Abstract

Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms represent a problematic clinical entity, especially because of their recalcitrance to antifungal drugs, which poses a number of therapeutic implications for invasive aspergillosis, the most difficult-to-treat Aspergillus-related disease. While the antibiofilm activities of amphotericin B (AMB) deoxycholate and its lipid formulations (e.g., liposomal AMB [LAMB]) are well documented, the effectiveness of these drugs in combination with nonantifungal agents is poorly understood. In the present study, in vitro interactions between polyene antifungals (AMB and LAMB) and alginate lyase (AlgL), an enzyme degrading the polysaccharides produced as extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) within the biofilm matrix, against A. fumigatus biofilms were evaluated by using the checkerboard microdilution and the time-kill assays. Furthermore, atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used to image and quantify the effects of AlgL-antifungal combinations on biofilm-growing hyphal cells. On the basis of fractional inhibitory concentration index values, synergy was found between both AMB formulations and AlgL, and this finding was also confirmed by the time-kill test. Finally, AFM analysis showed that when A. fumigatus biofilms were treated with AlgL or polyene alone, as well as with their combination, both a reduction of hyphal thicknesses and an increase of adhesive forces were observed compared to the findings for untreated controls, probably owing to the different action by the enzyme or the antifungal compounds. Interestingly, marked physical changes were noticed in A. fumigatus biofilms exposed to the AlgL-antifungal combinations compared with the physical characteristics detected after exposure to the antifungals alone, indicating that AlgL may enhance the antibiofilm activity of both AMB and LAMB, perhaps by disrupting the hypha-embedding EPSs and thus facilitating the drugs to reach biofilm cells. Taken together, our results suggest that a combination of AlgL and a polyene antifungal may prove to be a new therapeutic strategy for invasive aspergillosis, while reinforcing the EPS as a valuable antibiofilm drug target.

INTRODUCTION

Similar to biofilm-forming bacteria or yeasts (1), Aspergillus fumigatus, the most prevalent airborne fungal pathogen (2), is now largely acknowledged to be an organism able to grow and develop as a multicellular community (3), in which the hyphae are cohesively bonded together by a hydrophobic extracellular matrix (ECM) (4), under the aerial and static conditions found by the fungus either in vitro or in vivo (5–9). This growth phenotype, which complies with the definition of a biofilm (10), may help A. fumigatus to colonize the host substratum and to resist phagocytic and antimicrobial attacks, mimicking the typical Candida albicans or bacterial biofilm (8, 11). Recent observations have consistently shown that all antifungal drugs are significantly less effective when A. fumigatus is grown as a biofilm than when it is grown in the planktonic state (4, 7, 9, 12, 13), presumably as a reflection of multiple resistance mechanisms, including the ECM, which would prevent drug diffusion by acting as a physical barrier (14). This could contribute to the overall mortality with invasive aspergillosis, which remains high, despite the use of newer broad-spectrum antifungal agents and diagnostic adjuncts (15).

Amphotericin B (AMB), a macrocyclic, polyene broad-spectrum antifungal agent, preferably given as a lipid preparation (i.e., liposomal AMB [LAMB]) (16), is currently used in clinical practice for the treatment of invasive aspergillosis (17). However, high concentrations of AMB (at least 8 μg/ml) are needed to inhibit hyphal clumps (6, 18) or mature mycelia in vitro (13), although AMB was seen to be significantly more effective against each phase of A. fumigatus biofilm development and to display more rapid effects than other antifungals, such as voriconazole or caspofungin (13). In contrast to AMB deoxycholate, unique efficacy against Candida (C. albicans and C. parapsilosis) biofilms grown on a bioprosthetic model was displayed by lipid-formulated AMB (19), probably due to the higher doses of drug present in these formulations. In another study, LAMB at 0.5 μg/ml was able to eradicate a C. albicans biofilm in a continuous-flow catheter model, whereas fluconazole and caspofungin were less effective (20). This somewhat surprising, different behavior between formulations of the same antifungal compound, coupled with the paucity of studies comparing their activities against fungal pathogens other than Candida, has enlivened our interest in testing both AMB formulations on an A. fumigatus biofilm.

Newer treatment strategies that incorporate substances not classified as antimicrobials, such as enzymes (e.g., DNase and alginate lyase [AlgL]) or quorum-sensing inhibitors, appear to increase biofilm susceptibility to conventional antibiotics (21, 22). If it should also be true with antifungals, this would allow the therapeutic dosage of AMB to be reduced, which is an advantage, given the well-known side effects and toxicity of the drug (23) as well as the cost of LAMB therapy, which limits its large-scale application, despite fewer adverse events and less nephrotoxicity than AMB deoxycholate (16). In this regard, it was shown that AlgL, a carbohydrate-active enzyme which degrades uronic acid-containing polysaccharides (24) such as the alginate produced in exopolymeric substances (EPSs) by mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, enhances antibiotic killing of alginate-producing P. aeruginosa in biofilms (25). In a recent work by Alipour et al. (21), addition of AlgL reduced the minimum biofilm eradication concentrations of free (conventional) and liposome-encapsulated aminoglycosides for mucoid P. aeruginosa strain PA-489121, although there was no significant difference between the free and liposomal forms of the antibiotics tested. To our knowledge, alginate has been not identified in the A. fumigatus ECM, which is mainly composed of galactomannan and α-1,3-glucans (4). However, other polyuronates, such as polyglucuronate (glucuronan), are found in fungi as water-soluble polysaccharides that are commonly degraded by AlgL-like enzymes (26) but that could be attacked nonspecifically by the bacterial AlgL.

