Abstract

Polµ is the only DNA polymerase equipped with template-directed and terminal transferase activities. Polµ is also able to accept distortions in both primer and template strands, resulting in misinsertions and extension of realigned mismatched primer terminus. In this study, we propose a model for human Polµ-mediated dinucleotide expansion as a function of the sequence context. In this model, Polµ requires an initial dislocation, that must be subsequently stabilized, to generate large sequence expansions at different 5′-P-containing DNA substrates, including those that mimic non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) intermediates. Our mechanistic studies point at human Polµ residues His329 and Arg387 as responsible for regulating nucleotide expansions occurring during DNA repair transactions, either promoting or blocking, respectively, iterative polymerization. This is reminiscent of the role of both residues in the mechanism of terminal transferase activity. The iterative synthesis performed by Polµ at various contexts may lead to frameshift mutations producing DNA damage and instability, which may end in different human disorders, including cancer or congenital abnormalities.

INTRODUCTION

Maintaining the integrity of the DNA sequence is essential for all living cells, which is notably allowed by maximizing fidelity during DNA replication and performing accurate repair of damaged DNA (1). Those processes require a large number of proteins including specialized DNA polymerases. DNA polymerases have been categorized into four different groups attending to their biochemical properties and to the biological processes in which they are involved. They are grouped by their primary sequence homology into family A, B, Y and X. Among them, only X family DNA polymerases (PolX) are devoted to DNA repair, being evolutionarily conserved in prokaryotes, eukaryotes and archaea (2). DNA polymerases of the X family, which in mammals include DNA polymerase beta (Polß), lambda (Polλ), mu (Polµ) and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), are structurally related enzymes specialized in DNA repair pathways involving gaps and double-strand breaks (DSBs) [reviewed in (3)].

Human Polµ, consisting of 494 amino acids, has 41% identity to TdT, its closest homologue in the family. The structural similarities with TdT include a nuclear localization signal at the N-terminus, followed by a BRCT domain and the conserved Polß core (4). Regarding the biochemical properties, Polµ displays both terminal transferase and DNA-dependent DNA polymerization activities (4,5). The strong enhancement of these two activities by manganese ions, and the lack of proofreading, make Polµ a low-fidelity polymerase with a strong mutator behaviour. This mutator activity is further enhanced by its lack of sugar discrimination, allowing the use of both dNTPs and rNTPs (6,7). Moreover, two hallmarks of Polµ activity are: (i) the capacity to induce/accept template distortions, in order to realign imperfectly paired DNA primers (8,9); and (ii) the capacity to bridge DNA ends with minimal or null complementary, contributing to the efficiency of end-joining by performing either templated or untemplated insertions at the 3′ end termini (10,11). Likewise, Polµ is able to perform DNA synthesis despite the presence of mismatched nucleotides near the primer terminus (12). The combination of all these properties make Polµ well-suited for a role in the non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) DNA repair mechanism, as it was early proposed (5,9), and strongly supported by the demonstration of direct interactions of Polµ with NHEJ factors (13–15), and by analysis of Polµ deficiency in various in vivo systems (13,16–20).

On the other hand, this enzymatic versatility regarding the use and interactions with DNA and nucleotide substrates are the basis for Polµ to exhibit a high misincorporation rate, being one of the most unfaithful polymerases known in higher eukaryotes (4). The strong mutator activity of Polµ when copying a DNA template resides on its ability to create or accept distortions and realignments of both primer and template strands, being largely dependent on sequence context (8,9). Thus, it was found that many of the alleged misincorporations by Polµ, including −1 nt frameshift errors, were the result of base-pairing between the incoming nucleotide and complementary positions close to the templating base (9,21). Analysis of different sequence contexts showed that the most extreme mutator behaviour by Polµ corresponded to a ‘slippage’ mechanism [(8); see Supplementary Figure S1], described initially for Polß on a template/primer (22). This slippage mechanism has been shown to be the cause of terminal transferase additions by Polµ in the context of heavily damaged DNA, such as substrates containing AAF adducts or abasic sites (12,23).

Tandem DNA repeats are mutational hotspots in the genome which undergo frequent length changes due to insertions (usually referred to as expansions) or deletions of repeat units. Variations in length of some repeats can produce phenotypic differences that are known to cause a large number of diseases (24,25). During the past decade several groups have demonstrated that the molecular mechanisms of repeat expansion or deletion are mediated by DNA replication, repair and recombination machineries (25–28). Methyl-directed mismatch repair (MMR) (29,30), nucleotide excision repair, base excision repair (31–33), transcription and DNA polymerase proofreading have been described to be involved in the molecular mechanisms of these unstable sequences (24,34), among other genetic factors. Moreover, the non-conventional DNA conformation of the repeated sequences could increase DNA polymerase stalling, facilitating strand slippage and producing mutagenesis and associated diseases (27).

In this work we describe the contribution of a human DNA repair polymerase, Polµ, to the expansion of dinucleotides, consistently present throughout the whole genome, as a side effect of its role during NHEJ repair of double-strand breaks in DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA and proteins

Unlabelled ultrapure dNTPs and [γ-32P] ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. Synthetic DNA oligonucleotides were obtained from Invitrogen: D (5′-ACGACGGCCAGT) was used as downstream oligonucleotide; 3′-(GAC)2 (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTCAGCAGGTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-(GTC)2 (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTCTGCTGGTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-(AAG)2 (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTGAAGAAGTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-(CTT)2 (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTTTCTTCGTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-(CAG)2 (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTGACGACGTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-(GAA)2 (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTAAGAAGGTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-GAA (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTAAGGTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-AAA (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTAAAGTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-CAA(1) (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTAACGTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-CAA(2) (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTAACCTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-TAA (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTAATGTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-CTT (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTTTCCTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-CCC (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTCCCCTACTCACTGTGATC), 3′-CGG (5′-ACTGGCCGTCGTGGCCTACTCACTGTGATC) were used as templates; P1 (5′-GATCACAGTGAGTAC), P2 (5′-GATCACAGTGAGTAG), P3 (5′-GATCACAGTGAGTACCC) and P4 (5′-GATCACAGTGAGTACCCC) were used as primers. Oligonucleotide D contains a phosphate at 5′-end. DNA oligonucleotides used as primers (P1 and P2) were labelled at its 5′-end with [γ32P-ATP] and T4 polynucleotide kinase. To construct the different gapped molecules used in the polymerization assays, P1 was simultaneously hybridized to a downstream oligonucleotide D and one of the following template oligonucleotides: 3′-(GAC)2, 3′-(GTC)2, 3′-(AAG)2, 3′-(CTT)2, 3′-(CAG)2, 3′-(GAA)2, 3′-(GAA)1, 3′-(AAA)1, 3′-(CAA)1 or 3′-(TAA)1; P2 was simultaneously hybridized to D and one of the following template oligonucleotides: 3′-CAA, 3′-CTT, 3′-CCC or 3′-CGG; P3 and P4 were hybridized to D and 3′-CGG. For NHEJ assays, oligonucleotides D3 (5′-CCCTCCCTCCGCGGC), D3BB1 (5′-CCCTCCCTCCGCGGAC), D3BB2 (5′-CCCTCCCTCCGCGAGC), D3T (5′-CCCTCCCTCCGCGGT), D3TT (5′-CCCTCCCTCCGCGGTT) and D3G (5′-CCCTCCCTCCGCGGG) were used as labelled primers, hybridized to oligonucleotide 5′-GGGAGGGAGGC, while oligonucleotides D4 (5′-CGCGCACTCACGTCCCGGCC) or D4-AA (5′-CGCGCACTCACGTCCCAACC) were hybridized with the 5′-phosphate-containing D1 (5′-GGGACGTGAGTGCGCG) to form a template/downstream substrate. Hybridizations were performed in the presence of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5 and 0.3 M NaCl. All the oligonucleotides described above were purified by electrophoresis in 8 M urea/20% polyacrylamide gels. T4 polynucleotide kinase and T4 DNA ligase were from New England Biolabs. Both highly purified wild-type human Polµ and wild-type human Polλ were obtained as previously described (4,35). Purification of mutants H329G, R387K and R387A was performed as described (10).

