Abstract

Canal stenosis is now the most common indication for lumbar spine surgery in elderly subjects. Degenerative disc disease is by far the most common cause of lumbar spinal stenosis. It is generally accepted that surgery is indicated if a well-conducted conservative management fails. A meta-analysis of the literature showed on average that 64% of surgically treated patients for lumbar spinal stenosis were reported to have good-to-excellent outcomes. In recent years, however, a growing tendency towards less invasive decompressive surgery has emerged. One such procedure, laminarthrectomy, refers to a surgical decompression involving a partial laminectomy of the vertebra above and below the stenotic level combined with a partial arthrectomy at that level. It can be performed through an approach which preserves a maximum of bony and ligamentous structures. Another principle of surgical treatment is interspinous process distraction This device is implanted between the spinous processes, thus reducing extension at the symptomatic level(s), yet allowing flexion and unrestricted axial rotation and lateral flexion. It limits the further narrowing of the canal in upright and extended position. In accordance with the current general tendency towards minimally invasive surgery, such techniques, which preserve much of the anatomy, and the biomechanical function of the lumbar spine may prove highly indicated in the surgical treatment of lumbar stenosis, especially in the elderly.

Keywords: Lumbar spinal stenosis, Surgery

Introduction

Increasing numbers of patients, particularly the elderly, are undergoing surgery for lumbar stenosis. Indeed, canal stenosis is now the most common indication for lumbar spine surgery in elderly subjects. With the aging of the population the incidence of surgical decompressions will increase [6]. Verbiest [31] introduced the concept of spinal stenosis and brought the condition to the attention of the medical world. Lumbar spinal stenosis refers to a pathological condition causing a compression of the contents of the canal, particularly the neural structures. If compression does not occur, the canal should be described as narrow but not stenotic [26]. Degenerative disc disease is by far the most common cause of lumbar spinal stenosis. A bulging degenerated intervertebral disc anteriorly, combined with thickened infolding of ligamenta flava and hypertrophy of the facet joints posteriorly result in narrowing of the spinal canal. The site of compression may be central, lateral or a combination, of the two [33]. As for many continuous characteristics, both canal size and dural sac size present a Gaussian distribution. When a canal size is too narrow for the dural sac size that it contains, stenosis occurs. An identical canal size can therefore be stenotic for one person while not being stenotic for another who happens to have a smaller dural sac size. Lumbar spinal stenosis is therefore a clinical condition and not a radiological finding or diagnosis. In addition, a poor correlation between radiological stenosis and symptoms has been reported [17].

Conservative treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis comprises physiotherapy, anti-inflammatory medications, lumbar corset, and epidural infiltration, and it is generally accepted that surgery is indicated if well-conducted conservative management fails. The aim of the operation is to improve quality of life. In recent publications from the Maine lumbar spine study Atlas et al. [3, 4] report a greater improvement in patient recorded outcomes in surgically treated patients than nonsurgically treated patients both at a 1- and at 4-year evaluation. In a prospective 10-year study Amundsen et al. [1] found considerably better treatment results in a group of patients randomized to surgical treatment that those receiving conservative treatment. A meta-analysis of the literature in 1991 showed on average that 64% of surgically treated patients for lumbar spinal stenosis were reported to have good-to-excellent outcomes [30]. It appears that the morbidity associated with surgical treatment of lumbar stenosis in the elderly is important as those patients often present with a number of preexisting endocrinological, cardiovascular, or pulmonary comorbidities [7, 20, 22]. An increased complication rate has also been shown to be associated with spinal fusion performed for lumbar stenosis in elderly patients [6]. Therefore less invasive surgical approaches are of particular interest. We describe two less invasive techniques which appear interesting in the surgical handling of spinal stenosis, particularly in the elderly.

