Abstract

10,11-Dehydrocurvularin is a prevalent fungal phytotoxin with heat shock response and immune-modulatory activities. It features a dihydroxyphenylacetic acid lactone polyketide framework with structural similarities to resorcylic acid lactones like radicicol or zearalenone. A genomic locus was identified from the dehydrocurvularin producer strain Aspergillus terreus AH-02-30-F7 to reveal genes encoding a pair of iterative polyketide synthases (A. terreus CURS1 [AtCURS1] and AtCURS2) that are predicted to collaborate in the biosynthesis of 10,11-dehydrocurvularin. Additional genes in this locus encode putative proteins that may be involved in the export of the compound from the cell and in the transcriptional regulation of the cluster. 10,11-Dehydrocurvularin biosynthesis was reconstituted in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by heterologous expression of the polyketide synthases. Bioinformatic analysis of the highly reducing polyketide synthase AtCURS1 and the nonreducing polyketide synthase AtCURS2 highlights crucial biosynthetic programming differences compared to similar synthases involved in resorcylic acid lactone biosynthesis. These differences lead to the synthesis of a predicted tetraketide starter unit that forms part of the 12-membered lactone ring of dehydrocurvularin, as opposed to the penta- or hexaketide starters in the 14-membered rings of resorcylic acid lactones. Tetraketide N-acetylcysteamine thioester analogues of the starter unit were shown to support the biosynthesis of dehydrocurvularin and its analogues, with yeast expressing AtCURS2 alone. Differential programming of the product template domain of the nonreducing polyketide synthase AtCURS2 results in an aldol condensation with a different regiospecificity than that of resorcylic acid lactones, yielding the dihydroxyphenylacetic acid scaffold characterized by an S-type cyclization pattern atypical for fungal polyketides.

INTRODUCTION

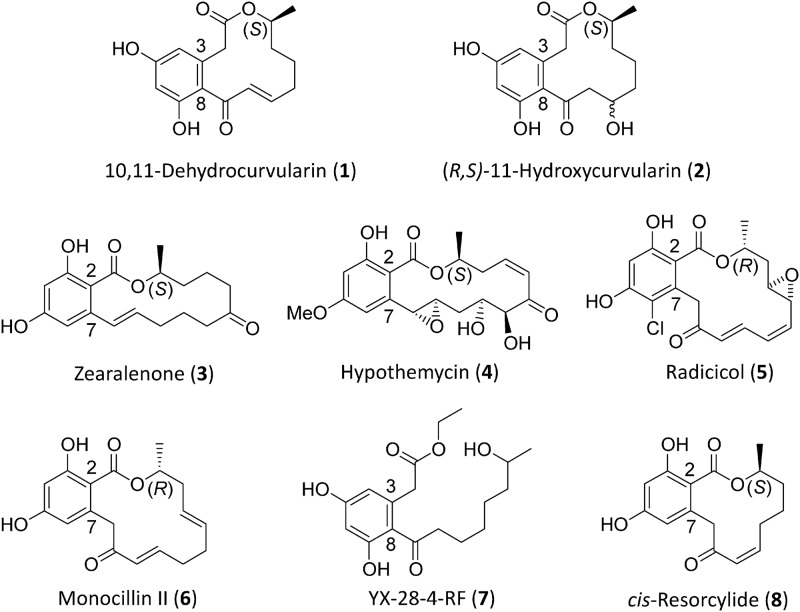

Curvularins are phytotoxic, antifungal, and cytotoxic polyketides frequently isolated from different ascomycete species including Alternaria, Aspergillus, Cochliobolus, Curvularia, and Penicillium spp. (1–6). Curvularins inhibit the expression of the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), thereby acting as anti-inflammatory agents and immune system modulators (7, 8). Importantly, 10,11-dehydrocurvularin (Fig. 1, compound 1) is a strong activator of the heat shock response, an evolutionarily conserved coping mechanism of eukaryotic cells that maintains protein homeostasis via the overexpression of heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) and various chaperones including heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) (9, 10). By overwhelming the heat shock response, 10,11-dehydrocurvularin acts as a broad-spectrum inhibitor of various cancer cell lines in vitro (11). Curvularins are dihydroxyphenylacetic acid lactones (DALs) with structural similarities to the better-known resorcylic acid lactones (RALs). Fungal RALs such as zearalenone (Fig. 1, compound 3), hypothemycin (compound 4), radicicol (compound 5), pochonin, and monocillin II (compound 6) are rich pharmacophores with estrogen agonist, mitogen-activated protein kinase-inhibitory, and heat shock response-modulatory activities (12, 13).

Fig 1.

Resorcylic acid and dihydroxyphenylacetic acid lactones and esters.

While most fungal polyketides are biosynthesized by single iterative polyketide synthase (iPKS) enzymes, the assembly of RALs requires two collaborating PKSs, as shown by cloning and characterization of the gene clusters for zearalenone (Fig. 1, compound 3), hypothemycin (compound 4), and radicicol (compound 5) (14–18). All fungal PKSs incorporate single ketoacyl synthase (KS), acyl transferase (AT), and acyl carrier protein (ACP) core domains that are used iteratively to build the carbon scaffold of the polyketide by recursive, decarboxylative Claisen condensations of malonyl-coenzyme A (CoA) precursors. Highly reducing fungal iPKSs (hrPKS) deploy ketoacyl reductase (KR), dehydratase (DH), and enoyl reductase (ER) domains that may reduce the nascent β-ketone in the growing polyketide chain to an alcohol, an alkene, or an alkane after each condensation step, following as yet cryptic programming rules (19, 20). For RAL biosynthesis, an hrPKS assembles a variably reduced linear polyketide chain. This advanced starter unit is transferred to the partner nonreducing PKS (nrPKS) by the starter AT (SAT) domain of the nrPKS (21) for further elongations without reduction. The product template (PT) domain of the nrPKS directs ring closure to yield the resorcinol carboxylate moiety by C-2–C-7 aldol condensation (22–24), while the thioesterase (TE) domain is responsible for the off-loading of the RAL from the nrPKS by closure of the bridging macrolactone ring (25). RAL synthesis has been characterized in the producer fungi by gene disruptions (14, 15, 17) and reconstituted both in vivo by heterologous expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and in vitro using isolated recombinant PKS enzymes (18, 26, 27).

Investigations into the biosynthesis of curvularins by incorporation of labeled precursors established the polyketide origins of the molecule (28) and identified the immediate product of the putative PKS system as 10,11-dehydrocurvularin (Fig. 1, compound 1). This polyketide occurs together with an epimeric mixture of 11-hydroxycurvularins (compound 2), formed as a result of the addition of water in potato dextrose broth medium (29). It was also shown that linear, reduced tetraketides and their N-acetylcysteamine thioester (SNAC) derivatives can be incorporated into curvularins (30, 31). However, in spite of the structural similarities of RALs and DALs, it has been unknown whether DAL biosynthesis also employs collaborating and sequentially acting hrPKS-nrPKS pairs in fungi and thus whether the “chemical modularity” principle that is operational in RALs could also be extended to these molecules. Even if this is the case, DALs show unique features whose biosynthesis requires significant departures from canonical RAL assembly. Most importantly, the dihydroxyphenylacetic acid ring is formed with a different regiospecificity: this C-8–C-3 aldol condensation is rarely featured in fungal polyketide products but is prevalent in bacterial aromatic polyketides (32). Second, dehydrocurvularin features a 12-membered macrocylic ring moiety as opposed to the 14-membered macrolactones of the RAL series studied to date.

