Abstract

The amount and nature of dietary starch are known to influence the extent and site of feed digestion in ruminants. However, how starch degradability may affect methanogenesis and methanogens along the ruminant's digestive tract is poorly understood. This study examined the diversity and metabolic activity of methanogens in the rumen and cecum of lambs receiving wheat or corn high-grain-content diets. Methane production in vivo and ex situ was also monitored. In vivo daily methane emissions (CH4 g/day) were 36% (P < 0.05) lower in corn-fed lambs than in wheat-fed lambs. Ex situ methane production (μmol/h) was 4-fold higher for ruminal contents than for cecal contents (P < 0.01), while methanogens were 10-fold higher in the rumen than in the cecum (mcrA copy numbers; P < 0.01). Clone library analysis indicated that Methanobrevibacter was the dominant genus in both sites. Diet induced changes at the species level, as the Methanobrevibacter millerae-M. gottschalkii-M. smithii clade represented 78% of the sequences from the rumen of wheat-fed lambs and just about 52% of the sequences from the rumen of the corn-fed lambs. Diet did not affect mcrA expression in the rumen. In the cecum, however, expression was 4-fold and 2-fold lower than in the rumen for wheat- and corn-fed lambs, respectively. Though we had no direct evidence for compensation of reduced rumen methane production with higher cecum methanogenesis, the ecology of methanogens in the cecum should be better considered.

INTRODUCTION

Global warming, caused by increasing atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, is a major worldwide environmental, economic, and social threat, and it is well documented that livestock production contributes to this problem (1). Enteric methane (CH4) is a natural byproduct arising from microbial fermentation of feeds within the rumen and, to some extent, in the cecum (2). Microbial populations in the digestive tract of ruminants ferment carbohydrates, proteins, and, to a lesser extent, lipids to produce mainly volatile fatty acids ([VFA]; acetate, propionate, and butyrate as the main ones), dihydrogen (H2), and carbon dioxide (CO2). Methanogenic Archaea mainly use H2 to reduce CO2 to CH4.

Diet manipulation is an effective way of decreasing enteric methane emissions in ruminant production systems (3). In intensive production, it is well established that high-cereal diets decrease enteric methane production. In parallel, these diets have been shown to decrease the diversity (4, 5) of methanogenic Archaea in the rumen of sheep. Concerning the effect of the nature of the cereal on methane production, few direct comparisons have been carried out. Beauchemin and McGinn (6) reported lower methane emissions in feedlot cattle fed corn (slowly degradable starch) than in animals receiving barley (readily degradable starch) finishing diets. Those authors suggested that this was mediated by the lower ruminal pH observed with the corn diet. In the present study, we hypothesized that the inclusion of readily degradable starch in the diet would shift plant cell wall degradation from the rumen to the cecum (7), providing more organic matter for cecal fermentation.

The cecum of ruminants harbors a complex microbial community (8, 9), but information about its members and particularly the methanogenic Archaea is scarce. Moreover, to our knowledge, there are no studies reporting the effect of dietary starch on the community of methanogens in the cecum.

The aim of this work was to compare the methanogenic communities in terms of diversity and metabolic activity in the rumen and cecum of growing lambs fed either corn (slowly degradable starch) or wheat (readily degradable starch) diets. By using these contrasting starch cereals, we sought to bring out differences between the rumen and cecum microbiota. We also measured in vivo methane emissions by lambs. In order to compare the two digestive compartments, we measured the ex situ methanogenic potential of the contents of the rumen and cecum, as well as their capacity to degrade wheat or corn in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, diet, and experimental design.

The study was conducted at the animal experimental facilities of INRA's Herbivore Research Unit in Saint-Genès Champanelle (France). Animal procedures were in accordance with the guidelines for animal research of the French Ministry of Agriculture and applicable European guidelines and regulations for animal experimentation (http://www2.vet-lyon.fr/ens/expa/acc_regl.html). The experimentation protocol was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation, approval number CE2-10.

Twelve INRA 401 newborn male lambs were separated in two homogenous (age, weight at birth) groups. Lambs were kept with their mothers until weaning at the age of 9 weeks. In each group, ewes were adapted progressively to high-grain-content diets based on wheat or corn, so from birth lambs were in contact with only one type of cereal. After weaning, lambs on each group were housed and fed together until the end of fattening (∼24 weeks). Three weeks before slaughter, lambs were housed in individual pens for in vivo methane production and digestion measurements. Through the whole experimental period, animals were fed twice daily at 0800 h and 1300 h. Diets contained 550 g of cereal grain completed with 700 g of barley hay and 10 g of bicarbonate. Ingredients and chemical composition of the experimental diets as fed are presented in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Intake, total tract digestibility, and in vivo methane production.

For practical reasons, animals were separated into two experimental groups, each one composed of 3 corn-fed and 3 wheat-fed lambs having similar live weights. There was a 3-week period between measurements of intake, digestibility, and methane production in each experimental group; also, lambs in the first group were slaughtered 3 weeks before those in the second one.

Intake, total tract digestibility, and daily methane production were measured during a 5-day period at the end of fattening while the lambs were in individual pens. Feed intake and orts were measured and recorded daily during the sample collection period to calculate dry matter intake (DMI). Total tract digestibility was determined from the total collection of feces during the measurement period. Fecal samples were weighed and mixed before a 10% aliquot was sampled. Feed and fecal samples from the 5 days were pooled by animal; one aliquot was used for dry matter determination (103°C for 24 h) and another for chemical analysis as previously reported (10). The neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF) contents were determined by sequential procedures after pretreatment with amylase and were expressed inclusive of residual ash (11). A polarimetric method was used for starch quantification (12).

Methane production was determined using the sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) tracer technique (13), as described by Martin et al. (10). A calibrated permeation tube was introduced into the rumen of each lamb through the mouth. Mean permeation rates of SF6 from the brass permeation tubes were 703 ± 128 ng/min. Background concentrations of methane and SF6 were also measured on ambient air samples collected every day in the barn during the sampling period. Gas samples were analyzed by gas chromatography as described elsewhere (10).

Rumen content sampling for fermentation and microbial parameters.

