoxantrone in previously treated CRPC (COMET-2) | NCT01522443 | |

| Tivantinib (ARQ197) | Phase II, randomized vs. placebo in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic CRPC | NCT01519414 |

| P13K/AKT/mTOR | ||

| BKM120 | Phase IIb, either BKM120 or BEZ235 in combination with abiraterone in Phase II, metastatic CRPC |

NCT01634061 NCT01385293 |

| GDC-0068 and GDC-0980 | Phase IIb/II, GDC-0068 or GDC0980 randomized vs. abiraterone and prednisone | NCT01485861 |

| MK2206 | Phase II, bicalutamide with or without MK2206 in men with rising PSA after primary treatment | NCT01251861 |

| IGFIR | ||

| CIxutumumab (IMC-A12) | Phase II, combination with ADT for hormone sensitive metastatic prostate cancer | NCT01120236 |

| Src | ||

| Dasatinib | Phase II, abiraterone with or without dasatinib in metastatic CRPC | NCT01685125 |

| Phase III, docetaxel with prednisone with or without dasatinib (READY) | NCT00744497 | |

| Clusterin | ||

| OGX-011 (Custirsen) | Phase III, custirsen in combination with docetaxel/prednisone in chemotherapy naive metastatic CRPC (Synergy) | NCT01188187 |

| Phase III, custirsen in combination with cabazitaxel/prednisone in metastatic CRPC (AFFINITY) | NCT01578655 | |

| Hedgehog | ||

| Vismodegib (GDC 0449) | Phase IIb/III, randomized hormone therapy with or without vismodegib followed by surgery for locally advanced prostate cancer | NCT01163084 |

| PARP inhibition | ||

| Olaparib (AZD2281) | Phase II, metastatic CRPC (TOPARP) | NCT01682772 |

| Velaparib (ABT-888) | Phase II, abiraterone with or without velaparib in metastatic CRPC | NCT01576172 |

| HDAC | ||

| vorinostat | Phase I, in combination with Temsirolimus in metastatic prostate cancer | NCT01174199 |

| Immunomoduatory agents | ||

| Tasquinimod | Phase I, tasquinimod in combination with cabazitaxel and prednisone (CATCH) | NCT01513733 |

| Phase III, randomized vs. placebo in metastatic CRPC | NCT01234311 | |

| Vaccines | ||

| PROSTVAC-VF | Phase II, flutamide with or without PROSTVAC-VF in androgen insensitive localized relapse | NCT00450463 |

| Phase III, randomized vs. placebo in metastatic CRPC | NCT01322490 | |

| Immune check point blockade | ||

| CT-011 (anti PD-1) | Phase II, in combination with Sipuleucel-T with or without CT-011 and Cyclophosphamide in CRPC | NCT01420965 |

| Ipilimumab | Phase II, metastatic CRPC | NCT01498978 |

| Phase II, randomized with or without GM-CSF | NCT01530984 | |

| Phase I/II, Ipilimumab in combination with abiraterone treatment for treatment naive CRPC | NCT01688492 | |

| Phase III, randomized vs. placebo in chemotherapy naive metastatic CRPC | NCT01057810 | |

| Phase III, randomized vs. placebo in metastatic CRPC following docetaxel | NCT00861614 | |

| Epigenetic alteration | ||

| Panobinostat | Phase I/II, combination with bicalutamide in men with CRPC | NCT00878436 |

| Azacitidine | Phase I/II, combination with docetaxel and prednisone following docetaxel treatment | NCT00503984 |

| Antiangiogenic agents | ||

| Bevacizumab | Phase II, ADT with or without bevacizumab following definitely local therapy | NCT00776594 |

| Phase I/II, combination with RAD001, bevacizumab, and docetaxel in metastatic CRPC | NCT00574769 | |

| TRC-105 (anti endoglin) | Phase I/II, monotherapy in metastatic CRPC | NCT01090765 |

| pazopanib | Phase I/II, combination with docetaxel/prednisone metastatic CRPC | NCT01385228 |

| Bone-targeted agents | ||

| Alpharadin (radium-223 dichloride) | Phase I/II, combination with docetaxel for metastatic CRPC | NCT01106352 |

| Expanded access, single arm interventional for metastatic CRPC with bone metastases | NCT01516762 | |

| Phase III, single arm interventional study | NCT01618370 | |

Like enzalutamide, ARN 509 is a second-generation AR antagonist with a similar mechanism but exhibits a slightly higher binding affinity and greater efficacy at lower steady state concentrations for in vivo models [23]. In the initial phase I study involving 24 patients with CRPC, toxicity was low with 20–40 % of patients having fatigue, nausea, and pain. PSA decrease of more than 50 % was seen in 55 % of patients [24]. A phase II is ongoing to evaluate efficacy and planning to enroll 90 men with chemotherapy-naïve CRPC, with 10–20 patients having already received abiraterone. Another pure AR antagonist, ODM-201, was recently shown in a phase I/II study to have response rates of 75–90 % in patients with CRPC, suggesting that this agent should be further evaluated in controlled trials [25].

