Abstract

Rapid identification of microorganisms causing bloodstream infections directly from a positive blood culture would decrease the time to directed antimicrobial therapy and greatly improve patient care. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) is a fast and reliable method for identifying microorganisms from positive culture. This study evaluates the performance of a novel filtration-based method for processing positive-blood-culture broth for immediate identification of microorganisms by MALDI-TOF with a Vitek MS research-use-only system (VMS). BacT/Alert non-charcoal-based blood culture bottles that were flagged positive by the BacT/Alert 3D system were included. An aliquot of positive-blood-culture broth was incubated with lysis buffer for 2 to 4 min at room temperature, the resulting lysate was filtered through a membrane, and harvested microorganisms were identified by VMS. Of the 259 bottles included in the study, VMS identified the organisms in 189 (73%) cultures to the species level and 51 (19.7%) gave no identification (ID), while 6 (2.3%) gave identifications that were considered incorrect. Among 131 monomicrobic isolates from positive-blood-culture bottles with one spot having a score of 99.9%, the IDs for 131 (100%) were correct to the species level. In 202 bottles where VMS was able to generate an ID, the IDs for 189 (93.6%) were correct to the species level, whereas the IDs provided for 7 isolates (3.5%) were incorrect. In conclusion, this method does not require centrifugation and produces a clean spectrum for VMS analysis in less than 15 min. This study demonstrates the effectiveness of the new lysis-filtration method for identifying microorganisms directly from positive-blood-culture bottles in a clinical setting.

INTRODUCTION

Recently, new mass spectrometry (MS) technology has been introduced as a way to quickly and accurately identify bacteria. Compared to standard phenotypic identification, this technology is rapid, requires reagents that are inexpensive (after initial purchase of the instrument), and could provide accurate results comparable to those provided by 16S rRNA sequencing (1). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) MS has been shown to accurately identify bacteria grown on solid medium to the species level (2–4) and has the potential to serve as a fast and reliable method for identifying microorganisms directly from blood.

Rapid identification of organisms causing bloodstream infections after a blood culture turns positive has the potential to improve patient care, and protocols have been developed for use with MALDI-TOF instrumentation. Previously published studies have explored a variety of approaches to accomplish this task, generally using a series of washes, centrifugations, protein extraction, and analysis using dedicated databases (e.g., BioTyper and SARAMIS) (1, 3, 5–11).

The Vitek MS research-use-only (RUO) system (VMS) with the SARAMIS database by bioMérieux (Durham, NC) is a research-use-only MALDI-TOF MS system for rapid detection of bacterial and yeast isolates. This study aimed to evaluate the performance of a novel filtration-based method for processing positive-BacT/Alert-blood-culture broth for immediate organism identification using MALDI-TOF MS. This is the first study using the VMS BacT/Alert bottles and employing a filtration-based method for processing of positive-blood-culture fluid.

(Parts of these results were presented at the 112th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, San Francisco, CA, 16 to 19 June 2012.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All samples included in this study were patient samples collected through routine measures at Grady Memorial Hospital. Blood samples were collected in BacT/Alert anaerobic (SN) and standard aerobic (SA) non-charcoal-based blood culture bottles and were incubated in the BacT/Alert 3D automated microbial detection system (bioMérieux) according to the manufacturer's protocols. All patient blood samples that were collected in these bottles were considered for inclusion; if patients had multiple specimens in appropriate bottle types, they were all included. When a signal-positive bottle was detected, standard biochemical/phenotypic tests for identification routinely used in the Grady Memorial Hospital laboratory were applied, and the results were compared to the identifications (IDs) generated with the VMS. An aliquot of blood culture medium was collected for VMS analysis after processing for routine Gram stain and culture. The lysis and wash buffers used for VMS were provided by bioMérieux.

The majority of the bottles were processed on the day that they flagged positive. However, bottles that could not be processed on the same day were processed within 3 days of flagging positive. Ideally, bottles would be refrigerated until processed, but due to laboratory restrictions, bottles were stored at room temperature until they were processed and run on the VMS. No specific validation of this adjustment to the sample storage guidelines was conducted, outside exercising the normal acceptance criteria for determining the validity of results. Since VMS with SARAMIS is an RUO system, rigid acceptance criteria for results are not set and may be established by the user. For this study, a bottle was considered to have a valid VMS result if at least one spot on the target slide gave a SARAMIS confidence level of ≥75% without conflicting identifications from replicate spots of the same sample. These confidence levels are based on the goodness of fit to weighted consensus reference spectra for a given taxon and are not an indication of confidence intervals in the usual sense. Tests for bottles that did not generate a VMS ID on the first attempt were repeated. When the VMS ID did not match that obtained by conventional or reference methods, e.g., testing with the MicroScan WalkAway (Siemens, Deerfield, IL) or Vitek 2 (bioMérieux) system, the test was repeated both on the VMS and by conventional methods. The VMS instrument was monitored during sample runs to ensure proper machine function, and controls were run before and after each sample run to ensure quality of results. All samples and reagents were brought to room temperature prior to use, and both aerobic and anaerobic bottles were processed identically for VMS analysis.