Lambs were slaughtered at INRA-Theix's experimental abattoir at an average age of 171 ± 5.7 days and average body weight of 28.2 ± 0.94 kg. Lambs were last fed the morning of the day before slaughter. The entire gastrointestinal tract was removed as soon as possible after slaughter, and representative samples of homogenized ruminal and cecal contents were collected and weighed along with whole ruminal and cecal contents. Rumen pH was measured with a portable pH meter (CG840, electrode Ag/AgCl; Schott Geräte, Hofheim, Germany) at 5 locations immediately after opening the rumen. Cecum pH was measured only on the liquid phase. Aliquots of ruminal (∼250-g) and cecal (∼50-g) contents were strained through polyester monofilament fabric (250-μm-mesh aperture) to separate the liquid phase. For VFA analysis, ruminal and cecal filtrates were sampled as already described (14). VFA were analyzed by gas chromatography (15) using crotonic acid as the internal standard on a CP 9002 gas chromatograph (Chrompack, Middelburg, Germany). For enumeration of protozoa, rumen fluid was mixed with MFS solution (35 ml/liter formaldehyde, 0.14 M NaCl, 0.92 mM methyl green) and stored in the dark at room temperature until microscope counting was performed as already described (16).

Another aliquot of ruminal and cecal contents (∼30 g each) was diluted with 15 ml ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 6.8) and homogenized, for three 1-min cycles with 1-min intervals on ice, using a Polytron grinding mill (Kinematica GmbH, Steinhofhalde, Switzerland). Approximately 0.5 g was transferred to a 2-ml Eppendorf tube and mixed with 1 ml of RNALater tissue collection RNA stabilization solution (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX). Tubes were kept at 4°C overnight to allow the solution to thoroughly penetrate the cells, as suggested by the manufacturer, and stored at −80°C until molecular analyses were performed.

Rumen and cecum content sampling for ex situ and in vitro fermentations.

Total ruminal and cecal contents, as well as corresponding strained fluids, were used as the inoculum for ex situ and in vitro incubations, respectively. Ex situ fermentations were performed to measure the methanogenic potential of gastrointestinal contents. For that, 100-ml serum vials containing 30 ml of anaerobic buffer solution (17), kept at 39°C under an O2-free CO2 gas headspace, were inoculated with 30 g of total ruminal or cecal contents from each animal in duplicate. For in vitro fermentations, vials contained buffer as described above and 0.5 g of ground corn or wheat as the substrate. These vials were inoculated with 15 ml of strained rumen or cecum fluid (one sample per animal) in order to assess their capacity to ferment the starchy feed substrates. Vials were capped with butyl rubber stoppers and incubated at 39°C for 24 h. Vials without inoculum were used as a negative control. Gas production was measured at 6 h and 24 h of incubation with the aid of a pressure transducer, and samples were collected for analysis of constituents by gas chromatograph (Micro GC 3000A; Agilent Technologies, France). At the end of incubation, vials were opened, pH was measured, and samples for VFA analysis were taken as described above.

tNA extraction and cDNA synthesis.

Total nucleic acids (tNA) were extracted as described by Popova et al. (18). Each tNA sample was divided into two equal fractions; DNA in one of the fractions was digested with DNase provided in a total RNA isolation kit (Machenery-Nagel, France) using a modified protocol (18).

The yield and the purity of the extracted tNA and RNA samples were assessed by optical density measurements using a NanoQuant Plate on an Infinity spectrophotometer (Tecan, Switzerland). RNA integrity was estimated with an Agilent RNA 6000 Nano kit on an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Results were analyzed using 2100 Expert software, version B.02.07.SI482 (Beta) (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). Indicators of RNA integrity were the RNA integrity number (RIN; maximum value, 10), the 23S rRNA/16S rRNA ratio (optimum value, 2), and the absence of degradation (low baseline) (19). Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed in cDNA using random primers (Promega, Madison, WI) (0.5 μg/μg RNA), as described by Popova et al. (16).

Microbial community quantification and gene expression.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out using a StepOne system (Applied Biosystems, Courtabeuf, France). Assays were performed in triplicate using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan) and used 20 ng of tNA or 2 μl of total cDNA. Negative controls without DNA template were run with every assay to assess overall specificity.

Primers used to quantify mcrA and rrs DNA or cDNA and reaction setup and temperature cycles were as described by Popova et al. (16). The amplification efficiency, slope, and R2 of qPCR assays targeting the mcrA gene were 91.8%, −3.53, and 0.999, respectively. The amplification efficiency, slope, and R2 of qPCR assays targeting the rrs gene were 95%, −3.35, and 0.999, respectively.

Absolute quantification involved the use of standard curves that had been prepared with PCR products corresponding to a partial sequence of the mcrA gene of Methanobrevibacter ruminantium DSM 1093 and almost the entire sequence of the rrs gene of Prevotella bryantii B14 (DSM 11371). Standard curves were created using triplicate, 10-fold dilutions series ranging from 2.5 × 102 to 2.5 × 108 copies for the mcrA gene and from 1 × 102 to 1 × 108 copies for the bacterial rrs gene. Gene copies in ruminal and cecal content samples were quantified, and results were expressed as numbers of gene copies per g dry matter (DM) of content or numbers of gene copies in total ruminal or cecal DM contents.

Expression of the functional mcrA gene was assessed using relative quantification by the threshold cycle (CT) of the qPCR. Levels of expression of the mcrA gene were compared in animals fed different diets using the ΔCT (see below) and 2−ΔCT values (20) for the corn and wheat diets. Fold change in mcrA gene expression in the contents of the cecum compared to the contents of the rumen of the same animal was computed using the 2−ΔΔCT method as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Statistical analysis of gene expression was done on the ΔCT and 2−ΔCT values as indicated by Schmittgen and Livak (20).

Microbial diversity analysis by PCR-DGGE.

The mcrA and rrs genes were used as molecular markers to assess, respectively, methanogen and bacterial diversity by PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (PCR-DGGE). For PCR amplification, 50 ng of total nucleic acids and 5 μl of cDNA samples were used. PCR amplifications and DGGE analysis were performed as described before (16).

Images of DGGE gels were acquired using an calibrated optical-density scanner (Epson, France) at a spatial resolution of 600 dots per inch (dpi). Images were analyzed with GelCompar II version 4.0 (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). Banding profiles were quantified within each profile by determining the total number of bands, the peak surface of each band, and the sum of all the peak surfaces of all bands (21). This was used to calculate the community biodiversity using three indices, the Shannon index, the dominance index, and the evenness index, according to Fromin et al. (21). To normalize for differences among gels, mcrA or rrs PCR products of a sample taken from a wether outside the study were run on every gel and used as standards for comparisons of gels. The similarities of standards between gels were 88% for the mcrA gene and 91% for the bacterial rrs gene.

DGGE profiles were compared using hierarchical clustering to join similar profiles into groups (21). To this end, all images of DGGE gels were matched using the standards and bands were quantified after local-background subtraction. A tolerance in the band position of 1% was applied. The similarity among profiles was calculated with the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the clustering was done with the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA).

Clone library construction, sequencing, and analysis of nucleotide sequences.

