Key Points

Cases of cHL may express TCA on the neoplastic cells.

TCA-cHL have nodular sclerosis histology and lack T-cell genotype, with worse outcome compared with TCA-negative cHLs.

Abstract

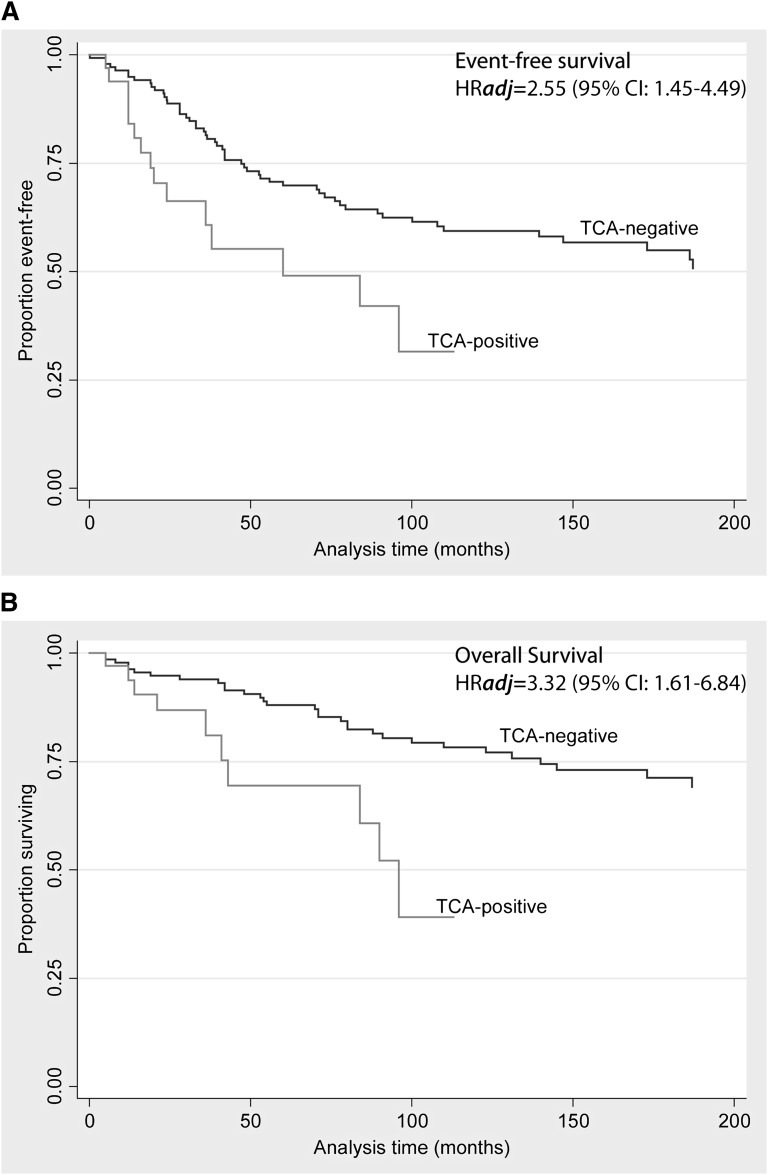

Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells of classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) rarely express T-cell-associated antigens (TCA), but the clinical significance of this finding is uncertain. Fifty cHLs expressing any TCA on the HRS cells (TCA-cHL) were identified in two cohorts (National Cancer Institute, n = 38; Basel, n = 12). Diagnostic pathology data were examined in all cases with additional T-cell receptor γ rearrangements (TRG@) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in a subset of cases. The outcome data were compared with a cohort of cHLs negative for TCA (n = 272). Primary end points examined were event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS). The median age in the TCA-cHL group was 40 years (range, 10-85 years). Seventy percent presented in low stage (stage I/II) at presentation with nodular sclerosis (NS) histology predominating in 80% of cases. Among the TCA, CD4 and CD2 were most commonly expressed, seen in 80.4% and 77.4% of cases, respectively. TRG@ PCR was negative for clonal rearrangements in 29 of 31 cases. During a median follow up of 113 months, TCA expression predicted shorter OS (adjusted hazard ratio [HRadj] = 3.32 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.61, 6.84]; P = .001) and EFS (HRadj = 2.55 [95% CI: 1.45, 4.49]; P = .001). TCA-cHL often display NS histology, lack T-cell genotype, and are independently associated with significantly shorter OS and EFS compared with TCA-negative cHLs.

Introduction

Despite the potentially curable nature of classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), relapse occurs in 30% of patients, with eventual death in a significant proportion. In order to better stratify the risk of adverse outcome in cHL, a number of factors, including clinical and demographic (age, sex, Ann Arbor stage bulky peripheral or mediastinal disease, International Prognostic Score), have been tested in a number of previous studies. Despite the incorporation of several such parameters in a prognostic model, a sizeable fraction of high-risk patients still could not be identified in one study,1 underscoring the need for better biomarkers. In this quest, several recent studies have focused on evaluating tissue-specific predictive biomarkers related either to the microenvironment of cHL2-7 or to antigens expressed on the Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells8-10 with variable success in identifying patients with poor outcomes, although they warrant validation in larger independent cohorts.

On the other hand, the advent of single-cell micromanipulation techniques in the mid-1990s prompted several groups to investigate the underlying genotype of HRS cells, with often conflicting results.11–15 However, with progressive refinements on the technical front, other studies were able to confirm that HRS cells indeed arise from clonal expansions of germinal-center B cells.16–18 Nevertheless, the novel expression of T-cell-associated antigens (TCA)14,19,20 and cytotoxic markers21,22 on the HRS cells in a subset of cases remained enigmatic. Seeking to shed light on this issue, Muschen and coworkers23 set forth to investigate the underlying genotype of HRS cells in 3 cHLs expressing cytotoxic markers using micromanipulated single-cell polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) for T-cell receptor γ rearrangements (TRG@). They found that 1 of the 3 cases, which had uniform perforin expression, evidenced clonal TRG@ in the HRS cells; however, although all 3 cases were CD3 negative, additional T-cell markers were not examined in this study. In a subsequent study, Seitz et al24 examined 13 cases of TCA-expressing cHLs, only 2 of which evidenced clonal TRG@ using single-cell PCR techniques. Although both of these studies furthered our understanding of the relationship between TCA expression and underlying genotype, the prognostic importance of TCA expression or T-cell genotype in HRS cells remained unclear.

In one of the first large-scale studies to investigate the prognostic relevance of TCA expression in cHL utilizing a tissue microarray (TMA)-based approach, Tzankov et al25 identified 12 cases (5%) of cHL (including 9 nodular sclerosis [NS] subtype) that expressed 1 or more TCAs among 259 cases. One of 4 patients with TCA expression in this study died compared with 9 deaths among 105 patients in the control group of cHLs confirmed as TCA negative, suggesting a marginal association between TCA expression and adverse outcome. In a subsequent study from Japan, Asano et al26 identified 27 cases of TCA-expressing cHL (out of 324 cHLs examined [8%]). TCA expression was reported to be independently associated with worse outcome, but histologic subtype or Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) status was not an independent prognostic factor. This series included a relatively low proportion of cases classified as cHL, NS. As such, there is a lack of large-scale clinical data addressing the prognostic significance of TCA expression in a Western population predominated by NS histology.

