Abstract

Determination of the complete nucleotide sequence of a cryptic plasmid, pMBLT00, from Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides KCTC13302 revealed that it contains 20,721 bp, a G+C content of 38.7%, and 18 open reading frames. Comparative sequence and mung been nuclease analyses of pMBLT00 showed that pMBLT00 replicates via the theta replication mechanism. A new, stable Escherichia coli-Leuconostoc shuttle vector, pMBLT02, which was constructed from a theta-replicating pMBLT00 replicon and an erythromycin resistance gene of pE194, was successfully introduced into Leuconostoc, Lactococcus lactis, and Pediococcus. This shuttle vector was used to engineer Leuconostoc citreum 95 to overproduce d-lactate. The L. citreum 95 strain engineered using plasmid pMBLT02, which overexpresses d-lactate dehydrogenase, exhibited enhanced production of optically pure d-lactate (61 g/liter, which is 6 times greater than the amount produced by the control strain) when cultured in a reactor supplemented with 140 g/liter glucose. Therefore, the shuttle vector pMBLT02 can serve as a useful and stable plasmid vector for further development of a d-lactate overproduction system in other Leuconostoc strains and Lactococcus lactis.

INTRODUCTION

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB), such as Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, Leuconostoc, Pediococcus, and Streptococcus, are Gram positive with a low G+C content and are widely used as lactic acid producers for food and biotechnology applications (1). The biodegradable polylactic acid (PLA) is an environmentally friendly polymer consisting of a lactate monomer (2). Due to the growing market for biodegradable and renewable polymers such as PLA, the selection and characterization of LAB that produce high yields of high lactate titers are required. This PLA is generally produced by the polymerization of l-lactate, called poly-l-lactide (PLLA), which has mechanical properties similar to those of polyethylene terephthalate (PETE) polymer. To improve the properties of PLLA, it is sometimes blended with poly-d-lactide (PDLA), and blends of this stereocomplex of PLLA and PDLA are widely used as sources of various clothing and plastic products. Among the LAB, the genus Leuconostoc is one of several strains that produce d-lactate at a relatively high optical purity and titer (3). In many cases, however, metabolic engineering principles should be applied to Leuconostoc strains to enhance the titer, yield, and optical purity of d-lactate sufficient for commercial use. In principle, metabolic engineering relies on the utilization of plasmids mainly for heterologous gene expression or genome engineering (4). Further, understanding the interactions between plasmid-encoded proteins/enzymes and the metabolism of a host is important for successful metabolic engineering.

Many cryptic LAB plasmids have been isolated, sequenced, and characterized to develop genetic tools, including cloning, gene knockouts, and gene expression (5–8). However, only a few plasmids from the genus Leuconostoc have been sequenced and characterized (9–11). Recently, metabolic engineering of Leuconostoc was reported to produce l-lactate by the overexpression of l-lactate dehydrogenase (l-LDH) (12). However, there are few reports of metabolic engineering of Leuconostoc to enhance the production of d-lactate of high optical purity.

The aims of this study were to develop a novel Leuconostoc heterologous gene expression vector system and to investigate its practicality as a tool for metabolic engineering of Leuconostoc citreum to overproduce optically pure d-lactate.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Leuconostoc mesenteroides and other LAB were routinely cultured in lactobacilli MRS medium (Difco, Detroit, MI), and recombinant LAB harboring the shuttle vectors pMBLT02 or pMBLT02-dLDH were cultivated in MRS medium supplemented with 2% CaCO3 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) under anaerobic conditions at 30°C for 24 h. Escherichia coli was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C with vigorous shaking. Ampicillin was added to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml for E. coli, and erythromycin was added to a final concentration of 20 μg/ml for LAB.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in the present study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides | ||

| KCTC 3733 | Host of pMBLT00 | KCTCb |

| KCTC 3722 | Electroporation host | KCTC |

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. cremoris KCTC 3529 | Electroporation host | KCTC |

| Leuconostoc mesenteroides KCTC 3718 | Electroporation host | KCTC |

| Leuconostoc citreum 95 | Electroporation host | 13 |

| Leuconostoc lactis KCTC 3528 | Electroporation host | KCTC |

| Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis KCTC 3926 | Electroporation host | KCTC |

| Pediococcus acidilactici KCTC 13087 | Electroporation host | KCTC |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis KCTC 3034 | Electroporation host | KCTC |

| Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus KCTC 3635 | Electroporation host | KCTC |

| Lactobacillus johnsonii KCTC 3141 | Electroporation host | KCTC |

| E. coli JM109 | Cloning host | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC19 | E. coli cloning vector; Apr | NEB |

| pE194 | Staphylococcus aureus cloning vector; Emr | 16 |

| pMBLT00 | 20.7-kb cryptic plasmid from L. mesenteroides KCTC 3733 | This study |

| pMBLT01 | pUC19 carrying a 3.3-kb rep-mob gene region; Apr | This study |

| pMBLT02 | E. coli-Leuconostoc shuttle vector; pUC19 carrying a 3.3-kb rep-mob gene region and an Em resistance gene; Apr, Emr | This study |

| pMBLT11 | pUC19 carrying a 2.0-kb rep gene region; Apr | This study |

| pMBLT12 | pUC19 carrying a 2.0-kb rep gene region and a Em resistance gene; Apr, Emr | This study |

Apr, ampicillin resistance; Em, erythromycin; Emr, erythromycin resistance.

