Abstract

Flagellar motility and chemotaxis by Vibrio fischeri are important behaviors mediating the colonization of its mutualistic host, the Hawaiian bobtail squid. However, none of the 43 putative methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs) encoded in the V. fischeri genome has been previously characterized. Using both an available transposon mutant collection and directed mutagenesis, we isolated mutants for 19 of these genes, and screened them for altered chemotaxis to six previously identified chemoattractants. Only one mutant was defective in responding to any of the tested compounds; the disrupted gene was thus named vfcA (Vibrio fischeri chemoreceptor A; locus tag VF_0777). In soft-agar plates, mutants disrupted in vfcA did not exhibit the serine-sensing chemotactic ring, and the pattern of migration in the mutant was not affected by the addition of exogenous serine. Using a capillary chemotaxis assay, we showed that, unlike wild-type V. fischeri, the vfcA mutant did not undergo chemotaxis toward serine and that expression of vfcA on a plasmid in the mutant was sufficient to restore the behavior. In addition to serine, we demonstrated that alanine, cysteine, and threonine are strong attractants for wild-type V. fischeri and that the attraction is also mediated by VfcA. This study thus provides the first insights into how V. fischeri integrates information from one of its 43 MCPs to respond to environmental stimuli.

INTRODUCTION

Flagellar motility is one of several behaviors used by bacteria to migrate through their surroundings (1). Migration to preferred environmental conditions is mediated by a behavior known as chemotaxis (2), which allows the bacterium to sense gradients of attractants and respond by controlling the directionality of the flagellar motor (3). Methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs) function as receptors that bind attractants or repellants, usually in the periplasm. Upon ligand binding, MCPs transduce a signal through the CheAY two-component system to affect a change in the tumbling frequency of the flagella (4). By altering the tumbling frequency, MCPs direct an average change in the direction of travel for the bacteria. In Escherichia coli K-12, a total of five MCPs enable sensing of numerous attractants, including amino acids, peptides, galactose, ribose, and oxygen (5–9). However, as more diverse bacterial species have been studied, we have learned that bacterial chemotaxis is frequently more complex than the E. coli paradigm (10, 11). Bioinformatics and increased genome sequence availability have revealed that both the number and the domain structure of predicted MCPs vary greatly between species (12–14). Work in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a species that encodes 26 MCPs in strain PAO1, has characterized 9 MCPs that mediate chemotaxis toward ligands such as amino acids, trichloroethylene, and malate (15–18). However, even in this relatively well-studied organism, high-throughput attempts to identify MCP ligands have been largely inconclusive and, in one case, only successful when energy taxis, mediated by Aer, is also disrupted (15).

Within the Vibrionaceae, the genetic basis of chemotaxis has not been well characterized. Even in the human pathogen Vibrio cholerae, only 3 of up to 45 putative MCPs, contributing to aerotaxis, amino acid chemotaxis, and chemotaxis toward the chitin-derived sugars N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N,N′-diacetylchitobiose [(GlcNAc)2] have been described (19–21). The genome of the squid symbiont Vibrio fischeri (strain ES114) encodes 43 predicted MCPs (22, 23), none of which have been studied, despite the importance of chemotaxis and flagellar motility in the symbiotic lifestyle of this organism (24–28). Because some of the nutrients provided by its squid host have been shown to be chemoattractants for V. fischeri (28, 29), we hypothesized that it would be possible to delimit the chemotactic signaling pathways in the bacterium—and during host colonization—by assigning ligands to the MCPs encoded by the bacterium. In the present study, we screened 19 MCPs in V. fischeri ES114 and identified a single gene product that mediates chemotaxis to multiple amino acids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in the present study are listed in Table 1. V. fischeri strains are derived from strain ES114 (30) (isolate MJM1100) and were grown at 28°C in either Luria-Bertani salt (LBS) medium (10 g of Bacto tryptone/liter, 5 g of yeast extract/liter, 20 g NaCl/liter, and 50 ml of 1 M Tris buffer [pH 7.5] in distilled water) or seawater-based tryptone (SWT) medium (5 g of Bacto tryptone/liter, 3 g of yeast extract/liter, 3 ml of glycerol, 700 ml of Instant Ocean [Aquarium Systems, Inc., Mentor, OH] at a salinity of 33 to 35 ppt, and 300 ml of distilled water). E. coli strains, as used for cloning, were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium or brain heart infusion medium (BD, Sparks, MD). When appropriate, antibiotics were added to media at the following concentrations: erythromycin at 5 μg/ml for V. fischeri and 150 μg/ml for E. coli and chloramphenicol at 2.5 μg/ml for V. fischeri and 25 μg/ml for E. coli. Growth media were solidified with 1.5% agar as needed.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| V. fischeri | ||

| MJM1100 | ES114, sequenced wild-type E. scolopes light organ isolate | 30 |

| CAB1500 | vfcA::pCAB15 Campbell mutant | This study |

| CAB1501 | VF_1133::pCAB16 Campbell mutant | This study |

| CAB1502 | VF_1789::pCAB17 Campbell mutant | This study |

| CAB1503 | VF_2161::pCAB18 Campbell mutant | This study |

| CAB1504 | VF_A0325::pCAB19 Campbell mutant | This study |

| CAB1505 | VF_A0448::pCAB20 Campbell mutant | This study |

| CAB1506 | VF_A0677::pCAB21 Campbell mutant | This study |

| MB06594 | VF_1503::Tnerm | This study |

| MB08238 | VF_A0528::Tnerm | This study |

| MB08251 | VF_A0481::Tnerm | This study |

| MB08831 | VF_A0527::Tnerm | This study |

| MB20125 | VF_1138::Tnerm | This study |

| MB20164 | VF_A0170::Tnerm | This study |

| MB21095 | VF_1652::Tnerm | This study |

| MB20465 | VF_A1072::Tnerm | This study |

| MB20467 | VF_1117::Tnerm | This study |

| MB09616 | VF_A1084::Tnerm | This study |

| MB09969 | VF_0987::Tnerm | This study |

| MB21134 | VF_1618::Tnerm | This study |

| MB09076 | vfcA::Tnerm | This study |

| MB08701 | cheA::Tnerm | Brennan et al., unpublished |

| CAB1516 | MJM1100 harboring pVSV105 | This study |

| CAB1517 | MJM1100 harboring pCAB26 | This study |

| CAB1523 | MB09076 harboring pVSV105 | This study |

| CAB1524 | MB09076 harboring pCAB26 | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α-λpir | Cloning vector | 55 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEVS122 | oriR6K-based suicide vector, Ermr | 32 |

| pEVS104 | Conjugative helper plasmid, Kanr | 33 |

| pCAB15 | pEVS122::′vfcA′ | This study |

| pCAB16 | pEVS122::′VF_1133′ | This study |

| pCAB17 | pEVS122::′VF_1789′ | This study |

| pCAB18 | pEVS122::′VF_2161′ | This study |

| pCAB19 | pEVS122::′VF_A0325′ | This study |

| pCAB20 | pEVS122::′VF_A0448′ | This study |

| pCAB21 | pEVS122::′VF_A0677′ | This study |

| pVSV105 | pES213-based plasmid used for complementation, Cmr | 37 |

| pCAB26 | pVSV105 containing vfcA ORF and 350 bp upstream | This study |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Ermr, erythromycin resistance; Kanr, kanamycin resistance.

