Abstract

Comparative analysis of ospC genes from 127 Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto strains collected in European and North American regions where Lyme disease is endemic and where it is not endemic revealed a close relatedness of geographically distinct populations. ospC alleles A, B, and L were detected on both continents in vectors and hosts, including humans. Six ospC alleles, A, B, L, Q, R, and V, were prevalent in Europe; 4 of them were detected in samples of human origin. Ten ospC alleles, A, B, D, E3, F, G, H, H3, I3, and M, were identified in the far-western United States. Four ospC alleles, B, G, H, and L, were abundant in the southeastern United States. Here we present the first expanded analysis of ospC alleles of B. burgdorferi strains from the southeastern United States with respect to their relatedness to strains from other North American and European localities. We demonstrate that ospC genotypes commonly associated with human Lyme disease in European and North American regions where the disease is endemic were detected in B. burgdorferi strains isolated from the non-human-biting tick Ixodes affinis and rodent hosts in the southeastern United States. We discovered that some ospC alleles previously known only from Europe are widely distributed in the southeastern United States, a finding that confirms the hypothesis of transoceanic migration of Borrelia species.

INTRODUCTION

Establishment of Borrelia sp. populations in different geographic regions is determined by natural factors (1). The maintenance of spirochete species in nature depends upon the relative abundances of their reservoir hosts and vector ticks and the intensity of host-vector interactions (2). The worldwide distribution of spirochetes from the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex, some of which cause Lyme disease (LD), is facilitated by the long-distance dispersal of infected ticks by migrating hosts (3–5). A hypothesis for the migration route of Borrelia spp. between continents was proposed, and the first evidence of transoceanic dispersal of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto was presented almost 15 years ago (6–9).

B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is the primary, but not the only, species that causes LD around the world (10–13). Different strains of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto exhibit considerable genetic heterogeneity locally as well as globally. Also, molecular analyses revealed a close relationship and an overlapping of genotypes between European and North American spirochete populations, which confirms the transoceanic migration hypothesis and the existence of recombinant genotypes (6, 9). Multiple genotypes of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto have been identified based on the analysis of a spirochete gene (ospC) that encodes highly polymorphic outer surface protein C (14–16). Borrelia OspC antigen is heavily targeted by the host immune system. It establishes the secondary immune response, or immune memory, in hosts (17). Associations between ospC genotypes and invasiveness in patients (18–22) and experimentally infected animals (23, 24) have been reported. The ospC gene is more diverse than any other Borrelia gene studied to date (17). B. burgdorferi sensu stricto has the ability to infect a wide range of phylogenetically diverse vertebrate hosts, which facilitates the further expansion of the spirochete into new geographical areas (25–28). Selection pressure from the vertebrate immune system is likely responsible for the high level of polymorphism of the ospC gene (17, 29–31).

Furthermore, because B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is a host generalist that occurs in birds, rodents, and other mammals, its dispersal potential is considerable. More than 240 animal species have been reported as hosts for tick vectors and potential reservoir hosts of Borrelia in Europe (27). Such a diverse host spectrum may lead to the establishment of new enzootic LD foci in Europe. We believe that the current distribution of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in Europe is much wider than has been reported and is enhanced by the involvement of multiple phylogenetically diverse migratory animal species. Such expansion could affect LD risk and helps to explain the observed increased incidence of LD in humans worldwide.

Previous studies carried out in areas where LD is endemic demonstrated that the vast majority of known ospC alleles are geographically distinct (7, 16, 32, 33). The presence of Borrelia spp. in nature is known to be affected by recent urbanization, an increasing overlap between human and Borrelia habitats, and climate change (9, 34–39). Thus, it is not unexpected that the distributions of Borrelia genotypes may have been shifting in recent decades and may continue to shift. The number of LD cases worldwide has increased recently (40, 41), which may be attributable to Borrelia expansion or to gene transfer that resulted in recombinant genotypes (31).

The objectives of this study were to compare ospC alleles from a southeastern U.S. population of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto with other Borrelia sensu stricto strains from North American and European localities where LD is endemic and where it is not endemic. The search for evidences that support the hypothesis of transoceanic migration of Borrelia species was another aim of our project. Our study was not meant to be a statistical analysis with emphasis on the ranking of Borrelia ospC alleles but rather an invitation to an open discussion to advance the natural history and understanding of the enzootiology of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in the southeastern United States, previously considered to be a “low-or-no” Lyme disease region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Control sequences.

As a control group, 100 B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains with different ospC types were downloaded from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto reference strains used in this study

| ospC type | B. burgdorferi sensu stricto straina | GenBank accession no. | Location | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 132a | DQ437446 | NE USA | Human |

