Abstract

Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) recognizes genomes of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses in the endosome to stimulate plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs). However, how and if viruses with single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genomes are detected by pDCs remain unclear. Here we have shown that despite the ability of purified genomic DNA to stimulate TLR9 and despite the ability to enter TLR9 endosomes, ssDNA viruses of the Parvoviridae family failed to elicit an interferon (IFN) response in pDCs.

TEXT

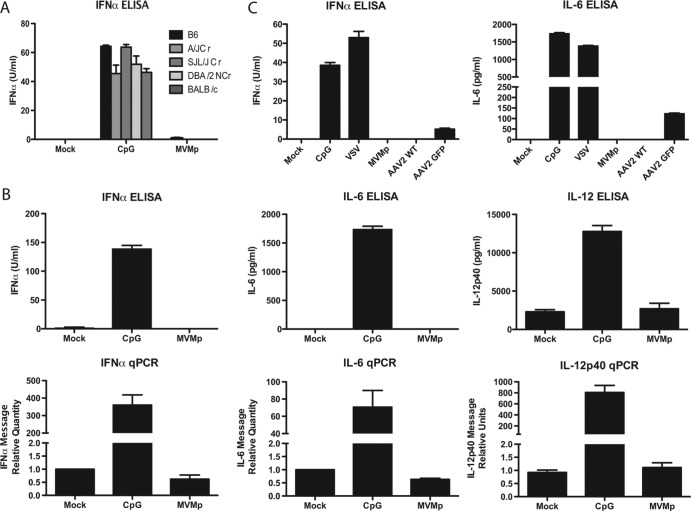

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are a specialized cell type that secretes large amounts of type I interferons (IFNs) upon viral infection. Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) recognizes the sugar backbone 2′-deoxyribose of phosphodiester DNA regardless of the CpG motif (1). While TLR9 recognition of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses is well established, whether and how single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses are detected by pDCs are unclear. To address this question, we used minute virus of mice (MVM), which is a nonenveloped virus in the family Parvoviridae with a small (∼5-kb) single-stranded linear DNA genome flanked by hairpin ends (2). The prototypical strain of MVM (MVMp) has tropism for many cell types, including hematopoietic cell types (3). MVMp virions were generated as described previously (4). Total bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 mice containing pDCs (5) were infected with MVMp for 24 h. In contrast to the high levels of stimulation of alpha interferon (IFN-α) secretion with synthetic oligonucleotide, CpG 2216, bone marrow cells infected with MVMp from various mouse strains (purchased from the National Cancer Institute and Jackson Laboratories) tested did not produce IFNs (Fig. 1A), as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a previously described protocol (5). Similarly, Flt3L-derived pDCs from C57BL/6 mice produced no measurable cytokines from pDCs in response to MVMp infection. The lack of cytokine secretion (Fig. 1A) correlated with the absence of mRNA (Fig. 1B) as determined by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) using primers listed in Table 1. These data indicated that MVMp fails to activate transcription of cytokine and IFN genes in pDCs.

Fig 1.

Murine bone marrow cells and pDCs do not respond to murine parvovirus. (A) Total bone marrow cells from mice of indicated backgrounds were transfected with CpG 2216 (5 μM) or infected with MVMp (20,000 genomes/cell). Supernatants were collected after 24 h, and IFN-α levels were measured by ELISA. (B) Flt3L pDCs were transfected with CpG 2216 (5 μM) or infected with MVMp (20,000 genomes/cell). Cells were collected after 8 h for analysis of IFN-α and IL-6 and IL-12p40 cytokine mRNA levels by RT-qPCR, and supernatants were collected after 24 h for analysis of IFN-α, IL-6, and IL-12p40 protein levels by ELISA. (C) Flt3L pDCs from C57BL/6 mice were transfected with CpG 2216 (5 μM) or infected with VSV (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 5), MVMp (20,000 genomes/cell), AAV-2 WT (10,000 genomes/cell), or AAV-2 GFP (10,000 genomes/cell). After 24 h, cell supernatant was collected, and IFN-α and IL-6 protein levels were measured by ELISA.

Table 1.

Primers used for quantitative PCR and quantitative RT-PCR

| Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| OK forward | GCAGGAGGACGAGCTGAAAT |

| OK reverse | CCCATTCCATGTCCTCGC |

| OK probe | FAM-TCCCAAGTAGTTTCCGCTCCTCGTTGTAAA-TAMRA |

| IFNα4 forward | CTGCTACTTGGAATGCAACTC |

| IFNα4 reverse | CAGTCTTGCCAGCAAGTTGG |

| IL-6 forward | CCTCTCTGCAAGAGACTTCCATCCAGTTGC |

| IL-6 reverse | GACTATTTTATGTAAATCTTTTACCTCTTGGTTGAAG |

| IL-12p40 forward | GGTGTAACCAGAAAGGTGCG |

| IL-12p40 reverse | AAGGTGTCATGATGAACTTAGG |

FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; TAMRA, tetramethylrhodamine.

