Abstract

Proteus mirabilis, a leading cause of catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CaUTI), differentiates into swarm cells that migrate across catheter surfaces and medium solidified with 1.5% agar. While many genes and nutrient requirements involved in the swarming process have been identified, few studies have addressed the signals that promote initiation of swarming following initial contact with a surface. In this study, we show that P. mirabilis CaUTI isolates initiate swarming in response to specific nutrients and environmental cues. Thirty-three compounds, including amino acids, polyamines, fatty acids, and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates, were tested for the ability to promote swarming when added to normally nonpermissive media. l-Arginine, l-glutamine, dl-histidine, malate, and dl-ornithine promoted swarming on several types of media without enhancing swimming motility or growth rate. Testing of isogenic mutants revealed that swarming in response to the cues required putrescine biosynthesis and pathways involved in amino acid metabolism. Furthermore, excess glutamine was found to be a strict requirement for swarming on normal swarm agar in addition to being a swarming cue under normally nonpermissive conditions. We thus conclude that initiation of swarming occurs in response to specific cues and that manipulating concentrations of key nutrient cues can signal whether or not a particular environment is permissive for swarming.

INTRODUCTION

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common hospital-associated infections, with an estimated 424,000 cases and 13,000 UTI-related deaths in U.S. hospitals in 2002 (1). In addition, placement of an indwelling catheter predisposes individuals to the development of catheter-associated UTI (CaUTI), the most common type of nosocomial infection (2, 3). CaUTI is generally thought to be caused by self-inoculation of the catheter (4). Once bacteria have colonized the catheter, motile species can rapidly traverse the catheter surface to reach the bladder and potentially establish a UTI.

The dimorphic, motile, Gram-negative bacterium Proteus mirabilis is one of the leading causative agents of CaUTI, responsible for up to 44% of these infections (3, 5–7). P. mirabilis infections frequently develop into cystitis and pyelonephritis and can be further complicated by catheter encrustation and formation of urinary stones (8, 9). P. mirabilis has fascinated scientists for over 125 years for its ability to differentiate from short swimmer cells into elongated swarm cells that express hundreds to thousands of flagella (10). These swarm cells interact intimately with one another to form multicellular rafts (11–13). In the context of CaUTI, P. mirabilis utilizes this process of swarming to migrate along the catheter surface, gaining entry to the bladder and causing painful and sometimes serious complications (3, 14).

Swarming is distinct from swimming motility in that it refers to multicellular flagellum-mediated migration across a surface rather than movement in liquid medium or through soft agar. P. mirabilis swarming also requires differentiation into a distinct swarm cell morphology. Regulation of the swarm cell differentiation process is not fully understood, but many components have been investigated and recently reviewed (15–17). For instance, surface contact and the resulting inhibition of flagellar rotation are critical for swarm cell differentiation in most strains (18), and a combination of surface contact and changes in cell wall and lipopolysaccharide composition ultimately promote activity of the flagellar master regulator FlhD2C2 and expression of the flagellar genes (18–22). Factors that impact temporal regulation of swarming, swarm speed, or overall swarm pattern have also been identified, such as putrescine and certain fatty acids (23, 24). There is also an intimate connection between swarming and energy metabolism, as normal swarming requires pathways that generate pyruvate and a complete oxidative tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, even though P. mirabilis appears to use anaerobic respiration during swarming (25–27). P. mirabilis swarming is also influenced by aeration, growth rate, cell density, and the concentration of NaCl or other electrolytes (28–31).

Despite these advances in the understanding of swarming, information is limited regarding whether or not P. mirabilis uses nutrient conditions or environmental cues as specific signals to initiate swarming following contact with a solid surface. An early investigation of nutritional requirements for swarming showed that a mixture of 22 amino acids promoted swarming on a normally nonpermissive minimal medium and that glutamic acid, aspartic acid, serine, proline, alanine, asparagine, and glutamine were each sufficient to promote swarming when added individually to the base medium (29). That study also found that these same amino acids decreased the generation time in liquid culture, suggesting a correlation between swarming and growth rate. A more recent investigation into potential swarming cues for a P. mirabilis UTI isolate revealed that the addition of glutamine to a different formulation of nonpermissive minimal medium allowed for initiation of swarming, yet 19 other proteinogenic amino acids were not sufficient (32).

Putrescine also has the potential to be a signal for initiation of swarming (23). P. mirabilis can produce putrescine either directly from ornithine via ornithine decarboxylase (SpeF) or sequentially from arginine and agmatine via arginine decarboxylase (SpeA) and agmatinase (SpeB), and putrescine accumulation represses SpeA activity (23, 33). Disruption of speA or speB results in a severe swarming defect which can be complemented by exogenous putrescine, as would be expected if putrescine acts as a signaling molecule. However, as putrescine is also a component of the outer membrane of P. mirabilis (34), the exact cell-cell communication capabilities of this molecule remain unclear.

In this study, we expand on these previous investigations by further testing the hypothesis that P. mirabilis CaUTI isolates respond to specific cues capable of initiating swarming. Normally nonpermissive low-salt LB agar was used as a complex medium to screen for compounds that promote swarming, and a defined medium that does not permit swarming was used to precisely determine whether the nutrients act as swarming cues (35). P. mirabilis strain HI4320 was chosen for these investigations, as this strain is a CaUTI isolate for which the complete genome sequence is available, facilitating the generation of isogenic mutants to identify genes required for responses to the swarming cues. Using this approach, we identified five swarming cues (l-arginine, dl-histidine, l-glutamine, malate, and dl-ornithine), four of which had not previously been linked to swarming in P. mirabilis and all of which were detected in normal human urine. The ability to promote swarming required synthesis of both putrescine and glutamine and did not correlate with an alteration of the growth rate. Swarming in response to the cues was affected by disruption of pathways involved in amino acid metabolism, such as the oxidative TCA cycle, and required synthesis of glutamine but not arginine or histidine. Furthermore, in addition to promoting swarming under normally nonpermissive conditions, excess l-glutamine represented a strict requirement for swarming in general but not swimming motility. We conclude that P. mirabilis HI4320 initiates swarming in response to specific cues that are present in normal human urine and may therefore have physiological relevance for the establishment of CaUTI. Furthermore, while the response to these cues requires specific metabolic pathways, all but malate appear to promote swarming independently of their known roles in biosynthetic pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

A complete list of bacterial strains used in this study is provided in Table 1. All mutants were generated with P. mirabilis strain HI4320. CaUTI isolates that were tested for the ability to respond to swarming cues were isolated from female patients who were catheterized for ≥100 consecutive days (7). Bacteria were routinely cultured at 37°C with aeration in LB broth (10 g/liter tryptone, 5 g/liter yeast extract, 0.5 g/liter NaCl) or on LB broth solidified with 1.5% agar. Normal swarming was assessed by using swarm agar (LB agar with 5 g/liter NaCl), and swarming initiation studies utilized nonpermissive low-salt LB agar (0.5 g/liter NaCl), with test compounds added at a final concentration of 20 mM. Swimming motility was assessed by using Mot medium (10 g/liter tryptone, 5 g/liter NaCl) solidified with 0.3% agar. Proteus mirabilis minimal salts medium (PMSM) (35) was utilized for studies requiring defined medium [10.5 g/liter K2HPO4, 4.5 g/liter KH2PO4, 0.47 g/liter sodium citrate, 1 g/liter (NH4)2SO4, and 15 g/liter agar, supplemented with 0.001% nicotinic acid, 1 mM MgSO4, and 0.2% glycerol]. For studies using human urine, samples from 5 healthy female donors were pooled, filter sterilized, and solidified with 1.5% agar, where indicated. Media were supplemented with chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml), ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (25 μg/ml), or tetracycline (5 μg/ml), as required.

Table 1.

P. mirabilis strains used in this study

| Strain | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| HI4320 | Proteus mirabilis isolated from the urine of an elderly, long-term-catheterized woman | 7 |

| ureC | Ampr and disrupted urease subunit alpha | 54 |

| speB | Kanr insertion disrupting agmatinase (polyamine biosynthesis) | This study |

| speF | Kanr insertion disrupting ornithine decarboxylase (polyamine biosynthesis) | This study |

| speBF | Kanr insertion disrupting ornithine decarboxylase was excised, and an additional Kanr gene was inserted into agmatinase (polyamine biosynthesis) | This study |

| argG | Kanr insertion disrupting arininosuccinate synthase (urea cycle) | 27 |

| argH | Tn5 insertion disrupting argininosuccinate lyase (urea cycle) | 27 |

| hisG | Kanr insertion disrupting ATP phosphoribosyltransferase (histidine biosynthesis) | This study |

| glnA | Kanr insertion disrupting glutamine synthetase (GS-GOGAT) | This study |

| gdhA | Kanr insertion disrupting glutamate dehydrogenase | 53 |

| sdhB | Kanr insertion disrupting succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (TCA cycle) | 27 |

| frdA | Kanr insertion disrupting fumarate reductase subunit A (TCA cycle) | 27 |

| fumC | Kanr insertion disrupting fumarate hydratase (TCA cycle) | 27 |

Construction of mutant strains.