In the present study, we investigated the in vitro effects of combinations of both AMB and LAMB with AlgL against preformed A. fumigatus biofilms, in an attempt to clarify the intriguing issues mentioned above. Besides assessing the drug interaction by conventional methods, we used atomic force microscopy (AFM), a recently emerged powerful technique for the analysis of microbial systems (27), to further evaluate the extent of these effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal organisms, culture conditions, and inoculum preparation.

The A. fumigatus Af293 (ATCC MYA-4609, CBS 101355) type strain (28) and 31 clinical isolates (29; M. Sanguinetti, unpublished data) were used throughout this study. All the isolates were retrieved from their frozen glycerol stocks and were streaked on fresh Sabouraud dextrose agar (Kima, Padua, Italy) plates, until good sporulation was achieved following incubation at 37°C. For all experiments, conidial suspensions in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan, Italy) were obtained as described elsewhere (12, 28) and used to prepare the inocula (see below).

Biofilm formation and quantification.

A. fumigatus biofilms were grown statically for 24 h at 37°C on polystyrene, flat-bottom, 96-well microtiter plates (Thermo Scientific, Milan, Italy) or, only for AFM studies, on 13-mm-diameter glass coverslips (Bioscience Tools, San Diego, CA) placed into a standard 24-well cell culture plate (Thermo Scientific), by dispensing a cell inoculum prepared as described above into selected wells of the plate(s). After biofilm formation, the medium was aspirated and the plates were washed in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove planktonic and/or nonadherent cells. Biofilm biomass was assessed as described elsewhere (6). Briefly, biofilms were stained with 0.5% (wt/vol) crystal violet solution for 5 min, rinsed with distilled water, and destained with 95% ethanol. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm with a microtiter plate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) in order to determine the quantity of biological material produced (data not shown).

Antifungal and AlgL solutions.

Standard powders of the following antifungals were used: AMB (Sigma-Aldrich) and LAMB (Gilead Sciences, Milan, Italy). Their stock solutions were freshly prepared according to the manufacturers' guidelines. The AlgL from Flavobacterium species (28,000 U/g) was purchased as a pure substance from Sigma-Aldrich, and a stock solution was freshly prepared in sterile PBS.

Determination of MIC.

The MICs for planktonic cells (PMICs) were determined with the reference Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M38-A2 broth microdilution method (30), using final drug concentrations that ranged from 0.008 to 8 μg/ml for both the AMB and LAMB antifungals. Briefly, for each A. fumigatus isolate, a conidial inoculum was prepared in RPMI 1640 medium and quantified to achieve a final concentration of 0.4 × 104 to 5 × 104 conidia/ml. Following incubation of the microtiter plates for 48 h at 37°C, MIC (inhibitory concentration [IC]) endpoints were defined as the lowest drug concentrations that caused complete visible inhibition of growth compared with that of the drug-free growth control (30). Testing of each isolate was performed in triplicate.

The MICs for sessile (biofilm) cells (SMICs) were determined by a 96-well microtiter-based method as previously described (12) with an inoculum of 1 × 105 conidia/ml (6) and with AMB and LAMB concentrations ranging from 0.125 to 128 μg/ml. This method, originally developed for investigating yeast adhesion and susceptibility but subsequently adapted to A. fumigatus (6, 31), is based on the reduction of 2,3-bis{2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-[(sulfenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium-hydroxide} (XTT) by metabolically active sessile cells (28). Briefly, biofilm-containing wells were filled with RPMI 1640 medium which contained doubling concentrations of the antifungal drugs, whereas untreated biofilm wells (positive controls) were filled with the same medium without drugs for 24 h at 37°C. A 100-μl aliquot of the XTT salt solution (1 mg/ml in PBS) and 1 μM menadione solution (Sigma-Aldrich; prepared in 100% acetone) were added to each prewashed biofilm and to negative-control wells (for measurement of background XTT reduction levels). After measuring the amount of XTT formazan at 490 nm (12), SMICs were calculated and expressed as the lowest drug concentrations at which a 90% decrease in optical density (OD; i.e., a 90% reduction in fungal metabolism) in comparison with that for the biofilms formed in the absence of drug was detected. Testing of each isolate was performed in triplicate.

Checkerboard susceptibility testing.