EPI-001 is a bisphenol diglycidic ether, small molecule that targets with high specificity the N-terminal domain of the AR, resulting in inhibition of transactivation of AR-dependent genes and AR protein-protein interactions. Importantly, in preclinical models, EPI-001 potently inhibits androgen-dependent cell proliferation and tumor growth [26•]. A phase I study with EPI-001 has not yet been initiated; however, combination approaches with either androgen biosynthesis inhibitors or enzalutamide/ARN 509 in patients have been suggested [27]. The activity of these AR-directed therapies in men with CRPC who have mutated or amplified AR is unknown and should be the focus of biomarker-driven future research, given that not all men benefit from these therapies. Additionally, the presence of emergence of AR splice variants likely contributes to AR-directed therapeutic resistance [28, 29].

Intratumoral androgen biosynthesis and paracrine signaling are well-described resistance mechanisms that allow tumor progression despite castrate levels of testosterone and rely on acquired upregulation of multiple enzymes involved in steroidogenesis [30, 31]. Abiraterone, a potent and selective CYP17 inhibitor, effectively inhibits androgen synthesis intratumorally as well as in the testes and adrenals. In men with CRPC before and after the use of docetaxel, abiraterone has demonstrated a substantial benefit in overall survival [6, 21]. Based on this line of evidence, multiple novel agents exploiting the androgen synthesis axis are now in clinical trials. Orteronel (TAK-700) is a selective CYP17 inhibitor with high 17,20-lyase specificity, which provides the theoretical advantage of avoiding mineralocorticoid excess and concomitant corticosteroid use [32, 33]. Results from the phase II M0 CRPC trial in which orteronel was given without prednisone study showed promising safety and efficacy with PSA response rates (>50 % decrease) of up to 62 % at the 600 mg daily dose. Randomized phase III studies are currently active with orteronel with prednisone in patients with CRPC in both prechemotherapy and postchemotherapy settings. Biomarkers of intracrine/autocrine androgen synthesis are needed to assess for the activity of these agents in a selected group of men based on the dependence of the CRPC phenotype on this biology; to date, predictive serum-based biomarkers of androgen synthesis have not been predictive of benefit with abiraterone [34].

Galeterone (TOK-001) is a more potent 17-lyase inhibitor than abiraterone with the distinct advantage of causing AR downregulation resulting in more potent antitumor activity in vitro and in vivo [35]. The initial phase I study was presented recently incorporating 49 patients with chemotherapy naïve CRPC. Overall, galeterone was well-tolerated with grade 3/4 toxicity less than 10 %, and 22 % of men having a response in PSA of more than 50 % [36]. Because the maximum tolerated dose was not reached and efficacy increased with continued dose escalation, the phase I study remains active.

Phosphorylated heat shock protein 27 (HSP27) acts as an AR chaperone in prostate cancer cells, thereby promoting AR stability, nuclear translocation, and transcriptional activity, ultimately resulting in cell survival [37]. Inhibition of HSP27 in a recent phase II trial by OGX-427 showed impressive antitumor activity in patients with CRPC as monotherapy. More than 80 % of patients experience some PSA reduction with OGX-427 therapy. Combinations incorporating AR antagonists with HSP27 inhibition may offer a promising treatment strategy for prostate cancer in the future [38].

Signal Transduction Inhibitors

Multiple transmembrane receptors and intracellular signaling pathways have been implicated in the tumorigenesis and progression of prostate cancer, including PI3K/AKT/mTOR, RAS/RAF/MEK (MAPK), MET, PARP, and Clusterin among others (Fig. 1) [1••, 3••, 19]. Whereas the overall prevalence of individual per-patient alterations is variable, mutations and high copy number gains/losses of genes in these critical oncogenic pathways are common and suggests that targeting these oncogenetic “drivers” of prostate cancer may yield clinical success (Fig. 2) [1••]. Targeted inhibition in several of these pathways has resulted in promising, yet varying efficacy in early-phase trials. However, utilizing genetic biomarkers to identify subgroups of patients with driver mutations may allow selection and application of high efficacy therapeutic agents, which may otherwise be interpreted as largely ineffective.