Methanogen mcrA gene libraries were constructed by cloning PCR-amplified products from tNA samples pooled by digestive compartment (rumen or cecum) and diet (corn or wheat). Four clone libraries (rumen-corn [RC], rumen-wheat [RW], cecum-corn [CC], and cecum-wheat [CW]) were created using pGEM-T Easy Vector System II (Promega, Madison, WI), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Clone libraries were sent to LGC Genomics GmbH (Germany) sequencing services for plasmid purification and DNA sequencing using the M13 forward primer.

Twenty-one completed genomes of methanogenic Archaea were retrieved from the NCBI genome database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/genome; accessed 22 September 2011). Strains belonged to all six known orders of methanogens, representing a total of 8 families. There were 56 sequences corresponding to rrs (average length, 1,468 bp) and 21 sequences corresponding to mcrA and MCR (methyl coenzyme M reductase alpha subunit) (average lengths, 1,673 bp and 557 amino acids). mcrA sequences were truncated to a fragment limited by a pair of widely used primers (22) (named mcrA-Luton); this DNA fragment was in silico translated to MCR-Luton amino acid sequences. Muscle (23) implemented in the SeaView version 4 program (24) was used to align rrs, mcrA-Luton, and MCR-Luton fragments. MEGA 5 (25) was used to compute distance matrixes for both mcrA-Luton sequences (using the Kimura 2-parameter algorithm) and MCR-Luton sequences (using the Dayhoff model). We used different species cutoff limits (unique and from 0.01 to 0.06) for rrs in MOTHUR and confirmed for this data set that 0.02 (98% similarity) was the best-adapted value to define archaeal species as previously reported (26). Pairwise comparisons of mcrA-Luton and MCR-Luton fragments and rrs sequences were performed to calculate the nucleotide or amino acid difference and then the percent sequence identity. The similarities of the 21 mcrA-Luton, MCR-Luton, and rrs sequences were linearly correlated and used to define distance cutoff values for methanogenic species-level operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The 0.02 species cutoff value based on the rrs gene corresponded with cutoff values of 0.13 (i.e., 87% identity) (R2 = 0.79) and 0.06 (i.e., 94% identity) (R2 = 0.79) for mcrA-Luton and MCR-Luton, respectively.

Sequences obtained in this study were compared with entries in the GenBank nr (nonredundant) database using BLASTn. Chimeras were identified using Bellerophon (27). After elimination of nonmethanogen and chimeric sequences, there were 68, 83, 77, and 71 sequences in the RW, RC, CW, and CC clone libraries, respectively. Sequences were aligned with Muscle (23) implemented in the SeaView version 4 program (24), and evolutionary distance matrices were calculated according to the Kimura 2-parameter algorithm implemented in MEGA 5 (25). Sequences were assigned to OTUs on the basis of 87% (mcrA) sequence identity using the furthest-neighbor algorithm in mothur v.1.21.1 (28). Rarefaction curves were constructed to check the sampling effort. Community structures of the libraries were compared using the libshuff command of mothur. For phylogenetic reconstruction, representative sequences, one from each OTU, were combined with mcrA sequences retrieved from GenBank representing major archaeal phylogenetic groups. Sequences were aligned with Muscle (23), and phylogenetic trees were constructed in MEGA 5 (25) using the neighbor-joining method; trees were bootstrap reassembled 1,000 times.

Calculations and statistical analysis.

Hydrogen recoveries for the ex situ and in vitro assays of both rumen and cecum inocula (total contents without substrate and strained fluids with substrate) were calculated as described by Demeyer et al. (29).

All data were analyzed using PROC MIXED of SAS version 9.1.2 (30). To determine effects on intake, total tract digestion, counts of protozoa, and in vivo methane output, the model included the diet (D) and experimental group (EG) as fixed effects with animal within diet as a random effect. The EG effect was not significant, so it is not presented here. The model for statistical analysis of fermentation parameters, molecular quantification data, and data from ex situ incubations of total contents included the diet (D) and fermentative compartment (FC) and their interaction (D × FC) as fixed effects with animal within diet as a random effect. For data from in vitro incubations of strained fluids, the model included the D, FC, and substrate (S) and their interactions (D × FC, D × S, FC × S, and D × FC × S) as fixed effects with animal within diet as a random effect. In the latter case, interactions were not significant and they are not presented in this paper. Effects were declared significant at P ≤ 0.05 and trends were declared for P ≤ 0.10.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences from this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers JX488056 to JX488138 and JX894252 to JX894470.

RESULTS

Dry matter intake, total tract digestibility, and methane output.

Diet had no effect on intake or total tract digestion of DM, NDF, and starch (P > 0.05; data not shown). Mean daily weight gains were similar between the two diets (0.19 kg/day for corn versus 0.17 kg/day for wheat diet, P > 0.05). In contrast, lambs fed the corn-based diet had lower daily methane emissions (CH4 g/day) and methane yield (CH4 g/kg DMI) (36% [P < 0.05] and 21% [P < 0.05], respectively) than wheat-fed animals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Methane output from lambs fed wheat- or corn-based dietsa

| Parameter | Methane output for indicated diet |

SEM | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Corn | |||

| g/day | 12.84 | 8.19 | 1.254 | <0.05 |

| g/kg DM intake | 15.17 | 11.97 | 0.763 | <0.05 |

| g/kg NDF intake | 41.16 | 32.93 | 4.212 | NS |

| g/kg starch intake | 31.56 | 25.32 | 2.852 | NS |

| g/kg digested DM | 25.28 | 20.92 | 1.683 | 0.10 |

| g/kg digested NDF | 101.16 | 108.29 | 23.730 | NS |

| g/kg digested starch | 35.84 | 27.78 | 3.370 | NS |

Values represent means of the results determined with 6 lambs.

NS, not significant.

In vivo fermentation patterns.

The ruminal and cecal contents of corn-fed lambs were, respectively, 1.4-fold heavier (P < 0.01) and 1.6-fold lighter (P < 0.01) than the corresponding contents of wheat-fed lambs (Table 2). Irrespective of the diet, the VFA concentration in the cecum was about 30% of that found in the rumen but with a higher proportion of acetate (P < 0.01).

Table 2.