To test the recognition of another ssDNA virus, we used Adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV-2), a Parvoviridae family member of the genus Dependovirus. A previous study showed that a recombinant AAV-2 vector encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) stimulates murine Flt3L pDCs through TLR9 and MyD88 (6). We confirmed that a GFP-expressing AAV-2 vector, UF11 AAV-2 GFP (Vector Core Laboratory), is indeed stimulatory in murine Flt3L-derived pDCs (Fig. 1C). Since the AAV-2 vector is deleted for the rep and cap genes, we next tested whether Flt3L pDCs could respond to wild-type (WT) AAV-2 (kindly provided by Jay Chiorini, Gene Therapy and Therapeutics Branch, NIDCR, NIH). Surprisingly, pDCs did not produce any cytokines in response to WT AAV-2 infection (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that one of the gene products of AAV-2 is able to block TLR9 signaling via an as-yet-unidentified mechanism.

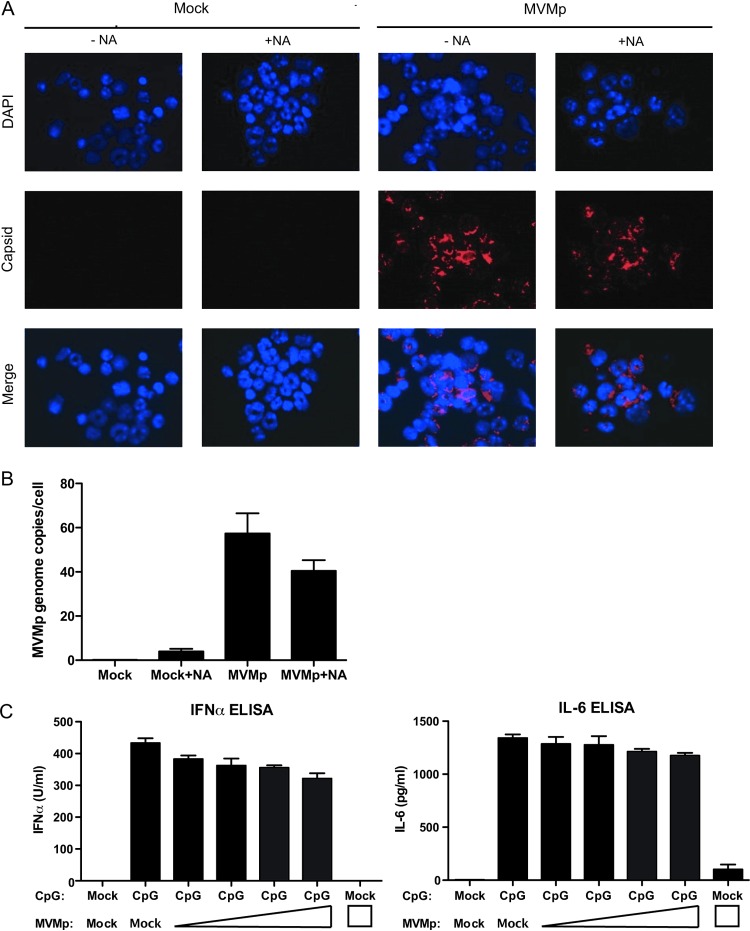

We next examined whether MVMp is internalized by pDCs. After incubation with MVMp for 1 h, bone marrow cells were treated or not with neuraminidase to cleave excess virus bound to sialoglycan receptors on the cell surface. Cells were then fixed and stained with an anticapsid antibody (7) to visualize the viral particles within the cell. We found that MVMp virions were present in essentially every cell in the MVMp-infected bone marrow culture, even following neuraminidase treatment (Fig. 2A), indicating that MVMp can bind to and be internalized by bone marrow cells. To confirm these results with pDCs, we performed a quantitative PCR-based uptake assay with MVMp-infected Flt3L cultures. Here, cells were infected with MVMp for 4 h and were treated or not, with neuraminidase for 2 h. Cells were washed to remove unbound virions and then lysed overnight to release viral DNA from the particles. An average of approximately 40 copies of MVMp genome had entered each pDC (Fig. 2B). Together, these data indicated that bone marrow cells and pDCs take up ample MVMp virions when incubated with high concentrations of MVMp and suggest that the lack of pDC responsiveness to MVMp reflects a postentry process.

Fig 2.