In this study, we have assembled pathological and clinical data pooled from 2 cohorts (National Cancer Institute [NCI] and Basel), yielding 50 cHLs expressing TCA and a control group of cHL (n = 272) that was tested and found to be TCA negative, to better understand: (1) the histologic/immunophenotypic characteristics of TCA-expressing cHL; and (2) to clarify the prognostic impact of TCA expression on HRS cells in cHL. We identified that an overwhelming majority of cHLs with TCA are characterized by NS histology, predominantly grade 2. CD4 and CD2 are the most frequently expressed TCAs. Furthermore, our study indicates for the first time that TCA-expression status is an important and independent predictor of adverse outcome when compared with TCA-negative cHLs.

Methods

Case selection

Cases were culled from 2 groups yielding a total of 50 TCA-positive cHLs: 38 cases were identified through the consult database of the Hematopathology Section at the NCI between 1997 and 2010, and 12 additional TCA-positive cases described previously by Tzankov et al25 (Basel) were included as well. To assess the clinical significance of TCA expression, a cohort extensively tested for TCA expression and determined to be TCA negative was provided by the Institute of Pathology, University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland. Data on age, sex, B-symptoms, treatment, and outcome (relapse and deaths), as well as pathology data, were available in this cohort. This group was used for comparative outcome analyses detailed below.

This study, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the NCI and the Institutional Review Board in Basel.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Histologic examination.

Histologic sections (3-4 µm) obtained from 10% formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for microscopic examination. All NCI cases were examined independently by 2 expert hematopathologists (E.S.J. and S.P.). Initially, subtyping of cHL was established using the World Health Organization 2008 schema,27 with further grading of NS cases as grade 1 (NS1) or grade 2 (NS2) utilizing the criteria of the British National Lymphoma Investigation28 and adopted by the 2001 World Health Organization classification.29 Grading was performed in cases within the NCI cohort. Additionally, a number of other morphologic parameters examined previously by von Wasielewski et al30,31 were evaluated in all cases with NS histology (ie, proportions of HRS cells, morphologic atypia of HRS cells, syncytial growth pattern, confluent necrosis, background eosinophilia, and lymphoid depletion) using the same criteria as the above investigators.

Immunohistochemical staining.

Immunohistochemical staining of the NCI cases was performed using a comprehensive antibody panel. Staining was performed on an automated immunostainer either from Dako or Ventana platform according to the manufacturer’s instructions with a DAB detection kit. Antigen retrieval was performed using either 10 mM citrate at pH 6 or high pH (with EDTA pH 9.0 or Dako high-pH buffer). Additional immunostains including TCA were performed in cases submitted to the NCI, either at the time of initial case review or during rereview as part of this study (CD2 and CD7). Notably, the clones of the antibodies used remained consistent across the time period the reported cases were collected.

Evaluation of TCA expression.

HRS cells are often rosetted by T cells with an associated brisk T-cell infiltrate in the background milieu. Consequently, nonspecific adsorption from surrounding T cells could potentially confound the interpretation of TCA expression on the HRS cells. Cases were considered TCA positive if more than 10% of HRS cells showed partial or complete membrane staining for TCA and readily distinguished from adjacent T-cells. Cytoplasmic staining for TCA was also scored as positive if observed in more than 5% of HRS cells. Such cases typically exhibited distinct dot-like/blob-like staining in the Golgi region. Special attention was paid to clusters of HRS cells, which were not associated with reactive lymphocytes in assessing TCA expression.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization for EBV-encoded RNA (EBER) was performed on the NCI cases for which FFPE blocks were available using previously published methods.32

PCR for immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene rearrangements

DNA was extracted from FFPE tissue blocks using a standard protocol. For immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (IGH@) rearrangements, DNA amplification by PCR was conducted using Framework Region III primers. Additional seminested PCR amplifications were carried out using primers to Framework Region II of IGH@ according to the method of Ramasamy et al.33 Cases negative for IGH@ rearrangement were further studied for rearrangements of the IGκ locus using the BIOMED-2 primer sets described by van Dongen et al34 and supplied by InVivoScribe Technologies (IGK Gene Clonality Assay-ABI Fluorescence Detection).

For T-cell receptor gene (TCR@) rearrangements, amplification was done using primers to TRG@ as previously described.32 Additionally, in a subset of cases after May 2009, a single multiplexed PCR reaction was performed as described by Lawnicki et al,35 using primers that interrogate all of the known Vγ family members and the Jγ1/2, JP1/2, and JP joining segments. To allow for fluorescence detection, each joining region primer was covalently linked to a unique fluorescent dye. All of the amplification reactions were carried out in duplicate. The products were analyzed by acrylamide gel or capillary electrophoresis. The results were interpreted in conjunction with a blank (water), polyclonal, and monoclonal control. Amplification for TRG@ rearrangements in the Basel cases was performed as per Meier et al.36

Laser capture microdissection and DNA extraction

Next, 4 µm FFPE tissue sections of 3 selected NCI cases were stained with Mayer’s hematoxylin solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Approximately 1000 tumor cells per case were microdissected using the Arcturus XT Microdissection System (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. Further PCR reactions for TRG@ were performed as detailed above.

Clinical data, outcome, and analysis

Clinical variables evaluated in this study included age, gender, clinical stage (I/II vs III/IV), and therapy (ABVD [doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine] vs other). Pathologic variables included in the outcome modeling were NS histology (dichotomized as NS vs non-NS), CD15 negativity, and expression of any TCA on the HRS cells. Outcome-related measures that were collected included actuarial status, treatment response (complete and partial remission, disease progression), and disease relapse. Treatment-response information was available only in the NCI cohort. The primary end points modeled were event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS). Specifically, EFS time was measured as the period from the date of the diagnostic biopsy until either evidence was obtained of an event (relapse, progressive disease, or death) or date of last contact, whichever was the earliest.

Survival was analyzed using Cox regression37 for both end points. Because missing values occurred in some predictors, we created 200 completed versions of the data set using multiple imputation with chained equations38 using a previously written SAS macro. Results were obtained on each of the 200 data sets and combined following Rubin’s rules.39 All variables mentioned above entered the Cox regression models. Two additional models were estimated to perform preplanned interaction analysis of expression of any TCA with type of therapy and with histology. Furthermore, we checked the proportional hazards and additivity assumptions of the model by assessing significance of interactions with time and pairwise interactions, respectively, at a false discovery rate of 5%.40 All reported P values are based on 2-tailed distributions. Results were considered significant for values of P < .05. All statistical models were performed within SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) or Stata 11 (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

Results

The demographic features, histologic subtypes, treatment details, and response and outcome data for all TCA-positive cases from both cohorts tabulated by TCA expression status are summarized in Table 1. In the univariate analyses, there were no differences in age, proportions with male sex, stage (low vs high), or B-symptoms between TCA-positive and TCA-negative cases. However, the proportion of cases with NS histology was significantly overrepresented in the TCA-positive group (P = .002, χ2 test)

Table 1.

