Abstract

The cell wall integrity (CWI) pathway of the model organism Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been thoroughly studied as a paradigm of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. It consists of a classic MAPK module comprising the Bck1 MAPK kinase kinase, two redundant MAPK kinases (Mkk1 and Mkk2), and the Slt2 MAPK. This module is activated under a variety of stimuli related to cell wall homeostasis by Pkc1, the only member of the protein kinase C family in budding yeast. Quantitative phosphoproteomics based on stable isotope labeling of amino acids in cell culture is a powerful tool for globally studying protein phosphorylation. Here we report an analysis of the yeast phosphoproteome upon overexpression of a PKC1 hyperactive allele that specifically activates CWI MAPK signaling in the absence of external stimuli. We found 82 phosphopeptides originating from 43 proteins that showed enhanced phosphorylation in these conditions. The MAPK S/T-P target motif was significantly overrepresented in these phosphopeptides. Hyperphosphorylated proteins provide putative novel targets of the Pkc1–cell wall integrity pathway involved in diverse functions such as the control of gene expression, protein synthesis, cytoskeleton maintenance, DNA repair, and metabolism. Remarkably, five components of the plasma-membrane-associated protein complex known as eisosomes were found among the up-regulated proteins. We show here that Pkc1-induced phosphorylation of the eisosome core components Pil1 and Lsp1 was not exerted directly by Pkc1, but involved signaling through the Slt2 MAPK module.

Signal transduction pathways are the key to orchestrating cellular responses upon challenge by environmental stimuli. Among the signaling modules most commonly found in eukaryotic cells are mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)1 cascades, which convey signals via sequential phosphorylation. MAPK modules couple to upstream activating kinases that respond to local GTPase activation, generally as a consequence of ligand–receptor interactions. Such networks have been studied in depth in the past decades, and a great deal of information has emerged from the exhaustive study of lower eukaryotic model organisms such as the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (1, 2). The most thoroughly studied MAPK pathways in S. cerevisiae are the mating pheromone pathway involving the Kss1 and Fus3 Erk-like MAPKs, the high osmotic glycerol response pathway mediated by the p38 MAPK ortholog Hog1, and the cell wall integrity (CWI) pathway mediated by the Erk5-like Slt2 (3). Approaches intended to globally address the effects of the activation of these pathways have been undertaken extensively at the level of gene expression (4–6). Only recently have advances in MS-based proteomics and their application in quantitatively addressing post-translational modifications (7–9) been used to study yeast MAPK signaling. Such large-scale studies have led to valuable datasets on protein phosphorylation dependent on the mating pheromone (10–12) and high osmotic glycerol pathways (13).

The CWI pathway responds to aggression against the cell wall, alterations of actin-driven morphogenesis, and hypotonic, oxidative, and heat stresses, among other stimuli. It is also naturally activated at certain stages of the budding cycle and during mating (14–16). This pathway consists of a MAPK module comprising the Bck1 MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK), two redundant MAPK kinases (MAPKKs) (Mkk1 and Mkk2), and the Slt2 MAPK, all under the control of a master upstream kinase, Pkc1, reminiscent of mammalian protein kinase C (17). Pkc1 activation requires its association at the plasma membrane to the Rho1 small GTPase in its GTP-bound form (18), which is a hub for exocytosis, actin polarization, and cell wall glucan synthesis. In addition, Pkc1 relies on activation by the redundant Pkh1 and Pkh2 kinases, the yeast orthologs of mammalian PDK1 (19, 20). Pkc1 accomplishes functions different from those related to activation of the CWI pathway, as deduced from the fact that the PKC1 gene is essential for yeast cells, whereas components of the CWI pathway downstream of Pkc1 are dispensable in the absence of cell wall damage (16). For example, Pkc1 promotes actin depolarization in response to cell wall stress in order to temporarily arrest growth and allow adaptation, a function that does not involve the MAPK module (21). However, there is limited evidence related to direct substrates of Pkc1 other than the MAPKKK Bck1 (22). Similarly, only a few Slt2 direct phosphorylation targets besides its downstream transcription factors have been described, despite the involvement of this MAPK in multiple cellular functions. Known Slt2 substrates include Rlm1 (23), which mediates the bulk of Slt2-driven expression of cell-wall-related genes, and the cell cycle transcriptional regulator SBF (composed of Swi4p and Swi6p) (24). The transcriptional silencing protein Sir3 also has been reported to be phosphorylated by Slt2 (25). Other reported substrates are components of the CWI pathway, such as the protein phosphatase Msg5 (26), the Rho1-GDP-GTP exchange factor Rom2, and the Mkk1 and Mkk2 MAPKKs, which are phosphorylated by Slt2 for feedback regulation (27, 28).

In this study, we followed a quantitative phosphoproteomic approach in order to find novel putative phosphorylation targets of either Pkc1 or the CWI kinases downstream. We report the use of stable isotope labeling of amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) (9) coupled to phosphopeptide enrichment (29) and high-resolution MS to quantitatively detect changes in the phosphoproteome caused by activation of the CWI pathway. To specifically activate this route, we endogenously overproduced a hyperactive version of Pkc1 instead of using stimuli such as temperature, actin depolarization, or cell wall aggression that could promote the concomitant activation of other stress responses. From among the differentially phosphorylated proteins found in our dataset, we chose the eisosome components Lsp1 and Pil1 for the validation of our approach. We confirmed that these proteins become phosphorylated upon Pkc1 hyperactivation in an Slt2-dependent manner.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains, Media, and Growth Conditions

The S. cerevisiae strains used are listed in Table I. E. coli DH5α was used for routine molecular biology techniques. YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% glucose) broth or agar was the general non-selective medium used for yeast cell growth. Synthetic dextrose medium (0.17% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 0.5% ammonium sulfate, 2% glucose, added to the appropriate amino acids and nucleic acid bases) was used to maintain selection for plasmids. In synthetic raffinose medium, the 2% glucose was replaced by 1.5% raffinose. Galactose induction in liquid medium was performed by growing cells in synthetic raffinose medium to mid-exponential phase, adding galactose to a final 2% (w/v) concentration, and incubating for 4 h. The strain MJY38 used for SILAC was constructed by means of classic genetic manipulation, crossing the Y17202 and Y00981 strains, both from the yeast whole genome deletion collection (EUROSCARF). Diploids were obtained via micromanipulation of zygotes and sporulation induced by incubation on pre-sporulation solid medium (0.8% yeast extract, 0.3% peptone, and 10% glucose) and, after 24 h, on sporulation solid medium (1% potassium acetate). Ten tetrads were micromanipulated and haploid segregants were tested for Arg, Lys, and Trp auxotrophic phenotypes on the appropriated synthetic dextrose media. From among those segregants bearing the three auxotrophies, MJY38 was selected and used for the subsequent quantitative phosphoproteomic experiments. The double pil1Δ lsp1Δ strain was obtained by first crossing the Y07338 and BY4742 strains, and then crossing a MATα lsp1Δ::kanMX4 segregant from the resulting offspring to Y06988. Eighteen tetrads from this second diploid were dissected, and from among them, one parental ditype tetrad was selected and double pil1Δ lsp1Δ segregants were isolated.

Table I. Yeast strains used in this work.

| Strain name | Genotype | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | EUROSCARF |

| BY4742 | MATα his3Δ leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | EUROSCARF |

| Y00981 | BY4741 isogenic, arg4Δ::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| Y00993 | BY4741 isogenic, slt2Δ::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| Y01328 | BY4741 isogenic, bck1Δ::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| Y03042 | BY4741 isogenic, fus3Δ::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| Y06981 | BY4741 isogenic, kss1Δ::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| Y17202 | BY4742 isogenic MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0, trp1Δ::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| Y07338 | BY4741 isogenic, lsp1Δ::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| Y06988 | BY4741 isogenic, pil1Δ::kanMX4 | EUROSCARF |

| MJY38 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 lys2Δ0 arg4Δ::kanMX4 trp1Δ::kanMX4 | This work |

| VMY1 | BY4741 isogenic, PIL1:: myc6::LEU2 | This work |

| VMY2 | BY4741 isogenic, LSP1:: myc6::LEU2 | This work |

| VMY3 | BY4741 isogenic, slt2Δ::kanMX4, PIL1:: myc6::LEU2 | This work |

| VMY4 | BY4741 isogenic, slt2Δ::kanMX4, LSP1::myc6::LEU2 | This work |

| VMY5 | BY4741 isogenic, bck1Δ::kanMX4, PIL1::myc6::LEU2 | This work |

| VMY6 | BY4741 isogenic, bck1Δ::kanMX4, LSP1::myc6::LEU2 | This work |

| VMY7 | MATα lsp1Δ::kanMX4 pil1Δ::kanMX4 ura3Δ0 his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 | This work |

| VMY8 | BY4741 isogenic SUR7-GFP::URA3 | This work |

| VMY9 | MATα lsp1Δ::kanMX4 pil1Δ::kanMX4 ura3Δ0 his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 SUR7-GFP::URA3 | This work |

DNA Manipulation and Plasmid and Recombinant Strain Construction

Transformation of E. coli and S. cerevisiae and other basic molecular biology methods were carried out using standard procedures. For the phosphoproteomic experiments, YEplac112-GAL-PKC1R398A,R405A,K406A (15) was used for GAL1-driven expression of a hyperactive allele of PKC1 (PKC1R398A,R405A,K406A). The empty YEplac112 vector (30) was transformed in parallel in the MJY38 strain as a control. Alternatively, in small-scale validation experiments, transformants of the BY4741 strain bearing the URA3-based empty vector pEG(KG) (31) (control) or the pEG(KG)-PKC1R398A,R405A,K406A plasmid, which expresses from the GAL1 promoter the hyperactive allele of PKC1 N-terminally fused to GST, were used. To construct the latter plasmid, the coding sequence of this mutant version of PKC1 was PCR-amplified with primers 5′-CCCGTCGACTCGAGATGAGTTTTTCACAATTGGAGC-3′ and 5′-CCCGTCGACTCATAAATCCAAATCATCTGGC-3′ (SalI site is in bold) using YEplac112-GAL-PKC1R398A,R405A,K406A as a template and cloned into the SalI site of the empty pEG(KG) vector. To obtain a C-terminal myc-tagged version of Pil1 and Lsp1, plasmids pRS305-Pil1–6myc and pRS305-Lsp1–6myc were constructed. PIL1 and LSP1 coding sequences were amplified with primers PIL1mycF (5′-CGGGGCCCATGCACAGAACTTACTC-3′) and PIL1mycR (5′-CGGGATCCAGCTGTTGTTTGTTGG-3′) for PIL1 and LSP1mycF (5′-CGGGGCCCACGTAACCGACAAATTAGG-3′) and LSP1mycR for LSP1 (5′-CGGGATCCGATGTTTTCAGAACCGGAG-3′) and cloned into the ApaI-BamHI site in the yeast vector pRS305–6myc, which had been generated by inserting six copies in tandem of the myc epitope into the polylinker of the integrative LEU2 pRS305 (32). ApaI and BamHI sites are in bold in the oligonucleotide sequence above. To integrate PIL1-myc6 and LSP1-myc6 in their corresponding chromosomal loci, pRS305-Pil1–6myc was linearized with EcoRV via partial digestion, and pRS305-Lsp1–6myc with SpeI. To generate myc-tagged PIL1 versions in the centromeric vector pRS315 (32), we first constructed pRS315–6myc by transferring a BamHI-SacI fragment from pRS305–6myc containing the six tandem copies of myc. The PIL1 gene was amplified using pRS316-PIL1, a kind gift from R. C. Dickson, as a template plasmid (33) and the oligonucleotides Pil1-Bam-Up (5′-CGGGATCCTACTGCGCGTCTCTTGTTG-3′) and Pil1-Bam-Lo (5′-CGGGATCCAGCTGTTGTTTGTTGGGGAA-3′) (BamHI sites are in bold). Cloning of the amplicon into the BamHI site of pRS315–6myc led to pRS315-PIL1–6myc. Site-directed mutagenesis to generate PIL1-S230A,T233A and PIL1-S230D,T233D was performed via overlapping PCR using the following pairs of oligonucleotides, respectively: STAA Lo (5′-TGGAGCGACAGGAGCGTCGTCCAATAGTTCCA-3′) and STAA Up (5′-GACGCTCCTGTCGCTCCAGGTGAAACCAGGCCT-3′); STDD Lo (5′-TGGATCGACAGGATCGTCGTCCAATAGTTCCA-3′) and STDD Up (5′-GACGATCCTGTCGATCCAGGTGAAACCAGGCCT-3′), combined with Pil1-Bam-Up and Pil1-Bam-Lo. To integrate SUR7-GFP in its corresponding chromosomal locus, plasmid YIp211SUR7GFP (34), a kind gift from W. Tanner, was linearized with Eco52I.