| A | CS1 | DQ437464 | NE USA | I. scapularis |

| A | CS2 | DQ437465 | NE USA | I. scapularis |

| A | CS3 | DQ437466 | NE USA | I. scapularis |

| A | PKa2 | EF537420 | Europe | Human |

| A | IP1 | EF537422 | Europe | Human |

| A | OC1 | AF029860 | New York | Tick |

| A | 132b | DQ437447 | NE USA | Human |

| A | NA | EU482041 | New York | Human |

| A | Ip2 | L42887 | France | Human |

| A | 2-1498 CA4 | L81131 | California | Human |

| A | HII | U91792 | Italy | Human |

| A | IP3 | U91797 | France | Human |

| A | L5 | U91798 | Austria | Human |

| A | IP1 | U91799 | France | Human |

| A | P1F | U91801 | Austria | Human |

| A | PKa | X69589 | Germany | Human |

| A | TXGW | X84783 | Texas | Human |

| A | B31 | U01894 | New York | Unknown |

| B(nt59) | SMT44 | FJ932735 | California | I. pacificus |

| B1 | MI415 | EF537413 | Michigan | P. leucopus |

| B2 | ZS7 | L42868 | Germany | Tick |

| B2 | Lx36 | EF537411 | Europe | Human |

| B | OC2 | AF029861 | New York | Tick |

| B | NA | EU482042 | New York | Human |

| B | 35B808 | U91794 | Germany | Tick |

| B | 61BV3 | U91795 | Germany | Human |

| B | DK7 | X73625 | Denmark | Human |

| B | PBre | X81522 | Germany | Human |

| B | BUR | X84765 | New York | Human |

| C | OC3 | AF029862 | New York | Tick |

| C | JD1 | DQ437462 | NE USA | I. scapularis |

| C | NA | EU482043 | New York | Human |

| D | OC4 | AF029863 | New York | Tick |

| D | NA | EU482044 | New York | Human |

| D | CA-11.2A | L25413 | California | Unknown |

| E3 | HRPW89 | FJ932732 | California | I. pacificus |

| E | OC5 | AF029864 | New York | Tick |

| E | OC7 | AF029866 | New York | Tick |

| E | 88a | DQ437459 | New York | Human |

| E | NA | EU482045 | New York | Human |

| E | 28691 | L42894 | Pennsylvania | I. scapularis |

| E | N40 | U04240 | Connecticut | Rodent |

| F | 27579 | L42896 | Connecticut | I. scapularis |

| F | B. pacificus | X83555 | California | I. pacificus |

| F | OC6 | AF029865 | New York | Tick |

| F | NA | EU482046 | New York | Human |

| F | 2-1498 Son 188 | L81130 | California | Human |

| G | OC8 | AF029867 | New York | Tick |

| G | NA | EU482047 | New York | Human |

| G | 72a | DQ437456 | New York | Human |

| H | OC9 | AF029868 | New York | Tick |

| H | MI411 | EF537400 | Michigan | T. striatus |

| H | NA | EU482048 | New York | Human |

| H3 | MCCP65 | FJ932733 | California | Tick (nymph) |

| I | OC10 | AF029869 | New York | Tick |

| I | 297 | L42893 | Connecticut | Unknown |

| I | HB19 | U04281 | Connecticut | Human |

| I | NA | EU482049 | New York | Human |

| I3 | HPS6 | FJ932734 | California | Tick |

| J | OC11 | AF029870 | New York | Tick |

| J | 118a | DQ437444 | New York | Human |

| J | NA | EU482050 | New York | Human |

| J | MIL | U91802 | Slovakia | I. ricinus |

| K | OC12 | AF029871 | New York | Tick |

| K | OC13 | AF029872 | New York | Tick |

| K | 28354 | L42895 | Maryland | I. scapularis |

| K | 297 | U08284 | Connecticut | Human |

| K | MUL | X84779 | New York | Human |

| K | KIPP | X84782 | New York | Human |

| K | 272 | X84785 | Connecticut | Human |

| K | NA | EU482051 | New York | Human |

| L | Y1 | EF537402 | Europe | I. ricinus |

| L | Bol6 | EF537406 | Europe | I. ricinus |

| L | 21347 | L42899 | Wisconsin | P. leucopus |

| L | T255 | X81524 | Germany | I. ricinus |

| M | NA | EU482052 | New York | Human |

| M | 2591 | U01892 | Connecticut | P. leucopus |

| N | 80a | DQ437457 | New York | Human |

| N | CS8 | DQ437470 | New York | I. scapularis |

| N | MI418 | EF537430 | Michigan | P. leucopus |

| N | NA | EU482053 | New York | Human |

| N | 26815 | L42897 | Connecticut | Chipmunk |

| O | NA | EU482056 | New York | Human |

| O | DUNKIRK | X84778 | New York | Human |

| P | 20006 | U91796 | France | I. ricinus |

| Q | Bol15 | EF537398 | Europe | I. ricinus |

| Q | 212 | U91790 | France | I. ricinus |

| R | Esp1 | U91791 | Spain | I. ricinus |

| R | NE56 | U91800 | Switzerland | I. ricinus |

| S | Bol26 | EF537417 | Europe | I. ricinus |

| S | Z136 | U91793 | Germany | I. ricinus |

| T | NA | EU482054 | New York | Human |

| U | 94a | DQ437460 | New York | Human |

| U | CS5 | DQ437467 | New York | I. scapularis |

| U | NA | EU482055 | New York | Human |

| V | Bol29 | EF537407 | Europe | Human |

| V | Bol30 | EF537408 | Europe | Human |

| W | Ri5 | EF537414 | Finland | I. ricinus |

| X | SV1 | EF537427 | Finland | I. ricinus |

NA, not applicable.

Experimental samples.

The experiment group included 127 samples of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto. The sampling in the presented study was not exhaustive or random for a variety of reasons, as statistical analysis was not a goal of this project. Of these samples, 58 were derived from the vector ticks Ixodes ricinus, I. affinis, I. pacificus, and I. scapularis. For this purpose, each tick was rinsed in 10% bleach for 50 min, followed by a 5-min wash in 70% ethyl alcohol. The cleaned tick was air dried on sterile filter paper, placed into 100 μl of BSK-H medium (a modified Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly medium), and homogenized. All instruments and breakers were autoclaved prior to use. The homogenized mixture was transferred into 5 ml with BSK-H medium, and tubes were maintained at 34°C for 8 weeks. All work was conducted under a sterile biohazard hood.

Another 35 samples originated from the rodents Peromyscus gossypinus, Neotoma floridana, Sigmodon hispidus, Tamias senex, Neotoma fuscipes, and Sciurus griseus. Samples from ear clips were prepared as follows: a triangle cut from the ear was washed in 70% ethyl alcohol for 4 to 5 min. After that, the ear clip was soaked for 4 to 5 min in freshly diluted 10% bleach, followed by a 1-min rinse in 95% ethanol. After 2 min of air drying under sterile conditions, tissue was cut into 3 to 4 pieces and placed into 5 ml of BSK-H medium. Tubes were kept at 34°C for 6 weeks. Spirochete cultures from internal organs were initiated as follows: organs were removed from euthanized animals, placed directly into 200 μl of BSK-H medium, chopped in it, and left at room temperature for 2 to 3 min. After that, 100 μl of the mixture was transferred into 5 ml of BSK-H medium and kept at 34°C for 6 weeks. The remaining 34 samples were of human origin. Fifty-three samples were collected in Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida in the southeastern United States; 25 samples were collected in California in the far-western United States; and 49 samples came from a subset of European countries where LD is endemic, i.e., the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Switzerland (Table 2).

Table 2.

Experiment group of the 127 B. burgdorferi sensu stricto samples derived from vector ticks, rodent hosts, and humans in selected European countries, the southeastern United States, and California and analyzed in this study

| Region studied and ospC typea | Isolateb | GenBank accession no. | Location/yr of collection | Host or vector | DNA isolation source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | |||||

| Q | NE5220 | JQ253799 | Switzerland/2010 | I. ricinus | Spirochete culture |

| L | NE5222 | JQ353800 | Switzerland/2010 | I. ricinus | Spirochete culture |

| V | NE5248 | JQ352801 | Switzerland/2010 | I. ricinus | Spirochete culture |

| R | NE5261 | JQ352802 | Switzerland/2010 | I. ricinus | Spirochete culture |

| B | NE5264 | JQ352803 | Switzerland/2010 | I. ricinus | Spirochete culture |

| L | NE5266 | JQ352804 | Switzerland/2010 | I. ricinus | Spirochete culture |

| R | NE5267 | JQ352805 | Switzerland/2010 | I. ricinus | Spirochete culture |

| L | SKT-2 | AY597021 | Slovakia/2004 | I. ricinus | Spirochete culture |

| B | SKT-9 | AY597028 | Slovakia/2004 | I. ricinus | Spirochete culture |

| L | SLV 1 | JQ236853 | Slovenia/2006 | Human | Spirochete culture |

| B | SLV 2 | JQ236854 | Slovenia/2006 | Human | Spirochete culture |

| R* | S277(+2) | JF754968 | Czech Republic/2010 | I. ricinus | Whole tick |

| R | B4/N39Aug | JF754971 | Germany/2010 | I. ricinus | Whole tick |

| Q** | S1/11(+1) | JF754969 | Czech Republic/2010 | I. ricinus | Whole tick |

| V | H | JQ219681 | Hungary/2000 | Human | Human skin |

| B*** | Brno35(+8) | JQ219682 | Czech Republic/2009 | Human | Serum/joint fluid |

