Abstract

We have evaluated the in vitro activity of voriconazole against 61 strains of Aspergillus fumigatus by using broth microdilution, disk diffusion, and minimal fungicidal concentration procedures. We observed an excellent correlation between the results obtained with the three methods. Five percent of the strains showed MICs greater than or equal to the epidemiological cutoff value (ECV; 1 μg/ml). To assess whether MICs were predictive of in vivo outcome, we tested the efficacy of voriconazole at 25 mg/kg of body weight daily in an immunosuppressed murine model of disseminated infection using 10 strains representing various patterns of susceptibility to the drug as determined by the in vitro study. Voriconazole prolonged survival and reduced fungal load in the kidneys and brain in those mice infected with strains with MICs of ≤0.25 μg/ml, while in mice infected with strains with MICs of 0.5 to 2 μg/ml, the efficacy was varied and strain dependent and in mice infected with the strain with a MIC of 4 μg/ml, the antifungal did not show efficacy. Voriconazole reduced galactomannan antigenemia against practically all strains with a MIC of <4 μg/ml. Our results demonstrate that some relationship exists between voriconazole MICs and in vivo efficacy; however, further studies testing additional strains are needed to better ascertain which MIC values can predict clinical outcome.

INTRODUCTION

Invasive aspergillosis is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the immunocompromised host, Aspergillus fumigatus being the leading cause of invasive aspergillosis worldwide (1). At present, voriconazole is the first choice in the treatment of such infections (2), and although A. fumigatus is generally susceptible to voriconazole, several studies have demonstrated an increasing number of azole-resistant isolates (3–5). This represents an important problem in the clinical management of invasive aspergillosis because therapeutic options are limited.

The development of clinical breakpoints of the most usual antifungal drugs might be useful for predicting the outcomes of fungal infections. However, the available antifungal susceptibility data are only based on in vitro and animal studies (6). A recent important step has been the proposal of epidemiological cutoff values (ECVs) for voriconazole against several Aspergillus spp., including A. fumigatus (ECV = 1 μg/ml), and theoretically, those isolates showing MICs higher than the ECV will show resistance (7, 8).

We have evaluated the efficacy of voriconazole at 25 mg/kg of body weight (9) in a murine model of disseminated infection by A. fumigatus, testing isolates with different MICs in order to ascertain the role of the in vitro data as a predictor of infection outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sixty-one clinical strains of Aspergillus fumigatus were tested in the in vitro studies. Their susceptibility to voriconazole was evaluated using a broth microdilution method, carried out according to the CLSI guidelines for filamentous fungi (10), and a disk diffusion method that uses nonsupplemented Mueller-Hinton agar and 6-mm-diameter paper disks containing 1 μg of voriconazole (11). The strain A. fumigatus ATCC MYA-3626 was used as the quality control. The MICs (μg/ml) and inhibition zone diameters (IZDs) (mm) were read at 48 and 24 h, respectively. The suggested ECVs of voriconazole for A. fumigatus are 1 μg/ml and ≥17 mm for microdilution and disk diffusion methods, respectively (7, 11). The minimal fungicidal concentration (MFC) was determined by subculturing 20 μl from each well that showed complete inhibition or an optically clear well relative to the last positive well and the growth control onto potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates. The plates were incubated at 35°C until growth was observed in the control subculture. The MFC was the lowest drug concentration at which approximately 99.9% of the original inoculum was killed (12).

For in vivo studies, 10 isolates with different in vitro susceptibilities were chosen (Table 1). Male OF1 mice (Charles River, Criffa S.A., Barcelona, Spain) weighing 30 g were used. Animals were housed under standard conditions. All animal care procedures were supervised and approved by the Universitat Rovira i Virgili Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee. Animals were immunosuppressed 1 day prior to infection by administering a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 200 mg/kg of cyclophosphamide (Genoxal; Laboratories Funk S.A., Barcelona, Spain), plus a single intravenous (i.v.) injection of 150 mg/kg of body weight of 5-fluorouracil (Fluorouracilo; Ferrer Farma S.A., Barcelona, Spain). Previous studies with this immunosuppressive regimen demonstrated that the peripheral blood polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) counts were <100/μl from day 3 to 9 or later (13). Mice were challenged with 2 × 103 CFU in 0.2 ml of sterile saline, injected via the lateral tail vein. Preliminary experiments demonstrated that this inoculum was appropriate for producing an acute infection, with 100% of the animals dying within 11 days (data not shown).

