Abstract

The adenovirus large E1A (L-E1A) protein is a prototypical transcriptional activator, and it functions through the action of a conserved transcriptional activation domain, CR3. CR3 interacts with a mediator subunit, MED23, that has been linked to the transcriptional activity of CR3. Our unbiased proteomic analysis revealed that human adenovirus 5 (HAdv5) L-E1A was associated with many mediator subunits. In MED23-depleted cells and in Med23 knockout (KO) cells, L-E1A was deficient in association with other mediator subunits, suggesting that MED23 links CR3 with the mediator complex. Short interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated depletion of several mediator subunits suggested differential effects of various subunits on transcriptional activation of HAdv5 early genes. In addition to MED23, mediator subunits such as MED14 and MED26 were also essential for the transcription of HAdv5 early genes. The L-E1A proteome contained MED26-associated super elongation complex. The catalytic component of the elongation complex, CDK9, was important for the transcriptional activity of L-E1A and HAdv5 replication. Our results suggest that L-E1A-mediated transcriptional activation involves a transcriptional elongation step, like HIV Tat, and constitutes a therapeutic target for inhibition of HAdv replication.

INTRODUCTION

Adenovirus E1A is the immediate-early viral gene that plays an essential role in viral replication by driving quiescent host cells into the cell cycle and by transcriptional activation of other viral early genes (reviewed in references 1 and 2). The E1A gene codes for two major protein isoforms, designated small E1A (S-E1A) and large E1A (L-E1A). The two protein isoforms differ only by the presence of a 46-amino-acid unique region (designated conserved region 3, or CR3) that is conserved among different adenovirus serotypes. While both E1A proteins can promote proliferation of quiescent target cells by activation of S phase genes, L-E1A is required for transcriptional activation of other viral early genes (3, 4). The role of CR3 in the transcriptional activation of viral early genes was established on the basis of results that showed a substantial decrease in expression of viral early genes in cells infected with different human adenovirus 5 (HAdv5) mutants with lesions in CR3 (3, 4). Further, protein microinjection and transcriptional tethering studies also demonstrated that a synthetic CR3 peptide (5, 6) or a CR3-Gal4 DNA binding domain (DBD) chimeric gene (7, 8) can activate viral early promoters. Although E1A CR3 constitutes a powerful trans-activation domain of a viral transcriptional activator and has been intensely investigated as a model trans-activation domain, the mechanism by which it mediates transcriptional activation of other viral early genes remains incompletely understood. The N-terminal 40-amino-acid region of CR3 which forms the C-4 zinc finger (9) has been postulated to function as the trans-activation subdomain, as it is sufficient for transcriptional activation as a Gal4 DNA binding domain fusion protein. The N-terminal subdomain of CR3 has been implicated in the recruitment of cellular transcription factors, such as MED23 (10, 11). The short C-terminal region of CR3 appears to function as the promoter-targeting subdomain through interaction with different DNA binding factors, such as the ATF family members, Oct-4, and NF-Y (12–15). It is possible that an auxiliary region (AR1) juxtaposed to CR3 that enhances L-E1A-mediated trans-activation also plays a role in promoter targeting (16). The CR3 trans-activation domain has also been reported to be associated with the components of the proteasome complex (17) and p300/CBP (18) to promote CR3-dependent transcriptional activation. It should be noted that the activities of different CR3-interacting factors were studied mostly as a CR3-Gal4-DBD fusion protein in transient-transfection assays, making it difficult to formulate a general model for transcriptional activation of the viral early genes by L-E1A in the context of viral infection.

CR3 forms a highly stable complex with the mediator subunit MED23, as the CR3-MED23 complex was shown to be stable under high-salt conditions in vitro (10). Among the different mediator subunits, MED23 is known to exist as a monomer as well as in complex with other mediator subunits, which might explain the interaction of MED23 monomer with CR3 in vitro (11). It appears that MED23, in addition to being a component of the 31-subunit mediator complex (19), also may form a subcomplex with a select number of subunits, such as MED24 (TRAP100) and MED16 (TRAP95) (11, 20). In adenovirus-infected cells, L-E1A was shown to be associated with a small fraction of the mediator complex (21), suggesting that L-E1A associates with a single subunit of MED23 as well as with a larger mediator complex. It is not known whether the mediator complex is recruited by L-E1A through interaction with MED23. In Med23 knockout (KO) mouse embryo fibroblasts, the trans-activation function of CR3 was abolished when assayed using the Gal4-DBD tethering transcriptional assay (11). The CR3 regions of several HAdv types have also been reported to bind with MED23 (22). In Med23 KO cells infected with the mouse adenovirus 1 (MAdv 1) (which codes for an E1A protein that contains a CR3 domain related to HAdv5 CR3), the levels of early gene transcription were retarded, suggesting that Med23 plays an important role in the transcriptional activity of MAdv E1A (23). Although MED23 has been shown to promote transcription at the recruitment and postrecruitment steps in transcriptional initiation by EGR 1 (24), the precise role of MED23 in the transcriptional activation of HAdv5 early genes remains to be elucidated. Since the biochemical activities of the individual components of the mediator complex are beginning to emerge, it may now be possible to uncover the role of individual mediator subunits in CR3-mediated transcriptional activation. In this report, we discovered the prominent presence of most mediator subunits in the L-E1A proteome. We show that MED23 links the CR3 trans-activation domain with the mediator complex, and some of the mediator subunits, such as MED26 and the MED26-associated super elongation subcomplex (SEC), are critically important for E1A-mediated transcriptional activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and plasmids.

HeLa and U2OS cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. KB suspension cells were maintained in Joklik modified minimal essential medium (MEM) containing 5% horse serum (Sigma). Wild-type (wt) murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) and Med23 KO MEFs were maintained in Knockout DMEM (Life Technologies) supplemented with β-mercaptoethanol, nonessential amino acids, and l-glutamine. Construction of HAdv5-12S (Flag/hemagglutinin [HA]-tagged S-E1A; HF-12S), HF-13S, and the plasmids used are described in Komorek et al. (25). Plasmids pcDNA5-Fg-ELL1, pcDNA5-Fg-ELL2, pcDNA5-Fg-EAF1, and pcDNA5-Fg-AFF4 were kind gifts from Ali Shilatifard. Plasmids pWZL neo myr-Fg-CDK9 and Fg-CDK9-T186A were purchased from Addgene.

siRNA transfection.

