Background: Interactions between p53 and Bcl-2 family proteins serve a critical role in transcription-independent p53 apoptosis.

Results: We studied the interactions of p53TAD2 with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins at the atomic level by NMR, mutagenesis, and structure calculation.

Conclusion: Bcl-XL/Bcl-2, MDM2, and CBP/p300 share similar modes of binding to the dual p53TAD motifs.

Significance: Dual-site interaction of p53TAD is a highly conserved mechanism in the transcription-dependent and transcription-independent p53 apoptotic pathways.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Bcl-2 Family Proteins, Mitochondrial Apoptosis, NMR, p53, Protein Complexes, Protein Structure, Protein/Protein Interactions, Dual-site Interaction

Abstract

Molecular interactions between the tumor suppressor p53 and the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins play an important role in the transcription-independent apoptosis of p53. The p53 transactivation domain (p53TAD) contains two conserved ΦXXΦΦ motifs (Φ indicates a bulky hydrophobic residue and X is any other residue) referred to as p53TAD1 (residues 15–29) and p53TAD2 (residues 39–57). We previously showed that p53TAD1 can act as a binding motif for anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. In this study, we have identified p53TAD2 as a binding motif for anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins by using NMR spectroscopy, and we calculated the structures of Bcl-XL/Bcl-2 in complex with the p53TAD2 peptide. NMR chemical shift perturbation data showed that p53TAD2 peptide binds to diverse members of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family independently of p53TAD1, and the binding between p53TAD2 and p53TAD1 to Bcl-XL is competitive. Refined structural models of the Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 and Bcl-2·p53TAD2 complexes showed that the binding sites occupied by p53TAD2 in Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 overlap well with those occupied by pro-apoptotic BH3 peptides. Taken together with the mutagenesis, isothermal titration calorimetry, and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement data, our structural comparisons provided the structural basis of p53TAD2-mediated interaction with the anti-apoptotic proteins, revealing that Bcl-XL/Bcl-2, MDM2, and cAMP-response element-binding protein-binding protein/p300 share highly similar modes of binding to the dual p53TAD motifs, p53TAD1 and p53TAD2. In conclusion, our results suggest that the dual-site interaction of p53TAD is a highly conserved mechanism underlying target protein binding in the transcription-dependent and transcription-independent apoptotic pathways of p53.

Introduction

The tumor suppressor p53 induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in response to a variety of cellular stresses such as DNA damage, hypoxia, oncogene expression, and viral infection (1–3). Under normal conditions, a balanced cellular level of p53 is maintained by its negative regulator, mouse double minute 2 (MDM2).3 Furthermore, the function of p53 has been shown to be defective in more than 50% of human cancers (4). Therefore, restoring the wild-type p53 and/or blocking the p53/MDM2 interactions are attractive strategies for cancer therapy, because both could result in a homeostasis of the wild-type p53 functioning in cancer cells. p53 consists of a transactivation domain (TAD), proline-rich domain, DNA-binding domain (DBD), oligomerization domain, and C-terminal domain. The p53 transactivation domain (p53TAD) consists of N-subdomain (residues 1–40) and C-subdomain (residues 41–61) with independent transactivation activities (5). Each of the subdomains contains a positionally conserved ΦXXΦΦ motif (where Φ indicates a bulky hydrophobic residue and X is any other residue) referred to as p53TAD1 (residues 15–29) or p53TAD2 (residues 39–57) (Fig. 1A). Interactions of p53TAD with components of the basal transcriptional machinery are neutralized by the N-terminal domain of MDM2. Therefore, neutralization of MDM2 could be inhibited by p53TAD mimetic compounds for cancer treatment. In particular, the α-helical structural element observed in the 15-residue p53TAD1 peptide, which binds to the N-terminal domain of MDM2 (6), has served as a useful structural template for designing novel MDM2 antagonists as anti-cancer agents.

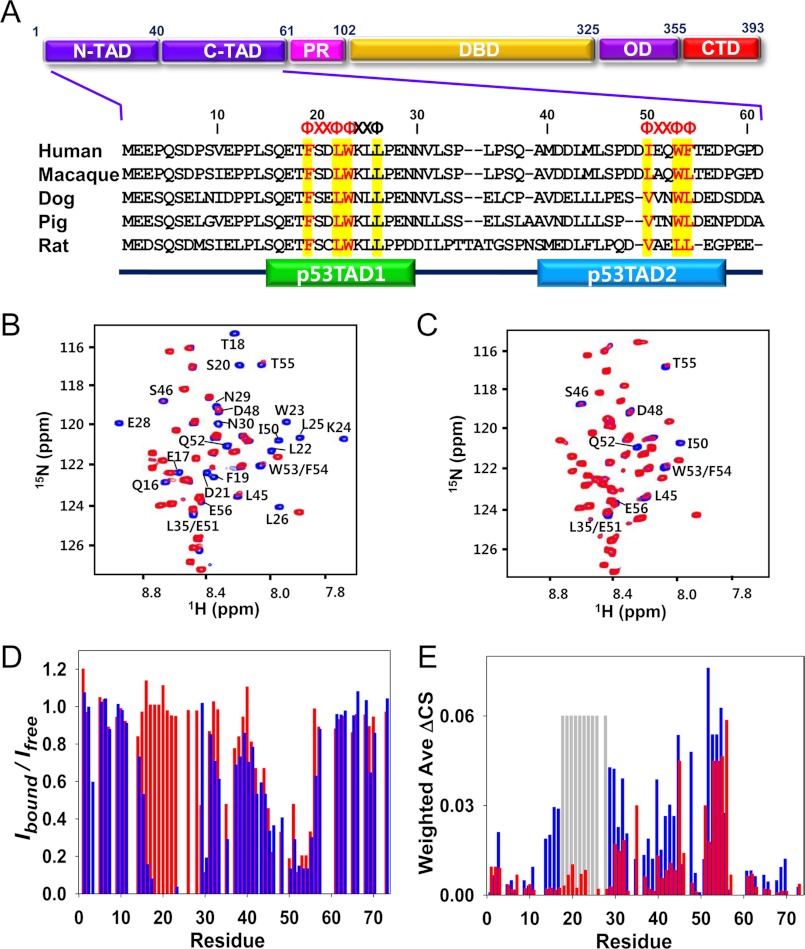

FIGURE 1.

Interaction of p53TAD2 with Bcl-XL. A, domain organization of p53 and sequence alignment of p53TADs from different species. p53 consists of N- and C-terminal transactivation domains (N-TAD and C-TAD), proline-rich domain (PR), DNA-binding domain (DBD), oligomerization domain (OD), and C-terminal domain (CTD). Φ and X indicate a bulky hydrophobic residue and any other residue, respectively. Overlaid two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra for 15N-labeled wild-type p53TAD (B) and mutant p53TAD (L22A/W23A) (C) in the absence (blue) or presence (red) of Bcl-XL. D, cross-peak intensity ratio (Ibound/Ifree) for wild-type p53TAD (blue) and mutant p53TAD (L22A/W23A) (red). E, chemical shift perturbations on wild-type p53TAD (blue) and mutant p53TAD (L22A/W23A) (red) induced by Bcl-XL binding. Weighted ΔCS values were calculated using the equation ΔCS = ((Δ1H)2 + 0.2(Δ15N)2)0.5. Resonances that disappeared upon binding are shown as gray bars.

Although previous studies have extensively focused on transcription-dependent apoptotic regulation of p53, evidence for a transcription-independent mechanism of p53 has accumulated in recent years (7–11). Mihara et al. (11) reported that p53 exerts a direct apoptogenic role at the mitochondria. In response to apoptotic stimuli, p53 rapidly translocates to the mitochondria and induces apoptosis in the absence of transcriptional activity of p53. This transcription-independent apoptosis of p53 is mediated through its interactions with anti-apoptotic as well as pro-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family proteins at the mitochondria. For example, p53 has been shown to bind to the anti-apoptotic Bcl-XL and Bcl-2, leading to the formation of membrane pores by pro-apoptotic Bak/Bax at the outer mitochondrial membrane, resulting in the subsequent release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria into the cytosol (12).