A kanamycin resistance gene was inserted into speB, speF, hisG, or glnA by using the TargeTron method (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions, as previously described (36). Primer sequences for intron reprogramming are included in Table 2 for each gene. Mutants were verified by PCR with primers designated “ver” in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| speB-IBS | AAAAAAGCTTATAATTATCCTTATTCACCTCCTGTGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTG |

| speB-EBS1d | CAGATTGTACAAATGTGGTGATAACAGATAAGTCTCCTGTTTTAACTTACCTTTCTTTGT |

| speB-EBS2 | TGAACGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGGTTGTGAATCGATAGAGGAAAGTGTCT |

| speF-IBS | AAAAAAGCTTATAATTATCCTTATCCTTCATAACGGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTG |

| speF-EBS1d | CAGATTGTACAAATGTGGTGATAACAGATAAGTCATAACGTGTAACTTACCTTTCTTTGT |

| speF-EBS2 | TGAACGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGGTTAAGGATCGATAGAGGAAAGTGTCT |

| hisG-IBS | AAAAAAGCTTATAATTATCCTTAGCTTGCCGTTTAGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTG |

| hisG-EBS1d | CAGATTGTACAAATGTGGTGATAACAGATAAGTCCGTTTATCTAACTTACCTTTCTTTGT |

| hisG-EBS2 | TGAACGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGATTCAAGCTCGATAGAGGAAAGTGTCT |

| glnA-IBS | AAAAAAGCTTATAATTATCCTTACAAATCTATAAAGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTG |

| glnA-EBS1d | CAGATTGTACAAATGTGGTGATAACAGATAAGTCTATAAATATAACTTACCTTTCTTTGT |

| glnA-EBS2 | TGAACGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGGTTATTTGTCGATAGAGGAAAGTGTCT |

| speB-ver-F | TCCGGCAAGGGCAGTAATATCTGA |

| speB-ver-R | GTGCTCACGCTAAACACTTTGGCA |

| speF-ver-F | TTTCCACGGCAACTAACTCCACCT |

| speF-ver-R | AGCATCTGGTCGCACAAATTGCTC |

| hisG-ver-F | TGGACGGAGTGGTTGATTTAGGCA |

| hisG-ver-R | TTGTTGCGTCCATTTCACCGTCAC |

| glnA-ver-F | TGGCCCTGAACCTGAATTCTTCCT |

| glnA-ver-R | AGGATCTGGGAAACGCACTTCGAT |

| pACD4K-C5′ | CCGCGAAATTAATACGACTCACTA |

| pACD4K-C3′ | GGTATCCCCAGTTAGTGTTA |

Screen for compounds that promote initiation of swarming.

For initial identification of swarming cues, test compounds purchased from Sigma (l-amino acids, TCA cycle intermediates, urea cycle intermediates, polyamines, and fatty acids) were dissolved in distilled H2O or methanol for fatty acids and passed through a 0.22-μm Millex filter (Millipore). LB agar was prepared and autoclaved, cooled to ∼42°C, and supplemented with a test compound to a final concentration of 20 mM prior to pouring. Exactly 8 ml of agar was dispensed into 60-mm petri dishes (Fisher Scientific). P. mirabilis HI4320, isogenic mutants, and other CaUTI isolates were cultured for ∼8 h in LB broth at 37°C with aeration, and plates were inoculated with 5 μl of these cultures and incubated at 37°C for 18 h. Swarm diameter was measured by using a caliper. This strategy was also used to test the ability of the swarming cues to induce swarming on PMSM and urine agar.

Measurement of swimming motility.

Mot agar was autoclaved, cooled to approximately ∼42°C, and supplemented with individual swarming cues to a final concentration of 20 mM, and 20 ml was dispensed into 100-mm petri dishes (Fisher Scientific). Mot plates were allowed to dry at room temperature for ∼5 h and stab inoculated with a culture of HI4320 grown for ∼8 h in LB medium at 37°C with aeration. Mot plates were incubated at 30°C for ∼16 h, and swimming diameter was measured by using a caliper.

Analysis of urine composition.

Urine samples collected from 5 healthy female donors were pooled and filter sterilized, and 4 aliquots of 0.5 ml were immediately frozen. The remaining pool was used to generate urine agar plates. Duplicate aliquots were sent to the Directed Metabolomics Laboratory of the Michigan Nutrition and Obesity Research Center at the University of Michigan. Purification of amino acids and derivatization for gas chromatography (GC)-mass spectrometry (MS) analysis were performed by using the EZ:faast kit for free amino acids (Phenomenex) (37). TCA cycle metabolites and nucleotides were analyzed by liquid chromatography (LC)-MS using mixed-mode hydrophilic interaction–anion-exchange liquid chromatography, as described previously by Lorenz et al. (38).

Testing the influence of pH and urea on swarming.

The same general strategy described above for the screen was used to test the impact of pH and urea on swarming. For pH studies, PMSM is a well-buffered medium, but LB agar was buffered with 10 mM HEPES (Fisher Scientific). The pH of the medium was adjusted to exactly 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, or 9.0 with HCl or KOH prior to autoclaving. Unsupplemented LB broth and PMSM were pH ∼7.0. For urea studies, urea was added to LB agar prior to pouring for a final concentration of 10 mM, 25 mM, 50 mM, 100 mM, or 500 mM. For studies on swarm agar, exactly 20 ml of medium was dispensed into 100-mm petri dishes instead of 60-mm petri dishes.

Growth curves.

Bacteria were cultured at 37°C overnight in 5 ml LB broth with aeration. Cultures grown overnight were diluted 1:100 in LB broth or PMSM supplemented with the swarming cues to a final concentration of 20 mM. A Bioscreen-C automated growth curve analysis system (Growth Curves USA) was utilized to generate growth curves. Cultures were incubated at 37°C with continuous shaking, and optical density at 600 nm (OD600) readings were taken every 15 min for 24 h.

Statistics.

Significance was determined by unpaired Student's t test, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), or Pearson's correlation with linear regression, where appropriate. All P values are two tailed at a 95% confidence interval. Analyses were performed by using GraphPad Prism, version 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Identification of compounds that promote Proteus mirabilis swarming on a nonpermissive rich medium.

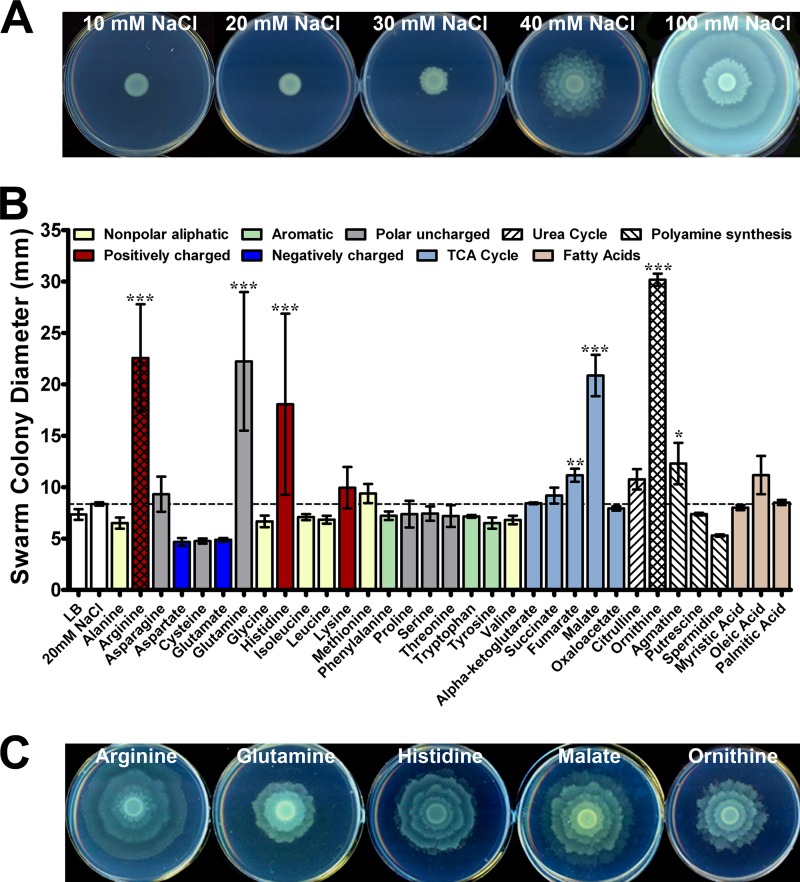

LB agar containing 100 mM NaCl allows for robust swarming and is referred to throughout as swarm agar. Decreasing the salt concentration to 10 mM generates a rich medium that does not permit swarming within 24 h of growth at 37°C, which is referred to simply as LB agar or low-salt LB agar. Importantly, low-salt LB agar does not inhibit swarm cell differentiation, as P. mirabilis can swarm on these plates if incubated at 30°C or room temperature. The lowest concentration of NaCl that promotes detectable motility for P. mirabilis strain HI4320 after 24 h of growth at 37°C was experimentally determined to be >30 mM (Fig. 1A). Therefore, test compounds were added to LB agar at a final concentration of 20 mM to ensure a high-enough concentration to allow for identification of all factors that induce swarming while remaining below the concentration of NaCl that makes LB agar permissive for swarming.

Fig 1.

Identification of factors that promote Proteus mirabilis swarming. (A) Representative images of swarming on LB agar containing increasing amounts of sodium chloride. (B) Diameter of the P. mirabilis swarm colony following 18 h of incubation on low-salt LB agar containing the listed factors at a final concentration of 20 mM. The dashed line indicates the average swarm colony diameter for P. mirabilis HI4320 on LB agar containing 20 mM NaCl. Error bars represent means and standard deviations for three independent experiments with four replicates each. Statistical significance was determined by comparing the swarm colony diameter on test compounds to the diameter on LB medium containing 20 mM NaCl. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (C) Representative images of swarming induced by 20 mM arginine, glutamine, histidine, malate, or ornithine on low-salt LB agar.