Sample preparation for MALDI-TOF VMS.

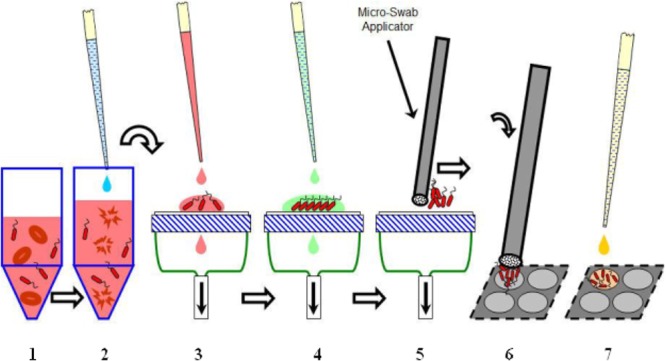

The preparation process (Fig. 1) includes steps that are sensitive to both time and the quantity/quality of the blood culture specimen. To increase the likelihood of satisfactory results, the specified timing restrictions were adhered to, and improper contact with samples was avoided during processing. The detailed protocol is described in the supplemental material.

Fig 1.

Overall summary of sample preparation process. Step 1, collect blood culture broth in a test tube; step 2, incubate blood culture broth with lysis buffer for 2 min; step 3, add lysate to the filter membrane for 40 s, making an effort to keep the lysate within a defined area on the membrane; step 4, wash the filter membrane three times with wash buffer and three times with water; step 5, remove microorganisms from the filter membrane using the microswab applicator; step 6, transfer the microorganisms to the MALDI target plate using the microswab applicator; step 7, add matrix on top of the microorganisms to prepare the slide for spectrum acquisition.

Positive blood bottles were transiently vented and inverted several times. Two milliliters of broth was added to 1.0 ml of lysis buffer (0.6% polyoxyethylene 10 oleoyl ether [Brij 97] in 0.4 M [3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propane sulfonic acid] [CAPS] filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter, pH 11.7), vortexed for 5 s, and allowed to incubate for 2 to 4 min at room temperature. The resulting lysate was passed in a constant stream through a 25-mm 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (catalog no. HPWP02500; Millipore Express PLUS, Billerica, MA), shiny side down, for 40 s. If the liquid backed up, the sample addition was slowed in order to keep the sample application area to roughly 1 cm2.

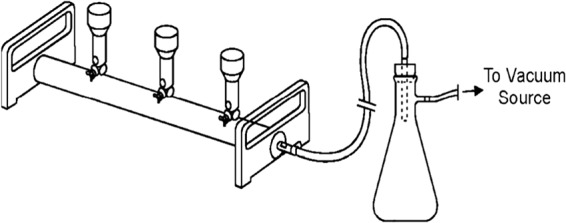

The filter manifold in the laboratory had 3 valves with attached filters, allowing processing of up to 3 samples simultaneously (Fig. 2), resulting in a 15- to 20-min time period between sample removal and placement of the isolates in the VMS machine for identification. When multiple samples were processed together, it was important to stagger the start times for each sample to ensure the proper incubation time with the lysis buffer for each sample. After addition of lysis buffer, the lysate was added at a steady rate that allowed a wet area of 10 to 15 mm to be formed on the membrane without intermediate drying.

Fig 2.

Manifold used for processing of blood culture samples. Three separate valves with attached filters allow simultaneous processing of three samples. The manifold is attached to a vacuum source via a vesicle to store waste and is operated under a biological safety hood.

After the lysate was completely pulled into the filter and no visible liquid remained, the microbial cells remaining on the membrane were washed three times with wash buffer (20 mM Na phosphate, 0.05% Brij 97, and 0.45% NaCl filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter, pH 7.2) and then three times with deionized water. For each wash, enough buffer/water was added to the membrane to completely cover the membrane without flowing over. All liquid was allowed to pass through the membrane so that no visible liquid remained before subsequent washes. Some samples left a visible residue on the filter surface, while others did not. An effort was made to contain the lysate within a defined section of the filter to maximize the concentration of microorganisms.

