Abstract

The thermoacidophile and obligate elemental sulfur (S80)-reducing anaerobe Acidilobus sulfurireducens 18D70 does not associate with bulk solid-phase sulfur during S80-dependent batch culture growth. Cyclic voltammetry indicated the production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) as well as polysulfides after 1 day of batch growth of the organism at pH 3.0 and 81°C. The production of polysulfide is likely due to the abiotic reaction between S80 and the biologically produced H2S, as evinced by a rapid cessation of polysulfide formation when the growth temperature was decreased, inhibiting the biological production of sulfide. After an additional 5 days of growth, nanoparticulate S80 was detected in the cultivation medium, a result of the hydrolysis of polysulfides in acidic medium. To examine whether soluble polysulfides and/or nanoparticulate S80 can serve as terminal electron acceptors (TEA) supporting the growth of A. sulfurireducens, total sulfide concentration and cell density were monitored in batch cultures with S80 provided as a solid phase in the medium or with S80 sequestered in dialysis tubing. The rates of sulfide production in 7-day-old cultures with S80 sequestered in dialysis tubing with pore sizes of 12 to 14 kDa and 6 to 8 kDa were 55% and 22%, respectively, of that of cultures with S80 provided as a solid phase in the medium. These results indicate that the TEA existed in a range of particle sizes that affected its ability to diffuse through dialysis tubing of different pore sizes. Dynamic light scattering revealed that S80 particles generated through polysulfide rapidly grew in size, a rate which was influenced by the pH of the medium and the presence of organic carbon. Thus, S80 particles formed through abiological hydrolysis of polysulfide under acidic conditions appeared to serve as a growth-promoting TEA for A. sulfurireducens.

INTRODUCTION

Terrestrial and hydrothermal spring source waters often contain elevated concentrations of reduced iron, arsenic, and sulfur species (1–3). Upon discharge into less-reducing environments, these chemical species undergo oxidation by a variety of possible biotic and/or abiotic mechanisms, often resulting in precipitation and accumulation as a solid phase (2, 4, 5). Sulfur is of particular importance in hydrothermal environments, as it can exist in a number of different forms in which oxidation states vary between S(−2) and S(+6), polymerize with the formation of S-S bonds, and interact with organic material. Elemental sulfur, S0, exists primarily as an S80 ring that then aggregates into nanocrystalline S8 and eventually to bulk mineral elemental sulfur. The stable form of elemental sulfur at atmospheric T and P is α-S8, but it can exist in over 180 different allotropes and polymorphs (6). Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a key sulfur species in hydrothermal waters that upon oxidation with O2 can form thiosulfate (S2O32−), which disproportionates under acidic conditions to sulfite (SO32−) and elemental sulfur (S80) (7–9). The S80 that is formed from this process accumulates as α-S8 near the point of surface discharge in hydrothermal springs due to its low solubility and slow reactivity in water below 100°C (10). Since a wide array of microorganisms are able to oxidize, reduce, and disproportionate α-S8 (11–14), this represents an important substrate capable of supporting microorganisms inhabiting these environments.

Since the first description of biological S80 reduction in the bacterium Desulfuromonas acetoxidans in 1976 (15), this metabolic process has been identified in a variety of mesophilic and thermophilic organisms distributed in both the bacterial and archaeal domains (13, 16–22). These organisms are typically heterotrophs that couple the oxidation of organic acids, carbohydrates, and/or complex peptides to the reduction of S80 (13, 16–21, 23), although several autotrophic or mixotrophic species that couple H2 oxidation with the reduction of S80 have also been isolated (24–26). The solubility of α-S8 (1 μg liter−1 at 25°C and 15 μg liter−1 at 80°C) (10) is likely too low to sustain the growth rates and yields reported for α-S8-reducing organisms characterized to date (19, 27). Rather, it is likely that α-S8 is activated to more-hydrophilic and/or -soluble forms (e.g., polysulfides) which support the growth of these microbial populations (22, 27).

Polysulfides (Sx2−) are formed by nucleophilic cleavage of the S-S bond of S80 by strong nucleophiles, such as sulfide, resulting in linear chains (typically containing 3 to 6 S atoms) of zero-valent S terminated by sulfhydryl groups (28, 29). Once polysulfide is formed, it can also act as a nucleophile in opening the S80 ring structure (30). Polysulfides have been shown to serve as terminal electron acceptors (TEA) for Wolinella succinogenes (31) and Pyrococcus furiosus (22), and they have been proposed as the TEA supporting the growth of other S80-reducing microorganisms inhabiting circumneutral pH environments (19). However, the amount of sulfur dissolved as polysulfide decreases dramatically with decreasing pH due to the instability of Sx2− in the presence of acid (19, 27, 32) according to the reaction 2 S52− + 4 H+ → α-S8 + 2 H2S (reaction 1), suggesting that the polysulfides are unlikely to support the growth of acidophilic sulfur-reducing populations (reaction 1). Calculations of the concentrations of polysulfides in aqueous solutions at pH 3.0 in equilibrium with excess α-S8 and 1 mM H2S at 80°C indicate a maximum concentration of 10−11 M (19, 27). This low-equilibrium concentration would presumably place constraints on the utilization of polysulfides by microorganisms inhabiting acidic environments and may suggest a role for nanocrystalline S8 formed through polysulfide (reaction 1) to serve as TEA for acidophiles. However, it is not known if polysulfides or nanocrystalline S8 can serve as TEA for thermoacidophilic microorganisms.

The thermoacidophile Acidilobus sulfurireducens strain 18D70 is an obligately anaerobic elemental sulfur reducer that was originally isolated from Dragon Spring, Yellowstone National Park (YNP), Wyoming (11). Recent molecular analyses indicate that A. sulfurireducens (Crenarchaeota, Acidilobales) is a numerically dominant organism in acidic, high-temperature YNP springs (11, 33), and closely related strains of Acidilobales have been detected in acidic terrestrial geothermal environments around the world (13, 18, 34). Previous microscopic analyses of batch cultures of A. sulfurireducens growing in pH 3.0 medium containing α-S8 as the sole TEA indicated that the majority of cells were planktonic and not associated with large elemental sulfur particles during sulfur-dependent growth (35). This suggested that the growth of A. sulfurireducens was supported by the reduction of a soluble form of sulfur. Here, we use a combination of cyclic voltammetry (CV), dynamic light scattering, and physiological experimentation to better understand the chemistry of the sulfur compound(s) supporting the growth of A. sulfurireducens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture conditions.

