Abstract

A transposon-based, genomewide mutagenesis screen exploiting the killing activity of a lytic ViII bacteriophage was used to identify Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi genes that contribute to Vi polysaccharide capsule expression. Genes enriched in the screen included those within the viaB locus (tviABCDE and vexABCDE) as well as oxyR, barA/sirA, and yrfF, which have not previously been associated with Vi expression. The role of these genes in Vi expression was confirmed by constructing defined null mutant derivatives of S. Typhi, and these were negative for Vi expression as determined by agglutination assays with Vi-specific sera or susceptibility to Vi-targeting bacteriophages. Transcriptome analysis confirmed a reduction in expression from the viaB locus in these S. Typhi mutant derivatives and defined regulatory networks associated with Vi expression.

INTRODUCTION

Bacteria express an array of surface-associated macromolecular structures that facilitate their interaction with the environment (1). In pathogenic bacteria, the expression of such surface components can change rapidly as the infecting bacteria move between and within their hosts (2). Surface molecules on pathogens include proteins, flagella, fimbriae, glycolipids, and polysaccharides that can directly facilitate bacterial survival through processes such as adhesion, nutrient scavenging, and resisting immune attack or bacteriophage killing (3, 4). Thus, the expression of surface structures is a complex process that can involve multiple, coordinately expressed genes associated with biosynthesis and localization.

Bacterial surface antigens play a key role as targets determining the specificity of killing by antibodies or bacteriophages (5, 6). The antigens and macromolecular structures that are targeted by these killing systems include outer membrane proteins, lipopolysaccharides, and carbohydrate capsules (4). We know from in vitro killing assays that otherwise sensitive bacteria can escape killing by either modifying the structure of a target or altering its expression (7). Indeed, it is likely that the immune system and bacteriophages have exerted significant selection on surface antigens such that bacteria have evolved pathways to facilitate escape. Surface antigens are attractive as candidate subunit vaccines or as targets for therapeutic bacteriophages. In this context, it is important to determine how bacteria escape killing as a means to predict how such escape variants might emerge in control programs, such as rolling out new vaccines or introducing bacteriophage therapies.

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, the etiological agent of typhoid fever, expresses a surface-associated polysaccharide, Vi, that has been implicated in virulence (8–10). Many key genes associated with biosynthesis of Vi, which is a homopolymer of variably O-acetylated α-1,4-linked N-acetylgalactosaminuronate moieties (11), are carried in the viaB locus (tviABCDE and vexABCDE genes). Importantly, Vi is a protective antigen on which some human typhoid vaccines are based (9, 12). Vi was also targeted previously in bacteriophage therapy clinical studies using Vi-specific bacteriophages (13). We previously characterized a related set of Vi-specific bacteriophages that has found general utility for typing S. Typhi clinical isolates (5). Although these bacteriophages are genetically diverse, they all encode tail fiber components that specifically target Vi to initiate infection. For this study, we used one of these Vi phages, ViII, to drive selection in a whole-genome mutagenesis screen based on a technique we named TraDIS (14) to identify genes that, when inactivated by a transposon insertion, decrease ViII-associated killing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, growth conditions, and transposon libraries.

A transposon mutant library based on S. Typhi BRD948(pHCM1) and the transposon EZ-Tn5 was exploited in the selection of Vi-negative mutant derivatives. BRD948(pHCM1) aroA htrA is an attenuated derivative of Ty2 harboring the antibiotic resistance plasmid pHCM1 (14). This so-called TraDIS library, which harbors at least 1.1 million transposon mutants and was described in detail previously (14), was stored at −80°C. S. Typhi bacteria were routinely cultured on LB agar or in LB broth containing aromatic supplements (tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine at a final concentration of 40 μg/ml and 4-aminobenzoic acid and 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml). Antibiotics were added at final concentrations of 50 μg/ml for ampicillin and 30 μg/ml for kanamycin and chloramphenicol. All defined mutant derivatives constructed during this study were derived from S. Typhi BRD948 lacking pHCM1. Specific mutations were generated via the Red recombinase system, originally described by Datsenko and Wanner, using plasmids pKD3 and pKD4 for chloramphenicol and kanamycin selection, respectively (15). The defined S. Typhi BRD948 mutant derivatives generated in this study harbored mutations in yrfF, rcsB, oxyR, sirA, envZ, barA, greA, efp, ihfA, ihfD, actP, ppiB, or phoN. The PCR oligonucleotides used to generate these mutants and determine their genotypes are detailed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Selection of Vi phage-resistant mutants from the S. Typhi(pHCM1) transposon TraDIS library.