The Bcl-2 protein family plays a critical role in the regulation of apoptosis by controlling the permeability of the outer mitochondrial membrane and thus cytochrome c release (8, 10, 11). This family of proteins is classified into anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic subfamilies based on the modular structure of Bcl-2 homology (BH) domains. It maintains the balance between cell death and survival through interactions between anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members. The anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family members Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 were the first known molecular targets of mitochondrial p53. Interaction of p53 with these proteins is important, because it links transcription-independent apoptosis of p53 to the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. However, detailed molecular mechanisms underlying interactions between p53 and the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family are still unclear. Interactions of p53 with Bcl-XL andBcl-2 have been observed at the cellular level (11), and p53DBD was initially proposed to be the binding site for Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 (12–14). However, Chipuk et al. (15) showed that the p53 N-terminal domain (p53NTD) encompassing p53TAD as well as the p53 proline-rich domain (p53PR) is both necessary and sufficient to trigger a transcription-independent apoptosis. Furthermore, the caspase-cleaved N-terminal fragment of p53 (residues 1–186), which encompasses p53NTD, induces a transcription-independent apoptosis by p53 (16). These findings raise the possibility that p53NTD alone, without p53DBD, can bind to members of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family and mediate a transcription-independent apoptosis outside the nucleus. Recently, we showed that the first ΦXXΦΦ motif, p53TAD1, interacts with various members of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family, which shares a similar mode of binding with MDM2 (17–20).

In this study, we have conducted structural studies to examine molecular interactions between the second ΦXXΦΦ motif and multiple anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members, by using NMR spectroscopy. Our data supported a novel conserved biological role by the p53TAD2 motif in the transcription-independent mechanism of p53 in coordination with the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. Here, we demonstrated that the α-helical p53TAD2 motif binds to hydrophobic pro-apoptotic BH3 peptide-binding grooves in Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 in an analogous manner to that of pro-apoptotic BH3 peptides. Based on our data, we propose a model that the dual-site interaction patterns of p53TAD with the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins in the transcription-independent p53 apoptotic pathway closely mimic interactions of p53TAD with MDM2 or cAMP-response element-binding protein-binding protein (CBP)/p300 in the transcription-dependent p53 apoptotic pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Purification and Peptide Synthesis

Truncated Bcl-XL (18), Bcl-2 (21), and Bcl-w(1–157) (22) were expressed and purified for NMR experiments as reported previously. Wild-type p53TAD2 (residues 39–57), its mutant peptides (D49A, I50K, E51K, W53A, and F54A), and N-terminal Cys-attached p53TAD2 peptide were chemically synthesized and purified by Peptron Inc. as described previously (18).

NMR Spectroscopy

All NMR data were acquired on Bruker Avance II 800 and 900 spectrometers equipped with a cryogenic probe at Korea Basic Science Institute. The two-dimensional 15N-1H HSQC spectra of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family members (Bcl-XL, Bcl-2, and Bcl-w) were obtained at 25 °C in the absence or presence of p53TAD2 peptide. The NMR samples composed of 90% H2O, 10% D2O were prepared in 20 mm sodium phosphate (pH 6.5), 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT for Bcl-XL, 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), and 5 mm DTT for Bcl-2 and 20 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.3), 50 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, and 3 mm DTT for Bcl-w. For chemical shift perturbation experiments for the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, aliquots of concentrated p53TAD2 peptide stock solution were added to the 15N-labeled Bcl-2 family proteins during titration, and two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra were collected at 25 °C (for Bcl-XL and Bcl-2) or 30 °C (for Bcl-w). All NMR data were processed and analyzed using nmrPipe/nmrDraw and SPARKY software.

Binding Affinity Measurement by NMR Titration

To measure the binding affinity of p53TAD2 to Bcl-XL, binding curves were obtained from a two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC titration of 15N-labeled Bcl-XL with p53TAD2 peptide. Weighted chemical shift perturbations were calculated using the equation ΔCS = ((Δ1H)2 + 0.2(Δ15N)2)0.5, in which Δ1H and Δ15N represent the chemical shift changes on the 1H and 15N dimensions. Chemical shift values were calculated by averaging the weighted individual chemical shifts of the three residues, Ala-93, Ala-142, and Arg-165, located in close proximity to the binding groove. Resultant binding curves were fitted to a single site binding model using nonlinear least squares method. The dissociation constant was obtained by averaging the Kd values of the three residues, which was calculated by fitting the binding curve of each residue.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

ITC measurements were performed at 25 °C in a buffer containing 20 mm sodium phosphate (pH 6.5) and 50 mm NaCl, using an Auto-iTC200 Microcalorimeter at Korea Basic Science Institute, p53TAD2 peptide was titrated into the calorimeter cell containing 1 mm Bcl-XL using 2-μl injections. The data were analyzed using the MicroCal OriginTM software.

Resonance Assignment of p53TAD2 Peptide Bound to Bcl-XL

To analyze the structure of the p53TAD2 peptide bound to Bcl-XL, homonuclear two-dimensional 1H-1H NOESY and total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) experiments of 1 mm p53TAD2 peptide were conducted at 10 °C in the presence of 0.1 mm Bcl-XL. Mixing times of 65 ms for TOCSY and 100–200 ms for transferred NOESY were used to record data. Resonance assignment of the p53TAD2 peptide was manually performed according to a standard assignment protocol using NOESY and TOCSY spectra. The TOCSY spectrum was used to identify individual spin systems of amino acids, and the NOESY spectrum was then used to link these systems to amino acids in the peptide sequence.

Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement (PRE) Experiments

Spin labeling at an N-terminal cysteine residue of Cys-p53TAD2 peptide was conducted using methane thiosulfonate (MTSL) (Toronto Research Chemicals, Toronto, Canada) (23). The Cys-p53TAD2 peptides were incubated with MTSL for 16 h at 4 °C in nonreducing buffer, and excess MTSL was removed by passage over a Sephadex G-10 column (Amersham Biosciences) pre-equilibrated in NMR sample buffer (20 mm sodium phosphate (pH 6.5), 150 mm NaCl) without DTT. The reduced compound was generated by incubation with 1.5 mm ascorbic acid for 1 h. The two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled Bcl-XL were acquired at a 1:1 molar ratio of Bcl-XL to MTSL-labeled Cys-p53TAD2 in the oxidized and reduced state.

Structure Calculations

The structures of Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 and Bcl-2·p53TAD2 complexes were calculated as described previously (18) using the program HADDOCK 2.0 (24) in combination with crystallography and NMR system (CNS). The structure of p53TAD2 residues 45–58 derived from its complex with TFIIH Tfb1 (PDB code 2GS0) was used for docking with Bcl-XL and Bcl-2. Ambiguous interaction restraints for Bcl-XL/Bcl-2 and p53TAD2 were derived from NMR chemical shift perturbation data and mutagenesis data (Table 1). The active residues of Bcl-XL/Bcl-2 were defined as those showing chemical shift perturbations larger than the average (ΔCS >0.05 ppm) or being substantially broadened at the protein to peptide ratio of 1:4 with relative residue-accessible surface area larger than 30% for either side-chain or main-chain atoms as calculated with NACCESS program. The active residues of p53TAD2 for Bcl-XL docking were defined from site-directed mutagenesis data. These experimental restraints were used as input for the HADDOCK program, and default parameters were used. Rigid-body energy minimizations were performed with the structures of Bcl-XL (PDB code 1BXL) and Bcl-2 (PDB code 1GM5), leading to 2000 rigid-body docking solutions. In terms of intermolecular interaction energy, the 400 lowest energy solutions of the complexes were selected for rigid-body simulated annealing followed by semi-flexible simulated annealing in torsion angle space. The resulting structures were finally refined in explicit water using simulated annealing in Cartesian space. The docking solutions were clustered based on positional root mean square deviation values using a 3-Å cutoff. The quality of the HADDOCK-derived structural models was assessed using PROCHECK (25) and analyzed by PyMOL. All of the figures showing the structures were generated by PyMOL.

TABLE 1.