The dilution and transfection of short interfering RNA (siRNA) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Dharmacon RNAi Technologies). Cells were transfected with siRNA at a final concentration of 50 nM using DharmaFECT1 and infected with HAdv5 36 h after siRNA transfection. Knockdown of the target gene was determined by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) or Western blotting.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

Cells were collected at 17 h after viral infection or 12 to 24 h posttransfection (Lipofectamine 2000; Life Technologies) and lysed. The cell lysates were precleared with protein A-agarose beads and bound to anti-Flag beads. Bound protein complexes were washed and eluted with SDS sample buffer, resolved on NuPage 4 to 12% Bis-Tris gels (Life Technologies), and subjected to Western blotting. The following antibodies (Abs) were used for immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis: Flag Ab (Sigma); anti-HA Ab (Roche); mediator antibodies MED13L, MED12, MED14, MED24, and MED18 (Bethyl Laboratories); MED1, MED23, MED16, MED25, and MED4 (Santa Cruz); MED17 and MED26 (Assay Biotech); MED31 and MED13 (Abcam); MED10 and MED20 (Protein Tech); and MED22 (Abnova). Other antibodies used for Western blotting were cyclin C, cyclin T2, ELL2, AFF4, EAF1 (Bethyl Laboratories); CDK8, CDK9, cyclin T1, and actin (Santa Cruz); E1A (M73; Upstate); RNA polymerase II (pol II), RNA pol IISer2, and RNA pol IISer5 (Covance); E2-DBP and E1B-19K (gift from Maurice Green); E4-Orf4 (gift from Tamar Kleinberger); and E3-gp19K (gift from William S. Wold). The following antibodies were used for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis: CDK9 and RNA pol II (Santa Cruz), AFF4 (Bethyl), TBP (Abcam), and Flag (Sigma).

TAP and MS.

To isolate cellular protein complexes associated with S-E1A and L-E1A, a suspension culture of KB cells was mock infected or infected with HF-12S or HF-13S. Tandem affinity purification (TAP) and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analyses were carried out as previously described (25).

Gene expression and ChIP analyses.

Total RNA was isolated using a RiboPure kit (Ambion). Two hundred ng RNA was reverse transcribed using a high-capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and TaqMan primers and probes (Integrated DNA Technologies) on the 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantitation was done using comparative threshold cycles (CT). The PCR primers and probes are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Mouse mediator TaqMan primers and probes used for real-time PCR

| Target | Primer sequence |

Probe | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||

| MED1 | TGATCTTCCTGCGTGTTTCTTC | ACAACGGGATTCCTGTGCAA | TTCCCCAGCCAATTCCAGTATCTAAAGCA |

| MED14 | GCTTGGCCTCCTTAGCTAGAGA | ATCAATGGCATATGGAATAGCAAA | CTGGTCCATGCACGCCTGCCT |

| MED24 | CGAGCCTTGCTCTTTGACATT | GGATCACCTCTGAGCCATAGGT | CCTTCCTCATGCTATGCCATGTGGC |

| MED26 | CGATGGGCGCTTGAACAT | GAGGTGGGAATGCACATGATG | CCTTATGTCTGCTTGGACTGAGCACCTGA |

| MED31 | CCTTGGTCAGGTGGGACAAA | TGACGTCACCTTTCCCTGTGT | CCAAGGATCATGCTCTGCGTCACG |

| Cyclin C | CAGGACATGGGCCAGGAA | CGTCCTGTAGGTATCATTCACTATCC | ACGTGCTGCTTCCCCTTGCATGG |

| GAPDHa | GACGGCCGCATCTTCTTGT | CACACCGACCTTCACCATTTT | CAGTGCCAGCCTCGTCCCGTAGA |

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Table 2.

HAdv5 early gene TaqMan primers and probes used for real-time PCR

| Target | Primer sequence |

Probe | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||

| E1B-19K | AGGCTTGGGAGTGTTTGG | CACAGAAACCTCCAAAACCAAG | TGCTGTGCGTAACTTGCTGGAAC |

| E4-Orf4 | TGGCTTCGGGTTCTATGTAAAC | AATGTGTAGGTTGGCTGGG | TGGCTTATTCTGCGGTGGTGGA |

| E2-DBP | TTT CTT CCT CGC TGT CCA CGA TCA | AGA AGA CTC GTC ACA AGA TGC GCT | TT TGG ACG CA ATG GCC AAA TCC GCC |

| E3-gp19K | TTCGCAGCTGAAGCTAATGAGT | GCATAAACAGCATACTTGCCAATT | TAAAATGCACCACAGAACATGAAAAGCTGC |

For ChIP analysis, HeLa cells were transfected with 50 nM siRNA for MED23 and MED26, and 36 h after transfection cells were infected with HF-12S or HF-13S. One h after infection, cytosine arabinoside (Ara C) was added to a final concentration of 20 μg/ml to limit progression to the late phase of infection. Twelve h after infection, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde and lysed. Chromatin preparation and immunoprecipitation were carried out according to the manufacturer's protocol (MAGnify chromatin immunoprecipitation system; Life Technologies). Immunoprecipitated and/or input DNA was quantified using real-time PCR. ChIP quantitative PCR results were analyzed by fold enrichment. To determine fold enrichment, the average CT values for specific Ab immunoprecipitates were subtracted from nonspecific IgG immunoprecipitate (ΔCT). Finally, fold enrichment was calculated as 2−ΔΔCT (Life Technologies). The TaqMan primers and probes used for ChIP analysis are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

HAdv5 promoter region TaqMan primers and probes used for real-time PCR

| Promoter region | Primer sequence |

Probe | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | ||

| E2E −63 | GGAGGCTCTCTTCAGCAAATAC | CATTTGTGGCTGGTAACTCC | ACTCTTAAGGACTAGTTTCGCGCC |

| E2E −34 | AGCTGCCTGTATCACAAAAG | CGCTGGAGATGACGTAGTTT | AGGCTCTCTTCAGCAAATACTGCG |

| E2E +4417 | CTCCACTTAAACTCAGGCAC | CTGCGACTTCAAGATATCGG | ATCACCAACGCGTTTAGCAGGT |

| E4 −300 | GCAAGTTACTCCGCCCTAAA | TGAAGCCAATATGATAATGAGGG | CGCCACGTCACAAACTCCAC |

| E4 +1321 | TGGCTTCGGGTTCTATGTAAAC | AATGTGTAGGTTGGCTGGG | TGGCTTATTCTGCGGTGGTGGA |

Reporter assay.

U2OS cells were transfected with 300 ng of pGL2-GAL4-Luc6 (firefly luciferase), 50 ng of phRLO (Renilla Luciferase), 450 ng of salmon sperm DNA (carrier) along with 200 ng of pME1A-Ad5 CR3-Gal4-DBD, and increasing concentrations of pWZl-neo Myr-Flag-Cdk9 (200, 300, 400, and 500 ng) or Flag-Cdk9-T186A (200 and 500 ng) using TurboFect (Fermentas). For a control, vector (pM) was transfected with reporter plasmids and pWZl-neo Myr-Flag-Cdk9 (200 ng). Twenty-four h after transfection, cells were lysed and a dual-luciferase assay was carried out according to the manufacturer's specifications (Promega).

RESULTS

Association of mediator subunits with L-E1A.

