Abstract

Limited antimicrobial agents are available for the treatment of implant-associated infections caused by fluoroquinolone-resistant Gram-negative bacilli. We compared the activities of fosfomycin, tigecycline, colistin, and gentamicin (alone and in combination) against a CTX-M15-producing strain of Escherichia coli (Bj HDE-1) in vitro and in a foreign-body infection model. The MIC and the minimal bactericidal concentration in logarithmic phase (MBClog) and stationary phase (MBCstat) were 0.12, 0.12, and 8 μg/ml for fosfomycin, 0.25, 32, and 32 μg/ml for tigecycline, 0.25, 0.5, and 2 μg/ml for colistin, and 2, 8, and 16 μg/ml for gentamicin, respectively. In time-kill studies, colistin showed concentration-dependent activity, but regrowth occurred after 24 h. Fosfomycin demonstrated rapid bactericidal activity at the MIC, and no regrowth occurred. Synergistic activity between fosfomycin and colistin in vitro was observed, with no detectable bacterial counts after 6 h. In animal studies, fosfomycin reduced planktonic counts by 4 log10 CFU/ml, whereas in combination with colistin, tigecycline, or gentamicin, it reduced counts by >6 log10 CFU/ml. Fosfomycin was the only single agent which was able to eradicate E. coli biofilms (cure rate, 17% of implanted, infected cages). In combination, colistin plus tigecycline (50%) and fosfomycin plus gentamicin (42%) cured significantly more infected cages than colistin plus gentamicin (33%) or fosfomycin plus tigecycline (25%) (P < 0.05). The combination of fosfomycin plus colistin showed the highest cure rate (67%), which was significantly better than that of fosfomycin alone (P < 0.05). In conclusion, the combination of fosfomycin plus colistin is a promising treatment option for implant-associated infections caused by fluoroquinolone-resistant Gram-negative bacilli.

INTRODUCTION

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a rare but difficult-to-treat complication which requires combined surgical and antimicrobial treatment and is associated with significant morbidity and health care costs (1–3). Staphylococci cause more than half of all PJIs (4), but Gram-negative rods are implicated in 6 to 23% (5–7). While rifampin-containing regimens showed high cure rates in staphylococcal PJIs (2), fluoroquinolones demonstrated good activity against PJI caused by Gram-negative rods (8). Besides a favorable pharmacokinetic profile, fluoroquinolones have excellent activity against Gram-negative biofilms (9, 10).

Escherichia coli is one of the predominant organisms among Gram-negative bacilli causing PJI (6, 7, 11, 12). In this organism, the emergence of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing strains harboring the plasmid-acquired gene for CTX-M15 β-lactamase is of particular concern (13, 14). In ESBL-producing strains, the resistance to beta-lactams (except carbapenems) is frequently associated with resistance to other antibiotics, including fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and cotrimoxazole. In the absence of new antimicrobial agents (15), “old” antibiotics have been reconsidered and evaluated in multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli, including fosfomycin and colistin (16–18).

Fosfomycin has a broad activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and has mainly been used for treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections, with good efficacy and tolerability (19, 20). High concentrations of fosfomycin were reported in bone in patients with diabetic foot osteomyelitis, likely due to its structural similarity to hydroxyapatite (21). For treatment of endocarditis, fosfomycin showed synergistic activity with high-dose daptomycin against Staphylococcus aureus (22). Tigecycline, the first glycylcycline in clinical use, has an expanded broad-spectrum activity, including activity against resistant Gram-negative bacilli, when combined with other antimicrobials (23). Colistin has been increasingly used in the last decade because of the emergence of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli in the past years, especially in combination with other drugs (17, 24).

In this study, we investigated the activity of fosfomycin, tigecycline, colistin, and gentamicin, alone and in combination, against a well-characterized ESBL-producing clinical strain of E. coli in vitro and in a foreign-body infection model (25–28). This animal model has been previously used for studying the activity of antimicrobial combinations against implant-associated infections (26, 29).

(Part of the results of this study were presented at the Annual Meeting of the European Bone and Joint Infection Society [EBJIS] on September 15 to 17, 2011, in Copenhagen, Denmark, and at the 51th Interscience Conference of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy [ICAAC] on September 17 to 20, 2011, in Chicago, IL.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Test strain.

E. coli Bj HDE-1 (13), an ESBL-producing clinical strain that is resistant to ciprofloxacin, was used for in vitro and animal experiments. As control strain for susceptibility testing, the ciprofloxacin-susceptible E. coli strain ATCC 25922 was used. Strains were stored at −70°C by using a cryovial bead preservation system (Microbank; Pro-Lab Diagnostics, Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada). One cryovial bead was cultured overnight on Columbia sheep blood agar plates (Becton, Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). Inocula were prepared from subcultures of one colony, resuspended in 5 ml of Trypticase soy broth (TSB), and incubated overnight at 37°C without shaking.

Antimicrobial agents.