Structural statistics for the Bcl-XL/Bcl-2 and p53TAD2 complexes

The abbreviations used are as follows: AIR, ambiguous interaction restraints; r.m.s.d., root mean square deviation.

| Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 complex | Bcl-2·p53TAD2 complex | |

|---|---|---|

| Ambiguous interaction restraints | ||

| Active residues (Bcl-XL/Bcl-2) | 101, 105, 129, 130, 138, 139, 142 | 104, 109, 114, 129, 132, 141, 142, 145 |

| Passive residues (Bcl-XL/Bcl-2) | 96, 100, 104, 132, 136 | 107, 108, 110, 111, 115, 118, 120, 136, 146 |

| Active residues (p53TAD2) | 50, 53, 54 | 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 |

| Passive residues (p53TAD2) | 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 52, 55 | 44, 58 |

| Statistics of the final eight best energy water-refined structures | ||

| Haddock scorea | −113.299 ± 12.348 | −60.488 ± 10.496 |

| Energies | ||

| Electrostatic | −280.08 ± 61.72 kcal/mol | −149.23 ± 15 kcal/mol |

| van der Waals | −35.19 ± 7.77 kcal/mol | −50.81 ± 7.81 kcal/mol |

| AIR | 10.56 ± 9.63 kcal/mol | 70.26 ± 29.44 kcal/mol |

| Buried surface area | 1422.823 ± 69.545 Å2 | 1334.335 ± 65.171 Å2 |

| Backbone r.m.s.d. to the average structure on interface | 0.707 ± 0.424 Å | 0.616 ± 0.318 Å |

| Ramachandran map regionsb,c | 81.0/16.6/1.3/1.1% | 80.6/15.6/1.8/2.5% |

a HADDOCK score is defined as: 1.0·EvdW + 0.2·Eelec + 0.1·EAIR + 1.0·Edesolv (EvdW indicates the van der Waals energy; Eelec indicates the electrostatic energy; EAIR indicates the ambiguous interaction restraint energy, and Edesolv indicates the desolvation energy calculated using the atomic desolvation parameters of Fernandez-Recio et al. (49)).

b Ramanchandran map region is determined using the program PROCHECK-NMR (25). Favored/additionally allowed/generously allowed/disallowed regions are displayed with percentage unit.

c Please note that the presence of disallowed regions in the Ramachandran plot analysis originates from initial structural templates for docking (Ramachandran map regions 76.8/15.9/4.9/2.4% for free Bcl-XL (PDB code 1BXL); 78.3/18.2/1.4/2.1% for free Bcl-2 (PDB code 1GM5)), and the residues corresponding to disallowed regions (Ala-37 in Bcl-XL; Ala-4 and Asp-31 in Bcl-2) are located in the loops distant from the p53TAD2-binding site.

RESULTS

p53TAD2 Directly Interacts with Bcl-XL

Although p53TAD is intrinsically disordered, sequence alignment of p53TADs from many species demonstrates that the “ΦXXΦΦ” sequence motif of both p53TAD1 and p53TAD2 are highly conserved (Fig. 1A). In previous studies, we showed that p53TAD1 acts as a binding motif for anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family members. To investigate if p53TAD2 is also involved in binding to anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, we have monitored chemical shift perturbations of the 15N-labeled full-length p53TAD in the presence of Bcl-XL using NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 1B). Upon binding to Bcl-XL, severe line broadening and significant NMR chemical shift perturbations were observed not only in p53TAD1 but also in the p53TAD2, indicating that p53TAD2 binds to the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family members.

To test whether the p53TAD2 resonance change is merely secondary effects of p53TAD1 binding, we generated a full-length p53TAD (L22A/W22A) mutant and conducted NMR binding experiments with Bcl-XL (Fig. 1C). As demonstrated by much larger cross-peak intensities of p53TAD1 residues in the Bcl-XL-bound state than those of wild-type p53TAD (Fig. 1C), the p53TAD (L22A/W23A) mutation completely disrupted the binding of p53TAD1 to Bcl-XL. However, the p53TAD2 residues in the p53TAD (L22A/W23A) mutant showed similar reduction of cross-peak intensity (Fig. 1D) and chemical shift perturbations (Fig. 1E) upon Bcl-XL binding as in wild-type p53TAD, indicating that the p53TAD2 motif within full-length p53TAD actively participates in direct binding to Bcl-XL independently of p53TAD1. This suggests a direct interaction between p53TAD2 and Bcl-XL as an alternative mode of binding to p53TAD1.

p53TAD2 Binds to Diverse Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 Protein Family Members

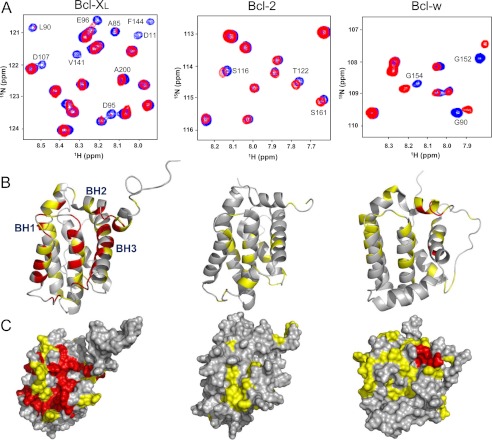

To further probe the interaction of p53TAD2 with diverse anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, we monitored the binding of 15N-labeled Bcl-XL, Bcl-2. and Bcl-w with the isolated p53TAD2 peptide by using NMR. Fig. 2A shows the overlaid two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra for these proteins in the absence or presence of the p53TAD2 peptide. During NMR titration with the p53TAD2 peptide, some of 1H-15N cross-peaks of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins significantly shifted and others disappeared from the 1H-15N HSQC spectra, indicating that the complex is in fast to intermediate exchange on the NMR time scale. With increasing concentrations of the p53TAD2 peptide, we observed significant chemical shift perturbations in all the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins tested, although the degree of chemical shift perturbations varied (Bcl-XL ≅ Bcl-w > Bcl-2). This suggests that p53TAD2 alone can serve as a structural motif to interact with the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. The NMR chemical shift perturbations induced by binding to p53TAD2 were localized to a central hydrophobic cleft composed of the BH1, BH2, and BH3 domains in the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins (Fig. 2, B and C). These results are in very good agreement with what was observed in binding of the p53TAD1 peptide to the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. Thus, our results showed that not only p53TAD1 but also p53TAD2 motifs are universally involved in binding to diverse anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins.

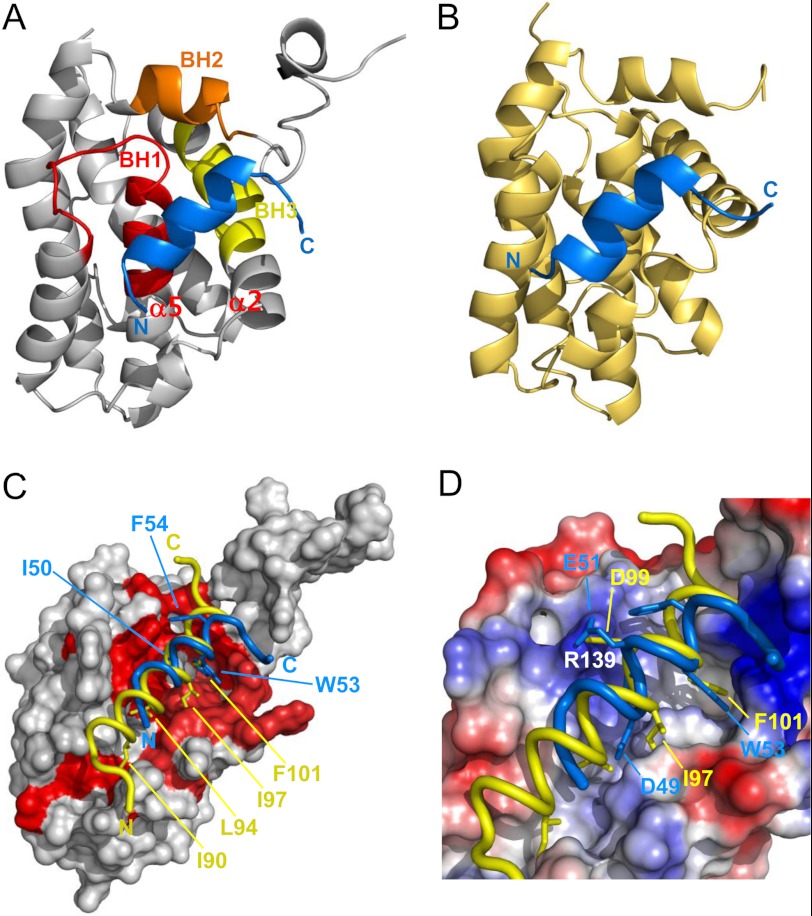

FIGURE 2.

