Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia is associated with high hospital mortality. Empirical combination therapy is commonly used to increase the likelihood of appropriate therapy, but the benefits of employing >1 active agent have yet to be established. The purpose of this study was to compare outcomes of patients receiving appropriate empirical combination versus monotherapy for P. aeruginosa bacteremia. This was a retrospective, multicenter, cohort study of hospitalized adult patients with P. aeruginosa bacteremia from 2002 to 2011. The primary endpoint (30-day mortality) was assessed using multivariate logistic regression, adjusting for underlying confounding variables. Secondary endpoints of hospital mortality and time to mortality were assessed by Fisher's exact test and the Cox proportional hazards model, respectively. A total of 384 patients were analyzed. Thirty-day mortality was higher for patients receiving inappropriate therapy than for those receiving appropriate empirical therapy (43.8% versus 21.5%; P = 0.03). However, there were no statistical differences in 30-day mortality following appropriate empirical combination versus monotherapy after adjusting for baseline APACHE II scores and lengths of hospital stay prior to the onset of bacteremia (P = 0.55). Observed hospital mortality was 36.6% for patients administered combination therapy, compared with 28.7% for monotherapy patients (P = 0.17). After adjusting for baseline APACHE II scores, the relationship between time to mortality and combination therapy was not statistically significant (P = 0.59). Overall, no significant differences were observed for 30-day mortality, hospital mortality, and time to mortality between combination and monotherapy for P. aeruginosa bacteremia. Empirical combination therapy did not appear to offer an additional benefit, as long as the isolate was susceptible to at least one antimicrobial agent.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common pathogen that is implicated in a wide variety of nosocomial infections (1). In particular, P. aeruginosa bacteremia is associated with high mortality. Reported mortality rates exceed 50% in some series and are even higher within certain populations, such as patients with severe underlying comorbid conditions or those who are immunosuppressed (2–5).

P. aeruginosa is intrinsically resistant to many commonly used antimicrobial agents, and resistance has been reported for nearly all known antibiotics (6, 7). In addition, multidrug-resistant (MDR) P. aeruginosa strains are increasing in prevalence and are associated with higher mortality than multidrug-susceptible strains (8–10). Intrinsic resistance coupled with the increasing prevalence of MDR strains has complicated appropriate empirical antibiotic selection by limiting the number of available active agents. Appropriate empirical antimicrobial selection is crucial to the management of severe pseudomonal infections.

The notion of using combination therapy for P. aeruginosa bacteremia was first established by a prospective multicenter study by Hilf and colleagues in 1989 (11). They demonstrated a significant mortality benefit for patients who received combination therapy (47% versus 23%; P = 0.023). However, in 2004, this idea was challenged by a meta-analysis comparing beta-lactam monotherapy versus beta-lactam in combination with an aminoglycoside for immunocompetent septic patients (12), which was in favor of monotherapy. Due to the small number of P. aeruginosa bacteremia cases included in the analysis and the lack of randomized clinical trials, convincing clinical data are sparse, and controversy still exists (13, 14).

In contrast, the importance of appropriate empirical therapy for P. aeruginosa bacteremia with regard to mortality reduction has been established previously (4, 15, 16). In order to increase the likelihood of achieving appropriate therapy, combination antimicrobial therapy is often used empirically (2, 17–21). Even though combination therapy does not appear to be associated with improved outcomes once susceptibilities are known (22), it is still not established whether the number of appropriate empirical antimicrobial agents affects patient outcomes. The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of appropriate empirical combination therapy (>1 active agent) versus monotherapy for patients with P. aeruginosa bacteremia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and sites.

This was an international, multicenter, retrospective cohort study of hospitalized patients with P. aeruginosa bacteremia from 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2011. The study was conducted at St. Luke's Episcopal Hospital (a 900-bed acute care teaching hospital in Houston, TX), Singapore General Hospital (a 1,600-bed acute care teaching hospital in Singapore, Singapore), and Tan Tock Seng Hospital (a 1,400-bed general care hospital in Singapore, Singapore). The institutional review board of each hospital approved the study. Subject informed consent was not mandated due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Study subjects.