Baseline clinical, pathologic, and outcome data on patients in both cohorts stratified by TCA expression status

| TCA status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||||

| Value | N examined | Value | N examined | P | |

| Age, median (range) | 40 (10-85) | 44 | 36 (9-87) | 191 | .53* |

| Male sex, n (%) | 22 (51) | 44 | 108 (57) | 191 | .51† |

| B-symptoms, n (%) | 10 (43) | 45 | 41 (41) | 100 | .82† |

| Ann Arbor stage, n (%) | .31† | ||||

| I/II | 23 (70) | 33 | 66 (60) | 110 | |

| III/IV | 10 (30) | 33 | 44 (40) | 110 | |

| Histology, n (%) | .002‡ | ||||

| Nodular sclerosis | 40 (80) | 50 | 156 (57.3) | 272 | |

| Mixed cellularity | 4 (8) | 50 | 88 (32.3) | 272 | |

| Lymphocyte rich | 0 (0) | 50 | 9 (3.3) | 272 | |

| Lymphocyte depleted | 1 (2) | 50 | 5 (1.8) | 272 | |

| cHL, not further subclassified | 5 (10) | 50 | 14 (5.1) | 272 | |

| Treatment (n = 26) | |||||

| Chemotherapy, ABVD | 24 (72.7)§ | 32 | 43 (44.3) | 97 | |

| Chemotherapy, COPP | 1 (3.03) | 32 | 30 (31) | 97 | |

| Other chemotherapy | 8 (24.2) | 32 | NA | ||

| Radiation only | 0 (0) | 32 | 24 (24.7) | 97 | |

| Response (n = 25) | |||||

| Complete | 18 (72) | 25 | NA | ||

| Partial | 5 (20) | 25 | NA | ||

| No | 2 (8) | 25 | NA | ||

| Outcome, n (%) | |||||

| Relapsed | 11 (35) | 32 | 37 (25.5) | 145 | .3† |

| Died | 11 (30) | 36 | 38 (26.2) | 145 | .59† |

COPP, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; NA, data not available.

Mann-Whitney U test was used for differences in age.

χ2 was used for differences in proportions.

χ2 performed for histology dichotomized as NS and non-NS histology.

Ten patients additionally received radiotherapy; in one, bleomycin was omitted owing to pulmonary dysfunction.

Histology and routine immunohistochemical features of TCA-positive cHL

Forty of 50 cases (80%) showed NS histology, with NS2 morphology predominating in 68% of cases. Features characteristic of NS histology (ie, marked capsular fibrosis, prominent thick fibrous septae dividing the lymphoid tissue into nodules containing numerous HRS cells, including lacunar variants) were present. The background milieu was predominated by lymphocytes with eosinophils, aggregates of histiocytes (Figure 1), and neutrophilic collections present in a proportion of cases. Three cases notably showed a predominant intrasinusoidal distribution of HRS cells resembling anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). Additionally, 1 case was composite cHL and follicular lymphoma grade 3 (Figure 2). In this case, further subtyping of the cHL component (NS vs non-NS) was not performed because the cHL component was predominantly interfollicular. There were no distinctive histologic features in the TCA-positive cases when compared with 13 unselected control NS cases.

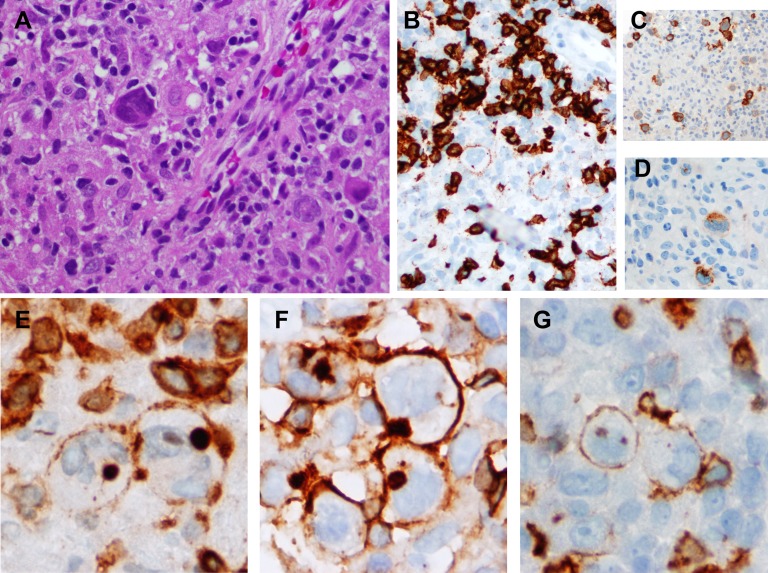

Figure 1.

cHL expressing TCAs. (A) Scattered HRS cells amid a background rich in histiocytes and lymphocytes. (B-D) The neoplastic cells express variable weak CD20 (CD20 immunoperoxidase, ×200), uniform CD30 (CD30 immunoperoxidase, ×100), and CD15 (CD15 immunoperoxidase, ×200 respectively. (E-G) CD3, CD4, and CD5 expression, respectively, on the HRS cells. There is membrane staining for CD3 (CD3 immunoperoxidase, ×400), CD4 (CD4 immunoperoxidase, ×400), and CD5, focally (CD5 immunoperoxidase, ×400); additionally, CD3 and CD4 show blob-like cytoplasmic staining.

