Abstract

Infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV), a member of the family Birnaviridae, infects young salmon, with a severe impact on the commercial sea farming industry. Of the five mature proteins encoded by the IPNV genome, the multifunctional VP3 has an essential role in morphogenesis; interacting with the capsid protein VP2, the viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genome and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase VP1. Here we investigate one of these VP3 functions and present the crystal structure of the C-terminal 12 residues of VP3 bound to the VP1 polymerase. This interaction, visualized for the first time, reveals the precise molecular determinants used by VP3 to bind the polymerase. Competition binding studies confirm that this region of VP3 is necessary and sufficient for VP1 binding, while biochemical experiments show that VP3 attachment has no effect on polymerase activity. These results indicate how VP3 recruits the polymerase into birnavirus capsids during morphogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) is the type species of the genus Aquabirnavirus and the causative agent of infectious pancreatic necrosis, a severe infection of juvenile salmonid fish that causes significant economic losses to the aquaculture industry. Due to its ecological impact, effort has gone into the study of both IPNV biology and the pathogenesis of the disease (1). Aquabirnaviruses belong to the Birnaviridae family, which also includes infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV), a member of the genus Avibirnavirus that infects young chickens (2, 3). IPNV and IBDV are the best-characterized birnaviruses, and members of this family have a number of unique features in common, such as their bisegmented double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genome (segments are denoted A and B), which is packaged in a nonenveloped single-shelled icosahedral capsid around 700 Å in diameter (4).

Genome segment B encodes VP1, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP), which is present in the virion in two forms: as a free protein and as VPg, covalently attached to the 5′ end of the two genomic segments (5–7). Birnavirus polymerases possess a noncanonical active site, where the viral RNA polymerase sequence motifs A-B-C are reordered C-A-B (8–10). Furthermore, for IPNV, it has been shown that mutation of the N-terminal serine residue (S2) abolishes the ability of VP1 to form covalent RNA polymerase complexes, suggesting that the extreme N terminus is the site of attachment to the RNA genome and formation of VPg (9).

Genome segment A encodes the polyprotein pVP2-VP4-VP3, which is cotranslationally cleaved by the virus-encoded protease VP4, releasing pVP2 and VP3 (11–13). The precursor pVP2 undergoes further processing to give mature VP2 (14, 15), the main viral structural protein, arranged as 260 homotrimers that form the T=13 laevo lattice of the capsid (16, 17).

VP3 has several putative roles in birnavirus morphogenesis: (i) it interacts with the major capsid protein VP2, (ii) it associates with the dsRNA genome, and (iii) it recruits the polymerase into capsids. IBDV VP3 interacts with the C terminus of pVP2 to support scaffold formation (18–20). Although VP3 was supposed to form an inner capsid layer for birnaviruses (17), the crystal structure of IBDV revealed only the outer VP2 shell (4), suggesting that the inner VP3 layer is disordered. VP3 from IBDV binds RNA (21), and IPNV VP3 (∼27 kDa) also forms complexes with the genomic RNA, organized as thread-like filaments (22), possibly reflecting its organization in the capsid. Yeast two-hybrid, coimmunoprecipitation, and in vitro pulldown experiments have broadly defined regions of VP3 which interact with the dsRNA genome and with VP1. For IBDV, the last 10 residues of VP3 are critical for VP1 binding and deletion of only the last residue abolished this interaction and the production of infectious progeny virus (23). For IPNV, a similar study demonstrated that the 62 C-terminal residues of VP3 harbor the VP1 interaction domain, while the 101 N-terminal residues of VP3 mediate self-association (Fig. 1A) (24). Furthermore, VP1-VP3 complexes were observed in the cytoplasm of IPNV-infected cells prior to the formation of mature virus particles, implying a role for VP3 in virus assembly. These studies also demonstrated that birnavirus VP3 binds genomic dsRNA, independent of the RNA sequence (23, 24).

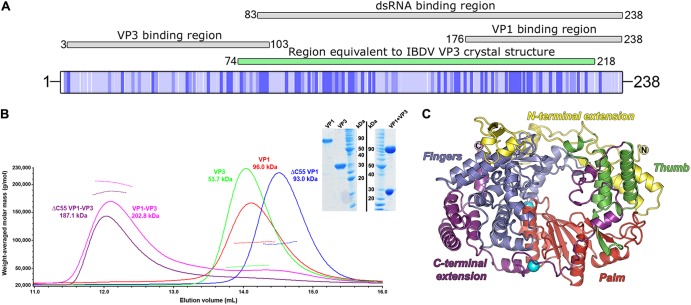

Fig 1.

Domain organization of VP3, VP1, and MALS analysis of the VP1-VP3 complex. (A) Schematic representation of the full-length IPNV strain Jasper VP3 polypeptide (UniProt identifier P05844), shaded from white (variable) to dark blue (conserved), based on the alignment in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. Regions of IPNV VP3 reported to perform VP3 binding, dsRNA binding, and VP1 binding activities (24) are shown above the VP3 schematic, labeled, and shaded gray. The region of IPNV VP3 equivalent to the reported structure of IBDV VP3 (25) is labeled and shaded green. (B) SEC-MALS of birnavirus VP1 and VP3 proteins. SEC elution profiles (absorbance at 280 nm, solid lines) are shown for IPNV VP1, ΔC55 VP1, VP3, and VP1-VP3 complexes. The weight-averaged molar mass is shown across the elution profiles as a dotted line and labeled for each sample, the mass of VP3 being consistent with it forming a dimer in solution. The inset shows SimplyBlue (Invitrogen)-stained SDS-PAGE of purified VP1-VP3 complex and individual components (VP1 and VP3) prior to complex formation. Molecular size markers are labeled in kDa. (C) Cartoon representation of the IPNV VP1 structure (colored by domain, with N and C termini labeled). The two K+ ions bound to VP1 are shown as oversized cyan spheres, the lower K+ ion not having been observed in previous IPNV VP1 structures.