Comprehensive understanding of the structural basis of DAL biosynthesis requires the characterization of the corresponding biosynthetic gene cluster. In this work, we have cloned and sequenced the 10,11-dehydrocurvularin biosynthetic locus from Aspergillus terreus AH-02-30-F7, a producer of dehydrocurvularin (Fig. 1, compound 1), that had been isolated from the rhizosphere of a Brickellia sp. in the Sonoran desert (2). We reconstituted the production of 10,11-dehydrocurvularin (compound 1) and its derivative 11-hydroxycurvularin (compound 2) in yeast by heterologous expression of the collaborating hrPKS-nrPKS gene pair. We also reconstituted the biosynthesis of dehydrocurvularin and its analogues in recombinant yeast using SNAC mimics of the proposed product of the hrPKS, thereby substantiating our predictions on the division of labor between the dehydrocurvularin-collaborating iPKS enzymes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

Aspergillus terreus AH-02-30-F7 (2) was maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA; Difco) at 28°C. Escherichia coli DH10B and plasmid pJET1 (Fermentas) were used for routine cloning and sequencing, while E. coli Epi300 and fosmid pCCFOS1 (Epicentre) were utilized for genomic library construction. Saccharomyces cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA (MATα ura3-52 his3-Δ200 leu2-Δ1 trp1 pep4::HIS3 prb1 Δ1.6R can1 GAL) (33, 34) was maintained on yeast extract-peptone-dextrose agar (YPD; Difco). The yeast-E. coli shuttle vector YEpADH2p with the URA3 or with the TRP1 selectable marker (27) was modified by inserting the DNA sequence 5′-TACACAATGGACTACAAAGACGATGACGACAAGCTTCATATGCGGGTTTAAACGGACATCACCATCACCATCACTGATTTAAAT-3′ between the NdeI-PmlI (YEpADH2p-URA3) and the NdeI-PmeI (YEpADH2p-TRP1) sites, yielding YEpADH2p-FLAG-URA and YEpADH2p-FLAG-TRP, respectively. Insertion of open reading frames into the NdeI-PmeI sites of these vectors fuses the Flag peptide (Asp-Tyr-Lys-Asp-Asp-Asp-Asp-Lys) to the N termini and the 6×His tag to the C termini of the expressed proteins.

Cloning, sequencing, and sequence analysis.

Novel degenerate primer pairs (Table 1) were designed against conserved regions of the zearalenone (GenBank accession numbers ABB90282 and ABB90283), hypothemycin (ACD39753 and ACD39758), and radicicol (Chaetomium chiversii, ACM42403 and ACM42406; Metacordyceps [Pochonia] chlamydosporia, ACD39770 and ACD39774) nrPKSs and hrPKSs, respectively, using the iCODEHOP algorithm (http://dbmi-icode-01.dbmi.pitt.edu/i-codehop-context/Welcome) and used to amplify KS- and AT-encoding regions of the corresponding genes from the chromosomal DNA of A. terreus AH-02-30-F7. PCR conditions were as follows: 30 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 46°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 120 s, followed by one cycle of 72°C for 300 s, using the EmeraldAmp GT PCR Mastermix from Clontech. Sequenced amplicons encoding iPKS regions showing >50% identity to RAL iPKSs were subsequently used as probes to screen a fosmid library of A. terreus AH-02-30-F7 raised in pCC1FOS (Epicentre). Hybridizing fosmids were clustered, and fosmids A. terreus P22 (AtP22), AtP05, and AtP30, each of which hybridized with both the hrPKS and nrPKS amplicons, were sequenced as described earlier (17). Hidden Markov model (HMM)-based gene models were built with FGENESH (Softberry) with additional exon/intron boundary refinements in SPLICEVIEW (http://zeus2.itb.cnr.it/∼webgene/wwwspliceview.html). The Udwary-Merski algorithm (UMA) was used to predict domain boundaries in PKSs (35), and the TMHMM server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) was utilized for the prediction of transmembrane helices. Multiple sequence alignments were generated in VectorNTI Advance, version 9.1 (Invitrogen). Bootstrapped trees were calculated in CLUSTALX with the neighbor-joining method using 1,000 repeats, and the phylogram was plotted as a radial tree with Phylodraw, version 0.8 (36).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for cloning the dehydrocurvularin PKS-encoding genes

| Name (restriction enzyme) | Sequence | Product (size in kb) |

|---|---|---|

| NR-HopC5-F | CTGAACATCCACGCCYTNCARCAYAC | nrPKS (1.4) |

| NR-HopI110-R | CTGGGTGCCGGTGCCRTGCATYTC | |

| NR-HopI52-F | CTCGGGAGGCCATGYTNATGGAYCC | nrPKS (1.0) |

| NR-HopK7-R | GCCGCCGGCGGCRTCRAARTT | |

| Red-HopB14-F | CGACGCCGCCTTCTTYAAYATHAC | hrPKS (1.1) |

| Red-HopD4-R | GCCGTTGGTGCCGCCCATNCCRAA | |

| Red-HopB1-F | GCCACCCAGTACGTGGARGCNCAYGG | hrPKS (1.2) |

| Red-HopH8-R | CAGCCCACGGCCATCATNCCNCC | |

| hrPKS-E1F (NdeI) | CATCATATGCCTTCTGCACAGCACAG | AtcurS1 exon 1 (0.2) |

| hrPKS-E1R | GATGTGGGGGAGTAGGCATCTTTGCCATTCTTCAGC | |

| hrPKS-E2F | ATGCCTACTCCCCCACATCAACG | AtcurS1 exon 2 (0.8) |

| hrPKS-E2R | TTCAAAAGACGGCATTGTCACACCCTGTGTGAAGCCATC | |

| hrPKS-E3F | TGACAATGCCGTCTTTTGAAGCAC | AtcurS1 exon 3 (0.1) |

| hrPKS-E3R | TCCGGCTTTGGTCCCGTGCCGTGTGCCTCGACGTATTG | |

| hrPKS-E4F | GGCACGGGGACCAAAGCCG | AtcurS1 exon 4 (0.1) |

| hrPKS-E4R | CGCTGATTCGAGATGGCCGATGTTAGGTTTGACACTTCCTAC | |

| hrPKS-E5F | ATGGGCCATCTCGAATCAGCG | AtcurS1 exon 5 (2.9) |

| hrPKS-E5R | TGGAGGTACAGACGGATCAGCTCGACGACCCGATCTTC | |

| hrPKS-E6F | CTGATCCGTCTGTACCTCCACAATAACCC | AtcurS1 exon 6 (3.3) |

| hrPKS-E6R (PmeI) | CATGTTTAAACCTAACCCTTTCGACCTGC | |

| nrPKS-E1F (NdeI) | CATCATATGGACTCCAACCGTCCTGC | AtcurS2 exon 1 (0.3) |

| nrPKS-E1R | TGGCTCGGCGCTGATGGTCTCTAGTAGAACCACGGCTC | |

| nrPKS-E2F | GACCATCAGCGCCGAGCCAC | AtcurS2 exon 2 (0.3) |

| nrPKS-E2R | CTTTTGGCAGATGGGACTCCCATGTCATTTTGGAATTG | |

| nrPKS-E3F | GGAGTCCCATCTGCCAAAAGAGCC | AtcurS2 exon 3 (1.6) |

| nrPKS-E3R | AGGGAAGACATTCCGGCCGCTGCTTCACTGTGGCCAAGATTG | |

| nrPKS-E4F | GCGGCCGGAATGTCTTCCCTG | AtcurS2 exon 4 (0.2) |

| nrPKS-E4R | AGTAAACATGCGTTGCCGCCCGCGGCATCGAAATTGTTG | |

| nrPKS-E5F (PmeI) | GGCGGCAACGCATGTTTACTCC | AtcurS2 exon 5 (3.9) |

| nrPKS-E5R | GGCGGCAACGCATGTTTACTCC |

Production of dehydrocurvularin and 11-hydroxycurvularin in yeast.

The exons of the A. terreus curS1 (AtcurS1) hrPKS and the AtcurS2 nrPKS genes were amplified separately using fosmid AtP05 as the template and the primers listed in Table 1, and the PCR products were fused by overlap extension PCR. After sequence verification, the resulting intronless AtcurS1 hrPKS was ligated to YEpADH2p-FLAG-TRP to yield YEpAtCURS1, while the intronless AtcurS2 nrPKS was inserted into YEpADH2p-FLAG-URA to generate plasmid YEpAtCURS2. S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA was transformed using the small-scale lithium chloride protocol (37). Yeast strains harboring expression plasmids were grown in SC medium (0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% glucose, 0.72g/liter of −Trp/−Ura DropOut supplement [Clontech]) at 30°C with shaking at 250 rpm until the cultures reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6; then an equal volume of YP medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone) was added to the cultures, and cultivation was continued for two additional days at 30°C with shaking at 250 rpm. The cultures were adjusted to pH 5.0 and extracted with equal volumes of ethyl acetate three times. The organic phases were pooled, the solvent was evaporated, and the resulting extract was analyzed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on an HP-1050 equipped with a Kromasil C18 column (5-μm particle size; 250 mm by 4.6 mm). HPLC conditions were the following: 5% CH3CN in H2O for 5 min, a linear 5 to 95% gradient of CH3CN in H2O over 10 min, and 95% CH3CN in H2O for 10 min; flow rate of 0.8 ml/min; detection at 300 nm. 10,11-Dehydrocurvularin and 11-hydroxycurvularin were isolated by collecting the appropriate HPLC fractions. One-dimensional (1D) and two-dimensional (2D) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded in CDCl3 or acetone-D6 (hexadeuteroacetone) on a Bruker Avance III instrument at 400 MHz for 1H NMR and 100 MHz for 13C NMR (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Feeding experiments.