Construction and isolation of MCP mutants.

To isolate mutants disrupted in one of the V. fischeri MCP genes, we utilized the MB transposon mutant collection (C. A. Brennan et al., unpublished data) and modified an approach we have successfully used previously to identify mutants carrying a transposon insertion in a specific gene (31). Briefly, pooled templates were amplified by PCR with one primer anchored in the transposon (MJM-127; ∼100 bp from either end) and a second primer or primer mixture that anneals to a conserved region within MCP genes (either MJM-179 or a mixture of 13 primers [MJM-173, MJM-175, MJM-176, MJM-181, MJM-184, MJM-186, MJM-187, MJM-192, MJM-193, MJM-195, MJM-201, MJM-205, and MJM-206]; Table 2). We predicted that a band of approximately 500 to 1,500 bp would appear only if there were a transposon insertion in or near an MCP. Since MCPs are often encoded in tandem in the genome, it was also possible to identify an insertion in the 3′ end of an MCP encoded upstream of the one in which the MCP-specific primer bound. Bands identified in this manner were purified and sequenced with primer 170Int2. The strain containing the mutation of interest was subsequently isolated. Using this approach, we screened 3,168 members of the MB collection and identified mutants separately disrupted in 12 of the 43 MCP-encoding genes.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| MJM-313F | GCCCCGGGGCTCTTACTTGGTTGGCTTCTAAC |

| MJM-314R | GCGCATGCATCGTAATGGTATCTTTACCTGCAT |

| MJM-315F | GCCCCGGGATCCATGCCTTTAGTGAGCTTATC |

| MJM-316R | GCGCATGCTTTGATTAACGGCTTTATTAACCA |

| MJM-317F | GCCCCGGGTCAACTTGCTGCAAATATTGACTA |

| MJM-318R | GCGCATGCAAAGTAATGGTAAGCTGATGGTTG |

| MJM-319F | GCCCCGGGCGAGTTGCAAGTACAATAGACAACA |

| MJM-320R | GCGCATGCGCAATGATAAAAGCTAACCCGAAT |

| MJM-321F | GCCCCGGGACACAAATGATGGAGATGAAACG |

| MJM-322R | GCGCATGCGCCACAATAACTAATGTGAACAACA |

| MJM-323F | GCCCCGGGGCCTCTACACTTGAGGAAGAACA |

| MJM-324R | GCGCATGCGCTAAAATAGTTAGACCTGCTGTGG |

| MJM-325F | GCCCCGGGCACGCTTGAGCTTCCTACTATTCT |

| MJM-326R | GCGCATGCTGATATTACCGTCACCATCCATTA |

| MJM-127 | ACAAGCATAAAGCTTGCTCAATCAATCACC |

| MJM-179 | GCCACGGCCTTGTTCGCCGGC |

| MJM-173 | ACCACGGCCACTTTCACCGGC |

| MJM-175 | ACCACGCCCCATTTCACCAGC |

| MJM-176 | GCCTCGACCATATTCACCAGC |

| MJM-181 | TCCTCGACCTTGTTCGCCAGC |

| MJM-184 | ACCTCGCCCTTGTTCACCCGC |

| MJM-186 | TCCTCTTCCTTGTTCACCAGC |

| MJM-187 | ACCACGACCATATTCACCTGC |

| MJM-192 | ACCTCGGCCTTGCTCTCCAGC |

| MJM-193 | ACCACGACCTTGTTCGCCAGC |

| MJM-195 | CCCTCGCCCACTCTCACCAGC |

| MJM-201 | ACCTCGACCAGATTCACCAGC |

| MJM-205 | ACCACGACCATGATCACCAGC |

| MJM-206 | ACCTCTTCCCGCTTCACCGGC |

| 170Int2 | AGCTTGCTCAATCAATCACC |

| ARB1 | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACNNNNNNNNNNGATAT |

| 170Ext3 | GCAGTTCAACCTGTTGATAGTACG |

| ARB2 | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTAC |

| 170Int3 | CAAAGCAATTTTGAGTGACACAGG |

| 170Seq1 | AACACTTAACGGCTGACA |

| 0777compF | GCGCATGCCCAAGTTTAAAAGAATTACG |

| 0777compR | GCGGTACCTTACAGTTTAAATCGGTCGA |

Campbell-type mutagenesis using the suicide vector pEVS122 (32) was performed to generate disruptions in an additional seven MCP genes: vfcA (VF_0777), VF_1133, VF_1789, VF_A0325, VF_A0448, VF_A0677, and VF_2161. Using the following primer pairs, 500 bp of homology near the 5′ end of each open reading frame (ORF) was amplified for each gene by PCR: VF_0777, MJM-313F and MJM-314R; VF_1133, MJM-315F and MJM-316R; VF_1789, MJM-317F and MJM-318R; VF_2161, MJM-319F and MJM-320R; VF_A0325, MJM-321F and MJM-322R; VF_A0448, MJM-323F and MJM-324R; and VF_A0677, MJM-325F and MJM-326R. The primer pairs also added XmaI and SphI restriction enzyme sites, which were used to clone the amplified products into the XmaI/SphI-digested pEVS122 using standard techniques. The resulting constructs were conjugated into V. fischeri ES114 (MJM1100 isolate) as previously described (33).

Plate-based chemotaxis assays.

For assessment of chemotaxis in soft agar, the strains were grown overnight and then spotted onto modified SWT that lacks glycerol (5 g of Bacto tryptone, 3 g of yeast extract, 8.8 g of NaCl, 6.2 g of MgSO4, 0.72 g of CaCl2, and 0.38 g of KCl/liter) supplemented with 1.5 mM serine and 0.35% agar as previously described (29). Plates were incubated at 28°C for 4 to 6 h, at which point 10 μl of each chemoattractant was spotted outside of the migrating rings. The chemoattractants were spotted at the following concentrations: 2 M serine, 1.1 M GlcNAc, 0.24 M (GlcNAc)2, 0.17 M N-acetylneuraminic acid (NANA), 4.8 M thymidine, and 1 M glucose.

Screening for inner-ring migration defects and transposon insertion site identification.

We selected five 96-well plates from the MB collection of V. fischeri transposon mutants (Brennan et al., unpublished). These strains were inoculated into 100 μl of SWT buffered with 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), directly from frozen stocks, and grown overnight. Omnitrays (Nunc, Rochester, NY) containing SWT 0.3% agar supplemented with 1.5 mM serine were inoculated, in duplicate, with 1 μl of each overnight culture using a 96-pin replicator (V&P Scientific, San Diego, CA). Soft-agar plates were then incubated at 28°C for 4 to 6 h and examined for altered inner-ring migration. Candidate strains were further examined by inoculation into individual SWT-serine soft-agar plates, which were subsequently incubated at room temperature (23 to 24°C) for ∼12 h.

The insertion site of the validated candidate vfcA::Tnerm mutant, MB09076, was identified using arbitrarily primed PCR as previously described (Brennan et al., unpublished) (34, 35). Briefly, the transposon junction site was amplified from a diluted overnight culture in two successive rounds of PCR using primer sets ARB1/170Ext3, followed by ARB2/170Int3 (Table 2). The sample was submitted for sequencing to the DNA Sequencing Center at the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center (Madison, WI) with primer 170Seq1. Analysis of the sequencing results was performed with DNASTAR (Madison, WI) Lasergene Seqman software.