Thirty-three compounds representing 20 proteinogenic amino acids, 5 TCA cycle intermediates, 6 urea cycle intermediates, 3 fatty acids, and 5 intermediates in polyamine biosynthesis were tested for their ability to promote swarming when added to LB agar (Fig. 1B). Of these compounds, seven significantly increased swarm colony diameter when added in excess to LB agar. Arginine, glutamine, histidine, malate, and ornithine promoted the development of at least two distinct swarm rings (Fig. 1C) that contained elongated swarm cells (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and are referred to as swarming cues. While these swarming cues consistently promoted swarming on low-salt LB agar, it is important to note that the swarms exhibited moderate variability in pattern and diameter between independent experiments. Fumarate and agmatine allowed for a statistically significant increase in swarm colony diameter but did not consistently promote the development of more than one swarm ring and were therefore not considered to be swarming cues.

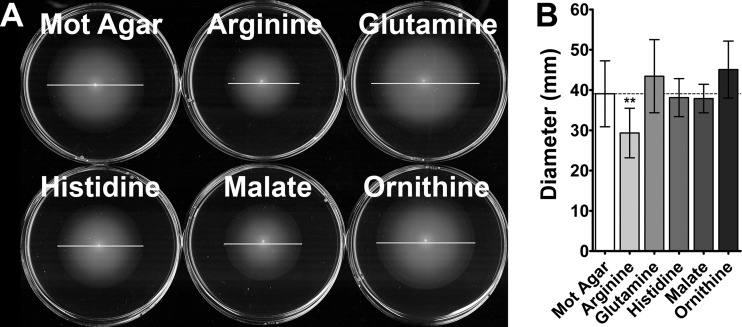

Swarming in response to glutamine, histidine, malate, and ornithine generally exhibited a normal dose response, while arginine exhibited a dose response only at concentrations of up to 20 mM, and higher concentrations prevented swarming (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Importantly, none of the five cues dramatically altered normal swarming on permissive medium, although arginine resulted in a slight but statistically significant decrease in the diameter of the second swarm ring (P < 0.001), and glutamine resulted in a slight but statistically significant increase in the diameter of all swarm rings (P = <0.05) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). All five swarming cues were also capable of promoting swarming when the salt concentration was decreased to 5 mM or lower (data not shown). None of the cues enhanced swimming motility through semisolid Mot agar, indicating that the identified cues are specific for swarming (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the cues were not observed to promote swarm cell differentiation during culture in LB broth, indicating that surface contact is required for swarming in response to the cues and that they do not strictly force swarm cell differentiation (data not shown). Thus, P. mirabilis HI4320 initiates swarming on agar plates in response to swarming-specific cues that include one TCA cycle intermediate (malate), three proteinogenic amino acids (arginine, glutamine, and histidine), and two amino acid intermediates of both polyamine synthesis and the urea cycle (arginine and ornithine).

Fig 2.

Swarming cues do not enhance swimming motility. (A) Representative images of swimming motility on plain Mot agar compared to Mot agar containing the swarming cues at 20 mM. White horizontal lines indicate total swimming diameter at 16 h. (B) Graph of swimming motility diameter compiled from six independent experiments with three replicates each. The dashed line indicates the average swimming motility diameter in unsupplemented Mot agar. Error bars represent means and standard deviations. **, P < 0.01.

Most P. mirabilis CaUTI isolates tested respond to the five swarming cues.

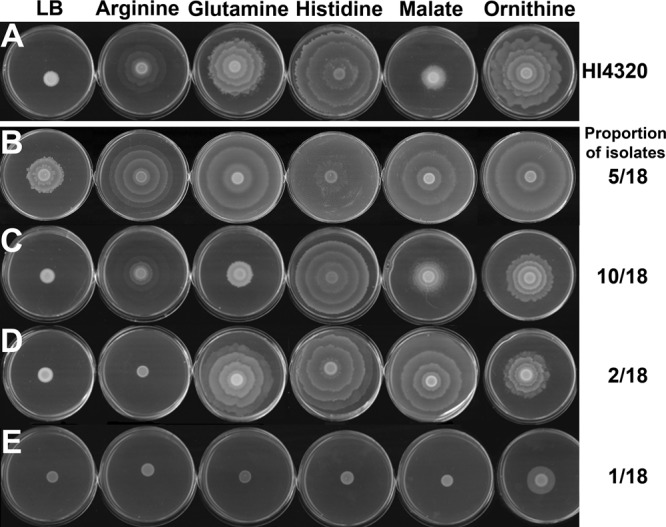

To determine if the identified swarming cues are universal for P. mirabilis CaUTI isolates, 20 clinical isolates were examined for swarming on swarm agar and the response to the swarming cues for comparison to P. mirabilis HI4320 (Fig. 3). Two of the 20 isolates were nonmotile and were therefore excluded from the study. Of the remaining 18 isolates that were motile, 5 were capable of swarming on low-salt LB agar, but swarm diameter was further enhanced by each of the swarming cues (Fig. 3B). Ten of the isolates exhibited the same general response to all five swarming cues as P. mirabilis HI4320, although the exact swarm pattern and diameter varied between isolates (Fig. 3C). Two isolates swarmed in response to glutamine, histidine, malate, and ornithine but did not respond to arginine (Fig. 3D), and one isolate swarmed in response to ornithine but did not respond to the other swarming cues (Fig. 3E). Thus, the identified swarming cues promoted swarming in the majority of P. mirabilis CaUTI isolates tested, but considerable strain variability exists in the extent of swarming that occurs in response to the cues.

Fig 3.

Cues promote swarming in other Proteus mirabilis strains. Twenty P. mirabilis clinical isolates from patients with CaUTI were tested for their ability to swarm in response to cues. Eighteen strains were capable of swarming on swarm agar and were further tested for responses to the swarming cues. (A) Representative images of the swarming pattern for HI4320 in response to the cues. (B) Representative images for five strains that swarmed on LB agar but increased the swarm diameter in response to the cues. (C) Representative images for 10 strains that did not swarm on LB agar but responded to all five cues. (D) Representative images for two strains that swarmed in response to all cues except arginine. (E) Representative images for one strain that responded to ornithine only. All images are representative of two independent experiments with three replicates each.

Swarming cues promote swarming on other types of media.

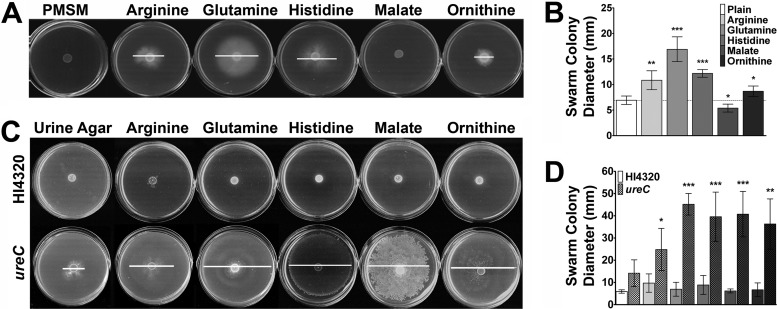

To determine if initiation of swarming is a specific response to the cues, a defined minimal salts medium (PMSM) that is not normally permissive for swarming was utilized (35). Notably, PMSM lacks amino acids and contains only glycerol, citrate, and nicotinic acid. Unlike LB agar, the addition of sodium chloride to this medium does not make it permissive for swarming (data not shown). Only the four amino acid cues were capable of promoting swarming on PMSM (Fig. 4A and B), indicating that arginine, glutamine, histidine, and ornithine alone are sufficient to induce swarming in minimal medium. In contrast, malate decreased the colony diameter on PMSM, indicating that this particular cue promotes swarming only in complex media.

Fig 4.

Cues promote swarming on other normally nonpermissive media. (A) Representative images of swarming in response to the five cues at 20 mM in PMSM. (B) Swarm colony diameter on PMSM for five independent experiments with 3 replicates each. The dashed line indicates the average swarm colony diameter on unsupplemented PMSM. (C) Comparison of swarming by P. mirabilis HI4320 and a ureC mutant on urine agar with swarming cues added to a final concentration of 20 mM. (D) Swarm colony diameter on urine agar for HI4320 and a ureC mutant. White lines indicate swarm diameter. Error bars represent means and standard deviations for four independent experiments with four replicates each. Statistical significance was determined by comparing the swarm diameter under each condition to the diameter on plain medium for each strain. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

As swarming along a urine-bathed catheter is a mechanism by which P. mirabilis gains entry to the urinary tract, it was imperative to determine if the cues influence swarming under physiologically relevant conditions, such as when added to urine agar. Urine samples collected from five healthy female donors were pooled and solidified with 1.5% agar. In agreement with the literature, all five swarming cues were present in the pooled urine, with histidine being the second most concentrated free amino acid at 0.25 mM (Table 3) (39–41). Interestingly, P. mirabilis HI4320 was unable to swarm on urine agar, even when further supplemented with the cues (Fig. 4C and D). However, P. mirabilis encodes a urease that cleaves urea to carbon dioxide and ammonia, resulting in a rapid increase in pH and precipitation of calcium and magnesium ions that form crystals (8). The rapid increase in pH and the formation of crystals in the confined space of the plate can interfere with growth and swarming, so a urease-negative (ureC) mutant was also tested for swarming on urine agar (Fig. 4C and D). Importantly, the ureC mutant exhibited modest swarming on unsupplemented urine agar that was significantly enhanced by each of the cues (Fig. 4C) and resulted in production of elongated swarm cells (data not shown). Interestingly, glutamine allowed for the development of a bull's-eye pattern, malate and ornithine promoted what appeared to be uncoordinated swarms, and swarming in response to arginine or histidine did not always exhibit normal periodicity. However, the results indicate that the four amino acid swarming cues are sufficient to promote swarming as long as growth requirements are satisfied, while malate promotes swarming only in more complex media, and all five compounds promote swarming in human urine. Furthermore, swarming in response to the cues on urine agar could be initiated with 0.1 mM each cue and followed the same general trends as those observed with low-salt LB agar (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

Table 3.