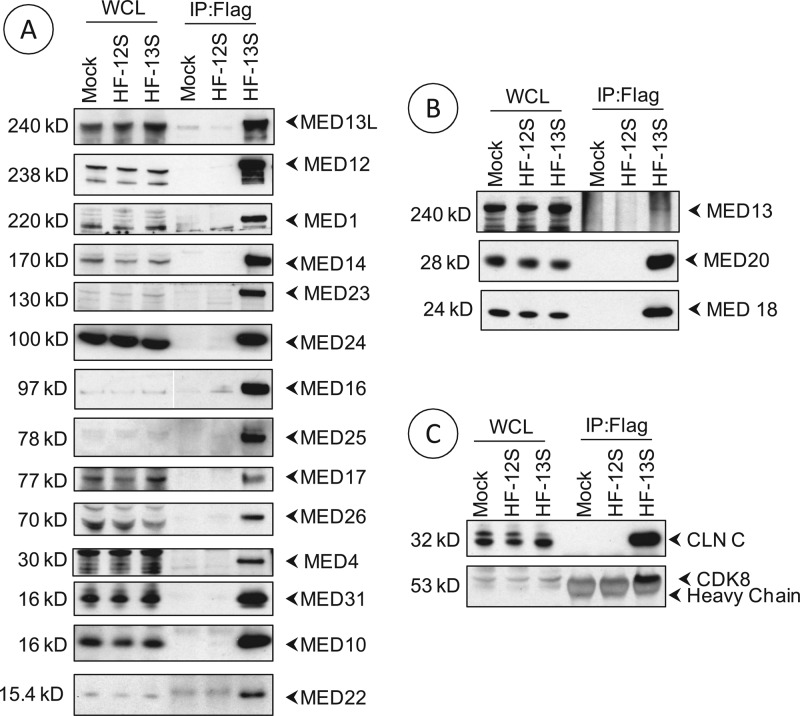

To identify cellular proteins associated with S-E1A and L-E1A, we carried out an unbiased proteomic analysis of human KB cells infected with HAdv5 mutants that expressed Flag and HA epitope-tagged versions of the individual E1A proteins. After tandem affinity purification and mass spectrometric analysis, we detected the specific association of several cellular proteins with L-E1A that were not present in the S-E1A protein complex. These cellular proteins included 15 different subunits of the mediator complex. The interaction of various mediator subunits with L-E1A was further substantiated by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1A). Since the mediator subunits identified in our analysis included those present in the head, tail, and middle of the mediator complex (reviewed in reference 26), it is possible that the L-E1A proteome contains other mediator subunits that were not apparent in our LC-MS/MS analysis. Western blot analysis for some subunits, such as MED13, MED18, and MED20, that were not detected in the LC-MS/MS analysis were apparent in the Western blot analysis of the L-E1A proteome (Fig. 1B). Western blot analysis also revealed the presence of cyclin C and CDK8 (Fig. 1C), which form the kinase module in association with MED12 and MED13 (26). Thus, it appears that L-E1A associates with the mediator complex that contains at least 18 subunits.

Fig 1.

Western blot analysis of mediator subunits associated with L-E1A. (A) Analysis of subunits detected by LC-MS/MS analysis. (B and C) Analysis of subunits that were not detected by LC-MS/MS. Whole-cell extracts or samples immunoprecipitated with the Flag Ab from mock-infected human KB cells or cells infected with HAdv5-12S (Flag/HA-tagged S-E1A, HF-12S) or HAdv5-13S (HF-13S) were probed with Abs specific to the indicated mediator subunits. MED15 was detected by LC-MS/MS analysis but was not analyzed by Western blotting. WCL, whole-cell lysates; CLN C, cyclin C.

MED23 links CR3 with the mediator complex.

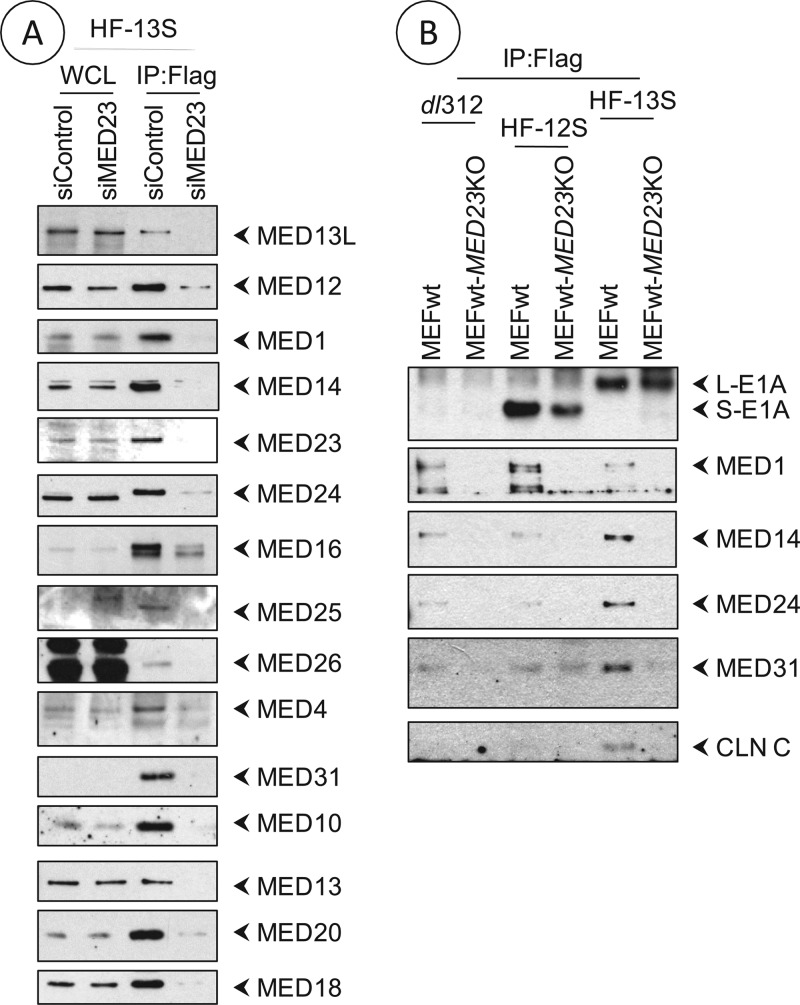

Previously, Boyer et al. (10) have reported direct high-affinity interaction of CR3 with MED23 in vitro. To determine whether MED23 links the mediator complex with CR3, we analyzed E1A-Flag immunoprecipitates prepared from HeLa cells transfected with control siRNA or Med23 siRNA and infected with HAdv5-13S (L-E1A). The presence of different mediator subunits in the L-E1A protein complex was significantly reduced in cells depleted of MED23 (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the mediator complex is linked to L-E1A through MED23. Additionally, we also analyzed E1A immunoprecipitates prepared from wt MEFs or Med23 KO MEFs infected with HAdv5 dl312 (E1A null), HAdv5-12S (S-E1A), or HAdv5-13S (L-E1A) for the presence of certain other mediator subunits by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2B). Mediator subunits, such as MED1, MED14, MED24, MED31, and cyclin C, were detected in the L-E1A protein complex prepared from wt MEF cells and not in the complex prepared from Med23 KO MEFs. These results suggest that MED23 serves as a scaffolding protein that links the E1A trans-activation domain (CR3) with the mediator complex.