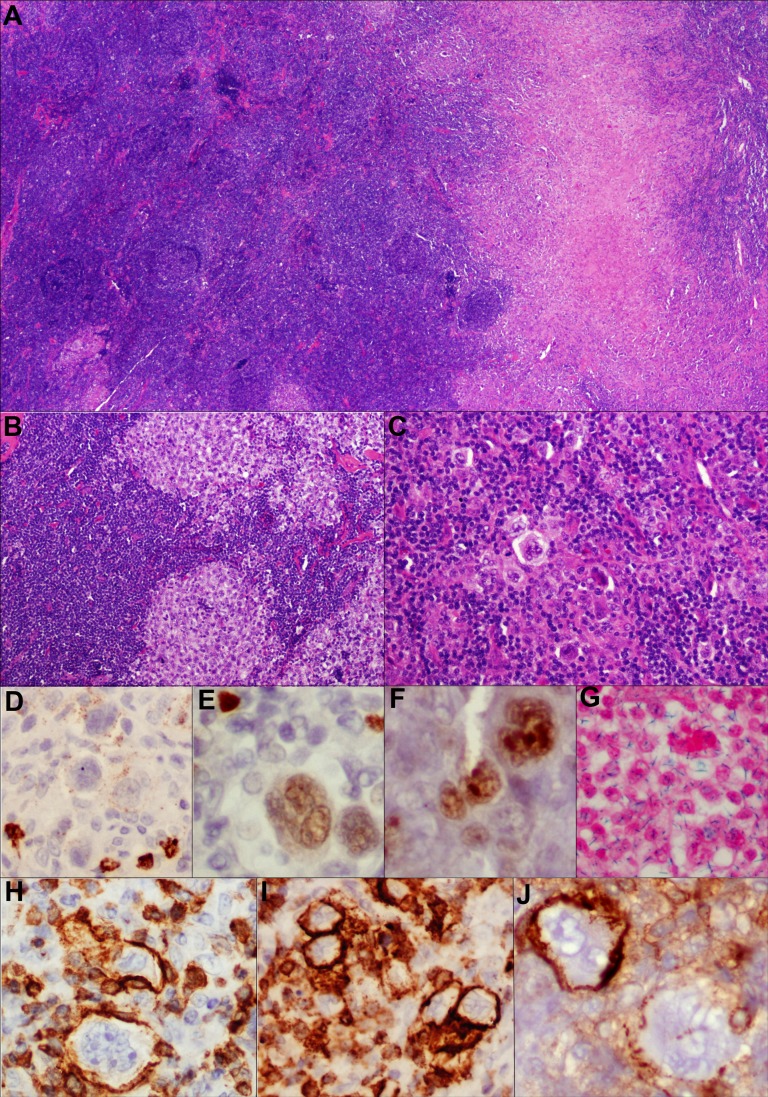

Figure 2.

Composite lymphoma comprising cHL and follicular lymphoma. TCA in cHL component. (A) Low-power view of the composite histologic components (H&E, ×100). (B,C) Higher-power view depicting morphologically distinct components; ie, follicular lymphoma grade 3 and cHL, respectively (H&E, ×200). (D-J) Various markers expressed within the HRS cell component with very weak and variable CD20 (D), PAX-5 (E), and BCL-6 (F) expression (immunoperoxidase, ×200, ×400, ×400). (G) These cells are EBER negative (in situ hybridization, ×400). (H-J) TCA expression in cHL component. Among the T-cell markers, there is strong CD3 (H), CD2 (I), and CD4 (J) expression on membrane of the HRS cells (immunoperoxidase, ×400, ×400, ×400). Notably, CD4 was variable in this case with adjoining scattered CD4-negative HRS cells, lending credence to the specificity of staining.

Relapse histology.

A total of 8 NCI cases relapsed and had details available on the relapse histology. Six were nodal relapses, 1 was mediastinal, and 1 was an extranodal relapse in the lung. Slides of the sequential relapse biopsy specimens were available in 4 cases, of which 2 were notable. One of the cases displayed features compatible with a gray zone lymphoma between cHL and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma at relapse. A second case showed a prominent tissue eosinophilia with eosinophilic microabscesses at relapse.

Routine immunohistochemistry.

PAX-5 was positive on the HRS cells in 26 of 34 cases (77.4%), whereas in a third of the cases (31%) the HRS cells expressed some CD20. Notably, the intensity of PAX-5 was always weak on the HRS cells and CD20 staining was never uniform and strong, conforming to the expected staining pattern in cHL. In a minority of cases, the HRS cells were positive for either CD79a (in 3 of 22) or OCT-2 (in 1 of 5) and CD45 (in 2 of 13). All 26 cases tested for EBV (24 EBER and 2 EBV-latent membrane protein1) were negative in the HRS cells. All 25 cases tested for anaplastic lymphoma kinase were negative, including the 3 cases characterized by a sinusoidal growth pattern; these 3 cases were additionally positive for PAX-5. There were variable numbers of background small B cells in 29 cases that could be evaluated. Scattered residual lymphoid follicles were apparent in 4 cases. CD3-positive T-cell rosettes were apparent in some of the cases. All cases showed preponderance of CD4- compared with CD8-expressing background T cells.

TCA expression in TCA-positive cases.

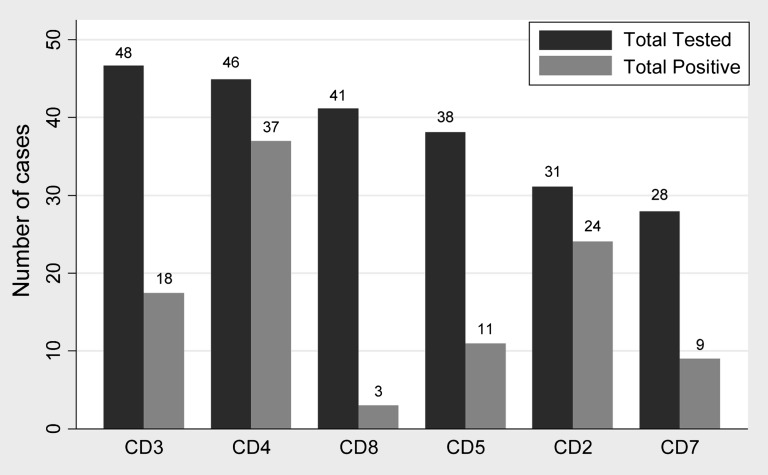

Among TCA, CD4 and CD2 were most commonly expressed, seen in 37 of 46 (80.4%) and 24 of 31 (77.4%) cases, respectively (Figure 3). Expression of TCAs in any case was never uniform and widespread; only a proportion (10% to 35%) of HRS cells stained positively in most cases. Even in any single case, some TCAs stained a greater proportion of HRS cells than other TCAs. The two most frequently coexpressed TCAs were CD4 and CD2 (seen in 16 of 22 cases). Typically, CD2 and CD7 stains displayed a greater proportion of cells with incomplete staining patterns (Figure 4). In a minority of cases, CD3 and CD4 showed blob-like cytoplasmic staining with a Golgi distribution. Among 2 CD8-positive cases in the NCI cohort, 1 coexpressed CD2 and CD7 with uniform expression of all 3 cytotoxic markers (TIA-1, granzyme B, and perforin) on most of the HRS cells (Figure 4C), and the other CD8-positive case (representing a composite CHL and follicular lymphoma) was notable for coexpression of multiple TCA (CD2, CD3, CD4, and CD5) on the HRS cells. Because archival material was not available, additional cytotoxic markers could not be tested be in this latter case.

Figure 3.

Summary of TCA expression. CD4 and CD2 were the most commonly expressed antigens. The order of frequency of TCA expression was CD4 (80.4%) > CD2 (77.4%) followed by CD3 (38%), CD7 (31%), CD5 (28.2%), and CD8 (7%).

Figure 4.