Western Blotting Analysis

Standard procedures were used for yeast growth and cell harvesting, as well as for the preparation of protein-containing cell-free extracts, fractionation via SDS-PAGE, and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. For cell breakage, lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA pH 8.0, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100), 50 mm NaF, 50 mm β-glycerol phosphate, 5 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 0.1 m PMSF, and protease inhibitors (Complete mini, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) were used. Monoclonal mouse anti-myc 9E10 antibodies (BAbCO, Richmond, CA) were used to detect proteins fused to the myc epitope. Rabbit anti-phospho-p44/p42 MAPK antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) were used to detect dually phosphorylated Slt2, Fus3, and Kss1. As a loading control, monoclonal mouse anti-actin antibodies (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) were used. Rabbit anti-phospho-p38 antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) were used to detect dually phosphorylated Hog1. Bound primary antibodies were revealed using anti-mouse or anti-rabbit fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies, and membranes were analyzed using an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosiences, Lincoln, NE) as the detection system.

Immunoprecipitation and Alkaline Phosphatase Treatment

Cells expressing PIL1-myc6 or LSP1-myc6 and overexpressing hyperactive PKC1R398A,R405A,K406A were grown and lysed as described above. Immunoprecipitation was performed by incubating protein extracts with anti-myc antibodies for 3 h and subsequently with Gamma Bind Plus Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) for 2 h. After being washed twice with lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA pH 8.0, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100) and twice with alkaline phosphatase buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mm MgCl2), beads were pre-incubated for 10 min at 30 °C. Immunoprecipitates were incubated with 20 units of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and either treated with 10 mm sodium orthovanadate as a phosphatase inhibitor or left untreated. The reaction was incubated for 20 min at 30 °C and stopped by the addition of SDS-sample loading buffer.

Visualization of Eisosomes via Fluorescence Microscopy

For observation of Sur7-GFP, cells from exponentially growing cultures were collected and examined with an Eclipse TE2000U microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Digital images were acquired with an Orca C4742–95-12ER charge coupled device camera and HCImage software (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). For eisosome counts, three different focal planes were taken, covering the whole cellular surface. Eisosomes of at least 10 mother cells of average size were counted per experiment.

Stable Isotope Labeling of Yeast Cells

Flasks containing 90 ml of synthetic raffinose medium with either 100 mg/l arginine and 100 mg/l lysine or 100 mg/l [13C6] arginine and 100 mg/l [13C6] lysine (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc., Andover, MA) were inoculated with MJY38 cells transformed with YEplac112 or YEplac112-GAL-PKC1R398A,R405A,K406A plasmids, respectively. Cells were grown for 16 h at 30 °C until mid-exponential phase, and 2% galactose was added for 4 h. Cultures were mixed, adding equal amounts of cells as determined by A600 measurement, and harvested at 4 °C via centrifugation. Cells were washed in cold water and centrifuged, and pellets were frozen at −80 °C.

Preparation of Yeast Protein Extracts for Phosphoproteomic Analysis

Cells were resuspended in 1 ml lysis buffer (100 mm HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 5% glycerol, 50 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mm sodium molybdate, 25 mm NaF, 15 mm EGTA, 5 mm EDTA, 0.5% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 3 mm DTT), supplemented with both extra protease (1 mm PMSF, 10 μm leupeptin, 1 nm calyculin A 50 mm, and protease inhibitor Complete mini (Roche Applied Science)) and phosphatase inhibitors (50 mm glycerol-2-phosphate, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate), and broken via the addition of glass beads and mixing in FastPrep (Bio101, Vista, CA). After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min, the supernatants were transferred to a new tube and kept at −80 °C. Protein extracts were cleaned to eliminate possible contaminants using phenol extraction. One volume of Tris-buffered phenol pH 8 was mixed with the extracts and centrifuged for 5 min. The upper layer was discarded, and an equal volume of extraction buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl pH 8.4, 20 mm KCl, 10 mm EDTA, 0.4% β-mercaptoethanol) was added; the extract was then mixed and centrifuged. The upper layer was again discarded. This extraction step was repeated twice. Proteins were then precipitated with 5 volumes of 100 mm NH4OAc in methanol at −20 °C for 30 min. The protein pellet was washed once with 100 mm NH4OAc in methanol and twice with ice-cold 80% acetone and left in acetone at −20 °C until use. The protein concentration was estimated via Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Three biological replicate samples were generated and subsequently analyzed.

SDS-PAGE Separation and In-gel Protein Digestion

One milligram of the mixed heavy/light protein sample was resuspended in SDS sample buffer and separated in 10% SDS-PAGE gels. Proteins were visualized with colloidal Coomassie Blue staining. Gels were cut into 12 to 15 slices for protein digestion. In-gel digestion was carried out as described elsewhere (35). Briefly, gel slices were cut into pieces ∼1 mm3 in size and washed with water. Proteins were reduced with 10 mm DTT in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate for 30 min at 56 °C and alkylated for 15 min at 30 °C with 55 mm iodoacetamide in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate. Acetonitrile (ACN) and vacuum centrifugation were applied to dry the gel pieces, and they were rehydrated with 12.5 ng/μl trypsin (proteomics grade; Roche Applied Science) in 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate for 45 min at 4 °C. The trypsin solution was removed, and the rehydrated gel pieces were overlaid with 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate. The digestion was done overnight at 37 °C. After digestion, the supernatant was recovered. Peptides were extracted from the gel pieces with 30% ACN and 0.1% TFA for 30 min at room temperature. The supernatant and extract were then pooled and kept at −20 °C until use. For subsequent analyses, 95% of the peptide sample was used for phosphopeptide enrichment, and 5% was separated to be directly analyzed via LC-MS/MS as a reference control for such enrichment.

In-solution Protein Digestion

Approximately 250 μg of the mixed heavy/light protein sample was re-suspended in 8 m urea. In-solution digestion was performed as reported elsewhere (36). Proteins were reduced with 5 mm DTT for 30 min at 37 °C and alkylated with 10 mm iodoacetamide for 30 min at 30 °C. Samples were diluted five times with 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate. Ten micrograms of trypsin (proteomics grade; Roche Applied Science) were added to the diluted samples, and the samples were incubated overnight at 37 °C. After digestion, the peptide solution was acidified with 1% TFA and desalted using GeLoader Tips (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) filled with POROS R3 resin (ABSciex, Framingham, MA) (37). Peptides were eluted with 50% ACN and 0.1% TFA. As in the case of in-gel digestion described above, 95% of the peptide sample was used for phosphopeptide enrichment, and 5% was separated to be directly analyzed via LC-MS/MS as a reference control for such enrichment.

Phosphopeptide Enrichment

Two strategies were applied for phosphopeptide enrichment: TiO2 enrichment (38) and sequential elution from immobilized metal affinity chromatography (SIMAC) (39). In the first strategy, peptide samples were mixed with 10 volumes of a TiO2 bead (GL Sciences, Tokyo, Japan) suspension in 80% ACN, 5% TFA, and 1 m glycolic acid and incubated with shaking for 1 h at 30 °C. The TiO2 beads were washed twice with 80% ACN and 1% TFA and once with water. Bound peptides were eluted from the beads with 0.5% NH4OH pH 10.5 for 30 min at 30 °C. Eluted peptides were dried in vacuo via centrifugal evaporation and resuspended with 1 μl formic acid and 15 μl water prior to LC-MS/MS.

In the second strategy, 15 μl immobilized metal affinity chromatography resin (Phos-Select, Sigma) was washed and equilibrated with 50% ACN and 0.1% TFA using Mobicol spin columns (MoBiTec, Göttingen, Germany) with 10-μm plugs. Peptide samples were added to the immobilized metal affinity chromatography suspension and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The flow-through was collected, and the immobilized metal affinity chromatography resin was washed once with 50 μl 50% ACN and 0.1% TFA. The wash fraction was pooled with the flow-through. Acid elution was then carried out by adding 50 μl 30% ACN and 1% TFA and incubating for 5 min at room temperature. After this step, alkaline elution was done with 50 μl 0.5% NH4OH pH 10.5, followed by 30 min incubation at room temperature. For further enrichment of phosphopeptides, the flow-through fraction and the acid eluate were incubated with TiO2 beads as in the procedure described above for in-gel digestion.

LC-MS/MS

Peptides were analyzed using nano-LC-MS/MS on an LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Peptides were separated on a BioBasic C-18 PicoFrit column (75 μm internal diameter × 10 cm; New Objective, Woburn, MA) at a flow rate of 200 nl/min. Water and ACN, both containing 0.1% formic acid, were used as solvents A and B, respectively. Peptides were trapped and desalted in the trap column for 5 min. The gradient was started and kept at 10% B for 5 min, ramped to 60% B over 60 min or 120 min, depending on the sample complexity, and kept at 90% B for another 5 min. The mass analyzer was an LTQ linear ion trap (Thermo Scientific) operating in the data-dependent mode to switch from full MS scan (mass width 400–1800 m/z), plus a top seven peaks zoom MS scan (mass width 10 Da), and MS2 scan (isolation width 2 m/z) with a normalized collision energy of 35% and MS3 neutral loss scans of 98, 49, and 32.6. The scanning was performed using a dynamic exclusion list (35 s exclusion list size of 500 and exclusion width of 2 m/z).

Database Searches for Peptide Identification

Peak lists from all MS/MS spectra were extracted from the Xcalibur RAW files using the freely available program DTAsupercharge v.1.19. The peptide search was performed with licensed version 2.1 of MASCOT using a local yeast database obtained from the Saccharomyces Genome Database (Stanford University), containing 6717 sequences. Search parameters were as follows: cysteine carbamidomethylation as a fixed modification; methionine oxidation and phosphorylation of serine, threonine, and tyrosine, label 13C6-lysine and label 13C6-arginine as variable modifications; trypsin as enzyme, two missed cleavage sites, 300 ppm as precursor ion mass tolerance and 0.8 Da as fragment ion mass tolerance. The spectra and data from the LC-MS/MS analysis are available at the PRIDE repository of the European Bioinformatics Institute (www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/) (40), accession numbers 21565–21568.