Fig 2.

Interaction of mediator subunits with L-E1A in MED23-deficient cells. (A) Interaction in MED23-depleted HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transfected with pools of control siRNA or MED23 siRNA, and 36 h after transfection cells were infected with HF-13S (100 PFU/cell). Seventeen h after infection, whole-cell extracts were prepared, immunoprecipitated with the Flag Ab, and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. (B) Interaction in MEFs. wt MEFs or Med23 KO MEFs were infected with HAdv5-dl312, HF-12S, or HF-13S (500 PFU/cell) and immunoprecipitated with the Flag Ab and analyzed for selected mediator subunits.

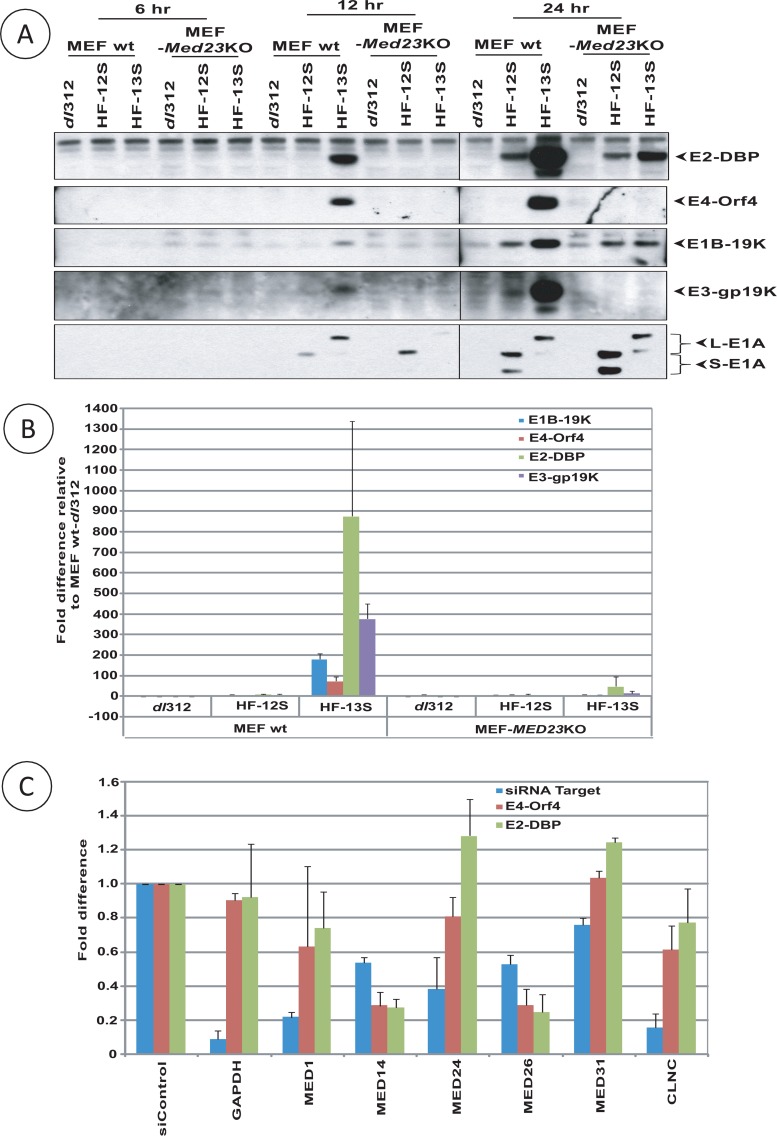

MED23 is essential for the activation of HAdv5 early genes.

Since MED23 links L-E1A to the mediator complex, we investigated the role of MED23 in HAdv5 early gene expression. For this purpose, we exploited the Med23 KO MEFs. wt MEF and Med23 KO MEFs were infected with HAdv5 dl312, HAdv5-12S (S-E1A), or HAdv5-13S (L-E1A). The levels of expression of various early gene regions (E1B, E2, E3, and E4) were first determined by Western blot analysis of the representative proteins from each early region (Fig. 3A). It should be noted that the levels of early gene expression in MEFs infected with HAdv5-13S could be compared to cells infected with HAdv5-12S, since HAdv5 does not replicate in mouse cells. These results revealed that the expression of various early gene regions, E1B (E1B-19K), E2 (DNA binding protein [DBP]), E3 (gp19K), and E4 (Orf4), was severely reduced in HAdv5-13S-infected Med23 KO MEFs compared to that in wt MEFs. Similar results were also obtained by quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the viral mRNA (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that MED23 plays a critical role in the transcriptional activation of various viral early gene regions by L-E1A during HAdv5 infection. In addition to CR3-dependent trans-activation of viral early genes, low levels of CR3/mediator-independent activation of some early genes is apparent, as reduced levels of E2-DBP and E1B-19K proteins can be detected in Med23 KO cells infected with HAdv5-12S or HAdv5-13S (Fig. 3A) at 24 h after infection.

Fig 3.

Role of mediator subunits in HAdv5 early gene expression. (A and B) Role of Med23. (A) wt MEFs and Med23 KO MEFs were infected with HAdv5-dl312, HF-12S, or HF-13S, and the expression of different early proteins (representatives of each early transcription unit) was analyzed by Western blot analysis using Abs specific to indicated viral proteins at 6, 12, and 24 h after infection. (B) The relative levels of transcriptional activation were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR analysis of RNA extracted from infected cells collected at 24 h after infection. (C) Role of other mediator subunits. wt MEFs were transfected with pools of control siRNA or siRNA against the indicated mediator subunits. Thirty-six h after transfection, cells were infected with HAdv5-13S and expression of E2-DBP and E4-Orf4 regions was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR at 12 h after infection. The results are expressed relative to cells transfected with control siRNA.

Differential effects of mediator subunits on HAdv5 early transcription.

Having established that MED23 links L-E1A with the mediator complex and the activity of MED23 is essential for the transcriptional activation of viral early genes, we then probed the functions of selected mediator subunits on the transcriptional activation of early genes E2 and E4 in wt MEF cells. Different mediator subunits, MED1, MED14, MED24, MED26, MED31, and cyclin C (kinase subcomplex), were depleted by siRNA transfection. The siRNA-transfected cells were then infected with HAdv5-13S, and the effects on the transcription of E2-DBP and E4-Orf4 regions were determined by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 3C). Although the levels of depletion were significant for MED1, MED24, and cyclin C, the levels of transcription of E2 and E4 genes were not significantly reduced. In contrast, partial depletion of mediator subunits MED14 and MED26 significantly reduced the transcription of both E2 and E4. These results suggest that different MED subunits exert differential effects on the transcription of HAdv5 early genes.