S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA harboring both YEpADH2p-FLAG-TRP and YEpAtCURS2 was cultured in 20 ml of SC medium at 30°C with shaking at 250 rpm. When the OD600 reached 0.6, an equal volume of YP medium was added, and the culture was supplemented with 40 μl of the appropriate precursor stock solution (100 mg/ml in methanol). Cultivation was continued at 30°C with shaking at 250 rpm for an additional 2 days. The cultures were adjusted to pH 5.0 and extracted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc) three times. The extracts were evaporated to dryness and analyzed by reverse-phase HPLC as described above. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) data were collected on an Agilent 6130 Single Quad liquid chromatography (LC)-MS instrument. Compounds 1 and 2 obtained in feeding experiments were identified based on their HPLC retention times, UV spectra, and molecular weights compared to purified standards. Compound 7 was identified by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). Accurate mass measurement was performed with matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) on the sodiated molecular ion [M+Na]+ on a Bruker Ultraflex III MALDI two-stage time of flight (TOF-TOF) instrument. α-Cyanocinnamic acid (HCCA) was used as the matrix, and the matrix ions were used as internal standards for calibration. The MS/MS spectrum of the protonated compound 7 was obtained by generating the [M+H]+ ion by electrospray ionization (ESI) on a Thermoelectron LC quadrupole (LCQ) instrument. The sample was dissolved at a concentration of approximately 50 μM in a 1:1 mixture of acetonitrile and water that also contained 0.1% formic acid and sprayed under conventional ESI conditions with a flow rate of 8 μl/min. The MS/MS spectrum was obtained by colliding the [M+H]+ with He at a 27% collision energy (in arbitrary units).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the dehydrocurvularin locus has been submitted to GenBank under accession number JX971534.

RESULTS

Isolation of the dehydrocurvularin biosynthetic locus.

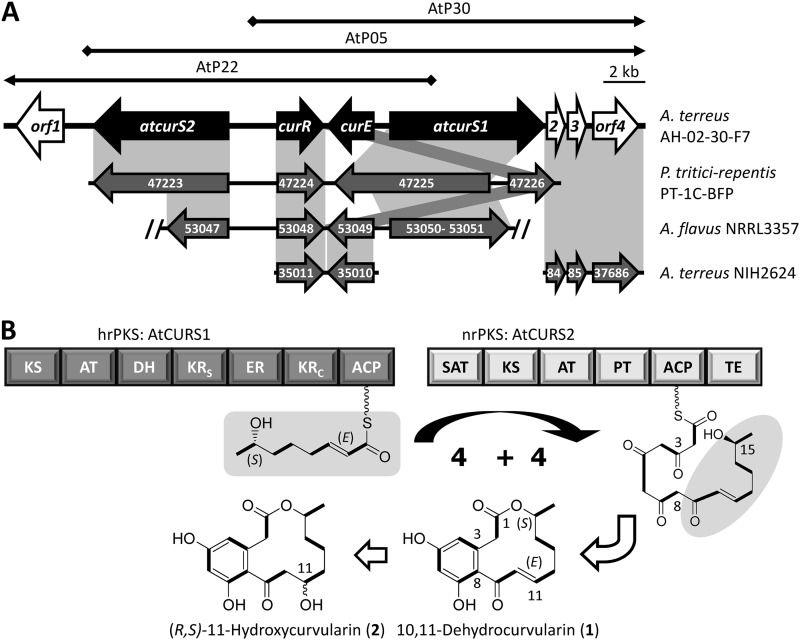

Since none of the fungi whose genome sequences have been publicly available during the course of this work were described in the literature to produce dehydrocurvularin, we settled upon a PCR-based strategy using degenerate primers to clone a dehydrocurvularin biosynthetic cluster. The structural similarities of DALs to fungal RALs led us to hypothesize that the biosynthesis of 10,11-dehydrocurvularin might involve collaborating iPKSs acting sequentially. Using the sequences of characterized RAL hrPKS-nrPKS pairs responsible for the biosynthesis of radicicol (from two different fungal species), hypothemycin, and zearalenol (14–18), we designed novel primer pairs (Table 1) that provided considerable specificity for amplifying collaborating fungal iterative PKS genes from fungal genomes. We have used these primer sets against A. terreus AH-02-30-F7, a producer of dehydrocurvularin (2). Most, although not all, of the amplified fragments turned out to represent a distinct nrPKS and a distinct hrPKS gene, each displaying >50% identity to the known RAL megasynthases. Sequencing of fosmids covering both the nrPKS and the hrPKS amplicons revealed a 31,000-bp genomic locus (Fig. 2A) encoding putative proteins for an hrPKS-nrPKS pair (AtCURS1-AtCURS2, respectively), a GAL4-like transcriptional regulator (AtCurR), and a major facilitator superfamily transporter (MFS; AtCurE), all with plausible functions in dehydrocurvularin biosynthesis (Table 2). These genes are bordered by open reading frames encoding a putative phosphorylase on one end and a predicted phosphohydrolase, a hypothetical protein, and a glycosyl hydrolase on the other end of the cluster (Table 2). The functions of these putative proteins in 10,11-dehydrocurvularin biosynthesis are not apparent; thus, their encoding genes are proposed here to delimit the predicted cur biosynthetic cluster.

Fig 2.

The dehydrocurvularin biosynthetic locus of A. terreus AH-02-30-F7 and proposed biosynthesis of 10,11-dehydrocurvularin. (A) Black arrows, fosmids covering the sequenced locus; black block arrows, genes proposed to be involved in dehydrocurvularin biosynthesis; white block arrows, genes proposed to border the dehydrocurvularin biosynthetic cluster; gray block arrows, genes in selected fungal genomes encoding proteins orthologous to those encoded in the sequenced A. terreus AH-02-30-F7 genomic locus, connected by gray boxes; double slash mark, truncated gene. Only (parts of) the numeric strings of the GenBank identifiers are shown (P. tritici-repentis, EDU47223 to EDU47226; A. flavus, EED53047 to EED53051; A. terreus, EAU35010 to EAU35011 and EAU37684 to EAU37686). (B) Model for the biosynthesis of 10,11-dehydrocurvularin.

Table 2.

Sequence similarities and predicted functions of the deduced proteins from the A. terreus dehydrocurvularin biosynthetic locus

| Gene | Gene length (bp) | Protein length (aa) | No. of exons | Predicted function | Conserved domain(s) | Best BLASTP hit in:a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GenBank |

