Abstract

Moorella thermoacetica was long the only model organism used to study the biochemistry of acetogenesis from CO2. Depending on the growth substrate, this Gram-positive bacterium can either form H2 or consume it. Despite the importance of H2 in its metabolism, a hydrogenase from the organism has not yet been characterized. We report here the purification and properties of an electron-bifurcating [FeFe]-hydrogenase from M. thermoacetica and show that the cytoplasmic enzyme efficiently catalyzes both H2 formation and H2 uptake. The purified heterotrimeric iron-sulfur flavoprotein (HydABC) catalyzed the coupled reduction of ferredoxin (Fd) and NAD+ with H2 at 55°C at pH 7.5 at a specific rate of about 100 μmol min−1 mg protein−1 and the reverse reaction, the coupled reduction of protons to H2 with reduced ferredoxin and NADH, at a specific rate of about 10 μmol min−1 mg protein−1 in the stoichiometry Fdox + NAD+ + 2H2 ⇋ Fdred2− + NADH + 3H+. When ferredoxin from Clostridium pasteurianum, NAD+, and the enzyme were incubated at pH 7.0 under 100% H2 in the gas phase (E0′ = −414 mV), more than 95% of the ferredoxin (E0′ = −400 mV) was reduced, which indicated that ferredoxin reduction with H2 is driven by the exergonic reduction of NAD+ (E0′ = −320 mV) with H2. In the absence of NAD+, ferredoxin was not reduced. We identified the genes encoding HydABC within the transcriptional unit hydCBAX and mapped the transcription start site.

INTRODUCTION

Until recently, Moorella thermoacetica (formerly Clostridium thermoaceticum) (1) had been the only model organism for the study of the biochemistry of acetogenesis. What we know of the mechanism of the total synthesis of acetate from CO2 is derived mostly from studies of the enzymes in this bacterium by the groups of Wood (2), Ljungdahl (3), Ragsdale (4), Drake (5), and Lindahl (6). Acetate synthesis from CO2 is associated with ATP synthesis, as evidenced by growth of acetogens on H2 and CO2 (7–9). However, despite more than 40 years of intensive investigations, the mechanism of energy conservation is not understood (10).

Acetobacterium woodii was recently introduced as another model organism for the study of energy conservation in acetogens. With this organism, considerable progress in the understanding of the mechanism of energy conservation during growth on H2 and CO2 has been made (11–13). However, A. woodii differs from M. thermoacetica in many respects. M. thermoacetica contains cytochromes, menaquinone, and an electron-bifurcating NAD-dependent reduced ferredoxin:NADP+ oxidoreductase complex (NfnAB) (10, 14, 15), which are not found in A. woodii (12, 16). On the contrary, A. woodii contains an energy-conserving reduced ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase complex (RnfABCDEG [RnfA-G]) and is sodium ion dependent (11, 16), two important properties not shared by M. thermoacetica (4, 17). Apparently, the cytochrome-containing and cytochrome-free acetogens differ in their mechanism of energy conservation, as do cytochrome-containing and cytochrome-free methanogenic archaea (18).

M. thermoacetica ferments glucose to three acetic acids with the concomitant formation of small amounts of H2 (5, 19, 20). The Gram-positive anaerobic bacterium can also grow on H2 and CO2, forming acetic acid as an end product (8, 9). The hydrogenase(s) involved in H2 formation and H2 uptake has not yet been characterized, although it is central to the understanding of the energy metabolism. What is known from biochemical studies is that cell extracts of glucose-grown cells catalyze the coupled reduction of ferredoxin (Fd) and NAD+ with H2, and cell extracts from H2-grown cells additionally catalyze the reduction of NADP+ with H2 (10). The presence of two hydrogenases in M. thermoacetica was shown decades ago by using viologen dyes as an electron acceptor (8, 19, 21).

The genome sequence of M. thermoacetica indicates the presence of two gene clusters that each encode a cytoplasmic heteromeric [FeFe]-hydrogenase and genes encoding a membrane-bound [NiFe]-hydrogenase of the Ech type in association with a formate dehydrogenase (10, 17). The deduced amino acid sequence of one of the heteromeric [FeFe]-hydrogenases shows similarity to the amino acid sequences of the electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent [FeFe]-hydrogenases from Thermotoga maritima (22) and from A. woodii (13); the deduced amino acid sequence of the other heteromeric [FeFe]-hydrogenase shows sequence similarity to the amino acid sequence of NADP+-reducing [FeFe]-hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio fructosovorans (23). The two [FeFe]-hydrogenases also show sequence similarity to each other, which prohibits a prediction of which gene cluster encodes the electron-bifurcating [FeFe]-hydrogenase and which encodes the NADP-reducing [FeFe]-hydrogenase.

To date, two electron-bifurcating [FeFe]-hydrogenases have been characterized, one from T. maritima (22, 24) and one from A. woodii (13). The purified enzyme from T. maritima is a heterotrimer (HydABC) and catalyzes the formation of two H2 molecules from 1 NADH and 1 reduced ferredoxin (Fdred2−), which is thought to be the physiological function in the hyperthermophile growing on glucose. Whether the enzyme can also catalyze the reverse reaction has not been reported. HydA harbors the H cluster (active site), three [4Fe4S] clusters, and two [2Fe2S] clusters; HydB harbors three [4Fe4S] clusters, one [2Fe2S] cluster, and one flavin mononucleotide (FMN); and HydC harbors one [2Fe2S] cluster (24). The purified enzyme from A. woodii is a heterotetrameric (HydABCD) iron-sulfur flavoprotein containing 36 irons and 1 FMN and catalyzes the coupled reduction of NAD+ and ferredoxin with H2, which is thought to be the physiological function in the mesophilic acetogen growing on H2 and CO2. Whether the enzyme can also catalyze the formation of H2 from NADH and Fdred2− has not been investigated (13). Also not answered is the question of whether these heteromeric [FeFe]-hydrogenases from T. maritima and A. woodii catalyze reactions that are not only stoichiometrically but also energetically coupled. Is an endergonic reaction under the experimental conditions used really driven by an exergonic reaction, or are only two exergonic reactions linked to each other? In the case of the enzyme from T. maritima, this question has not been addressed experimentally. In the case of the enzyme from A. woodii, experimental conditions were used (pH 8 and 100% H2 in the gas phase) where the reductions of both ferredoxin from Clostridium pasteurianum (E0′ = −400 mV [pH independent between pH 6.4 and 8.7]) (25) and NAD+ [E0(pH 8) = −350 mV] with H2 [E0(pH 8) = −480 mV] were exergonic.

Flavin-based electron bifurcation was first discovered only several years ago (26, 27). The first example was the cytoplasmic butyryl coenzyme A (CoA) dehydrogenase electron-transferring flavoprotein complex Bcd-EtfAB from Clostridium kluyveri, which catalyzes the coupled reduction of crotonyl-CoA and ferredoxin with 2 NADH, a reaction which appears to be irreversible (28). Also apparently irreversible is the reaction catalyzed by the cytoplasmic electron-bifurcating MvhADG-HdrABC complex from methanogenic archaea that couples the endergonic reduction of ferredoxin with H2 to the exergonic reduction of the heterodisulfide CoM-S-S-CoB with H2 (29). In contrast, the coupled reduction of NAD+ and ferredoxin with 2 NADPH catalyzed by the cytoplasmic electron-bifurcating NfnAB complex from C. kluyveri and M. thermoacetica is fully reversible (10, 30). Only in the cases of the MvhADG-HdrABC complex and the NfnAB complex has it been shown that these two enzymes couple the two reactions not only stoichiometrically but also energetically.