All patients older than 18 years of age and with a positive blood culture for P. aeruginosa, and who were hospitalized for at least 48 h after the index culture was obtained, were considered eligible. Patients were identified using each institution's clinical microbiology database. Patients with polymicrobial bacteremia were excluded. Subsequent positive blood cultures of P. aeruginosa obtained within 30 days of the index blood culture were considered part of the same bacteremic episode and were excluded from the analysis.

Data collection.

Pertinent demographic and clinical data were collected from electronic medical records for all patients. Variables collected included age, gender, ethnicity, length of hospital stay prior to the index blood culture, length of hospital stay associated with blood culture (from index blood culture to hospital discharge date), empirical treatment, and in vitro susceptibility results for the organism. Additionally, comorbidities such as cardiovascular and respiratory disorders, renal and liver dysfunction, central nervous system disease (cerebrospinal fluid leak and stroke), diabetes mellitus, and immunosuppression (HIV infection, chemotherapy, chronic steroid use equivalent to ≥10 mg prednisone daily for ≥1 month, or solid-organ transplantation) were collected. The source of bacteremia was determined by documented positive cultures of P. aeruginosa with the same in vitro susceptibilities within 72 h of the index culture. The acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE II) score was collected for all patients, within 24 h of the index blood culture, to assess the infection-related severity of illness. The primary endpoint was 30-day mortality, starting from the date of the index culture. Patients who were discharged prior to the 30-day point were considered alive unless proven otherwise. Secondary endpoints were hospital mortality and time to mortality. Time to mortality was observed directly if the patients died. For patients who were discharged, they were alive at least until the date of discharge and therefore were handled as censored data.

Definitions.

Appropriate empirical antibiotic therapy was defined as administration within 24 h of index blood culture of an antipseudomonal antimicrobial agent to which the isolate was susceptible on the final susceptibility report. Susceptibility interpretations were based on the published Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoints for that period, as reported by the microbiology laboratory. Appropriate empirical combination therapy was defined as administration of more than one appropriate antimicrobial agent. It was considered monotherapy if a patient was given two antipseudomonal agents but only one agent was appropriate. Selection of antimicrobial therapy was left to the discretion of the attending physician at each institution.

Sample size determination (power analysis).

For the primary analysis, an alpha level of 0.05 and a beta level of 0.15 were used. Based on a published 30-day mortality rate of 28% (23), a reduction to 10% mortality with appropriate empirical combination therapy was deemed clinically significant. Therefore, a delta level of 18% was used. It was anticipated that more patients would receive appropriate empirical monotherapy than combination therapy, and a 3:1 ratio was utilized. A sample size of 195 monotherapy and 65 combination therapy patients would thus be needed.

Statistical methods.

Clinical outcomes for patients receiving appropriate empirical combination therapy were compared to those for patients given appropriate empirical monotherapy. The Student t test or the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared by Fisher's exact test. Potential confounding of the primary endpoint was adjusted using multivariate logistic regression. Time to mortality was assessed using the Cox proportional hazards model; times were compared using the length of stay associated with the index culture, censored by hospital mortality and stratified by empirical (combination or mono-) therapy. Univariate analyses for logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine the odds ratio (OR) or hazards ratio (HR) for different variables, with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Covariates with P values of <0.2 by univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis, utilizing a backward-selection process. P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant, and all tests were two tailed. All statistical analyses were performed using SYSTAT, version 12 (SYSTAT Software, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Study subjects and outcomes.

A total of 384 patients were examined during the study period. Sixteen patients (4.2%) received inappropriate therapy, while the remaining 368 patients (95.8%) received appropriate therapy. Thirty-day mortality was significantly higher (43.8% versus 21.5%; P = 0.03) in patients who received inappropriate therapy, providing background validity to the study.