SILAC Quantification

MASCOT search results and spectra raw data were imported into QuiXoT v1.3.26. QuiXoT was developed and adapted for SILAC isotope pair quantification by the J. Vázquez Lab at Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares, Madrid, Spain. Experiments were performed at the Proteomics Unit of Universidad Complutense de Madrid–Parque Cientifico de Madrid, which is a beta-tester of the QuiXoT software. Peptide quantification from ZoomScan spectra was performed as described elsewhere (41, 42). The relative ratio of SILAC ion pairs was calculated from Zoom MS scans corresponding to peptides with a false discovery rate < 1% in MASCOT 2.2 search results (MOWSE score > 20). The SILAC ratio for each unique peptide observation was averaged out of the scans used to quantify the peptides. The ratios for phosphopeptides were averages of technical and biological replicates. All ratios were normalized with respect to the grand mean for each biological replicate. The grand mean was estimated as a weighted average of the protein values.

Phosphosite Location

The location of the phosphorylated residues was automatically assigned by MASCOT (score > 20). Additionally, some phosphopeptides were evaluated with a Proteome Discoverer v1.3 analysis (pRS site probabilities > 75%) and further validated through manual interpretation of MS2 and MS3 spectra.

Consensus Motif Analyses

Consensus motifs were determined using the Motif-X program (80). Sequences were centered on each phosphorylation site and extended to 13 amino acids (six residues on each side). The significance threshold was set at p < 10−6.

Functional Classification

Functional categories for S. cerevisiae proteins were assigned using the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD; Stanford, CA). The FunSpec web-based tool was used for statistical evaluation of groups of proteins with respect to existing annotations, including gene ontology terms or parents of gene ontology terms. Statistical testing for enrichment of functional categories among the set of identified proteins was based on a hypergeometric distribution model using the method of Hughes and co-workers (43). This method gives the probability (p value) that the intersection of a given list with any given functional category will occur by chance. The GeneMania web tool was consulted to check for recorded interactions among protein hits.

RESULTS

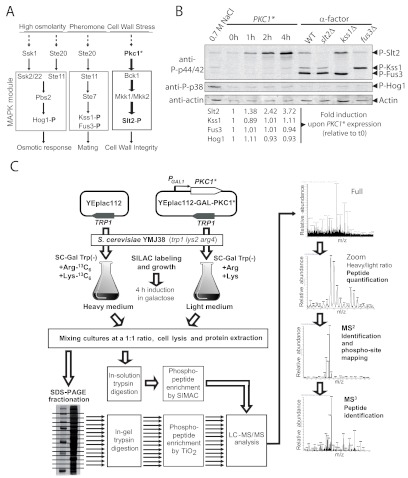

SILAC Labeling of a Yeast Strain Overproducing Hyperactive Pkc1

A plethora of stimuli are known to cause activation of the Pkc1-mediated CWI signaling pathway, including enzymatic or chemical aggression to the cell wall, hypo-osmotic shock, temperature shifts, drugs such as caffeine, and treatment with mating pheromones (14, 16, 44). However, most of these stimuli might not elicit a response specific for the CWI signaling pathway, likely leading to alternative stress responses and multiple phosphorylation/dephosphorylation events in the cell other than those attributable to Pkc1-CWI activation. Thus, for a global study of the Pkc1-dependent phosphoproteome, we chose to endogenously hyperactivate Pkc1 in the absence of any external stimulus. The overexpression from the GAL1 promoter of a hyperactive allele of PKC1 (PKC1R398A,R405A,K406A) causes strong activation of the downstream Slt2 kinase, which can be monitored with anti-phosphoMAPK-specific antibodies (Fig. 1A) (15). We constructed an S. cerevisiae strain suitable for transformation with the TRP1-based YEplac112-GAL-PKC1 plasmid, as well as for SILAC labeling with 13C6-lysine and 13C6-arginine, by crossing the appropriated strains and selecting an Arg− Lys− and Trp− segregant. The resulting strain was transformed with the galactose-inducible plasmid that leads to overexpression of Pkc1R398A,R405A,K406A. Hyperactive Pkc1-dependent activation of the Slt2 MAPK was verified via Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 1B, GAL1-driven expression of hyperactive Pkc1 led to a gradual increase in the phosphorylation of Slt2 over time, without significant phosphorylation of the other yeast MAPK modules, namely, those involving Kss1, Fus3, and Hog1 (Figs. 1A, 1B). Therefore, such an experimental design should allow specific quantitative phosphoproteomic analyses of Pkc1-CWI signaling, avoiding any background noise due to the activation of multiple MAPK pathways.

Fig. 1.

Rationale and workflow for a differential quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of yeast Pkc1-CWI MAPK signaling. A, scheme of the main MAPK pathways operating in yeast. The MAPK module composed of the MAPKKK, MAPKK, and MAPK for each pathway is squared, and the activating protein kinases upstream of each module are shown. B, expression of hyperactive Pkc1 causes specific activation of the Slt2 MAPK. Lysates from BY4741 yeast cells at time points (0–4 h) after the addition of galactose for the induction of the hyperactive PKC1R398A,R405A,K406A allele (PKC1*) were monitored via Western blotting with anti-P-p44/42 antibodies for phospho-Slt2, -Kss1, and -Fus3 and anti-P-p38 antibodies for phospho-Hog1. Actin was also immunodetected as a general loading control. Control lanes were included for the visualization of activated Hog1 (cells treated with 0.7 m NaCl for 5 min to induce osmotic stress) or Kss1 and Fus3 (cells treated with 3 μm α-factor for 30 min to induce the mating response). To identify the bands corresponding to Slt2, Kss1, and Fus3, isogenic strains deleted for the genes encoding these MAPKs were used and exposed to α-factor. The quantification of phosphorylation in cells expressing PKC1* was determined by means of densitometry and normalized to the signal at t = 0 h. C, workflow of the quantitative phosphoproteomic approach followed. Briefly, parallel cultures of the MJY38 strain transformed with either the empty vector YEplac112 or YEplac112-GAL-PKC1* were labeled, respectively, with heavy and light isotopes of Arg and Lys. Cultures were incubated for 4 h in galactose at 30 °C to induce the overexpression of hyperactive Pkc1 in the latter culture and then mixed. Three biological replicates were analyzed. Protein extracts were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels, and 12 fractions of each gel were digested with trypsin and subjected to phosphopeptide enrichment by either TiO2 or SIMAC affinity purification. Also, a fraction of each sample was directly digested and subjected to SIMAC. LC-MS/MS analysis of the eluted fractions was performed, the light/heavy ratio was calculated for quantification, and further MS2 and MS3 analyses of peptides were carried out for identification and sequencing.

We grew transformants bearing either the PKC1R398A,R405A,K406A-expression plasmid or the empty vector on raffinose-based selective media containing, respectively, either unmodified arginine and lysine (light) or 13C6-lysine and -arginine (heavy) for 16 h, according to the experimental workflow in Fig. 1C. Inocula were adjusted so that cells would grow for 8 to 10 generations and keep log-phase after such an incubation time. Galactose was added to the media and cultures were further incubated for 4 h to achieve PKC1R398A,R405A,K406A overexpression. The incorporation of heavy/light-isotope-marked lysine and arginine was tested through LC-MS/MS analysis after SDS-PAGE separation and trypsin digestion of samples of cell extracts from each culture. The absence of light isotope in the heavy-labeled sample revealed that incorporation was achieved. Then, equal amounts of cells from both cultures were mixed, and cell extracts were obtained. Three biological replicates of the experiment were generated for further analysis.

Phosphopeptide Enrichment and MS Analyses

As shown in Fig. 1C, two strategies were followed in parallel for phosphopeptide analysis of the heavy/light-labeled protein extracts prior to LC-MS/MS: (i) in-solution digestion and SIMAC-based enrichment of phosphopeptides, and (ii) SDS-PAGE fractionation, in-gel digestion, and TiO2 chromatography-based phosphopeptide enrichment. The first approach led to samples of greater complexity but allowed a more ready analysis than time-consuming gel fractionation, and it was adopted to analyze two of the three biological replicates in the experiment. In the second strategy, fractionation in gel decreases the complexity of the sample and increases the number of phosphorylation site identifications (11). This approach was followed to analyze all three biological replicates. In all cases, two technical replicates were performed in parallel for each biological replicate. Fractions obtained via both approaches were significantly enriched in phosphopeptides relative to raw cell extracts processed in parallel as a control (data not shown). Analysis of the data in the MASCOT search engine led to the identification of 3321 unique peptides corresponding to 703 proteins, including 707 unique phosphopeptides representative of 379 phosphoproteins.

Quantitative Phosphoproteomics of Yeast Cells upon Pkc1 Hyperactivation

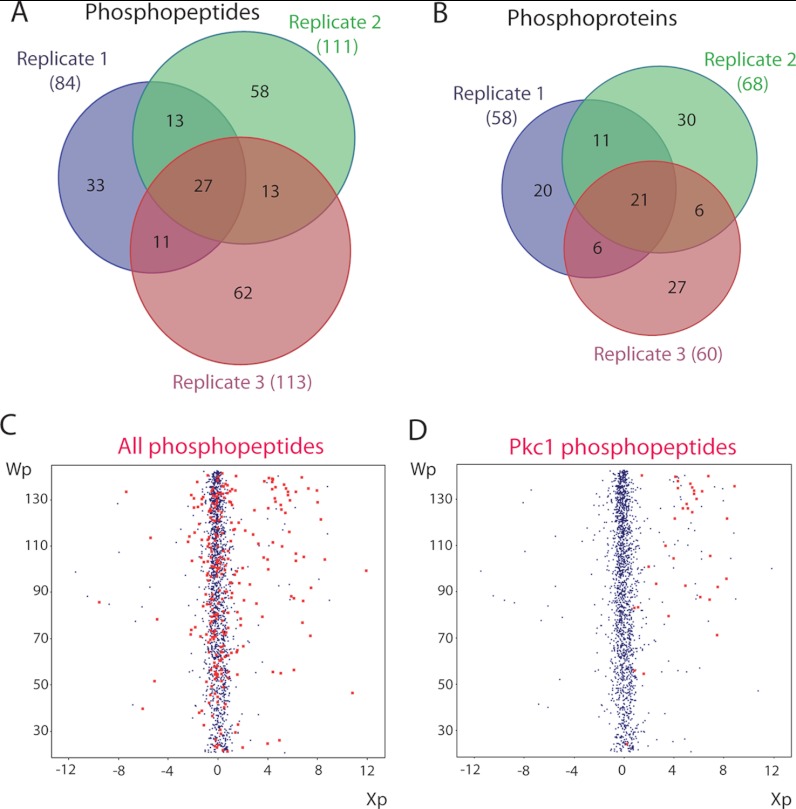

Quantification of heavy/light ratios was performed using QuiXoT. The log2-ratio value associated with each peptide was calculated as a weighted average of the scans used to quantify the peptide (Xp), as described elsewhere (41, 42). Only quantified peptides detected as statistically significant were selected. Analysis of the data led to the quantification of 456 unique proteins and 121 phosphoproteins, represented by 2124 quantified peptides and 217 quantified phosphopeptides, respectively. The quantified phosphopeptides and statistical parameters used are shown in supplemental Tables S1 and S2. In these phosphopeptides, 308 phosphosites were identified, with 193 corresponding to phosphoserine, 57 to phosphothreonine, and only 1 to phosphotyrosine. This is consistent with the absence of specific tyrosine kinases in yeast (45), in which phosphorylation on tyrosine is a rare modification performed by dual-specificity kinases, such as MAPKKs. Among the quantified phosphopeptides, 27 were bi-phosphorylated, and 3 tri-phosphorylated. Overlapping hits in the three biological replicates are shown by Venn diagrams for quantified phosphopeptides (Fig. 2A) and phosphoproteins (Fig. 2B). It can be concluded that although our experiment is not saturated, the triple replicate greatly increases the likeliness of finding underrepresented hits.

Fig. 2.