Wide decompressive laminectomy, often combined with medial facetectomy and foraminotomy, was formerly the standard treatment. In recent years, however, a growing tendency towards less invasive decompressive surgery has emerged as a logical surgical treatment alternative, sparing anatomical structures and decreasing the risk for postoperative instability. Stenosis in the elderly is due mainly to a combination of facet hypertrophy and soft tissue buckling. It is therefore logical to limit the resection to the causative structures, thus limiting damage and instability. One such procedure, laminarthrectomy, refers to a surgical decompression involving a partial laminectomy of the vertebra above and below the stenotic level combined with a partial arthrectomy at that level. Other less invasive and destructive techniques have recently been proposed. Among these are devices inserted between the spinous processes and aiming at abolishing postural lordosis at the level of the narrowed functional unit.

Laminarthtrectomy

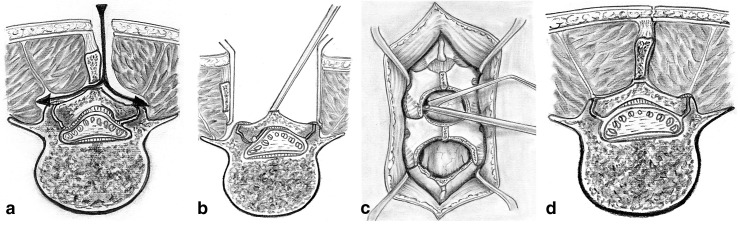

The partial laminectomy/arthrectomy or laminarthrectomy surgical procedure has been previously described in detail [9, 32]. Briefly, patients are placed in prone position with a padded support at the level of the iliac crests and sternum. A very slight flexion of hips and knees assures that the subjects lie in a lordotic position simulating the normal erect posture [14]. After a midline posterior skin and subcutaneous tissue incision the dissection goes through the dorsolumbar fascia approximately 5 mm to the left of the midline, preserving the supraspinous ligamentous attachment to the fascia. The multifidus is detached from the left side of the spinous processes and laminar attachments. An osteotomy is performed with a curved osteotome at the base of the spinous processes of the vertebrae above and below the stenotic levels, just superficially to their junction with the laminae. Flavectomies are carried out, and the superior and inferior laminae are partially resected. Partial facetectomies and foraminal decompressions are carried out under direct vision with the aid of Kerrisson rongeurs and/or a power drill. If needed, the remaining bridge of lamina is thinned. After completion of a thorough decompression the dorsolumbar fascia is resutured over a suction drain to the supraspinous ligamentous/fascial complex with the osteotomized spinous processes regaining their initial positions over the neural arches (Fig. 1). In a prospective study of 36 consecutive patients we observed a successful outcome of 58.3% at a minimum 1 year follow-up [16]. Successful surgical outcome was defined as an improvement in at least three of the following four criteria: self-reported pain on a visual analogue scale, self-reported functional status measured by low back outcome scale [12], reduction in pain during walking, and reduction in leg pain. Of the 15 patients (42%) who did not demonstrate sufficient improvement to be labeled a success 12 reported partial improvement.

Fig. 1. a.

After a midline posterior skin and subcutaneous tissue incision, the dissection goes through the dorsolumbar fascia approximately 5 mm to the left of the midline, preserving the supraspinous ligamentous attachment to the lumbar fascia. The multifidus is detached from the left side of the spinous processes and laminar attachments. An osteotomy is performed with a curved chisel at the base of the spinous processes of the vertebrae above and below the stenotic levels. b Retractors are placed to keep the wound open and are being loosened at regular intervals to avoid damage to the retracted muscles. c The ligamentum flavum is detached with a freer elevator and then completely resected on both sides. The lower third of the upper laminae and the upper third of the lower laminae are resected using Kerrison rongeurs of varying widths and lengths. A plastic suction device, held in one hand, is also used as a retractor. With the other hand, the Kerrison rongeurs are used to remove the hypertrophic anterior portion of the facet joints and the overlying capsular tissues. The same instruments are used to partially undermine the roofs in the laminae while respecting the integrity of the laminae. The facet and lamina roof decompressions create a portal by which the neural foramina can be decompressed by means of an extralong (30-cm) Kerrison rongeur. The adequacy of decompression is checked with foraminal probes. d After removal of the retractors the supraspinous ligamentous/fascial complex with the osteotomized spinous processes regain their initial positions by resting on the remainder of the neural arches. Both the lumbar fascia and the subcutaneous tissue and skin are closed in a standard fashion. (With permission from [15])