Recently, efforts have been made to determine the detailed structure of VP3 and its interactions with the polymerase. Casanas et al. (25) reported the structure of the central region of IBDV VP3 (residues 92 to 220), which forms two α-helical domains connected by a flexible linker, arranged as an antiparallel dimer in the crystal. The second domain resembles some transcription factor regulators, suggesting a possible role in birnavirus transcription regulation (25). Earlier work by the same group attempted to determine the structure of IBDV VP1 complexed with a C-terminal peptide of VP3, the putative VP1 interacting region (26). Electron density, interpreted as belonging to a bound VP3 peptide, was observed within the nucleotide entry tunnel of VP1. Although this electron density was not clear enough to allow modeling of the VP3 peptide, it was implicated in a conformational change in VP1 that allowed substrate access to the active site (26), and indeed, the VP3 peptide was reported to activate the polymerase (26).

Despite these studies, the exact molecular determinants of VP1-VP3 binding have remained elusive. Here we provide the first detailed atomic view of the VP1-VP3 interaction by determining the crystal structure of VP1 bound to a C-terminal VP3 peptide at a resolution of 2.2 Å. Surprisingly, VP3 binds distally to the substrate entry tunnel of VP1, rather than occluding it as reported previously (26). Furthermore, we show that rather than activating VP1, VP3 has no effect on polymerase activity. This suggests a simple model whereby the VP3 C terminus tethers VP1 during IPNV morphogenesis and recruits both the polymerase and polymerase-associated genome into birnavirus capsids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of VP3.

A synthetic gene encoding full-length VP3 (residues 735 to 972 of the IPNV strain Jasper structural polyprotein [UniProt identifier P05844]), with a DNA sequence optimized for Escherichia coli expression (see the supplemental material) but an unchanged protein sequence (GeneArt) was amplified by PCR using KOD DNA polymerase (Novagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions (forward primer, 5′-AAGTTCTGTTTCAGGGCCCGACCGCAAGCGGTATGGATGCAG-3′; reverse primer, 5′-ATGGTCTAGAAAGCTTTAAACTTCACCATCATCACCGCTCG-3′). The PCR product was cloned into the pOPINF expression vector (encoding an N-terminal 3C cleavable His6 purification tag) using ligation-independent cloning (27) followed by sequence verification.

Production and purification of VP1, VP3, and the VP1-VP3 complex.

Full-length VP1 and ΔC55 VP1 were expressed and purified as described previously (9). Full-length VP3 was expressed in E. coli B834(DE3) cells grown in the presence of 50 μg/ml carbenicillin. Cultures were grown at 37°C until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached 0.6 to 0.8, at which point they were cooled to 20°C (or 25°C for biochemical analyses) and protein expression was induced by adding 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cells were incubated for a further 16 to 20 h, harvested by centrifugation (8,000 × g, 8°C, 20 min) and stored frozen (−80°C) until required. Cell pellets were thawed and resuspended on ice in 50 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, 50 mM imidazole, and 0.2% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (pH 7.5), supplemented with 400 units of bovine pancreas DNase I (Sigma) and one EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche) per 1 liter of cell culture. Cells were lysed using either sonication or a Basic Z model cell disruptor (Constant Systems) at 30,000 lb/in2, and cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation (35,000 × g, 8°C, 30 min). Cleared lysate was applied to a 1-ml HisTrap Ni2+ affinity column (GE Healthcare), which was washed with 50 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, and 50 mM imidazole (pH 7.5) and eluted in 50 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, and 500 mM imidazole (pH 7.5). The eluate was further purified by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 or 200 columns (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 20 mM Tris and 200 mM NaCl (pH 7.5) and an ÄKTA Purifier 10 UPC or ÄKTAxpress system (GE Healthcare). Fractions containing purified VP3 were pooled and incubated with 50 μl of rhinovirus 3C protease (starting concentration, 2 mg/ml) overnight at 4°C, to remove the N-terminal His6 tag before being passed through a 1-ml HisTrap Ni2+ affinity column to remove the His6-tagged 3C protease.

Purified, untagged VP3 at 1 mg/ml was mixed with either full-length or ΔC55 VP1 at 1 mg/ml and incubated for 1 h at 4°C to facilitate complex formation. The VP1-VP3 complex was purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography followed by size exclusion chromatography, and fractions containing pure complex were pooled and concentrated in 30,000-molecular-weight-cutoff centrifugal concentrators (Millipore).

MALS experiments.

Multiangle light scattering (MALS) experiments were performed immediately following analytical SEC by inline measurement of static light scattering (DAWN HELEOS II; Wyatt Technology), the differential refractive index (Optilab rEX; Wyatt Technology), and UV absorbance (Agilent 1200 UV; Agilent Technologies). Purified protein samples were injected onto an S200 10/300 size exclusion column (GE Healthcare) preequilibrated in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 200 mM NaCl at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Data were analyzed using the ASTRA software package (Wyatt Technology).

Binding experiments.