Binding of p53TAD2 to diverse anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. A, overlaid two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra for 15N-labeled Bcl-XL, Bcl-2, and Bcl-w in the absence (blue) or presence (red) of p53TAD2 peptide. Binding site mapping of p53TAD2 on the structures (B) and molecular surfaces (C) of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. The residues of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins showing chemical shift changes of ΔCS > 0.08 ppm and the disappeared residues are colored in red. The residues showing the chemical shift changes of 0.03 ppm < ΔCS < 0.08 ppm are colored in yellow.

Competitive Binding Mechanism for Bcl-XL between p53TAD1 and p53TAD2

Based on similarity in the chemical shift perturbation profiles in the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins between p53TAD1 and p53TAD2, we postulated that p53TAD2 can bind to the same site in anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins in an analogous manner to p53TAD1. We have tested this hypothesis by performing a two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC NMR competition experiment in which 15N-labeled p53TAD (L22A/W23A) mutant·Bcl-XL complex was titrated with p53TAD1 peptide (Fig. 3A). When a large excess of p53TAD1 peptide was added, the weakened NMR resonances of p53TAD2 (e.g. Asp-49, Ile-50, Gln-52, Trp-53, and Phe-54) were recovered at the position of the unbound mutant p53TAD. This result indicates that binding of p53TAD1 and p53TAD2 to Bcl-XL is mutually exclusive, and thus p53TAD1 and p53TAD2 can compete directly for the same binding site in Bcl-XL. Furthermore, we tested whether a p53TAD-mimetic small molecule Nutlin-3 can also block the p53TAD2/Bcl-XL interaction by acquiring two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectrum with 1 mm Nutlin-3 added to the p53TAD (L22A/W23A) mutant·Bcl-XL complex (Fig. 3B). Noticeably, the HSQC spectrum in the presence of Nutlin-3 closely resembles that of the unbound p53TAD mutant, indicating that Nutlin-3 effectively blocks the interaction between p53TAD2 and Bcl-XL. Because Nutlin-3 specifically binds to the hydrophobic cleft of Bcl-XL (19), its disruption of the binding of p53TAD2 to Bcl-XL indicates that the hydrophobic cleft of Bcl-XL is also the binding site for p53TAD2 as well as p53TAD1. This result supports a competitive binding mechanism for Bcl-XL between p53TAD1 and p53TAD2, which is reminiscent of a competitive MDM2-binding mode between p53TAD1 and p53TAD2 (26).

FIGURE 3.

Competitive binding between p53TAD2 and p53TAD1 to Bcl-XL. A, overlaid two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra for 0.1 mm 15N-labeled mutant p53TAD (L22A/W23A) in the free state (blue) or in the presence of 0.2 mm Bcl-XL (red) and in the presence of 0.2 mm Bcl-XL and 1 mm p53TAD1 peptide (green). B, overlaid two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra for 0.1 mm 15N-labeled mutant p53TAD (L22A/W23A) in the free state (blue) or in the presence of 0.2 mm Bcl-XL (red) and in the presence of 0.2 mm Bcl-XL and 1 mm Nutlin-3 (green).

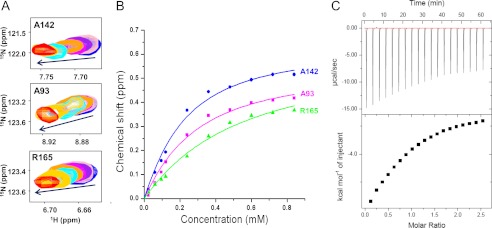

To determine the binding affinity of the p53TAD2 peptide to Bcl-XL, we measured chemical shift changes of Bcl-XL as a function of p53TAD2 peptide concentrations (Fig. 4A). Resultant NMR chemical shift perturbation values were calculated by averaging the weighted individual chemical shifts of Ala-93, Ala-142, and Arg-165 situated near the binding groove. These values were fitted to a single-site ligand-binding model using the nonlinear least square method (Fig. 4B). The dissociation constant (Kd) of the p53TAD2 peptide to Bcl-XL was determined to be 0.28 mm. The binding affinity of p53TAD2 peptide to Bcl-XL was similar to that of p53TAD1 peptide to Bcl-XL as determined by NMR (Kd = 0.26 mm) (18). In addition, ITC experiments showed that p53TAD2 binds to Bcl-XL with Kd = 0.62 mm (Fig. 4C). Therefore, it appears that p53TAD2 makes a contribution comparable with that of p53TAD1 to the formation of the p53TAD·Bcl-XL complex.

FIGURE 4.

Measurement of the binding affinity of Bcl-XL with p53TAD2 peptide. A, two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled Bcl-XL upon titration with p53TAD2 peptide (0 mm, blue; 0.12 mm, orange, 0.24 mm, cyan; 0.36 mm, yellow; and 0.48 mm, red). B, binding curves for the NMR titration of Bcl-XL with p53TAD2 peptide. C, ITC data of a titration of Bcl-XL with p53TAD2 peptide to measure the binding affinity.

Refined Structural Models of the Complexes between p53TAD2 and Bcl-XL/Bcl-2

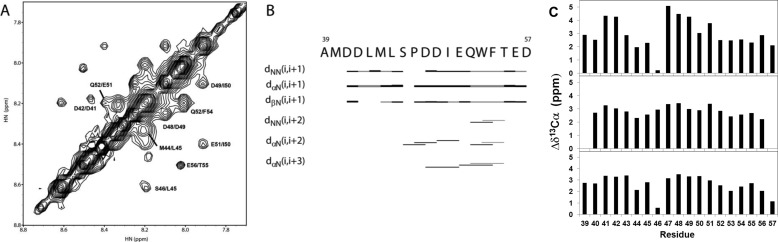

To analyze the structural characteristics of the p53TAD2 peptide in complex with the anti-apoptotic Bcl-XL, we performed NOESY experiments on the Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 complex. A summary of the short and medium range NOEs for the p53TAD2 peptide bound to Bcl-XL showed the consecutive short range NH(i)/NH(i + 1) and medium range CαH(i)/NH(i + 3) connectivities near residues Asp-48 to Phe-54 (Fig. 5, A and B). Furthermore, consecutive positive resonance shifts were observed for 13Cα atoms of p53TAD2 residues in the Bcl-XL-bound state, supporting the preference for α-helical conformation of the Bcl-XL-bound p53TAD2 (Fig. 5C). Similar secondary chemical shift effects were previously reported in the binding of p53TAD2 to CBP Kix domain, human RPA70 and PC4 (27–29). Taken together, the results suggest that the corresponding region in the p53TAD2 peptide adopts mainly α-helical conformation when bound to Bcl-XL, which is consistent with previous observations that the two peptide fragments of p53TAD, comprising residues 33–56 and residues 45–58, bound to replication protein A and Tfb1, respectively, to form an amphipathic α-helix.

FIGURE 5.

p53TAD2 peptide bound to Bcl-XL adopts an α-helix. A, amide proton region in the two-dimensional 1H-1H transferred NOESY spectrum of p53TAD2 peptide in the presence of Bcl-XL. B, summary of the short and medium range NOEs for p53TAD2 peptide in the presence of Bcl-XL. The thickness of the bar represents the relative intensity of NOEs (strong or weak), and the gray bar indicates ambiguous NOE due to overlap. C, 13Cα shifts calculated by subtracting standard random coil values from the experimental 13Cα chemical shifts. Three different random coil values from Schwarzinger et al. (46) (top panel), Tamiola et al. (47) (middle panel), and Zhang et al. (48) (bottom panel) are used, and residues 39–57 are shown for clarity. The HNCA spectrum was acquired at 5 °C with 0.3 mm p53TAD in the presence of 0.3 mm Bcl-XL in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT.