Interspinous process distraction

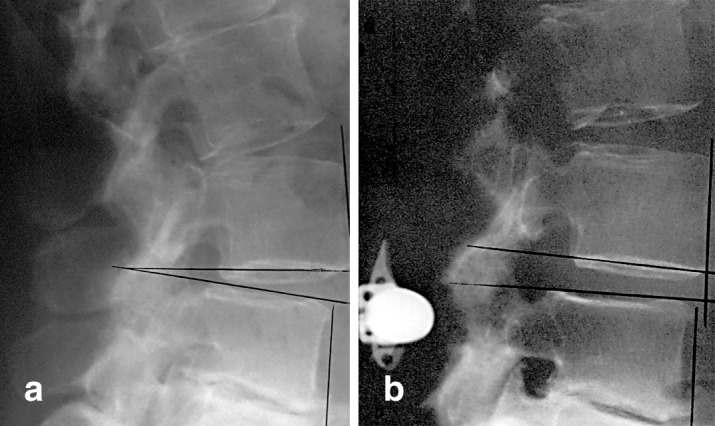

One device aimed at obtaining an interspinous process distraction is the X-Stop (St. Francis Medical Technologies, San Francisco, Calif., USA) and is currently undergoing a prospective study for possible United States Food and Drug Administration approval. Biomechanical studies have shown an unloading of the disc at the instrumented level with no effect at adjacent levels [28]. This device is implanted between the spinous processes thus reducing extension at the symptomatic level(s) bt allows flexion and unrestricted axial rotation and lateral flexion (Fig. 2). The major portion of the interspinous ligament is preserved. It is indicated in patients in whom the symptoms are increased in extension. In a prospective, randomized, multicenter study Zuckerman et al. [35] showed a success rate at 1 year of 59% with X-Stop compared to 12% in the conservative treatment control group.

Fig. 2. a.

Preoperative standing upright lateral radiographic view of a degenerative spine. b Postoperative standing upright view with the X-Stop placed between the spinous processes. Note the enlarging of the foramen

Discussion

Surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis is generally accepted when conservative treatment has failed and aims at improving quality of life by reducing symptoms such as neurogenic claudication, restless legs, and radiating neurogenic pain. Surgery does not reduce low back pain, although most patients with lumbar spinal stenosis complain from low back pain [23]. Some recent publications have indicated that advanced age does not increase the morbidity, nor does it decrease patient satisfaction or lengthen return to activities [10, 27]. Other studies [6, 7] mention an increased mortality and complication rate with age and comorbidity. Postoperative complications increase with greater use of resources, particularly when arthrodesis is being performed [6]. In the light of the rapid increase in surgery rates in some areas these contradictions indicate the need for more information concerning the relative efficacy of surgical and nonsurgical treatments for spinal stenosis [6]. In a study on gender differences Katz et al. [21] found that women had a much worse functional status than men prior to laminectomy for spinal stenosis. However, women had a comparable or greater functional improvement following surgery.

The use of wide decompressive procedures for spinal stenosis, without regard for the integrity of the laminae and facet joints and without preservation of the spinous processes and interspinous ligaments, may lead to mechanical failure of the spine and chronic pain syndrome. Hence wide decompressive procedures are often combined with fusion. A number of recent studies have reported less aggressive surgical techniques that provide for adequate decompression [2, 5, 8, 19, 24, 25, 29, 34]. These procedures have been described as fenestration, laminotomy, selective decompression, and laminarthrectomy and are purported to improve postoperative morbidity, provide early mobility, and reduce hospital stay. Conservative surgical decompression allows spinal stability to be maintained since tissue disruption is minimized, and the decompression is carried out without violating the integrity of the laminae, facet joints, and interspinous ligaments. These considerations are particularly pertinent for elderly patients.

