Abstract

AIM

To define the prevalence and associations of behaviour disorder in children with epilepsy from a rural district of Tanzania by conducting a community-based case-control study.

METHOD

Children aged 6-14 years old with active epilepsy (at least two unprovoked seizures in the last five years) were identified in a cross-sectional survey in Tanzania. Behaviour was assessed using the Rutter scale. Cases were compared with age-matched controls.

RESULTS

Behaviour disorder was diagnosed in 68/103 (66%) of children with epilepsy and 19/99 (19%) of controls. Disordered behaviour was significantly more common in cases than controls (univariate OR 8.2, 95% CI 4.3 – 15.6, p<0.001) and in cases, was associated with frequent seizures and poor scholastic attainment in controls. Attention problems were present in 48/91 (53%) children with epilepsy and 16/97 (17%) controls (univariate OR 5.7. 95% CI 2.9 – 11.1, p<0.001). In cases, attention problems were significantly more common in males and associated with frequent seizures.

INTERPRETATION

Children with epilepsy in a rural area of sub-Saharan Africa have a high prevalence of behavioural disorders and attention problems. Frequent seizures were associated with both. Providing behaviour assessment and appropriate intervention programmes for children with epilepsy may reduce the burden of behaviour disorder in this setting.

Keywords: epilepsy, Africa, children, behaviour, attention

Epilepsy is the most common neurological disorder worldwide; 80% of affected children are estimated to live in low-income countries.1 The prevalence of behavioural disorders in children in urban settings from high-income countries is greater in those with epilepsy compared to those without epilepsy2;3 and to those with other chronic conditions such as diabetes and asthma.2;4;5 In children with epilepsy the prevalence of behavioural disorder ranges from 20% to 60%.6-12 Behavioural problems are associated with early onset of seizures and with certain seizure types,13 increased seizure frequency,7;13 polytherapy14, cognitive impairment,3 family factors, parenting practices and infant temperament.15-17

There is limited data on the prevalence and nature of behavioural problems in children with epilepsy in low-income countries. Two studies from India found similar rates of behaviour (54%) and psychiatric disorder (23%) to those reported from high-income countries.18;19 There are only a few studies on behaviour disorders in children with epilepsy from Africa. A study of 102 Nigerian adolescents attending neuropsychiatry outpatient clinic with epilepsy found 31% had anxiety and 28% had depression.20 Another Nigerian survey found 37% of 204 adults and adolescents attending a neurology outpatients clinic had a psychiatric diagnosis.21 There have been no published community-based studies of behaviour disorder before in Africa. We hypothesised that the prevalence of behaviour disorder would be higher in children with epilepsy than community controls and that risk factors would be similar to other community-based studies on epilepsy. Therefore we examined the prevalence, pattern and risk factors for behavioural problems in children with active epilepsy during a community-based survey in a rural part of Africa.

METHODS

Study area and population

We conducted a cross-sectional study of epilepsy in Hai district, Northern Tanzania. Hai District was established in 1992 as a Demographic Surveillance Site by the Adult Morbidity and Mortality Project (AMMP).22 There is an established network of local enumerators experienced in conducting epidemiological surveys. We identified all 6 to 14 year old children with epilepsy in Hai after a census in January 2009. We used controls selected from the community in Hai District for comparison.

Definitions

We used the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) definitions and defined active epilepsy as two or more afebrile seizures, 24 hours apart, unrelated to acute infection, metabolic disturbance, neurological disorders or drugs, in the last five years.23 Children taking antiepileptic drugs were also considered as having active epilepsy and all of these met ILAE criteria for being a case of active epilepsy. Epileptic seizures were classified according to the ILAE guidelines.24