Phosphoproteome changes in conditions of hyperactive Pkc1 overproduction. A, Venn diagram representing overlapping of phosphopeptides with enhanced phosphorylation in hyperactive Pkc1-overexpression conditions from the three biological replicates. 26.3% of the quantified phosphopeptides were detected in the three replicates, whereas 50.2% were common for at least two replicates, and 49.8% were detected only in a particular replicate. B, Venn diagram representing overlapping of proteins corresponding to the phosphopeptide dataset in A. 33.4% of the proteins were found to be up-regulated in the three replicates, whereas 57.8% were found in at least two and 42.2% were detected only in one. C, the statistical weight associated with each quantification at the scan level for each peptide (Wp) was plotted against the corresponding averaged log2 light/heavy ratio of the peptide ratio (Xp). Phosphopeptides are represented by red dots. D, representation of SILAC pair ratios as in C, but with only phosphopeptides identified as Pkc1 marked in red.

Our goal in following this quantitative phosphoproteomic approach was to unveil novel targets of Pkc1 or the kinases downstream in the CWI pathway. As shown in Fig. 2C, outlier peptides showing enhanced phosphorylation under Pkc1 hyperactivation conditions were more abundant than those displaying decreased phosphorylation. Eighty-two phosphopeptides originating from 43 proteins were finally validated to display a higher degree of phosphorylation under Pkc1 hyperactivation conditions (>1.5-fold; 66 of them over 2-fold; Table II). In addition, 44 phosphopeptides from 26 phosphoproteins were considered as displaying decreased phosphorylation in our dataset (<0.75-fold; 18 of them below 0.5-fold; Table III). Many of the up-regulated phosphopeptides belonged to overproduced Pkc1 (Fig. 2D; see also Fig. 3C). Also, up-regulated phosphopeptides were identified for the Slt2 MAPK, demonstrating the value of our proteomic approach for detecting phosphorylation events derived from activation of the CWI pathway. Indeed, two hits of the GYSENPVENSQFLTEYVATR phosphopeptide were identified, corresponding to both single phosphorylation in Thr190 and double phosphorylation in Thr190 and Tyr192 at the activation loop of Slt2 (Fig. 3A). The dually phosphorylated form was strongly up-regulated relative to the control under hyperactive PKC1-overexpression conditions (Table II).

Table II. List of identified differentially up-regulated phosphopeptides; Pkc1 phosphopeptides are shown in Fig. 3B.

| Protein | Phosphopeptide sequence | Phosphorylation site | Fold changea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ape2 | R.VVDLLLDKDNS(ph)T(ph)LDR.I | Ser382//Thr383 | ≥4.00 |

| Bbc1 | K.SFVAVQGSEVGKEAESS(ph)PNTGSTEQR.T | Ser78 | ≥4.00 |

| Caf20 | K.KKGS(ph)GEDDEEET(ph)ETTPTSTVPVATIAQETLK.V | Ser91//Thr99 | ≥4.00 |

| Caf20 | K.KKGSGEDDEEET(ph)ETTPTSTVPVATIAQETLK.V | Thr99 | ≥4.00 |

| Dcp2 | K.RNS(ph)VSKPQNSEENASTSSINDANASELLGMLK.Q | Ser771 | ≥4.00 |

| Dcp2 | K.RNSVS(ph)KPQNSEENASTSSINDANASELLGMLK.Q | Ser773 | ≥4.00 |

| Def1 | K.KTES(ph)PLENVAELKK.E | Ser260 | ≥4.00b |

| Fba1 | K.DYIMS(ph)PVGNPEGPEKPNKK.F | Ser313 | ≥4.00b |

| Ipp1 | K.AASDAIPPAS(ph)PKADAPIDK.S | Ser266 | ≥4.00b |

| Krs1 | K.KKT(ph)DLFADLDPSQYFETR.S | Thr62 | ≥4.00 |

| Lsp1 | K.ALLELLDDSPVT(ph)PGEARPAYDGYEASR.Q | Thr233 | ≥4.00b |

| Nup159 | K.SLS(ph)PTSEKIPIAGQEQEEK.K | Ser404 | ≥4.00 |

| Pfk2 | K.FLSLENRS(ph)SPDENSTLLSNDSISLK.I | Ser41 | ≥4.00 |

| Pil1 | K.ALLELLDDSPVT(ph)PGETRPAYDGYEASK.Q | Thr233 | ≥4.00b |

| Rcn2 | R.NKPLLSINT(ph)DPGVTGVDSSSLNK.G | Thr132 | ≥4.00b |

| Rcn2 | R.SNAASCTENDVNATASNPPKS(ph)PSITVNEFFH.- | Ser255 | ≥4.00b |

| Rgt1 | K.FFDNIVGVALS(ph)PSNDNNK.A | Ser599 | ≥4.00b |

| Rnr2 | K.AAADALS(ph)DLEIKDSK.S | Ser15 | ≥4.00b |

| Sec31 | R.VAT(ph)PLS(ph)GGVPPAPLPK.A | Thr1050//Ser1053 | ≥4.00b |

| Slt2 | R.GYSENPVENSQFLT(ph)EY(ph)VATR.W | Thr190//Tyr192 | ≥4.00b |

| Ssb1 | K.S(ph)KIEAALSDALAALQIEDPSADELR.K | Ser572 | ≥4.00 |

| Ssb1 | K.S(ph)KIEAALSDALAALQIEDPSADELRK.A | Ser572 | ≥4.00 |

| Ssb1 | R.GSKS(ph)KIEAALSDALAALQIEDPSADELR.K | Ser572 | ≥4.00 |

| Taf12 | R.KIS(ph)SSNSTEIPSVTGPDALK.S | Ser286 | ≥4.00 |

| Tdh3 | K.VINDAFGIEEGLMTTVHSLT(ph)ATQK.T | Thr180 | ≥4.00 |

| Tdh3 | K.VINDAFGIEEGLMTTVHSLTAT(ph)QK.T | Thr182 | ≥4.00b |

| Tof2 | R.VSTPLMNEILPLAS(ph)K.Y | Ser236 | ≥4.00 |

| Tom70 | K.FGDIDTATATPT(ph)ELSTQPAK.E | Thr234 | ≥4.00 |

| Tup1 | K.DVENLNTSSS(ph)PSSDLYIR.S | Ser439 | ≥4.00b |

| Zeo1 | K.EQAEASIDNLKNEAT(ph)PEAEQVKK.E | Thr49 | ≥4.00 |

| Pst2 | R.SPS(ph)ALELQVHEIQGK.T | Ser177 | 3.56 |

| Caf20 | K.KKGSGEDDEEETET(ph)TPTSTVPVATIAQETLK.V | Thr101 | 3.39 |

| Caf20 | K.KKGSGEDDEEETETT(ph)PTSTVPVATIAQETLK.V | Thr102 | 3.28 |

| Eis1 | K.IASGLIS(ph)PVLGEVSER.A | Ser401 | 3.10 |

| Ssa1 | R.GVPQIEVTFDVDSNGILNVS(ph)AVEKGTGK.S | Ser486 | 3.08 |

| Pst2 | R.S(ph)PSALELQVHEIQGK.T | Ser175 | 2.93 |

| Seg1 | K.NLENDTTSS(ph)PTQDLDEK.S | Ser450 | 2.70 |

| Hxk2 | R.KGS(ph)MADVPK.E | Ser15 | 2.67 |

| Caf20 | K.GSGEDDEEETETT(ph)PTSTVPVATIAQETLK.V | Thr102 | 2.49 |

| Caf20 | K.GS(ph)GEDDEEETETTPTSTVPVATIAQETLK.V | Ser91 | 2.44 |

| Ssa1 | R.GVPQIEVTFDVDSNGILNVSAVEKGT(ph)GK.S | Thr492 | 2.37 |

| Seg1 | K.NLENDTTSSPT(ph)QDLDEK.S | Thr452 | 2.36 |

| Egd1 | K.KDEAIPELVEGQT(ph)FDADVE.- | Thr151 | 2.23 |

| Caf20 | K.GSGEDDEEETETTPT(ph)STVPVATIAQETLK.V | Thr104 | 2.21 |

| Caf20 | K.GSGEDDEEETETTPTS(ph)TVPVATIAQETLK.V | Ser105 | 2.20 |

| Num1 | R.VELQNNEDYTDIIS(ph)K.S | Ser2162 | 2.19 |

| Pil1 | R.APT(ph)ASQLQNPPPPPSTTK.G | Thr14 | 2.17 |

| Fas2 | R.VVEIGPS(ph)PTLAGMAQR.T | Ser50 | 2.02 |

| Rnr4 | K.S(ph)ATPSKEINFDDDF.- | Ser332 | 1.97 |

| Rnr4 | K.SATPS(ph)KEINFDDDF.- | Ser336 | 1.97 |

| Rnr4 | K.SAT(ph)PSKEINFDDDF.- | Thr334 | 1.92 |

| Cdc33 | K.KFEENVSVDDTTAT(ph)PK.T | Thr22 | 1.88 |

| Pfk1 | K.DAFLEATSEDEIIS(ph)R.A | Ser185 | 1.87 |

| Bbc1 | K.DLPEPISPET(ph)KK.E | Thr106 | 1.86 |

| Tma17 | K.LEGADDRLEADDS(ph)DDLENIDSGDLALYK.D | Ser68 | 1.83 |

| Pfk2 | R.SS(ph)PDENSTLLSNDSISLK.I | Ser42 | 1.78 |

| Ugp1 | K.THS(ph)TYAFESNTNSVAASQMR.N | Ser11 | 1.73 |

| Dcp2 | R.DSGYS(ph)SSSPGQLLDILNSK.K | Ser436 | 1.70 |

| Gga1 | K.VSLSS(ph)PKS(ph)PQENDTVVDILGDAHSK.S | Ser375//Ser378 | 1.62 |

| Pup2 | K.EKEAAES(ph)PEEADVEMS.- | Ser251 | 1.61 |

| Sod1 | K.FEQASESEPTTVSYEIAGNS(ph)PNAER.G | Ser39 | 1.60 |

| Ycf1 | R.ESS(ph)IPVEGELEQLQK.L | Ser878 | 1.59 |

| Mds3 | K.IS(ph)ASSLPIPIENFAK.H | Ser472 | 1.57 |

| Pil1 | R.APTAS(ph)QLQNPPPPPSTTK.G | Ser16 | 1.57 |

a Values over 4-fold are not linear in QuiXot quantification analyses.

b Phosphopeptides identified at least in two biological replicates.

