Abstract

Molecular tools that can provide an estimate of the in situ growth rate of Geobacter species could improve understanding of dissimilatory metal reduction in a diversity of environments. Whole-genome microarray analyses of a subsurface isolate of Geobacter uraniireducens, grown under a variety of conditions, identified a number of genes that are differentially expressed at different specific growth rates. Expression of two genes encoding ribosomal proteins, rpsC and rplL, was further evaluated with quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) in cells with doubling times ranging from 6.56 h to 89.28 h. Transcript abundance of rpsC correlated best (r2 = 0.90) with specific growth rates. Therefore, expression patterns of rpsC were used to estimate specific growth rates of Geobacter species during an in situ uranium bioremediation field experiment in which acetate was added to the groundwater to promote dissimilatory metal reduction. Initially, increased availability of acetate in the groundwater resulted in higher expression of Geobacter rpsC, and the increase in the number of Geobacter cells estimated with fluorescent in situ hybridization compared well with specific growth rates estimated from levels of in situ rpsC expression. However, in later phases, cell number increases were substantially lower than predicted from rpsC transcript abundance. This change coincided with a bloom of protozoa and increased attachment of Geobacter species to solid phases. These results suggest that monitoring rpsC expression may better reflect the actual rate that Geobacter species are metabolizing and growing during in situ uranium bioremediation than changes in cell abundance.

INTRODUCTION

Understanding how environmental factors control the growth of microorganisms is a major goal in subsurface ecology. However, measuring the growth rate of bacterial populations in situ is challenging, and approaches focused on enumeration of cells in situ are often inaccurate. Not only can unknown proportions of cells be attached to subsurface sediments, cell losses due to predation by protozoa or cell lysis by bacteriophage can also mask true rates of cell multiplication (1, 2).

A number of different techniques have been used to assess microbial growth rates in natural environments. For example, in situ growth rates can be estimated from the incorporation of radiolabeled thymidine or leucine into biomass (3, 4) or by the viable plate count technique (5). However, these approaches require sample incubation. Another approach that does not require sample incubation involves monitoring fluorescently labeled cells that are introduced into the subsurface (6, 7). This approach is limited to those strains that can readily be cultivated in the laboratory (8, 9), and studies have shown that labeled cells can become too diluted once substantial growth begins for results to be reliable (7).

In situ growth rates can also be estimated with the “frequency of dividing cells” (FDC) technique by quantifying the proportion of cells from the environment that are visually dividing (10, 11). This approach assumes that the duration of cell division (Td) and chromosome replication is constant and identical for all individuals within a population and that all of the cells in a population are metabolically active. However, studies have shown that Td values and chromosome replication rates cannot only vary between different species but even within different strains of the same species (12, 13), and cells in stationary or death phase will not be as metabolically active as those in logarithmic phase.

A potentially powerful technique for evaluating the physiological status and rates of activity of microorganisms in the subsurface is quantifying key gene transcripts (14). This approach has been particularly successful for monitoring Geobacteraceae species, which have physiological features that favor their growth in the subsurface (15–17) and have been found to be the predominant organisms associated with the anaerobic in situ bioremediation of groundwater contaminated with organic compounds or uranium (18). In such environments, it has been possible to determine with gene transcript analysis whether Geobacteraceae species are limited for major nutrients, such as ammonium and phosphate, as well as nutrients particularly important to Geobacteraceae species, such as iron (19–23). Furthermore, this method was used to determine whether in situ Geobacteraceae were experiencing oxidative or heavy metal stress (20, 24) and to estimate relative rates of in situ metabolism (25, 26). Here, we report on a method for elucidating in situ growth rates of subsurface Geobacteraceae populations from gene transcript abundance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of Geobacter uraniireducens.

Geobacter uraniireducens strain RF4 (ATCC BAA-1134) was obtained from our laboratory culture collection. Cells were grown with acetate (5 mM) as an electron donor and either fumarate (40 mM), amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide (100 mM), Mn(IV) oxide (20 mM), or sediments collected from a uranium-contaminated aquifer located in Rifle, CO, provided as an electron acceptor. All cultures except the sediment incubations were grown in a bicarbonate-buffered, defined medium (27). All incubations were done in the dark under N2-CO2 (80:20).

For sediment incubations, 40 g of heat-sterilized sediments, 6 ml groundwater, and acetate (5 mM) were added to 60-ml serum bottles in an anaerobic chamber under an N2 atmosphere (28). Cells that served as an inoculum (2%) for sediment incubations were first grown in medium with acetate (5 mM) provided as an electron donor and amorphous Fe(III) oxyhydroxide (100 mM) provided as an electron acceptor. Growing G. uraniireducens in chemostats with soluble electron acceptors such as Fe(III) citrate or fumarate as previously described for Geobacter sulfurreducens (29) was not feasible because G. uraniireducens cannot grow with Fe(III) citrate (30) and fumarate can be fermented when other electron donors are limiting. Therefore, in order to achieve a wide range of specific growth rates, G. uraniireducens was grown in batch cultures with acetate as the electron donor and a variety of electron acceptors [sediment Fe(III) oxides, synthetic Fe(III) or Mn(IV) oxides, or fumarate] at various temperatures (see Fig. S1A to D in the supplemental material). Cell counts and the exponential growth equation [μ = (ln Nf − ln N0)/(tf − t0), where tf is the final time, t0 is the initial time, and N0 and Nf are bacterial abundances at the beginning and end points, respectively) were used to determine specific growth rates for all pure culture studies of G. uraniireducens.

Site and description of field site.

In 2010, a small-scale in situ bioremediation experiment was conducted on the grounds of a former uranium ore processing facility in Rifle, CO, during the months of August to October. This site, designated the Old Rifle site, is part of the Uranium Mill Tailings Remedial Action (UMTRA) program of the U.S. Department of Energy. The test plot was adjacent to a previously studied larger experimental plot at the site (31). The monitoring array consisted of 9 down-gradient and 6 injection wells (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Groundwater for the experiment was collected from well CD-04.