Acidilobus sulfurireducens strain 18D70 was cultivated in peptone-elemental sulfur (PS) medium buffered to pH 3.0 with trisodium citrate (10 mM final concentration) as previously described (11). PS medium consisted of NH4Cl (0.33 g liter−1), KCl (0.33 g liter−1), CaCl2·2H2O (0.33 g liter−1), MgSO4·7H2O (0.33 g liter−1), KH2PO4 (0.33 g liter−1), peptone (0.025% [wt/vol]), S80 (5 g liter−1), Wolfe's vitamins (1 ml liter−1), and SL-10 trace metals (1 ml liter−1). Briefly, PS medium was dispensed into 120-ml serum bottles and purged for 45 min with N2 gas, and the bottles were then capped with butyl rubber stoppers, followed by sterilization by autoclaving for 30 min. All N2 gas utilized in the present study was passed over H2-reduced heated copper shavings (210°C) in order to remove residual O2. S80 (Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium) was placed in microcentrifuge or Falcon tubes and was heat treated to reduce the possibility of contamination using three rounds of incubation (95°C) for 2 h, followed by incubation at room temperature (∼22°C) for 1 h. Heat-treated S80 was added to PS medium under a stream of sterile N2 gas to a final concentration of 5 g liter−1. Filter-sterilized vitamins and trace metals were also added following autoclave sterilization (11). PS medium was brought to 81°C and held for 24 h, and the gas phase was again exchanged with N2 gas. PS medium preparation was completed by the addition of filter-sterilized and O2-free sodium ascorbate (pH 3.0) to a final concentration of 50 μM as a reductant. Ascorbate cannot serve as a source of energy, carbon, or TEA for A. sulfurireducens (11). Cultures were inoculated with a 1.0% (vol/vol) subsample of an actively growing culture to achieve a starting cell density of roughly 1.0 × 106 cells ml−1 to 2.0 × 106 cells ml−1. The concentration of total sulfide and the production of cells in batch cultures, compared to those of uninoculated controls, served as metrics for describing the activity and growth of A. sulfurireducens, respectively. Total sulfide and cell concentrations in batch cultures were determined using the methylene blue assay and fluorescence microscopic methods, respectively, as previously described (11). Importantly, A. sulfurireducens is incapable of supporting growth via peptide fermentation in the absence of S80 (11). Thus, all growth can be attributed to S80 reduction when cultivated under these conditions.

Growth of A. sulfurireducens with sequestered S80.

S80 was enclosed in dialysis tubing of various pore sizes in batch cultures in order to examine the requirement for physical contact between A. sulfurireducens and the bulk solid-phase S80. Spectra/Por 7 sulfur- and heavy-metal-free membrane tubing (Spectrum Laboratories, Gardena, CA) with pore sizes of 6 to 8 and 12 to 14 kDa (24-mm thickness) were cut in 3-inch lengths. These membranes are stable in aqueous medium that ranges in pH from 2 to 12 and when incubated at temperatures of up to 121°C (http://www.spectrumlabs.com/dialysis/rc.html). Membrane tubing was briefly rinsed in deionized water to remove preservatives and metals and then was incubated in sterile deionized water at 81°C for 24 h. This process was repeated a second time in order to remove residual preservatives. Elemental sulfur was sterilized as described above and was then added to the membrane tubing aseptically to a final concentration of 5 g liter−1. The membrane tubes were sealed with Spectra/Por closures and then transferred to 1-liter wide-mouth medium bottles (Corning, Corning, NY) containing 500 ml of PS medium that was prepared as described above. The transfer of the membrane tubing with elemental sulfur was performed under a constant stream of N2 gas to minimize influx of atmospheric O2. Bottles were sealed with butyl rubber stoppers, heated to 81°C, and again purged with sterile N2 gas to remove residual O2. Medium preparation was completed with the addition of sodium ascorbate to a final concentration of 50 μM. Cultivation experiments were performed in triplicate, and a single uninoculated control was included. Experiments in which cells and S80 were present in the bulk medium were performed in the presence of dialysis membranes (6 to 8 kDa) in order to account for the potential interactions between the membranes and sulfur compounds. Total sulfide production (dissolved and gaseous) was calculated using gas-phase equilibrium calculations as outlined previously (11). The differences in total sulfide production and cell counts between biological replicates and uninoculated controls served as proxies for sulfur reduction activity and cellular growth, respectively.

Synthesis of polysulfide.

Sodium pentasulfide salts were synthesized using methods adapted from Rosen and Tegman (36). Briefly, polysulfide salts were prepared by reacting 0.95 g anhydrous sodium sulfide with 1.55 g crystalline elemental sulfur that had been dried in an oven at 80°C. All preparation and handling of the polysulfide salts were done in a dry anoxic glove box. Reagents were mixed together by grinding, placed in quartz tubes, and sealed under an atmosphere of N2 before evacuation on a vacuum line and sealing of the quartz glass using an acetylene torch. Synthesis took place through melting and reaction for 12 h at 210°C, followed by an annealing step for about half an hour at 350°C, removal and regrinding of the product under an N2 atmosphere, replacement of the mixture into another glass tube, and a final melting and reaction step at 210°C for 10 h. The salts were then washed with hexane to remove residual elemental sulfur impurities, resealed under vacuum, and kept at −20°C in the dark until used for dynamic light-scattering experiments and as standards in voltammetric analysis.

Cyclic voltammetry.

Voltammetric signals are produced when redox-active dissolved or nanoparticulate species interact with the surface of an Au-amalgam (Au-Hg alloy) working electrode. Electron flow resulting from redox half-reactions occurring at specific potentials at a 100-μm-Au-amalgam-diameter working-electrode surface is registered as a current that is proportional to concentration (37). A three-electrode system consisting of a silver/silver chloride reference electrode, a platinum counter electrode, and an Au-amalgam working electrode was used in voltammetric analyses according to the method of Brendel and Luther (38). Cyclic voltammetry was performed between −0.1 and −1.8 V (versus Ag/AgCl) at a scan rate of 1,000 mV s−1 with a 2-s conditioning step. Aqueous and nanoparticulate sulfur species that are electroactive at the Au-amalgam electrode surface of direct relevance to this study include H2S, S8, and polysulfides (e.g., H2S5), in addition to key oxidized intermediates, such as S2O32−, HSO3−, and S4O62− (39, 40). Voltammetric analyses were carried out with an Analytical Instrument Systems, Inc., DLK-60 potentiostat and computer controller. Briefly, 25-ml aliquots were removed from cultures at 1, 3, and 6 days postinoculation and were immediately transferred to a sealed reactor containing the working and reference electrodes that had been prepurged with O2-free N2 gas. The reactor was kept at 81°C using a heated water jacket (Princeton Applied Research, Oak Ridge, TN). Analyses were carried out in sets of at least 10 sequential scans at each sampling point, with the first three scans discarded (allowing the electrode response to stabilize). Standard additions of sodium sulfide and sodium polysulfide were performed using PS medium with the pH adjusted to both 3.0 and 4.0 (noting that polysulfide signals disappear quickly per reaction 1) in order to estimate the concentrations of these species.