A. terreus NIH2624 |

||||||||

| Accession no. (organism) | E value (% identity) | Accession no. | E value (% identity) | ||||||

| orf1 | 2,276 | 673 | 4 | Phosphorylase | COG0775, nucleoside phosphorylase; pfam13191, ATPase domain | EED52644 (Aspergillus flavus) | 2e−169 (45) | EAU38850 | 1e−145 (45) |

| AtcurS2 | 6,485 | 2,083 | 5 | Dehydrocurvularin synthase nrPKS | SAT-KS-AT-PT-ACP-TE | EDU47223 (Pyrenophora tritici-repentis) | 0.0 (78) | EAU38791 | 0.0 (35) |

| AtcurR | 2,251 | 728 | 2 | Dehydrocurvularin biosynthesis regulator | smart00066, GAL4-like Zn2Cys6 binuclear cluster; smart00906, fungal specific transcription factor | EED53048 (Aspergillus flavus) | 0.0 (71) | EAU35011 | 0.0 (71) |

| AtcurE | 1,924 | 571 | 3 | Dehydrocurvularin exporter | cd06174, major facilitator superfamily | EED53049 (Aspergillus flavus) | 0.0 (85) | EAU35010 | 0.0 (80) |

| AtcurS1 | 7,468 | 2,387 | 6 | Dehydrocurvularin synthase hrPKS | KS-AT-DH- KRS-ER- KRC-ACP | EDU47225 (Pyrenophora tritici-repentis) | 0.0 (76) | EAU32666 | 0.0 (33) |

| orf2 | 672 | 223 | 1 | Metal-dependent phosphohydrolase | smart00471, metal-dependent phosphohydrolase | EFY87661 (Metarhizium acridum) | 3e−59 (47) | EAU37684 | 2e−118 (77) |

| orf3 | 624 | 170 | 3 | Hypothetical protein | NFb | EAW17244 (Neosartorya fischeri) | 4e−06 (29) | EAU37685 | 3e−68 (73) |

| orf4 | 2,181 | 726 | 1 | Glycosyl hydrolase | pfam00933, glycosyl hydrolase family 3, N terminus; pfam01915, glycosyl hydrolase family 3, C terminus | BAE55411 (Aspergillus oryzae) | 0.0 (75) | EAU37686 | 0.0 (90) |

Best BLASTP hit of the putative protein in the A. terreus NIH2624 genome and in the rest of GenBank.

NF, not found.

Synteny with the completely sequenced genome of A. terreus NIH2624 was evident for orf2 through orf4 and beyond, and an orthologous gene pair encoding a transcriptional regulator and an MFS transporter was also detected from a different genomic locale of that strain (Fig. 2A and Table 2). However, no orthologous genes were found for the AtcurS1 and AtcurS2 iPKSs in the A. terreus NIH2624 genome. Among aspergilli, a cluster containing orthologous genes to that of the putative dehydrocurvularin cluster of A. terreus AH-02-30-F7 was identified only in the completely sequenced genome of Aspergillus flavus NRRL3357, an important plant and animal pathogen (38). However, both the nrPKS- and the hrPKS-encoding genes of A. flavus are disrupted and truncated by internal stop codons and deletions that could not be resolved by manual curation of the available nucleotide sequence in GenBank (EQ963475 for the genomic locus) (Fig. 2A). Thus, this derelict cluster may be a molecular fossil evidencing the ability of ancestral A. flavus strains to produce a RAL/DAL-type metabolite that is lost in the contemporary strain.

The genes of the dehydrocurvularin cluster of A. terreus AH-02-30-F7 are orthologous to their equivalents encoded in the characterized RAL clusters for radicicol, hypothemycin, and zearalenol, with identities in the 55 to 61% (hrPKSs) and 49 to 54% (nrPKSs) ranges over their entire lengths. In addition, orphan genomic loci with currently unidentified products, containing nrPKS-hrPKS pairs orthologous to the RAL iPKSs can also be found in the sequenced genomes of many ascomycete fungi. Among these, a locus with a similar gene content and organization to the A. terreus AH-02-30-F7 dehydrocurvularin biosynthetic locus is evident in the genome sequence of the prominent plant-pathogenic fungus Pyrenophora tritici-repentis PT-1C-BFP, the causative agent of spot and blotch necrotrophic diseases of grasses. The encoded proteins of this cryptic P. tritici-repentis cluster show extremely high similarities to those encoded by the Atcur genes. In particular, EDU47225 and EDU47223 of P. tritici-repentis are 76 to 78% identical over their entire lengths to the dehydrocurvularin hrPKS AtCURS1 and nrPKS AtCURS2, respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 2A). While P. tritici-repentis or other Pyrenophora spp. have not been described to biosynthesize curvularins, zearalenone (Fig. 1, compound 3) (a 14-membered RAL) and resorcylide (compound 8) (a 12-membered RAL that is a structural isomer of the 12-membered DAL 10,11-dehydrocurvularin) have been identified from P. teres (39, 40).

Heterologous production of curvularins in yeast.

Heterologous production of RALs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by functional expression of fungal hrPKS and nrPKS genes has emerged as an efficient tool to establish cluster identity and to study the mechanistic details of these enzymes (18, 26, 27, 41). To prove the identity of the putative dehydrocurvularin cluster of A. terreus AH-02-30-F7, we elected to utilize this method instead of relying on gene disruptions in the producer fungus that would have necessitated development of a laborious transformation method (17). Thus, intronless versions of the AtcurS1 and the AtcurS2 genes were placed under the control of the alcohol dehydrogenase promoter within YEpADH2p-derived vectors (27) and were introduced into S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA. This host incorporates a chromosomal copy of the A. nidulans npgA phosphopantetheinyl transferase gene whose product is necessary for the posttranslational modification of acyl carrier protein (ACP) domains in PKSs (33, 34).

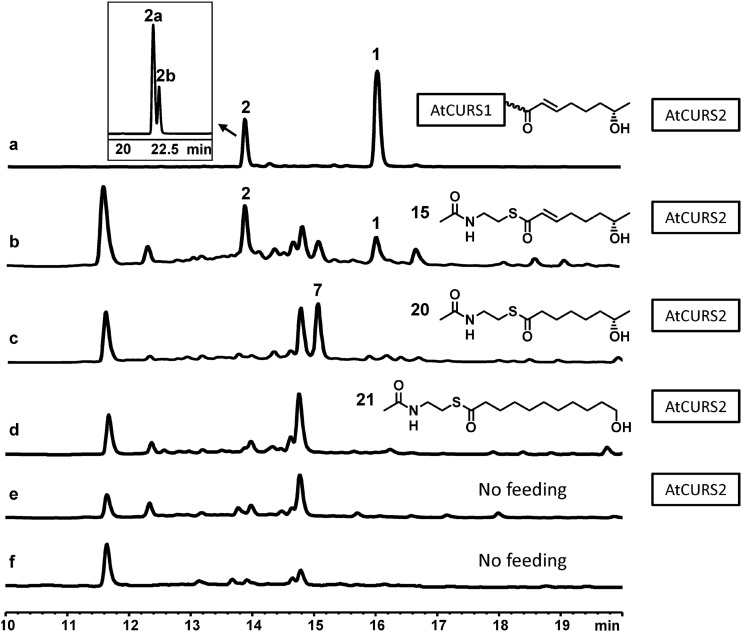

No RAL/DAL-type products were found to be biosynthesized by the yeast host carrying the control expression plasmids (Fig. 3, trace f). However, 10,11-dehydrocurvularin (compound 1) was produced in good yields (isolated yield, 6 mg/liter) by S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA expressing both the AtcurS1 and AtcurS2 genes (Fig. 3, trace a). A second major product (isolated yield, 2.5 mg/liter) produced by the same strain was found to be identical to 11-hydroxycurvularin (compound 2), a water addition product of compound 1. 11-Hydroxycurvularin (compound 2) appears as an enantiomeric 3:1 mixture of 11α-hydroxycurvularin (Fig. 3, compound 2a) and 11β-hydroxycurvularin (Fig. 3, compound 2b). The chemical structures of compounds 1, 2a, and 2b were confirmed by 1H and 13C NMR (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Fig 3.