Table III. List of identified differentially down-regulated phosphopeptides.

| Protein | Phosphopeptide sequence | Phosphorylation site | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nup145 | K.AYEPDLS(ph)DADFEGIEASPK.L | Ser679 | 0.750 |

| Snf1 | K.SVSDELDTFLSQS(ph)PPTFQQQSK.S | Ser413 | 0.750a |

| Fpk1 | R.TNS(ph)FVGTEEYIAPEVIR.G | Ser676 | 0.730 |

| Ybr085c-a | K.QSTNFTHST(ph)GS(ph)FLQS(ph)APVELTTVSGYQEFLK.K | Thr16//Ser18//Ser22 | 0.730 |

| Ybr085c-a | K.QSTNFTHSTGS(ph)FLQSAPVELTTVSGYQEFLK.K | Ser18 | 0.730 |

| Pfk2 | K.NAVSTKPTPPPAPEASAES(ph)GLSSK.V | Ser163 | 0.700a |

| Rpg1 | R.TAGGSS(ph)PATPATPATPATPTPSSGPK.K | Ser926 | 0.690 |

| Rps3 | K.EEEPILAPS(ph)VK.D | Ser221 | 0.690 |

| Ura2 | K.RRFS(ph)ITEEAIADNLDAAEDAIPEQPLEQK.L | Ser1857 | 0.690 |

| Ura2 | K.RRFSIT(ph)EEAIADNLDAAEDAIPEQPLEQK.L | Thr1859 | 0.690 |

| Abp1 | K.SFT(ph)PSKSPAPVSK.K | Thr165 | 0.680 |

| Rpg1 | R.TAGGSSPAT(ph)PATPATPATPTPSSGPK.K | Thr929 | 0.680 |

| Mlf3 | K.SNSNNS(ph)NPSFIFER.T | Ser11 | 0.670 |

| Scp160 | R.LTYEPIDLSSILS(ph)DGEEK.E | Ser1112 | 0.660 |

| Lsb3 | R.LAPTNSGGS(ph)GGKLDDPSGASSYYASHR.R | Ser303 | 0.620 |

| Meh1 | R.TNTFTLLTS(ph)PDSAK.I | Ser146 | 0.610 |

| Mlf3 | K.SNS(ph)NNSNPSFIFER.T | Ser8 | 0.610 |

| Gal2 | K.AGESGS(ph)EGSQSVPIEIPK.K | Ser50 | 0.600 |

| Pin4 | R.NSQISPPNS(ph)QIPINSQTLSQAQPPAQSQTQQR.V | Ser545 | 0.600 |

| Rpp2b | K.FATVPTGGASSAAAGAAGAAAGGDAAEEEKEEEAKEES(ph)DDDMGFGLFD.- | Ser100 | 0.600 |

| Gly1 | R.SES(ph)TEVDVDGNAIR.E | Ser369 | 0.590a |

| Prp43 | R.RFS(ph)SEHPDPVETSIPEQAAEIAEELSK.Q | Ser8 | 0.580 |

| Cof1 | R.S(ph)GVAVADESLTAFNDLK.L | Ser4 | 0.560 |

| Sec31 | R.VPS(ph)LVATSESPR.A | Ser992 | 0.550a |

| Pin4 | R.NS(ph)QISPPNSQIPINSQTLSQAQPPAQSQTQQR.V | Ser538 | 0.530 |

| Shp1 | R.LGS(ph)PIPGESSPAEVPK.N | Ser315 | 0.500 |

| Sec31 | R.VPSLVATSES(ph)PR.A | Ser999 | 0.490a |

| Nup159 | R.LPETPS(ph)DEDGEVVEEEAQK.S | Ser805 | 0.470 |

| Sec31 | R.VPSLVAT(ph)SESPR.A | Thr996 | 0.440a |

| Ede1 | R.TTPLS(ph)ANS(ph)TGVSSLTR.H | Ser241//Ser244 | 0.370 |

| Gal2 | K.AGES(ph)GSEGSQSVPIEIPK.K | Ser48 | 0.370a |

| Gal2 | K.AGES(ph)GSEGS(ph)QSVPIEIPK.K | Ser48//Ser53 | 0.370a |

| Gal2 | K.AGESGS(ph)EGS(ph)QSVPIEIPK.K | Ser50//Ser53 | 0.370a |

| Ura2 | R.RFSIT(ph)EEAIADNLDAAEDAIPEQPLEQK.L | Thr1859 | 0.360 |

| Meh1 | R.SAGDDNLS(ph)GHS(ph)VPSSGSAQATTHQTAPR.T | Ser117//Ser120 | 0.340 |

| Sec31 | R.APS(ph)SVSMVSPPPLHK.N | Ser974 | 0.320 |

| Gal2 | K.AGES(ph)GS(ph)EGS(ph)QSVPIEIPK.K | Ser48//Ser50//Ser53 | 0.300 |

| Ydr098c-b | R.HSDSYS(ph)ENETNHTNVPISSTGGTNNK.T | Ser1055 | 0.280 |

| Ydr098c-b | R.SPS(ph)IDASPPENNSSHNIVPIK.T | Ser1095 | 0.280a |

| Ydr098c-b | R.S(ph)PSIDASPPENNSSHNIVPIK.T | Ser1093 | 0.240a |

| Meh1 | R.S(ph)AGDDNLS(ph)GHSVPSSGSAQATTHQTAPR.T | Ser110//Ser117 | 0.270 |

| Ydr098c-b | R.SPSIDAS(ph)PPENNSSHNIVPIK.T | Ser1099 | 0.250 |

| Tgl5 | R.KmDMLSPSPSPS(ph)T(ph)SPQR.S | Ser624//Thr625 | 0.020 |

| Gph1 | R.RLT(ph)GFLPQEIK.S | Thr31 | 0.005a |

a Phosphopeptides identified at least in two biological replicates.

Fig. 3.

MAPK phosphorylation site motifs and Pkc1 peptides are overrepresented in the dataset. A, MS2 spectrum of peptide GYSENPVENSQFLpTEpYVATR, which includes the dually phosphorylated Thr and Tyr residues in the activation loop of Slt2. Peptide sequence and assigned fragment ions y (in blue) and b (in yellow) are indicated (pRS site probabilities = 100% as determined by Proteome Discoverer Software v1.3). B, Motif-X analysis of phosphorylation site motifs revealed that the S/T-P MAPK target site was found in 35% of the up-regulated phosphopeptides (score 11.00). In the logoplot, the height of each amino acid represents its frequency at the position indicated with respect to the position of phospho-Ser/Thr. C, up-regulated phosphopeptides detected for Pkc1. Different domains along Pkc1 are shown, with arrowheads pointing to the position of the phosphorylated residues. Green arrowheads indicate that the predicted phosphosites match the (R/K-X-X-S/T) AGC kinase target motif. Red arrowheads indicate putative (S/T-P) MAPK target sites. The asterisk (*) marks the phosphosite (Thr983) corresponding to the activation loop of AGC kinases.

In order to identify consensus phosphorylation sites of known protein kinases, enriched sequence motifs surrounding the phosphosites in our dataset were analyzed via Motif-X (80). The most representative phosphorylation sequence for the up-regulated phosphopeptides was S/T-P, the preferred site of Pro-directed kinases, such as MAPKs and cyclin-dependent kinases (46). This motif was present in 35% of the up-regulated phosphosites (Fig. 3B). The lack of enrichment for a basic (K/R) residue at the P-site+3 position, which is a feature of the cyclin-dependent kinase phosphorylation signature (47), suggested an overrepresentation of MAPK target sites for the up-regulated phosphoproteins. Representation of the S/T-P motif in non-changing or down-regulated phosphosites was significantly lower (26% and 20%, respectively), underscoring the notion that an important proportion of phosphoproteome changes induced by Pkc1 hyperactivity may be sustained by the downstream MAPK Slt2.

Because Pkc1 was overproduced in our experiment, several phosphopeptides covering this protein were detected as up-regulated. In fact, up to 18 different Pkc1 phosphopeptides were recorded (Fig. 3C), suggesting that this protein is susceptible to heavy phosphorylation. Most of the Pkc1 phosphosites were mapped in a region between the cysteine-rich C1 (involved in Rho1 interaction) and the kinase domains (17). Such an interdomain region has low similarity to C2 domains and bears nuclear localization sequences (48). Many of the detected phosphosites (Ser623, Ser656, Ser657, Ser670, Thr674, Thr683, Ser686, and Ser820) have not been previously reported. One of them (Ser820) matched the phosphorylation consensus sequence (R-x-x-S/T) of AGC kinases (49), which includes the PKC family, suggesting either autophosphorylation or phosphorylation by other yeast AGC kinases, such as PKA, Sch9, Ypk1, or Ypk2. Another phosphosite (Thr983) corresponding to the conserved residue at the PDK1 target motif in the activation loop of AGC kinases is likely targeted by Pkc1 activating kinases Pkh1 and Pkh2. These yeast PDK1 homologs have been described as phosphorylating Thr983 in Pkc1 both in vivo and in vitro (19). Interestingly, S/T-P MAPK target motifs, namely, Ser226, Ser577, and Ser657, were also found to be phosphorylated in Pkc1, suggestive of putative regulatory feedback loops in the pathway. Phosphorylation at residues 226 and 657 has not been reported in previous phosphoproteomic analyses in search of targets of cyclin-dependent kinase, DNA damage checkpoint kinases, or other yeast MAPKs (10, 13, 50), indicating that they are good candidates for specific phosphorylation by the CWI MAPK Slt2.

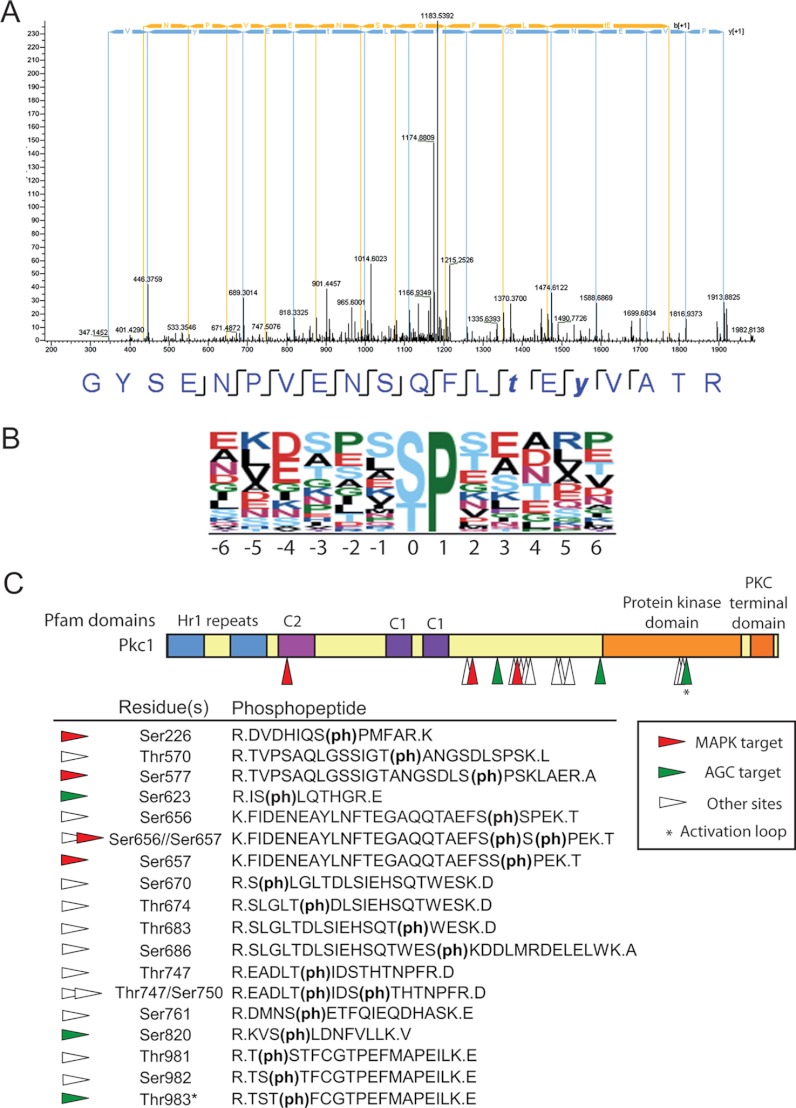

Functional clustering of proteins that displayed enhanced phosphorylation in our dataset is presented in Fig. 4, in which those proteins containing either PKC or MAPK consensus phosphosites are highlighted. Hyperactivation of Pkc1 led to increased phosphorylation of proteins involved in diverse functions. Among them, we found enzymes related to carbohydrate metabolism and protein synthesis, some of which are highly abundant proteins. Also, several proteins related to transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, protein folding, cytoskeletal regulation, signaling, and detoxification were found to be up-regulated. Our data revealed that some proteins seem to be subjected to complex layers of regulation. For instance, Nup159 and Sec31 were found to be hypophosphorylated in some residues and hyperphosphorylated in others. Gene ontology enrichment analysis using the FunSpec tool revealed that the plasma-membrane-enriched fraction category, which includes eisosome components, is highly overrepresented in the up-regulated dataset (p value < 10−8).