A transposon mutant library based on S. Typhi BRD948(pHCM1) was infected with ViII bacteriophage (5, 16) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ∼10, and the infection was allowed to proceed for 20 min at 37°C. One milliliter of LB broth containing 5 mM EGTA was then added to stop further phage infections, and the mix was incubated at 37°C to allow survivors to grow before aliquots were plated out onto L agar plates containing kanamycin at 30 μg/ml. After incubation at 37°C overnight, each plate harbored ∼4,000 colonies. Approximately 100 of these colonies were randomly selected from different plates and tested in slide agglutination assays using anti-Salmonella O-4, O-9, and Vi antisera (Statens Serum Institut, Denmark). Colonies to be tested were prepared by growing the test bacteria overnight at 37°C on L agar plates containing the aromatic nutrients required for growth (17). All tested colonies, but not wild-type BRD948 (which was Vi and O-9 positive), were Vi negative but O-9 positive by agglutination. Subsequently, colonies from five plates (∼20,000 colonies) were collected into diluent and pooled, and DNA was prepared from a 5-ml aliquot by the method of Hull et al. (18). This pooled DNA was then sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq instrument according to the manufacturer's instructions, with modifications as described previously (14). Sequence reads were parsed for an exact match to the terminal 10 bp of the Tn5 transposon (TAAGAGACAG). Matching sequence reads had this sequence removed and were converted to fastq format. The modified fastq reads were mapped to the S. Typhi Ty2 genome by use of MAQ (14). The map position of the first base was used as the precise insertion site of the transposon, and the distribution within genes and number of reads at each position were used to estimate the number of transposon insertions in the input library and the output library after selection. The statistical significance was calculated as previously described (14).

Vi enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Costar 3590 96-well enzyme immunoassay (EIA) plates were treated overnight with 50 μl of monoclonal anti-Vi agglutination serum (Statens Serum Institut) diluted 1 in 100 in 1× coating buffer (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories [KPL]). This was removed the following day, and the plates were washed three times with KPL wash buffer and blotted dry. One hundred microliters of KPL blocking buffer was added to each well and left at 37°C for 2 h prior to three more washes with 1× wash buffer and dry blotting. Bacterial cultures for testing were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.55, using formalized phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Three hundred microliters of this bacterial suspension was added to the first well of a further microtiter plate and doubly diluted across the plate, using 150 μl of KPL blocking buffer as diluent. Fifty-microliter aliquots of the S. Typhi dilutions were transferred to the washed and blocked plates and were left on these anti-Vi antibody-coated plates for 2 h at 37°C.

Plates were washed three times to remove the bacterial suspension, and 50 μl of a 1-in-100 dilution of rabbit polyclonal anti-Vi serum (Remel ZC18) in 1× KPL blocking buffer was added to each well and left for 2 h at 37°C. The plate was then washed three times, and 50 μl anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (diluted 1 in 1,000 in 1× blocking buffer) was added to each well and left for a further 2 h at 37°C. Finally, the wells were washed three times, the wells dried, and 50 μl of KPL Sure Blue tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) solution added. When sufficient blue color had developed, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 μl 1 M HCl to each well. The plates were read at 450 nm on a Bio-Rad microplate spectrophotometer.

Testing of S. Typhi mutant derivatives for Vi expression and Vi phage sensitivity.

S. Typhi BRD948 and selected mutant derivatives were tested for sensitivity to a range of Vi phages, including ViI, ViII, ViIII, ViIV, ViV, and ViVI bacteriophages (5, 16). Each mutant was grown in 3 ml of L broth left shaking overnight at 37°C. Molten 0.35% L agar was cooled to 42°C, and 3 ml was added to a Falcon tube containing 100 μl of a culture of wild-type S. Typhi BRD948 or a mutant derivative; this mix was poured immediately onto L agar plates containing kanamycin. Ten microliters of each phage preparation was spotted onto solidified top agar, and the plates were left overnight at 37°C. The next day, any phage killing activity was recorded and compared to that in an S. Typhi BRD948 control infection.

RNA transcriptome analysis.

L broth cultures of S. Typhi BRD948 or mutant derivatives were grown to an OD600 of 0.3 and mixed with RNA Protect (Qiagen) for 30 min at room temperature, the inactivated bacteria were harvested, and the pellet was stored at −80°C. RNAs were isolated from these pellets by use of Qiagen kits, and total RNA was prepared using Qiagen RNeasy miniprep columns followed by DNase treatment and phenol-chloroform extraction. Ethanol was then used to precipitate the RNA, and the RNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, followed by drying. The pellets were resuspended in 50 μl of ultrapure water, and 1-μl aliquots were checked for RNA quality and quantity by the Agilent Technologies RNA 6000 Nano assay protocol, using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. A custom-made oligonucleotide array (Agilent) representative of genes annotated for S. Typhi Ty2 was used for microarray analysis. The design of the oligonucleotide array is available from Agilent database submissions (ID 25337671). Fifty nanograms of total RNA for each sample was amplified and labeled with Cy3-CTP following the manufacturer's protocol (Agilent Low Input Quick Amp WT labeling kit, one-color). Labeling efficiency was assessed using a Nanodrop-8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Cy3-labeled cRNA was hybridized to Agilent custom 8,000-by-15,000 S. Typhimurium and S. Typhi microarrays for 17 h at 65°C. After hybridization, the microarray slides were washed and scanned using an Agilent DNA High Resolution microarray scanner following the manufacturer's protocol. Raw image data were processed using Agilent's Feature Extraction (AFE) software (v10.7.3.1).

Data from the Agilent array were analyzed using Agilent Feature Extraction software (v10.1). Array features were calculated using AFE default settings for the GE2-v5_10_Apr08 protocol. The analysis was performed using scripts written in the R language (version 2.11.1 [31 May 2010]), with the aid of a target file and an annotation file to complement the information generated in the output. Using an application available from Bioconductor's LIMMA library (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html), a linear model fit was applied to the data that were generated. Differentially expressed genes were tabulated for each contrast, using the method of Benjamini and Hochberg to correct the P values (14). File data were sorted by significance (adjusted P value [adj.P.Val] column). The adj.P.Val cutoff used in the microarrays identified significant genes whose P value was ≤0.02. A positive log fold change (log FC) value indicates greater expression of the gene in the mutant. One output file per contrast was given, with unfiltered data that included all probes on the array. This file was then used for downstream analysis.