Characteristics of digestive contents and in vivo fermentation parameters in lambs fed wheat- or corn-based dietsa

| Parameter | Value for indicated dietb |

SEM |

P valuec |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat |

Corn |

|||||||

| Rumen | Cecum | Rumen | Cecum | D | FC | D × FC | ||

| Digestive content | ||||||||

| Total wet wt (g) | 3,023.30a | 430.45b | 3,921.70a | 273.33c | 20.336 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Total dry wt (g) | 423.24a | 76.13b | 622.23c | 55.14b | 45.105 | 0.087 | <0.01 | <0.05 |

| Dry matter (%) | 14.00 | 17.80 | 15.85 | 20.67 | 1.147 | NS | <0.01 | NS |

| Fermentation | ||||||||

| pH | 6.66 | 6.79 | 6.68 | 6.52 | 0.088 | NS | NS | NS |

| Total VFA (mM) | 66.91 | 46.91 | 68.64 | 57.68 | 4.997 | NS | <0.01 | NS |

| Acetate (%)d | 69a | 78b | 68a | 76b | 15.2 | NS | <0.01 | NS |

| Propionate (%)d | 17 | 16 | 19 | 13 | 1.6 | NS | 0.06 | 0.10 |

| Butyrate (%)d | 12a | 1b | 8a | 10a | 14.1 | NS | <0.05 | <0.01 |

| Minor VFA (%)d,e | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0.3 | NS | <0.01 | NS |

| Acetate/propionate ratio | 4.43 | 5.03 | 3.75 | 7.12 | 0.851 | NS | NS | NS |

Values represent means of the results determined with 6 lambs.

Different letters (a, b, and c) within the same row indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

D, diet; FC, fermentative compartment (rumen or cecum); D × FC, interaction between diet and fermentative compartment; NS, not significant.

Data represent % mM of individual VFA per mM of total VFA produced.

Minor VFA are valerate, isovalerate, isobutyrate, and caproate.

Ex situ and in vitro fermentation patterns.

Diet did not influence ex situ fermentation potential, with the exception of total gas, which tended to be higher (P = 0.101) in digestive contents from corn-fed lambs (Table 3). The main differences were observed between compartments, with cecal contents producing ∼4-fold less methane and ∼20% less VFA (P < 0.01) than equal volumes of ruminal contents. The hydrogen recovery was also significantly lower with cecum inoculates (P < 0.01).

Table 3.

Ex situ methanogenic and fermentative potential of total rumen and cecal contents from lambs receiving wheat- or corn-based dietsa

| Parameter | Diet |

SEM |

P valueb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat |

Corn |

||||||

| Rumen | Cecum | Rumen | Cecum | D | FC | ||

| Gas production at 6 h of incubation | |||||||

| Total (μmol/h) | 288.53 | 272.69 | 343.61 | 309.36 | 26.703 | 0.101 | NS |

| Methane (μmol/h) | 36.64 | 6.89 | 33.30 | 6.93 | 3.379 | NS | <0.01 |

| Methane (%)c | 11.18 | 4.09 | 9.68 | 3.16 | 0.0001 | NS | <0.01 |

| Gas production at 24 h of incubation | |||||||

| Total (μmol/h) | 146.44 | 154.30 | 188.25 | 164.54 | 12.155 | <0.05 | NS |

| Methane (μmol/h) | 28.03 | 7.43 | 26.46 | 6.39 | 2.71 | NS | <0.01 |

| Methane (%)c | 14.86 | 6.77 | 13.63 | 5.54 | 0.673 | NS | <0.01 |

| Hydrogen recovery (%) | 73.45 | 56.72 | 77.71 | 47.85 | 4.510 | NS | <0.01 |

| VFA production at 24 h of incubation | |||||||

| Total (mM) | 110.84 | 91.15 | 115.83 | 88.49 | 6.697 | NS | <0.01 |

| Acetate (%)d | 61.10 | 64.00 | 61.00 | 61.00 | 1.928 | NS | NS |

| Propionate (%)d | 20.75 | 21.75 | 23.00 | 25.33 | 2.119 | NS | NS |

| Butyrate (%)d | 11.50 | 9.56 | 10.50 | 10.00 | 1.486 | NS | NS |

| Acetate/propionate ratio | 3.03 | 3.43 | 2.66 | 2.49 | 0.543 | NS | NS |

| Minor VFA (%)d,e | 6.34 | 4.89 | 5.50 | 4.00 | 0.518 | NS | <0.05 |

| pH | 5.89 | 6.03 | 5.56 | 5.79 | 0.138 | NS | NS |

Values represent the means of the results of 12 observations.

D, diet; FC, fermentative compartment. The D × FC interaction was never significant (P > 0.05). NS, not significant.

μmol of CH4 per μmol of total gas produced.

% mM of individual VFA per mM of total VFA produced.

Minor VFA are valerate, isovalerate, isobutyrate, and caproate.

The capacity of ruminal and cecal strained fluids to degrade readily fermentable substrate in vitro is summarized in Table 4. Methane production (μmol/h) was higher (P < 0.01) with strained ruminal or cecal fluids from wheat-fed lambs than with that from corn-fed lambs. Incubation of cecal contents always yielded less methane and a poorer hydrogen recovery than incubation of ruminal contents (P < 0.01). Similar to the methane results, total VFA concentrations were lower (P < 0.01) in vials inoculated with inocula from corn-fed lambs (Table 4). Acetate molar proportion was higher (P < 0.05) in cecal than in ruminal contents.

Table 4.

Capacity of strained rumen and cecum liquids from lambs fed wheat- or corn-based diets to degrade readily fermentable substrates in vitroa

| Parameter | Value for indicated diet and substrate |

SEM |

P valueb |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat |

Corn |

|||||||||||

| Rumen |

Cecum |

Rumen |

Cecum |

|||||||||

| Wheat | Corn | Wheat | Corn | Wheat | Corn | Wheat | Corn | D | FC | S | ||

| Gas production at 6 h of incubation | ||||||||||||

| Total (μmol/h) | 440.40 | 357.05 | 382.55 | 302.66 | 367.64 | 264.83 | 379.96 | 279.24 | 45.872 | NS | NS | <0.01 |

| Methane (μmol/h) | 49.75 | 37.82 | 25.90 | 19.52 | 36.00 | 23.57 | 9.03 | 6.61 | 5.344 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.05 |

| Methane (%)c | 11.18 | 10.46 | 6.28 | 6.10 | 9.47 | 8.43 | 2.60 | 2.40 | 0.873 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.05 |

| Gas production at 24 h of incubation | ||||||||||||

| Total (μmol/h) | 548.47 | 493.79 | 465.47 | 398.28 | 485.38 | 397.97 | 458.20 | 378.63 | 40.417 | NS | = 0.06 | <0.05 |

| Methane (μmol/h) | 660.60 | 645.18 | 315.22 | 322.35 | 567.47 | 498.07 | 156.25 | 164.74 | 55.042 | <0.05 | <0.01 | NS |

| Methane (%)c | 13.33 | 13.12 | 7.62 | 8.11 | 12.28 | 11.73 | 4.92 | 5.44 | 0.001 | 0.06 | <0.01 | NS |

| Hydrogen recovery (%) | 68.11 | 74.10 | 50.43 | 53.24 | 72.57 | 70.66 | 45.36 | 47.67 | 3.500 | NS | <0.01 | 0.101 |