Case ascertainment and criteria for inclusion and exclusion

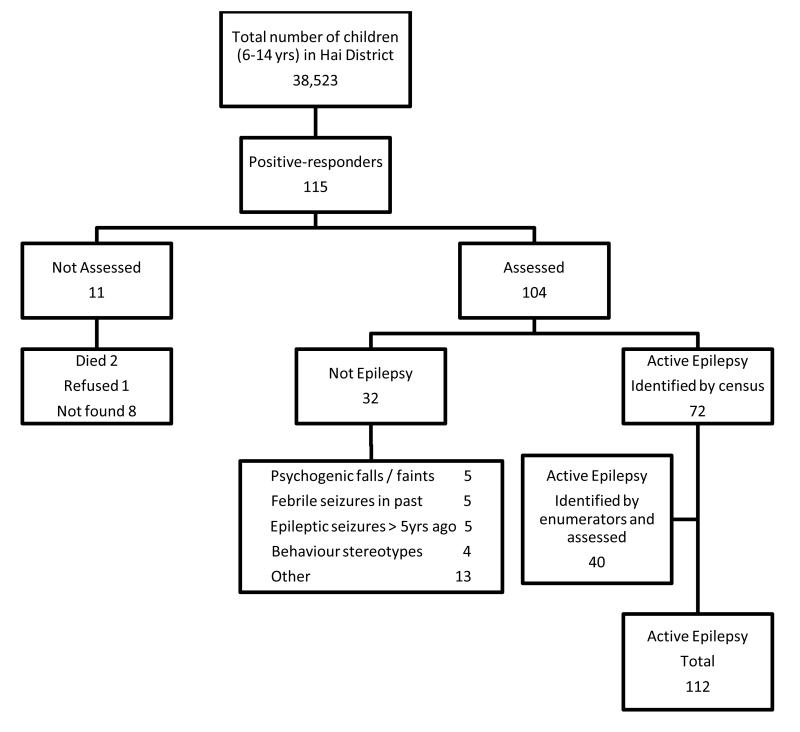

During the census a nine-item, previously validated questionnaire was administered to all households in Hai district.25 This instrument was translated into Swahili and back translated. The details of any 6 to 14 year old children who responded positively to one or more questions in the screening questionnaire, together with those identified by trained enumerators as likely to have epilepsy, were identified (see Figure 1). The study paediatrician (KB), who has training in paediatric epilepsy, assessed each child. The diagnosis of active epilepsy and seizure type were verified by a paediatric neurologist (CN) and by a second independent paediatric neurologist (BN) for cases that were considered indeterminate. EEG and CT scans were not used in the diagnosis of active epilepsy.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of case ascertainment and recruitment

Cases of epilepsy were defined as children with active epilepsy aged 6 to 14 yrs who were resident in Hai at the time of the census. Those children for whom consent was refused, or who were below 6 years old (to eliminate any children with febrile seizures), were excluded.

Controls were drawn from a matched sample from all the children from the census. Controls were identified by matching to the positive responders for age (+/− 1 year), sex and village. Those with missing identification data were excluded. From this list of eligible children, 186 were randomly selected. Controls were included if they were resident in Hai at the time of the census survey, were aged 6 to 14 yrs and the parents had given consent.

Neuropaediatric assessment

A full clinical history was taken using a standardised questionnaire and a neuropaediatric examination was completed for each case and control.

Follow-up

From February to June 2010, all probable epilepsy cases and all controls were recalled for behavioural and cognitive assessment. For cases, clinical history and response to treatment were reviewed.

Behavioural assessment

The Rutter questionnaire for parents only was used for assessing behaviour as it has good inter-rater reliability and discriminative power for detecting behaviour disorder.26 It was designed as a screening instrument for behavioural disorders in children aged 7 to 13 yrs. It has a inter-rater reliability measured at 0.64.27 In comparison to the widely used Child Behaviour Checklist(CBCL), the correlation between total scores on the two tests was shown to be 0.79.28 There is a standardised scoring system and a neurotic and antisocial subscore are made by summing different items from within the test. Children with total scores of 13 or more are designated as showing behaviour disorder. Attention problems were scored using three specific items(restlessness, fidgeting and poor concentration). Scores of 0 and 1 overall were categorised as no attention problem, 2 and above as having attention problems. The questions were independently translated and back translated by two local Tanzanian staff. This ensured that linguistic and culturally appropriate terms and phrases were used. The questionnaire and test were explained and a standardised administration method used by all the assessors. One trained individual (JR) administered the questionnaire to all the cases and four trained senior district health workers administered the questionnaire to the controls. The assessors were aware of the epilepsy status but not of their epilepsy variables. Inter-rater reliability was not assessed specifically for this study for case-to-control comparison but the Rutter parent questionnaire is known to have good inter-rater reliability.27 The results were all scored by one person (KB).

Cognitive assessment

An assessment of cognitive function was made using the Goodenough-Harris Drawing Test.29 Standard instructions for drawing figures were translated into Kiswahili and back translated to ensure accuracy and instructions were read out at assessment. Assessors were aware of case status but not of the Rutter score. Each drawing was marked by one person (KB). Raw scores for the drawings of each child were age-standardised, averaged and the resulting score was used for comparison. Those scoring less than 70 (>2 standard deviations below the mean) were categorised as having cognitive impairment.

Ethical approval

Approval for this study was obtained from the National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania and the local Ethics Committee of KCMC, Moshi was supportive of the study. Parents and guardians of cases and controls were given written and verbal information in Kiswahili before giving consent to participate.

Data Analysis

All data were double entered into a Microsoft Access database. The two database copies were compared using Epidata (Version 3.1) and each discrepancy was checked against original data forms. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA v.10 (Statacorp, College Station, TX, USA).

The median Rutter score was compared (using Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-parametric data) for cases and controls as the distribution of scores was skewed. The proportion in cases and controls of different ages, sex and parent education were similar in cases and controls and were not included in the comparison. Further analysis was performed using a binary variable of disordered against normal behaviour score. Seizure variables included in analyses for cases were chosen if they had been shown to be associated with behaviour problems in other studies (age at onset, seizure type, seizure frequency and polytherapy). In the controls, sociodemographic variables and education-related variables related were chosen as these are associated with behaviour. Univariable odds ratios were calculated for associations between variables and the presence of behavioural disorder (Rutter A2 score >13) and attention problems in cases and controls separately. These are presented with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Cases were labelled as having frequent seizures if they had any ongoing seizures in the 3 months before assessment. Early-onset epilepsy was defined as onset at or before age three years. Scholastic attainment was considered poor if the child was not in an age appropriate class or had repeated a year. Education of the head of household was used as a surrogate marker for socio-economic status as previous research from Hai district had shown this was a key determinant in explaining between-household variation in expenditure.30 Ethnic groups were classified as Chagga (the predominant group) against the other groups. Multivariable logistic regression models were developed for cases and controls separately including factors with p-values less or equal to 0.1 in the univariate analysis.