Dynamic light scattering.

The size of S80 particles and the rate of S80 particle growth during the hydrolysis of polysulfide were examined using a model 90Plus particle size analyzer (Brookhaven Instruments, Holtsville, NY) at a scattering angle of 90° with the stage temperature held at 81°C. Two milliliters of anaerobic PS base salt medium, prepared as described above, was injected into a 3-ml glass sample vial sealed with Teflon caps under a stream of anoxic N2 gas. S80 was not included in the PS medium. In some applications, peptone was not included in PS medium. The pH of PS medium was adjusted to pH 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 by altering the amount of added sodium citrate and citric acid to a final citrate concentration of 10 mM. A 5 mM polysulfide solution (predominantly H2S5 [32]) was prepared by dissolving polysulfide salts in anaerobic deionized water. Base salt solutions were allowed to equilibrate to the stage temperature of 81°C, and the hydrolysis reaction was initiated by the syringe injection of a 100-μl volume of polysulfide solution to achieve a final concentration of 25 μM. The solution was quickly mixed, followed by initiation of data collection. The average and standard deviation of particle size effective diameters were calculated from two replicate analyses.

RESULTS

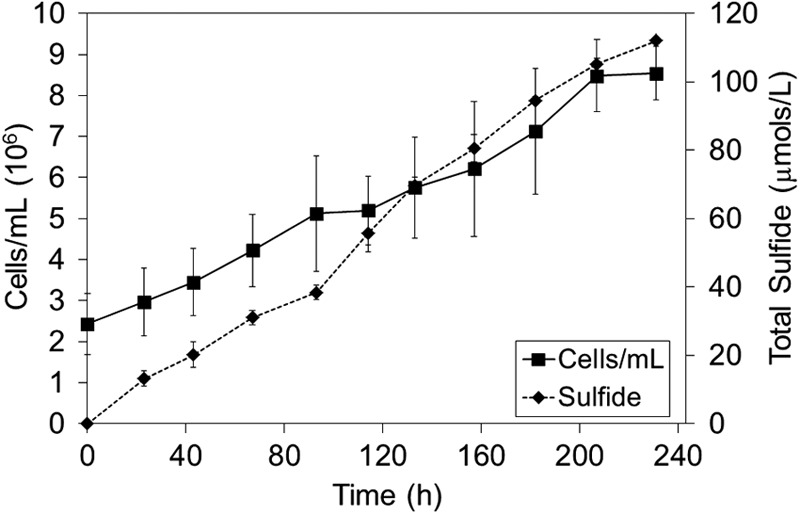

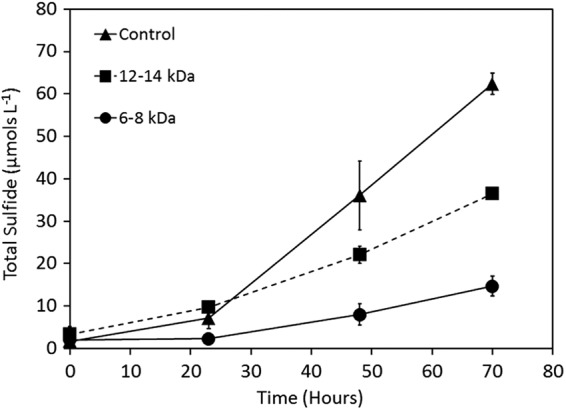

The cell density and the concentration of total sulfide increased at similar rates in cultures of A. sulfurireducens with α-S8 added as the sole TEA (Fig. 1), indicating that the reduction of α-S8 to H2S supports cell replication. The specific growth yield of A. sulfurireducens cultivated under these conditions averaged 59 ± 41 cells/pmol H2S produced. The cultivation of A. sulfurireducens in batch cultures with α-S8 sequestered in semipermeable dialysis tubing provided the first direct evidence that physical contact with solid-phase α-S8 was not necessary for growth (Fig. 2). Relative to growth in the presence of solid-phase α-S8, rates of sulfide production and cellular production decreased systematically with decreasing dialysis tubing pore sizes. The net sulfide production rate decreased 78% and 45% when α-S8 was sequestered in dialysis tubing with pore sizes of 6 to 8 kDa and 12 to 14 kDa, respectively. Likewise, the final cell yield decreased by 62% and 44% when α-S8 was sequestered in dialysis tubing with pore sizes of 6 to 8 kDa and 12 to 14 kDa, respectively (data not shown). The specific growth yield of A. sulfurireducens when cultivated under these conditions over the 70-h incubation period was 53 ± 40, 96 ± 30, or 54 ± 39 cells/pmol H2S produced when sulfur was provided in the medium, sequestered in 6- to 8-kDa dialysis membranes, or sequestered in 12- to 14-kDa dialysis membranes, respectively. Thus, when solid α-S8 is physically separated from cells by a semipermeable membrane, smaller pore sizes limit the availability of reducible sulfur for A. sulfurireducens. The observation that smaller dialysis membrane pore sizes support lower levels of activity and growth than larger dialysis membrane pore sizes indicates that the biologically reducible sulfur compound exhibits a size distribution.

Fig 1.

Cell and sulfide production in cultures of A. sulfurireducens grown in the presence of S80 at 81°C and pH 3.0.

Fig 2.

Total sulfide production in cultures of A. sulfurireducens cultivated at 81°C and pH 3.0 in the presence of S80 (control) or with S80 sequestered in dialysis membranes with pore sizes of 12 to 14 kDa and 6 to 8 kDa.