Capillary chemotaxis assay.

Strains were grown in SWT liquid medium to an optical density at 600 nm of ∼0.3, pelleted gently for 5 min at 800 × g, and resuspended in buffered artificial seawater (H-ASW: 100 mM MgSO4, 20 mM CaCl2, 20 mM KCl, 400 mM NaCl, and 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5]) (36). One-microliter capillary tubes (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA) were sealed at one end, filled with either H-ASW alone or H-ASW containing the indicated attractant, and inserted into microcentrifuge tubes containing the cell suspension. The tubes were incubated on their side for 5 min at room temperature (23 to 24°C), after which the capillary tubes were removed from the cell suspension and washed. The contents were expelled into 150 μl of buffer (either H-ASW or 70% Instant Ocean), and dilutions were plated for colony counts on LBS plates.

Construction of vfcA complementation plasmid.

The vfcA ORF and 350 bp upstream were amplified by PCR using the primer pair 0777compF and 0777compR (Table 2) and cloned into the SphI/KpnI-digested fragment of pVSV105 (37) according to standard molecular techniques. Both the complementation construct and the vector control were conjugated into wild-type V. fischeri and into the vfcA::Tnerm mutant using the standard technique (33).

Squid colonization assay.

Newly hatched squid were colonized by exposure to ∼3,000 CFU of the indicated strain(s)/ml in 100 ml of filter-sterilized Instant Ocean (FSIO) for 3 h. Squid were then transferred to vials containing 4 ml of uninoculated FSIO for an additional 18 to 21 h, at which point they were euthanized and surface sterilized by storage at −80°C. Individual squid were then homogenized, and each homogenate was diluted and plated for colony counts on LBS agar according to standard methods (38). In competitive colonization experiments, 100 colonies were then patched onto LBS plates supplemented with erythromycin to determine the ratio of the vfcA::Tnerm mutant to wild type. The competitive index (CI) for each individual squid is calculated as the log10[(homogenate mutant CFU/wild-type CFU)/(inoculum mutant CFU/wild-type CFU)].

RESULTS

Generation and initial characterization of MCP mutants.

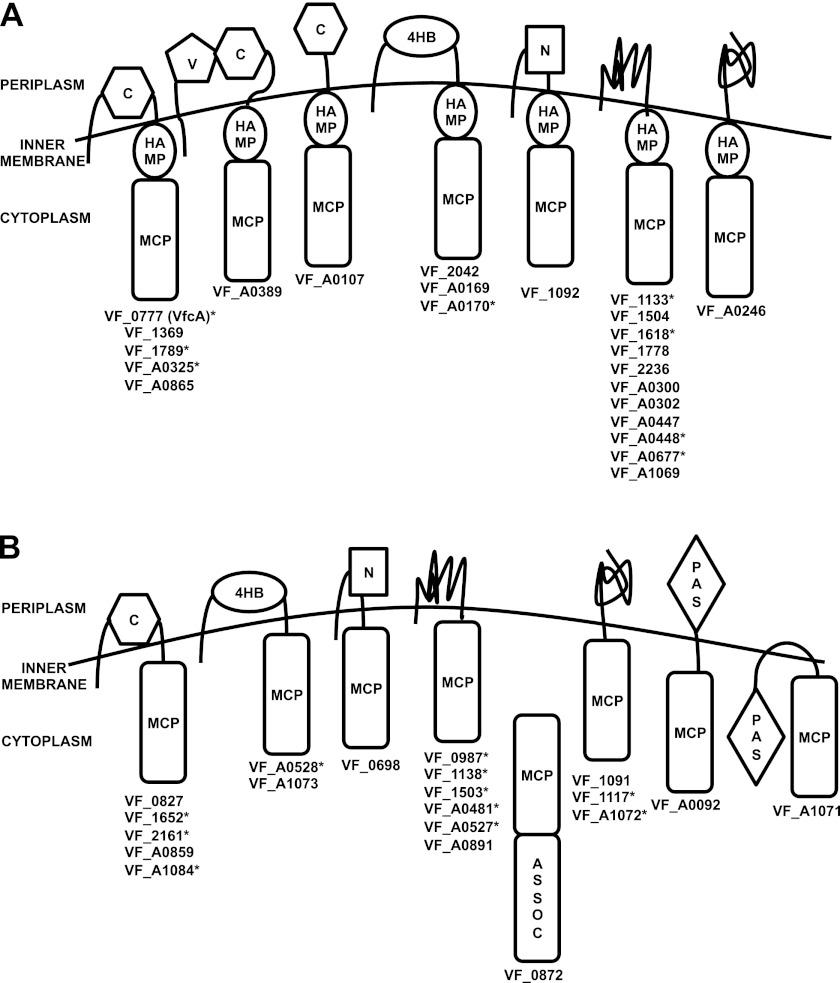

The V. fischeri ES114 genome (22, 23) encodes 43 predicted MCPs. Our preliminary analyses included BLAST (39) queries with full-length proteins and with the N-terminal sensing domains against characterized chemoreceptors in other organisms; however, this approach did not yield ligand-specific signatures. Categorization by domain structure (Fig. 1) revealed four domain architectures that were common to at least five V. fischeri MCPs, and an additional 11 architectures represented in the genome. Because it appeared that many of the MCPs could be functional for chemotaxis signal transduction, we took an empirical approach to identifying whether mutants in MCP genes exhibited chemotaxis defects during an initial screen in a rich-medium soft-agar assay. We identified 12 mutants disrupted in MCP-encoding genes by PCR analysis of a transposon mutant collection as described in Materials and Methods (Table 1, Fig. 1). We also constructed plasmid-integration (Campbell-type) mutants in seven other MCP genes that were not identified by this method (Table 1, Fig. 1). Six of these seven specific target genes (VF_0777 [vfcA], VF_1133, VF_1789, VF_A0325, VF_A0448, and VF_A0677) were selected as candidates because of evidence they might be regulated under conditions relevant to symbiosis: vfcA, VF_1789, VF_A0325, and VF_A0677 were regulated by the flagellar master regulator FlrA in a transcriptomic study (Brennan et al., unpublished), vfcA is regulated by the AinS C8-homoserine lactone autoinduction pathway that exhibits squid initiation and maintenance phenotypes (40), and VF_A0448 and VF_1133 were activated when grown in either GlcNAc or (GlcNAc)2, respectively (A. Schaefer and E. Ruby, unpublished data). The final directed mutant we analyzed, VF_2161::pCAB18, was constructed with an insertion in a gene whose N-terminal sensing domain was highly similar to the V. cholerae gene encoded by VC_0449, which, when mutated, has been reported to reduce chemotaxis toward GlcNAc and (GlcNAc)2 (20).

Fig 1.

Representation of MCP domain-containing proteins in V. fischeri with (A) or without (B) predicted HAMP domains. The predicted domain structures of the 43 MCP domain-containing proteins were determined by Pfam and TmHMM analyses (47, 48). In each model, the N terminus is oriented to the upper left, and the C terminus is marked by the MCP domain, except in the case of VF_0872, in which the ASSOC domain is C terminal. Asterisks indicate loci in which a mutant in the corresponding gene has been identified and analyzed in the present study. Abbreviations: MCP, MCP signal domain; HAMP, HAMP domain; C, CACHE_1 or CACHE_2 domain; V, MCP_N domain; 4HB, 4HB_MCP_1 domain; N, NIT domain; PAS, PAS_3 or PAS_9 domain; ASSOC, MCP-signal associated domain (49–54).