Here we report the purification and properties of the electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent [FeFe]-hydrogenase from M. thermoacetica and show that the reaction catalyzed by the cytoplasmic heterotrimeric enzyme is both reversible and energy coupled. We identified the encoding gene cluster via sequence information obtained by MALDI-TOF MS (matrix-assisted laser desorption–ionization time of flight mass spectrometry) of the trypsin-digested purified enzyme and characterized the transcriptional units. The role of this energy-converting enzyme complex in the acetogenesis of M. thermoacetica is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

M. thermoacetica DSM 521 was cultivated anaerobically at 55°C on glucose with 100% CO2 as the gas phase (10). The cells were harvested by centrifugation under N2 when the optical density at 660 nm (OD660) was about 2.5 and were stored at −80°C until use. C. pasteurianum DSM 525 was grown anaerobically at 37°C on a glucose-ammonium medium (31), and the cells were harvested in the mid-exponential phase.

Biochemicals and enzymes.

NAD+, NADH, NADP+, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), FMN, pyruvate, thiamine pyrophosphate, coenzyme A, and methyl viologen were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH (Taufkirchen, Germany). All materials for protein purification were obtained from GE Healthcare (Freiburg, Germany). Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase was purified from M. thermoacetica (32). Ferredoxin (Fd) (33) and ferredoxin-dependent monomeric [FeFe]-hydrogenase (28) were purified from C. pasteurianum DSM 525.

Purification of the electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent hydrogenase.

The enzyme was purified under strictly anoxic conditions at room temperature in a type B vinyl anaerobic chamber (Coy, Grass Lake, MI), which was filled with 95% N2–5% H2 and contained a palladium catalyst for O2 reduction with H2. All buffers were boiled, flushed with N2, supplemented with 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and maintained under a slight overpressure of N2. Frozen wet cells of M. thermoacetica (7.6 g) were suspended in 15 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) containing 2 mM DTT, 5 μM FAD, and 5 μM FMN (buffer A). After adding 2 mg DNase I and 0.5 mM MgCl2, the cell suspension was passed through a prechilled French pressure cell three times at 120 MPa. Unbroken cells and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 30 min. Membranes were isolated by ultracentrifugation at 150,000 × g at 4°C for 60 min. The supernatant obtained by ultracentrifugation at 150,000 × g containing the cytoplasmic fraction with approximately 33 mg protein ml−1 was used for the purification of ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent hydrogenase. The membrane fraction was resuspended in 15 ml buffer A using a Teflon Potter homogenizer and subsequently centrifuged at 150,000 × g at 4°C for 60 min. After a second wash via the same procedure, the membrane fraction was homogenized in 2 ml buffer A for enzyme assays.

The supernatant obtained by ultracentrifugation at 150,000 × g was loaded onto a DEAE Sepharose Fast Flow column (2.6 cm by 14 cm) equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 150 ml buffer A. Protein was eluted with a 0 to 1 M NaCl linear gradient at a flow rate of 8 ml min−1. The hydrogenase activity was eluted at around 0.24 M NaCl. The fractions containing activity were pooled, concentrated, and desalted by using an Amicon cell with a 50-kDa-cutoff membrane. The concentrate was then applied onto a Q Sepharose high-performance column (2.6 cm by 13 cm) equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 70 ml buffer A. Protein was eluted with a NaCl gradient at a flow rate of 5 ml min−1 (stepwise 0.1 and 0.2 M, linear between 0.2 and 0.3 M, and stepwise 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 M; 90 ml each in buffer A). The hydrogenase activity was recovered in fractions eluting at around 0.26 M NaCl. The fractions were brought to 0.8 M (NH4)2SO4 and loaded onto a Phenyl Sepharose high-performance column (1.6 cm by 15 cm) equilibrated with buffer A containing 0.8 M (NH4)2SO4. Protein was eluted with a stepwise (NH4)2SO4 gradient (0.8, 0.6, 0.4, 0.2, 0.1, and 0 M; 50 ml each in buffer A) at a flow rate of 4 ml min−1. The hydrogenase activity eluted in a peak at 0 M (NH4)2SO4. The pooled fractions were concentrated and desalted with an Amicon cell with a 50-kDa-cutoff membrane. The concentrate was loaded onto a HiTrap Q HP column (5 ml) equilibrated with buffer A containing 5% glycerol. The protein was eluted with a 0 to 1 M NaCl linear gradient (80 ml) at a flow rate of 4 ml min−1. The enzyme eluted in a single peak at around 0.26 M NaCl. The fraction was concentrated, desalted with a 50-kDa-cutoff Amicon filter, and then stored at 4°C in buffer A under an atmosphere of 95% N2–5% H2 until use. During purification, both methyl viologen reduction activity with H2 and NAD+-dependent ferredoxin reduction activity with H2 were monitored.

Enzyme assays.

Enzyme activities were measured under strictly anoxic conditions; 1.5-ml anoxic cuvettes (H2 uptake) or 6.5-ml serum bottles (H2 formation) were sealed with rubber stoppers and filled with 0.8-ml reaction mixtures (see below). N2 (100%) or H2 (100%) at 1.2 × 105 Pa was the gas phase. After the start of the reaction with enzyme or NAD+, NAD(P)+ reduction was monitored spectrophotometrically at 340 nm (ϵ = 6.2 mM−1 cm−1), ferredoxin reduction was monitored at 430 nm (ϵΔox-red ≈ 13.1 mM−1 cm−1), and methyl viologen reduction was monitored at 578 nm (ϵ = 9.8 mM−1 cm−1). One unit was defined as the transfer of 2 μmol electrons min−1.

For the assays, a temperature of 45°C was routinely chosen because the handling of the anoxic cuvettes at 45°C was easier than at 55°C, the growth temperature optimum of M. thermoacetica (at 55°C, you burn your fingers). In a few cases, however, the measurements were done at 55°C, and at this temperature, the activity was found to be twice as high as that at 45°C. Most enzymes increase their activity by a factor of 2 when the temperature is increased by 10°C (Q10 rule). Q10 is the temperature coefficient representing the factor, by which the rate of a reaction increases for every 10μC rise in temperature.

H2 uptake activity.

For H2 uptake activity assays, the reaction mixture contained 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) or potassium phosphate (pH 7.5) and, where indicated, 2 mM DTT and 10 μM FMN. The gas phase was 100% H2. For NAD+-dependent ferredoxin reduction activity, the reaction mixture was supplemented with about 30 μM C. pasteurianum ferredoxin and 1 mM NAD+. For methyl viologen or NAD(P)+ reduction, the reaction mixture was supplemented with 10 mM methyl viologen and/or 1 mM NAD(P)+.

H2 formation activity.

For H2 formation activity assays, the reaction mixture contained 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) or, as indicated, 2 mM DTT, 10 μM FMN, 1 mM NADH, and a reduced ferredoxin-regenerating system (10 mM pyruvate, 0.1 mM thiamine pyrophosphate, 1 mM coenzyme A, 12 μM C. pasteurianum ferredoxin, and 0.3 U pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase). The gas phase was 100% N2. The reaction was started with enzyme or NADH, and the serum bottle was then continuously shaken at 200 rpm to ensure H2 transfer from the liquid phase into the gas phase. Gas samples (0.2 ml) were withdrawn every 1 min, and H2 was quantified by gas chromatography.

Pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase.

The reaction mixture for pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase assays contained 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM DTT, 10 mM pyruvate, 0.1 mM thiamine pyrophosphate, 1 mM coenzyme, and about 30 μM C. pasteurianum ferredoxin or 10 mM methyl viologen as the electron acceptor. The gas phase was 100% N2.

Analytical methods.

Protein concentration was determined by using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Munich, Germany), with bovine serum albumin as the standard. SDS-PAGE analysis was performed on 12% Mini-Protean TGX precast gels (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G250.