RESULTS

Study subjects

Overall a total of 112 children with active epilepsy and 113 controls were identified (Figure 1). From the census survey there were 115 positive responders of whom 104 were assessed. 72 were found to be cases from these and an additional 40 cases were identified by trained village enumerators. For one case only (girl, aged 10 years) carers refused consent. Of the 112 cases and 113 controls identified, some cases and controls did not attend follow up after initial assessment so 103 cases and 99 controls had behaviour assessed overall. Demographic characteristics of cases and controls are presented in Table 1; age, sex and head of the household education were comparable between cases and controls assessed for behaviour. The proportion of cases coming from the Chagga ethnic group was slightly lower than that for controls (OR2.2, 95%CI 1.0-4.7,p=0.041). Of cases and controls not assessed for behaviour, compared to those who were, there was no significant difference in the variables except more cases had early age of seizure onset. From the list of 186 matched controls, 73 children were either not found or their carer refused consent. There was no significant difference between the controls who were seen and the controls who were not in terms of age and sex (median age 11 years for both; and 52.2% and 46.6% were male respectively, OR 1.3, 95%CI 0.7-2.3,p=0.453).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of cases and controls assessed and not assessed for behaviour disorder.

| Variable | Cases (N=103) |

Controls (N=99) |

Cases not assessed (N=9) |

Controls not assessed (N=14) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | (n) | (%) | (n) | (%) | |

| Sex, male | 51 | (49%) | 50 | (50%) | 7 | (77.8) | 8 | (57.1%) |

| Mean age (years,95% CI) | 11.7 | (11.3,12.2) | 11.0 | (11.0,12.0) | 12.7 | (10.7,14.8) | 11.1 | (9.7,12.6) |

| Education - head of house | ||||||||

| None | 5 | (5%) | 3 | (3%) | 1 | (11.1) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Primary | 88 | (85%) | 84 | (85%) | 6 | (66.7) | 7 | (50.0) |

| Secondary | 10 | (10%) | 12 | (12%) | 1 | (11.1) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Not known | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (11.1) | 7 | (50.0) |

| Ethnic group | ||||||||

| Chagga | 79 | (77%) | 87 | (88%) | 7 | (77.8) | 14 | (100.0) |

| Other | 24 | (23%) | 12 | (12%) | 2 | (22.2) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Antiepileptic medication at assessment | ||||||||

| Phenobarbital | 42 | (40.8%) | ||||||

| Other AED | 4 | (3.9%) | ||||||

| Polytherapy | 8 | (7.8%) | ||||||

| Not known to be on AED |

49 | (47.5%) | ||||||

| Treatment regularity at assessment | ||||||||

| Daily | 39 | (37.8%) | ||||||

| Not daily | 15 | (14.6%) | ||||||

| Not on AED | 49 | (47.6%) | ||||||

| Not attending school regularly | 49 | (48%) | 0 | (0.0%) | ||||

| Behaviour problems that caused withdrawal from school |

6 | (6/49,12%) | 0 | (0.0%) | ||||

Prevalence of behavioural problems

Disordered behaviour was significantly more common in cases (68/103, 66%) than controls (19/99, 19%); univariate OR 8.2, 95%CI 4.3 – 15.6,p<0.001. The median Rutter score was significantly higher in cases (median 17, 95%CI 15-29) than the controls (median 6, 95%CI 5-8); Wilcoxon rank-sum test p<0.001 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution for Rutter score for controls (99) and cases (103).

Pattern of behavioural problems

The differential Rutter scores comparing antisocial to neurotic sub-scores were not significantly different between cases and controls (OR 0.95; 95%CI 0.4-2.6; p=0.92). Attention problems (not scored in all children due to missing data), were significantly more common in cases (48/91, 53%) than controls (16/97, 17%), (univariate OR 5.7. 95%CI 2.9 – 11.1, p<0.001).

Risk factors for behavioural problems

Disordered behaviour was more common in cases with frequent seizures and in boys; there were no significant univariate associations with age, ethnic group, education of the household head, cognitive impairment or with early onset of seizures (Table 2 and 3). In multivariable logistic regression, disordered behaviour in cases remained significantly associated with frequent seizures (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of children with and without (i) disordered behaviour (p value from Chi squared test comparing those with and without behaviour assessment) and (ii) attention problems.

| CASES | CONTROLS | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Disordered Behaviour (N=68) |