Table 1.

Mean survival times of mice infected with different strains of A. fumigatus

| Infecting straina (MIC [μg/ml]) | Mean (range) survival time (days) |

|

|---|---|---|

| VRC 25 mg/kgb | Control | |

| FMR 10220 (0.12) | 21.5 (7–30) abc | 7.1 (6–9) |

| FMR 10536 (0.25) | 21.8 (7–30) abc | 5.9 (5–7) |

| FMR 10513 (0.25) | 17.5 (6–30) ab | 6.9 (6–9) |

| FMR 10528 (0.5) | 9.1 (6–17) | 5.5 (5–7) |

| FMR 10505 (0.5) | 13 (5–30) a | 7.1 (5–12) |

| FMR 7738 (1) | 14.2 (6–30) a | 7.1 (5–15) |

| FMR 10512 (1) | 11.4 (6–30) | 8.2 (6–12) |

| UTHSC 10-3338 (2) | 20.3 (13–30) ab | 5.6 (5–6) |

| UTHSC 10-246 (2) | 17.4 (5–30) ab | 6.6 (5–12) |

| UTHSC 10-448 (4) | 9.3 (6–30) | 7.3 (6–14) |

FMR, Facultat de Medicina i Ciencies de la Salut, Reus, Spain; UTHSC, Fungus Testing Laboratory, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX.

a, P < 0.05 versus control; b, P < 0.05 versus FMR 10528; c, P < 0.05 versus UTHSC 10-448.

Voriconazole (Vfend; Pfizer S.A., Madrid, Spain) was administered at 25 mg/kg of body weight/dose once a day orally by gavage. We selected that dose based on a previous pharmacokinetic study in which this dose resulted in therapeutic serum concentrations against Aspergillus flavus in mice (9). On the other hand, although the authors did not measure serum concentration of voriconazole, lower doses, such as 10 mg/kg, were less effective in prolonging survival and reducing fungal load. In agreement with Warn et al. (9) we have obtained voriconazole serum concentrations higher than the corresponding MICs for all strains tested. In addition, this dosage does not exceed any doses usually used in similar mouse experiments. Previous in vivo studies testing other fungi have used considerably higher doses of voriconazole, such as 40, 60, and 80 mg/kg/day with good efficacy (14–16).

Due the rapid clearance of voriconazole observed in mice, from 3 days before infection, the animals that received this drug were given grapefruit juice instead of water on the basis of previous studies that demonstrated that grapefruit increases the voriconazole concentration in murine serum (17, 18). To prevent bacterial infection, all animals received ceftazidime at 5 mg/kg subcutaneously once daily. The efficacy of voriconazole was evaluated by prolongation of survival of mice in comparison to the survival of controls, by tissue burden reduction, and by determination of galactomannan serum levels by enzyme immunoassay. Treatments began 1 day after infection and lasted for 7 days. For survival studies, groups of 8 mice were randomly established for each strain and each treatment and checked daily for 30 days after challenge. Controls received no treatment. For tissue burden studies, groups of 8 mice were also established, and the animals were sacrificed on day 5 postinfection in order to compare the results with the control results. Kidneys and brain were aseptically removed, weighed, and homogenized in 1 ml of sterile saline. In previous murine studies, these were the main target organs (19, 20). Serial 10-fold dilutions of the homogenates were plated on PDA and incubated for 48 h at 35°C. The numbers of CFU per gram of tissue were calculated. Additionally, before mice were sacrificed, approximately 1 ml of blood from each mouse belonging to the tissue burden groups was extracted by cardiac puncture. Pooled serum samples from mice of each treatment group were used to determine the drug concentration in serum by bioassay 4 h after drug administration (15, 16), and the galactomannan levels were determined by enzyme immunoassay (Platelia Aspergillus; Bio-Rad, Marmes, la Coquette, France) as a marker of the treatment response (21). Values were expressed as a galactomannan index (GMI), defined as the optical density of a sample divided by the optical density of a threshold serum provided in the test kit.

For survival studies, the Kaplan-Meier method and log rank test were used. Differences were considered statically significant at a P value of <0.05. When multiple comparisons were carried out, the t test with Welch's correction and Bonferroni correction was used to avoid an increase in type I error. The tissue burden studies were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was carried out to determine the normal distribution of galactomannan serum levels and bioassay data so that they could be analyzed using the t test.