Once the microorganisms had been washed, they were removed from the surface by firmly scraping the membrane with a polyester fabric-tipped microswab (Texwipe CleanTips swabs; catalog no. TX754B; Kernersville, NC). The swab was held nearly vertically and slightly tilted away from the user. Downward force sufficient to almost tear the membrane was applied to the swab. Strokes were made across the membrane in a nearly overlapping pattern across the entire area where lysate was applied. Organisms were then directly applied to disposable VMS target plates (catalog no. 220-99999-FM1; Shimadzu Biotech, Columbia, MD). The swab was held in the same orientation as it was during organism collection and was firmly blotted (not wiped) onto a spot on the MALDI target plate. Immediately following application, the microorganisms were covered with 1 μl of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) matrix (catalog no. 411071; bioMérieux). The suggested addition of 1 μl of 28.9% formic acid (catalog no. 411072; bioMérieux) was eliminated in this study to obviate a Gram stain result prior to VMS analysis. When a sample needed to be retested, the volumes of blood culture broth and corresponding buffers were doubled. All other procedures remained the same.

With the vacuum still on, a 10% commercial bleach solution was added to the filter for decontamination, and the membrane was then discarded. The filter apparatus was again rinsed with bleach twice and with deionized water before processing of subsequent samples.

RESULTS

A total of 259 bottles comprising 225 monomicrobic and 28 polymicrobic positive blood cultures were included in the study. Six bottles were negative on subculture. Using this method, the VMS was able to identify organisms in 189 (73%) positive cultures to the species level (including instances where the VMS was able to correctly identify one organism in a polymicrobic bottle) and 51 (19.7%) gave no ID, while 6 (2.3%) IDs were incorrect (Table 1). The incorrect identifications obtained included one of each of the following pairs: a coagulase-negative staphylococcus (CoNS) was called Micrococcus luteus by VMS, Staphylococcus aureus was called Staphylococcus epidermidis, Acinetobacter baumannii was called Klebsiella pneumoniae, Candida albicans was called Moraxella catarrhalis, Corynebacterium was called Propionibacterium acnes, and Morganella morganii was called Proteus mirabilis (Table 2).

Table 1.

Results from all positive-blood-culture bottles processed

| Blood culture bottle and ID | No. (%) of bottles |

|---|---|

| All bottles | |

| Bottles with correct species ID by MALDI | 189a (73) |

| Bottles with correct ID only to genus/family level by MALDI | 6 (2.3) |

| Bottles with no ID by MALDI but with positive subculture | 51 (19.7) |

| Bottles with no ID by MALDI and no growth | 6 (2.3) |

| Bottles with incorrect ID by MALDI | 6 (2.3) |

| Total | 259 |

Thirteen of these organisms were single organisms identified from bottles with multiple organisms to the species level. Two organisms were identified to the species level with low discrimination (the MALDI-TOF VMS gave multiple species results, one of which was correct). Fifty-three of these organisms were determined to have essential agreement to the species level.

Table 2.

Discrepant IDs by the MALDI-TOF VMSa

| Organism ID by conventional method | Organism ID by VMS method |

|---|---|

| Coagulase-negative staphylococcus | Micrococcus luteus |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Staphylococcus epidermidis |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| Candida albicans | Moraxella catarrhalis |

| Corynebacterium | Propionibacterium acnes |

| Morganella morganii | Proteus mirabilis |

All of these identifications were obtained from MALDI results determined to be acceptable on the basis of confidence percentages.

Of the 225 monomicrobic bottles, the organisms in 176 (78.2%) were identified to the species level. Four organisms (1.7%) were identified to the genus level only. Forty (17.8%) bottles did not generate a VMS ID, and 5 (2.2%) yielded an incorrect result (Table 3). Thus, for the 185 monomicrobic cultures where identification was obtained, 97.3% of the IDs were determined to be correct. Organisms were considered to have essential agreement if the VMS ID and the IDs by conventional methods were in agreement at the family and genus levels, even if a species-level identification was provided by the VMS (but not the conventional methods).

Table 3.