Heterologous biosynthesis of 10,11-dehydrocurvularin and its analogues in yeast. HPLC profiles of organic extracts of cultures of S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA with the following: plasmids YEpAtCURS1 and YEpAtCURS2 (trace a), YEpAtCURS2 only (traces b to e), and blank vectors (trace f). All traces were monitored at 300 nm. The predicted advanced starter unit for dehydrocurvularin biosynthesis is shown bound to AtCURS1 in trace a. The cultures for traces b to d were supplemented with the SNAC advanced starter unit analogues shown. 1, 10,11-Dehydrocurvularin; 2, 11-hydroxycurvularin, 7, YX-28-4-RF. (Inset) The enantiomeric mixture 2 may be separated by HPLC to 11α-hydroxycurvularin (2a) and 11β-hydroxycurvularin (2b) using a gradient of 10% to 100% CH3CN in H2O over 100 min. The ratio of 2a and 2b is approximately 3:1, which is consistent with the NMR data (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Zhou et al. have previously reported that PKS13, the nrPKS for zearalenone biosynthesis, produces small amounts of acyl resorcylates when expressed in E. coli in the absence of its hrPKS partner. These acyl resorcylates are formed by PKS13 by utilizing various short-chain fatty acyl thioesters as starter units, themselves produced during lipid biosynthesis in the host (42). Similarly, minor products with a UV spectrum indicative of a dihydroxyphenylacetic acid scaffold were also detected in fermentations with the S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA strain expressing only AtcurS2 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) although the low yields of these products prevented us from determining their structures. Supplementation of the cultures of this strain with various short-chain (C6 to C12) fatty acids did not increase the production of these metabolites, nor did this feeding lead to the production of novel polyketides in significant amounts (see Fig. S2). The lack of efficient utilization of these carboxylic acids for acyl dihydroxyphenylacetic acid biosynthesis may be due to PKS substrate selectivity issues, the excessive catabolism of these simple fatty acids, or a failure in their uptake/compartmentalization. The production of the putative shunt metabolites may reflect the ability of the SAT domain to prime polyketide biosynthesis on AtCURS2 by capturing suitable starter units from the yeast host. It remains to be determined whether these starter units are derived from endogenous acyl-CoA molecules or are diverted from the acyl-ACP thioester intermediates on the fungal type I fatty acid synthase (FAS) of the host. It has to be noted, however, that the sequestered conformation of the ACP domains inside the two reaction chambers of the heterododecameric yeast FAS is expected to prevent direct interaction with the SAT domain of the nrPKS (43, 44). In any case, the ability of fungal collaborating nrPKSs to engage in productive cross talk with the primary metabolism of the host is not the exclusive property of PKS13, nor is it limited to bacterial type II FASs as partners.

Comparative bioinformatic and functional analysis of the dehydrocurvularin biosynthetic cluster.

The predicted AtCURS1 (Fig. 2B) is a 2,388-amino-acid (aa), 259.9-kDa enzyme belonging to the fungal clade I hrPKSs (45). AtCURS1 shares end-to-end similarity and displays identical domain composition (KS-AT-DH-KRS-ER-KRC-ACP, where KRs is the KR structural subdomain and KRc is the KR catalytic subdomain) with the characterized RAL hrPKSs. AtCURS1 is predicted to produce the tetraketide 7(S)-hydroxyoct-2(E)-enoic acid; thus, it is programmed to conduct only three consecutive polyketide extension cycles as opposed to the previously characterized hrPKSs producing zearalenone (compound 3) and hypothemycin (compound 4) (five extensions), and radicicol (compound 5) (four extensions). This shorter reduced starter unit then sets up the formation of the 12-membered macrocycle as opposed to the 14-membered rings produced by the previously characterized RAL systems.

The DH domain of AtCURS1 is programmed to act only in extension cycles 2 and 3, while the ER domain acts only in cycle 2. The DH domain features a modified active-site motif incorporating part of the catalytic His/Glu dyad (HkvGstvlfP; amino acids 972 to 981) (17, 46), while the ER domain houses a well-conserved NADPH-binding motif (amino acids 1811 to 1820). The KR domain (consisting of the KRS structural and the KRC catalytic subdomains) (47) is expected to be active in all three extension cycles. It contains an NADPH-binding motif (amino acids 1811 to 1820) and features a full Lys-Ser-Tyr-Asn catalytic tetrad (K2122, S2147, Y2160, and N2164) (41, 46). Reduction at the final (tetraketide) stage may yield a β-hydroxycarboxylic acid intermediate with the R configuration as this is the preferred substrate for DH domains that generate E double bonds (48), presumably including the DH domain in AtCURS1 and the DH domains in the characterized RAL hrPKSs that all produce trans-enoic acyl products. Conversely, at the diketide stage the AtCURS1 KR is predicted to produce a hydroxybutanoic acid intermediate with the 3S configuration that eventually yields the 15S stereocenter in the final DAL product. The corresponding stereocenters are similarly S in hypothemycin (compound 4) and zearalenone (compound 3) but R in radicicol, highlighting a strict and chain length-specific stereochemical control of these short-chain reductases (27, 41). Global comparison of the amino acid sequence of the KR catalytic domain of AtCURS1 with sequences of the RAL hrPKSs failed to cluster these domains according to the stereochemical outcome of their first reduction reactions. Bacterial modular PKSs producing the S-OH configuration are differentiated by the presence of a highly conserved Trp (49, 50), while those that yield the R-OH feature an LDD signature motif (51). Similar to the KR domains of all characterized RAL hrPKSs, the corresponding positions in the AtCURS1 KR feature F2152 (F or Y in RAL hrPKS KRs) and an LRD motif (amino acids 2102 to 2104), again preventing primary sequence-based predictions of the stereochemical programming of the KR reactions.

Expression of AtcurS1 in S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA did not yield any detectable shunt metabolites (results not shown). This is not surprising since the tetraketide product of this hrPKS is expected to remain covalently bound to the ACP of AtCURS1 in the absence of AtCURS2 (21). Further, any 7-hydroxyoct-2-enoic acid released from AtCURS1 by spontaneous hydrolysis may be easily metabolized by the host.

The deduced AtCURS2 is a 2,083-amino-acid, 226.3-kDa enzyme. AtCURS2 and its equivalents from the characterized RAL biosynthetic clusters are all fungal clade I nrPKSs (45) that feature identical domain compositions (SAT-KS-AT-PT-ACP-TE) (Fig. 2B). As in all characterized RAL nrPKSs, the AtCURS2 SAT domain features a Ser-His active-site dyad (S121-H246) as opposed to the Cys-His dyads found in the majority of nrPKS SAT domains in GenBank (52). Interestingly, the conserved Gln that has been proposed to stabilize the oxyanion hole during acyl transfer (46, 53) is replaced by V14 in AtCURS2 and also in its uncharacterized P. tritici-repentis ortholog EDU47223. The substrate of the transacylation reaction catalyzed by the AtCURS2 SAT domain (14, 53, 54) is predicted to be 7(S)-hydroxyoct-2(E)-enoic acid, assembled on the AtCURS1 hrPKS. This is the shortest starter unit among the characterized RAL/DAL systems, as this is a tetraketide as opposed to the pentaketide for radicicol and the hexaketides for zearalenone and hypothemycin biosynthesis (26, 27). Utilizing the transferred tetraketide, AtCURS2 is predicted to conduct four additional chain extension cycles, producing the unreduced part of the nascent octaketide from C-1 to C-8 in 10,11-dehydrocurvularin.

To experimentally characterize precursor selection and product chain length control by AtCURS2, we have synthesized N-acetylcysteamine thioester (SNAC) analogues of potential starter units (see Methods in the supplemental material). Carboxylic acid SNACs had been shown to act as water-soluble and membrane-permeable mimics of carrier protein thioester precursors during in vitro and in vivo production of polyketides in recombinant and native producer systems (30, 31, 42, 55–57). Feeding 7(S)-hydroxyoct-2(E)-enoic acid SNAC (compound 15) to the S. cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA strain expressing only AtcurS2 led to the in vivo production of 10,11-dehydrocurvularin (compound 1) and 11-hydroxycurvularin (compound 2), as expected (Fig. 3, trace b). This experiment demonstrates that AtCURS2 accepts the predicted tetraketide advanced starter unit to produce the native polyketide products. Intact incorporation of SNAC (compound 15) into 10,11-dehydrocurvularin (compound 1) has also been reported in wild-type Alternaria cinerariae (29).

Feeding of the yeast strain expressing only AtcurS2 with 7(S)-hydroxyoctanoic acid SNAC (compound 20), a saturated analogue of the dehydrocurvularin tetraketide starter, was expected to lead to the biosynthesis of curvularin, a reduced analog of 10,11-dehydrocurvularin (compound 1) (Fig. 3, trace c). Instead, a novel product was generated that was identified by HRMS and MS/MS fragmentation as the acyl dihydroxyphenylacetic acid ethyl ester YX-28-4-RF (Fig. 1, compound 7; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Compound 7 was apparently formed when the reduced starter unit of SNAC (Fig. 3, compound 20) was faithfully extended and cyclized in the C8-C3 register by AtCURS2. Formation of compound 7 indicates that AtCURS2 displays some plasticity in its substrate tolerance while retaining overall fidelity for the length of its product chain. Instead of forming the macrolactone, compound 7 was released from the enzyme by ester formation with ethanol, presumably produced during fermentation by the yeast host. The production of similar alcohol esters of acyl resorcylic acids was also detected by Zhou et al. upon expression of the zearalenone nrPKS in E. coli (42). In contrast, SNAC (Fig. 3, compound 20) was reported not to be incorporated into curvularin-type compounds by A. cinerariae (29) although the formation of nonmacrolactone products was presumably not monitored by the authors.