During the field experiment, a concentrated acetate-bromide solution (50/20 mM) mixed with native groundwater was injected into the subsurface to provide approximately 5 mM acetate to the groundwater over the course of 30 days as previously described (31, 32). Bromide was utilized as a nonreactive tracer.

Analytical techniques.

Acetate and fumarate concentrations were determined with an HP series 1100 high-pressure liquid chromatograph (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, CA) with a Fast Acid Analysis column (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), an eluent of 8 mM H2SO4, and an absorbance detection at 210 nm as previously described (31).

Fe(III) reduction in the Fe(III) oxide-grown cultures was monitored by measuring the formation of Fe(II) over time with a ferrozine assay in a split-beam dual-detector spectrophotometer (Spectronic Genosys2; Thermo Electron Corp., Mountain View, CA) at an absorbance of 562 nm after a 1-h extraction with 0.5 N HCl (27, 33). Fe(III) reduction in the sediments was monitored by first measuring Fe(II) in the sediments that could be extracted in 0.5 M HCl after a 1-h incubation with a ferrozine assay (33). The remaining Fe(III) in the sediments that was not HCl extractable was then converted to Fe(II) by the addition of 0.25 M hydroxylamine) (33). After addition of hydroxylamine, samples were incubated for an additional hour and then measured with a ferrozine assay. The percentage of Fe(II) in the sediments was then determined by dividing the HCl-extractable Fe(II) by the hydroxylamine-extractable Fe(II).

Cell numbers from pure cultures were determined by counting acridine orange-stained cells with fluorescence microscopy on a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope (34).

FISH and DAPI counts.

The microbial community was analyzed for Geobacteraceae and total bacteria using fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and nucleic acid staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The number of Geobacteraceae was determined by the number of cells that hybridized to the following probes: GEO3A, GEO3B, and GEO3C (35). Groundwater samples were immediately fixed in a solution consisting of 4% paraformaldehyde–0.5× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Na2HPO4). This solution was vortexed for 5 s before being added to 0.2-μm-pore-size white polycarbonate filters (GTTP; Millipore, Billerica, MA) and washed with 1% Nonidet (Sigma) solution.

Cells were hybridized for 3 h as described previously (36) with a mix of probes GEO3A, GEO3B, and GEO3C in hybridization buffer (0.02 M Tris, 0.9 M NaCl, 0.02% SDS) with a formamide concentration of 30% (vol/vol) at 46°C (37). Filters were washed twice with wash buffer (0.02 M Tris, 0.1 M NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.01% SDS) and incubated at 48°C for 10 min. Filters were washed a final time with filtered, autoclaved, distilled water; placed on slides where they were embedded in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA); and observed with a Nikon epifluorescence microscope. Ten to 20 fields of view for each sample were enumerated; cells stained with DAPI or hybridized to Geobacter probes were both counted for each field. The DAPI and FISH staining efficiency for Rifle groundwater samples ranged from 68 to 79%, and standard deviations among triplicate counts varied between 10 to 30% of the average number of cells.

Extraction of RNA from samples.

For extraction of RNA from batch cultures, 100 ml of G. uraniireducens was first split into 50-ml conical tubes (Falcon) and pelleted by centrifugation at 3,600 × g for 15 min.

RNA was extracted from sediment incubations when 75% of the total iron present in the sediments was reduced to Fe(II). Groundwater and sediment from the incubations (40 g sediment and 6 ml groundwater) were transferred into 50-ml conical tubes (Falcon) and pelleted by centrifugation at 3,600 × g for 15 min. Pellets were then immediately frozen in a dry ice-ethanol bath and stored at −80°C. RNA was extracted from these pellets as previously described (19).

RNA was also extracted from groundwater collected from the U(VI)-contaminated aquifer during the bioremediation field experiment. In order to obtain sufficient biomass from the groundwater for RNA extraction, it was necessary to concentrate 15 liters of groundwater by impact filtration on 293-mm-diameter Supor membrane disc filters with a pore size of 0.2 μm (Pall Life Sciences), which took about 3 min. All filters were placed into whirl-pack bags, flash frozen in a dry ice-ethanol bath, and shipped back to the laboratory, where they were stored at −80°C. RNA was extracted from filters as previously described (19).

High-quality RNA was extracted from the groundwater, sediment, and batch culture samples. In order to ensure that RNA samples were not contaminated with DNA, PCR amplification with primers targeting the 16S rRNA gene was conducted on RNA samples that had not undergone reverse transcription.

Microarray analysis.

The MessageAmp II bacteria kit (Ambion) was used to amplify total RNA (0.5 μg) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Amplified RNA was then chemically labeled with Cy3 (for the control or soluble electron acceptor condition) or Cy5 (for the experimental insoluble condition) dye using the MicroMax ASAP RNA labeling kit (PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

CustomArray 12K oligonucleotide microarrays (Combimatrix, Mukilteo, WA) were designed from the genomic sequence of G. uraniireducens (accession number NZ_AAON00000000). A complete record of all oligonucleotide sequences used and raw and statistically treated data files are available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO data series GSE10920 and GSE12874).

Results were analyzed via LIMMA mixed-model algorithms as previously described (38–41), and multiple oligonucleotide probes were analyzed from each gene (3 or 4 probes per gene). A gene was considered differentially expressed only if at least half of the probes had P values less than or equal to 0.01.

Testing and design of primers.