Peptide binding experiments were performed at 20°C in a PerkinElmer LS55 luminescence spectrometer with excitation/emission wavelengths of 480 nm/530 nm and slit widths of 15 nm/20 nm, respectively. The photomultiplier voltage was 800 V with the integration time at 5 s per measurement. A peptide corresponding to the C-terminal 14 residues of VP3 with an N-terminal fluorescein ([Fluorescein]SGSRFTPSGDDGEV; Designer Bioscience) was rehydrated and diluted in an 800-μl volume of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and 200 mM NaCl to a final concentration of 12.5 nM. VP1 (26.5 μM) was titrated into a continuously stirred cuvette containing the fluorescein-labeled peptide. Anisotropy was monitored continuously, and the values were recorded once they had stabilized for several consecutive readings. Dissociation constants (Kd) were calculated by fitting the titration data (corrected for dilution) to a one-site binding equilibrium model in Prism5 (GraphPad Software).

Competition assays were performed by equilibrating fluorescein-labeled VP3 peptide (as described above) with 0.3 μM VP1 before adding full-length VP3 protein (134 to 669 μM) and monitoring the anisotropy as described above. The Kd for VP3 was calculated using the method described in reference 28.

Crystallization and data collection.

Crystallization screening of either full-length VP1 and VP3 or ΔC55 VP1 and VP3 purified complexes was performed at concentrations between 2 to 4 mg/ml and at two different temperatures (21°C and 4°C) using 96-well sitting drop plates (Greiner) containing 100 nl protein and 100 nl reservoir (29). A single crystal appeared between 155 to 220 days after setting up crystallization trials containing full-length VP1 and VP3 (at 3.1 mg/ml), incubated at 4°C. The reservoir solution contained 20% (wt/vol) polyethylene glycol 3350 and 0.2 M potassium fluoride, and the crystal was cryoprotected by soaking in mother liquor supplemented with 25% glycerol. The crystal belonged to space group P21212, and diffraction data were collected at 100 K at Diamond Light Source beamline I04-1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Parameter | Values for VP1-VP3 native complexa |

|---|---|

| Data collection statistics | |

| Beamline | Diamond I04-1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9173 |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 68.4–2.2 (2.26–2.20) |

| Space group | P21212 |

| Unit cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 118.3, 341.9, 59.7 |

| Unique reflections | 123,796 (8,946) |

| Redundancy | 6.7 (6.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (99.2) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 12.0 (1.2) |

| Rmergeb | 0.12 (1.67) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 59.1–2.2 (2.26–2.20) |

| No. of reflections in working set | 123,689 (8,451) |

| No. of reflections in test set | 6,202 (461) |

| Rxpctc | 0.179 (0.229) |

| Rfreed | 0.215 (0.258) |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein/water/other | 18,165/1,109/24 |

| No. of atoms with alternate conformations | |

| Protein/water/other | 20/0/0 |

| Residues in Ramachandran favored region (%) | 97.5 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.1 |

| RMSDe | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.01 |

| Bond angle (°) | 0.99 |

| Average B factor | |

| Protein/water/other (Å2) | 55.7/54.1/57.5 |

| Average B factor for VP3 peptide | |

| Chain D/E/F (Å2) | 65.8/67.7/75.1 |

Values in parentheses refer to the appropriate outer shell.

Rmerge = Σhkl Σi|I(hkl;i) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/Σhkl ΣiI(hkl;i), where I(hkl;i) is the intensity of an individual measurement of a reflection and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the average intensity of that reflection.

Rxpct = Σhkl||Fobs| − |Fxpct||/Σhkl |Fobs|, where |Fobs| and |Fxpct| are the observed structure factor amplitude and the expectation of the model structure factor amplitude, respectively.

Rfree equals the Rxpct of test set (5% of the data removed prior to refinement).

RMSD, root mean square deviation from ideal geometry.

Structure solution, refinement, and analysis.

Diffraction data to a resolution of 2.2 Å were indexed and integrated using XDS (30) and scaled with SCALA (31) as implemented in the program xia2 (32). The structure was solved using molecular replacement with PHASER (33), taking the structure of IPNV VP1 (9), Protein Data Bank (PDB) identifier 2YI9, as a starting model. Manual model building was performed using COOT (34), and the structure was refined with BUSTER-TNT (35), imposing both noncrystallographic local structure similarity restraints (36), and TLS (translation/libration/screw) refinement, as implemented in the autoBUSTER framework (37). Structure validation was performed with the tools in COOT and the MolProbity Web server (38). Refinement statistics are shown in Table 1. Molecular graphics were generated with PyMOL (39), sequence alignments were generated with Clustal W (40) and ESPript (41), and superpositions were performed with SHP (42). The VP1-VP3 crystal structure was analyzed using the protein interfaces, surfaces, and assemblies service (PISA) at European Bioinformatics Institute (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/prot_int/pistart.html) (43) and the Protein Interactions Calculator (44). Structure factors and final refined coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession code 3ZED.

RNA polymerization activation/inhibition assay.

The IPNV RdRP was expressed and purified (9), and the sΔ+CCC single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) template (713 nucleotides) was generated as described previously (45). VP1-catalyzed replication assays were incubated with 0- to 50-fold molar excess of the full-length VP3 protein or the synthetic VP3 peptide for 10 min on ice prior to the addition of ssRNA template and nucleotides (1 mM ATP, GTP, and 0.2 mM CTP, UTP supplemented with 0.3 pmol [α32P]-UTP). Following 2 h of incubation at 37°C, the reactions were stopped by the addition of 2× loading buffer (46), and the reaction products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 0.8% (wt/vol) agarose gel (Tris-borate-EDTA [TBE]) (47). Signals were collected by autoradiography on BAS1500 image plates (Fujifilm) and scanned using a Fuji BAS-1500 phosphorimager (Fujifilm). Densitometry was performed using AIDA Image Analyzer software (version 4.50; Raytest Isotopenmessgeräte GmbH), measuring the total lane and specific band intensities in one-dimensional evaluation mode using lane and peak determination with automatic background subtraction.