Normal Behaviour (N=35) |

Not tested (N=9) |

Disordered Behaviour (N=19) |

Normal Behaviour (N=80) |

Not tested (N=14) |

||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 37 | (54.4) | 13 | (37.2) | 7 | (77.8) | 11 | (57.9) | 38 | (47.5) | 8 | (57.1) |

| Female | 31 | (45.6) | 22 | (62.8) | 2 | (22.2) | 8 | (42.1) | 42 | (52.5) | 6 | (42.9) |

| p=0.092 | p=0.592 | |||||||||||

| Age at assessment (yrs) | ||||||||||||

| Less than 12 yrs | 37 | (54.4) | 20 | (57.1) | 2 | (22.2) | 10 | (52.6) | 45 | (56.3) | 8 | (57.1) |

| 12 yrs and over | 31 | (45.6) | 15 | (42.9) | 7 | (77.8) | 9 | (47.4) | 35 | (43.7) | 6 | (42.8) |

| p=0.268 | p=0.373 | |||||||||||

| Scholastic attainment | ||||||||||||

| Not poor | 21 | (30.9) | 18 | (51.4) | 2 | (22.2) | 11 | (57.9) | 69 | (86.2) | 12 | (85.7) |

| Poor | 47 | (69.1) | 17 | (48.6) | 7 | (77.8) | 8 | (42.1) | 11 | (13.8) | 2 | (14.3) |

| p=0.350 | p=0.659 | |||||||||||

| Cognitive impairment | ||||||||||||

| Impaired | 50 | (73.5) | 22 | (62.9) | 3 | (15.8) | 3 | (3.8) | ||||

| None | 18 | (26.5) | 12 | (34.3) | 16 | (84.2) | 76 | (95.0) | ||||

| Not known | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (2.8) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.2) | ||||

| Early onset of seizures | ||||||||||||

| 3 yrs or less | 33 | (48.5) | 19 | (54.3) | 1 | (11.1) | ||||||

| Older than 3 yrs | 33 | (48.5) | 15 | (42.9) | 7 | (77.8) | ||||||

| Not known | 2 | (3.0) | 1 | (2.8) | 1 | (11.1) | ||||||

| p=0.032 | ||||||||||||

| Frequent seizures | ||||||||||||

| Frequent | 40 | (58.8) | 11 | (31.4) | ||||||||

| Not Frequent | 28 | (41.2) | 24 | (68.6) | ||||||||

| Not known | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (2.8) | ||||||||

| Seizure type | ||||||||||||

| Focal | 50 | (73.5) | 30 | (8.6) | 7 | (77.8) | ||||||

| Generalised | 16 | (23.5) | 4 | (11.4) | 2 | (22.2) | ||||||

| Not known | 2 | (3.0) | 1 | (2.8) | p=0.874 | |||||||

| Antiepileptic medication at assessment | ||||||||||||

| On Phenobarbital | 27 | (39.7) | 15 | (42.9) | 5 | (55.6) | ||||||

| On other AED | 3 | (4.4) | 1 | (2.8) | 0 | (0.0) | ||||||

| On polytherapy | 4 | (5.9) | 4 | (11.4) | 1 | (11.1) | ||||||

| Not known to be on AED |

34 | (50.0) | 15 | (42.9) | 3 | (33.3) | ||||||

| No attention problems (N=43) |

Attention problems (N=48) |

No attention problems (N=81) |

Attention problems (N=16) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 13 | (30.2) | 31 | (64.6) | 36 | (44.4) | 11 | (68.7) |

| Female | 30 | (69.8) | 17 | (35.4) | 45 | (55.6) | 5 | (31.3) |

| Age at assessment | ||||||||

| Less than 12 yrs | 21 | (48.8) | 28 | (58.3) | 43 | (53.1) | 10 | (62.5) |

| 12 yrs and over | 22 | (51.2) | 20 | (41.7) | 38 | (46.9) | 6 | (37.5) |

| Cognitive impairment | ||||||||

| Impaired | 25 | (58.1) | 37 | (77.1) | 2 | (2.5) | 4 | (25.0) |

| None | 17 | (39.6) | 11 | (22.9) | 78 | (96.3) | 12 | (75.0) |

| Not knwon | 1 | (2.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (1.2) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Early onset of seizures | ||||||||

| 3 yrs or less | 17 | (39.5) | 27 | (56.2) | ||||

| More than 3 yrs | 24 | (55.8) | 20 | (41.7) | ||||

| Not known | 2 | (4.7) | 1 | (2.1) | ||||

| Frequent seizures | ||||||||

| Frequent | 14 | (32.6) | 29 | (67.4) | ||||

| Not frequent | 29 | (67.4) | 19 | (39.6) | ||||

| Seizure type (focal) | ||||||||

| Focal | 34 | (79.1) | 37 | (77.1) | ||||

| Generalized | 8 | (18.6) | 10 | (20.8) | ||||

| Not known | 1 | (2.3) | 1 | (2.1) | ||||

Table 3.

Associations with (i) disordered behaviour and (ii) attention problems in cases.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

