Abstract

Benthic marine cyanobacteria are known for their prolific biosynthetic capacities to produce structurally diverse secondary metabolites with biomedical application and their ability to form cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms. In an effort to provide taxonomic clarity to better guide future natural product drug discovery investigations and harmful algal bloom monitoring, this study investigated the taxonomy of tropical and subtropical natural product-producing marine cyanobacteria on the basis of their evolutionary relatedness. Our phylogenetic inferences of marine cyanobacterial strains responsible for over 100 bioactive secondary metabolites revealed an uneven taxonomic distribution, with a few groups being responsible for the vast majority of these molecules. Our data also suggest a high degree of novel biodiversity among natural product-producing strains that was previously overlooked by traditional morphology-based taxonomic approaches. This unrecognized biodiversity is primarily due to a lack of proper classification systems since the taxonomy of tropical and subtropical, benthic marine cyanobacteria has only recently been analyzed by phylogenetic methods. This evolutionary study provides a framework for a more robust classification system to better understand the taxonomy of tropical and subtropical marine cyanobacteria and the distribution of natural products in marine cyanobacteria.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, tropical and subtropical, benthic marine cyanobacteria have attracted much attention due to their extraordinary capacities to produce structurally diverse and highly bioactive secondary metabolites (1–4). These bioactive molecules deter grazers, are often potent toxins, and can underlie cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms (CyanoHABs) (5, 6). In marine environments, these toxic CyanoHABs are increasing globally in frequency and size by alarming rates and represent hazards to both human health and natural ecosystems (7, 8).

Despite their toxicity, many cyanobacterial secondary metabolites also have potential for a broad spectrum of pharmaceutical applications, such as anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and anti-infective applications (1, 2, 4, 9). In addition, many of these cyanobacterial secondary metabolites also have other potential commercial applications, such as insecticides, algaecides, and herbicides (10).

To date, an impressive 533 natural products (NPs) have been reported from marine strains of cyanobacteria (Marine Literature Database [http://www.chem.canterbury.ac.nz/marinlit/marinlit.shtml]). The taxonomic distribution of these NPs is, however, remarkably uneven, with over 90% of all of these molecules attributed to only five cyanobacterial genera (Marine Literature Database). Recently, with the inclusion of molecular phylogenetics in cyanobacterial taxonomy, our understanding of biodiversity in this group has drastically increased (11). For example, the NP-rich genus Lyngbya has been shown to be a polyphyletic group and composed of several phylogenetically distant and unrelated lineages (12, 13), and a wide variety of different molecules attributed to Lyngbya have been isolated from specimens of these different lineages (14). As a consequence of this polyphyly in the genus Lyngbya, one of these NP-rich marine lineages was recently recognized to be the novel genus Moorea (15). However, the taxonomy of other NP-rich groups of cyanobacteria and the general extent of novel biodiversity in tropical marine forms are currently unclear.

This study utilized a cladistic approach based on phylogenetic inference of small-subunit (SSU) rRNA genes to understand the biodiversity and taxonomic distribution of NPs in marine cyanobacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling.

Diverse samples of NP-producing, tropical, and subtropical benthic marine cyanobacteria were gathered from (i) recollection of environmental samples (collection information is available in Table S1 in the supplemental material) and chemical screening, (ii) cultures of NP-producing strains available from the Gerwick laboratory culture collection at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, (iii) genetically preserved specimens of published NP-producing strains, and (iv) phylogenetically analyzed NP-producing strains available in the literature. Recollections of cyanobacteria were performed by scuba, stand-up paddle boarding, or snorkeling. Meiofauna and macrofauna were cleaned off the samples under a dissecting scope in seawater filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size True Syringe filters (Grace Davison Discovery Science) before genetic or morphological analysis. Algal biomass (∼200 mg) was preserved for genetic analysis in 10 ml RNAlater (Ambion Inc.) and for morphological analysis in seawater with 5% formalin. Remaining biomass was frozen at −20°C and later freeze-dried for chemical analysis. Preliminary taxonomic identification of the specimens was performed in accordance with modern taxonomic systems (16, 17). Light microscopy was performed using a Leica epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Nikon Coolpix camera.

Natural product screening and characterization.

The algal biomass of each specimen was lyophilized and exhaustively extracted with ethyl acetate-methanol (MeOH) (1:1). The extract was dried under vacuum, and the dried residues were redissolved in MeOH at a concentration of 0.1 mg · ml−1. Each sample (10 μl) was injected into a liquid chromatography (LC) electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry (MS) system with an LTQ Advantage Max spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan) and separated on a reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) column (C18; 5 μm; 2.1 by 100 mm; Grace) with step gradient elution of 0.1% formic acid (FA) in water (eluent A) and 100% acetonitrile (eluent B). The gradient program was 0 to 22 min of 20 to 100% eluent B at a flow rate of 700 μl · min−1. The column temperature was kept at 30°C. The MS and tandem MS spectra and retention time of each peak were recorded using the positive and negative ion detection modes. Identification of secondary metabolites required support of predicted isotope patterns, corresponding tandem MS fragmentations, and conserved retention times (RTs) that were compared with those of previously characterized NPs. Proposed NPs which lacked standards for verifications were isolated by HPLC and characterized by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and high-resolution ESI-MS. 1H NMR data were obtained on a JEOL 600-MHz spectrometer.