MVMp enters bone marrow cells and Flt3L pDCs. (A) Total bone marrow cells were infected with MVMp (20,000 genomes/cell) for 3 h, and then cells were treated with neuraminadase (NA) for 1 h to remove bound virions from the cell surface. Cells were stained with anticapsid antibody and 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) after being spun onto spot slides. Representative images are shown. (B) Flt3L pDCs were infected with MVMp (20,000 genomes/cell) for 4 h and then incubated with or without neuraminidase for 2 h. After extensive washing, cells were lysed and subjected to qPCR to quantify the number of MVMp genomes that had entered the cells. (C) Flt3L pDCs were infected with serial dilutions of MVMp ranging from 20,000 genomes/cell to 2,500 genomes/cell for 24 h. Cells were then stimulated with CpG 2216 (1 μM), and after 24 h, supernatants were collected and IFN-α and IL-6 protein levels were quantified by ELISA.

Next, we considered the possibility that MVMp might actively inhibit TLR9 function. To this end, we examined whether MVMp infection can inhibit CpG-dependent signaling through TLR9. Flt3L-derived pDCs from C57BL/6 mice were infected with serial dilutions of MVMp for 24 h. These cells were then stimulated with 1 μM CpG 2216. There was a marginal inhibition of IFN-α production in response to CpG stimulation (Fig. 2C), even at the highest input of MVMp, in which we found an average of 40 genome copies per cell (Fig. 2B). In addition, no inhibition of interleukin 6 (IL-6) secretion was detected by coinfection with MVMp. Thus, MVMp does not significantly impair TLR9 function in pDCs in response to exogenous CpG.

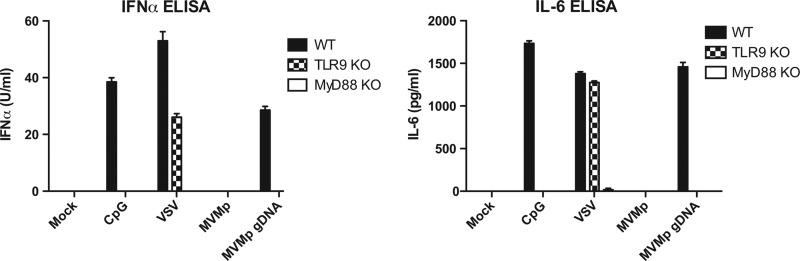

A possible explanation for the lack of pDC stimulation by MVMp is that the MVMp genomic ssDNA is intrinsically nonstimulatory for TLR9. To address this possibility, we stimulated Flt3L pDCs with purified viral genomic DNA delivered in liposomes. Genomic DNA was extracted from purified MVMp virions by digestion with proteinase K in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.5% SDS, pH 8.0, at 45 to 60°C for 6 h, and purified by Sephadex G-50 spin-column chromatography. One million pDCs were transfected with 1 to 2 ng of purified MVMp genome using DOTAP {N-[1-(2,3-dioleoyloxy)propyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammonium propane methylsulfate}. As expected, CpG and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) induced cytokine production from wild-type Flt3L-derived pDCs, and VSV also induced activation in TLR9 knockout cells, as reported previously (5, 8). Nevertheless, MVMp virions once again failed to activate any of these cells, whereas MVMp genomic DNA induced robust production of IFN-α and IL-6 in wild-type, but not TLR9-deficient (9) or MyD88-deficient (10) pDCs (Fig. 3). These data indicated that MVMp genomic DNA is not intrinsically defective in its ability to stimulate TLR9 within pDCs.

Fig 3.

MVMp genomic DNA stimulates pDCs via TLR9 and MyD88. Flt3L pDCs from C57BL/6, TLR9-deficient, or MyD88-deficient mice were transfected with CpG2216 (5 μM) or MVMp genomic DNA (10,000 genome equivalents/cell) or infected with VSV (MOI = 5) or with MVMp (10,000 genomes/cell). Cell supernatants were collected after 24 h, and IFN-α (top) or IL-6 (bottom) protein levels were measured by ELISA.

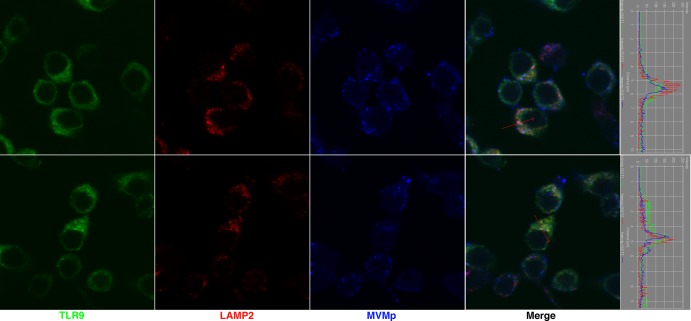

TLR9 becomes fully activated in the endosomes due to proteolytic cleavage by lysosomal cathepsins (11–13). This localization of TLR9 is necessary for downstream signaling through the adaptor MyD88 (14). Further, TLR9 enters the LAMP2+ lysosome-related organelle (LRO) to induce signaling for type I IFN production (15). To examine the intracellular compartment where MVMp localizes, we performed immunofluorescence confocal microscopy in RAW cells expressing TLR9-GFP (15). Interestingly, we detected some MVMp that colocalized with both TLR9 and LAMP2, a protein that marks the LRO compartment (15) (Fig. 4). However, the vast majority of MVMp virions were excluded from the TLR9+ or LAMP2+ compartment in RAW cells (Fig. 4).