KCTC, Korean Collection for Type Culture.

DNA isolation and purification.

Isolation of plasmids from LAB and E. coli was performed using the method of O'Sullivan and Klaenhammer (17) and a standard alkaline lysis method (18), respectively. Isolated plasmids were purified using a DNA-spin plasmid DNA purification kit (iNtRon Biotechnology, Seongnam, South Korea), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Genomic DNA was isolated from LAB using an Exgene Cell SV minikit (GeneAll Biotechnology, Seoul, South Korea), according to the manufacturer's instruction.

General DNA techniques and plasmid transfer.

General procedures for DNA manipulation were conducted as described by Sambrook and Russell (18). Restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA ligase, and Vent DNA polymerase were used according to the supplier's instructions (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). Transformation of plasmids was conducted using a standard heat-shock transformation for E. coli and electroporation for Leuconostoc, as described by Sambrook and Russell (18) and Berthier et al. (19).

DNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis.

To perform random shotgun sequencing of pMBLT00, the plasmid was sheared using a HydroShear DNA shearing machine (Genomic Solutions, Ann Arbor, MI), and the sheared DNA fragments were randomly cloned into a pUC19 vector. Sequencing of the random-clone library was conducted at Macrogen (Seoul, South Korea) using an ABI Prism 3730XL DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Contig assembly was performed using DNASTAR software (DNASTAR, Madison, WI), and primer walking was used to fill the gaps between the sequence fragments. DNA and amino acid sequences were analyzed using the DNASTAR and Artemis12 software (20) programs. Prediction of open reading frames (ORFs) was conducted using the GeneMark (21) and FgenesB (Softberry, Mount Kisco, NY) programs. Gene annotation and similarity analysis were performed using BLAST programs (22) from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Analysis of conserved functional protein domains of the predicted ORFs was conducted using the InterProScan program from the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/InterProScan/) and the NCBI Conserved Protein Domain Database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd) (23). Multiple-sequence alignments were performed using the BLAST2SEQ (24) and CLUSTAL X (25) programs. DNA repeats were detected using the Tandem repeats finder (26) and EMBOSS package (27) programs.

Southern hybridization and detection of single-stranded DNA.

Single-stranded DNA intermediates were digested using mung bean nuclease as previously described (28) and were detected using Southern hybridization with a digoxigenin (DIG) DNA labeling and detection kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Plasmid segregational stability.

The segregational stability of pMBLT02 in Leuconostoc citreum 95 without antibiotic selection pressure was monitored for approximately 100 generations as described previously (29).

Production and analysis of d-lactate.

A chemically defined LAB medium was used for the batch production of d-lactate using recombinant L. citreum strains. The LAB medium contains the following components (per liter): 5 g peptone, 5 g yeast extract, 0.1 g NaCl, 2 g K2HPO4, 0.5 g MgSO4 · 7H2O, and 0.02 mg vitamin B12. Glucose was filter sterilized separately using a 0.22-μm-pore-size syringe filter (Whatman, Clifton, NJ) and was then added with 5 mg/liter of erythromycin (final concentration) to the medium. Batch cultures were carried out at 30°C in a 5-liter jar fermentor (Ko-biotech, South Korea) containing 1.8 liters of LAB medium supplemented with 140 g/liter of glucose. The seed cultures (200 ml) were prepared in the MRS medium. The pH of the culture was maintained at 6.0 by the automatic addition of 14% (vol/vol) NH4OH. Foaming was controlled by adding Antifoam 289 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cell growth was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm using a SPECTRAmax Plus384 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices). A 5- to 10-μl aliquot of cell-free culture medium was applied to an Agilent Technologies 1200 high-pressure liquid chromatography system equipped with an Aminex HPX-87C column (250 by 4 mm; Bio-Rad) and a refractive index detector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The concentrations of glucose, acetate, ethanol, and d-lactate in the culture medium were calculated using known concentrations of standards (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The optical purity of d-lactate was measured using a d-lactic acid assay kit (Megazyme, Ireland).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of pMBLT00 has been deposited in the GenBank Data Library under the accession number JN106352.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Sequence analysis of pMBLT00.