RESULTS

VP3 readily forms complexes with VP1.

Complexes of either full-length VP1 and VP3 or ΔC55 VP1 and VP3 were prepared by mixing individually purified proteins and repurifying by Ni2+ affinity and size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 1B). These complexes were characterized by SEC-MALS and were observed to form higher molecular mass oligomers than their individual components (Fig. 1B). Both full-length VP1 and ΔC55 VP1 formed complexes with VP3, suggesting that the extreme C terminus of VP1 is not required for VP3 complex formation. From the SEC-MALS results, the stoichiometry of the purified VP3-VP1 complex is close to 2:2 (Fig. 1B). When VP3 is present in excess, apparent mass is more consistent with a 2:1 VP3-VP1 complex (data not shown), suggesting that VP1 and VP3 are in dynamic exchange.

The crystal structure of the complex between full-length VP1 and VP3 was solved by molecular replacement using the structure of IPNV VP1 (9) as a search model and refined to a resolution of 2.2 Å with residual Rxpct = 0.179 and Rfree = 0.215 (Table 1). The final structure is of high stereochemical quality with 98% of the residues occupying the favored region of the Ramachandran plot. Three copies of VP1 are present in the asymmetric unit (AU) of the crystal, and electron density was observed from residues 27 to 792 for each chain of VP1 (no density was observed for residues 1 to 26 and 793 to 845). Additional density, not attributable to VP1, was observed bound to the canonical RdRP fingers domain in all three copies of VP1. This density was unambiguously assigned as the last 12 residues of the IPNV VP3 C terminus and modeled into the density. The presence of three copies of the VP1-VP3 peptide complex in the crystallographic AU corresponds to a solvent content of 46%, consistent with the resolution of the data obtained; the lack of additional density beyond the peptide suggests that the remainder of VP3 had degraded. In one copy of the complex, continuous electron density is observed for the VP3 peptide residues 227 to 238; the other two copies of the peptide in the AU contain a break in the peptide density for residues 234 to 237 (SGDD). Apart from this difference, the three copies of the complex in the crystallographic asymmetric unit were essentially identical (average root mean square deviations [RMSD] over all the C-αs, 0.38 and 0.19 Å, between the copies of VP1 and VP3, respectively). Electron density was also observed for a second K+ ion binding site, in addition to the single K+ ion observed bound in a previous structure of IPNV VP1 (9). This new K+ ion binds on a surface-exposed region of the C-terminal extension domain of VP1 (Fig. 1C).

Structural basis for the VP1-VP3 interaction.

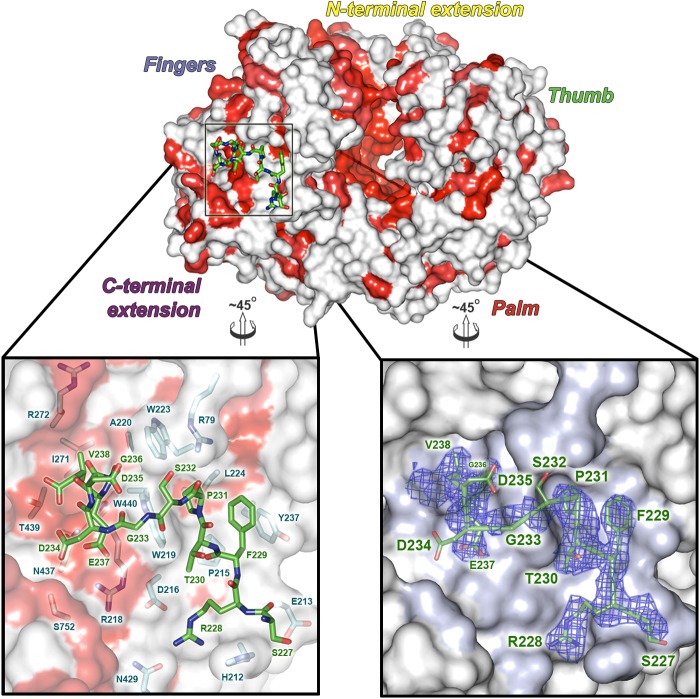

The VP3 peptide binds in an extended groove on the outside of the VP1 fingers domain (residues 161 to 343 and 406 to 475) (Fig. 2) and is anchored at either end by a pair of charge-based and hydrophobic interactions. At one end of the groove, VP3 residue R228 forms a salt bridge with D216 of VP1 while F229 of VP3 stacks against the side chain of VP1 Y237 (Fig. 2). At the C terminus of the VP3 peptide, E237 forms an ion pair with VP1 residue R218, and the final residue of VP3 (V238) pokes into a hydrophobic pocket lined by VP1 residues A220, I271, R272, and W440. The intervening residues of the VP3 peptide (230-TPSGDDG-236) form mainly backbone interactions with the VP1 groove. In total, some 800 Å2 of solvent-accessible area is buried from the VP3 peptide upon binding VP1 (assessed by the PISA server) (43), a little over half of the total surface area of the peptide. A superposition of unbound and VP3-bound VP1 gives an RMSD of 0.5 Å, over 758 equivalent C-α atoms (42), with no major conformational changes in the fingers domain of VP1 (0.3 Å RMSD, over 251 C-α equivalences). This suggests that the VP1 groove used to bind VP3 is preformed on the surface of VP1, ready to bind VP3.