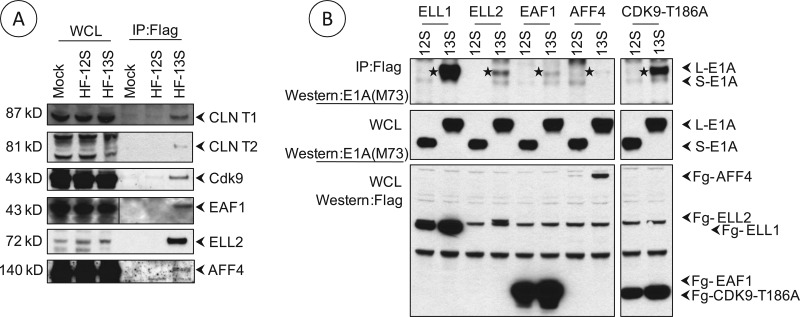

L-E1A proteome contains the super elongation complex.

Among the different mediator subunits, only a few have been examined for their biochemical activities thus far. For example, MED26 has recently been reported to serve as the docking site for several transcription elongation factors and the general initiation factor TFIID (27). Since our results (Fig. 3) suggested that MED14 and MED26 are important for transcriptional activation of HAdv5 early genes, we decided to focus on the role of MED26. We examined whether the L-E1A protein complex contained components of the SEC (28). Western blot analysis revealed the presence of super elongation complex constituents, such as CDK9, cyclin T1/T2, AFF4, ELL, and EAF, in the L-E1A protein complex and not in the S-E1A protein complex (Fig. 4A). The association of the SEC constituents with L-E1A was also ascertained in cells that were transfected with Flag-tagged versions of ELL-1, ELL-2, EAF-1, AAF-4, and CDK9 (mutant T186A) and infected with HAdv5-13S (L-E1A, untagged) or HAdv5-12S (S-E1A, untagged). Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitated proteins with the Flag Ab revealed the interaction of L-E1A and not S-E1A with different SEC constituents (Fig. 4B, top). (We note only a weak interaction of Flag-AFF4 with L-E1A, and this may be attributed to low levels of expression of Flag-AFF4 from the transfected plasmid). These results suggest that the SEC is an integral part of the L-E1A proteome. A different elongation complex that consists of factors such as NARG2 and KIAA0947 has also been reported to be associated with MED26 (27). We did not detect the association of endogenous NARG2 or tagged versions of the components of this subcomplex with L-E1A after transfection and infection with HAdv5-13S. The possibility that NARG2-containing subcomplex is a minor component of L-E1A proteome cannot be ruled out.

Fig 4.

Interaction of SEC with L-E1A. (A) The protein complexes associated with E1A proteins (Flag tagged) were immunoprecipitated with the Flag Ab from human KB cells infected with HF-12S or HF-13S. The protein blots were probed with Abs specific for various constituents of SEC. (B) The interaction of transfected members (Flag tagged) of SEC with E1A proteins (untagged) were determined by Western blotting using the Flag Ab or E1A Ab (M73). The bands corresponding to L-E1A in the top panels are indicated by stars.

SEC activates transcription of viral early genes.

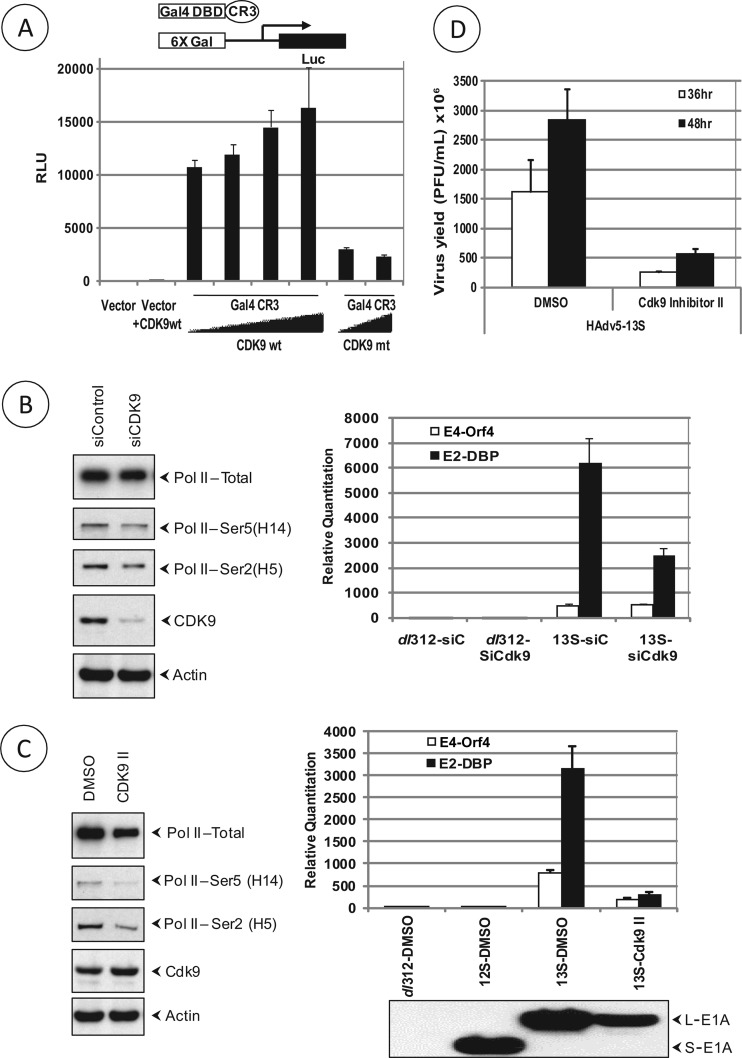

We examined the effect of the catalytic constituent of the SEC, CDK9, on the transcriptional activity of HAdv5 CR3. We first determined the effect of wt CDK9 and a CDK9 dominant-negative (DN) mutant on Gal4-DBD CR3-mediated transcriptional activation of the Gal4-luciferase reporter. Transfection of increasing concentrations of wt CDK9 increased the luciferase reporter activity while the DN mutant inhibited the luciferase activity (Fig. 5A), suggesting a critical role of CDK9 in CR3-mediated transcriptional activation. We also determined the role of CDK9 in the transcription of HAdv5 E2 and E4 early gene regions in HeLa cells that were depleted of CDK9 by transfection of siRNA (Fig. 5B). The CDK9-depleted cells were infected with HAdv5 dl312 or HAdv5-13S (L-E1A), and the transcription of E2-DBP and E4-Orf4 regions was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 5B, right). The transcription of E2-DBP was severely reduced, while the transcription of the E4-Orf4 region was moderately reduced.

Fig 5.