Before primers for quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) targeting in situ rpsC and proC mRNA transcripts could be designed, cDNA libraries were constructed with products amplified from RNA extracted from groundwater with the degenerate PCR primer sets, Geo_rpsC200f/640r and Geo_proC55f/460r (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). These degenerate primers were designed from nucleotide and amino acid sequences extracted from the genomes of the following Geobacter species: G. sulfurreducens, G. metallireducens, G. daltonii, G. remediiphilus, G. uraniireducens, G. lovleyi, and G. bemidjiensis. Genome sequence data were obtained from the DOE Joint Genome Institute (JGI) website (www.jgi.doe.gov). Products from these degenerate primer sets were cloned into the TOPO TA cloning vector, version M (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). One hundred plasmid inserts from both the rpsC and proC cDNA libraries were sequenced with the M13F primer at the University of Massachusetts Sequencing Facility. A Geobacter rpsC sequence accounted for 85% of the sequences in the rpsC cDNA library, and a Geobacter proC sequence accounted for 90% of the proC cDNA library. Both of these dominant sequences were used to design qRT-PCR primers specific for in situ Geobacter species present during bioremediation.

All qRT-PCR primers were designed according to the manufacturer's specifications (Applied Biosystems) and had amplicon sizes ranging from 100 to 200 bp. Pure culture primers designed for qRT-PCR targeted only G. uraniireducens cells. GU_rpsC178f/245r, GU_rplL66f/136r, and GU_proC263f/367r primer sets were used to quantify rpsC, rplL, and proC mRNA transcripts from G. uraniireducens, and Geo_rpsC50f/147r and Geo_proC13f/140r targeted rpsC and proC cDNA made from RNA extracted from groundwater (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

The reference gene, proC, which appears to be constitutively expressed by Geobacteraceae species in pure cultures and in the environment (22, 24, 42) and was not differentially expressed in any of the microarray experiments from this study, was selected as an external control. The gene proC encodes pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase, which is involved in arginine and proline metabolism. In order to further confirm the fact that proC expression is constitutive, proC mRNA transcript abundance was compared to biomass harvested from G. uraniireducens cultures grown at four different temperatures with acetate as the electron donor and fumarate as the electron acceptor. All four of these cultures were harvested at an optical density of 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3 (biomass of ca. 49 mg protein/liter), and the number of proC mRNA transcripts in these samples varied only from 1.66 × 105 to 3.34 × 105.

Expression by one growth-related and one reference gene was monitored in this study, and results indicated that mRNA transcripts from these genes could be used to reliably predict in situ growth. However, in order to better understand total cell activity, future studies might want to target expression profiles of more genes.

PCR amplification parameters and clone library construction.

A DuraScript enhanced avian RT single-strand synthesis kit (Sigma) was used to generate cDNA as previously described (19). Previously described parameters were used to amplify genes of interest with degenerate primers (43).

For construction of 16S rRNA gene clone libraries, gene fragments were first amplified by PCR with the following primer sets: 8F (44) with 519R (45) and 338F (46) with 907R (45). PCR products were purified with a gel extraction kit (Qiagen), and clone libraries were constructed with a TOPO TA cloning kit, version M (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantification of gene expression by qRT-PCR.

Once the appropriate cDNA fragments were generated by RT-PCR, quantitative PCR amplification and detection were performed with the 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Optimal qRT-PCR conditions were determined using the manufacturer's guidelines: 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min.

Each PCR mixture consisted of a total volume of 25 μl and contained 1.5 μl of the appropriate primers (stock concentrations, 15 μM), 5 ng cDNA, and 12.5 μl Power SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). Standard curves covering 8 orders of magnitude were constructed with serial dilutions of known amounts of purified cDNA quantified with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer at an absorbance of 260 nm.

The qPCR efficiency (95% to 99%) was calculated based on the slope of the standard curve. All qPCR assays had triplicate biological and technical replicates. Thermal cycling parameters consisted of an activation step at 50°C for 2 min, a denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, and 50 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. This was followed by the construction of a dissociation curve through increasing the temperature from 60°C to 95°C at a ramp rate of 2%. A single predominant peak was observed in the dissociation curve of each gene, supporting the specificity of the PCR product.

Phylogenetic analysis.

16S rRNA and functional gene sequences were compared to GenBank nucleotide and protein databases with the blastn and blastx algorithms (47).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of rpsC, proC, and 16S rRNA genes amplified from the uranium-contaminated aquifer have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers FJ042710 to FJ042726.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of growth rate-related genes with microarray analysis.

G. uraniireducens, an isolate from the Rifle study site, is closely related to Geobacter species that predominate during in situ uranium bioremediation at the site (30). Whole-genome scale data on transcript abundance during growth with fumarate as the electron acceptor versus growth on natural Fe(III) oxides in sterile subsurface sediments (20) or laboratory-synthesized Fe(III) and Mn(IV) oxides is available (GEO data series GSE10920 and GSE12874). At its optimal temperature of 30°C, G. uraniireducens grew fastest with fumarate provided as an electron acceptor and slowest with sediments provided as an electron acceptor (Table 1).

Table 1.

Growth rate constants and generation times calculated for G. uraniireducens cells growing under a variety of conditionsa

| Electron acceptor | Growth temp (°C) | Growth rate constant (μ, h−1) | Doubling time (generations, h−1) | rpsC/proC transcript ratio | rplL/proC transcript ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sediment | 18 | 0.014 | 49.5 | 1.71 ± 0.08 | 0.17 ± 0.06 |

| Sediment | 30 | 0.013 | 50.1 | 1.58 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.02 |

| Sediment | 37 | 0.007 | 89.28 | 0.26 ± 0.11 | 0.30 ± 0.21 |

| Fe(III)-oxide | 30 | 0.037 | 18.5 | 12.21 ± 1.63 | 8.18 ± 6.56 |

| Mn(IV)-oxide | 30 | 0.04 | 17.4 | 16.8 ± 2.97 | 10.9 ± 6.77 |

| Fumarate | 10 | 0.018 | 38.52 | 3.22 ± 1.57 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| Fumarate | 15 | 0.026 | 26.72 | 6.93 ± 3.40 | 41.9 ± 40.6 |

| Fumarate | 20 | 0.038 | 18.28 | 28.3 ± 9.58 | 4.34 ± 2.75 |

| Fumarate | 30 | 0.106 | 6.56 | 55.6 ± 17.4 | 15.3 ± 2.72 |

Electron acceptor and/or temperature were varied.