| VFA production at 24 h of incubation | ||||||||||||

| Total (mM) | 122.18 | 119.47 | 118.48 | 111.03 | 96.96 | 104.12 | 96.47 | 86.59 | 5.205 | <0.01 | NS | NS |

| Acetate (%)d | 58.04 | 54.17 | 63.10 | 60.48 | 58.90 | 53.03 | 59.75 | 59.30 | 7.455 | NS | <0.05 | <0.01 |

| Propionate (%)d | 23.10 | 25.18 | 17.17 | 16.84 | 21.37 | 22.07 | 25.20 | 24.95 | 7.59 | NS | NS | NS |

| Butyrate (%)d | 13.70 | 15.04 | 15.26 | 17.34 | 13.63 | 19.30 | 11.25 | 11.65 | 9.85 | NS | NS | <0.01 |

| Acetate/butyrate ratio | 2.76 | 2.30 | 4.72 | 4.09 | 2.97 | 2.50 | 2.38 | 2.38 | 0.642 | NS | NS | NS |

| Minor VFA (%)d,e | 6.21 | 6.70 | 5.39 | 5.88 | 5.94 | 5.91 | 3.63 | 3.55 | 1.124 | NS | NS | NS |

Values represent the means of the results of 6 observations.

D, diet; FC, fermentative compartment; S, substrate. The double and triple interactions between D, FC. and S were never significant (P> 0.05). NS, not significant.

μmol of CH4 per μmol of total gas produced.

% mM of individual VFA per mM of total VFA produced.

Minor VFA are valerate, isovalerate, isobutyrate, and caproate.

Microbial community structure.

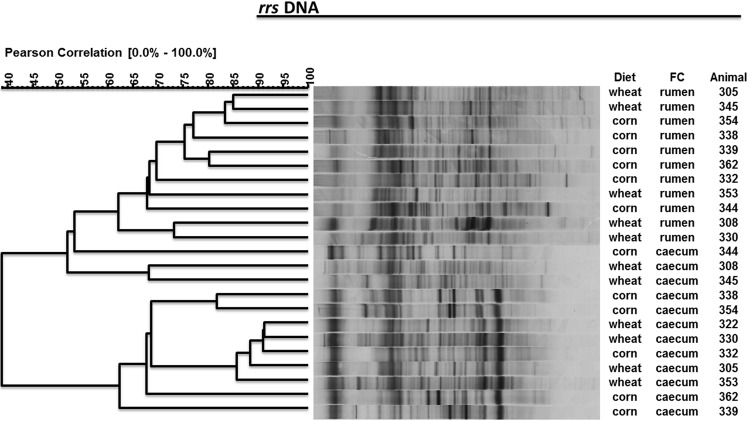

Total protozoal numbers tended to increase (P = 0.06) in wheat-fed lambs compared to lambs fed the corn diet (Table 5). Vestibuliferida (Isotricha and Dasytricha) increased with wheat. Bacterial numbers (rrs copy numbers) were similar (P > 0.05) in the rumens of wheat- and corn-fed lambs and were higher (P < 0.05) in the cecum of wheat-fed lambs than in the cecum of corn-fed lambs (Table 5). Diet did not induce changes in the bacterial community diversity as measured using PCR-DGGE. In contrast, PCR-DGGE analysis partially separated rumen and cecum samples (Fig. 1). Cecum samples grouped more closely than did rumen samples. The Shannon index, the dominance index, and the evenness index values were similar between diets and digestive compartments (data not shown).

Table 5.

Counts of protozoa and absolute and relative qPCR quantification resultsa

| Parameter | Value for indicated dietb |

SEM |

P valuec |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat |

Corn |

|||||||

| Rumen | Cecum | Rumen | Cecum | D | FC | D × FC | ||

| Total protozoa (log cells/ml) | 5.89 | /d | 5.55 | / | 0.108 | 0.06 | / | / |

| Small (<100-μm) entodiniomorphs (log cells/ml) | 5.89 | / | 5.54 | / | 0.102 | <0.05 | / | / |

| Large (>100-μm) entodiniomorphs (log cells/ml) | 3.84 | / | 3.44 | / | 0.263 | NS | / | / |

| Dasytricha (log cells/ml) | 3.93 | / | 2.72 | / | 0.146 | <0.01 | / | / |

| Isotricha (log cells/ml) | 4.25 | / | 2.81 | / | 0.187 | <0.01 | / | / |

| Gene quantification | ||||||||

| mcrA (log copies/g DM) | 8.81 | 8.34 | 8.46 | 7.66 | 0.088 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.08 |

| rrs (log copies/g DM) | 12.10a | 12.18a | 12.04a | 11.77b | 0.078 | <0.05 | NS | <0.05 |

| mcrA (log total no.) | 11.41a | 10.20b | 11.26a | 9.40c | 0.095 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.05 |

| rrs (log total no.) | 14.70a | 14.06b | 14.82a | 13.51c | 0.074 | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| mcrA/rrs (× 10−2) | 5.16a | 1.42b | 2.89c | 0.80b | 2.3 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.05 |

| mcrA gene expression | ||||||||

| ΔCT | 10.45 | 12.79 | 11.21 | 12.01 | 0.874 | NS | <0.05 | NS |

| 2−ΔCT (× 10−5) | 11.1 | 4.40 | 17.1 | 9.30 | 5.55 | NS | NS | NS |

Values represent the means of the results determined with 6 lambs.

Values with different letters (a, b, and c) in the same row are significantly different.

D, diet; FC, fermentative compartment; D × FC, interaction between diet and fermentative compartment; NS, not significant.

/, the population of protozoa was not counted in the cecal contents.

Fig 1.

PCR-DGGE profiles of rrs DNA sequences of rumen bacteria from two fermentative compartments (FC) of lambs (animal numbers shown) fed a wheat- or corn-based diet. The similarity among profiles was calculated with the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the clustering was done with the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA).

Methanogens (mcrA copies), as for protozoa, were higher (P < 0.01) in digestive contents of animals fed wheat relative to lambs fed corn. Whatever the diet, the concentration with respect to mcrA gene copy numbers (number of copies/g DM contents) and the total numbers of mcrA and rrs copies were higher (P < 0.01) in ruminal relative to cecal contents (Table 5).

The expression of the bacterial rrs gene remained constant in ruminal and cecal contents, as assessed by a Student's test on the rrs 2−CT values (data not shown), allowing us to use it as a calibrator for an mcrA expression study (31). The mcrA ΔCT values were higher (P < 0.05) in the cecum than in the rumen for both groups of animals. The mcrA 2−ΔCT values were also higher, but the difference was not significant (Table 5). Nonetheless, the 2−ΔCT values in cecal contents were 2 times higher in corn-fed lambs than in wheat-fed lambs. In addition, expression of the mcrA gene decreased by more than 2 times (2−ΔΔCT = −2.167) in the cecum of corn-fed lambs compared to their rumen. In wheat-fed lambs, mcrA expression in the cecum was 4 times lower than in the rumen (2−ΔΔCT = −4.091).