Purification of human Polß

Escherichia coli cells expressing human Polß were ground with alumina and the resulting lysate was centrifuged and cleaned by precipitation with ammonium sulphate. The precipitate was subjected to phosphocellulose chromatography followed by HiTrap Heparin (Pharmacia Biotech) chromatography. The column was loaded onto a glycerol gradient and centrifuged at 62.000 rpm for 24 h, and fractions were examined in Coomassie Blue-stained gels and tested for DNA polymerase activity on activated (DNaseI treated) DNA.

DNA polymerization assays

Different DNA substrates containing 5′-P labelled primers (described above) were incubated with the indicated amounts of either the wild-type or mutant human Polµ, human Polλ or human Poß, in each case. The reaction mixture, in 20 µl, contained 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 4% glycerol and 0.1 mg/ml BSA, in the presence of 4 nM of the indicated DNA polymerization substrate, 50 µM of the dNTP or the mix of dNTPs indicated in each case, 2 mM MgCl2 and amounts of DNA polymerase as indicated in the figure legends. After the incubation indicated in each case, reactions were stopped by adding gel loading buffer [95% (v/v) formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% (w/v) xylene cyanol and 0.1% (w/v) bromophenol blue]. Samples were analysed by 8 M urea/20% PAGE and either autoradiography or Phosphorimager scanning.

3D-modeling

The different conformations of selected residues of Polµ were analysed by using the Swiss PDB-Viewer (http://www.expasy.ch/spdbv/) and MacPymol (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrödinger, LLC, http://www.pymol.org/).

RESULTS

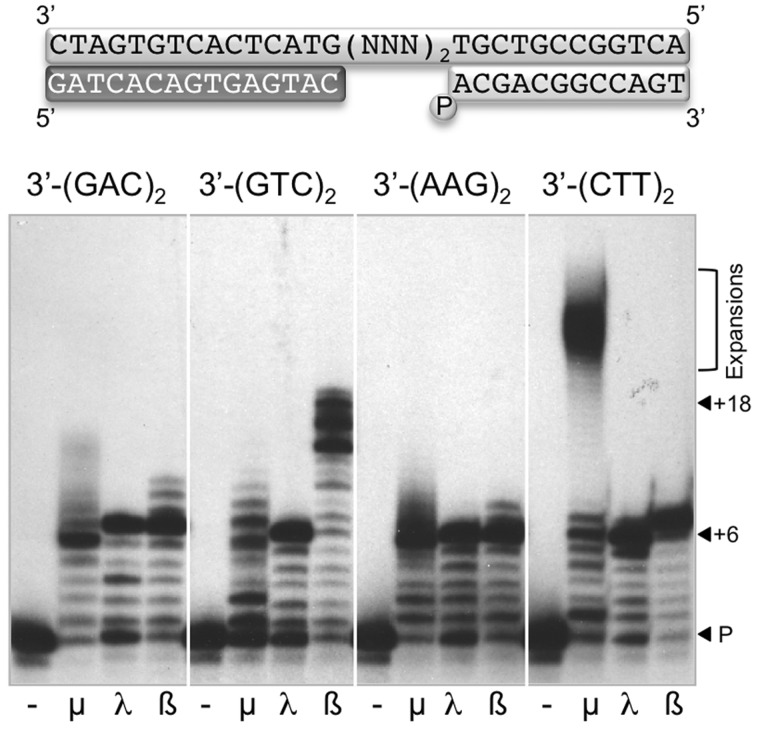

Polµ, but neither Polλ nor Polß, produces large sequence expansions when a specific repeated trinucleotide sequence is used as a template

Polµ can act as a mutator polymerase, based on its ability to realign and dislocate DNA chains during polymerization, whereas Polλ and Polß, belonging to the same family as Polµ, are not so versatile and promiscuous in the use of DNA substrates (36). All three polymerases have a marked preference for 5′-P gapped molecules, as the 8 kDa domain strongly interacts with this group at the 5′-end of the downstream chain (35,37,38), improving binding stability. Thus, we addressed if any of these DNA polymerases could generate triplet repeat expansions in the context of a gap. According to the substrate preferences of these polymerases, four different DNA substrates containing a 6-nt gap were designed, with different trinucleotide sequences as templates, each one repeated twice (see scheme in Figure 1). Expansion of triplet repetitions of the sequence 3′-GAC (or its complementary chain 3′-GTC) are associated to Huntington’s disease; triplet repeat expansions of 3′-AAG (or its complementary sequence 3′-CTT) are related to Friedrich’s ataxia. Polymerization reactions were assayed on these molecules, in the presence of either Polµ, Polλ or Polß, and the complementary dNTPs needed in each case (Figure 1). In general, Polλ and Polß filled the gap and then polymerization stopped (+6 product). In the case of 3′-(GTC)2, Polß displayed a significant strand-displacement capacity and efficiently continued adding nucleotides after filling the gap (+18 product). This imprecise gap-filling by Polß has been already described (39). Interestingly, Polµ was eventually able to continue polymerization, producing extra additions that could be also originated via strand displacement. However, this behaviour is very remarkable in the case of 3′-(CTT)2, where Polµ fills the gap and then efficiently generates a very large DNA expansion as a final product. The main difference between this sequence and the others is the presence of a dinucleotide (TT) in the template strand at the end of the gap.

Figure 1.

Polµ generates a large sequence expansion on a DNA gap with a specific trinucleotide sequence. In the scheme, the template sequence indicated (NNN) corresponds to the trinucleotides shown below. Subindex ‘2’ indicates that each trinucleotide sequence is twice repeated at the gap. Polymerization reactions (described in ‘Materials and Methods’ section) were performed in the presence of 4 nM of the indicated DNA substrate in each case, 2 mM MgCl2, 270 nM of each polymerase and 50 µM mix dNTPs (using the complementary nucleotides to the gap sequence in each case). After 1 h incubation at 30°C, polymerization products were analysed by electrophoresis on 20% polyacrylamide/8 M urea gels and autoradiography. P indicates the unextended primer; +6 the elongated product upon complete gap-filling; +18 the fully elongated product after gap-filling and strand displacement; the products of nucleotide expansion are indicated with a bracket.