Gene sequencing.

Genomic DNA was extracted from cultures or genetically preserved biomass using a Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega) following the manufacturer's specifications. DNA concentration and purity were measured on an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The 16S rRNA genes were initially PCR amplified from isolated DNA using the cyanobacterium-specific primer set 106F and 1509R (18). The PCR volumes (25 μl) contained 1 μl (∼100 ng) of DNA, 5 μl of 5× Green GoTaq Flexi buffer, 2.5 μl MgCl2 (10 mM), 0.5 μl (10 mM) of a deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix, 1.0 μl of each primer (10 μM), 0.25 μl of GoTaq DNA polymerase (5 U · μl−1), and 14.75 μl of distilled H2O. The PCRs were performed in a DNA Engine Dyad Peltier thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) as follows: initial denaturation for 2 min at 95°C, 25 to 28 cycles of 45 s at 95°C, 45 s at 50°C, and 2 min at 72°C, and a final elongation for 3 min at 72°C. PCR products were analyzed on a (1%) agarose gel in TAE (Tris-acetate-EDTA) buffer and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The PCR products were purified using a MinElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen) before subcloning using a pGEM-T Easy vector system (Promega) following the manufacturer's specifications. Plasmid DNA was isolated using a QIAprep spin miniprep kit (Qiagen) and sequenced with M13 primers, as well as additional internal primers 785R and 359F (18). Multiple (>4) clones were sequenced from each clone library. Sequencing was performed at the Laboratories of Analytical Biology of the National Museum of Natural History.

Phylogenetic inferences.

The SSU rRNA gene sequences obtained by sequencing were complemented with sequence data available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) web page (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Taxonomic reference strains (indicated by R) were selected from Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (16), and the type strains (indicated by T) were selected from CyanoDB (J. Komárek and T. Hauer, CyanoDB.cz: the on-line database of cyanobacterial genera, 2011 [http://www.cyanodb.cz]). Gene sequences of <1,250 bp were removed in the phylogenetic analysis (all gene sequences are available in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Uncorrected gene sequence divergence (i.e., the p distance) was determined by the pairwise distance calculation without model selection in the MEGA (version 5.1) program (19). Only monophyletic clades were accepted, and the thresholds for indication of novel genera and species were set to 95% and 97% uncorrected 16S rRNA gene sequence similarities, respectively. Chimeric gene sequences were predicted using Pintail software with the cutoff size set at >600 bp (20) and were manually confirmed by comparison of neighbor-joining phylograms for different regions (>300 bp) of the sequences. The unicellular organism Gloeobacter violaceus PCC 7421 (GenBank accession no. NC005125) was included as an evolutionarily distant outgroup. Gene sequences were aligned using the MUSCLE algorithm (21). The best-fitting nucleotide substitution models optimized by maximum likelihood (ML) were compared and selected using the uncorrected/corrected Akaike information criterion, Bayesian information criterion, and the decision theoretic in the jModeltest (version 0.1.1) program (22). The evolutionary histories of the cyanobacterial genes were inferred using ML and Bayesian inference algorithms. The ML inference was performed using the RaxML program with 500 bootstrap replicates (23). Bayesian inference was conducted using MrBayes (version 3.1) software with four Metropolis-coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo chains (one cold and three heated) run for 1,000,000 generations (24).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences are available in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases, under accession numbers KC196263 to KC196268, KC222261 to KC222263, and KC207934 to KC207938 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Taxonomic identification of NP-producing marine cyanobacteria

| Natural product | Published identification | Clade | Strain | GenBank accession no. | Source (reference)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apratoxins A to C | Lyngbya majuscula | I | PNG5-198 | FJ041298 | Culture (25) |

| Apratoxin D | Lyngbya sordida | I | PNG5-194 | EU492877 | Literature (26) |

| Apratoxins F to G | Lyngbya bouillonii | I | PAL08-16 | GU111927 | Literature (27) |

| Barbamide | L. majuscula | I | NAC11-66 | KC196263 | Recollection |

| Carmabin A | L. majuscula | I | NAC11-66 | KC196263 | Recollection |

| Carmabin B | L. majuscula | I | 3L | EU315909 | Culture (14) |

| Carriebowmide | Lyngbya polychroa | I | BCBC11-14 | KC196264 | Recollection |

| Curacins A to C | L. majuscula | I | 3L | EU315909 | Culture (14) |

| Curacin D | L. majuscula | I | FK12-19 | KC196265 | Recollection |

| Curazole | L. majuscula | I | 3L | EU315909 | Culture (14) |

| Cyanolide A | L. bouillonii | I | PNG5-198 | FJ041298 | RNAlater (28) |

| Dechlorobarbamide | L. majuscula | I | 3L | EU315909 | Culture (14) |

| Dragonamides C to D | L. polychroa | I | FK12-19 | KC196265 | Recollection |

| Hectochlorin | L. majuscula | I | JHB | FJ151521 | Culture (29) |

| Jamaicamides A to C | L. majuscula | I | JHB | FJ151521 | Culture (30) |

| Lyngbyabellins A to C | L. bouillonii | I | VP417b | AY049751 | Literature (31) |