Evaluation of staining for T-cell markers and TCA expression. (A) Indeterminate/negative staining showing lack of definitive membrane accentuation on the HRS cells in areas rosetted by T cells. Free area of HRS cell membrane (denoted with white arrow) opposite to areas of partial rosetting lacks distinctive membrane staining (CD4 immunoperoxidase, ×400). (B) Indeterminate staining showing complete rosetting by CD4-positive T cells without apparent accentuation on the HRS cells (CD4 immunoperoxidase, ×400). (C) Positive staining showing clusters of HRS cells with definitive but incomplete membrane staining. Typically, CD2 and CD7 stains showed areas with frequent incomplete staining patterns (CD2 immunoperoxidase, ×200). Cases with such staining patterns often showed more complete staining pattern in other areas of the same cases or displayed convincing positivity for another T-cell marker. (D) Definitive, complete circumferential membrane staining in clusters of HRS cells (CD2 immunoperoxidase, ×200). (E) Membrane and cytoplasmic Golgi staining for CD8 (immunoperoxidase, ×400). (F) Strong and diffuse cytoplasmic staining for perforin. This case was unique in that almost all HRS cells showed uniform, strong expression of perforin (perforin immunoperoxidase, ×400).

PCR for clonality studies

In the NCI cohort, a total of 18 cases were informative (with amplifiable DNA) for analysis of immunoglobulin (IG) genes. Three of these showed a clonal IG gene rearrangement using whole sections; all 3 cases were noted to contain a high proportion of HRS cells representing 15% to 30% of the cellular population. In the TRG@ analysis, none of the 21 NCI cases showed clonal TRG@ using whole sections. Microdissection of single HRS cells was performed on 3 cases using a unique frame-based membrane technique developed in our laboratory that allows for more precise extraction of HRS cells with minimal contamination from surrounding lymphocytes.41 Two of these cases were informative with amplifiable DNA and did not show clonal TRG@ in either case. The DNA quality and concentration were checked and noted to be adequate (≥300 bp) in both cases, thus ruling out a false-negative reaction.

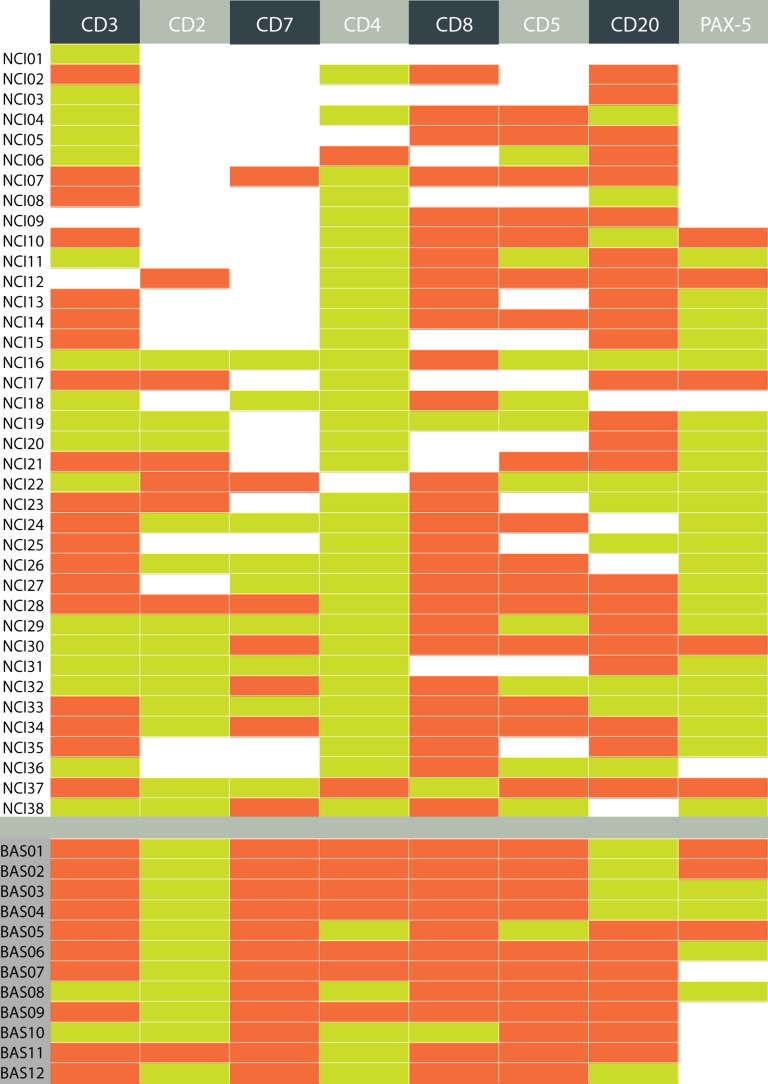

As reported previously by Tzankov et al,25 10 cases from the Basel cohort were examined by single-cell microdissection; 2 of these showed clonal TRG@ in the microdissected HRS cells. Figure 5 shows a depiction of immunohistochemistry results and PCR results in all 50 TCA-positive cases combining both cohorts.

Figure 5.

Details of immunohistochemical data on HRS cells in all 50 TCA-positive cases. In the IG@ PCR, NCI cases 21, 22, and 26 and Basel cases 11 and 12 were clonal. In the TRG@ PCR, only Basel cases 1 and 2 showed clonal TRG@. Green, positive; orange-red, negative; blank/white, missing/data not available.

Outcome analysis

The summary of chemotherapy regimens and the treatment response of the patients in the NCI cohort are detailed in Table 1. Notably, 2 patients had a history of prior (n = 1) or concurrent/composite (n = 1) follicular lymphoma.

Cohort characteristics and univariate analyses.

The Basel cohort comprised 12 TCA-positive cases among a total of 269 cases of cHL.25 Treatment information was available only in a subset of these patients: 58 treated with ABVD, 32 with COPP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone), and 28 with radiation only. All treatment regimens were considered ABVD equivalents for analysis purposes. Initial analysis indicated that there was no significant difference in age or proportion of cases stratified by sex, stage, and histology between the two cohorts (data not shown). A significant subset of patients with available treatment information in the NCI cohort was treated using an ABVD-based regime.

Data on some of the histologic factors (eg, tissue eosinophilia, neutrophilic abscesses) were not available in the Basel cohort and could therefore not be modeled. However, we examined some of these histologic factors individually within the NCI cohort. Fifteen of 36 cases in the NCI cohort showed prominent tissue eosinophilia using the criteria employed by von Wasilieski et al30; however, there was no significant difference in EFS or OS between the 2 groups stratified by tissue eosinophilia (P = .891 and .904, log-rank test; data not shown).

Pooled analyses (TCA-positive and TCA-negative cases).