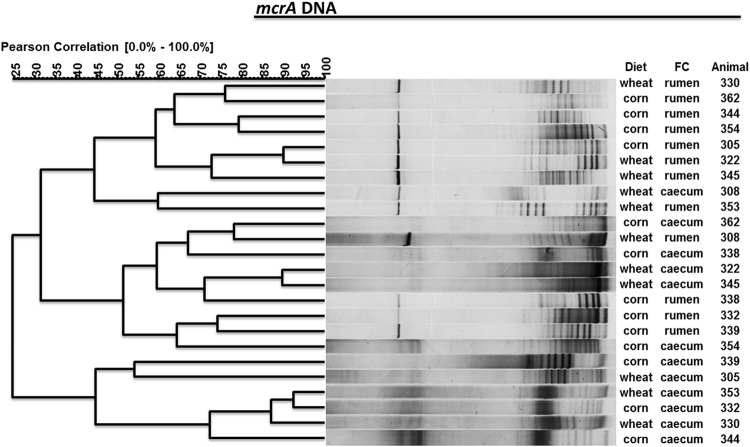

Cluster analysis of the mcrA DNA sequences from PCR-DGGE profiles partially separated the rumen from the cecum samples (Fig. 2). Three main clusters were formed, one grouping 7 rumen samples, another grouping 6 cecum samples, and the third formed with 4 rumen and 4 cecum samples. Although, within each cluster, samples tended to group by diet, the separation was not clear. Neither the number of bands nor any of the diversity indices calculated from the PCR-DGGE profiles presented significant differences related to diet or fermentative compartment (data not shown). However, several bands were uniquely found either in the ruminal or the cecal contents.

Fig 2.

PCR-DGGE profiles of mcrA DNA sequences of rumen methanogens from two fermentative compartments (FC) of lambs (animal numbers shown) fed a wheat- or corn-based diet. The similarity among profiles was calculated with the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient, and the clustering was done with the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA).

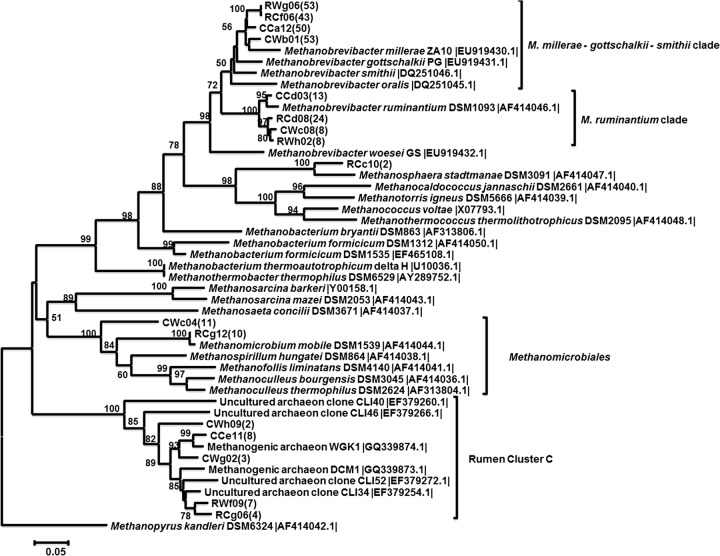

We constructed clone libraries of the mcrA gene to investigate the phylogeny of methanogenic Archaea in ruminal and cecal contents of wheat- and corn-fed lambs. Rarefaction curves for all four clone libraries tended to reach the horizontal asymptote for the 87% species cutoff value, which we calculated was equivalent to the 98% species cutoff value of the rrs gene. For higher cutoff values, the asymptote was not reached (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Pairwise comparisons by the libshuff test yielded significance values < 0.0043, attesting that our four sequence collections were all different. We used an 87% species cutoff value for mcrA sequences, and the 299 sequences used in this study grouped into 16 distinct OTUs. Clones were unevenly distributed between OTUs; the majority of the sequences from each library grouped into a single OTU closely related to the Methanobrevibacter millerae-M. gottschalkii-M. smithii clade (Fig. 3). Close relatives to the M. ruminantium clade represented, respectively, 29%, 12%, 18%, and 10% of the RC, RW, CC, and CW libraries. In contrast, members of the Methanomicrobiales order were detected only in CW and RC libraries (14% and 12% of the sequences, respectively). All four libraries contained sequences that clustered with uncultured archaeal clones belonging to rumen cluster C.

Fig 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of partial mcrA sequences derived from RW (rumen wheat), RC (rumen corn), CW (cecum wheat), and CC (cecum corn) clone libraries. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA 5. There were a total of 390 positions in the final data set. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor-joining method. The tree was bootstrap resampled 1,000 times; only bootstrap values > 50 are shown. The scale bar equals an average of 0.5 nucleotide substitutions per 100 positions. The GenBank accession numbers for reference nucleotide sequences are given between vertical bars. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of sequences grouped in the same OTU at 87% species cutoff. Methanopyrus kandleri was used as an outgroup to root the tree.

DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that readily degradable starch from wheat would reduce overall feed degradation in the rumen, increase organic matter arrival and fermentation in the cecum, and thus would induce changes in the two digestive microbiota. The aim of this study was to describe the ruminal and cecal microbiota, particularly, methanogenic Archaea, of growing lambs fed two contrasting diets in term of starch degradability. In order to link microbial community structure and function, we measured in vivo methane production and followed VFA patterns in the rumen and cecum. Ex situ and in vitro methane production was used to compare, respectively, methanogenic potential of ruminal and cecal contents and their capacity to degrade readily fermentable substrates.

Methanogenic Archaea are usually studied by targeting two main molecular markers—the rrs gene coding for the 16S rRNA and mcrA gene coding for a subunit of MCR (22), a crucial enzyme for the terminal step of methanogenesis (32). Targeting a gene which codes for an enzyme also offers the potential for development of activity-based detection methods by analysis of mRNA. Thus, molecular biology tools that target the mcrA gene in DNA and RNA extracts are useful to simultaneously highlight the diversity and activity of methanogens in different environments (16, 33).