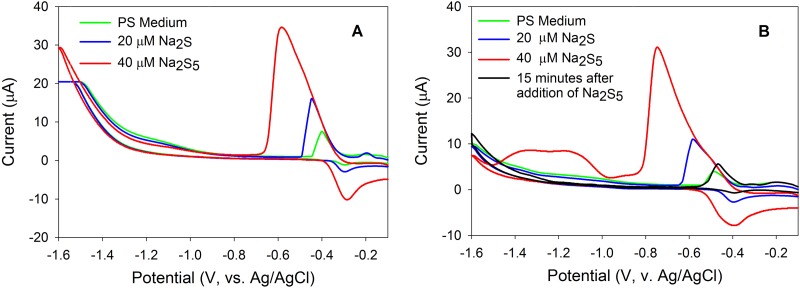

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was used to detect and to quantify soluble and electroactive compounds in batch cultures of A. sulfurireducens, namely, polysulfides (primarily H2S5 at acidic pH [41]; pK1 for H2S5 is 3.5 at 25°C, for example [42]), nanocrystalline S80, and hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Standard additions of Na2S and Na2S5 solutions were performed in PS medium with the pH adjusted to both 3.0 and 4.0. In PS medium with the pH adjusted to 3.0, addition of H2S yielded a peak at −0.45 mV while addition of H2S5 yielded a peak at −0.59 mV, a separation of 0.14 mV (Fig. 3A). In PS medium with the pH adjusted to 4.0, addition of H2S yielded a peak at −0.59 mV while addition of H2S5 yielded a peak at −0.73 mV, a separation of 0.14 mV (Fig. 3B). The addition of H2S5 to PS medium with a pH of 4.0 generated two additional peaks with potentials of −1.00 and −1.20 mV that were barely above the detection limit in the pH 3.0 medium (Fig. 3B), corresponding to the polysulfide hydrolysis product, nanocrystalline S80, and dissolved S80 that exhibit two size distributions (43). After 15 min of additional incubation, both the H2S5 peak and nanocrystalline S80 peaks disappeared in the PS medium with the pH adjusted to 4.0 (Fig. 3B), presumably due to rapid equilibration of polysulfide with S80 and sulfide and coagulation of nanocrystalline S80 causing precipitation of α-S80. A peak attributable to nanocrystalline or dissolved S80 formed due to polysulfide reaction was not able to be definitively assigned in PS medium with the pH adjusted to 3.0 due to the high baseline current in this potential range (−1.0 to 1.6 mV) attributable to proton reduction. In solutions with pH 3.0 and with excess sulfur and 1 mM sulfide (far more concentrated than is present in our medium), the equilibrium concentration of polysulfide is estimated to be ∼34 pM (19), well below the detection limit of our assay. Control experiments done with or without dialysis membranes show no significant differences in the sulfur speciation measured by voltammetry (data not shown), suggesting that there is very limited reaction of these compounds with the dialysis materials used.

Fig 3.

Cyclic voltammograms following the addition of sodium sulfide and polysulfide in PS medium with the pH adjusted to 3.0 (A) and to 4.0 (B). (B) An additional scan of polysulfide-spiked PS medium following 15 min of incubation shows the disappearance of the formed nanocrystalline S80.

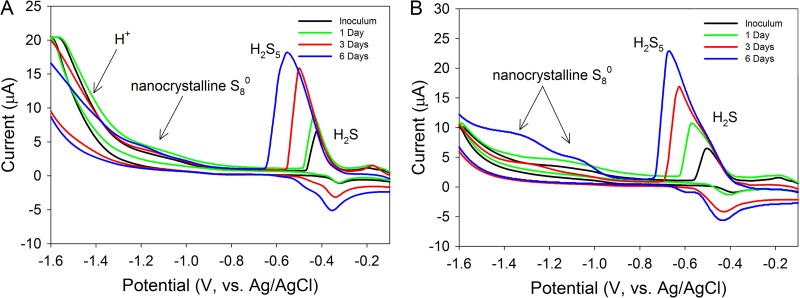

After verifying that sulfide and polysulfide can be detected and quantified in PS medium with the pH adjusted to 3.0 and 4.0 and that the polysulfide reaction product nanocrystalline S80 can be identified in PS medium with the pH adjusted to 4.0 (Fig. 3), we initiated a growth experiment with A. sulfurireducens in PS medium with the pH adjusted to either 3.0 or 4.0 and monitored the production of electroactive compounds using CV (Fig. 4). We note here that sulfide and polysulfide ions react in these solutions that are at potentials that are often only ∼140 mV apart (exact separation depends on specific concentrations and pH). Thus, significant concentrations of one ion may mask small concentrations of the other ion. However, mixtures of the two ions result in one peak composed of two peak components, with a recognizable inflection between the two individual components. In cultures of A. sulfurireducens grown in PS medium with the pH adjusted to 3.0, a peak at −0.45 mV with an amplitude of 10 μA was observed after the first day of growth (Fig. 4A). This peak is attributable to H2S at a concentration of ∼13 μM. By 3 days of growth, a single peak with a potential of −0.48 mV and an amplitude of 16 μA was observed. This peak can be attributed to H2S that has shifted negative due to concentration-dependent effects (43, 44). By 6 days of growth in PS medium with the pH adjusted to 3.0, a single peak centered on −0.59 mV with an amplitude of 18.5 μA was detected. This peak corresponds to primarily H2S5 at a concentration of ∼20 μM with a positive-trending shoulder associated with the H2S part of the H2S5 peak. H2S, H2S5, and nanocrystalline S80 were not observed in uninoculated pH 3.0 medium controls during the duration of the incubation (data not shown), indicating that the production of these compounds was due to biological activity.

Fig 4.

Cyclic voltammograms of electroactive sulfur compounds in cultures of A. sulfurireducens with the pH of the medium adjusted to 3.0 (A) and to 4.0 (B) as a function of incubation period. Cultures were incubated at 81°C.

In cultures of A. sulfurireducens grown in PS medium with the pH adjusted to 4.0, a peak with a potential of −0.59 mV and an amplitude of 11 μA was observed after the first day of growth, with an inflection separating a significant sulfide component at a more positive potential (Fig. 4B). The first peak at −0.49 V is attributable to H2S at a concentration of ∼15 μM, whereas the second peak at −0.59 V is attributable to polysulfide at a concentration of ∼18 μM. Following 3 days of growth, a peak centered at −0.62 mV with an amplitude of 17 μA was observed. This peak had a large shoulder centered at 0.59 mV with an amplitude of 12 μA. The peak with a more negative potential corresponds to H2S5 at a concentration of ∼21 μM, whereas the slightly more positive shoulder corresponds to H2S at a concentration of ∼20 μM. By 6 days of growth in pH 4.0 PS medium, a peak centered on −0.69 mV with an amplitude of 22 μA was detected. This peak corresponds to H2S5 at a concentration of ∼24 μM. This peak also had a large shoulder that centered at 0.59 mV with an amplitude of 12 μA, corresponding to ∼20 μM H2S. In addition to the peaks corresponding to H2S and H2S5, two peaks with half-wave potentials of −1.05 and −1.20 mV were observed. These peaks correspond to two size distributions of nanocrystalline and dissolved elemental sulfur (43). Thus, both H2S and H2S5 increased in concentration during growth in PS medium with a pH of 4.0, with nanocrystalline S80 becoming detectable following 6 days of growth. H2S, H2S5, and nanocrystalline S80 were not observed in uninoculated pH 4.0 medium controls during the duration of the incubation (data not shown), indicating that the production of these compounds was due to biological activity.