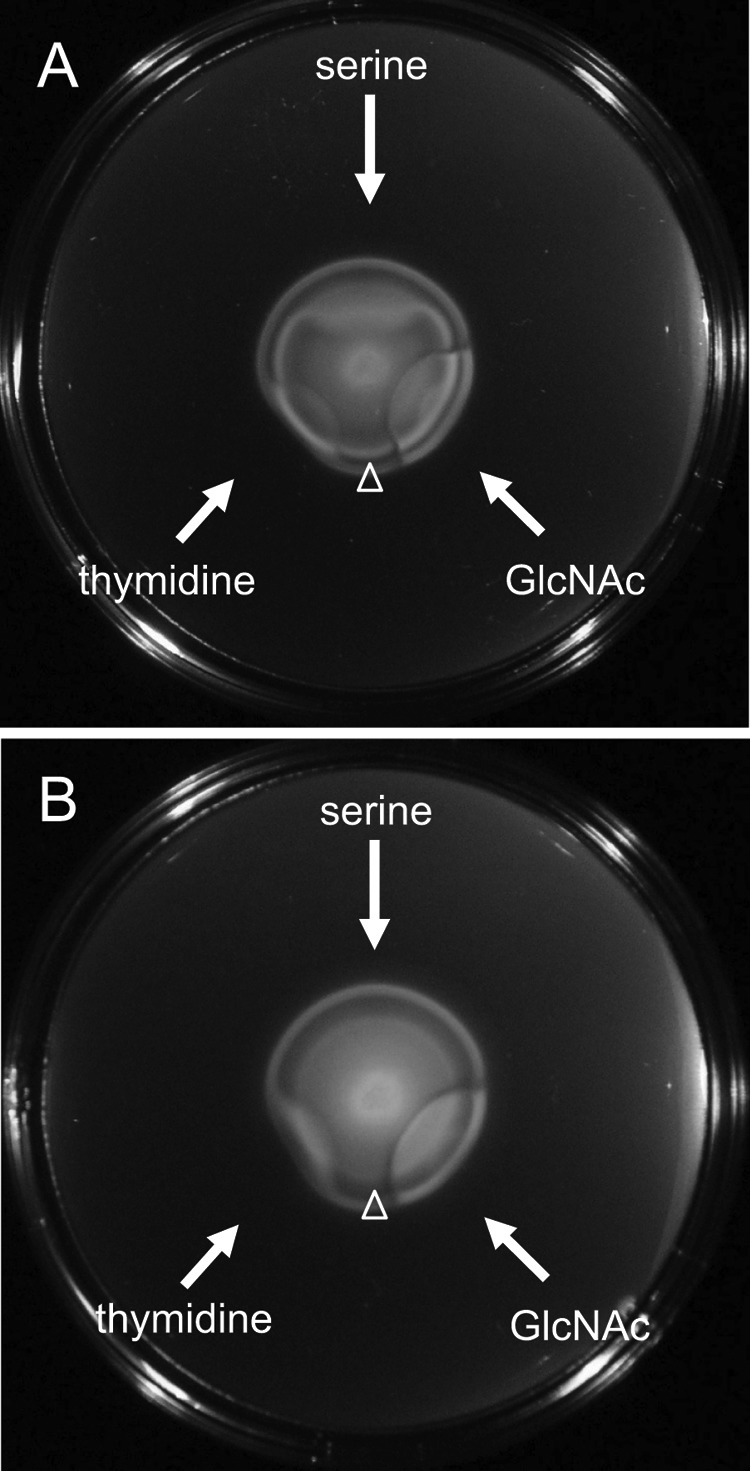

All 19 of these mutant strains, as well as wild-type V. fischeri, were assayed for responses to glucose, serine, GlcNAc, (GlcNAc)2, NANA, and thymidine in plate-based assays, as previously described (28, 29). Only one strain exhibited an altered chemotactic response to any of the assayed chemoattractants. The mutant disrupted in VF_0777 (henceforth referred to as vfcA for V. fischeri chemoreceptor A) did not respond to exogenous serine but exhibited wild-type responses to the other chemoattractants (Fig. 2 and data not shown). It has been shown previously that, on SWT soft-agar plates, the outer ring of motile V. fischeri cells swim toward thymidine and the inner ring of cells swim toward serine (29). As shown in Fig. 2B, the vfcA::pCAB15 mutant's inner ring did not exhibit the robust response to the addition of serine that is observed in wild-type cells (Fig. 2A). Together, the mutant's lack of response to exogenous serine and its lack of a robust serine ring suggested that VfcA plays a role in mediating serine chemotaxis in V. fischeri.

Fig 2.

Responses of the wild type and the vfcA::pCAB15 mutant to exogenous chemoattractants. Wild-type (MJM1100) (A) and vfcA::pCAB15 mutant (CAB1500) (B) cells were inoculated into SWT-serine soft-agar plates and incubated at 28°C for 5 h, at which time chemoattractants (serine, thymidine, or GlcNAc) were spotted (as indicated by arrows) and allowed to incubate an additional 2 h. Open arrowheads mark migration of the inner ring. Chemoattraction to the provided compound manifests as a disruption of the migrating cells.

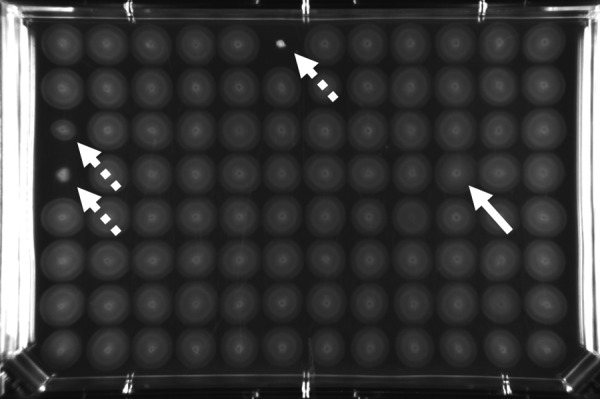

We next conducted a screen for transposon insertion mutants that lacked an inner migration ring, since we reasoned that such a screen would yield insertions in vfcA or in genes that modulated other aspects of serine chemotaxis. We screened 480 transposon mutants in serine-supplemented SWT soft agar and isolated a single candidate, MB09076, which did not have an obvious inner ring (Fig. 3). The transposon insertion site was identified by arbitrarily primed PCR and determined to be within the vfcA ORF. Identification of an independent allele of vfcA that exhibited the same phenotypes as the Campbell allele supported our hypothesis that VfcA was linked to the formation of the inner migration ring. Future experiments were conducted with the vfcA::Tnerm mutant to avoid the possibility of reversion from the plasmid integration mutation.

Fig 3.

Screening for altered inner-ring migration in soft-agar motility plates. A representative SWT-serine soft-agar plate inoculated with 96 transposon mutants from the MB collection, as described in the Materials and Methods, and incubated for 4 to 6 h at 28°C. The vfcA::Tnerm mutant (MB09076; white arrow) was identified since its migration pattern lacked a well-organized inner ring. This was straightforward to identify visually compared to the surrounding cells, all of which displayed the ring. Also evident on the plate are strains with reduced or no soft-agar motility (dashed arrows), which were not examined further for the present study.