The need to achieve an adequate level of surgical decompression to obtain good results is important. However, Herno et al. [18] found that patient satisfaction with the results of surgery is more important to a good surgical outcome than the degree of decompression determined by visually examining computed tomography scans. Comparison of pre- and postoperative scans or scans obtained on more than one occasion is complicated by a number of factors, however, including precise registration of the postoperative scans relative to the preoperative scans [13]. Greenough and Fraser [11] reported that the overall variation in vertebral morphology measurements was 2.8% in patients scanned on more than one occasion. We did find, however, that in the conservative laminarthrectomy technique the interfacet bony canal diameter was significantly increased postoperatively, and that the preoperative bony canal dimension was an important predictor of surgical outcome [15].

The interspinous process distraction device is little invasive, and the preliminary clinical results appear very satisfactory in those patients in whom symptoms are enhanced by extension. The operation is short and easy to perform and can even be carried out in lateral decubitus. For some elderly patients with important comorbidities this may be an additional advantage. The success rate obtained with these methods (58% with laminarthrectomy and 59% with the interspinous process distraction device) is similar to that generally reported for decompressive surgery [30]. If longer-term studies confirm these outcomes, in accordance with the current general tendency towards minimally invasive surgery such techniques which preserve much of the anatomy and the biomechanical function of the lumbar spine, may prove highly indicated in the surgical treatment of lumbar stenosis, especially in the elderly.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. René Louis for preparation of the surgical drawings.

References

- 1.Amundsen Spine. 2000;25:1424. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200006010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aryanpur Neurosurgery. 1990;26:429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atlas Spine. 1996;21:1787. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199608010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atlas Spine. 2000;25:556. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caspar Acta. 1994;Neurochir:130. doi: 10.1007/BF01401463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciol J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:285. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deyo J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;4:536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:116. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199804000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser Eur Spine J. 1992;1:249. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fredman Eur Spine J. 2002;11:571. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenough Eur Spine J. 1992;1:32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenough Spine. 1992;17:36. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunzburg J Spinal Disord. 1989;2:170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunzburg R, Szpalski M, Hayez J-P (1996) The surgical approach to the lumbar spine. In: Szpalski M, Gunzburg R, Spengler D, Nachemson A (eds) Instrumented fusion of the lumbar spine: state of the art, questions and controversies. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, pp 17–24

- 15.Gunzburg R, Keller TS, Szpalski M et al (2003) A prospective study on CT scan outcomes after conservative decompression surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis. J Spinal Disord Techn 16:261–267:2003 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Gunzburg Eur Spine J. 2003;12:197. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0479-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herno Spine. 1994;19:1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herno Spine. 1999;24:1010. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199905150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herron J Spinal Disord. 1991;4:26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:687. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz, Spine. 1995;20:1155. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199505150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz Spine. 1996;21:92. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199601010-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin Neurosurgery. 1982;11:546. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munting E, Druez V, Tsoukas D (2000) Surgical decompression of lumbar spinal stenosis according to Senegas technique. In: Gunzburg R, Szpalski M (eds) Lumbar spinal stenosis. Lippincott-Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 207–214

- 26.Postacchini J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ragab Spine. 2003;28:348. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200302150-00007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swanson Spine. 2003;28:26. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200301010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner Spine. 1992;17:1. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199201000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verbiest J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1954;26:230. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.36B2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiner Spine. 1999;24:62. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong J West Pac Orthop Assoc. 1992;29:37. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young Neurosurgery. 1988;23:628. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198811000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zucherman JF, Hsu KY, Hartjen CA et al (2003) A prospective randomized multi-center study for the treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis with the X-STOP interspinous spacer: 1-year results. Eur Spine J (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]