We have also attempted to vary starter unit chain length by utilizing 11-hydroxyundecanoic acid SNAC (Fig. 3, compound 21), a hexaketide SNAC analogue that had previously been used by Zhou et al. to successfully reconstitute RAL biosynthesis with the zearalenone nrPKS (42). However, feeding of this hexaketide led to no detectable production of polyketide products (Fig. 3, trace d). Collectively, these experiments support that the “division of labor” between the collaborating dehydrocurvularin iPKSs is 4+ 4 (an hrPKS-produced tetraketide extended four more times by the nrPKS) (Fig. 2), as opposed to 5+4 for radicicol and 6+3 for zearalenone and hypothemycin (26, 27, 42).

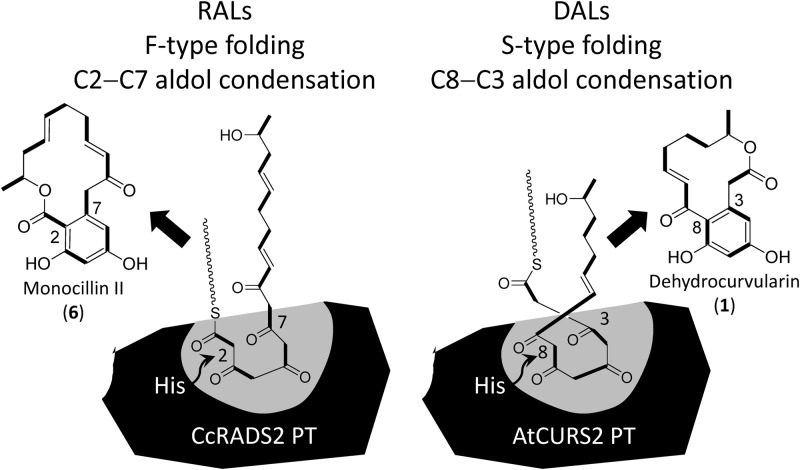

The assembly of the linear nonaketide (zearalenone, compound 3; hypothemycin, compound 4; radicicol, compound 5) and octaketide (dehydrocurvularin) chains is followed by a PT domain-catalyzed regioselective aldol condensation reaction that yields the aromatic ring portion of the RAL/DAL products while the polyketide chain is still tethered on the ACP as a thioester (22–24). The RAL PT domains catalyze this aldol condensation in the C-2–C-7 register, identical to one of the three representative cyclization modes (C-2–C-7, C-4–C-9, and C-6–C-11) that result from the “F-type” folding mode of fungal fused-ring polyketide biosynthesis (Fig. 4). F-type folding incorporates two intact C2 units into the initial cyclohexane ring, as opposed to the S-type folding mode characteristic of Streptomyces aromatic polyketides with three intact C2 units in their initial rings (32). Although first proposed only for fused-ring polycyclic polyketide products (32), the common biosynthetic mechanism (PT-domain-catalyzed cyclization of poly-β-keto intermediates) and sequence similarities (22, 58) allowed the extension of the F-type folding paradigm to RALs and orsellinic acid (59, 60). Thus, PT domain sequences have been shown to form clades according to their F-type folding modes, with the single aromatic ring-forming, C-2–C-7-specific PTs for RALs and orsellinic acid constituting group I (22, 58). In contrast, the ACP-bound octaketide intermediate for dehydrocurvularin (Fig. 2B and 4) undergoes an atypical C-8–C-3 aldol cyclization, similar to cyclization that results from S-type folding in bacteria. Surprisingly, the AtCURS2 PT domain that presumably catalyzes this irregular reaction falls firmly within the group I PT domains (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material), showing 41 to 47% identity to the RAL PTs (the mutual identities of the RAL PTs range from 38 to 53%). As noted in different contexts (61–64), evolutionary change of substrate (and product) specificity might not require gross alteration of the whole sequence of an enzyme but may be achieved by nature using minimal alteration of binding pocket residues. We are currently investigating how engineered mutations of key residues might reroute the reactive polyketide chain within the PT active-site pocket to generate a different regiospecific outcome during the aldol condensation reaction (unpublished data).

Fig 4.

Biosynthetic model for RAL versus DAL formation by C2-C7 versus C8-C3 aldol condensations catalyzed by nrPKS PT domains. CcRADS2, the Chaetomium chiversii radicicol synthase nrPKS (17). Monocillin II is the product of this hrPKS-nrPKS system that is converted to radicicol in further, post-PKS modification steps (17, 18, 27). His, catalytic histidine (23). See the text for details.

The final reaction catalyzed by the deduced AtCURS2 is the closure of the macrolactone ring, catalyzed by the TE domain that features a conserved Ser-Asp-His catalytic triad (S1880, D1907, and H2055) (46, 65). As opposed to most fungal nrPKS TE domains that display Claisen cyclase activity creating C—C bonds (24, 66), the dehydrocurvularin TE domain forms an ester with the hydroxyl group on C-15 serving as the nucleophile (42). Similar to the TE of the zearalenone nrPKS (42), the TE of AtCURS2 is also competent as an acyl transferase, utilizing ethanol as an acceptor for releasing an ester (as opposed to a macrolactone) product, as shown by the production of compound 7 (Fig. 1 and 3, trace c).

Bracketed by AtcurS2 and AtcurS1 in the dehydrocurvularin cluster of A. terreus AH-02-30-F7 are convergently transcribed genes encoding a putative cluster-specific regulator and an exporter (Fig. 2A). The deduced AtCurR is a 728-aa protein similar to GAL4-like fungal transcription factors. These regulators harbor the Zn2Cys6 binuclear cluster DNA-binding domain with the conserved motif Cys-X2-Cys-X6-Cys-X5–12-Cys-X2-Cys-X6–8-Cys (AtCurR; amino acids 38 to 58) (67). While cluster-specific positive regulators were also found encoded in the Gibberella zeae zearalenone and the Chaetomium chiversii radicicol biosynthetic clusters (ZEB2 and RadR, respectively), those proteins are members of the basic region leucine zipper domain family (15, 17). The deduced AtCurE is a 521-aa protein that belongs to the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) exporters. These transporters couple the efflux of internal toxic molecules to the transmembrane proton gradient (68). AtCurE is predicted by the TMHMM server to contain 14 transmembrane domains with both the N and the C termini of the predicted protein localized inside the cell. Putative MFS exporters have also been found encoded in all previously characterized RAL clusters. Since curvularins are found extracellularly in S. cerevisiae expressing only AtCURS1 and AtCURS2, the AtCurE function may be replaced by yeast endogenous exporters during heterologous production of the DAL.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have identified a gene cluster from A. terreus AH-02-30-F7 that we predicted to be responsible for the biosynthesis of 10,11-dehydrocurvularin (compound 1), a dihydroxyphenylacetic acid lactone (DAL) with potent heat shock response-modulatory activity. Heterologous expression in S. cerevisiae of the predicted collaborating hrPKS-nrPKS pair of genes from this cluster yielded compound 1 as well as the spontaneous hydration product 11-hydroxycurvularin (compound 2), providing a functional proof of the identity of the cluster and a convenient platform for the production of 10,11-dehydrocurvularin and, in the future, its analogues. Our work establishes that DALs, similar to RALs, are also produced by iterative fungal PKS pairs. These synthases display chemical modularity by dividing the task of the biosynthesis of the dehydrocurvularin polyketide backbone into the hrPKS-catalyzed production of a reduced tetraketide that is further elaborated to the DAL by an nrPKS catalyzing an additional four cycles of chain extension without reduction. Notwithstanding this similarity, the AtCURS pair shows important divergences from previously identified RAL synthase systems. First, the biosynthetic programming of the AtCURS1 hrPKS is set to yield a shorter reduced polyketide chain (a tetraketide) that forms the 12-membered macrocycle of the DAL, as opposed to the penta- and hexaketides forming the 14-membered macrocycles of the previously characterized RAL systems. Accordingly, feeding an AtCURS2-expressing yeast strain with tetraketide SNAC mimics of the AtCURS1-bound advanced starter unit led to the biosynthesis of the curvularin-type metabolites 1, 2, and 7. Next, the KR domain of AtCURS1 is predicted to be programmed for a variable, product length-dependent stereochemical outcome of its reductions, similar to the KR of the hrPKS involved in hypothemycin, but not in radicicol biosynthesis (41). Lastly, the PT domain of the AtCURS2 nrPKS catalyzes aldol cyclization in a C-8–C-3 register analogous to the S-type folding of unreduced polyketide intermediates in bacteria, as opposed to the F-type folding prevalent in fungi that yields the C-2–C-7 bonds that define RALs. This different regiochemical outcome manifests in spite of the overall high amino acid sequence conservation of the PT domains of AtCURS2 and the RAL nrPKSs, hinting at subtle differences of the orientation of the reactive substrate within the active-site chamber of this enzyme (Fig. 4). These subtle differences in the DAL and RAL biosynthetic systems will help us to further decipher the complex programming mechanisms of fungal iterative polyketide synthetic enzymes. An improved understanding of these mechanisms will allow the engineering of the biosynthesis of “unnatural” hybrid RAL and DAL compounds that may be interrogated for various biological activities, including those relevant to the treatment of cancer and immune response disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (MCB-0948751 to I.M.), the National Research and Development Project of Transgenic Crops of China (2011ZX08009-003-002 to M.L.), the National Basic Research 973 Program of China (2013CB733903 to M.L.), and the Cluster of Excellence Unifying Concepts of Catalysis coordinated by the Technische Universität Berlin (R.S.).