Fosfomycin was provided as purified powder by the manufacturer (InfectoPharm, Heppenheim, Germany), tigecycline by Pfizer (Pfizer, Zurich, Switzerland), colistin by Sanofi-Aventis (Paris, France), and gentamicin by Essex Chemie (Lucerne, Switzerland). Stock solutions of appropriate concentrations were prepared in sterile pyrogen-free water.

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

The susceptibility of E. coli to fosfomycin, tigecycline, colistin, and gentamicin was determined in triplicate by using a standard inoculum of 5 × 105 CFU/ml adjusted from overnight cultures. The MIC was determined in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) by the macrodilution method, according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (30). In brief, 10 2-fold serial dilutions of each antimicrobial agent were prepared in 2 ml MHB in plastic tubes. Tubes were inoculated below the meniscus and incubated for 18 h at 37°C without shaking. After the determination of MIC (defined as the lowest antimicrobial concentration inhibiting visible growth), tubes without visible growth were vigorously vortexed and incubated for an additional 4 h at 37°C without shaking. Aliquots of 100 μl were plated on blood agar plates, and the number of viable bacteria was determined. The minimum bactericidal concentration during logarithmic growth (MBClog) was defined as the lowest antimicrobial concentration which killed ≥99.9% of the initial bacterial count (i.e., ≥3 log10 CFU/ml) (31). The minimum bactericidal concentration during stationary growth phase (MBCstat) was determined in nutrient-restricted medium consisting of 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4), as previously described (27). In this medium, counts of E. coli remained within ±10% of the initial inoculum for >36 h.

Time-kill studies.

The activities of fosfomycin, tigecycline, colistin, and gentamicin (alone and in combination) were evaluated by time-kill studies using an inoculum of ∼1 × 106 CFU/ml of E. coli. In time-kill studies, a higher inoculum was used than in antimicrobial susceptibility tests in order to investigate the synergistic and antagonistic effects of drug combinations. Antibiotic dilutions were prepared in 10 ml of MHB adjusted to final concentrations of 0.5, 1, and 4× the MIC of the test strain. MHB without antibiotics served as a growth control; MHB without E. coli served as a negative control. The CFU were enumerated after 0, 2, 4, 6, and 24 h of incubation at 37°C by plating aliquots of appropriate dilutions on Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA). Antibiotic dilutions of ≥10-fold were used to assess numbers in the range of 10 to 250 CFU per plate and to minimize the antimicrobial carryover effect. The quantification limit was set at 200 CFU/ml (i.e., 10 CFU in 50 μl at a 10-fold dilution). Killing was expressed as reduction in log10 CFU/ml (mean ± standard deviation [SD]). Synergism was defined as a >2-log10 increase in killing with the drug combination at 24 h compared to killing achieved with the more active single drug. Antagonism was defined as a >2-log10 decrease in killing with the drug combination at 24 h compared to killing achieved with the more active single drug.

Emergence of antimicrobial resistance in vitro.

The in vitro emergence of resistance was screened by plating E. coli on MHA containing fosfomycin, tigecycline, or colistin at 4× the MIC. For this purpose, several colonies of E. coli from the agar plate were suspended in normal saline, adjusted to a turbidity of McFarland 0.5 (≈1 × 108 CFU/ml), plated in 0.1-ml aliquots on MHA, and incubated for 48 h. The antimicrobial susceptibility of colonies growing on MHA was determined by Etest (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden).

Evaluation of antibiofilm activity using microcalorimetry.

Biofilm was formed on porous sintered glass beads (diameter, 4 mm; pore size, 60 μm; surface area, approximately 60 cm2). Glass beads were placed in Luria broth (LB), inoculated with 2 colonies of E. coli, and incubated at 37°C. After 3 h, 12 h, and 24 h, beads were removed from the LB, washed three times with normal saline, and incubated in 2 ml of LB containing serial dilutions of fosfomycin, tigecycline, colistin, and gentamicin, alone and in combination, at concentrations of 0.12 to 256 μg/ml. After another 24 h, beads were washed three times with normal saline and placed in microcalorimetry ampoules containing 3 ml LB to detect heat production of residual bacteria. Measurements were performed in an isothermal 48-channel batch calorimeter (thermal activity monitor, model 3102 TAM III; TA Instruments, New Castle, DE), calibrated at 37°C ± 0.00001°C with a lower limit of heat-flow detection of 0.25 μW. All experiments were performed in triplicate. The minimal heat inhibition concentration (MHIC) was defined as the lowest antimicrobial concentration inhibiting heat production with a delay of ≥24 h, as previously described (25, 32).

Animal model.

An established foreign-body infection model in guinea pigs was used, as described previously (25, 28). Male albino guinea pigs (Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany) were kept at the animal facility of our institution. Animal experiments were performed according to the Swiss veterinary law regulations. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. In this model, four sterile polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) cages (32 mm by 10 mm) perforated with 130 regularly spaced holes 1 mm in diameter (Angst-Pfister, Zurich, Switzerland) were subcutaneously implanted under aseptic conditions in the flanks of guinea pigs weighing at least 450 g. Animals were anesthetized with a subcutaneous injection of ketamine (20 mg/kg) and xylazine (4 mg/kg). Two weeks after surgery and upon complete healing of the surgical wounds, sterility of the cages was verified by culture of the aspirated cage fluid. Contaminated cages were excluded from further studies. For the treatment studies, cages were infected by percutaneous inoculation of 200 μl containing 7 × 104 CFU of E. coli (i.e., day 0). The establishment of infection was confirmed 24 h after infection by quantitative culture of aspirated cage fluid (i.e., day 1).