Effect of CDK9 on E1A trans-activation. (A) U2OS cells were transfected with the 6×Gal-luciferase reporter and Gal4-DBD-E1A-CR3 trans-activator construct in the presence of increasing concentrations of CDK9 or CDK9 DN mutant (T186A). The relative luciferase activity (compared to vector and wt CDK9-transfected cells) was determined. (B) HeLa cells were transfected with control or CDK9 siRNA pools and infected with HAdv5-dl312, or HF-13S. The level of CDK9 depletion was determined by Western blotting of RNA polymerase II (total), as well as Ser5- and Ser2-phosphorylated forms of pol II, and actin (left panel). The relative levels of expression of E2-DBP and E4-Orf4 regions were determined (right panel). (C) HeLa cells were infected with HAdv5-dl312, HAdv5-12S, or HAdv5-13S (25 PFU/cell) and treated with DMSO (vehicle) or CDK9 inhibitor II (30 μM) at 1 h postinfection with one change of drugs at 6 h postinfection. The effect on phosphorylation was determined using RNA pol II Abs H14 and H5 (left panel). The expression of E2-DBP and E4-Orf4 regions was determined by real-time RT-PCR at 12 h postinfection, and the relative levels were expressed compared to cells infected with HAdv5-dl312 that were treated with the vehicle (DMSO) (right panel). (D) Effect of CDK9 inhibitor on HAdv5 replication. HeLa cells were infected with HAdv5-13S at 5 PFU/cell and treated with DMSO or CDK9 inhibitor II (30 μM) at 1 h postinfection with one change of drugs at 24 h postinfection. The virus yield at 36 and 48 h postinfection was determined by plaque assay on human 293 cells.

We also determined the effects of a CDK9 inhibitor (inhibitor II) on the transcription of HAdv5 E2-DBP and E4-Orf4 regions by quantitative RT-PCR analysis. HeLa cells were infected with HAdv5-dl312, HAdv5-12S (S-E1A), or HAdv5-13S (L-E1A), and the infected cells were treated with CDK9 inhibitor II (29) for 12 h. The treatment with CDK9 inhibitor II inhibited phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II (Fig. 5C, left), while phosphorylation of Ser5 and Ser2 was reduced in cells treated with CDK9 inhibitor II. The transcription of both E2-DBP and E4-Orf4 regions was significantly reduced in cells treated with the inhibitor (Fig. 5C, right). Although there was a reduction in the level of L-E1A in cells treated with the CDK9 inhibitor, the effect on early gene transcription was more pronounced. Thus, all three assays suggest that CDK9 is critically important for the transcription of HAdv5 early genes by L-E1A. The treatment of HAdv5-infected HeLa cells with CDK9 inhibitor II also severely inhibited viral replication (Fig. 5D).

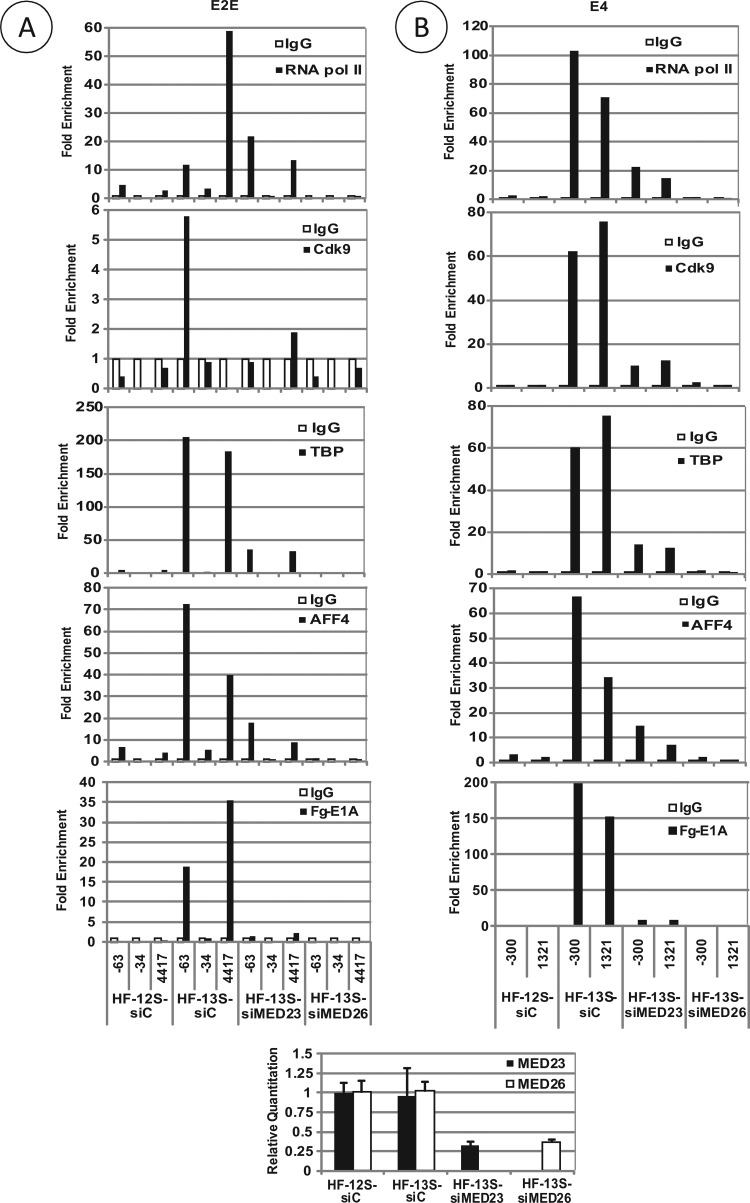

We also determined mediator-dependent localization of SEC components CDK9 and AFF4 at the viral early promoters by ChIP analysis. HeLa cells were depleted of MED23 or MED26 and infected with HAdv5-HF-13S and -HF-12S, and the viral chromatin was immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific to different transcription factors and analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 6). These results suggested the presence of both CDK9 and AFF4 along with L-E1A and TBP at the transcriptional control regions of the viral E2-E (Fig. 6A) and E4 (Fig. 6B) transcription units in cells treated with control siRNA and infected with HF-13S compared to cells infected with HF-12S. The localization of CDK9, AFF4, and TBP along with L-E1A was strongly reduced in MED23-depleted cells, suggesting that MED23-associated mediator complex targets E1A, TBP, and CDK9 to the viral early promoters. The recruitment of these factors to the viral promoters was also abolished in MED26-depleted cells, suggesting that MED26 targets TBP and SEC to viral E2E and E4 promoters. We note that the effect of MED26 depletion on targeting different factors to the early promoters was more pronounced than the effect of MED23 depletion. The possibility of differential mediator protein levels of the respective mediator subunit cannot be ruled out.

Fig 6.

Effect of MED23 and MED26 on promoter localization of SEC and TBP. HeLa cells were transfected with control, MED23, or MED26 siRNA pools and infected with 25 PFU/cell HAdv5, HF-12S, or HF-13S. The chromatin was prepared, the transcription factor occupancy was determined by ChIP analysis using Abs specific for RNA polymerase II, E1A (Flag), TBP, AFF4, and CDK9, and the relative occupancy was determined using primers specific to indicated promoter regions. The relative levels of depletion of MED23 and MED26 were determined by RT-PCR analysis and are shown at the bottom of the panel.