| Lyngbyapeptins A to C | L. bouillonii | I | VP417b | AY049751 | Literature (31) |

| Palau'imide | L. bouillonii | I | VP417b | AY049751 | Literature (31) |

| Palmyramide A | L. majuscula | I | PAL08-17-08-2 | GQ231522 | Literature (32) |

| Ulongamides A to F | Lyngbya sp. | I | NIH309 | AY049752 | Literature (31) |

| (−)-trans-7S-Methoxy tetradocenoic acid | L. majuscula | II | NAC11-70 | KC196266 | Recollection |

| Coibacins A to D | cf.b Oscillatoria sp. | II | PAC-18-FEB-10-1 | JQ899056 | Literature (33) |

| Dolastatin 12 | L. majuscula | II | NAB11-47 | KC196267 | Recollection |

| Ethyltumonoate A | cf. Oscillatoria margaritifera | II | NAC8-46 | GU724197 | Literature (34) |

| Grassypeptolides A to C | Lyngbya cf. confervoides | II | FK12-17 | KC196268 | Recollection |

| Grassystatins A and B | L. cf. confervoides | II | FK12-17 | KC196268 | Recollection |

| Lyngbyastatins 1, 3 | L. majuscula | II | PNG05-4 | EU253968 | Literature (35) |

| Lyngbyatoxin A | L. majuscula | II | Pago 2 | AF510963 | Literature (31) |

| Majusculamides A and B | L. majuscula | II | Cocos 3 | AF510966 | Literature (31) |

| Malyngamides A-B | L. majuscula | II | Cocos 3 | AF510966 | Literature (31) |

| Malyngamide C | L. majuscula | II | NAC11-70 | KC196266 | Recollection |

| Malyngamide C acetate | L. majuscula | II | NAC11-70 | KC196266 | Recollection |

| Methyltumonoates A and B | L. majuscula | II | NAB11-47 | KC196267 | Recollection |

| Microcolins A and B | L. majuscula | II | FFP12-1 | KC207934 | Recollection |

| Pitiamide A | Lyngbya semiplena | II | AF510982 | Literature (31) | |

| Pitipeptolides A and F | L. majuscula | II | Piti 2 | AF510967 | Literature (31) |

| Pitiprolamide | L. majuscula | II | Piti 2 | AF510967 | Literature (31) |

| Propenediester | cf. Oscillatoria sp. | II | PAC-17-FEB-10-3 | KC222262 | RNAlater (36) |

| Serinolamide A | cf. Oscillatoria sp. | II | PAC-17-FEB-10-3 | KC222262 | RNAlater (36) |

| Tumonoic acids A to C | L. majuscula | II | NAB11-47 | KC196267 | Recollection |

| Tumonoic acids D to I | Blennothrix cantharidosmum | II | PNG05-4 | EU253968 | Literature (35) |

| Venturamides A to B | Oscillatoria sp. | II | PAP-01-APR-05-8 | EU253967 | Culture (37) |

| Veraguamides A to C and H to L | cf. O. margaritifera | II | PAC17-FEB-10-2 | HQ900689 | Literature (38) |

| Viridamides A and B | Oscillatoria nigroviridis | II | 3LOSC | EU244875 | Literature (39) |

| Coibamide A | Leptolyngbya sp. | III | PAC-10-03 | KC207936 | Culture (40) |

| Dolastatin 10 | Symploca hydnoides | III | FK12-18 | KC207935 | Recollection |

| Hoiamides A and C | Phormidium gracile | III | PNG06-65 | HM072001 | Literature (41) |

| Janthielamide A | cf. Symploca sp. | III | NAC08-56 | JQ388601 | Literature (42) |

| Kimbeamides A to C | cf. Symploca sp. | III | PNG-07-14-07-6.1 | JQ388599 | Literature (42) |

| Kimbelactone A | cf. Symploca sp. | III | PNG-07-14-07-6.1 | Q388599 | Literature (42) |

| Largazole | Symploca sp. | III | FK12-18 | KC207935 | Recollection |

| Symplostatin 1 | S. hydnoides | III | VP377 | AF306497 | Literature (31) |

| Credneramides A and B | cf. Trichodesmium sp. | IV | PNG-05-19-05-13 | KC222263 | Literature (43) |

| Credneric acid | cf. Trichodesmium sp. | IV | PNG-05-19-05-13 | KC222263 | Literature (43) |

| Lyngbyoic acid | L. majuscula | IV | IRL1 | KC222261 | Recollection |

| Malyngolide | L. majuscula | IV | FFP12-4 | KC207937 | Recollection |

| Palmyrrolinone | cf. Oscillatoria sp. | IV | PAL-8-1-09-2.1 | JF262061 | Literature (44) |

| Thiopalmyrone | cf. Oscillatoria sp. | IV | PAL-8-1-09-2.1 | JF262061 | Literature (44) |