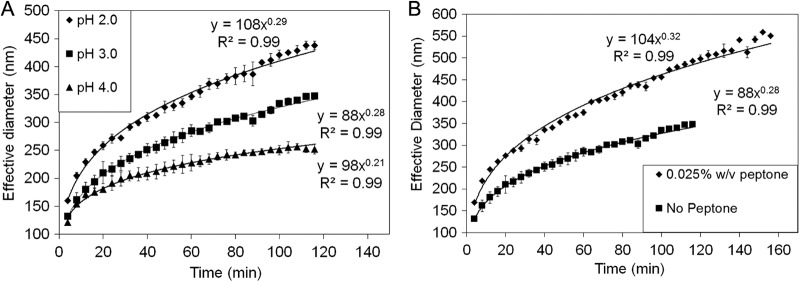

Dynamic light scattering was used to examine the size distribution of nanocrystalline S80 formed as a result of the polysulfide reaction (reaction 1) and to examine the influence of the pH of growth medium on the rate of nanocrystalline S80 formation and aggregation. Dynamic light-scattering experiments were performed in base salt medium lacking peptone with the pH adjusted to 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0. Following addition of 25 μM Na2S5, the initial effective particle size, measured following 2 min of incubation at 81°C, increased with increasingly acidic PS medium (Fig. 5A). The growth of particles, as measured by the effective diameter, was able to be fit (R2 = 0.99 in all treatments) using simple power functions (e.g., y = axb). The scaling factor (b in the power function) increases systematically from 0.21 at a pH of 4.0 to 0.29 at a pH of 2.0, indicating that the rate of nanocrystalline S80 particle aggregation increases with increasingly acidic PS medium. In addition, experiments were performed to examine the influence of peptone on the rate of nanocrystalline S80 formation and aggregation upon addition of 25 μM Na2S5 to PS medium with the pH adjusted to 3.0. The presence of peptone increased the size of the initial nanocrystalline S80 particles and the rate by which the nanocrystalline S80 particles grew in size compared to medium lacking peptone (Fig. 5B). The scaling factor for the power function describing nanocrystalline S80 particle growth in PS medium with peptone was 0.32, which represented the highest scaling factor observed in any of the treatments performed herein. This suggests that both the acidity of the growth medium and the presence of complex organics, such as peptone, increase the rate by which nanocrystalline S80 particles form and aggregate.

Fig 5.

(A) Influence of pH on S80 particle size and particle size growth rates in base salt medium (no peptone) with the pH adjusted to 2.0, 3.0, and 4.0 in the presence of 25 μM polysulfide. (B) Influence of peptone on S80 particle size and particle size growth rates in base salt medium amended with 25 μM polysulfide and with the pH adjusted to 3.0. Both analyses were performed at a temperature of 81°C. Power functions used to model the behavior of particle growth are indicated for each experiment.

DISCUSSION

The production of sulfide when α-S80 was sequestered in dialysis tubing provided the first evidence that direct contact with the solid-phase α-S80 provided in PS medium was not required for the reduction of elemental sulfur. Polysulfides and the polysulfide disproportionation product nanocrystalline S80 were detected with CV analysis of the bulk aqueous phase of cultures of A. sulfurireducens when grown with α-S80 as the sole TEA. In biotic experiments, the amounts of polysulfide and electrochemically active nanocrystalline S80 particles increase in time and corresponding cellular density. Conversely, abiotic additions of sulfide or polysulfide can recreate nanocrystalline S80 particle peaks associated with this same chemistry, but they decrease in time as a function of the coarsening of elemental sulfur. The observation of increasing amounts of nanocrystalline S80 particles is linked to the continued biotic production of sulfide, creating a positive feedback loop of more-available polysulfide and nanoparticulate elemental sulfur (both chemically available in terms of increased rates of reaction with sulfide and biotically available in terms of producing more material that is directly able to be metabolized). The formation of polysulfide under these conditions is likely due to the biological production of sulfide, which through nucleophilic attack of the 8-membered ring of solid-phase α-S8 results in linear chains of zero-valent S terminated by sulfhydryl groups (e.g., S52−) (28). The polysulfides formed from this reaction establish a complex equilibrium with polysulfide species of lengths up to 8 S atoms (28); however, the predominant polysulfide ion in aqueous solutions with acidic pH (<6.8) is likely to contain 4 to 5 S atoms (41).

The growth and sulfide production rate of A. sulfurireducens in PS medium were greater when α-S80 was sequestered in dialysis membranes with larger pore sizes (12 to 14 kDa) than when it was sequestered in dialysis membranes with smaller pore sizes (6 to 8 kDa), indicating that the TEA supporting A. sulfurireducens exhibited a size distribution. This conclusion is supported by the identification of two peaks in CV scans of cultures grown in PS medium with pH 4.0 and to a lesser extent in PS medium with pH 3.0 (due to a combination of higher detection limits for these forms and the higher growth rate of elemental sulfur particles in a more acidic medium). These peaks correspond to two different size distributions of nanocrystalline S80 (43), noting that repeatable electrochemical detection of these peaks requires particles small enough to diffuse to the electrode surface for reaction (45). The peak with the more positive potential (−1.1 mV) most likely represents larger but still nanoparticulate S80, as indicated by a previous study that indicated the disappearance of this peak when solutions containing this nanocrystalline S80 were filtered through 0.45-μm filters (43). Importantly, the peak with a more negative potential (−1.35 mV) remained after 0.45-μm filtration (43), indicating that it is likely to be a smaller-diameter particle. The presence of the particles in PS medium is likely due to the disproportionation of polysulfides (reaction 1), forming sulfide and S80 (28).