Because the Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 complex was in the fast to intermediate exchange on the NMR chemical shift time scale and suffered severe line broadening for the majority of interfacial resonances, it was difficult to find unambiguous intermolecular NOEs between the Bcl-XL and p53TAD2 peptide with isotope-filtered NOESY experiments. Because of these experimental limitations, we were not able to determine the NMR structure of the Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 complex only by the intermolecular NOEs. Thus, we calculated refined structural models for the complexes between Bcl-XL/Bcl-2 and p53TAD2 peptide by using the HADDOCK 2.0 program (Table 1), mainly based on the chemical shift perturbation data that were sufficient as experimental restraints in NMR data-driven docking calculation. As shown in Fig. 6, the p53TAD2 peptide binds to the predominantly hydrophobic groove surrounded by the BH1, BH2, and BH3 domains of Bcl-XL or Bcl-2. Within this binding pocket, the p53TAD2 peptide is surrounded by the hydrophobic side chains of Phe-97, Leu-130, Val-141, Ala-142, and Tyr-195 of Bcl-XL or Phe-104, Tyr-108, Phe-112, Met-115, Leu-137, and Ala-149 of Bcl-2. The overall structure of the Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 complex is essentially the same as that of the Bcl-2·p53TAD2 complex (Fig. 6, A and B), suggesting a highly conserved binding mechanism of the p53TAD2 with the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family members.

FIGURE 6.

Refined structural models of p53TAD2 in complex with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. The best energy structural models of Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 (A) and Bcl-2·p53TAD2 complexes (B) are shown. Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 proteins are colored gray and yellow, respectively, and p53TAD2 peptide is colored blue. The BH1, BH2, and BH3 motifs of Bcl-XL are labeled. C and D, structural comparison of the Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 peptide complex with the Bcl-XL·Bim BH3 peptide complex (PDB code 3FDL). p53TAD2 and Bim BH3 peptides are colored blue and yellow, respectively. Chemical shift perturbations of Bcl-XL induced by p53TAD2 peptide are mapped onto the molecular surface of Bcl-XL (red) (C). Positive and negative electrostatic potentials are colored in blue and red, respectively (D).

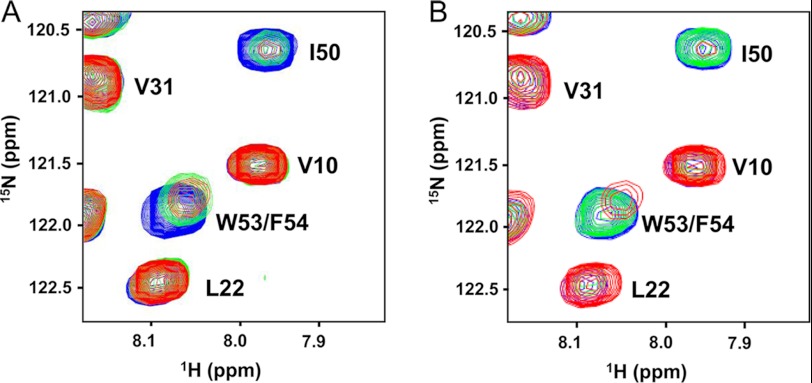

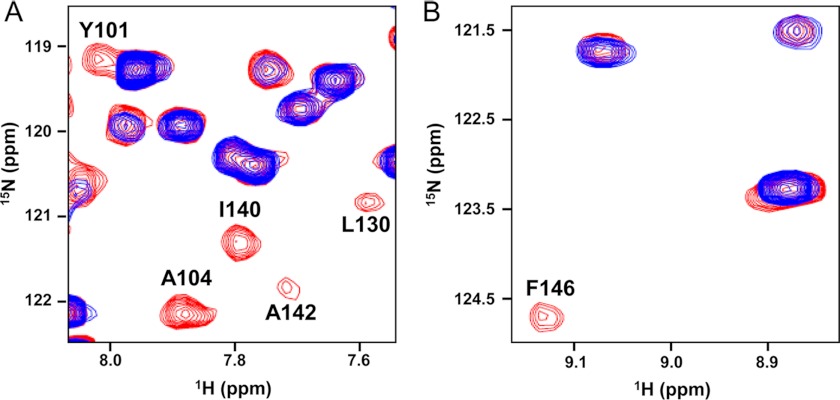

To further confirm the binding orientation of p53TAD2 peptide to Bcl-XL, we carried out PRE NMR experiments. The two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled Bcl-XL were acquired in the presence of MTSL-derivatized Cys-p53TAD2 peptide in the oxidized and reduced state (Fig. 7). We observed a specific paramagnetic broadening effect on the backbone amide resonances of the Bcl-XL residues that are mainly located in α2 and α5 helices (e.g. Tyr-101, Ala-104, Leu-130, Ile-140, Ala-142, and Phe-146) (Fig. 6A). This result indicates that the N terminus of the p53TAD2 peptide orients toward the α2 and α5 helices of Bcl-XL. The disappeared cross-peaks of the Bcl-XL residues recovered after addition of ascorbic acid, indicating that the intensity loss of the cross-peaks was caused specifically by paramagnetic MTSL spin label. Thus, the PRE experiments confirmed the orientation of the p53TAD2 peptide to Bcl-XL.

FIGURE 7.

PRE-NMR analysis of Bcl-XL by paramagnetically labeled p53TAD2 peptide. The two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra for 15N-labeled Bcl-XL in the presence of equimolar MTSL-labeled Cys-p53TAD2 were acquired in the oxidized (blue) and reduced (red) state. Two different regions of the overlaid two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra are shown in A and B.

Structural Basis for Transcription-independent Apoptotic Regulation of p53TAD

A refined structural model of the Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 peptide complex is reminiscent of the previously determined structures of complexes between Bcl-XL and pro-apoptotic BH3 peptides of Bak, Bad, and Bim, where the pro-apoptotic BH3 peptides bind to Bcl-XL via hydrophobic interactions of the BH3 peptide side chains in four discrete sub-binding sites (i, i + 4, i + 7, and i + 11 sites occupied by side chains of Ile-90, Leu-94, Ile-97, and Phe-101 in Bim BH3 peptide, respectively) within the binding groove (30). A structural comparison between Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 peptide and Bcl-XL·Bim BH3 peptide complexes revealed that the p53TAD2 peptide binds to anti-apoptotic Bcl-XL via a mechanism that is similar to that of the pro-apoptotic Bim BH3 peptide (Fig. 6C). Among the four sub-binding sites for hydrophobic residues observed in the Bcl-XL·Bim BH3 complex, p53TAD2 peptide occupies two of them (i + 7 and i + 11 sites). In particular, the Trp-53 ring moiety of p53TAD2 is very well superimposed with the Phe-101 ring of Bim BH3 peptide. In contrast, the aromatic ring of Phe-54 in p53TAD2 contacts the Bcl-XL via the sites other than the i, i + 4, i + 7, and i + 11 sites. This complex model indicates that Glu-51 in p53TAD2 could form a salt bridge with Arg-139 in Bcl-XL like Asp-99 in the Bak BH3 peptide (Fig. 6D). Consequently, despite the differences of the recognition of the hydrophobic residues, the binding sites occupied by p53TAD2 in Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 overlap well with those occupied by the pro-apoptotic BH3 peptides of Bim, Bak, and Bad, indicating that their binding to Bcl-XL or Bcl-2 is mutually exclusive. Therefore, it seems that, like p53TAD1 peptide, the p53TAD2 peptide should compete with the pro-apoptotic BH3 peptides to occupy the same binding site in Bcl-XL or Bcl-2. This suggests that p53TAD2 as well as p53TAD1 are involved in the transcription-independent apoptotic regulation.