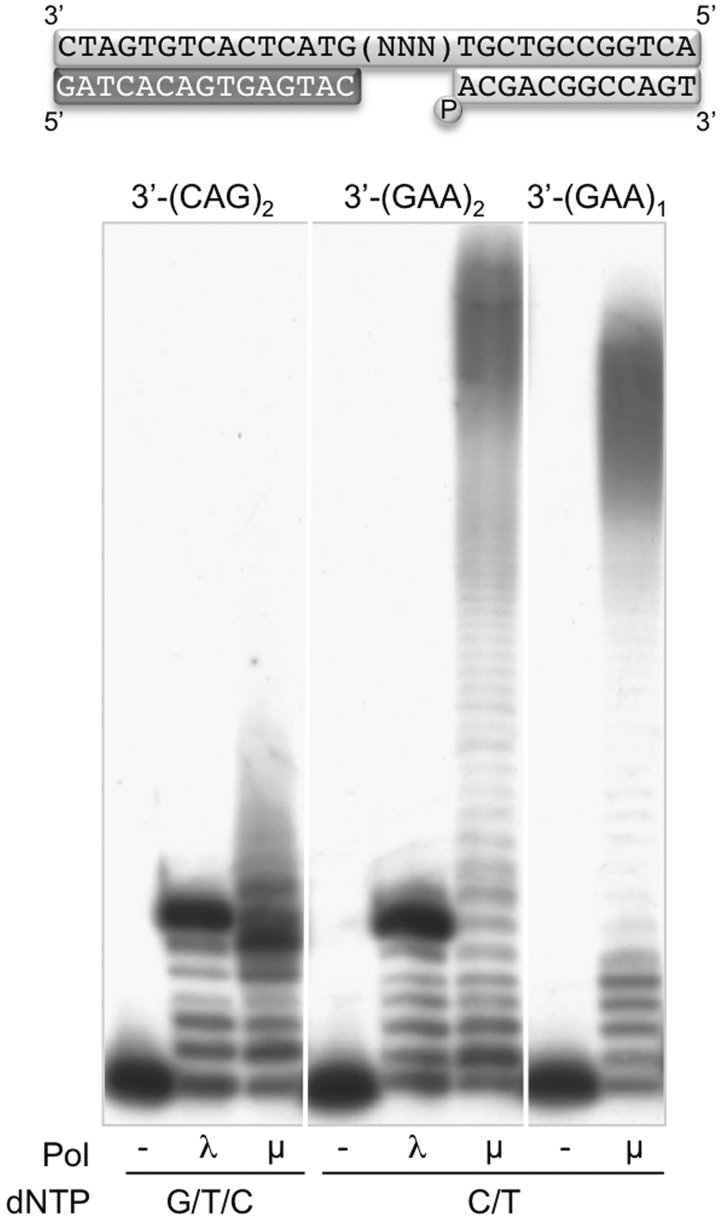

Polµ requires a dinucleotide at the end of the template sequence to produce large sequence expansions

Taking into account the dislocation capacity of Polµ, strongly driven by the presence of dinucleotides in the template strand, we wanted to confirm if the presence of a repeated nucleotide at the end of the gap determines the capability of Polµ to produce sequence expansions. For this, two new DNA substrates containing 6-nt gaps were chosen: the first, with the template sequence 3′-(CAG)2, with no repeated nucleotides, and the second 3′-(GAA)2, which maintains the presence of a duplicated nucleotide at the end of the gap (Figure 2). We compared the behaviour of Polµ and Polλ on these substrates, providing the complementary nucleotides needed in each case. As shown in Figure 2, in both cases Polλ filled the 6-nt gap and then polymerization stopped. Conversely, Polµ was able to continue polymerization beyond the expected +6 product in both cases, producing a large sequence expansion only in the case of confronting a repeated nucleotide (AA) at the end of the gap (Figure 2). Thus, this iteration is a relevant requirement for Polµ in order to produce promiscuous elongation.

Figure 2.

A repeated nucleotide at the end of a gap is required to generate large sequence expansions. In the scheme, the template sequence indicated (NNN) corresponds to the trinucleotides shown below, that could be present twice (subindex 2) or only once (subindex 1). Polymerization reactions (described in ‘Materials and Methods’ section) were performed in the presence of 4 nM of the indicated DNA substrate in each case, 2 mM MgCl2, 270 nM of either Polλ or Polµ and 50 µM mix dNTPs (using the complementary nucleotides to the gap sequence in each case). After 1 h incubation at 30°C, polymerization products, including sequence expansions, were analysed by electrophoresis on 20% polyacrylamide/8 M urea gels and autoradiography.

Next we addressed if the repetition of the trinucleotide was specifically needed for Polµ to produce the expansion. For that, Polµ was assayed on a DNA substrate having only one repetition of the triplet sequence, forming a 3-nt gap containing the sequence 3′-GAA, that maintains the requirement of a repeated nucleotide at the end of the gap. As shown in Figure 2, when complementary nucleotides (dC and dT) were provided, Polµ generated again a large sequence expansion, demonstrating that the dinucleotide is required only once at the end of the template strand.

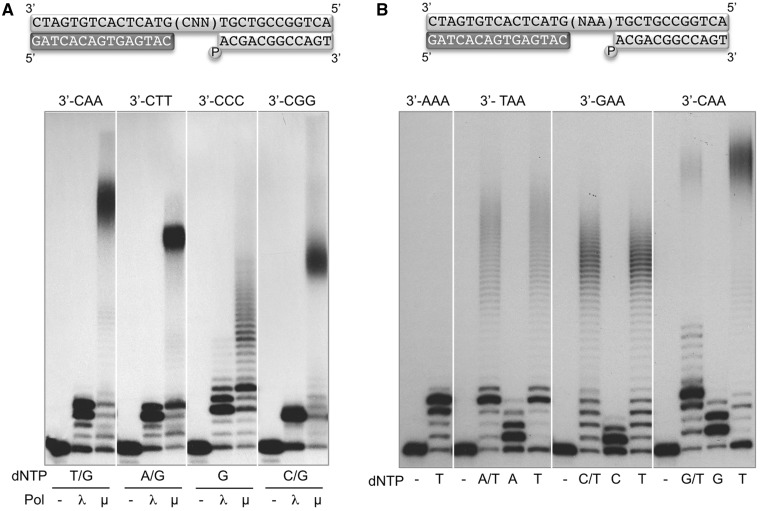

An initial dislocation and remaining distortion are necessary for the generation of large sequence expansions by Polµ

By using additional sequence contexts, Polµ was confirmed to be able to produce large sequence expansions of the four different duplicated nucleotides (AA, TT, CC and GG) at the end of a 3-nt gap (Figure 3A). Polλ was used as negative control of expansion also in this experiment. Interestingly, in the 3′-CCC gapped substrate Polµ had a different behaviour than on the other 3 DNA substrates: no large sequence expansion was produced, but only a few more additions were observed once the gap had been filled. Strikingly, the behaviour appears to be the opposite in the case of Polλ, which produced some significant expansion only when copying the sequence 3′-CCC, perhaps the most prone to facilitate slippage after gap-filling. Thus, the modest outcome of the reaction on the 3′-CCC substrate indicates a new specific feature needed for the generation of large expansions by Polµ: the nucleotide at the first (n + 1) template position must differ from that forming the repetition in order to obtain the maximal sequence expansion. This demand at the trinucleotide sequence suggests that the expansion reaction begins with an initial dislocation reaction, a very particular mechanism described for Polµ (8,9), producing a −1 frameshift during the initial step of the gap-filling reaction: Polµ’s propensity to dislocate the template strand is such that it preferentially inserts the nucleotide complementary to the n + 2 position of the template, both in an open template/primer and in a 2-nt gap (Supplementary Figure S1), either in the conditions that favour a mechanism of primer slippage (Supplementary Figure S1A) or when this is not possible due to the sequence context (Supplementary Figure S1B). This second mechanism, ‘dNTP-selection-mediated’, is not as efficient as the ‘slippage-mediated’ alternative, but is considerably improved when the substrate is a small 5′-P-containing gap (Supplementary Figure S1C).