(i) Associations with disordered behaviour in cases | |||

| Univariate associations: | |||

| Sex (male) | 2.0 | 0.9 – 4.7 | 0.099 |

| Ethnic group (not Chagga) | 0.8 | 0.3 – 2.1 | 0.678 |

| Cognitive impairment (present) | 1.5 | 0.6 – 3.7 | 0.358 |

| Age at assessment (yrs) | 1.1 | 0.4 – 2.5 | 0.792 |

| Education of head of house | 0.9 | 0.3 – 2.7 | 0.876 |

| Poor scholastic attainment | 2.4 | 1.0 – 5.5 | 0.044 |

| Early onset of seizures | 0.8 | 0.3 - 1.8 | 0.577 |

| Frequent seizures at follow up | 3.1 | 1.3 – 7.4 | 0.010 |

| Seizure type (focal) | 2.4 | 0.7 – 7.8 | 0.148 |

| Treatment at assessment: | |||

| None | 1.0 | - | - |

| Other AED | 1.3 | 0.1 – 13.8 | 0.815 |

| Phenobarbital | 0.8 | 0.3 – 1.9 | 0.606 |

| Polytherapy | 0.4 | 0.1 – 2.0 | 0.289 |

| Multivariable logistic regression model: | |||

| Sex (male) | 2.1 | 0.9 – 5.2 | 0.107 |

| Poor scholastic attainment | 1.8 | 0.7 – 4.4 | 0.199 |

| Frequent seizures at follow up | 3.2 | 1.3 – 7.8 | 0.012 |

| (ii) Associations with attention problems in cases | |||

| Univariate associations: | |||

| Sex (male) | 4.2 | 1.7 – 10.1 | 0.001 |

| Ethnic group (not Chagga) | 0.6 | 0.2 – 1.6 | 0.299 |

| Cognitive impairment (present) | 2.3 | 0.9 – 5.7 | 0.076 |

| Age at assessment (yrs) | 0.7 | 0.3 – 1.6 | 0.365 |

| Education of head of house | 0.7 | 0.2 – 2.2 | 0.528 |

| Early onset of seizures (3yrs or less) | 1.9 | 0.8 – 4.5 | 0.136 |

| Frequent seizures at follow up | 3.2 | 1.3 – 7.5 | 0.009 |

| Seizure type (focal) | 1.1 | 0.4 – 3.2 | 0.794 |

| Multivariable logistic regression model: | |||

| Sex (male) | 5.4 | 2.0 - 14.4 | 0.002 |

| Cognitive impairment (present) | 2.1 | 0.8 – 5.9 | 0.272 |

| Frequent seizures at follow up | 3.9 | 1.5 – 10.6 | 0.010 |

Attention problems in cases were more common in boys, in those with cognitive impairment, early seizure onset and frequent seizures (Table 2). In multivariable logistic regression, attention problems in cases remained significantly associated with being male and having frequent seizures (Table 3).

In controls, disordered behaviour was associated with poor scholastic attainment only (in multivariable analysis, OR 3.9, 95% CI 1.2-12.3, p=0.019). Of the 19 controls with disordered behaviour, eight had poor scholastic attainment. Reasons given for repeating years at school were cognitive impairment in six, being a twin in one and being small in one.

DISCUSSION

Prevalence of behavioural problems in children with epilepsy

This community-based study of children in rural Africa found that behavioural disorders were common in the general population, but were more common in children with active epilepsy.

A range of studies in children with epilepsy from high-income countries (HICs), using varying tests for behaviour disorder, have reported prevalence estimates ranging from 20% to 60%.6-12 The prevalence in our study matched the highest recorded rates for behavioural disorder in children with epilepsy from HICs suggesting that it is a significant co-morbidity of epilepsy in rural Africa. In a comparable study using the Rutter Parent’s Scale from the United Kingdom, behaviour disorder was found in 48% of children attending clinic with epilepsy compared to 13% in age-matched controls.11 The mean score on the Rutter scale was 12.7 in epilepsy compared to 6.5 for controls. The prevalence and degree of behaviour disorder is greater in our study. This might be expected as behavioural problems in children are associated with severe and symptomatic epilepsy, which is more common in low-income countries.31 In the British study, the children with epilepsy did not differ in type of disorder (neurotic or antisocial), which is similar to our study using the Rutter scale, but differs from studies using the CBCL where internalising problems were more frequent.4

There are only a few studies on behaviour disorder in children with epilepsy in the developing world for comparison. In India, a population-based study identified children aged 8 to 12 years from a rural setting who had epilepsy and found 23% had a psychiatric disorder using ICD10 criteria. The mean Rutter score in these children was 14.9 compared to 8.1 in controls.19 A clinic-based study in India, of 132 children from an urban setting aged 4 to 15 years old attending outpatients with a diagnosis of epilepsy, found 54% had significant psychopathology on the CBCL.18 In our study the prevalence of behaviour disorder was higher. This difference is likely to be multifactorial and may be due to different study populations, rural versus urban settings or more symptomatic epilepsy.

Factors associated with behaviour disorder in children with epilepsy

Frequent seizures were associated with behaviour disorder in our study. This is consistent with other studies: in a clinic-based study CBCL scores were markedly increased in children with increased seizure frequency.32 A large prospective study of children with new-onset seizures showed that children with frequent seizures had higher scores on CBCL.33 Frequent seizures may have occurred from patients only taking treatment intermittently or it may be associated with underlying brain disorder.

Behaviour disorder in this study was not significantly associated with cognitive impairment, sex, age or with early onset of seizures. Earlier studies in other settings have found variable associations between behavioural disorder and different risk factors. Several studies have shown an association between cognitive impairment and behaviour disorder. In a cross-sectional clinic-based survey of children with epilepsy, cognitive impairment, defined as need to be withdrawn to some specialised setting, was associated with elevated CBCL scores.3 In another study of children with refractory epilepsy, cognitive impairment and behaviour disorder were associated.32 In contrast, a prospective study in a community hospital found that CBCL scores were related to negative parental attitudes and low acculturation rather than to cognitive ability.34 Lower socio-economic status, sex, seizure type and early age for seizure onset have been associated with behaviour disorder in some studies.6;12;34-37 These differences might reflect methodological variation, differences in study populations and limited sample sizes in some studies.