Examination of chemotaxis behavior by capillary assay.

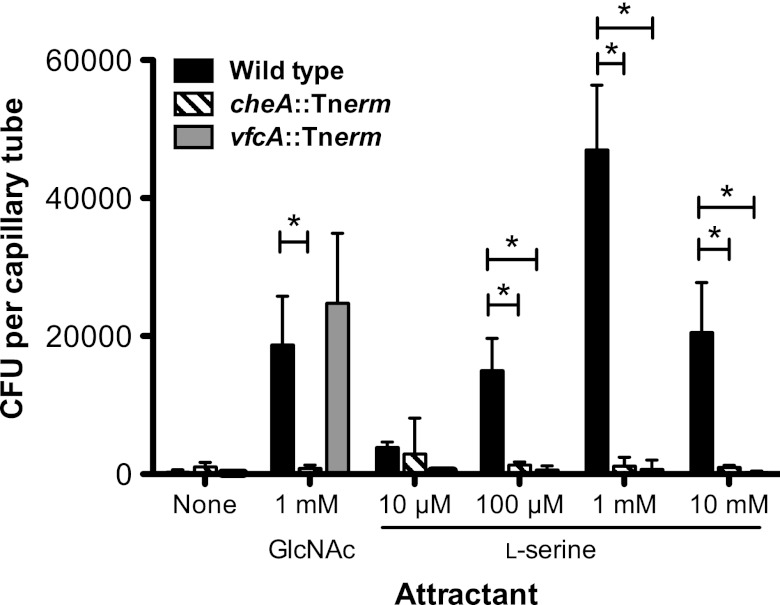

Plate-based chemotaxis assays are indirect and require not only flagellar motility and chemotaxis but also utilization of putative attractants to generate a gradient (41, 42). Therefore, we performed a capillary chemotaxis assay to directly test whether VfcA plays a role in serine chemotaxis. This assay has not previously been used to examine chemotaxis behavior in V. fischeri. In this assay, wild-type V. fischeri responded strongly to serine and GlcNAc, a structurally distinct chemoattractant used as a positive control (Fig. 4). The vfcA::Tnerm mutant responded only to 1 mM GlcNAc and did not respond to any of the tested serine concentrations. As expected, a nonchemotactic cheA::Tnerm mutant, isolated from another study (Brennan et al., unpublished) also did not migrate toward any of the chemoattractants.

Fig 4.

Responses to serine and GlcNAc in a capillary chemotaxis assay. The chemotactic responses of the wild type, the cheA::Tnerm mutant (MB08701), and the vfcA::Tnerm (MB09076) mutant to various concentrations of serine and 1 mM GlcNAc were measured by a capillary chemotaxis assay. The data represent the means and standard errors of the mean (SEM) of three independent assays performed in duplicate. Asterisks indicate significance at a P value of <0.01, as determined by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Bonferroni correction.

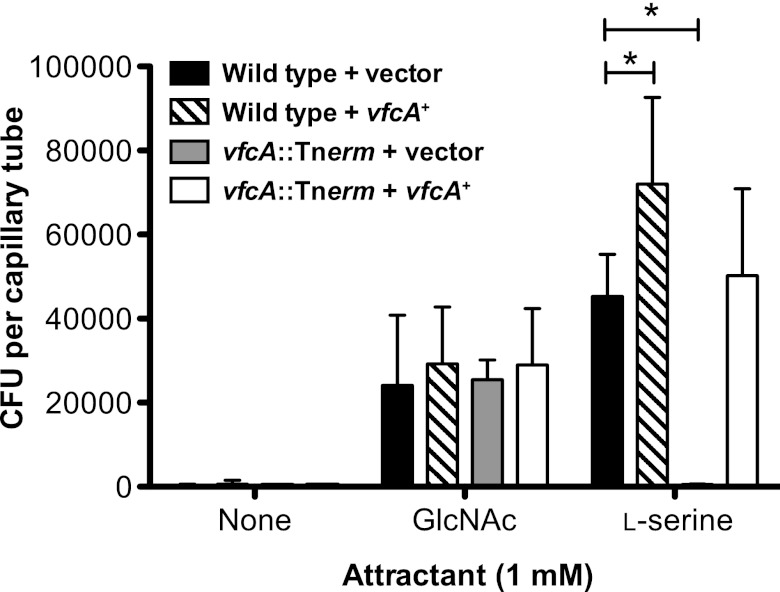

We then examined whether the phenotype of the vfcA::Tnerm mutant could be complemented by expression of a wild-type copy of vfcA in trans. As shown in Fig. 5, the chemotaxis response toward serine in the vfcA::Tnerm strain was restored upon heterologous expression of vfcA, supporting that it is the VfcA gene product that mediates the serine attraction. Expression of vfcA in wild-type V. fischeri conferred an enhanced chemotaxis response toward serine but not GlcNAc (Fig. 5), further supporting a role for VfcA in mediating chemotaxis toward serine (Fig. 2 and 4). Together, these data suggested that vfcA encodes the serine chemoreceptor in V. fischeri, which is functionally analogous to tsr in E. coli.

Fig 5.

VfcA complementation as assayed by the capillary chemotaxis assay. The chemotactic responses of wild type harboring the vector control (CAB1516), wild type harboring the vfcA complementation construct (CAB1517), the vfcA::Tnerm mutant harboring the vector control (CAB1523), and the vfcA::Tnerm mutant harboring the vfcA complementation construct (CAB1524) to 1 mM GlcNAc or 1 mM l-serine were measured by a capillary chemotaxis assay. The data represent the means and SEM of three independent assays performed in duplicate. A single asterisk indicates a P of <0.01, as determined by two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction.

Because MCPs can sense multiple chemoattractants, we then investigated whether VfcA mediates chemotaxis toward other amino acids in V. fischeri. Previous work using plate-based assays showed that wild-type V. fischeri responded most strongly to serine and, to a lesser extent, alanine, arginine, asparagine, histidine, and threonine (29). Again, soft-agar assays report on a combination of growth and chemotaxis phenotypes. We therefore applied our capillary assay to quantify the wild-type chemotaxis repertoire across all 20 amino acids (Table 3). We observed strong attraction (>5 × 103 CFU/capillary) to 1 mM concentrations of serine, cysteine, threonine, and alanine (Table 3). These responses were not observed in the vfcA mutant, suggesting that VfcA mediates chemotaxis toward each of these four amino acids. We also noticed that the vfcA mutant showed increased chemotaxis toward the aromatic hydrophobic amino acids (phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan) compared to wild-type V. fischeri.

Table 3.