MET is a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) that binds to hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and subsequently activates multiple signaling cascades, including PI3K and MAPK. MET is dysregulated in multiple malignancies, including prostate cancer [39, 40]. Whereas activation of the MET RTK is highly tumorigenic in murine models, inhibition with concomitant VEGFR2 blockade using the tyrosine kinase inhibitor cabozantinib (XL184) results in potent decreased cell proliferation, apoptosis, and tumor inhibition [39, 41]. Results from a phase II study in men with CRPC have been updated recently; 168 men were randomized to cabozantinib 100 mg daily or placebo, and 100 of these men evaluable for primary endpoint of overall response rate (ORR). After a median follow-up of approximately 4 months, 86 % of patients with bony disease had a complete or partial response (CR or PR) on bone scan and 64 % had improved pain or decreased narcotic requirements. Interestingly, PSA changes were inconsistent and independent of clinical or radiographic activity [42•]. In a subgroup analysis of patients pretreated with docetaxel, similar efficacy was observed. Smith et al. reported after a median follow-up of 4 months that 60 % of patients had partial response (PR) of osseous disease on bone scan and 28 % had stable disease (SD). Fifty percent of patients had improved pain durable for more than 6 months and 92 % had significant decrease in circulating tumor cells of more than 30 %. Grade 3/4 toxicity was limited to fatigue and nausea in 10–20 % of patients [43]. Overall cabozantinib is well tolerated at lower doses in men with CRPC (40–60 mg daily) and appears to have significant clinical activity in patients with osseous disease. The COMET-1 trial is an ongoing, randomized, phase III study of cabozantinib compared with prednisone in pretreated patients with CRPC, whereas the COMET-2 trial compares the durable palliative benefit of cabozantinib with mitoxantrone and prednisone in a double-blinded phase 2–3 companion trial in men with heavily pretreated metastatic CRPC. These trials are being conducted in unselected men without regard for c-met activity.

The high frequency of PTEN deletion or downregulation as well as other mutations that activate the PI3K pathway in both localized and meta-static CRPC (Fig. 2) highlight the importance of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway as a promising axis for targeted therapies as well as combination strategies in prostate cancer [1••, 19]. Single-agent therapy with TORC1 inhibitors, such as rapamycin, temsirolimus, or everolimus, have not shown significant clinical activity to date and suggests the need for combination studies due to the known feedback pathways that act on upstream receptor signaling, MAPK/RAS pathway signaling, and AR signaling. A number of PI3K inhibitors are currently in phase I-II development for prostate cancer and other advanced malignancies, including XL-147, BEZ235, BKM120, and GDC0941 [19]. It is likely that these agents will be most successful when combined with androgen-pathway inhibitors given the preclinical data for AR pathway reciprocal cross-talk [44••, 45]. As such, several early-phase studies are evaluating combination AR and PI3K/AKT/mTOR blockade. For example, GDC-0068 and GDC-0980 are selective inhibitors of AKT and PI3K/mTOR, respectively, and are being tested in combination with abiraterone in metastatic CRPC. The pure PI3K inhibitor BKM120 also is being tested in men with heavily pretreated mCRPC. Another trial with MK2206, an AKT inhibitor, is ongoing in combination with bicalutamide in men with PSA progression after treatment for localized disease.

Src is a membrane associated protein and nonreceptor tyrosine kinase that modulates signal transduction through several pathways, including the PI3K, focal adhesion kinase (FAK), and MAPK resulting in regulation of cell survival, proliferation, and angiogenesis [46]. Approximately one in four CRPC patients will have increased SRC activity, which correlates with metastasis and survival [47]. Dasatinib is a TKI with specificity for Src family kinases, among several other kinase families, and has been evaluated in several phase I/II studies. In 2011, Yu et al. reported the use of dasatinib 100 mg daily in 48 men with metastatic CRPC and noted stable disease at 3 months in 44 % of patients and was well tolerated [48]. Higher radiographic response rates approaching >50 % with durable disease control and a reasonable safety profile was reported by Araujo et al. earlier this year when dasatinib was used in combination with docetaxel [49]. A phase 3 trial of docetaxel with or without dasatinib (the READY trial) has been completed and results are expected in the fall of 2012 (Table 1).

Other targets in which novel agents in clinical trial development have demonstrated promising activity include clusterin and poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP). Clusterin is a stress-induced, ATP-independent molecular chaperone that inhibits apoptosis and is overexpressed in several malignancies including CRPC [50]. Two separate phase II studies have shown clinical benefit with custirsen (OGX-011), an antisense oligonucleotide that inhibits translation initiation of clusterin mRNA [51, 52]. In 2010, Chi et al. reported custirsen in combination with docetaxel and prednisone resulted in superior median OS as a secondary endpoint compared with chemotherapy alone in CRPC (23.8 vs. 16.9 months) [51]. Two large, phase III trials are currently evaluating the survival benefit of custirsen in addition to either cabazitaxel or docetaxel in metastatic CRPC (AFFINITY and SYNERGY, respectively).

Other recent preclinical evidence demonstrates that the TMPRSS:ERG gene product physically interacts with PARP, induces DNA damage, and is required for ERG transcription and cell invasion [53]. PARP inhibition with olaparib effectively inhibits in vivo prostate tumor growth and, interestingly, potentiates ERG-induced DNA damage. Currently, there are two phase II trials ongoing in metastatic CRPC utilizing olaparib as monotherapy and velaparib with abiraterone. Identification of those patients harboring a TMPRSS:ERG fusion may increased benefit from PARP inhibition with either agent, whereas neither study includes this in the entry criteria, the prospective validation of these biomarkers within these trials are important steps.