Composition of pooled urine from female donors

| Component of pooled human urine | Avg concn (μM) |

|---|---|

| Amino acids | |

| 4-Hydroxyproline | 0.62 |

| Alanine | 130.61 |

| Alpha-aminoisobutyric acid | 4.38 |

| Arginine | +a |

| Asparagine | 43.03 |

| Aspartic acid | 5.81 |

| Cystine | 6.76 |

| Glycine | 775.09 |

| Glutamic acid | 5.54 |

| Glutamine | 66.92 |

| Histidine | 250.04 |

| Isoleucine | 4.81 |

| Leucine | 12.51 |

| Lysine | 23.43 |

| Methionine | 3.41 |

| Ornithine | 2.58 |

| Phenylalanine | 17.15 |

| Proline | 4.19 |

| Sarcosine | 1.08 |

| Serine | 122.02 |

| Threonine | 69.36 |

| Tryptophan | 8.38 |

| Tyrosine | 19.83 |

| Valine | 17.08 |

| TCA cycle intermediates | |

| Alpha-ketoglutarate | 172.57 |

| Citrate | 1,826.01 |

| Fumarate | 2.59 |

| Malate | 31.50 |

| Succinate | 90.55 |

+, arginine was detected, but the exact concentration could not be determined.

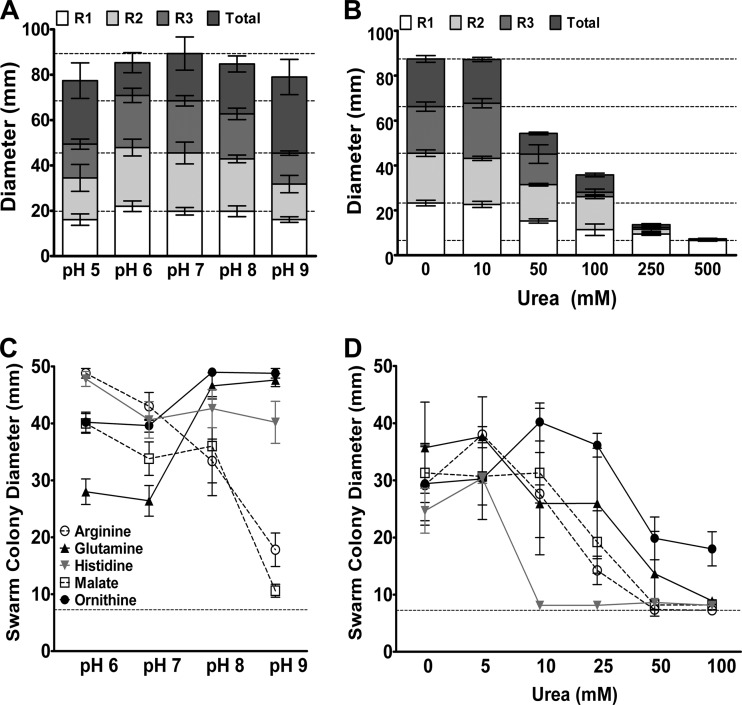

Response to swarming cues varies with pH and the addition of urea.

One explanation for the difference between P. mirabilis HI4320 and the ureC mutant on urine agar is that swarming may be suboptimal at basic pH, particularly as swarm cells appear to be most abundant at low pH (42). To determine the impact of pH on swarming for P. mirabilis HI4320, swarm agar was buffered with 10 mM HEPES and adjusted to pH 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, or 9.0 (Fig. 5A). Swarming was optimal at neutral pH, and the swarm ring diameter varied across the pH range, but P. mirabilis was capable of swarming at all pH values tested. To determine the impact of urea and subsequent urease activity on swarming, urea was added to swarm agar in concentrations ranging from 10 mM to 500 mM (Fig. 5B). Urea at 10 mM had no impact on swarm diameter, but swarming was significantly impaired by 50 mM urea and completely inhibited by 500 mM urea. Therefore, P. mirabilis HI4320 is capable of swarming at high pH and with a moderate concentration of urea but is inhibited by high concentrations of urea within the confines of a 100-mm petri dish.

Fig 5.

Swarming and response to cues are influenced by pH and urea. (A) Diameter of the first (R1), second (R2), and third (R3) swarm rings to the consolidation zone and total swarm diameter for P. mirabilis HI4320 on swarm agar buffered with HEPES to pH 5, 6, 7, 8, or 9. Dashed lines indicate average swarm ring diameters at pH 7. (B) Diameter of the first (R1), second (R2), and third (R3) swarm rings and total swarm diameter for P. mirabilis HI4320 on swarm agar containing increasing concentrations of urea. Dashed lines indicate average swarm ring diameters in the absence of urea. (C) Swarm colony diameter on low-salt LB agar buffered with HEPES and adjusted to pH 6, 7, 8, or 9 prior to adding the swarming cues. The dashed line indicates the swarm colony diameter on unsupplemented LB agar at pH 7. (D) Swarm colony diameter on low-salt LB agar containing the cues and supplemented with increasing concentrations of urea. The dashed line indicates the swarm colony diameter on unsupplemented LB agar. Error bars represent means and standard deviations for three independent experiments with three replicates each.

As the urea concentration can reach 500 mM in urine, and urease activity results in a rapid increase in pH, the most relevant swarming cues for the study of CaUTI would need to be effective across a wide pH range and promote swarming in the presence of urea. When added to buffered LB agar, arginine and malate promoted the largest swarms at pH 6, glutamine and ornithine promoted the most swarming at pH 9, and modulating pH did not impact swarming in response to histidine (Fig. 5C). Therefore, arginine and malate are optimal under slightly acidic conditions, while the other cues function well across a wide pH range but appear to be best at basic pH. Furthermore, all cues promoted swarming when urea was present at 5 mM, all but histidine promoted swarming with up to 25 mM urea, and ornithine still promoted swarming with over 100 mM urea (Fig. 5D).

Swarming in response to the swarming cues is not correlated with growth rate.

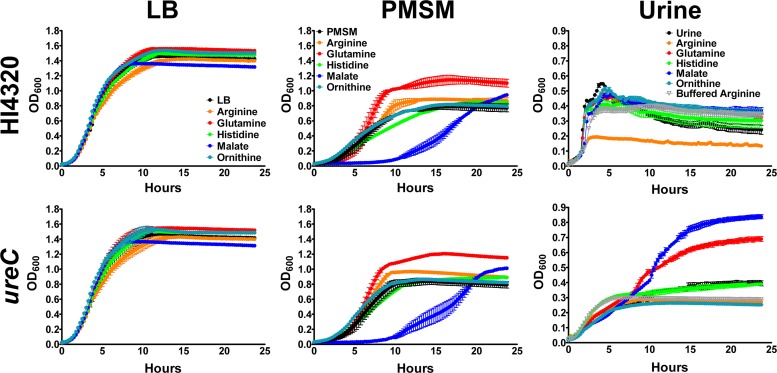

A previous study of nutritional requirements for swarming found a correlation between induction of swarming and decreased generation time (29). However, none of the swarming cues in the present study increased the growth rate in LB medium, and malate slightly decreased the optical density at which stationary phase was achieved (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6), indicating that the cues do not promote swarming on LB agar by enhancing the growth rate. In PMSM, however, glutamine enhanced growth (P < 0.001), and malate resulted in a prolonged lag phase, which may explain why glutamine has such a potent impact on swarming in this medium, while malate does not promote swarming.

Fig 6.

Swarming cues do not uniformly enhance growth rate. Growth curves were determined for P. mirabilis HI4320 and the ureC mutant in plain LB medium, PMSM, and urine compared to media containing individual swarming cues at a final concentration of 20 mM. Graphs are representative of three independent experiments with five replicates each.

To further examine the possible relationship between growth and swarming in PMSM, all five swarming cues were used alone or in various combinations and assessed for their effect on growth rate and the ability to promote swarming in different PMSM formulations (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Sixty out of 180 formulations allowed for the development of at least one swarm ring, but growth was enhanced in only 25 of these 60 formulations. Overall, no correlation was found between growth rate and swarm diameter, even when analyzing only conditions that enhanced growth, allowed for swarming, or contained glutamine (Pearson R2 values of 0.06225, 0.04772, and 0.0001201, respectively). Thus, even though glutamine tends to enhance growth, there is no correlation between growth rate and swarming on low-salt LB agar or PMSM.

When urine was used as the growth medium, none of the swarming cues enhanced the growth rate for P. mirabilis HI4320, but arginine dramatically decreased the optical density at which stationary phase was achieved (P < 0.001). Notably, buffering of the urine prior to the addition of arginine restored growth to a similar level as that in plain urine, and the ureC mutant did not exhibit a growth defect when cultured with arginine. As arginine catabolism results in the production of urea, which would lead to the activation of urease and subsequent production of ammonia, the growth defect for P. mirabilis HI4320 but not the ureC mutant in urine containing arginine is likely due to a pH increase. This may also explain why arginine promotes swarming at acidic to neutral pHs but not basic pH.

Overall, the ureC mutant exhibited growth similar to that of HI4320 in LB agar and PMSM but did not grow as well in urine, likely due to the inability to utilize urea as a nitrogen source. In support of this hypothesis, the ureC mutant exhibited dramatically enhanced growth in urine containing glutamine (P < 0.001), a readily utilized nitrogen source. Interestingly, malate also enhanced the growth of the ureC mutant in urine (P < 0.001), while it did not impact the growth of the parental strain and actually decreased the growth of both strains in PMSM, which may explain why malate is a swarming cue for the ureC mutant on urine agar but does not promote swarming on PMSM. However, taken together, the data clearly show that arginine, histidine, and ornithine promote swarming without affecting the growth rate, regardless of the type of medium, and even though glutamine and malate alter the growth rate, this effect is not correlated with a propensity for swarming.