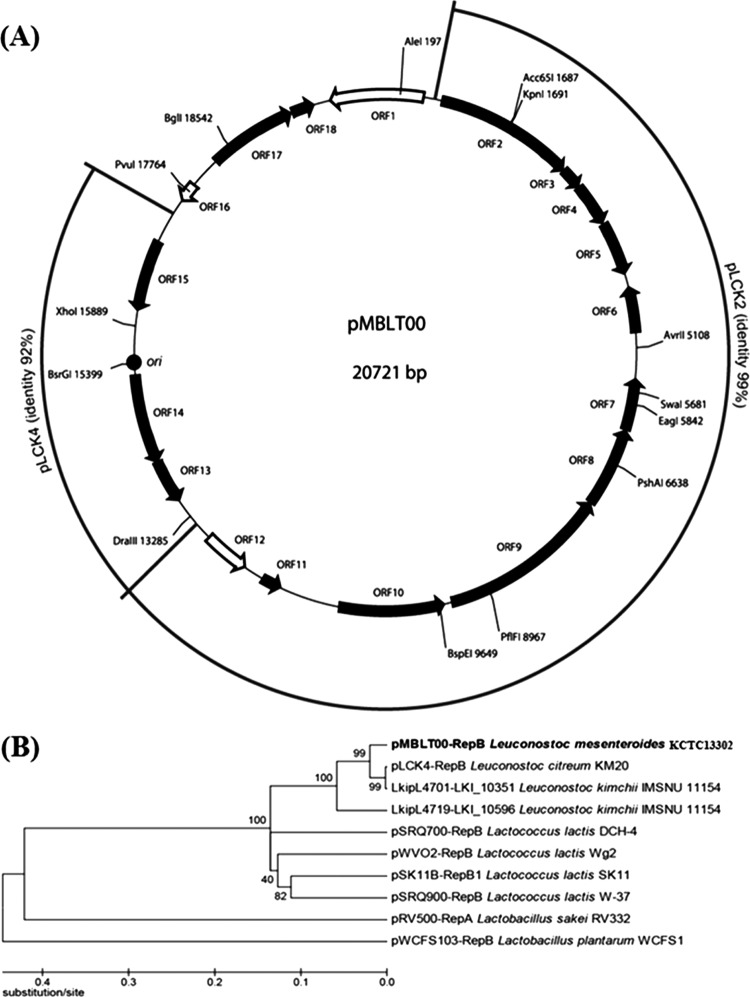

A plasmid, designated pMBLT00, was isolated from Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides KCTC 13302. The complete sequence of pMBLT00 consists of 20,721 bp, 18 ORFs, and a G+C content of 38.7%, which is slightly higher than that of the L. mesenteroides genome (37.7%) (30). Multiple-sequence alignment analysis of pMBLT00 and other closely related plasmids showed that pMBLT00 may contain a fusion of more than 2 plasmids (Fig. 1A). The first DNA cluster containing ORF2 to ORF12 and the second DNA cluster containing ORF13 to ORF15 are probably derived from Leuconostoc plasmids pLCK2 and pLCK4 (31), respectively. However, the third DNA cluster containing ORF16 to ORF18 and ORF1 is not similar to those of other Leuconostoc plasmids.

Fig 1.

(A) Locations of predicted ORFs and restriction enzyme map of plasmid pMBLT00 from Leuconostoc mesenteroides. The 15 black-filled arrows indicate 15 ORFs, the black-filled circle indicates an origin of replication (ori), and the 3 open arrows indicate 3 transposases. The outer circle indicates regions of high sequence identity between pMBLT00 and 2 other Leuconostoc plasmids, pLCK2 and pLCK4. (B) Phylogenetic analysis of Rep proteins in pMBLT00 plasmids with theta-replicating Rep proteins in other closely related plasmids. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method. The numbers associated with the branches represent the bootstrap values.

The first DNA cluster (ORF2 to ORF12) of pMBLT00 may provide additional functions to the host strain and can be divided into 2 distinct DNA subclusters, as follows: subcluster I (ORF2 to ORF5) and subcluster II (ORF6 to ORF11). Subcluster I contains 4 putative genes encoding proteins involved in intracellular copper transfer via a putative cation transport ATPase (ORF2), binding of copper to a putative copper chaperone for activation of superoxide dismutase (SOD) (ORF3), formation of a metalloregulatory protein with a putative DNA-binding ferritin-like protein (ORF4), and a transcriptional regulator of gene expression in this subcluster (ORF5) (Table 2). The combination of these putative genes may work to remove intracellular cytotoxic metal ions and to activate SOD for inducing oxygen tolerance to aid the survival of the host under anaerobic conditions (32). Subcluster II contains 6 putative genes encoding proteins involved in sugar uptake and hydrolysis (ORF10 and ORF9) and bioconversion and dephosphorylation of phosphorylated sugar (ORF8 and ORF7) for utilization of sugar in host cells (Table 2). This gene cluster seems to be regulated by a transcriptional regulator (ORF11). Interestingly, the presence of plasmid-associated integrase/recombinase (ORF6) in subcluster II suggests that the first DNA cluster was derived from other Leuconostoc strains to enhance sugar utilization.