DISCUSSION

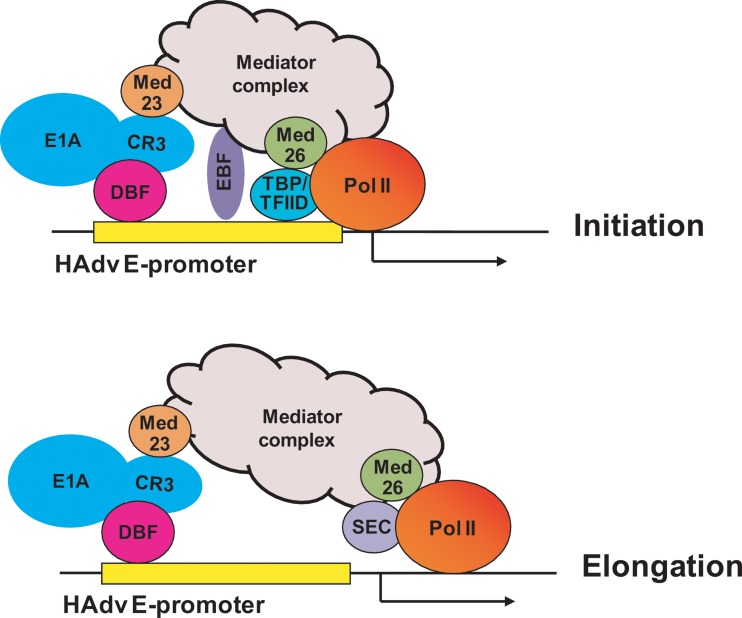

Despite intense investigations, a unified mechanism by which L-E1A activates transcription of HAdv early genes remains to be formulated. Here, we have shown that L-E1A is associated with many subunits of the mammalian mediator complex in human cells infected with HAdv5 through our unbiased proteomics analysis. Our work has linked L-E1A with the mediator complex through the mediator subunit MED23, which has previously been demonstrated to interact with E1A CR3 directly (10). We have identified a major mode of mediator-dependent transcriptional activation of viral early genes by L-E1A through the recruitment of the SEC, which promotes transcriptional elongation (28). In addition to Pol II elongation, it is possible that the mediator complex confers multiple coactivation functions for E1A. For example, MED26 has been shown to dock with the transcription initiation factor TFIID in addition to sequential docking with the elongation complex SEC (27). Accordingly, we have also observed that in MED23- or MED26-depleted cells, the occupancy of TBP at viral early promoters was impaired and localization of the components of SEC (CDK9 and AFF4) was reduced, suggesting a role for MED23 in the assembly of the initiation complex via MED26 during transcription of HAdv5 early genes. Therefore, we suggest that L-E1A trans-activates viral early genes by promoting transcription at the levels of initiation and elongation through the recruitment of the mediator complex (Fig. 7). Although we have not directly examined the effect of E1A on elongation, a previous study has reported E1A association with elongating RNA pol II (17).

Fig 7.

Model for transcriptional activation of HAdv early promoters by L-E1A. Based on our results, we suggest that the L-E1A CR3 trans-activation region targets the mediator complex to the viral early promoters through the mediator subunit MED23. The mediator complex is proposed to activate early gene transcription by targeting SEC (bottom), TBP/TFIID (top), and possibly other enhancer binding factors (EBF) to viral early promoters.

Although we did not address the comprehensive functions of the mediator complex in L-E1A-mediated trans-activation here, we have observed differential roles of selected mediator subunits. Our studies suggest that subunits such as MED14 also play a role in these activities. MED14 and associated factors such as MED7 have been shown to promote transcriptional activation through the enhancer binding factor Sp1 (30). Since HAdv early promoters contain Sp1 binding sites (31), it is possible that MED14 plays a role in targeting different enhancer binding factors, such as Sp1, to viral promoters. Our work suggests that the kinase module (CDK8/cyclin C/MED12/13) that is normally associated with transcriptional repression (26) as well as the mediator subunits, such as MED1 and MED31, do not critically influence the activity of E1A trans-activation function. It is possible that the role of some of these subunits is context specific, as they have been shown to promote transcriptional activation in different contexts (26). Our ChIP analysis has revealed that localization of TBP at the viral early promoters was deficient in cells depleted of MED23 and MED26, consistent with the report (27) that MED26 targets TFIID to the promoters. Several previous reports have suggested direct interaction of TBP with the activation subdomain of E1A-CR3 (that is also involved in direct binding with MED23) (32, 33). It is unclear whether TBP can interact with the CR3 region in vivo independently of the mediator complex. Nonetheless, it appears that the CR3 region has evolved as a powerful viral transcriptional activation domain by targeting both initiation and elongation factors, and possibly other enhancer binding factors, to viral early promoters for strong transcriptional activation of the viral genes for acute viral replication. The CR3 region has also been reported to interact with factors such as p300 (18) and the 20S proteasome (17). Further studies may be required to determine whether these factors function independently or in concert with the mediator complex to promote transcription of viral early genes. We also note that stable association of E1A with early promoters is affected in mediator-depleted cells (Fig. 6). Several earlier studies have reported that the C-terminal region of CR3 interacts with different DNA binding factors that may play a role in promoter targeting (12–15). It is possible that both the mediator complex and the DNA binding factors cooperatively play a role in E1A promoter localization (Fig. 7). Although mediator-independent interaction of transcription factors with CR3 contributes to the overall activity of CR3, it appears that the mediator complex constitutes the most critical component of L-E1A-mediated trans-activation, as we have observed severe defects in early gene expression in Med23-null MEFs infected with HAdv5 (Fig. 3).

It is remarkable that two unrelated viral transcriptional activators, HIV-1 Tat (34, 35) and HAdv5 L-E1A (present study), have evolved a conserved mechanism of transcriptional activation via the SEC. While Tat recruits SEC more directly to mediate transcriptional elongation on a proviral genome, E1A interacts with the SEC via the multisubunit mediator complex to promote transcriptional elongation on a free viral genome. Additionally, the mediator complex confers a transcriptional initiation function to E1A by targeting TFIID to the viral promoters. The involvement of the mediator complex in the E1A transcriptional function may facilitate the regulation of early gene expression under conditions of viral infection as well as achieve a balance between the activation of viral and cellular genes by L-E1A. It should be noted that the activity of MED23-dependent cellular transcription factor Elk-1 is regulated by phosphorylation by MAPK1 during Ras signaling (11). The involvement of SEC in L-E1A-mediated trans-activation of HAdv5 early gene expression suggests that it is possible to inhibit HAdv replication under conditions of pathological infection, as in immunocompromised individuals, by therapeutic targeting of SEC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by research grants CA-33616 and CA-84941 from the National Cancer Institute.