Putrescine synthesis by at least one pathway is required for swarming in response to the cues.

Two of the swarming cues (ornithine and arginine) and one factor that promoted an increase in the swarm colony diameter but was not considered a swarming cue (agmatine) are all part of putrescine biosynthesis in P. mirabilis (33). While putrescine itself was not identified as a swarming cue in this study, putrescine synthesis is known to be an important factor in swarming (23). Therefore, ornithine, arginine, and agmatine could promote swarming strictly by promoting putrescine synthesis when added in excess to normally nonpermissive media.

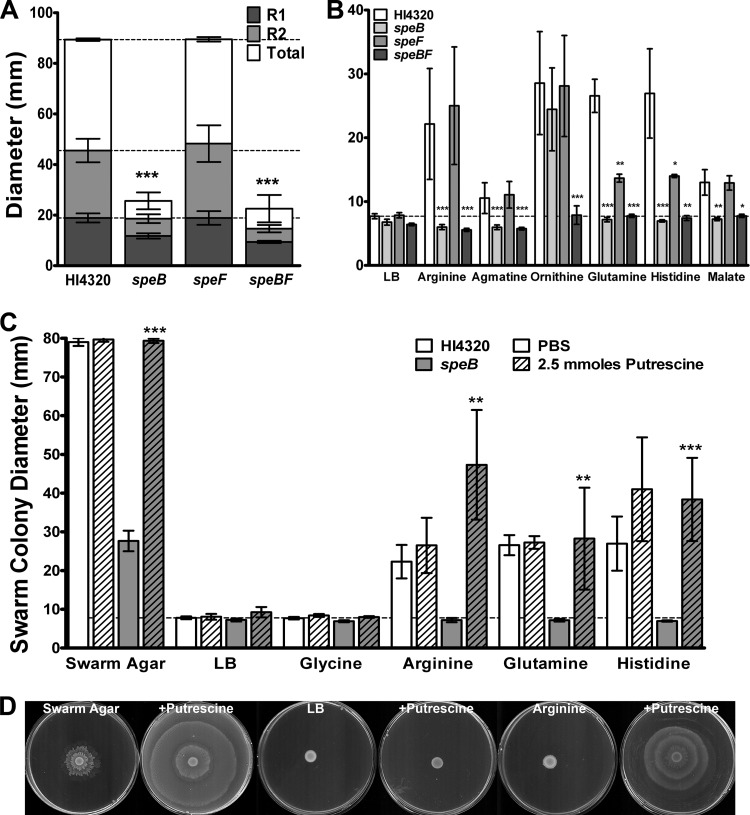

P. mirabilis HI4320 generates putrescine through two main pathways: agmatine is produced from arginine via arginine decarboxylase (SpeA), and putrescine is then generated from agmatine via agmatinase (SpeB), or putrescine can be generated directly from ornithine via ornithine decarboxylase (SpeF) (33). To determine the role of these pathways in swarming and the response to the cues, speB and speF single mutants were constructed to interrupt each separate pathway and a speBF double mutant was constructed to block both known pathways for putrescine synthesis. Interestingly, the speF mutant exhibited swarming similar to that exhibited by the parental strain on swarm agar, while the speB and speBF mutants were severely impaired (Fig. 7A). Arginine decarboxylase and agmatinase therefore appear to be part of the primary pathway for putrescine synthesis under these conditions.

Fig 7.

Putrescine synthesis is required for swarming in response to the cues. (A) Diameter of the first ring, second ring, and the total swarm for P. mirabilis HI4320 compared to the speB, speF, and speBF mutants on swarm agar. Dashed lines indicate average swarm ring diameters for P. mirabilis HI4320. (B) Swarm colony diameter of P. mirabilis HI4320 and the putrescine synthesis mutants on low-salt LB agar supplemented with compounds involved in putrescine synthesis (arginine, agmatine, and ornithine) compared to swarming cues that are not related to putrescine synthesis (glutamine, histidine, and malate). The dashed line indicates the average swarm ring diameter for P. mirabilis HI4320. (C) Swarm colony diameter for the speB mutant compared to P. mirabilis HI4320 on a swarm agar or low-salt LB agar spread plate with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or 2.5 mmol putrescine and supplemented with glycine, arginine, glutamine, or histidine. The dashed line indicates the average swarm ring diameter for the speB mutant on unsupplemented low-salt LB agar. (D) Representative images showing the ability of putrescine to complement the swarming defects of the speB mutant on swarm agar versus low-salt LB agar with arginine. Error bars represent means and standard deviations for three independent experiments with three replicates each. Significance was determined by comparing the swarm diameter of the mutants to that of HI4320 in panels A and B and PBS to putrescine in panel C. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

The speB mutant also failed to swarm in response to arginine, agmatine, glutamine, histidine, and malate but was capable of swarming in response to ornithine, indicating that ornithine likely complements the agmatinase defect by allowing for the generation of putrescine via ornithine decarboxylase (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the speF mutant swarmed to a level similar to that of the parental strain on arginine, agmatine, ornithine, and malate but exhibited significantly reduced swarming on glutamine and histidine. This finding suggests that while ornithine decarboxylase is not part of the primary pathway for putrescine synthesis under normal circumstances, it may be required for a full response to swarming cues that are not directly involved in putrescine biosynthesis. As expected, the speBF double mutant failed to swarm in response to any of the compounds, indicating that at least one pathway for putrescine synthesis must be intact for P. mirabilis HI4320 to swarm in response to the cues.

Importantly, all observed defects for the speB mutant could be complemented with putrescine at a concentration low enough as to not alter swarming of the parental strain or to allow swarming in response to the noncue glycine (Fig. 7C and D). This concentration of putrescine fully restored swarming to the level observed for the parental strain, and the combination of arginine and putrescine allowed for significantly more swarming by the speB mutant than by P. mirabilis HI4320. Taken together with the finding that putrescine alone is not sufficient to promote swarming for P. mirabilis HI4320 or the speB mutant, the data indicate that while ornithine and arginine are involved in putrescine synthesis and can complement putrescine synthesis and swarming defects in the mutants, they also likely promote swarming through a mechanism that is unrelated to the production of putrescine.

Swarming in response to the cues requires pathways involved in amino acid metabolism.

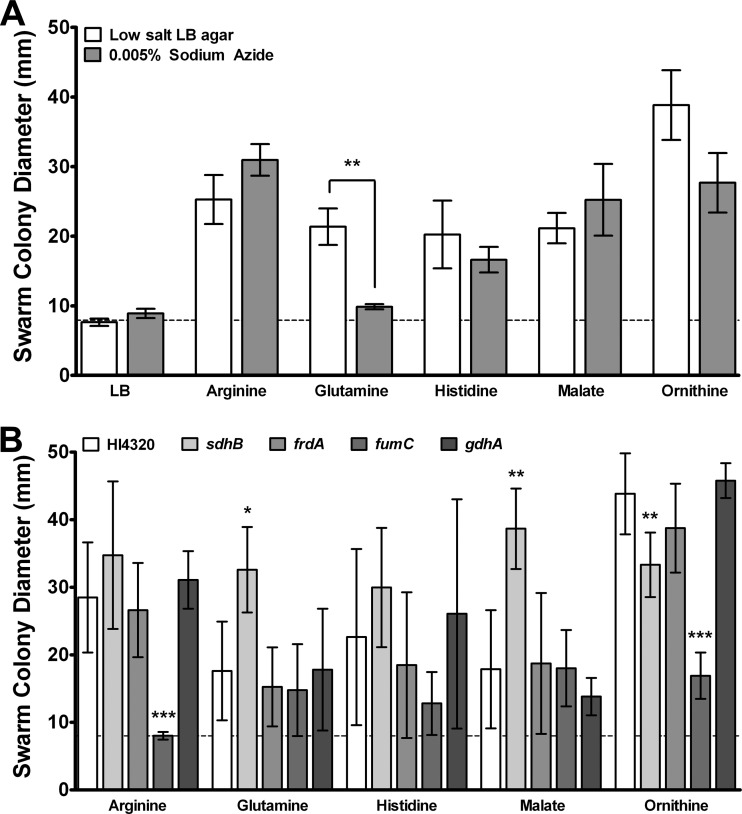

As putrescine biosynthesis did not fully explain how the cues promote swarming and because the identified cues are either amino acids or a TCA cycle intermediate, we wanted to explore the role of amino acid catabolic pathways in response to the swarming cues. Metabolism of many amino acids requires TCA cycle intermediates, and our laboratory recently determined that P. mirabilis HI4320 likely uses a complete oxidative TCA cycle and anaerobic respiration for energy during swarming (27). Swarming still occurs when aerobic respiration is inhibited by sodium azide (NaN3), but only mutations affecting aerobic respiration significantly alter swarming periodicity (26, 27). To first determine if aerobic respiration is required for swarming in response to the cues, NaN3 was added to low-salt LB agar at a concentration low enough to permit growth on LB agar but high enough to inhibit growth in broth culture (0.005%, wt/vol) (Fig. 8A) (27). Arginine, histidine, malate, and ornithine were all capable of promoting swarming on plates containing 0.005% NaN3, but glutamine was not, indicating that the ability of glutamine to promote swarming could require aerobic respiration.

Fig 8.