RESULTS

Exploitation of TraDIS to identify transposon insertion mutant derivatives with reduced sensitivity to ViII bacteriophage-mediated killing.

We hypothesized that Vi expression at the surface of S. Typhi involves multiple genes, including some that had not previously been identified. To test this hypothesis, we used a sequencing-based screen, known as TraDIS (14), that exploits large transposon libraries. A complex transposon library generated from Vi-positive S. Typhi BRD948(pHCM1) and harboring over 106 transposon mutants was infected with the Vi-specific lytic bacteriophage ViII in order to enrich for Vi-negative survivors. The insertion sites for all the transposons in the input and surviving pools were determined by Illumina sequencing from a primer specific for sequences at the end of the transposon, using DNAs from both the input and surviving pools as templates (14). We then compared the distribution of insertion sites in the input transposon library with that in the recovered S. Typhi strains following selection (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of genes with statistically significant transposon insertions recovered from the S. Typhi TraDIS library pool after infection by ViII bacteriophagea

| Sys ID | Gene name | No. of insertions |

No. of reads |

Log2 read ratio | P value | Function | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Output | Input | Output | |||||

| t4352 | tviB | 307 | 285 | 11,914 | 1,646,207 | −7.10 | 3.33E−51 | Vi polysaccharide biosynthesis, UDP-glucose/GDP-mannose dehydrogenase |

| t4349 | tviE | 280 | 209 | 4,659 | 592,697 | −6.96 | 1.28E−49 | Vi polysaccharide biosynthesis, TviE |

| t4353 | tviA | 89 | 78 | 1,721 | 184,485 | −6.66 | 2.79E−46 | Vi polysaccharide biosynthesis regulator |

| t4350 | tviD | 627 | 540 | 22,768 | 1,870,584 | −6.35 | 6.18E−43 | Vi polysaccharide biosynthesis |

| t4011 | yrfF | 190 | 112 | 1,263 | 94,290 | −6.11 | 1.99E−40 | Putative membrane protein |

| t4344 | vexE | 141 | 81 | 3,246 | 219,685 | −6.04 | 1.20E−39 | Vi polysaccharide export protein |

| t4351 | tviC | 224 | 164 | 5,856 | 332,427 | −5.80 | 2.68E−37 | Vi polysaccharide biosynthesis protein, epimerase |

| t4347 | vexB | 168 | 131 | 5,269 | 286,393 | −5.74 | 1.17E−36 | Vi polysaccharide export inner membrane protein |

| t4345 | vexD | 218 | 159 | 6,661 | 325,843 | −5.59 | 3.05E−35 | Vi polysaccharide export inner membrane protein |

| t4348 | vexA | 206 | 164 | 9,690 | 470,499 | −5.59 | 3.34E−35 | Vi polysaccharide export protein |

| t4179 | actP | 94 | 5 | 1,216 | 49,412 | −5.23 | 6.59E−32 | Sodium-solute symporter family protein |

| t4346 | vexC | 177 | 142 | 18,227 | 620,241 | −5.08 | 1.54E−30 | Vi polysaccharide export ATP-binding protein |

| t4225 | phoN | 208 | 3 | 5,341 | 87,540 | −4.01 | 8.23E−22 | Nonspecific acid phosphatase precursor |

| t4209 | dcuB | 71 | 5 | 2,371 | 39,400 | −4.00 | 9.93E−22 | Anaerobic C4-dicarboxylate transporter |

| t1220 | ihfA | 8 | 2 | 60 | 2,186 | −3.84 | 1.51E−20 | Integration host factor alpha subunit |

| t4362 | 246 | 2 | 4,107 | 55,798 | −3.73 | 8.40E−20 | Putative membrane protein | |

| t4004 | ompR | 47 | 16 | 272 | 4,392 | −3.59 | 7.64E−19 | Two-component response regulator OmpR |

| t4356 | 271 | 7 | 5,186 | 60,540 | −3.52 | 2.44E−18 | Hypothetical protein | |

| t4268 | 169 | 4 | 2,629 | 30,184 | −3.47 | 5.12E−18 | Putative exported protein | |

| t3216 | greA | 32 | 16 | 527 | 5,488 | −3.16 | 5.74E−16 | Transcription elongation factor |

| t0012 | dnaK | 5 | 3 | 14 | 862 | −3.08 | 1.77E−15 | DnaK protein |

| t4005 | envZ | 77 | 35 | 602 | 3,708 | −2.44 | 7.98E−12 | Two-component sensor kinase EnvZ |

| t4386 | efp | 51 | 17 | 300 | 1,689 | −2.16 | 2.12E−10 | Elongation factor P |

| t2867 | barA | 140 | 65 | 1,780 | 8,225 | −2.15 | 2.50E−10 | Sensor protein |

| t3205 | nusA | 18 | 5 | 108 | 743 | −2.02 | 1.03E−09 | L factor |

| t4313 | 27 | 1 | 220 | 968 | −1.74 | 1.95E−08 | Putative membrane protein | |

| t0929 | sirA | 36 | 18 | 263 | 964 | −1.55 | 1.22E−07 | Invasion response regulator |

| t3500 | oxyR | 66 | 30 | 717 | 1,853 | −1.26 | 1.73E−06 | Hydrogen peroxide-inducible regulon activator |