It has been suggested that elemental sulfur formed due to polysulfide hydrolysis joins to form aggregates or particles due to its hydrophobic nature (46), with the size of the particles governed by electrostatic repulsive and van der Waals attractive forces (47). Previous studies have shown that the elemental sulfur particles formed upon biotic oxidation of hydrogen sulfide exhibit a size distribution from 0.1 to 1.0 μm (30, 48). Particles of different diameters have different surface-area-to-volume ratios and can be expected to exhibit differences in diffusion rates in aqueous media (49). Thus, the apparent size dependence on the α-S80 reduction rate and cellular growth may be due to the production of nanocrystalline S80 particles of differing sizes that vary in their rate of diffusion across the dialysis membrane. Here, larger S80 particles that were not able to diffuse across dialysis membranes with small pore sizes (e.g., 6 to 8 kDa) but that were able to diffuse through dialysis membranes with larger pore sizes (e.g., 12 to 14 kDa) may explain the higher sulfide production rates in cultures of A. sulfurireducens when solid-phase S80 is sequestered in dialysis membranes with larger pore sizes. While there is no direct conversion between the 2-dimensional metric length (nm) and the 3-dimensional molecular size (kDa), dialysis membranes with pore sizes of 6 to 8 kDa should exclude particles with sizes of >∼1.5 nM, whereas dialysis membranes with pore sizes of 12 to 14 kDa should exclude particles with sizes of >∼3 nM (http://www.spectrumlabs.com/dialysis/PoreSize.html). Thus, the latter membrane would presumably provide ∼2× the amount of reducible nanocrystalline S80 of the former. Intriguingly, the rate of sulfide production in cultures with nanocrystalline S80 sequestered in dialysis tubing with pore sizes of 12 to 14 kDa was ∼2.1 times greater than that of cultures with nanocrystalline S80 sequestered in dialysis tubing with pore sizes of 6 to 8 kDa. It is important to consider that dialysis membranes are spongy matrixes that exhibit a range of pore sizes. Thus, a range of particle sizes may have been allowed to diffuse across each of the membranes, with those diffusing across the 6- to 8-kDa membrane being, on average, smaller than those diffusing across the 12- to 14-kDa membrane.

Dynamic light scattering indicated that the size of the nanocrystalline S80 formed upon the addition of polysulfides (primarily Na2S5) to acidic PS medium increased with time, presumably due to the hydrophobic nature of the particles and van der Waals attractive forces driving particle aggregation (47). The initial size and rate by which elemental sulfur particles aggregated and grew in size were affected by the pH of the medium, with increased rates observed with increasingly acidic PS medium. The influence of pH on particle growth is likely attributable to increased rates of polysulfide disproportionation (reaction 1) as a function of more-acidic conditions (19, 50), which, in turn, would serve to increase the concentration of nanocrystalline S80 particles in solution and increase the frequency by which the particles interact and potentially aggregate. Aggregation ultimately produces particles that are no longer soluble, and the S80 particles precipitate. Thus, increasingly acidic conditions may constrain the availability of S80 particles to support the growth of microorganisms due to enhanced aggregation rates and precipitation rates.

The presence of peptone, an enzymatic digest of animal protein, in PS medium also increased the rate by which nanocrystalline S80 particles aggregated in abiotic experiments. The increased rate of nanocrystalline S80 particle growth in the presence of peptone may result from the adsorption of charged polymers onto the surface of the nanocrystalline S80. The absorption of a polymer at the solid surface/solvent interface can result in stabilization or destabilization of aggregates (30). The enhanced rate of particle aggregation observed in the presence of peptone may be attributable to the absorption of peptides onto the surface of particles, a process which would remove or diminish the electrostatic barrier that keeps particles from aggregating in solution (47). Additional studies focused on the interactions between biomolecules (e.g., proteins, lipids, carbohydrates), S80 particles, and fluid composition are necessary to understand the interplay between these parameters and the influence that this might have on biological activities that rely on nanocrystalline S80.

The specific growth yields of A. sulfurireducens grown in PS medium with S80 present in bulk medium or sequestered in dialysis membranes (average = 68 cells/pmol H2S in experiments presented here) were two orders of magnitude lower than that of the closely related strain Acidilobus aceticus (average = 1,400 cells/pmol H2S) (18). It is not clear how to account for this difference, considering that both organisms couple the oxidation of complex organic carbon sources (e.g., yeast extract, peptone) with the reduction of S80. Nearly identical base salt media are used to cultivate these strains of Acidilobales; however, exponential growth is observed in cultures of A. aceticus and Acidilobus saccharovorans (13, 18), whereas growth in A. sulfurireducens is linear (Fig. 1). This may imply significant death rates in cultures of A. sulfurireducens or may imply substrate limitation that results in constraints on cell growth. Indeed, both A. aceticus and A. saccharovorans can utilize fermentative pathways to support metabolism and were shown to excrete the fermentation product acetate during S80-dependent growth (13, 18). In contrast, A. sulfurireducens cannot ferment complex organic carbon and acetate was not detected in spent medium following S80-dependent growth (11). Thus, it is possible that the limited availability of nanoparticulate S80 due to rapid aggregation, as documented herein, limits the growth of A. sulfurireducens. Given that A. aceticus and A. saccharovorans grow under similar conditions, it is possible that they experience similar constraints. However, when confronted with similar TEA limitations, cultures of the acidophiles A. aceticus and A. saccharovorans are capable of generating additional energy to support cellular growth via fermentative pathways. Thus, the higher specific growth yields of A. aceticus and A. saccharovorans relative to A. sulfurireducens may reflect the utilization of both fermentative and respiratory pathways versus respiratory pathways only, respectively.

The mechanism by which S80 is reduced by A. sulfurireducens is not known. However, the small particle size and neutral charged nature of soluble nanoparticulate S80 particles may facilitate its direct diffusion across the lipid membrane, enabling its intracellular reduction. Such a hypothesis is consistent with the two potential models for S80 reduction proposed for the closely related strain Acidilobus saccharovorans based on genomic data. Here, either a soluble cytoplasmic NAD(P)H-elemental sulfur oxidoreductase (ASAC_1028) or a cytoplasmic membrane-bound sulfur-reducing complex (ASAC_1394-ASA_1397) functions to reduce S80 using reduced NAD(P)H or quinones as the electron donor (51). Importantly, biochemical evidence confirming these functions has yet to be documented in sulfur-reducing crenarchaeota. Nonetheless, draft genomic sequences of A. sulfurireducens (E. S. Boyd, unpublished data) reveal homologs of both protein complexes, suggesting the potential for a similar mechanism of S80 reduction in this strain.

In conclusion, the evidence presented here indicates that the growth of A. sulfurireducens is supported by a soluble form of sulfur that exhibits a size distribution. Cyclic voltammetry identified four electrochemically reactive intermediate sulfur compounds (e.g., sulfide, polysulfide, and two size distributions of nanocrystalline S80) during active growth of A. sulfurireducens in acidic medium. These observations lead to a new model for reduction of elemental sulfur by A. sulfurireducens whereby chemically unstable polysulfides formed via reactions between solid-phase α-S80 and sulfide rapidly disproportionate to S80 in the presence of acid (reaction 1), which quickly aggregates to nanocrystalline S80 that, in turn, continues to increase in size to form α-S80. As sulfide is produced by biological reduction, it can react with smaller elemental sulfur nanocrystals (which would react faster if the rate of reaction is surface limited), reinitiating the cycle and driving average elemental sulfur particle size down with increasing reaction rates. This cycle develops a distribution of nanoparticulate S80 particle sizes better capable of serving as electron acceptors for this organism.