Table 2.

ORF analysis of the pMBLT00 plasmid

| ORF | Function | Position (size [bp]) | % identity | Best BLASTP match | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1 | Transposase | 19984–501Ra (412) | 99% over 412 aab | Transposase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. cremoris plasmid pIC19H | CAA44487 |

| ORF2 | Cation transport ATPase | 748–2598 (616) | 99% over 616 aa | LCK_p200034; cation transport ATPase from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK2 | ACA83569 |

| ORF3 | Copper chaperone | 2599–2898 (99) | 98% over 99 aa | LCK_p200033; copper chaperon from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK2 | ACA83568 |

| ORF4 | DNA-binding ferritin-like protein | 2891–3451 (186) | 98% over 183 aa | LCK_p200032; DNA-binding ferritin-like protein from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK2 | ACA83567 |

| ORF5 | Crp-like transcriptional regulator | 3468–4160 (230) | 100% over 230 aa | LCK_p200031; cyclic AMP-binding protein–catabolite gene activator or regulatory subunit of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK2 | ACA83566 |

| ORF6 | Plasmid-associated integrase/recombinase | 4332–4922R (196) | 97% over 196 aa | LCK_p200030; tyrosine recombinase from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK2 | ACA83565 |

| ORF7 | Beta-phosphoglucomutase | 5507–6178R (223) | 99% over 223 aa | LCK_p200029; phosphatase/phosphohexomutase from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK2 | ACA83564 |

| ORF8 | Aldose 1-epimerase | 6181–7215R (344) | 99% over 343 aa | LCK_p200028; galactose mutarotase from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK2 | ACA83563 |

| ORF9 | Maltose phosphorylase | 7221–9479R (752) | 99% over 752 aa | LCK_p200027; trehalose or maltose hydrolase from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK2 | ACA83562 |

| ORF10 | Major facilitator superfamily permease | 9574–10977R (467) | 99% over 450 aa | LCK_p200026; permease of the major facilitator superfamily from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK2 | ACA83561 |

| ORF11 | Transcriptional regulator | 11778–12047R (89) | 97% over 89 aa | LCK_p200025; transcriptional regulator from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK2 | ACA83560 |

| ORF12 | IS3-associated transposase | 12321–12923R (200) | 99% over 184 aa | ORFC of IS3-like insertion sequence from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK1 | ACA83649 |

| ORF13 | RepB-like protein | 13538–14110R (190) | 74% over 190 aa | LCK_p400006; RepB-like protein from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK4 | ACA83597 |

| ORF14 | RepB protein | 14103–15257R (384) | 94% over 384 aa | LCK_p400005; RepB protein from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK4 | ACA83596 |

| ORF15 | Mobilization protein | 16078–17007R (309) | 80% over 304aa | LCK_p400004; putative mobilization protein from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK4 | ACA83591 |

| ORF16 | Partial transposase | 17618–17869R (83) | 90% over 47 aa | Transposase from L. citreum KM20 plasmid pLCK3 | ACA83588 |

| ORF17 | Ser/Thr protein phosphatase | 18278–19447 (389) | 98% over 389 aa | Ser/Thr protein phosphatase from Pediococcus acidilactici DSM 20284 | EFL94735 |

| ORF18 | Asparagine synthase | 19459–19767 (102) | 68% over 102 aa | Asparagine synthase (glutamine hydrolyzing) from Lactobacillus iners SPIN 2503V10-D | EFO72605 |

R, reverse direction.

aa, amino acids.

The second DNA cluster (ORF13 to ORF15) of pMBLT00 is involved in plasmid replication and mobilization. ORF13 and ORF14 encode a RepB-like protein and the RepB protein, respectively, which are required for replication. The predicted RepB-like protein contains a theta replication-related conserved protein domain (PF04394). The other predicted RepB protein has 3 conserved replication protein domains: an initiator Rep protein (PF01051), a C-terminal sequence of RepB (PF06430), and a winged helix DNA-binding domain (SSF46785). Phylogenetic analysis of the Rep proteins that function in theta replication (Fig. 1B) confirms that pMBLT00 can replicate via theta replication. Interestingly, Rep proteins in theta-replicating Lactobacillus plasmids, such as pRV322 and pWCFS1 (33, 34), are phylogenetically distant from pMBLT00. The predicted protein encoded by ORF15 contains a plasmid mobilization/recombination enzyme domain (PF01076) for plasmid transfer, suggesting that this putative gene encodes a putative mobilization (Mob) protein that binds to an origin of transfer (oriT). This Mob protein is similar to other Mob proteins in theta-replicating Leuconostoc plasmids, such as pLCK3, LkipL4701, and pLCK4, and shares ∼80% amino acid sequence identity (31, 35). A putative oriT structure of pMBLT00 possesses highly conserved DNA sequences similar to those of theta-replicating Leuconostoc plasmids (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