| Crossbyanols A to D | Leptolyngbya crossbyana | V | HI09-1 | GU111930 | Literature (45) |

| Honaucins A to C | Lept. crossbyana | V | HI09-1 | GU111930 | RNAlater (46) |

| Indanone | L. majuscula | VI | GTR 6 III 95-1 | AF510978 | Literature (31) |

| Palmyrolide A | Leptolyngbya sp. | VII | PAL08-3 | HM585025 | Literature (47) |

| Phormidolide | Phormidium sp. | VIII | ISB-3N94-8PLP | KC207938 | Culture (48) |

| Synechobactins A to C | Synechococcus sp. | IX | PCC 7002 | AJ000716 | Literature (49) |

| Trichamide | Trichodesmium erythraeum | X | IMS101R | NC008312 | Literature (50) |

Source of the NP-producing strain; recollection, environmental samples analyzed for NPs in this study (see Table S1 in the supplemental material for collection data); culture, known NP producers available in culture; RNAlater, known NP producers preserved for genetic analysis; literature, phylogenetically analyzed NP-producing strains available in the literature. The references refer to the source for the particular strain producing a specific NP.

cf., a species or genus whose identification is associated with taxonomic uncertainty.

RESULTS

Natural product diversity.

A total of 126 structurally diverse NPs, isolated from 43 different strains of cyanobacteria, were included in this study (Table 1). This data set of NP-producing cyanobacterial strains included (i) recollected specimens (number of NPs [nNPs] = 26; number of strains [nstrains] = 10), (ii) strains available in culture (nNPs = 17; nstrains = 6), and (iii) genetically preserved specimens (nNPs = 6: nstrains = 3). In addition, these samples were complemented by gene sequence data for published NP-producing strains available in GenBank (nNPs = 77; nstrains = 27) to further broaden the interpretation of the data. This data set comprises 23.6% of all marine cyanobacterium-derived NPs reported in 2011 (Marine Literature Database).

Uneven taxonomic distribution of natural products.