Normalized chemotactic responses of wild-type and vfcA::Tnerm mutant strains to 1 mM l-amino acids

| Amino acid classification | Attractant | Mean CFU (×103)/capillary tube ± SEMa |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | vfcA::Tnerm mutant | ||

| Polar (basic) | Arginine | BD | 0.8 ± 0.5 |

| Histidine | BD | BD | |

| Lysine | BD | BD | |

| Polar (acidic) | Aspartic acid | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.8 |

| Glutamic acid | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | |

| Polar (neutral) | Serine | 55.6 ± 2.8 | BD |

| Cysteine | 78.3 ± 12.3 | BD | |

| Threonine | 22.0 ± 6.2 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | |

| Asparagine | BD | 3.0 ± 3.2 | |

| Glutamine | 0.2 ± 0.2 | BD | |

| Methionine | 0.4 ± 0.2 | BD | |

| Hydrophobic (aliphatic) | Alanine | 8.0 ± 2.1 | BD |

| Valine | BD | 1.4 ± 0.8 | |

| Isoleucine | BD | BD | |

| Leucine | BD | BD | |

| Hydrophobic (aromatic) | Phenylalanine | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.6 |

| Tyrosine | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 11.5 ± 5.1 | |

| Tryptophan | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 9.3 ± 2.3 | |

| Unique | Glycine | 0.3 ± 0.1 | BD |

| Proline | 0.4 ± 0.3 | BD | |

Values represent the means of four independent assays performed in duplicate and normalized by the subtraction of no-attractant controls. BD, below detection (0.1 × 103 adjusted CFU/capillary tube). Bold indicates significance compared to no-attractant controls (0 adjusted CFU/capillary tube) at P < 0.05, as determined by one-tailed Student t test.

Squid colonization.

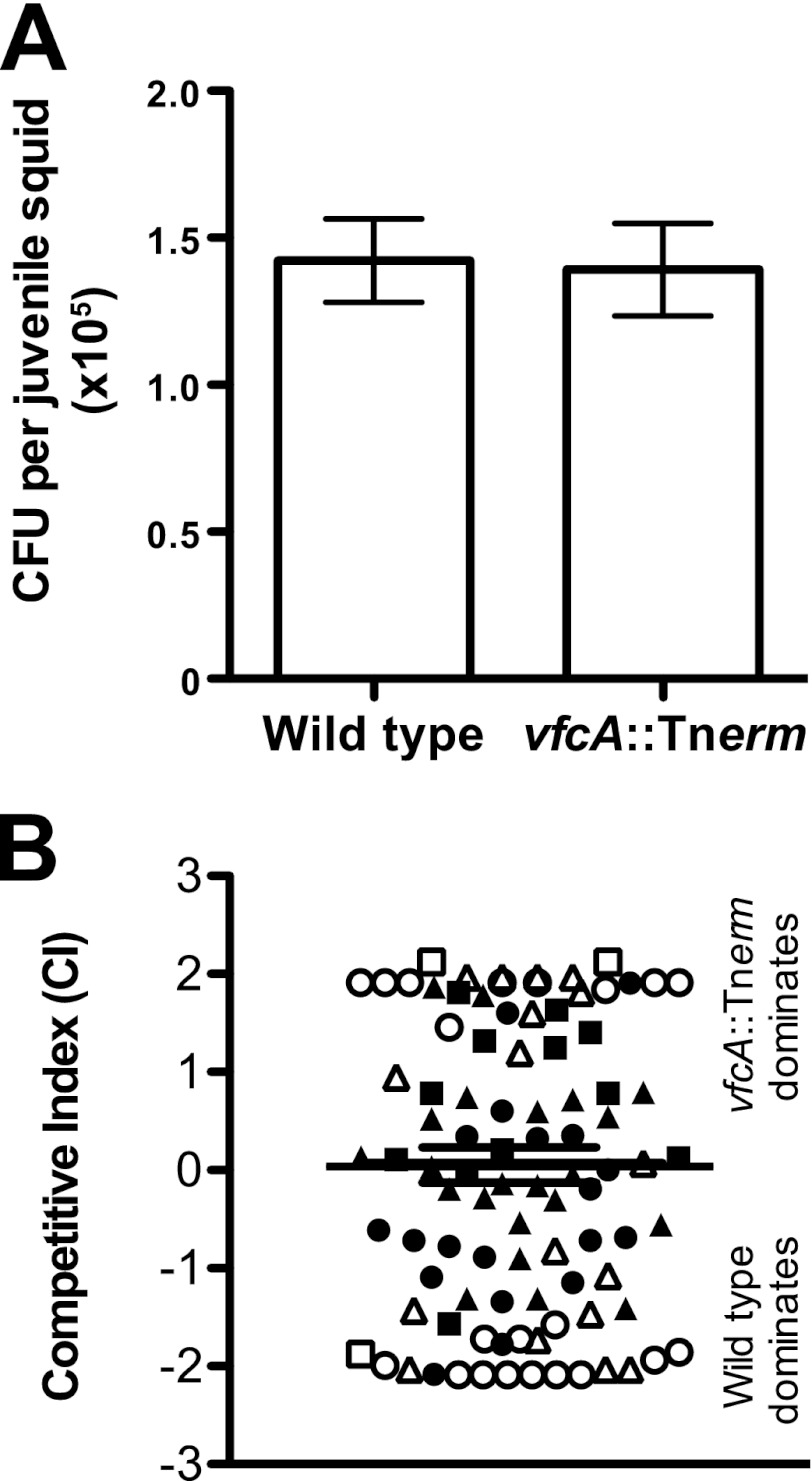

Chemotaxis is important during squid colonization (24, 25) and host amino acids are critical to successful colonization by V. fischeri (43). Strains that are nonmotile are unable to colonize (25, 27), and nonchemotactic strains colonize inefficiently (24, 25). Because VfcA mediates essentially all of the significant amino acid chemotaxis in V. fischeri (Table 3), the vfcA mutant permitted us to test whether host-derived amino acids served as a signal for colonizing V. fischeri to locate their symbiotic niche. Our prediction was that, if amino acid chemoattraction is developmentally relevant, then the vfcA strain would exhibit a squid colonization defect. We colonized juvenile Euprymna scolopes with culture-grown wild-type and vfcA::Tnerm strains, either individually (single-strain colonization) or in a competitive colonization assay. In the single-strain assays, wild-type and mutant strains each colonized to comparable levels (Fig. 6A). Similarly, in competition, we observed a neutral competition phenotype, so this result did not indicate any competitive advantage or disadvantage for the mutant (Fig. 6B).

Fig 6.

Single-strain and competitive colonization of juvenile squid. (A) Bacterial levels after 24 h in squid exposed to either wild type (MJM1100) or vfcA::Tnerm (MB09076) from three independent experiments, representing a total of 80 squid per condition. Starting inoculum levels ranged from 2,300 to 4,200 CFU/ml. (B) Competitive index (CI) values of squid exposed to both wild type (MJM1100) and vfcA::Tnerm (MB09076). Different symbols (circles, triangles, and squares) represent animals from different experiments (inocula, 2,400 to 4,400 CFU/ml). Open markers indicate squid in which only one strain was detected. Bars indicate means ± the SEM, as determined for all squid in which both strains were observed.

DISCUSSION

The main contributions from this study are as follows. (i) Using a capillary assay for the quantification of chemoattraction for the first time in V. fischeri, we probed the amino acid chemotaxis response of wild-type V. fischeri and revealed strong attraction to cysteine, serine, threonine, and alanine. (ii) Analyzing mutants disrupted in individual predicted MCP-encoding genes, we identified one MCP, VfcA, that mediates chemotaxis toward a wide range of amino acids. (iii) The vfcA mutant colonizes squid as effectively as wild-type V. fischeri, both alone and in competition.