A two-dimensional (8-by-12) checkerboard array of serial concentrations of the test compounds was used in sterile 96-well, flat-bottom microtiter plates as the basis for calculation of a fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index (see below and references 32 and33) for each of two designed combinations: AMB-AlgL and LAMB-AlgL. Isolates Af293 and CG261 (CG261 is one of the clinical isolates showing the highest antifungal SMICs) were tested in quadruplicate. The compounds were serially diluted 2-fold in the assay medium in order to obtain four times the final concentration, which ranged from 0.016 to 8 μg/ml for AMB or LAMB and from 0.06 to 40 U/ml for AlgL. The AlgL concentrations were chosen since a concentration of 30 U/ml had previously been shown to be sufficient to reduce biofilm formation in A. fumigatus (34) and was consistent with that reported by other authors (21). Wells were inoculated with 5 × 104 cells/ml of each isolate, and after incubation at 37°C for 48 h, the growth in the wells relative to the growth in the growth control well was visually recorded. The same checkerboard assay was used to test in quadruplicate the combinations of AMB-AlgL and LAMB-AlgL against the biofilms formed by Af293 and CG261 as described above, using concentration ranges of 0.125 to 128 μg/ml for the antifungals and 0.06 to 40 U/ml for AlgL, in accordance with the SMICs of the individual compounds. After incubation of the microtiter plates at 37°C for 24 h, the wells were washed and the metabolic activity of sessile cells was assessed using the XTT reduction assay, as specified above. The MICs of the compounds alone and of the isoeffective combinations were determined to be the first concentrations of compound showing no visual growth (optically clear well) (PMICs) or growth near 10% of the growth of an untreated control (SMICs). The drug interactions were analyzed using the nonparametric FIC index model based on the Loewe additivity zero-interaction theory (32). Synergy and antagonism were defined by FIC index values of ≤0.5 and >4, respectively, whereas values of >0.5 to 4.0 were indicative of no interaction (additivity/indifference) (35, 36).

Time-kill curves.

To investigate the effect of concentration and exposure time on the activity of AlgL alone or in combination with AMB and LAMB, time-kill experiments were carried out using an adaptation of the methodology used by Zhou et al. (37). The 24-h-old Af293 and CG261 biofilms, developed in microtiter plates as described above, were incubated with defined concentrations of each compound (AlgL, 1.0 and 10 U/ml; AMB and LAMB, 8, 16, and 32 μg/ml) in RPMI 1640 medium under shaking (75 rpm) at 37°C. At different time points (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h) after incubation, the content of each well was aspirated and washed twice with PBS. Then, 100 μl of XTT-menadione solution was added. After 2 h of incubation, the XTT solution was transferred to the corresponding well of a new microtiter plate, and colorimetric changes were measured as described above. For each isolate tested, the experiments were performed in triplicate on two separate days.

AFM imaging and force measurement.

To further evaluate the effect of both AMB formulations in combination with AlgL, samples for AFM studies were prepared as previously described (34). Briefly, 24-h-old A. fumigatus biofilms that were formed on glass coverslips as mentioned above were treated with AlgL (10 U/ml), AMB (4 μg/ml), and LAMB (4 μg/ml) or with their combinations at 37°C for 24 h. Samples were then rinsed gently with ultrapure water and air dried for AFM imaging and force spectroscopy by using a NanoWizard II atomic force microscope (JPK Instruments, Berlin, Germany) in conjunction with an optical microscope (Axio Observer; Carl Zeiss, Milan, Italy). Atomic force micrographs were collected in contact mode using Si3N4 cantilevers (CSC16; Mikromasch USA, San Jose, CA) with the manufacturer's quoted resonance frequencies of 10 kHz (range, 7 to 14 kHz) and force constants of 0.03 N/m (range, 0.01 to 0.08 N/m) in air. Scanning across the sample surface in the x and y directions was performed at a scan speed of 1 Hz. The images shown are typical results, and they were recorded in both height and deflection modes. To analyze the adhesion force over the biofilm surface, force curves were acquired by recording the cantilever deflection as a function of the vertical displacement of the samples (34), in order to give the variation of the deflection signal per nanometer. During the force-distance measurement, the scanning rate in the z direction was performed at 1 Hz. A Gwyddion image viewer (http://gwyddion.net) was used to analyze high-resolution topographic images (500 by 500 lines per scan) of the surface changes (e.g., height [in nanometers]), as well as force-distance measurements over the sample surface. Values were averaged from force curves collected in triplicate at 10 different points on the surface of mature biofilms for five areas per sample from each experimental condition.

Statistics.