Antimicrobial treatment studies.

Antimicrobial treatment was initiated 24 h after infection (day 1). Three animals (each holding four cages) were randomized into each of the following treatment groups (drugs were administered alone or in combination): untreated control (sterile saline); fosfomycin (150 mg/kg), tigecycline (10 mg/kg), colistin (15 mg/kg), and gentamicin (10 mg/kg). All antimicrobial agents were administered every 12 h intraperitoneally for 4 days, i.e., a total of eight doses, as previously reported (28). The dosing regimens for all tested antimicrobials were chosen according to pharmacokinetic studies performed in mice, rats, and rabbits, mimicking concentrations achievable in humans (33–40).

Activity against planktonic bacteria.

Planktonic bacteria in the aspirated cage fluid were enumerated on day 4, just before administration of the last antimicrobial dose, and on day 10, which is 5 days after end of antimicrobial treatment. Bacterial counts were expressed as means ± SD of log10 CFU/ml. The quantification limit of planktonic bacteria was set at 1,000 CFU/ml (i.e., 10 CFU in 50 μl at a 10-fold dilution). Thus, for statistical analysis, a value of 3 log10 CFU/ml was assigned to negative cage fluid cultures. The treatment efficacy against planktonic bacteria was expressed as the reduction of CFU log10/ml in the cage fluid.

Activity against biofilm bacteria.

Animals were sacrificed on day 10, and cages were removed under aseptic conditions. Each cage was separately placed in 5 ml TSB, vortexed for 30 s, and incubated at 37°C. After 24 h, cages were vortexed for 30 s and sonicated at 40 kHz for 1 min (BactoSonic, Bandelin, Berlin, Germany) to remove potential biofilm bacteria, as previously described (41). Aliquots of 100 μl were plated on MHA (Becton, Dickinson) and assessed for bacterial growth 24 to 48 h later. The activity against biofilm bacteria was expressed as the cure rate, defined as the number of cage cultures without E. coli growth divided by the total number of cages in the treatment group.

Emergence of antimicrobial resistance in vivo.

E. coli grown from explanted cages in TSB (i.e., treatment failures) was screened for emergence of resistance to fosfomycin, tigecycline, or colistin, as described for the emergence of in vitro resistance.

Statistical analysis.

Comparisons were performed by using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and a two-sided χ2 or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. For all tests, differences were considered significant when P values were <0.05. Figures were plotted with GraphPad Prism (version 6.01) software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility.

Table 1 summarizes the antimicrobial susceptibility of E. coli to fosfomycin, tigecycline, colistin, and gentamicin. In logarithmic growth, fosfomycin and colistin killed E. coli at concentrations of <0.5 μg/ml, whereas gentamicin and tigecycline required higher concentrations (MBClog of 8 μg/ml and 32 μg/ml, respectively). In stationary growth, the MBCstat for colistin was low (2 μg/ml), that for fosfomycin was intermediate (8 μg/ml), and those for gentamicin and tigecycline were high (16 and 32 μg/ml, respectively).

Table 1.

Susceptibility of E. coli Bj HDE-1 to fosfomycin, tigecycline, colistin, and gentamicin

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml) | MBClog (μg/ml) | MBCstat (μg/ml) | MBCstat/MBClog ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fosfomycin | 0.12 | 0.12 | 8 | 66 |

| Tigecycline | 0.25 | 32 | 32 | 1 |

| Colistin | 0.25 | 0.5 | 2 | 4 |

| Gentamicin | 2 | 8 | 16 | 2 |

Time-kill studies.

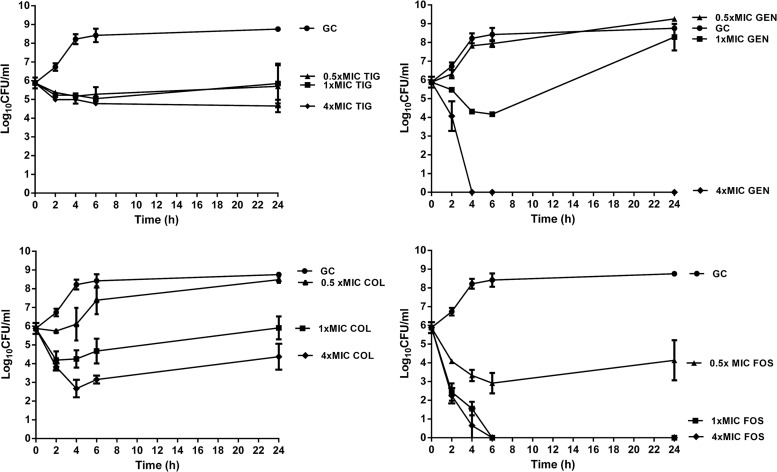

Figure 1 shows the time-kill curves. Bacterial counts increased to 5 × 108 CFU/ml after 24 h without antimicrobials (growth control). With tigecycline, bacterial counts remained unchanged at 0.5× and 1× the MIC and decreased ∼1 log10 CFU/ml at 4× the MIC at 24 h. With gentamicin, regrowth occurred at 0.5× and 1× the MIC at 24 h, but a rapid bactericidal activity with undetectable bacterial counts was observed at 4× the MIC after 4 h. Colistin showed concentration-dependent activity, with a maximum decrease of 3.1 log10 CFU/ml, but regrowth was observed after 24 h. Fosfomycin demonstrated rapid bactericidal activity, independent of the drug concentration at or above the MIC.