Fig. 4.

Clustering of proteins containing phosphopeptides that display enhanced phosphorylation upon Pkc1 hyperactivation according to their biological function. Data were manually curated from the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) and clustered according to Gene Ontology categories. Proteins within the same category are included in the enclosed colored areas. Proteins in green boxes displayed differentially phosphorylated residues that correspond to R/K-X-X-S/T motifs, which could be putative direct Pkc1 targets. Proteins framed in red displayed differentially phosphorylated S/T-P residues, constituting putative MAPK targets. Black lines connect proteins reported to physically interact or co-purify in complexes (according to GeneMANIA and the SGD) within each category. Bold red lines link proteins reported to complex with either Pkc1 or Slt2 in mass co-purification experiments.

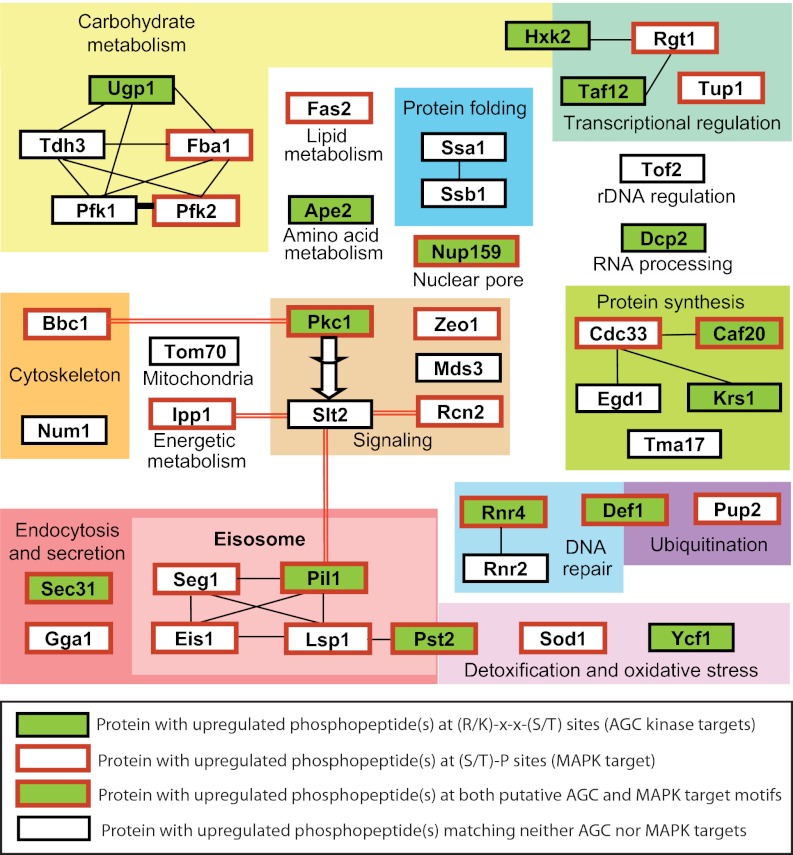

Eisosomes are large protein complexes with an elusive function that associate with plasma membrane furrow-like microdomains known as membrane compartment of Can1 domains (51–53). Eisosomes are primarily composed of two paralogous proteins, Pil1 and Lsp1 (54), but several other associated proteins have increasingly been identified in recent years via co-purification and co-localization experiments (55). In our quantitative proteomic analysis, we found increased phosphorylation of five eisosome components, namely, Pil1, Lsp1, Eis1, Seg1, and Pst2. The eisosome core components Pil1 and Lsp1 have been reported to be phosphoproteins, and several Pil1 phosphorylation sites have been determined via MS non-quantitative analyses (33, 56). We have identified three up-regulated phosphopeptides for Pil1 in which Thr14, Ser16, and Thr233 are the modified residues, respectively (Table II). Increased phosphorylation of the equivalent Thr233 residue in the sequence of Lsp1 was also detected. Two up-regulated phosphopeptides were found in Seg1 (Ser450 and Thr452) and Pst2 (Ser175 and Ser177), whereas only one was detected in Eis1 (Ser401).

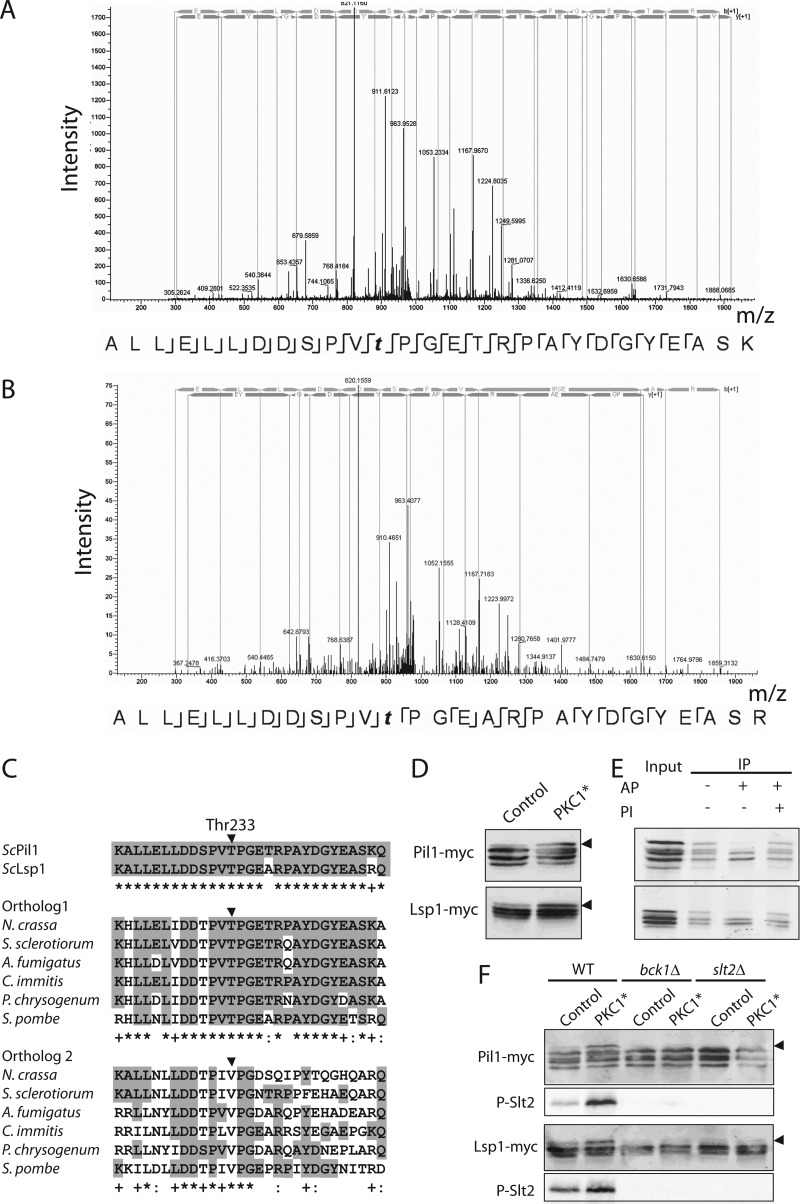

Pkc1-induced Phosphorylation of Eisosome Components Pil1 and Lsp1 Is Mediated by the Slt2 MAPK

We chose the eisosome core components Pil1 and Lsp1 to validate the results obtained via quantitative phosphoproteomics. Interestingly, the Thr233 residue, which was found to undergo phosphorylation upon Pkc1 hyperactivation in both Pil1 and Lsp1, suited a putative Pro-directed MAPK target site (Figs. 5A, 5B). We aligned the region covered by the corresponding phosphopeptides to the equivalent Lsp1/Pil1 orthologs in other fungi (Fig. 5C). In agreement with previous observations (33, 53), we found that this region was extraordinarily conserved through the phylum Ascomycota, including the Thr233 residue, even in species phylogenetically distant from S. cerevisiae such as filamentous fungi (Aspergillus, Penicillium) or fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces). These findings point toward a conserved role of eisosome components and their regulation in fungi. Peculiarly, most of these distant fungal species bore in their genomes two related orthologs, one of them very reminiscent of Pil1 and Lsp1 and a second one with a lower degree of similarity in which Thr233 is substituted for valine. Of interest, a neighboring Pro-directed Ser or Thr site at the 230 position is conserved in all orthologs (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Pkc1-triggered phosphorylation of eisosome core components Pil1 and Lsp1 is mediated by the CWI pathway. A, B, MS2 spectra of the up-regulated phosphopeptides for Pil1 (A) and Lsp1 (B) that include conserved Thr233. For interpretation of the spectra, see Fig. 3A. C, alignment of the sequence of S. cerevisiae (Sc) Pil1 and Lsp1 at the region surrounding the Thr233, which is marked with an arrowhead (upper panel). Two families of Pil1/Lsp1 orthologs from distant Ascomycota (Neurospora crassa; Sclerotinia sclerotiorum; Aspergillus fumigatus; Coccidioides immitis; Penicillium chrysogenum; Schizosaccharomyces pombe) are shown: one closely related to Pil1 and Lsp1 that displays conservation in the residue equivalent to Thr233 (middle panel), and a second, more divergent one in which the equivalent residue is substituted by Val (lower panel). Gray boxes highlight identity to the S. cerevisiae Pil1 sequence. An asterisk (*) denotes 100% conservation in that position for each subset of sequences; a colon (:) indicates conservation over 80% of the sequences; a cross (+) expresses interspecies substitutions with amino acids of similar properties. D, enhanced phosphorylation of Pil1 and Lsp1 upon hyperactive Pkc1 overexpression as detected by gel mobility shift. BY4741 cells expressing myc-tagged versions of either Pil1 or Lsp1 transformed with either the pEG(KG) vector alone (Control) or pEG(KG)-PKC1R398A,R405A,K406A (PKC1*) were grown in galactose-based media for 4 h at 24 °C and 1 extra hour at 39 °C. Cell extracts were analyzed via Western blotting with anti-myc antibodies. Arrowheads indicate the band of slowest mobility. E, mobility shift of Pil1 and Lsp1 in the presence of hyperactive Pkc1 is due to phosphorylation. Pil1-myc and Lsp1-myc were immunoprecipitated (IP) from yeast lysates of cells expressing Pkc1R398A,R405A,K406A as above and treated with alkaline phosphatase (AP) in the presence or absence of 10 mm sodium orthovanadate as a phosphatase inhibitor (PI). Samples were analyzed as in D. F, deletion of BCK1 or SLT2 abrogates Pkc1-dependent phosphorylation of both Pil1 and Lsp1. Lysates of bck1 and slt2 deleted strains in the BY4741 background with integrated myc-tagged PIL1 or LSP1, as indicated, were obtained and analyzed as in D. Anti-phospho-p44/42 antibodies were used to monitor activation of the Slt2 MAPK.

In order to detect Pil1 and Lsp1 proteins in yeast lysates via Western blotting, we integrated versions of the corresponding genes fused to six copies of the myc tag into the respective chromosomal loci. In agreement with previously reported results, both proteins were detected as multiple bands as a result of phosphorylation (33, 56). Remarkably, in conditions of hyperactive Pkc1 overexpression, a promotion to lower mobility states was observed for both Pil1 and Lsp1 (Fig. 5D). To confirm that this Pkc1-dependent mobility shift was due to an extra layer of phosphorylation of Pil1 and Lsp1, we immunoprecipitated both myc-tagged proteins and treated them with alkaline phosphatase in the absence or presence of orthovanadate as a phosphatase inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 5E, the bands of lowest mobility disappeared upon phosphatase treatment for both Pil1 and Lsp1, thus confirming their phosphorylation status. Still, phosphatase treatment did not collapse all Pil1 and Lsp1 forms into a single band, suggesting that these proteins might suffer other post-translational modifications. Actually, sumoylation has been reported recently as a modification of Pil1 and Lsp1 in Candida albicans (57).