Fig 2.

Structure of the VP1-VP3 complex. In the top panel, the IPNV VP1 polymerase is shown as a molecular surface, in the same view as in Fig. 1C. VP1 sequence conservation across birnavirus species is mapped onto the surface and colored from white (variable) to red (conserved), based on the alignment in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. The VP3 peptide (green sticks) is shown bound to the fingers domain of VP1 and boxed. The lower panels show expanded views of the VP3 peptide (residues labeled green) bound into the VP1 surface groove (shown semitransparent). In the left panel, residues from VP1 that bind VP3 are shown as sticks beneath the surface, colored, and labeled cyan. The right panel shows the experimental 2FO-FC electron density, calculated prior to modeling of the VP3 peptide, as a blue mesh (0.9 σ). The VP3 peptide is shown as sticks (green, with side chains labeled) to guide interpretation of the density.

Characterization of VP1-VP3 interaction.

The structure suggests that residues 227 to 238 of VP3 are key to interaction with VP1. This peptide was thus synthesized with an N-terminal fluorescein label, and fluorescence anisotropy measurements confirmed that it forms a tight complex with VP1, Kd = 0.11 (±0.01) μM (Fig. 3A; n = 2). To investigate if this was the primary mode of interaction of VP1/VP3, we then performed an experiment where prebound labeled peptide competed with full-length VP3 (Fig. 3B). This showed that VP3 successfully outcompeted the peptide at a sufficiently high concentration, indicating that the peptide binding mode was similar to that of full-length VP3. An analysis of the competition experiment suggests that the binding constant for full-length VP3 is ∼0.36 μM (28), a little weaker than the peptide, presumably due to entropic effects and/or conformational restraints in the context of the full protein. Clearly, the binding seen in the crystal is likely to represent an authentic picture of the binding of full-length VP3 to VP1; only the C terminus of VP3 binds strongly to VP1, the remainder being redundant.

Fig 3.

Fluorescence anisotropy of VP1-VP3 interactions and polymerase activity assay. (A) Fluorescence anisotropy study of the binding of fluorescently labeled VP3 C-terminal peptide (residues 227 to 238) to VP1. (B) Fluorescence anisotropy competition assay between unlabeled VP3 protein and a preformed complex between VP1 and fluorescently labeled VP3 C-terminal peptide. (C) Autoradiograph of IPNV VP1-VP3 catalyzed de novo replication reactions analyzed in a 0.8% agarose (TBE) gel. The leftmost lane includes a reference reaction (VP1 only) to which the VP1-VP3 reactions are compared. RNA polymerization activity is determined by image densitometry analysis of the total lane, whereas RNA-protein complex formation is assessed by measuring the intensity of both the unbound and bound dsRNA product.

VP1-VP3 complex formation does not alter the biochemical activity of VP1.

VP1 in complex with full-length VP3 or a synthetic VP3 peptide was characterized for de novo RNA synthesis activity using a 713-nucleotide ssRNA template. Although VP1-VP3 complex formation occurs readily, quantitative total lane image densitometry analysis of VP1-VP3-catalyzed replication assays reveals no stimulation of RNA polymerization (Fig. 3C; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). By comparison to the VP1 control reaction (Fig. 3C, lane 1), addition of VP3 yields a 0.9- to 1.2-fold change in total activity (see Table S1), which is well within the normal error range (±10%) for this assay. Further saturating the reaction with VP3 leads to a 0.7-fold reduction in total activity.

VP3 on its own is devoid of enzymatic activity, although the full-length protein does show an affinity for RNA that is not exhibited by the synthetic C-terminal peptide. VP1 also has RNA binding affinity, forming high molecular weight RNA-protein complexes during templated RNA synthesis (Fig. 3C, lane 1) (9). This phenomenon is strongly enhanced by the addition of VP3 (Fig. 3C, lanes 2 to 12). Measuring specific band intensities reveals that a mere 2-fold excess of VP3 yields a 7-fold increase in complex formation, whereas a 34-fold increase can be obtained when saturating the assay with a 50-fold excess of VP3 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Although supplementing VP1-catalyzed RNA polymerization reactions with an excess of full-length VP3 significantly enhances the appearance of RNA-protein complexes, it occurs at the expense of free RNA products (Fig. 3C; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). The RNA sequestering ability of the VP1-VP3 complex, and VP3 in particular, is clearly demonstrated by the retardation in electrophoretic mobility seen in the rightmost lanes of Fig. 3C.

DISCUSSION

Studies of the two best-characterized birnaviruses, IPNV and IBDV, have revealed that VP3 is a multifunctional protein with different activities throughout the viral life cycle (23, 24). In this study, we attempted to determine the molecular details of the interaction between IPNV VP3 with the RdRP polymerase VP1. We have crystallized a VP1-VP3 complex and determined its structure to a resolution of 2.2 Å. Although full-length dimeric VP3 was used during crystallization of the VP1-VP3 complex, the crystal packing is inconsistent with this being the species crystallized. Electron density shows only the C-terminal 12 residues of VP3 to be well ordered and bound into an extended groove on the VP1 fingers domain. The long period of crystal growth (∼6 months) suggests that proteolysis of the rest of VP3 had occurred. Fluorescence anisotropy shows that the affinity of full-length VP1 for the VP3 C-terminal peptide is tight (Kd, ∼0.1 μM) and that full-length VP3 binds almost as strongly and can compete with labeled VP3 peptide for VP1 binding (Kd for VP3, ∼0.4 μM), indicating that they both bind the same surface of VP1. Using the IPNV VP1-VP3 complex as a framework, we have modeled the IBDV VP3 peptide onto the structure of IBDV polymerase. Without significant readjustment of the conformation of the VP3 peptide seen in IPNV, a satisfactory docking is obtained, which conserves the pattern of favorable hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions seen between VP1 and VP3 in IPNV, with minimal side chain clashes.