ORF17 and ORF18 reside within the third DNA cluster, encoding a serine/threonine phosphatase and an asparagine synthase, facilitating utilization of additional amino acids for the benefit of the host. However, the DNA region containing these putative genes is not homologous to sequences in other Leuconostoc plasmids, suggesting that they are unique and present in this plasmid only for additional amino acid utilization. Interestingly, 3 putative genes (ORF1, ORF12, and ORF16) encoding transposase are located in the boundaries of DNA clusters that could represent the fusion of 3 different plasmids.

Prediction of origin of replication.

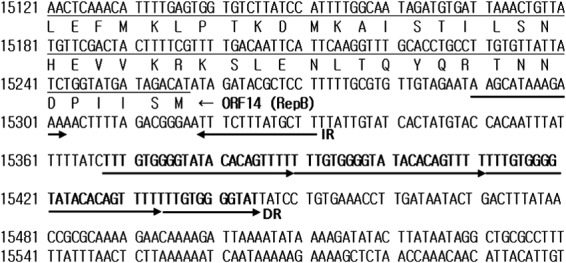

An origin of replication (ori) in pMBLT00 was identified at the upstream region of ORF14, which encodes the RepB protein. Analysis of the ori structure identified an iteron structure with 3.5 contiguous 22-bp direct repeats and an inverted repeat (Fig. 2), which are typical characteristics observed in the ori regions of other plasmids. However, pMBLT00 lacks a double-strand origin replication (dso) sequence, which is an essential sequence in rolling-circle-replicating (RCR) plasmids, suggesting that pMBLT00 replicates via the theta replication mechanism.

Fig 2.

Structure of the proposed origin of replication (ori) in pMBLT00. Shown is the ori gene of an iteron structure containing contiguous 22-bp direct repeats (DR) and an inverted repeat (IR) upstream of the RepB protein.

Theta replication of pMBLT00.

To determine the mechanism by which pMBLT00 replicates, the detection of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) by Southern hybridization was performed, because an ssDNA intermediate is a hallmark of the plasmid RCR mechanism (5). Southern blotting using a DIG-labeled probe (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) revealed that ssDNA intermediates did not accumulate when pMBLT00 was treated with mung bean nuclease (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), indicating that pMBLT00 replicates via the theta replication mechanism but not an RCR mechanism. This result is also consistent with the absence of a dso site within the ori region and the high similarity of the Rep protein in pMBLT00 to other Rep proteins in theta-replicating plasmids.

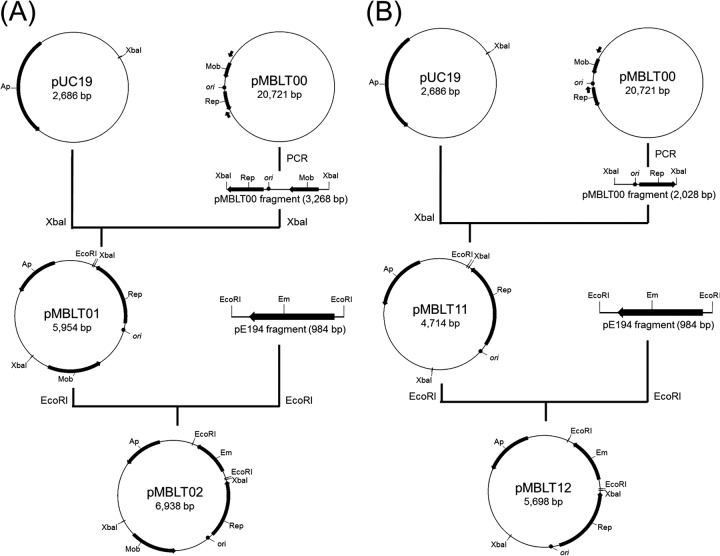

Determination of the minimal replicon of pMBLT00 and construction of a shuttle cloning vector.

On the basis of the sequence analysis and predicted ORFs, 2 minimal replicons of pMBLT00, a 3.3-kb rep-mob gene region (ORF14 and ORF15) and a 2.0-kb rep gene region (ORF14), were cloned into pUC19, resulting in pMBLT01 and pMBLT11, respectively (Fig. 3A and B). An erythromycin resistance gene as a selection marker was then cloned into pMBLT01 and pMBLT11, resulting in pMBLT02 and pMBLT12, respectively (Fig. 3A and B). On the basis of the highest region of nucleotide sequence identity between the putative replicon of pMBLT00 and the pLCK4 replicon from Leuconostoc citreum KM20, 2 vectors were electroporated into Leuconostoc citreum 95 and then tested for their ability to replicate. Although pMBLT02 could replicate in L. citreum 95, pMBLT12 could not, suggesting that the rep-ori-mob region contains an essential minimum replicon and that the RepB protein and the ori region are required for a plasmid replication.