Results of all monomicrobic organism IDs

| Organism | No. of isolates analyzed | No. (%) of species IDs consistent with reference IDa | No. (%) of isolates: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For which only genus ID was consistent with reference | With no MALDI ID | With incorrect ID | |||

| Staphylococcus (CoNS)b | 63 | 49c | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin susceptible) | 23 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Staphylococcus aureus (methicillin resistant) | 22 | 21 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Escherichia coli | 16 | 14c | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 11 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 7 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Candida parapsilosis | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Candida albicans | 6 | 5d | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Corynebacterium | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Enterococcus faecium | 5 | 4c | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Candida glabrata | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 3 | 2c | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Streptococcus, viridans group | 3 | 2e | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Propionibacterium acnes | 2 | 2c | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salmonella spp. | 2 | 2c | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Actinomyces meyeri | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Bacillus sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Bacteroides fragilis | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Candida sp. | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Candida tropicalis | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fusobacterium sp. | 1 | 1c | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lactobacillus sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Morganella morganii | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Micrococcus sp. | 1 | 1c | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Micrococcus luteus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pseudomonas sp. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Streptococcus, group B | 1 | 1c | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Streptococcus, group G | 1 | 1c | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 225 | 176 (78.2) | 4 (1.7) | 40 (17.8) | 5 (2.2) |

The reference ID consisted of routine laboratory workup, which was not to the species level where indicated (see footnote c).

Two organisms identified as Staphylococcus hominis by conventional methods are also included here.

Results for 48 CoNS isolates, 2 Salmonella isolates, and 1 isolate each of all other noted organisms are in essential agreement.

C. albicans included 1 isolate correct to the species level with low discrimination.

Viridans group streptococci included 2 isolates correct with low discrimination.

Of the 131 monomicrobic isolates that had at least one spot with a score of 99.9%, all were correctly identified to the species level. Of the 44 monomicrobic isolates that had at least one spot with a score of between 89.9 and 98%, 43 (97.7%) were correct to the species level. These included organisms identified only to the genus level by conventional methods but whose IDs were in agreement with the VMS IDs. One of these samples (2.3%) provided an incorrect identification. Among monomicrobic cultures, 50 (84%) Gram-negative bacteria, 111 (74.5%) Gram-positive bacteria, and 15 (94.1%) yeasts were correctly identified by VMS to at least the family level (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of identification of microorganisms by VMS directly from monomicrobic blood culture bottlesa

| Monomicrobic bottle | No. (%) of bottles |

|

|---|---|---|

| Total | With correct ID | |

| Bottles with VMS confidence scores of ≥99.9% | 131 | 131 (100) |

| Bottles with VMS confidence scores of 89–98% | 44 | 43 (97.7) |

| Bottles with Gram-positive bacteria | 149 | 111 (74.5) |

| Bottles with Gram-negative bacteria | 59 | 50 (84) |

| Bottles with yeasts | 17 | 15 (94.1) |

| Total | 225 | 180 (80) |

Results were determined by MALDI-TOF VMS.

Twenty-eight positive bottles were polymicrobic, and one organism of the mixture in each of 13 bottles was correctly identified to the species level (46.4%), while the organisms in 3 bottles were identified only to the genus level (10.7%). Eleven bottles (39.3%) gave no VMS ID, and one bottle had an incorrect result (3.6%). No more than one organism was identified from each bottle (data not shown).

For the 202 positive bottles in which the VMS produced an identification (either mono- or polymicrobic cultures), the results were correct to the species level for 188 (93.6%). Six (3.0%) of these were incorrect.

When available, organisms identified as CoNS by spot testing were run on the Vitek 2 system for species-level identification. Of the 22 such isolates, the IDs for 20 (90.0%) matched the VMS IDs to the species level, 1 had a low-discrimination match, and 1 was incorrectly identified.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the effectiveness of a new lysis-filtration method for identifying microorganisms directly from positive BacT/Alert blood culture bottles in a clinical setting. The organisms in approximately 80% of monomicrobic cultures were correctly identified, and when considering isolates with high-confidence-level results (99.9%), the VMS was able to correctly identify all monomicrobic isolates to the species level.

In this study, we included only isolates that had at least one spot yielding a match percentage greater than 75%. VMS does generate identifications at lower confidence levels, and of the 5 bottles that were eliminated due to low-confidence matches (average value, 40.9%), 4 had complete or partial matches to the species level.

When species-level results for CoNS obtained by the VMS were compared to Vitek 2 system results, the VMS was found to be correct 90.9% of the time. The ability of the VMS to provide species-level identification for CoNS could potentially help differentiate between contamination and pathogenic bacteria and has the potential to abrogate unnecessary antimicrobial therapy.