| A | N 12 | JQ219683 | Czech Republic/2008 | Human | Human serum |

| B**** | N103(+20) | JQ219684 | Czech Republic/2010 | Human | Serum/joint fluid |

| USA | |||||

| B | BUL1 | JF723215 | GA/1994 | N. floridana | Spirochete culture |

| G | BUL3 | JF723216 | GA/1994 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| B | BUL4 | JF723217 | GA/1994 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| B | BUL5 | JF723218 | GA/1994 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| B | BUL6 | JF723219 | GA/1994 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| G | BUL8 | JF723220 | GA/1995 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| B | BUL10 | JF723221 | GA/1997 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| H | MI 1 | JF723262 | FL/1992 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| G | SCCH 3 | JF723222 | SC/1995 | I. scapularis | Spirochete culture |

| B | SCCH 9 | JF723223 | SC/1995 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| B | SCCH 13 | JF723224 | SC/1995 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| B | SCCH 19 | JF723226 | SC/1995 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| L | SCCH 24 | JF723228 | SC/1995 | S. hispidus | Spirochete culture |

| G | SCCH 25 | JF723229 | SC/1995 | S. hispidus | Spirochete culture |

| G | SCCH 28 | JF723231 | SC/1995 | S. hispidus | Spirochete culture |

| L | SCCH 30 | JF723232 | SC/1995 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| G | SCCH 31 | JF723233 | SC/1995 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| G | SCGT 4 | JF723263 | SC/1995 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| G | SCGT 7 | JF723264 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| L | SCGT 16 | JF723265 | SC/1995 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| H | SCGT 17 | JF723266 | SC/1995 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| L | SCI 1 | JF723234 | GA/1993 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| B | SCI 3 | JF723235 | GA/1993 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| G | SCSC 2 | JF723267 | SC/1995 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| G | SCSC 3 | JF723268 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| G | SCSC 5 | JF723269 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| G | SCSC 6 | JF723270 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| B | SCW 1 | JF723242 | SC/1994 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| H | SCW 2 | JF723243 | SC/1994 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| B | SCW 3 | JF723244 | SC/1994 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| H | SCW 4 | JF723245 | SC/1994 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| H | SCW 6 | JF723246 | SC/1994 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| L | SCW 9 | JF723247 | SC/1994 | S. hispidus | Spirochete culture |

| L | SCW 12 | JF723248 | SC/1994 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| B | SCW 25 | JF723249 | SC/1994 | P. gossypinus | Spirochete culture |

| L | SCW 43 | JF723250 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| L | SCW 44 | JF723251 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| H | SCW 47 | JF723252 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| L | SCW 48 | JF723253 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| B | SCW 53 | JF723254 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| L | SCW 54 | JF723255 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| G | SCW 57 | JF723256 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| B | SCW 58 | JF723257 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| G | SCW 59 | JF723258 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| L | SCW 60 | JF723259 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| L | SCW 61 | JF723260 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| B | SCW 62 | JF723261 | SC/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| L | SI 14 | JF723236 | GA/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| B | SI 15 | JF723237 | GA/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| L | SI 16 | JF723238 | GA/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| L | SI 17 | JF723239 | GA/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| G | SI 18 | JF723240 | GA/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| L | SI 19 | JF723241 | GA/1995 | I. affinis | Spirochete culture |

| D | BOR4 | JQ308215 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| H | BOR53 | JQ308216 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| E3 | BTE68 | JQ308217 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| A | BTW11 | JQ308218 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| E3 | BTW16 | JQ308219 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| H3 | BTW37 | JQ308220 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| G | BTW52 | JQ308221 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| M | BTW62 | FJ932736 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| H3 | BTW67 | JQ308222 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| D | CHRW46 | JQ308223 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| A | CHRW57 | JQ308224 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| A | FCR13 | JQ308225 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| F | HOPK32 | JQ308226 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| G | HOPN45 | JQ308227 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| I3 | HPS6 | FJ932734 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| I3 | HPS61 | JQ308235 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| E3 | HRPW89 | FJ932732 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| B | HUMB27 | JQ308233 | CA/2004 | T. senex | Spirochete culture |

| E3 | HUMB150 | JQ308234 | CA/2004 | N. fuscipes | Spirochete culture |

| E3 | LAG24 | JQ308228 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| H3 | LMSW22 | JQ308229 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| H3 | MCCP65 | FJ932733 | CA/2004 | I. pacificus | Spirochete culture |

| H3 | SGE03-1 | JQ308230 | CA/2003 | S. griseus | Spirochete culture |

| H | SGE03-4 | JQ308231 | CA/2003 | S. griseus | Spirochete culture |

| A | SGE03-7 | JQ308232 | CA/2003 | S. griseus | Spirochete culture |

Asterisks indicate representation by 3 (*), 2 (**), 9 (***), or 21 (****) identical sequences.

Additional identical strains in group are indicated in parentheses.

DNA purification, PCR amplification, and sequencing.

Total Borrelia DNA was purified by using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen). Partial ospC genes were amplified by using previously described ospC primers (16) and protocols (38, 42, 43). PCR products from the European and southeastern U.S. samples were sequenced at the University of Washington, while ospC products from California strains were sequenced at the University of California, Berkeley, sequencing facility. All 127 samples were sequenced at the ospC locus directly in both directions and then assembled and edited by using DNAStar (DNAStar, United Kingdom). The BLASTN algorithm was used to confirm identity against GenBank data.

Data analysis.

Sequences were aligned by using Clustal X (44). Because a high level of recombination was confirmed for the Borrelia ospC gene, a cladistic analysis was deemed inappropriate (45). Clustering analysis was performed by using the neighbor-joining method with uncorrected (raw) pairwise sequence distances, as modified in BioNJ (46). One thousand bootstrap replicates were performed under a neighbor-joining search to obtain support values for clusters. A 50% majority-rule consensus tree was formed, with ties broken randomly if encountered.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All sequences obtained in this study have been submitted to the GenBank database under accession numbers listed in Table 2.

RESULTS

The comparative analysis presented here includes partial sequences of ospC genes from 227 Borrelia strains (100 control and 127 experimental strains) originating from areas in Europe and the northeastern, midwestern, and far-western United States where LD is recognized to be endemic and from the southeastern United States, which, for a long time, was considered to be a region where LD was not endemic.

The southeastern U.S. samples of Borrelia contained 22 strains isolated from I. affinis, 1 from I. scapularis, 25 from P. gossypinus, 1 from N. floridana, and 4 from S. hispidus. California samples included 20 isolates from I. pacificus, 3 from Sciurus griseus, 1 from Tamias senex, and 1 from Neotoma fuscipes. Among 49 European Borrelia samples, 15 originated from I. ricinus, and 34 originated from humans. Most ospC amplicons were 525 to 610 bp long (depending upon which PCR primers were used) and were truncated to 498 bp to achieve a perfect alignment. Four samples had to be removed from the neighbor-joining analysis because they were too short (<200 bp). These samples were placed into clusters with samples whose sequences were identical over the length of the sequence fragment that we were able to obtain for them on the assumption that this represents the best clustering position for the sequence available.