Data are expressed as medians with ranges, unless otherwise specified. The absorbance values of individual biofilms were compared by one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's multiple-comparison posttest, whereas the hyphal height and adhesive force values of individual biofilms were analyzed with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Differences were considered statistically significant for a P value of <0.05. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.00) for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Biofilms, likely the preferred growth form of fungi (1), exhibit profound resistance to many antimicrobial agents, thereby representing an escalating problem in the context of human health (8). First, the activities of both AMB and LAMB against a series of clinical A. fumigatus isolates, mostly derived from cases of invasive pulmonary infection, were determined (29). As expected, elevated concentrations of AMB and LAMB were required to inhibit 90% of the isolates in the presence of biofilm (SMIC90, 16 μg/ml) compared to those required for the planktonic conditions (PMIC90s of AMB and LAMB, 0.5 and 0.125 μg/ml, respectively), as assessed by metabolic activity (XTT reduction assay) measurements (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Then, one of these isolates, CG261, was used, together with the A. fumigatus reference strain Af293, to evaluate the potential of AlgL to enhance the in vitro activity of AMB and LAMB against fungal biofilms.

Drug interaction studies.

We applied checkerboard microdilution analysis to investigate the effect of AlgL on the antifungal activities of AMB and LAMB against biofilm cells of A. fumigatus Af293 and CG261. As summarized in Table 1, SMICs of AMB and LAMB for sessile cells of both the isolates increased up to 32- and 128-fold, respectively, for Af293 (PMICs, 0.5 and 0.125 μg/ml, respectively) and up to 128- and 512-fold, respectively, for CG261 (PMICs, 0.25 and 0.0625 μg/ml, respectively). In contrast, SMIC values for Af293 and CG261 of AMB and AlgL tested in combination decreased to 8 μg/ml and 10 U/ml, respectively, whereas those of LAMB and AlgL decreased to 2 μg/ml and 10 U/ml, respectively, when the two compounds were combined. Also, the FIC indices for the two tested isolates ranged from 0.312 to 0.75 and from 1.5 to 3 when analyzed using the SMIC and the PMIC endpoints, respectively, and in no case was antagonism observed (Table 1). Unlike the planktonic cells, FIC index values for the biofilm cells of Af293 and CG261 were far less than 0.5, indicating synergism between AMB (or LAMB) and AlgL, with exception of the Af293 biofilm and the AMB-AlgL combination, for which additivity/indifference was observed (FIC index value, 0.75). Although cutoffs of 0.5 and 4 for synergy and antagonism, respectively, have arbitrarily been suggested for two-drug combinations, some researchers used a cutoff of 1 for defining additivity/indifference (33, 38, 39), based on the Loewe theory. According to this, we could also claim synergistic activity for the combination of AMB and AlgL against the biofilm-grown Af293 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Checkerboard analysis of in vitro interactions of AMB and LAMB with AlgL against A. fumigatus isolates

| Strain and agenta | PMIC (μg/ml or U/ml)b |

SMIC (μg/ml or U/ml)b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | Median | Range | |

| Af293 | ||||

| AMB | 0.5 | 0.25–0.5 | 16 | 16–32 |

| LAMB | 0.125 | 0.06–0.125 | 16 | 16–32 |

| AlgL | >40 | >40 | 40 | 40 |

| AMB-AlgL | 0.25/40 (1.5) | 0.25–0.5/40 (1.5–2) | 8/10 (0.75) | 4–8/10 (0.375–0.75) |

| LAMB-AlgL | 0.25/40 (3) | 0.125–0.25/40 (2–3) | 2/10 (0.375) | 2–4/10 (0.312–0.5) |

| CG261 | ||||

| AMB | 0.25 | 0.25–0.5 | 32 | 32–64 |

| LAMB | 0.06 | 0.06–0.125 | 32 | 16–32 |

| AlgL | >40 | >40 | 40 | 40 |

| AMB-AlgL | 0.25/40 (2) | 0.25–0.5/40 (2–3) | 8/10 (0.5) | 4–8/10 (0.312–0.5) |

| LAMB-AlgL | 0.06/40 (2) | 0.06–0.125/40 (2–3) | 2/10 (0.312) | 1–2/10 (0.281–0.312) |

The polyene antifungal agents AMB and LAMB were each tested in combination with the nonantifungal agent AlgL.

The MIC endpoints for planktonic (PMIC) and sessile (SMIC) A. fumigatus cells were determined by the visual CLSI and the XTT-based spectrophotometric methods and were defined as the lowest ICs of polyene (μg/ml) or AlgL (U/ml) at which complete visible growth inhibition or a 90% reduction in fungal metabolism (IC90) was achieved, respectively, compared with the results for the untreated controls (see Materials and Methods for details). The MICs in the combinations are expressed as [AMB]/[AlgL] and [LAMB]/[AlgL]. Data in parentheses are FIC indices.