Of the 368 patients given appropriate therapy, 211 (57.3%) were male; the mean age (± standard deviation [SD]) was 61.7 years (±15.3 years), and the mean APACHE II score was 13.6 (±6.6). One hundred fifty-five patients were Caucasian, 95 were African American, 70 were Asian, and 43 were Hispanic. Eighty-two patients received empirical combination therapy, and 286 patients received empirical monotherapy. There were no statistical differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups (Table 1). The mean APACHE II score was 13.5 (±6.3) with monotherapy and 13.9 (±7.3) with combination therapy (P = 0.92 by the Kruskal-Wallis test).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Variable | Monotherapy | Combination therapy | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of males | 171 (60) | 40 (50) | 0.08 |

| Mean age (yr) ± SD | 62.2 ± 15.4 | 59.8 ± 14.9 | 0.31 |

| Mean infection-related APACHE II score ± SD | 13.5 ± 6.3 | 13.9 ± 7.3 | 0.92 |

| Mean length of stay prior to culture (days) ± SD | 20 ± 37 | 15 ± 20 | 0.76 |

| No. (%) of comorbidities | |||

| Cardiovascular conditions | 214 (80) | 61 (77) | 0.63 |

| Respiratory conditions | 37 (14) | 10 (13) | 0.71 |

| Central nervous system disease | 36 (13) | 9 (11) | 0.70 |

| Renal disease | 95 (36) | 36 (46) | 0.12 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 91 (34) | 25 (32) | 0.69 |

| Immunosuppression | 74 (28) | 26 (33) | 0.40 |

| Liver disease | 30 (11) | 14 (18) | 0.08 |

| No. (%) of cases with source of bacteremia | |||

| Line | 51 (19) | 12 (15) | 0.41 |

| Lung | 48 (18) | 20 (25) | 0.51 |

| Urine | 59 (22) | 10 (13) | 0.54 |

| Wound | 34 (13) | 13 (16) | 0.45 |

| Unknown | 54 (20) | 21 (27) | 0.22 |

The most common combination of antimicrobials administered was an antipseudomonal beta-lactam with an aminoglycoside (n = 33). In general, cefepime was the most frequently administered antipseudomonal beta-lactam (n = 40) for patients who received combination therapy, followed by piperacillin-tazobactam (n = 26) and meropenem (n = 20). Tobramycin was the aminoglycoside that was used most frequently in combination therapy (n = 15).

Thirty-day mortality was 23.2% for patients given combination therapy, compared to 20.0% for the monotherapy group (P = 0.24). Independent risk factors associated with 30-day mortality were the infection-related APACHE II score and the length of hospital stay prior to the onset of bacteremia (Table 2). After adjusting for these variables, there was still no significant difference between combination and monotherapy (OR = 1.21; 95% CI = 0.62 to 2.28; P = 0.55). There was also no statistically significant difference in 30-day mortality for patients with concurrent vasopressor therapy and combination or monotherapy (36.6% versus 30.7%; P = 0.64). Subgroup analyses revealed that the lack of difference in primary endpoint could not be attributed to the period of enrollment or the country of patient origin (data not shown).

Table 2.

Risk factor analysis of 30-day mortality

| Variable | Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.24 | ||

| Male gender | 1.28 (0.77–2.13) | 0.34 | ||

| Combination therapy | 1.14 (0.63–2.04) | 0.67 | ||

| Length of stay prior to culture | 1.01 (1.00–1.01) | 0.01 | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.01 |

| Infection-related APACHE II score | 1.10 (1.07–1.15) | <0.01 | 1.12 (1.08–1.17) | <0.01 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Cardiovascular conditions | 0.41 (0.23–0.73) | <0.01 | ||

| Respiratory conditions | 1.46 (0.73–2.94) | 0.29 | ||

| Central nervous system disease | 0.63 (0.27–1.48) | 0.29 | ||

| Renal disease | 1.21 (0.72–2.03) | 0.48 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.51 (0.85–2.67) | 0.16 | ||