| t3474 | rpoB | 5 | 1 | 9 | 159 | −1.25 | 1.87E−06 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase, beta subunit |

| t1627 | topA | 66 | 12 | 280 | 591 | −0.86 | 4.06E−05 | DNA topoisomerase I, omega protein I |

| t2325 | ppiB | 8 | 3 | 50 | 153 | −0.75 | 8.91E−05 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase B |

| t3095 | parC | 1 | 1 | 12 | 83 | −0.71 | 1.23E−04 | Topoisomerase IV subunit A |

| t1238 | 78 | 2 | 788 | 1,284 | −0.64 | 1.96E−04 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| t0013 | dnaJ | 38 | 12 | 234 | 419 | −0.64 | 2.01E−04 | DnaJ protein |

| t0595 | rcsB | 28 | 6 | 180 | 318 | −0.58 | 2.96E−04 | Regulator of capsule synthesis B component |

| t1952 | ihfB | 16 | 2 | 102 | 183 | −0.49 | 5.32E−04 | Integration host factor beta subunit |

| t4219 | 46 | 2 | 2,902 | 4,090 | −0.48 | 5.51E−04 | Hypothetical protein | |

“Sys ID” refers to the gene number in the sequenced S. Typhi Ty2 genome (GenBank accession number NC_004631). Gene names and functions were taken from this annotation. “Input” refers to the S. Typhi TraDIS pool at time zero (just before phage addition), while “output” refers to the recovered pool after treatment with S. Typhi ViII phage. The data were analyzed to identify those genes that were statistically overrepresented in the output pool (log2 read ratio and P value).

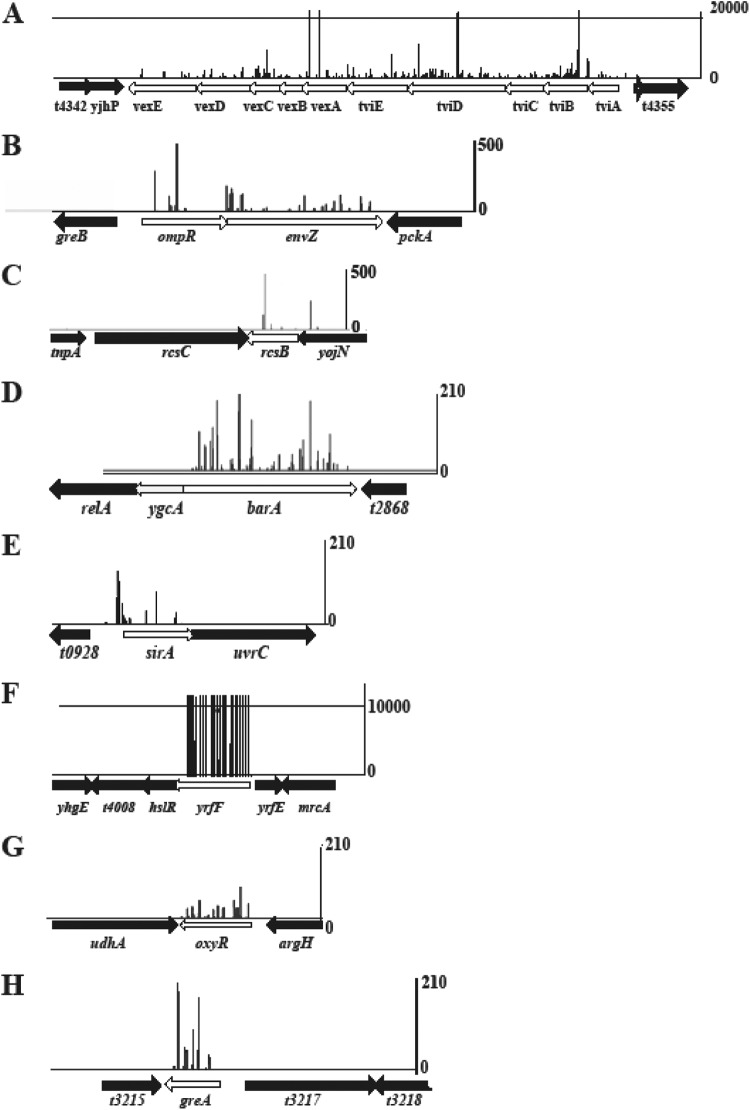

Initial analysis of the output library generated following exposure to ViII phage identified a limited number of genes with significant numbers of transposon insertions (Table 1). This indicated that relatively few nonessential genes in the genome were required for productive Vi phage propagation and suggested that phage killing did indeed act as a strong selection force. Importantly, insertion sites within genes of the viaB locus (tviABCDE and vexABCDE), which are directly involved in Vi biosynthesis and secretion (19), were highly represented in the sequences of the output library. These included a gene encoding a positive regulator of viaB locus expression (tviA), biosynthesis genes (tviB to tviE), and transport genes (vexA-vexE). Figure 1A illustrates the extensive insertions that mapped within the viaB locus, using DNA from bacteria recovered after ViII phage infection. It is noteworthy that genes adjacent to the viaB locus were virtually free of transposon insertions. Selection of a dense set of transposon insertion mutants within the viaB locus provided evidence that the method employed to recover mutants that survived ViII phage challenge and the subsequent mapping of the insertions themselves were successful.

Fig 1.