According to our experimental conditions, either Pkc1 or kinases of the downstream CWI MAPK module could be responsible for the observed phosphorylation of eisosome components. To test whether Lsp1 and Pil1 phosphorylation depended on the Bck1 MAPKKK or the Slt2 MAPK, we expressed the Pil1-myc and Lsp1-myc constructs in both bck1Δ and slt2Δ mutants and checked their electrophoretic mobility in conditions of Pkc1 hyperactivation. As shown in Fig. 5F, Pkc1-induced phosphorylation of both Pil1 and Lsp1 was totally abrogated in the absence of either Bck1 or Slt2. These results strongly suggest that the Pkc1-activated CWI MAPK pathway is involved in eisosome phosphorylation.

Mutational Analysis of Ser230 and Thr233 Pro-directed Phosphorylation Sites

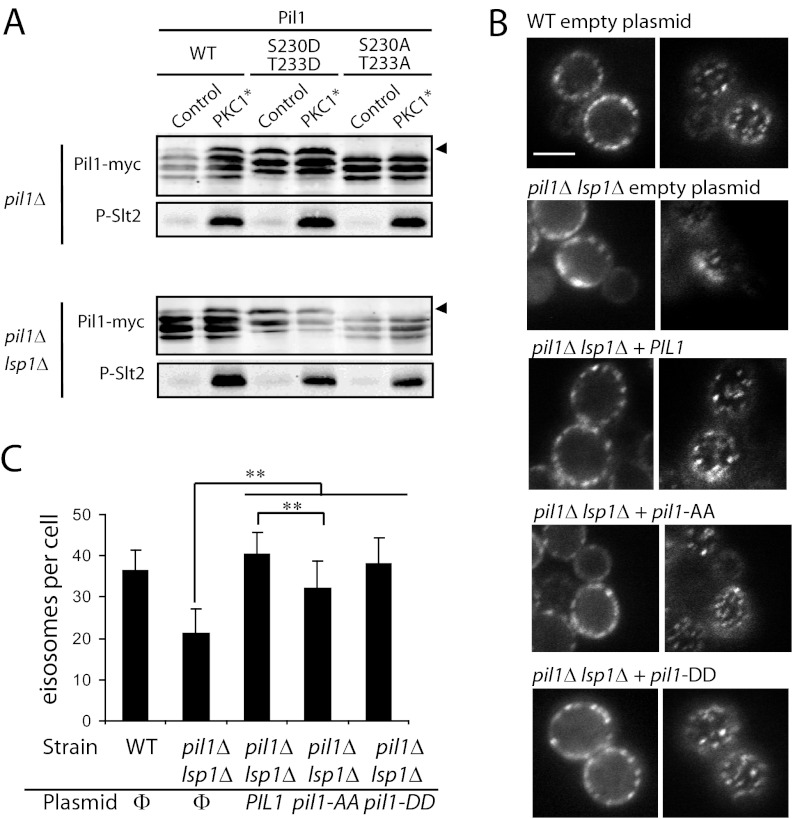

Phosphorylation of Pil1 and Lsp1 has been reported to be dependent on Pkh1 and Pkh2 kinases (33, 56). The functional implication of such phosphorylation remains controversial (reviewed in Refs. 52 and 53), likely because different laboratories have assayed the function of mutant proteins altered in different sets of phosphorylatable residues. Given that Pkh1/2 kinases are Pkc1 activators (19), our results suggest that at least part of this regulation might be exerted via the Pkc1-CWI MAPK pathway through the phosphorylation of Thr233 in Pil1 and Lsp1. To reinforce this hypothesis, we constructed mutant versions of Pil1 by changing Thr233 and neighboring Ser230 to either Ala or the phosphomimetic Asp residue. Although we had not detected phosphorylation at Ser230, we chose to mutate this additional residue because it is also a conserved Pro-directed site. First, we analyzed the mobility shift of these mutant proteins, expressed under the control of their own promoter, upon Pkc1 overexpression. As shown in Fig. 6A, the Pkc1/CWI-induced mobility shift was fully abrogated when Pil1S230A,T233A was expressed in both single pil1Δ and double pil1Δ lsp1Δ strains, confirming that the post-translational modification of Pil1 studied here maps in these residues. Moreover, the phosphomimetic Pil1S230D,T233D mutant protein had slower mobility, similar to that of the Pkc1-promoted band in wild-type (WT) Pil1.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of Pil1 mutants in putative MAPK target phosphosites Ser230 and Thr233. A, Western blotting of the electrophoretic mobility of Pil1S230D,T233D and Pil1S230A,T233A mutants upon Pkc1 hyperactivation. Y06988 (pil1Δ in the BY4741 background; upper panels) or VMY7 (pil1Δ lsp1Δ; lower panels) strains co-transformed with pRS315-based plasmids bearing the indicated versions of PIL1-myc under the control of its own promoter and either empty pEG(KG) (Control) or pEG(KG)-PKC1R398A,R405A,K406A (PKC1*) were processed as in Fig. 5D. Arrowheads indicate the band of slowest mobility. B, microscopic observation of Sur7-GFP at the plasma membrane. VMY8 (WT) or VMY9 (pil1Δ lsp1Δ) strains, both bearing a chromosomal integration of SUR7-GFP, were transformed with pRS315-based plasmids as in A expressing the Pil1 (WT), Pil1S230A,T233A (PIL1-AA), or Pil1S230D,T233D (PIL1-DD), respectively, grown to mid-log phase at 30 °C, and analyzed via fluorescence microscopy. Two focal planes of representative cells for each experiment are shown for each field (central focus, left panels; upper focus, right panels). All pictures are at the same scale. The bar represents 5 μm. C, graphic representation of the number of eisosomes per cell (n = 10) for the same cultures as in B. Empty vector is indicated by Φ. Only mother cells of average size, not buds, were counted. Asterisks (**) mark the statistical value of the data according to Student's t test (p < 0.05).

To investigate a putative function of this phosphorylation event in the organization of eisosomes, we integrated a SUR7-GFP construct in the WT, single pil1Δ, and double pil1Δ lsp1Δ strains. Sur7 is a plasma membrane integral protein that is enriched at membrane compartment of Can1 domains and eisosomes, so it is commonly used as a marker for these structures (34, 58). It has been reported that in pil1 mutants, Sur7-GFP changes its typical localization of evenly distributed homogenous patches to a few disorganized spots, known as eisosome remnants (56, 59). Although we still observed Sur7-GFP as organized membrane patches in the pil1Δ lsp1Δ mutant strain, they were less compact (Fig. 6B) and, especially, less numerous (Fig. 6C) than those in the WT. Whereas Pil1S230D,T233D was able to complement this defect as efficiently as the WT, Pil1S230A,T233A achieved only partial complementation (Figs. 6B, 6C). These conclusions were equivalent when the same experiment was performed in a single pil1Δ background (data not shown). These results hint that the phosphorylation of Pro-directed sites at the C-terminal extension of Pil1 might contribute positively to eisosome organization.

DISCUSSION

Phosphorylation is the predominant post-translational modification in cellular signaling. Therefore, large-scale analysis of differentially regulated protein phosphorylation is crucial for characterizing global cellular responses to environmental stimuli transduced by specific pathways (2). We report here, for the first time, a quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of Pkc1-CWI pathway signaling in S. cerevisiae. Similar approaches have been followed for other yeast MAPK pathways, such as that stimulated by mating pheromone in pioneer reports (10, 11) and, more recently, the high osmotic glycerol pathway (13). In our analysis, 43 proteins were found to display enhanced phosphorylation upon Pkc1 hyperactivation. The Pkc1-Slt2 pathway, unlike other MAPK cascades, has the peculiarity of lacking relevant desensitization or adaptation mechanisms, so its activation is gradual and persistent over several hours (see Ref. 16 for a review). We show here that the kinetics of Slt2 activation under Pkc1 overexpression are similar to those reported under diverse stimulating conditions (15, 60). Therefore, although one cannot dismiss the possibility that some of the phosphorylation events detected in our analysis might reflect indirect effects of Pkc1 overexpression, most of the hits should be representative of the cellular response mediated by this route. Among them, we have unveiled putative novel direct substrates for Pkc1, according to the presence of AGC consensus target sites in some of the up-regulated phosphopeptides. Despite the essential role of Pkc1 in the yeast cell and the numerous PKC targets described in mammalian systems, only the MAPKKK Bck1 (22), CTP synthetase (61), and the cell cycle transcriptional regulator Ndd1 (62) have been reported to date as bona fide substrates of this kinase.

The significant overrepresentation of S/T-P MAPK target sites in the up-regulated phosphoproteins suggested that, as expected, the Slt2 MAPK is a major actor downstream of Pkc1. Indeed, the only MAPK found in our analysis to be differentially phosphorylated in Thr and Tyr residues within the activation loop was Slt2. This confirmed that the use of the hyperactive allele of Pkc1 specifically activated the CWI, but no other MAPK, pathway. No phosphopeptides for kinases of the CWI MAPK module other than Slt2 (namely, Bck1, Mkk1, and Mkk2) were detected in our analysis. This is likely because of their limited abundance in the cell. Estimated amounts of these proteins, as determined via large-scale protein expression analysis (63), ranged approximately from 100 to 2000 molecules per log-phase cell, whereas Slt2 is more abundant (more than 3000 molecules per log-phase cell). Moreover, a 15-fold increase in SLT2 gene expression has been reported to occur upon Pkc1 overproduction, in contrast to the genes encoding upstream kinases of the CWI MAPK module (5).

Insights into Pkc1-CWI Regulation

Given that our experimental design was based on the overexpression of a hyperactive version of Pkc1, this protein was the most prominently detected as hyperphosphorylated. Thus, we have identified a large number of putative phosphosites along the Pkc1 primary sequence. Some of them have been described in earlier phosphoproteomic analyses (13, 50, 64, 65), and some are novel. MAPK pathways are subjected to complex layers of regulation to establish feedback controls to modulate signaling and avoid crosslinking (2). Interestingly, we found up-regulated phosphosites in Pkc1 consistent with the S/T-P MAPK target motif. Given the specific activation of the MAPK Slt2 in our experimental conditions, it is plausible that Slt2 exerts feedback regulatory inputs onto Pkc1, as has been reported to happen on the Rho1-GDP-GTP exchange factor Rom2 and Mkk1/Mkk2 MAPKKs (27, 28). One of the hits found in our analysis matches a putative MAPK target site in Zeo1, a protein for which physical interaction with the CWI sensor protein Mid2 has been reported. It is noteworthy that deletion of the ZEO1 gene leads to constitutive phosphorylation of Slt2 (66), suggesting a role in CWI pathway modulation. Thus, one could speculate that retrophosphorylation of Zeo1 by Slt2 might putatively constitute another feedback control of the pathway.