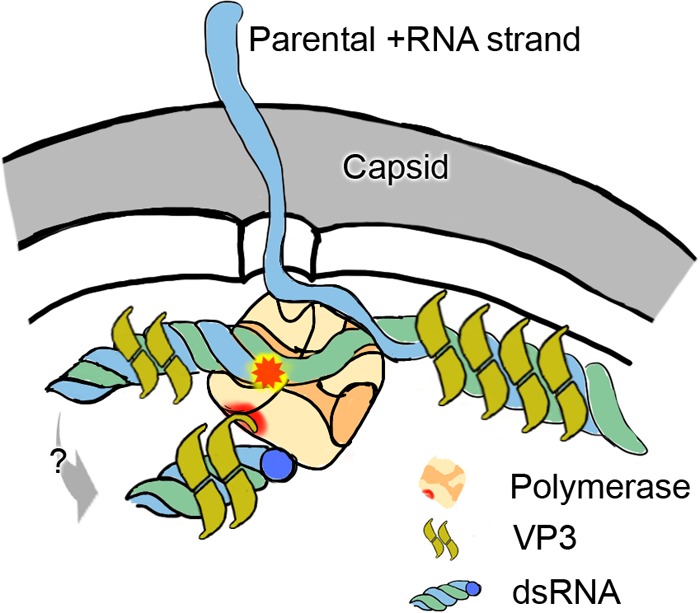

It is well established that IPNV VP1 and VP3 have a considerable affinity for RNA (6, 9, 24, 48). Previous studies show that the N-terminal part of VP3 is crucial for dsRNA binding (ssRNA binding was not assayed) and that VP1-VP3 complex formation does not require the presence of dsRNA (24). We have previously shown that the N-terminal tail of VP1 interacts strongly with ssRNA (9). The VP1-VP3 protein complex is thus capable of interacting with both single- and double-stranded RNA. Our data suggest a model whereby VP1-VP3 interactions are relevant for the morphogenesis of mature birnavirus particles, with VP3 acting as a modular protein, having distinct regions responsible for RNA binding, dimer formation, and VP1 attachment. This supports the notion that during viral infection, VP1 replicates the genomic ssRNA precursor molecules and, in conjunction with VP3, sequesters the viral genome, forming RNA-protein complexes (as shown in reference 24). Indeed VP1-VP3 complexes have been detected prior to the formation of mature virus particles, indicating a role in promoting the assembly process (24). These subassemblies act as scaffolds around which VP2 can assemble to form a precursor capsid, which undergoes maturation to yield an infectious virion. This is similar to, but simpler than, the viroplasm model proposed for rotavirus capsid assembly (49). There is no indication that the genome would be packaged into a preassembled capsid using an active packaging mechanism, such as a hexameric packaging motor. In fact, the evidence showing that the birnavirus virion contains a polyploid genome (50) argues against this and suggests that the packaging mechanism is stochastic.

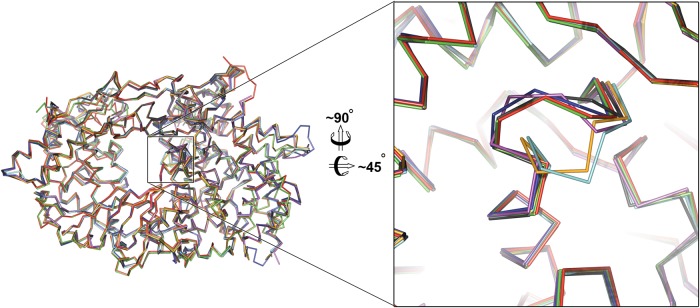

Our structural results are not in agreement with the suggestion (based on inference from inconclusive electron density) that VP3 binds close to the polymerase active site, increasing activity by stimulating movement of catalytic motif B (26). Indeed, in our previous structure of isolated IPNV VP1 (9) and also in an independent determination of the isolated IBDV VP1 structure (10), motif B is already in the catalytically competent conformation (Fig. 4). It is therefore unlikely that this movement is directly stimulated by VP3 binding. To address this discrepancy, we performed a detailed analysis of the effect of VP3 on the polymerase activity of VP1 and found that, as expected from our structural results, in contrast to the earlier report (26), VP3 attachment has no effect on the activity of VP1.

Fig 4.

Comparison of birnavirus VP1 B-loop motif between VP3 bound and unbound VP1 structures. The left panel shows birnavirus VP1 crystal structures superposed, in a 180° view around the y axis, to the view in Fig. 1C, looking toward the nucleotide entry tunnel. The B-loop (residues ∼468 to 477 in IPNV VP1) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) motif is boxed. The right panel shows a zoom of the catalytic motif B; ribbons are colored as follows (PDB identifiers in parentheses): green, IPNV VP1-VP3 complex presented in this paper; red, IPNV VP1 apo-form (2YIB); blue, IBDV VP1 (2PGG); magenta, IBDV VP1 soaked with a VP3 peptide (2QJ1); black, IBDV VP1 cocrystallized with a VP3 peptide (2R70); orange, IBDV VP1 Mg2+-bound (2R72); and cyan, IBDV VP1 apo-form (2PUS). Note that the B loop for the two IBDV VP1 structures either soaked or cocrystallized with VP3 (magenta and black) is in the same conformation as the independently determined structures of unbound IPNV and IBDV VP1 (red and blue, respectively). Further, the structure presented in this study, VP3 bound to the VP1 fingers domain (distal to the nucleotide entry tunnel) (green), also exhibits this conformation, suggesting that VP3 binding is not the driving force for this conformational change of the B loop.