Swarming in response to the cues requires pathways involved in amino acid catabolism. (A) Swarm colony development in response to the cues on low-salt LB agar compared to LB agar containing 0.005% NaN3. The dashed line indicates the average swarm colony diameter on unsupplemented LB agar. (B) Diameter of swarms developed by P. mirabilis HI4320 isogenic mutants with defects in amino acid catabolism on low-salt LB agar containing arginine, glutamine, histidine, malate, or ornithine. The dashed line indicates the average swarm colony diameter on unsupplemented LB agar. Error bars represent means and standard deviations for three independent experiments with three replicates each. Statistical significance was determined by comparing mutants to the parental strain under each condition. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To further explore the role of aerobic respiration and the TCA cycle in the response to the swarming cues, isogenic mutants with defects in metabolism were tested for their ability to swarm on low-salt LB agar supplemented with each individual swarming cue (Table 1 and Fig. 8B). Disruption of succinate dehydrogenase, encoded by sdhB, decreased swarming in response to ornithine and increased the swarm diameter on LB agar containing glutamine or malate. The decreased swarming with ornithine may be a manifestation of the altered swarm pattern previously observed for this mutant (25, 27), or it may indicate that this step in the TCA cycle is required for the full response to ornithine. However, increased swarming with glutamine and malate suggests that a loss of sdhB enhances swarming in response to these particular cues. In the absence of succinate dehydrogenase, P. mirabilis could still operate a reductive, branched TCA cycle utilizing fumarate reductase. Even though fumarate reductase (FrdA) was not required for swarming under any condition tested (Fig. 8B) (27), we cannot rule out a possible role in the sdhB mutant under conditions of excess malate or glutamine.

Disruption of fumarase, encoded by fumC, decreased swarming in response to both arginine and ornithine but had no significant impact on the response to the other cues. As the aberrant swarming of the fumC mutant could be complemented by the addition of malate on swarm agar (27), and this mutant did not exhibit a defect on low-salt LB agar supplemented with malate, it is clear that excess malate promotes a complete oxidative TCA cycle rather than driving production of fumarate. FumC is also clearly important for swarming in response to arginine and ornithine, possibly because fumarate is produced as a by-product of ornithine degradation and arginine biosynthesis. Interestingly, another TCA cycle intermediate, alpha-ketoglutarate, is closely associated with glutamine and glutamate metabolism via glutamate dehydrogenase (GhdA). However, mutation of gdhA had no effect on swarming in response to any of the cues, indicating that glutamine most likely does not promote swarming by entering the TCA cycle via this route.

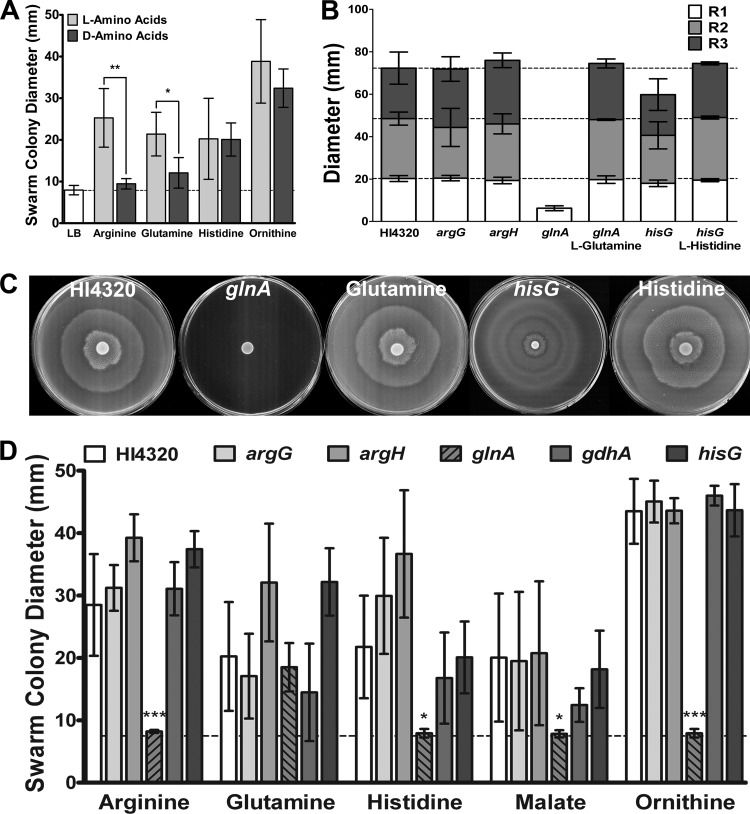

l-Glutamine is required for P. mirabilis swarming.

In addition to determining the metabolic pathways required for the response to each cue, we also wanted to determine if the function of the amino acid swarming cues is enantiomer specific (Fig. 9A). Interestingly, d-arginine and d-glutamine did not promote swarming on low-salt LB agar, while d-histidine and d-ornithine allowed for a similar level of swarming as the l-enantiomers. The response to arginine and glutamine may therefore be related to the role of these amino acids in protein synthesis, while the response to histidine and ornithine does not appear to be enantiomer specific. However, it is important to note the d-histidine and d-ornithine preparations may contain trace l-enantiomer contaminants.

Fig 9.

Excess l-glutamine is required for normal swarming and for response to the other cues. (A) Swarm colony diameter of P. mirabilis HI4320 on low-salt LB agar supplemented with l-amino acid swarming cues compared to d-amino acids. The dashed line indicates the average swarm colony diameter on unsupplemented LB agar. (B) Diameter of the first (R1), second (R2), and third (R3) swarm rings that developed on normal swarm agar for P. mirabilis HI4320 and the argG, argH, glnA, and hisG isogenic amino acid synthesis mutants. Swarm ring diameters for the glnA mutant complemented with l-glutamine and the hisG mutant complemented with l-histidine are also shown. Dashed lines indicate average swarm ring diameters for P. mirabilis HI4320. (C) Representative images of P. mirabilis HI4320, the glnA mutant on plain swarm agar compared to agar supplemented with glutamine, and the hisG mutant on plain swarm agar compared to agar supplemented with histidine. (D) Swarm colony diameter of P. mirabilis HI4320 and amino acid synthesis mutants on low-salt LB agar with swarming cues. The dashed line indicates the average swarm colony diameter for P. mirabilis HI4320 on unsupplemented LB agar. Error bars represent means and standard deviations for three independent experiments with three replicates each. Significance was determined by comparing the swarm diameter of the mutants to that of P. mirabilis HI4320 under each condition. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

To address the contribution of amino acid synthesis to the initiation of swarming, isogenic mutants with defects in arginine (argG and argH), glutamine (glnA), and histidine (hisG) biosynthesis were first tested for normal swarming on swarm agar (Fig. 9B). Disruption of arginine biosynthesis at either step did not significantly impact swarming. However, disruption of glutamine biosynthesis completely inhibited normal swarming, and disruption of histidine biosynthesis resulted in a decreased swarm ring diameter. This finding was unexpected, as LB agar contains approximately 1 mM l-histidine and 0.6 mM l-glutamine (43). As the glnA mutant exhibited only a modest growth defect in LB broth (data not shown), the severe swarming defect is not due to impaired growth. GlnA is the glutamine synthetase component of the glutamine synthetase-glutamate synthase (GS-GOGAT) pathway for nitrogen assimilation and regulation of the glutamine pool, indicating that glutamine synthesis or sensing and responding to glutamine levels are critical for swarming.

Importantly, swarming by the glnA mutant could be completely restored with the addition of l-glutamine but not d-glutamine or l-glutamate (Fig. 9C and D and data not shown). Restoration of noticeable swarming for the glnA mutant required as little as 1 μmol excess l-glutamine, but full complementation of the defect required approximately 10 μmol excess l-glutamine (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Similarly, the addition of histidine to swarm agar complemented the swarming defect for the hisG mutant, indicating that these swarming defects were due to glutamine and histidine auxotrophy rather than downstream effects of the mutations. Notably, the glnA and hisG mutants were able to swim through Mot agar, although the glnA mutant had a slight but statistically significant decrease in swimming diameter, indicating that the requirement for glutamine synthetase and histidine biosynthesis is specific for swarming (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material).

Amino acid synthesis mutants were also tested for their ability to respond to the swarming cues on low-salt LB agar (Fig. 9D). Both arginine biosynthesis mutants and the histidine biosynthesis mutant responded to the cues in a manner similar to that of the parental strain, indicating that regardless of the role of these biosynthetic pathways during normal swarming, their defects are overcome by an excess of any of the swarming cues on low-salt LB agar. In contrast, the glnA mutant was unable to initiate swarming on low-salt LB agar in response to any of the cues except glutamine, indicating that the requirement for glutamine cannot be overcome by an excess of other swarming cues. Therefore, arginine and histidine biosynthesis is not required for initiation of swarming in response to cues on LB agar, but l-glutamine must be either synthesized or exogenously provided in excess of the ∼0.6 mM present in LB agar to allow for initiation of swarming, regardless of whether or not the medium would normally be permissive for swarming.

DISCUSSION

P. mirabilis swarming has intrigued scientists since the discovery of the swarm cell in 1885 (44), particularly for the cyclic nature of swarm cell differentiation, advancement of the swarm raft, and consolidation, all of which result in the characteristic bull's-eye pattern on 1.5% agar. Despite extensive research, the underlying mechanisms for coordination of swarm cell differentiation and the multicellular interactions required for swarming in P. mirabilis are still not fully understood. Due to the cell density requirements for swarming, it seems probable that swarm cell differentiation is controlled by quorum sensing. However, no known quorum-sensing systems appear to be involved in regulation of this behavior (45, 46). Investigation of factors capable of promoting swarming may therefore provide new insight into how this behavior is both regulated and coordinated. We have identified four compounds not previously connected to motility in P. mirabilis that are all present in human urine (arginine, histidine, malate, and ornithine) and confirmed the ability of glutamine to promote swarming under nonpermissive conditions. Furthermore, we provide the first evidence that glutamine in excess of ∼0.6 mM is a basic requirement for initiation of swarming on swarm agar in addition to being a cue that promotes swarming under normally nonpermissive conditions. While none of these cues are typical quorum-sensing molecules, they are capable of promoting and sustaining the multicellular process of swarming and may therefore be related to sensory networks for determining when conditions are appropriate for swarming. Alternatively, P. mirabilis may need a certain threshold level of these compounds to promote metabolic pathways required for swarming or for changes in cell wall composition required for swarm cell differentiation.