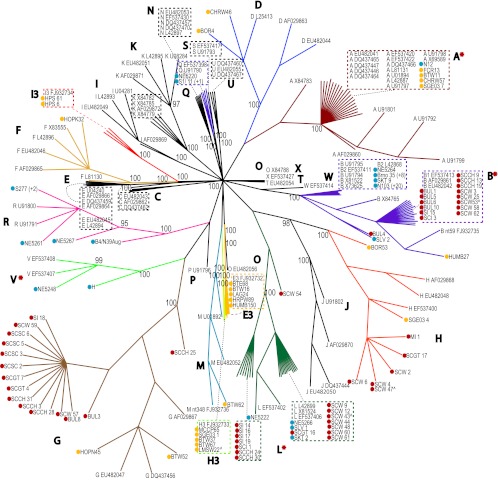

ospC sequences from the experimental samples were identified as one of the known ospC alleles by their strong clustering with control sequences in the analysis. In total, 14 ospC alleles were identified among the 127 experimental samples (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Unrooted neighbor-joining distance tree generated in BioNJ and based on nucleotide sequence alignment of 498-bp fragments of ospC genes. Nodes are labeled with the percent bootstrap support when the value is 90% or higher. All clades are marked by capital letters that show the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto ospC type. All experimental samples in each clade are labeled to indicate the sample origin, as follows: a blue dot in front of a sample name indicates a European origin, a golden dot indicates a Californian origin, and a red dot indicates a southeastern U.S. origin. All unmarked sample names are control samples previously identified as members of an ospC type and downloaded from GenBank. Samples with a ∧ symbol after their name are those that were not included in the analysis but were placed into clusters with samples whose sequences were identical over the length of the sequence fragment that we were able to obtain for them (see the text). Clades that include experimental B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains isolated from European LD patients are marked with red asterisks.

Clades B, D, E3, F, G, H, H3, I3, L, M, Q, R, and V contained experimental samples and were all well supported (bootstrap values of 100%) with apparent monophyly of the clade type samples (those taken from GenBank and designated previously). Clade A received 81% bootstrap support when all samples were included; but ignoring one control sample (X84738), the clade received 100% support. In one anomaly, the ospC allele E3 clade, which included samples from California and one control ospC allele E3 strain, clustered tightly with one control type O strain from the northeastern United States. The other control ospC allele O strain was placed onto a separate branch, alone. This is evidence that what has been classified as B. burgdorferi sensu stricto genotype O is not monophyletic. Overall, clades containing experimental samples were scattered throughout the tree and represented a broad variety of ospC alleles.

North American samples.

ospC allele G, the third most abundant type among experimental samples, was detected only in North American samples. It was present equally in vector- and host-derived strains from the southeastern United States that clustered with strains from the northeastern United States. ospC allele G was also detected in 2 I. pacificus nymphs.

ospC allele H was the fourth most abundant allele detected among southeastern U.S. B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains cultured from ear clips, bladders, spleen, kidney, and hearts of multiple rodent hosts and a single I. affinis nymph. ospC allele H strains from California were cultured from an I. pacificus nymph and a western gray squirrel (S. griseus). This ospC allele was not detected in ticks or in hosts collected from any European locality sampled in this study (Table 2).

California-specific ospC alleles E3 and H3 were both detected in hosts and I. pacificus ticks, the main vector of spirochetes from the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex from the far-western United States. ospC alleles D, I3, and M were detected in I. pacificus only. The neighbor-joining analysis revealed that the only experimental samples that fell into the H3 and I3 clades were from California. Californian ospC alleles D and M clustered with northeastern B. burgdorferi sensu stricto allele D and M control sequences. ospC alleles D, E3, H3, I3, and M were not detected among the European or southeastern U.S. samples.

The southeastern U.S. strains of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto contained ospC alleles B, G, H, and L, with an almost equal representation of alleles B, G, and L (30% each). California samples showed the largest number of ospC alleles (A, B, D, E3, F, G, H, H3, I3, and M) found at any one location. ospC allele L was not found in California, despite it being widely distributed in ticks and hosts in the southeastern United States and connected to human LD in Europe.

European samples.

ospC alleles Q, R, and V were found among the European B. burgdorferi sensu stricto samples only (Table 2). Clades Q and R contained only vector-originated spirochete samples from control and experimental groups; clade V contained both tick- and human-originated strains (Fig. 1).

The highest level of diversity of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto ospC alleles (type per number of samples) was detected in Neuchâtel, Switzerland. Five out of six (83%) ospC alleles detected among all European samples were found in seven spirochete cultures isolated from I. ricinus nymphs collected from this single location in Switzerland: ospC alleles B (one culture), L (two), Q (one), R (two), and V (one) (Table 2).

Transcontinental samples.

Three ospC alleles (A, B, and L) were detected in European and North American B. burgdorferi sensu stricto samples.

ospC allele A, associated with the most pathogenic strains of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, was detected in a serum sample from a patient (N12/JQ219683) with a LD diagnosis from the southern Czech Republic. Four other ospC allele A strains were identified among the Californian isolates (Table 2). All five ospC sequences were 100% identical and clustered clearly (100% bootstrap support) with control sequences from European countries where LD is endemic as well as from the northeastern and midwestern United States. ospC allele A was not detected in the samples from the southeastern United States (Table 2).

ospC allele B was the most abundant among the European samples of human origin (skin, blood, serum, cerebrospinal fluid, or joint fluid of the patients) and was the most represented among the host- and vector-originated southeastern U.S. strains (Table 2). One ospC allele B strain was cultivated from T. senex (Allen's chipmunk) captured in California. The ospC allele B clade consisted of two subclades, one containing a preponderance of southeastern U.S. samples (SCW/SCCH/BUL) clustered with ospC allele B strains from New York and Michigan and another consisting of European control and experimental samples.

Eighty percent of ospC allele L strains (the second most abundant) were detected among southeastern U.S. B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains cultured from non-human-biting I. affinis ticks or from ear clips, bladders, and hearts of local rodent hosts. The remaining 20% of ospC allele L strains were isolated from I. ricinus nymphs and from the skin of a Slovenian patient (SLV1/JQ236853) diagnosed with acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Since the recognition of Lyme disease in the 1970s, discussions of it etiology attracted attention of the wide scientific community and the general public. Our analysis of the population structure of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in the southeastern United States represents the logical extension of similar studies conducted in the northeastern United States, where the disease is highly endemic, and the midwestern United States, where the disease is moderately endemic. The presented results are not meant to be a statistical analysis with an emphasis on the ranking of Borrelia ospC alleles but rather an invitation to an open discussion to advance the natural history and understanding of the enzootiology of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in the southeastern United States, previously considered to be a “low-or-no” Lyme disease region.