The model we propose of the role of VP3 in birnavirus structure is shown schematically in Fig. 5. Note that the site of attachment to the polymerase is likely to orientate the polymerase within the capsid in such a way as to facilitate polymerase activity, required for the active transcriptional activity observed in birnavirus capsids. In summary, not only does this structure of the VP1-VP3 complex provide a detailed view of the precise molecular determinants of the interaction between birnavirus VP1 and VP3 proteins for the first time, but it also provides a simple model for a key stage in birnavirus morphogenesis.

Fig 5.

The complex of IPNV VP1 and VP3 in the context of the viral capsid. The 5′ end of a dsRNA segment (plus and minus strands are colored blue and green, respectively) is covalently attached to the actively transcribing VP1 polymerase (orange). The parental plus strand is released as mRNA during the semiconservative replication. VP3 (mustard) associates with the dsRNA, as well as forming a specific complex with VP1 (orange).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bert Janssen for helpful advice and the staff at beamline I04-1 at the Diamond synchrotron light source for technical support. We also thank Riitta Tarkiainen for her excellent technical assistance.

This work has been supported by Academy of Finland Academy Professor research funding (grants 255342 and 256518 to D.H.B.). S.C.G. is a Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 Research Fellow. The Cambridge Institute for Medical Research (CIMR) is in receipt of a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (079895). The work at Oxford is supported by the UK Medical Research Council and administrative support is provided by the Wellcome Trust (grant 075491/Z/04).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 2 January 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02939-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rodriguez Saint-Jean S, Borrego JJ, Perez-Prieto SI. 2003. Infectious pancreatic necrosis virus: biology, pathogenesis, and diagnostic methods. Adv. Virus Res. 62:113–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jackwood DJ, Saif YM, Hughes JH. 1982. Characteristics and serologic studies of two serotypes of infectious bursal disease virus in turkeys. Avian Dis. 26:871–882 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dobos P, Hill BJ, Hallett R, Kells DT, Becht H, Teninges D. 1979. Biophysical and biochemical characterization of five animal viruses with bisegmented double-stranded RNA genomes. J. Virol. 32:593–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coulibaly F, Chevalier C, Gutsche I, Pous J, Navaza J, Bressanelli S, Delmas B, Rey FA. 2005. The birnavirus crystal structure reveals structural relationships among icosahedral viruses. Cell 120:761–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dobos P. 1993. In vitro guanylylation of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus polypeptide VP1. Virology 193:403–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Calvert JG, Nagy E, Soler M, Dobos P. 1991. Characterization of the VPg-dsRNA linkage of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus. J. Gen. Virol. 72(Pt 10):2563–2567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Muller H, Nitschke R. 1987. The two segments of the infectious bursal disease virus genome are circularized by a 90,000-Da protein. Virology 159:174–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gorbalenya AE, Pringle FM, Zeddam JL, Luke BT, Cameron CE, Kalmakoff J, Hanzlik TN, Gordon KH, Ward VK. 2002. The palm subdomain-based active site is internally permuted in viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerases of an ancient lineage. J. Mol. Biol. 324:47–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Graham SC, Sarin LP, Bahar MW, Myers RA, Stuart DI, Bamford DH, Grimes JM. 2011. The N-terminus of the RNA polymerase from infectious pancreatic necrosis virus is the determinant of genome attachment. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002085 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pan J, Vakharia VN, Tao YJ. 2007. The structure of a birnavirus polymerase reveals a distinct active site topology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:7385–7390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee J, Feldman AR, Delmas B, Paetzel M. 2007. Crystal structure of the VP4 protease from infectious pancreatic necrosis virus reveals the acyl-enzyme complex for an intermolecular self-cleavage reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 282:24928–24937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Birghan C, Mundt E, Gorbalenya AE. 2000. A non-canonical lon proteinase lacking the ATPase domain employs the ser-Lys catalytic dyad to exercise broad control over the life cycle of a double-stranded RNA virus. EMBO J. 19:114–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duncan R, Nagy E, Krell PJ, Dobos P. 1987. Synthesis of the infectious pancreatic necrosis virus polyprotein, detection of a virus-encoded protease, and fine structure mapping of genome segment A coding regions. J. Virol. 61:3655–3664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Da Costa B, Chevalier C, Henry C, Huet JC, Petit S, Lepault J, Boot H, Delmas B. 2002. The capsid of infectious bursal disease virus contains several small peptides arising from the maturation process of pVP2. J. Virol. 76:2393–2402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sanchez AB, Rodriguez JF. 1999. Proteolytic processing in infectious bursal disease virus: identification of the polyprotein cleavage sites by site-directed mutagenesis. Virology 262:190–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Caston JR, Martinez-Torrecuadrada JL, Maraver A, Lombardo E, Rodriguez JF, Casal JI, Carrascosa JL. 2001. C terminus of infectious bursal disease virus major capsid protein VP2 is involved in definition of the T number for capsid assembly. J. Virol. 75:10815–10828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bottcher B, Kiselev NA, Stel'Mashchuk VY, Perevozchikova NA, Borisov AV, Crowther RA. 1997. Three-dimensional structure of infectious bursal disease virus determined by electron cryomicroscopy. J. Virol. 71:325–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ona A, Luque D, Abaitua F, Maraver A, Caston JR, Rodriguez JF. 2004. The C-terminal domain of the pVP2 precursor is essential for the interaction between VP2 and VP3, the capsid polypeptides of infectious bursal disease virus. Virology 322:135–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chevalier C, Lepault J, Da Costa B, Delmas B. 2004. The last C-terminal residue of VP3, glutamic acid 257, controls capsid assembly of infectious bursal disease virus. J. Virol. 78:3296–3303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maraver A, Ona A, Abaitua F, Gonzalez D, Clemente R, Ruiz-Diaz JA, Caston JR, Pazos F, Rodriguez JF. 2003. The oligomerization domain of VP3, the scaffolding protein of infectious bursal disease virus, plays a critical role in capsid assembly. J. Virol. 77:6438–6449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kochan G, Gonzalez D, Rodriguez JF. 2003. Characterization of the RNA-binding activity of VP3, a major structural protein of infectious bursal disease virus. Arch. Virol. 148:723–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hjalmarsson A, Carlemalm E, Everitt E. 1999. Infectious pancreatic necrosis virus: identification of a VP3-containing ribonucleoprotein core structure and evidence for O-linked glycosylation of the capsid protein VP2. J. Virol. 73:3484–3490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tacken MG, Peeters BP, Thomas AA, Rottier PJ, Boot HJ. 2002. Infectious bursal disease virus capsid protein VP3 interacts both with VP1, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and with viral double-stranded RNA. J. Virol. 76:11301–11311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pedersen T, Skjesol A, Jorgensen JB. 2007. VP3, a structural protein of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus, interacts with RNA-dependent RNA polymerase VP1 and with double-stranded RNA. J. Virol. 81:6652–6663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Casanas A, Navarro A, Ferrer-Orta C, Gonzalez D, Rodriguez JF, Verdaguer N. 2008. Structural insights into the multifunctional protein VP3 of birnaviruses. Structure 16:29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garriga D, Navarro A, Querol-Audi J, Abaitua F, Rodriguez JF, Verdaguer N. 2007. Activation mechanism of a noncanonical RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:20540–20545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berrow NS, Alderton D, Owens RJ. 2009. The precise engineering of expression vectors using high-throughput In-Fusion PCR cloning. Methods Mol. Biol. 498:75–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rossi AM, Taylor CW. 2011. Analysis of protein-ligand interactions by fluorescence polarization. Nat. Protoc. 6:365–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walter TS, Diprose JM, Mayo CJ, Siebold C, Pickford MG, Carter L, Sutton GC, Berrow NS, Brown J, Berry IM, Stewart-Jones GB, Grimes JM, Stammers DK, Esnouf RM, Jones EY, Owens RJ, Stuart DI, Harlos K. 2005. A procedure for setting up high-throughput nanolitre crystallization experiments. Crystallization workflow for initial screening, automated storage, imaging and optimization. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 61:651–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kabsch W. 1993. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26:795–800 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Evans P. 2006. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62:72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Winter G. 2010. xia2: an expert system for macromolecular crystallography data reduction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 43:186–190 [Google Scholar]