Fig 1.

Time-kill curves with 0.5, 1, and 4× the MIC of tigecycline (TIG), colistin (COL), fosfomycin (FOS), and gentamicin (GEN) against E. coli in log growth phase (inoculum, 106 CFU/ml). Values are means ± SD. The experiments were performed in triplicate. GC, growth control.

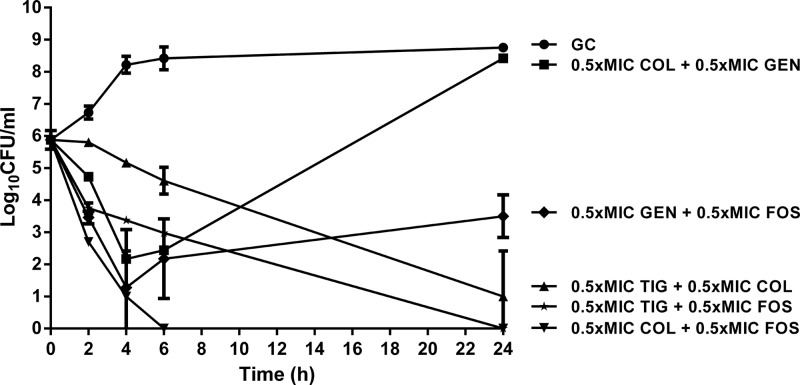

Figure 2 shows time-kill curves of antimicrobial combinations at fixed concentration of 0.5× the MIC. Tigecycline in combination with colistin and fosfomycin decreased bacterial counts at 24 h by 4.5 and 5.5 log10 CFU/ml, respectively. Regrowth was observed with gentamicin either in combination with colistin (to 3 × 108 CFU/ml) or fosfomycin (to 3.8 × 103 CFU/ml) at 24 h. Synergistic activity was observed between fosfomycin and colistin with undetectable bacterial counts after 6 h and without regrowth at 24 h.

Fig 2.

Time-kill curves with 0.5× the MIC of tigecycline (TIG), colistin (COL), fosfomycin (FOS), and gentamicin (GEN) in combinations against E. coli in log growth phase (inoculum, 106 CFU/ml). Values are means ± SD. The experiments were performed in triplicate. GC, growth control.

Emergence of antimicrobial resistance in vitro.

No growth of E. coli was observed on MHA containing fosfomycin, colistin, or tigecycline at 4× the MIC.

Evaluation of antibiofilm activity using microcalorimetry.

Table 2 summarizes the MHIC values for the antimicrobial agents tested. Fosfomycin showed excellent activity against biofilm on glass beads and suppressed heat production at or below the MIC (42). Tigecycline and colistin suppressed heat production only at high concentrations (128 and 32 μg/ml), whereas gentamicin showed intermediate activity against E. coli biofilm (at 2× the MBClog, i.e., 16 μg/ml). No differences in antibiofilm activity were observed among 3-h, 12-h, and 24-h biofilms.

Table 2.

Activity against E. coli Bj HDE-1 biofilms on glass beads, evaluated by microcalorimetry

| Antimicrobial agent | MHIC (μg/ml) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-h biofilm | 12-h biofilm | 24-h biofilm | |

| Fosfomycin | 0.12 | <0.12 | <0.12 |

| Tigecycline | 128 | 128 | 128 |

| Colistin | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Gentamicin | 8 | 16 | 16 |

Antimicrobial treatment study.

All cage fluid samples aspirated before infection were sterile. Twenty-four hours after infection, the mean (± SD) concentration of bacteria in the cage fluid was 5.3 log10 CFU/ml (± 0.5 log10 CFU/ml). Neither clearance of planktonic bacteria nor spontaneous cure of biofilm bacteria occurred in any cage from untreated animals.

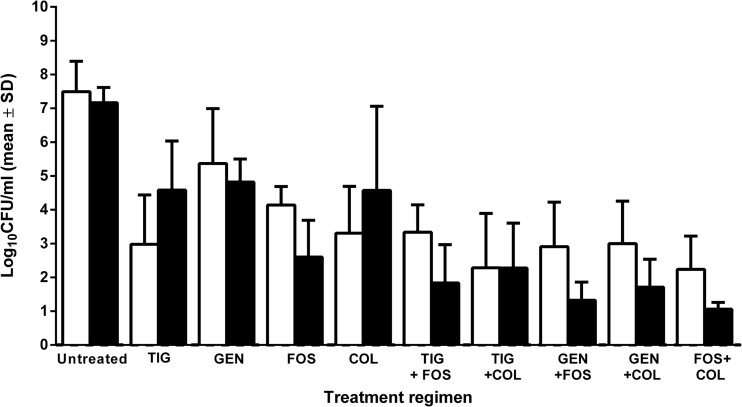

(i) Activity against planktonic bacteria.