Even though several different spirochete species cause LD, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is still considered the major species that causes clinical illness in the United States. It also causes LD in Europe although at a lower rate. Molecular analysis revealed an overlap of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto genotypes between European and North American spirochete populations (9). While most B. burgdorferi sensu lato species or subtypes in Europe are specialized to infect specific taxa of vertebrate hosts (“specialists”), B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, as a “generalist,” has the ability to infect a wide range of phylogenetically diverse vertebrates. In fact, B. burgdorferi sensu lato spirochetes are one of the few groups of zoonotic pathogens for which a molecular mechanism of host “specialism” or “generalism” has been proposed (75).

B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is transmitted from one vertebrate host to another by Ixodes sp. ticks belonging to the Ixodes ricinus complex. All parasitic stages of these ticks are able to transmit the pathogen, but the nymphal stage appears to be the most important one (47–50). A notable exception is the Asian species I. persulcatus, in which the female tick, not the nymph, is a primary vector of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. In Europe, B. burgdorferi is transmitted by I. ricinus ticks (27). In the United States, I. scapularis is the primary vector of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in the eastern, northeastern, and north-central regions (2), whereas I. pacificus is the primary vector in the far-western part of the United States (51, 52). The majority of LD cases come from the Northeast (>80%) (53), where the population of I. scapularis human-biting tick vectors is well established. Lyme disease in the Midwest has received little attention, most probably because the distribution of I. scapularis and establishment of a local population in that region were recognized only recently (54), and only around 12% of human LD cases were reported from that region (33). LD in the southeastern United States received even less attention due to the presumably low abundance of I. scapularis and the recognition of Amblyomma americanum, which does not transmit B. burgdorferi, as a major human-biting tick in this region (55). What is needed to be taken into consideration is, as correctly noticed by Stromdahl and Hickling, that “the lack of detection of a tick species is not proof of that species' absence from the survey area” (55). Collection methods are biased for specific tick species, development stages, collection season, and sampling region (J. H. Oliver, Jr., unpublished data). Unfortunately, past tick surveys in the southeastern United States were affected by the amount of efforts in the sampling of different habitats and hosts and the lack of experience with region-specific methodologies. An I. scapularis distribution map from 1945 indicated that this tick species was widely distributed in the southeastern United States (56). Even though the southeastern U.S. tick population has undergone dramatic changes due to the increasing wild host population, climate changes, urbanization, or geographical spread, it still does not mean that the southeastern U.S. I. scapularis population was decreased so significantly. The rapid expansion of I. scapularis ticks in the northeastern United States and the recent invasion of the midwestern United States originated from a very few migrants from the southeastern region after the recession of Pleistocene ice sheets (57). The midwestern tick populations are much younger than the northeastern ones, and both are an order of magnitude younger than the southeastern population of I. scapularis. This fact led to the hypothesis that ticks were introduced or reintroduced into new areas by long-distance migration maintained by birds (4, 54, 57–59). As the distribution pattern of B. burgdorferi and recolonization of new regions by this pathogen are tightly linked to its tick vectors or vertebrate hosts, we can presume, from one side, that northeastern and midwestern strains of B. burgdorferi have the same origin as their main tick vector, I. scapularis, which is the southeastern United States. From the other side, the strict connection of the pathogen distribution pattern to the pattern of distribution of its principal vector is naive, as we still do not know how much the pathogen and vector share a common evolutionary or biogeographic history (54, 57).

Several other tick species in the I. ricinus complex and those not included in it have been found to maintain B. burgdorferi enzootically (2, 4, 51, 60–62). A recent report by Hamer and colleagues showed strong evidences that confirmed the presence of multiple strains of B. burgdorferi in areas with an apparent absence of I. scapularis, which means an absence of the classical spirochete maintenance cycle of I. scapularis-P. leucopus (54). This study supports the previously presented hypotheses of an uncoordinated phylogeography of B. burgdorferi and its tick vector I. scapularis (57) and the impact of the migratory hosts on pathogen expansion (58, 59). Despite the strong association of LD spirochetes with I. scapularis, the population structure, evolutionary history, and biogeography of the pathogen are distinct from those of its arthropod vector (57).

Except for the abundant tick vector, appropriate vertebrate hosts are required for enzootic maintenance of B. burgdorferi. There is a variety of vertebrate hosts, including small mammals and birds, that might serve as reservoir hosts for B. burgdorferi in the United States. However, in general, rodents appear to be the most common reservoir hosts in the North American regions where LD is endemic (2, 28, 34, 52, 63, 64). Recent studies suggested that migration of infected vertebrate hosts may have a larger impact on the contemporary expansion of the pathogen population than the movement of tick vectors (54, 57). The low prevalence of B. burgdorferi in I. scapularis does not necessarily mean that there is a low prevalence or an absence of the pathogen in the region, taking into consideration the existence of “cryptic” maintenance cycles or the impact of migrating infected reservoir hosts (54). A convincing scenario showing how migrating hosts may accelerate the increasing risk of LD to humans through the maintenance of B. burgdorferi in the absence of classic I. scapularis-P. leucopus transmission was recently presented by Hamer and colleagues (54).

An association between LD severity and ospC alleles was reported previously (9, 50, 65, 66). Twenty-eight ospC alleles have been identified in B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (67). While some spirochete complexes were believed to be restricted exclusively to North America (genotypes B1, C, D, F, G, H, I, J, N, and U) or exclusively to Europe (genotypes B2, S, L, Q, and V), three ospC types (A, E, and K) were previously detected on both continents. Furthermore, the sequences of the isolates were identical, suggesting that each group was able to thrive in a new niche consisting of novel vector and host species with little or no genetic change (9). To date, four ospC alleles, A, B, I, and K, are responsible for systemic LD in humans around the world (9, 22). Additional genotypes, C, D, N, F, H, E, G, and M, have been found in disseminated sites (18–21). Some of the ospC alleles that correlate with human invasiveness were recently detected in the southeastern United States, where the disease is not endemic.

LD is increasing in incidence and is spreading geospatially. Approximately 85,000 Lyme disease cases are estimated in Europe every year (68). Nearly 30,000 confirmed cases of LD were reported in 2009 in the United States, in addition to another 8,500 probable cases (http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/chartstables/reportedcases_statelocality.html). Taking into consideration the significant number of underreported cases, the total annual number of LD cases in the world might be as high as 255,000 (69). The spreading or exchange of highly pathogenic spirochete clones between continents might be supported by the transoceanic migration of host species, especially birds.