The SDS-PAGE protein bands were excised and digested with sequencing-grade modified trypsin (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). The resulting peptide mixture was injected onto a PepMap100 C18 RP nanocolumn (Dionex, Idstein, Germany) and separated on an UltiMate 3000 liquid chromatography system (Dionex) in a continuous acetonitrile gradient. A Probot microfraction collector (Dionex) was used to spot liquid chromatography-separated peptides onto a MALDI target, mixed with matrix solution (alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid). MALDI-TOF-TOF analysis was carried out on a 4800 Proteomics analyzer (Applied Biosystems/MDS Sciex, Foster City, CA). Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) data were searched against an in-house protein sequence database by using Mascot (Matrixscience, United Kingdom) embedded into GPS explorer software.

The relative molecular mass of the purified hydrogenase was measured by gel filtration on a Superdex 200HR column (1.0 cm by 30 cm) calibrated with Gel Filtration Calibration Kit HMW (high molecular weight; GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany), equilibrated with buffer A containing 300 mM NaCl and run at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1.

The iron content of the purified enzyme was determined colorimetrically with 3-(2-pyridyl)-5,6-bis(5-sulfo-2-furyl)-1,2,4-triazinedisodium trihydrate (Ferene; Sigma) (30). For identification of flavin and measurement of the flavin content of the enzyme, the purified enzyme was first washed by ultrafiltration with a 20-fold volume of flavin-free buffer A. The washed enzyme was then heat denatured in a boiling-water bath for 10 min in the dark. After cooling, the denatured protein was removed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min. For identification of the flavin in the enzyme, the supernatant was analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on an RP-18 F254 aluminum sheet (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), with FAD and FMN as the standards. The TLC plate was developed with an aqueous solution containing 85% 5 mM ammonium formate and 15% methanol. The presence of flavin was determined by irradiation with UV light. For quantification of flavin in the enzyme, the UV-visible (UV-Vis) spectrum of the supernatant of the denatured protein was recorded on a UV-1650PC spectrophotometer (Shimadazu, Japan), and the amount of FMN was calculated by using a molar extinction coefficient at 446 nm of 12,200 M−1 cm−1 (34).

The H2 content in the gas phase was measured on a gas chromatograph equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (Carlo Erba GC series 6000) and a ShinCarbon ST micropacked column (82/100 mesh, 2.0 mm by 2 m; Restek GmbH, Germany). The oven and injection port temperatures were set at 100°C; the detector was set at 150°C. N2 was used as the carrier gas, and the flow rate was 34 ml min−1. The amount of H2 was calculated according to the standard curve correlated with peak areas.

RNA isolation and cotranscription analysis by RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from M. thermoacetica cells grown exponentially on glucose plus CO2 and harvested at an OD660 of 2.0. For RNA extraction, TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany) was used according to the manufacturer's protocol. After treatment with RNase-free DNase I (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany), samples of 3 μg RNA were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1.0% agarose gel to assess the integrity of the RNA. Cotranscription of the hydABC genes and their neighboring genes was analyzed by using reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) to amplify the intergenic regions, using the ProtoScript M-MuLV Taq RT-PCR kit (New England BioLabs, Frankfurt, Germany) as recommended by the manufacturer. The random primer provided in the kit was used for reverse transcription. The resulting cDNA was used as a template to amplify the intergenic region of every pair of neighboring genes. The specific primers used for amplification are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Genomic DNA and total RNA were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Determination of the transcription start site.

The transcription start site of the hydCBAX operon was determined by 5′ random amplification of cDNA ends (RACE), using a 5′/3′ RACE kit (second generation) from Roche (Mannheim, Germany), as described in the manual. First-strand cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription with hydC-specific primer 1. After poly(A) tailing of the first-strand cDNA, the product was amplified with hydC-specific primer 2 and an oligo(dT) anchor primer provided in the kit. Nested PCR was then performed with hydC-specific primer 3 and the PCR anchor primer provided in the kit. After two rounds of amplification, a PCR product band was visible after electrophoresis in a 1.0% agarose gel. The final products were cloned into a pCR-Blunt vector (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany), which was subsequently introduced into competent TOP10 cells by transformation. After amplification, the inserted PCR product was sequenced to identify the transcriptional start site. The three specific primers used here are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The M. thermoacetica genome GenBank accession number is CP000232.1.

RESULTS

We previously showed that cell extracts of M. thermoacetica grown on glucose and harvested at the beginning of the stationary phase catalyze the NAD+-dependent reduction of ferredoxin (Fd) with H2 with a specific activity of 0.1 U/mg and the reduction of methyl viologen with H2 with a specific activity of 0.4 U/mg. Both activities were associated with the cytoplasmic cell fraction (10). In the meantime, we found that the specific activity of the ferredoxin- and NAD+-dependent hydrogenase as well as that of the methyl viologen-reducing hydrogenase were 10-fold higher in glucose-grown cells harvested in the exponential growth phase. From such cells, we purified the electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent hydrogenase (Table 1). In all of the following experiments, ferredoxin from C. pasteurianum was used. This ferredoxin has two [4Fe4S] clusters, both of which are reduced by 1 electron at a redox potential (E0′) of −400 mV (35), and the redox potential is pH independent from pH 6.4 to 8.7 (25).

Table 1.

Purification (43-fold) of electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent [FeFe]-hydrogenase from M. thermoacetica grown on glucose under 100% CO2a

| Purification step | Total protein (mg) | Hydrogenase activity |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MV reduction |

NAD+-dependent Fd reduction |

||||

| Utotal | U/mg | Utotal | U/mg | ||

| Cell extract (150,000 × g) | 560 | 2,420 | 4.3 | 735 | 1.3 |

| DEAE Sepharose | 96 | 1,610 | 16.8 | 547 | 5.7 |

| Q Sepharose | 23 | 1,260 | 55 | 435 | 19.0 |

| Phenyl Sepharose | 2.7 | 440 | 163 | 143 | 53.0 |

| HiTrap Q HP | 2.1 | 380 | 181 | 122 | 55.8 |

The purification yield was 16%. MV, methyl viologen; Fd, ferredoxin from C. pasteurianum. Activities were measured spectrophotometrically in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) at 45°C with 100% H2 at 1.2 × 105 Pa as the gas phase. One unit equals 2 μmol electrons transferred per min.

Purification of the electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent hydrogenase.

Purification was achieved by anion-exchange chromatography (DEAE Sepharose, Q Sepharose, and HiTrap Q HP) and hydrophobic chromatography (Phenyl Sepharose), starting with the supernatant obtained by centrifugation at 150,000 × g. During purification, we monitored both the reduction of methyl viologen with H2 and the NAD+-dependent reduction of ferredoxin with H2 (Table 1). The enzyme was purified 43-fold, with a yield of 16%. The purification factor and yield were independent of whether the hydrogenase activity was measured with methyl viologen or with ferredoxin plus NAD+, which indicates that in the cytoplasm of glucose-grown cells, only one type of hydrogenase that catalyzes both methyl viologen reduction and H2-driven NAD-dependent ferredoxin reduction was present. Consistently, NADP-reducing hydrogenase activity, which is present in cell extracts (supernatant obtained by centrifugation at 115,000 × g) of H2/CO2-grown cells and which also catalyzes the reduction of methyl viologen with H2 (10), was undetectable in the cell extract of glucose-grown cells (Table 2). In the glucose-grown cells, the genes for the membrane-associated Ech-type [NiFe]-hydrogenase (see the introduction) were also apparently not expressed, as indicated by the finding that the pellet of the cell extract obtained by centrifugation at 150,000 × g, after washing of the pellet by resuspension in buffer and recentrifugation, was essentially devoid of methyl viologen-reducing hydrogenase activity. All [NiFe]-hydrogenases known to date catalyze the reduction of methyl viologen with H2.

Table 2.