Putative Novel Pkc1-CWI Outputs

Transcriptional regulators are classical MAPK substrates. Although CWI signaling has been related so far to the positive regulation of transcription factors by Slt2 phosphorylation, it is likely that repressing complexes are also targeted by Slt2 to control gene expression. We have found differentially regulated phosphopeptides containing putative MAPK target motifs in Rgt1 and Tup1 proteins, which are involved in repression of transcription that is relieved by glucose-responsive pathways. Rgt1 is known to be regulated by phosphorylation by both PKA and Snf1 kinases under different conditions (67), whereas regulation by MAPKs has not been described so far. Of interest, one of the target genes of the Rgt1-Tup1-Ssn6-mediated transcriptional regulation (67) encodes hexokinase 2, a protein found to be phosphorylated at Ser15 in our study. Hexokinase 2, besides its role as a glycolytic enzyme, acts as a transcriptional regulator and is phosphorylated in this particular residue when cells are shifted to low glucose medium by a yet unknown kinase (68). The Hxk2 Ser15 phosphosite matches the consensus site for AGC kinases. PKA is unlikely to be involved in such phosphorylation (68). Therefore, it can be hypothesized that Pkc1 might act on Hxk2.

We also found enhanced phosphorylation on proteins encoded by other genes regulated by the Ssn6-Tup1 co-repressor, namely, RNR2 and RNR4. They are ribonucleotide reductase small subunits involved in DNA repair and DNA damage response (69–71). It has been shown that Slt2 is required for the regulation of ribonucleotide reductase gene transcription upon DNA damage (72). Our results suggest that the CWI pathway might also modulate ribonucleotide reductase activity through post-translational modifications, and they are consistent with the reported role of Slt2 in DNA damage response (16).

Oxidative stress is a reported stimulus for the CWI pathway (73). We found enhanced phosphorylation at a MAPK consensus site of Sod1, the cytosolic Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase. Of interest, another up-regulated protein in our analysis, the vacuolar glutathione S-conjugate transporter Ycf1, recently has been found to bind to the Pkc1 activator Rho1 upon induction of oxidative stress by peroxides (74). The identified Ycf1 Ser878 residue fits a putative Pkc1 target motif. Thus, the Pkc1-CWI pathway might be involved in modulating oxidative stress responses through these targets.

Under stress conditions, mRNAs are often sequestered in procession bodies to attenuate bulk translation activity. Heat stress, a well-known stimulus of the Pkc1-CWI pathway, induces procession-body formation (75). Moreover, Pkc1 stimulation via its upstream activating kinases Pkh1 and Pkh2 has been related to the control of procession-body assembly (76). We found enhanced phosphorylation at Ser771 of Dcp2, a subunit of the mRNA decapping enzyme operating in procession bodies. This phosphosite matches an AGC target, suggesting that Pkc1 might directly carry out this particular phosphorylation.

Eisosome Regulation by the CWI MAPK Pathway

The overrepresentation of eisosome components among the proteins with enhanced phosphorylation in Pkc1-CWI activation conditions was remarkable. Both Lsp1 and Pil1 eisosome core paralogs were up-regulated in Thr233 in our dataset. Pkh1 and Pkh2, the two redundant PDK1 homologs required for Pkc1 activation (19), have been reported to control eisosome dynamics through the phosphorylation of Pil1 in various amino acids along the protein, including the Thr233 residue (33, 56). However, the sequence surrounding the Thr233 phosphorylation site, in both Pil1 and Lsp1, does not match the consensus site for PDK1 kinases (49); instead it fits the MAPK phosphorylation motif. We report here that the Slt2 MAPK is necessary for Pkc1-induced phosphorylation of both Pil1 and Lsp1. Moreover, Pil1 and Slt2 have been shown to co-purify in the same protein complexes (77, 78). As Pkc1 and the CWI pathway are downstream of the Pkh kinases, our results are compatible with the view that Pkh1 and Pkh2 modulate eisosome assembly and organization via multiple mechanisms. Indeed, they reveal that at least part of such regulation may be exerted via the Slt2 MAPK. Our identification of up-regulated Pro-directed phosphosites in additional eisosome components, such as Eis1, Seg1, and Pst2, reinforces the idea that the CWI pathway might contribute to regulatory events in these plasma-membrane-associated complexes. Interestingly, Seg1 has recently been reported to be important for eisosome biogenesis and shape during bud development (79). The influence of Pil1 phosphorylation on the regulation of eisosome assembly has been thoroughly studied by different groups using mutants affected in diverse multiple phosphosites, but their conclusions have led to some controversy (33, 52, 53, 56). We have focused on Pro-directed residues Ser230 and Thr233 in Pil1 as putative Slt2 targets, as our phosphoproteomic analysis indicated that at least the latter phosphosite is modified in a CWI-dependent fashion. In our study, mutating these residues to Ala abrogated Pkc1-induced phosphorylation and partially impaired Pil1 function on eisosome organization. Although further experiments will be required in order to unveil the mechanisms by which phosphorylation regulates eisosome function, our results provide, for the first time, evidence that the MAPK Slt2 is involved in such modulation. We thus open new perspectives on the complex regulation of the organization of eisosomes and demonstrate the validity of our global phosphoproteomic approach in uncovering novel targets of Pkc1-CWI signaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the staff at the UCM/PCM Proteomics Unit for valuable help with data analyses and J. Vázquez and P. Navarro for providing the QuiXot software. We thank R. C. Dickson, W. Tanner, and C. Roncero for providing reagents.

Footnotes

* This work was supported by Grant Nos. BIO2010-22369-C02-01 to M.M. and BIO2009-07654 to C.G. from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (Spain), Grant No. S2011/BMD-2414 from Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain), and Program for UCM Research Groups Grant Nos. 920628 and 920685 from BSCH-UCM. V.M. was supported by a contract granted by project S-SAL-0246-2006 from Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain) and Cátedra Extraordinaria de Bebidas Fermentadas UCM. M.J.S. was supported by a fellowship from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (Spain).

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

This article is dedicated in memoriam to Professor Miguel Sánchez Pérez.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- ACN

- acetonitrile

- CWI

- cell wall integrity

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MAPKK

- MAPK kinase

- MAPKKK

- MAPK kinase kinase

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- SILAC

- stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture

- SIMAC

- sequential elution from immobilized metal affinity chromatography

- WT

- wild type.

REFERENCES

- 1. Qi M., Elion E. A. (2005) MAP kinase pathways. J. Cell Sci. 118, 3569–3572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Molina M., Cid V. J., Martin H. (2010) Fine regulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae MAPK pathways by post-translational modifications. Yeast 27, 503–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen R. E., Thorner J. (2007) Function and regulation in MAPK signaling pathways: lessons learned from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1773, 1311–1340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garcia R., Rodriguez-Pena J. M., Bermejo C., Nombela C., Arroyo J. (2009) The high osmotic response and cell wall integrity pathways cooperate to regulate transcriptional responses to zymolyase-induced cell wall stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10901–10911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roberts C. J., Nelson B., Marton M. J., Stoughton R., Meyer M. R., Bennett H. A., He Y. D., Dai H., Walker W. L., Hughes T. R., Tyers M., Boone C., Friend S. H. (2000) Signaling and circuitry of multiple MAPK pathways revealed by a matrix of global gene expression profiles. Science 287, 873–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Rourke S. M., Herskowitz I. (2004) Unique and redundant roles for HOG MAPK pathway components as revealed by whole-genome expression analysis. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 532–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thingholm T. E., Jensen O. N., Larsen M. R. (2009) Analytical strategies for phosphoproteomics. Proteomics 9, 1451–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Godoy L. M., Olsen J. V., de Souza G. A., Li G., Mortensen P., Mann M. (2006) Status of complete proteome analysis by mass spectrometry: SILAC labeled yeast as a model system. Genome Biol. 7, R50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ong S. E., Blagoev B., Kratchmarova I., Kristensen D. B., Steen H., Pandey A., Mann M. (2002) Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1, 376–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gruhler A., Olsen J. V., Mohammed S., Mortensen P., Faergeman N. J., Mann M., Jensen O. N. (2005) Quantitative phosphoproteomics applied to the yeast pheromone signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 4, 310–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li X., Gerber S. A., Rudner A. D., Beausoleil S. A., Haas W., Villen J., Elias J. E., Gygi S. P. (2007) Large-scale phosphorylation analysis of alpha-factor-arrested Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Proteome Res. 6, 1190–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu R., Dephoure N., Haas W., Huttlin E. L., Zhai B., Sowa M. E., Gygi S. P. (2011) Correct interpretation of comprehensive phosphorylation dynamics requires normalization by protein expression changes. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 10, M111.009654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Soufi B., Kelstrup C. D., Stoehr G., Frohlich F., Walther T. C., Olsen J. V. (2009) Global analysis of the yeast osmotic stress response by quantitative proteomics. Mol. Biosyst. 5, 1337–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Nobel H., Ruiz C., Martin H., Morris W., Brul S., Molina M., Klis F. M. (2000) Cell wall perturbation in yeast results in dual phosphorylation of the Slt2/Mpk1 MAP kinase and in an Slt2-mediated increase in FKS2-lacZ expression, glucanase resistance and thermotolerance. Microbiology 146, 2121–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martin H., Rodriguez-Pachon J. M., Ruiz C., Nombela C., Molina M. (2000) Regulatory mechanisms for modulation of signaling through the cell integrity Slt2-mediated pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 1511–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levin D. E. (2011) Regulation of cell wall biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the cell wall integrity signaling pathway. Genetics 189, 1145–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heinisch J. J. (2005) Baker's yeast as a tool for the development of antifungal kinase inhibitors—targeting protein kinase C and the cell integrity pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1754, 171–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nonaka H., Tanaka K., Hirano H., Fujiwara T., Kohno H., Umikawa M., Mino A., Takai Y. (1995) A downstream target of RHO1 small GTP-binding protein is PKC1, a homolog of protein kinase C, which leads to activation of the MAP kinase cascade in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 14, 5931–5938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Inagaki M., Schmelzle T., Yamaguchi K., Irie K., Hall M. N., Matsumoto K. (1999) PDK1 homologs activate the Pkc1-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 8344–8352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roelants F. M., Torrance P. D., Thorner J. (2004) Differential roles of PDK1- and PDK2-phosphorylation sites in the yeast AGC kinases Ypk1, Pkc1 and Sch9. Microbiology 150, 3289–3304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Delley P. A., Hall M. N. (1999) Cell wall stress depolarizes cell growth via hyperactivation of RHO1. J. Cell Biol. 147, 163–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Levin D. E., Bowers B., Chen C. Y., Kamada Y., Watanabe M. (1994) Dissecting the protein kinase C/MAP kinase signalling pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell. Mol. Biol. Res. 40, 229–239 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jung U. S., Sobering A. K., Romeo M. J., Levin D. E. (2002) Regulation of the yeast Rlm1 transcription factor by the Mpk1 cell wall integrity MAP kinase. Mol. Microbiol. 46, 781–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Madden K., Sheu Y. J., Baetz K., Andrews B., Snyder M. (1997) SBF cell cycle regulator as a target of the yeast PKC-MAP kinase pathway. Science 275, 1781–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ray A., Hector R. E., Roy N., Song J. H., Berkner K. L., Runge K. W. (2003) Sir3p phosphorylation by the Slt2p pathway effects redistribution of silencing function and shortened lifespan. Nat. Genet. 33, 522–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flandez M., Cosano I. C., Nombela C., Martin H., Molina M. (2004) Reciprocal regulation between Slt2 MAPK and isoforms of Msg5 dual-specificity protein phosphatase modulates the yeast cell integrity pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 11027–11034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guo S., Shen X., Yan G., Ma D., Bai X., Li S., Jiang Y. (2009) A MAP kinase dependent feedback mechanism controls Rho1 GTPase and actin distribution in yeast. PLoS One 4, e6089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jimenez-Sanchez M., Cid V. J., Molina M. (2007) Retrophosphorylation of Mkk1 and Mkk2 MAPKKs by the Slt2 MAPK in the yeast cell integrity pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 31174–31185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]