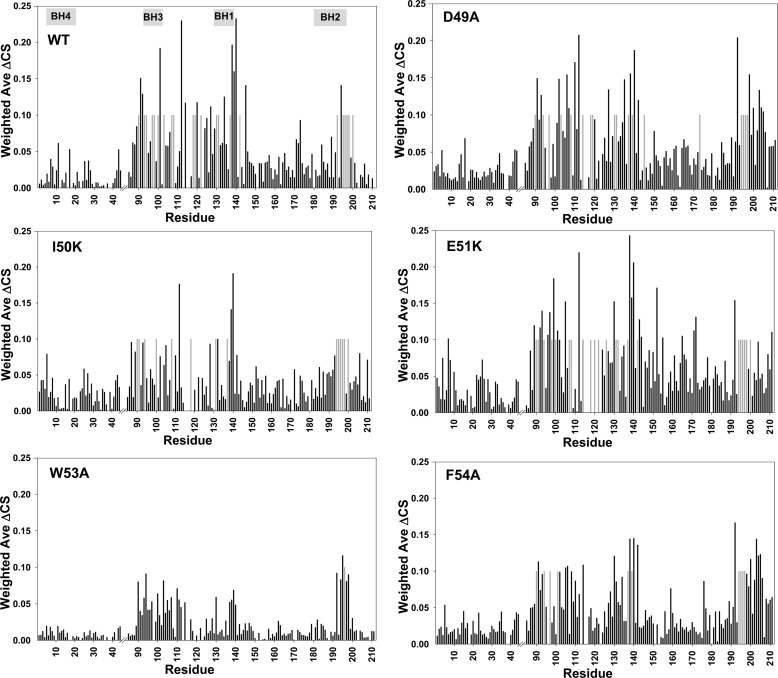

Mutational Analysis on the Interaction between p53TAD2 and Bcl-XL

To further validate our structural model of the Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 complex, we conducted NMR binding experiments of Bcl-XL with mutant p53TAD2 peptides. For this, we introduced D49A, I50K, E51K, W53A, and F54A mutations into the highly conserved ΦXXΦΦ motif, as well as into the charged residues in the p53TAD2 peptide. The I50K and F54A mutations weakened, and the W53A mutation substantially reduced chemical shift perturbations of Bcl-XL seen in the presence of the wild-type p53TAD2 peptide (Fig. 8), indicating that the I50K and F54A mutations weakened, and the W53A mutation significantly impaired the binding of p53TAD2 peptide to Bcl-XL. The most deleterious effect of the W53A mutation on Bcl-XL binding is fully consistent with the structural model, where Trp-53 makes the most significant contribution to complex formation with Bcl-XL. However, D49A and E51K mutations in p53TAD2 had negligible effects on NMR chemical shift perturbations. For the interaction with Bcl-XL, one subtle difference between p53TAD2 and Bim BH3 peptides lies in the character of the inter-molecular interactions; in addition to hydrophobic interactions, an electrostatic interaction contributes significantly to the binding of Bcl-XL to Bim BH3 peptide but not to p53TAD2 peptide. Our results from analysis of the complex structural model as well as our mutagenesis data collectively showed that the positionally conserved hydrophobic residues Ile-50, Trp-53, and Phe-54 in the ΦXXΦΦ motif of p53TAD2 are key determinants for binding to Bcl-XL.

FIGURE 8.

Mutational analysis on the interaction between p53TAD2 and Bcl-XL. Chemical shift perturbations on the Bcl-XL residues by binding of wild-type and mutant p53TAD2 peptides (D49A, I50K, E51K, W53A, and F54A). Weighted ΔCS values were plotted against the residue number of Bcl-XL. Resonances that disappeared upon binding are shown as gray bars.

Close Mimicry between the p53TAD2/Bcl-XL Interaction and Other p53TAD Interactions

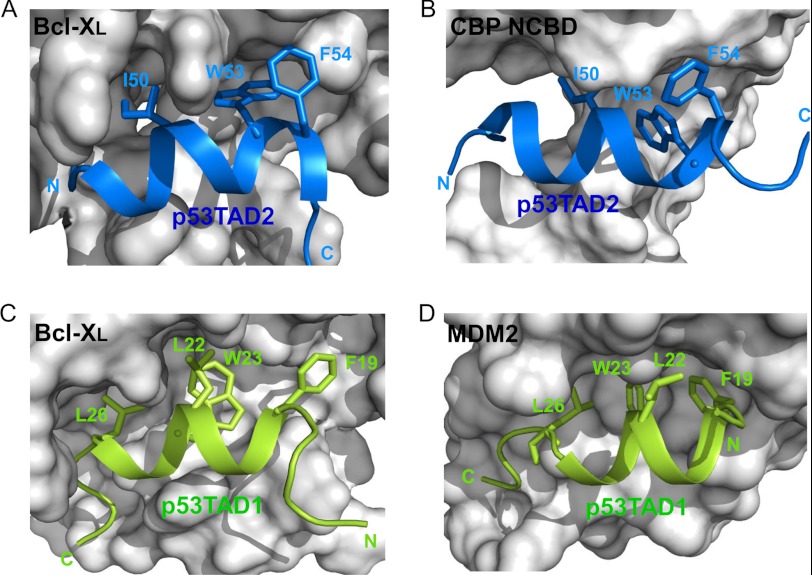

As observed with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, both the p53TAD1 and p53TAD2 motifs are involved in the binding of p53TAD to MDM2 (6, 31), CBP/p300 (29, 32–35), human mitochondrial single-stranded DNA-binding protein (HmtSSB) (36), and human mitochondrial transcription factor A (37). To elucidate the target binding mode of the dual p53TAD motifs, we compared the structures of the Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 complex with the previously determined Bcl-XL·p53TAD1 (18), MDM2·p53TAD1 (6), and CBP nuclear receptor coactivator binding domain (NCBD)·p53TAD2 complexes (Fig. 9) (33). First, the overall binding mode of the p53TAD2 peptide with anti-apoptotic Bcl-XL/Bcl-2 is quite analogous to that of the p53TAD1 peptide with these same proteins, although they display opposite orientation. The amphipathic α-helices of p53TAD1 and p53TAD2 peptides were also seen in p53TAD·MDM2 or p53TAD·CBP complex formation (6, 19). Second, there is a noticeable structural homology in the key binding determinants in the conserved ΦXXΦΦ motif. Similar to Phe-19, Leu-22, Trp-23, and Leu-26 (the first three constituting the ΦXXΦΦ motif) in the p53TAD1 peptide bound to Bcl-XL and MDM2, the residues Ile-50, Trp-53, and Phe-54 in the p53TAD2 peptide, align in one face of the amphipathic α-helix, point into the long hydrophobic groove of Bcl-XL and CBP NCBD, and form hydrophobic inter-molecular interactions. In particular, as found in Trp-23 of p53TAD1, the aromatic ring of Trp-53 in p53TAD2 fits snugly into the hydrophobic binding pocket, which makes the largest contribution to stabilization of the complex. Overall, the way p53TAD1 or p53TAD2 interacts with Bcl-XL in the transcription-independent p53 apoptotic pathway mimics what was observed in their binding to MDM2 or CBP NCBD in the transcription-dependent p53 apoptotic pathway, despite the distinct difference in the global folds of these target proteins.

FIGURE 9.

Mimicry in the dual site recognition of Bcl-XL, MDM2, and CBP by p53TAD. Structural models of the Bcl-XL·p53TAD2 (A) and Bcl-XL·p53TAD1 (C) complexes were compared with the previously reported structures of CBP NCBD·p53TAD2 (PDB code 2L14) (B) and MDM2·p53TAD1 (PDB code 1YCR) (D) complexes, respectively. The p53TAD1 and p53TAD2 peptides are drawn as green and blue ribbon models, respectively, and the ΦXXΦΦ motif residues involved in binding are labeled.