To date, very few studies have explored the in vitro effects of antifungals in combination with nonantifungal agents against Aspergillus species. In one study, Afeltra et al. (40) found potent synergistic interactions between seven nonantimicrobial membrane-active compounds (e.g., verapamil, fluphenazine) and itraconazole against clinical isolates of A. fumigatus resistant to itraconazole, but unfortunately, no evaluations were conducted on biofilm-grown fungal cells. Thus, and for the first time to our knowledge, the present combination experiments showed synergy against mature biofilms of two A. fumigatus isolates when AMB and LAMB were combined with a nonantifungal agent, AlgL. Although the FIC index assessment could be not fully appropriate in this situation, in which one of the agents is an enzyme with no effect on its own, some conclusions can be drawn. Data emerging from the C. albicans biofilm field demonstrate that AMB, facilitated by the amphiphilic nature, physically binds to β-1,3-glucans, a structural component of the fungal cell wall as well as the C. albicans biofilm ECM (41), and such a drug-sequestering ECM might hamper the polyene from reaching biofilm cells. So, it is plausible that the lowering of antifungal MICs for A. fumigatus biofilms in the presence of AlgL detected here could be ascribed to a nonspecific degradation of the ECM by the enzyme, thus enabling both AMB and LAMB to exert their antifungal action. Also, as no antagonism was observed, this emphasizes the potential clinical importance of combining traditional antifungal agents with AlgL, provided that the range of safely achievable concentrations of AlgL is encompassed within the range of concentrations that were found in the present study to contribute to synergy.

Time-kill studies.

To validate the results of the checkerboard microdilution analysis, preformed biofilms of A. fumigatus Af293 and CG261 were challenged with AMB and LAMB (at 0.5×, 1×, and 2× SMICs), alone or combined with defined concentrations of AlgL (1 and 10 U/ml), in order to monitor cell viability (i.e., the OD) versus time using the XTT assay, which measures the aforementioned fungal biomass-associated metabolic activity (31). As it was expected (13, 18), the effects of polyenes against A. fumigatus cells in biofilms were rapid, with the Af293 isolate exhibiting after 4 h of drug challenge 30.7% and 39.4% OD reductions at the lowest (8 μg/ml) and highest (32 μg/ml) concentrations of AMB, respectively. Notably, more pronounced effects were seen with LAMB, with which 38.5% and 59.7% OD reduction rates were achieved after 4 h of drug challenge (8 and 32 μg/ml, respectively) for the Af293 isolate (Fig. 1). Similar percentages were observed for the other isolate studied, CG261, but at more delayed times (8 h) of antifungal drug exposure (Fig. 2). However, >95% of the reduction in metabolic activity was obtained with Af293 at the highest concentrations (32 μg/ml for AMB and 16 μg/ml for LAMB), and there was still 10% activity 24 h after challenging CG261 with 32 μg/ml of both AMB and LAMB (Fig. 1 and 2), in agreement with previous studies (6, 13, 18). Conversely, AlgL did not affect the time-kill curve of A. fumigatus Af293 and CG261 biofilms challenged with 1 U/ml of the compound, while a minimal reduction in metabolic activity over the 24-h period was shown following exposure to 10 U/ml AlgL, with a maximal 26% metabolism reduction displayed after 24 h (Fig. 1 and 2). Interestingly, compared with the results obtained with the antifungal drugs alone, the combinations AMB-AlgL and LAMB-AlgL all consistently decreased the numbers of viable biofilm-associated fungal cells relative to those for the untreated controls. In particular, the combination AMB-AlgL (8 μg/ml and 10 U/ml) resulted in a reduction of percent viability that ranged from 44 (18.2% activity for the combination compared to 62.2% activity for the antifungal alone) at 8 h to 26.3 (4.7% activity for the combination compared to 31.3% activity for the antifungal alone) at 24 h for Af293 and from 29.5 (37.9% activity for the combination compared to 67.4% activity for the antifungal alone) at 8 h to 40.6 (4.7% activity for the combination compared to 39.9% activity for the antifungal alone) at 24 h for CG261. Similar results were obtained with the LAMB-AlgL (8 μg/ml and 10 U/ml) combination.

Fig 1.

Time-kill curves of AlgL (1 and 10 U/ml) alone and in combination with AMB or LAMB at 8 μg/ml (A), 16 μg/ml (B), or 32 μg/ml (C) against biofilm cells of the A. fumigatus type strain Af293. The results are the averages of three replicates carried out on two separate occasions and are expressed as percent cellular viability determined by the XTT reduction assay. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

Fig 2.

Time-kill curves of AlgL (1 and 10 U/ml) alone and in combination with AMB or LAMB at 8 μg/ml (A), 16 μg/ml (B), or 32 μg/ml (C) against biofilm cells of a clinical A. fumigatus isolate (CG261). The results are the averages of three replicates carried out on two separate occasions and are expressed as percent cellular viability determined by the XTT reduction assay. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means.

Overall, these findings revealed that AlgL strikingly enhanced the antibiofilm effects of AMB and LAMB against A. fumigatus, especially for the Af293 isolate; in addition, they show that both AMB formulations reduced the metabolic activity of A. fumigatus sessile cells within a few hours of exposure, but the concentrations needed to initiate these effects were high and are not achievable in humans (42). As the toxicity of AMB is its major clinical drawback, despite some mitigation by the lipid-based formulations that have been developed (16), an antibiofilm-antifungal agent combination might indeed reduce the polyene dose required for therapy.