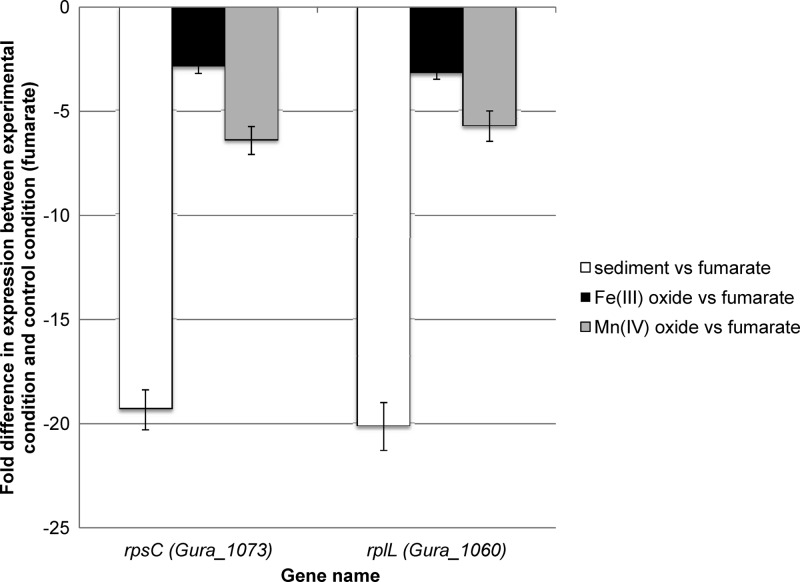

A number of genes involved in protein synthesis had significantly lower transcript abundance at the lower growth rates (see Tables S2 to S4 in the supplemental material). Of these, 52 were less abundant under all three slow-growth conditions. Two of these genes, rpsC and rplL, which code for ribosomal proteins S3 and L7/L12 (Fig. 1), were chosen for further study because their expression levels have also been shown to be linked to specific growth rates in other microorganisms (48–50).

Fig 1.

Microarray results from experiments comparing three different experimental conditions (G. uraniireducens cells grown with Rifle sediment, Fe(III) oxide, or Mn(IV) oxide provided as the electron acceptor) to the control condition (G. uraniireducens cells grown with fumarate provided as the electron acceptor) (P value cutoff of ≤0.01). Transcript levels for both rpsC and rplL were significantly downregulated in all three microarray experiments (indicated by negative fold change in the figure). Triplicate biological and duplicate technical replicates were done for all three microarray experiments.

Correlation between specific growth rate and transcript abundance.

In order to achieve an even wider range of growth rates, G. uraniireducens was grown at various temperatures with a variety of electron acceptors [sediment Fe(III) oxides, synthetic Fe(III) or Mn(IV) oxides, or fumarate] (Table 1; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Specific growth rates ranged from 0.007 h−1 to 0.106 h−1. The specific growth rate of G. uraniireducens increased with temperature in fumarate-grown cultures, but this same increase was not observed in sediment-grown cells. The fact that growth was slower in sediment cultures grown at 30°C suggests that some factor other than temperature, possibly the need to search for Fe(III) oxide sources (51), can limit growth in sediments. The decrease in specific growth rate in sediments observed at 37°C can be explained by the fact that this temperature is above G. uraniireducens ' optimal growth range (30).

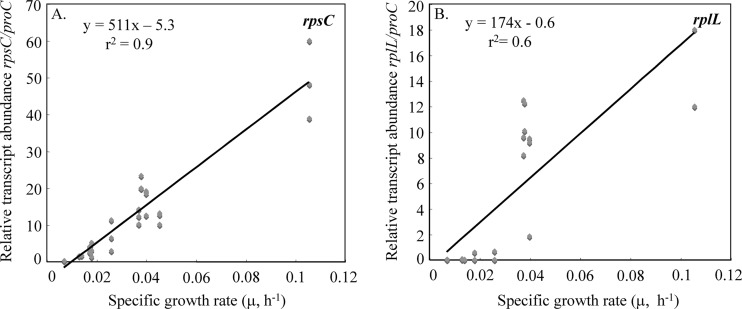

Despite the variety of growth conditions, the number of mRNA transcripts from both genes normalized against the number of proC transcripts (Table 1) was directly correlated with specific growth rate (Fig. 2). The correlation between the rpsC/proC ratio and the specific growth rate was much better than it was for the rplL/proC ratio and the specific growth rate (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

The number of rpsC (A) and rplL (B) mRNA transcripts normalized against the number of proC mRNA transcripts expressed by G. uraniireducens at a wide range of growth rates. Triplicate biological and technical replicates were done for all specific growth rates.

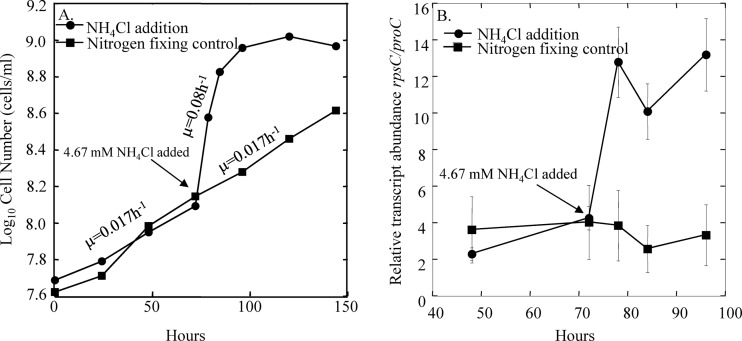

The specific growth rate of G. uraniireducens could also be manipulated by controlling the availability of ammonium. The addition of ammonium to cultures that were previously growing under nitrogen-fixing conditions greatly accelerated the specific growth rate (Fig. 3A). Increased growth was associated with a dramatic increase in rpsC transcript abundance (Fig. 3B). Under nitrogen-fixing conditions, the specific growth rate was approximately 0.017 h−1 which, according to the equation from Fig. 2A (y = 511x − 5.3), should yield a normalized transcript abundance value of 3.5 and compares well with the value of 3.6 that was observed. These results further suggested that the abundance of rpsC could be used to estimate specific growth rates of G. uraniireducens under changing environmental conditions.