DISCUSSION

p53 is a multifunctional protein that acts through the interaction of its p53TAD with various proteins. The p53TAD contains two structurally homologous ΦXXΦΦ motifs, referred to as p53TAD1 and p53TAD2. Although structurally disordered, p53TAD1 and p53TAD2 show versatile molecular interactions with multiple partners involved in key biological pathways such as the transcriptional activation, DNA repair, and apoptosis. However, there is a noticeable difference in specificity between the two binding motifs; p53TAD1 is necessary and sufficient for tight binding with TBP in TFIID (38) and human TAFII31 (39), whereas p53TAD2 is crucial for binding of p53TAD with replication protein A (40), BRCA2 (41), p62/Tfb1 in TFIIH (42), and positive cofactor 4 (PC4) (27). In contrast, p53TAD binds to MDM2 and to the Taz2 (32, 34), Kix (29), or NCBD (33) domains of CBP/p300 through both the p53TAD1 and p53TAD2 motifs (Fig. 9).

In addition to its transcriptional activity, p53 exerts an apoptogenic activity in a transcription-independent manner. In our previous studies, it was revealed that the p53 interacts with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins via p53TAD1 (17, 18). Our present biochemical and structural data showed that p53TAD2 alone, independently of p53TAD1, can bind to the same BH3 peptide-binding groove in the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins such as Bcl-XL and Bcl-2 in a similar manner to that of p53TAD1. Thus, p53TAD2 could function as a second binding site for the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. Because their binding sites on the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins are well overlapped with those for pro-apoptotic Bak/Bax, the interaction of p53TAD1 or p53TAD2 with the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins could induce transcription-independent apoptosis at the mitochondria, which could be an alternative way of regulating the function of Bcl-2 family proteins.

In this study, our results showed a competitive Bcl-XL-binding mechanism between p53TAD2 and p53TAD1. These results are very consistent with the recent observation of a competitive MDM2-binding mechanism between p53TAD2 and p53TAD1 (26). The detailed comparison between the p53TAD2/Bcl-XL interaction and the p53TAD2/MDM2 interaction reveals that the competitive binding mechanism is highly conserved as follows. 1) The same two binding motifs, p53TAD1 and p53TAD2, are employed for interaction. 2) The binding mode of p53TAD2 closely resembles that of p53TAD1, although the orientations of the peptides are opposite on Bcl-XL. 3) The binding of p53TAD2 and p53TAD1 is competitive, and their binding can be blocked by the p53TAD-mimetic antagonist Nutlin-3. This similarity suggests that the dual p53TAD motifs may act as modulators for regulation of MDM2/MDMX proteins and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins in a similar manner. In particular, it is noteworthy to find a close mimicry in the binding mode of p53TAD1 and p53TAD2 with multiple binding partners from divergent p53 pathways (Bcl-XL/Bcl-2, CBP/p300, and MDM2/MDMX). Taken together, our results suggest that the dual-site interaction of p53TAD represents a highly conserved mechanism underlying the p53 recognition of MDM2/MDMX and CBP/p300 in the transcription-dependent p53 apoptotic pathway as well as of Bcl-2/Bcl-XL in the transcription-independent p53 apoptotic pathway.

Therefore, what could be the biological role for such tandemly positioned dual binding motifs of p53TAD? First possibility may be that the dual binding motifs capable of binding to the same site may work in a cooperative manner to enhance binding affinity. For example, the recruitment of transcriptional coactivators by nuclear receptors during the transcription initiation is facilitated by multiple binding motifs of nuclear receptor coactivators (43, 44). Similarly, by increasing local concentrations of p53TAD motifs, close location of dual binding p53TAD motifs with the same specificity is likely to aid the recruitment of binding partners. In fact, the MDM2 binding affinity of full-length p53TAD is much higher than that of p53TAD1 or p53TAD2, suggesting the presence of binding cooperativity between them (26). In particular, the tandemly linked dual motifs in p53TAD may be more effective for competing with a singular BH3 motif of pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins for binding to the same site of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2/Bcl-XL. Second, the dual binding motifs of p53TAD could be recognized by the two distinct sites of a single binding partner. Both p53TAD1 and p53TAD2 simultaneously bind to the two distinct sites in the CBP NCBD domain (33). Finally, two distinct binding motifs may be important for cooperative regulation of multifunctional p53. For example, the p53TAD1 and p53TAD2 motifs can bind simultaneously to two distinct binding partners, MDM2 and CBP/p300 domains to form a ternary complex, where MDM2 and CBP/p300 function synergistically to regulate the p53 pathway (45). Therefore, the dual binding motifs of p53TAD may play an important regulatory role in the p53 pathway first by facilitating the recruitment of binding partners; second, by providing co-recognition sites for this binding, and finally, by forming a ternary complex with different target proteins for cooperative regulation of p53.

In summary, we have discovered the competitive binding mechanism by p53TAD2 and p53TAD1 for regulating anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. Our refined structural models revealed a close mimicry in the dual site interactions of p53TAD with the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, CBP/p300 and MDM2, in divergent apoptotic p53 pathways. Our results provide structural insights into the transcription-independent apoptosis mechanism of p53, thus further contributing to our understanding of the pleiotropic role of p53.

Acknowledgment

We thank Eun-Hee Kim for help with the NMR data collection and Dr. Eunha Hwang for use of the Auto-iTC200 Microcalorimeter at Korea Basic Science Institute. This study made use of the NMR facility at Korea Basic Science Institute, which is supported by Advanced MR Technology Program of the Korean Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (T32221).

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (No. 2011–0016011).

- MDM2

- mouse double minute 2

- Bcl-2

- B-cell lymphoma 2

- BH

- Bcl-2 homology

- TAD

- transactivation domain

- NTD

- N-terminal domain

- DBD

- DNA-binding domain

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- NOESY

- nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy

- TOCSY

- total correlation spectroscopy

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- PRE

- paramagnetic relaxation enhancement

- MTSL

- methane thiosulfonate

- CBP

- cAMP-response element-binding protein-binding protein

- NCBD

- nuclear receptor coactivator binding domain

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank.