Specific activities at 45°C of the electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent [FeFe]-hydrogenase (HydABC) from M. thermoaceticad

| Reaction | Hydrogenase activity (U/mg) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract (150,000 × g) at pH 7.5 | Purified enzyme |

||

| pH 7.5 | pH 7.0 | ||

| H2 → MVox | 3.6 | 195 | |

| H2 → NAD+ + MVox | 2.6a | 195 | |

| H2 → NAD+ + Fdox | 1.1 | 57.5 | 49.7 |

| H2 → Fdox | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| H2 → NAD+ | 0.2 | <0.01 | |

| H2 → NADP+ + Fdox | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| H2 → NADP+ | 0.01 | <0.01 | |

| NADH + Fdredb → H2 | 0.1 | 4.6 | 7.8 |

| NADH → H2 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| Fdredb → H2 | 0.015 | 0.2c | |

The cell extracts catalyzed the reduction of NAD+ with reduced methyl viologen.

Fdred-regenerating system (ferredoxin from C. pasteurianum, pyruvate, thiamine pyrophosphate, coenzyme A, and pyruvate:Fd oxidoreductase from M. thermoacetica).

This activity cannot be explained only by the fact that the ferredoxin preparations from C. pasteurianum used were contaminated with trace amounts of monomeric [FeFe]-hydrogenase catalyzing the formation of H2 with reduced ferredoxin. For that, the activity was much too high.

At the growth temperature optimum of M. thermoacetica of 55°C, the specific activities were approximately 2-fold higher (see the text). MV, methyl viologen; Fd, ferredoxin from C. pasteurianum. The activities were measured in 100 mM potassium phosphate at pH 7.5 or pH 7.0, as indicated. One unit equals 2 μmol electrons transferred per min. Important activities are printed in boldface type.

The hydrogenase had to be purified under strictly anoxic conditions because the enzyme was inactivated in the presence of even trace amounts of O2. All buffers used were supplemented with FMN and FAD. When the flavins were omitted, the purification yields were very low.

Molecular properties.

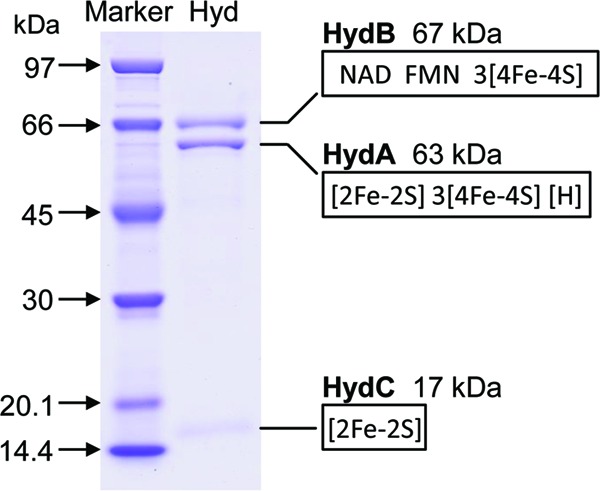

SDS-PAGE of the purified hydrogenase revealed three proteins with apparent molecular masses of 67, 63, and 17 kDa (Fig. 1). A scan of the Coomassie blue-stained bands was consistent with a 1:1:1 stoichiometry. The apparent molecular mass of the enzyme determined by gel exclusion chromatography was near 300 kDa, which indicated that the native enzyme is a dimer of the heterotrimer (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Fig 1.

SDS-PAGE of purified electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent [FeFe]-hydrogenase (HydABC) from M. thermoacetica. The encoding genes were identified by MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the three protein bands after digestion with trypsin. The molecular masses and cofactor binding sites of the three subunits were deduced from the amino acid sequences. [H], [6Fe4S] cluster, the active site of [FeFe]-hydrogenases.

Sequence information obtained by MALDI-TOF MS of the three trypsin-digested proteins indicated that the three proteins were encoded by a gene cluster in M. thermoacetica annotated hydCBA. The deduced amino acid sequences of the proteins show sequence identity to the sequences of the HydA (43%), HydB (49%), and HydC (39%) proteins of the hyperthermophilic bacterium T. maritima, which form a heterotrimeric electron-bifurcating [FeFe]-hydrogenase (22, 24). The deduced amino acid sequence of HydABC from M. thermoacetica shows an even higher identity to that of the electron-bifurcating HydABCD complex of A. woodii (13). The fourth subunit, HydD, in the enzyme of A. woodii, which lacks a cofactor binding site, shows sequence similarity to the N-terminal part of HydB of M. thermoacetica (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Cofactor content.

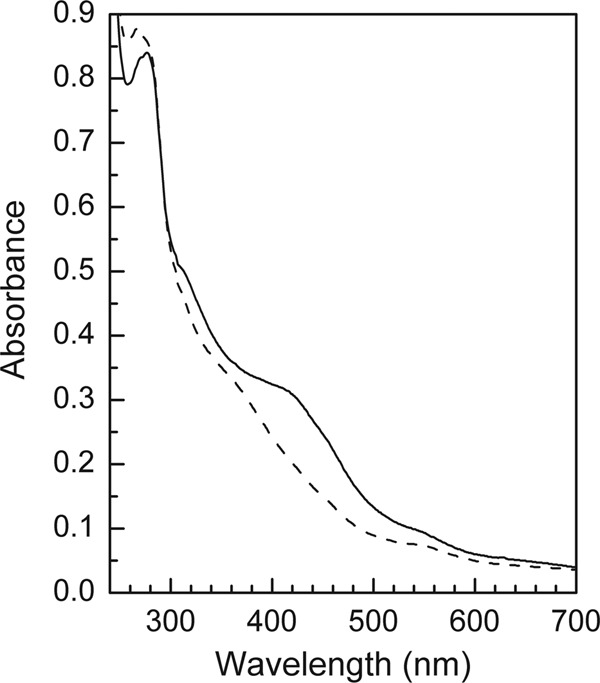

After washing in flavin-free buffer, the purified hydrogenase was found to contain 211.3 nmol nonheme iron and 5.3 nmol FMN mg protein−1, equivalent to 31 irons and 0.8 FMN per heterotrimer. FAD was not detected. Deduced from the M. thermoacetica genome sequence, HydA (63 kDa) is predicted to harbor the H cluster, i.e., the [6Fe4S] hydrogenase active site, three [4Fe4S] clusters, and one [2Fe2S] cluster. HydB (67 kDa) is predicted to harbor three [4Fe4S] clusters, a flavin binding site, and an NAD binding site. HydC (17 kDa) is predicted to harbor one [2Fe2S] cluster (Fig. 1). Altogether, the iron in the clusters adds up to 34 per mol heterotrimer. The UV-Vis spectra of the enzyme isolated under 5% H2 and of the enzyme after partial oxidation by removal of the H2 are characteristic of iron-sulfur flavoproteins (Fig. 2). After partial oxidation, the enzyme could be rereduced with H2. The enzyme from M. thermoacetica appears to contain two [2Fe2S] clusters less than the enzyme from T. maritima and one [2Fe2S] cluster less than the enzyme from A. woodii (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Why this is so is presently not understood.

Fig 2.

The UV-visible absorption spectra of the electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent [FeFe]-hydrogenase from M. thermoacetica. The sample contained about 2.3 mg of protein per ml 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6). The dashed line indicates the sample isolated in the anaerobic chamber containing 5% H2–95% N2; the solid line indicates that the gas phase of the sample was changed to 100% N2.

Catalytic properties.