The different levels of microbial biomass in some positive-blood-culture bottles, as well as the autolysis of some species like Streptococcus pneumoniae, may contribute to the number of bottles that were unable to generate a MALDI result. Stevenson et al. (1) found that the minimal bacterial cell density for excellent spectrum generation by MALDI-TOF MS is 106 CFU/ml. This cell density is approximately the threshold of what this group considered to be normal for a positive-blood-culture bottle after examination of multiple positive bottles (12). Increasing the volume of blood processed with this method is one possible way to alleviate low cell density with some organisms. The bacterial cell density in a bottle could also be affected by incubation time in the bottle. In this study, there were some bottles that had different incubation times at room temperature due to laboratory restrictions. This could have affected the results, as some bacteria may have grown to the levels needed to be identified by MALDI or to levels such that bacteria would be too dense to allow identification. When used in a clinical setting, bottles would most likely be analyzed immediately after flagging positive, as suggested in the manufacturing protocol, and this would remove the risk of bacteria being too dense to analyze.

Our data suggest that if the process was able to generate an identification, it was correct to the species level 93.6% of the time. As found in previous studies (8, 12), the VMS was not able to readily distinguish between Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus pneumoniae. It was able to identify 1 of 2 Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates correctly to the species level, but the other isolate was identified as Streptococcus pneumoniae/S. mitis. In addition to this limitation, the incorrect results that we obtained would result in very different clinical outcomes and perhaps need to be more closely investigated.

The lysis buffer used in this protocol eliminates blood cells, while leaving microorganisms intact to undergo rapid analysis by MALDI-TOF MS. This method is advantageous, as it does not require centrifugation and produces a clean, concentrated sample of microorganism in less than 15 min.

Based on the results of this investigation, we have found that the VMS, when used in combination with the direct-from-positive-blood-culture method described herein, has the potential to greatly reduce the time to identification of possible agents of bacteremia/sepsis and to improve the delivery of appropriate antimicrobial therapy to the patient.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the medical technologists for their help in obtaining the patient samples necessary for this study. We thank Wm. Michael Dunne, Jr., for critical review of the manuscript.

Jay Hyman and John Walsh are senior staff scientists employed by bioMérieux, Inc.

No financial support other than provision of materials was provided for performance of the study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 19 December 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02326-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Stevenson LG, Drake SK, Murray PR. 2010. Rapid identification of bacteria in positive blood culture broths by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:444–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cherkaoui A, Hibbs J, Emonet S, Tangomo M, Girard M, Francois P, Schrenzel J. 2010. Comparison of two matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry methods with conventional phenotypic identification for routine identification of bacteria to the species level. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1169–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. La Scola B, Raoult D. 2009. direct identification of bacteria in positive blood culture bottles by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry. PLoS One 4:e8041 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neville SA, LeCordier A, Ziochos H, Chater MJ, Gosbell IB, Maley MW, Van Hal SJ. 2011. Utility of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry following introduction for routine laboratory bacterial identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:2980–2984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Christner M, Rohde H, Wolters M, Sobottka I, Wegscheider K, Aepfelbacher M. 2010. Rapid identification of bacteria from positive blood culture bottles by use of matrix-assisted laser desorption–ionization time of flight mass spectrometry fingerprinting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1584–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buchan BW, Reibe KM, Ledeboer NA. 2012. Comparison of the MALDI Biotyper system using Sepsityper specimen processing to routine microbiological methods for identification of bacteria from positive blood culture bottles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:346–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Drancourt M. 2010. Dectection of microorganisms in blood specimens using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry: a review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:1620–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ferroni A, Suarez S, Beretti JL, Dauphin B, Bille E, Meyer J, Bougnoux ME, Alanio A, Berche P, Nassif X. 2010. Real-time identification of bacteria and Candida species in positive blood culture broths by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1542–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lagace-Wiens PR, Adam HJ, Karlowsky JA, Nichol KA, Pang PF, Guenther J, Webb AA, Miller C, Alfa MJ. 2012. Identification of blood culture isolates directly from positive blood cultures by use of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry and a commercial extraction system: analysis of performance, cost, and turnaround time. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:3324–3328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Prod'hom G, Bizzini A, Durussel C, Bille J, Greub G. 2010. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry for direct bacterial identification from positive blood culture pellets. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1481–1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schmidt V, Jarosch A, Marz P, Sander C, Vacata V, Kalka-Moll W. 2012. Rapid identification of bacteria in positive blood culture by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31:311–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Piseth S, Drancourt M, Gouriet F, La Scola B, Fournier P, Rolain J, Raoult D. 2009. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:543–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.