Mapping of transposon insertion reads within the mutants studied in detail. (A) Insertions in the viaB locus; (B) insertions in ompR and envZ; (C) insertions in rcsB; (D) insertions in barA; (E) insertions in sirA; (F) insertions in yrfF (igaA); (G) insertions in oxyR; (H) insertions in greA. The scale on the right indicates the number of reads for any insertion point shown. For some insertion points in the viaB locus, this exceeded 20,000 reads, while for ompR the maximum was approximately 500 reads at one insertion point for the transposon. Mapping of the insertion points to the sequence was done using the ARTEMIS program.

In total, 37 genes had significantly more transposon insertions than would be expected, several of which, such as ompR and envZ (20–22) or rcsB and rcsC (23, 24), were previously known to play a role in regulating Vi expression (25, 26). In addition, a number of other novel genes not previously linked to Vi expression were identified in the screen (Fig. 1B to E). Transposon insertions were overrepresented in the barA/sirA genes, encoding a two-component regulatory system (Fig. 1D and E). SirA is the cognate response regulator for the sensor kinase BarA (6). Unlike ompR and envZ, barA and sirA are located in different regions of the genome in S. Typhi. The yrfF gene, also previously annotated as igaA, was one of the most highly represented genes in terms of the density of transposon insertions (27) (Fig. 1F). In S. Typhimurium, YrfF has been described previously as an attenuator, acting via repression of RcsB and RcsC (27, 28). Mutations in yrfF are lethal in isolates of S. Typhimurium (29), but we did not find this to be the case in S. Typhi BRD948. The oxyR gene, which encodes a LysR family member, was also identified in the screen (30, 31), as were the transcription elongation factor-encoding gene greA (32, 33) and the elongation factor P-encoding gene efp (34).

Construction of defined S. Typhi BRD948 mutant derivatives.

A number of the genes with significant overrepresentation of transposon insertion mutations in the TraDIS screen were selected for further analysis by construction of defined deletion mutations in S. Typhi BRD948 (see Materials and Methods). We were unable to generate null deletion mutations in several genes, including dnaK and parC, and these were not analyzed further. S. Typhi BRD948 mutant derivatives were first tested for the ability to agglutinate Vi antisera (Table 2). The S. Typhi BRD948 derivatives harboring mutations in ihfA, ihfD, actP, ppiB, efp, greA, and phoN exhibited small or intermediate reductions in agglutination with anti-Vi antisera but were still deemed to be positive. BRD948 derivatives harboring all other mutations listed in Table 2 were not obviously reproducibly agglutinated with anti-Vi antiserum, but these were well agglutinated with anti-O9.

Table 2.

Summary of Vi expression levels in S. Typhi BRD948 and various mutant derivativesa

| Strain | Slide agglutination profile | Response to Vi bacteriophage |

Vi ELISA titer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Type II | Type IV | Types VI and VII | |||

| yrlF mutant | O9, +++; Vi, − | − | − | − | − | <2 |

| rcsB mutant | O9, +++; Vi, − | − | − | − | − | <2 |

| oxyR mutant | O9, +++; Vi, − | − | − | − | − | <2 |

| sirA mutant | O9, +++; Vi, +/− | +/− | − | − | +/− | ND |

| envZ mutant | O9, +++; Vi, + | + | + | + | + | 128 |

| barA mutant | O9, +++; Vi, + | + | + | + | + | 256 |

| greA mutant | O9, +++; Vi, ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | 256 |

| efp mutant | O9, +++; Vi, ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | 512 |

| ihfA mutant | O9, +++; Vi, +++ | ++/+++ | ++/+++ | ++/+++ | ++/+++ | 1,024 |

| ppiB mutant | O9, −; Vi, +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ND |

| ihfB mutant | O9, +/−; Vi, +++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | ND |

| actP mutant | O9, −; Vi, +++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ND |

| phoN mutant | O9, −; Vi, +++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ND |

| BRD948 | O9, −; Vi, +++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | >2,048 |

++++ indicates a response equivalent to that of wild-type S. Typhi BRD948. The number of + symbols indicates the relative strength of the response. −, no response; ND, not determined.

The mutant derivatives of BRD948 were next tested for the ability to be infected by the broader Vi phage types ViI (a Myoviridae virus), ViII (a Siphoviridae virus), and ViIII to ViVII (Podoviridae viruses). As expected, S. Typhi BRD948 derivatives that were agglutinated with anti-Vi antisera, such as efp, ihfA, and greA mutants, were also susceptible to lysis by other Vi-specific phages (Table 2). S. Typhi BRD948 derivatives harboring mutations in envZ, rcsB, yrfF, barA, sirA, and oxyR were significantly impaired in the ability to support Vi phage propagation, irrespective of the phage type.

RNA transcriptome analysis.