RESULTS

The voriconazole MICs of the 61 A. fumigatus strains tested were in the range from 0.12 to 4 μg/ml, with a modal MIC of 0.5 μg/ml and MIC50 and MIC90 values of 0.5 and 1 μg/ml, respectively (data not shown). The IZD range was 0 to 34 mm (geometric mean ± standard deviation, 26.85 ± 4.1 mm). The MFC ranged from 0.25 to 8 μg/ml (geometric mean = 0.77 μg/ml). Following the suggested ECV against Aspergillus fumigatus (7), most of the strains tested showed voriconazole MICs equal to or less than ECV and IZDs equal to or greater than ECV, i.e., 95 and 93%, respectively. In general, high correlations between the results obtained with the microdilution and the disk diffusion methods were observed. The differences between MICs and MFCs were never >2 dilutions (data not shown).

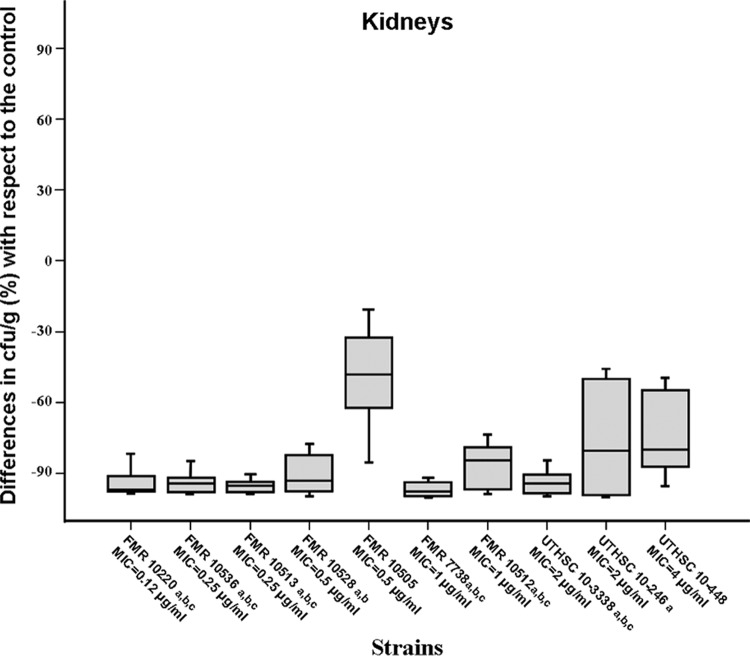

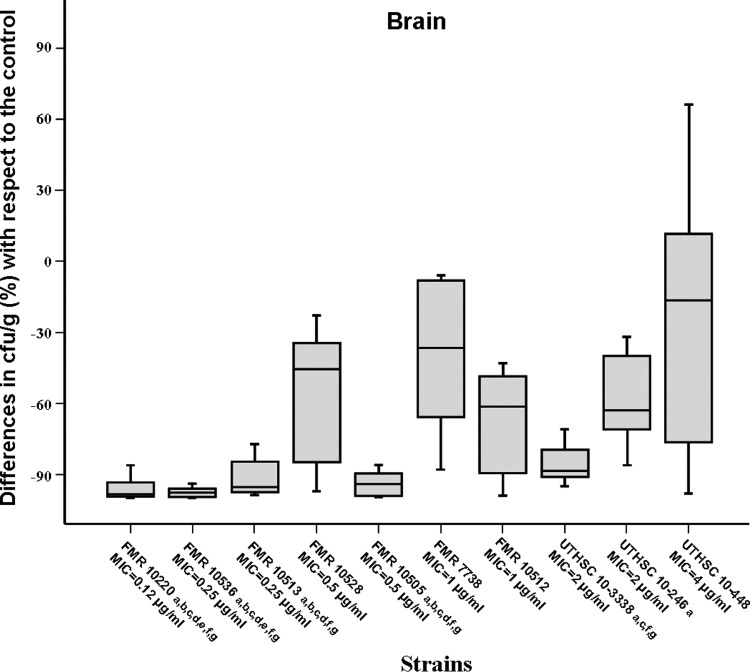

Voriconazole significantly prolonged survival and reduced fungal load in kidneys and brain with respect to the results for the control group in those animals infected with isolates having MICs of ≤0.25 μg/ml. In mice challenged with strains with MICs from 0.5 to 2 μg/ml, the results were varied, and in those infected with the only strain with a MIC of 4 μg/ml, the drug did not show efficacy. (Table 1 and Fig. 1 and 2). Significant differences in survival were observed when the results obtained with strains with MICs of <0.5 μg/ml were compared with those for strains with MICs from 0.5 to 4 μg/ml (P < 0.02).