Immunomodulatory Agents

The success of sipuleucel-T to prolong survival in men with CRPC in the past 3 years has reinforced the feasibility of effective immunotherapy in prostate cancer [4]. Novel approaches in this area recently have included the PROSTVAC-VF vaccine and immune checkpoint blockade with PD-1 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen (CTLA-4) monoclonal antibodies [54]. In particular, PROSTVAC-VF is a pox-virus incorporating PSA with three costimulatory receptors, including B7.1, ICAM-1, and LFA-3 (TRICOM), which was generally well tolerated in phase I studies [55]. A subsequent randomized phase II trial compared PROSTVAC-VF to placebo in 125 men with metastatic CRPC, with a primary endpoint of PFS [56]. Interestingly and similar to that observed with sipuleucel-T, although there was no difference in PFS, after a follow-up of 3 years there was a substantial survival benefit with 30 % of patients alive receiving the vaccine versus 17 % with placebo. The median survival was increased by an impressive 8.5 months (25.1 vs. 16.6 months; HR 0.56; P=0.0061). Whereas the discordance in PFS and OS is striking, it also has been demonstrated with other immunotherapies, including sipuleucel-T and may reflect slowed disease progression following immune activation [57]. A randomized phase III trial is currently ongoing to evaluate PROST-VAC-VF in metastatic CRPC in the prechemotherapy setting.

Both PD-1 and CTLA-4 are expressed on CD4+ helper and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and serve as a checkpoint for effector and regulatory T cell activity, thus controlling antitumor immune response [54]. CTLA-4 inhibition, namely with ipilimumab, has been used extensively in early-phase clinical trials in prostate cancer with PSA responses in 10–20 % of patients [58]. Several large phase III trials have completed enrollment in which ipilimumab was evaluated in both the prechemotherapy and postchemotherapy in metastatic CRPC. In the post-docetaxel CRPC setting, an immune-enhancing initial radiotherapy treatment was delivered before CTLA-4 blockade, with the idea of inducing an abscopal effect in distant metastases, similar to that observed preclinically [59•].

PD-1 blockade in prostate and other cancers has been reported in two recent trials. In a phase I study of patients with advanced cancer, MDX-1106 resulted in tumor response in approximately 10 % of patients. Interestingly, membranous expression of B7-H1, the predominant ligand of PD-1, on tumor cells was associated with treatment response [60]. A larger phase I study of BMS-936558 recently reported a higher response rate of 20 % in patients with advanced cancer, which was durable in most for more than 1 year. Similarly, surface expression of B7-H1 again predicted response to therapy with PD-1 inhibition [61]. Although the small number of patients with prostate cancer in this study did not respond to BMS-936558, further selection using B7-H1 as a predictive biomarker may improve efficacy.

Tasquinimod is a quinoline-3-carboxamide derivative and novel immunomodulator that promotes upregulation in prostate cancer of thrombspondin-1, an inhibitor of angiogenesis and cell migration, and blocks S100A9, a protein that has been implicated in regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment [62–64]. A recent, randomized, phase II study of tasquinimod compared with placebo in more than 200 men with CRPC demonstrated a significant clinical benefit with a 6-month PFS of 69 % versus 37 % (P<0.001), and median PFS was 7.6 versus 3.3 months (P=0.0042) [65•]. Additional trials are currently ongoing with tasquinimod, including a large phase III study compared to placebo in CRPC, as well as the CATCH trial in which tasquinimod is being combined with cabazitaxel.

Epigenetic Alterations

Histone and DNA methylation modifications are common in prostate cancer and facilitate alterations in tumor suppressor and oncogene expression, as well as promote general genomic instability and ultimately allow tumor progression [2••, 66, 67]. Importantly, AR signaling and transcription of AR-dependent genes is intimately tied to chromatin- and histone-modifying proteins and epigenetic modifications [1••, 66]. Inhibition of histone deacetylase (HDAC) and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) have been shown in preclinical models to inhibit AR activity, increase ADT sensitivity, and inhibit prostate cancer growth, but the single agent activity of these agents is poor [66, 68–70]. Vorinostat, a HDAC inhibitor, was tested in a phase II study in men with metastatic CRPC and unfortunately exhibited significant toxicity and limited efficacy [70]. More recently, panobinostat in combination with bicalutamide demonstrated only limited grade 3 toxicity in men with progression after combined androgen blockade [71]. Furthermore, when used in combination with docetaxel resulted in PSA response >50 % in five of eight patients but no clinical antitumor effect as monotherapy [72]. Azacitidine in a phase II trial slowed PSA doubling time or decreased PSA levels in 64.7 % men with chemotherapy naïve CRPC resulting in a median PFS time of 12.3 weeks [73]. Additional phase II studies are ongoing for both of these agents in CRPC (Table 1). Given that these agents may induce potential epithelial differentiation and thus PSA production despite cytoreduction, combination therapies with novel AR and androgen pathway inhibitors should be reevaluated [74].