Fig 3.

Determination of a minimal replicon of pMBLT00 and construction of vectors pMBLT02 (A) and pMBLT12 (B).

Host range and segregational stability of pMBLT02.

On the basis of the phylogenetic analysis of various Rep proteins, 5 Leuconostoc strains, 3 Lactobacillus strains, a Lactococcus lactis strain, and a Pediococcus strain were chosen for host range analysis of the pMBLT02 replicon. The pMBLT02 shuttle vector was introduced into L. mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides KCTC 3722 and L. mesenteroides subsp. cremoris KCTC 3529 at frequencies of 4.1 × 103 CFU/μg and 2.5 × 103 CFU/μg, respectively. The plasmid pMBLT02 was introduced into L. citreum 95 and L. lactis KCTC 3528 at frequencies of 1.8 × 103 CFU/μg and 6.9 × 103 CFU/μg, respectively, demonstrating that the pMBLT02 replicon functions in other species of Leuconostoc. Further, pMBLT02 was successfully introduced into L. lactis subsp. lactis KCTC 3926 and Pediococcus acidilactici KCTC 13087 at frequencies of 5.6 × 104 CFU/μg and 1.4 × 103 CFU/μg, respectively, supporting the fact that the pMBLT02 replicon also functions in L. lactis and P. acidilactici. However, pMBLT02 could not be introduced into Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis KCTC 3034, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus KCTC 3635, or Lactobacillus johnsonii KCTC 3141, confirming the incompatibility of the theta replication mechanism for plasmids between Leuconostoc and Lactobacillus. This incompatibility could be explained by the low degree of sequence similarity of conserved protein domains between Rep proteins and the difference of genomic G+C contents (36). The plasmid pMBLT02 was stable over 100 generations in L. citreum 95, without antibiotic selection (more than 80% of recombinant cells were stably maintained).

Application of pMBLT02 for metabolic engineering of L. citreum to enhance d-lactate synthesis.

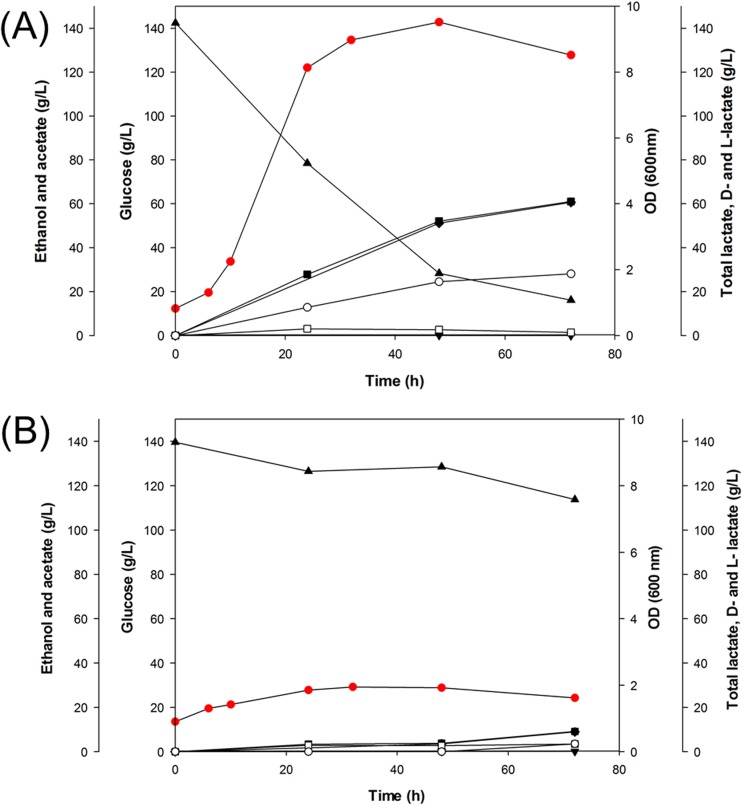

To investigate the usefulness of pMBLT02 as a cloning/expression vector, pMBLT02 was used for metabolic engineering of L. citreum 95 to enhance d-lactate production. For this purpose, a d-ldh gene, encoding d-LDH of L. citreum 95 with its promoter and terminator, was cloned into pMBLT02, generating pMBLT02-dLDH. When the recombinant L. citreum 95(pMBLT02-dLDH) strain was anaerobically cultured in a 2-liter bioreactor with 140 g/liter glucose as a carbon source, the recombinant strain grew to an optical density (OD) of 9.7 and consumed 126 g/liter glucose (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, unlike L. citreum 95(pMBLT02-dLDH) overexpressing d-LDH, a control strain, L. citreum 95(pMBLT02), grew to an OD of only 1.8 and consumed 25 g/liter glucose (Fig. 4B). The significant difference in cell growth between the 2 recombinant strains suggests that the overexpression of d-LDH in L. citreum 95 helps the cell grow in balance by maintaining glucose metabolism and NADH/NAD+ recycling at a high concentration of glucose (140 g/liter) and that pMBLT02 is stable enough to constantly overexpress d-LDH.