Fig 1.

Box plot of changes in fungal loads of mice infected with 2 × 103 CFU of A. fumigatus with respect to the fungal load in the respective control in kidneys of mice treated with voriconazole at 25 mg/kg orally once a day. a, P < 0.05 versus control; b, P < 0.05 versus FMR 10505; c, P < 0.05 versus UTHSC 10-448. Horizontal bars represent median values of eight mice. Error bars indicated standard errors of the medians.

Fig 2.

Box plot of changes in fungal load of mice infected with 2 × 103 CFU of A. fumigatus with respect to the fungal load in the respective control in brain of mice treated with voriconazole at 25 mg/kg orally once a day. a, P < 0.05 versus control; b, P < 0.05 versus FMR 10528; c, P < 0.05 versus FMR 7738; d, P < 0.05 versus FMR 10512; e, P < 0.05 versus UTHSC 10-3338; f, P < 0.05 versus UTHSC 10-246; g, P < 0.05 versus UTHSC 10-448. Horizontal bars represent median values of eight mice. Error bars indicate standard errors of the medians.

At day 5 of the experiment, the serum concentration of voriconazole was 8.09 ± 3.05 μg/ml. The galactomannan concentration in serum at day 5 of the experiment was significantly lower (P < 0.05) in animals treated with voriconazole than in control animals, with the exception of mice challenged with one strain for which the MIC was 0.5 μg/ml and those infected with the strain with a voriconazole MIC of 4 μg/ml (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have selected several A. fumigatus strains with different in vitro susceptibilities to voriconazole in order to assess whether there is any relationship between the in vitro activity and its in vivo efficacy. Only 5% of the 61 isolates tested showed MICs of more than the ECV. In previous similar studies, the values were between 1.4 and 4.1% (1, 7, 22). We observed an excellent correlation between the in vitro results obtained with microdilution, disk diffusion, and MFC. In agreement with other authors, our in vitro results suggest that the disk diffusion method could be a good option for determining voriconazole susceptibility (23, 24), due to its simplicity, low cost, and high reproducibility. Our MFC data (MFC/MIC ≤ 2) confirmed the fungicidal activity of this drug against A. fumigatus (25, 26).

Mavridou et al. (15) demonstrated a good efficacy of voriconazole at 40 mg/kg in prolonging the survival of nonimmunosuppressed mice infected with three A. fumigatus isolates with voriconazole MICs from 0.12 to 0.25 μg/ml, but this dosage was ineffective in mice infected with a strain with a MIC of 2 μg/ml. In our study, voriconazole also showed efficacy in those animals infected with A. fumigatus isolates having MICs of ≤0.25 μg/ml, but in those with MICs of >0.25 μg/ml, its efficacy was varied and strain dependent. Nevertheless, it should be noted that our study differs from that of Mavridou et al. (15) in many important aspects, such as the voriconazole dosage, the immune status of animals, and the endpoints used to evaluate the in vivo efficacy of the treatment, which makes any comparison difficult. In the present study, only one dose of voriconazole was evaluated because the use of an additional dose for the same strains would have required more than 40 groups of animals. The dose tested demonstrated efficacy as seen in previous similar studies (9, 27), and using this dose, the serum levels of that drug were always greater than the MICs for the strains tested. A possible limitation of the present study is the use of a systemic infection model, which is not the most common clinical presentation of A. fumigatus infection. However, systemic infections are not uncommon, especially in immunocompromised patients, and are often fatal (28, 29). Another potential weakness could be the use of mice to evaluate voriconazole efficacy, bearing in mind that the metabolism and clearance of the drug is very rapid in the mouse. However, the use of grapefruit juice to increase voriconazole serum concentration demonstrated the effectiveness of its oral administration in several experimental murine mycoses (17, 18). In contrast, one of the most important aspects of this study was the large number of strains used which, although important, is atypical in this type of study (6). It is also well known, as has been demonstrated in this study, that different isolates of a given species frequently show a different response to the same antifungal agent. Therefore, the use of only one strain to infer antifungal susceptibility of a species can produce erroneous results.