Diet did not influence animal performances (intake, growth), but methane production and methane yield were higher in wheat-fed than in corn-fed lambs. Numbers of rumen protozoa tended to increase in the rumen of lambs fed the wheat diet, likely due to the greater amount of ruminal readily degradable starch (16, 34). Protozoal density is positively related to enteric methane emissions (reviewed in reference 35) and may help explain the higher methane produced with the wheat diet. In contrast, the concentration of methanogens in the rumen was not affected by diet. The lack of correlation between numbers of methanogens in the rumen and methane production was also observed with other mitigation strategies, such as removal of protozoa or lipid supply (reviewed in reference 35). A reduction in numbers of methanogens associated with methane reduction was instead reported with compounds toxic to methanogens (36, 37). When no changes in methanogen abundance are observed, higher methanogenesis could be attributed to increases in the metabolic activity of methanogens. A positive correlation between methanogenesis and mcrA gene expression has already been reported in vivo for beef cattle fed different high-grain-content diets (16) and in vitro with a tea saponin supplementation (11). In the current trial, 2−ΔCT values of ruminal contents of wheat-fed lambs were 1.5 times higher than 2−ΔCT values in corn-fed lambs. This difference was not statistically significant, but it should be noted that rumen contents were sampled at slaughter and that animals were last fed the morning of the day before slaughter. Methanogenic activity under these conditions would be at its lowest.

In our study, Methanobacteriales-related sequences were dominant in both the ruminal and the cecal contents. Methanobacteriales have been reported to be the predominant methanogens in the bovine (38, 39) and ovine (40) rumen. No dominant archaeal group has been identified in other sampling locations of the gastrointestinal tract in these ruminants (38). Clone library analysis suggested the presence of diet-induced changes of the methanogenic community composition in the rumen. The majority of the sequences from the RW library (78%) belonged to the M. millerae-M. gottschalkii-M. smithii clade. In addition, it should be noted that this library did not present sequences related to the Methanomicrobiales order. In contrast, the RC library had only 52% of the sequences belonging to the M. millerae-M. gottschalkii-M. smithii clade. The other half were distributed between the M. ruminantium clade, the order of Methanobacteriales, and rumen cluster C. On the other hand, it seems that diet had no effect on the composition of the community of methanogens in the cecum of growing lambs, as sequences from the CC and the CW library had similar phylogenetic distributions. However, Methanomicrobiales-like sequences were retrieved only in the CW library.

Finally, we observed no diet-induced changes in the rumen bacterial community structure: rrs copy concentrations and total numbers and rrs PCR-DGGE profiles from the rumens were similar in the two groups of animals. This is in accordance with the resemblances of VFA profiles between the rumens of corn- and wheat-fed lambs. It has to be noted that PCR-DGGE detects large changes in the community whereas subtle variations are unnoticed. The differences between diets observed in the proportions of methanogens might reflect variations in the availability of substrates for methanogenesis and also variations in the microbes producing them. For instance, increases in the rumen cluster C members might be due to a higher availability of methanol, a required substrate for this group (41).

We reported that cecal contents were 7 and 14 times lighter than ruminal contents in wheat- and corn-fed lambs, respectively. In consequence, concentrations of molecular markers (numbers of gene copies/g DM) as well as total numbers of the bacterial and methanogenic populations were also lower. This is consistent with a recent work reporting that microbial numbers are reduced by 8 orders of magnitude from the rumen, through the abomasum, and into the duodenum of lactating dairy cows (42). Interestingly, despite these differences in microbial concentrations between rumen and cecal contents, we did not observe any differences in their ex situ total gas production. However, the lower VFA concentrations and the lower methanogenic potential in the cecal contents suggested lower fermentation rates than in the ruminal contents. These observations are in accordance with the lower mean 2−ΔΔCT values, showing that mcrA expression was lower in the cecum of both groups of lambs than in their rumen.

In both ex situ and in vitro trials, we observed higher molar proportions of acetate with cecal than with ruminal inocula. The enhanced production of acetate may have been partly due to reductive acetogenesis. This hydrogen sink pathway of acetate production is an alternative to methanogenesis that was reported in the cecum (43). Lower values for hydrogen recoveries in the cecum (both for total contents and strained-fluid incubations) suggest that reductive acetogenesis was a substantial source of acetate in our cecal samples (43).

Because of the existence of reductive acetogenesis and the absence of hydrogen-producing protozoa in the cecum, we expected differences in the diversity of ruminal and cecal methanogenic Archaea community. Cluster analysis of DGGE profiles showed differences in methanogenic communities between fermentative compartments that were confirmed by comparisons of clone libraries using Libshuff. In another study, targeting the archaeal rrs gene, the richness index of the archaeal community in the rumen was significantly higher than in the feces (44). In the study of Romero-Pérez et al. (9), the sample type (rumen liquor or rectal fecal samples) had a larger effect on bacterial communities than diet. Also, the bacterial communities, assessed by capillary electrophoresis single-stranded conformation polymorphism profiles of rrs genes, showed different structures between the forestomach and fecal contents of cows (8). These observations could be explained by environmental conditions such as pH and the presence of oxygen but also by the source and amount of the substrate, which differ greatly between the rumen and cecum.

Conclusions.

Data presented here showed that the nature of dietary starch greatly influenced methane production by growing lambs. Differences in methane emissions between lambs fed corn- or wheat-based diet are probably due to differences in the ruminal digestion of substrates. However, effects of diet on the microbial ecosystem of the rumen and of the cecum were less obvious. Our study is among the first aiming to characterize methanogenic community structure (in terms of numbers and diversity) and activity in the two microbial fermentation compartments of the ruminant digestive tract. Our results suggest that several archaeal species would be better adapted to either the rumen or cecum environment. Further research using high-throughput sequencing would be required for detailed studies of this community. Also, the contribution of other microbial populations of the cecum to the nutrition and health of ruminants is seldom addressed but warrants further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff of the animal experimental facilities and the slaughterhouse of the INRA's Herbivores Research Unit for animal care, help in methane measurements, and sampling, as well as D. Graviou, G. Gentes, L. Genestoux, P. Savajols, and Y. Rochette for help in sample analysis.