We thank Arnold Berk for Med23 KO and wt MEFs and Ali Shilatifard and Joe Mymryk for the gifts of plasmid vectors.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Berk AJ. 2005. Recent lessons in gene expression, cell cycle control, and cell biology from adenovirus. Oncogene 24:7673–7685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chinnadurai G. 2011. Opposing oncogenic activities of small DNA tumor virus transforming proteins. Trends Microbiol. 19:174–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berk AJ, Lee F, Harrison T, Williams J, Sharp PA. 1979. Pre-early adenovirus 5 gene product regulates synthesis of early viral messenger RNAs. Cell 17:935–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jones N, Shenk T. 1979. An adenovirus type 5 early gene function regulates expression of other early viral genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76:3665–3669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Green M, Loewenstein PM, Pusztai R, Symington JS. 1988. An adenovirus E1A protein domain activates transcription in vivo and in vitro in the absence of protein synthesis. Cell 53:921–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lillie JW, Loewenstein PM, Green MR, Green M. 1987. Functional domains of adenovirus type 5 E1a proteins. Cell 50:1091–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lillie JW, Green MR. 1989. Transcription activation by the adenovirus E1a protein. Nature 338:39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martin KJ, Lillie JW, Green MR. 1990. Evidence for interaction of different eukaryotic transcriptional activators with distinct cellular targets. Nature 346:147–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Culp JS, Webster LC, Friedman DJ, Smith CL, Huang WJ, Wu FY, Rosenberg M, Ricciardi RP. 1988. The 289-amino acid E1A protein of adenovirus binds zinc in a region that is important for trans-activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:6450–6454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boyer TG, Martin ME, Lees E, Ricciardi RP, Berk AJ. 1999. Mammalian Srb/Mediator complex is targeted by adenovirus E1A protein. Nature 399:276–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stevens JL, Cantin GT, Wang G, Shevchenko A, Berk AJ. 2002. Transcription control by E1A and MAP kinase pathway via Sur2 mediator subunit. Science 296:755–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chatton B, Bocco JL, Gaire M, Hauss C, Reimund B, Goetz J, Kedinger C. 1993. Transcriptional activation by the adenovirus larger E1a product is mediated by members of the cellular transcription factor ATF family which can directly associate with E1a. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:561–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu F, Green MR. 1994. Promoter targeting by adenovirus E1a through interaction with different cellular DNA-binding domains. Nature 368:520–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu F, Green MR. 1990. A specific member of the ATF transcription factor family can mediate transcription activation by the adenovirus E1a protein. Cell 61:1217–1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scholer HR, Ciesiolka T, Gruss P. 1991. A nexus between Oct-4 and E1A: implications for gene regulation in embryonic stem cells. Cell 66:291–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Strom AC, Ohlsson P, Akusjarvi G. 1998. AR1 is an integral part of the adenovirus type 2 E1A-CR3 transactivation domain. J. Virol. 72:5978–5983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rasti M, Grand RJ, Yousef AF, Shuen M, Mymryk JS, Gallimore PH, Turnell AS. 2006. Roles for APIS and the 20S proteasome in adenovirus E1A-dependent transcription. EMBO J. 25:2710–2722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pelka P, Ablack JN, Torchia J, Turnell AS, Grand RJ, Mymryk JS. 2009. Transcriptional control by adenovirus E1A conserved region 3 via p300/CBP. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:1095–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Conaway RC, Sato S, Tomomori-Sato C, Yao T, Conaway JW. 2005. The mammalian Mediator complex and its role in transcriptional regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 30:250–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ito M, Okano HJ, Darnell RB, Roeder RG. 2002. The TRAP100 component of the TRAP/Mediator complex is essential in broad transcriptional events and development. EMBO J. 21:3464–3475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang G, Cantin GT, Stevens JL, Berk AJ. 2001. Characterization of mediator complexes from HeLa cell nuclear extract. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:4604–4613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ablack JN, Pelka P, Yousef AF, Turnell AS, Grand RJ, Mymryk JS. 2010. Comparison of E1A CR3-dependent transcriptional activation across six different human adenovirus subgroups. J. Virol. 84:12771–12781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fang L, Stevens JL, Berk AJ, Spindler KR. 2004. Requirement of Sur2 for efficient replication of mouse adenovirus type 1. J. Virol. 78:12888–12900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang G, Balamotis MA, Stevens JL, Yamaguchi Y, Handa H, Berk AJ. 2005. Mediator requirement for both recruitment and postrecruitment steps in transcription initiation. Mol. Cell 17:683–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Komorek J, Kuppuswamy M, Subramanian T, Vijayalingam S, Lomonosova E, Zhao LJ, Mymryk JS, Schmitt K, Chinnadurai G. 2010. Adenovirus type 5 E1A and E6 proteins of low-risk cutaneous beta-human papillomaviruses suppress cell transformation through interaction with FOXK1/K2 transcription factors. J. Virol. 84:2719–2731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Malik S, Roeder RG. 2010. The metazoan Mediator co-activator complex as an integrative hub for transcriptional regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11:761–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takahashi H, Parmely TJ, Sato S, Tomomori-Sato C, Banks CA, Kong SE, Szutorisz H, Swanson SK, Martin-Brown S, Washburn MP, Florens L, Seidel CW, Lin C, Smith ER, Shilatifard A, Conaway RC, Conaway JW. 2011. Human mediator subunit MED26 functions as a docking site for transcription elongation factors. Cell 146:92–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lin C, Smith ER, Takahashi H, Lai KC, Martin-Brown S, Florens L, Washburn MP, Conaway JW, Conaway RC, Shilatifard A. 2010. AFF4, a component of the ELL/P-TEFb elongation complex and a shared subunit of MLL chimeras, can link transcription elongation to leukemia. Mol. Cell 37:429–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krystof V, Cankar P, Frysova I, Slouka J, Kontopidis G, Dzubak P, Hajduch M, Srovnal J, de Azevedo WF, Jr, Orsag M, Paprskarova M, Rolcik J, Latr A, Fischer PM, Strnad M. 2006. 4-Arylazo-3,5-diamino-1H-pyrazole CDK inhibitors: SAR study, crystal structure in complex with CDK2, selectivity, and cellular effects. J. Med. Chem. 49:6500–6509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ryu S, Zhou S, Ladurner AG, Tjian R. 1999. The transcriptional cofactor complex CRSP is required for activity of the enhancer-binding protein Sp1. Nature 397:446–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Berk AJ. 1986. Adenovirus promoters and E1A transactivation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 20:45–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Geisberg JV, Lee WS, Berk AJ, Ricciardi RP. 1994. The zinc finger region of the adenovirus E1A transactivating domain complexes with the TATA box binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91:2488–2492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Molloy DP, Smith KJ, Milner AE, Gallimore PH, Grand RJ. 1999. The structure of the site on adenovirus early region 1A responsible for binding to TATA-binding protein determined by NMR spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 274:3503–3512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. He N, Liu M, Hsu J, Xue Y, Chou S, Burlingame A, Krogan NJ, Alber T, Zhou Q. 2010. HIV-1 Tat and host AFF4 recruit two transcription elongation factors into a bifunctional complex for coordinated activation of HIV-1 transcription. Mol. Cell 38:428–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sobhian B, Laguette N, Yatim A, Nakamura M, Levy Y, Kiernan R, Benkirane M. 2010. HIV-1 Tat assembles a multifunctional transcription elongation complex and stably associates with the 7SK snRNP. Mol. Cell 38:439–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]