All subsequent analyses detailed below represent pooled data across both cohorts. During a median follow up of 113 months (range, 41-210 months; 25th and 75th percentile), 11 deaths (0.084/patient-year), and 17 events (0.147/patient-year) were observed in the TCA-cHL group. In the TCA-negative group, there were 38 deaths (0.02 deaths/patient-year) and 59 events (0.049 events/patient-year). The final variables included in the multiple imputation Cox model without interaction terms were age, sex, stage (I/II vs III/IV), histology (NS vs non-NS), CD15 negativity, and TCA expression status. See Table 2 and Figure 6 for the data on analyses of OS and EFS for Cox models without interactions.

Table 2.

Summary of OS and EFS in the noninteraction multivariable Cox regression models

| Parameter | Hazard ratio | Lower 95% CL | Upper 95% CL | Pr > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS (n = 212) | ||||

| Age | 1.041 | 1.023 | 1.059 | <.001 |

| Sex | 1.349 | 0.784 | 2.321 | .280 |

| Stage | 1.094 | 0.578 | 2.073 | .782 |

| Histology | 1.355 | 0.753 | 2.439 | .311 |

| CD15 negativity | 1.641 | 0.879 | 3.062 | .120 |

| TCA status | 3.320 | 1.611 | 6.842 | .001 |

| EFS (n = 213) | ||||

| Age | 1.019 | 1.005 | 11.032 | .006 |

| Sex | 1.411 | 0.917 | 2.172 | .118 |

| Stage | 1.541 | 0.963 | 2.467 | .072 |

| Histology | 1.263 | 0.799 | 1.995 | .317 |

| CD15 negativity | 1.120 | 0.673 | 1.862 | .663 |

| TCA status | 2.556 | 1.455 | 4.490 | .001 |

Only age and TCA status were independently associated with outcome in both OS and EFS analyses.

CL, confidence limit.

Figure 6.

TCA expression impacts (A) EFS and (B) OS.

Cox model with interactions.

Additionally, we constructed further Cox models for EFS and OS adding, one at a time, interaction terms of TCA status with histology and with type of therapy. The interaction term “TCA status*histology” has a strong but statistically nonsignificant effect in the OS (P = .12) as well as EFS (P = .24) analyses. Furthermore, in 2 separate models for OS and EFS, we included ABVD therapy (ABVD vs other) as well as its interaction with TCA status (TCA status*ABVD). The interaction term “TCA status*ABVD” was not significant in either analysis. However, ABVD therapy was associated with better outcome in the OS analysis (hazard ratio [HR], 0.25 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.08-0.73] for TCA-negative patients; HR, 0.21 [95% CI, 0.04-1.02] for TCA-positive patients). In this latter interaction Cox model, only TCA expression (HR, 4.29 [95% CI, 1.77-10.40] for patients under ABVD therapy; HR, 3.67 [95% CI, 1.91-14.75] for non-ABVD-treated patients) and age (HR, 1.03 [95% CI, 1.01-1.05]) remained independently significant as predictors of adverse outcome.

Impact of individual TCAs.

Using a multiple imputation analyses with 20 imputations, we constructed several separate multivariable models separately including each of the individual TCA as a predictor in addition to the basic model including age, sex, stage, histology, and CD15 status. Based on these models, we included the TCA with the lowest P value that identified CD7 (P = .005), using which we performed a forward selection of further TCA in a multivariable model including the basic model and CD7. No other TCA could improve the model fit further, indicating that CD7 is the most important predictor of outcome in the OS analysis. Likewise, in the EFS analysis, only CD4 and CD7 remained significant predictors of EFS.

Discussion

In this study, we sought to investigate the clinical and biological significance of TCA expression in a series of cases of cHL compiled from the United States and Central Europe. Our study indicates that TCA expression is most often encountered in cHL, NS, with an overrepresentation of NS2 histology. Sixty-eight (68%) of the TCA-positive cases were classified as NS2. In addition, our study indicates that expression of any TCAs on the HRS cells is associated with adverse outcome independent of disease stage. Hence, routine testing for TCAs at diagnosis may aid in the identification of cHLs with inferior survival. A recent study identified that lineage-inappropriate gene expression is specific to cHL and ALCLs (as compared with other lymphomas) and may occur as a consequence of derepression of an endogenous long terminal repeat, which in turn leads to a sustained cell survival dependent on a persistent autocrine loop of colony-stimulating factor and colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor activation in HRS cells.42 Moreover, those authors provided evidence that silencing of the B-cell program in cHL may be required for HRS cell survival. Their work provides a possible explanation for the adverse clinical impact of TCA expression.

Several earlier19,20,23,43 studies noted instances of cHL expressing TCA on the HRS cells. The unifying thread of information gleaned from these studies indicates that despite aberrant TCA expression on HRS cells, an underlying T-cell genotype was uncommon and present only in a minority of cases.23,24 Furthermore, these studies were either case reports or smaller case series in which the major focus was on elucidating the relationship between TCA expression and an underlying genotype, with limited follow-up information. Consequently, the broader clinical significance of TCA expression on HRS cells remained unclear. Furthermore, testing for a panel of TCAs (other than CD3) is infrequently performed in routine cases diagnosed as cHL. As such, the exact incidence of aberrant TCA in cHL was not well established. We show that routine testing of cHLs for a more extensive TCA panel (including CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7, and CD8), at least in cases with NS2 histology, may identify a subset of cHLs with worse outcome.

One of the first large series to systematically investigate TCA expression in cHL and its correlation with underlying genotype was undertaken by Tzankov et al,25 who identified 12 cases (5%) of CHL (including 9 of the NS subtype) that expressed 1 or more TCAs among 259 cases using a tissue TMA-based approach. Further PCR studies using microdissection in 10 TCA-positive cases in this study yielded 2 cases with clonal TRG@.25 With regards to the criteria for establishing TCA positivity, this study required that >20% of the HRS cells had to have complete membrane staining to be considered positive, which is appropriate with a TMA-based approach. These authors found good correlation between parallel TMA and complete sections with respect to the percentage of HRS cells exhibiting TCA positivity. The NCI cases, on the other hand, were stained using only complete sections; hence, we used a slightly lower threshold (>10%) for TCA expression because we were better able to assess the spatial distribution and extent of positivity on the HRS cells, affording discrimination of true and nonspecific positivity. Nonetheless, the rank order of frequency of TCA expression (CD4 > CD2 > CD5 > CD8) in our study is in agreement with the previously published data.25

HRS cells are characterized by constant, albeit weak expression of PAX-5 protein,44,45 but otherwise repressed the B-cell program. TCA expression on HRS cells may be consequent to critically low levels of PAX-5, because repression of PAX-5 has been shown to convert mature B cells into functional T lymphocytes.46 As expected in cHL, most cases showed weak positivity for PAX-5, although a small subset of cases was totally negative for PAX-5, possibly providing a mechanism for upregulation of TCA. Although PAX-5 expression is generally considered strong evidence for a B-cell lineage, it has been demonstrated in a subset of mature T-cell lymphomas,47 including ALCL attributable to extra copies of the PAX5 gene.48 Three cases with sinusoidal involvement were observed in our study, but the diagnosis of ALCL was excluded based on the typical microenvironment of cHL, absence of clonal TRG@ in the 2 cases tested, and negative anaplastic lymphoma kinase expression in all 3. On the other hand, cases of composite lymphomas similar to the one depicted in Figure 2 have been described to contain clonally identical but morphologically distinct follicular lymphoma and cHL components,49,50 although TCA expression was not examined in either of these studies. Such cases further affirm that the observed TCA expression represents aberrancy in an underlying B-cell malignancy rather than connotes T-cell lymphoma.