Most children with epilepsy in our study were on or were started on monotherapy with Phenobarbital. Phenobarbital has previously been associated with more behaviour problems in children with seizures in HICs.38;39 It could be postulated that the high levels of behaviour disorder we found were due to Phenobarbital use even though there was no association in our study with type of treatment at assessment. Studies from low-income countries have found no evidence of more behaviour problems with Phenobarbital use for childhood epilepsy. A double blind randomised controlled trial of 91 children from Bangladesh showed that Phenobarbital had no excess adverse behavioural effects compared to Carbamazepine.40 A randomised controlled trial of Phenobarbital in 94 children from India showed that Phenobarbital use was not associated with more behaviour problems compared to Phenytoin.41 A recent systematic review of randomised controlled trials of Phenobarbital compared to other antiepileptic drugs in childhood epilepsy, found there was no convincing evidence for more behavioural problems with Phenobarbital.42 Therefore it seems unlikely that Phenobarbital was a significant cause of behaviour problems in our study.

There was a higher prevalence of behaviour disorder in the control group in our study compared to controls from other studies (10% to 13% in non-epileptic controls).11 Behaviour disorder in our controls was significantly associated with poor scholastic attainment which may cause frustration. It may also be explained by different population characteristics such as lower socioeconomic status.

Factors associated with attention problems in children with epilepsy

We found that children with epilepsy had significantly more attention problems than controls. These problems were strongly associated in cases with being male and having frequent seizures. Increased attention problems are found in other studies from high-income countries. Several studies have found that children with epilepsy have significantly more attention problems than children with diabetes and asthma.4;5;43 A detailed study of baseline cognitive function in children with new-onset, idiopathic epilepsy demonstrated attention was a particular area of weakness across all seizure types which is consistent with our study.44 In the six months prior to seizure onset, children with epilepsy in one study had more attention problems than healthy siblings.6 There was an even stronger association if seizures occurred prior to formal diagnosis which is consistent with our finding that attention problems were associated with frequent seizures.

We chose the Rutter questionnaire because it correlates highly with other commonly used assessment tools such as the CBCL (correlation coefficient 0.9) 45 and has been found to have good inter-grader reliability46. Its discriminative power for differentiating children with normal and abnormal behaviour has been demonstrated in a large epidemiological study of 8 to 9 year olds in Finland using Receiver Operating Characteristic analysis.47 Many of the Tanzanian children did not attend school so the parent scale was used to give comparable scores for all children. The Rutter questionnaire has been used successfully in children from different cultures including Finland,48 Portugal,49 Kuwait,50 China,51 and Nigeria.52

The Goodenough-Harris Drawing test (GHDT) was used in this study to compare cognitive function as it has been shown to have good reliability and validity compared to other tests of intelligence. Scores from the GHDT in children aged 5 to 15 yrs had a significant positive correlation when compared to the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised(WISC) and the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale 53. These findings were supported by an earlier study showing that scores on the GHDT had a high interrater reliability coefficient (0.96) and correlated significantly with Full Scale IQ on the WISC (r=0.64, p<0.05) 54. The GHDT has also been used successfully in a study of intellectual functioning in a group of South African children 55 . GHDT is one test of cognition and differences in specific areas of cognition and verbal intelligence may have been missed. Further work on cognition and behaviour in this setting would be helpful.

Sources of bias

To minimise ascertainment bias, we aimed to identify all cases of epilepsy in the study group by using a validated screening questionnaire and training enumerators to recognise epilepsy. If children were unavailable initially, repeat visits were offered or they were offered transport for assessment. Case status was confirmed by two paediatric neurologists to ensure reliable diagnosis of epilepsy. Some cases of non-convulsive seizures are likely to have been missed even though community workers had been trained and the screening survey included questions to pick up some of these cases. Controls were well matched in terms of age, sex and socioeconomic status and came from the same population. Follow up rate was high; dropout rate was similar in both cases(8.8%) and controls(11.6%);p=0.49. Cases and controls were assessed using identical methods and questionnaires. The assessors were not blinded to case status but were blinded to seizure variables and other assessment test scores. In analysis, assumptions were made: socioeconomic status was assessed using a surrogate measure and binary variables were assigned to compare cases and controls.

Impact of behavioural problems

Behavioural problems have a major impact on the child and their family in terms of quality of life and education. In a study of children with epilepsy, greater stigma was associated with reduced quality of life and with a more negative attitude, greater worry, poorer self-image and depressive symptoms.56 Using the Impact of Paediatric Epilepsy Scale, greater psychosocial impact was found in those children with lower self-esteem and more emotional problems.57 In our study, behavioural problems alone caused school exclusion in 12% of those cases not attending school regularly. Defining other factors affecting school attendance in this population is currently being investigated. Poor attention may limit progress at school: poor academic progress has been associated particularly with specific rather than generalised cognitive dysfunction especially verbal-language and attention-concentration abilities in children with epilepsy.58

CONCLUSIONS

This community-based study of children with epilepsy in rural Africa demonstrated significant co-morbidity from behaviour disorder and attention problems. Behaviour and attention problems were strongly associated with having epilepsy and frequent seizures. .Providing behaviour assessment and appropriate intervention programmes for children with epilepsy may reduce the burden of behaviour disorder in this setting.