AFM studies.

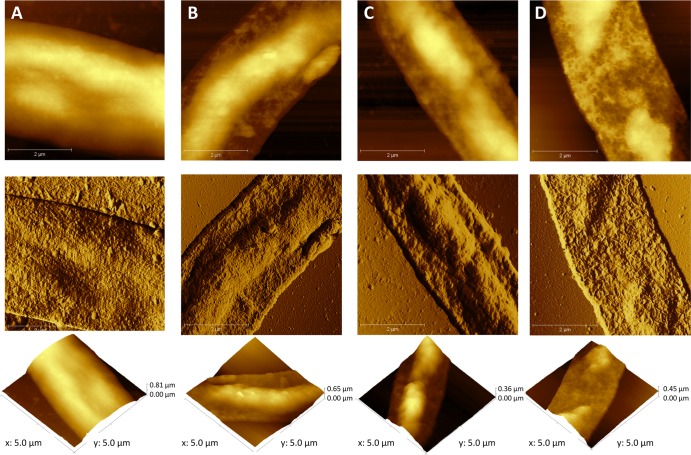

We carried out an AFM study involving imaging and force measurements, in order to examine the ultrastructural effects of AlgL when tested in combination with AMB or LAMB on glass-formed A. fumigatus Af293 biofilms. Therefore, five treatment groups were studied: (i) AlgL at 10 U/ml (AlgL-10), (ii) AMB at 4 μg/ml (AMB-4), (iii) LAMB at 4 μg/ml (LAMB-4), (iv) AMB-4 plus AlgL-10, and (v) LAMB-4 plus AlgL-10. Representative AFM images of biofilm-embedded hyphae scanned in air are shown in Fig. 3. Treated hyphae exhibited little variation in morphology compared with the morphology of those that were untreated, in spite of differences in their texture features. As exemplified in Fig. 3 (bottom), decreases of height compared to the height of untreated biofilms (control samples) were noted when the Af293 biofilms were treated with AlgL alone and in combination with AMB or LAMB (samples from groups i, iv, and v). Similar differences in height images were detectable between the biofilms treated with AMB or LAMB alone (samples from groups ii and iii) and the untreated ones (data not shown). As presented in Fig. 4A, plots of overall height data from all five treatment groups showed that such differences reached statistical significance (P < 0.001), as was also the case for the differences observed when biofilms treated with AlgL or antifungal alone (samples from group i, ii, or iii) were compared to biofilms treated with the AlgL and antifungal drug combination (samples from group iv or v). Interestingly, although there was a significant (P < 0.01) difference between AMB and LAMB in their effects on hyphae, the presence of AlgL sustained such a difference, while significantly (P < 0.01) improving the antihyphal activity of both AMB and LAMB compared with that of each antifungal alone. As attested to by the force-distance curve measurements, we hence found that the amount of adhesive forces was significantly increased for all Af293 biofilms treated with AlgL (P < 0.01) or antifungal drugs (AMB or LAMB; P < 0.05), as well as with the AlgL and antifungal drug (AMB or LAMB) combinations (P < 0.001), compared to that for untreated biofilms (Fig. 4B). However, noticeable increases were especially seen for samples from treatment groups i (AlgL alone), iv (AlgL plus AMB), and v (AlgL plus LAMB). Once again, AlgL significantly potentiated the AMB (P < 0.05) and LAMB (P < 0.01) effects, and this finding was markedly evidenced for LAMB rather than for AMB, despite a slight difference between the antifungal drugs when used alone that favored LAMB, but not significantly (Fig. 4B).

Fig 3.

Atomic force micrographs of mature A. fumigatus Af293 biofilms imaged before treatment (A) and after treatment with AlgL (B), AlgL-AMB (C), or AlgL-LAMB (D). Topographic images (top) show hyphae from each experimental condition, as indicated, after they were grown as sessile cells for 24 h at 37°C in static and aerial environments. Deflection images (middle) reveal more details in hyphal cell texture, whereas three-dimensional (3-D) topographic images (bottom) depict clear differences in hyphal thickness between treated (B to D) and untreated control (A) samples.

Fig 4.

Biophysical properties of untreated 24-h-old A. fumigatus Af293 biofilms in RPMI 1640 medium and of biofilms treated for a further 24 h with AlgL or a polyene antifungal (AMB or LAMB) alone and with the AlgL-antifungal combinations, as measured by AFM. Averages of hyphal height (A) and adhesion force (B) measurements from three independent experiments are shown. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). NS, no significance (P > 0.05). Error bars indicate the standard errors of the measurements.

Consistent with our prior assumption (34), these results suggest that the loss of hydrophobicity subsequent to enzymatic treatment diminishes the entrapment of AMB (and LAMB) in the ECM, thus accounting for the enhanced reduction of hyphal thickness in Af293 biofilms treated with the AlgL-antifungal combination.