Another potential mechanism of microbial metabolism in this system, consistent with experimental observations here, is the direct metabolism of polysulfides. The equilibrium distribution of dissolved polysulfides with sulfide and α-S8 should be orders of magnitude lower than that observed in solutions after log-phase growth (Fig. 3 and 4) (32). The observation of significant polysulfides suggests either disequilibrium with reaction 1 or that a different reaction involving nanoparticulate S80 or dissolved/nanoparticulate elemental sulfur associated with organic derivatives, such as peptones, is driving polysulfide concentrations. The systematic decrease in sulfide production activity in cultures of A. sulfurireducens when solid-phase α-S80 is physically separated by dialysis membranes with decreasing membrane pore size may be the result of the restricted diffusion of nanocrystalline S80 across the membrane, which, in turn, constrains its availability to support the growth of A. sulfurireducens, which is reflected in lower growth yields in these cultures. This lends support to the hypothesis that nanoparticulate S80, and not polysulfide, which can be expected to exhibit a near-uniform size distribution at this pH (41), is the electron acceptor supporting the growth of A. sulfurireducens. Both models help to explain why A. sulfurireducens is not observed to associate with the solid-phase α-S80 in PS medium. Thus, the abiotic interactions between sulfur species, the products formed from these reactions, and the rates of these reactions (e.g., formation, disproportionation, aggregation, and precipitation) are likely to place constraints on the availability of elemental sulfur that is required to support the activity of this organism. Future studies aimed at quantifying the kinetics of these reactions in pure cultures and natural environmental systems will continue to inform our understanding of the dynamic interplay between biological and abiological processes in defining the ecological niche of elemental sulfur-respiring organisms in the natural environment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) grants PIRE-0968421 and EAR-1123689 (E.S.B.) and NSF grant EAR-1304352 (G.K.D.). G.K.D. additionally acknowledges support from the Montana State University Thermal Biology Program visiting scholar program.