M. Popova was the recipient of an INRA-Région Auvergne scholarship.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 December 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03115-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. O'Mara FP. 2011. The significance of livestock as a contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions today and in the near future. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 166:7–15 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murray RM, Bryant AM, Leng RA. 1976. Rates of production of methane in the rumen and large intestine of sheep. Br. J. Nutr. 36:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beauchemin KA, McAllister TA, McGinn SM. 2009. Dietary mitigation of enteric methane from cattle. CAB Rev. 4:1–18 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wright A-DG, Williams AJ, Winder B, Christophersen CT, Rodgers SL, Smith KD. 2004. Molecular diversity of rumen methanogens from sheep in western Australia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1263–1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wright ADG, Kennedy P, O'Neill CJ, Toovey AF, Popovski S, Rea SM, Pimm CL, Klein L. 2004. Reducing methane emissions in sheep by immunization against rumen methanogens. Vaccine 22:3976–3985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beauchemin KA, McGinn SM. 2005. Methane emissions from feedlot cattle fed barley or corn diets. J. Anim. Sci. 83:653–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martin C, Philippeau C, Michalet-Doreau B. 1999. Effect of wheat and corn variety on fiber digestion in beef steers fed high-grain diets. J. Anim. Sci. 77:2269–2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Michelland RJ, Monteils V, Zened A, Combes S, Cauquil L, Gidenne T, Hamelin J, Fortun-Lamothe L. 2009. Spatial and temporal variations of the bacterial community in the bovine digestive tract. J. Appl. Microbiol. 107:1642–1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Romero-Pérez GA, Ominski KH, McAllister TA, Krause DO. 2011. Effect of environmental factors and influence of rumen and hindgut biogeography on bacterial communities in steers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:258–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Martin C, Rouel J, Jouany JP, Doreau M, Chilliard Y. 2008. Methane output and diet digestibility in response to feeding dairy cows crude linseed, extruded linseed, or linseed oil. J. Anim. Sci. 86:2642–2650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Soest PJ, Robertson JB, Lewis BA. 1991. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 74:3583–3597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. AFNOR 1985. Dosage de l'amidon. Méthode polarimétrique, p 123–125 In Aliments des animaux. Méthodes d'analyses fran çaises et communautaires, 2nd ed Association Française de Normalisation, Paris, France [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson K, Huyler M, Westberg H, Lamb B, Zimmerman P. 1994. Measurement of methane emissions from ruminant livestock using a sulfur hexafluoride tracer technique. Environ. Sci. Technol. 28:359–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lettat A, Nozière P, Silberberg M, Morgavi DP, Berger C, Martin C. 2010. Experimental feed induction of ruminal lactic, propionic, or butyric acidosis in sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 88:3041–3046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morgavi DP, Boudra H, Jouany JP, Graviou D. 2003. Prevention of patulin toxicity on rumen microbial fermentation by SH-containing reducing agents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51:6906–6910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Popova M, Martin C, Eugène M, Mialon MM, Doreau M, Morgavi DP. 2011. Effect of fibre- and starch-rich finishing diets on methanogenic Archaea diversity and activity in the rumen of feedlot bulls. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 166:113–121 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goering HK, Van Soest PJ. 1970. Forage fiber analysis (apparatus, reagents, procedures, and some applications). U.S. Agricultural Research Service, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 18. Popova M, Martin C, Morgavi DP. 2010. Improved protocol for high-quality coextraction of DNA and RNA from rumen digesta. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 55:368–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schroeder A, Mueller O, Stocker S, Salowsky R, Leiber M, Gassmann M, Lightfoot S, Menzel W, Granzow M, Ragg T. 2006. The RIN: an RNA integrity number for assigning integrity values to RNA measurements. BMC Mol. Biol. 7:3 doi:10.1186/1471-2199-7-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative Ct method. Nat. Protoc. 3:1101–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fromin N, Hamelin J, Tarnawski S, Roesti D, Jourdain-Miserez K, Forestier N, Teyssier-Cuvelle S, Gillet F, Aragno M, Rossi P. 2002. Statistical analysis of denaturing gel electrophoresis (DGE) fingerprinting patterns. Environ. Microbiol. 4:634–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Luton PE, Wayne JM, Sharp RJ, Riley PW. 2002. The mcrA gene as an alternative to 16S rRNA in the phylogenetic analysis of methanogen populations in landfill. Microbiology 148:3521–3530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O. 2010. SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27:221–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wright A-DG, Northwood KS, Obispo NE. 2009. Rumen-like methanogens identified from the crop of the folivorous South American bird, the hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin). ISME J. 3:1120–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huber T, Faulkner G, Hugenholtz P. 2004. Bellerophon: a program to detect chimeric sequences in multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 20:2317–2319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, Van Horn DJ, Weber CF. 2009. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:7537–7541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Demeyer DI, Fiedler D, De Graeve KG. 1996. Attempted induction of reductive acetogenesis into the rumen fermentation in vitro. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 36:233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. SAS Institute, Inc 2003. Statistical analysis system, Windows version 9.1.2. SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC [Google Scholar]

- 31. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thauer RK. 1998. Biochemistry of methanogenesis: a tribute to Marjory Stephenson. 1998 Marjory Stephenson Prize Lecture. Microbiology 144(Pt 9):2377–2406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Freitag TE, Prosser JI. 2009. Correlation of methane production and functional gene transcriptional activity in a peat soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:6679–6687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mackie RI, Gilchrist FMC, Robberts AM, Hannah PE, Schwartz HM. 1978. Microbiological and chemical changes in the rumen during the stepwise adaptation of sheep to high concentrate diets. J. Agric. Sci. 90:241–254 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Morgavi DP, Forano E, Martin C, Newbold CJ. 2010. Microbial ecosystem and methanogenesis in ruminants. Animal 4:1024–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Denman SE, Tomkins NW, McSweeney CS. 2007. Quantitation and diversity analysis of ruminal methanogenic populations in response to the antimethanogenic compound bromochloromethane. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 62:313–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Knight T, Ronimus RS, Dey D, Tootill C, Naylor G, Evans P, Molano G, Smith A, Tavendale M, Pinares-Patiño CS, Clark H. 2011. Chloroform decreases rumen methanogenesis and methanogen populations without altering rumen function in cattle. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 166:101–112 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lin C, Raskin L, Stahl DA. 1997. Microbial community structure in gastrointestinal tracts of domestic animals: comparative analyses using rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 22:281–294 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhou M, Hernandez-Sanabria E, Guan LL. 2009. Assessment of the microbial ecology of ruminal methanogens in cattle with different feed efficiencies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:6524–6533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wright A-D, Ma X, Obispo N. 2008. Methanobrevibacter phylotypes are the dominant methanogens in sheep from Venezuela. Microb. Ecol. 56:390–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Paul K, Nonoh J, Mikulski L, Brune A. 2012. “Methanoplasmatales,” Thermoplasmatales-related archaea in termite guts and other environments, are the seventh order of methanogens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:8245–8253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Frey JC, Pell AN, Berthiaume R, Lapierre H, Lee S, Ha JK, Mendell JE, Angert ER. 2010. Comparative studies of microbial populations in the rumen, duodenum, ileum and faeces of lactating dairy cows. J. Appl. Microbiol. 108:1982–1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Demeyer D. 1991. Differences in stoichiometry between rumen and hindgut fermentation. Adv. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 22:50–61 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Michelland RJ, Monteils V, Combes S, Cauquil L, Gidenne T, Fortun-Lamothe L. 2010. Comparison of the archaeal community in the fermentative compartment and faeces of the cow and the rabbit. Anaerobe 16:396–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]