Our criteria for swarming-specific cues included not only the ability to induce swarming on nonpermissive media but also that the cues should be broadly active in different P. mirabilis isolates, have no impact on swimming motility, and be functional under physiologically relevant conditions. Indeed, the majority of CaUTI clinical isolates were capable of swarming in response to all five cues, none of the identified swarming cues enhanced swimming motility, all of the cues were active across a wide pH range and in the presence of millimolar concentrations of urea, and all of the cues promoted swarming on urine solidified with 1.5% agar as long as urease activity was inhibited. As these swarming cues are all present in normal human urine (Table 3), and swarming on urine agar required less than 0.1 mM the cues, it is tempting to speculate that P. mirabilis senses the concentration of these factors in its environment and modulates swarming on the catheter based on their relative abundance. However, this hypothesis has yet to be tested directly, and further investigation will be necessary to analyze the importance of these compounds during CaUTI. Furthermore, the variability in the effect of the swarming cues on swimming motility, swarming on permissive agar (swarm agar), the swarm patterns that develop on different types of media, growth in different types of media, and the metabolic requirements for the response to the cues (summarized in Table 4) would suggest that these compounds promote swarming through different mechanisms.

Table 4.

Summary of swarming cue characteristicsb

| Cue | % of CaUTI isolates with cue | Swarming |

Growth rate | LB containing NaN3 | Genes required for response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swarm agar | PMSM agar | Urine agara | Mot agar | |||||

| Arginine | 89 | ↓ | + | + | ↓ | +/− | + | speB, fumC, glnA |

| Glutamine | 94 | Required, ↑ | + | + | +/− | ↑ PMSM, ↑ urinea | − | speB, speF |

| Histidine | 94 | Beneficial, +/− | + | + | +/− | +/− | + | speB, speF, glnA |

| Malate | 94 | +/− | − | + | +/− | ↓ PMSM, ↑ urinea | + | speB, glnA |

| Ornithine | 100 | +/− | + | + | +/− | +/− | + | speB, sdhB, fumC, glnA |

Tested with the ureC mutant.

+, promotes swarming; −, no swarming; +/−, no change; ↑, increased; ↓, decreased.

Putrescine has been proposed as a potential extracellular swarming signal for P. mirabilis, as the production of this polyamine via arginine decarboxylase (SpeA) and agmatinase (SpeB) is required for effective swarming, and the accumulation of putrescine reduces speA expression (23). Two of the identified cues (arginine and ornithine) contribute to putrescine biosynthesis in P. mirabilis (33), making it tempting to speculate that they induce swarming by promoting putrescine biosynthesis; however, our data do not support this conclusion. Putrescine production by at least one pathway was required for P. mirabilis swarming under normal conditions, but the finding that excess putrescine alone was not sufficient to promote swarming indicates that the ability of arginine and ornithine to promote swarming may be unrelated to putrescine synthesis. Furthermore, arginine and ornithine had different influences on swimming motility and swarm patterns on normal swarm agar and different pH and urea tolerance, and the genetic requirements for the response to these cues differ, indicating that they likely promote swarming by unrelated mechanisms (Table 3).

In Serratia liquefaciens, coordination of swarming requires sensing and integration of several signals, including relative concentrations of amino acids, culture density, surface recognition, and cell-cell interactions (47). Unlike P. mirabilis, swarming in S. liquefaciens cannot be induced by the addition of single amino acids. However, the requirement for sensing and integrating numerous signals to coordinate swarming appears to hold true for P. mirabilis, particularly as surface contact appears to be a requirement for the ability of the cues to promote swarming. As individual amino acids can promote P. mirabilis swarming in PMSM but malate promotes swarming only when other requirements are met (i.e., in a rich medium), a hierarchy of proswarming signals may exist such that as long as certain signals are present, other signals would no longer be necessary. If this is indeed the case, the involvement of quorum-sensing signals in regulation of swarming may warrant revisiting using minimal medium, as the original studies were conducted with LB medium (45), which would satisfy the requirements for a solid surface as well as sufficient concentrations of amino acids and the ability to carry out anaerobic respiration using a complete oxidative TCA cycle (27).

Few connections between histidine and motility exist in the literature outside the role of histidine in phosphotransfer relays. Histidine supports swarming by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, although glutamine did not promote swarming in this species, and arginine repressed swarming, indicating that there are clear differences in swarming cues between species (48, 49). In P. mirabilis, the leucine-responsive regulatory protein Lrp, which is part of a family of transcription factors linking gene regulation to metabolism, contributes to the regulation of swarming (50, 51). Furthermore, the activity of P. mirabilis Lrp is regulated by the relative abundance of serine, threonine, isoleucine, leucine, methionine, and histidine (52). Thus, the ability of histidine to promote swarming may be related to the modulation of Lrp activity, although this hypothesis has yet to be fully explored.

With respect to malate, this cue was capable of promoting swarming only as long as all metabolic requirements for normal swarming were met (i.e., sufficient nutrients and the presence of amino acids, a complete oxidative TCA cycle, and putrescine synthesis). Therefore, the function of malate appears to be linked primarily to the metabolic status of the cell and may simply support the capacity for anaerobic respiration using the complete oxidative TCA cycle, thus fueling the appropriate pathway of energy metabolism required for swarming (27). This would also explain the finding that malate promotes swarming only on complex medium and not minimal medium, as other metabolic requirements for swarming, such as the presence of amino acids in the medium, are not satisfied in PMSM. However, if malate promotes swarming strictly by supporting the oxidative TCA cycle, it might be expected that other TCA cycle intermediates would have a similar capacity to promote swarming, yet our screen did not identify any other TCA cycle intermediates as swarming cues. Therefore, the requirement for malate may be to fuel a particular reaction or to prevent accumulation of other metabolic intermediates, such as fumarate. As PMSM contains a small amount of citrate, P. mirabilis may utilize the citrate in this medium as a carbon and energy source in addition to glycerol, possibly by operating the glyoxylate shunt or the phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) glyoxylate cycle. If this is the case, excess malate would interfere with the function of these pathways, providing an alternate explanation for the failure of this cue to promote swarming on PMSM.

A previous investigation into the nutritional requirements for swarming identified glutamine as one of seven amino acids that made minimal medium permissive for swarming, and the ability to promote swarming was correlated with decreased generation time in liquid culture (29). In the present study, all four amino acid swarming cues made minimal medium permissive for swarming, but only glutamine enhanced the growth rate in this medium. Furthermore, glutamine did not enhance the growth rate in LB broth, even though it promoted swarming on low-salt LB agar, and a detailed analysis of different formulations of minimal medium revealed overall that there is no correlation between growth rate and swarming for P. mirabilis HI4320.

The finding that P. mirabilis requires glnA to swarm under permissive conditions as well as under nonpermissive conditions indicates that glutamine synthetase is critical for swarming in this species. Glutamine synthetase is part of the GS-GOGAT system, normally used for nitrogen assimilation under nitrogen-limiting conditions, while glutamate dehydrogenase (gdhA) is utilized when nitrogen is abundant. As LB medium should not represent a nitrogen-limited growth medium, either P. mirabilis is utilizing GS-GOGAT under conditions that normally favor glutamate dehydrogenase or nitrogen may actually be limited during preparation for swarming. However, as the glnA mutant was fully complemented by l-glutamine and not glutamate or any of the other cues, the data indicate that the swarming defect is not due strictly to a lack of glutamate production but relates more specifically to glutamine levels. This is also in agreement with the finding that glutamate was not identified as a swarming cue. It was further determined that P. mirabilis requires glutamine in excess of ∼0.6 mM in LB agar to swarm, indicating that the ability of this amino acid to promote swarming is likely related to the sensing of glutamine levels or to maintaining the glutamine pool for synthesis of other compounds, such as tryptophan, purine nucleotides, or UDP-acetyl-d-glucosamine, for cell wall biosynthesis.