What this paper adds.

The prevalence of behaviour problems in children with epilepsy in rural Africa is high.

These children with epilepsy have particular problems with attention.

In these children with epilepsy, behaviour problems are associated with frequent seizures.

Acknowledgements

Wellcome-Trust-UK, Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust and Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre supported this study. We would like to thank all the health-care workers, officials, carers, and family members who assisted in identification of patients, examination and assessment. Prof. CRCJ Newton holds a Wellcome Trust Career post in Clinical Tropical Medicine (No. 070114).

Reference List

- 1.World Health Organization Epilepsy in the WHO Africa region, bridging the gap: the global campaign against epilepsy “out of the shadows. 2004. Ref Type: Report.

- 2.Graham P, Rutter M. Organic brain dysfunction and child psychiatric disorder. Br Med J. 1968;3:695–700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5620.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keene DL, Manion I, Whiting S, et al. A survey of behavior problems in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;6:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin JK, Huster GA, Dunn DW, Risinger MW. Adolescents with active or inactive epilepsy or asthma: a comparison of quality of life. Epilepsia. 1996;37:1228–1238. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoare P, Mann H. Self-esteem and behavioural adjustment in children with epilepsy and children with diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:859–869. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austin JK, Harezlak J, Dunn DW, Huster GA, Rose DF, Ambrosius WT. Behavior problems in children before first recognized seizures. Pediatrics. 2001;107:115–122. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caplan R, Siddarth P, Gurbani S, Ott D, Sankar R, Shields WD. Psychopathology and pediatric complex partial seizures: seizure-related, cognitive, and linguistic variables. Epilepsia. 2004;45:1273–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.58703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunn DW, Austin JK, Huster GA. Behaviour problems in children with new-onset epilepsy. Seizure. 1997;6:283–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn DW, Austin JK, Huster GA. Symptoms of depression in adolescents with epilepsy. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1132–1138. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199909000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ettinger AB, Weisbrot DM, Nolan EE, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in pediatric epilepsy patients. Epilepsia. 1998;39:595–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoare P. The development of psychiatric disorder among schoolchildren with epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1984;26:3–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1984.tb04399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ott D, Caplan R, Guthrie D, et al. Measures of psychopathology in children with complex partial seizures and primary generalized epilepsy with absence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:907–914. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoie B, Sommerfelt K, Waaler PE, Alsaker FD, Skeidsvoll H, Mykletun A. Psychosocial problems and seizure-related factors in children with epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48:213–219. doi: 10.1017/S0012162206000454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freilinger M, Reisel B, Reiter E, Zelenko M, Hauser E, Seidl R. Behavioral and emotional problems in children with epilepsy. J Child Neurol. 2006;21:939–945. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210110501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baum KT, Byars AW, deGrauw TJ, et al. Temperament, family environment, and behavior problems in children with new-onset seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;10:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baum KT, Byars AW, deGrauw TJ, et al. The effect of temperament and neuropsychological functioning on behavior problems in children with new-onset seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;17:467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodenburg R, Marie MA, Dekovic M, Aldenkamp AP. Family predictors of psychopathology in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:601–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Datta SS, Premkumar TS, Chandy S, et al. Behaviour problems in children and adolescents with seizure disorder: associations and risk factors. Seizure. 2005;14:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hackett R, Hackett L, Bhakta P. Psychiatric disorder and cognitive function in children with epilepsy in Kerala, South India. Seizure. 1998;7:321–324. doi: 10.1016/s1059-1311(98)80026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adewuya AO, Ola BA. Prevalence of and risk factors for anxiety and depressive disorders in Nigerian adolescents with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;6:342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gureje O. Interictal psychopathology in epilepsy. Prevalence and pattern in a Nigerian clinic. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:700–705. doi: 10.1192/bjp.158.5.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.AMMP Enumeration and Description of Project Surveillance Areas. Tanzania Ministry of Health adult Morbidity and Mortality Project (AMMP) 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 23.ILAE Commission Report The epidemiology of the epilepsies: future directions. International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1997;38:614–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guidelines for epidemiologic studies on epilepsy. Commission on Epidemiology and Prognosis, International League Against Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1993;34:592–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Placencia M, Sander JW, Shorvon SD, Ellison RH, Cascante SM. Validation of a screening questionnaire for the detection of epileptic seizures in epidemiological studies. Brain. 1992;115(Pt 3):783–794. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.3.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rutter M. A Children’s Behaviour Questionnaire for Completion by Teachers: Preliminary Findings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1967;8:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1967.tb02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyle M, Jones C. Selecting measures of emotional and behavioural disorders of childhood for use in general populations. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1985;26:137–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1985.tb01634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fombonne E. The Child Behaviour Checklist and the Rutter Parental Questionnaire: a comparison between two screening instruments. Psychol Med. 1989;19:777–785. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700024387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris DB. Children’s Drawings as Measures of Intellectual Maturity. 1963.

- 30.Adult Morbidity and Mortality Project Team Suitability of Participatory Methods to generate variables for inclusion in an income poverty index. Working Paper No.9. 2003. Ref Type: Report.