From the prognostic standpoint, Tzankov et al25 noted that 1 of 4 patients with TCA expression in their study died compared with 9 deaths among 105 patients in the control group of cHLs determined to be TCA negative, suggesting a marginal association between TCA expression and adverse outcome. A more recent study from Japan by Asano and coworkers26 examined 324 patients with cHL (including 167 with NS histology), most of whom were treated with an ABVD-based regimen. Asano et al employed a limited panel including some T-cell markers (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD45RO) and cytotoxic markers (TIA-1 and granzyme B). Cases expressing T-cell/cytotoxic markers presented at a younger age and were associated with worse outcome. Most of the T-cell/cytotoxic-marker-positive cases were present in the NS/NS2 subgroup of patients,26 in agreement with our findings. The adverse outcome reported in the TCA group is in keeping with our findings, although our control group was more homogenous and comprised an extensively TCA-tested group of cHL patients.

There are a few limitations in our study that deserve further consideration. First, from the design standpoint, this is a retrospective study representing a pool of TCA-positive cases from two cohorts, wherein the NCI cohort was essentially enriched for only TCA-expressing cHLs, whereas the Basel cohort comprised a mix of few TCA-positive and many TCA-negative cases from a well-characterized cohort with much longer follow-up duration compared with the NCI cohort. Consequently, we initially feared that there might have been some confounding in the interpretation of the prognostic relevance of TCA expression because the effects of the cohort on the analysis cannot be separated. Even so, we did not expect this to be a significant issue insofar as patients in both cohorts were culled from Western populations, were largely homogenous with respect to demographic covariates (age, sex, stage) examined, and contained proportions of cases with NS histology and therapy regimens. Secondly, we could not assess the influence of the International Prognostic Factor Project score because we did not have data on hemoglobin, white cell count, and lymphocyte count at presentation as a consequence of cases originating from multiple referring institutions. Lastly, we were concerned that differences in treatment regimens within and between the cohorts may have impacted outcome. To this end, we modeled a binary variable (ABVD therapy vs other) as well as an interaction term (ABVD therapy*TCA expression) in the outcome analyses extending the multivariable Cox models by these terms. In this latter analysis, TCA expression status remained a significant predictor of outcome, attesting to the independent prognostic significance of TCA expression status.

Despite these limitations, the current report represents the largest series to date that details the morphologic spectrum and associated adverse outcome of TCA-positive cHLs. Although cHL with expression of TCAs probably represents only a small fraction of cHLs, our findings support the inclusion of additional T-cell markers in the NS subgroup at diagnosis to aid in better risk stratification of this subgroup of cHL. Further independent validation of these findings in a large, single-institution cohort will clarify the importance of our findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the immunohistochemistry laboratory staff for accommodating the research requests in this project amidst their regular workload and Liqiang Xi for his assistance with the technical and interpretive aspects of PCRs performed after microdissection. Lastly, the authors thank Payal Sojitra (resident pathologist) for help with the image composites and careful proofing.

This study was supported by the intramural budget of the Center for Cancer Research, NCI.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: G.V. designed the study, performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; A.T.G. and J.Y.S. performed the research; F.C.E. and J.C.H performed the research pertaining to the laser capture microdissection; A.T. and S.D. contributed cases, provided follow-up data, and performed the research; G.W.H and M.K. analyzed the data; S.X.P. and M.R. performed the research; E.S.J. designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for G.V. is Department of Pathology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, IL.

The current affiliation for F.C.E. is Department of Dermatology, University Medical Center, Eberhard Karls University Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany.