Fig 4.

d-Lactate production by recombinant L. citreum strains harboring pMBLT02-dLDH (A) and pMBLT02 as a control (B) in a 2-liter bioreactor with 140 g/liter glucose as the carbon source. Symbols:  , cell growth; ▲, glucose; ■, total lactate; ◆, d-lactate; ▼, l-lactate; □, acetate; ○, ethanol.

, cell growth; ▲, glucose; ■, total lactate; ◆, d-lactate; ▼, l-lactate; □, acetate; ○, ethanol.

Although the d-lactate yield of the engineered L. citreum 95 strain(pMBLT02-dLDH), 48.4% (g d-lactate/g glucose), was less than the yields of other LAB, the optical purity of d-lactate was over 99.9% [g d-lactate/(g l-lactate + g d-lactate)]. Further, production of 61.0 g/liter d-lactate from L. citreum 95(pMBLT02-dLDH) is comparable to the reported highest titer of 60 g/liter d-lactate produced by L. mesenteroides grown on 116.9 g/liter sugar and 44.25 g/liter yeast autolysate (3). These high optical purities and titers make L. citreum 95(pMBLT02-dLDH) an alternative strain for d-lactate production over other LAB that produce d-lactate with optical purities of less than 95%.

In summary, we conclude that the novel plasmid pMBLT00 isolated from Leuconostoc mesenteroides belongs to the theta-replicating plasmids, on the basis of the structure of its ori, absence of a dso sequence, high amino acid sequence similarity of its Rep proteins to the reported sequences of theta-replicating Rep proteins, and absence of ssDNA during replication. The E. coli-Leuconostoc shuttle vector pMBLT02 developed in this study replicated in Lactococcus lactis and Pediococcus, suggesting that the pMBLT00 replicon possesses a wide host range. The L. citreum 95 strain engineered using plasmid pMBLT02, which overexpresses d-LDH, exhibited enhanced production of optically pure d-lactate at a level that was 6 times more than that produced by the control strain. Therefore, the shuttle vector pMBLT02 can serve as a useful and stable plasmid vector for further development of a d- or l-lactate overproduction system in other Leuconostoc strains and Lactococcus lactis, because this vector was successfully introduced into these LAB, and it stably overexpressed d-LDH in L. citreum 95.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the South Korean government (NRF-2011-0030336). This work was also supported by the Intelligent Synthetic Biology Center of the Global Frontier Project funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2011-0031968).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 December 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03291-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. De Vuyst L, Leroy F. 2007. Bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria: production, purification, and food applications. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 13:194–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yáñez R, Belén Moldes A, Alonso JL, Parajó JC. 2003. Production of d(−)-lactic acid from cellulose by simultaneous saccharification and fermentation using Lactobacillus coryniformis subsp. torquens. Biotechnol. Lett. 25:1161–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coelho LF, De Lima CJB, Bernardo MP, Contiero J. 2011. d(−)-Lactic acid production by Leuconostoc mesenteroides B512 using different carbon and nitrogen sources. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 164:1160–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sangproo M, Polyiam P, Jantama SS, Kanchanatawee S, Jantama K. 2012. Metabolic engineering of Klebsiella oxytoca M5a1 to produce optically pure d-lactate in mineral salts medium. Bioresour. Technol. 119:191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Del Solar G, Giraldo R, Ruiz-Echevarria MJ, Espinosa M, Diaz-Orejas R. 1998. Replication and control of circular bacterial plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:434–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Espinosa M, Del Solar G, Rojo F, Alonso JC. 1995. Plasmid rolling circle replication and its control. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 130:111–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pouwels PH, Leer RJ. 1993. Genetics of lactobacilli: plasmids and gene expression. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 64:85–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang TT, Lee BH. 1997. Plasmids in Lactobacillus. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 17:227–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Biet F, Cenatiempo Y, Fremaux C. 1999. Characterization of pFR18, a small cryptic plasmid from Leuconostoc mesenteroides ssp. mesenteroides FR52, and its use as a food grade vector. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179:375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eom H-J, Cho S, Park M, Ji G, Han N. 2010. Characterization of Leuconostoc citreum plasmid pCB18 and development of broad host range shuttle vector for lactic acid bacteria. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 15:946–952 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Park J, Lee M, Jung J, Kim J. 2005. pIH01, a small cryptic plasmid from Leuconostoc citreum IH3. Plasmid 54:184–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jin Q, Jung JY, Kim YJ, Eom HJ, Kim SY, Kim TJ, Han NS. 2009. Production of l-lactate in Leuconostoc citreum via heterologous expression of l-lactate dehydrogenase gene. J. Biotechnol. 144:160–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eom H-J, Seo DM, Han NS. 2007. Selection of psychrotrophic Leuconostoc spp. producing highly active dextransucrase from lactate fermented vegetables. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 117:61–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reference deleted.