We thank Gill Geesey for comments on a previous version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Shock EL, Holland M, Meyer-Dombard D, Amend JP, Osburn GR, Fischer TP. 2010. Quantifying inorganic sources of geochemical energy in hydrothermal ecosystems, Yellowstone National Park, USA. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74:4005–4043 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nordstrom DK, Ball JW, McCleskey RB. 2005. Ground water to surface water: chemistry of thermal outflows in Yellowstone National Park, p 143–162 In Inskeep WP, McDermott TR. (ed), Geothermal biology and geochemistry in Yellowstone National Park, vol 1 Montana State University, Bozeman, MT [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCleskey RB, Ball JW, Nordstrom DK, Holloway JM, Taylor HE. 2005. Water-chemistry data for selected hot springs, geysers, and streams in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, 2001–2002. Open-file report 2004-1316. U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steudal R. 2003. Aqueous sulfur sols. Top. Curr. Chem. 230:153–166 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Langner HW, Jackson CR, McDermott TR, Inskeep WP. 2001. Rapid oxidation of arsenite in a hot spring ecosystem, Yellowstone National Park. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35:3302–3309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meyer B. 1964. Solid allotropes of sulfur. Chem. Rev. 64:429–451 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nordstrom DK, Ball JW, McCleskey RB. 2004. Oxidation reactions for reduced Fe, As, and S in thermal outflows of Yellowstone National Park: biotic or abiotic?, p 59–62 In Seal RR, Wanty RB. (ed), Water-rock interaction. A. A. Balkema, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu Y, Schoonen AA, Nordstrom DK, Cunningham KM, Ball JW. 1998. Sulfur geochemistry of hydrothermal waters in Yellowstone National Park. I. The origin of thiosulfate in hot spring waters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 62:3729–3743 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnston F, McAmish L. 1973. A study of the rates of sulfur production in acid thiosulfate solutions using S-35. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 42:112–119 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kamyshny A. 2009. Solubility of cyclooctasulfur in pure water and sea water at different temperatures. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73:6022–6028 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boyd ES, Jackson RA, Encarnacion G, Zahn JA, Beard T, Leavitt WD, Pi Y, Zhang CL, Pearson A, Geesey GG. 2007. Isolation, characterization, and ecology of sulfur-respiring crenarchaea inhabiting acid-sulfate-chloride geothermal springs in Yellowstone National Park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:6669–6677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shima S, Suzuki K-I. 1993. Hydrogenobacter acidophilus sp. nov., a thermoacidophilic, aerobic, hydrogen-oxidizing bacterium requiring elemental sulfur for growth. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43:703–708 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prokofeva MI, Kostrikina NA, Kolganova TV, Tourova TP, Lysenko AM, Lebedinsky AV, Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA. 2009. Isolation of the anaerobic thermoacidophilic crenarchaeote Acidilobus saccharovorans sp. nov. and proposal of Acidilobales ord. nov., including Acidilobaceae fam. nov. and Caldisphaeraceae fam. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59:3116–3122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Finster K, Liesack W, Thamdrup B. 1998. Elemental sulfur and thiosulfate disproportionation by Desulfocapsa sulfoexigens sp. nov., a new anaerobic bacterium isolated from marine surface sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:119–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pfennig N, Biebl H. 1976. Desulfurornonas acetoxidans gen. nov. and sp. nov., a new anaerobic, sulfur-reducing, acetate-oxidizing bacterium. Arch. Microbiol. 110:3–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hedderich R, Klimmech O, Kröger A, Dirmeier R, Keller M, Stetter KO. 1999. Anaerobic respiration with elemental sulfur and with disulfides. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:353–381 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stetter KO, Fiala G, Huber G, Huber R, Segerer A. 1990. Hyperthermophilic microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 75:117–124 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prokofeva M, Miroshnichenko M, Kostrikina N, Chernyh N, Kuznetsov B, Tourova T, Bonch-Osmolovskaya E. 2000. Acidilobus aceticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel anaerobic thermoacidophilic archaeon from continental hot vents in Kamchatka. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:2001–2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schauder R, Müller E. 1993. Polysulfide as a possible substrate for sulfur reducing bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 160:377–383 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA. 1994. Bacterial sulfur reduction in hot vents. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 15:65–77 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kletzin A, Urich T, Müller F, Bandeiras TM, Gomes CM. 2004. Dissimilatory oxidation and reduction of elemental sulfur in thermophilic Archaea. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 36:77–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blumentals, Itoh M, Olson GJ, Kelly RM. 1990. Role of polysulfides in reduction of elemental sulfur by the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus furiosus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1255–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA, Slesarev AI, Miroshnichenko ML, Svetlichnaya TP, Alekseev VA. 1988. Characterization of Desulfurococcus amylolyticus n. sp.—a novel extremely thermophilic archaebacterium isolated from Kamchatka and Kurils hot springs. Mikrobiologiia 59:94–101 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jochimsen B, Peinemann-Simon S, Völker H, Stüben D, Botz R, Stoffers P, Dando PR, Thomm M. 1997. Stetteria hydrogenophila, gen. nov. and sp. nov., a novel mixotrophic sulfur-dependent crenarchaeote isolated from Milos, Greece. Extremophiles 1(2):67–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miroshnichenko ML, Gongadze GA, Lysenko AM, Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA. 1993. Desulfurella multipotens sp. nov., a new sulfur-respiring thermophilic eubacterium from Raoul Island (Kermadec archipelago, New Zealand). Arch. Microbiol. 161:88–93 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Segerer AH, Trincone A, Gahrtz M, Stetter KO. 1991. Stygiolobus azoricus gen. nov., sp. nov. represents a novel genus of anaerobic, extremely thermoacidophilic archaebacteria of the order Sulfolobales. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:495–501 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schauder R, Kröger A. 1993. Bacterial sulphur respiration. Arch. Microbiol. 159:491–497 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Steudel R. 2003. Inorganic polysulfides Sn2− and radical anions Sn.−. Top. Curr. Chem. 231:127–152 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davis RE. 1968. Mechanisms of sulfur reactions, p 770 In Nickless G. (ed), Inorganic sulphur chemistry. Elsevier Publishing Company, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kleinjan W. 2005. Biologically produced sulfur particles and sulfur ions: effects on a biotechnological process for the removal of hydrogen sulfide gas from gas streams. Wageningen Universiteit, Wageningen, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 31. Klimmek O, Kröger A, Steudel R, Holdt G. 1991. Growth of Wolinella succinogenes with polysulphide as terminal acceptor of phosphorylative electron transport. Arch. Microbiol. 155:177–182 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kamyshny A, Jr, Gun J, Rizkov D, Voitsekovski T, Lev O. 2007. Equilibrium distribution of polysulfide ions in aqueous solutions at different temperatures by rapid single phase derivatization. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41:2395–2400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Inskeep WP, Rusch DB, Jay ZJ, Herrgard MJ, Kozubal MA, Richardson TH, Macur RE, Hamamura N, Jennings Rd, Fouke BW, Reysenbach A-L, Roberto F, Young M, Schwartz A, Boyd ES, Badger J, Mathur EJ, Ortmann AC, Bateson M, Geesey GG, Frazier M. 2010. Metagenomes from high-temperature chemotrophic systems reveal geochemical controls on microbial community structure and function. PLoS One 5:e9773 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Perevalova AA, Kolganova TV, Birkeland N-K, Schleper C, Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA, Lebedinsky AV. 2008. Distribution of crenarchaeota representatives in terrestrial hot springs of Russia and Iceland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7620–7628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boyd ES. 2007. Biology of acid-sulfate-chloride springs in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, United States of America. Montana State University, Bozeman, MT [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rosen E, Tegman R. 1971. A preparative and X-ray powder diffraction study of the polysulfides Na2S2, Na2S4, and Na2S5. Acta Chem. Scand. 25:3329–3336 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Taillefert M, Rozan TF. (ed). 2002. Electrochemical methods for the environmental analysis of trace elements biogeochemistry. American Chemical Society, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brendel PJ, Luther GW. 1995. Development of a gold amalgam voltammetric microelectrode for the determination of dissolved Fe, Mn, O2, and S(-II) in porewaters of marine and fresh-water sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 29:751–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Luther GWI, Glazer BT, Hohmann L, Popp J, Taillefert M, Rozan TF, Brendel PJ, Theberge SM, Nuzzio DB. 2001. Sulfur speciation monitored in situ with solid state gold amalgam voltammetric microelectrodes: polysulfides as a special case in sediments, microbial mats and hydrothermal vent waters. J. Environ. Monit. 3:61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Druschel GK, Hamers RJ, Luther GW, Banfield JF. 2003. Kinetics and mechanism of trithionate and tetrathionate oxidation at low pH by hydroxyl radicals. Aquat. Geochem. 9:145–164 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Giggenbach W. 1972. Optical spectra and equilibrium distribution of polysulfide ions in aqueous solution at 20°. Inorg. Chem. 11:1201–1207 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gun J, Goifman A, Shkrob I, Kamyshny A, Ginzburg B, Hadas O, Dor I, Modestov AD, Lev O. 2000. Formation of polysulfides in an oxygen rich freshwater lake and their role in the production of volatile sulfur compounds in aquatic systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34:4741–4746 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lorenson G. 2006. Application of in situ Au-Amalgam microelectrodes in Yellowstone National Park to guide microbial sampling: an investigation into arsenite and polysulfide detection to define microbial habitats. M.S. thesis University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bura-Nakić E, Krznarić D, Helz GR, Ciglenečki I. 2011. Characterization of iron sulfide species in model solutions by cyclic voltammetry. Revisiting an old problem. Electroanalysis 23:1376–1382 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Taillefert M, Bono AB, Luther GW. 2000. Reactivity of freshly formed Fe(III) in synthetic solutions and (pore)waters: voltammetric evidence of an aging process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34:2169–2177 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rojas J, Geirsig M, Tributsch H. 1995. Sulfur colloids as temporary energy reservoirs for Thiobacillus ferroxidans during pyrite oxidation. Arch. Microbiol. 163:352–356 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kleinjan WE, de Keizer A, Janssen AJH. 2003. Biologically produced sulfur. Top. Curr. Chem. 230:167–188 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kleinjan WE, de Keizer A, Janssen AJH. 2005. Kinetics of the reaction between dissolved sodium sulfide and biologically produced sulfur. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 44:309–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Borkovec M, Schurtenberger P. 1998. Aggregation in charge-stabilized colloidal suspensions revisited. Langmuir 14:1951–1954 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kamyshny A, Jr, Goifman A, Rizkov D, Lev O. 2003. Kinetics of disproportionation of inorganic polysulfides in undersaturated aqueous solutions at environmentally relevant conditions. Aquat. Geochem. 9:291–304 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mardanov AV, Svetlitchnyi VA, Beletsky AV, Prokofeva MI, Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA, Ravin NV, Skryabin KG. 2010. The genome sequence of the crenarchaeon Acidilobus saccharovorans supports a new order, Acidilobales, and suggests an important ecological role in terrestrial acidic hot springs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:5652–5657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]