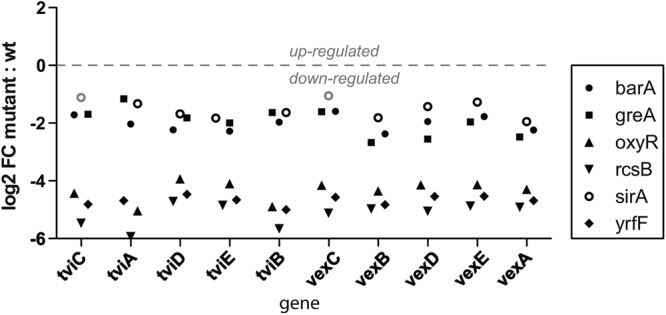

A number of the genes identified in the screen that are located outside the viaB locus encode known or candidate transcriptional regulators and/or cognate environmental sensors. Consequently, we performed microarray-based transcriptomic analysis on independent S. Typhi BRD948 derivatives harboring mutations in these genes to define regulatory networks linked to Vi expression. As expected, the viaB locus itself was expressed at a lower level by all of these mutant derivatives (Fig. 2). The S. Typhi BRD948 derivatives harboring mutations in rcsB, oxyR, or yrfF exhibited profound decreases in expression across the viaB locus, with a decrease of over 4 log compared to wild-type S. Typhi BRD948. S. Typhi BRD948 derivatives harboring mutations in barA, sirA, or greA had smaller but significant decreases in viaB expression.

Fig 2.

Gene expression levels within the viaB locus in S. Typhi barA, greA, oxyR, rcsB, sirA, and yrfF mutant strains, based upon RNA transcription microarrays. Note the significant difference between the barA, greA, and sirA mutants in one grouping and the rcsB, yrfF, and oxyR mutants in another. wt, wild type.

The number of genes that were up- or downregulated in comparison to those in wild-type S. Typhi BRD948 ranged from 80 to over 200 genes in each of the mutant derivatives (see Tables S2a to f in the supplemental material). In addition to viaB, a number of other gene categories appeared in more than one of the dysregulated gene lists. Flagellum biosynthesis genes exhibited altered expression in several of the S. Typhi BRD948 mutant derivatives, including the rcsB, barA, oxyR, and yrfF mutants. A number of genes involved in sugar metabolism or transport, including that of ribose, exhibited altered expression, for example, in the barA, sirA, and oxyR S. Typhi BRD948 mutant derivatives. A number of virulence-associated genes and several type III secretion effector genes were linked to viaB expression, including the srfABC cluster, sopE (rcsB and barA), and prgH1 (sirA and oxyR). A number of other regulator genes were also linked through these networks, most notably in the barA mutant (see Table S2a in the supplemental material).

DISCUSSION

Here we describe the use of a high-throughput, sequence-based mutagenesis screen (TraDIS) to identify genes that are required for efficient Vi expression in S. Typhi. ViII phage-mediated selection of an S. Typhi transposon insertion library containing over one million independent insertions yielded different classes of Vi phage-resistant mutant derivatives. Insertion mutations in genes previously known to be involved in Vi expression were enriched, along with insertions in several genes not previously linked to Vi expression. In our screen, each of the genes within the viaB locus was identified, with a very broad representation of insertion sites following selection (Table 1; Fig. 1). Other key known Vi-regulatory genes, such as ompR, were also identified, along with the regulatory gene rcsB.

It was shown previously that the viaB locus is differentially regulated compared to the genes for flagellin and Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) proteins such as SipB and SipC via RcsB, with a role for the viaB regulatory protein TviA (26, 35). Here we also identified several regulatory genes that have not previously been associated with Vi expression. Of particular interest was the yrfF gene, which according to the pfam database likely encodes a member of an integral inner membrane protein family (36). This protein is predicted to harbor five transmembrane helices distributed along the protein sequence and linked by four soluble loops that could mediate protein-protein interactions via an ankyrin-type motif. Interestingly, yrfF is also known as an “intracellular growth attenuator” (igaA), in recognition of a role in regulating bacterial growth inside fibroblasts. yrfF can interact with the rcsBCD regulatory system in other enteric bacteria (27, 36, 37). We were able to introduce a large deletion into the yrfF gene of S. Typhi BRD948, indicating that the phenotype of a yrfF/igaA mutant of S. Typhi differs from that for S. Typhimurium, since mutation of this gene is lethal in isolates of the latter (29). Significantly, Escherichia coli strains harboring mutations in yrfF/igaA are also viable (38). In S. Typhimurium, compensatory deletions in the rcsBCD cluster are required to enable a yrfF mutant to retain viability (37).

Mutations in the regulatory genes barA and sirA also affected the expression of the viaB locus in our screen and follow-up analysis. barA and sirA are linked functionally as a two-component regulatory system, even though the genes are located at different genomic positions on the S. Typhi chromosome. The microarray data showed a decrease in viaB locus gene expression of 1 or 2 log, and a reduced but detectable level of Vi polysaccharide expression was detected using an anti-Vi antibody with ELISA. The environmental signals recognized by the barA/sirA system have not been defined fully but are known to include osmolarity (39). BarA and SirA have previously been demonstrated to have a regulatory role in SPI-1 gene expression (39), and we now report another virulence locus, the viaB locus, as part of this regulon (26).

The LysR family transcriptional regulator OxyR activates gene expression in response to oxidative stress. OxyR plays a role in influencing bacteriophage susceptibility in S. Typhimurium, through mechanisms involving phase variation in genes associated with lipopolysaccharide synthesis (40). Linking Vi expression to the OxyR regulon may have significance for our understanding of the mechanisms of gene regulation exploited by S. Typhi as it moves through the tissues of the host during infection or establishes a carrier state in organs such as the gallbladder. Interestingly, S. Typhi BRD948 still expresses agglutinable Vi under anaerobic conditions, suggesting that other environmental cues may play a role in the oxyR-mediated regulation of Vi (our unpublished results). More work will be required to reveal the complexity of the link between BarA-SirA, YrfF, OxyR, and RcsA-RcsB and Vi expression. This intricate system mirrors observations made concerning the regulation of SPI-1, a further horizontally acquired gene locus that is also regulated by SirA and OmpR (2, 41).