- 33. McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. 2007. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40:658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66:486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Blanc E, Roversi P, Vonrhein C, Flensburg C, Lea SM, Bricogne G. 2004. Refinement of severely incomplete structures with maximum likelihood in BUSTER-TNT. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60:2210–2221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Smart O, Brandl M, Flensburg C, Keller P, Paciorek W, Vonrhein C, Womack T, Bricogne G. 2008. Refinement with local structure similarity restraints (LSSR) enables exploitation of information from related structures and facilitates use of NCS. Abstr. Annu. Meet. Am. Crystallogr. Assoc., abstr TP139, p 117 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bricogne G, Blanc E, Brandl M, Flensburg C, Keller P, Paciorek P, Roversi P, Sharff A, Smart O, Vonrhein C, Womack T. 2011. BUSTER version 2.11.1. Global Phasing Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen VB, Arendall WB, III, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. 2010. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66:12–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. DeLano WL. 2008. The PyMOL molecular graphics system. DeLano Scientific LLC, Palo Alto, CA: http://www.pymol.org [Google Scholar]

- 40. Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gouet P, Robert X, Courcelle E. 2003. ESPript/ENDscript: extracting and rendering sequence and 3D information from atomic structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3320–3323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stuart DI, Levine M, Muirhead H, Stammers DK. 1979. Crystal structure of cat muscle pyruvate kinase at a resolution of 2.6 A. J. Mol. Biol. 134:109–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Krissinel E, Henrick K. 2007. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372:774–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tina KG, Bhadra R, Srinivasan N. 2007. PIC: Protein Interactions Calculator. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:W473–W476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wright S, Poranen MM, Bamford DH, Stuart DI, Grimes JM. 2012. Noncatalytic ions direct the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of bacterial double-stranded RNA virus φ6 from de novo initiation to elongation. J. Virol. 86:2837–2849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pagratis N, Revel HR. 1990. Detection of bacteriophage phi 6 minus-strand RNA and novel mRNA isoconformers synthesized in vivo and in vitro, by strand-separating agarose gels. Virology 177:273–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sambrook J, Russell D. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dobos P. 1995. Protein-primed RNA synthesis in vitro by the virion-associated RNA polymerase of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus. Virology 208:19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Trask SD, McDonald SM, Patton JT. 2012. Structural insights into the coupling of virion assembly and rotavirus replication. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:165–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Luque D, Rivas G, Alfonso C, Carrascosa JL, Rodriguez JF, Caston JR. 2009. Infectious bursal disease virus is an icosahedral polyploid dsRNA virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:2148–2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.