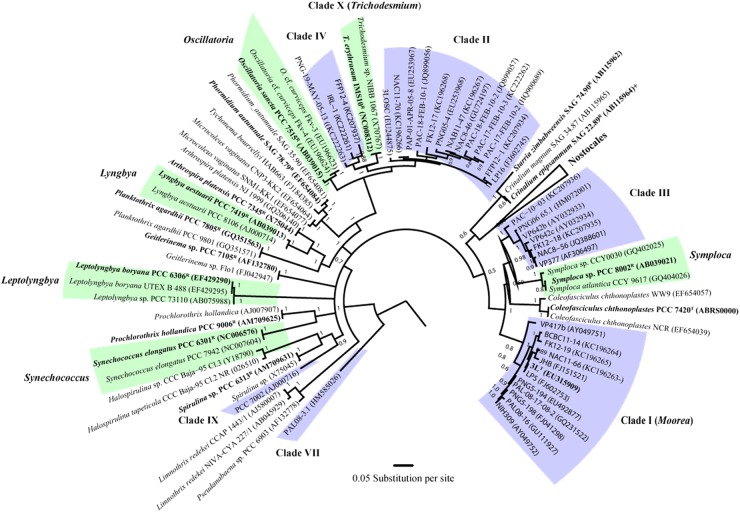

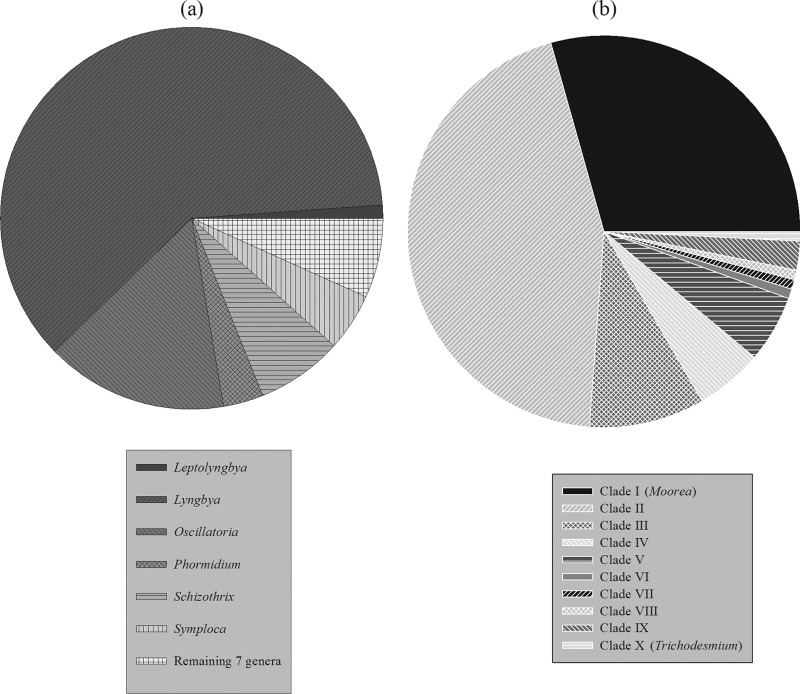

Phylogenetic inferences of the 44 NP-producing strains in this study revealed that all of these specimens belonged to only 10 major phylogenetic clades (clades I to X) (Fig. 1). Note that shorter gene sequences (<1,250 bp) were removed in the phylogenetic analysis, which included the strains from clades V, VI, and VIII. All gene sequences are available in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. On the basis of the scale of this phylogenetic tree, each clade can be assumed to represent an individual cyanobacterial genus. Among these 10 clades, clade I (nstrains = 11; nNPs = 37) and clade II (nstrains = 15; nNPs = 56) were clearly overrepresented in their production of NPs and together contained over 70% of all of these NPs (Fig. 2). Two other major NP-producing groups were clade III (nstrains = 6; nNPs = 12) and clade IV (nstrains = 4; nNPs = 7). A total of 14 secondary metabolites were isolated from the remaining six clades (clades V to X).

Fig 1.

Evolutionary tree of marine cyanobacteria known to produce NPs. The main NP-producing groups (highlighted with blue boxes) are placed in perspective with other cyanobacterial groups, in particular, their corresponding reference strains or type strains (highlighted with green boxes). The phylogram is based on SSU (16S) rRNA gene sequences using the Bayesian method (MrBayes), and the support values are indicated as posterior probabilities at the nodes. Note that gene sequences of <1,250 bp are removed in this analysis. All gene sequences from Table 1, including those of clades V, VI, and VIII, are available in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. The specimens are indicated as species and strain (GenBank accession number). The scale bar indicates 0.05 expected nucleotide substitutions per site.

Fig 2.

Taxonomic distribution of NPs in marine cyanobacteria on the basis of the published taxonomy of all (n = 533) marine cyanobacteria available in the 2011 Marine Literature Database (a) and NP-producing strains phylogenetically inferred in this study (n = 126) (b).

Novel biodiversity of NP-producing cyanobacteria.

Among the 10 phylogenetic clades of NP-producing strains, only clade I and clade X were monophyletic and evolutionarily closely related (p distance = <1%) to an established reference or type strain (Fig. 1). The specimens of clade I were related to the type strain Moorea producens 3L from the recently described genus Moorea, and trichamide (i.e., clade X) was isolated from Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS 101R. The remaining eight clades were either phylogenetically unrelated to any reference or type strains or poly- or paraphyletic in relation to them. The degree of evolutionary divergence varied between the different phylogenetic clades. For example, clades VI to VIII were all evolutionarily distant (p distance = >7%) from any known groups, while clade III and clade V were just on the threshold of generic novelty with 4.8% and 5.1% SSU rRNA gene sequence divergence, respectively. On the other hand, the NP-rich clade II and clade IV both had less than the recommended generic level of gene sequence divergence, with p distances of only 2.8% and 3.5% with the reference strains Oscillatoria sancta PCC 7515R and Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS 101R, respectively. However, their geographical and ecological divergences from their reference strains suggest that these clades should indeed represent separate generic entities.

Notably, none of the NP-producing strains analyzed in this study were closely related to the type or reference strain of any of the major traditional NP-producing groups, such as Lyngbya, Oscillatoria, Leptolyngbya, or Symploca (Fig. 1). Furthermore, only one NP-producing strain, the trichamide-producing strain IMS 101R, was both monophyletic and evolutionarily related to the type or reference strain of the taxon to which it had been designated (clade X). Another six strains were monophyletic but evolutionarily distant from their reference strains. Among the remaining NP-producing strains, 29 were polyphyletic and 8 were paraphyletic in relation to the reference strains of the taxa to which they had been attributed.

DISCUSSION

During the last 3 decades, tropical marine cyanobacteria have been a prolific source of natural products. Creative endeavors have been used to explore their novel chemical diversity, but lagging are the recognition and description of the biological diversity responsible for these NPs. Instead of being recognized as unique taxa, NP-producing groups have been identified, with few exceptions, on the basis of classification systems tied to morphospecies of terrestrial and freshwater specimens from temperate regions. This is primarily due to a lack of proper classification systems since tropical marine cyanobacteria have only recently been investigated taxonomically using phylogenetic methods. As a result, our current perspective of the taxonomic origin and distribution of NPs in marine cyanobacteria is here shown to be incomplete. For example, over 90% of all marine-derived NPs have been attributed to the three cyanobacterial genera Lyngbya, Oscillatoria, and Symploca (Marine Literature Database). However, none of the NP-producing cyanobacterial strains attributed to these three groups were, in this study, related to their respective reference strains. The common perception of these genera as NP-rich groups can therefore be assumed to be incorrect, and the NPs ascribed to these genera are most likely produced by other, often undescribed groups with morphological similarities.

This study reveals a large extent of novel and unrecognized cyanobacterial biodiversity from tropical and subtropical marine environments. Our indicator of biodiversity was the genetic diversification of the gene encoding the small ribosomal subunit or the 16S rRNA gene. The 16S rRNA gene has been widely accepted to be a robust evolutionary metric and consequently a reliable indicator of biodiversity in cyanobacteria (11). However, the conserved nature of the 16S rRNA gene sometimes renders it insufficient to distinguish between different species of cyanobacteria (51). This may cause an even further underestimation of natural diversity, potentially reflected here in the extensive amount of chemical, geographical, and ecological diversity found in phylogenetically closely related clades.