Figure 3.

A distortion upstream to the dinucleotide is a prerequisite for the formation of Polµ-mediated sequence expansions during gap-filling. (A) In the scheme, the template sequence indicated (CNN) corresponds to the four trinucleotides shown below. The first base at the trinucleotide is always dC, followed by the four different homo-dinucleotides. Polymerization reactions (described in ‘Materials and Methods’ section) were performed in the presence of 4 nM of the indicated DNA substrate in each case, 2 mM MgCl2, 270 nM of either Polλ or Polµ and 50 µM mix dNTPs (using the complementary nucleotides to the gap sequence in each case). (B) Importance of the first nucleotide of the triplet (NAA) for the efficiency of expansion by Polμ. The gap sequence used and the different combinations of nucleotides provided, were as indicated. Polymerization reactions were performed as in (A). After 1 h incubation at 30°C, polymerization products were analysed by electrophoresis on 20% polyacrylamide/8 M urea gels and autoradiography.

To further understand the requirements for the special mechanism of dinucleotide expansion by Polµ, we evaluated both the impact of the sequence at the first position of the gap, and also the necessity of providing either the 2 nt complementary to the sequence of the gap, or only the one complementary to the dinucleotide (the only one needed if dislocation occurs). We used four different 3-nt gapped DNA substrates (Figure 3B), with the same terminal repetition (AA), but different nucleotide at the n + 1 position of the gap. As shown in Figure 3B, a large expansion is obtained in the case of the 3′-GAA substrate, and no difference is obtained when providing either dC + dT or only dT, indicating that in most of the cases the first templating base (dG) is not copied. Such a preferential dislocation is compatible with a slippage-mediated mechanism, since the 3′-terminus of the primer strand (dC) could be realigned and matched to the first templating base (dG) [(40); see also Supplementary Figure S1A]. Moreover, large expansions on the gap sequences 3′-TAA and 3′-CAA are also obtained by providing only dTTP. In these two cases, the dTTP insertion event triggering expansion would be compatible with a dNTP-selection-mediated dislocation [(8); see Supplementary Figure S1B]. This mechanism dominates insertion in the 3′-TAA gap, as the addition of dATP + dTTP has minimal, if any, effect on expansion. Conversely, expansions on the 3′-CAA gap are significantly inhibited by the simultaneous addition of dGTP and dTTP. These results point to the efficiency of dislocation as an important factor determining the expansion capability, which could be also affected by an unbalanced concentration of the deoxynucleotide precursors.

In agreement with our previous observations using the 3′-CCC substrate (Figure 2), Polµ did not produce a significant expansion on the 3′-AAA substrate. Assuming that an initial dislocation event can also occur, an important difference in these two cases is that, after complete gap-filling, the nascent chain could be completely realigned, producing a perfectly matched +3 product. In this case, expansion seems to be precluded, as evidenced by the minimum extension of the primer over the size of the gap. Therefore, an initial dislocation of the template only triggers dinucleotide expansion if the distortion remains after gap-filling. Further analysis showed that the necessary distortion that allows generation of the observed sequence expansions might be present in the substrate prior to the arrival of the polymerase, triggering dinucleotide expansions even at single nicks in DNA (Supplementary Figure S2). As it will be evaluated later in this section, that is particularly relevant considering the in vivo situations where Polµ deals with substrates containing distortions and/or misalignments, caused by microhomology search during the bridging of two DNA ends in NHEJ reactions. The presence of a 5′-P group at the downstream strand of the gap is also a prerequisite for the generation of these nucleotide expansions, as shown in Supplementary Figure S3. This observation was expected since the 5′-P is a main anchor point for Polµ on the DNA substrate (38).

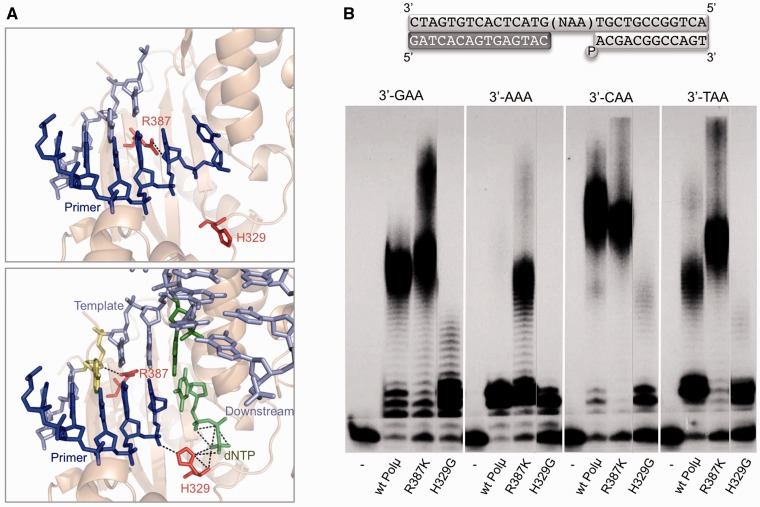

Specific residues regulating the expansion of repeated sequences

Polμ is an exceptional enzyme since it is the only DNA polymerase able to display template-independent (terminal transferase) and template-dependent activities (4,5). Recent structure–function studies have shed light on the molecular basis for the terminal transferase activity: on the one hand, Polµ contains a flexible piece, Loop 1, which is able to undergo conformational changes, acting as a pseudo-template that allows incorporation of nucleotides in the absence of template information (41), or during NHEJ of some incompatible ends (15). Moreover, the crystal structure of Polμ in ternary complex with gap DNA and deoxynucleotide (42) allowed to infer that a specific histidine residue (His329 in Polμ and His342 in TdT; absent in Polß and Polλ) could play an important role to overcome the rate-limiting step of untemplated polymerization, allowing terminal transferase activity to occur. In fact, this residue, involved in the proper positioning of the primer terminus and the incoming nucleotide (Figure 4A), was shown to be critical during template-independent polymerization but also in template-directed reactions associated to NHEJ of short incompatible ends (10,42). Furthermore Arg387 is a specific DNA-binding ligand (Figure 4A) that limits untemplated nucleotide additions and is thus responsible for the lower terminal transferase activity of Polμ in comparison to TdT (10).

Figure 4.