| Immunosuppression | 0.80 (0.45–1.42) | 0.44 | ||

| Liver disease | 2.09 (1.05–4.14) | 0.04 | ||

| Source of bacteremia | ||||

| Line | 0.63 (0.31–1.31) | 0.22 | ||

| Lung | 1.54 (0.84–2.82) | 0.16 | ||

| Urine | 0.55 (0.27–1.14) | 0.11 | ||

| Wound | 0.97 (0.46–2.06) | 0.94 | ||

| Abdomen | 1.75 (0.86–3.56) | 0.12 | ||

| Unknown | 0.97 (0.52–1.82) | 0.94 | ||

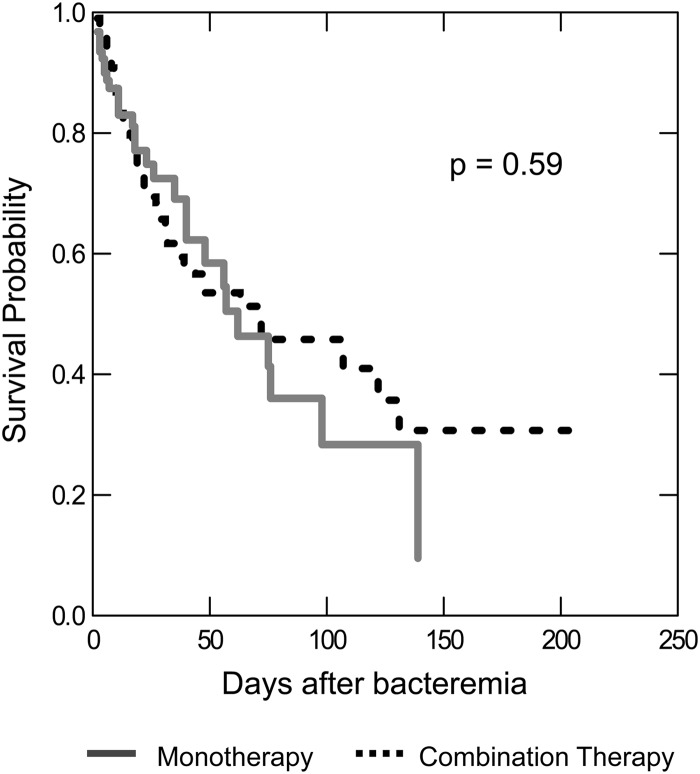

The overall hospital mortality rate among appropriately treated patients was 30.4%. Observed hospital mortality was 36.6% for patients administered combination therapy, compared with 28.7% for the monotherapy group (P = 0.17). The infection-related APACHE II score was the only variable identified to be associated with survival over time (HR = 1.05; 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.08; P < 0.001). After adjusting for infection-related APACHE II scores, the relationship between times to mortality with combination and monotherapy was not statistically significant (P = 0.59) (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Comparison of times to mortality.

DISCUSSION

This international, multicenter study sought to determine differences in mortality between appropriate empirical combination and monotherapy for patients with P. aeruginosa bacteremia. The results of our study suggest that there are no differences between 30-day mortality, hospital mortality, or time to mortality between appropriate empirical combination and monotherapy, even after adjusting for confounding variables.

To put the study into proper clinical perspective, a few patients given inappropriate empirical therapy were included. Although it was not the main focus of the study, we demonstrated that patients with inappropriate empirical therapy for P. aeruginosa bacteremia had higher mortality, which agreed with the findings of previous studies and further highlighted the importance of proper antibiotic selection (20, 23).

Often, patients with a higher severity of illness receive therapy with multiple agents due to an increased risk of mortality (24). In our study, there were no differences in infection-related severity of illness between patients who received combination and monotherapy. Often, empirical antimicrobial agents are chosen based on the probability of the patient being infected with an MDR organism (25), based on variables such as length of hospitalization and comorbid conditions. Patients infected with MDR organisms are more likely to be treated with inappropriate therapy (10) and therefore may be given empirical combination therapy to increase the likelihood of achieving appropriate therapy. While isolation of an MDR organism was not specifically examined, there were no differences found in the length of hospital stay prior to index blood culture, comorbidities, or source of bacteremia between patients who received combination and monotherapy.