- 15. Reference deleted.

- 16. Shivakumar AG, Gryczan TJ, Kozlov YI, Dubnau D. 1980. Organization of the pE194 genome. Mol. Gen. Genet. 179:241–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. O'Sullivan DJ, Klaenhammer TR. 1993. Rapid mini-prep isolation of high-quality plasmid DNA from Lactococcus and Lactobacillus spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:2730–2733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berthier F, Zagorec M, Champomier-Verges M, Ehrlich SD, Morel-Deville F. 1996. Efficient transformation of Lactobacillus sake by electroporation. Microbiology 142:1273–1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carver T, Berriman M, Tivey A, Patel C, Böhme U, Barrell BG, Parkhill J, Rajandream M-A. 2008. Artemis and ACT: viewing, annotating and comparing sequences stored in a relational database. Bioinformatics 24:2672–2676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Besemer J, Borodovsky M. 2005. GeneMark: web software for gene finding in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W451–W454 doi:10.1093/nar/gki487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Fong JH, Geer LY, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, He S, Hurwitz DI, Jackson JD, Ke Z, Lanczycki CJ, Liebert CA, Liu C, Lu F, Lu S, Marchler GH, Mullokandov M, Song JS, Tasneem A, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zhang N, Bryant SH. 2009. CDD: specific functional annotation with the Conserved Domain Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D205–D210 doi:10.1093/nar/gkn845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tatusova TA, Madden TL. 1999. BLAST 2 sequences, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 174:247–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876–4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Benson G. 1999. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:573–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. 2000. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 16:276–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhai Z, Hao Y, Yin S, Luan C, Zhang L, Zhao L, Chen D, Wang O, Luo Y. 2009. Characterization of a novel rolling-circle replication plasmid pYSI8 from Lactobacillus sakei YSI8. Plasmid 62:30–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee JH, O'Sullivan DJ. 2006. Sequence analysis of two cryptic plasmids from Bifidobacterium longum DJO10A and construction of a shuttle cloning vector. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:527–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Makarova K, Slesarev A, Wolf Y, Sorokin A, Mirkin B, Koonin E, Pavlov A, Pavlova N, Karamychev V, Polouchine N, Shakhova V, Grigoriev I, Lou Y, Rohksar D, Lucas S, Huang K, Goodstein DM, Hawkins T, Plengvidhya V, Welker D, Hughes J, Goh Y, Benson A, Baldwin K, Lee JH, Diaz-Muniz I, Dosti B, Smeianov V, Wechter W, Barabote R, Lorca G, Altermann E, Barrangou R, Ganesan B, Xie Y, Rawsthorne H, Tamir D, Parker C, Breidt F, Broadbent J, Hutkins R, O'Sullivan D, Steele J, Unlu G, Saier M, Klaenhammer T, Richardson P, Kozyavkin S, Weimer B, Mills D. 2006. Comparative genomics of the lactic acid bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:15611–15616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim JF, Jeong H, Lee J-S, Choi S-H, Ha M, Hur C-G, Kim J-S, Lee S, Park H-S, Park Y-H, Oh TK. 2008. Complete genome sequence of Leuconostoc citreum KM20. J. Bacteriol. 190:3093–3094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rae TD, Schmidt PJ, Pufahl RA, Culotta VC, O'Halloran TV. 1999. Undetectable intracellular free copper: the requirement of a copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase. Science 284:805–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Alpert CA, Crutz-Le Coq AM, Malleret C, Zagorec M. 2003. Characterization of a theta-type plasmid from Lactobacillus sakei: a potential basis for low-copy-number vectors in lactobacilli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5574–5584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van Kranenburg R, Golic N, Bongers R, Leer RJ, de Vos WM, Siezen RJ, Kleerebezem M. 2005. Functional analysis of three plasmids from Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1223–1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oh HM, Cho YJ, Kim BK, Roe JH, Kang SO, Nahm BH, Jeong G, Han HU, Chun J. 2010. Complete genome sequence analysis of Leuconostoc kimchii IMSNU 11154. J. Bacteriol. 192:3844–3845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee JH, Halgerson JS, Kim JH, O'Sullivan DJ. 2007. Comparative sequence analysis of plasmids from Lactobacillus delbrueckii and construction of a shuttle cloning vector. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:4417–4424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.