The purified hydrogenase catalyzed the coupled reduction of NAD (1 mM) and ferredoxin (30 μM) with H2 (100% in the gas phase) at 45°C at pH 7.5 with a specific activity of 55 U/mg. At pH 7.0, the specific activity was 50 U/mg (Table 2). The rate of the reaction was proportional to the protein concentration in the range tested (not shown) and followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics. The rate was hyperbolically dependent on the H2 and NAD concentrations, with apparent Km values for H2 of about 6% in the gas phase and for NAD+ of about 0.2 mM NAD+ (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). At the growth temperature optimum of M. thermoacetica of 55°C, the specific activity was 100 U/mg at pH 7.5, which is twice as high as that at 45°C, the temperature at which, for practical reasons, the activity was routinely measured (see Materials and Methods).

The purified enzyme catalyzed the reduction of methyl viologen with H2 at pH 7.5 at 45°C with a specific activity of almost 200 U/mg (Table 2). At a methyl viologen concentration of either 10 mM or 0.1 mM, the reduction of the viologen dye was independent of the presence of NAD, indicating that the viologen dye as one electron donor/acceptor uncouples the electron bifurcation mechanism (29).

The purified enzyme catalyzed the reverse reaction—the formation of H2 from NADH and reduced ferredoxin—at a specific rate of 4.6 μmol min−1 mg protein−1 at pH 7.5 and at 7.8 μmol min−1 mg protein−1 at pH 7.0 at 45°C (Table 2). At 55°C, the specific rate at pH 7.5 was 10 μmol min−1 mg−1.

The specific activity of ferredoxin and NAD reduction with H2 decreased when the pH was lowered from 7.5 to 6.5, whereas that of the reverse reaction increased. This can be explained by the fact that the reduction of ferredoxin and NAD+ with H2 is associated with the formation of protons, and the reverse reaction is associated with the consumption of protons (see reaction 1 below).

The assay mixtures always contained FMN (10 μM), which stimulated the activity up to 2-fold depending on how thoroughly the enzyme preparation was washed free of flavins. FAD (10 μM) also stimulated the activity albeit to a lesser extent than FMN. Even at higher concentrations, FAD stimulated the activities less than FMN, indicating that the stimulatory effect of FAD was not the result of the FAD preparation containing small amounts of FMN formed by FAD hydrolysis. As indicated above, the purified enzyme contained only FMN, although it was purified in the presence of both FMN and FAD. The results thus indicated that the hydrogenase can use both FMN and FAD as cofactors, with a strong preference for FMN.

Stoichiometry.

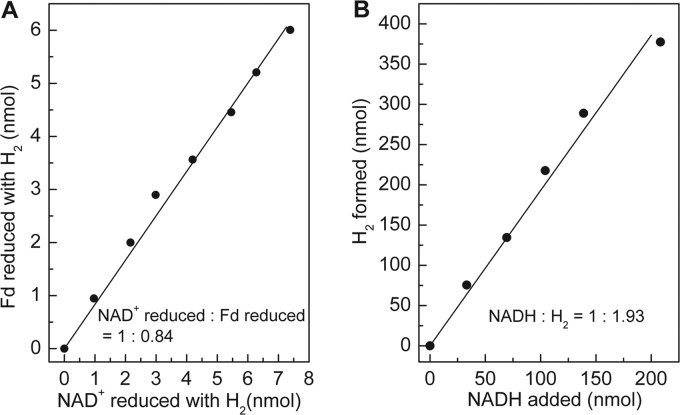

We determined the stoichiometry of ferredoxin and NAD+ reduction with H2 by monitoring both the reduction of NAD+ at 340 nm and the reduction of ferredoxin at 430 nm. This is possible because upon reduction, C. pasteurianum ferredoxin does not change its absorbance significantly at 340 nm, and NADH does not absorb at 430 nm. Per mol NAD+ reduced, 0.84 mol ferredoxin was reduced (Fig. 3A). The same stoichiometry was found when the mole amounts of ferredoxin reduced with H2 per mol NAD+ added was determined (not shown). The stoichiometry of H2 formation from reduced ferredoxin and NADH was determined by measuring the mole amounts of H2 generated from fully reduced ferredoxin per mol of NADH added. In the experiment, ferredoxin was kept fully reduced by a regenerating system composed of pyruvate, pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase, and coenzyme A. Per mol NADH, about 2 mol H2 was formed (Fig. 3B). The results indicated that HydABC catalyzes the following reversible reaction:

| (1) |

Fig 3.

Stoichiometry of the reactions catalyzed by electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent [FeFe]-hydrogenase from M. thermoacetica. (A) NAD+ and C. pasteurianum ferredoxin (Fd) reduction with H2. The reaction took place in anoxic cuvettes and was monitored simultaneously at 340 nm (for NAD+ reduction) and 430 nm (for ferredoxin reduction). The gas phase was H2 at 1.2 × 105 Pa. The absorbance change at 340 nm caused by ferredoxin reduction was very small and could therefore be ignored. The amount of NADH and reduced ferredoxin was calculated based on their molar extinction coefficients (ϵ340 nm = 6.2 mM−1 cm−1 for NAD+; ϵΔox-red430 nm = 13.1 mM−1 cm−1 for ferredoxin). (B) NADH-dependent H2 formation in the presence of an excess amount of reduced ferredoxin. The reaction took place in 6.5-ml anoxic serum bottles sealed with rubber stoppers and containing 0.8 ml of the reaction mixture. The gas phase was N2 at 1.2 × 105 Pa. The reduced ferredoxin was supplied by a regenerating system containing 20 μM ferredoxin, 10 mM pyruvate, 0.1 mM thiamine pyrophosphate, 1 mM coenzyme A, and about 0.3 U of pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase purified from M. thermoacetica. The amount of H2 was quantified via gas chromatography.

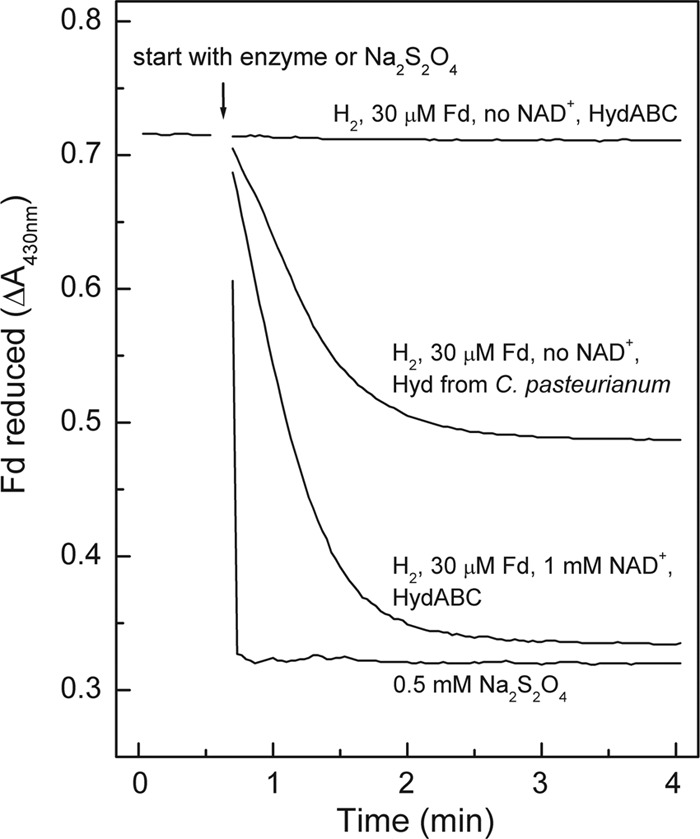

Energetic coupling.

The coupling of the endergonic reduction of ferredoxin with H2 to the exergonic reduction of NAD+ with H2 was demonstrated by showing that at pH 7.0, ferredoxin (E0′ = −400 mV) was reduced to more than 95% by H2 (100% in the gas phase; E0′ = −414 mV) in the presence of HydABC from M. thermoacetica and NAD+ but only to about 55% in the presence of the monomeric [FeFe]-hydrogenase from C. pasteurianum (Fig. 4). The C. pasteurianum hydrogenase, which is not electron bifurcating, catalyzes the reversible reduction of ferredoxin with H2 in the absence of NAD+. Under the experimental conditions used, equilibrium is achieved in the presence of this [FeFe]-hydrogenase when 55% of the ferredoxin is reduced. Any further reduction must therefore be energy driven.