Analysis of 53 B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains cultivated from tick vectors and rodent hosts from the southeastern United States revealed that 30% of isolates were ospC allele L strains, a type previously considered to be exclusively European (9). Most of the samples were cultured from I. affinis, ticks that usually do not bite humans, thus playing little if any role in the direct transmission of B. burgdorferi to humans, as well as from ear clips or bladders of two major reservoir hosts of B. burgdorferi in the southeastern United States, Peromyscus gossypinus and Sigmodon hispidus. ospC allele L shared a frequency of distribution with ospC allele B strains (30.2% each) in the southeastern United States. Two other ospC alleles detected among the 53 B. burgdorferi strains were alleles G and H (28.3% and 11.3%, respectively) (70). It was believed that ospC allele L very rarely, if ever, causes human disease (9, 18, 22). Concerning the infectivity to nonhuman species, it was previously found that B. burgdorferi ospC allele L strains are not infectious to four principal reservoir host species in the northeastern region of hyperendemicity, Peromyscus leucopus (white-footed mouse), Tamias striatus (eastern chipmunk), Blarina brevicauda (short-tailed shrew), and Sciurus carolinensis (gray squirrel) (17). However, as analyzed in this study, B. burgdorferi ospC allele L strains showed the ability to disseminate in two of the most common natural reservoir hosts in the South, the cotton mouse (P. gossypinus) and the cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus). It is possible that the interspecific variation in the vertebrate immune system may provide resistance to infection by certain ospC alleles (70). The limited distribution of both primary reservoir hosts of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto ospC type L strains, the cotton mouse P. gossypinus and the cotton rat S. hispidus, and the knowledge that they are parasitized by I. scapularis, I. affinis, I. minor, Dermacentor variabilis, and Amblyomma maculatum (2) suggest that globally rare ospC allele L might be limited largely to the southeastern United States. This conclusion is indirectly supported by previous work by Anderson and Norris (71). Studying the genetic diversity of B. burgdorferi in P. leucopus in southern Maryland, those authors found 5 different ospC types among Maryland samples: alleles A, B, G, H, and K. Southern Maryland represents the border between the regions of distribution of P. leucopus and P. gossypinus. While ospC alleles B, G, and H are present in the southeastern states of the United States and in southern Maryland, ospC allele L is restricted to the southeastern part only, most probably confirming the strong host specificity of this ospC allele for local rodent hosts. At the same time, ospC alleles A and K are present only in regions of distribution of P. leucopus and are absent in the Southeast, where P. gossypinus replaces P. leucopus.

Detection of the invasive ospC type B in 30% of samples was unexpected for strains from the southeastern United States. This raises the question of whether the risk of LD to humans in this region has been overlooked or if the geographic distribution of the LD spirochete has evolved over time. In order for LD to occur, humans must be exposed to invasive strains via a tick bite. However, the above-mentioned ospC allele B was detected in spirochete strains isolated from either rodent hosts or tick vectors that rarely bite humans. Previous analyses of non-human-biting I. affinis ticks from the southeastern United States revealed that they are heavily infected with B. burgdorferi (33 to 35%) (72, 73). Most probably, maintenance vectors such as I. affinis could have a significant impact on Lyme disease dynamics, helping to maintain high levels of B. burgdorferi in reservoir hosts that are later fed upon by bridge vectors that often bite humans (2, 57).

It will also be interesting to determine how much the structure of the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto population has changed in Europe. Is it still correct that B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is a strain of minor importance in this part of the world? How much has the pattern of distribution of this species in Europe changed over time, and if it has changed, what are the factors contributing to such changes?

Of 4 ospC alleles, B, G, H, and N, that have been detected in LD patients in the northeastern and midwestern United States, 3 alleles, B, G, and H, at a lower rate, are widely distributed in the southeastern part of the country and are associated with rodent hosts or non-human-biting ticks. ospC allele B, widely distributed in the Northeast and Midwest, is commonly associated with disseminated LD around the world. Together with ospC alleles L and G, it became the most frequent ospC allele among B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains from the southeastern United States. ospC allele H, commonly detected in LD patients from the northeastern and midwestern United States, seems to be the fourth most frequently detected ospC allele in the Southeast. Isolation of ospC allele H strains from secondary sites of host infection may suggest its potential to develop invasive disease. This is in agreement with previous results obtained with human and murine isolates (18).

This is the first expanded ospC genotyping survey of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains from the southeastern United States. Although B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is endemic in many foci over large areas of the southeastern United States, relatively few human cases have been reported from this region. The lower prevalence of LD in the southeastern United States was previously attributed to (i) a parallel cycle involving non-human-biting maintenance vectors, a “cryptic cycle”; (ii) variations in the vertebrate immune system that provide resistance to infection by certain strains; or (iii) different subsets of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto lineages that are present in different regions of the United States (2, 74). This could be determined by differences in the enzootiology of B. burgdorferi in the southeastern United States, which differs fundamentally from that reported for the northeastern United States and Europe. Lyme disease in the southeastern United States might not be a public health problem, but it deserves closer attention as a curious natural event that has all prerequisites, pathogen, competent tick vectors, and an array of reservoir hosts, to develop into a medical problem, turning from an enzootic to a zoonotic system. A detailed preface to an offered discussion about Lyme disease in the southeastern United States (2) is now supported by additional laboratory results. Zoonotic diseases such as LD become a concern when they spill over into the human population. It might be endemic but not yet recognized unless humans become ill and are accurately diagnosed (2). Taking into consideration the changes that have occurred in nature and in human society and the substantial amount of new information concerning the global distribution of LD and its growing list of causative agents, it is time to take a fresh look at LD in the southeastern United States.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the GSU Foundation (United States); by grants CZB1-2963-CB-09 to M.G. and R.S.L. and CZB1-2966-CB-09 to N.R. and J.H.O. from CRDF Global (United States); in part by grant R37AI-24899 from the National Institutes of Health and cooperative agreement award U50/CCU410282 to J.H.O. from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (United States); and with institutional support RVO:60077344 from the Biology Centre, Institute of Parasitology, to N.R., M.G., and L.G. (Czech Republic).