Fig 3.

(A) The number of G. uraniireducens cells in cultures with acetate (5 mM) provided as the electron donor and fumarate (40 mM) provided as the electron acceptor under nitrogen-limiting (no NH4+) or non-nitrogen-limiting (4.67 mM NH4+) conditions; (B) the number of rpsC mRNA transcripts normalized against the number of proC mRNA transcripts expressed by G. uraniireducens cells under nitrogen-limiting or non-nitrogen-limiting conditions. Triplicate biological and technical replicates were done for all samples.

Evaluation of in situ specific growth rate in the subsurface.

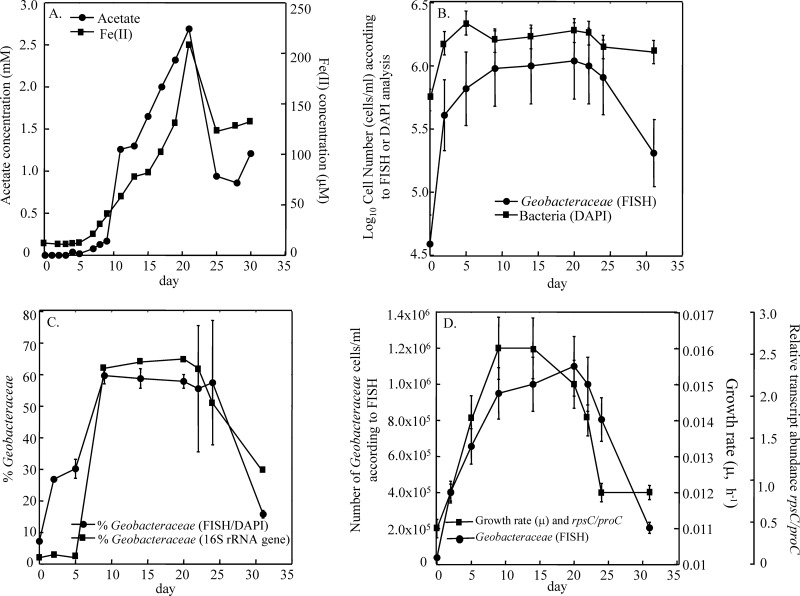

The 2010 in situ uranium bioremediation field experiment conducted in Rifle provided an excellent opportunity to determine whether the abundance of rpsC transcripts might be a good indicator of the relative specific growth rates of Geobacteraceae species in the subsurface. As previously observed in acetate amendment studies at the site (26, 31), the addition of acetate resulted in an accumulation of Fe(II) (Fig. 4A) and an increase in the number of Geobacteraceae species (Fig. 4B), consistent with the expected stimulation of dissimilatory metal reduction. In contrast to the increase in Geobacteraceae species, there appeared to be little net growth of other microorganisms, as cells labeled with Geobacteraceae-specific probes accounted for most of the increase in cells that was detected with DAPI staining (Fig. 4B). The relative abundance of Geobacteraceae species estimated from analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences further confirmed the specific stimulation of the growth of Geobacteraceae species (Fig. 4C and Table S5 in the supplemental material). The majority of 16S rRNA gene sequences recovered from the samples after day 9 were Geobacteraceae species, specifically Geobacter bemidjiensis (see Tables S5 and S6 in the supplemental material), indicating that the Geobacteraceae enumerated with FISH probes were primarily from the genus Geobacter. When acetate concentrations in the subsurface started to decline after day 21, Fe(II) concentrations also went down, and this was accompanied by a decrease in the number of Geobacter cells and their abundance relative to other bacterial species (Fig. 4B).

Fig 4.

Growth of Geobacteraceae in response to acetate availability during the uranium bioremediation field experiment conducted at Rifle in 2010. (A) Acetate and Fe(II) concentrations in groundwater collected during uranium bioremediation; (B) number of Geobacteraceae in the groundwater estimated by direct counts of cells labeled with Geobacteraceae-specific FISH probes and total bacterial cells estimated with general DAPI staining; (C) proportion of Geobacteraceae in the groundwater estimated by comparing direct counts of cells labeled with Geobacteraceae-specific FISH probes with general DAPI staining of all cells versus proportion of Geobacteraceae found in 16S rRNA gene clone libraries; (D) number of Geobacteraceae rpsC mRNA transcripts normalized against the number of proC mRNA transcripts plotted against the number of Geobacteraceae cells/ml estimated by FISH in the groundwater. Each point is an average of triplicate determinations, and error bars represent standard deviations. Growth rate constants (μ) were calculated from the following equation: y = 511x − 5.3.

Specific growth rates of in situ Geobacter species were estimated from rpsC transcript abundance. It was assumed that there was a correlation between transcript abundance of rpsC in the subsurface isolate of G. uraniireducens and specific growth rate of the in situ Geobacter population (Fig. 2A). Specific growth rates for the in situ Geobacter species were calculated using the equation in Fig. 2A (y = 511x − 5.3) and ranged from 0.014 to 0.016 h−1 (Fig. 4D). These estimated specific growth rates were comparable to the specific growth rate of 0.014 h−1 for G. uraniireducens from laboratory incubations in acetate-amended sediments.