Fig 4.

Fd reduction with H2 catalyzed by the electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent [FeFe]-hydrogenase (HydABC) from M. thermoacetica. As controls, Fd reduction with 100% H2 catalyzed by the monomeric Fd-dependent [FeFe]-hydrogenase (Hyd) from C. pasteurianum as well as the spontaneous reduction of Fd with sodium dithionite were used. The reactions took place in 1.5-ml anoxic cuvettes filled with 0.8 ml 100 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS)-KOH (pH 7.0) containing 30 μM Fd from C. pasteurianum and, where indicated, C. pasteurianum monomeric [FeFe]-hydrogenase (∼0.02 units), M. thermoacetica HydABC (∼0.04 units), or 0.5 mM sodium dithionite. The gas phase was 100% H2 at 1.2 × 105 Pa. The temperature was 45°C. The reactions were started by the addition of enzyme or dithionite. With dithionite, 100% of the Fd was reduced, and with H2 plus C. pasteurianum Hyd, about 55% of the Fd was reduced.

Encoding genes.

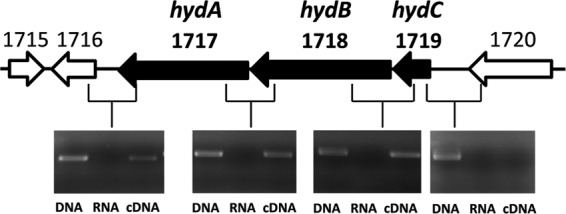

As indicated above, HydABC from M. thermoacetica is encoded by the gene cluster hydCBA (Fig. 5). The open reading frame upstream of the cluster (Moth_1720 [Moth for Moorella thermoacetica]) is predicted to encode an O-methyltransferase, and the open reading frame downstream of the cluster (Moth_1716) is predicted to encode a hydrolase. RT-PCR analysis suggests that the genes hydC, hydB, hydA, and orf1716 (the hydrolase gene, now designated hydX) form a transcriptional unit (Fig. 5). The function of the hydrolase is unknown. A homolog of hydX is not found in the genomes of A. woodii and T. maritima, which synthesize a closely related electron-bifurcating hydrogenase. Studies to unravel the function of HydX were not performed.

Fig 5.

Cotranscription of hydABC in M. thermoacetica shown by RT-PCR analysis. After reverse transcription, cDNA (third lane) was used as the template to amplify the intergenic regions. Genomic DNA (first lane) and total RNA (second lane) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Moth_1720, Moth_1716, and Moth_1715 are annotated in GenBank as genes encoding an O-methyltransferase, a hydrolase, and a transcriptional regulator belonging to the XRE family, respectively.

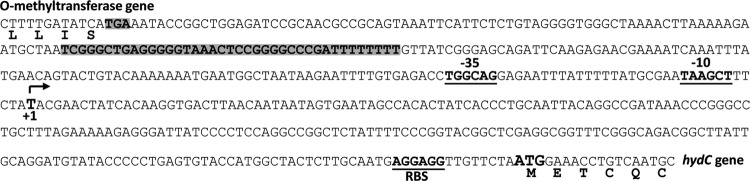

In the region between the stop codon of the O-methyltransferase gene and the start codon of hydC, a transcriptional terminator, putative −35 and −10 promoter sequences, the transcription start site, and the ribosome binding site (RBS) were identified or predicted from the DNA sequence (Fig. 6). We determined the transcription start site using the 5′ RACE method. In the region between the stop codon of hydA and the start codon of the hydrolase gene hydX, a transcriptional terminator, a promoter region, and a ribosome binding site were predicted by Softberry software (Softberry, Inc., New York, NY) (not shown). HydABC activity is found in both glucose- and H2/CO2-grown cells (10).

Fig 6.

Mapping of the transcription start site of hydCBAX from M. thermoacetica using 5′ RACE. The transcription start site (+1), putative ribosome binding site (RBS), and extended −10 and −35 promoter sequences are indicated. The stop codon and the putative transcription terminator of the upstream O-methyltransferase gene are shaded gray. The putative transcription terminator was predicted by using the software provided by the ARNold finding terminators at the IGM-Web server (http://rna.igmors.u-psud.fr/toolbox/arnold/index.php) as well as the PEPPER Transcription Terminator Prediction toolbox of the University of Groningen, the Netherlands (http://pepper.molgenrug.nl/).

As indicated in the introduction, the genome of M. thermoacetica harbors two gene clusters encoding multimeric [FeFe]-hydrogenases, namely, Moth_1717 to Moth_1719 and Moth_1883 to Moth_1888. Since Moth_1717 to Moth_1719 has been shown to code for the electron-bifurcating ferredoxin- and NAD-dependent [FeFe]-hydrogenase, the second cluster must code for the NADP-reducing hydrogenase synthesized only when the cells grow on H2 and CO2 (10).

DISCUSSION

The purified HydABC complex from M. thermoacetica was found to catalyze the reversible coupled reduction of NAD+ and ferredoxin with 2H2 (reaction 1) and the reduction of methyl viologen with H2. Under the experimental conditions used, the reduction of ferredoxin to more than 95% with H2 (105 Pa = 100% H2 in the gas phase) was endergonic and therefore possible only if energetically coupled to the exergonic reduction of NAD+ with H2 (Fig. 4).

The specific activity of the purified enzyme was about 100 U/mg in the H2 uptake direction and about 10 U/mg in the H2 formation direction at the growth temperature optimum of 55°C (Table 2). For comparison, the specific activity of the coupled ferredoxin and NAD reduction with H2 catalyzed by the enzyme from A. woodii was reported previously to be 4 U/mg at its growth temperature optimum of 30°C (13), and the specific activity of H2 formation from NADH and reduced ferredoxin catalyzed by the enzyme from T. maritima was reported previously to be 10 U/mg at its growth temperature optimum of 80°C (22).

The experiments with the enzyme from M. thermoacetica were performed with ferredoxin from C. pasteurianum (E0′ = −400 mV). It was shown 50 years ago that ferredoxins from different organisms are functionally interchangeable in vitro (36, 37). With ferredoxin from C. pasteurianum, the free energy change, ΔG°′, associated with reaction 1 under physiological standard conditions (pH 7.0) is −21 kJ mol−1. Such a free energy change indicates that the HydABC complex should catalyze the oxidation of H2 at pH 7 with a higher catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) than the formation of H2. This is predicted by the Haldane equation (38), which relates catalytic efficiencies of enzyme-catalyzed forward and back reactions to the equilibrium constant of the reaction. Although for the HydABC complex, we determined specific activities and apparent Km only under standard assay conditions, and although the apparent Km for H2 with methyl viologen as the electron acceptor is not necessarily the same as the Km with ferredoxin plus NAD, the results do confirm that at pH 7, the H2 oxidation reaction is kinetically favored when ferredoxin from C. pasteurianum is used as the electron acceptor.

For M. thermoacetica, a ferredoxin similar to that of C. pasteurianum was shown to be involved in ferredoxin-dependent reactions, such as the CO dehydrogenase reaction (39, 40). The M. thermoacetica ferredoxin (Fd-II) also harbors two [4Fe4S] clusters but differs from C. pasteurianum ferredoxin in that the two clusters have two different midpoint potentials, −454 mV and −487 mV (39), rather than both having the same midpoint potential of −400 mV, as in the case of the C. pasteurianum ferredoxin (35). With ferredoxin from M. thermoacetica, reaction 1 under physiological standard conditions (pH 7.0) is exergonic by only −7 kJ mol−1. Unfortunately, Fd-II from M. thermoacetica was not available to test these predictions. However, when the crystal structure of the electron-bifurcating [FeFe]-hydrogenase in complex with ferredoxin is determined, Fd-II from M. thermoacetica will have to be used.