We thank Lise Gern of the Institute of Biology (Neuchâtel, Switzerland), Eva Ruzić-Sabljić of the University of Ljubljana (Ljubljana, Slovenia), Mangesh Bhide of the University of Veterinary Medicine (Kosice, Slovakia), and Gabor Foldvari of the Szent Istvan University (Budapest, Hungary) for providing Borrelia samples and Richard N. Brown of Humboldt State University (Arcata, CA) for providing rodent specimens from California in which borreliae were detected. We are grateful to Earlene Howard of the Institute of Arthropodology and Parasitology (Statesboro, GA) for administrative and technical support of this project.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 21 December 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Kurtenbach K, Hanincová K, Tsao JI, Margos G, Fish D, Ogden NH. 2006. Fundamental processes in the evolutionary ecology of Lyme borreliosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:660–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oliver JH., Jr 1996. Lyme borreliosis in the southern United States: a review. J. Parasitol. 82:926–935 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Comstedt P, Bergström S, Olsen B, Garpmo U, Marjavaara L, Mejlon H, Barbour AG, Bunikis J. 2006. Migratory passerine birds as reservoirs of Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1087–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Olsen B, Duffy DC, Jaenson TG, Gylfe A, Bonnedahl J, Bergström S. 1995. Transhemispheric exchange of Lyme disease spirochetes by seabirds. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:3270–3274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poupon M-A, Lommano E, Humair PF, Douet V, Rais O, Schaad M, Jenni L, Gern L. 2006. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in ticks collected from migratory birds in Switzerland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:976–979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Foretz M, Postic D, Baranton G. 1997. Phylogenetic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto by arbitrarily primed PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marti Ras N, Postic D, Foretz M, Baranton G. 1997. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, a bacterial species “made in the USA”? Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:1112–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Postic D, Ras NM, Lane RS, Humair P, Wittenbrink MM, Baranton G. 1999. Common ancestry of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato strains from North America and Europe. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3010–3012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Qiu WG, Bruno JF, McCaig WD, Xu Y, Livey I, Schriefer ME, Luft BJ. 2008. Wide distribution of a high-virulence Borrelia burgdorferi clone in Europe and North America. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14:1097–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Girard YA, Fedorova N, Lane RS. 2011. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi and detection of B. bissettii-like DNA in serum of north-coastal California residents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:945–954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Grubhoffer L, Oliver JH., Jr 2011. Updates on Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex with respect to public health. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2:123–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Mokrácek A, Piskunová N, Ruzek D, Mallatová N, Grubhoffer L. 2008. Detection of Borrelia bissettii in cardiac valve tissue of a patient with endocarditis and aortic valve stenosis in the Czech Republic. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3540–3543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Rùzek D, Piskunova N, Mallátová N, Grubhoffer L. 2009. Molecular detection of Borrelia bissettii DNA in serum samples from patients in the Czech Republic with suspected borreliosis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 292:274–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liveris D, Gazumyan A, Schwartz I. 1995. Molecular typing of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:589–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liveris D, Varde S, Iyer R, Koenig S, Bittker S, Cooper D, McKenna D, Nowakowski J, Nadelman RB, Wormser GP, Schwartz I. 1999. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi in Lyme disease patients as determined by culture versus direct PCR with clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:565–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang IN, Dykhuizen DE, Qiu W, Dunn JJ, Bosler EM, Luft BJ. 1999. Genetic diversity of ospC in a local population of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. Genetics 151:15–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brisson D, Dykhuizen DE. 2004. OspC diversity in Borrelia burgdorferi: different hosts are different niches. Genetics 168:713–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alghaferi MY, Anderson JM, Park J, Auwaerter PG, Aucott JN, Norris DE, Dumler JS. 2005. Borrelia burgdorferi ospC heterogeneity among human and murine isolates from a defined region of northern Maryland and southern Pennsylvania: lack of correlation with invasive and noninvasive genotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1879–1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brisson D, Baxamusa N, Schwartz I, Wormser GP. 2011. Biodiversity of Borrelia burgdorferi strains in tissues of Lyme disease patients. PLoS One 6:e22926 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dykhuizen DE, Brisson D, Sandigursky S, Wormser GP, Nowakowski J, Nadelman RB, Schwartz I. 2008. The propensity of different Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto genotypes to cause disseminated infections in humans. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 78:806–810 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ivanova L, Christova I, Neves V, Aroso M, Meirelles L, Brisson D, Gomes-Solecki M. 2009. Comprehensive seroprofiling of sixteen B. burgdorferi OspC: implications for Lyme disease diagnostics design. Clin. Immunol. 132:393–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Seinost G, Dykhuizen DE, Dattwyler RJ, Golde WT, Dunn JJ, Wang IN, Wormser GP, Schriefer ME, Luft BJ. 1999. Four clones of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto cause invasive infection in humans. Infect. Immun. 67:3518–3524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang G, Ojaimi C, Iyer R, Saksenberg V, McClain SA, Wormser GP, Schwartz I. 2001. Impact of genotypic variation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto on kinetics of dissemination and severity of disease in C3H/HeJ mice. Infect. Immun. 69:4303–4312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang G, Ojaimi C, Wu H, Saksenberg V, Iyer R, Liveris D, McClain SA, Wormser GP, Schwartz I. 2002. Disease severity in a murine model of Lyme borreliosis is associated with the genotype of the infecting Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto strain. J. Infect. Dis. 186:782–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Anderson JF. 1988. Mammalian and avian reservoirs for Borrelia burgdorferi. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 539:180–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson JF. 1989. Ecology of Lyme disease. Conn. Med. 53:343–346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gern L. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, the agent of Lyme borreliosis: life in the wilds. Parasite 15:244–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lane RS, Piesman J, Burgdorfer W. 1991. Lyme borreliosis: relation of its causative agent to its vectors and hosts in North America and Europe. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 36:587–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Qiu WG, Bosler EM, Campbell JR, Ugine GD, Wang IN, Luft BJ, Dykhuizen DE. 1997. A population genetic study of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto from eastern Long Island, New York, suggested frequency-dependent selection, gene flow and host adaptation. Hereditas 127:203–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Theisen M, Borre M, Mathiesen MJ, Mikkelsen B, Lebech AM, Hansen K. 1995. Evolution of the Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface protein OspC. J. Bactriol. 177:3036–3044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang G, van Dam AP, Dankert J. 1999. Evidence for frequent ospC gene transfer between Borrelia valaisiana sp. nov. and other Lyme disease spirochetes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 177:289–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bunikis J, Garpmo U, Tsao J, Berglund J, Fish D, Barbour AG. 2004. Sequence typing reveals extensive strain diversity of the Lyme borreliosis agents Borrelia burgdorferi in North America and Borrelia afzelii in Europe. Microbiology 150:1741–1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Qiu WG, Dykhuizen DE, Acosta MS, Luft BJ. 2002. Geographic uniformity of the Lyme disease spirochete (Borrelia burgdorferi) and its shared history with tick vector (Ixodes scapularis) in the Northeastern United States. Genetics 160:833–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Barbour AG, Fish D. 1993. The biological and social phenomenon of Lyme disease. Science 260:1610–1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. O'Connell S. 2011. Lyme borreliosis and other ixodid tick-borne diseases—a European perspective, p. 405–435 In Critical needs and gaps in understanding prevention, amelioration, and resolution of Lyme and other tick-borne diseases: the short-term and long-term outcomes. National Academies Press, Washington, DC: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Piesman J, Gern L. 2004. Lyme borreliosis in Europe and North America. Parasitology 129(Suppl):S191–S220 doi:10.1017/S0031182003004694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Grubhoffer L, Oliver JH., Jr 2011. Borrelia carolinensis sp. nov., a new species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex isolated from rodents and a tick from the south-eastern USA. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 61:381–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Lin T, Gao L, Grubhoffer L, Oliver JH., Jr 2009. Delineation of a new species of the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex, Borrelia americana sp. nov. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3875–3880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stanek G, Fingerle V, Hunfeld KP, Jaulhac B, Kaiser R, Krause A, Kristoferitsch W, O'Connell S, Ornstein K, Strle F, Gray J. 2011. Lyme borreliosis: clinical case definitions for diagnosis and management in Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17:69–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hubalek Z. 2009. Epidemiology of Lyme borreliosis. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 37:31–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Steere AC, Coburn J, Glickstein L. 2004. The emergence of Lyme disease. J. Clin. Invest. 113:1093–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Girard YA, Travinsky B, Schotthoefer A, Fedorova N, Eisen RJ, Eisen L, Barbour AG, Lane RS. 2009. Population structure of the Lyme borreliosis spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi in the western black-legged tick (Ixodes pacificus) in Northern California. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:7243–7252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Grubhoffer L, Oliver JH., Jr 2009. Borrelia carolinensis sp. nov., a new (14th) member of the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex from the southeastern region of the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:134–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brisson D, Vandermause MF, Meece JK, Reed KD, Dykhuizen DE. 2010. Evolution of northeastern and midwestern Borrelia burgdorferi, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16:911–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gascuel O. 1997. BIONJ: an improved version of the NJ algorithm based on a simple model of sequence data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 14:685–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Anderson JF, Magnarelli LA, Stafford KC., III 1990. Bird-feeding ticks transstadially transmit Borrelia burgdorferi that infect Syrian hamsters. J. Wildl. Dis. 26:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Danielová V, Daniel M, Schwarzová L, Materna J, Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Holubová J, Grubhoffer L, Kilián P. 2010. Integration of a tick-borne encephalitis virus and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato into mountain ecosystems, following a shift in the altitudinal limit of distribution of their vector, Ixodes ricinus (Krkonose mountains, Czech Republic). Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 10:223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kurtenbach K, Peacey M, Rijpkema SG, Hoodless AN, Nuttall PA, Randolph SE. 1998. Differential transmission of the genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by game birds and small rodents in England. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1169–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Scott JD, Lee MK, Fernando K, Durden LA, Jorgensen DR, Mak S, Morshed MG. 2010. Detection of Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, including three novel genotypes in ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) collected from songbirds (Passeriformes) across Canada. J. Vector Ecol. 35:124–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Brown RN, Lane RS. 1992. Lyme disease in California: a novel enzootic transmission cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Science 256:1439–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lane RS, Loye JE. 1991. Lyme disease in California: interrelationship of ixodid ticks (Acari), rodents, and Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Med. Entomol. 28:719–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Orloski KA, Hayes EB, Campbell GL, Dennis DT. 2000. Surveillance for Lyme disease—United States, 1992-1998. MMWR CDC Surveill. Summ. 49:1–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hamer SA, Hickling GJ, Sidge JL, Rosen ME, Walker ED, Tsao JI. 2011. Diverse Borrelia burgdorferi strains in a bird-tick cryptic cycle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:1999–2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stromdahl E, Hickling G. 2012. Beyond Lyme: aetiology of tick-borne human diseases with emphasis on the South-Eastern United States. Zoonoses Public Health 59:48–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bishopp FC, Trembley HL. 1945. Distribution and hosts of certain North American ticks. J. Parasitol. 31:1–54 [Google Scholar]