Developmental and Stromal Cell Pathways

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a fundamental biologic process in normal tissue development; however, in cancer, the loss of polarity, invasiveness, and increased motility are highly pathologic and promote metastatic disease. Men with metastatic CRPC have been shown to have a high level of expression of EMT and stemness biomarkers on their circulating tumor cells (CTCs), suggesting epithelial plasticity during prostate cancer metastasis [75]. In addition, induction of an EMT has been associated with resistance to ADT [76], prostate cancer immunotherapy [77], chemotherapy and stemness properties [78, 79], and radiation therapy and DNA damaging agents [80]. Induction of EMT and stemness is reliant on cross-talk with activated stromal cells and paracrine signaling that promotes invasion of cancer cells during stress [80]. A number of key oncogenic pathways that are active in CRPC converge on EMT transcription factors and may regulate plasticity, including TGF-β–induced clusterin expression, loss of PTEN with PI3K and MAPK activation, and AR blockade, suggesting that inhibiting these pathways may have an impact on plasticity and metastasis [76, 81, 82].

Several agents in preclinical development which target EMT/stemness biology include TGF-beta inhibitors, cabozantinib (discussed above), and a monoclonal antibody against N-cadherin [83–85]. Therapeutic approaches focused on traditional epithelial targets (such as AR and PSA) combined with therapies against mesenchymal/stemness targets may exploit this underlying biology. Stemness pathways active in CRPC include the hedgehog, NOTCH, and beta-catenin pathways and inhibitors of these pathways are in phase 1–2 trials. For example, hedgehog inhibitor vismodegib (GDC-0449) has been evaluated in advanced malignancies and demonstrated particular efficacy in basal cell carcinoma [86, 87]. Currently, a phase I/II study is active testing vismodegib with hormone therapy in men with locally advanced prostate cancer. Hedgehog, along with notch, also may mediate docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer through AKT and Bcl-2, offering additional therapeutic targets [88].

Despite the moderate clinical activity of anti-angiogenic agents in other malignancies, targeting the tumor vasculature in prostate cancer has been largely fraught with disappointing trial results [89, 90]. Most recently, aflibercept, a soluble VEGF receptor, failed to meet its primary endpoint of OS in the phase III VENICE trial, although final publication is still pending at the time of this article. Furthermore, no benefit was found with the addition of bevacizumab to docetaxel and prednisone in unselected men with mCRPC despite an improvement in response rates and PFS, in the phase III CALGB 90401 study [89], Concurrently, targeting VEGF-independent angiogenic pathways that may be involved in resistance mechanisms, or defining serum-based angiogenic, predictive biomarkers may lead to increased rates of response with antiangiogenic agents in the future.

Biomarkers and Future Directions

Given the substantial and dynamic genetic heterogeneity of prostate cancer with the highly variable responses to most of the targeted therapies described above, novel biomarkers are urgently needed to individualized treatment options and signal early disease progression [91, 92]. Clinical prognostic biomarkers in prostate cancer have been known for decades but generally have not guided treatment selection, with the exception of the absence of pain, which is used to select patients who may benefit from sipuleucel-T. The toxicities and rising costs of the above therapies for prostate cancer demand that we evaluate predictive biomarkers that enrich for patient benefit and minimize harms. A detailed discussion of the role of prognostic and predictive biomarkers in CRPC is provided elsewhere [92], and sets a framework for the rational development of these biomarkers paired with therapeutic interventions. Potential predictive biomarkers include ERG status and PARP inhibition, AR amplication and sensitivity to enzalutamide, microtubule mutations and taxane sensitivity, PI3K pathway and Ras pathway aberrations paired with sensitivity to pathway inhibitors, and others. Most recently, serum microRNA levels were shown to be a promising novel biomarker that correlates with the presence of metastatic disease in patients with prostate cancer compared with those without metastases [93].

However, these biomarkers need not be expensive genomic or molecular assays. For example, we recently demonstrated that serum LDH levels were both adversely prognostic for survival and predictive of the benefit of the TORC1 inhibitor temsirolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma, possibly related to the link between LDH levels and TORC1 metabolic pathway activation [94•]. The investigation of this simple blood-based clinically available assay in other diseases, such as CRPC, to select for patients who may benefit from PI3K pathway inhibition, is worthy of study. The thoughtful investigation of noninvasive tests linked to CRPC biology and therapeutic intervention is essential in moving our field forward.

Conclusions

As highlighted in this review, many new promising agents are in clinical trial development, which exploit AR signaling, critical oncogenic intracellular pathways, epigenetic alterations, and tumor immunology. Importantly, the genomic landscape of prostate cancer has been further defined by the characterization of conserved genetic translocations, point mutations, gene copy-number amplification and loss, and modifications to the epigenome. Further studies will likely expose novel targets, such as stemness pathways, micro-RNA circuitry, and complex regulatory elements inherent in the prostate cancer genome. Future efforts in drug development should specifically focus on the pairing of novel agents with predictive genetic alterations in patients to maximize their therapeutic window. This progress in prostate cancer research will undoubtedly rely on predictive biomarkers to guide therapeutic selection and prognostic biomarkers to reflect efficacy.