Estimated specific growth rates increased 45% with the addition of acetate, plateaued around day 9, and then started to decline around day 20 to a rate near that observed when acetate amendments were first started (Fig. 4D). This same trend was observed when Geobacter cell numbers were monitored over time with FISH. Immediately following the addition of acetate, there was a dramatic increase in cell numbers up to day 9 (Fig. 4D). Assuming logarithmic growth, the increase in cell numbers in the first 9 days (9.11 × 105 cells/ml) yielded a specific growth rate of 0.0148 h−1, which is comparable to the maximum specific growth rate estimated by rpsC transcript numbers during this period (Fig. 4D). Between days 9 and 20, the rate of Geobacter cell number increase was noticeably lower. The estimated specific growth rate from cell numbers during this phase was 0.0006 h−1, much lower than the specific growth rates of 0.015 to 0.016 h−1 estimated from rpsC transcript abundance. After day 20, numbers of Geobacter in the groundwater started to decline even though the specific growth rate estimated from rpsC transcripts was higher than the specific growth rate at time zero.

A major factor contributing to the discrepancy between estimated specific growth rates and changes in cell number after day 9 may have been a bloom in protozoa grazing on Geobacter species. Studies at the Rifle site have shown that protozoa become abundant in the groundwater when dissimilatory metal reduction is stimulated by the addition of acetate (64). The increase in protozoan abundance is significant because protozoa can exploit substantial quantities of bacterial biomass production (52), and grazing can significantly stimulate microbial metabolic activity and growth (53, 54).

Another consideration is that as Fe(III) oxides are depleted at the Rifle site, the Geobacter populations shift from one that is ca. 90% planktonic to one in which most of the cells attach to the sediments (S. Dar, unpublished data). The continued decline in the number of planktonic Geobacter cells during the later phases of the field experiment may reflect this. Furthermore, there may be other factors contributing to cell loss. The estimated Geobacter-specific growth rates prior to acetate additions were ca. 70% of the maximum estimated specific growth rates during acetate additions, yet cell numbers were relatively low. Estimates of growth rate in the subsurface are likely to represent an average of a wide range of growth rates of cells exposed to different microenvironments, as previously noted in biofilms (55).

Implications.

These results suggest that monitoring expression of rpsC can provide insight into specific growth rates of subsurface Geobacter species, even under situations where predation is equal or higher than production of new cells. The ability to estimate specific growth rates in the subsurface during the bioremediation of metals is particularly important, because the goal may not always be to maximize the specific growth rate or even the overall rate of metal reduction. For example, it may be desirable to maintain an active but slowly respiring population of Geobacter species that will effectively reduce U(VI) as it enters the acetate injection zone, without rapidly depleting the Fe(III) oxides needed to maintain their growth in the subsurface.