Conclusions.

Despite many available antifungal drugs (43), there is yet no optimal therapy for invasive aspergillosis, and this has prompted many clinicians to utilize a combination antifungal approach to improve outcomes (44). In such a context, combined use of a conventional antifungal with AlgL may provide an effective therapeutic approach, although no experiment addressed the activity or longevity of the enzyme under our assay conditions. If AlgL is short-lived, repeated applications at lower concentrations might be significantly better than single higher doses. In a clinical setting, AlgL can be administered as an injectable alginate-dissolving solution with minimal toxicity in vivo for the controlled release of the therapeutic agent (http://www.faqs.org/patents/app/20100080788). The concentrations required and the implications of AlgL in experimental invasive aspergillosis have yet to be determined, and further in vitro studies are needed to test the ability of AlgL to prevent biofilm formation. However, by interfering with the A. fumigatus biofilm matrix, it is possible that AlgL maximized the efficacy of both AMB and LAMB, although we did not specifically evaluate this hypothesis. Testing of a second antifungal in a different class in parallel would certainly have strengthened our observations, but our observations per se reinforce the idea of the importance of the biofilm matrix in antifungal resistance, pointing to the use of EPS-degrading enzymes as a promising strategy to improve the management of biofilm-associated infections.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Fondi Linea D1, 2011) and Gilead Sciences Inc.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 December 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01875-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. O'Toole G, Kaplan HB, Kolter R. 2000. Biofilm formation as microbial development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:49–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dagenais TR, Keller NP. 2009. Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in invasive aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22:447–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ramage G, Rajendran R, Gutierrez-Correa M, Jones B, Williams C. 2011. Aspergillus biofilms: clinical and industrial significance. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 324:89–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beauvais A, Schmidt C, Guadagnini S, Roux P, Perret E, Henry C, Paris S, Mallet A, Prévost MC, Latgé JP. 2007. An extracellular matrix glues together the aerial-grown hyphae of Aspergillus fumigatus. Cell. Microbiol. 9:1588–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Loussert C, Schmitt C, Prevost MC, Balloy V, Fadel E, Philippe B, Kauffmann-Lacroix C, Latgé JP, Beauvais A. 2010. In vivo biofilm composition of Aspergillus fumigatus. Cell. Microbiol. 12:405–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mowat E, Butcher J, Lang S, Williams C, Ramage G. 2007. Development of a simple model for studying the effects of antifungal agents on multicellular communities of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:1205–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Müller FM, Seidler M, Beauvais A. 2011. Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms in the clinical setting. Med. Mycol. 49(Suppl 1):S96–S100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ramage G, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Lopez-Ribot J. 2009. Our current understanding of fungal biofilms. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 35:340–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Seidler MJ, Salvenmoser S, Müller FM. 2008. Aspergillus fumigatus forms biofilms with reduced antifungal drug susceptibility on bronchial epithelial cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4130–4136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Donlan RM, Costerton JW. 2002. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:167–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. 2004. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:95–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fiori B, Posteraro B, Torelli R, Tumbarello M, Perlin DS, Fadda G, Sanguinetti M. 2011. In vitro activities of anidulafungin and other antifungal agents against biofilms formed by clinical isolates of different Candida and Aspergillus species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3031–3035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mowat E, Lang S, Williams C, McCulloch E, Jones B, Ramage G. 2008. Phase-dependent antifungal activity against Aspergillus fumigatus developing multicellular filamentous biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62:1281–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ramage G, Rajendran R, Sherry L, Williams C. 2012. Fungal biofilm resistance. Int. J. Microbiol. 2012:528521 doi:10.1155/2012/528521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Segal BH, Almyroudis NG, Battiwalla M, Herbrecht R, Perfect JR, Walsh TJ, Wingard JR. 2007. Prevention and early treatment of invasive fungal infection in patients with cancer and neutropenia and in stem cell transplant recipients in the era of newer broad-spectrum antifungal agents and diagnostic adjuncts. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:402–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moen MD, Lyseng-Williamson KA, Scott LJ. 2009. Liposomal amphotericin B: a review of its use as empirical therapy in febrile neutropenia and in the treatment of invasive fungal infections. Drugs 69:361–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Traunmüller F, Popovic M, Konz KH, Smolle-Jüttner FM, Joukhadar C. 2011. Efficacy and safety of current drug therapies for invasive aspergillosis. Pharmacology 88:213–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van de Sande WW, Tavakol M, van Vianen W, Bakker-Woudenberg IA. 2010. The effects of antifungal agents to conidial and hyphal forms of Aspergillus fumigatus. Med. Mycol. 