Fig 4.

MVMp localization within TLR9 LRO. RAW264.7 cells expressing TLR9-GFP were infected with MVMp (20,000 genomes/cell) for 5.5 h. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-LAMP2 and anti-MVMp capsid antibodies and then subjected to confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown.

Our data showed that two ssDNA viruses escape TLR9 recognition in pDCs despite containing stimulatory genomic DNA. Possible explanations include intracellular trafficking and sequestration of genomic DNA in the endosomes. We have shown that a large portion of the MVMp virions is excluded from either LAMP2- or TLR9-containing vesicles in RAW cells, suggesting that a majority of MVMp traffics away from the TLR9 signaling endosomes in pDCs. In addition, the MVMp capsid is extremely stable, capable of withstanding severe environmental conditions, including low pH (7, 16). Thus, it is possible that the capsids remain impenetrable within the endolysosome, thereby restricting genomic DNA access for TLR9. Future studies are needed to understand the precise mechanism by which ssDNA viruses elude recognition by TLR9 in pDCs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Melissa M. Linehan, Miwa Sasai, Anthony D'Abramo, and Ellen Vollmers for technical assistance.

All procedures used in this study complied with federal guidelines and institutional policies of the Yale Animal Care and Use Committee.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI 081884 and AI 064705 (to A.I.) and CA 029303 (to P.T.) from the National Institutes of Health. L.M.M. is a recipient of the American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Haas T, Metzger J, Schmitz F, Heit A, Muller T, Latz E, Wagner H. 2008. The DNA sugar backbone 2′ deoxyribose determines toll-like receptor 9 activation. Immunity 28:315–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cotmore SF, Tattersall P. 1987. The autonomously replicating parvoviruses of vertebrates. Adv. Virus Res. 33:91–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raykov Z, Savelyeva L, Balboni G, Giese T, Rommelaere J, Giese NA. 2005. B1 lymphocytes and myeloid dendritic cells in lymphoid organs are preferential extratumoral sites of parvovirus minute virus of mice prototype strain expression. J. Virol. 79:3517–3524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xiao X, Li J, Samulski RJ. 1998. Production of high-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors in the absence of helper adenovirus. J. Virol. 72:2224–2232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lund J, Sato A, Akira S, Medzhitov R, Iwasaki A. 2003. Toll-like receptor 9-mediated recognition of Herpes simplex virus-2 by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 198:513–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhu J, Huang X, Yang Y. 2009. The TLR9-MyD88 pathway is critical for adaptive immune responses to adeno-associated virus gene therapy vectors in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119:2388–2398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Farr GA, Cotmore SF, Tattersall P. 2006. VP2 cleavage and the leucine ring at the base of the fivefold cylinder control pH-dependent externalization of both the VP1 N terminus and the genome of minute virus of mice. J. Virol. 80:161–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lund JM, Alexopoulou L, Sato A, Karow M, Adams NC, Gale NW, Iwasaki A, Flavell RA. 2004. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:5598–5603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Kaisho T, Sato S, Sanjo H, Matsumoto M, Hoshino K, Wagner H, Takeda K, Akira S. 2000. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature 408:740–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. 1998. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity 9:143–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ewald SE, Engel A, Lee J, Wang M, Bogyo M, Barton GM. 2011. Nucleic acid recognition by Toll-like receptors is coupled to stepwise processing by cathepsins and asparagine endopeptidase. J. Exp. Med. 208:643–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ewald SE, Lee BL, Lau L, Wickliffe KE, Shi GP, Chapman HA, Barton GM. 2008. The ectodomain of Toll-like receptor 9 is cleaved to generate a functional receptor. Nature 456:658–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park B, Brinkmann MM, Spooner E, Lee CC, Kim YM, Ploegh HL. 2008. Proteolytic cleavage in an endolysosomal compartment is required for activation of Toll-like receptor 9. Nat. Immunol. 9:1407–1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barton GM, Kagan JC, Medzhitov R. 2006. Intracellular localization of Toll-like receptor 9 prevents recognition of self DNA but facilitates access to viral DNA. Nat. Immunol. 7:49–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sasai M, Linehan MM, Iwasaki A. 2010. Bifurcation of Toll-like receptor 9 signaling by adaptor protein 3. Science 329:1530–1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cotmore SF, Tattersall P. 2012. Mutations at the base of the icosahedral five-fold cylinders of minute virus of mice induce 3′-to-5′ genome uncoating and critically impair entry functions. J. Virol. 86:69–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]