The pH optimum for growth of M. thermoacetica is pH 6.8 (5). The intracellular pH of M. thermoacetica is probably somewhat lower because the fermentation product acetic acid is a weak acid (pKa = 4.7), which in the undissociated form can freely diffuse through the cytoplasmic membrane and lower the cytoplasmic pH (41, 42). At pH <7, the free energy change of reaction 1 with ferredoxin from M. thermoacetica approaches ±0 kJ mol−1. For a ΔG°′ of 0 kJ mol−1, the Haldane equation predicts that the catalytic efficiencies of the HydABC complex in the catalysis of the forward and back reactions are equal.

What is the situation in vivo? During growth of M. thermoacetica on glucose under an atmosphere of 100% CO2, small amounts of H2 are formed (19, 20), and under these growth conditions, only the HydABC complex was found to be present. Almost 100% of the H2:methyl viologen oxidoreductase activity in cell extracts was associated with the HydABC complex (Table 2). Neither the activities of cytoplasmic NADP-reducing hydrogenase nor those of membrane-associated Ech hydrogenase, which both also catalyze methyl viologen reduction with H2, could be detected. In glucose-grown cells, HydABC thus most probably is the enzyme responsible for H2 formation. In previous studies, it was shown by native gel electrophoresis that in glucose-plus-CO2-grown cells, there appears to be only one methyl viologen-reducing hydrogenase activity (19, 21).

The NADH and the reduced ferredoxin required for H2 formation via HydABC are regenerated during glucose oxidation to 2 acetic acid and 2 CO2 in the NAD-specific glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase reaction (10, 43) and the pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase reaction (32, 44). Since most of the NADH and reduced ferredoxin are reoxidized during the reduction of 2 CO2 to acetic acid (10), the HydABC complex probably has the function of a valve that allows glucose oxidation and thus ADP phosphorylation when CO2 reduction to acetic acid becomes rate limiting.

During growth of M. thermoacetica on H2 and CO2, the situation is different. In cells grown in the presence of H2, activities of HydABC and of NADP-reducing hydrogenase are found (10). During growth on H2 and CO2, the reduction of ferredoxin with H2 via HydABC is most probably the only reduced ferredoxin-regenerating reaction, which is required for the reduction of CO2 to CO as an intermediate in the total synthesis of acetate from 2 CO2. In principle, ferredoxin could also be reduced with NADPH via the NfnAB complex, which is thought, however, to have a function in NADPH regeneration from reduced ferredoxin and NADH rather than in ferredoxin reduction (10). Thus, depending on the growth conditions, the HydABC complex in M. thermoacetica catalyzes either the formation of H2 (during growth on glucose) or its uptake (during growth on H2 and CO2). The only other hydrogenase shown to operate in both directions in vivo in one organism is the cytoplasmic F420-reducing hydrogenase in some methanogenic archaea (45). This enzyme catalyzes the uptake of H2 during growth of these methanogens on H2 and CO2 and the formation of H2 during growth on formate.

For A. woodii, which grows on H2 and CO2 and forms acetic acid, the finding of an electron-bifurcating hydrogenase complex, HydABCD, allowed the formulation of an energy metabolism in which the oxidation and reduction reactions are balanced and in which CO2 reduction to acetic acid is coupled with energy conservation (12, 13). Key to the understanding are the presence of NAD-specific methylene-tetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase, NAD-specific methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase (46, 47), and a membrane-associated energy-conserving reduced ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase (RnfA-G complex) (11). In M. thermoacetica, the methylene-tetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase is NADP specific (48, 49). The physiological electron donor of methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase is not known (10), and an energy-converting RnfA-G complex is lacking (17). In M. thermoacetica, it thus remains unknown how the NAD+ required in the reaction catalyzed by HydABC during growth of the organism on H2 and CO2 is regenerated.

From the genome sequence of M. thermoacetica (17), it is predicted that this organism could contain a membrane-associated, energy-converting hydrogenase of the Ech type, which in some organisms catalyzes the proton motive force-driven reduction of ferredoxin with H2 and in others catalyzes the reduction of protons with reduced ferredoxin to H2 coupled with the buildup of a proton motive force (45). This Ech-type hydrogenase is the only energy-converting membrane complex predicted from the genome of M. thermoacetica that could operate within the redox potential range set by the substrates and intermediates involved in CO2 reduction with H2 to acetic acid. The most negative E0′ of −520 mV is of the CO2/CO couple (50), and the most positive E0′ of −200 mV is of the methylene-tetrahydrofolate/methyl-tetrahydrofolate couple (51). The redox potential of menaquinone found in M. thermoacetica (14, 15) is −75 mV and is thus far too positive to be involved in electron transport between CO and methylene-tetrahydrofolate (52). If and how the Ech complex is involved in CO2 reduction with H2 to acetic acid in M. thermoacetica are important questions that need to be answered before a function of the electron-bifurcating hydrogenase HydABC in M. thermoacetica during growth on H2 and CO2 can definitely be assigned.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Max Planck Society and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