The approach described here may also be useful for monitoring the growth of Geobacter species in a diversity of other environments in which they play an important role, including anaerobic soils and sediments (18), electrodes harvesting current (56), and some methanogenic environments (18). It seems likely that a similar approach may also be useful for monitoring the growth of other subsurface microorganisms, such as the Dehalococcoides species involved in reductive dechlorination (57), or to monitor the growth of microorganisms added to the subsurface to promote bioremediation (58–60). Furthermore, as the ability to predictively model the growth of subsurface microorganisms at the genome scale advances (16, 17, 61–63), it will be increasingly important to have better methods for monitoring key aspects of microbial physiology, such as growth rate for model validation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research at the University of Massachusetts was funded by the Office of Science (BER), U.S. Department of Energy, award no. DE-SC0004080 and DE-SC0004814, and Cooperative Agreement no. DE-FC02-02ER63446. Additional support for field research was equally supported through the Integrated Field Research Challenge Site (IFRC) at Rifle, CO, and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory's Sustainable Systems Scientific Focus Area. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, funded the work under contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; operated by the University of California).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 December 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03263-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Caron DA, Worden AZ, Countway PD, Demir E, Heidelberg KB. 2009. Protists are microbes too: a perspective. ISME J. 3:4–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tuomi P, Kuuppo P. 1999. Viral lysis and grazing loss of bacteria in nutrient- and carbon-manipulated brackish water enclosures. J. Plankton Res. 21:923–937 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fuhrman JA, Azam F. 1982. Thymidine incorporation as a measure of heterotrophic bacterioplankton production in marine surface waters—evaluation and field results. Marine Biol. 66:109–120 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baath E. 1998. Growth rates of bacterial communities in soils at varying pH: a comparison of the thymidine and leucine incorporation techniques. Microb. Ecol. 36:316–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Staley JT, Konopka A. 1985. Measurement of in situ activities of nonphotosynthetic microorganisms in aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 39:321–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fuller ME, Mailloux BJ, Streger SH, Hall JA, Zhang PF, Kovacik WP, Vainberg S, Johnson WP, Onstott TC, DeFlaun MF. 2004. Application of a vital fluorescent staining method for simultaneous, near-real-time concentration monitoring of two bacterial strains in an Atlantic Coastal Plain aquifer in Oyster, Virginia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1680–1687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fuller ME, Streger SH, Rothmel RK, Mailloux BJ, Hall JA, Onstott TC, Fredrickson JK, Balkwill DL, DeFlaun MF. 2000. Development of a vital fluorescent staining method for monitoring bacterial transport in subsurface environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4486–4496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Breeuwer P, Abee T. 2000. Assessment of viability of microorganisms employing fluorescence techniques. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 55:193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Breeuwer P, Drocourt JL, Rombouts FM, Abee T. 1996. A novel method for continuous determination of the intracellular pH in bacteria with the internally conjugated fluorescent probe 5 (and 6-)-carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:178–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamamoto Y, Shiah FK. 2010. Relationship between cell growth and frequency of dividing cells of Microcystis aeruginosa. Plankton Benthos Res. 5:131–135 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harvey RW, George LH. 1987. Growth determinations for unattached bacteria in a contaminated aquifer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:2992–2996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tsujimura S. 2003. Application of the frequency of dividing cells technique to estimate the in situ growth of Microcystis (cyanobacteria). Freshwater Biol. 48:2009–2024 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burbage CD, Binder BJ. 2007. Relationship between cell cycle and light-limited growth rate in oceanic Prochlorococcus (MIT9312) and Synechococcus (WH8103) (cyanobacteria). J. Phycol. 43:266–274 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lovley DR. 2003. Cleaning up with genomics: applying molecular biology to bioremediation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1:35–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lin B, Westerhoff HV, Roling WF. 2009. How Geobacteraceae may dominate subsurface biodegradation: physiology of Geobacter metallireducens in slow-growth habitat-simulating retentostats. Environ. Microbiol. 11:2425–2433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mahadevan R, Palsson BO, Lovley DR. 2011. In situ to in silico and back: elucidating the physiology and ecology of Geobacter spp. using genome-scale modelling. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9:39–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhuang K, Izallalen M, Mouser P, Richter H, Risso C, Mahadevan R, Lovley DR. 2011. Genome-scale dynamic modeling of the competition between Rhodoferax and Geobacter in anoxic subsurface environments. ISME J. 5:305–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lovley DR, Ueki T, Zhang T, Malvankar NS, Shrestha PM, Flanagan KA, Aklujkar M, Butler JE, Giloteaux L, Rotaru AE, Holmes DE, Franks AE, Orellana R, Risso C, Nevin KP. 2011. Geobacter: the microbe electric's physiology, ecology, and practical applications. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 59:1–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Holmes DE, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2004. In situ expression of nifD in Geobacteraceae in subsurface sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:7251–7259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holmes DE, O'Neil RA, Chavan MA, N′Guessan LA, Vrionis HA, Perpetua LA, Larrahondo MJ, DiDonato R, Liu A, Lovley DR. 2009. Transcriptome of Geobacter uraniireducens growing in uranium-contaminated subsurface sediments. ISME J. 3:216–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mouser PJ, N′Guessan AL, Elifantz H, Holmes DE, Williams KH, Wilkins MJ, Long PE, Lovley DR. 2009. Influence of heterogeneous ammonium availability on bacterial community structure and the expression of nitrogen fixation and ammonium transporter genes during in situ bioremediation of uranium-contaminated groundwater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43:4386–4392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Neil RA, Holmes DE, Coppi MV, Adams LA, Larrahondo MJ, Ward JE, Nevin KP, Woodard TL, Vrionis HA, N′Guessan AL, Lovley DR. 2008. Gene transcript analysis of assimilatory iron limitation in Geobacteraceae during groundwater bioremediation. Environ. Microbiol. 10:1218–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. N′Guessan AL, Elifantz H, Nevin KP, Mouser PJ, Methe B, Woodard TL, Manley K, Williams KH, Wilkins MJ, Larsen JT, Long PE, Lovley DR. 2010. Molecular analysis of phosphate limitation in Geobacteraceae during the bioremediation of a uranium-contaminated aquifer. ISME J. 4:253–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mouser PJ, Holmes DE, Perpetua LA, DiDonato R, Postier B, Liu A, Lovley DR. 2009. Quantifying expression of Geobacter spp. oxidative stress genes in pure culture and during in situ uranium bioremediation. ISME J. 3:454–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Holmes DE, Mester T, O'Neil RA, Perpetua LA, Larrahondo MJ, Glaven R, Sharma ML, Ward JE, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2008. Genes for two multicopper proteins required for Fe(III) oxide reduction in Geobacter sulfurreducens have different expression patterns both in the subsurface and on energy-harvesting electrodes. Microbiology 154:1422–1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holmes DE, Nevin KP, O'Neil RA, Ward JE, Adams LA, Woodard TL, Vrionis HA, Lovley DR. 2005. Potential for quantifying expression of the Geobacteraceae citrate synthase gene to assess the activity of Geobacteraceae in the subsurface and on current harvesting electrodes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:6870–6877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lovley DR, Phillips EJP. 1988. Novel mode of microbial energy metabolism—organic carbon oxidation coupled to dissimilatory reduction of iron or manganese. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1472–1480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2000. Lack of production of electron-shuttling compounds or solubilization of Fe(III) during reduction of insoluble Fe(III) oxide by Geobacter metallireducens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2248–2251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Esteve-Nunez A, Rothermich M, Sharma M, Lovley D. 2005. Growth of Geobacter sulfurreducens under nutrient-limiting conditions in continuous culture. Environ. Microbiol. 7:641–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shelobolina ES, Vrionis HA, Findlay RH, Lovley DR. 2008. Geobacter uraniireducens sp. nov., isolated from subsurface sediment undergoing uranium bioremediation. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58:1075–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Anderson RT, Vrionis HA, Ortiz-Bernad I, Resch CT, Long PE, Dayvault R, Karp K, Marutzky S, Metzler DR, Peacock A, White DC, Lowe M, Lovley DR. 2003. Stimulating the in situ activity of Geobacter species to remove uranium from the groundwater of a uranium-contaminated aquifer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5884–5891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Williams KH, Long PE, Davis JA, Wilkins MJ, N′Guessan AL, Steefel CI, Yang L, Newcomer D, Spane FA, Kerkhof LJ, McGuinness L, Dayvault R, Lovley DR. 2011. Acetate availability and its influence on sustainable bioremediation of uranium-contaminated groundwater. Geomicrobiol. J. 28:519–539 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lovley DR, Stolz JF, Nord GL, Phillips EJP. 1987. Anaerobic production of magnetite by a dissimilatory iron-reducing microorganism. Nature 330:252–254 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Coates JD, Ellis DJ, Blunt-Harris EL, Gaw CV, Roden EE, Lovley DR. 1998. Recovery of humic-reducing bacteria from a diversity of environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1504–1509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Richter H, Lanthier M, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. 2007. Lack of electricity production by Pelobacter carbinolicus indicates that the capacity for Fe(III) oxide reduction does not necessarily confer electron transfer ability to fuel cell anodes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:5347–5353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lemke MJ, McNamara CJ, Leff LG. 1997. Comparison of methods for the concentration of bacterioplankton for in situ hybridization. J. Microbiol. Meth. 29:23–29 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pernthaler J, Glockner FO, Schonhuber W, Amann R. 2001. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Methods Microbiol. 30:207–226 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate—a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B Met. 57:289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Postier B, Didonato R, Jr, Nevin KP, Liu A, Frank B, Lovley D, Methe BA. 2008. Benefits of in-situ synthesized microarrays for analysis of gene expression in understudied microorganisms. J. Microbiol. Methods 74:26–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smyth GK. 2004. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3:Article3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smyth GK, Speed T. 2003. Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods 31:265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Holmes DE, Chaudhuri SK, Nevin KP, Mehta T, Methe BA, Liu A, Ward JE, Woodard TL, Webster J, Lovley DR. 2006. Microarray and genetic analysis of electron transfer to electrodes in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Environ. Microbiol. 8:1805–1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Holmes DE, O'Neil RA, Vrionis HA, N′Guessan LA, Ortiz-Bernad I, Larrahondo MJ, Adams LA, Ward JA, Nicoll JS, Nevin KP, Chavan MA, Johnson JP, Long PE, Lovley DR. 2007. Subsurface clade of Geobacteraceae that predominates in a diversity of Fe(III)-reducing subsurface environments. ISME J. 1:663–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eden PA, Schmidt TM, Blakemore RP, Pace NR. 1991. Phylogenetic analysis of Aquaspirillum magnetotacticum using polymerase chain reaction-amplified 16S ribosomal RNA-specific DNA. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:324–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lane DJ, Pace B, Olsen GJ, Stahl DA, Sogin ML, Pace NR. 1985. Rapid determination of 16S ribosomal RNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82:6955–6959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Amann RI, Binder BJ, Olson RJ, Chisholm SW, Devereux R, Stahl DA. 1990. Combination of 16S ribosomal RNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1919–1925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Huang SC, Panagiotidis CA, Canellakis ES. 1990. Transcriptional effects of polyamines on ribosomal proteins and on polyamine-synthesizing enzymes in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:3464–3468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Milne AN, Mak WWN, Wong JTF. 1975. Variation of ribosomal proteins with bacterial growth rate. J. Bacteriol. 122:89–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sarmientos P, Cashel M. 1983. Carbon starvation and growth rate-dependent regulation of the Escherichia coli ribosomal RNA promoters—differential control of dual promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Biol. 80:7010–7013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Childers SE, Ciufo S, Lovley DR. 2002. Geobacter metallireducens accesses insoluble Fe(III) oxide by chemotaxis. Nature 416:767–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fenchel T. 1982. Ecology of heterotrophic microflagellates. II. Bioenergetics and growth. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 8:225–231 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Biagini GA, Finlay BJ, Lloyd D. 1998. Protozoan stimulation of anaerobic microbial activity: enhancement of the rate of terminal decomposition of organic matter. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 27:1–8 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Strauss EA, Dodds WK. 1997. Influence of protozoa and nutrient availability on nitrification rates in subsurface sediments. Microb. Ecol. 34:155–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Poulsen LK, Ballard G, Stahl DA. 1993. Use of rRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization for measuring the activity of single cells in young and established biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1354–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lovley DR. 2012. Electromicrobiology. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 66:391–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lee PKH, Macbeth TW, Sorenson KS, Deeb RA, Alvarez-Cohen L. 2008. Quantifying genes and transcripts to assess the in situ physiology of “Dehalococcoides” spp. in a trichloroethene-contaminated groundwater site. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2728–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Amos BK, Sung Y, Fletcher KE, Gentry TJ, Wu WM, Criddle CS, Zhou J, Loffler FE. 2007. Detection and quantification of Geobacter lovleyi strain SZ: implications for bioremediation at tetrachloroethene- and uranium-impacted sites. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:6898–6904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Aulenta F, Potalivo M, Majone M, Papini MP, Tandoi V. 2006. Anaerobic bioremediation of groundwater containing a mixture of 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane and chloroethenes. Biodegradation 17:193–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Major DW, McMaster ML, Cox EE, Edwards EA, Dworatzek SM, Hendrickson ER, Starr MG, Payne JA, Buonamici LW. 2002. Field demonstration of successful bioaugmentation to achieve dechlorination of tetrachloroethene to ethene. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36:5106–5116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Scheibe TD, Mahadevan R, Fang Y, Garg S, Long PE, Lovley DR. 2009. Coupling a genome-scale metabolic model with a reactive transport model to describe in situ uranium bioremediation. Microb. Biotechnol. 2:274–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fang Y, Scheibe TD, Mahadevan R, Garg S, Long PE, Lovley DR. 2011. Direct coupling of a genome-scale microbial in silico model and a groundwater reactive transport model. J. Contaminant Hydrol. 122:96–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Barlett M, Zhuang K, Mahadevan R, Lovley D. 2012. Integrative analysis of Geobacter spp. and sulfate-reducing bacteria during uranium bioremediation. Biogeosciences 9:1033–1040 [Google Scholar]

- 64. Holmes DE, Giloteaux L, Williams KH, Wrighton KC, Wilkins MJ, Thompson CA, Roper TJ, Long PE, Lovley DR. Enrichment of specific protozoan populations during in situ bioremediation of uranium-contaminated groundwater. ISME J., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.