Figure 3 shows the counts of planktonic bacteria in cage fluid during treatment and 5 days after end of treatment. In untreated animals, bacterial counts in cage fluid increased to 7.5 and 7.2 log10 CFU/ml, respectively, which corresponds to an increase of 2.2 and 1.9 log10 CFU/ml, respectively. During treatment, the count of planktonic bacteria (in log10 CFU/ml) decreased in comparison with untreated control by 2.1 (with gentamicin), 3.3 (with fosfomycin), 4.2 (with colistin), and 4.5 (with tigecycline). After treatment, regrowth was observed in animals treated with colistin and tigecycline (an increase compared to the bacterial counts during treatment of 1.3 and 1.6 log10 CFU/ml, respectively), whereas bacterial counts remained unchanged with gentamicin. With fosfomycin a decrease of 4.7 log10 CFU/ml was observed. After the end of treatment, all regimens showed significantly lower bacterial counts than untreated controls (P < 0.01, except for colistin, where P < 0.05).

Fig 3.

Activities against planktonic bacteria in cage fluid aspirated during treatment (i.e., day 5; open bars) and 5 days after end of treatment (i.e., day 10; closed bars). In each group, fluid from 12 cages (from 3 animals) was investigated. The y axis shows log10 CFU/ml in aspirated cage fluid, expressed as means ± standard deviations (SD).

When colistin or fosfomycin was added to gentamicin or tigecycline, bacterial counts were reduced by >3.0 log10 CFU/ml (during and after treatment), which was significantly lower than with gentamicin or tigecycline alone (P < 0.01). With the combination tigecycline plus colistin bacterial counts remained unchanged. All other combinations decreased bacterial counts (in log10 CFU/ml) by 1.5 (fosfomycin plus tigecycline), 1.6 (fosfomycin plus gentamicin), 1.2 (fosfomycin plus colistin) and 1.3 (colistin plus gentamicin), although they did not reach a 2-log10 CFU/ml reduction and were thus not synergistic. The combination of fosfomycin plus colistin was significantly more active against planktonic bacteria than each single drug (P < 0.01).

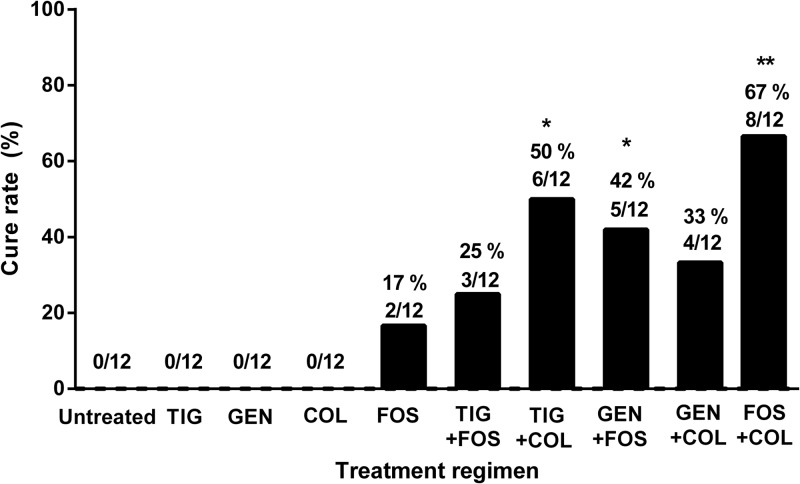

(ii) Activity against biofilm bacteria.

Figure 4 shows the cure rates of all treatment regimens. Fosfomycin was the only single agent which was able to eradicate some E. coli biofilms (cure in 17% of cages). In combination, colistin plus tigecycline (50%) and fosfomycin plus gentamicin (42%) cured significantly more infected cages than colistin plus gentamicin (33%) or fosfomycin plus tigecycline (25%) (P < 0.05). The combination of fosfomycin plus colistin showed the highest cure rate (67%), which was significantly better than that of fosfomycin alone (P < 0.05).

Fig 4.

Rate of cure of cage-associated infection. The values are numbers of cage cultures without growth of E. coli divided by the total number of cages in the treatment group (n = 12). Significant differences compared to untreated controls are indicated with asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Emergence of antimicrobial resistance in vivo.

No resistant strains were detected in positive cultures from cages.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the activities of fosfomycin, tigecycline, colistin, and gentamicin against an ESBL-producing E. coli strain. This organism was chosen because it has been well characterized at the molecular level (13) and is resistant to ciprofloxacin, reflecting the current epidemiology in PJI (7) and classifying this organism among difficult-to-treat organisms (4, 43, 44).