His329 allows while Arg387 limits sequence expansions by Polµ. (A) Top: Model of Polµ bound to a template/primer substrate in which the 3′-protruding primer terminus is in an unproductive position, occupying the incoming dNTP site. Residue Arg387, in a conformation modelled to match that of the lysine present in TdT in a similar structure, is contacting the primer impeding its backwards translocation. His329, modelled in the conformation observed for the same residue in the crystal of TdT bound to an ssDNA primer, is not making any contacts with the DNA substrate. Bottom: Crystal structure of Polµ bound to a gapped DNA substrate and incoming dNTP. His329 has rotated and is contacting both incoming dNTP and primer terminus, helping to reposition the latter. Arg387 is now contacting the template strand (n − 3 position; indicated in yellow), having allowed the movement backwards of the primer. DNA substrates are indicated in dark (primer strand) and light (template and downstream strand) blue. Incoming dNTP is indicated in green. (B) In the scheme, the template sequence indicated (NAA) corresponds to the four trinucleotides shown below. The two last bases always form the dinucleotide AA, preceded by any of the four different nucleotides. Polymerization reactions (described in Materials and Methods section) were performed in the presence of 4 nM of the indicated DNA substrate in each case, 2 mM MgCl2, 270 nM Polµ and 50 µM mix dNTPs (using the complementary nucleotide to the dinucleotide AA). After 1 h incubation at 30°C, polymerization products were analysed by electrophoresis on 20% polyacrylamide/8 M urea gels and autoradiography.

To study the relevance of both residues in the expansion of repeated sequences we used two mutants: H329G (with a strongly reduced terminal transferase activity) and R387K (displaying an augmented terminal transferase activity). The selected mutants, obtained and purified as described (10), were tested on the set of gapped DNA substrates that maintain the same repetition (AA) at the 5′-end, but differ in the nucleotide at the n + 1 position in the gap. As shown in Figure 4B, the wild-type Polµ produced and expansion pattern similar to that described before (Figure 3B). Strikingly, mutant H329G was only able to fill the different gaps, displaying very minor or even undetectable levels of sequence expansions on these substrates. Mutant R387K, on the other hand, produced a level of expansions similar in most cases to that of the wild-type enzyme (Figure 4B), but, remarkably, was also able to produce a significant expansion in the case of the 3′-AAA substrate. This was striking, as the latter substrate does not allow formation of the distortion that was an obligatory requirement for producing expansions by the wild-type enzyme. These results support our initial hypothesis that Arg387 has a constitutive role in preventing slippage of the primer in each round of the catalytic cycle, through a direct contact between this residue and the −2 position of the primer strand that can be observed in the ternary complex of Polµ (Figure 4A). Mutation of this arginine to lysine favours expansion in the absence of distortions through a mechanism that facilitates the backwards translocation of the primer strand. In the case of distortion-mediated expansions, where the primer strand is not properly oriented, Arg387 cannot exert its ‘braking’ role. Mutation of arginine to lysine in this context does not increase the sequence expansions any further since the control mechanism is already compromised.

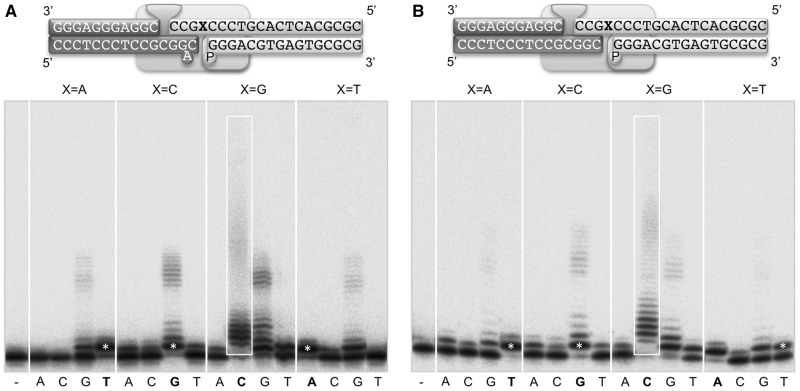

Impact of the sequence expansions during end-joining reactions

As noted before, dinucleotide expansion could be generated by Polµ as a by-product of its physiological role of repairing DSBs by the NHEJ pathway. We wanted to check whether the sequence expansion capacity exhibited by Polµ in the context of DNA-gapped substrates is also demonstrated during NHEJ reactions that include the formation of short gaps, and if the requirements detected during gap-filling (i.e. the formation of a distortion upstream of the polymerization point, and the presence of a dinucleotide in the template strand) also need to be met during end-joining of two DNA ends.

For this we used a tailored set of 3′-protruding NHEJ substrates whose protrusions provide, once bridged by the polymerase, a microhomology of 3 base-pairs, the flipping-out of a nucleotide at the −1 position of the primer strand, and the formation of two 1-nt gaps at both sides of the connection (see scheme in Figure 5A). Radioactive labelling of one of the 3′-protruding strands allows detection of nucleotide incorporation on this end, using the template information provided in trans by the other 3′-protrusion, that contains a 5′-P-group and will thus be used as a template/downstream structure (through binding of the phosphate by the 8 kDa domain of Polµ). In order to evaluate if the reaction is trans-directed, the templating base (X) on this second DNA substrate was changed to A, C, G or T (Figure 5). Our results showed that Poµ is able to perform an efficient and mostly template-directed trans-polymerization on this kind of NHEJ substrates, since the polymerase incorporated preferentially the nucleotide complementary to the templating base (white asterisks and box in Figure 5A). As expected, when the templating base is a G and thus the template strand contains a dinucleotide (GG), large sequence expansions were produced when providing the nucleotide (dCTP) complementary to the dinucleotide. The reiterative additions of dGTP that are also catalysed by Polµ in every case can be considered pure terminal transferase incorporations, since control experiments in which the template-providing end is not present, also showed this outcome (Supplementary Figure S4). This is in accordance with the preference for nucleotide incorporation displayed by Polµ during untemplated additions (41).

Figure 5.

Impact of the generation of sequence expansions during NHEJ repair reactions by Polµ. (A) The scheme corresponds to the end-joining substrates used, whose 3′-protrusions can be connected by three bases pairs but leaving a distortion (1 flipped-out base) close to the 3′-primer terminus. Such a connection leaves two different 1-nt gaps. Gap-filling of one of them (that flanked by a 5′-P) is evaluated as a function of each possible templating base (X). Thus, the 5′-labelled substrate (dark grey) will be tested as primer, whereas the cold substrate (light grey; in which the X in the scheme is changed to A, C, G or T) is providing the template for the connection. Polymerization reactions were performed in the presence of 200 nM Polµ, 2.5 mM MgCl2 and 100 µM of a single dNTP (complementary to X in each case). After incubation for 1 h at 30°C, reactions were stopped and loaded on 20% PA-8 M urea gels. Labelled DNA fragments were detected by autoradiography. (B) Polymerization reactions performed as in (A), but using end-joining substrates used whose 3′-protrusions can be connected by three bases pairs with no distortion.