Footnotes

Disclosures

J.M. Clarke: none. A.J. Armstrong: Consultancy for Amgen, Active Biotech/Ipsen, Sanofi Aventis, Dendreon, BMS, and Bayer, received honoraria from Sanofi Aventis, Dendreon, Pfizer, and Janssen, received payment for development of educational presentations from Dendreon, Sanofi Aventis, Janssen, and Pfizer, and had travel/accommodations expenses covered or reimbursed from Active Biotech, Dendreon, Sanofi Aventis, Pfizer, BMS, and Bayer.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1••.Grasso CS, Wu YM, Robinson DR, et al. The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2012;487:239–43. doi: 10.1038/nature11125. Characterizes common mutations found in exomes of prostate cancer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2••.Friedlander TW, Roy R, Tomlins SA, et al. Common structural and epigenetic changes in the genome of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:616–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2079. Describes comprehensive gene methylation and copy number alterations in prostate cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3••.Taylor BS, Schultz N, Hieronymus H, et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.026. Defines the prostate cancer transcriptome and profile copy number alteration involved in many oncogenic pathways. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fizazi K, Carducci M, Smith M, et al. Denosumab versus zoledronic acid for treatment of bone metastases in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a randomised, double-blind study. Lancet. 2011;377:813–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62344-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou R, Dana T, Bougatsos C, et al. Treatments for localized prostate cancer: systematic review to update the 2002 US preventive services task force recommendation. Rockville (MD): 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, et al. Outcomes of localized prostate cancer following conservative management. JAMA. 2009;302:1202–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seidenfeld J, Samson DJ, Hasselblad V, et al. Single-therapy androgen suppression in men with advanced prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:566–77. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-7-200004040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin MA, Maher CA, Chinnaiyan AM. Common gene rearrangements in prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3659–68. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klezovitch O, Risk M, Coleman I, et al. A causal role for ERG in neoplastic transformation of prostate epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2105–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711711105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai C, Wang H, Xu Y, Chen S, Balk SP. Reactivation of androgen receptor-regulated TMPRSS2: ERG gene expression in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6027–32. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perner S, Demichelis F, Beroukhim R, et al. TMPRSS2: ERG fusion-associated deletions provide insight into the heterogeneity of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8337–41. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohler JL, Gregory CW, Ford OH, 3rd, et al. The androgen axis in recurrent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:440–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1146-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10:33–9. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarker D, Reid AH, Yap TA, de Bono JS. Targeting the PI3K/AKT pathway for the treatment of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4799–805. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saylor PJ, Armstrong AJ, Fizazi K, et al. New and emerging therapies for bone metastases in genito-urinary cancers. Eur Urol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, De Bono JS, et al. Interim analysis (IA) results of COU-AA-302, a randomized, phase III study of abiraterone acetate (AA) in chemotherapy-naive patients (pts) with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2012;30:LBA4518. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324:787–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1168175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clegg NJ, Wongvipat J, Joseph JD, et al. ARN-509: a novel antiandrogen for prostate cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1494–503. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rathkopf DEDD, Morris MJ, Slovin SF, Steinbrecher JE, Arauz G, Rix PJ, Maneval EC, Chen I, Fox JJ, Fleisher M, Larson SM, Scher HI. Phase I/II safety and pharmacokinetic (PK) study of ARN-509 in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): Phase I results of a Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abstract LBA25. 2012 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress Presented; September 30, 2012; European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Congress; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26•.Andersen RJ, Mawji NR, Wang J, et al. Regression of castrate-recurrent prostate cancer by a small-molecule inhibitor of the amino-terminus domain of the androgen receptor. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:535–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.04.027. Novel mechanism of action in targeting the N-termainal domain of the AR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadar MD. Small molecule inhibitors targeting the “achilles’ heel” of androgen receptor activity. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1208–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN_10-3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu R, Lu C, Mostaghel EA, et al. Distinct transcriptional programs mediated by the ligand-dependent full-length androgen receptor and its splice variants in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3457–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mostaghel EA, Marck BT, Plymate SR, et al. Resistance to CYP17A1 inhibition with abiraterone in castration-resistant prostate cancer: induction of steroidogenesis and androgen receptor splice variants. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5913–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanbrough M, Bubley GJ, Ross K, et al. Increased expression of genes converting adrenal androgens to testosterone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2815–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montgomery RB, Mostaghel EA, Vessella R, et al. Maintenance of intratumoral androgens in metastatic prostate cancer: a mechanism for castration-resistant tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4447–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaku T, Hitaka T, Ojida A, et al. Discovery of orteronel (TAK-700), a naphthylmethylimidazole derivative, as a highly selective 17,20-lyase inhibitor with potential utility in the treatment of prostate cancer. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:6383–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ. Emerging therapeutic approaches in the management of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14:206–18. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2011.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryan C, Li J, Kheoh T, Scher HI, Molina A. Abstract LB-434: Baseline serum adrenal androgens are prognostic and predictive of overall survival (OS) in patients (pts) with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): Results of the COU-AA-301 phase 3 randomized trial. Cancer Res. 2012;72:LB-434. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruno RD, Vasaitis TS, Gediya LK, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluations of putative metabolically stable analogs of VN/124-1 (TOK-001): head to head anti-tumor efficacy evaluation of VN/124-1 (TOK-001) and abiraterone in LAPC-4 human prostate cancer xenograft model. Steroids. 2011;76:1268–79. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robert B, Montgomery Eisenberger MA, Rettig M, Chu F, Pili R, Stephenson J, Vogelzang NJ, Morrison J, Taplin M-E. Phase I clinical trial of galeterone (TOK-001), a multifunctional antiandrogen and CYP17 inhibitor in castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) J Clin Oncol. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zoubeidi A, Zardan A, Beraldi E, et al. Cooperative interactions between androgen receptor (AR) and heat-shock protein 27 facilitate AR transcriptional activity. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10455–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chi KN, Hotte SJ, Ellard S, et al. A randomized phase II study of OGX-427 plus prednisone (P) versus P alone in patients (pts) with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2012;30:4514. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yakes FM, Chen J, Tan J, et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:2298–308. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cecchi F, Rabe DC, Bottaro DP. Targeting the HGF/Met signalling pathway in cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1260–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takayama H, LaRochelle WJ, Sharp R, et al. Diverse tumorigenesis associated with aberrant development in mice overexpressing hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:701–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42•.Hussain M, Smith MR, Sweeney C, et al. Cabozantinib (XL184) in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): Results from a phase II randomized discontinuation trial. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2011;29:4516. Highlights the clinical efficacy of targeting MET in prostate cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith MR, Sweeney C, Rathkopf DE, et al. Cabozantinib (XL184) in chemotherapy-pretreated meta-static castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): Results from a phase II nonrandomized expansion cohort (NRE) ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2012;30:4513. [Google Scholar]