Previous studies have shown that the viaB locus is carried on a potentially mobile element known as Salmonella pathogenicity island 7 (SPI-7) within S. Typhi, S. Paratyphi C, and individual isolates of S. Dublin (42). It is intriguing that this genetic system, carried on horizontally acquired DNA, has integrated into ancestral regulatory networks in S. Typhi. It is perhaps significant that many of the transposon insertions affecting Vi expression outside viaB were in regulatory genes. Clearly, Vi expression is modulated in a complex but highly integrated way in S. Typhi. The Vi antigen itself is a key component of human typhoid vaccines, so it will be critical to monitor sites of typhoid endemicity where such vaccines are introduced for any escape mutants (9, 43). Vi is known to potentiate the virulence of S. Typhi but is not essential for infection (44). Furthermore, Vi-negative S. Typhi isolates have been reported from clinical typhoid cases in some parts of the world (43). Finally, we believe that this high-throughput and high-density genetic screen could have value for mapping similar genetic networks involved in the expression of surface components on other bacteria. Such screens could find particular utility in antibody killing assays employed in pre- or postclinical testing of vaccines in which bacterial surface antigens are essential components. Such assays could have value for identifying potential genetic escape routes from vaccination.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust through grant 098051.

We thank Ruben Bautista and Chris McGee for excellent professional help and expertise in conducting the RNA microarray runs and analysis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 January 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01632-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sonnenburg JL, Xu J, Leip DD, Chen CH, Westover BP, Weatherford J, Buhler JD, Gordon JI. 2005. Glycan foraging in vivo by an intestine-adapted bacterial symbiont. Science 307:1955–1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Teplitski M, Goodier RI, Ahmer BM. 2003. Pathways leading from BarA/SirA to motility and virulence gene expression in Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 185:7257–7265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Labrie SJ, Samson JE, Moineau S. 2010. Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat. Rev. 8:317–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leid JG, Willson CJ, Shirtliff ME, Hassett DJ, Parsek MR, Jeffers AK. 2005. The exopolysaccharide alginate protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm bacteria from IFN-gamma-mediated macrophage killing. J. Immunol. 175:7512–7518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pickard D, Toribio AL, Petty NK, van Tonder A, Yu L, Goulding D, Barrell B, Rance R, Harris D, Wetter M, Wain J, Choudhary J, Thomson N, Dougan G. 2010. A conserved acetyl esterase domain targets diverse bacteriophages to the Vi capsular receptor of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. J. Bacteriol. 192:5746–5754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Altier C, Suyemoto M, Ruiz AI, Burnham KD, Maurer R. 2000. Characterization of two novel regulatory genes affecting Salmonella invasion gene expression. Mol. Microbiol. 35:635–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Finlay BB, McFadden G. 2006. Anti-immunology: evasion of the host immune system by bacterial and viral pathogens. Cell 124:767–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Looney RJ, Steigbigel RT. 1986. Role of the Vi antigen of Salmonella typhi in resistance to host defense in vitro. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 108:506–516 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arya SC. 1997. Typhim ViTM vaccine and infection by Vi-negative strains of Salmonella typhi. J. Travel Med. 4:207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Robbins JD, Robbins JB. 1984. Reexamination of the protective role of the capsular polysaccharide (Vi antigen) of Salmonella typhi. J. Infect. Dis. 150:436–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Szu SC, Bystricky S. 2003. Physical, chemical, antigenic, and immunologic characterization of polygalacturonan, its derivatives, and Vi antigen from Salmonella typhi. Methods Enzymol. 363:552–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Engels EA, Falagas ME, Lau J, Bennish ML. 1998. Typhoid fever vaccines: a meta-analysis of studies on efficacy and toxicity. BMJ 316:110–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Desranleau JM. 1949. Progress in the treatment of typhoid fever with Vi bacteriophages. Can. J. Public Health 40:473–478 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Langridge GC, Phan MD, Turner DJ, Perkins TT, Parts L, Haase J, Charles I, Maskell DJ, Peters SE, Dougan G, Wain J, Parkhill J, Turner AK. 2009. Simultaneous assay of every Salmonella Typhi gene using one million transposon mutants. Genome Res. 19:2308–2316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Craigie J, Yen CH. 1937. V bacteriophages for B. typhosus. Trans. R. Soc. Can. 5:79–87 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pickard D, Thomson NR, Baker S, Wain J, Pardo M, Goulding D, Hamlin N, Choudhary J, Threfall J, Dougan G. 2008. Molecular characterization of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi Vi-typing bacteriophage E1. J. Bacteriol. 190:2580–2587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hull RA, Gill RE, Hsu P, Minshew BH, Falkow S. 1981. Construction and expression of recombinant plasmids encoding type 1 or d-mannose-resistant pili from a urinary tract infection Escherichia coli isolate. Infect. Immun. 33:933–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hashimoto Y, Li N, Yokoyama H, Ezaki T. 1993. Complete nucleotide sequence and molecular characterization of ViaB region encoding Vi antigen in Salmonella typhi. J. Bacteriol. 175:4456–4465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Comeau DE, Ikenaka K, Tsung KL, Inouye M. 1985. Primary characterization of the protein products of the Escherichia coli ompB locus: structure and regulation of synthesis of the OmpR and EnvZ proteins. J. Bacteriol. 