Strikingly, in the context of NHEJ we were able to observe the formation of large sequence expansions even in the absence of a provided distortion upstream to the polymerization site (Figure 5B), thus limiting the requirements of this reaction only to the presence of a dinucleotide, a prerequisite that still needs to be met in this context. The amount of nucleotide that Polµ requires to produce these expansions is low (20 µM), indicating that this process is highly efficient (Supplementary Figure S5A and B). Again, dGTP is being inserted as a result of pure terminal transferase additions, as demonstrated by a control experiment, in which the template-providing end is not present (Supplementary Figure S4). We also detected expansion during NHEJ when the dinucleotide was formed by a pair of adenines (Supplementary Figure S5E and F), indicating that this mechanism is independent of the sequence context. Taken together, our results indicate that if the sequence context is favourable to the expansions (i.e., iteration of nucleotides at the template strand), the polymerase itself may generate the required upstream distortion by adjusting the bridging of the two ends, a scenario that emphasizes the importance of the mutagenic potential of Polµ during the NHEJ pathway, specifically regarding nucleotide expansions.

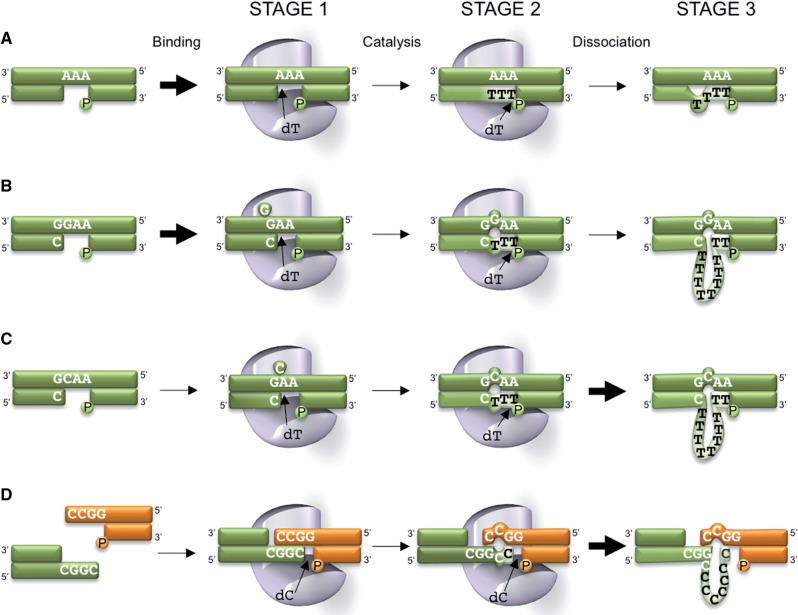

DISCUSSION

Indels (insertions and deletions) are common errors produced during DNA replication and repair, related to with different human pathologies including cancer and diseases associated with expansion of repeats. All polymerases studied to date generate indels during DNA synthesis in vitro (43), but with very different frequency. Thus, although X family members Polß, Polλ and Polµ all generate single-base deletions during synthesis (9,21,22), Polλ has a much higher deletion rate, whose structural basis has been proposed (44). The first hypothesis explanatory of the production of indels was introduced by Streisinger et al. (40): these frameshift mutations were described as products of strand slippage in repetitive DNA sequences. Other two models have been proposed since then, namely ‘direct misincorporation misalignment’, in which a polymerase introduces an initial mismatch that causes the primer terminus to be subsequently realigned (44,45) and ‘dNTP-stabilized misalignment’, in which incorporation of the correct dNTP occurs in front of a complementary downstream template base (46,47).

The results presented here demonstrate that human Polµ can catalyse large nucleotide expansions when copying a repeated templating base in the vicinity of a 5′-P. Based on our findings with different sequence contexts, we propose a specific model for Polµ-mediated generation of the expansions during gap-filling that requires: (i) initial dislocation of the template strand; (ii) generation of a mismatch/distortion, that will trigger nucleotide expansion (Figure 6B and C). Initial template dislocation can be either facilitated by slippage, when the primer-terminus is complementary to the first nucleotide at the gap (Figure 6B), or stabilized by the incoming nucleotide (dNTP-mediated; Figure 6C); in both cases, after initial dislocation (stage 1), the gap is filled and a mismatch is left behind (stage 2), and then expansion occurs (stage 3). However, such expansions are not simply the result of Streisinger's ‘strand slippage’: if the sequence to be copied is formed by the three same nucleotides (Figure 6A), the expansion hardly happens because the mismatch/distortion that could trigger further nucleotide incorporation beyond gap-filling is not allowed to occur.

Figure 6.

Mechanistic model for dinucleotide expansions generated by human Polµ. Thick arrows indicate more efficient reactions, whereas thin arrows are related to slower or less favourable reactions. (A) Trinucleotide conformed by the same nucleotide. In this case, no distortion associated to gap-filling is generated, thus precluding a large expansion. (B) After polymerase binding and realignment of the primer terminus, a ‘slippage-mediated’ dislocation is formed, creating a template distortion. In this situation, a large expansion reaction is observed. (C) In this case the distortion is induced by a ‘dNTP-selection-mediated’ dislocation of the template strand, again resulting in the generation of large sequence expansions. (D) In a NHEJ context, a repeated nucleotide neighbour to the 5′-P can induce nucleotide expansions by Polµ, although in this case, a pre-existing stable distortion or impairing is not strictly required.

Such gaps, eventually containing distortions, are common substrates at the second step of NHEJ, as they are generated after repairing the first strand of the DSB. Moreover, our results indicate that our model for the production of expansions of iterative dinucleotides is also valid during the first step of NHEJ (Figure 6F), where the critical requisite of generating a distortion upstream the primer terminus is expected to occur during end-bridging and search for microhomology.

Relationship between terminal transferase and the generation of sequence expansions

In most DNA-dependent DNA polymerases, proper positioning of the 3′ terminus is indirectly dictated by the enzyme’s avidity for the templating base, thus configuring a binary complex ready to select the incoming nucleotide (ternary complex). Eventually, when no template base is available (blunt or 3′-protruding ends, or when a gap has been fulfilled), any further nucleotide addition is unfavoured, due to deficient translocation of the 3′ terminus, thus precluding addition of extra nucleotides. Template instruction is a general feature of most members of the X family, with the exception of TdT. Interestingly, Polµ shows hybrid biochemical properties: it is strongly activated by a template DNA chain (4), but it has an intrinsic terminal transferase activity, although weaker than TdT. A specific histidine residue, conserved between Polµ (His329) and TdT (His342), but absent in Polß (Gly189) or Polλ (Gly426), confers terminal transferase activity as it is crucial and responsible for proper positioning of the primer terminus and the incoming nucleotide in the absence of a template (42). Mutating this histidine in Polµ (10,42), and TdT (48) substantially reduced template-independent activity. As shown here, elimination of His329 rendered Polµ unable to perform sequence expansions in the context of a gap. Therefore, the specific role of His329 during Polµ's catalytic cycle, facilitating primer translocation during both templated and non-templated nucleotide insertion (terminal transferase) has two sides, being beneficial for NHEJ of incompatible-ends but allowing, as a collateral effect, the eventual generation of large sequence expansions through the very same mechanism of favoured primer translocation. Besides, Polµ's terminal transferase activity is negatively regulated by Arg387 (10), acting as a brake for the necessary movement of the primer (thus counteracting His329), to limit excessive nucleotide additions before end-bridging. The role of this residue in a non-distorted gap would be positive in terms of genome stability, because a braked primer translocation would help to reduce the number of extra nucleotide units added beyond gap-filling (Figure 6A). However, in a physiological context of DSB repair, where NHEJ produces gaps with eventual distortions (shown here to be a requisite for expansion), Arg387 might not be able to maintain the contacts with the primer, allowing un-braked translocation and facilitating nucleotide expansion. In summary, our site-directed mutagenesis results support that the same mechanism that provides Polµ with the ability to perform untemplated insertion of nucleotides (terminal transferase), beneficial for NHEJ of non-complementary ends, has an unexpected downside, since it also allows Polµ to generate large sequence expansions in the context of repair reactions.