- 44••.Carver BS, Chapinski C, Wongvipat J, et al. Reciprocal feedback regulation of PI3K and androgen receptor signaling in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:575–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.008. Describes the interplay between PI3K and AR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mulholland DJ, Tran LM, Li Y, et al. Cell autonomous role of PTEN in regulating castration-resistant prostate cancer growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayer EL, Krop IE. Advances in targeting SRC in the treatment of breast cancer and other solid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3526–32. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tatarov O, Mitchell TJ, Seywright M, Leung HY, Brunton VG, Edwards J. SRC family kinase activity is up-regulated in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3540–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu EY, Massard C, Gross ME, et al. Once-daily dasatinib: expansion of phase II study evaluating safety and efficacy of dasatinib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Urology. 2011;77:1166–71. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Araujo JC, Mathew P, Armstrong AJ, et al. Dasatinib combined with docetaxel for castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from a phase 1–2 study. Cancer. 2012;118:63–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zoubeidi A, Chi K, Gleave M. Targeting the cyto-protective chaperone, clusterin, for treatment of advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1088–93. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chi KN, Hotte SJ, Yu EY, et al. Randomized phase II study of docetaxel and prednisone with or without OGX-011 in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4247–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saad F, Hotte S, North S, et al. Randomized phase II trial of Custirsen (OGX-011) in combination with docetaxel or mitoxantrone as second-line therapy in patients with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer progressing after first-line docetaxel: CUOG trial P-06c. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5765–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brenner JC, Ateeq B, Li Y, et al. Mechanistic rationale for inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in ETS gene fusion-positive prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:664–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gulley JL, Drake CG. Immunotherapy for prostate cancer: recent advances, lessons learned, and areas for further research. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3884–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DiPaola RS, Plante M, Kaufman H, et al. A phase I trial of pox PSA vaccines (PROSTVAC-VF) with B7-1, ICAM-1, and LFA-3 co-stimulatory molecules (TRI-COM) in patients with prostate cancer. J Transl Med. 2006;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kantoff PW, Schuetz TJ, Blumenstein BA, et al. Overall survival analysis of a phase II randomized controlled trial of a Poxviral-based PSA-targeted immunotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1099–105. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.May KF, Jr, Gulley JL, Drake CG, Dranoff G, Kantoff PW. Prostate cancer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5233–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Slovin SF, Hamid O, Tejwani S, et al. Ipilimumab (IPI) in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): Results from an open-label, multicenter phase I/II study. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2012;30:25. [Google Scholar]