Our results demonstrate that A. fumigatus strains showed important variability in their in vivo responses to voriconazole, particularly for those isolates with MIC values of ≥0.25 μg/ml, and there was no clear relationship between increasing MIC and in vivo response to voriconazole. These results agree with those of Baddley et al. (30), who investigated the relationship between the in vitro susceptibility of 115 A. fumigatus isolates recovered from patients with invasive aspergillosis who received voriconazole and the clinical outcome. They observed that MICs of ≥ECV were not statistically associated with increased mortality.

Although several clinical studies have shown that voriconazole serum concentrations of ≤1 μg/ml have been generally associated with therapeutic failure (31, 32), in the present study, we did not observe this relationship, because voriconazole showed low efficacy against different isolates of A. fumigatus, although all drug serum levels were ≥4 μg/ml.

Taking into account all the parameters of treatment response used in this study, our results revealed that only a MIC of 4 μg/ml was associated with treatment failure; however, only one such strain was evaluated, so it is not possible to draw conclusions about these results. Nevertheless, only 0.9% of A. fumigatus strains showed voriconazole MICs of ≥4 μg/ml (7).

In summary, using this MIC model, voriconazole significantly prolonged survival and reduced fungal load in kidneys and brain with respect to the results for the control group in those animals infected with isolates having MICs of ≤0.25 μg/ml. In those mice challenged with strains with MICs from 0.5 to 4 μg/ml, the results were varied and poorly predictive of in vivo response.

Further studies testing additional strains with various voriconazole MICs are necessary to more accurately define the clinical significance of in vitro data.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Minematsu A, Hirano K, Iwanaga N, Ide S, Mihara T, Hosogaya N, Takazono T, Morinaga Y, Nakamura S, Kurihara S, Imamura Y, Miyazaki T, Nishino T, Tsukamoto M, Kakeya H, Yamamoto Y, Yanagihara K, Yasuoka A, Tashiro T, Kohno S. 2012. Antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates obtained in Nagasaki, Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:584–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walsh TJ, Anaissie E, Denning DW, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis D, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Segal BH, Steinbach WJ, Stevens DA, JA van Burik Wingard JR, Patterson TF. 2008. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:327–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Howard SJ, Cerar D, Anderson J, Albarrag A, Fisher MC, Pasqualotto AC, Laverdiere M, Arendrup MC, Perlin DS, Denning DW. 2009. Frequency and evolution of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus associated with treatment failure. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:1068–1676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pfaller MA. 2012. Antifungal drug resistance: mechanisms, epidemiology, and consequences for treatment. Am. J. Med. 125:3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Verweij PE, Howard SJ, Melchers WJ, Denning DW. 2009. Azole-resistance in Aspergillus: proposed nomenclature and breakpoints. Drug Resist. Updat. 12:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guarro J. 2011. Lessons from animal studies for the treatment of invasive human infections due to uncommon fungi. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66: 1447:1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Espinel-Ingroff A, Diekema DJ, Fothergill A, Johnson E, Pelaez T, Pfaller MA, Rinaldi MG, Cantón E, Turnidge J. 2010. Wild-type MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for the triazoles and six Aspergillus spp. for the CLSI broth microdilution method (M38-A2 document). J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:3251–3257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, Rex JH, Alexander BD, Andes D, Brown SD, Chaturvedi V, Espinell-Ingroff A, Fowler CL, Johnson EM, Knapp CC, Motyl MR, Ostroski-Zeichner L, Sheehan DJ, Walsh TJ, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Antifungal Testing Subcommittee 2009. Wild type distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute broth microdilution methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3142–3146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Warn PA, Sharp A, Mosquera J, Spickermann J, Schmitt-Hoffmann A, Heep M, Denning DW. 2006. Comparative in vivo activity of BAL 4815, the active component of the prodrug BAL8557, in a neutropenic murine model of disseminated Aspergillus flavus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:1198–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. Approved standard, 2nd ed Document M38-A2 CLSI, Wayne, Pa [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2010. Method for antifungal disk diffusion susceptibility testing of nondermatophyte filamentous fungi. Approved guideline. Document M51-A CLSI, Wayne, Pa [Google Scholar]