Polµ, a candidate to generate mono- and dinucleotide expansions in vivo

The genome of most organisms thus far examined contains many tracts of repetitive DNA called microsatellites. The discovery that a number of human diseases are the direct consequence of mutations within such repeats has triggered considerable interest in the mechanisms that change the number of copies of repeated DNA sequences. DNA expansions in mono- and dinucleotide repeats are more likely to be deleterious to the cell by causing not only addition mutations but also frameshift mutations. Current models of DNA repeat instability involve DNA polymerase slippage at these iterative tracts, which are normally associated with mutation hot-spots. Which polymerases are responsible for expansions? Initial efforts were oriented to measure DNA polymerase-catalysed ‘reiterative replication’ of repeat sequences with replicative polymerases (34,49–52), but evidence soon indicated that those lacking proofreading and also strand displacement capabilities are better candidates (53–55). Moreover, other results indicate that sequence expansions could be linked to DNA damage (32), a process causatively related with ageing (56,57). That could be a vicious cycle, as it is quite possible that repetitive DNA is a better target for DNA damage than normal DNA. Repair substrates as short gaps are produced in vivo during base excision repair, as well as during the final steps of nucleotide excision repair and post-replication MMR. More specifically, DNA polymerases as Polµ are able to configure gap-like substrates during NHEJ. In all these substrates, the presence of a downstream strand would lead to the ‘stalling’ of the polymerization reaction (54), thus providing sufficient time for realigning the primer strand and triggering expansive nucleotide insertion.

Our results suggest that Polµ can generate the expansion of mononucleotide tracts during these repair reactions in vivo, given the appropriate sequence context. It is not yet known whether homopolymeric runs are more prone to DSBs than non-iterative sequences, but the possibility can be easily envisaged, due to the ssDNA-containing secondary structures that these sequences can adopt. As derived from our work, in the case of a DSB occurring at a site containing an iterative sequence as short as a single dinucleotide, the outcome of a Polµ-mediated repair reaction would result in the generation of frameshifts and sequence expansions. This could in turn lead to an increased risk of microsatellite and genome instability, events that have been related to cancer and other illnesses such as neurodegenerative syndromes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Figures 1–5.