We also evaluated the risk factors independently associated with 30-day mortality and adjusted for confounding variables. The infection-related APACHE II score as well as the length of hospital stay prior to blood culture was independently associated with 30-day mortality. However, after adjusting for these variables in the multivariate analysis, there was no difference in 30-day mortality between combination and monotherapy. Using the Cox proportional hazards model, we also found that the infection-related APACHE II score was associated with survival over time. After adjusting for the APACHE II score in the multivariate analysis, there was no difference in survival over time between combination and monotherapy.

There are studies that examine combination therapy as empirical therapy, but not necessarily appropriate empirical combination therapy. Some studies have demonstrated a lack of benefit with combination therapy as definitive therapy (20, 22). A recent study of definitive therapy with beta-lactam monotherapy or combination therapy with a beta-lactam plus an aminoglycoside or fluoroquinolone reported an uncertain benefit for P. aeruginosa bacteremia (26). Our study is unique in that it is the largest study to date powered to examine whether the number of appropriate empirical agents, not just appropriate empirical therapy, affects outcomes. The results of our study can be adopted in routine antimicrobial stewardship practice.

There are several limitations of this study. First, we used a retrospective, observational study design. We were unable to stratify patients based on the source of bacteremia or to control for prescribing practice for antimicrobials. Second, we looked at only the first 48 h of empirical therapy; observing a longer duration of therapy may have influenced the outcomes. Third, our definition of appropriate therapy included any agent administered that had in vitro susceptibility to the isolate. In some cases, patients were administered two agents, but the only appropriate agent was an aminoglycoside, therefore constituting functional aminoglycoside monotherapy. Aminoglycoside monotherapy was considered inappropriate therapy in previous studies (15, 22). Fourth, synergy could be observed between an active and an inactive agent (defined as functionally appropriate monotherapy), as well as with 2 inactive agents combined (defined as inappropriate therapy). However, our study was not designed to address these intricacies. Lastly, we did not stratify patients with MDR strains. Isolation of an MDR strain is an independent risk factor for 30-day mortality (24) and may have been a confounding variable in our study.