Although our data reveal a large extent of novel biodiversity, this is not reflected in a more dispersed taxonomic distribution of NPs. Certain taxa, such as the ones of clade I (Moorea) and of clade II and to a certain degree those of clade III and of clade IV, were together responsible for the vast majority of marine cyanobacterial NPs. There are several plausible explanations for this uneven taxonomic distribution of NPs in marine cyanobacteria. Many of these NP-rich groups are geographically widespread and often form extensive cyanobacterial blooms that are dominant in tropical marine environments. The same groups are also among the morphologically largest cyanobacteria described to date. For example, specimens of the NP-rich species Moorea producens measure up to 80 μm in diameter (15). The availability of sufficient biomass for chemical extractions and isolation could have been a driving force in these taxa being more heavily screened for NPs.

Many of these specimens produce sets of structurally diverse secondary metabolites, while some NP-rich taxa have also been shown by genomics to contain multiple biosynthetic pathways encoding bioactive secondary metabolites (52), suggesting that NP richness is an evolutionary adaptation in these taxa. However, there are not yet sufficient genomic data to verify this hypothesis. More genomic investigations are clearly necessary to resolve if these NP-rich specimens, in fact, have evolved to be biosynthetically more prolific in bioactive secondary metabolite production. However, such genomic investigations arguably rely on informative taxonomic systems that truly reflect biodiversity. This study is intended to provide an evolutionary framework for such a system. Moreover, the phylogenetic inferences of these NP-producing cyanobacteria uncover true biodiversity, which is essential for monitoring and predicting environmentally important CyanoHABs as well as sustaining efficient and productive bioactive secondary metabolite discovery efforts for pharmaceutical applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was generously supported by a Smithsonian Marine Science Network postdoctoral fellowship (to N.E.). W.H.G. thanks NIH (grants CA100851 and NS053398) for support. The fieldwork was supported by the Carmabi Research Station (Curaçao), the Carrie Bow Cay Field Station (Belize), the Smithsonian Marine Station (Ft. Pierce, FL), the Mote Marine Laboratory (Summerland Key, FL), and the Council on International Educational Exchange Research Station (Bonaire).

HR-ESI-MS was performed by the Mass Spectrometry facilities of the University of California, Riverside.