- 31.Munyoki G, Edwards T, White S, et al. Clinical and neurophysiologic features of active convulsive epilepsy in rural Kenya: A population-based study. Epilepsia. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabaz M, Lawson JA, Cairns DR, et al. Validation of the quality of life in childhood epilepsy questionnaire in American epilepsy patients. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4:680–691. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin JK, Dunn D, Caffrey H, Perkins S, Harezlak J, Rose DF. Recurrent Seizures and Behaviour Problems in Children with First Recognised Seizures: A Prospective Study. Epilepsia. 2002;43:1564–1573. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.26002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitchell WG, Scheier LM, Baker SA. Psychosocial, behavioral, and medical outcomes in children with epilepsy: a developmental risk factor model using longitudinal data. Pediatrics. 1994;94:471–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoie B, Mykletun A, Sommerfelt K, Bjornaes H, Skeidsvoll H, Waaler PE. Seizure-related factors and non-verbal intelligence in children with epilepsy. A population-based study from Western Norway. Seizure. 2005;14:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oostrom KJ, van Teeseling H, Smeets-Schouten A, Peters A, Jennekens-Schinkel A. Three to four years after diagnosis: cognition and behaviour in children with ‘epilepsy only’. A prospective controlled study. Brain. 2005;128:1546–1555. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stores G. Scholl-children wtih Epilepsy at Risk for Learning and Behaviour Problems. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1978;20:502–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1978.tb15256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de SM, MacArdle B, McGowan M, et al. Randomised comparative monotherapy trial of phenobarbitone, phenytoin, carbamazepine, or sodium valproate for newly diagnosed childhood epilepsy. Lancet. 1996;347:709–713. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolf SM, Forsythe A. Behavior disturbance, phenobarbital, and febrile seizures. Pediatrics. 1978;61:728–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banu SH, Jahan M, Koli UK, Ferdousi S, Khan NZ, Neville B. Side effects of phenobarbital and carbamazepine in childhood epilepsy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;334:1207. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39022.436389.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pal DK, Das T, Chaudhury G, Johnson AL, Neville BG. Randomised controlled trial to assess acceptability of phenobarbital for childhood epilepsy in rural India. Lancet. 1998;351:19–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)06250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pal DK. Phenobarbital for childhood epilepsy: systematic review. Paediatr Perinat Drug Ther. 2006;7:31–42. doi: 10.1185/146300905X75361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunn DW, Austin JK, Perkins SM. Prevalence of psychopathology in childhood epilepsy: categorical and dimensional measures. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51:364–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhise VV, Burack G, Mandelbaum DE. Baseline cognition, behaviour, and motor skills in children with new-onset, idiopathic epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:22–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sourander A. Parent, teacher, and clinical ratings on admission to child psychiatric inpatient treatment. Nord J Psychiatry. 1997;51:365–370. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berg I, Lucas C, McGuire R. Measurement of Behaviour Difficulties in Children Using Standard Scales administered to mothers by computer: Reliability and Validity. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1992;1:14–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02084430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kresanov K, Tuominen J, Piha J, Almqvist F. Validity of child psychiatric screening methods. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;7:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s007870050052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sourander A, Klomek AB, Niemela S, et al. Childhood predictors of completed and severe suicide attempts: findings from the Finnish 1981 Birth Cohort Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:398–406. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pereira AT, Maia BR, Marques M, et al. Factor structure of the Rutter Teacher Questionnaire in Portuguese children. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2008;30:322–327. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462008000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Turkait FA, Ohaeri JU. Psychopathological status, behavior problems, and family adjustment of Kuwaiti children whose fathers were involved in the first gulf war. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2:12. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wong CK. The Rutter Parent Scale A2 and Teacher Scale B2 in Chinese. I. Translation study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;77:724–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb05194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abiodun OA, Tunde-Ayinmode MF, Adegunloye OA, et al. Psychiatric Morbidity in Paediatric Primary Care Clinic in Ilorin, Nigeria. J Trop Pediatr. 2010 doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmq072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abell SC, von Briesen PD, Watz LS. Intellectual evaluations of children using human figure drawings: an empirical investigation of two methods. J Clin Psychol. 1996;52:67–74. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199601)52:1<67::AID-JCLP9>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gayton WF, Tavormina J, Evans EH, Scheh J. Comparative validity of Harris’ and Koppitz’ scoring systems for human-figure drawings. Percept Mot Skills. 1974;39:369–370. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loxton H, Mostert J, Moffatt D. Screening of intellectual maturity: exploring South African preschoolers’ scores on the Goodenough-Harris Drawing Test and teachers’ assessment. Percept Mot Skills. 2006;103:515–525. doi: 10.2466/pms.103.2.515-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Austin JK, MacLeod J, Dunn DW, Shen J, Perkins SM. Measuring stigma in children with epilepsy and their parents: instrument development and testing. Epilepsy Behav. 2004;5:472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Camfield C, Breau L, Camfield P. Impact of pediatric epilepsy on the family: a new scale for clinical and research use. Epilepsia. 2001;42:104–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.081420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Seidenberg M, Beck N, Geisser M. Neuropsychological correlates of academic underachivement of children with epilepsy. J Epilepsy. 1988;1:23–29. [Google Scholar]