Correspondence: Girish Venkataraman, Department of Pathology, Building 110 Room 2222, 2160 S 1st Ave, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, IL 60153; e-mail: gvenkat@lumc.edu; or Elaine S. Jaffe, Building 10, Room 2B 42, MSC-1500, 10 Center Drive, National Institutes of Health Bethesda, Maryland 20892; e-mail: elainejaffe@nih.gov.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin’s disease. International Prognostic Factors Project on Advanced Hodgkin’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(21):1506–1514. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steidl C, Lee T, Shah SP, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(10):875–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzankov A, Matter MS, Dirnhofer S. Refined prognostic role of CD68-positive tumor macrophages in the context of the cellular micromilieu of classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Pathobiology. 2010;77(6):301–308. doi: 10.1159/000321567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farinha P, Rodrigues S, Fernandes T, et al. Lymphoma Associated Macrophages Predict Survival in Uniformly Treated Patients with Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma. San Antonio, TX: United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chetaille B, Bertucci F, Finetti P, et al. Molecular profiling of classical Hodgkin lymphoma tissues uncovers variations in the tumor microenvironment and correlations with EBV infection and outcome. Blood. 2009;113(12):2765–3775. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvaro T, Lejeune M, Salvadó MT, et al. Outcome in Hodgkin’s lymphoma can be predicted from the presence of accompanying cytotoxic and regulatory T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(4):1467–1473. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alvaro-Naranjo T, Lejeune M, Salvadó-Usach MT, et al. Tumor-infiltrating cells as a prognostic factor in Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a quantitative tissue microarray study in a large retrospective cohort of 267 patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46(11):1581–1591. doi: 10.1080/10428190500220654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Portlock CS, Donnelly GB, Qin J, et al. Adverse prognostic significance of CD20 positive Reed-Sternberg cells in classical Hodgkin’s disease. Br J Haematol. 2004;125(6):701–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rassidakis GZ, Medeiros LJ, Vassilakopoulos TP, et al. BCL-2 expression in Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells of classical Hodgkin disease predicts a poorer prognosis in patients treated with ABVD or equivalent regimens. Blood. 2002;100(12):3935–3941. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.12.3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doussis-Anagnostopoulou IA, Vassilakopoulos TP, Thymara I, et al. Topoisomerase IIalpha expression as an independent prognostic factor in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(6):1759–1766. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Küppers R, Rajewsky K, Zhao M, et al. Hodgkin's disease: Hodgkin and Reed Sternberg cells picked from histological sections show clonal immunoglobulin gene rearrangements and appear to be derived from B cells at various stages of development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(23):10962–10966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hummel M, Ziemann K, Lammert H, et al. Hodgkin’s disease with monoclonal and polyclonal populations of Reed-Sternberg cells. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(14):901–906. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510053331403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delabie J, Tierens A, Gavriil T, et al. Phenotype, genotype and clonality of Reed-Sternberg cells in nodular sclerosis Hodgkin’s disease: results of a single-cell study. Br J Haematol. 1996;94(1):198–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al Saati T, Galoin S, Gravel S, et al. IgH and TcR-gamma gene rearrangements identified in Hodgkin’s disease by PCR demonstrate lack of correlation between genotype, phenotype, and Epstein-Barr virus status. J Pathol. 1997;181(4):387–393. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199704)181:4<387::AID-PATH781>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Küppers R, Hansmann ML, Rajewsky K. Clonality and germinal centre B-cell derivation of Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells in Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol. 1998;9(Suppl 5):S17–S20. doi: 10.1093/annonc/9.suppl_5.s17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanzler H, Küppers R, Hansmann ML, et al. Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells in Hodgkin’s disease represent the outgrowth of a dominant tumor clone derived from (crippled) germinal center B cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184(4):1495–1505. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hummel M, Marafioti T, Stein H. Clonality of Reed-Sternberg cells in Hodgkin’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(5):394–395. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902043400518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marafioti T, Hummel M, Foss HD, et al. Hodgkin and reed-sternberg cells represent an expansion of a single clone originating from a germinal center B-cell with functional immunoglobulin gene rearrangements but defective immunoglobulin transcription. Blood. 2000;95(4):1443–1450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falini B, Stein H, Pileri S, et al. Expression of lymphoid-associated antigens on Hodgkin’s and Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin’s disease. An immunocytochemical study on lymph node cytospins using monoclonal antibodies. Histopathology. 1987;11(12):1229–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1987.tb01869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadin ME, Muramoto L, Said J. Expression of T-cell antigens on Reed-Sternberg cells in a subset of patients with nodular sclerosing and mixed cellularity Hodgkin’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1988;130(2):345–353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oudejans JJ, Kummer JA, Jiwa M, et al. Granzyme B expression in Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1996;148(1):233–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krenacs L, Wellmann A, Sorbara L, et al. Cytotoxic cell antigen expression in anaplastic large cell lymphomas of T- and null-cell type and Hodgkin’s disease: evidence for distinct cellular origin. Blood. 1997;89(3):980–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müschen M, Rajewsky K, Bräuninger A, et al. Rare occurrence of classical Hodgkin’s disease as a T cell lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2000;191(2):387–394. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seitz V, Hummel M, Marafioti T, et al. Detection of clonal T-cell receptor gamma-chain gene rearrangements in Reed-Sternberg cells of classic Hodgkin disease. Blood. 2000;95(10):3020–3024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tzankov A, Bourgau C, Kaiser A, et al. Rare expression of T-cell markers in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(12):1542–1549. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asano N, Oshiro A, Matsuo K, et al. Prognostic significance of T-cell or cytotoxic molecules phenotype in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(28):4626–4633. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th. Lyons, France: IARC press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haybittle JL, Hayhoe FG, Easterling MJ, et al. Review of British National Lymphoma Investigation studies of Hodgkin’s disease and development of prognostic index. Lancet. 1985;1(8435):967–972. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91736-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stein H, Delsol G, Pileri S, et al. Classical Hodgkin lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyons, France: IARC press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Wasielewski R, Seth S, Franklin J, et al. Tissue eosinophilia correlates strongly with poor prognosis in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin’s disease, allowing for known prognostic factors. Blood. 2000;95(4):1207–1213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Wasielewski S, Franklin J, Fischer R, et al. Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin disease: new grading predicts prognosis in intermediate and advanced stages. Blood. 2003;101(10):4063–4069. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dojcinov SD, Venkataraman G, Raffeld M, et al. EBV positive mucocutaneous ulcer—a study of 26 cases associated with various sources of immunosuppression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(3):405–417. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cf8622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramasamy I, Brisco M, Morley A. Improved PCR method for detecting monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement in B cell neoplasms. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45(9):770–775. doi: 10.1136/jcp.45.9.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Dongen JJ, Langerak AW, Brüggemann M, et al. Design and standardization of PCR primers and protocols for detection of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations in suspect lymphoproliferations: report of the BIOMED-2 Concerted Action BMH4-CT98-3936. Leukemia. 2003;17(12):2257–2317. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawnicki LC, Rubocki RJ, Chan WC, et al. The distribution of gene segments in T-cell receptor gamma gene rearrangements demonstrates the need for multiple primer sets. J Mol Diagn. 2003;5(2):82–87. doi: 10.1016/s1525-1578(10)60456-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meier VS, Rufle A, Gudat F. Simultaneous evaluation of T- and B-cell clonality, t(11;14) and t(14;18), in a single reaction by a four-color multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay and automated high-resolution fragment analysis: a method for the rapid molecular diagnosis of lymphoproliferative disorders applicable to fresh frozen and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues, blood, and bone marrow aspirates. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(6):2031–2043. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63055-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables (with discussion). J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1972;34:184–220. [Google Scholar]

- 38.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:375–386. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eberle FC, Hanson JC, Killian JK, et al. Immunoguided laser assisted microdissection techniques for DNA methylation analysis of archival tissue specimens. J Mol Diagn. 2010;12(4):394–401. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamprecht B, Walter K, Kreher S, et al. Derepression of an endogenous long terminal repeat activates the CSF1R proto-oncogene in human lymphoma. Nat Med. 2010;16(5):571–579. doi: 10.1038/nm.2129. , 1 p following 579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Griesser H, Feller AC, Mak TW, et al. Clonal rearrangements of T-cell receptor and immunoglobulin genes and immunophenotypic antigen expression in different subclasses of Hodgkin’s disease. Int J Cancer. 1987;40(2):157–160. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910400205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Foss HD, Reusch R, Demel G, et al. Frequent expression of the B-cell-specific activator protein in Reed-Sternberg cells of classical Hodgkin’s disease provides further evidence for its B-cell origin. Blood. 1999;94(9):3108–3113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.García-Cosío M, Santón A, Martín P, et al. Analysis of transcription factor OCT.1, OCT.2 and BOB.1 expression using tissue arrays in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17(12):1531–1538. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cobaleda C, Jochum W, Busslinger M. Conversion of mature B cells into T cells by dedifferentiation to uncommitted progenitors. Nature. 2007;449(7161):473–477. doi: 10.1038/nature06159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tzankov AS, Went PT, Münst S, et al. Rare expression of BSAP (PAX-5) in mature T-cell lymphomas. Mod Pathol. 2007;20(6):632–637. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feldman AL, Law ME, Inwards DJ, et al. PAX5-positive T-cell anaplastic large cell lymphomas associated with extra copies of the PAX5 gene locus. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(4):593–602. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bräuninger A, Hansmann ML, Strickler JG, et al. Identification of common germinal-center B-cell precursors in two patients with both Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(16):1239–1247. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904223401604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marafioti T, Hummel M, Anagnostopoulos I, et al. Classical Hodgkin’s disease and follicular lymphoma originating from the same germinal center B cell. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(12):3804–3809. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]