During infection of the murine urinary tract, P. mirabilis increases expression levels of gdhA and decreases expression levels of glnA (53), suggesting an inverse requirement for these enzymes during infection and swarming. Furthermore, mutation of gdhA results in a fitness defect in the bladder, kidneys, and spleen (53). While the fitness of a glnA mutant has yet to be assessed in the mouse model of infection, in vivo transcriptome data suggest that glutamine synthetase may not contribute significantly to infection. However, the requirement for glnA and excess glutamine for swarming may represent a new target for prevention of P. mirabilis swarming on catheters. Future work will focus on determining the mechanisms of action of each swarming cue to understand how Proteus mirabilis utilizes these factors to sense and respond to the environment, thus gaining new insight into the regulation of swarming and potentially identifying new targets to prevent swarming on catheters.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge helpful comments and critiques from members of the Mobley laboratory and the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, especially Christopher Alteri, Rachel Spurbeck, and Alejandra Yep-Rodriguez. We also acknowledge technical assistance from Samantha Antczak.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01AI059722 and F32AI102552 and utilized directed metabolomics core services supported by NIH grant DK089503 awarded to the University of Michigan.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 January 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.02136-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL, Jr, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Pollock DA, Cardo DM. 2007. Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in US hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep. 122:160–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, Saint S, Schaeffer AJ, Tambayh PA, Tenke P, Nicolle LE. 2010. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 international clinical practice guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:625–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jacobsen SM, Stickler DJ, Mobley HLT, Shirtliff ME. 2008. Complicated catheter-associated urinary tract infections due to Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:26–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mathur S, Sabbuba NA, Suller MT, Stickler DJ, Feneley RC. 2005. Genotyping of urinary and fecal Proteus mirabilis isolates from individuals with long-term urinary catheters. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 24:643–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Warren JW, Tenney JH, Hoopes JM, Muncie HL, Anthony WC. 1982. A prospective microbiologic study of bacteriuria in patients with chronic indwelling urethral catheters. J. Infect. Dis. 146:719–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nicolle LE. 2005. Catheter-related urinary tract infection. Drugs Aging 22:627–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mobley HLT, Warren JW. 1987. Urease-positive bacteriuria and obstruction of long-term urinary catheters. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:2216–2217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Griffith DP, Musher DM, Itin C. 1976. Urease. The primary cause of infection-induced urinary stones. Invest. Urol. 13:346–350 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li X, Zhao H, Lockatell CV, Drachenberg CB, Johnson DE, Mobley HLT. 2002. Visualization of Proteus mirabilis within the matrix of urease-induced bladder stones during experimental urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 70:389–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoeniger JFM. 1965. Development of flagella by Proteus mirabilis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 40:29–42 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams FD, Schwarzhoff RH. 1978. Nature of the swarming phenomenon in Proteus. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 32:101–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Allison C, Hughes C. 1991. Bacterial swarming: an example of prokaryotic differentiation and multicellular behaviour. Sci. Prog. 75:403–422 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jones BV, Young R, Mahenthiralingam E, Stickler DJ. 2004. Ultrastructure of Proteus mirabilis swarmer cell rafts and role of swarming in catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 72:3941–3950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sabbuba N, Hughes G, Stickler DJ. 2002. The migration of Proteus mirabilis and other urinary tract pathogens over Foley catheters. BJU Int. 89:55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Armbruster CE, Mobley HLT. 2012. Merging mythology and morphology: the multifaceted lifestyle of Proteus mirabilis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:743–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morgenstein RM, Szostek B, Rather PN. 2010. Regulation of gene expression during swarmer cell differentiation in Proteus mirabilis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34:753–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rather PN. 2005. Swarmer cell differentiation in Proteus mirabilis. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1065–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Belas R, Suvanasuthi R. 2005. The ability of Proteus mirabilis to sense surfaces and regulate virulence gene expression involves FliL, a flagellar basal body protein. J. Bacteriol. 187:6789–6803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cusick K, Lee YY, Youchak B, Belas R. 2012. Perturbation of FliL interferes with Proteus mirabilis swarmer cell gene expression and differentiation. J. Bacteriol. 194:437–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morgenstein RM, Clemmer KM, Rather PN. 2010. Loss of the waaL O-antigen ligase prevents surface activation of the flagellar gene cascade in Proteus mirabilis. J. Bacteriol. 192:3213–3221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morgenstein RM, Rather PN. 2012. Role of the Umo proteins and the Rcs phosphorelay in the swarming motility of the wild type and an O-antigen (waaL) mutant of Proteus mirabilis. J. Bacteriol. 194:669–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hatt JK, Rather PN. 2008. Characterization of a novel gene, wosA, regulating FlhDC expression in Proteus mirabilis. J. Bacteriol. 190:1946–1955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sturgill G, Rather PN. 2004. Evidence that putrescine acts as an extracellular signal required for swarming in Proteus mirabilis. Mol. Microbiol. 51:437–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liaw S-J, Lai H-C, Wang W-B. 2004. Modulation of swarming and virulence by fatty acids through the RsbA protein in Proteus mirabilis. Infect. Immun. 72:6836–6845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Himpsl SD, Lockatell CV, Hebel JR, Johnson DE, Mobley HLT. 2008. Identification of virulence determinants in uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis using signature-tagged mutagenesis. J. Med. Microbiol. 57:1068–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Falkinham JO, III, Hoffman PS. 1984. Unique developmental characteristics of the swarm and short cells of Proteus vulgaris and Proteus mirabilis. J. Bacteriol. 158:1037–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alteri CJ, Himpsl SD, Engstrom MD, Mobley HL. 2012. Anaerobic respiration using a complete oxidative TCA cycle drives multicellular swarming in Proteus mirabilis. mBio 3(6):e00365–12 doi:10.1128/mBio.00365-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rauprich O, Matsushita M, Weijer CJ, Siegert F, Esipov SE, Shapiro JA. 1996. Periodic phenomena in Proteus mirabilis swarm colony development. J. Bacteriol. 178:6525–6538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jones HE, Park RW. 1967. The influence of medium composition on the growth and swarming of Proteus. J. Gen. Microbiol. 47:369–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wilkerson ML, Niederhoffer EC. 1995. Swarming characteristics of Proteus mirabilis under anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Anaerobe 1:345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Naylor PGD. 1964. Effect of electrolytes or carbohydrates in sodium chloride deficient medium on formation of discrete colonies of Proteus and the influence of these substances on growth in liquid culture. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 27:422–431 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Allison C, Lai HC, Gygi D, Hughes C. 1993. Cell differentiation of Proteus mirabilis is initiated by glutamine, a specific chemoattractant for swarming cells. Mol. Microbiol. 8:53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pearson MM, Sebaihia M, Churcher C, Quail MA, Seshasayee AS, Luscombe NM, Abdellah Z, Arrosmith C, Atkin B, Chillingworth T, Hauser H, Jagels K, Moule S, Mungall K, Norbertczak H, Rabbinowitsch E, Walker D, Whithead S, Thomson NR, Rather PN, Parkhill J, Mobley HLT. 2008. Complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis, a master of both adherence and motility. J. Bacteriol. 190:4027–4037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vinogradov E, Perry MB. 2000. Structural analysis of the core region of lipopolysaccharides from Proteus mirabilis serotypes O6, O48 and O57. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:2439–2446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Belas R, Erskine D, Flaherty D. 1991. Transposon mutagenesis in Proteus mirabilis. J. Bacteriol. 173:6289–6293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pearson MM, Mobley HLT. 2007. The type III secretion system of Proteus mirabilis HI4320 does not contribute to virulence in the mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:1277–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kugler F, Graneis S, Schreiter PP, Stintzing FC, Carle R. 2006. Determination of free amino compounds in betalainic fruits and vegetables by gas chromatography with flame ionization and mass spectrometric detection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 54:4311–4318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lorenz MA, Burant CF, Kennedy RT. 2011. Reducing time and increasing sensitivity in sample preparation for adherent mammalian cell metabolomics. Anal. Chem. 83:3406–3414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Norden AG, Sharratt P, Cutillas PR, Cramer R, Gardner SC, Unwin RJ. 2004. Quantitative amino acid and proteomic analysis: very low excretion of polypeptides >750 Da in normal urine. Kidney Int. 66:1994–2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zaura DS, Metcoff J. 1969. Quantification of seven tricarboxylic acid cycle and related acids in human urine by gas-liquid chromatography. Anal. Chem. 41:1781–1787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Markowski P, Baranowska I, Baranowski J. 2007. Simultaneous determination of L-arginine and 12 molecules participating in its metabolic cycle by gradient RP-HPLC method: application to human urine samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 605:205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fujihara M, Obara H, Watanabe Y, Ono HK, Sasaki J, Goryo M, Harasawa R. 2011. Acidic environments induce differentiation of Proteus mirabilis into swarmer morphotypes. Microbiol. Immunol. 55:489–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sezonov G, Joseleau-Petit D, D'Ari R. 2007. Escherichia coli physiology in Luria-Bertani broth. J. Bacteriol. 189:8746–8749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hauser G. 1885. Über Fäulnissbacterien und deren Beziehungen zur Septicämie; ein Beitrag zur Morphologie der Spaltpilze. Vogel, Leipzig, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schneider R, Lockatell CV, Johnson D, Belas R. 2002. Detection and mutation of a luxS-encoded autoinducer in Proteus mirabilis. Microbiology 148:773–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Belas R, Schneider R, Melch M. 1998. Characterization of Proteus mirabilis precocious swarming mutants: identification of rsbA, encoding a regulator of swarming behavior. J. Bacteriol. 180:6126–6139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Eberl L, Winson MK, Sternberg C, Stewart GS, Christiansen G, Chhabra SR, Bycroft B, Williams P, Molin S, Givskov M. 1996. Involvement of N-acyl-L-hormoserine lactone autoinducers in controlling the multicellular behaviour of Serratia liquefaciens. Mol. Microbiol. 20:127–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kohler T, Curty LK, Barja F, van Delden C, Pechere JC. 2000. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on cell-to-cell signaling and requires flagella and pili. J. Bacteriol. 182:5990–5996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bernier SP, Ha DG, Khan W, Merritt JH, O'Toole GA. 2011. Modulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa surface-associated group behaviors by individual amino acids through c-di-GMP signaling. Res. Microbiol. 162:680–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Calvo JM, Matthews RG. 1994. The leucine-responsive regulatory protein, a global regulator of metabolism in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 58:466–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hay NA, Tipper DJ, Gygi D, Hughes C. 1997. A nonswarming mutant of Proteus mirabilis lacks the Lrp global transcriptional regulator. J. Bacteriol. 179:4741–4746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hart BR, Blumenthal RM. 2011. Unexpected coregulator range for the global regulator Lrp of Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis. J. Bacteriol. 193:1054–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pearson MM, Yep A, Smith SN, Mobley HLT. 2011. Transcriptome of Proteus mirabilis in the murine urinary tract: virulence and nitrogen assimilation gene expression. Infect. Immun. 79:2619–2631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jones BD, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Warren JW, Mobley HL. 1990. Construction of a urease-negative mutant of Proteus mirabilis: analysis of virulence in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 58:1120–1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.