164:578–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Forst S, Comeau D, Norioka S, Inouye M. 1987. Localization and membrane topology of EnvZ, a protein involved in osmoregulation of OmpF and OmpC in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 262:16433–16438 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ikenaka K, Tsung K, Comeau DE, Inouye M. 1988. A dominant mutation in Escherichia coli OmpR lies within a domain which is highly conserved in a large family of bacterial regulatory proteins. Mol. Gen. Genet. 211:538–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hagiwara D, Sugiura M, Oshima T, Mori H, Aiba H, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. 2003. Genome-wide analyses revealing a signaling network of the RcsC-YojN-RcsB phosphorelay system in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:5735–5746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stout V, Gottesman S. 1990. RcsB and RcsC: a two-component regulator of capsule synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 172:659–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pickard D, Li J, Roberts M, Maskell D, Hone D, Levine M, Dougan G, Chatfield S. 1994. Characterization of defined ompR mutants of Salmonella typhi: ompR is involved in the regulation of Vi polysaccharide expression. Infect. Immun. 62:3984–3993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arricau N, Hermant D, Waxin H, Ecobichon C, Duffey PS, Popoff MY. 1998. The RcsB-RcsC regulatory system of Salmonella typhi differentially modulates the expression of invasion proteins, flagellin and Vi antigen in response to osmolarity. Mol. Microbiol. 29:835–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mariscotti JF, Garcia-del Portillo F. 2009. Genome expression analyses revealing the modulation of the Salmonella Rcs regulon by the attenuator IgaA. J. Bacteriol. 191:1855–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dominguez-Bernal G, Pucciarelli MG, Ramos-Morales F, Garcia-Quintanilla M, Cano DA, Casadesus J, Garcia-del Portillo F. 2004. Repression of the RcsC-YojN-RcsB phosphorelay by the IgaA protein is a requisite for Salmonella virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1437–1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cano DA, Dominguez-Bernal G, Tierrez A, Garcia-Del Portillo F, Casadesus J. 2002. Regulation of capsule synthesis and cell motility in Salmonella enterica by the essential gene igaA. Genetics 162:1513–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tartaglia LA, Storz G, Ames BN. 1989. Identification and molecular analysis of oxyR-regulated promoters important for the bacterial adaptation to oxidative stress. J. Mol. Biol. 210:709–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Christman MF, Storz G, Ames BN. 1989. OxyR, a positive regulator of hydrogen peroxide-inducible genes in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, is homologous to a family of bacterial regulatory proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:3484–3488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Borukhov S, Polyakov A, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A. 1992. GreA protein: a transcription elongation factor from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:8899–8902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Borukhov S, Lee J, Laptenko O. 2005. Bacterial transcription elongation factors: new insights into molecular mechanism of action. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1315–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zou SB, Hersch SJ, Roy H, Wiggers JB, Leung AS, Buranyi S, Xie JL, Dare K, Ibba M, Navarre WW. 2012. Loss of elongation factor P disrupts bacterial outer membrane integrity. J. Bacteriol. 194:413–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Winter SE, Winter MG, Thiennimitr P, Gerriets VA, Nuccio SP, Russmann H, Baumler AJ. 2009. The TviA auxiliary protein renders the Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi RcsB regulon responsive to changes in osmolarity. Mol. Microbiol. 74:175–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bateman A, Coin L, Durbin R, Finn RD, Hollich V, Griffiths-Jones S, Khanna A, Marshall M, Moxon S, Sonnhammer EL, Studholme DJ, Yeats C, Eddy SR. 2004. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:D138–D141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mariscotti JF, Garcia-Del Portillo F. 2008. Instability of the Salmonella RcsCDB signalling system in the absence of the attenuator IgaA. Microbiology 154:1372–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meberg BM, Sailer FC, Nelson DE, Young KD. 2001. Reconstruction of Escherichia coli mrcA (PBP 1a) mutants lacking multiple combinations of penicillin binding proteins. J. Bacteriol. 183:6148–6149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mizusaki H, Takaya A, Yamamoto T, Aizawa S. 2008. Signal pathway in salt-activated expression of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 type III secretion system in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 190:4624–4631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cota I, Blanc-Potard AB, Casadesus J. 2012. STM2209-STM2208 (opvAB): a phase variation locus of Salmonella enterica involved in control of O-antigen chain length. PLoS One 7:e36863 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cameron AD, Dorman CJ. 2012. A fundamental regulatory mechanism operating through OmpR and DNA topology controls expression of Salmonella pathogenicity islands SPI-1 and SPI-2. PLoS Genet. 8:e1002615 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pickard D, Wain J, Baker S, Line A, Chohan S, Fookes M, Barron A, Gaora PO, Chabalgoity JA, Thanky N, Scholes C, Thomson N, Quail M, Parkhill J, Dougan G. 2003. Composition, acquisition, and distribution of the Vi exopolysaccharide-encoding Salmonella enterica pathogenicity island SPI-7. J. Bacteriol. 185:5055–5065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mehta G, Arya SC. 2002. Capsular Vi polysaccharide antigen in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1127–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Saha MR, Ramamurthy T, Dutta P, Mitra U. 2000. Emergence of Salmonella typhi Vi antigen-negative strains in an epidemic of multidrug-resistant typhoid fever cases in Calcutta, India. Natl. Med. J. India 13:164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.