- 57. Humphrey PT, Caporale DA, Brisson D. 2010. Uncoordinated phylogeography of Borrelia burgdorferi and its tick vector, Ixodes scapularis. Evolution 64:2653–2663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ogden NH, Lindsay LR, Hanincová K, Barker IK, Bigras-Poulin M, Charron DF, Heagy A, Francis CM, O'Callaghan CJ, Schwartz I, Thompson RA. 2008. Role of migratory birds in introduction and range expansion of Ixodes scapularis ticks and of Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in Canada. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:1780–1790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ogden NH, Margos G, Aanensen DM, Drebot MA, Feil EJ, Hanincová K, Schwartz I, Tyler S, Lindsay LR. 2011. Investigation of genotypes of Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes scapularis ticks collected during surveillance in Canada. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:3244–3254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Anderson JF, Magnarelli LA, LeFebvre RB, Andreadis TG, McAninch JB, Perng GC, Johnson RC. 1989. Antigenically variable Borrelia burgdorferi isolated from cottontail rabbits and Ixodes dentatus in rural and urban areas. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:13–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gern L, Rouvinez E, Toutoungi LN, Godfroid E. 1997. Transmission cycles of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato involving Ixodes ricinus and/or I. hexagonus ticks and the European hedgehog, Erinaceus europaeus, in suburban and urban areas in Switzerland. Folia Parasitol. (Praha) 44:309–314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Oliver JH, Jr, Chandler FW, Jr, James AM, Huey LO, Vogel GN, Sanders FH., Jr 1996. Unusual strain of Borrelia burgdorferi isolated from Ixodes dentatus in central Georgia. J. Parasitol. 82:936–940 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Oliver JH, Jr, Chandler FW, Jr, James AM, Sanders FH, Jr, Hutcheson HJ, Huey LO, McGuire BS, Lane RS. 1995. Natural occurrence and characterization of the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, in cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus) from Georgia and Florida. J. Parasitol. 81:30–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Oliver JH, Jr, Chandler FW, Jr, Luttrell MP, James AM, Stallknecht DE, McGuire BS, Hutcheson HJ, Cummins GA, Lane RS. 1993. Isolation and transmission of the Lyme disease spirochete from the southeastern United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:7371–7375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hanincová K, Liveris D, Sandigursky S, Wormser GP, Schwartz I. 2008. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto is clonal in patients with early Lyme borreliosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:5008–5014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Strle K, Jones KL, Drouin EE, Li X, Steere AC. 2011. Borrelia burgdorferi RST1 (OspC type A) genotype is associated with greater inflammation and more severe Lyme disease. Am. J. Pathol. 178:2726–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Barbour AG, Travinsky B. 2010. Evolution and distribution of the ospC gene, a transferable serotype determinant of Borrelia burgdorferi. mBio 1(4):e00153–10 doi:10.1128/mBio.00153-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lindgren E, Jaenson TGT. 2006. Lyme borreliosis in Europe: influences of climate and climate change, epidemiology and adaptation measures, p 157–188 In Menne B, Ebi KL. (ed), Climate change and adaptation strategies for human health. Steinkopff, Darmstadt, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 69. Campbell GL, Fritz CL, Fish D, Nowakowski J, Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. 1998. Estimation of the incidence of Lyme disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 148:1018–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rudenko N, Golovchenko M, Grubhoffer L, Oliver JH., Jr 2013. The rare ospC allele L of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, commonly found among samples collected in a coastal plain area of the southeastern United States, is associated with Ixodes affinis ticks and local rodent hosts Peromyscus gossypinus and Sigmodon hispidus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:1403–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Anderson JM, Norris DE. 2006. Genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto in Peromyscus leucopus, the primary reservoir of Lyme disease in a region of endemicity in southern Maryland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5331–5341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Harrison BA, Rayburn WH, Jr, Toliver M, Powell EE, Engber BR, Durden LA, Robbins RG, Prendergast BF, Whitt PB. 2010. Recent discovery of widespread Ixodes affinis (Acari: Ixodidae) distribution in North Carolina with implications for Lyme disease studies. J. Vector Ecol. 35:174–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Maggi RG, Reichelt S, Toliver M, Engber B. 2010. Borrelia species in Ixodes affinis and Ixodes scapularis ticks collected from the coastal plain of North Carolina. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 1:168–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lane RS, Quistad GB. 1998. Borreliacidal factor in the blood of the western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis). J. Parasitol. 84:29–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Woolhouse ME, Taylor LH, Haydon DT. 2001. Population biology of multihost pathogens. Science 292:1109–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]