A number of studies have examined flagellar motility and chemotaxis in V. fischeri (24–26, 28, 29). Chemotaxis experiments in these works have relied on soft-agar motility assays. Our work has affirmed conclusions in those studies (e.g., chemotaxis toward serine), and the capillary chemotaxis assay provides the ability to assay chemotaxis in liquid medium without confounding factors such as growth (42). This technique allowed us to examine chemotaxis toward all 20 standard amino acids. In the wild-type strain, we measured significant chemotaxis toward nine of these amino acids, and this technique can now be applied to other relevant macromolecules in V. fischeri.

We mutated 19 of the 43 putative V. fischeri MCPs and found that only the vfcA mutant exhibited detectable chemotactic defects to any of the six V. fischeri chemoattractants tested. Using the capillary chemotaxis assay, we showed that the vfcA mutant does not exhibit strong chemotaxis toward serine, cysteine, threonine, and alanine. Since we observed no alteration in the vfcA mutant's ability to respond toward the structurally distinct chemoattractant GlcNAc, we attribute the amino acid phenotypes to specific signal transduction through VfcA rather than to pleiotropic effects on chemotaxis overall. Furthermore, the mutant displays 5- to 10-fold-enhanced attraction toward aromatic amino acids phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan. These data may indicate either that such aromatic amino acids act directly as VfcA-mediated chemorepellents or that the loss of VfcA enhances recognition of this class of amino acids, perhaps by biasing the highly organized structure of MCP arrays (44).

Amino acids, including alanine and serine, are found in the squid light organ environment at micromolar concentrations (43), and we hypothesized that these amino acids could serve as a chemotactic signal during symbiotic initiation. However, the vfcA mutant did not exhibit a colonization defect. Since vfcA mutants are defective in essentially all of the major amino acid chemotaxis responses observed in wild type, we conclude that amino acid chemotaxis is not relevant for the colonizing symbiont to be directed into the its symbiotic niche. An alternate interpretation of the colonization data is that the mutant's enhanced chemoattraction toward aromatic amino acids mediates symbiotic colonization through a distinct pathway from wild-type V. fischeri; however, it is more parsimonious that amino acid chemotaxis does not play a significant role in bacterial migration into the light organ.

We characterized here the first identification of MCP-chemoattractant pairing in V. fischeri. This could not have been predicted by sequence alone, since BLASTP comparison of the ligand-binding domain from the E. coli serine-sensing chemoreceptor, Tsr, to the ES114 proteome does not yield a single MCP within the significant hits. In addition, recent work identified a distinct MCP in V. cholerae, named Mlp24/McpX, that mediates chemotaxis toward multiple amino acids (21). It is not yet known whether amino acid chemotaxis appears elsewhere among the other 42 MCP-domain encoding proteins of V. fischeri such as the McpX ortholog.

Although we identified an amino acid chemoreceptor in V. fischeri, the genetic basis for chemotaxis by the bacterium toward the other tested chemoattractants remains elusive. Since we identified mutants in only 44% of the MCPs, it is possible that these behaviors are mediated by the remaining chemoreceptors and could be clarified by continuing to construct single MCP mutants. However, functional redundancy or masking by other behaviors (i.e., energy taxis) could similarly prevent chemoreceptor-ligand identification (15). Alternative approaches may be needed to uncover these relationships. Interestingly, vfcA is one of only four MCP genes that are regulated by the flagellar master activator FlrA in V. fischeri (Brennan et al., unpublished). As such, it resembles the five E. coli MCPs that are all part of the flagellar regulon (45). Identifying such characteristics that show similarity to the canonical MCPs in E. coli may suggest an initial filter for chemoreceptors that mediate general (e.g., amino acid) chemoattraction, rather than lifestyle-specific chemotactic responses that might require specific induction (46).

The present study and other recent works (24, 28; Brennan et al., unpublished) have expanded the tools available for studying chemotaxis and motility in V. fischeri, including large-scale mutant availability and chemoattractant disruption in the host. Since there is evidence that chemoattraction to the carbohydrate N,N′-diacetylchitobiose is relevant during squid colonization (28), it will be of interest to apply these methods to examine the genetic basis for V. fischeri sensing of other chemoattractants. Although the chemoattractant-chemoreceptor networks in bacterial species that encode high numbers of MCPs are still poorly understood, our work suggests that V. fischeri may serve as a valuable model for characterizing the relevant roles of MCPs in mediating both planktonic and symbiotic chemotactic signals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Edward Ruby, Erica Raterman, and Ashleigh Janiga for helpful discussions and experimental assistance.