The test strain was highly susceptible to fosfomycin, tigecycline, and colistin (all MICs ≤ 0.25 μg/ml), as well as to gentamicin (MIC = 2 μg/ml), which is still in the susceptible range according to the EUCAST and CLSI guidelines. However, a reduction of ≥99.9% CFU/ml was achieved only with fosfomycin and colistin, both in logarithmic and stationary growth (at concentrations which are achievable in the clinical setting). This is in agreement with the reported bactericidal activity of fosfomycin and colistin against Gram-negative bacilli (45, 46). For gentamicin, the MBClog was 8 and MBCstat was 16 μg/ml, which are achievable with once-daily dosing in humans. In contrast, tigecycline exhibits bacteriostatic activity and does not seem to be effective as a single agent against implant-associated infections due to Gram-negative bacilli (23). However, synergy with colistin has been reported against MBL (VIM-1)- and ESBL (SHV-12)-producing Klebsiella pneumonia (47).

In the time-kill studies, bacterial regrowth was detected after 24 h in all experiments using colistin alone. Regrowth was previously reported with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (48) and Acinetobacter baumannii (49), which may possibly be explained by the short half-life of colistin (50). In contrast, colistin in combination with tigecycline or fosfomycin (but not with gentamicin) prevented regrowth at subinhibitory concentration (0.5× the MIC). Neither fosfomycin nor colistin prevented regrowth when combined with gentamicin. In a time-kill curve assay, the most active single agent was fosfomycin, which exhibited a synergistic effect in combination with colistin. Tigecycline combined with fosfomycin or colistin was also active against planktonic bacteria.

The microcalorimetry glass bead method mimics the Calgary biofilm device, where antibiotic activity against biofilms is determined by the antibiotic challenge and biofilm recovery method (7). Fosfomycin revealed the lowest MIHC, supporting other studies demonstrating its ability to kill bacteria in biofilms (20, 51). Interestingly, no correlation between the biofilm age and the antibiofilm activity was observed in our study.

In an animal study using the same animal model, E. coli counts increased in the cage fluid over 10 days, and no spontaneous cure occurred in untreated animals (52); the infection profile was also similar to the one previously reported in the same experimental model (53).

The bacterial count of planktonic bacteria in cage fluid slightly decreased after the end of treatment in untreated control animals, but no spontaneous cure was observed. Reduction of bacterial counts can be explained due to an unfavorable environment (e.g., anoxic conditions), the biofilm mode of growth, or the postantibiotic effect. The presence of neutrophils may also prolong the in vivo postantibiotic effect (54).

Fosfomycin was the only single agent which achieved eradication of E. coli from cages, although the cure rate was only 17%. When fosfomycin was combined with colistin, the activity against both planktonic and biofilm bacteria was significantly improved, achieving a cure rate of 67%. This observation suggests that fosfomycin has potential for the treatment of Gram-negative implant-related infections (55), especially in combination with colistin (with or without tigecycline) in the case of fluoroquinolone resistance (7). Recently, fosfomycin showed improved activity against P. aeruginosa biofilms in a rat model of urinary tract infection (56). The small size of the fosfomycin molecule may explain its ability to penetrate established biofilm, including bacteria in stationary growth phase (57). Despite the fact that no emergence of resistance to fosfomycin, tigecycline, or colistin was observed in our study in vitro and in vivo, selection and/or emergence of resistant strains may occur during treatment. The emergence of colistin-heteroresistant subpopulations was recently reported (58).

In conclusion, the combination of fosfomycin and colistin showed the highest antibiofilm activity against the ESBL-producing E. coli strain in vitro and in the animal model. This combination presents a promising treatment option for implant-associated infections caused by fluoroquinolone-resistant Gram-negative bacilli and deserves further laboratory and clinical study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Marie-Hélène Nicolas-Chanoine for providing the CTX-M15-producing E. coli strain Bj HDE-1. We thank Raluca Mihailescu and Alessandra Oliva for critical review of the manuscript.