- 59•.Dewan MZ, Galloway AE, Kawashima N. Fractionated but not single-dose radiotherapy induces an immune-mediated abscopal effect when combined with anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5379–88. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0265. Demonstrates the efficacy of PD-1 inhibition as an effective anti-tumor agent. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3167–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kallberg E, Vogl T, Liberg D, et al. S100A9 interaction with TLR4 promotes tumor growth. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, Lewis CE. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:618–31. doi: 10.1038/nrc2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Olsson A, Bjork A, Vallon-Christersson J, Isaacs JT, Leanderson T. Tasquinimod (ABR-215050), a quinoline-3-carboxamide anti-angiogenic agent, modulates the expression of thrombospondin-1 in human prostate tumors. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:107. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65•.Pili R, Haggman M, Stadler WM, et al. Phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of tasquinimod in men with minimally symptomatic metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4022–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6295. Illustrates importance of manipulating tumor microenvironment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Perry AS, Watson RW, Lawler M, Hollywood D. The epigenome as a therapeutic target in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:668–80. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Berger MF, Lawrence MS, Demichelis F, et al. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature. 2011;470:214–20. doi: 10.1038/nature09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zorn CS, Wojno KJ, McCabe MT, Kuefer R, Gschwend JE, Day ML. 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine delays androgen-independent disease and improves survival in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate mouse model of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2136–43. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Welsbie DS, Xu J, Chen Y, et al. Histone deacetylases are required for androgen receptor function in hormone-sensitive and castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:958–66. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bradley D, Rathkopf D, Dunn R, et al. Vorinostat in advanced prostate cancer patients progressing on prior chemotherapy (National Cancer Institute Trial 6862): trial results and interleukin-6 analysis: a study by the Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Clinical Trial Consortium and University of Chicago Phase 2 Consortium. Cancer. 2009;115:5541–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferrari AC, Stein MN, Alumkal JJ, et al. A phase I/II randomized study of panobinostat and bicalutamide in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) patients progressing on second-line hormone therapy. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2011;29:156. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rathkopf D, Wong BY, Ross RW, et al. A phase I study of oral panobinostat alone and in combination with docetaxel in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:181–9. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1289-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sonpavde G, Aparicio AM, Delaune R, et al. Azacitidine for castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing on combined androgen blockade. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2008;26:5172. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Verheul HM, Qian DZ, Carducci MA, Pili R. Sequence-dependent antitumor effects of differentiation agents in combination with cell cycle-dependent cytotoxic drugs. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;60:329–39. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Armstrong AJ, Marengo MS, Oltean S, et al. Circulating tumor cells from patients with advanced prostate and breast cancer display both epithelial and mesenchymal markers. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:997–1007. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sun Y, Wang BE, Leong KG, et al. Androgen deprivation causes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the prostate: implications for androgen-deprivation therapy. Cancer Res. 2012;72:527–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kottke T, Errington F, Pulido J, et al. Broad antigenic coverage induced by vaccination with virus-based cDNA libraries cures established tumors. Nat Med. 2011;17:854–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gupta PB, Onder TT, Jiang G, et al. Identification of selective inhibitors of cancer stem cells by high-throughput screening. Cell. 2009;138:645–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sun Y, Campisi J, Higano C, et al. Treatment-induced damage to the tumor microenvironment promotes prostate cancer therapy resistance through WNT16B. Nat Med. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nm.2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mulholland DJ, Kobayashi N, Ruscetti M, et al. Pten loss and RAS/MAPK activation cooperate to promote EMT and metastasis initiated from prostate cancer stem/progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1878–89. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shiota M, Zardan A, Takeuchi A, et al. Clusterin mediates TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis via Twist1 in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2012 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu K, Zeng J, Li L, et al. Silibinin reverses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in metastatic prostate cancer cells by targeting transcription factors. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:1545–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tanaka H, Kono E, Tran CP, et al. Monoclonal antibody targeting of N-cadherin inhibits prostate cancer growth, metastasis and castration resistance. Nat Med. 2010;16:1414–20. doi: 10.1038/nm.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Singh RP, Raina K, Sharma G, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits established prostate tumor growth, progression, invasion, and metastasis and suppresses tumor angiogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate model mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7773–80. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.LoRusso PM, Rudin CM, Reddy JC, et al. Phase I trial of hedgehog pathway inhibitor vismodegib (GDC-0449) in patients with refractory, locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2502–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Domingo-Domenech J, Vidal SJ, Rodriguez-Bravo V, et al. Suppression of acquired docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer through depletion of notch- and hedgehog-dependent tumor-initiating cells. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:373–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kelly WK, Halabi S, Carducci M, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial comparing docetaxel and prednisone with or without bevacizumab in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: CALGB 90401. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1534–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.4767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ou Y, Michaelson MD, Sengelov L, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of sunitinib in combination with prednisone (SU+P) versus prednisone (P) alone in men with progressive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2011;29:4515. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Agarwal N, Sonpavde G, Sternberg CN. Novel molecular targets for the therapy of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2012;61:950–60. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Armstrong AJ, Eisenberger MA, Halabi S, et al. Biomarkers in the management and treatment of men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2012;61:549–59. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bryant RJ, Pawlowski T, Catto JW, et al. Changes in circulating microRNA levels associated with prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:768–74. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94•.Armstrong AJ, George DJ, Halabi S. Serum lactate dehydrogenase predicts for overall survival benefit in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with inhibition of Mammalian target of rapamycin. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3402–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.9631. First predictive biomarker in GU oncology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]