REFERENCES

- 1. Harris S. L., Levine A. J. (2005) The p53 pathway: positive and negative feedback loops. Oncogene 24, 2899–2908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sherr C. J. (2004) Principles of tumor suppression. Cell 116, 235–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vogelstein B., Lane D., Levine A. J. (2000) Surfing the p53 network. Nature 408, 307–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hollstein M., Sidransky D., Vogelstein B., Harris C. C. (1991) p53 mutations in human cancers. Science 253, 49–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Venot C., Maratrat M., Sierra V., Conseiller E., Debussche L. (1999) Definition of a p53 transactivation function-deficient mutant and characterization of two independent p53 transactivation subdomains. Oncogene 18, 2405–2410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kussie P. H., Gorina S., Marechal V., Elenbaas B., Moreau J., Levine A. J., Pavletich N. P. (1996) Structure of the MDM2 oncoprotein bound to the p53 tumor suppressor transactivation domain. Science 274, 948–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chipuk J. E., Bouchier-Hayes L., Kuwana T., Newmeyer D. D., Green D. R. (2005) PUMA couples the nuclear and cytoplasmic proapoptotic function of p53. Science 309, 1732–1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chipuk J. E., Kuwana T., Bouchier-Hayes L., Droin N. M., Newmeyer D. D., Schuler M., Green D. R. (2004) Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science 303, 1010–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jiang P., Du W., Heese K., Wu M. (2006) The Bad guy cooperates with good cop p53: Bad is transcriptionally up-regulated by p53 and forms a Bad/p53 complex at the mitochondria to induce apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 9071–9082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leu J. I., Dumont P., Hafey M., Murphy M. E., George D. L. (2004) Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of a Bak-Mcl1 complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 443–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mihara M., Erster S., Zaika A., Petrenko O., Chittenden T., Pancoska P., Moll U. M. (2003) p53 has a direct apoptogenic role at the mitochondria. Mol. Cell 11, 577–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tomita Y., Marchenko N., Erster S., Nemajerova A., Dehner A., Klein C., Pan H., Kessler H., Pancoska P., Moll U. M. (2006) WT p53, but not tumor-derived mutants, bind to Bcl2 via the DNA binding domain and induce mitochondrial permeabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8600–8606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sot B., Freund S. M., Fersht A. R. (2007) Comparative biophysical characterization of p53 with the pro-apoptotic BAK and the anti-apoptotic BCL-xL. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29193–29200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hagn F., Klein C., Demmer O., Marchenko N., Vaseva A., Moll U. M., Kessler H. (2010) BclxL changes conformation upon binding to wild-type but not mutant p53 DNA binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3439–3450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chipuk J. E., Maurer U., Green D. R., Schuler M. (2003) Pharmacologic activation of p53 elicits Bax-dependent apoptosis in the absence of transcription. Cancer Cell 4, 371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sayan B. S., Sayan A. E., Knight R. A., Melino G., Cohen G. M. (2006) p53 is cleaved by caspases generating fragments localizing to mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13566–13573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Xu H., Tai J., Ye H., Kang C. B., Yoon H. S. (2006) The N-terminal domain of tumor suppressor p53 is involved in the molecular interaction with the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-Xl. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 341, 938–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu H., Ye H., Osman N. E., Sadler K., Won E. Y., Chi S. W., Yoon H. S. (2009) The MDM2-binding region in the transactivation domain of p53 also acts as a Bcl-X(L)-binding motif. Biochemistry 48, 12159–12168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ha J. H., Won E. Y., Shin J. S., Jang M., Ryu K. S., Bae K. H., Park S. G., Park B. C., Yoon H. S., Chi S. W. (2011) Molecular mimicry-based repositioning of nutlin-3 to anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 1244–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bharatham N., Chi S. W., Yoon H. S. (2011) Molecular basis of Bcl-X(L)-p53 interaction: insights from molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS One 6, e26014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Petros A. M., Medek A., Nettesheim D. G., Kim D. H., Yoon H. S., Swift K., Matayoshi E. D., Oltersdorf T., Fesik S. W. (2001) Solution structure of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 3012–3017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Denisov A. Y., Madiraju M. S., Chen G., Khadir A., Beauparlant P., Attardo G., Shore G. C., Gehring K. (2003) Solution structure of human BCL-w: modulation of ligand binding by the C-terminal helix. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 21124–21128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Battiste J. L., Wagner G. (2000) Utilization of site-directed spin labeling and high-resolution heteronuclear nuclear magnetic resonance for global fold determination of large proteins with limited nuclear overhauser effect data. Biochemistry 39, 5355–5365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dominguez C., Boelens R., Bonvin A. M. (2003) HADDOCK: a protein-protein docking approach based on biochemical or biophysical information. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 1731–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laskowski R. A., Rullmannn J. A., MacArthur M. W., Kaptein R., Thornton J. M. (1996) AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 8, 477–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shan B., Li D. W., Brüschweiler-Li L., Brüschweiler R. (2012) Competitive binding between dynamic p53 transactivation subdomains to human MDM2 protein: implications for regulating the p53·MDM2/MDMX interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30376–30384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rajagopalan S., Andreeva A., Teufel D. P., Freund S. M., Fersht A. R. (2009) Interaction between the transactivation domain of p53 and PC4 exemplifies acidic activation domains as single-stranded DNA mimics. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 21728–21737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vise P. D., Baral B., Latos A. J., Daughdrill G. W. (2005) NMR chemical shift and relaxation measurements provide evidence for the coupled folding and binding of the p53 transactivation domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 2061–2077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee C. W., Arai M., Martinez-Yamout M. A., Dyson H. J., Wright P. E. (2009) Mapping the interactions of the p53 transactivation domain with the KIX domain of CBP. Biochemistry 48, 2115–2124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee E. F., Sadowsky J. D., Smith B. J., Czabotar P. E., Peterson-Kaufman K. J., Colman P. M., Gellman S. H., Fairlie W. D. (2009) High-resolution structural characterization of a helical α/β-peptide foldamer bound to the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 48, 4318–4322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chi S. W., Lee S. H., Kim D. H., Ahn M. J., Kim J. S., Woo J. Y., Torizawa T., Kainosho M., Han K. H. (2005) Structural details on mdm2-p53 interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38795–38802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Feng H., Jenkins L. M., Durell S. R., Hayashi R., Mazur S. J., Cherry S., Tropea J. E., Miller M., Wlodawer A., Appella E., Bai Y. (2009) Structural basis for p300 Taz2-p53 TAD1 binding and modulation by phosphorylation. Structure 17, 202–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee C. W., Martinez-Yamout M. A., Dyson H. J., Wright P. E. (2010) Structure of the p53 transactivation domain in complex with the nuclear receptor coactivator binding domain of CREB-binding protein. Biochemistry 49, 9964–9971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arai M., Ferreon J. C., Wright P. E. (2012) Quantitative analysis of multisite protein-ligand interactions by NMR: binding of intrinsically disordered p53 transactivation subdomains with the TAZ2 domain of CBP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3792–3803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jenkins L. M., Yamaguchi H., Hayashi R., Cherry S., Tropea J. E., Miller M., Wlodawer A., Appella E., Mazur S. J. (2009) Two distinct motifs within the p53 transactivation domain bind to the Taz2 domain of p300 and are differentially affected by phosphorylation. Biochemistry 48, 1244–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wong T. S., Rajagopalan S., Townsley F. M., Freund S. M., Petrovich M., Loakes D., Fersht A. R. (2009) Physical and functional interactions between human mitochondrial single-stranded DNA-binding protein and tumour suppressor p53. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 568–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wong T. S., Rajagopalan S., Freund S. M., Rutherford T. J., Andreeva A., Townsley F. M., Petrovich M., Fersht A. R. (2009) Biophysical characterizations of human mitochondrial transcription factor A and its binding to tumor suppressor p53. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 6765–6783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chang J., Kim D. H., Lee S. W., Choi K. Y., Sung Y. C. (1995) Transactivation ability of p53 transcriptional activation domain is directly related to the binding affinity to TATA-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 25014–25019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Uesugi M., Verdine G. L. (1999) The α-helical FXXΦΦ motif in p53: TAF interaction and discrimination by MDM2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 14801–14806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bochkareva E., Kaustov L., Ayed A., Yi G. S., Lu Y., Pineda-Lucena A., Liao J. C., Okorokov A. L., Milner J., Arrowsmith C. H., Bochkarev A. (2005) Single-stranded DNA mimicry in the p53 transactivation domain interaction with replication protein A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15412–15417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rajagopalan S., Andreeva A., Rutherford T. J., Fersht A. R. (2010) Mapping the physical and functional interactions between the tumor suppressors p53 and BRCA2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 8587–8592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Di Lello P., Jenkins L. M., Jones T. N., Nguyen B. D., Hara T., Yamaguchi H., Dikeakos J. D., Appella E., Legault P., Omichinski J. G. (2006) Structure of the Tfb1/p53 complex: Insights into the interaction between the p62/Tfb1 subunit of TFIIH and the activation domain of p53. Mol. Cell 22, 731–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Acevedo M. L., Lee K. C., Stender J. D., Katzenellenbogen B. S., Kraus W. L. (2004) Selective recognition of distinct classes of coactivators by a ligand-inducible activation domain. Mol. Cell 13, 725–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kumar R., Thompson E. B. (2003) Transactivation functions of the N-terminal domains of nuclear hormone receptors: protein folding and coactivator interactions. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ferreon J. C., Lee C. W., Arai M., Martinez-Yamout M. A., Dyson H. J., Wright P. E. (2009) Cooperative regulation of p53 by modulation of ternary complex formation with CBP/p300 and HDM2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6591–6596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schwarzinger S., Kroon G. J., Foss T. R., Chung J., Wright P. E., Dyson H. J. (2001) Sequence-dependent correction of random coil NMR chemical shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 2970–2978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tamiola K., Acar B., Mulder F. A. (2010) Sequence-specific random coil chemical shifts of intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 18000–18003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang H., Neal S., Wishart D. S. (2003) RefDB: a database of uniformly referenced protein chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR 25, 173–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fernández-Recio J., Totrov M., Abagyan R. (2004) Identification of protein-protein interaction sites from docking energy landscapes. J. Mol. Biol. 335, 843–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]