We thank Johanna Moll for growing C. pasteurianum and purifying its ferredoxin and Wolfgang Buckel for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 January 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.02158-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Collins MD, Lawson PA, Willems A, Cordoba JJ, Fernandez-Garayzabal J, Garcia P, Cai J, Hippe H, Farrow JA. 1994. The phylogeny of the genus Clostridium: proposal of five new genera and eleven new species combinations. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:812–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wood HG. 1991. Life with CO or CO2 and H2 as a source of carbon and energy. FASEB J. 5:156–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ljungdahl LG. 2009. A life with acetogens, thermophiles, and cellulolytic anaerobes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63:1–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ragsdale SW, Pierce E. 2008. Acetogenesis and the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway of CO2 fixation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784:1873–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Drake HL, Daniel SL. 2004. Physiology of the thermophilic acetogen Moorella thermoacetica. Res. Microbiol. 155:869–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lindahl PA. 2012. Metal-metal bonds in biology. J. Inorg. Biochem. 106:172–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balch WE, Schoberth S, Tanner RS, Wolfe RS. 1977. Acetobacterium, a new genus of hydrogen-oxidizing, carbon dioxide-reducing, anaerobic bacteria. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 27:355–361 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Daniel SL, Hsu T, Dean SI, Drake HL. 1990. Characterization of the H2- and CO-dependent chemolithotrophic potentials of the acetogens Clostridium thermoaceticum and Acetogenium kivui. J. Bacteriol. 172:4464–4471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kerby R, Zeikus JG. 1983. Growth of Clostridium thermoaceticum on H2/CO2 or CO as energy source. Curr. Microbiol. 8:27–30 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huang H, Wang S, Moll J, Thauer RK. 2012. Electron bifurcation involved in the energy metabolism of the acetogenic bacterium Moorella thermoacetica growing on glucose or H2 plus CO2. J. Bacteriol. 194:3689–3699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Biegel E, Müller V. 2010. Bacterial Na+-translocating ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:18138–18142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Poehlein A, Schmidt S, Kaster AK, Goenrich M, Vollmers J, Thürmer A, Bertsch J, Schuchmann K, Voigt B, Hecker M, Daniel R, Thauer RK, Gottschalk G, Müller V. 2012. An ancient pathway combining carbon dioxide fixation with the generation and utilization of a sodium ion gradient for ATP synthesis. PLoS One 7:e33439 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schuchmann K, Müller V. 2012. A bacterial electron-bifurcating hydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 287:31165–31171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Das A, Hugenholtz J, Van Halbeek H, Ljungdahl LG. 1989. Structure and function of a menaquinone involved in electron transport in membranes of Clostridium thermoautotrophicum and Clostridium thermoaceticum. J. Bacteriol. 171:5823–5829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gottwald M, Andreesen JR, LeGall J, Ljungdahl LG. 1975. Presence of cytochrome and menaquinone in Clostridium formicoaceticum and Clostridium thermoaceticum. J. Bacteriol. 122:325–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Müller V. 2003. Energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6345–6353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pierce E, Xie G, Barabote RD, Saunders E, Han CS, Detter JC, Richardson P, Brettin TS, Das A, Ljungdahl LG, Ragsdale SW. 2008. The complete genome sequence of Moorella thermoacetica (f. Clostridium thermoaceticum). Environ. Microbiol. 10:2550–2573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thauer RK, Kaster AK, Seedorf H, Buckel W, Hedderich R. 2008. Methanogenic archaea: ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kellum R, Drake HL. 1984. Effects of cultivation gas phase on hydrogenase of the acetogen Clostridium thermoaceticum. J. Bacteriol. 160:466–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martin DR, Lundie LL, Kellum R, Drake HL. 1983. Carbon monoxide-dependent evolution of hydrogen by the homoacetate-fermenting bacterium Clostridium thermoaceticum. Curr. Microbiol. 8:337–340 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Drake HL. 1982. Demonstration of hydrogenase in extracts of the homoacetate-fermenting bacterium Clostridium thermoaceticum. J. Bacteriol. 150:702–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schut GJ, Adams MW. 2009. The iron-hydrogenase of Thermotoga maritima utilizes ferredoxin and NADH synergistically: a new perspective on anaerobic hydrogen production. J. Bacteriol. 191:4451–4457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malki S, Saimmaime I, De Luca G, Rousset M, Dermoun Z, Belaich JP. 1995. Characterization of an operon encoding an NADP-reducing hydrogenase in Desulfovibrio fructosovorans. J. Bacteriol. 177:2628–2636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Verhagen MF, O'Rourke T, Adams MW. 1999. The hyperthermophilic bacterium, Thermotoga maritima, contains an unusually complex iron-hydrogenase: amino acid sequence analyses versus biochemical characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1412:212–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith ET, Feinberg BA. 1990. Redox properties of several bacterial ferredoxins using square wave voltammetry. J. Biol. Chem. 265:14371–14376 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Buckel W, Thauer RK. 16 July 2012. Energy conservation via electron bifurcating ferredoxin reduction and proton/Na+ translocating ferredoxin oxidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Herrmann G, Jayamani E, Mai G, Buckel W. 2008. Energy conservation via electron-transferring flavoprotein in anaerobic bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 190:784–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li F, Hinderberger J, Seedorf H, Zhang J, Buckel W, Thauer RK. 2008. Coupled ferredoxin and crotonyl coenzyme A (CoA) reduction with NADH catalyzed by the butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase/Etf complex from Clostridium kluyveri. J. Bacteriol. 190:843–850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaster AK, Moll J, Parey K, Thauer RK. 2011. Coupling of ferredoxin and heterodisulfide reduction via electron bifurcation in hydrogenotrophic methanogenic archaea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:2981–2986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang S, Huang H, Moll J, Thauer RK. 2010. NADP+ reduction with reduced ferredoxin and NADP+ reduction with NADH are coupled via an electron-bifurcating enzyme complex in Clostridium kluyveri. J. Bacteriol. 192:5115–5123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jungermann K, Thauer RK, Leimenstoll G, Decker K. 1973. Function of reduced pyridine nucleotide-ferredoxin oxidoreductases in saccharolytic clostridia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 305:268–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wahl RC, Orme-Johnson WH. 1987. Clostridial pyruvate oxidoreductase and the pyruvate-oxidizing enzyme specific to nitrogen fixation in Klebsiella pneumoniae are similar enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 262:10489–10496 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schönheit P, Wäscher C, Thauer RK. 1978. Rapid procedure for purification of ferredoxin from clostridia using polyethyleneimine. FEBS Lett. 89:219–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aliverti A, Curti B, Vanoni MA. 1999. Identifying and quantitating FAD and FMN in simple and in iron-sulfur-containing flavoproteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 131:9–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smith ET, Bennett DW, Feinberg BA. 1991. Redox properties of 2[4Fe-4S] ferredoxins. Anal. Chim. Acta 251:27–33 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mortenson LE, Valentine RC, Carnahan JE. 1962. An electron transport factor from Clostridium pasteurianum. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 7:448–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tagawa K, Arnon DI. 1962. Ferredoxins as electron carriers in photosynthesis and in the biological production and consumption of hydrogen gas. Nature 195:537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bisswanger H. 2008. Enzyme kinetics: principles and methods, 2nd ed. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co KGaA, Weinheim, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bender G, Ragsdale SW. 2011. Evidence that ferredoxin interfaces with an internal redox shuttle in acetyl-CoA synthase during reductive activation and catalysis. Biochemistry 50:276–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ragsdale SW, Wood HG. 1985. Acetate biosynthesis by acetogenic bacteria. Evidence that carbon monoxide dehydrogenase is the condensing enzyme that catalyzes the final steps of the synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 260:3970–3977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Booth IR, Krulwich TA, Padan E, Stock JB, Cook GM, Skulachev V, Bennett GN, Epstein W, Slonczewski JL, Rowbury RJ, Matin A, Foster JW, Poole RK, Konings WN, Schafer G, Dimroth P. 1999. The regulation of intracellular pH in bacteria. Novartis Found. Symp. 221:19–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cook GM. 2000. The intracellular pH of the thermophilic bacterium Thermoanaerobacter wiegelii during growth and production of fermentation acids. Extremophiles 4:279–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thauer RK. 1972. CO2-reduction to formate by NADPH. The initial step in the total synthesis of acetate from CO2 in Clostridium thermoaceticum. FEBS Lett. 27:111–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Furdui C, Ragsdale SW. 2002. The roles of coenzyme A in the pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase reaction mechanism: rate enhancement of electron transfer from a radical intermediate to an iron-sulfur cluster. Biochemistry 41:9921–9937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thauer RK, Kaster AK, Goenrich M, Schick M, Hiromoto T, Shima S. 2010. Hydrogenases from methanogenic archaea, nickel, a novel cofactor, and H2 storage. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79:507–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Buchenau B. 2001. Are there tetrahydrofolate specific enzymes in methanogenic archaea and tetrahydromethanopterin specific enzymes in acetogenic bacteria? Diplom. thesis. Philipps University, Marburg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tanner RS, Wolfe RS, Ljungdahl LG. 1978. Tetrahydrofolate enzyme levels in Acetobacterium woodii and their implication in the synthesis of acetate from CO2. J. Bacteriol. 134:668–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ljungdahl LG, O'Brien WE, Moore MR, Liu MT. 1980. Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase from Clostridium formicoaceticum and methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase, methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase (combined) from Clostridium thermoaceticum. Methods Enzymol. 66:599–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. O'Brien WE, Brewer JM, Ljungdahl LG. 1973. Purification and characterization of thermostable 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase from Clostridium thermoaceticum. J. Biol. Chem. 248:403–408 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thauer RK, Jungermann K, Decker K. 1977. Energy conservation in chemotrophic anaerobic bacteria. Bacteriol. Rev. 41:100–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wohlfarth G, Diekert G. 1991. Thermodynamics of methylenetetrahydrofolate reduction to methyltetrahydrofolate and its implications for the energy metabolism of homoacetogenic bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 155:378–381 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Holländer R. 1976. Correlation of the function of demethylmenaquinone in bacterial electron transport with its redox potential. FEBS Lett. 72:98–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.