FUNDING

Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnologia [BFU2009-10085 and CONSOLIDER CSD2007-00015]; Fundacion Ramon Areces (to Centro de Biologia Molecular ‘‘Severo Ochoa’’); Ministerio de Educacion y Ciencia (to A.A.); Comunidad Autonoma de Madrid (to M.J.M.). Funding for open access charge: Comunidad de Madrid grant [S2011/BMD-2361].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoeijmakers JH. DNA repair mechanisms. Maturitas. 2001;38:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00188-2. discussion 22–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgers PM, Koonin EV, Bruford E, Blanco L, Burtis KC, Christman MF, Copeland WC, Friedberg EC, Hanaoka F, Hinkle DC, et al. Eukaryotic DNA polymerases: proposal for a revised nomenclature. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43487–43490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moon AF, Garcia-Diaz M, Batra VK, Beard WA, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA, Wilson SH, Pedersen LC. The X family portrait: structural insights into biological functions of X family polymerases. DNA Repair. 2007;6:1709–1725. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominguez O, Ruiz JF, Lain de Lera T, Garcia-Diaz M, Gonzalez MA, Kirchhoff T, Martinez AC, Bernad A, Blanco L. DNA polymerase mu (Pol mu), homologous to TdT, could act as a DNA mutator in eukaryotic cells. EMBO J. 2000;19:1731–1742. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruiz JF, Dominguez O, Lain de Lera T, Garcia-Diaz M, Bernad A, Blanco L. DNA polymerase mu, a candidate hypermutase? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2001;356:99–109. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nick McElhinny SA, Ramsden DA. Polymerase mu is a DNA-directed DNA/RNA polymerase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:2309–2315. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2309-2315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruiz JF, Juarez R, Garcia-Diaz M, Terrados G, Picher AJ, Gonzalez-Barrera S, Fernandez de Henestrosa AR, Blanco L. Lack of sugar discrimination by human Pol mu requires a single glycine residue. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4441–4449. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz JF, Lucas D, Garcia-Palomero E, Saez AI, Gonzalez MA, Piris MA, Bernad A, Blanco L. Overexpression of human DNA polymerase mu (Pol mu) in a Burkitt's lymphoma cell line affects the somatic hypermutation rate. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5861–5873. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Wu X, Yuan F, Xie Z, Wang Z. Highly frequent frameshift DNA synthesis by human DNA polymerase mu. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:7995–8006. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.23.7995-8006.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrade P, Martin MJ, Juarez R, Lopez de Saro F, Blanco L. Limited terminal transferase in human DNA polymerase mu defines the required balance between accuracy and efficiency in NHEJ. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:16203–16208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908492106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis BJ, Havener JM, Ramsden DA. End-bridging is required for pol mu to efficiently promote repair of noncomplementary ends by nonhomologous end joining. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3085–3094. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duvauchelle JB, Blanco L, Fuchs RP, Cordonnier AM. Human DNA polymerase mu (Pol mu) exhibits an unusual replication slippage ability at AAF lesion. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2061–2067. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capp JP, Boudsocq F, Besnard AG, Lopez BS, Cazaux C, Hoffmann JS, Canitrot Y. Involvement of DNA polymerase mu in the repair of a specific subset of DNA double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3551–3560. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahajan KN, Nick McElhinny SA, Mitchell BS, Ramsden DA. Association of DNA polymerase mu (pol mu) with Ku and ligase IV: role for pol mu in end-joining double-strand break repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:5194–5202. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.14.5194-5202.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nick McElhinny SA, Havener JM, Garcia-Diaz M, Juarez R, Bebenek K, Kee BL, Blanco L, Kunkel TA, Ramsden DA. A gradient of template dependence defines distinct biological roles for family X polymerases in nonhomologous end joining. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertocci B, De Smet A, Weill JC, Reynaud CA. Nonoverlapping functions of DNA polymerases mu, lambda, and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase during immunoglobulin V(D)J recombination in vivo. Immunity. 2006;25:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chayot R, Danckaert A, Montagne B, Ricchetti M. Lack of DNA polymerase mu affects the kinetics of DNA double-strand break repair and impacts on cellular senescence. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:1187–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chayot R, Montagne B, Ricchetti M. DNA polymerase mu is a global player in the repair of non-homologous end-joining substrates. DNA Repair (Amst) 2012;11:22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gozalbo-Lopez B, Andrade P, Terrados G, de Andres B, Serrano N, Cortegano I, Palacios B, Bernad A, Blanco L, Marcos MA, et al. A role for DNA polymerase mu in the emerging DJH rearrangements of the postgastrulation mouse embryo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:1266–1275. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01518-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucas D, Escudero B, Ligos JM, Segovia JC, Estrada JC, Terrados G, Blanco L, Samper E, Bernad A. Altered hematopoiesis in mice lacking DNA polymerase mu is due to inefficient double-strand break repair. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bebenek K, Garcia-Diaz M, Blanco L, Kunkel TA. The frameshift infidelity of human DNA polymerase lambda. Implications for function. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:34685–34690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunkel TA. The mutational specificity of DNA polymerase-beta during in vitro DNA synthesis. Production of frameshift, base substitution, and deletion mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:5787–5796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Covo S, Blanco L, Livneh Z. Lesion bypass by human DNA polymerase mu reveals a template-dependent, sequence-independent nucleotidyl transferase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:859–865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowater RP, Wells RD. The intrinsically unstable life of DNA triplet repeats associated with human hereditary disorders. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2001;66:159–202. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)66029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wells RD, Dere R, Hebert ML, Napierala M, Son LS. Advances in mechanisms of genetic instability related to hereditary neurological diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3785–3798. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirkin SM. Toward a unified theory for repeat expansions. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:635–637. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0805-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mirkin SM. Expandable DNA repeats and human disease. Nature. 2007;447:932–940. doi: 10.1038/nature05977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pearson CE, Nichol Edamura K, Cleary JD. Repeat instability: mechanisms of dynamic mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:729–742. doi: 10.1038/nrg1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manley K, Shirley TL, Flaherty L, Messer A. Msh2 deficiency prevents in vivo somatic instability of the CAG repeat in Huntington disease transgenic mice. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:471–473. doi: 10.1038/70598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Broek WJ, Nelen MR, Wansink DG, Coerwinkel MM, te Riele H, Groenen PJ, Wieringa B. Somatic expansion behaviour of the (CTG)n repeat in myotonic dystrophy knock-in mice is differentially affected by Msh3 and Msh6 mismatch-repair proteins. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:191–198. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bogdanov MB, Andreassen OA, Dedeoglu A, Ferrante RJ, Beal MF. Increased oxidative damage to DNA in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease. J. Neurochem. 2001;79:1246–1249. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovtun IV, Liu Y, Bjoras M, Klungland A, Wilson SH, McMurray CT. OGG1 initiates age-dependent CAG trinucleotide expansion in somatic cells. Nature. 2007;447:447–452. doi: 10.1038/nature05778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Prasad R, Beard WA, Hou EW, Horton JK, McMurray CT, Wilson SH. Coordination between polymerase beta and FEN1 can modulate CAG repeat expansion. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:28352–28366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.050286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sinden RR, Potaman VN, Oussatcheva EA, Pearson CE, Lyubchenko YL, Shlyakhtenko LS. Triplet repeat DNA structures and human genetic disease: dynamic mutations from dynamic DNA. J. Biosci. 2002;27:53–65. doi: 10.1007/BF02703683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K, Sabariegos R, Dominguez O, Rodriguez J, Kirchhoff T, Garcia-Palomero E, Picher AJ, Juarez R, Ruiz JF, et al. DNA polymerase lambda, a novel DNA repair enzyme in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:13184–13191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Picher AJ, Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K, Pedersen LC, Kunkel TA, Blanco L. Promiscuous mismatch extension by human DNA polymerase lambda. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3259–3266. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sawaya MR, Prasad R, Wilson SH, Kraut J, Pelletier H. Crystal structures of human DNA polymerase beta complexed with gapped and nicked DNA: evidence for an induced fit mechanism. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11205–11215. doi: 10.1021/bi9703812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin MJ, Juarez R, Blanco L. DNA-binding determinants promoting NHEJ by human Polµ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:11389–11403. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singhal RK, Wilson SH. Short gap-filling synthesis by DNA polymerase beta is processive. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:15906–15911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Streisinger G, Okada Y, Emrich J, Newton J, Tsugita A, Terzaghi E, Inouye M. Frameshift mutations and the genetic code. This paper is dedicated to Professor Theodosius Dobzhansky on the occasion of his 66th birthday. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1966;31:77–84. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1966.031.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Juarez R, Ruiz JF, Nick McElhinny SA, Ramsden D, Blanco L. A specific loop in human DNA polymerase mu allows switching between creative and DNA-instructed synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4572–4582. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moon AF, Garcia-Diaz M, Bebenek K, Davis BJ, Zhong X, Ramsden DA, Kunkel TA, Pedersen LC. Structural insight into the substrate specificity of DNA Polymerase mu. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:45–53. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kunkel TA. DNA replication fidelity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:16895–16898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bebenek K, Kunkel TA. Frameshift errors initiated by nucleotide misincorporation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:4946–4950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.4946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kunkel TA, Soni A. Mutagenesis by transient misalignment. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:14784–14789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bloom LB, Chen X, Fygenson DK, Turner J, O'Donnell M, Goodman MF. Fidelity of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase III holoenzyme. The effects of beta, gamma complex processivity proteins and epsilon proofreading exonuclease on nucleotide misincorporation efficiencies. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:27919–27930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Efrati E, Tocco G, Eritja R, Wilson SH, Goodman MF. Abasic translesion synthesis by DNA polymerase beta violates the “A-rule”. Novel types of nucleotide incorporation by human DNA polymerase beta at an abasic lesion in different sequence contexts. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:2559–2569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romain F, Barbosa I, Gouge J, Rougeon F, Delarue M. Conferring a template-dependent polymerase activity to terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase by mutations in the Loop1 region. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4642–4656. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lyons-Darden T, Topal MD. Effects of temperature, Mg2+ concentration and mismatches on triplet-repeat expansion during DNA replication in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2235–2240. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.11.2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petruska J, Hartenstine MJ, Goodman MF. Analysis of strand slippage in DNA polymerase expansions of CAG/CTG triplet repeats associated with neurodegenerative disease. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:5204–5210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Canceill D, Viguera E, Ehrlich SD. Replication slippage of different DNA polymerases is inversely related to their strand displacement efficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:27481–27490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sinden RR, Wells RD. DNA structure, mutations, and human genetic disease. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 1992;3:612–622. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(92)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.da Silva EF, Reha-Krantz LJ. Dinucleotide repeat expansion catalyzed by bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:31528–31535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hartenstine MJ, Goodman MF, Petruska J. Weak strand displacement activity enables human DNA polymerase beta to expand CAG/CTG triplet repeats at strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:41379–41389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kunkel TA, Patel SS, Johnson KA. Error-prone replication of repeated DNA sequences by T7 DNA polymerase in the absence of its processivity subunit. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:6830–6834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stadtman ER. Protein oxidation and aging. Science. 1992;257:1220–1224. doi: 10.1126/science.1355616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cardozo-Pelaez F, Song S, Parthasarathy A, Hazzi C, Naidu K, Sanchez-Ramos J. Oxidative DNA damage in the aging mouse brain. Mov. Disord. 1999;14:972–980. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199911)14:6<972::aid-mds1010>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.