- 12. Espinell-Ingroff A, Chaturvedi V, Fothergill A, Rinaldi MG. 2002. Optimal testing conditions for determining MICs and minimum fungicidal concentration of new and established antifungal agents for uncommon moulds: NCCLS collaborative study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3776–3781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ortoneda M, Capilla J, Pastor FJ, Serena C, Guarro J. 2004. Interaction of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and high doses of liposomal amphotericin B in the treatment of systemic murine scedosporiosis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 50:247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Majithiya J, Sharp A, Parmar A, Denning DW, Warn PA. 2009. Efficacy of isavuconazole, voriconazole and fluconazole in temporally neutropenic murine model of disseminated Candida tropicalis and Candida krusei. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 63:161–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mavridou E, Bruggemann RJ, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE, Mouton JW. 2010. Impact of cyp 51A mutations on the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of voriconazole in a murine model of disseminated aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4758–4764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rodríguez MM, Calvo E, Serena C, Mariné M, Pastor FJ, Guarro J. 2009. Effects of double and triple combinations of antifungal drugs in a murine model of disseminated infection by Scedosporium prolificans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2153–2155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graybill JR, Najvar LK, Gonzalez GM, Hernandez S, Bocanegra R. 2003. Improving the mouse model for studying efficacy of voriconazole. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:1373–1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sugar AM, Liu XP. 2000. Effect of grapefruit juice on serum voriconazole concentration in the mouse. Med. Mycol. 38:209–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Luque JC, Clemons KV, Stevens DA. 2003. Efficacy of micafungin alone or in combination against systemic murine aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1452–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clemons KV, Grunig G, Sobel RA, Mirels LF, Rennick DM, Stevens DA. 2000. Role of IL-10 in invasive aspergillosis: increased resistance of IL-10 gene knockout mice to lethal systemic aspergillosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 122:186–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sionov E, Mendlovic S, Segal E. 2005. Experimental systemic murine aspergillosis: treatment with polyene and caspofungin combination and G-CSF. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:594–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pfaller MA, Boyken R, Hollis J, Kroeger J, Messer S, Tendolkar S, Diekema D. 2011. Use of epidemiological cutoff values to examine 9-year trends in susceptibility of Aspergillus species to triazoles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:586–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Espinel-Ingroff A, Cantón E. 2008. Comparison of Neo-sensitabs tablet diffusion assay with CLSI broth microdilution M38-A and disk diffusion methods for testing susceptibility of filamentous fungi with amphotericin B, caspofungin, itraconazole, posaconazole, and voriconazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1793–1803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Serrano MC, Ramírez M, Morilla D, Valverde A, Chávez M, Espinel-Ingroff A, Claro R, Fernández A, Almeida C, Martín-Mazuelos E. 2004. A comparative study of the disk diffusion method with the broth microdilution and Etest methods for voriconazole susceptibility testing of Aspergillus spp. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 53:739–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krishnan S, Manavathu EK, Chandrasekar PH. 2005. A comparative study of fungicidal activities of voriconazole and amphotericin B against hyphae of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:914–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lass-Flörl C, Perkhofer S. 2008. In vitro susceptibility-testing in Aspergillus species. Mycoses 51:437–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Calvo E, Pastor FJ, Salas V, Mayayo E, Guarro J. 2012. Combined therapy of voriconazole and anidulafungin in murine infections by Aspergillus flavus. Mycopathologia 173:251–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Behnsen J, Hartmann A, Schmaler J, Gehrke A, Brakhage AA, Zipfel PF. 2008. Host complement system fungus Aspergillus fumigatus evades the host complement system. Infect. Immun. 76:820–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brakhage AA. 2006. Systemic fungal infections caused by Aspergillus species: epidemiology, infection process and virulence determinants. Curr. Drug Targets 6:875–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baddley JW, Marr KA, Andes DR, Walsh TJ, Kauffman CA, Kontoyiannis DP, Ito JI, Balajee SA, Pappas PG, Moser SA. 2009. Patterns of susceptibility of Aspergillus isolates recovered from patients enrolled in the transplant associates infection surveillance network. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3271–3275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Andes D, Pascual A, Marchetti O. 2009. Antifungal therapeutic drug monitoring: established and emerging indications. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:24–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith J, Andes D. 2008. Therapeutic drug monitoring of antifungals: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations. Ther. Drug Monit. 30:167–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]