This study was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) grant IOS-0843633 (M.J.M.), NSF grant IOS-0843370 (C.R.D.-M.), and NSF grant IOS-0841507 and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant RR12294 (to Margaret McFall-Ngai and Edward Ruby). C.A.B. was supported by an NIH Molecular Biosciences Training Grant and an NIH Microbes in Health and Disease Training Grant to the University of Wisconsin-Madison. C.R.D.-M. was also supported by a Pott Foundation Summer Research Fellowship and a Faculty Research and Creative Works Award through the University of Southern Indiana.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Henrichsen J. 1972. Bacterial surface translocation: a survey and a classification. Bacteriol. Rev. 36:478–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adler J. 1966. Chemotaxis in bacteria. Science 153:708–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Larsen SH, Reader RW, Kort EN, Tso WW, Adler J. 1974. Change in direction of flagellar rotation is the basis of the chemotactic response in Escherichia coli. Nature 249:74–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stock JB, Surette MG. 1996. Chemotaxis, p 1103–1129 In Neidhart FC, Ingraham JI, Lin ECC, Low KB, Magasanik B, Reznikoff WS, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger HE. (ed), Escherichia coli and Salmonella, 2nd ed ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bibikov SI, Biran R, Rudd KE, Parkinson JS. 1997. A signal transducer for aerotaxis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:4075–4079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hazelbauer GL, Mesibov RE, Adler J. 1969. Escherichia coli mutants defective in chemotaxis toward specific chemicals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 64:1300–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Springer MS, Goy MF, Adler J. 1977. Sensory transduction in Escherichia coli: two complementary pathways of information processing that involve methylated proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 74:3312–3316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Manson MD, Blank V, Brade G, Higgins CF. 1986. Peptide chemotaxis in Escherichia coli involves the Tap signal transducer and the dipeptide permease. Nature 321:253–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kondoh H, Ball CB, Adler J. 1979. Identification of a methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein for the ribose and galactose chemoreceptors of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76:260–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Porter SL, Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. 2008. Rhodobacter sphaeroides: complexity in chemotactic signalling. Trends Microbiol. 16:251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zusman DR, Scott AE, Yang Z, Kirby JR. 2007. Chemosensory pathways, motility and development in Myxococcus xanthus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:862–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lacal J, Garcia-Fontana C, Munoz-Martinez F, Ramos JL, Krell T. 2010. Sensing of environmental signals: classification of chemoreceptors according to the size of their ligand binding regions. Environ. Microbiol. 12:2873–2884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krell T, Lacal J, Munoz-Martinez F, Reyes-Darias JA, Cadirci BH, Garcia-Fontana C, Ramos JL. 2011. Diversity at its best: bacterial taxis. Environ. Microbiol. 13:1115–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miller LD, Russell MH, Alexandre G. 2009. Diversity in bacterial chemotactic responses and niche adaptation. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 66:53–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alvarez-Ortega C, Harwood CS. 2007. Identification of a malate chemoreceptor in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by screening for chemotaxis defects in an energy taxis-deficient mutant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7793–7795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kato J, Kim HE, Takiguchi N, Kuroda A, Ohtake H. 2008. Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a model microorganism for investigation of chemotactic behaviors in ecosystem. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 106:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Taguchi K, Fukutomi H, Kuroda A, Kato J, Ohtake H. 1997. Genetic identification of chemotactic transducers for amino acids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 143:3223–3229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim HE, Shitashiro M, Kuroda A, Takiguchi N, Ohtake H, Kato J. 2006. Identification and characterization of the chemotactic transducer in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 for positive chemotaxis to trichloroethylene. J. Bacteriol. 188:6700–6702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boin MA, Hase CC. 2007. Characterization of Vibrio cholerae aerotaxis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 276:193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meibom KL, Li XB, Nielsen AT, Wu CY, Roseman S, Schoolnik GK. 2004. The Vibrio cholerae chitin utilization program. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:2524–2529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nishiyama S, Suzuki D, Itoh Y, Suzuki K, Tajima H, Hyakutake A, Homma M, Butler-Wu SM, Camilli A, Kawagishi I. 2012. Mlp24 (McpX) of Vibrio cholerae implicated in pathogenicity functions as a chemoreceptor for multiple amino acids. Infect. Immun. 80:3170–3178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ruby EG, Urbanowski M, Campbell J, Dunn A, Faini M, Gunsalus R, Lostroh P, Lupp C, McCann J, Millikan D, Schaefer A, Stabb E, Stevens A, Visick K, Whistler C, Greenberg EP. 2005. Complete genome sequence of Vibrio fischeri: a symbiotic bacterium with pathogenic congeners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:3004–3009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mandel MJ, Stabb EV, Ruby EG. 2008. Comparative genomics-based investigation of resequencing targets in Vibrio fischeri: focus on point miscalls and artifactual expansions. BMC Genomics 9:138 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. DeLoney-Marino CR, Visick KL. 2012. Role for cheR of Vibrio fischeri in the Vibrio-squid symbiosis. Can. J. Microbiol. 58:29–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hussa EA, O'Shea TM, Darnell CL, Ruby EG, Visick KL. 2007. Two-component response regulators of Vibrio fischeri: identification, mutagenesis, and characterization. J. Bacteriol. 189:5825–5838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Graf J, Dunlap PV, Ruby EG. 1994. Effect of transposon-induced motility mutations on colonization of the host light organ by Vibrio fischeri. J. Bacteriol. 176:6986–6991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Millikan DS, Ruby EG. 2003. FlrA, a σ54-dependent transcriptional activator in Vibrio fischeri, is required for motility and symbiotic light-organ colonization. J. Bacteriol. 185:3547–3557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mandel MJ, Schaefer AL, Brennan CA, Heath-Heckman EA, DeLoney-Marino CR, McFall-Ngai MJ, Ruby EG. 2012. Squid-derived chitin oligosaccharides are a chemotactic signal during colonization by Vibrio fischeri. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:4620–4626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. DeLoney-Marino CR, Wolfe AJ, Visick KL. 2003. Chemoattraction of Vibrio fischeri to serine, nucleosides, and N-acetylneuraminic acid, a component of squid light-organ mucus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7527–7530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boettcher KJ, Ruby EG. 1990. Depressed light emission by symbiotic Vibrio fischeri of the sepiolid squid Euprymna scolopes. J. Bacteriol. 172:3701–3706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Studer SV, Mandel MJ, Ruby EG. 2008. AinS quorum sensing regulates the Vibrio fischeri acetate switch. J. Bacteriol. 190:5915–5923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dunn AK, Martin MO, Stabb EV. 2005. Characterization of pES213, a small mobilizable plasmid from Vibrio fischeri. Plasmid 54:114–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stabb EV, Ruby EG. 2002. RP4-based plasmids for conjugation between Escherichia coli and members of the Vibrionaceae. Methods Enzymol. 358:413–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Caetano-Anolles G. 1993. Amplifying DNA with arbitrary oligonucleotide primers. PCR Methods Appl. 3:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. O'Toole GA, Pratt LA, Watnick PI, Newman DK, Weaver VB, Kolter R. 1999. Genetic approaches to study of biofilms. Methods Enzymol. 310:91–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ruby EG, Nealson KH. 1976. Symbiotic association of Photobacterium fischeri with the marine luminous fish Monocentris japonica; a model of symbiosis based on bacterial studies. Biol. Bull. 151:574–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dunn AK, Millikan DS, Adin DM, Bose JL, Stabb EV. 2006. New rfp- and pES213-derived tools for analyzing symbiotic Vibrio fischeri reveal patterns of infection and lux expression in situ. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:802–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Naughton LM, Mandel MJ. 2012. Colonization of Euprymna scolopes squid by Vibrio fischeri. J. Vis. Exp. 61:e3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johnson M, Zaretskaya I, Raytselis Y, Merezhuk Y, McGinnis S, Madden TL. 2008. NCBI BLAST: a better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:W5–W9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lupp C, Ruby EG. 2005. Vibrio fischeri uses two quorum-sensing systems for the regulation of early and late colonization factors. J. Bacteriol. 187:3620–3629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wolfe AJ, Berg HC. 1989. Migration of bacteria in semisolid agar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:6973–6977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Parales RE, Harwood CS. 2002. Bacterial chemotaxis to pollutants and plant-derived aromatic molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Graf J, Ruby EG. 1998. Host-derived amino acids support the proliferation of symbiotic bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:1818–1822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Levit MN, Grebe TW, Stock JB. 2002. Organization of the receptor-kinase signaling array that regulates Escherichia coli chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 277:36748–36754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhao K, Liu M, Burgess RR. 2007. Adaptation in bacterial flagellar and motility systems: from regulon members to ‘foraging’-like behavior in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:4441–4452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Parales RE, Ditty JL, Harwood CS. 2000. Toluene-degrading bacteria are chemotactic towards the environmental pollutants benzene, toluene, and trichloroethylene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4098–4104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sonnhammer EL, Eddy SR, Durbin R. 1997. Pfam: a comprehensive database of protein domain families based on seed alignments. Proteins 28:405–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. 2001. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305:567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hanlon DW, Marquez-Magana LM, Carpenter PB, Chamberlin MJ, Ordal GW. 1992. Sequence and characterization of Bacillus subtilis CheW. J. Biol. Chem. 267:12055–12060 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Aravind L, Ponting CP. 1999. The cytoplasmic helical linker domain of receptor histidine kinase and methyl-accepting proteins is common to many prokaryotic signalling proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 176:111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Anantharaman V, Aravind L. 2000. Cache: a signaling domain common to animal Ca2+-channel subunits and a class of prokaryotic chemotaxis receptors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 25:535–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ulrich LE, Zhulin IB. 2005. Four-helix bundle: a ubiquitous sensory module in prokaryotic signal transduction. Bioinformatics 21(Suppl 3):iii45–iii48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shu CJ, Ulrich LE, Zhulin IB. 2003. The NIT domain: a predicted nitrate-responsive module in bacterial sensory receptors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28:121–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhulin IB, Taylor BL, Dixon R. 1997. PAS domain S-boxes in Archaea, Bacteria, and sensors for oxygen and redox. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:331–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hanahan D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]