In summary, this study suggests that there is no difference in mortality outcomes associated with the number of appropriate agents administered during initial empirical therapy for P. aeruginosa bacteremia, as long as at least one agent is active. Achieving appropriate empirical therapy plays an important role in improving patient outcomes with P. aeruginosa bacteremia. Due to the wide variation in isolate susceptibilities at different institutions, we suggest that empirical antimicrobial therapy be guided by pathogen susceptibilities at a specific institution and treatment strategies adopted to achieve appropriate therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Cristina B. Villamor for technical assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 December 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System 2004. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am. J. Infect. Control 32:470–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bodey GP, Jadeja L, Elting L. 1985. Pseudomonas bacteremia. Retrospective analysis of 410 episodes. Arch. Intern. Med. 145:1621–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chatzinikolaou I, Abi-Said D, Bodey GP, Rolston KV, Tarrand JJ, Samonis G. 2000. Recent experience with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia in patients with cancer: retrospective analysis of 245 episodes. Arch. Intern. Med. 160:501–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kang CI, Kim SH, Park WB, Lee KD, Kim HB, Kim EC, Oh MD, Choe KW. 2005. Bloodstream infections caused by antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacilli: risk factors for mortality and impact of inappropriate initial antimicrobial therapy on outcome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:760–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kuikka A, Valtonen VV. 1998. Factors associated with improved outcome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia in a Finnish university hospital. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17:701–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bonomo RA, Szabo D. 2006. Mechanisms of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter species and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43(Suppl 2):S49–S56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tam VH, Chang KT, Abdelraouf K, Brioso CG, Ameka M, McCaskey LA, Weston JS, Caeiro JP, Garey KW. 2010. Prevalence, resistance mechanisms, and susceptibility of multidrug-resistant bloodstream isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1160–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morata L, Cobos-Trigueros N, Martinez JA, Soriano A, Almela M, Marco F, Sterzik H, Nunez R, Hernandez C, Mensa J. 2012. Influence of multidrug resistance and appropriate empirical therapy on Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia 30-day mortality. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:4833–4837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Obritsch MD, Fish DN, MacLaren R, Jung R. 2005. Nosocomial infections due to multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: epidemiology and treatment options. Pharmacotherapy 25:1353–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tam VH, Rogers CA, Chang KT, Weston JS, Caeiro JP, Garey KW. 2010. Impact of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia on patient outcomes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3717–3722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hilf M, Yu VL, Sharp J, Zuravleff JJ, Korvick JA, Muder RR. 1989. Antibiotic therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: outcome correlations in a prospective study of 200 patients. Am. J. Med. 87:540–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paul M, Benuri-Silbiger I, Soares-Weiser K, Leibovici L. 2004. Beta lactam monotherapy versus beta lactam-aminoglycoside combination therapy for sepsis in immunocompetent patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 328:668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paul M, Leibovici L. 2005. Combination antibiotic therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemia. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5:192–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Safdar N, Handelsman J, Maki DG. 2004. Does combination antimicrobial therapy reduce mortality in Gram-negative bacteraemia? A meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4:519–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lodise TP, Jr, Patel N, Kwa A, Graves J, Furuno JP, Graffunder E, Lomaestro B, McGregor JC. 2007. Predictors of 30-day mortality among patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections: impact of delayed appropriate antibiotic selection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3510–3515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osih RB, McGregor JC, Rich SE, Moore AC, Furuno JP, Perencevich EN, Harris AD. 2007. Impact of empiric antibiotic therapy on outcomes in patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:839–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bhat SV, Peleg AY, Lodise TP, Jr, Shutt KA, Capitano B, Potoski BA, Paterson DL. 2007. Failure of current cefepime breakpoints to predict clinical outcomes of bacteremia caused by Gram-negative organisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4390–4395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bryan CS, Reynolds KL, Brenner ER. 1983. Analysis of 1,186 episodes of Gram-negative bacteremia in non-university hospitals: the effects of antimicrobial therapy. Rev. Infect. Dis. 5:629–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Geerdes HF, Ziegler D, Lode H, Hund M, Loehr A, Fangmann W, Wagner J. 1992. Septicemia in 980 patients at a university hospital in Berlin: prospective studies during 4 selected years between 1979 and 1989. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:991–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Micek ST, Lloyd AE, Ritchie DJ, Reichley RM, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. 2005. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection: importance of appropriate initial antimicrobial treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1306–1311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vidal F, Mensa J, Almela M, Martinez JA, Marco F, Casals C, Gatell JM, Soriano E, Jimenez de Anta MT. 1996. Epidemiology and outcome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia, with special emphasis on the influence of antibiotic treatment. Analysis of 189 episodes. Arch. Intern. Med. 156:2121–2126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chamot E, Boffi El Amari E, Rohner P, Van Delden C. 2003. Effectiveness of combination antimicrobial therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2756–2764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kang CI, Kim SH, Kim HB, Park SW, Choe YJ, Oh MD, Kim EC, Choe KW. 2003. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: risk factors for mortality and influence of delayed receipt of effective antimicrobial therapy on clinical outcome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37:745–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hirsch EB, Cottreau JM, Chang KT, Caeiro JP, Johnson ML, Tam VH. 2012. A model to predict mortality following Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 72:97–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Niederman MS. 2006. Use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials for the treatment of pneumonia in seriously ill patients: maximizing clinical outcomes and minimizing selection of resistant organisms. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42(Suppl 2):S72–S81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bliziotis IA, Petrosillo N, Michalopoulos A, Samonis G, Falagas ME. 2011. Impact of definitive therapy with beta-lactam monotherapy or combination with an aminoglycoside or a quinolone for Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. PLoS One 6:e26470 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]