This study was supported by an educational grant from the University Hospital (CHU) of Nantes, France, to Stéphane Corvec and by InfectoPharm, Heppenheim, Germany.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Sendi P, Zimmerli W. 2011. Challenges in periprosthetic knee-joint infection. Int. J. Artif. Organs 34:947–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zimmerli W, Moser C. 2012. Pathogenesis and treatment concepts of orthopaedic biofilm infections. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 65:158–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moran E, Byren I, Atkins BL. 2010. The diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65(Suppl. 3):iii45–iii54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trampuz A, Widmer AF. 2006. Infections associated with orthopedic implants. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 19:349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martinez-Pastor JC, Munoz-Mahamud E, Vilchez F, Garcia-Ramiro S, Bori G, Sierra J, Martinez JA, Font L, Mensa J, Soriano A. 2009. Outcome of acute prosthetic joint infections due to gram-negative bacilli treated with open debridement and retention of the prosthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4772–4777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hsieh PH, Lee MS, Hsu KY, Chang YH, Shih HN, Ueng SW. 2009. Gram-negative prosthetic joint infections: risk factors and outcome of treatment. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:1036–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martinez-Pastor JC, Vilchez F, Pitart C, Sierra JM, Soriano A. 2010. Antibiotic resistance in orthopaedic surgery: acute knee prosthetic joint infections due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29:1039–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Legout L, Senneville E, Stern R, Yazdanpanah Y, Savage C, Roussel-Delvalez M, Rosele B, Migaud H, Mouton Y. 2006. Treatment of bone and joint infections caused by Gram-negative bacilli with a cefepime-fluoroquinolone combination. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12:1030–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paladino JA, Callen WA. 2003. Fluoroquinolone benchmarking in relation to pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51(Suppl 1):43–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trampuz A, Zimmerli W. 2006. Antimicrobial agents in orthopaedic surgery: prophylaxis and treatment. Drugs 66:1089–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sendi P, Frei R, Maurer TB, Trampuz A, Zimmerli W, Graber P. 2010. Escherichia coli variants in periprosthetic joint infection: diagnostic challenges with sessile bacteria and sonication. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1720–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cremet L, Corvec S, Bemer P, Bret L, Lebrun C, Lesimple B, Miegeville AF, Reynaud A, Lepelletier D, Caroff N. 2012. Orthopaedic-implant infections by Escherichia coli: molecular and phenotypic analysis of the causative strains. J. Infect. 64:169–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V, Demarty R, Alonso MP, Canica MM, Park YJ, Lavigne JP, Pitout J, Johnson JR. 2008. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:273–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clermont O, Lavollay M, Vimont S, Deschamps C, Forestier C, Branger C, Denamur E, Arlet G. 2008. The CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli diffusing clone belongs to a highly virulent B2 phylogenetic subgroup. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:1024–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cooper MA, Shlaes D. 2011. Fix the antibiotics pipeline. Nature 472:32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pogue JM, Marchaim D, Kaye D, Kaye KS. 2011. Revisiting “older” antimicrobials in the era of multidrug resistance. Pharmacotherapy. 31:912–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raz R. 2012. Fosfomycin: an old-new antibiotic. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:4–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yahav D, Farbman L, Leibovici L, Paul M. 2012. Colistin: new lessons on an old antibiotic. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:18–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carlet J, Mainardi JL. 2012. Antibacterial agents: back to the future? Can we live with only colistin, co-trimoxazole and fosfomycin? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cai Y, Fan Y, Wang R, An MM, Liang BB. 2009. Synergistic effects of aminoglycosides and fosfomycin on Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and biofilm infections in a rat model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:563–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schintler MV, Traunmuller F, Metzler J, Kreuzwirt G, Spendel S, Mauric O, Popovic M, Scharnagl E, Joukhadar C. 2009. High fosfomycin concentrations in bone and peripheral soft tissue in diabetic patients presenting with bacterial foot infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:574–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miro JM, Entenza JM, Del Rio A, Velasco M, Castaneda X, Garcia de la Maria C, Giddey M, Armero Y, Pericas JM, Cervera C, Mestres CA, Almela M, Falces C, Marco F, Moreillon P, Moreno A, the Hospital Clinic Experimental Endocarditis Study Group 2012. High-dose daptomycin plus fosfomycin is safe and effective in treating methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:4511–4515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Entenza JM, Moreillon P. 2009. Tigecycline in combination with other antimicrobials: a review of in vitro, animal and case report studies. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34:8.e1-8e.9 doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Azzopardi EA, Ferguson EL, Thomas DW. 2012. Colistin past and future: a bibliographic analysis. J. Crit. Care [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Furustrand Tafin U, Corvec S, Betrisey B, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A. 2012. Role of rifampin against Propionibacterium acnes biofilm in vitro and in an experimental foreign-body infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:1885–1891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. John AK, Baldoni D, Haschke M, Rentsch K, Schaerli P, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A. 2009. Efficacy of daptomycin in implant-associated infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: importance of combination with rifampin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2719–2724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zimmerli W, Frei R, Widmer AF, Rajacic Z. 1994. Microbiological tests to predict treatment outcome in experimental device-related infections due to Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 33:959–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Furustrand Tafin U, Majic I, Zalila Belkhodja C, Betrisey B, Corvec S, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A. 2011. Gentamicin improves the activities of daptomycin and vancomycin against Enterococcus faecalis in vitro and in an experimental foreign-body infection model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4821–4827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baldoni D, Haschke M, Rajacic Z, Zimmerli W, Trampuz A. 2009. Linezolid alone or combined with rifampin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in experimental foreign-body infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1142–1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute 2012. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that growth aerobically; approved guideline-ninth edition. M07-A9. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute 1999. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents; approved guideline—first edition. M26-A. Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 32. Astasov-Frauenhoffer M, Braissant O, Hauser-Gerspach I, Daniels AU, Weiger R, Waltimo T. 2012. Isothermal microcalorimetry provides new insights into biofilm variability and dynamics. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 337:31–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Poeppl W, Tobudic S, Lingscheid T, Plasenzotti R, Kozakowski N, Georgopoulos A, Burgmann H. 2011. Efficacy of fosfomycin in experimental osteomyelitis due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:931–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Poeppl W, Tobudic S, Lingscheid T, Plasenzotti R, Kozakowski N, Lagler H, Georgopoulos A, Burgmann H. 2011. Daptomycin, fosfomycin, or both for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis in an experimental rat model. Antimicrobial. Agents Chemother. 55:4999–5003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pachon-Ibanez ME, Ribes S, Dominguez MA, Fernandez R, Tubau F, Ariza J, Gudiol F, Cabellos C. 2011. Efficacy of fosfomycin and its combination with linezolid, vancomycin and imipenem in an experimental peritonitis model caused by a Staphylococcus aureus strain with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30:89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ribes S, Taberner F, Domenech A, Cabellos C, Tubau F, Linares J, Viladrich PF, Gudiol F. 2006. Evaluation of fosfomycin alone and in combination with ceftriaxone or vancomycin in an experimental model of meningitis caused by two strains of cephalosporin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:931–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Niska JA, Shahbazian JH, Ramos RI, Pribaz JR, Billi F, Francis KP, Miller LS. 2012. Daptomycin and tigecycline have broader effective dose ranges than vancomycin as prophylaxis against a Staphylococcus aureus surgical implant infection in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:2590–2597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yin LY, Lazzarini L, Li F, Stevens CM, Calhoun JH. 2005. Comparative evaluation of tigecycline and vancomycin, with and without rifampicin, in the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus experimental osteomyelitis in a rabbit model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:995–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marchand S, Lamarche I, Gobin P, Couet W. 2010. Dose-ranging pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulphonate (CMS) and colistin in rats following single intravenous CMS doses. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1753–1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Garrigos C, Murillo O, Lora-Tamayo J, Verdaguer R, Tubau F, Cabellos C, Cabo J, Ariza J. 2013. Fosfomycin-daptomycin and other fosfomycin combinations as alternative therapies in experimental foreign body infection by methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:606–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Trampuz A, Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, Hanssen AD, Unni KK, Osmon DR, Mandrekar JN, Cockerill FR, Steckelberg JM, Greenleaf JF, Patel R. 2007. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 357:654–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. von Ah U, Wirz D, Daniels AU. 2009. Isothermal micro calorimetry—a new method for MIC determinations: results for 12 antibiotics and reference strains of E. coli and S. aureus. BMC Microbiol. 9:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Falagas ME, Karageorgopoulos DE, Nordmann P. 2011. Therapeutic options for infections with Enterobacteriaceae producing carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzymes. Future Microbiol. 6:653–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. 2004. Prosthetic-joint infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 351:1645–1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nation RL, Li J. 2009. Colistin in the 21st century. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 22:535–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roussos N, Karageorgopoulos DE, Samonis G, Falagas ME. 2009. Clinical significance of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics of fosfomycin for the treatment of patients with systemic infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34:506–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cobo J, Morosini MI, Pintado V, Tato M, Samaranch N, Baquero F, Canton R. 2008. Use of tigecycline for the treatment of prolonged bacteremia due to a multiresistant VIM-1 and SHV-12 beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae epidemic clone. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 60:319–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gunderson BW, Ibrahim KH, Hovde LB, Fromm TL, Reed MD, Rotschafer JC. 2003. Synergistic activity of colistin and ceftazidime against multiantibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:905–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wareham DW, Gordon NC, Hornsey M. 2011. In vitro activity of teicoplanin combined with colistin versus multidrug-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1047–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Couet W, Gregoire N, Gobin P, Saulnier PJ, Frasca D, Marchand S, Mimoz O. 2011. Pharmacokinetics of colistin and colistimethate sodium after a single 80-mg intravenous dose of CMS in young healthy volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 89:875–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tang HJ, Chen CC, Cheng KC, Toh HS, Su BA, Chiang SR, Ko WC, Chuang YC. 2012. In vitro efficacy of fosfomycin-containing regimens against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:944–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Blaser J, Vergeres P, Widmer AF, Zimmerli W. 1995. In vivo verification of in vitro model of antibiotic treatment of device-related infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1134–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Widmer AF, Wiestner A, Frei R, Zimmerli W. 1991. Killing of nongrowing and adherent Escherichia coli determines drug efficacy in device-related infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:741–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Craig WA. 1993. Post-antibiotic effects in experimental infection models: relationship to in-vitro phenomena and to treatment of infections in man. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 31(Suppl D):149–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rodriguez-Martinez JM, Ballesta S, Pascual A. 2007. Activity and penetration of fosfomycin, ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and co-trimoxazole in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30:366–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mikuniya T, Kato Y, Ida T, Maebashi K, Monden K, Kariyama R, Kumon H. 2007. Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms with a combination of fluoroquinolones and fosfomycin in a rat urinary tract infection model. J. Infect. Chemother. 13:285–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Marchese A, Bozzolasco M, Gualco L, Debbia EA, Schito GC, Schito AM. 2003. Effect of fosfomycin alone and in combination with N-acetylcysteine on E. coli biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 22(Suppl 2):95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Meletis G, Tzampaz E, Sianou E, Tzavaras I, Sofianou D. 2011. Colistin heteroresistance in carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:946–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]