We are grateful to Nancy A. DaSilva (University of California, Irvine) for the strain Saccharomyces cerevisiae BJ5464-NpgA, to Yi Tang (University of California, Los Angeles) for the YEpADH2p vectors, and to Árpád Somogyi (University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ) for the MS/MS spectra and accurate mass measurements.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 January 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03334-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ghisalberti EL, Rowland CM. 1993. 6-Chlorodehydrocurvularin, a new metabolite from Cochliobolus spicifer. J. Nat. Prod. 56:2175–2177 [Google Scholar]

- 2. He J, Wijeratne EM, Bashyal BP, Zhan J, Seliga CJ, Liu MX, Pierson EE, Pierson LS, III, VanEtten HD, Gunatilaka AAL. 2004. Cytotoxic and other metabolites of Aspergillus inhabiting the rhizosphere of Sonoran desert plants. J. Nat. Prod. 67:1985–1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhan J, Wijeratne EMK, Seliga CJ, Zhang J, Pierson EE, Pierson LS, III, VanEtten HD, Gunatilaka AAL. 2004. A new anthraquinone and cytotoxic curvularins of a Penicillium sp. from the rhizosphere of Fallugia paradoxa of the Sonoran desert. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 57:341–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Musgrave OC. 1956. Curvularin. I. Isolation and partial characterization of a metabolic product from a new species of Curvularia. J. Chem. Soc. 1956:4301–4305 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hyeon S-B, Ozaki A, Suzuki A, Tamura S. 1976. Isolation of αβ-dehydrocurvularin and β-hydroxycurvularin from Alternaria tomato as sporulation-suppressing factors. Agric. Biol. Chem. 40:1663–1664 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robeson DJ, Strobel GA, Strange RN. 1985. The identification of a major phytotoxic component from Alternaria macrospora as α,β-dehydrocurvularin. J. Nat. Prod. 48:139–141 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schmidt N, Pautz A, Art J, Rauschkolb P, Jung M, Erkel G, Goldring MB, Kleinert H. 2010. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of iNOS expression in human chondrocytes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 79:722–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elzner S, Schmidt D, Schollmeyer D, Erkel G, Anke T, Kleinert H, Förstermann U, Kunz H. 2008. Inhibitors of inducible NO synthase expression: total synthesis of (S)-curvularin and its ring homologues. ChemMedChem 3:924–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Workman P, Burrows F, Neckers L, Rosen N. 2007. Drugging the cancer chaperone HSP90: combinatorial therapeutic exploitation of oncogene addiction and tumor stress. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1113:202–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McDonald E, Workman P, Jones K. 2006. Inhibitors of the HSP90 molecular chaperone: attacking the master regulator in cancer. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 6:1091–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Santagata S, Xu YM, Wijeratne EM, Kontnik R, Rooney C, Perley CC, Kwon H, Clardy J, Kesari S, Whitesell L, Lindquist S, Gunatilaka AAL. 2012. Using the heat-shock response to discover anticancer compounds that target protein homeostasis. ACS Chem. Biol. 7:340–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Winssinger N, Fontaine JG, Barluenga S. 2009. Hsp90 inhibition with resorcyclic acid lactones (RALs). Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 9:1419–1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Winssinger N, Barluenga S. 2007. Chemistry and biology of resorcylic acid lactones. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2007:22–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gaffoor I, Trail F. 2006. Characterization of two polyketide synthase genes involved in zearalenone biosynthesis in Gibberella zeae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:1793–1799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim YT, Lee YR, Jin J, Han KH, Kim H, Kim JC, Lee T, Yun SH, Lee YW. 2005. Two different polyketide synthase genes are required for synthesis of zearalenone in Gibberella zeae. Mol. Microbiol. 58:1102–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gaffoor I, Brown DW, Plattner R, Proctor RH, Qi W, Trail F. 2005. Functional analysis of the polyketide synthase genes in the filamentous fungus Gibberella zeae (anamorph Fusarium graminearum). Eukaryot. Cell 4:1926–1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang S, Xu Y, Maine EA, Wijeratne EMK, Espinosa-Artiles P, Gunatilaka AAL, Molnár I. 2008. Functional characterization of the biosynthesis of radicicol, an Hsp90 inhibitor resorcylic acid lactone from Chaetomium chiversii. Chem. Biol. 15:1328–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reeves CD, Hu Z, Reid R, Kealey JT. 2008. Genes for biosynthesis of the fungal polyketides hypothemycin from Hypomyces subiculosus and radicicol from Pochonia chlamydosporia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:5121–5129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crawford JM, Townsend CA. 2010. New insights into the formation of fungal aromatic polyketides. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:879–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chooi YH, Tang Y. 2012. Navigating the fungal polyketide chemical space: from genes to molecules. J. Org. Chem. 77:9933–9953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foulke-Abel J, Townsend CA. 2012. Demonstration of starter unit Interprotein transfer from a fatty acid synthase to a multidomain, nonreducing polyketide synthase. ChemBioChem 13:1880–1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li Y, Xu W, Tang Y. 2010. Classification, prediction, and verification of the regioselectivity of fungal polyketide synthase product template domains. J. Biol. Chem. 285:22764–22773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crawford JM, Korman TP, Labonte JW, Vagstad AL, Hill EA, Kamari-Bidkorpeh O, Tsai SC, Townsend CA. 2009. Structural basis for biosynthetic programming of fungal aromatic polyketide cyclization. Nature 461:1139–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crawford JM, Thomas PM, Scheerer JR, Vagstad AL, Kelleher NL, Townsend CA. 2008. Deconstruction of iterative multidomain polyketide synthase function. Science 320:243–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang M, Zhou H, Wirz M, Tang Y, Boddy CN. 2009. A thioesterase from an iterative fungal polyketide synthase shows macrocyclization and cross coupling activity and may play a role in controlling iterative cycling through product offloading. Biochemistry 48:6288–6290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou H, Qiao K, Gao Z, Meehan MJ, Li JW, Zhao X, Dorrestein PC, Vederas JC, Tang Y. 2010. Enzymatic synthesis of resorcylic acid lactones by cooperation of fungal iterative polyketide synthases involved in hypothemycin biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132:4530–4531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhou H, Qiao K, Gao Z, Vederas JC, Tang Y. 2010. Insights into radicicol biosynthesis via heterologous synthesis of intermediates and analogs. J. Biol. Chem. 285:41412–41421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arai K, Rawlings BJ, Yoshizawa Y, Vederas JC. 1989. Biosyntheses of antibiotic A26771B by Penicillium turbatum and dehydrocurvularin by Alternaria cinerariae: comparison of stereochemistry of polyketide and fatty acid enoyl thiol ester reductases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111:3391–3399 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu Y, Li Z, Vederas JC. 1998. Biosynthetic incorporation of advanced precursors into dehydrocurvularin, a polyketide phytotoxin from Alternaria cinerariae. Tetrahedron 54:15937–15958 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Z, Martin FM, Vederas JC. 1992. Biosynthetic incorporation of labeled tetraketide intermediates into dehydrocurvularin, a phytotoxin from Alternaria cinerariae, with assistance of β-oxidation inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114:1531–1533 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yoshizawa Y, Li Z, Reese PB, Vederas JC. 1990. Intact incorporation of acetate-derived di- and tetraketides during biosynthesis of dehydrocurvularin, a macrolide phytotoxin from Alternaria cinerariae. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112:3212–3213 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thomas R. 2001. A biosynthetic classification of fungal and streptomycete fused-ring aromatic polyketides. ChemBioChem 2:612–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma SM, Li JW, Choi JW, Zhou H, Lee KK, Moorthie VA, Xie X, Kealey JT, Da Silva NA, Vederas JC, Tang Y. 2009. Complete reconstitution of a highly reducing iterative polyketide synthase. Science 326:589–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee KK, Da Silva NA, Kealey JT. 2009. Determination of the extent of phosphopantetheinylation of polyketide synthases expressed in Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Anal. Biochem. 394:75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Udwary DW, Merski M, Townsend CA. 2002. A method for prediction of the locations of linker regions within large multifunctional proteins, and application to a type I polyketide synthase. J. Mol. Biol. 323:585–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Choi JH, Jung HY, Kim HS, Cho HG. 2000. PhyloDraw: a phylogenetic tree drawing system. Bioinformatics 16:1056–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gietz RD, Schiestl RH. 2007. Quick and easy yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat. Protoc. 2:35–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Payne GA, Nierman WC, Wortman JR, Pritchard BL, Brown D, Dean RA, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland TE, Machida M, Yu J. 2006. Whole genome comparison of Aspergillus flavus and A. oryzae. Med. Mycol. J. 44(Suppl):9–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Muckova M, Bednarikova M, Gubis J, Bosmanska L, Bartos P. 2010. Cytotoxic metabolites of Pyrenophora teres (DRECHS.), the ascomycete causing the net-blotch of barley. Agriculture (Slovakia) 56:76–83 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nukina M, Sassa T, Oyama H, Ikeda M. 1979. Structures and biological activities of fungal macrolides, pyrenolide and resorcylide. Koen Yoshishu Tennen Yuki Kagobutsu Toronkai 22:362–369 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhou H, Gao Z, Qiao K, Wang J, Vederas JC, Tang Y. 2012. A fungal ketoreductase domain that displays substrate-dependent stereospecificity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8:331–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhou H, Zhan J, Watanabe K, Xie X, Tang Y. 2008. A polyketide macrolactone synthase from the filamentous fungus Gibberella zeae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:6249–6254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jenni S, Leibundgut M, Maier T, Ban N. 2006. Architecture of a fungal fatty acid synthase at 4.5 Å resolution. Science 311:1263–1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Maier T, Leibundgut M, Boehringer D, Ban N. 2010. Structure and function of eukaryotic fatty acid synthases. Q. Rev. Biophys. 43:373–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Baker SE, Kroken S, Inderbitzin P, Asvarak T, Li BY, Shi L, Yoder OC, Turgeon BG. 2006. Two polyketide synthase-encoding genes are required for biosynthesis of the polyketide virulence factor, T-toxin, by Cochliobolus heterostrophus. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19:139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Khosla C, Tang Y, Chen AY, Schnarr NA, Cane DE. 2007. Structure and mechanism of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76:195–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Keatinge-Clay AT. 2012. The structures of type I polyketide synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 29:1050–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Caffrey P. 2003. Conserved amino acid residues correlating with ketoreductase stereospecificity in modular polyketide synthases. ChemBioChem 4:654–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zheng J, Taylor CA, Piasecki SK, Keatinge-Clay AT. 2010. Structural and functional analysis of A-type ketoreductases from the amphotericin modular polyketide synthase. Structure 18:913–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Baerga-Ortiz A, Popovic B, Siskos AP, O'Hare HM, Spiteller D, Williams MG, Campillo N, Spencer JB, Leadlay PF. 2006. Directed mutagenesis alters the stereochemistry of catalysis by isolated ketoreductase domains from the erythromycin polyketide synthase. Chem. Biol. 13:277–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Reid R, Piagentini M, Rodriguez E, Ashley G, Viswanathan N, Carney J, Santi DV, Hutchinson CR, McDaniel R. 2003. A model of structure and catalysis for ketoreductase domains in modular polyketide synthases. Biochemistry 42:72–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Crawford JM, Vagstad AL, Ehrlich KC, Townsend CA. 2008. Starter unit specificity directs genome mining of polyketide synthase pathways in fungi. Bioorg. Chem. 36:16–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Crawford JM, Dancy BC, Hill EA, Udwary DW, Townsend CA. 2006. Identification of a starter unit acyl-carrier protein transacylase domain in an iterative type I polyketide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:16728–16733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Crawford JM, Vagstad AL, Whitworth KP, Ehrlich KC, Townsend CA. 2008. Synthetic strategy of nonreducing iterative polyketide synthases and the origin of the classical “starter-unit effect”. Chembiochem 9:1019–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Arthur C, Cox RJ, Crosby J, Rahman MM, Simpson TJ, Soulas F, Spogli R, Szafranska AE, Westcott J, Winfield CJ. 2002. Synthesis and characterization of acyl carrier protein bound polyketide analogues. Chembiochem 3:253–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hans M, Hornung A, Dziarnowski A, Cane DE, Khosla C. 2003. Mechanistic analysis of acyl transferase domain exchange in polyketide synthase modules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:5366–5374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xie X, Watanabe K, Wojcicki WA, Wang CC, Tang Y. 2006. Biosynthesis of lovastatin analogs with a broadly specific acyltransferase. Chem. Biol. 13:1161–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ahuja M, Chiang YM, Chang SL, Praseuth MB, Entwistle R, Sanchez JF, Lo HC, Yeh HH, Oakley BR, Wang CC. 2012. Illuminating the diversity of aromatic polyketide synthases in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134:8212–8221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sanchez JF, Chiang YM, Szewczyk E, Davidson AD, Ahuja M, Elizabeth Oakley C, Woo Bok J, Keller N, Oakley BR, Wang CC. 2010. Molecular genetic analysis of the orsellinic acid/F9775 gene cluster of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Biosyst. 6:587–593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Schroeckh V, Scherlach K, Nutzmann HW, Shelest E, Schmidt-Heck W, Schuemann J, Martin K, Hertweck C, Brakhage AA. 2009. Intimate bacterial-fungal interaction triggers biosynthesis of archetypal polyketides in Aspergillus nidulans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:14558–14563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Xu Y, Orozco R, Wijeratne EMK, Espinosa-Artiles P, Gunatilaka AAL, Stock SP, Molnár I. 2009. Biosynthesis of the cyclooligomer depsipeptide bassianolide, an insecticidal virulence factor of Beauveria bassiana. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46:353–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Xu Y, Orozco R, Wijeratne EMK, Gunatilaka AAL, Stock SP, Molnár I. 2008. Biosynthesis of the cyclooligomer depsipeptide beauvericin, a virulence factor of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana. Chem. Biol. 15:898–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Finking R, Marahiel MA. 2004. Biosynthesis of nonribosomal peptides. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58:453–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bali S, O'Hare HM, Weissman KJ. 2006. Broad substrate specificity of ketoreductases derived from modular polyketide synthases. ChemBioChem 7:478–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Fujii I, Watanabe A, Sankawa U, Ebizuka Y. 2001. Identification of Claisen cyclase domain in fungal polyketide synthase WA, a naphthopyrone synthase of Aspergillus nidulans. Chem. Biol. 8:189–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cox RJ. 2007. Polyketides, proteins and genes in fungi: programmed nano-machines begin to reveal their secrets. Org. Biomol. Chem. 5:2010–2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. MacPherson S, Larochelle M, Turcotte B. 2006. A fungal family of transcriptional regulators: the zinc cluster proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:583–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Coleman JJ, Mylonakis E. 2009. Efflux in fungi: la piéce de résistance. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000486 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]