48:48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kuhn DM, George T, Chandra J, Mukherjee PK, Ghannoum MA. 2002. Antifungal susceptibility of Candida biofilms: unique efficacy of amphotericin B lipid formulations and echinocandins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1773–1780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seidler MJ, Salvenmoser S, Müller FM. 2010. Liposomal amphotericin B eradicates Candida albicans biofilm in a continuous catheter flow model. FEMS Yeast Res. 10:492–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alipour M, Suntres ZE, Omri A. 2009. Importance of DNase and alginate lyase for enhancing free and liposome encapsulated aminoglycoside activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:317–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brackman G, Cos P, Maes L, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. 2011. Quorum sensing inhibitors increase the susceptibility of bacterial biofilms to antibiotics in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2655–2661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laniado-Laborín R, Cabrales-Vargas MN. 2009. Amphotericin B: side effects and toxicity. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 26:223–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wong TY, Preston LA, Schiller NL. 2000. Alginate lyase: review of major sources and enzyme characteristics, structure-function analysis, biological roles, and applications. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:289–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alkawash MA, Soothill JS, Schiller NL. 2006. Alginate lyase enhances antibiotic killing of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in biofilms. APMIS 114:131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Konno N, Ishida T, Igarashi K, Fushinobu S, Habu N, Samejima M, Isogai A. 2009. Crystal structure of polysaccharide lyase family 20 endo-beta-1,4-glucuronan lyase from the filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei. FEBS Lett. 583:1323–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wright CJ, Shah MK, Powell LC, Armstrong I. 2010. Application of AFM from microbial cell to biofilm. Scanning 32:134–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pierce CG, Uppuluri P, Tristan AR, Wormley FL, Jr, Mowat E, Ramage G, Lopez-Ribot JL. 2008. A simple and reproducible 96-well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. Nat. Protoc. 3:1494–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Colozza C, Posteraro B, Santilli S, De Carolis E, Sanguinetti M, Girmenia C. 2012. In vitro activities of amphotericin B and AmBisome against Aspergillus isolates recovered from Italian patients treated for haematological malignancies. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 39:440–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. Approved standard, 2nd ed M38-A2 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meletiadis J, Mouton JW, Meis JF, Bouman BA, Donnelly JP, Verweij PE. 2001. Colorimetric assay for antifungal susceptibility testing of Aspergillus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3402–3408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meletiadis J, Mouton JW, Meis JF, Verweij PE. 2003. In vitro drug interaction modeling of combinations of azoles with terbinafine against clinical Scedosporium prolificans isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:106–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meletiadis J, Pournaras S, Roilides E, Walsh TJ. 2010. Defining fractional inhibitory concentration index cutoffs for additive interactions based on self-drug additive combinations, Monte Carlo simulation analysis, and in vitro-in vivo correlation data for antifungal drug combinations against Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:602–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Papi M, Maiorana A, Bugli F, Torelli R, Posteraro B, Maulucci G, De Spirito M, Sanguinetti M. 2012. Detection of biofilm-grown Aspergillus fumigatus by means of atomic force spectroscopy: ultrastructural effects of alginate lyase. Microsc. Microanal. 18:1088–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Johnson MD, MacDougall C, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Perfect JR, Rex JH. 2004. Combination antifungal therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:693–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Odds FC. 2003. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhou Y, Wang G, Li Y, Liu Y, Song Y, Zheng W, Zhang N, Hu X, Yan S, Jia J. 2012. In vitro interactions between aspirin and amphotericin B against planktonic cells and biofilm cells of Candida albicans and C. parapsilosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:3250–3260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Demchok JP, Meletiadis J, Roilides E, Walsh TJ. 2010. Comparative pharmacodynamic interaction analysis of triple combinations of caspofungin and voriconazole or ravuconazole with subinhibitory concentrations of amphotericin B against Aspergillus spp. Mycoses 53:239–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O'Shaughnessy EM, Meletiadis J, Stergiopoulou T, Demchok JP, Walsh TJ. 2006. Antifungal interactions within the triple combination of amphotericin B, caspofungin and voriconazole against Aspergillus species. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:1168–1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Afeltra J, Vitale RG, Mouton JW, Verweij PE. 2004. Potent synergistic in vitro interaction between nonantimicrobial membrane-active compounds and itraconazole against clinical isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus resistant to itraconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1335–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vediyappan G, Rossignol T, d'Enfert C. 2010. Interaction of Candida albicans biofilms with antifungals: transcriptional response and binding of antifungals to beta-glucans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2096–2111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bekersky I, Fielding RM, Dressler DE, Lee JW, Buell DN, Walsh TJ. 2002. Pharmacokinetics, excretion, and mass balance of liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) and amphotericin B deoxycholate in humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:828–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Walsh TJ, Anaissie EJ, Denning DW, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Segal BH, Steinbach WJ, Stevens DA, van Burik JA, Wingard JR, Patterson TF, Infectious Diseases Society of America 2008. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:327–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Steinbach WJ, Juvvadi PR, Fortwendel JR, Rogg LE. 2011. Newer combination antifungal therapies for invasive aspergillosis. Med. Mycol. 49(Suppl 1):S77–S81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.