We gratefully acknowledge Amy Wright and Priscilla Winder at Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute at Florida Atlantic University for usage of LC MS and NMR. We also thank Jeff Hunt and Lee Weigt at the Laboratories of Analytical Biology of the National Museum of Natural History for gene sequencing and general lab support. We thank Roger Linington, Marcy Balunas, Kerry McPhail, Christopher Thornburg, Raphael Ritson-Williams, and Sherry Reed for help with collecting, as well as Julie Piraino and Hugh Reichardt for general lab assistance. We thank Hendrik Luesch for providing several pure cyanobacterial natural products for LC MS standards. We also thank Robert Thacker for phylogenetics advice and comments. We also acknowledge the governments of Curaçao, Belize, and Bonaire for permits for this research project.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 January 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.03793-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gerwick WH, Coates RC, Engene N, Gerwick LG, Grindberg R, Jones A, Sorrels C. 2008. Giant marine cyanobacteria produce exciting potential pharmaceuticals. Microbe 3:277–284 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nunnery JK, Mevers E, Gerwick WH. 2010. Biologically active secondary metabolites from marine cyanobacteria. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 21:1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tidgewell K, Clark BR, Gerwick WH. 2010. The natural products chemistry of cyanobacteria, p 141–188 In Mander L, Lui H-W. (ed), Comprehensive natural products II chemistry and biology, vol 2 Elsevier, Oxford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tan LT. 2010. Filamentous tropical marine cyanobacteria: a rich source of natural products for anticancer drug discovery. J. Appl. Phycol. 5:659–676 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osborne NJT, Webb PM, Shaw GR. 2001. The toxins of Lyngbya majuscula and their human and ecological health effects. Environ. Int. 27:381–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paul VJ, Arthur KE, Ritson-Williams R, Ross C, Sharp K. 2007. Chemical defenses: from compounds to communities. Biol. Bull. 213:226–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Neil JM, Davis TW, Burford MA, Gobler CJ. 2012. The rise of harmful cyanobacteria blooms: the potential roles of eutrophication and climate change. Harmful Algae 14:313–334 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paerl HW, Paul VJ. 2012. Climate change: links to global expansion of harmful cyanobacteria. Water Res. 46:1349–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Villa FA, Gerwick L. 2010. Marine natural product drug discovery: leads for treatment of inflammation, cancer, infections, and neurological disorders. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 32:228–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berry JP, Gantar M, Perez MH, Berry G, Noriega FG. 2008. Cyanobacterial toxins as allelochemicals with potential applications as algaecides, herbicides and insecticides. Mar. Drugs 6:117–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilmotte A, Herdman M. 2001. Phylogenetic relationships among the cyanobacteria based on 16S rRNA sequences, p 487–493 In Boone DR, Castenholz RW, Garrity GM. (ed), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed, vol 1 Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sharp K, Arthur KE, Gu L, Ross C, Harrison G, Gunasekera SP, Meickle T, Matthew S, Luesch H, Thacker RW, Sherman DH, Paul VJ. 2009. Phylogenetic and chemical diversity of three chemotypes of bloom-forming Lyngbya species (Cyanobacteria: Oscillatoriales) from reefs of southeastern Florida. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:2879–2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Engene N, Coates RC, Gerwick WH. 2010. 16S rRNA gene heterogeneity in the filamentous marine cyanobacterial genus Lyngbya. J. Phycol. 46:591–601 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Engene N, Choi H, Esquenazi E, Rottacker EC, Ellisman MH, Dorrestein PC, Gerwick WH. 2011. Underestimated biodiversity as a major explanation for the perceived prolific secondary metabolite capacity of the cyanobacterial genus Lyngbya. Environ. Microbiol. 13:1601–1610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Engene N, Rottacker EC, Choi H, Byrum T, Kaštovský JH, Komárek J, Gerwick WH. 2012. Moorea producens gen. nov., sp. nov. and Moorea bouillonii comb. nov., tropical marine cyanobacteria rich in bioactive secondary metabolites. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 62:1172–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Castenholz RW. 2001. Phylum BX. Cyanobacteria oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria, p 473–553 In Boone DR, Castenholz RW, Garrity GM. (ed), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd ed, vol 1 Springer, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 17. Komárek J, Anagnostidis K. 2005. Süsswasserflora von Mitteleuropa, 19/2 ed Elsevier/Spektrum, Heidelberg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nübel U, Garcia-Pichel F, Muyzer G. 1997. PCR primers to amplify 16S rRNA genes from cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3327–3332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ashelford KE, Chuzhanova NA, Fry JC, Jones AJ, Weightman A. 2005. New screening software shows that most recent large 16S rRNA gene clone libraries contain chimeras. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7724–7736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Posada D. 2008. jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25:1253–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stamatakis A, Ludwig T, Meier H. 2005. RAxML-III: a fast program for maximum likelihood-based inference of large phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 21:456–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 12:1572–1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grindberg RV, Ishoey T, Brinza D, Esquenazi E, Coates RC, Liu W-T, Gerwick L, Dorrestein PC, Pevzner P, Lasken R, Gerwick WH. 2011. Single cell genome amplification accelerates identification of the apratoxin biosynthetic pathway from a complex microbial assemblage. PLoS One 6:e18565 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gutierrez M, Suyama T, Engene N, Wingerd J, Matainaho T, Gerwick WH. 2008. Apratoxin D, a potent cytotoxic cyclodepsipeptide from Papua New Guinea collections of the marine cyanobacteria Lyngbya majuscula and Lyngbya sordida. J. Nat. Prod. 71:1099–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tidgewell K, Engene N, Byrum T, Media J, Doi T, Valeriote FA, Gerwick WH. 2010. Evolved diversification of a modular natural product pathway: apratoxins F and G, two cytotoxic cyclic depsipeptides from a Palmyra collection of Lyngbya bouillonii. Chembiochem 11:1458–1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pereira AR, McCue C, Gerwick WH. 2010. Cyanolide A, a glycosidic macrolide with potent molluscicidal activity from the Papua New Guinea cyanobacterium Lyngbya bouillonii. J. Nat. Prod. 73:217–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marquez BL, Watts KS, Yokochi A, Roberts MA, Verdier-Pinard P, Jimenez JI, Hamel E, Scheuer PJ, Gerwick WH. 2002. Structure and absolute stereochemistry of hectochlorin, a potent stimulator of actin assembly. J. Nat. Prod. 65:866–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Edwards DJ, Marquez BL, Nogle LM, McPhail K, Goeger DE, Roberts MA, Gerwick WH. 2004. Structure and biosynthesis of the jamaicamides, new mixed polyketide-peptide neurotoxins from the marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. Chem. Biol. 11:817–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thacker RW, Paul VJ. 2004. Morphological, chemical, and genetic diversity of tropical marine cyanobacteria Lyngbya spp. and Symploca spp. (Oscillatoriales). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3305–3312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Taniguchi M, Nunnery J, Engene N, Esquenazi E, Byrum T, Dorrestein PC, Gerwick WH. 2010. Palmyramide A, a cyclic depsipeptide from a Palmyra atoll collection of the marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. J. Nat. Prod. 73:393–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Balunas MJ, Grosso MF, Villa FV, Engene N, McPhail KL, Tidgewell K, Pineda LM, Gerwick L, Spadafora C, Kyle DE, Gerwick WH. 2012. Coibacins A-D, new anti-leishmanial polyketides with intriguing biosynthetic origins. Org. Lett. 14:3878–3881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Engene N, Choi H, Esquenazi E, Byrum T, Villa F, Murray T, Dorrestein PC, Gerwick LG, Gerwick WH. 2011. Phylogeny-guided isolation of ethyl tumonoate A from the marine cyanobacterium cf. Oscillatoria margaritifera. J. Nat. Prod. 74:1737–1743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Clark BR, Engene N, Teasdale ME, Rowley DC, Matainaho T, Valeriote FA, Gerwick WH. 2008. Natural products chemistry and taxonomy of the marine cyanobacterium Blennothrix cantharidosmum. J. Nat. Prod. 71:1530–1537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gutierrez M, Pereira AR, Debonsi HM, Ligresti A, Di Marzo V, Gerwick WH. 2011. Cannabinomimetic lipid from a marine cyanobacterium. J. Nat. Prod. 74:2313–2317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Linington RG, González J, Ureña L-D, Romero LI, Ortego-Barria E, Gerwick WH. 2007. Venturamides A and B: antimalarial constituents of the Panamanian marine cyanobacterium Oscillatoria sp. J. Nat. Prod. 70:397–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mevers E, Liu W-T, Engene N, Byrum T, Dorrestein PC, Gerwick WH. 2011. Cytotoxic veraguamides, alkynyl bromide containing cyclic depsipeptides from an unusual marine cyanobacterium cf. Oscillatoria margaritifera. J. Nat. Prod. 74:928–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Simmons TL, Engene N, Urena L, Romero LI, Ortega-Barria E, Gerwick L, Gerwick WH. 2008. Viridamides A and B, lipodepsipeptides with antiprotozoal activity from the marine cyanobacterium Oscillatoria nigro-viridis. J. Nat. Prod. 71:1544–1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Medina RA, Goeger DE, Hills P, Mooberry SL, Huang N, Romero LI, Ortega-Barria E, Gerwick WH, McPhail KL. 2008. Coibamide A, a potent antiproliferative cyclic depsipeptide from the Panamanian marine cyanobacterium Leptolyngbya sp. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130:6324–6325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Choi H, Pereira AR, Cao Z, Shuman CF, Engene N, Byrum T, Matainaho T, Murray TF, Mangoni A, Gerwick WH. 2010. The hoiamides, structurally-intriguing neurotoxic lipopeptides from Papua New Guinea marine cyanobacteria. J. Nat. Prod. 73:1411–1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nunnery JK, Engene N, Byrum T, Cao Z, Sairam J, Pereira A, Teatulohi M, Murray TF, Gerwick WH. 2012. Biosynthetically-intriguing chlorinated lipophilic metabolites from geographically distant tropical marine cyanobacteria. J. Nat. Prod. 77:4198–4208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Malloy KL, Suyama TL, Engene N, Debonsi H, Cao Z, Matainaho T, Murray TF, Gerwick WH. 2012. Credneramides A and B: neuromodulatory phenethylamine and isopentylamine derivatives of a vinyl chloride-containing fatty acid from a Papua New Guinea collection of Lyngbya sp. J. Nat. Prod. 75:60–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pereira AR, Etzbach L, Engene N, Müller R, Gerwick WH. 2011. Unusual molluscicidal chemotypes from a new Palmyra Atoll cyanobacterium. J. Nat. Prod. 74:1175–1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Choi H, Engene N, Smith JE, Preskitt LB, Gerwick WH. 2010. Crossbyanols A-D, toxic brominated polyphenyl ethers from the Hawai'ian bloom-forming cyanobacterium Leptolyngbya crossbyana. J. Nat. Prod. 73:517–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Choi H, Mascuch SJ, Villa FA, Byrum T, Teasdale ME, Smith JE, Preskitt LB, Rowley DC, Gerwick L, Gerwick WH. 2012. Honaucins A-C, potent inhibitors of inflammation and bacterial quorum sensing: synthetic derivatives and structure-activity relationships. Chem. Biol. 19:589–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pereira AR, Cao Z, Engene N, Soria-Mercado IE, Murray TF, Gerwick WH. 2010. Palmyrolide A, an unusually stabilized neuroactive macrolide from Palmyra atoll cyanobacteria. Org. Lett. 12:4490–4493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Williamson RT, Boulanger A, Vulpanovici A, Roberts MA, Gerwick WH. 2002. Structure and absolute stereochemistry of phormidolide, a new toxic metabolite from the marine cyanobacterium Phormidium sp. J. Org. Chem. 7:7927–7936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yusai I, Butler A. 2005. Structure of synechobactins, new siderophores of the marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50:1918–1923 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sudek S, Haygood MG, Youssef DTA, Schmidt EW. 2006. Structure of trichamide, a cyclic peptide from the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Trichodesmium erythraeum, predicted from the genome sequence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4382–4387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Perkerson RB, III, Johansen JR, Kovácik L, Brand J, Kaštovský J, Casamatta DA. 2011. A unique Pseudanabaenalean (Cyanobacteria) genus Nodosilinea gen. nov. based on morphological and molecular data. J. Phycol. 47:1397–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jones AC, Monroe EA, Podell S, Hess W, Klages S, Esquenazi E, Niessen S, Hoover H, Rothmann M, Lasken R, Yates JR, III, Reinhardt R, Kube M, Burkart M, Allen EE, Dorrestein PC, Gerwick WH, Gerwick L. 2011. Genomic insights into the physiology and ecology of the marine filamentous cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:8815–8820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]